Abstract

Infectious diseases are a major concern around the world. Today, it is an urgent need for new chemotherapeutics for infectious diseases. Because of that, our group designed, synthesized, and analyzed 14 new quinoline derivatives endowed with the pharmacophore moiety of fluoroquinolones primarily for their antimicrobial effects. Their cytotoxicity effects were tested against six bacterial and four fungal strains and NIH/3T3 cell line. Additionally, their action mechanisms were evaluated against DNA gyrase and lanosterol 14α-demethylase (LMD). Furthermore, to eliminate the potential side effects, the active compounds were evaluated against the aromatase enzyme. The experimental enzymatic results were evaluated for active compounds’ binding modes using molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation studies. The results were utilized to clarify the structure–activity relationship (SAR). Finally, compound 4m was the most potent compound for its antifungal activity with low cytotoxicity against healthy cells and fewer possible side effects, while compounds 4j and 4l can be used alone for special patients who are suffering from fungal infections in addition to the primer disease.

1. Introduction

Infection is described as pathogenic microorganisms’ invasion and/or multiplying in the tissue or organ of another organism and then causing some undesirable effects in the host.1,2 There are many pathogenic microorganisms like viruses, bacteria, fungi, yeast, etc. However, the incidence of bacterial and fungal infections is quite high worldwide than others.3

Although humanity has a symbiotic relationship with nonpathogenic bacteria and fungi, this relationship can be disrupted, and at this time, invasive microorganisms that can take advantage of this situation may cause infection.4−7 They can also be contagious; various factors such as water, food, and travel play a role in the spread of these kinds of diseases.8 In recent decades, resistance development is a major issue and is classified as drug-induced and microorganism-induced resistances. Mostly, they are related to unnecessary (incorrect dose or use of drugs in unrelated indications)9 and multiple drug uses.10−12 Additionally, misdiagnosis and wrong treatment methods,13 prescriptions written only to eliminate symptoms (symptomatic treatment), or patients abandoning their treatment unfinished14 make also some difficulties in the fighting against infectious diseases. Besides that, microbial infections are frequently seen in patients whose immune system is suppressed or insufficient, such as cancer and AIDS patients. In recent studies, the reported mortality and morbidity rates of microbial resistance developed by bacteria and fungi increased the concerns,15,16 especially regarding the inefficacy of the treatment applied in hospitals.17

Today, although the antimicrobial agents are classified depending on different properties such as action mechanism, spectrum width, and chemical structure, the structure–activity relationship (SAR) comes to the fore for medicinal chemists.18 With the clinical use of nalidixic acid in 1964, scientists focused on the antimicrobial activity of quinoline derivatives.19 Quinoline derivatives also play a role in cancer treatments (topoisomerase inhibition) due to their action mechanism (DNA-gyrase inhibition).20−22 The structures of bacterial and eukaryotic topoisomerase IIs were identified, and they are highly similar to each other.23 Even though this link seems satisfying, and the result may perceive as dual activity, they should be tested against healthy human cells in the current preclinical phase.

In addition, quinolones have a good antifungal activity profile24−26 besides their antibacterial activity. Currently, the action mechanism of the drugs for the treatment of fungal diseases is generally based on blocking the ergosterol production because of their selectivity profile,27,28 and with that, they break the fungal cell integrity. The spectacular pathway for this activity is the inhibition of lanosterol 14α-demethylase (LDM).29 Indeed, each antifungal imidazole analogue has previously been studied on P450, and they have been identified as potent ligands of the heme iron atom of P450s.30 Moreover, ravuconazole and its analogues (fosravuconazole and isavuconazole) include a thiazole ring as a secondary azole, and albaconazole includes quinazolin-4-one ring, and their action mechanism is mediated through P450 enzymes.31,32 Hence, it was proven that the other azole rings [such as (benzo)-1,2,3-triazole,33,34 1,2,4-triazole,35,36 1,3,4-oxadiazole,37 and 1,3-thiazole] and non-azole nitrogen-rich rings may have also a good antifungal activity profile against invasive fungi. However, several side effects were reported,38,39 probably caused by similarity to the human aromatase (HA) enzyme,40 and also they showed some drug–drug interactions.41 Hence, the design strategy should also involve inhibiting the LDM while not inhibiting HA.

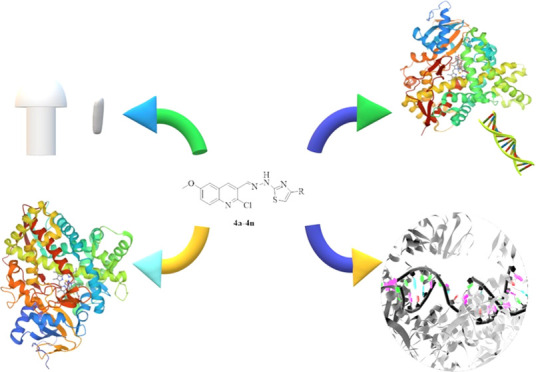

Based on the above information, we designed, synthesized, and analyzed 14 new quinoline derivatives endowed with the pharmacophore moiety of fluoroquinolones to observe the antimicrobial effect. For this purpose, the literature knowledge was used to achieve a hybridization of the pharmacophoric groups of the molecules, as seen in Figure 1. The final molecules include 6-methoxy-2-chloroquinoline as the core structure. Their derivatization was achieved at the fourth position of the thiazole ring, and both aromatic ring systems were linked to each other with the hydrazone moiety. Their structure–activity relationship (SAR) and action mechanism were clarified viain vitro and in silico studies.

Figure 1.

Designing the strategy of new quinoline derivatives as an antimicrobial agent. At the center of the figure, the target compounds are presented. Turquoise drawings schematize the analogue ring systems. Each color represents a moiety of target compounds.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

The designed compounds (see Table 1) were synthesized and analyzed. The analyzed spectra are provided in the Supporting Information (Figures S1–S42).

Table 1. Synthesized Compounds.

2.1.1. 1H NMR

Thiazole and quinoline are the common ring systems in all final compounds. In the sixth position of the quinoline, there is a methoxy and in the second position there is a chlorine substituent. Different aromatic substitutions were made at the fourth position of the thiazole ring, and the quinoline and the thiazole ring were linked by a hydrazone bridge. By investigating 1H NMR spectra, the peak due to the fourth position proton of the quinoline was observed as a singlet between 8.68 and 8.78 ppm. The peak of hydrogen in the eighth position is observed as a doublet in the range of 7.82–7.91 ppm, and it is observed as a multiplet in some spectra because it is overlapped with other peaks. The peak due to the fourth position of the quinoline proton was observed as a doublet in the range of 7.58–7.68 ppm because of the surrounding proton interactions. The peak due to the seventh position of the quinoline was observed in the 7.42–7.52 ppm range as doublets due to the surrounding proton interactions, and as multiplet, because it was partially overlapped with other peaks. The proton peak at the fifth position of the thiazole ring was observed generally as a singlet between 7.21 and 7.81 ppm, and multiplet was obtained since it was partially overlapped with other proton peaks. The two hydrogens, at the second and sixth positions of the 1,4-substituted phenyl derivatives (4a–c and 4e–g), were observed as doublets between 7.75 and 8.27 ppm, while the other two protons of the third and fifth positions were observed overlapped and as doublets between 6.97 and 8.11 ppm. Hydrogens of 3-substituted phenyl derivatives (4h–k) were obtained in the range of 6.87–8.65 ppm. According to the literature, the protons of the 4-substituted phenyl ring, 3-substituted phenyl ring, and mono-substituted phenyl ring follow the X2Y2, XYZW, and X2Y2Z spin systems, respectively. Although the cleavage patterns of the protons of the 1,4-disubstituted phenyl ring are mostly observed as two doublets (one for positions 2 and 6, one for positions 3 and 5), they can also be observed as singlet and quartet due to the properties of the substitutions.42−44 Although proton cleavages of the 1,3-disubstituted phenyl ring are generally observed as one triplet (fifth position), two doublets (fourth and sixth positions), and one singlet (second position), very different cleavages can be observed due to the substitutions.43,45

The protons of the methylidene hydrazine (−HC=N–NH−) structure, which is common in all compounds, are generally singlet in the range of 8.41–8.49 ppm and partially multiplet due to mixing with other peaks; nitrogen proton was obtained as a broad singlet between 12.56 and 12.73 ppm. In the literature, they were observed as singlet and broad singlet.43,46 When similar molecules were examined in the literature,47 it was determined experimentally that compounds with a singlet peak at about 8.50 ppm were E isomers. This finding is suggested in this direction in terms of stability due to the presence of bulky groups in the structure of the compound.

In conclusion, the 1H NMR data of all synthesized compounds were found to be consistent with the literature data.

2.1.2. 13C NMR

According to the 13C NMR data of the synthesized compounds, peaks were observed as expected. The common carbons’ peaks and the unique carbons’ peaks of the compounds were examined. Since compounds 4a and 4j contain fluorine as a substituent, the spectra of these compounds were obtained as one additional peak, as mentioned in the literature due to C–F cleavages.48 The peaks of the carbon due to methylidene hydrazine, which is a common carbon for all compounds, were obtained in the range of 143.23–143.82 ppm similar to the literature.46 Aromatic carbons peaked in the range of 102.64–168.62 ppm, and methoxy carbons were seen between 55.55 and 56.24 ppm.

2.1.3. High-Resolution Mass Spectrum

Mass spectra of the final compounds were obtained using the electrospray ionization (ESI) technique.43 When the mass spectra were examined, M + 1 peaks were detected in all compounds (4a–n).

2.2. Results of Antibacterial Tests

Interestingly, no antibacterial effect was observed in compounds other than 4g, 4m, and 4n. However, when the antibacterial activities of these three compounds, especially 4g and 4m, were compared with the antibacterial effects of ciprofloxacin and chloramphenicol, they have a good antibacterial profile. Results of the antibacterial activity are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Antibacterial Activity Results of the Final Compounds (μg/mL)a.

RF-1: chloramphenicol, RF-2: ciprofloxacin, A: Escherichia coli ATCC 35218, B: E. coli ATCC 25922, C: Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538, D: methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (clinical isolate), E: Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 13311, F: Klebsiella pneumoniae NCTC 9633. Most active compounds are highlighted in red and moderately active compounds are written in bold.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC90) of chloramphenicol, which inhibit 90% of the microbial population, were determined as 31.25 and 15.63 μg/mL against E. coli (ATCC 35218) and E. coli (ATCC 25922) strains, respectively. On the other hand, the MIC90 of ciprofloxacin was found to be lower than 1.95 μg/mL. Therefore, it was concluded that compound 4g (MIC90: 7.81; 3.91 μg/mL) was four times more effective against both E. coli strains (ATCC 35218; ATCC 25922) than chloramphenicol. Like 4g, compound 4m (MIC90: 7.81; 7.81 μg/mL) was four times more effective against E. coli (ATCC 35218) and twice as effective against E. coli (ATCC 25922). The MIC90 values of chloramphenicol against S. aureus (ATCC 6538) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (clinical isolate) strains were ≤1.95 and 31.25 μg/mL, respectively. According to these findings, compound 4g (MIC90: 3.91 μg/mL) was 8 times more effective than the standard drug against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (clinical isolate), while compound 4m (MIC90: 7.81 μg/mL) was 4 times more effective.

Compounds 4g, 4m, and 4n showed significant antibacterial activity against S. aureus (ATCC 6538) strain at 7.81, 7.81, and 62.50 μg/mL, respectively.

The synthesized compounds (4a–n) did not show antibacterial activity against S. typhimurium (ATCC 13311) and K. pneumoniae (NCTC 9633) strains.

2.3. Results of Antifungal Tests

Ketoconazole was used as the reference drug to evaluate the anticandidal activities of the final compounds. Its MIC90 values were determined as 0.24 μg/mL against Candida glabrata (ATCC 90030) and less than 0.06 μg/mL for other species. Results of the antifungal activity are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Anticandidal Activity Results of the Final Compounds (μg/mL)a.

RF: ketoconazole, A: Candida albicans ATCC 24433, B: C. glabrata ATCC 90030, C: Candida krusei ATCC 6258, D: Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019. Most active compounds are highlighted in red and moderately active compounds are written in bold.

Compounds 4d, 4i, 4k, 4l, and 4m were more effective than other derivatives against C. albicans (ATCC 24433). The MIC90 value of these five compounds was 1.95 μg/mL, and the MIC90 value of compounds 4e and 4n was determined as 3.91 μg/mL. The other analogues did not show anticandidal activity.

All compounds except 4j showed cytotoxicity against C. glabrata (ATCC 90030). Compounds 4b, 4e, and 4f showed extraordinary anticandidal activity when compared with other analogues and ketoconazole. Their MIC90 values were determined less than 0.06 μg/mL. Besides that, the MIC90 values of compounds 4a, 4d, 4i, and 4k–n were 1.95 μg/mL. The anticandidal activity against C. glabrata (ATCC 90030) was seen at 15.63 μg/mL for 4g, at 31.25 μg/mL for 4h, and 62.50 μg/mL for 4c.

The MIC90 values of 4h and 4m against C. krusei (ATCC 6258) were ≤0.06 μg/mL. However, the MIC90 values of compounds 4d, 4i, 4k, and 4n were 1.95 μg/mL, 3.91 μg/mL for 4f, 31.25 μg/mL for 4a–c and 4g; and 62.50 μg/mL for 4e and 4j. Despite the very high cytotoxicity of the 13 derivatives, compound 4l did not show cytotoxicity.

All compounds have anticandidal effects against C. parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) compared to other Candida species. In particular, compound 4j has even higher efficacy on C. parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) than the reference drug, although it did not show activity against C. albicans (ATCC 24433) and C. glabrata (ATCC 90030) cells. The MIC90 value of 4j was less than 0.06 μg/mL. In addition, compound 4m (MIC90: 0.24 μg/mL) showed significant cytotoxicity against other Candida species.

As a result, compounds 4d, 4e, 4i, 4k, 4m, and 4n showed anticandidal activity at very low concentrations against all Candida. Specifically, the chlorine (4b, 4h) substitution at the para or meta positions, the cyano group (4e) at the para position, the methyl group (4f) at the meta position, the flour atom (4j) at the meta position of the phenyl ring, or naphthalene-1-yl (4m) substitution were marked as remarkable derivatives.

Antifungal activity against C. albicans (ATCC 24433) did not increase, even more, and disappeared in the presence of substitution on the phenyl ring. The anticandidal activity was preserved when pyridine or naphthalene was substituted instead of the phenyl derivatives.

When phenyl was substituted at the meta position, anticandidal activity against C. glabrata (ATCC 90030) was preserved or disappeared. Furthermore, the substitutions of 4-Cl, 4-CN, or 4-CH3 phenyl increased the activity tremendously. In both the third and fourth position substitutions, the electron-donating groups showed higher activity than the electron-withdrawing groups. It was observed that the activity was preserved in the replacement of phenyl with other rings. Compounds showing selectivity for this species were identified as 4b, 4e, and 4f.

The effect of para substitution of the phenyl on the antifungal activity against C. krusei (ATCC 6258) resulted in decreased efficacy. In addition, the electron-donating groups showed higher activity than the electron-withdrawing groups similar to anti-C. glabrata. The activity vanished by replacing the phenyl with a pyridine, and in contrast, replacing the phenyl with a naphthalene-1-yl caused the activity to increase significantly. Furthermore, using naphthalene-2-yl instead of phenyl resulted in the activity being preserved. This strain was found to be sensitive to compounds 4h and 4m.

In the analysis of the anticandidal activity against C. parapsilosis (ATCC 22019), the presence of an electron-donating group at the para position of the phenyl ring was observed to increase the activity 4 times compared to the meta position substitutions. However, 3- or 4-chloro substitution on the phenyl reduces the activity. If the group or atom could make a hydrogen bond and it is at the third position of the phenyl, then it could increase the activity 8-fold; otherwise, the activity decreases 8-fold. Otherwise, if the substitutions could form the hydrogen bond, then the activity of these substitutions could be 64 times more than other substitutions. Besides that, replacing the phenyl ring with a pyridine and naphthalene-2-yl moieties or with naphthalene-1-yl moiety increased the activity 8 times or 64 times, respectively. Compound 4j was identified as a selective molecule for this species.

When the results were evaluated for all fungi species, it was determined that there was no difference between the electron-donating or -withdrawing substituents. Moreover, compounds (4i and 4k) having 3-NO2 and 3-OCH3 groups showed similar anticandidal activity at the same concentrations against all fungi species. Naphthalen-1-yl substitution (4m) was determined as the most active compound against all fungal cells.

2.4. Results of Cytotoxic Effects on NIH/3T3 Cell Line

The cytotoxicity effect of the compounds was tested against NIH/3T3 healthy cell line and determined as IC50 (μM) (displayed in Table 4).

Table 4. IC50 (μM) of the Compounds against NIH/3T3 Cells.

| compound | IC50 ± STD | compound | IC50 ± STD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | 39.83 ± 1.45 | 4h | 14.48 ± 0.57 |

| 4b | 14.72 ± 0.34 | 4i | 8.54 ± 0.26 |

| 4c | 31.60 ± 0.87 | 4j | 10.00 ± 0.39 |

| 4d | 1.26 ± 0.033 | 4k | 12.04 ± 0.44 |

| 4e | >1000 | 4l | >1000 |

| 4f | >1000 | 4m | 34.51 ± 0.88 |

| 4g | 10.40 ± 0.22 | 4n | >1000 |

The results can be sorted from the most cytotoxic to the less cytotoxic compounds as 4d > 4i > 4j > 4g > 4k > 4h > 4b > 4c > 4m > 4e = 4f = 4l = 4n against the NIH/3T3 healthy cell line. In fact, except for compound 4d, it can be suggested that all compounds were found safe considering that their MIC90/IC50 ratio is less than 1. Moreover, IC50 values of compounds 4e, 4f, 4l, and 4n were higher than 1000 μM.

2.5. Results of Enzyme Inhibition Tests

2.5.1. DNA-Gyrase Enzyme Inhibition

The inhibition activity on the DNA-gyrase enzyme was performed via an electrophoretic method for ciprofloxacin, compounds 4g and 4m. The obtained results are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Inhibition visualities of compounds 4g and 4m and ciprofloxacin against E. coli DNA gyrase by electrophoresis. (A) Relax (pHOT1) DNA image: no chemicals and DNA gyrase; (B) supercoiled DNA image: relaxed (pHOT1) DNA with gyrase, no chemicals; (C) compound 4g: relax (pHOT1) DNA, gyrase, and chemical dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO); (D) compound 4m: relax (pHOT1) has DNA, gyrase, and chemical dissolved in DMSO, (E) positive control: there is relax (pHOT1) DNA, gyrase, and ciprofloxacin dissolved in DMSO; and (F) negative control: there is relax (pHOT1) DNA, gyrase, and DMSO only.

In the figure, the reference drug and the synthesized compounds have very similar appearances, and there was no peak belonging to the supercoiled DNA. Thus, it can be concluded that the antibacterial effect of compounds 4g and 4m was caused by the inhibition of the DNA-gyrase enzyme.

2.5.2. Lanosterol 14α-Demethylase (LMD, CYP51A1) Inhibition Tests

The activity of the target compounds was tested against Candida strains via the determination of ergosterol production. The results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. CYP51A1 Inhibition% Results of the Final Compounds (μg/mL).

|

C. glabrata |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| concentrations (μg/mL) | ||||

| compounds | 3.91 | 0.98 | 0.24 | 0.06 |

| 4b | 70.345 ± 2.638 | 60.197 ± 2.095 | 51.754 ± 1.612 | 36.198 ± 0.965 |

| 4e | 25.398 ± 0.832 | 21.721 ± 0.955 | 18.289 ± 0.785 | 16.680 ± 0.774 |

| 4f | 79.524 ± 2.141 | 65.073 ± 1.676 | 53.774 ± 2.390 | 42.132 ± 1.561 |

| ketoconazole | 89.368 ± 3.236 | 72.768 ± 2.868 | 61.856 ± 1.833 | 50.422 ± 1.162 |

| fluconazole | 86.512 ± 2.752 | 70.144 ± 2.052 | 63.679 ± 2.185 | 46.267 ± 0.936 |

|

C. krusei |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| concentrations (μg/mL) | ||||

| compounds | 3.91 | 0.98 | 0.24 | 0.06 |

| 4h | 82.223 ± 2.575 | 67.651 ± 1.736 | 60.184 ± 1.985 | 45.530 ± 0.961 |

| 4i | 20.021 ± 0.848 | 18.361 ± 0.767 | 14.178 ± 0.655 | 11.662 ± 0.479 |

| 4m | 85.408 ± 3.502 | 70.574 ± 2.648 | 61.289 ± 1.461 | 48.431 ± 2.036 |

| ketoconazole | 87.657 ± 3.436 | 75.647 ± 2.749 | 60.630 ± 2.875 | 52.865 ± 1.662 |

| fluconazole | 85.168 ± 3.055 | 72.523 ± 1.961 | 60.132 ± 2.042 | 43.378 ± 0.937 |

|

C. parapsilosis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| concentrations (μg/mL) | ||||

| compounds | 3.91 | 0.98 | 0.24 | 0.06 |

| 4j | 75.164 ± 2.828 | 63.508 ± 1.948 | 55.281 ± 1.174 | 41.867 ± 0.968 |

| 4k | 23.518 ± 1.051 | 17.437 ± 0.861 | 15.662 ± 0.616 | 11.449 ± 0.518 |

| 4l | 78.667 ± 2.237 | 62.949 ± 2.626 | 56.137 ± 0.928 | 40.328 ± 1.326 |

| ketoconazole | 88.245 ± 2.662 | 71.864 ± 2.229 | 63.419 ± 2.074 | 55.348 ± 1.091 |

| fluconazole | 87.786 ± 3.147 | 73.204 ± 2.031 | 61.533 ± 1.282 | 49.579 ± 1.733 |

The test results showed that the activation mechanism of some active compounds (4b, 4f, 4h, 4j, 4l, and 4m) was achieved via blocking ergosterol production, which eventually ruins the cell integrity. The fact that compounds 4e, 4i, and 4k did not decrease the ergosterol production compared to the standard drugs led to the conclusion that their antifungal activity does not occur via inhibition of the LMD enzyme. As a result, we determined that even though all compounds did not show their antifungal activity via LMD enzyme inhibition, the active compounds (4b, 4f, 4h, 4j, 4l, and 4m) showed their anticandidal activity via LMD enzyme inhibition. For the next study, we aimed the determination of the antifungal mechanism of compounds 4e, 4i, and 4k.

2.5.3. Human Aromatase (HA) Inhibition

It was mentioned in the Introduction section that antifungal agents acting via a mechanism that involves the LDM pathway can cause some side effects. Thus, we aim to eliminate those possible side effects, so we also tested the antifungal active compounds on HA. The results are shared in Table 6. (Only compounds with inhibiting HA enzyme IC50 values were shared among antifungal active compounds.)

Table 6. Aromatase IC50 Results of the Final Compounds (μM).

| compound | compound | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4i | 0.033 ± 0.001 | 4k | 0.038 ± 0.001 |

| 4j | 0.047 ± 0.001 | 4l | 0.042 ± 0.002 |

| letrozole | 0.026 ± 0.001 |

The IC50 values of the active compounds 4i, 4j, 4k, and 4l were 0.038, 0.042, 0.047, and 0.033 μM against aromatase enzyme, respectively. The IC50 values of these compounds were found very close to the standard drug (letrozole, 0.026 μM). The remaining active antifungal compounds did not show aromatase inhibition activity.

2.6. Results of In Silico Studies

2.6.1. Results of ADME Parameters and Lipinski’s Rule of Five

The evaluation of some properties of the compounds and whether they violate Lipinski’s rule of five are given in Table 7. This rule does not determine whether the compounds are pharmacologically active but indicates that compounds that comply with the rule are less likely to be eliminated during clinical trials and thus have a better chance of reaching the market.

Table 7. Physicochemical, Pharmacokinetic, and Pharmaceutical Chemistry Properties of the Synthesized Compoundsa.

| PP |

pharmacokinetic

properties |

PC |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBA | HBD | TPSA | Log P | Log S | MBE | Log Kp | LK | SK | |

| 4a | 5 | 1 | 87.64 | 4.97 | –7.48 | high | –4.65 | 3.17 | |

| 4b | 4 | 1 | 87.64 | 5.19 | –8.02 | high | –4.38 | 3.18 | |

| 4c | 6 | 1 | 133.46 | 3.91 | –8.15 | low | –5.01 | 3.25 | |

| 4d | 4 | 1 | 87.64 | 4.65 | –7.38 | high | –4.61 | 3.16 | |

| 4e | 5 | 1 | 111.43 | 4.44 | –7.58 | high | –4.97 | 3.26 | |

| 4f | 4 | 1 | 87.64 | 4.99 | –7.75 | high | –4.44 | 3.28 | |

| 4g | 5 | 1 | 96.87 | 4.65 | –7.54 | high | –4.82 | 3.31 | |

| 4h | 4 | 1 | 87.64 | 5.19 | –8.02 | high | –4.38 | 3.17 | |

| 4i | 6 | 1 | 133.46 | 3.98 | –8.15 | low | –5.01 | 3.31 | |

| 4j | 5 | 1 | 87.64 | 4.98 | –7.48 | high | –4.65 | 3.17 | |

| 4k | 5 | 1 | 96.87 | 4.66 | –7.54 | high | –4.82 | 3.34 | |

| 4l | 5 | 1 | 100.53 | 3.92 | –6.54 | high | –5.38 | 3.11 | |

| 4m | 4 | 1 | 87.64 | 5.54 | –8.68 | low | –4.03 | 3.38 | |

| 4n | 4 | 1 | 87.64 | 5.55 | –8.68 | low | –4.03 | 3.38 | |

| RD1 | 5 | 2 | 74.57 | 1.10 | 0.00 | high | –9.09 | 2.51 | |

| RD2 | 5 | 0 | 69.06 | 3.55 | –5.51 | high | –6.46 | +(1) | 4.45 |

PP: physicochemical properties, HBA: number of hydrogen bond acceptor, HBD: number of hydrogen bond donor, TPSA: topological polar surface area (Å2), Log P: partition coefficient, Log S: solubility coefficient in water, MBE: absorption level by the gastrointestinal system, Log Kp: skin absorption coefficient (cm/sn), PC: pharmaceutical chemistry; LK: violation number of rule of five, SK: synthesis ease score in terms of medicinal chemistry (1: very easy, 10: very hard, r2: 0.94), RD1: reference drug-1 (ciprofloxacin), RF2: reference drug-2 (ketoconazole).

According to the results, the compounds are predicted to be suitable for oral use since the final molecules do not violate Lipinski’s RoF. However, it was calculated that molecules carrying NO2 phenyl or naphthalene moieties may have low absorption from the gastrointestinal tract. When the rates of compounds passing through the horny layer, known as the rate-limiting step, are evaluated for topical drug applications,49 it is predicted that all compounds are suitable for that. The synthesis feasibility of the target compounds in terms of medicinal chemistry was determined as easy compared to that of ketoconazole and difficult compared to that of ciprofloxacin. In conclusion, the prediction results of the compounds suggest that they can be used for both oral and topical uses.

2.6.2. Binding Modes on DNA-Gyrase Enzyme and SAR

The best docking poses and their interaction indices are shared in Figure 3 and Table 8.

Figure 3.

Docking poses of the antibacterial active compounds in the active side of DNA gyrase (PDB ID: 2XCT). 2D and 3D poses of the compounds are viewed. (A) Compound 4g and (B) compound 4m. Nucleotides are represented by the residue-type color. For clarity, only interacted residues are viewed.

Table 8. Interaction Index for the Active Compounds—DNA-Gyrase Enzyme Complex.

| compound | ligand moiety | residue | interaction type, count |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4g | oxygen of quinoline methoxy | chain B: Arg458 | 1 H-bond |

| N2 of hydrazone | Ser1085 | 1 H-bond | |

| chlorine of quinoline | chain D: Arg1122 | 1 halogen bond | |

| thiazole ring | chain E: DG6 | 1 π–π stacking | |

| thiazole ring | DG7 | 1 π–π stacking | |

| N of quinoline ring | chain G: DG9 | 1 H-bond | |

| chlorine of quinoline | DG9 | 1 halogen bond | |

| quinoline ring | DG9 | 4 π–π stackings | |

| N1 of hydrazone | Mn2000 | 1 metal chelate | |

| N of thiazole | Mn2000 | 1 metal chelate | |

| 4m | chlorine of quinoline | chain B: Lys417 | 1 halogen bond |

| N1 of hydrazone | Asp437 | 1 H-bond | |

| quinoline ring | Arg458 | 2 π–cation interactions | |

| naphthalene ring | chain G: DG9 | 3 π–π stackings | |

| naphthalene ring | chain H: DA13 | 2 π–π stackings |

According to the literature,50 the interactions with Arg458 and Asp437 amino acids have an important impact on the inhibition activity of DNA gyrase since those connections can stabilize both the DNA and gyrase enzyme; thus, the complex will not go under the supercoiled state. On the other hand, a divalent metal atom (Mg2+) is also important for DNA-gyrase activation since it is believed to be necessary to both cleave and re-ligate the DNA. In this study, both compounds interacted with Arg458, but only compound 4m formed a H-bond with the Asp437 residue, and only compound 4g was chelated with G:Mg2000. Therewithal, both compounds made hydrophobic interactions with different nucleotides (G:DG6, DG7, DG9, and H:DA13), but a common one was the DG9 nucleotide. Moreover, compound 4g formed a H-bond with this nucleotide. All of these differences are probably caused by the hydrophobic part of the substituents. Because the naphthalene ring (4m) can interact with nucleotides via π–π stacking, it can most likely be easily localized. Besides that, the 4-methoxyphenyl moiety (4g) was under solvent exposition. In conclusion, both compounds showed interest in the DNA-gyrase complex differently, but they occupied the same pocket of the complex to bind. And these interactions are in harmony with the in vitro results.

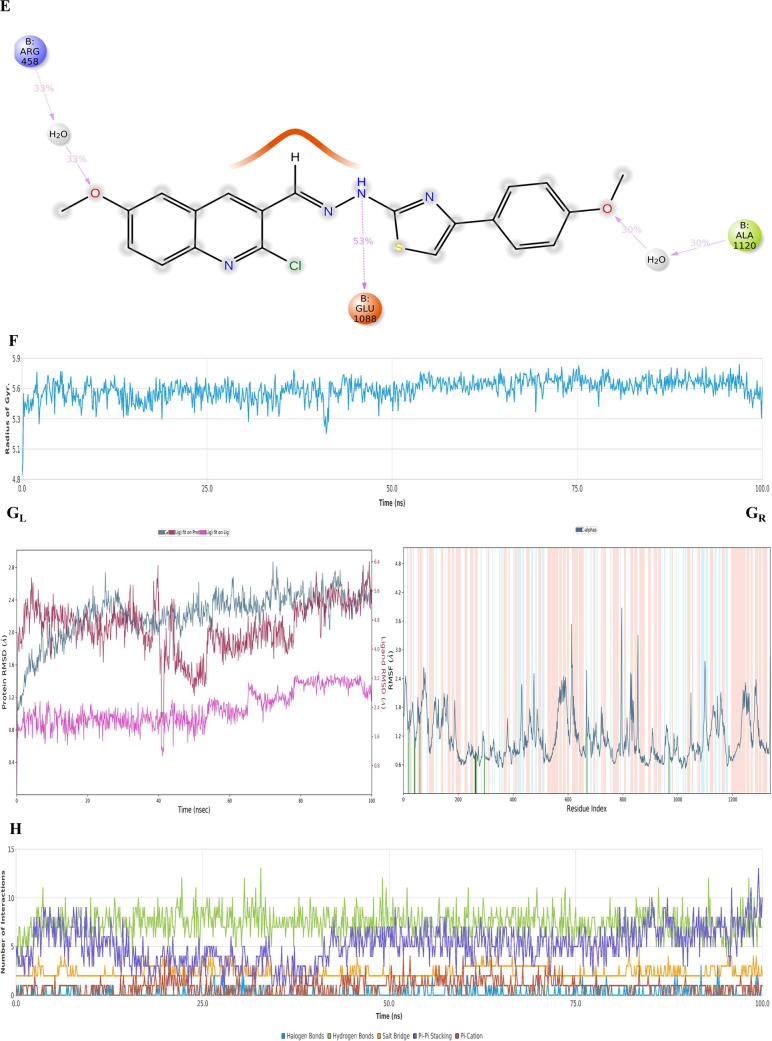

To understand the effects of environmental changes and clarify SAR more specifically, the molecular dynamics simulations (MDS) study was performed for both compounds (4g and 4m). The results are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Plots of the MDS results for 4g– and 4m–DNA–DNA-gyrase complexes. The stability properties (Rg, root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), and root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) plots, respectively) are shown in (A), (B), (F), and (G) sections. The interaction properties ((C, H) number of interactions–interaction types–time plot; (DR, IR) interaction fraction–residue diagram; (DL, IL) total connections–residues–time plot; (E, J) 2D interaction pose with connection strength (cutoff = 0.2) at the active region) are in (C)–(E) and (H)–(J) sections, respectively.

For both complexes, the stability of the systems was preserved, as shown in Figure 4A,B,F,G. The primer influential residue for the stabilization was determined as Glu1088. However, compounds 4g and 4m displayed different localizations, similar to docking studies, and thus their interacted parts with Glu1088 differed, as shown in Figure 4C–E,H–J. The hydrazone moiety of compound 4g directly interacted with Glu1088, while both the hydrazone moiety and thiazole nitrogen of compound 4m interacted via metal-chelating with the same residue. The bond strength of compound 4m was greater than that of 4g’s. On the other hand, compound 4m also interacted with Arg1122 via water-mediated H-bond even if it was just a pinch, but it did not show sufficient affinity to Arg458 or other amino acids as found in the docking study; hence, it suggests that its inhibition activity was rooted in metal-chelating. On the contrary, compound 4g formed two water-mediated H-bonds with Arg458 and Ala1120, yet all of its interactions were not found to be stable at the end of the simulation. Besides that, since the interactions with DNA nucleotides are not generated as the plot by the program, those interactions can be viewed in Video 1_4g and Video 1_4m. As seen, both compounds have interacted with DT:8, DG:9, DC:12, and DA:13 nucleotides via π–π stackings. Especially, compound 4g stacked to DG:9 nucleotide; therefore, we suggest that its activity was based on this connection. So, as a result, those compounds were in good relationship with the DNA; hence, it was concluded that they poisoned the DNA nucleotides to show their function in the same way as fluoroquinolone drugs.

2.6.3. Binding Modes on Lanosterol 14α-Demethylase Enzyme and SAR

The best docking poses and their interaction indices are shared in Figure 5 and Table 9.

Figure 5.

Docking poses of the antifungal active compounds in the active side of the LDM enzyme (PDB ID: 5TZ1). 2D and 3D poses of the compounds were viewed. (A) Compound 4b; (B) compound 4f; (C): compound (4h); (D) compound 4j; (E) compound 4l; (F) compound 4m; (G) compound 4e; (H) compound 4i; and (I) compound 4k. (S-1) 3D superimposed of the active compounds against the CYP51A1 enzyme; (S-2) 3D superimposed of the inactive compounds against the CYP51A1 enzyme.

Table 9. Interaction Index for the Active Compounds—Lanosterol 14α-Demethylase Enzyme Complex.

| compound | ligand moiety | residue | interaction type, count |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4b | thiazole ring | Tyr118 | 1 π–π stacking |

| H7 of the quinoline ring | Gly303 | 1 ar H-bond | |

| H2 of the phenyl ring | Ser378 | 1 ar H-bond | |

| quinoline ring | HEM601 | 2 π–π stackings | |

| 4f | thiazole ring | Tyr118 | 1 π–π stacking |

| N1 of hydrazone | Tyr132 | 1 H-bond | |

| H3 of the phenyl ring | Ser378 | 1 ar H-bond | |

| quinoline ring | HEM601 | 2 π–π stackings | |

| 4h | thiazole ring | Tyr118 | 1 π–π stacking |

| N1 of hydrazone | Tyr132 | 1 H-bond | |

| Cl of the phenyl ring | Ser378 | 1 halogen bond | |

| quinoline ring | HEM601 | 2 π–π stackings | |

| 4j | thiazole ring | Tyr118 | 1 π–π stacking |

| N1 of hydrazone | Tyr132 | 1 H-bond | |

| H2 of the phenyl ring | Ser378 | 1 ar H-bond | |

| quinoline ring | HEM601 | 2 π–π stackings | |

| 4l | thiazole ring | Tyr118 | 1 π–π stacking |

| N1 of hydrazone | Tyr132 | 1 H-bond | |

| H3 of the phenyl ring | Ser378 | 1 ar H-bond | |

| quinoline ring | HEM601 | 2 π–π stackings | |

| 4m | thiazole ring | Tyr118 | 1 π–π stackings |

| H2 of the naphthalene ring | Tyr118 | 1 ar-H-bond | |

| N1 of hydrazone | Tyr132 | 1 H-bond | |

| Naphthalene ring | Phe233 | 2 π–π stackings | |

| H7 of the quinoline ring | Gly303 | 1 ar H-bond | |

| H7 of the naphthalene ring | Met508 | 1 ar H-bond | |

| quinoline ring | HEM601 | 3 π–π stackings | |

| 4e | phenyl ring | Tyr64 | 1 π–π stacking |

| phenyl ring | His377 | 1 π–π stacking | |

| thiazole ring | His377 | 1 π–π stacking | |

| H2 of the phenyl ring | Ty505 | 1 ar H-bond | |

| H5 of the thiazole ring | Ser507 | 1 ar H-bond | |

| 4i | phenyl ring | His377 | 1 1 π–π stacking |

| thiazole ring | His377 | 1 π–π stacking | |

| H5 of the thiazole ring | Ser507 | 1 ar H-bond | |

| 4k | phenyl ring | His377 | 1 1 π–π stacking |

| thiazole ring | His377 | 1 π–π stacking | |

| N1 of hydrazone | Ser378 | 1 ar H-bond | |

| H5 of the thiazole ring | Ser507 | 1 ar H-bond |

Tyr118 residue and HEM protein, according to the literature,51 play critical roles in inhibition activity. Additionally, Tyr132, Gly303, and Ser378 amino acids are defined as ligand-contacting residues and they have an additional role for different fungal species. Moreover, Met508 is identified as a substrate-binding region like Tyr118 and Tyr132, but it is not responsible for supporting HEM protein. That is why it is suggested that among the other active pocket amino residues, Tyr118 and HEM are essential for the activity, but alone their interaction with β4 hairpin amino acids (like Ser507 and Met508) is not sufficient to inhibit the enzyme activity. However, the interaction with the β4 hairpin region may increase the activity.52

In this study, the results revealed that the active compounds against CYP51A have two common interactions. One was found between the thiazole ring and Tyr118 amino acid, and the other was found between the quinoline ring and HEM601, both of which were π–π stackings. Additionally, the hydrazone moiety of the active compounds formed one H-bond with Tyr132 residue, except 4b; nonetheless, compound 4b has two aromatic H-bonds in addition to two common interactions with Gly303 and Ser378 amino acids. As mentioned above, all interactions support the results of antifungal tests and enzyme activities.

Besides, compounds 4e, 4i, and 4k could not sit in the active pocket due to their substitutions. Therefore, their action mechanism should go on another pathway. All three have the capability to form a H-bond. Also, docking results point out that they were under solvent exposure; in other words, maybe some of their physicochemical properties such as TPSA and lipophilicity are not proper to the CYP51A enzyme.

In conclusion, the hybridization of the quinoline, hydrazone, and 4-arylthiazole moieties is significantly effective on this enzyme, which explains how they interacted. Also, 2-chloro-6-methoxyquinolin ring was marked as a pharmacophore group since it contacted the HEM protein.

For further understanding of the SAR, MDS analysis was performed using the best pose of the 4m–LDS enzyme complex, and this complex was used as a pattern for other active analogues. The results are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Plots of the MDS results for compound 4m–LDM enzyme complex. The stability properties (Rg, RMSD, and RMSF plots, respectively) are in (A) and (B) sections. The interaction properties ((C) number of interactions–interaction types–time plot; (DR) interaction fraction–residue diagram; (DL) total connections–residues–time plot; and (E) 2D interaction pose with connection strength (cutoff = 0.2) at the active region) are in (C)–(E) sections.

As seen in Figure 6A,B, the complex was stable during the entire simulation. The firm interactions were observed between the ligand and Tyr118 (helix B′), Phe228 (helix F″), and Met508 (β4 hairpin) residues. Chelating with the iron of the HEME protein starts approximately 10 ns after the interaction with Phe228 amino acid, and at the same time, the interaction with Phe380 is over. The RMSD plot and Video 2 clearly show that compound 4m has undergone a conformational change. As with the molecular docking result, the interactions between Tyr118 and HEM protein (and also its iron) were confirmed by the MDS study for the importance of its inhibition activity. Aromatic substitution (in this case, a 4-naphthalenylthiazole ring was used to exemplify their analogues) interacted with Phe228. This residue is a part of the substrate access channel,52 and our study showed that this access point was blocked by the naphthalene moiety of the ligand. Therefore, we foresee that the bulky, aromatic groups may increase inhibition activity via occluding the access channel. Although our docking results did not show this interaction with any active compounds, this interaction was confirmed in MDS results for compound 4m. It will probably result in similar interaction between the phenyl ring and Phe228 for the other active compounds.

In conclusion, the 2-chloro-6-methoxyquinoline ring and its thiazole derivatives whose structural importance was explained in in silico studies have great potential against the LMD enzyme. For further studies, these moieties will be reconsidered and optimized according to the above information.

2.6.4. Aromatase Enzyme Binding Modes and SAR

The best docking poses and their interaction indices are shared in Figure 7 and Table 10.

Figure 7.

Docking poses of the active compounds in the active side of the aromatase enzyme (PDB ID: 3EQM). 2D and 3D poses of the compounds were viewed. (A) Compound 4i, (B) compound 4j, (C) compound 4k, and (D) compound 4l.

Table 10. Interaction Index for the Active Compounds—Aromatase Enzyme Complex.

| compound | ligand moiety | residue | interaction type, count |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4i | NO2 group of the phenyl ring | Ar192 | 1 salt bridge |

| phenyl ring | Arg192 | 1 π–cation interaction | |

| NO2 group of the phenyl ring | Gln218 | 1 H-bond | |

| phenyl ring | Phe221 | 1 π–π stacking | |

| N1H of hydrazone | Phe221 | 1 Ar H-bond | |

| NO2 group of the phenyl ring | Asp222 | 1 salt bridge | |

| C5H of the phenyl ring | Asp309 | 1 Ar H-bond | |

| methoxy group of the quinoline ring | Met374 | 1 H-bond | |

| phenyl ring | His480 | 1 π–π stacking | |

| NO2 group of the phenyl ring | His480 | 1 Ar H-bond | |

| quinoline ring | HEM600 | 5 π–π stackings | |

| 4j | quinoline ring | Ar115 | 1 π–cation interaction |

| phenyl ring | Trp224 | 1 π–π stacking | |

| N1 of hydrazone | Met374 | 1 H-bond | |

| quinoline ring | HEM600 | 4 π–π stackings | |

| 4k | phenyl ring | Arg192 | 1 π–cation interaction |

| phenyl ring | Phe221 | 1 π–π stacking | |

| NH of the thiazole ring | Asp309 | 1 H-bond | |

| C5H of the phenyl ring | Asp309 | 1 Ar H-bond | |

| methoxy group of the quinoline ring | Met374 | 1 H-bond | |

| phenyl ring | His480 | 1 π–π stacking | |

| NO2 group of the phenyl ring | His480 | 1 Ar H-bond | |

| quinoline ring | HEM600 | 4 π–π stackings | |

| 4l | pyridine ring | Trp224 | 1 π–π stacking |

| C5H of the pyridine ring | Asp309 | 1 Ar H-bond | |

| N1H of hydrazone | Leu372 | 1 H-bond | |

| C2H of the pyridine ring | Ser478 | 1 Ar H-bond | |

| quinoline ring | HEM600 | 3 π–π stackings |

According to the works of the literature,53,54 the substrate is held above the HEME protein by the 3′-flanking loop region (Pro368–Met374), the I helix (between Glu302 and Thr310), the B′–C loop (containing Ile133 and Phe134), and the four sheets (containing Ser478 and His480). Therefore, in addition to interactions with the HEM protein, interactions with these amino acids are also important to show the ligands’ inhibition activity. Also, Met374, Asp309, and Thr310 amino acids were identified as the most important residues in the active regions. Our docking study showed that all active compounds (4i–l) interacted with HEM600 (π–π stackings). Compounds 4j and 4l have also interacted with Trp224 as common residues. Besides, only compound 4j interacted with Arg115, and only compound 4l formed a H-bond with Leu372. Moreover, only compound 4l did not form a H-bond with Met374 amino acid, but instead of that, compound 4l interacted with Leu372, which is a member of the same β-strand region. The most active compounds 4i and 4k were fit at the aromatase enzyme active region very similarly. Both interacted with Ar192, Phe221, Asp309, Met374, His480, and HEM600. The differences between them are the interaction numbers of the above residues and interactions with Gln218 and Asp222. Only compound 4i forms H-bonds with these residues, so its inhibitory effect may be increased because of that. As a result, in vitro results are supported by the docking results, and the in silico study gave a first sight of the structure–activity relationship at the molecular level.

For further understanding of the SAR, MDS analysis was performed using the best pose of the 4i–aromatase enzyme complex, and this complex was used as a pattern for other active analogues. The results are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Plots of the MDS results for compound 4i–aromatase enzyme complex. The stability properties (Rg, RMSD, and RMSF plots, respectively) are in (A) and (B) sections. The interaction properties ((C) number of interactions–interaction types–time plot; (DR) interaction fraction–residue diagram; (DL) total connections–residues–time plot; and (E) 2D interaction pose with connection strength (cutoff = 0.2) at the active region) are in (C)–(E) sections.

Figure 8A,B points out that the stability of the complex was protected during the simulation. According to the inhibition mechanism of the aromatase enzyme, the effect of ligands has been related to either stabilization of the loop amino acids or stabilization of other regional amino acids on the active site of the enzyme that interacted with loop amino acids. Therefore, stability is mainly related to the stabilization of the loop regions. In this case (see Figure 8C–E and Video 3), it can be suggested that Arg309 (I helices), Met374 (3′-flanking loop), and His480 (β4 sheet) residues have a pivotal role considering their bond strength and their interaction continuity. Therefore, enzyme substrates cannot achieve the active region for aromatization to be ergosterol. Furthermore, the chlorine of compound 4i’s quinoline ring chelated with the iron of the HEM protein, which is critical for the inhibition activity of the aromatase enzyme. In conclusion, the 2-chloro-6-methoxyquinoline ring was declared as the pharmacophore structure for aromatase inhibition, and its mechanism was explained.

3. SAR Summary

The compounds were designed and synthesized for a good antimicrobial activity profile with fewer side effects. Even though the primary aim was to find antibacterial activity with less toxicity against healthy cells, we found that their antifungal activity was more distinctive. Thus, our study was shaped by the antifungal activity after this step. For this, the active compounds were tested for their inhibition effect against LDM, and the possible side effects of the compounds were determined via testing the active compounds against the aromatase enzyme in addition to their cytotoxicity profile on healthy cells. After elimination by various tests, only compounds 4b, 4f, 4h, and 4m have passed the tests as antifungal agents. We suggest that these compounds can be used as antifungal agents after the completion of all testing studies. Moreover, mechanistic studies showed that the core structure of 2-chloro-6-methoxyquinoline and thiazole hybridization has great antifungal potential with fewer side effect profiles unless the substitutions are not in the third position on the phenyl ring or heteroaromatics. The bulky groups (such as 1-naphthalene) also affected the activity positively. On the other hand, all of these unfavorable groups increased the inhibitory activity of the aromatase enzyme. Thus, mentioned as unfavorable, third substitutions can be used in special cases who are suffering from fungal infections in addition to primer diseases such as cancer and transplant patients, but it is not the aim of this study. Hence, those purposes should be evaluated for further study.

4. Conclusions

A new series of quinoline derivatives were designed, synthesized, and analyzed. The final molecules were evaluated for their antimicrobial properties and then clarified their action mechanisms using various in vitro and in silico methods. Their antimicrobial activity was tested against six bacteria and four Candida species. Their cytotoxicity effects were determined against NIH/3T3 cell lines, and their action mechanisms were investigated on DNA gyrase, LDM, and aromatase enzyme. All of these results were inspected at the molecular level by docking and dynamic simulation studies and clarified their action mechanisms. Compounds 4b, 4f, 4h, and 4m have a good antifungal profile with low side effects, while compounds 4j and 4l can be used alone for special patients suffering from fungal infection in addition to primer disease considering their possible side effects. At least the drug interactions can be minimalized for these patients. Generally, it was announced that compound 4m has potential antimicrobial, especially, anticandidal activity, with a trustable therapeutic index and potentially fewer side effects.

5. Experimental Section

5.1. Chemistry

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO) and Merck Chemicals (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). All melting points (m.p.) were determined by an MP90 digital melting point apparatus (Mettler Toledo, Ohio) and were uncorrected. All reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using Silica Gel 60 F254 TLC plates (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Spectroscopic data were recorded with the following instruments: 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) Bruker DPX-300 FT NMR spectrometer, 13C NMR, Bruker DPX 75 MHz spectrometer (Bruker Bioscience, Billerica, MA); mass (high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS)) spectra were recorded on a liquid chromatography connected with hybrid ion-trap and time-of-flight mass spectrometry (Shimadzu) using electrospray ionization.

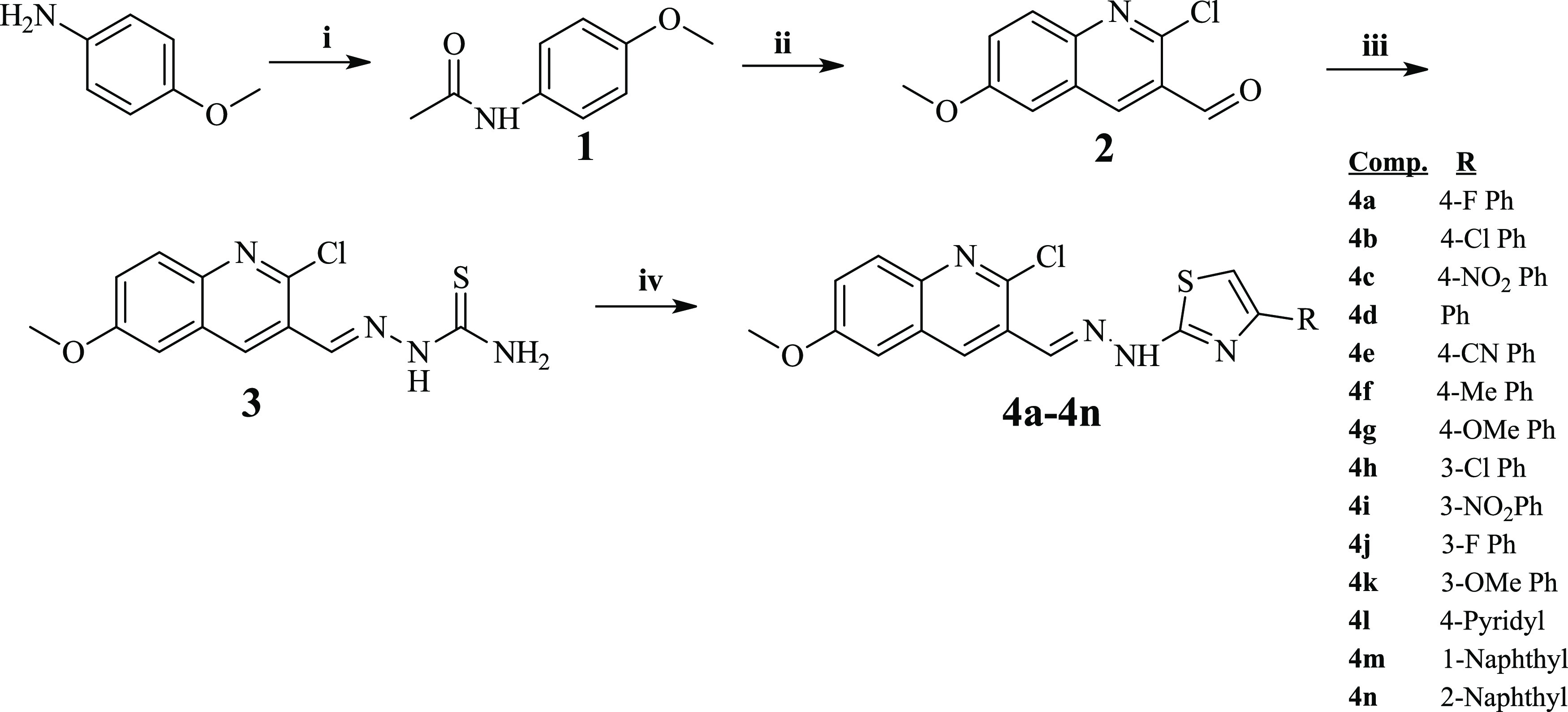

5.1.1. Synthesis of 4′-Methoxyacetanilide (1)

4-Anisidine (0.065 mol) and triethylamine (TEA) (0.078 mol) were dissolved in dichloromethane in a flask and placed in an ice bath at 0–5 °C. On the other hand, acetyl chloride (0.09 mol) was dissolved in dichloromethane in the dropping funnel and dropped carefully into the mixture in the flask. In the meantime, care was taken to mix the mixture vigorously. After the dripping was finished, it was left to stir for another 3 h at room temperature. The end of the reaction was checked with TLC. The solvent was completely evaporated, and the solid was washed with water, filtered, and then dried. The product was crystallized from ethanol.

5.1.2. Synthesis of 2-Chloro-6-methoxyquinoline-3-carbaldehyde (2)

N-(4-Methoxyphenyl)acetamide (1, 1 equiv) was stirred with Vilsmeier reagent in a hot water bath. After 4 h of stirring, the reaction was checked with TLC. Then, the mixture in the balloon was poured into the icy water. The solid product was washed with water, filtered, and left to dry. The dried product was crystallized from ethanol.

5.1.3. Synthesis of 2-[(2-Chloro-6-methoxyquinolin-3-yl)methylene]hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (3)

2-Chloro-6-methoxyquinoline-3-carbaldehyde (2, 0.040 mol) and thiosemicarbazide (0.040 mol) were refluxed in ethanol. The reaction was terminated by TLC control. The precipitated part was filtered and separated from the alcohol. After the solvent was evaporated, the crude product was crystallized from ethanol.

5.1.4. 2-[2-((2-Chloro-6-methoxyquinolin-3-yl)methylene)hydrazinyl]-4-Substituted Thiazole Derivatives (4a–m)

1-Aryl-2-bromoethanone derivatives taken in equal moles with 2-[(2-chloro-6-methoxyquinolin-3-yl)methylene]hydrazine-1-carbothioamide were refluxed in alcohol for 2 h. The end of the reaction was controlled with TLC, and the final products were filtered and separated from the alcohol. After the solvent was evaporated, the crude products were recrystallized from ethanol.

The reaction procedure is displayed in Scheme 1. The synthesized compounds and their results of the spectra are shared between Sections 1.1 and 1.14 in the Supporting Information.

Scheme 1. General Procedure for the Synthesis of the Compounds.

Reactions and conditions: (i) CH3COCl, tetrahydrofuran (THF), TEA, 0 °C, after dropping, room temperature (rt), 4 h; (ii) Vilsmeier–Haack reagent, 0 °C, then water bath, 8 h; (iii) thiosemicarbazide, EtOH, rt, 2 h; and (iv) 2-bromoethanone derivatives, EtOH, rt, 2 h.

5.2. Antimicrobial Activity Studies

E. coli (ATCC 35218), E. coli (ATCC 25922), S. aureus (ATCC 6538), methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (clinical isolate), S. typhimurium (ATCC 13311), and K. pneumoniae (NCTC 9633) cells for antibacterial effect, and C. albicans (ATCC 24433), C. glabrata (ATCC 90030), C. krusei (ATCC 6258), and C. parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) for the antifungal effect of the final compounds were used to determine the MIC90 values. The broth microdilution procedure specified in the M07-A9 document of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) was used for antibacterial study,55 and the EDef 7.1 document published by EUCAST was used for the antifungal study.56 For both activity studies, the detailed procedures were explained in previous studies.57,58

5.3. Cytotoxic Evaluation of the Final Compounds

NIH/3T3 cells were incubated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), added with fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 IU/mL), streptomycin (100 mg/mL), and 7.5% NaHCO3 at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. NIH/3T3 cells were seeded into the 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells. After 24 h of incubating period, the culture media were removed, and test compounds were added. After 24 h of incubation period, colorimetric measurements were performed by a microplate reader (Biotek) at 540 nm. Inhibition % at all concentrations was determined using the formula below, and the IC50 values were calculated from a dose–response curve obtained by plotting the percentage inhibition versus the log concentration with the use of Microsoft Excel 2013. The results were displayed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).59−61

5.4. Enzyme Inhibition Tests

5.4.1. Inhibition of DNA-Gyrase Enzyme

DNA gyrase obtained from E. coli was used to detect the inhibition of the superhelix activity of DNA gyrase. The method was performed according to the kit protocol described by the supplier (SKU TG2000G-3, TopoGen). The detailed procedures were explained in the previous study.62

5.4.2. Inhibition of Fungal LDM Enzyme

Ergosterol level was determined using the extract of total sterols from C. albicans (and its other species) following the method described by Breivik and Owades.63 Quantification of the ergosterol level in this extract was carried out by the recently described method.58,64−66 According to these described studies, in the current work, compounds 4b, 4e, 4f, and 4h–m were undertaken to investigate their action mechanism. Thus, the LC-MS-MS-based method that quantifies the ergosterol level was applied. All active anticandidal compounds, ketoconazole, and fluconazole were used at 3.91, 0.98, 0.24, and 0.06 μg/mL concentrations. Ergosterol quantity in negative control samples was regarded as 100%. All concentrations were analyzed in quadruplicate, and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

5.4.3. Inhibition of Human Aromatase Enzyme

Since targeting human aromatase enzyme was reported for antifungal activity and it plays a pivotal role in fungal cell function,40 compounds that showed antifungal activity were evaluated for inhibition activity on aromatase enzyme using a kit procedure (Bio Vision, Aromatase (CYP19A) Inhibitor Screening Kit (Fluorometric)), as described in previous studies.67−69

5.5. In Silico Studies

The pharmacokinetic profile was predicted viain silico methods. The active compounds may be considered in the future for in vivo pharmacokinetic studies as the current study is involved basically in the evaluation of the activity. Therefore, the medicinal chemistry and pharmacokinetic profiles of the designed compounds were calculated using the Swiss-ADME web-based program.70

All docking studies on various enzymes were performed using the Schrodinger Maestro Suite program. The interfaces of this program are used for the protein preparation process, ligand preparation process, grid generation, docking, and visualization studies.71−73 The crystal structure of the enzymes was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank server (PDB codes: 2XCT, 3EQM, and 5TZ1 for DNA gyrase, aromatase, and lanosterol 14α-demethylase). All ligands were set to the physiological pH (pH = 7.4) at the protonation step. The proteins were prepared according to the previous studies.34,62,67

The molecular dynamics simulations (MDS) were performed using the Maestro Desmond interface program.74 All molecular dynamics simulations (MDS) for 100 ns were carried out to analyze the stability of the identified hits from the in vitro docking results. Preparing the system setup, performing molecular dynamics simulations, and calculating the interaction analysis were carried out according to the same procedure as previous studies.67,75 All systems were set up using “System Builder” in Maestro. The complex structure was subjected to energy minimization (OPLS3e standard force field). Transferable intermolecular potential with the 3-point water model was used for the creation of the hydration model. The neutralization of the system was achieved using Na+ and Cl– ions. The molecular dynamic simulation was performed following the completion of the system setup. The radius of gyration (Rg), root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values were calculated by the Desmond application.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank DOPNA laboratory, Anadolu University.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c06871.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and validation, L.Y., A.E.E., and Y.O.; methodology, software, and formal analysis, A.E.E. and B.N.S.; investigation, A.E.E., B.N.S., and A.B.K.; resources, L.Y., A.E.E. and B.N.S.; data curation and writing—original draft preparation, L.Y. and A.E.E.; writing—review and editing, B.N.S., A.B.K., and Y.O.; visualization, A.E.E. and B.N.S.; and supervision, L.Y. and Y.O.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Schlossberg D.Clinical Infectious Disease; Cambridge University Press: Philadelphia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alberts B.; Johnson A.; Lewis J.; Walter P.; Raff M.; Roberts K.. Pathogens, Infection, and Innate Immunity, International Student ed.; Routledge: New York, 2002; pp 1485–1538. [Google Scholar]

- Peng X. M.; Cai G. X.; Zhou C. H. Recent developments in azole compounds as antibacterial and antifungal agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 1963–2010. 10.2174/15680266113139990125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Garcia A.; Rementeria A.; Aguirre-Urizar J. M.; Moragues M. D.; Antoran A.; Pellon A.; Abad-Diaz-de-Cerio A.; Hernando F. L. Candida albicans and cancer: Can this yeast induce cancer development or progression?. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 42, 181–193. 10.3109/1040841X.2014.913004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 2002, 415, 389–395. 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitis M.; Mylonakis E. Fungal-bacterial interactions and their relevance in health. Cell Microbiol. 2015, 17, 1442–1446. 10.1111/cmi.12493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsenault A. B.; Bliss J. M. Neonatal Candidiasis: New Insights into an Old Problem at a Unique Host-Pathogen Interface. Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 2015, 9, 246–252. 10.1007/s12281-015-0238-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead P. S.; Slutsker L.; Dietz V.; McCaig L. F.; Bresee J. S.; Shapiro C.; Griffin P. M.; Tauxe R. V. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerging Infect. Dis. 1999, 5, 607–625. 10.3201/eid0505.990502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N.; Rogers P.; Atwood C. W.; Wagener M. M.; Yu V. L. Short-course empiric antibiotic therapy for patients with pulmonary infiltrates in the intensive care unit. A proposed solution for indiscriminate antibiotic prescription. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 162, 505–511. 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9909095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehra A.; Gulzar M.; Singh R.; Kaur S.; Gill J. P. S. Prevalence, multidrug resistance and molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in retail meat from Punjab, India. J. Global Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 16, 152–158. 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tfifha M.; Ferjani A.; Mallouli M.; Mlika N.; Abroug S.; Boukadida J. Carriage of multidrug-resistant bacteria among pediatric patients before and during their hospitalization in a tertiary pediatric unit in Tunisia. Libyan J. Med. 2018, 13, 1419047 10.1080/19932820.2017.1419047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyanaga M.; Nejima R.; Miyai T.; Miyata K.; Ohashi Y.; Inoue Y.; Toyokawa M.; Asari S. Changes in drug susceptibility and the quinolone-resistance determining region of Staphylococcus epidermidis after administration of fluoroquinolones. J. Cataract Refractive Surg. 2009, 35, 1970–1978. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd B. Reconsidering Antibiotic Resistance. Am. J. Nurs. 2017, 117, 66–67. 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000527492.32234.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellberg B. The New Antibiotic Mantra-″Shorter Is Better″. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 1254–1255. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Z.; Ahmad S.; Benwan K.; Purohit P.; Al-Obaid I.; Bafna R.; Emara M.; Mokaddas E.; Abdullah A. A.; Al-Obaid K.; Joseph L. Invasive Candida auris infections in Kuwait hospitals: epidemiology, antifungal treatment and outcome. Infection 2018, 46, 641–650. 10.1007/s15010-018-1164-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nweke M. C.; Okolo C. A.; Daous Y.; Esan O. A. Challenges of Human Papillomavirus Infection and Associated Diseases in Low-Resource Countries. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2018, 142, 696–699. 10.5858/arpa.2017-0565-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S. B.; Marshall B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, S122–S129. 10.1038/nm1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan P.; Courtenay M.. Treatment of Infection. Prescribing in Dermatology; Cambridge University Press: Philadelphia, 2006; pp 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald A. R.; Turck M.; Petersdorf R. G. A critical evaluation of nalidixic acid in urinary-tract infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 1966, 275, 1081–1089. 10.1056/NEJM196611172752001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G.; Wang G.; Duan N.; Wen X.; Cao T.; Xie S.; Huang W. Design, synthesis and antitumor activities of fluoroquinolone C-3 heterocycles (IV): s-triazole Schiff–Mannich bases derived from ofloxacin. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2012, 2, 312–317. 10.1016/j.apsb.2011.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saura C.; Garcia-Saenz J. A.; Xu B.; Harb W.; Moroose R.; Pluard T.; Cortes J.; Kiger C.; Germa C.; Wang K.; Martin M.; Baselga J.; Kim S. B. Safety and efficacy of neratinib in combination with capecitabine in patients with metastatic human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 3626–3633. 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.3809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N.; Song Y.; Du P.; Shen Y.; Yang J.; Gui L.; Wang S.; Wang J.; Sun Y.; Han X.; Shi Y. Oral topotecan: Bioavailability, pharmacokinetics and impact of ABCG2 genotyping in Chinese patients with advanced cancers. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2013, 67, 801–806. 10.1016/j.biopha.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt P. M.; Hickson I. D. Structure and function of type II DNA topoisomerases. Biochem. J. 1994, 303, 681–695. 10.1042/bj3030681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musiol R.; Serda M.; Hensel-Bielowka S.; Polanski J. Quinoline-based antifungals. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 1960–1973. 10.2174/092986710791163966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senerovic L.; Opsenica D.; Moric I.; Aleksic I.; Spasic M.; Vasiljevic B.. Quinolines and Quinolones as Antibacterial, Antifungal, Anti-virulence, Antiviral and Anti-parasitic Agents. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer, 2020; Vol. 1282, pp 37–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. J.; Ma K. Y.; Du S. S.; Zhang Z. J.; Wu T. L.; Sun Y.; Liu Y. Q.; Yin X. D.; Zhou R.; Yan Y. F.; Wang R. X.; He Y. H.; Chu Q. R.; Tang C. Antifungal Exploration of Quinoline Derivatives against Phytopathogenic Fungi Inspired by Quinine Alkaloids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 12156–12170. 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c05677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra S.; Cramer R. A. Regulation of Sterol Biosynthesis in the Human Fungal Pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus: Opportunities for Therapeutic Development. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 92 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupetti A.; Danesi R.; Campa M.; Del Tacca M.; Kelly S. Molecular basis of resistance to azole antifungals. Trends Mol. Med. 2002, 8, 76–81. 10.1016/S1471-4914(02)02280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma A. K.; Majid A.; Hossain M. S.; Ahmed S. F.; Ashid M.; Bhojiya A. A.; Upadhyay S. K.; Vishvakarma N. K.; Alam M. Identification of 1, 2, 4-Triazine and Its Derivatives Against Lanosterol 14-Demethylase (CYP51) Property of Candida albicans: Influence on the Development of New Antifungal Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Med. Technol. 2022, 4, 845322 10.3389/fmedt.2022.845322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Ramamoorthy Y.; Kilicarslan T.; Nolte H.; Tyndale R. F.; Sellers E. M. Inhibition of cytochromes P450 by antifungal imidazole derivatives. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002, 30, 314–318. 10.1124/dmd.30.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng C.; Miao Z.; Ji H.; Yao J.; Wang W.; Che X.; Dong G.; Lu J.; Guo W.; Zhang W. Three-dimensional model of lanosterol 14 alpha-demethylase from Cryptococcus neoformans: active-site characterization and insights into azole binding. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 3487–3495. 10.1128/AAC.01630-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guedes P. M. d. M.; Urbina J. A.; de Lana M.; Afonso L. C.; Veloso V. M.; Tafuri W. L.; Machado-Coelho G. L.; Chiari E.; Bahia M. T. Activity of the new triazole derivative albaconazole against Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi in dog hosts. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 4286–4292. 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4286-4292.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav M.; Lal K.; Kumar A.; Kumar A.; Kumar D. Indole-chalcone linked 1,2,3-triazole hybrids: Facile synthesis, antimicrobial evaluation and docking studies as potential antimicrobial agents. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1261, 132867 10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.132867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lebouvier N.; Pagniez F.; Na Y. M.; Shi D.; Pinson P.; Marchivie M.; Guillon J.; Hakki T.; Bernhardt R.; Yee S. W.; Simons C.; Leze M. P.; Hartmann R. W.; Mularoni A.; Le Baut G.; Krimm I.; Abagyan R.; Le Pape P.; Le Borgne M. Synthesis, Optimization, Antifungal Activity, Selectivity, and CYP51 Binding of New 2-Aryl-3-azolyl-1-indolyl-propan-2-ols. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 186 10.3390/ph13080186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T.; Chen X.; Li C.; Tu J.; Liu N.; Xu D.; Sheng C. Lanosterol 14alpha-demethylase (CYP51)/histone deacetylase (HDAC) dual inhibitors for treatment of Candida tropicalis and Cryptococcus neoformans infections. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 221, 113524 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccallini C.; Gallorini M.; Sisto F.; Akdemir A.; Ammazzalorso A.; De Filippis B.; Fantacuzzi M.; Giampietro L.; Carradori S.; Cataldi A.; Amoroso R. New azolyl-derivatives as multitargeting agents against breast cancer and fungal infections: synthesis, biological evaluation and docking study. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021, 36, 1632–1645. 10.1080/14756366.2021.1954918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friggeri L.; Hargrove T. Y.; Wawrzak Z.; Guengerich F. P.; Lepesheva G. I. Validation of Human Sterol 14alpha-Demethylase (CYP51) Druggability: Structure-Guided Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Stoichiometric, Functionally Irreversible Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 10391–10401. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarn J. A.; Bruschweiler B. J.; Schlatter J. R. Azole fungicides affect mammalian steroidogenesis by inhibiting sterol 14 alpha-demethylase and aromatase. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003, 111, 255–261. 10.1289/ehp.5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trösken E. R.; Scholz K.; Lutz R. W.; Volkel W.; Zarn J. A.; Lutz W. K. Comparative assessment of the inhibition of recombinant human CYP19 (aromatase) by azoles used in agriculture and as drugs for humans. Endocr. Res. 2004, 30, 387–394. 10.1081/ERC-200035093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trösken E. R.; Fischer K.; Volkel W.; Lutz W. K. Inhibition of human CYP19 by azoles used as antifungal agents and aromatase inhibitors, using a new LC-MS/MS method for the analysis of estradiol product formation. Toxicology 2006, 219, 33–40. 10.1016/j.tox.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albengres E.; Le Louet H.; Tillement J. P. Systemic antifungal agents. Drug interactions of clinical significance. Drug Saf. 1998, 18, 83–97. 10.2165/00002018-199818020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ören İ.; Temiz Ö.; Yalçın İ.; Şener E.; Altanlar N. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of some novel 2,5- and/or 6-substituted benzoxazole and benzimidazole derivatives. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 1999, 7, 153–160. 10.1016/S0928-0987(98)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdik E.Organik kimyada spektroskopik yöntemler; Gazi Kitapevi: Ankara, 1998; Vol. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Erdik E.; Obalı M.; Yüksekışık N.; Öktemer A.; Pekel T.. Denel Organik Kimya, 4th ed.; Gazi Kitabevi: Ankara, Türkiye, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Luan G.; Ren X.; Song W.; Xu L.; Xu M.; Zhu J.; Dong D.; Diao Y.; Liu X.; Zhu L.; Wang R.; Zhao Z.; Xu Y.; Li H. Rational Design of Benzylidenehydrazinyl-Substituted Thiazole Derivatives as Potent Inhibitors of Human Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase with in Vivo Anti-arthritic Activity. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14836 10.1038/srep14836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukeš V.; Michalík M.; Poliak P.; Cagardová D.; Végh D.; Bortňák D.; Fronc M.; Kožíšek J. Theoretical and experimental study of model oligothiophenes containing 1-methylene-2-(perfluorophenyl)hydrazine terminal unit. Synth. Met. 2016, 219, 83–92. 10.1016/j.synthmet.2016.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aly A. A.; Mohamed A. H.; Ramadan M. Synthesis and colon anticancer activity of some novel thiazole/-2-quinolone derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1207, 127798 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.127798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder G. M.; An Y.; Cai Z. W.; Chen X. T.; Clark C.; Cornelius L. A.; Dai J.; Gullo-Brown J.; Gupta A.; Henley B.; Hunt J. T.; Jeyaseelan R.; Kamath A.; Kim K.; Lippy J.; Lombardo L. J.; Manne V.; Oppenheimer S.; Sack J. S.; Schmidt R. J.; Shen G.; Stefanski K.; Tokarski J. S.; Trainor G. L.; Wautlet B. S.; Wei D.; Williams D. K.; Zhang Y.; Zhang Y.; Fargnoli J.; Borzilleri R. M. Discovery of N-(4-(2-amino-3-chloropyridin-4-yloxy)-3-fluorophenyl)-4-ethoxy-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridine-3-carboxamide (BMS-777607), a selective and orally efficacious inhibitor of the Met kinase superfamily. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 1251–1254. 10.1021/jm801586s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts R. O.; Guy R. H. Predicting skin permeability. Pharm. Res. 1992, 9, 663–669. 10.1023/A:1015810312465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P. F.; Srikannathasan V.; Huang J.; Cui H.; Fosberry A. P.; Gu M.; Hann M. M.; Hibbs M.; Homes P.; Ingraham K.; Pizzollo J.; Shen C.; Shillings A. J.; Spitzfaden C. E.; Tanner R.; Theobald A. J.; Stavenger R. A.; Bax B. D.; Gwynn M. N. Structural basis of DNA gyrase inhibition by antibacterial QPT-1, anticancer drug etoposide and moxifloxacin. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10048 10.1038/ncomms10048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargrove T. Y.; Friggeri L.; Wawrzak Z.; Qi A.; Hoekstra W. J.; Schotzinger R. J.; York J. D.; Guengerich F. P.; Lepesheva G. I. Structural analyses of Candida albicans sterol 14alpha-demethylase complexed with azole drugs address the molecular basis of azole-mediated inhibition of fungal sterol biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 6728–6743. 10.1074/jbc.M117.778308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepesheva G. I.; Waterman M. R. Structural basis for conservation in the CYP51 family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2011, 1814, 88–93. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.; Czapla L.; Amaro R. E. Molecular simulations of aromatase reveal new insights into the mechanism of ligand binding. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013, 53, 2047–2056. 10.1021/ci400225w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y.; Li H.; Yuan Y. C.; Chen S. Molecular characterization of aromatase. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1155, 112–120. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI . Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard, CLSI document M07-A9, 9th ed.; CLSI, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Tudela J. L.; Arendrup M.; Barchiesi F.; et al. EUCAST definitive document EDef 7.1: method for the determination of broth dilution MICs of antifungal agents for fermentative yeasts. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 398–405. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evren A. E.; Dawbaa S.; Nuha D.; Yavuz Ş. A.; Gül Ü. D.; Yurttaş L. Design and synthesis of new 4-methylthiazole derivatives: In vitro and in silico studies of antimicrobial activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1241, 130692 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osmaniye D.; Kaya Cavusoglu B.; Saglik B. N.; Levent S.; Acar Cevik U.; Atli O.; Ozkay Y.; Kaplancikli Z. A. Synthesis and Anticandidal Activity of New Imidazole-Chalcones. Molecules 2018, 23, 831 10.3390/molecules23040831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sağlık B. N.; Sen A. M.; Evren A. E.; Cevik U. A.; Osmaniye D.; Kaya Cavusoglu B.; Levent S.; Karaduman A. B.; Ozkay Y.; Kaplancikli Z. A. Synthesis, investigation of biological effects and in silico studies of new benzimidazole derivatives as aromatase inhibitors. Z. Naturforsch., C 2020, 75, 353–362. 10.1515/znc-2020-0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmaniye D.; Levent S.; Sağlık B. N.; Karaduman A. B.; Özkay Y.; Kaplancıklı Z. A. Novel imidazole derivatives as potential aromatase and monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors against breast cancer. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 7442–7451. 10.1039/D2NJ00424K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Çevik U. A.; Osmaniye D.; Sağlik B. N.; Çavuşoğlu B. K.; Levent S.; Karaduman A. B.; Ilgin S.; Karaburun A. Ç.; Özkay Y.; Kaplancikli Z. A.; Turan G. Multifunctional quinoxaline-hydrazone derivatives with acetylcholinesterase and monoamine oxidases inhibitory activities as potential agents against Alzheimer’s disease. Med. Chem. Res. 2020, 29, 1000–1011. 10.1007/s00044-020-02541-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gençer H. K.; Levent S.; Acar Cevik U.; Ozkay Y.; Ilgin S. New 1,4-dihydro[1,8]naphthyridine derivatives as DNA gyrase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 1162–1168. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivik O. N.; Owades J. L. Yeast Analysis, Spectrophotometric Semimicrodetermination of Ergosterol in Yeast. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1957, 5, 360–363. 10.1021/jf60075a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levent S.; Kaya Cavusoglu B.; Saglik B. N.; Osmaniye D.; Acar Cevik U.; Atli O.; Ozkay Y.; Kaplancikli Z. A. Synthesis of Oxadiazole-Thiadiazole Hybrids and Their Anticandidal Activity. Molecules 2017, 22, 2004 10.3390/molecules22112004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplancıklı Z. A.; Levent S.; Osmaniye D.; Saglik B. N.; Cevik U. A.; Cavusoglu B. K.; Ozkay Y.; Ilgin S. Synthesis and Anticandidal Activity Evaluation of New Benzimidazole-Thiazole Derivatives. Molecules 2017, 22, 2051 10.3390/molecules22122051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Can N. O.; Acar Çevik U.; Sağlık B. N.; Levent S.; Korkut B.; Özkay Y.; Kaplancıklı Z. A.; Koparal A. S. Synthesis, Molecular Docking Studies, and Antifungal Activity Evaluation of New Benzimidazole-Triazoles as Potential Lanosterol 14α-Demethylase Inhibitors. J. Chem. 2017, 2017, 9387102 10.1155/2017/9387102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evren A. E.; Nuha D.; Dawbaa S.; Saglik B. N.; Yurttas L. Synthesis of novel thiazolyl hydrazone derivatives as potent dual monoamine oxidase-aromatase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 229, 114097 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.114097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmaniye D.; Levent S.; Sağlık B. N.; Karaduman A. B.; Ozkay Y.; Kaplancikli Z. A. Novel Imidazole Derivatives as Potential Aromatase and Monoamine Oxidase-B Inhibitors Against Breast Cancer. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 7442. 10.1039/D2NJ00424K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Acar Çevik U.; Kaya Cavusoglu B.; Saglik B. N.; Osmaniye D.; Levent S.; Ilgin S.; Ozkay Y.; Kaplancikli Z. A. Synthesis, Docking Studies and Biological Activity of New Benzimidazole- Triazolothiadiazine Derivatives as Aromatase Inhibitor. Molecules 2020, 25, 1642 10.3390/molecules25071642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A.; Michielin O.; Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger Release 2020-3, Maestro; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, 2020.

- Schrödinger Release 2020-3, Glide; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, 2020.

- Schrödinger Release 2020-3: LigPrep 2020; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, 2020.

- Schrödinger Release 2020-3, Desmond; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, 2020.

- Osmaniye D.; Evren A. E.; Saglik B. N.; Levent S.; Ozkay Y.; Kaplancikli Z. A. Design, synthesis, biological activity, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics of novel benzimidazole derivatives as potential AChE/MAO-B dual inhibitors. Arch. Pharm. 2022, 355, 2100450 10.1002/ardp.202100450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.