Abstract

Purpose

Maltodextrin (MDX) is a polysaccharide food additive commonly used as oral placebo/control to investigate treatments/interventions in humans. The aims of this study were to appraise the MDX effects on human physiology/gut microbiota, and to assess the validity of MDX as a placebo-control.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of randomized-placebo-controlled clinical trials (RCTs) where MDX was used as an orally consumed placebo. Data were extracted from study results where effects (physiological/microbial) were attributed (or not) to MDX, and from study participant outcomes data, before-and-after MDX consumption, for post-publication ‘re-analysis’ using paired-data statistics.

Results

Of two hundred-sixteen studies on ‘MDX/microbiome’, seventy RCTs (n = 70) were selected for analysis. Supporting concerns regarding the validity of MDX as a placebo, the majority of RCTs (60%, CI 95% = 0.48–0.76; n = 42/70; Fisher-exact p = 0.001, expected < 5/70) reported MDX-induced physiological (38.1%, n = 16/42; p = 0.005), microbial metabolite (19%, n = 8/42; p = 0.013), or microbiome (50%, n = 21/42; p = 0.0001) effects. MDX-induced alterations on gut microbiome included changes in the Firmicutes and/or Bacteroidetes phyla, and Lactobacillus and/or Bifidobacterium species. Effects on various immunological, inflammatory markers, and gut function/permeability were also documented in 25.6% of the studies (n = 10/42). Notably, there was considerable variability in the direction of effects (decrease/increase), MDX dose, form (powder/pill), duration, and disease/populations studied. Overall, only 20% (n = 14/70; p = 0.026) of studies cross-referenced MDX as a justifiable/innocuous placebo, while 2.9% of studies (n = 2/70) acknowledged their data the opposite.

Conclusion

Orally-consumed MDX often (63.9% of RCTs) induces effects on human physiology/gut microbiota. Such effects question the validity of MDX as a placebo-control in human clinical trials.

Keywords: Gut microbiome, Firmicutes:Bacteroidetes ratio, Food additive, Experimental design

Introduction

Food additive maltodextrin (MDX) is manufactured using hydrolysis, purification, and spray-drying methods applied on a variety of starches to produce chains that typically range from 3 to 20 D-glucose polymers which are linked primarily by alpha(1–4) or alpha(1–6) glyosidic bonds. MDX has a dextrose equivalent of less than 20 [1]. There are two types of MDX; digestible, and resistant-to-digestion MDX (RMD). Resistant-to-digestion MDX are a non-viscous soluble fiber that is created via an additional conversion of the alpha-1,4-glucose linkages to random 1,2-,1,3-, and 1,4-alpha or -beta linkages, which resist the digestion process [2]. Being resistant to digestion, RMD is considered a prebiotic and fermented by the intestinal bacterial flora and previous studies have reported its effect on gastrointestinal homeostasis [3–5]. Since its production in the 1950’s, digestible MDX is generally regarded as safe (GRAS) by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is widely used as a retail food additive by the food industry [6].

The use of placebos in human clinical research is necessary for rigor and reproducibility. However, depending on the situation, the selection of an appropriate placebo is challenging and critical to determine the effect of the tested intervention where the placebo is used as a referent comparator. A placebo is expected to be, by definition, an inert or harmless substance that appears identical to the treatment being tested in a clinical trial, but that contains no active ingredients present in the treatments compared [7–9].

Maltodextrin is present in a wide range of processed food and products including the non-calorie sweetener Splenda™, sport drinks, baked goods and various fiber/dietary supplements. It is supplied as a white, tasteless, water-soluble powder, which makes it appreciated by food industries as a filler, and texturizer [1, 8].

From a microbiological stand point, MDX is, however, a preferred class of nutrients for Escherichia coli in environmental and animal hosts. Bacteria such as E.coli metabolize MDX through the maltose system, which offers an unusually rich set of enzymes, transporters, and regulators [10].

As a low-sweet food additive polysaccharide, MDX has been used to study the effect of a wide variety of interventions, especially prebiotics [11, 12], probiotics [13, 14], and numerous dietary supplements [15, 16]. Despite the adoption of such practice, we hypothesized that MDX is, however, an inappropriate placebo since in vitro [17] and animal studies have shown that MDX promotes intestinal injury [18], inflammation [19], and gut microbiota changes [20].

To assess the validity of MDX as placebo and control comparator group in humans, herein we performed a systematic review of randomized-placebo-controlled clinical trials (RCTs) to appraise MDX effects on human physiology and gut microbiota. The main objective of this report is to describe and quantify the association between MDX and microbiological outcomes assessed in human clinical trials where MDX was used as placebo or control group, with special emphasis on microbiome studies.

Materials and methods

Reporting and protocol registration

The systematic review protocols used in this study were reported in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [21] and the Systematic Literature Review registration website PROSPERO (CRD42021249173) https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=249173.

Search strategy, eligibility and selection criteria

We conducted a systematic search of available and relevant RCTs using digestible MDX as a control or placebo to interpret the effect of other dietary products on microbiome and gut biology. The search strategy and terms used in electronic database PubMed was the following: ‘(maltodextrin) AND (microbiome)’ or ‘(maltodextrin) AND (Bacteroide*)’. No restrictions were imposed regarding study publication date, time period, or study origin. We used the PubMed definition of a RCT as indicated by the option to select a box labelled ‘Randomized Clinical Trial’ which is present on the left-hand side of a PubMed search page under the heading ‘ARTICLE TYPE’. RA and ARB selected articles independently for eligibility. Titles and abstracts were independently screened/filtered using a Data Extraction Tool (Supplementary Table 1). The search was updated on 21 May 2021, prior to manuscript submission, and on November 23 prior to manuscript acceptance using also Scopus database for verification of database coverage and assessment of publication bias. Herein, we verified 100% database coverage agreement between Scopus and PubMed. Of note, in 2007, Falagas et al. [22] determined that for citation analysis, Scopus (suboptimal for citations before 1996, and not readily updated for early online publications) offered about 20% more coverage than other wide-scope databases such as Web of Science across all field of science. Despite these features for Scopus, PubMed which focuses on medicine and biomedical sciences, remains the gold standard publications resource for clinicians and researchers. Irrelevant records were excluded (e.g., duplicated records, study protocols, reviews). Relevant full-text articles were exported using EndNote X9 reference management software and eligibility assessed using our full-article Data Extraction Tool (Supplementary Table 2). Articles were then retained or discarded when full agreement was reached. No disagreements occurred during the selection phase. All citations discovered through the manual searching method, which were not identified through electronic search, were assessed in the same manner as electronic citations. For instance, citations that were cited in our potential selected articles and believed to be relevant were retrieved. Studies without subjects’ baseline (i.e., before MDX) data were excluded.

Data extraction and risk-of-bias assessment

Data were extracted by RA and ARB independent of each other and selection accuracy was reviewed by ARP. Data from ‘before’ and ‘after’ MDX consumption was extracted. To enable the comparison of data across studies, herein we used Bacteroidetes (B) and Firmicutes (F) data (and their F:B ratio) as the primary study outcome for comparison, since most microbiome methods provide such basic information at the phylum level [23], and since changes in the B:F ratio has been used as a marker to express the degree of dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) [24] and can be altered in response to diets [25]. Other significant clinical parameters were also extracted for secondary analysis such as alteration in immunological markers, inflammatory mediators, and microbiota metabolites (i.e., short chain fatty acids; SCFAs) (Supplementary material 1—excel file).

Specifically, data were extracted from potential eligible citations using the following parameters; (1) general study information (author’s name, publication year, PMID, trial design, objective/s, subjects), (2) intervention details and comparison groups (MDX as placebo/control, MDX dosage, number of comparison groups, whether or not a non-chemical control was used, and duration of the intervention), and (3) outcomes; MDX effect on gut microbiota focusing on markers and bacteria well-known to contribute to gastrointestinal health or dysbiosis (i.e., F:B ratio, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria at phylum level, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and Streptococcus at genus level and Escherichia coli species). Published data represented as boxplots were excluded since individual data points or mean ± SD cannot be extracted for analysis. MDX-infant studies, when MDX was not given directly to the infants, were excluded, because the MDX effect, where diet/behavior progressively change infant microbiota, could not be determined. Publication bias was assessed by the Funnel plot and Egger’s test, correcting for funnel plot asymmetry as we reported [26].

Meta-analysis and scope

We intended to conduct a meta-analysis on the effect of MDX on the F:B ratio. However, with the study variability in RCT design, the number of comparable studies as described in Table 1 was insufficient to conduct formal collective or subgroup meta-analyses. Because of this, herein we report the study findings of the systematic review following a scoping format for the MDX treatment regime as placebo and for the effects of MDX on different human physiological parameters, including body weight, glucose, gut microbiome, transit time, microbial metabolites, and immunological markers, as available, in each RCT report.

Table 1.

Human randomized clinical trials that used maltodextrin (MDX) as oral ‘placebo’

| Study | Study design | Subjects | Dosage of MDX | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Berding 2021 [64] | MDX vs. Litesse® Ultra (>90% PDX polymer) (RCTdb crosso) | 18 healthy female | 12.5 g/d | 4 wk |

| Rosli 2021 [33] | MDX vs. partially hydrolyzed guar gum (PHGG) (RCTdb) | 12 adult pelvic cancer patients | 20 g/d | 14 d prior & 14 d during radiation |

| Mall 2020 [63] | MDX vs. Oat-glucan vs. Arabinoxylan (RCT) | 49 healthy elderly (challenged with indomethacin) | 12 g/d | 6 wk |

| Padilha 2020 [79] | MDX vs. FOS + MDX (equal amount of MDX in both groups) (RCT-sb) | 25 lactating women | 2 g/d | 20 d |

| An 2019 [80] | MDX vs Sugar Beet Pectin (RCTdb) | 27 healthy young adults & 24 elderly | 15 g/d | 4 wk |

| Haghighat 2019 [81] | MDX vs. synbiotic vs. probiotic (5 g probiotics with 15 g of MDX) (RCTdb) | 19 hemodialysis patients | 20 g/d | 12 wk |

| Istas 2019 [42] | MDX vs. Aronia whole fruit vs. Aronia extract (RCTdb) | 20 healthy young men | 1 capsule (500 mg)/d | 12 wk |

| Jalanka 2019 [42] | Study1: MDX vs. Metamucil (including psyllium) vs. 50:50 MDX + Metamucil mix (RCTdb crosso) Study2: MDX vs. psyllium RCTdb crosso) | 7 healthy adults 16 constipated patients |

42 g/d 21 g/d |

6 d |

| Khalili 2019 [82] | MDX vs. capsule of 108 cfu of L. casei (RCTdb) | 20 T2DM patients | NR 1 capsule/d |

8 wk |

| Lu 2019 [46] | MDX vs. mixed spices (RCTdb) | 15 healthy adults | 5 g/d capsules | 2 wk |

| Pedret 2019 [14] | MDX vs. B.animalis lactis CECT 8145 + 200 mg MDX vs. heat killed Ba8145 + 200mg MDX (RCTdb) | 40 obese individuals | 300 mg | 3 mos |

| Polakowski 2019 [83] | MDX vs. synbiotic (RCTdb) | 73 patients with colorectal cancer | NR | 1 wk during and after amoxicillin treatment |

| Ramos 2019 [84] | MDX vs. FOS (RCTdb) | 23 or 26 nondiabetic chronic kidney disease patients | Initial 3 g/d, raised by 3 g every 3d to final 12 g/d | 3 mo |

| Soldi 2019 [85] | MDX vs inulin-type fructans (RCTdb) | 105 healthy children (3–6 years old) | 6 g/d | 24 wk |

| Tandon 2019 [54] | MDX vs. FOS (RCTdb) | 17 healthy volunteers | 10g/d | 3 mos |

| Theou 2019 [30] | MDX vs. inulin + FOS mix (RCTdb) | 22 elderly people (> 65 years old) | 7.5 g/d | 13 wk |

| Beek 2018 [29] | High-fat milkshake containing MDX vs. inulin (RCTdb crosso) | 14 healthy, overweight to obese men | 24 g | 1 d |

| Burns 2018 [86] | MDX vs. RMD vs. MDX + RMD (RCTdb crosso) | 49 healthy adults | 25 g/d | 3 wk |

| Drabińska 2018 [41] | MDX vs. oligofructose-enriched inulin (RCT) | 16 pediatric Celiac disease patients on gluten-free diet | 7g/d | 12 wk |

| Lages 2018 [87] | MDX vs. symbiotic (RCTdb) | 18 head and neck cancer surgical patients | 12 g/d | From first postop. day and until > 5d and>7d |

| Lohner 2018 [45] | MDX vs. Fructans (RCTdb) | 109 (3–6 years old) healthy children | 6 g/d | 24 wk |

| Moreno-Pérez 2018 [15] | MDX vs. whey isolate + beef hydrolysate (RCTdb) | 18 regularly endurance training male | NR | 10 wk |

| Sloan 2018 [34] | MDX vs. oligofructose (RCTdb) | 37 Healthy adults | 14 g/d MDX plus low FODMAP | 1 wk |

| Azpiroz 2017 [35] | MDX vs. inulin (RCTdb) | 18 subjects with impaired handling of gut gas loads | 8 g/d | 4 wk |

| Beaumont 2017 [59] | MDX vs. casein vs. soy protein (RCTdb) | 13 overweight individuals | 15% of an individuals’ energy intake | 3 wk |

| Canfora 2017 [88] | MDX vs. GOS (RCTdb) | 23 overweight or obese pre-diabetic adults | 16.95 g/d | 12 wk |

| Corsello 2017 [13] | MDX vs. cow’s skim milk fermented with L. paracasei CBA L74 (RCTdb) | 60 healthy children | ≤2.9 g/d | 3 mos |

| Hustoft 2017 [89] | lowFODMAP diet (9 wk), after 3 wk, followed by MDX vs. FOS (RCTdb crosso) | 20 diarrhea-predominant or mixed IBS patients | 16 g/d | 10 d |

| Nicolucci 2017 [27] | MDX vs. oligofructose-enriched inulin (RCTdb) | 20 (7–12 years old) overweight children | 3.3 g/d | 16 wk |

| Shulman 2017 [36] | MDX vs. psyllium (RCTdb) | 47 children with IBS | NR | 6 wk |

| Buigues 2016 [90] | MDX vs. inulin + FOS mix (RCTdb) | 22 old participants aged 65 and over | 7.5 g/d | 13 wk |

| Clarke 2016 [65] | MDX vs. β2–1 fructan (RCTdb) | 30 healthy adults | 15 g/d | 4 wk |

| Fernandes 2016 [28] | MDX vs. FOS vs. FOS + L. paracasei LPC-37, L. rhamnosus HN001, L. acidophilus NCFM, and B. lactis HN019 (RC, triple blinded) | 3 Healthy and 3 undergoing Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass individuals | 6 g/d | 15 d |

| Pedersen 2016 [32] | MDX vs. GOS mix (RCTdb) | 13–15 men with well-controlled type 2 diabetes | 5.5 g/d | 12 wk |

| Ruiz 2016 [37] | MDX vs. RMD (RCTdb) | 33 healthy adults | 15 g/d | 3 wk |

| Scarpellini 2016 [91] | MDX vs. AXOS (RCT-sb crosso) | 13 healthy men | 40 g | 48 h |

| Eid 2015 [16] | MDX vs. Dates (RCT-crosso) | 22 healthy individuals | 3.9 g/d MDX + 33.19 dextrose | 3 wk |

| Maldonado-Lobón 2015 [38] | MDX vs. 3 L. fermentum CECT 5716 dosages (RCTdb) | 27 women suffering breast pain with lactation | NR 3 pills/d |

3 wk |

| Salazar 2015 [62] | MDX vs. Inulin-type fructans (RCTdb) | 15 obese women | 16 g/d | 3 mos |

| Sant’Anna 2015 [55] | MDX vs. GOS | 24 constipated adults (from ages 20 to 75 years) | 25 g/d | 30 d |

| Vulevic 2015 [92] | MDX vs. B-GOS mix (RCTdb crosso) | 40 elderly volunteers (65–80 years) | 5.5 g/d | 10 wk |

| Windey 2015 [93] | MDX vs. Wheat bran extract (RCTdb crosso) | 20 healthy adults | 10g/d | 3 wk |

| Bazzocchi 2014 [40] | MDX vs symbiotic (Psyllogel Mega-fermenti®) (RCTdb) | 12 tertiary care constipated patients | 5.6 g/d | 8 wk |

| Childs 2014 [94] | MDX vs. XOS + MDX vs. Bi-07+ MDX vs. XOS + Bi-07 (RCTdb crosso) | 38–41 healthy adults | NR | 3 wk |

| Majid 2014 [61] | Enteral nutrition with a formula containing 4.5 g/L of prebiotics + MDX vs. oligofructose/inulin (RCTdb) | 10 ICU adult patients | 7 g/d | At least 7d |

| Ladirat 2014 [60] | MDX vs. GOS (RCTdb) | 6 healthy adults | 7.5 g/d (1125 mg amoxicillin for 5d at study start) | 12 d |

| Vaghef-Mehrabany 2014 [67] | MDX vs. capsule of L. casei 01 (RCTdb) | 24 rheumatoid arthritis patients | NR capsule | 8 wk |

| Dewulf 2013 [12] | MDX vs inulin/oligofructose 50/50 mix (RCTdb) | 15 obese women | 16 g/d | 3 mos |

| Neto 2013 [31] | MDX vs symbiotic (Frutooligos, L. bacillus paracasei, L. rhamnosus, L. acidophilus and B.lactis) (RCTdb) | 7–8 elderly individuals | NR | 3 mos |

| Vulevic 2013 [95] | MDX vs. B-GOS (RCTdb crosso) | 45 overweight adults ≥ 3 factors for metabolic syndrome | 5.5 g/d | 12 wk |

| Waitzberg 2013 [96] | MDX vs. FOS + L. paracasei, L. rhamnosus, L. acidophilus and B.lactis (LACTO- FOS®) (RCTdb) |

100 constipated adult women | 12 g/d | 1 mos |

| Westerbeek 2013 [97] | MDX vs prebiotic mixture of neutral and acidic oligosaccharides (scGOS/lcFOS/pAOS) (RCTdb) | 58 preterm infants (<48 h after birth) | Increasing doses to max. of 1.5 g/kg/d | Between days 3 and 30 of life |

| Lecerf 2012 [98] | Wheat MDX (12 DE) vs. XOS vs. inulin + XOS mix (RCTdb) | 20 healthy adults | 6.64 g/d | 4 wk |

| Iemoli 2012 [66] | MDX vs. L. salivarius + B.breve in MDX (RCTdb) | 15 Atopic dermatitis adult patients | NR | 12 wk |

| Salvini 2011 [11] | MDX vs. short-chain galacto-oligo- saccharide: long-chain fructo-oligo- saccharides, ratio 9:1) (RCTdb) | 10 newborns of hepatitis C virus-infected mothers | 8 g/L | 6 wk |

| Waitzberg 2012 [43] | MDX vs. inulin and partially hydrolyzed guar gum mixture (RCTdb) | 32 constipated adult females | 15 g/d | 3 wk |

| Costabile 2010 [44] | MDX vs. very long- chain inulin (RCTdb crosso) | 31 healthy volunteers | lOg/d | 3 wk |

| Fastinger 2008 [5] | MDX vs MDX + RMD vs RMD (RCTdb) | 12 healthy adults | 15 g/d | 3 wk |

| Kolida 2007 [39] | MDX vs. inulin vs. inulin + MDX (RCTdb crosso) | 30 healthy adults | 8g/d | 2 wk |

| Shadid 2007 [68] | MDX vs. GOS + lcFOS (Withl9.34% maltodextrin) (RCTdb) | 16 pregnant women | 6 g/d | 15 wk (from 25 wk of gestation until delivery) |

| Schouten 2006 [99] | MDX vs GOS/FOS (RCTdb) | 7 (4–6mos) old infants | 1.5 g/serving (target intake: 4.5 g/d) | 6 wk |

| Sathitkowitchai 2021 [75]* | MDX vs copra meal hydrolysate + MDX (RCTdb) | 20 healthy adults | 10g/d | 3 wk |

| Chen 2021 [100] * | MDX vs. arabinogalactan (RCTdb crosso) | 27–28 healthy adults | 15 g/d | 6 wk |

| Lee 202021 [101]* | MDX vs. Kefir (SYNKEFIR™) (CTdb crosso) | 16 healthy and untrained males | 20 g/d | 28 days |

| Leyrolle 2021 [102]* | MDX vs native inulin (RCT-sb) | 55 obese patients | 16 g/d | 3mos |

| Calgaro 2021 [77]* | MDX vs probiotic mixture of Limosi-lactobacillus fermentum LF16, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus LR06, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LP01 and B. longum 04 in MDX 4.109 cfu/AFU in 2.5 g of MDX | 15 healthy adults | 2.5 g/d | 6 wk |

| Benítez-Páez 2021 [103]* | MDX vs inulin + RMD (RCT-sb) | 40 Overweight participants (all participants followed caloric restriction diet) | NR | 12 wk |

| Neyrinck 2021 [104]* | MDX vs chitin-glucan (CT-sb) | 15 fasting healthy adults | 4.5 g/d | once with breakfast |

| Tang 2021 [105]* | MDX vs probiotic (Enterococcus faecium and Bacillus subtilis) (MRT) | 74 patients receiving bismuth quadruple therapy for 14d | NR | 4 wk |

| Ma 2021 [76]* | MDX vs L. plantarum P-8 + MDX (RCTdb) | 36 stressed adults | NR | 12 wk |

D dosage, FOS fructooligosaccharides, GOS galactooligosaccharides, MDX maltodextrin, N sample size, RCT randomized clinical trial, RCT-sb single-blinded randomized clinical trial, RCTdb double-blinded randomized clinical trial, RCTdb crosso double-blinded crossover randomized clinical trial, T2DM type 2 diabetes, MRT Multicenter randomized trial, RMD digestion-resistant maltodextrins

Identified via Scopus search

Statistical analysis

Before-and-after MDX data was compared using paired-T test with an appropriate method that controls for data dispersion or variability including mean, standard deviation, and standard error of the mean, using GraphPad Prism 9.1 software. Data integration for each parameter was used for comparable studies. Data not integrated were reported descriptively. To statistically determine whether the number of positive studies was significantly different from the expectation of no effect due to MDX (0 ± 5 studies out of 70 RCTs), we used count Fisher exact statistics. Significance, p < 0.05.

Results

Literature search

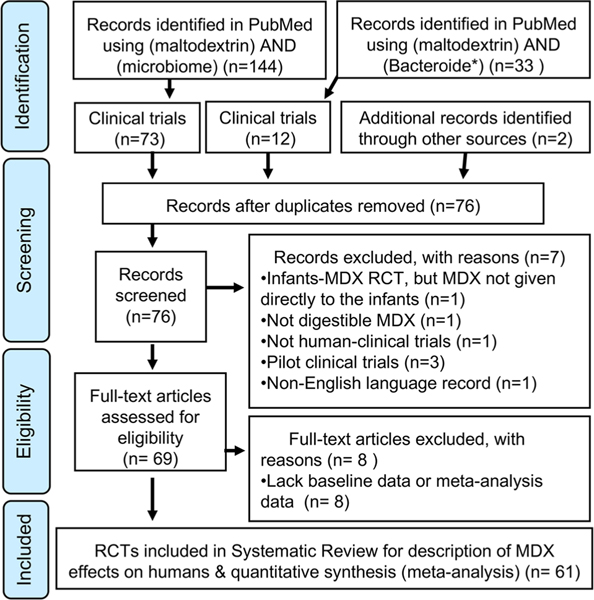

In accordance with PRISMA guidelines [21], Fig. 1 describes the selection process for included studies. The initial PubMed and Scopus search identified two hundred-sixteen articles. This number was reduced to seventy-seven (n = 77) after duplicates were removed. After screening titles and abstracts for eligibility, a total of seventy RCTs (n = 70) were included from the originally identified articles.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for study selection (PRISMA). A total of nine RCTs (n = 9) from Scopus search published on 2021were included in the analysis

Study characteristics

Of the seventy studies, 87% (n = 61/70) were double blindplacebo-control RCTs, of which 22.9% (n = 16/70) were crossover trials. The remaining 12.9% (n = 9/70) of RCTs were either single or non-blinded trials. Table 1 lists the study design features for the final selected seventy RCTs. With respect to the sample size, both experimental and control groups ranged from 6 to 105 individuals in total per study. Overall, MDX was used as a placebo to study between 1 and 3 other treatments/interventions (MDX vs. 1 group, n = 54/70; vs. 2 groups, n = 13/70; vs. 3 groups, n = 3/70), mainly prebiotics and probiotics. Collectively, these primarily microbiome-focused RCTs encompassed various clinical fields and diseases, including type-2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, constipation, bone fragility, kidney diseases, cancer, and intensive care conditions across a wide range of participants that included pregnant women, lactating mother-and-infant pairs, children, and adults. Considerable variability was observed across studies regarding MDX dosage regime (0.3–42 g/d) and treatment duration (1–168 days).

Use of MDX as a placebo in humans

To interrogate whether the limitations or advantages of MDX as a placebo were common knowledge in the scientific community, we determined which studies cited peer-reviewed literature providing a rationale/justification for MDX use as placebo/control. Overall, 20% (CI 95% = 0.11–0.31; n = 14/70; p < 0.00001) of studies cross-referenced MDX as a justifiable/innocuous placebo, while 2.9% of studies (n = 2/70) acknowledged with their data the opposite (see verbatim justifications in Table 2). Since the majority of the studies (80%) provided no justification/rationale, we examined the reported effects of MDX across all selected RCTs on human physiology and gut microbiota. Table 3 lists the studies that showed a significant effect, either reported or computed (e.g., paired T test, before-and-after data) from MDX.

Table 2.

Verbatim reported justification or rationale for using MDX in human clinical trials

| Rationale or justification | |

|---|---|

| Study | Verbatim reported justification or rationale for using MDX in human clinical trials |

|

| |

| Polakowski 2019 [83] | “Maltodextrin is a carbohydrate module that is not associated to either benefit or harm to the patient” |

| Tandon 2019 [54] | “Following the precedent of earlier studies an additional placebo arm was included for comparison” |

| Drabińska 2018 [41] | “Maltodextrin was selected as a placebo, as it is digested in the small intestine, contrary to prebiotics that reach the colon in intact form” |

| Moreno-Pérez 2018 [15] | “Maltodextrin absorbed in the upper part of the intestine and does not reach the colon” |

| Nicolucci 2017 [27] | “Maltodextrin has a similar taste and appearance to Synergy 1 and has been used previously in prebiotic trials” |

| Shulman 2017 [36] | “It has been suggested, although no data were provided, that maltodextrin may affect the response to placebo in IBS. However, this is unlikely because we have shown previously that maltodextrin is well digested even in preterm and young infants” |

| Pedersen 2016 [32] | “Maltodextrin with its total digestion in the small intestine” |

| Scarpellini 2016 [91] | “Maltodextrin is a non-fermented substrate in the colon” |

| Sant’Anna 2015 [55] | “Maltodextrin is an easily digested and absorbed carbohydrate and is not fermented by the bacteria in the colon, thus not interfering with the microbial ecology of the gastrointestinal tract” |

| Windey 2015 [93] | “Maltodextrin is completely digestible in the human small intestine” |

| Childs 2014 [94] | “MDX is fully absorbed as glucose within the small intestine and therefore will not influence the gut microbiota” |

| Dewulf 2013 [12] | “Maltodextrin has a taste and appearance similar to Synergy 1 and has been used as a placebo for ITF in previous studies” |

| Waitzberg 2013 [96] | “Maltodextrin is an easily absorbed and digested carbohydrate not fermented by colonic bacteria and does not interfere with the microbial ecology of the gastrointestinal tract, or with gut metabolism and function” |

| Waitzberg 2012 [43] | “Maltodextrin is an easily absorbed and digested carbohydrate that escapes bacterial fermentation in the colon & does not interfere in microbial ecology of gastrointestinal tract, metabolism, and function” |

|

| |

| Studies that acknowledge with their data that MDX effect is not that of a ‘placebo’ | |

|

| |

| Berding 2021 [64] | “Although maltodextrin is frequently used as the placebo in various studies, it can readily be digested and thus might have psychological and physiological effects, potentially impacting some outcomes measures of this study.” The cited ref. showed that MDX can produce similar metabolic and cognitive effects to those of sucrose in rats |

| Childs 2014 [94] | “It is possible that the MDX control itself exerted effects on the parameters measured, and data indicate that changes occurring in the placebo group may be driving some of the treatment effects observed on HDL-cholesterol concentrations” “it cannot be excluded that the effects observed on NKT cells were in part influenced by the apparent increase in cell-surface marker expression during the MDX supplementation period” |

One RCT stated that MDX is not associated with “harm or benefits”, however no supporting citation was provided. Nine RCTs justified MDX as placebo based on the rationale that it is digested in the human small intestine and not fermented by colonic bacteria. Three RCTs used MDX because it was used in previous similar human trials. Overall, most researchers just use MDX as a placebo and do not comment on it in their publication

Table 3.

Reported physiological and microbial effects of MDX and re-analysis of published ‘before-after MDX’ data in randomized-placebo-controlled clinical trials (RCT) in humans

| Reported effect of MDX on microbial outcomes* | Reported effect on physiological outcomes | RE-analysis of before-after data MDXa |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Berding 2021 [64] No signif. effect on microbiota profile for before vs after MDX | Acute cold stress significantly increased expression adhesion receptor CD62L on classical monocytes in MDX group but not in participants that received PDX, p = 0.005 | NA |

| Rosli 2021 [33] No signif. effect on microbiota profile for before vs after MDX | Diarrhea occurrence increased from baseline until 45 d (after discontinuation of MDX) | NA |

| Mall 2020 [63] No signif. effect on microbiota composition for before vs. after MDX | Signif. increase gastroduodenal permeability. Before MDX: from 1.69 to 2.26, n.s.****; after MDX from 1.96 to 6.73, p < 0.05 | NA |

| Istas 2019 [42] Signif. Increase in Clostridium XiVb for before vs. after MDX, p = 0.01 | Signif. increase in 1-methylpyrogallol-O-sulfate, 2 h post MDX, & plasma phenylacetic acid 2 h post-MDX on 12 wk | NA |

| Lu 2019 [46] Signif. 6% increase of Firmicutes; 14% reduction in Bacteroidetes for before vs. after MDX | No reported effects | NA |

| Pedret 2019 [14] Signif. reduction in enterotype 1 by – 2% and Akkermansia ssp. Increased by 0.008% for before vs. after MD | No reported effects | NA |

| Soldi 2019 [85] Signif. reduction in Bifidobacterium after MDX and at 14d after starting antibiotic | NA | NA |

| Tandon 2019 [54] Signif. increased microbiome biodiversity before vs. after MDX. MDX decreased Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium: Lactobacillus OTU 77 increased after MDX discontinuation | No reported effects | NA |

| Theou [30] 2019 NA | Signif. increase in frailty index for before vs. after MDX p = 0.012 | NA |

| Drabińska 2018 [41] Clostridium leptum and total bacterial tended to decrease with MDX | Signif. reduction in fecal valeric p = 0.030 and increase by 15% of relative conc. of BCFAs for before vs. after MDX | NA |

| Lonher 2018 [45] The relative abundance of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus decreased in MDX group | No reported effects | NA |

| Sloan 2018 [34] Signif drop in Actinobacteria, and Bifidobacterium, while Deltaproteobacteria, Bilohila, and several Ruminococcaceae significantly increased for before vs. after MDX, p < 0.05 | Signif. decrease in fasting breath hydrogen amounts for before vs after MDX p < 0.05 | NA |

| Azpiroz 2017 [35] No signif. effect on Bifidobacterium for before vs after MDX | Signif. reduction in abdominal girth score for before vs after data MDX p = 0.001 | NA |

| Beaumont 2017 [59] No signif. effect on microbiota composition for before vs after MDX | Increase in butyrate (expressed as a relative proportion of total SCFAs) in the MDX group | NA |

| Nicolucci 2017 [27] Signif. increase in Roseburia spp. for before vs. after MDX p = 0.023 | Signif. increase in BMI, fecal cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid, and serum IL-6 for before vs. after MDX, p < 0.05 | Signif. increase in Roseburia Faecis,98% p = 0.0089 |

| Shulman 201 [36] No signif. effect on gastrointestinal microbiome composition for before vs after MDX | Signif. reduction in percentage of stools rated as constipation for before vs after MDX | NA |

| Clarke 2016 [65] No signif. effect on in Bifidobacterium count for before vs after MDX | Signif. increase in serum IgA, IgM, IgGl, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4, fecal IgG, and IgM, p < 0·05 for before vs after MDX | NA |

| Fernandes 2016 [28] NA | Signif. IL-β reduction after MDX in healthy group, p < 0·05. Larger reduction in CRP/Albumin ratio after MDX in healthy group p = 0.063 vs prebiotic p = 0.190 or symbiotic p = 0.168 | NA |

| Pedersen 2016 [32] No signif. effect on gut microbiota composition for before vs after MDX | Signif. decrease in systolic blood pressure and serum IL-6 for before vs after MDX, p < 0·05 | NA |

| Ruiz 2016 [37] NA | Signif. Increase in left colon transit time for before vs after MDX, p < 0.05 | NA |

| Maldonado-Lobón 2015 [38] Signif. increase in the total bacterial load at 21d for before vs. after MDX p < 0.05 | No reported effects | NA |

| Salazar 2015 [62] No signif. effect on fecal Bifidobacterium before-after MDX | Signif Fecal caproate increased, specifically in five patients of the placebo group | NA |

| Sant Anna 2015 [55] Signif. reduction in lactobacillus for before vs. after MDX, p < 0.05 | No reported effects | NA |

| Windey 2015 [93] Signfi. reduction in the eighty-eight band classes for before vs. after MDX, p = 0.01 | No reported effects | NA |

| Bazzocchi 2014 [40] Fecal Lactobacillus decreased in 8/12 patients for before vs after MDX p > 0.05. BifidobacteriaI DNA content increased in 8/12 patients of MDX | No reported effects | NA |

| Majid 2014 [61] No reported effects | No reported effects | No signif. effect on fecal microbiota for before vs after MDX Signif. increase in fecal valerate p = 0.007 & isovalerate p = 0.0002 |

| Ladirat 2014 [60] No signif. effect on total bacterial and Bifidobacterium counts before vs after MDX | Signif. reduction in butyrate on day 8 in MDX group when compared to day 0 p < 0.05 | NA |

| Vaghef-Mehrabany 2014 [67] NA | Signif increase in serum IL-12 p < 0.05 for before vs after MDX | NA |

| Dewulf 2013 [12] No signif. effect on gut microbiota composition for before vs after MDX | Signfi. difference in the post-OGTT glycaemia, with anincrease occurring in the placebo group | NA |

| Neto 2013 [31] NA | Signif. increase in body weight and suprailiac skinfold after MDX, p < 0.05. 6 out of 7 participants in MDX group had lower, hydration vs. before MDX | NA |

| Iemoli 2012 [66] [67] No signif. effect on fecal microbiota for before vs after MDX | Signif. increase in plasma Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for before vs. after MDX p = 0.004 and 3-mo treatment vs. 2mos after suspension: p = 0.016 | NA |

| Salvini 2011 [11] No signif. effect on Bifidobacterium and Lactobacilli for before vs after MDX | No reported effects | Signif. reduction T lymphocytes with 6mo MDX vs baseline. p = 0.0205 & at 12mos old, after suspension of MDX, vs baseline p = 0.0070 |

| Waitzberg 2012 [43] Signif increase in Clostridium sp. p = 0.047 and Bifidobacterium sp. p = 0.053 for before vs after MDX | Signif increase in fecal isovaleric p = 0.031 | NA |

| Costabile 2010 [44] Signif, increase in Lactobacillus–Enterococcus group before vs. after MDX, p < 0·001 Signif increase in Bacteroides-Prevotella group at washout period vs. MDX p < 0.05 | No reported effects | NA |

| Fastinger 2008 [5] No signif. on fecal total bacterial. Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus for before vs after MDX | Signif. Increase in fecal SCFA for before vs. after MDX and remained higher during the washout period vs. baseline | Signif. increase in fecal total SCFA, acetate, propionate. butyrate after MDX p < 0.05, persisted in washout period p < 0.05 (no butyrate) |

| Kolida 2007 [39] Signif. increase Lactobacillus – Enterococcus before vs after MDX in 29 volunteers, and did not return to baseline during washout p<0.01 | Signif. increase in abdominal pain during MDX compared to washout p = 0.014 | NA |

| Shadid 2007 [68] Maternal: no signif. change in Bifidobacterium and lactobacilli for before vs. after MDX | No reported effects | MDX increased pairwise number of mothers with 17 taxa p = 0.0031 vs. treatment |

| Sathitkowitchai 2021 [75]b Decrease in Chao index before vs after MDX. Ruminococcaceae increased before vs after MDX. Reduction in Bifidobacteriaceae & Enterobacteriaceae after washout vs before MDX | No reported effects | NA |

| Ma 2021 [76]b [Signif. difference in the Aitchison distance between two microbiota communities before vs after MDX. Signif. α-diversity decreased before vs after MDX p < 0.05, but non-signif for probiotic-receivers | No reported effects | NA |

| Calgaro 2021 [77]b Bifidobacterium-related SVs such as SV34-B. Iongum and SV228- Bifidobacterium significantly increased for before vs after MDX | No reported effects | NA |

CRP C-reactive protein, BCFAs Branched-chain fatty acids, BMI Body mass index, n.s. not significant, OGTT oral glucose tolerance test, signif significant, NA data not available for univariate analysis (microbiome/microbiota data not investigated), PDX; Dietary fiber polydextrose

P values as reported

Inferences described from re-analysis of published data. See Methods

Identified via Scopus search

Effect of MDX on human physiological parameters

Supporting concerns regarding the validity of MDX as a placebo, the majority of RCTs (60%, CI 95% = 0.48–0.76; n = 42/70; Fisher-exact p = 0.001, expected < 5/70) reported MDX-induced physiological (38.1%, CI 95% = 0.24–0.54; n = 16/42; p = 0.005, expected < 5/42), microbial metabolite (19%, CI 95% = 0.09–0.34; n = 8/42; p = 0.013, expected < 1/42), or microbiome (50%, CI 95% = 0.09–0.34; n = 21/42; p = 0.0001, expected < 5/42) effects. For instance, the consumption of 3.3 g/d MDX for 16 weeks significantly increased body weight and body mass index in overweight children [27], whereas in healthy individuals, these parameters decreased following 6 g/d MDX for 15 days [28]. When provided for only one day, 24 g of MDX increased satiety and fullness in healthy, overweight and obese men [29]. In elderly individuals, changes in frailty index [30], body weight and suprailiac skinfold thickness [31] were reported following MDX supplementation for 13 weeks (7.5 g/d) and 3 months (dosage not reported), respectively [30, 31].

One RCT showed a significant decrease in systolic blood pressure in men with well-controlled diabetes 2 following 5.5 g/d MDX for 12 weeks [32], while another RCT showed an increase in post-oral glucose tolerance test glycaemia in obese women following 16 g/d MDX for 3 months [12].

Several studies in healthy populations reported changes in gut motility following MDX treatment [33–39], including changes in colonic transit time [37] and colonic volume [34, 37], the latter associated with a significant decrease in fasting breath hydrogen [34]. In another population with impaired handling of gut gas loads, 8 g/d of an oral MDX for 4 weeks significantly reduced the abdominal girth score (p = 0.001) [34].

Of the three RCTs that evaluated diarrhea and constipation, one reported increased diarrhea following MDX at dosages of 20 g/d [33]. Of the two RCTs that evaluated constipation, one reported a significant reduction in constipation score (Agachan–Wexner) combined with an increased percentage of spontaneous bowel movements in tertiary care constipated patients after 5.6 g/d MDX [40]. The other RCT reported a significant reduction in the percentage of stools rated as constipation in children with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [36].

Effect of MDX on gut microbiome

Of the thirty-four RCTs studies which evaluated the effect of MDX on gut microbiota, 61.8% (n = 21/34) reported MDX-induced alterations in taxa profiles. Of these, one reported a decrease in total bacterial load, following 12 weeks of 7 g/d MDX in pediatric Celiac disease patients on a gluten-free diet [41]. In contrast, total bacterial load increased following 3 daily pills of MDX (dosage not reported) for 3 weeks in lactating women [38].

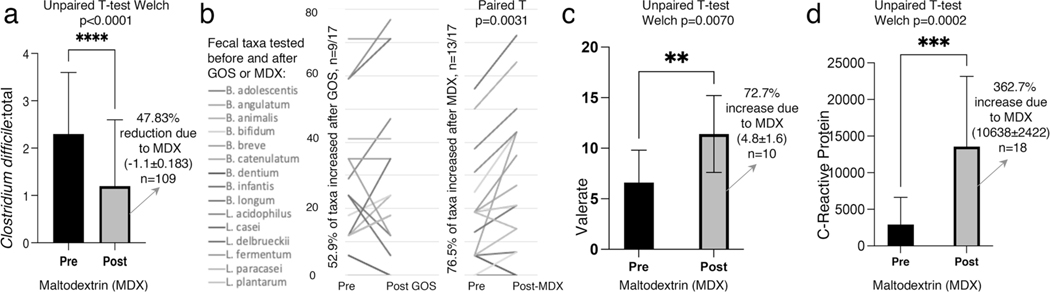

Nine studies (n = 10/21, 47.6%) reported MDX-induced changes in Firmicutes, however, the direction of effect varied. Six studies reported a significant increase in various Firmicutes members following MDX dosages ranging between 0.5 and 15 g/d for 1–16 weeks [27, 34, 39, 42–44]. In one study, increases in Ruminococcaceae (Firmicutes), Anaerotruncus, Flavonifractor, Oscillibacter, and Oscillospira, occurred after one week of MDX + low FODMAP diet (vs baseline) [34]. However, one pediatric RCT reported that 7 g/d of MDX for 12 weeks significantly decreased the relative abundance of Clostridium leptum [41], while another study (6 g/d MDX for 24 weeks) reported decreases in C. Perfringens and C. difficile [45], suggesting that MDX effect varies based on the duration of administration (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Example of ‘before-and-after’ data re-analysis to illustrate the significant effect of MDX on the human immunological markers and gut microbiome. a MDX significantly reduced total Clostridium difficile in healthy children who consumed 6g/d digestible MDX for 24-weeks (vs baseline)[45]. b Reanalysis of individual paired data from Shadid et al. [68] revealed that 6g/d digestible MDX for 15-weeks given for pregnant women from gestation week 25 until delivery increased proportion of specific Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus (p = 0.0031). c Fecal valerate increased in adult ICU patients given an enteral nutrition formulation containing 4.5g/L of prebiotics + 7g/d MDX for at least 7 days. Published data from Majid et al. [61]. d MDX (12g/d, for at least 5 days) significantly increased Creactive protein (CRP) in head and neck cancer surgical patients. Published data from Lages et al. [87]

While none of the latter studies reported concomitant changes within Bacteroidetes [27, 34, 39, 41–44], other studies have reported MDX-induced alterations in the phylum, albeit the direction of the effect varied based on dosage and duration of administration. For example, Bacteroidetes abundance decreased by 14% in healthy adults given 5 g/d MDX for 2 weeks [46]. In another study, higher MDX doses (10 g/d) given to healthy adults for 3 weeks significantly increased the Bacteroides–Prevotella abundance at the washout period [44]. In both studies, MDX administration was associated with increased Firmicutes [44, 46].

The F:B ratio is a relevant marker of gut dysbiosis [24, 47], and several pathological conditions [48, 49] such as obesity (increased F:B ratio) [50] and IBD (reduced F:B ratio) [51]. Of the sixty-one total studies, none reported the F:B ratio before vs. after MDX consumption. However, we were able to infer the F:B ratio from studies that reported both, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, phyla. Five RCTs reported significant increases in Firmicutes with no changes within the Bacteroidetes, suggesting increase in the F:B ratio [27, 34, 39, 42]. Similar findings were reported in another RCT, albeit these did not reach statistical significance [46]. In contrast, one RCT reported a significant decrease in Firmicutes with no changes within Bacteroidetes, indicating a reduction in F:B ratio [41].

Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium are health-promoting [52], immunomodulatory bacteria [53]. Of the seven studies that reported alterations in Lactobacillus, 42.9% (n = 3/7) found that MDX, in dosages ranging from 10 to 25 g/d, for as little as 30 days up to three months respectively, significantly reduced Lactobacillus abundance in healthy adults [54] and constipated patients [55]. Similar findings were reported in other studies, although these did not reach statistical significance [40]. Two studies, wherein MDX (8–10 g/d) was given for 2 or 3 weeks, reported increases in Lactobacillus [44] and Lactobacillus-Enterococcus [39].

Alterations in Proteobacteria were reported in two RCTs. In one study, total Enterobacteriaceae was significantly reduced in healthy children after 6 g/d of MDX for 24 weeks [45]. However, in another RCT, Bilophila and Deltaproteobacteria significantly increased in healthy adults following 1 week of 14 g/d MDX plus low FODMAP diet [34]. Together, findings on microbiome responses suggest that the effect of MDX varies with the diet.

Effect of MDX on microbial metabolites

Of the thirty-nine RCTs which evaluated MDX effect on microbial parameters, 19% (n = 8) reported MDX-induced alterations in microbial metabolites. SCFAs, products of non-digestible carbohydrate fermentation by gut bacteria [55], are known to play key roles in maintaining gut homeostasis through different mechanisms (i.e., anti-inflammatory [56], maintaining the integrity of intestinal barrier [57] mucus production [58]). In healthy adults, MDX (15 g/d, 3 weeks) increased fecal levels of the SFCAs acetate and propionate, an effect which continued through the washout period [5]. The effect of MDX on butyrate levels has varied between studies. In overweight individuals, fecal butyrate levels increased following an MDX dosage providing 15% of their own energy intake for 3 weeks [59]. However, in another study, when given at lower dosages (7.5 g/d) for a shorter period of time (12 days) butyrate levels decreased in healthy individuals [60]. Of note, in the latter study, participants were given 1125 mg amoxicillin for 5 days at the beginning of the study making results difficult to interpret.

In constipated females, MDX (15 g/d, 3 weeks) increased fecal isovaleric levels [43], whereas fecal valerate and isovalerate levels increased in adult ICU patients given an MDX-containing enteral nutrition formulation for 7 days [61] (Table 3). In another study, reductions in fecal valeric acid were associated with a 15% increase in branched-chain fatty acids in pediatric Celiac disease patients on a gluten-free diet + 7 g/d MDX for 12 weeks [41]. In obese women, MDX (16 g/d for 3 months) increased fecal caproate levels compared to women given a prebiotic treatment [62].

Bile acids mediate intestinal homeostasis and inflammatory diseases by regulating gut microbiota [48]. In the context of primary bile acids, cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid significantly increased in overweight and obese children who consumed 3.3 g/d MDX for 16 weeks [27].

Effect of MDX on intestinal or immunological parameters

Overall, 23.8% of the RCTs (n = 10/42) reported MDX-induced alterations in immunological parameters. In one study, MDX (12 g/d) increased gastroduodenal permeability in healthy elderly adults challenged with indomethacin [63]. In healthy females, a study assessing the response of human volunteers to a cold pressor test, MDX treatment (12.5 g/d) significantly increased expression of adhesion receptor CD62L on classical monocytes [64]. In healthy adults, MDX (15 g/d) for 4 weeks significantly increased serum IgA, IgM, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4, fecal IgG and IgM [65], whereas in adult atopic dermatitis patients, plasma lipopolysaccharide (LPS) increased after 12 weeks of MDX, and levels remained higher 2 months after MDX discontinuation (vs baseline) [66]. In infants, milk formula containing 8 g MDX/L for 6 weeks reduced T lymphocytes, which persisted until the 12 months of age following MDX discontinuation [11].

Long-term MDX consumption provided either in dosages of 3.3 g/d or in capsule format (dosage not reported) was found to increase serum proinflammatory cytokine levels in overweight children (IL-6) [27] and adult rheumatoid arthritis patients (IL-12) [67]. By contrast, decreased serum IL-6 following 5.5 g/d MDX for 12 weeks was observed in men with well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus [32]. In another RCT, 6 g/d of MDX for 15 days reduced plasma IL-1b and serum CRP/Albumin ratio in healthy adults (p = 0.063) [28].

Discussion

In this systematic review comparing ‘before vs. after MDX’ published data, we found, across several outcomes, evidence questioning the validity of MDX as placebo/control in human RCTs. Over 63% of the studies reported changes due to MDX, while the remaining reported no effects. This variable presentation of biological or clinical effects may be attributed to differences in the molecular structure of MDX, the dosage/duration of treatment and the disease populations studied. We found that consumption of digestible MDX at various dosages affected microbiome, immunological markers, and other measured clinical outcomes. We also found heterogeneity within our primary and secondary outcomes irrespective of the MDX dosage, duration of administration, age or gender of participants. Of note, it is important to highlight that the MDX effects observed in our analysis, comparing before and after supplementation, is a phenomenon that could also be observed in other treatment groups if external factors are not controlled. Under appropriate study design, significant results would only be possible to be observed due to the true effect of the compound given to participants (e.g., MDX), and/or due to the effect of a non-controlled external factor synchronically influencing all participants in the treated group within the ‘before-after’ time frame of the study (e.g., a weather effect); the latter which is very unlikely to occur since participant recruitment often takes time to complete for most RCTs, making treatment evaluation not synchronized for all participants. Although we have examined the statistical influence of randomness in statistical reproducibility, it is unlikely that the observed effects for MDX are random, since the allocation of random factors also unique to each participant (i.e., diet, lifestyle) are also unlikely.

In the case of MDX-infant studies, it is important to consider that the net effect from MDX as a placebo may be attributed, at least in part, to changes in gut microbiota and gut physiology which occur in infants following birth and throughout childhood, and which are primarily mediated by diet changes, physical activity, and exposure to environmental microorganisms. Herein, we acknowledged that such complexity confounds the effect of the placebo MDX in infant and toddler clinical trials [68, 69]. In the case where capsules are used as the delivery method for MDX, we noted that few studies reported the MDX concentration per volume of capsule. Nevertheless, the MDX dosage is expected to differ from that of the treatments because prebiotics/probiotics per volume would occupy a major fraction of the capsule rendering the total volume of MDX per day significantly lower [42, 67]. For example, if a fixed number of capsule/powder volume are needed per participant (e.g., 1-cm3), there would likely be differences for MDX between ‘capsule 1’ lyophilized bacteria volume + MDX volume, and ‘capsule 2’ with only MDX volume.

The use of MDX has increased markedly in the United States and the global market over the past decades. In a 2015 survey of grocery store ingredients, Nickerson et al., found that 60% of all packaged items included “maltodextrin” or “modified (corn, wheat, etc.) starch” in their ingredients list [70]. Moreover, they showed a positive correlation between the increasing dietary prevalence of MDX and a dramatic rise in IBD incidence in Rochester, NY [70, 71]. In this regard, the safety of such widely spread additive needs to be formally revisited, especially in people with susceptibility to digestive diseases, such as IBD, which may exert prominent responses.

Although our analysis was focused on studies examining microbiological factors (microbiome, or Bacteroide*), we used a narrative review of studies on nutrition and dietary fibers [72] to identify RCTs reporting before-after data for MDX to validate observations identified in our search. Of assurance, RCTs in the field of nutrition science have also documented the effect of MDX in breath analysis [73], body weight [73, 74], and glucose concentrations [74] in agreement with our findings.

To further validate our results, we lastly updated the search to identify new studies prior to manuscript acceptance. After screening 32 titles/abstracts for eligibility on Nov 23 2021, a total of nine RCTs (n = 9) were included in the analysis. Overall, three new RCTs (n = 3) reported gut microbiome changes due to MDX compared to baseline data. Of these, two RCTs reported that placebo MDX significantly decreased alpha diversity in both stressed and healthy adults (e.g.; increase of Ruminococcaceae after 10 g/d MDX for 3 weeks) [75, 76]. Supporting our concerns regarding the validity of MDX as a placebo, Calgaro et al. observed a bifidogenic effect of MDX in a 6-week RCT where 2.5 g/d of MDX was used as control [77]. They found that some Bifidobacterium-related strains such as structural variants (SVs) SV34-B.longum and SV228-Bifidobacterium significantly increased in the MDX cohort. These results are in line with data reported in a previous work [78] where authors observed that the majority of the culturable bifidobacterial strains (including 10 strains of B. longum) were capable of growing in MDX rich media. As a result, Calgaro et al., recommended that MDX bifidogenic effect needs to be deeply evaluated in future clinical trials [77], since MDX is broadly used as placebo.

In addition to the net effect that MDX has on hots as a function of dose, and/or diet or lifestyle, it is important to highlight that the variability of MDX structures available in the market could also play a role on the net effects reported. MDX structure-effect relationships, not thoroughly discussed, could hypothetically help explain studies reporting opposing results; e.g., increasing vs. decreasing specific bacterial taxa.

In conclusion, MDX can induce various modifications in gut microbiota configurations, and immunological factors. Our findings question the validity of using MDX as a placebo in human clinical trials. As placebos are supposed to be pharmaceutically non-influential substances on body functions, it would be important in the future to consider and revise the ethical possibility of using a group of study participants receiving no-supplementation (or possible water) to help determine the biochemical role of tested compounds in biochemical/immunological body functions. Our data also question the appropriateness of using MDX as a widely used food additive. Since MDX as a filler contributes to a large fraction of the volume in numerous processed foods or supplements, our findings highlight the need to reassess the impact of this compound on human intestinal health.

Supplementary Material

Funding

Research was supported by the NIH grant DK055812, DK091222 and DK097948 (to FC), F32DK117585 and K01DK127008–01 (to AB), and P01DK091222 Germ-free and Gut Microbiome Core and R21DK118373 (to ARP).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-022-02802-5.

Code availability Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Chronakis IS (1998) On the molecular characteristics, compositional properties, and structural-functional mechanisms of maltodextrins: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 38(7):599–637. 10.1080/10408699891274327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okuma K, Matsuda I (2003) Production of indigestible dextrin from pyrodextrin. J Appl Glycosci 50(3):389–394 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyazato S, Kishimoto Y, Takahashi K, Kaminogawa S, Hosono A (2016) Continuous intake of resistant maltodextrin enhanced intestinal immune response through changes in the intestinal environment in mice. Biosci Microbiota Food Health 35(1):1–7. 10.12938/bmfh.2015-009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang S, Zhang S, Huang S, Wu Z, Pang J, Wu Y, Wang J, Han D (2020) Resistant maltodextrin alleviates dextran sulfate sodium-induced intestinal inflammatory injury by increasing butyric acid to inhibit proinflammatory cytokine levels. Biomed Res Int 2020:7694734. 10.1155/2020/7694734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fastinger ND, Karr-Lilienthal LK, Spears JK, Swanson KS, Zinn KE, Nava GM, Ohkuma K, Kanahori S, Gordon DT, Fahey GC Jr (2008) A novel resistant maltodextrin alters gastrointestinal tolerance factors, fecal characteristics, and fecal microbiota in healthy adult humans. J Am Coll Nutr 27(2):356–366. 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CFR - Code of Federal Regulations. FDA Title 21, volume 3, part 184, subpart B, section 184.1444. Three Code of Federal Regulations. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/cfrsearch.cfm?fr=184.1444. Accessed May 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta U, Verma M (2013) Placebo in clinical trials. Perspect Clin Res 4(1):49–52. 10.4103/2229-3485.106383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofman DL, van Buul VJ, Brouns FJ (2016) Nutrition, health, and regulatory aspects of digestible maltodextrins. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 56(12):2091–2100. 10.1080/10408398.2014.940415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truman Megan, Raremark Community Manager. What is a placebo and why are they used in clinical trials? (2021). Accessed 15 Apr 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boos W, Shuman H (1998) Maltose/maltodextrin system of Escherichia coli: transport, metabolism, and regulation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62(1):204–229. 10.1128/MMBR.62.1.204-229.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salvini F, Riva E, Salvatici E, Boehm G, Jelinek J, Banderali G, Giovannini M (2011) A specific prebiotic mixture added to starting infant formula has long-lasting bifidogenic effects. J Nutr 141(7):1335–1339. 10.3945/jn.110.136747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dewulf EM, Cani PD, Claus SP, Fuentes S, Puylaert PG, Neyrinck AM, Bindels LB, de Vos WM, Gibson GR, Thissen JP, Delzenne NM (2013) Insight into the prebiotic concept: lessons from an exploratory, double blind intervention study with inulin-type fructans in obese women. Gut 62(8):1112–1121. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corsello G, Carta M, Marinello R, Picca M, De Marco G, Micillo M, Ferrara D, Vigneri P, Cecere G, Ferri P, Roggero P, Bedogni G, Mosca F, Paparo L, Nocerino R, Berni Canani R (2017) Preventive effect of cow’s milk fermented with Lactobacillus paracasei CBA L74 on common infectious diseases in children: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. 10.3390/nu9070669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedret A, Valls RM, Calderon-Perez L, Llaurado E, Companys J, Pla-Paga L, Moragas A, Martin-Lujan F, Ortega Y, Giralt M, Caimari A, Chenoll E, Genoves S, Martorell P, Codoner FM, Ramon D, Arola L, Sola R (2019) Effects of daily consumption of the probiotic Bifidobacterium animalis subsp lactis CECT 8145 on anthropometric adiposity biomarkers in abdominally obese subjects: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 43(9):1863–1868. 10.1038/s41366-018-0220-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreno-Perez D, Bressa C, Bailen M, Hamed-Bousdar S, Naclerio F, Carmona M, Perez M, Gonzalez-Soltero R, Montalvo-Lominchar MG, Carabana C, Larrosa M (2018) Effect of a protein supplement on the gut microbiota of endurance athletes: A randomized, controlled, double-blind pilot study. Nutrients. 10.3390/nu10030337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eid N, Osmanova H, Natchez C, Walton G, Costabile A, Gibson G, Rowland I, Spencer JP (2015) Impact of palm date consumption on microbiota growth and large intestinal health: a randomised, controlled, cross-over, human intervention study. Br J Nutr 114(8):1226–1236. 10.1017/S0007114515002780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowan NJ, Anderson JG (1997) Maltodextrin stimulates growth of Bacillus cereus and synthesis of diarrheal enterotoxin in infant milk formulae. Appl Environ Microbiol 63(3):1182–1184. 10.1128/aem.63.3.1182-1184.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh P, Sanchez-Fernandez LL, Ramiro-Cortijo D, OchoaAllemant P, Perides G, Liu Y, Medina-Morales E, Yakah W, Freedman SD, Martin CR (2020) Maltodextrin-induced intestinal injury in a neonatal mouse model. Dis Model Mech. 10.1242/dmm.044776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laudisi F, Di Fusco D, Dinallo V, Stolfi C, Di Grazia A, Marafini I, Colantoni A, Ortenzi A, Alteri C, Guerrieri F, Mavilio M, Ceccherini-Silberstein F, Federici M, MacDonald TT, Monteleone I, Monteleone G (2019) The food additive maltodextrin promotes endoplasmic reticulum stress-driven mucus depletion and exacerbates intestinal inflammation. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 7(2):457–473. 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nickerson KP, Homer CR, Kessler SP, Dixon LJ, Kabi A, Gordon IO, Johnson EE, de la Motte CA, McDonald C (2014) The dietary polysaccharide maltodextrin promotes Salmonella survival and mucosal colonization in mice. PLoS ONE 9(7):e101789. 10.1371/journal.pone.0101789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Reprint–preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Phys Ther 89(9):873–880 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falagas ME, Pitsouni EI, Malietzis GA, Pappas G (2008) Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. Faseb J 22(2):338–342. 10.1096/fj.07-9492LSF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deering KE, Devine A, O’Sullivan TA, Lo J, Boyce MC, Christophersen CT (2019) Characterizing the composition of the pediatric gut microbiome: a systematic review. Nutrients. 10.3390/nu12010016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kabeerdoss J, Jayakanthan P, Pugazhendhi S, Ramakrishna BS (2015) Alterations of mucosal microbiota in the colon of patients with inflammatory bowel disease revealed by real time polymerase chain reaction amplification of 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid. Indian J Med Res 142(1):23–32. 10.4103/0971-5916.162091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basson A, Gomez-Nguyen A, LaSalla A, Butto L, Kulpins D, Warner A, DiMartino L, Ponzani G, Osme A, Rodriguez-Palacios A (2021) Replacing animal protein with soy-pea protein in an ‘American diet’ controls Murine Crohn’s disease-like Ileitis regardless of Firmicutes: bacteroidetes ratio. J Nutr. 10.1093/jn/nxaa386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez-Palacios A, Mo KQ, Shah BU, Msuya J, Bijedic N, Deshpande A, Ilic S (2020) Global and historical distribution of clostridioides difficile in the human diet (1981–2019): systematic review and meta-analysis of 21886 samples reveal sources of heterogeneity, high-risk foods, and unexpected higher prevalence toward the tropic. Front Med (Lausanne) 7:9. 10.3389/fmed.2020.00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicolucci AC, Hume MP, Martinez I, Mayengbam S, Walter J, Reimer RA (2017) Prebiotics reduce body fat and alter intestinal microbiota in children who are overweight or with obesity. Gastroenterology 153(3):711–722. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernandes R, Beserra BT, Mocellin MC, Kuntz MG, da Rosa JS, de Miranda RC, Schreiber CS, Frode TS, Nunes EA, Trindade EB (2016) Effects of prebiotic and synbiotic supplementation on inflammatory markers and anthropometric indices after Roux-enY gastric bypass: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Clin Gastroenterol 50(3):208–217. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Beek CM, Canfora EE, Kip AM, Gorissen SHM, Olde Damink SWM, van Eijk HM, Holst JJ, Blaak EE, Dejong CHC, Lenaerts K (2018) The prebiotic inulin improves substrate metabolism and promotes short-chain fatty acid production in overweight to obese men. Metabolism 87:25–35. 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Theou O, Jayanama K, Fernandez-Garrido J, Buigues C, Pruimboom L, Hoogland AJ, Navarro-Martinez R, Rockwood K, Cauli O (2019) Can a prebiotic formulation reduce frailty levels in older people? J Frailty Aging 8(1):48–52. 10.14283/jfa.2018.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neto JV, De Melo CM, Riberiro SM (2013) Effects of three-month intake of synbiotic on inflammation and body composition in the elderly: a pilot study. Nutrients 4(4):1276–1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedersen C, Gallagher E, Horton F, Ellis RJ, Ijaz UZ, Wu H, Jaiyeola E, Diribe O, Duparc T, Cani PD, Gibson GR, Hinton P, Wright J, La Ragione R, Robertson MD (2016) Host-microbiome interactions in human type 2 diabetes following prebiotic fibre (galacto-oligosaccharide) intake. Br J Nutr 116(11):1869–1877. 10.1017/S0007114516004086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosli D, Shahar S, Manaf ZA, Lau HJ, Yusof NYM, Haron MR, Majid HA (2021) Randomized controlled trial on the effect of partially hydrolyzed guar gum supplementation on Diarrhea frequency and gut microbiome count among pelvic radiation patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 45(2):277–286. 10.1002/jpen.1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sloan TJ, Jalanka J, Major GAD, Krishnasamy S, Pritchard S, Abdelrazig S, Korpela K, Singh G, Mulvenna C, Hoad CL, Marciani L, Barrett DA, Lomer MCE, de Vos WM, Gowland PA, Spiller RC (2018) A low FODMAP diet is associated with changes in the microbiota and reduction in breath hydrogen but not colonic volume in healthy subjects. PLoS ONE 13(7):e0201410. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azpiroz F, Molne L, Mendez S, Nieto A, Manichanh C, Mego M, Accarino A, Santos J, Sailer M, Theis S, Guarner F (2017) Effect of chicory-derived inulin on abdominal sensations and bowel motor function. J Clin Gastroenterol 51(7):619–625. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shulman RJ, Hollister EB, Cain K, Czyzewski DI, Self MM, Weidler EM, Devaraj S, Luna RA, Versalovic J, Heitkemper M (2017) Psyllium fiber reduces abdominal pain in children with irritable bowel syndrome in a randomized, double-blind trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 15(5):712–719. 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.03.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abellan Ruiz MS, Barnuevo Espinosa MD, Contreras Fernandez CJ, Luque Rubia AJ, Sanchez Ayllon F, Aldeguer Garcia M, Garcia Santamaria C, Lopez Roman FJ (2016) Digestion-resistant maltodextrin effects on colonic transit time and stool weight: a randomized controlled clinical study. Eur J Nutr 55(8):2389–2397. 10.1007/s00394-015-1045-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maldonado-Lobon JA, Diaz-Lopez MA, Carputo R, Duarte P, Diaz-Ropero MP, Valero AD, Sanudo A, Sempere L, Ruiz-Lopez MD, Banuelos O, Fonolla J, Olivares Martin M (2015) Lactobacillus fermentum CECT 5716 reduces staphylococcus load in the breastmilk of lactating mothers suffering breast pain: a randomized controlled trial. Breastfeed Med 10(9):425–432. 10.1089/bfm.2015.0070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kolida S, Meyer D, Gibson GR (2007) A double-blind placebo-controlled study to establish the bifidogenic dose of inulin in healthy humans. Eur J Clin Nutr 61(10):1189–1195. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bazzocchi G, Giovannini T, Giussani C, Brigidi P, Turroni S (2014) Effect of a new synbiotic supplement on symptoms, stool consistency, intestinal transit time and gut microbiota in patients with severe functional constipation: a pilot randomized double-blind, controlled trial. Tech Coloproctol 18(10):945–953. 10.1007/s10151-014-1201-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drabinska N, Jarocka-Cyrta E, Markiewicz LH, Krupa-Kozak U (2018) The effect of oligofructose-enriched inulin on faecal bacterial counts and microbiota-associated characteristics in celiac disease children following a gluten-free diet: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients. 10.3390/nu10020201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Istas G, Wood E, Le Sayec M, Rawlings C, Yoon J, Dandavate V, Cera D, Rampelli S, Costabile A, Fromentin E, Rodriguez-Mateos A (2019) Effects of aronia berry (poly)phenols on vascular function and gut microbiota: a double-blind randomized controlled trial in adult men. Am J Clin Nutr 110(2):316–329. 10.1093/ajcn/nqz075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Linetzky Waitzberg D, Alves Pereira CC, Logullo L, Manzoni Jacintho T, Almeida D, Teixeira da Silva ML, de Miranda M, Torrinhas RS (2012) Microbiota benefits after inulin and partially hydrolized guar gum supplementation: a randomized clinical trial in constipated women. Nutr Hosp 27(1):123–129. 10.1590/S0212-16112012000100014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Costabile A, Kolida S, Klinder A, Gietl E, Bauerlein M, Frohberg C, Landschutze V, Gibson GR (2010) A double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study to establish the bifidogenic effect of a very-long-chain inulin extracted from globe artichoke (Cynara scolymus) in healthy human subjects. Br J Nutr 104(7):1007–1017. 10.1017/S0007114510001571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lohner S, Jakobik V, Mihalyi K, Soldi S, Vasileiadis S, Theis S, Sailer M, Sieland C, Berenyi K, Boehm G, Decsi T (2018) Inulin-type fructan supplementation of 3- to 6-year-old children is associated with higher fecal bifidobacterium concentrations and fewer febrile episodes requiring medical attention. J Nutr 148(8):1300–1308. 10.1093/jn/nxy120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu QY, Rasmussen AM, Yang J, Lee RP, Huang J, Shao P, Carpenter CL, Gilbuena I, Thames G, Henning SM, Heber D, Li Z (2019) Mixed spices at culinary doses have prebiotic effects in healthy adults: a pilot study. Nutrients. 10.3390/nu11061425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodriguez-Palacios A, Harding A, Menghini P, Himmelman C, Retuerto M, Nickerson KP, Lam M, Croniger CM, McLean MH, Durum SK, Pizarro TT, Ghannoum MA, Ilic S, McDonald C, Cominelli F (2018) The artificial sweetener splenda promotes gut proteobacteria, dysbiosis, and myeloperoxidase reactivity in Crohn’s disease-like ileitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 24(5):1005–1020. 10.1093/ibd/izy060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Begley M, Gahan CG, Hill C (2005) The interaction between bacteria and bile. Fems Microbiol Rev 29(4):625–651. 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stojanov S, Berlec A, Strukelj B (2020) The influence of probiotics on the firmicutes/bacteroidetes ratio in the treatment of obesity and inflammatory bowel disease. Microorganisms. 10.3390/microorganisms8111715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ley RE, Backhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI (2005) Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(31):11070–11075. 10.1073/pnas.0504978102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gophna U, Sommerfeld K, Gophna S, Doolittle WF, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ (2006) Differences between tissue-associated intestinal microfloras of patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J Clin Microbiol 44(11):4136–4141. 10.1128/JCM.01004-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Amara AA, Shibl A (2015) Role of Probiotics in health improvement, infection control and disease treatment and management. Saudi Pharm J 23(2):107–114. 10.1016/j.jsps.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cristofori F, Dargenio VN, Dargenio C, Miniello VL, Barone M, Francavilla R (2021) Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of probiotics in gut inflammation: a door to the body. Front Immunol 12:578386. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.578386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tandon D, Haque MM, Gote M, Jain M, Bhaduri A, Dubey AK, Mande SS (2019) A prospective randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response relationship study to investigate efficacy of fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) on human gut microflora. Sci Rep 9(1):5473. 10.1038/s41598-019-41837-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Sant’Anna MSL, Rodrigues VC, Araujo TF, de Oliveira TT, do Peluzio MCG, de Ferreira CLLF(2015) Yacon-based product in the modulation of intestinal constipation. J Med Food 18(9):980–986. 10.1089/jmf.2014.0115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tan J, McKenzie C, Potamitis M, Thorburn AN, Mackay CR, Macia L (2014) The role of short-chain fatty acids in health and disease. Adv Immunol 121:91–119. 10.1016/B978-0-12-800100-4.00003-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vernia P, Marcheggiano A, Caprilli R, Frieri G, Corrao G, Valpiani D, Di Paolo MC, Paoluzi P, Torsoli A (1995) Short-chain fatty acid topical treatment in distal ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 9(3):309–313. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00386.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peng L, Li ZR, Green RS, Holzman IR, Lin J (2009) Butyrate enhances the intestinal barrier by facilitating tight junction assembly via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in Caco-2 cell monolayers. J Nutr 139(9):1619–1625. 10.3945/jn.109.104638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beaumont M, Portune KJ, Steuer N, Lan A, Cerrudo V, Audebert M, Dumont F, Mancano G, Khodorova N, Andriamihaja M, Airinei G, Tome D, Benamouzig R, Davila AM, Claus SP, Sanz Y, Blachier F (2017) Quantity and source of dietary protein influence metabolite production by gut microbiota and rectal mucosa gene expression: a randomized, parallel, double-blind trial in overweight humans. Am J Clin Nutr 106(4):1005–1019. 10.3945/ajcn.117.158816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ladirat SE, Schoterman MH, Rahaoui H, Mars M, Schuren FH, Gruppen H, Nauta A, Schols HA (2014) Exploring the effects of galacto-oligosaccharides on the gut microbiota of healthy adults receiving amoxicillin treatment. Br J Nutr 112(4):536–546. 10.1017/S0007114514001135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Majid HA, Cole J, Emery PW, Whelan K (2014) Additional oligofructose/inulin does not increase faecal bifidobacteria in critically ill patients receiving enteral nutrition: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Nutr 33(6):966–972. 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salazar N, Dewulf EM, Neyrinck AM, Bindels LB, Cani PD, Mahillon J, de Vos WM, Thissen JP, Gueimonde M, de Los Reyes-Gavilan CG, Delzenne NM (2015) Inulin-type fructans modulate intestinal Bifidobacterium species populations and decrease fecal short-chain fatty acids in obese women. Clin Nutr 34(3):501–507. 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ganda Mall JP, Fart F, Sabet JA, Lindqvist CM, Nestestog R, Hegge FT, Keita AV, Brummer RJ, Schoultz I (2020) Effects of dietary fibres on acute indomethacin-induced intestinal hyperpermeability in the elderly: a randomised placebo controlled parallel clinical trial. Nutrients. 10.3390/nu12071954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berding K, Long-Smith CM, Carbia C, Bastiaanssen TFS, van de Wouw M, Wiley N, Strain CR, Fouhy F, Stanton C, Cryan JF, Dinan TG (2021) A specific dietary fibre supplementation improves cognitive performance-an exploratory randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Psychopharmacology 238(1):149–163. 10.1007/s00213-020-05665-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clarke ST, Green-Johnson JM, Brooks SP, Ramdath DD, Bercik P, Avila C, Inglis GD, Green J, Yanke LJ, Selinger LB, Kalmokoff M (2016) beta2–1 Fructan supplementation alters host immune responses in a manner consistent with increased exposure to microbial components: results from a double-blinded, randomised, cross-over study in healthy adults. Br J Nutr 115(10):1748–1759. 10.1017/S0007114516000908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iemoli E, Trabattoni D, Parisotto S, Borgonovo L, Toscano M, Rizzardini G, Clerici M, Ricci E, Fusi A, De Vecchi E, Piconi S, Drago L (2012) Probiotics reduce gut microbial translocation and improve adult atopic dermatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 46(Suppl):S33–40. 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31826a8468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vaghef-Mehrabany E, Alipour B, Homayouni-Rad A, Sharif SK, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Zavvari S (2014) Probiotic supplementation improves inflammatory status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition 30(4):430–435. 10.1016/j.nut.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shadid R, Haarman M, Knol J, Theis W, Beermann C, Rjosk-Dendorfer D, Schendel DJ, Koletzko BV, Krauss-Etschmann S (2007) Effects of galactooligosaccharide and long-chain fructooligosaccharide supplementation during pregnancy on maternal and neonatal microbiota and immunity–a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Clin Nutr 86(5):1426–1437. 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pastor-Villaescusa B, Hurtado JA, Gil-Campos M, Uberos J, Maldonado-Lobon JA, Diaz-Ropero MP, Banuelos O, Fonolla J, Olivares M, Group P (2020) Effects of Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 Lc40 on infant growth and health: a randomised clinical trial in nursing women. Benef Microbes 11(3):235–244. 10.3920/BM2019.0180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nickerson KP, Chanin R, McDonald C (2015) Deregulation of intestinal anti-microbial defense by the dietary additive, maltodextrin. Gut Microbes 6(1):78–83. 10.1080/19490976.2015.1005477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stowe SP, Redmond SR, Stormont JM, Shah AN, Chessin LN, Segal HL, Chey WY (1990) An epidemiologic study of inflammatory bowel disease in Rochester, New York Hospital incidence. Gastroenterol 98:104–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wanders AJ, van den Borne JJ, de Graaf C, Hulshof T, Jonathan MC, Kristensen M, Mars M, Schols HA, Feskens EJ (2011) Effects of dietary fibre on subjective appetite, energy intake and body weight: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev 12(9):724–739. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00895.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pasman W, Wils D, Saniez MH, Kardinaal A (2006) Long-term gastrointestinal tolerance of NUTRIOSE FB in healthy men. Eur J Clin Nutr 60(8):1024–1034. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Parnell JA, Reimer RA (2009) Weight loss during oligofructose supplementation is associated with decreased ghrelin and increased peptide YY in overweight and obese adults. Am J Clin Nutr 89(6):1751–1759. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sathitkowitchai W, Suratannon N, Keawsompong S, Weerapakorn W, Patumcharoenpol P, Nitisinprasert S, Nakphaichit M (2021) A randomized trial to evaluate the impact of copra meal hydrolysate on gastrointestinal symptoms and gut microbiome. PeerJ 9:e12158. 10.7717/peerj.12158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ma T, Jin H, Kwok LY, Sun Z, Liong MT, Zhang H (2021) Probiotic consumption relieved human stress and anxiety symptoms possibly via modulating the neuroactive potential of the gut microbiota. Neurobiol Stress 14:100294. 10.1016/j.ynstr.2021.100294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]