Abstract

The elderly are particularly susceptible to infectious and neoplastic diseases of the lung and it is unclear how lifelong exposure to environmental pollutants affects respiratory immune function. In an analysis of human lymph nodes (LNs) from 84 organ donors aged 11-93years, we found a specific age-related decline in lung-associated, but not gut-associated, LN immune function linked to the accumulation of inhaled atmospheric particulate matter. Increasing densities of particulates were found in lung-associated LNs with age, but not in the corresponding gut-associated LNs. Particulates were specifically contained within CD68+CD169− macrophages, which exhibited reduced activation, phagocytic capacity, and altered cytokine production compared to non-particulate-containing macrophages. The structures of B cell follicles and lymphatic drainage were disrupted in lung-associated LN with particulates. Our results reveal that the cumulative effects of environmental exposure with age may compromise immune surveillance of the lung via direct effects on immune cell function and lymphoid architecture.

The demographics of the world population are rapidly changing, such that individuals 65 years or older are projected to represent over 20% of the population by 20501. As the majority of healthcare costs, morbidity, and mortality from diseases are experienced by individuals greater than 55 years of age2, there is a need to better understand the mechanisms by which aging increases disease susceptibility. In particular, there is a significant and striking increase in both the incidence and severity of diseases of the lung and respiratory tract with age. In particular, the elderly are at increased risk for lung damage and severe outcomes from infection with respiratory viruses such influenza3 and SARS-CoV-2, where mortality from infection for individuals >75 years was more than 80 fold greater than younger adults4-6. Moreover, neoplastic disease of the lung, including small cell lung cancer mostly affects individuals older than 60 years of age7.

Senescent changes in the immune system have been implicated in the increased disease burden in the elderly. With age, immune cells and functional mediators undergo intrinsic alterations leading to reduced adaptive immune responses, increased inflammation8,9, and reduced regulation10, thus impairing anti-pathogen and anti-tumor immunity. However, the mechanisms for the biased decline in respiratory immunity over age are not known. In addition, aging and its effects on the respiratory tract are shaped by prolonged exposure to the environment through inhalation11,12, though the role of environmental insults in age-associated impairments of the immune system is not well understood.

Studies of immunosenescence in humans mostly sample blood as the most accessible site. However, immune responses occur in mucosal and barrier sites of infection and associated lymphoid organs. For responses to respiratory infections, lung-associated lymph nodes (LLNs) are crucial for adaptive immune responses to new and recurring pathogens as demonstrated in mouse models13,14. Antigens encountered in the lung enter the LLN via lymphatics where adaptive immune responses are initiated including T cell priming and interactions with B cells in specialized lymphoid follicles to promote humoral immunity. Age-associated effects on LN have been identified in mice15 and morphological changes with age have been reported in human LN16,17; however, analysis of human LN aging and its effect on immune responses and functionality has not been examined. As part of their role in immune surveillance, LNs also filter impurities from tissues through lymphatics18,19, though the impact of this broader role for LN on human immune responses remains unexplored. Here, we took an anatomical approach to investigate the cellular, structural, and functional niches of tissue-draining LNs over age in samples obtained from human organ donors, revealing localized, age-associated changes in lung-associated LN due to accumulation of inhaled atmospheric particulates from environmental pollutants.

Results

Atmospheric particulates accumulate in lung-associated LNs

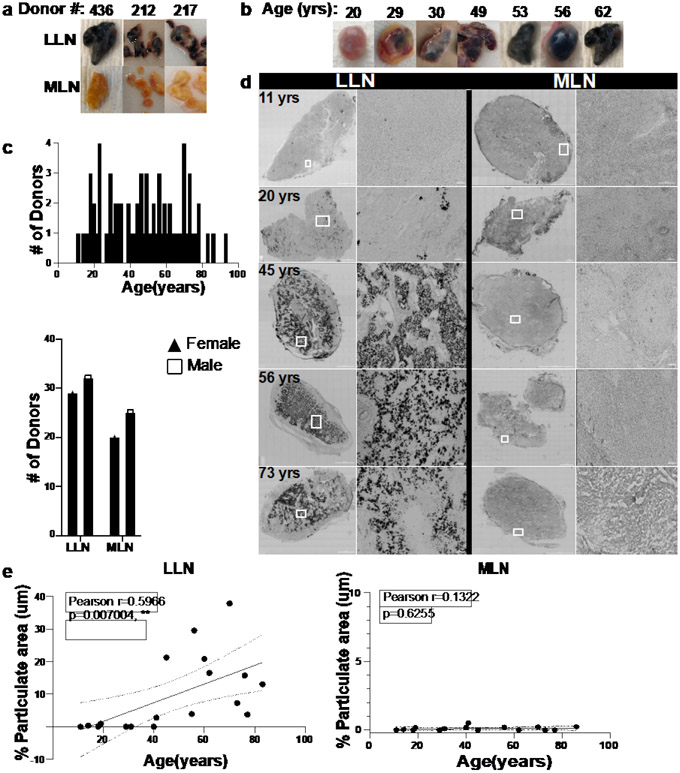

We obtained multiple LN samples associated with lungs and intestines from human organ donors (see Methods), through a human tissue resource we established involving collaborations with organ procurement organizations as previously described20. Based on our acquisition of tissues from hundreds of organ donors of all ages (with no history of smoking) over the past decade21-25, we consistently observed differences in the appearance of lymph nodes associated with the lung and gut, respectively. Here, we show that lung-associated LNs (LLNs) are black in color, while mesenteric LNs (MLNs) from the same individual are beige or translucent in color (Fig. 1a), similar to mouse LNs. Comparing LNs from donors of different ages revealed that black LLNs were observed in the majority of adult donors after the third decade of life but were less prevalent in younger donors (<30years) (Fig. 1b). Black particulates are present in the atmosphere and consist of different polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) derived from environmental pollutants such as motor vehicle exhaust, heating, and wildfires12,26. We therefore hypothesized that inhaled atmospheric particulates and their accumulation with age may result in specific alterations to immune function and architecture of the LLN.

Fig.1. Lung-associated lymph nodes accumulate carbon particulates with age.

a. Photos show gross anatomy of lung-associated lymph node (LLN) (top) and mesenteric (gut-associated) LN (MLN, bottom) dissected from lungs and intestine samples. b. Appearance of whole LLN over age. c. Donors used in this study stratified by age (upper) and sex for each site (lower). d. Brightfield confocal images of human LLNs on the left column (left: whole LN section stitched together from 70-400 single 20X images; right: magnified section as outlined in white box) and mesenteric LNs (MLN) on the right column (left: whole LN section stitched together from 70-400 single 20X images; right: magnified section as outlined in white box) obtained from organ donors of indicated ages. Black regions show particulate contents. Representative images were taken from 5-7 donors (LLN) and 4-6 donors (MLN) per age group (≤39,40-64 and ≥65 yrs). Scale bar: 1500 um (whole LN section), 100 and 50 um (single images). e. Particulate content in LNs quantified by measuring the area (μm2) of each LN which contained black particulates. Imaging data quantified using Imaris software. Linear regression with Pearson correlation (two-tailed). Significance for LLN: P=0.007004; MLN: P=0.6255. Data presented as the mean ± 95% CI. Data from 16-19 donors per site. Pearson r, **P < 0.005

We took a quantitative imaging approach to assess the impact of age and inhaled particulates on LN structure and function in lung- and gut-associated LNs (LLN and MLN) from a cohort of 84 organ donors aged 11-93 years, distributed equally between male and females, with no documented history of heavy smoking (>20 packs for one year or longer; see Methods for criteria) (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Table 1). We imaged whole LN sections by confocal microscopy, stitching together multiple (70-400) 20x single images (see methods) for quantifying the structural and cellular changes between sites and over age. Bright field images showed increased particulate matter with age specifically in LLNs, which was most notable at age 40 years and older, while MLNs from each corresponding donor did not exhibit particulates at any age (Fig. 1d, e). This age-related accumulation of carbon in the LLN was similar between males and females (Extended Data Fig. 1), suggesting environmental effects localized to the LLN draining the respiratory tract irrespective of sex.

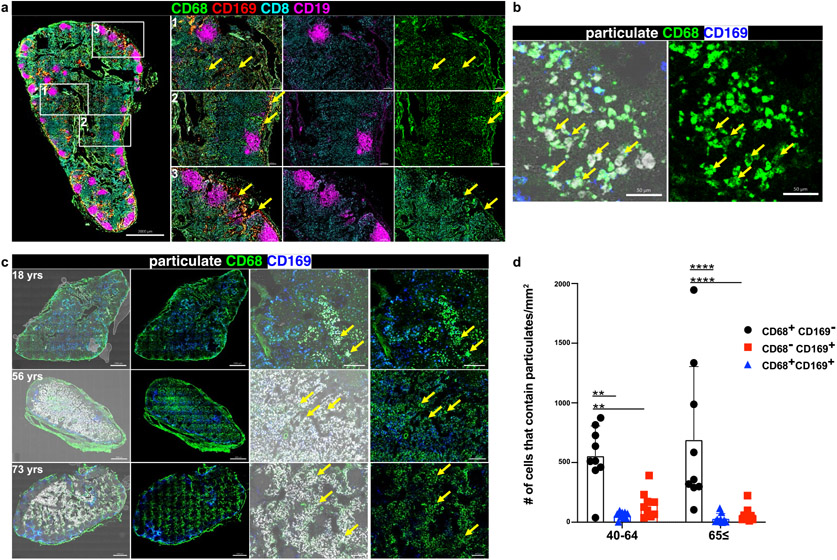

Uptakes of particulates by CD68+CD169− macrophages in LLNs

LNs are comprised of densely packed immune cells that are organized in defined structural niches. B cells are organized in follicles that in humans are arranged in the periphery and throughout the organ (Fig. 2a, magenta), while CD8+T cells are situated around and outside follicles delineating the T cell zone (Fig. 2a, cyan). LN macrophages, as defined in mouse models, are subdivided into different subsets based on their localization within the T cell zone, subcapsular region, or within follicles27,28. To define macrophage populations and their localization in human LN, we stained LN sections with CD68, a scavenger receptor expressed by tissue or migratory macrophages29 and CD 169, a sialic acid receptor expressed by tissue resident and subcapsular macrophages in mucosal and lymphoid sites, respectively30-32. In human LNs, we observed CD68+ macrophages distributed within the T cell zone and in the subcapsular region around follicles (Fig. 2a, region 1 and 2), while CD169 expression distinguished subcapsular and medullary from T cell zone macrophages (Fig. 2a; compare regions 1, 2, and 3). Three subsets of macrophages could be distinguished based on coordinate expression of CD68 and CD169: CD68+CD169− macrophages were mostly found in the T cell zone (Fig. 2a, region 1, green), CD68+CD169+ macrophages were in the subcapsular sinus (region 2, yellow), and CD68−CD169+ macrophages were in the medullary sinus (region 3, red). Human LN therefore contain macrophages distributed in all regions with specific subsets in T cell zones and subcapsular regions.

Fig. 2. The CD68+CD169− subset of LN macrophages localize within the T cell zone and contain particulates.

a. Confocal images of LLN immunostained for CD68 (green), CD169 (red), CD8 (cyan), and CD19 (magenta) (left: whole LN section stitched together from 70-400 single 20X images; right: magnified sections as outlined in white box). Each row with magnified images shows the localization of different macrophage subsets (1:CD68+CD169−;2:CD68+CD169+;3:CD68-CD169+). Scale bar: 2000 um (whole LN section), 200 um (single image). b. Confocal image of human LLNs stained for CD68 and CD169 to show macrophage subsets, and black particulate matter localization (bright field microscopy, white). Representative images were taken from 6 donors. Scale bar: 50 um. c. Confocal image of human LLNs (left two columns: whole LN section, stitched together from 70-400 single 20X images; right two columns: magnified sections) stained for CD68, and CD169 to show black particulate matter accumulation in different macrophage subsets of indicated ages. Whole LN images and magnified sections both shown with overlay of brightfield (left columns) to indicate localization of particulates (white). Representative images were taken from 6-9 donors per age group (≤39, 40-64 and ≥65 yrs). Scale bar: 1000 um (whole LN section), 200 um (single images). d. Graphs show the macrophage subsets that contain particulates (<3um) for different age groups calculated using Imaris software. Data presented as the mean ± SD. Data from 18 donors. two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posttest, **P < 0.0021, ***P < 0.0002, ****P < 0.0001. Significance for 40-64: CD68+CD169− vs. CD68+CD169+ P=0.0012, CD68+CD169− vs. CD68−CD169+ P=0.0083; 65≤: CD68+CD169− vs. CD68+CD169+ P=<0.0001, CD68+CD169− vs. CD68−CD169+ P=<0.0001.

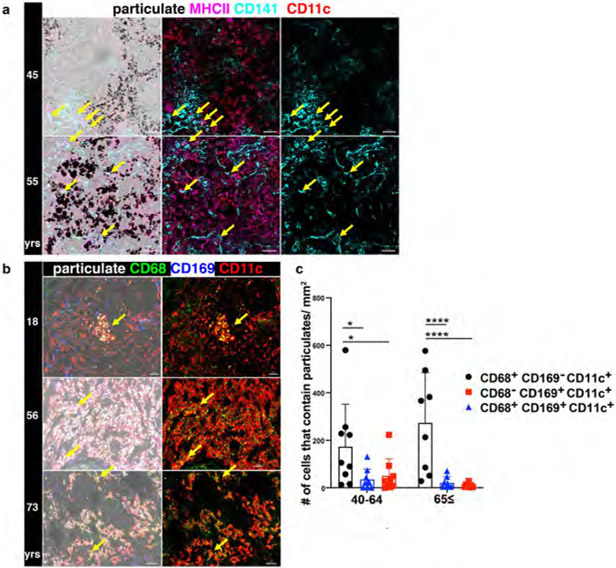

We hypothesized that particulates would be contained within innate immune cells with the capacity to engulf foreign antigens through phagocytosis. In the LN, phagocytic cells are mostly comprised of macrophages and/or dendritic cells (DC), as neutrophils and monocytes are not significantly represented in LN21,23. Comparison of brightfield images (particulates) with fluorescent staining of lineage markers in LN reveals that particulates are contained within macrophages (CD68+ cells) and not within dendritic cells (CD11c+HLA-DR+CD141+ cells) (Fig. 2b & Extended Data Fig. 2a). We further investigated whether particulates were contained within specific macrophages subsets. By quantitative imaging analysis of whole LN, we found the majority of particulates was contained within CD68+CD169− macrophages (Fig. 2c, d), which also expressed CD11c (Extended Data Fig. 2b, 2c), a phenotypic feature of T cell zone macrophages (TCZM) in mice27,33. We did not find significant particulates in subcapsular (CD68+CD169+) and medullary (CD68−CD169+) macrophages. Together, these results suggest that TCZM are the predominant subset containing particulate matter within LLNs, consistent with the role of this subset as scavengers for dying and dead cells33.

Particulates impair macrophage phagocytosis and turnover

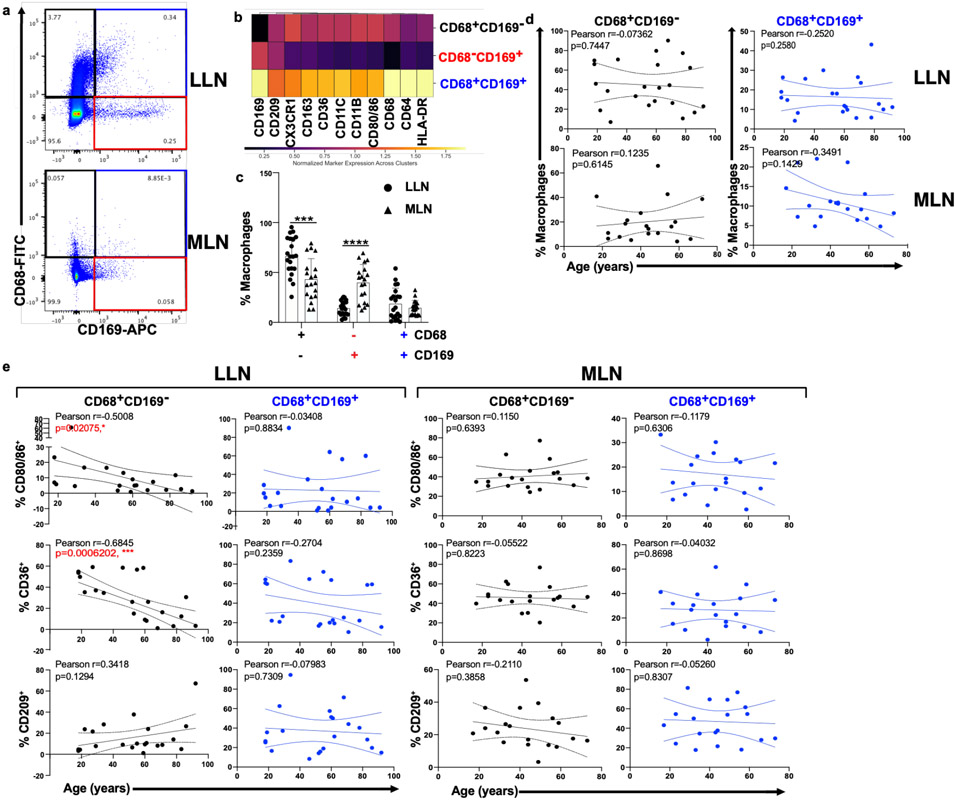

In tissues, macrophages are strategically localized to serve as a gatekeeper to phagocytose pathogens, dead cells or debris. We investigated whether the increased presence of particulates with age in TCZM in the LLN would result in altered activation, phagocytic capacity, and/or turnover. We used flow cytometry to assess markers of activation and phagocytosis for macrophage subsets in LLN and MLN of organ donors aged 18-92 years, to control for effects of subset, site, age, and particulate content. The flow cytometry panel for analysis contained markers for lineage (CD64, CD6829,34, CD11c, CD11b) tissue residence (CD16335, CD16930-32, CX3CR136,37), activation (HLA-DR, CD80, CD86), and phagocytosis --including the scavenger receptor CD36, important for uptake of apoptotic cells and bacteria38 and CD209 (DC-SIGN1), a marker of phagocytic capacity for pathogens39.

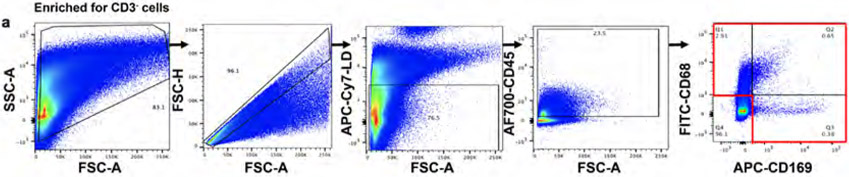

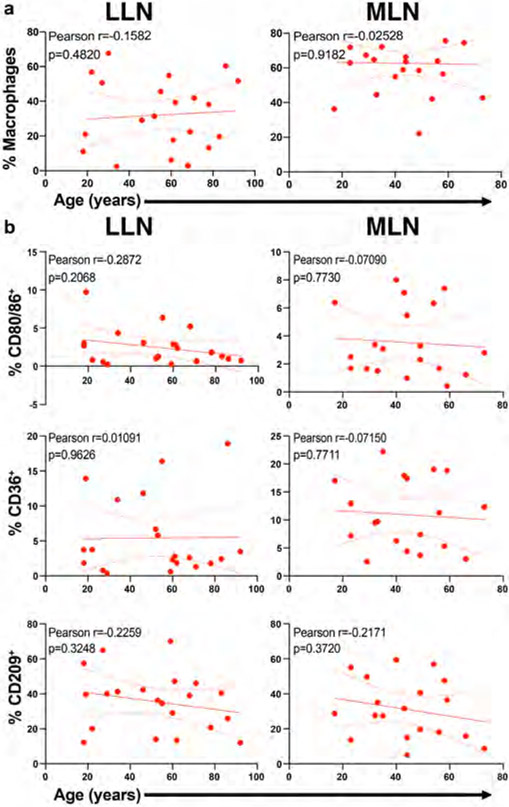

Consistent with our imaging data, three major macrophage subsets were delineated based on CD68 and CD169 expression (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 3 (gating strategy)); each subset differed in expression of phenotypic markers for macrophage subsets (CD64, CD11c, CD11b, CD163, CX3CR1), localization (CX3CR1), and function (CD209, HLA-DR, CD36, CD80/86) (Fig. 3b). We identified differences in the composition of macrophage subsets between LLN and MLN; there was an increased frequency of CD68+CD169− macrophages in LLNs compared to MLNs and the frequency of these subsets in each site did not change with age (Fig. 3c, d; Extended Data Fig. 4a). However, the expression of key activation markers, CD80 and CD86, and the phagocytic marker CD36 decreased with age specifically in CD68+CD169− macrophages in the LLN but not in the MLN (Fig. 3e), nor in CD68+CD169+ subcapsular and CD68−CD169+ medullary sinus macrophages in either LLN or MLN (Fig. 3e, Extended Data Fig. 4b). By contrast, CD209 expression was not altered significantly with age in any macrophage subset in either site (Fig. 3e, Extended Data Fig. 4b). These results show while the frequency of LN macrophage subsets are largely maintained over age, the expression of functional markers specifically by the CD68+CD169− subset within the LLN declined with age, suggesting particulates may have specific effects on macrophage function.

Fig. 3. Particulate-containing CD68+CD169− macrophages are increased in LLN and exhibit declining function over age.

a. Expression of CD68 and CD169 gated on live, singlet, and CD45+CD3−cells showing CD68+CD169− (black rectangle), CD68-CD169+ (red rectangle), and CD68+CD169+ (blue rectangle) macrophage subsets. b. Differential expression of indicated markers by the three macrophages subsets compiled from LLN shown in a heat map. c. Frequency of macrophage subsets in LLN (n=21) and MLN (n=19). Mixed effects analysis with Tukey’s posttest. Data presented as the mean ± SD. Significance for CD68+CD169− LLN vs. MLN: P=0.0004, CD68−CD169+ LLN vs. MLN: P=<0.0001, CD68+CD169+ LLN vs. MLN: P=0.9458. d. Frequency of macrophage subsets in LLN (n=21) and MLN (n=19) over age. Linear regression with Pearson correlation (two-tailed). Significance for LLN: CD68+CD169− P=0.7447, CD68+CD169+ P=0.2580; MLN: CD68+CD169− P=0.6145, CD68+CD169+ P=0.1429. Pearson r, *P < 0.033, **P < 0.005 and ***P < 0.001. Data presented as the mean ± 95% CI e. Expression of functional markers CD80/86, CD36, and CD209 by LN CD68+CD169− (first and third column) and CD68+CD169+ (second and fourth column) macrophage subsets in LLNs (n=22, first and second column) and MLNs (n=21, third and fourth columns) over age. Linear regression with Pearson correlation (two-tailed). Significance for LLN: CD68+CD169− of % CD80/86+ P=0.02075, CD68+CD169− of % CD36+ P=0.0006202, CD68+CD169− of % CD209+ P=0.1294, CD68+CD169+ of % CD80/86+ P=0.8834, CD68+CD169+ of % CD36+ P=0.2359, CD68+CD169+ of % CD209+ P=0.7309; MLN: CD68+CD169− of % CD80/86+ P=0.6393, CD68+CD169− of % CD36+ P=0.8223, CD68+CD169− of % CD209+ P=0.3858, CD68+CD169+ of % CD80/86+ P=0.6306, CD68+CD169+ of % CD36+ P=0.8698, CD68+CD169+ of % CD209+ P=0.8307. Pearson r, *P < 0.033, **P < 0.005 and ***P < 0.001. Data presented as the mean ± 95% CI.

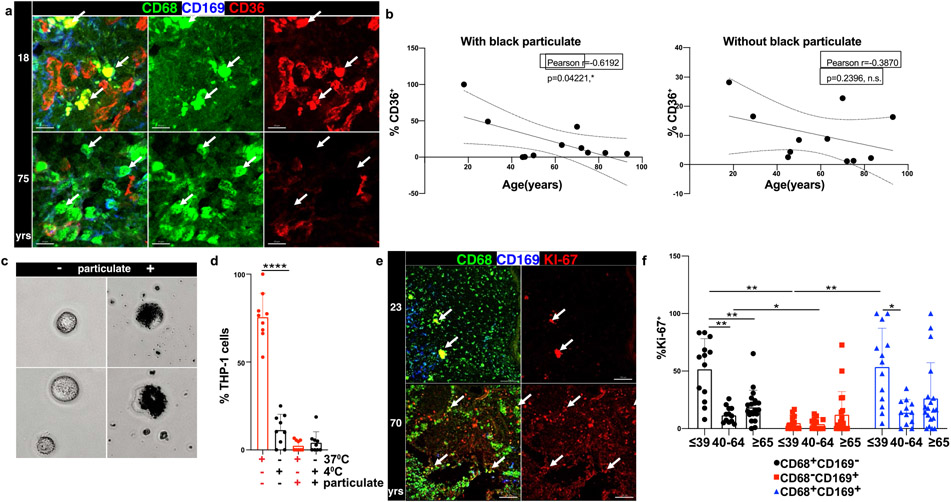

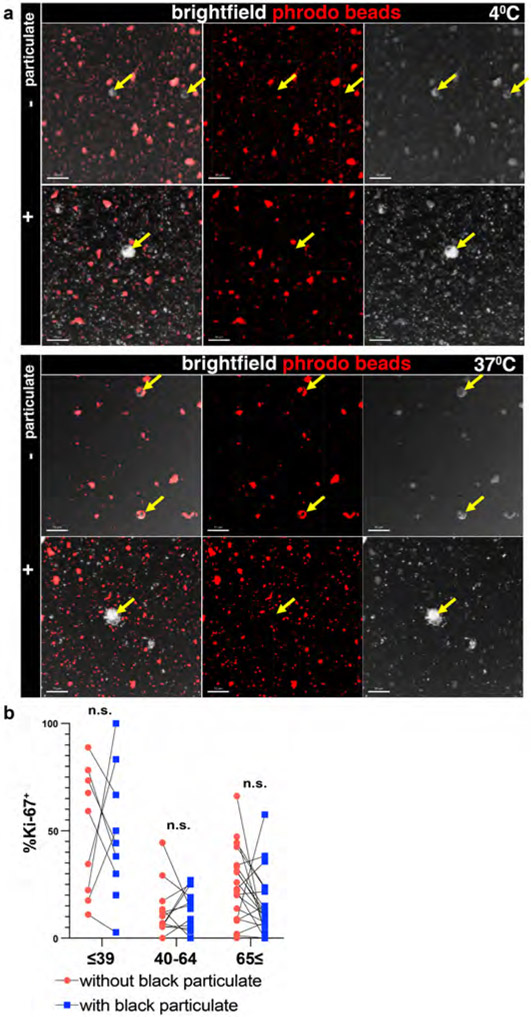

We investigated the direct effect of particulates on phagocytic capacity by imaging and functional assays. The reduction in CD36 expression with age in LLN CD68+CD169− macrophages as measured by flow cytometry was also observed by imaging (Fig. 4a) and specifically in CD68+CD169− macrophages containing particulates but not in CD68+CD169− macrophages without particulates (Fig. 4b). To directly assess whether particulate uptake by macrophages would inhibit phagocytosis, we performed phagocytic assays using the THP-1 human macrophage cell line exposed to carbon particulates isolated from urban environmental sources (See Methods). THP-1 cells readily take up these atmospheric black particulates within 6 hrs (Fig. 4c), demonstrating the efficiency of macrophage-mediated surveillance. Using an in vitro phagocytic assay for uptake of fluorescent bioparticles consisting of bacteria with a pH-sensitive dye that fluoresces when phagocytosed (see methods), we found a significant reduction in phagocytosis by particulate-containing compared to non-particulate-containing THP-1 cells (Fig. 4d, Extended Data 5a). These results show that particulate uptake by macrophages can directly impact the phagocytic function of macrophages important for scavenging and maintenance of tissue homeostasis.

Fig.4. Particulate-containing CD68+CD169− macrophages have diminished phagocytosis.

a. Confocal image of human LLNs stained for CD68, CD36, and CD169 from donors of indicated ages. White arrows show representative CD68+CD169− macrophages and CD36 expression in LN from a representative young and older donor. Representative images were taken from 5-6 donors per age group (≤65 and ≥65 yrs). Scale bar: 15 um. b. Graph shows frequency of CD36+CD68+CD169− macrophages over age stratified by those with (left) or without (right) black particulates (n=11). Calculations were made using Imaris software. Linear regression with Pearson correlation (two-tailed). Significance for %CD36+ with black particulate P=0.04221, without black particulate P=0.2396. Pearson r, *P < 0.033 Data presented as the mean ± 95% CI. c. THP-1 macrophages can phagocytose black particulates. Differentiated THP-1 cells were incubated with or without black particulates for 6 hours. Representative images shows the ≥4μm size black particulates within macrophages (n=3 wells/condition, 3 images/well). d. Particulate-containing THP-1 macrophages exhibit reduced phagocytosis. Differentiated THP-1 cells previously incubated with or without black particulates were cultured with pHrodo beads at 37°C or 4°C for 90 minutes, and phagocytic uptake was determined by confocal microscopy (2-3 images per well). Graph shows frequency of THP-1 cells containing beads for each well and condition, representative of two experiments. (n=9-12 wells/condition). Significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posttest, ****P < 0.0001. 37°C: % THP-1 with phrodo beads with vs. without particulates P=<0.0001. e. Differential proliferation of macrophages in LLN with age. Confocal image of human LLNs stained for CD68, Ki-67 and CD169; white arrows show Ki-67+ macrophages. Representative images were taken from 6-7 donors (2-4 images/donor) per age group (≤65 and ≥65 yrs). Scale bar: 100μm. f. Graph shows frequency of proliferating (Ki-67+) cells for each macrophage subset for different age groups calculated using Imaris software. Significance for CD68+CD169− ≤39 vs. CD68+CD169− 40-64 P=0.004, CD68+CD169− ≤39 vs. CD68+CD169− ≥65 P=0.0095, CD68+CD169− 40-64 vs. CD68-CD169+ 40-64 P=0.0373, CD68+CD169− ≤39 vs. CD68-CD169+ ≤39 P=0.0023, CD68−CD169+ ≤39 vs. CD68+CD169+ ≤39 P=0.0071. Data presented as the mean ± SD. Data are from 13 donors (2-7 single images for each donor). Mixed effects analysis with Tukey’s posttest, *P < 0.04, **P < 0.0021.

The reduction in phagocytic function and recycling of the membrane suggested that particulates may also affect the ability of tissue macrophages to undergo proliferative turnover for replenishment or maintenance40. We assessed Ki-67 expression in situ as a marker of proliferating cells (Fig. 4e, f). In LN samples from younger donors (≤39 years), the number of proliferating CD68+CD169− and CD68+CD169+ macrophages was greater than the number of CD68−CD169+ macrophages. By contrast, CD68+CD169− macrophages from older donors (≥65 years) had significantly reduced proliferation independent of particulate content (Fig. 4f). CD68+CD169− macrophages with or without particulates did not show a direct correlation (Extended Data Fig. 5b). The reduced proliferation of CD68+CD169− macrophage subsets in older individuals (independent of particulates) suggests that particulates do not affect turnover, but rather reduced turnover is a potential mechanism for the accumulation of particulates within macrophages at older ages.

Particulates alter cytokine production by macrophages

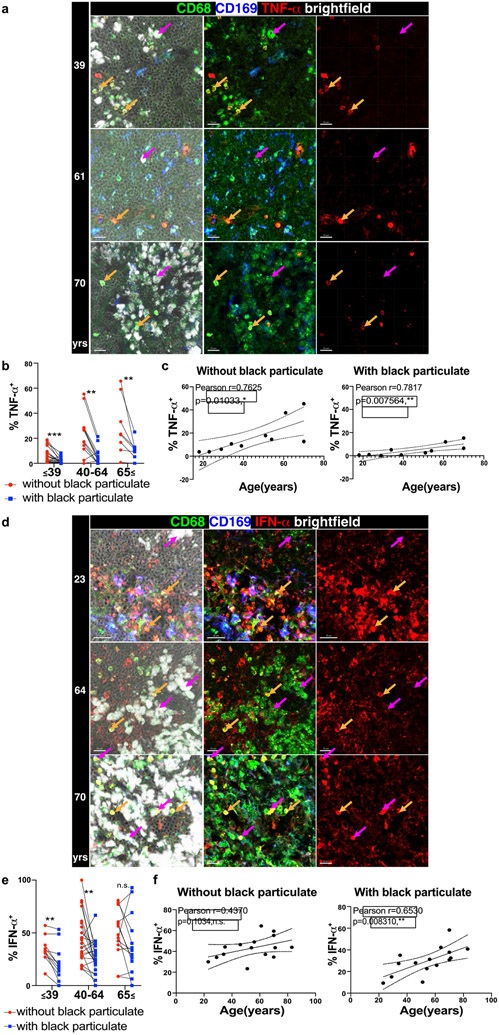

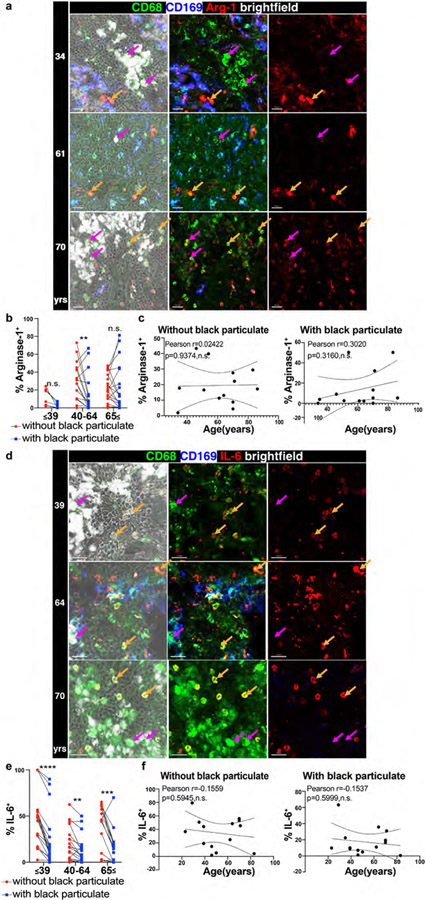

Macrophages also elicit critical innate immune functions through the secretion of multiple pro-inflammatory and regulatory cytokines and mediators41. In order to define how particulate content affects macrophage-derived cytokine production, we stained LLN sections with antibodies to macrophages-derived factors including the anti-viral cytokine IFN-α, proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6, and the anti-inflammatory mediator Arginase42. We previously found that human LLN exhibit ongoing immune activity compared to other LN sites23, enabling in situ examination of cytokine production. To dissect the individual contributions of particulates and age in macrophage function, we measured cytokine production by CD68+CD169− macrophages with and without particulates in the LLN across all adult ages (Fig. 5, Extended data Fig. 6). For each parameter measured, we performed a multivariable regression analysis to control for particulate and age effects (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 5. Particulate-containing CD68+CD169− macrophages exhibit altered cytokine production.

a. Confocal image of human LLNs stained for CD68, CD169, and TNF-α from donors of different ages indicated to the left of the image. Arrows show representative CD68+CD169− macrophages (magenta: CD68+CD169− macrophages with particulates; orange: CD68+CD169− macrophages without particulates). Representative images were taken from 2-5 donors (3-4 images/donor) per age group (≤39,40-64 and ≥65 yrs). Scale bar: 20 um. b. Graph shows paired frequency of TNF-α+ CD68+CD169− macrophages with or without black particulates calculated using Imaris software. Significance assessed with repeated measures ANOVA. Significance for ≤39yrs P=0.0021, 40-64 years P=0.0018, ≥65yrs P=0.0092. Data are from 10 donors (3-4 single images for each donor). c. Graph shows frequency of TNF-α+ CD68+CD169− macrophages with or without particulates over age calculated using Imaris software. (n=10). Linear regression with Pearson correlation (two-tailed). Significance for % TNF-α+ without black particulate P=0.01033, with black particulate P=0.007564. Pearson r, n.s. Data presented as the mean ± 95% CI. d. Confocal image of human LLNs stained for CD68, IFN-α, and CD169 from donors of indicated ages. Arrows show representative cells from CD68+CD169− macrophages (magenta: CD68+CD169− macrophages with particulates; orange: CD68+CD169− macrophages without particulates). Representative images were taken from 4-6 donors (2-4 images/donor) per age group (≤39,40-64 and ≥65 yrs). Scale bar: 20 um. e. Graph shows paired frequencies of IFN-α+ CD68+CD169− macrophages with or without particulates calculated using Imaris software. Significance assessed with repeated measures ANOVA. Significance for ≤39yrs P=0.0021, 40-64 yrs P=0.0036, ≥65 yrs P=0.4170. Data are from 15 donors (2-4 single images for each donor) f. Graph shows frequency of IFN-α+ CD68+CD169− macrophages with or without particles over age calculated using Imaris software. (n=15). Linear regression with Pearson correlation (two-tailed). Significance for % IFN-α+ without black particulate P=0.1034, with black particulate P=0.008310. Pearson r, *P < 0.04 Data presented as the mean ± 95% CI.

Across ages, macrophages containing particulates exhibited reduced frequencies of cytokine production compared to macrophages without particulates for IFN-α, TNF-α, and IL-6 (Fig. 5a-f, Extended Data Fig. 6a-c, Supplementary Table 1). This finding is consistent with particulates having inhibitory effects on macrophage function. By contrast, Arginase was produced comparably by macrophages containing or lacking particulates (Extended Data Fig. 6d-f). When comparing functional capacity across age, we found three patterns showing differential effects of particulates and age for various mediators. For TNF-α, there was an age-associated increase in frequency of TNF-α+ macrophages independent of particulates though the frequency of TNF-α+ macrophages with particulates was lower at all ages (Fig. 5a-c). Multivariate analysis shows significant, yet independent effects of particulates and age for TNF-α (Supplementary Table 1). For IFN-α-expression, we found a significant increase with age only in the particulate-containing macrophage subset, and multivariate analysis further revealed independent effects of particulates with reduced IFN-α expression in younger ages (Fig. 5d-f), Supplementary Table 1). By contrast, both Arginase and IL-6 did not show age-associated changes in their expression, although IL-6 expression was reduced in particulate- compared to non-particulate containing macrophages (Extended data Fig. 6a-f, Supplementary table 1). Together, these results show independent and synergistic effects of particulates and age on macrophage function in the LLN.

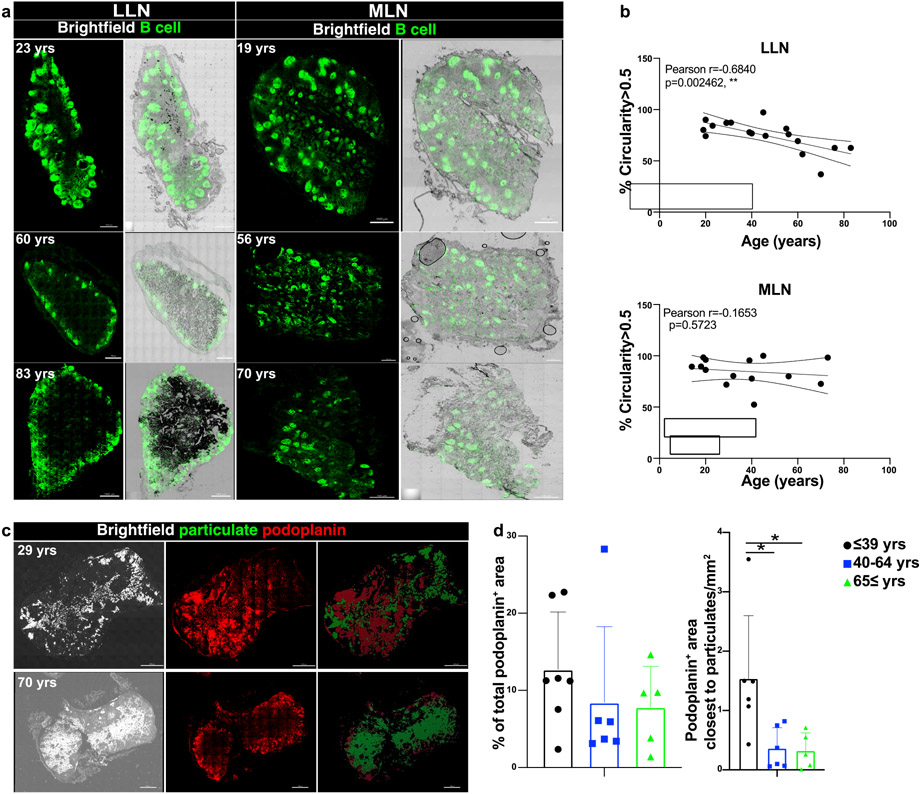

Particulates disrupt LN architecture and lymphatic drainage

Adaptive immune responses are primed within LN follicles where T cells interact with B cells to promote production of antibody secreting plasma cells and memory B cells43. Disruptions of these follicles due to cytokines, chemokines, or infections can lead to a reduced adaptive immune response44,45. In addition, structural connections with lymphatic vessels are important for transit of immune cells throughout tissues and for migration of dendritic cells (DC) from tissues to LNs for T cell priming46. We investigated whether accumulation of carbon particulates in aging LLNs affects LN architecture and immunosurveillance. We observed that B cell follicles in LLNs became more dispersed with age resulting in loss of B cell follicle integrity, as quantified using a computational measure of follicle circularity, while follicles within MLNs did not exhibit significant structural changes with age (Fig. 6a,b). Similarly, assessing lymphatics by staining human LN sections with podoplanin47 (Fig. 6c) revealed a slight reduction in the total lymphatics area in both LLN and MLN with age, which did not achieve significance (Fig. 6d). However, in regions containing particulate matter, there were significantly fewer lymphatic vessels in older compared to younger adults (Fig. 6d). Accumulation of carbon particulates is therefore accompanied by a disruption in LN architecture, affecting follicles and lymphatic drainage, with potential impacts on priming of adaptive immunity and immune surveillance.

Fig. 6. Disrupted LN architecture in the presence of particulate matter.

a. Representative confocal images of whole human LN sections stained for CD20 to show B cell follicles (green) showing with black particulate matter, from donors of indicated ages. Representative images were taken from 3-7 donors (LLN) and 2-8 donors (MLN) per age group (≤39,40-64 and ≥65 yrs). Scale bar: 1000 um. b. B cell circularity measured by using an open-source code (see methods) to quantify the B cell follicle integrity in MLN (n=14) and LLN (n=17). Graphs show the circularity measurement above a threshold (>0.5) for each whole LN section obtained from organ donors of indicated ages. Linear regression with Pearson correlation (two-tailed). Significance for % Circularity>0.5 LLN P=0.002462, MLN P=0.5723. Pearson r, **P < 0.005 Data presented as the mean ± 95% CI. c. Representative confocal images of human LLNs (from donors of indicated ages) stained for podoplanin to show lymphatics (red) with black particulate matter shown as brightfield (white) and pseudocolored green to show overlay with podoplanin (left column: bright field; middle column: podoplanin; right column: particulate matter and lymphatics isosurfaced by using Imaris software). Representative images were taken from 5-12 donors per age group (≤65 and ≥65 yrs). Scale bar: 1000 um. d. Graph on the left shows the area covered by lymphatics in the whole LN section. Graph on the right shows the area covered by lymphatics close to the particulate area (<3um) by using Imaris software. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posttest, *P < 0.04. Significance for Podoplanin+ area closest to particulates ≤39 vs. 40-64 P=0.0257, ≤39 vs. ≥65 P=0.0279. Data presented as the mean ± SD. Data are from 17 donors.

Discussion

Diseases of the lung and respiratory tract disproportionately affect the elderly, including a dramatically increased susceptibility to respiratory infections as observed in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Here, we reveal a new mechanism for compromised respiratory immunity over age due to exposure to inhaled particulates from the environment that have specific effects on the lung-associated lymph nodes, which provide critical immunosurveillance functions. We show that particulates are contained with T cell zone macrophages (TCZM) in the LLN but are not present in TCZM in the gut-associated LN within the same individual. Particulate-containing macrophages exhibit decreased phagocytosis over age, likely due to direct effects of particulates, which also reduces cytokine production and can exacerbate age-associated inflammation. Moreover, increased particulate content after age 40 results in disruption of LN structure and lymphatic connections. Our findings provide evidence for individual and cumulative effects of environmental insults and senescent changes on lung-localized immunity.

Macrophages orchestrate the innate immune response through their phagocytic uptake of pathogens and production of cytokines for immune cell recruitment and initiation of adaptive immunity. They also maintain tissue homeostasis through uptake and elimination of dead cells and debris48,49. Here we provide direct evidence that macrophages take up atmospheric particulates that lodge in the LLN. Whether these macrophages originate in the lung is not known, though the increased prevalence of CD68+CD169− macrophages in LLNs versus MLNs suggests recruitment to the LLN from the lung. Our results also indicate that the fate of particulate-containing macrophages may differ with age. Macrophages in the LNs of younger individuals exhibited higher turnover than those from older individuals, which may facilitate particulate clearance. In this way, young macrophages may be more resilient to detrimental effects of particulate accumulation.

Particulates also have detrimental effects on macrophage function. We showed that a high concentration of particulates can be engulfed by macrophages, which results in impaired phagocytic capacity mediated by direct recognition via scavenger receptors or other non-opsonized pathways. Whether phagocytosis of pathogens and cellular debris or Fc receptor-mediated opsonization are affected remains to be established. We also detected independent effects of particulates on cytokine production by macrophages. Particulate-containing macrophages exhibited lower production of key pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IFN-α, and IL-6 which are essential for innate responses to pathogens. We therefore propose a direct effect of particulates in multiple aspects of macrophage function and turnover. The resultant persistence of functionally impaired macrophages in the lung-associated LN may contribute to the dysregulated innate responses to respiratory pathogens known to occur in the elderly5,50.

We also found disrupted follicular structure and reduced lymphatic connections in LLN with high particulate content, mostly found in individuals greater than 50 years. These results suggest impaired priming of adaptive immune responses for newly encountered respiratory pathogens, which is known to occur with age5. However, the ability of particulate-containing LN to support priming needs to be specifically investigated. Older individuals are intrinsically compromised in their ability to respond to new pathogens due to diminished numbers of naïve T cells and lack of thymic output51. The loss of structural niches for priming in the LLN further exacerbates the impact of these senescent changes on respiratory immunity. In our previous studies, we showed that the proportion of tissue resident memory T cells (TRM) and influenza virus-specific TRM were maintained over age in human lungs, but decreased in frequency in the LLN24,52,53, suggesting that altered LLN architecture also impacts maintenance of memory T cells. Together, our findings indicate that age-associated changes to the immune system are local and anatomical, as well as intrinsic to specific cell types.

Pollution from carbon-based sources is an ongoing and growing threat to the health and livelihood of the world’s population54. The specific effects of pollutants on lung inflammation and asthma in certain individuals or within certain geographic regions has been documented55-57. We demonstrate here through examination of lymphoid tissues, a chronic and ubiquitous impact of pollution on our ability to mount critical immune defense and surveillance of the lung. In this way, the elderly are highly vulnerable to pathogens that infect the respiratory tract, as tragically demonstrated in the COVID-19 pandemic. The effect of pollutants on neurodegenerative disease is also well documented58,59 and neuroinflammation is implicated in this process60. We therefore propose that policies to limit carbon emissions will not only improve the global climate, but also preserve our immune system and its ability to protect against current and emerging pathogens and maintain tissue health and integrity.

In conclusion, our results provide direct evidence that the environment can have cumulative and adverse effects on our immune system with age. We show how environmental pollutants specifically target immune cells within lymphoid organs, which carry out essential immune surveillance functions. These findings can inform how we monitor and study our immune system—in health, disease, and over age.

Methods

Human samples

Lymph node tissues were obtained from brain-dead organ donors through an approved protocol and material transfer agreement with LiveOnNY, the local organ procurement organization for the New York metropolitan area as previously described21,24. Tissues for this study were obtained from donors with no history of asthma and who were negative for SARS-CoV-2, cancer, hepatitis B, C and HIV. We also selected for donors who were indicated in the donor information sheet as being non-smokers and/or with no history of heavy smoking (>20 packs for >1 year or more) where indicated (82/84 donors). The list of donors used in this study, their age and sex is provided in Extended Data Table 1. This study does not qualify as human subjects research because tissues were obtained from deceased (brain dead) organ donors, as confirmed by the Institutional review board (IRB) at Columbia University.

Preparation of cell suspensions from tissue samples

Following procurement, organs were transported to the laboratory and maintained in cold media supplemented with 5% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin, and glutamine (PSQ). LN tissues were dissected out from the lung or intestine, cleaned of fat and connective tissue, chopped into pieces, and incubated with RPMI media (Fisher) containing collagenase D (Sigma) and DNase (Sigma) for 60 minutes at 37°C. Cells were isolated with additional mechanical digestion and density gradient centrifugation with high yields of live cells, as previously described 23,25.

Tissue preparation for confocal imaging

Dissected LN tissues were fixed in PFA, lysine and periodate buffer (PLP, 0.05 M phosphate buffer, 0.1 M l-lysine, pH 7.4, 2 mg/mL NaIO4, and 10 mg/mL paraformaldehyde) overnight at 4°C (Supplementary Table 3). The following day, tissues were dehydrated in 30% sucrose overnight in 4°C and subsequently embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound. Donor LN IDs bearing numbers lower than 410 were fixed in PBS solution with 1% paraformaldehyde and, 0.1 M l-lysine, incubated in 20% sucrose in 4°C, and subsequently embedded in OCT compound. Frozen tissues were sectioned using Leica 3050S at 20μm thickness. Intracellular staining media was prepared with PBS containing 2% goat serum, 2% FBS, 0.05% Tween-20 and 0.3% Triton-X. Tissues were blocked with Human TruStain FcX (Biolegend, 1:100 dilution) in intracellular staining media for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were washed with the intracellular staining buffer and stained with the indicated antibodies (Supplementary Table 2) in 1:25 dilution for 1 hour at room temperature. Cytokine staining was performed with their corresponding isotypes to eliminate any signal due to non-specific binding. Images were acquired with Nikon Ti Eclipse inverted confocal microscope using the dry 20x objective. For fluorescence detection, the following lasers were used:405, 488,561 and 638nm. For imaging of whole LN sections, 70-400 20X images were acquired depending on the size of the LN, then computationally stitched by the NIS-elements software (Nikon). Single 20X images were imaged in 2μm 3X Z-steps. Images were analyzed using Imaris software (Bitplane; Oxford Instruments, version 9.5/9.6) including spot, surface, shortest distance, circularity, isosurfacing and pseudocoloring functions.

Flow cytometry

LN cells were enriched for CD3− cells using biotin-conjugated anti-CD3 and EasySep™ Human Biotin Positive Selection Kit II (Stemcell Technologies, Supplementary Table 3). Following enrichment, LN cells were resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS/5% FBS/ 0.5% sodium azide) and stained for surface markers in 1:100 dilution for 20 minutes in 4°C (Supplementary Table 2). For intracellular staining, cells were resuspended with Fix/Perm concentrate and incubated for 60mins at room temperature as indicated in the TONBO biosciences TF staining kit (CAT#TNB-0607-KIT). Cells were washed with perm buffer, resuspended in the perm buffer with antibodies in 1:100 dilution and incubated for 60mins at room temperature. Cells were then washed and resuspended in FACS buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry using the BD LSRII (Becton Dickinson), and data were analyzed in FlowJo software (Tree star, version 10.7.1). To generate the heatmap of marker expression, geometric mean fluorescent intensities for each surface marker were exported from FlowJo, normalized to the average expression of each marker across the subsets, and plotted in Python using the seaborn package.

Phagocytosis Assay

The human macrophage line THP-1 (kindly provided by Dr. Sankar Ghosh) was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 10000 I.U Penicillin (per ml) 10000 ug/ml Streptomycin 29.2 mg/ml L-glutamine (Fisher Scientific). THP-1 cells (4X104) were differentiated using (400nM) Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (Sigma) for 3 days in 6 well plates and cells were rested overnight in fresh media (RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 10000 I.U Penicillin (per ml) 10000 ug/ml Streptomycin 29.2 mg/ml L-glutamine). Atmospheric particulates purified from air filters and analyzed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)26 were purchased from Sigma. For testing uptake of particulates, differentiated THP-1 cells were incubated in fresh media with black particulates (0.0006g/ml) for 6 hours at 37°C. Following incubation, cells were washed twice to remove all the free-floating particulates and were rested overnight in fresh media. For assessing phagocytosis, differentiated THP-1 cells without particulates (Control) and with particulates were cultured in live imaging solution with pHrodo™ Red E. coli BioParticles™ according to the manufacturer’s protocol at 4°C degrees (control condition) or 37°C (experimental condition) for 90 minutes. Fresh live imaging solution was added to cells and imaged immediately using confocal microscopy.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 8.2.0 (GraphPad) except the multivariable regression analysis, which was done using Excel, version 16.54. For correlations with age, Pearson correlation was used, and Pearson R value and their associated P value are included in the figures. Statistical comparisons between two groups were done by student T-test. For assessing differences between cytokine production and Ki-67 in macrophages with and without particulates we used repeated measures 2-way Anova. To further assess the differences in cytokine production, multivariable regression analysis was used to control for particulate and age related effects. Where noted, three or more groups were analyzed by using 1-way ANOVA, 2-way ANOVA and Mixed effects with Tukey’s posttest.

Extended Data

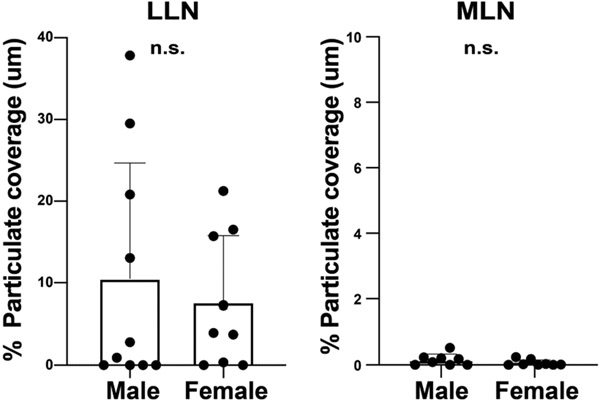

Extended Data Fig. 1. Carbon particulate content in different lymph nodes is similar between males and females.

Carbon particulate content in the lung-associated lymph node (LLN) and mesenteric lymph node (MLN) of donors from Figure 1 stratified by sex. Data from 16-19 donors per site. Significance calculated by student T-test (two-tailed). Data presented as the mean ± SEM. N.S.: not significant by student’s t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Particulate uptake occurs within CD11c+ macrophages but not dendritic cells (DC).

a. Confocal image of human LLNs stained for MHCII (HLA-DR), CD11c, and CD141 expression to identify DC (CD11c+HLA-DR+CD141+) shown with overlay of brightfield (left columns) for visualizing particulates (middle and right columns). Representative images were taken from 5 donors. Scale bar: 50 um. b. Confocal image of human LLNs stained for macrophage markers CD68 and CD169 along with CD11c. The image on the left show with overlay of brightfield (left columns) to show localization of particulates (white). The image on the right shows the CD68 and CD11c expression on macrophages. Representative images were taken from 6-9 donors per age group (≤39,40-64 and ≥65 yrs). Scale bar: 50-100 um. c. Graphs shows particulate content in specific macrophage subsets for different age groups, quantitated using Imaris software. Significance calculated by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posttest, **P < 0.0021, ***P < 0.0002, ****P < 0.0001. Significance for 40-64: CD68+CD169−CD11c+ vs. CD68+CD169+CD11c+ P=0.0144, CD68+CD169−CD11c+ vs. CD68−CD169+CD11c+ P=0.0316; 65≤: CD68+CD169−CD11c+ vs. CD68+CD169+CD11c+ P=<0.0001, CD68+CD169−CD11c+ vs. CD68−CD169+CD11c+ P=<0.0001. Data presented as the mean ± SD. Data are from 17 donors.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Gating strategy.

Flow cytometry gating for CD68+CD169−, CD68−CD169+, and CD68+CD169+ macrophage subsets following gating on live, singlet, and CD45+ cells.

Extended Data Fig. 4. CD68−CD169+ macrophages in LN do not exhibit alterations in functional marker expression with age.

a. Frequency of CD68−CD169+ macrophages in LLN (n=21) and MLN (n=19) over age. Linear regression with Pearson correlation (two-tailed). Pearson r, *P < 0.033, **P < 0.005 and ***P < 0.001. Data presented as the mean ± 95% CI. b. Expression of functional markers CD80/86, CD36, and CD209 expression on CD68−CD169+ macrophages over age by flow cytometric analysis of LLNs (n=21, left column) and MLNs (n=19, right column). Linear regression with Pearson correlation (two-tailed). Pearson r, *P < 0.033. Data presented as the mean ± 95% CI.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Particulates inhibit phagocytosis but do not alter age-associated effects on proliferation.

a. Particulate containing THP-1 macrophages cannot phagocytose fluorescent pHrodo beads. Representative images of differentiated THP-1 cells previously incubated with (+) or without (−) black particulates subsequently cultured with pHrodo beads at 37°C or 4°C for 90 minutes. Confocal image of THP-1 cells imaged for pHrodo beads and brightfield. Yellow arrows indicate THP-1 cells. Scale bar: 50um. Image is representative of two experiments. (n=9-12 wells/condition). b. Imaging data from Fig.3g analyzed for Ki67+ CD68+CD169− macrophages that are within or outside the black particulate area. Significance assessed with paired T-test (two-tailed). Data are from 13 donors (2-7 single images for each donor).

Extended Data Fig. 6. Particulate-containing CD68+CD169− macrophages induce an immunoregulatory environment in the LLNs.

a. Confocal image of human LLNs stained for CD68, CD169, and Arginase-1 from donors of indicated ages. Arrows show representative CD68+CD169− macrophages with particulates (magenta) or without particulates (orange). Representative images were taken from 2-6 donors (2-4 images/donor) per age group (≤39,40-64 and ≥65 yrs). Scale bar: 20 um. b. Graph shows paired frequencies of Arg-1+CD68+CD169− macrophages with or without particulates calculated using Imaris software. Significance assessed with repeated measures ANOVA. Significance for ≤39yrs P= 0.059, 40-64 years P=0.0088, ≥65 years P=0.9969. Data are from 13 donors (2-4 single images for each donor). c. Graph shows frequency of Arg-1+CD68+CD169− macrophages with or without particulates over age calculated using Imaris software. (n=13). Linear regression with Pearson correlation (two-tailed). Pearson r, n.s. Data presented as the mean ± 95% CI. d. Confocal image of human LLNs stained for CD68, CD169, and IL-6 from donors of indicated ages. Arrows show representative CD68+CD169− macrophages with particulates (magenta) or without particulates (orange). Representative images were taken from 4-5 donors (2-4 images/donor) per age group (≤39,40-64 and ≥65 yrs). Scale bar: 20 um. e. Graph shows paired frequencies of IL-6+CD68+CD169− macrophages with or without particulates calculated using Imaris software. Significance assessed with repeated measures ANOVA. Significance for ≤39yrs P= <0.0001, 40-64 years P=0.0037, ≥65 years P=0.0002. Data are from 14 donors (2-4 single images for each donor) f. Graph shows frequency IL-6+CD68+CD169− macrophages with or without particulates over age calculated using Imaris software. (n=14). Linear regression with Pearson correlation (two-tailed). Pearson r, n.s. Data presented as the mean ± 95% CI.

Extended Table 1.

Organ donors used in this study.

| Donor # |

Age (years) and Sex |

Donor # |

Age (years) and Sex |

Donor # |

Age (years) and Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 204 | 30 M | 300 | 56M | 433 | 86F |

| 212 | 48 | 307 | 18M | 434 | 46F |

| 217 | 49M | 308 | 68M | 435 | 55F |

| 223 | 29F | 309 | 45F | 436 | 62F |

| 231 | 56M | 314 | 35F | 439 | 62F |

| 236 | 75F | 317 | 23F | 442 | 19M |

| 239 | 93F | 319 | 11M | 444 | 34F |

| 242 | 20F | 321 | 17F | 447 | 40F |

| 245 | 50F | 322 | 32M | 451 | 54F |

| 247 | 45F | 324 | 56M | 454 | 27F |

| 250 | 39F | 329 | 43F | 455 | 70M |

| 252 | 72M | 338 | 49M | 456 | 53M |

| 253 | 23M | 340 | 23M | 459 | 52F |

| 255 | 63F | 341 | 49M | 461 | 22F |

| 256 | 70M | 342 | 59M | 462 | 76F |

| 259 | 46M | 344 | 44M | 465 | 15M |

| 262 | 73M | 345 | 73F | 467 | 58F |

| 267 | 70F | 360 | 16M | 481 | 29M |

| 270 | 23F | 410 | 78F | 482 | 66M |

| 274 | 14M | 417 | 78M | 483 | 33M |

| 275 | 31M | 420 | 34M | 484 | 59M |

| 276 | 41M | 421 | 18F | 491 | 44F |

| 279 | 73F | 422 | 60M | 494 | 51M |

| 285 | 53M | 423 | 83M | 502 | 35F |

| 286 | 46M | 424 | 71F | 504 | 39M |

| 288 | 32M | 427 | 69M | 507 | 29M |

| 290 | 77F | 428 | 61M | 509 | 70M |

| 299 | 20M | 430 | 18M | 528 | 64F |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants HL145547, AI106697, and AI128949 awarded to D.L.F. B.B.U. was supported by NIH T32HL105323; P.D. was supported by a Cancer Research Institute (CRI) Irvington Postdoctoral Fellowship; N.L, is supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (NSF-GRFP); P.S. was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Fellowship. This study also used the Confocal and Specialized Microscopy Shared resource core supported by NIH P30 CA013696 and CCTI Flow Cytometry Core supported in part by NIH S10RR027050. The authors would like to thank Matthew J. Gastinger (Imaris) for his python code used in the B cell imaging analysis, Ms. Andreacarola Urso for previous help with confocal microscopy, Dr. Sankar Ghosh for the THP-1 cell line and the transplant coordinators at LiveOnNY and donor families for making this study possible.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

Source data for this study are provided for Figures 1-6 and Extended data 1,2,4-6.

Code availability

The python code used to analyze B cell circularity is available at GitHub (https://github.com/Ironhorse1618/Python3.7-Imaris-XTensions).

References

- 1.Schneider JL, et al. The aging lung: Physiology, disease, and immunity. Cell 184, 1990–2019 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aging, N.I.o. Why Population Aging Matters. in A Global Perspective 1–28 (NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pop-Vicas A & Gravenstein S Influenza in the elderly: a mini-review. Gerontology 57, 397–404 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Driscoll M, et al. Age-specific mortality and immunity patterns of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 590, 140–145 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akbar AN & Gilroy DW Aging immunity may exacerbate COVID-19. Science 369, 256–257 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metcalf CJE, et al. Comparing the age and sex trajectories of SARS-CoV-2 morbidity and mortality with other respiratory pathogens. R Soc Open Sci 9, 211498 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Presley CJ, Reynolds CH & Langer CJ Caring for the Older Population With Advanced Lung Cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 37, 587–596 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M & Kroemer G The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153, 1194–1217 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frasca D & Blomberg BB Inflammaging decreases adaptive and innate immune responses in mice and humans. Biogerontology 17, 7–19 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams AE, Jose RJ, Brown JS & Chambers RC Enhanced inflammation in aged mice following infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae is associated with decreased IL-10 and augmented chemokine production. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 308, L539–549 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nilsson Sommar J, et al. Long-term exposure to particulate air pollution and black carbon in relation to natural and cause-specific mortality: a multicohort study in Sweden. BMJ Open 11, e046040 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisberg SP, Ural BB & Farber DL Tissue-specific immunity for a changing world. Cell 184, 1517–1529 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legge KL & Braciale TJ Lymph node dendritic cells control CD8+ T cell responses through regulated FasL expression. Immunity 23, 649–659 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paik DH & Farber DL Influenza infection fortifies local lymph nodes to promote lung-resident heterosubtypic immunity. J Exp Med 218(2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masters AR, et al. Assessment of Lymph Node Stromal Cells as an Underlying Factor in Age-Related Immune Impairment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 74, 1734–1743 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luscieti P, Hubschmid T, Cottier H, Hess MW & Sobin LH Human lymph node morphology as a function of age and site. J Clin Pathol 33, 454–461 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadamitzky C, et al. Age-dependent histoarchitectural changes in human lymph nodes: an underestimated process with clinical relevance? J Anat 216, 556–562 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buettner M & Bode U Lymph node dissection--understanding the immunological function of lymph nodes. Clin Exp Immunol 169, 205–212 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies ML, et al. A systemic macrophage response is required to contain a peripheral poxvirus infection. PLoS Pathog 13, e1006435 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farber DL Tissues, not blood, are where immune cells act. Nature 593, 506–509 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carpenter DJ, et al. Human immunology studies using organ donors: Impact of clinical variations on immune parameters in tissues and circulation. Am J Transplant 18, 74–88 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dogra P, et al. Tissue Determinants of Human NK Cell Development, Function, and Residence. Cell 180, 749–763 e713 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Granot T, et al. Dendritic Cells Display Subset and Tissue-Specific Maturation Dynamics over Human Life. Immunity 46, 504–515 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thome JJ, et al. Spatial map of human T cell compartmentalization and maintenance over decades of life. Cell 159, 814–828 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miron M, et al. Human Lymph Nodes Maintain TCF-1(hi) Memory T Cells with High Functional Potential and Clonal Diversity throughout Life. J Immunol 201, 2132–2140 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schantz MM, et al. Development of two fine particulate matter standard reference materials (<4 mum and <10 mum) for the determination of organic and inorganic constituents. Anal Bioanal Chem 408, 4257–4266 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellomo A, Gentek R, Bajenoff M & Baratin M Lymph node macrophages: Scavengers, immune sentinels and trophic effectors. Cell Immunol 330, 168–174 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray EE & Cyster JG Lymph node macrophages. J Innate Immun 4, 424–436 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies LC, Jenkins SJ, Allen JE & Taylor PR Tissue-resident macrophages. Nat Immunol 14, 986–995 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ural BB, et al. Identification of a nerve-associated, lung-resident interstitial macrophage subset with distinct localization and immunoregulatory properties. Sci Immunol 5(2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Neill AS, van den Berg TK & Mullen GE Sialoadhesin - a macrophage-restricted marker of immunoregulation and inflammation. Immunology 138, 198–207 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez-Pomares L & Gordon S CD169+ macrophages at the crossroads of antigen presentation. Trends Immunol 33, 66–70 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baratin M, et al. T Cell Zone Resident Macrophages Silently Dispose of Apoptotic Cells in the Lymph Node. Immunity 47, 349–362 e345 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tremble LF, et al. Differential association of CD68(+) and CD163(+) macrophages with macrophage enzymes, whole tumour gene expression and overall survival in advanced melanoma. Br J Cancer 123, 1553–1561 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Etzerodt A & Moestrup SK CD163 and inflammation: biological, diagnostic, and therapeutic aspects. Antioxid Redox Signal 18, 2352–2363 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Medina-Contreras O, et al. CX3CR1 regulates intestinal macrophage homeostasis, bacterial translocation, and colitogenic Th17 responses in mice. J Clin Invest 121, 4787–4795 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ensan S, et al. Self-renewing resident arterial macrophages arise from embryonic CX3CR1(+) precursors and circulating monocytes immediately after birth. Nat Immunol 17, 159–168 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erdman LK, et al. CD36 and TLR interactions in inflammation and phagocytosis: implications for malaria. J Immunol 183, 6452–6459 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulz D, Severin Y, Zanotelli VRT & Bodenmiller B In-Depth Characterization of Monocyte-Derived Macrophages using a Mass Cytometry-Based Phagocytosis Assay. Sci Rep 9, 1925 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hashimoto D, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity 38, 792–804 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cox N, Pokrovskii M, Vicario R & Geissmann F Origins, Biology, and Diseases of Tissue Macrophages. Annu Rev Immunol 39, 313–344 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sica A & Mantovani A Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest 122, 787–795 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang Q, Xu L & Ye L T cell immune response within B-cell follicles. Adv Immunol 144, 155–171 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Popescu M, Cabrera-Martinez B & Winslow GM TNF-alpha Contributes to Lymphoid Tissue Disorganization and Germinal Center B Cell Suppression during Intracellular Bacterial Infection. J Immunol 203, 2415–2424 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaneko N, et al. Loss of Bcl-6-Expressing T Follicular Helper Cells and Germinal Centers in COVID-19. Cell 183, 143–157 e113 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petrova TV & Koh GY Biological functions of lymphatic vessels. Science 369(2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schacht V, et al. T1alpha/podoplanin deficiency disrupts normal lymphatic vasculature formation and causes lymphedema. EMBO J 22, 3546–3556 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arandjelovic S & Ravichandran KS Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in homeostasis. Nat Immunol 16, 907–917 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kurosaka K, Takahashi M, Watanabe N & Kobayashi Y Silent cleanup of very early apoptotic cells by macrophages. J Immunol 171, 4672–4679 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boe DM, Boule LA & Kovacs EJ Innate immune responses in the ageing lung. Clin Exp Immunol 187, 16–25 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nikolich-Zugich J Aging of the T cell compartment in mice and humans: from no naive expectations to foggy memories. J Immunol 193, 2622–2629 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar BV, Connors TJ & Farber DL Human T Cell Development, Localization, and Function throughout Life. Immunity 48, 202–213 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poon MML, et al. Heterogeneity of human anti-viral immunity shaped by virus, tissue, age, and sex. Cell Rep 37, 110071 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen AJ, et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 389, 1907–1918 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matthews NC, et al. Urban Particulate Matter-Activated Human Dendritic Cells Induce the Expansion of Potent Inflammatory Th1, Th2, and Th17 Effector Cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 54, 250–262 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brandt EB, et al. Exposure to allergen and diesel exhaust particles potentiates secondary allergen-specific memory responses, promoting asthma susceptibility. J Allergy Clin Immunol 136, 295–303 e297 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guarnieri M & Balmes JR Outdoor air pollution and asthma. Lancet 383, 1581–1592 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haghani A, Morgan TE, Forman HJ & Finch CE Air Pollution Neurotoxicity in the Adult Brain: Emerging Concepts from Experimental Findings. J Alzheimers Dis 76, 773–797 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haghani A, Thorwald M, Morgan TE & Finch CE The APOE gene cluster responds to air pollution factors in mice with coordinated expression of genes that differs by age in humans. Alzheimers Dement 17, 175–190 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scieszka D, et al. Neuroinflammatory and Neurometabolomic Consequences From Inhaled Wildfire Smoke-Derived Particulate Matter in the Western United States. Toxicol Sci 186, 149–162 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Source data for this study are provided for Figures 1-6 and Extended data 1,2,4-6.

The python code used to analyze B cell circularity is available at GitHub (https://github.com/Ironhorse1618/Python3.7-Imaris-XTensions).