Abstract

Ribosomal incorporation of d-α-amino acids (dAA) and N-methyl-l-α-amino acids (MeAA) with negatively charged sidechains, such as d-Asp, d-Glu, MeAsp and MeGlu, into nascent peptides is far more inefficient compared to those with neutral or positively charged ones. This is because of low binding affinity of their aminoacyl-transfer RNA (tRNA) to elongation factor-thermo unstable (EF-Tu), a translation factor responsible for accommodation of aminoacyl-tRNA onto ribosome. It is well known that EF-Tu binds to two parts of aminoacyl-tRNA, the amino acid moiety and the T-stem; however, the amino acid binding pocket of EF-Tu bearing Glu and Asp causes electric repulsion against the negatively charged amino acid charged on tRNA. To circumvent this issue, here we adopted two strategies: (i) use of an EF-Tu variant, called EF-Sep, in which the Glu216 and Asp217 residues in EF-Tu are substituted with Asn216 and Gly217, respectively; and (ii) reinforcement of the T-stem affinity using an artificially developed chimeric tRNA, tRNAPro1E2, whose T-stem is derived from Escherichia coli tRNAGlu that has high affinity to EF-Tu. Consequently, we could successfully enhance the incorporation efficiencies of d-Asp, d-Glu, MeAsp and MeGlu and demonstrated for the first time, to our knowledge, ribosomal synthesis of macrocyclic peptides containing multiple d-Asp or MeAsp.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Reactivity and mechanism in chemical and synthetic biology’.

Keywords: EF-Tu, EF-Sep, d-amino acid, N-methyl-amino acid, tRNA, T-stem

1. Introduction

d-α-amino acids (dAA) and N-methyl-l-α-amino acids (MeAA) are often found in natural bioactive peptides. dAA and MeAA contribute to biological and pharmacological properties of peptides such as high proteolytic stability, target affinity and membrane permeability [1–13], and therefore are practical components for development of novel peptide drugs. Although natural bioactive peptides bearing dAA and MeAA are generally synthesized by multienzyme clusters called non-ribosomal peptide synthetases [14,15] or post-translational modification enzymes [16,17], direct ribosomal incorporation of diverse dAA and MeAA into nascent peptides has also been demonstrated to date by using artificially charged dAA-transfer RNA (tRNA) or MeAA-tRNA [18–28]. However, incorporation of dAA and MeAA with negatively charged sidechains, such as d-Asp, d-Glu, MeAsp and MeGlu (figure 1a), is much less efficient than those of neutral or positively charged ones. Fujino et al. [20] evaluated the incorporation of 19 dAA derived from the 19 proteinogenic l-α-amino acids except for Gly using an Escherichia coli tRNAAsn-based orthogonal tRNA, tRNAAsnE2. Unfortunately, neither d-Asp nor d-Glu could be successfully incorporated into a model peptide, whereas the other dAA could be incorporated except for d-Pro, d-Lys and d-Ile. Later on, Achenbach et al. [21] showed a possibility of d-Asp incorporation into model peptides using tRNAGly, but identities of the peptides containing d-Asp were not verified in their study. Kawakami et al. [27] evaluated incorporation of 19 MeAA derived from the 19 proteinogenic l-amino acids, except for Pro, using an orthogonal tRNA, tRNAAsnE1; however, neither MeAsp nor MeGlu could be introduced.

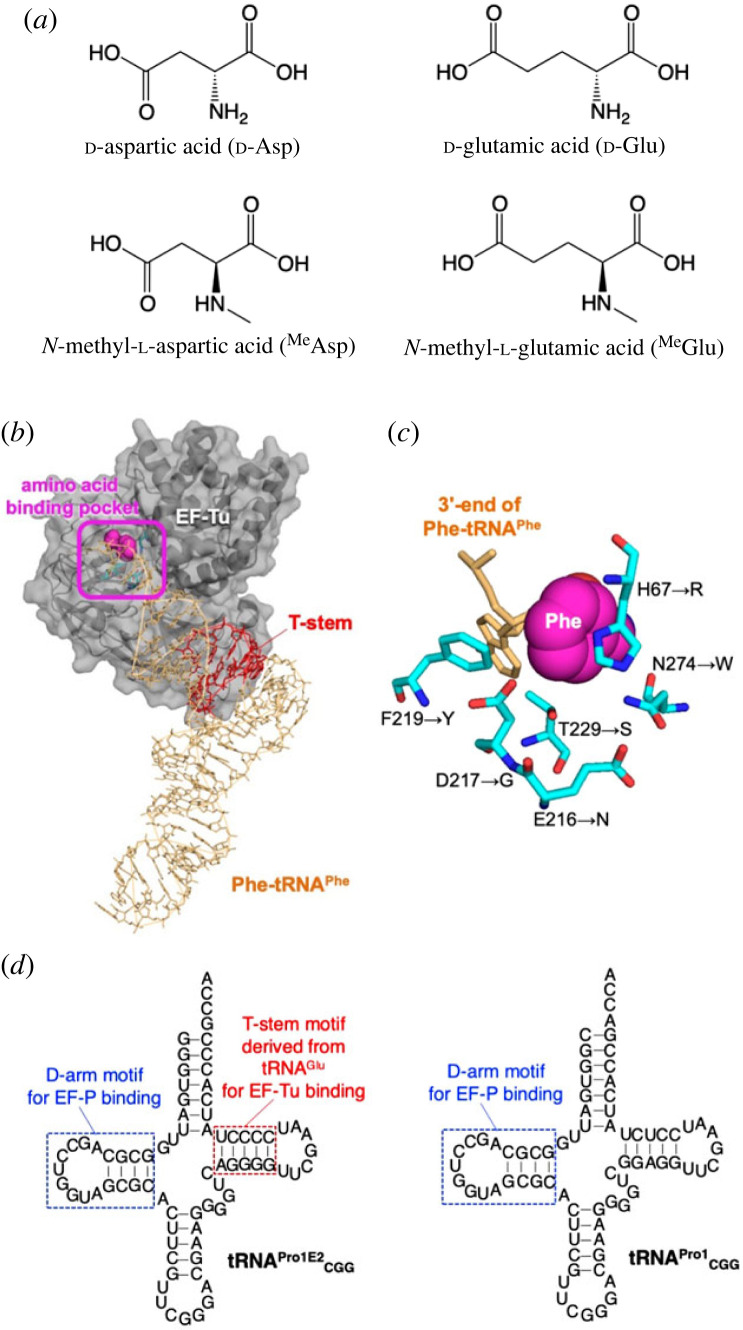

Figure 1.

Structures of negatively charged dAA and MeAA, EF-Tu, EF-Sep and tRNA used in this study. (a) Structures and abbreviations of negatively charged dAA and MeAA used in this study. (b) Structure of E. coli EF-Tu bound to Saccharomyces cerevisiae Phe-tRNAPhe (PDB: 1OB2). (c) Structure of the amino acid binding pocket of E. coli EF-Tu (PDB ID: 1OB2). 3'-End of S. cerevisiae Phe-tRNAPhe bound to the pocket is shown in orange. Mutations in EF-Sep are indicated by arrows. (d) Secondary structure of tRNAPro1E2CGG and tRNAPro1CGG used for incorporation of dAA and MeAA at the CCG codon. The T-stem motif derived from E. coli tRNAGlu for improved EF-Tu binding is indicated by red. The D-arm motif for tight EF-P binding consists of a 9-nt D-loop closed by a stable 4 bp stem (indicated by blue). See also the electronic supplementary material, table S1 for the sequences. (Online version in colour.)

A reason for their low incorporation efficiency could be attributed to the low binding affinity of aminoacyl-tRNA to elongation factor-thermo unstable (EF-Tu), a translation factor responsible for accommodation of aminoacyl-tRNA onto the ribosome A site. It has been reported that EF-Tu recognizes two parts of aminoacyl-tRNA: the amino acid moiety and the T-stem (figure 1b) [29–31]. Since the amino acid binding pocket of EF-Tu has two negatively charged amino acids, E216 and D217, the affinity of negatively charged aminoacyl-tRNA to this site should be lower than those bearing neutral or positively charged ones owing to the electric repulsion. Uhlenbeck and colleagues showed that E. coli tRNAGlu has the strongest binding affinity to EF-Tu among the 21 E. coli tRNAs tested in their study [30]. For instance, the binding energies (ΔG°) of Val-tRNAGlu and Val-tRNAGln to EF-Tu were −11.7 and −8.3 kcal mol−1, respectively. This is because the weak affinity of l-Glu to the amino acid binding pocket needs to be compensated for by the strong affinity of the T-stem region of tRNAGlu [32–36]. In fact, mischarged Glu-tRNAGln is poorly accommodated onto the ribosome A site owing to the insufficient EF-Tu affinity, resulting in inefficient peptide synthesis [37]. Moreover, in the case of d-Asp, d-Glu, MeAsp and MeGlu, their d-configuration and N-methylation should further hinder their binding to EF-Tu because of their structural incompatibility. Iwane et al. [38] determined the binding affinities of Phe-tRNAAsnE2#3 and MePhe-tRNAAsnE2#3 to EF-Tu to be −9.3 and −7.9 kcal mol−1, respectively, indicating that N-methylation significantly reduced the affinity of aminoacyl-tRNA (note that tRNAAsnE2#3 is a variant of tRNAAsnE2 whose T-stem was substituted with that of tRNAGlu). These results indicate that compensation of the T-stem affinity is required for incorporation of MeAA in general. In fact, Iwane et al. [38] have succeeded in enhancing incorporation of various MeAA by optimizing T-stem structure to reinforce their affinity. Yet, the enhancement of incorporation of MeAsp and MeGlu remains elusive by such tRNA engineering.

In order to enhance the affinity of negatively charged amino acids, EF-Tu variants bearing mutations around the amino acid binding pocket have been developed in several previous studies. Park et al. [39] reported that an engineered EF-Tu, where six mutations around the binding pocket (figure 1c, H67R, E216N, D217G, F219Y, T229S and N274W) were introduced, was able to bind a suppressor tRNA charged O-phosphoserine (Sep). This EF-Tu mutant was referred to as EF-Sep. Using similar approaches introducing mutations to EF-Tu, EF-pY and EF-Sel1, containing three (E216V, D217G and F219G) and five mutations (H67R, Q98W, E216N, D217K and N274R), respectively, have also been developed for enabling the introduction of l-phosphotyrosine (pTyr) and selenocysteine (Sec), respectively [40,41]. All of these EF-Tu variants have substitutions of the negatively charged E216 and D217 with neutral or positively charged residues. Although these variants have been shown to enhance incorporation of Sep, pTyr and Sec, they were not applied to incorporation of other non-proteinogenic amino acids to the best of our knowledge. On the basis of these preceding studies, here we took advantage of EF-Sep in combination with the T-stem affinity reinforcement strategy to achieve the incorporation of negatively charged dAA and MeAA into nascent peptides.

2. Material and methods

(a) . In vitro transcription of transfer RNAs and flexizymes

DNA templates used for transcription of tRNAs and flexizymes (dFx and eFx) were prepared by extension and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the forward and reverse primer pairs summarized in the electronic supplementary material, table S1. Transcription of tRNAs and flexizymes was carried out overnight at 37°C in 4 ml of the following reaction mixture: 40 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) mix, 22.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM spermidine, 0.01% Triton X-100, 0.04 U µl−1 RNasin RNase inhibitor (Promega) and 0.12 µM T7 RNA polymerase. In the case of tRNA preparation, 5 mM guanosine monophosphate was added to the above mixture and the concentration of NTP mix was reduced to 3.75 mM. The transcribed RNAs were treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega) for 30 min at 37°C and purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 8% (tRNAs) or 12% (flexizymes) polyacrylamide gel containing 6 M urea.

(b) . Preparation of aminoacyl-transfer RNAs

d-Asp, d-Glu, MeAsp, MeGlu and d-Cys were pre-activated as 3,5-dinitrobenzylester (DBE) and ClAcd-Phe was pre-activated as a cyanomethyl ester according to the previously reported methods [20,42,43]. dFx was used for charging amino acids-DBE onto tRNAPro1E2; eFx was used for preparation of ClAcd-Phe-tRNAfMet. The reactions were performed at 4°C for 2, 2, 24, 6, 6 and 2 h for aminoacylation of d-Asp, d-Glu, MeAsp, MeGlu, d-Cys and ClAcd-Phe, respectively, in the following reaction mixture: 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 600 mM MgCl2, 20% dimethyl sulfoxide, 25 µM eFx or dFx, 25 µM tRNA and 5 mM activated amino acid. The resulting aminoacyl-RNAs were recovered by ethanol precipitation and washed with 70% ethanol.

(c) . Ribosomal synthesis of model peptides

Ribosomal synthesis of model peptides was carried out at 37°C for 30 min in a custom-made flexible in vitro translation (FIT) system of the following composition [44]: 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.6), 100 mM potassium acetate, 12.8 mM magnesium acetate, 2 mM ATP, 2 mM GTP, 1 mM CTP, 1 mM UTP, 20 mM creatine phosphate, 0.1 mM 10-formyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrofolic acid, 2 mM spermidine, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1.5 mg ml−1 E. coli total tRNA, 1.2 µM E. coli ribosome, 0.6 µM methionyl-tRNA formyltransferase, 2.7 µM IF1, 3 µM IF2, 1.5 µM IF3, 0.1 µM EF-G, 20 µM EF-Tu, 5 µM EF-Sep, 20 µM EF-Ts, 5 µM EF-P, 0.25 µM RF2, 0.17 µM RF3, 0.5 µM RRF, 4 µg ml−1 creatine kinase, 3 µg ml−1 myokinase, 0.1 µM inorganic pyrophosphatase, 0.1 µM nucleotide diphosphate kinase, 0.5 µM DNA template, 0.1 µM T7 RNA polymerase, 0.13 µM AspRS, 0.09 µM GlyRS, 0.11 µM LysRS, 0.03 µM MetRS, 0.02 µM TyrRS, 0.5 mM Asp, 0.5 mM Gly, 0.5 mM Lys, 0.5 mM Met, 0.5 mM Tyr and 20 µM each pre-charged aminoacyl-tRNAs. The concentrations of EF-Tu and EF-Sep were modified accordingly as mentioned in the results section. DNA templates were transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA) by T7 RNA polymerase included in the translation system, and then translated into peptides. Preparation of the DNA templates were performed by extension and PCR using the corresponding forward and reverse primer pairs (electronic supplementary material, table S1). In the case of translation of macrocyclic peptide P3, 10-formyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrofolic acid and Met were removed from the above reaction mixture, where 12.5 µM ClAcd-Phe-tRNAfMet was added for reprogramming the initiator AUG codon.

(d) . Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometric analysis of ribosomally synthesized model peptides

Of the above translation reaction mix, 7.5 µl was diluted with 7.5 µl of 2× tris-buffered saline (TBS) buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6) and 300 mM NaCl), mixed with 5 µl slurry of anti-Flag M2 affinity gel (Sigma), and incubated with gentle rotation for 15 min at room temperature. The peptides on the anti-Flag gel were washed twice with 40 µl of 1× TBS buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6) and 150 mM NaCl) and eluted from the gel by adding 30 µl of 0.2% trifluoroacetic acid. The eluent was desalted with SPE C-tip (Nikkyo Technos) and co-crystallized with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid on a sample plate. The samples were analysed by UltrafleXtreme (Bruker Daltonics) in a reflector/positive mode, where peptide calibration standard II (Bruker Daltonics) was used for external mass calibration.

(e) . Quantification of ribosomally synthesized peptides by tricine sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography

For quantification of model peptides, the translation reaction was carried out in the presence of 0.05 mM [14C]-Asp instead of 0.5 mM cold [12C]-Asp so that the peptides were radiolabelled. Then, 2.5 µl of the translation reaction mixture was mixed with the same volume of stop solution (0.9 M Tris–HCl (pH 8.45), 8% SDS, 30% glycerol and 0.001% xylene cyanol) and incubated at 95°C for 3 min. The samples were then subjected to 15% tricine sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and analysed by autoradiography using a Typhoon FLA 7000 (Cytiva). Expression levels of peptides were normalized by the intensity of the [14C]-Asp band.

3. Results

(a) . Single incorporation of negatively charged d-α- and N-methyl-l-α-amino acids into a model peptide

d-Asp, d-Glu, MeAsp and MeGlu were introduced at a CCG codon of an mRNA, mR1, to synthesize peptide P1 (figure 2a). These amino acids were chemically esterified with 3,5-dinitrobenzyl alcohol, charged onto tRNAPro1E2 CGG using a flexizyme variant, called dFx [45] and added to the translation system. tRNAPro1E2 is an artificially developed chimeric tRNA based on E. coli tRNAPro1 whose T-stem is replaced with that of E. coli tRNAGlu [23] (figure 1d). Therefore, we can expect high binding affinity of the T-stem to EF-Tu and EF-Sep to promote accommodation of aminoacyl-tRNAPro1E2. Note that the previously reported binding energy values (ΔG°) of Val-tRNAGlu and Val-tRNAPro to EF-Tu were −11.7 and −9.3 kcal mol−1, respectively [30]. In addition, the D-arm motif derived from tRNAPro1 efficiently recruits EF-P and thereby promotes the peptidyl transfer reaction [46]. We have previously shown that the use of tRNAPro1E2 enables efficient incorporation of not only l-Pro but also various non-proteinogenic substrates such as dAA, α,α-dialkyl-amino acids, β-amino acids, γ-amino acids, α-aminoxy acids and α-hydrazino acids in the presence of EF-P [23,47–51].

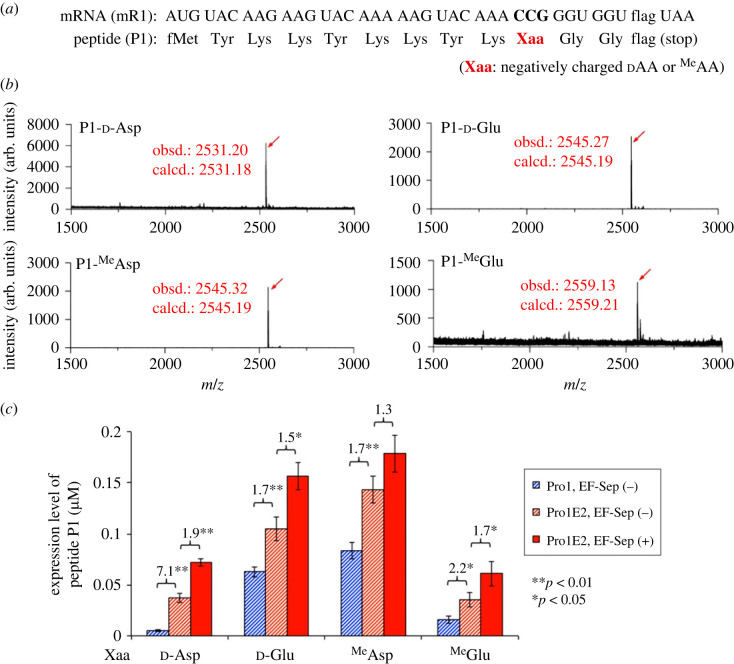

Figure 2.

Single incorporation of negatively charged dAA or MeAA into a model peptide. (a) Sequences of an mRNA (mR1) and the corresponding peptide (P1). Negatively charged dAA or MeAA, indicated by Xaa, were introduced at the CCG codon using pre-charged aminoacyl-tRNA. The amino acid sequence of ‘flag’ is Asp-Tyr-Lys-Asp-Asp-Asp-Asp-Lys. (b) MALDI-TOF MS of ribosomally synthesized P1 peptides, P1-Xaa, containing d-Asp, d-Glu, MeAsp or MeGlu. tRNAPro1E2CGG was used for incorporation of these amino acids at the CCG codon. Translation was carried out in the presence of 5 µM EF-Sep. Red arrows indicate monovalent ions ([M + H]+) of the desired products. ‘obsd.’ and ‘calcd.’ indicate observed and calculated m/z values, respectively. (c) Expression levels of P1-Xaa containing d-Asp, d-Glu, MeAsp or MeGlu. tRNAPro1E2CGG or tRNAPro1CGG was used for incorporation of these amino acids at the CCG codon. Translation reactions were carried out in the presence or absence of 5 µM EF-Sep. Numbers above the bars represent the ratio of the two bars. p-values were estimated by Student's t-test and indicated by asterisks (n = 3). See the electronic supplementary material, figure S1a for the raw data of tricine SDS–PAGE. (Online version in colour.)

Translation of the peptide was conducted in a reconstituted E. coli in vitro translation system, referred to as the FIT system [44], customized for inclusion of five proteinogenic amino acids (Met, Tyr, Lys, Asp and Gly) and the corresponding aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARSs); other proteinogenic amino acids and their ARSs were omitted. We have previously reported that an optimization of IF2, EF-G, EF-Tu and EF-P concentrations is critical for efficient incorporation of dAA, such as d-Ala, d-Ser, d-Cys and d-His [22,23]. Therefore, we applied the same concentrations of them as the previous reports (3 µM IF2, 0.1 µM EF-G, 20 µM EF-Tu and 5 µM EF-P). Note that the concentration of EF-Sep in this system was 5 µM unless otherwise indicated; both EF-Tu and EF-Sep were present in this FIT system. The resulting products were analysed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS), showing that all substrates could be successfully incorporated into the full-length desired peptides (figure 2b, P1-d-Asp, P1-d-Glu, P1-MeAsp and P1-MeGlu).

To evaluate the expression level, peptide P1 was translated in the presence of [14C]-labelled Asp in place of cold [12C]-Asp, separated by tricine SDS–PAGE and quantified by autoradiography (figure 2c; electronic supplementary material, figure S1a). In order to confirm the significance of the reinforced T-stem affinity, tRNAPro1E2 was compared with tRNAPro1 in incorporation of d-Asp, d-Glu, MeAsp and MeGlu in the absence of EF-Sep (figure 2c, red striped and blue striped bars for tRNAPro1E2 and tRNAPro1, respectively; electronic supplementary material, figure S1a). The expression levels of P1-d-Asp, P1-d-Glu, P1-MeAsp and P1-MeGlu were 0.04 µM, 0.10 µM, 0.14 µM and 0.04 µM, respectively, when using tRNAPro1E2. These values were 7.1-fold, 1.7-fold, 1.7-fold and 2.2-fold higher than those synthesized using tRNAPro1. These results indicate that the use of tRNAPro1E2 significantly improved the translation efficiency compared to the use of tRNAPro1 (p < 0.05), showing the importance of the T-stem motif of tRNAPro1E2 derived from tRNAGlu. Then, we compared the expression levels in the presence (5 µM) and absence (0 µM) of EF-Sep using tRNAPro1E2. Consequently, the expression levels of P1-d-Asp, P1-d-Glu, P1-MeAsp and P1-MeGlu were 0.07 µM, 0.16 µM, 0.18 µM and 0.06 µM, respectively, in the presence of EF-Sep, which were 1.9-fold, 1.5-fold, 1.3-fold and 1.7-fold higher than those in the absence of EF-Sep (figure 1c, red solid and striped bars for 5 µM and 0 µM EF-Sep; electronic supplementary material, figure S1a). Because the p-values for the fold changes were smaller than 0.05 for P1-d-Asp, P1-d-Glu and P1-MeGlu, we concluded that EF-Sep significantly improved the incorporation efficiencies of these amino acids. On the other hand, the enhancement of P1-MeAsp expression by EF-Sep was not statistically significant in this analysis (1.3-fold, p-value > 0.05).

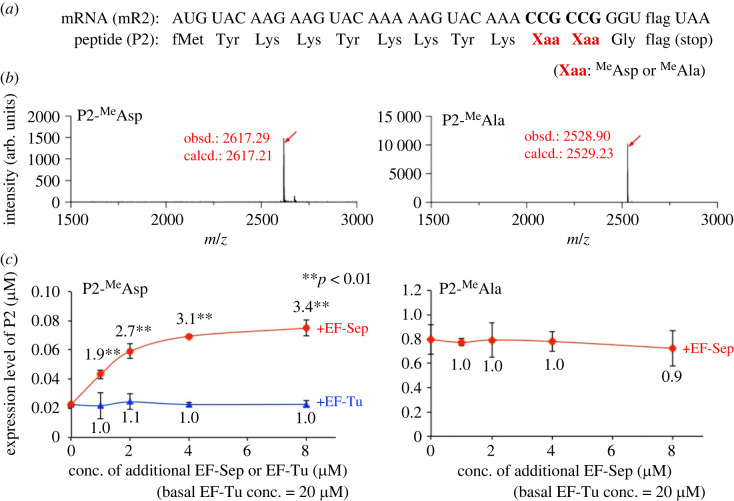

(b) . Consecutive incorporation of MeAsp into a model peptide

We assumed that the single incorporation of these amino acids is efficient enough when using tRNAPro1E2 in the presence of EF-P, and therefore we could not observe a large enhancement effect of expression levels by addition of EF-Sep, particularly in the case of MeAsp incorporation. Therefore, we next evaluated the effect of EF-Sep on consecutive ‘double’ incorporation of MeAsp into a model peptide P2 that has consecutive CCG codons (figure 3a). Since the consecutive incorporation of MeAsp requires more frequent accommodation of MeAsp-tRNA, we assumed that the enhancement effect of EF-Sep would be more clearly observed. As a comparison, incorporation of MeAla, an N-methyl-amino acid with a neutral sidechain, into P2 was also evaluated. Clean expression of P2-MeAsp and P2-MeAla was confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS in the presence of 5 µM EF-Sep (figure 3b). Then, we quantified their expression with titration of EF-Sep or EF-Tu concentration (figure 3c). The expression levels of P2-MeAsp and P2-MeAla in the absence of EF-Sep were 0.02 µM and 0.8 µM, respectively, showing less efficiency in consecutive incorporation of MeAsp than MeAla. Expression of P2-MeAsp was significantly enhanced by 1.9-fold, 2.7-fold, 3.1-fold and 3.4-fold (p < 0.01 for all values) in the presence of 1, 2, 4 and 8 µM EF-Sep, respectively, whereas that of P2-MeAla was not improved by EF-Sep. We also confirmed that addition of the same amounts of EF-Tu did not enhance the expression level of P2-MeAsp. Since the basal EF-Tu concentration is 20 µM in this system, the addition of 1, 2, 4 and 8 µM EF-Tu makes their final concentrations 21, 22, 24 and 28 µM, respectively.

Figure 3.

Consecutive incorporation of MeAsp or MeAla into a model peptide. (a) Sequences of an mRNA (mR2) and the corresponding peptide (P2). MeAsp or MeAla was introduced at the CCG codon using pre-charged aminoacyl-tRNAPro1E2CGG. (b) MALDI-TOF MS of P2-MeAsp and P2-MeAla. Translation was carried out in the presence of 5 µM EF-Sep. Red arrows indicate the monovalent ion ([M + H]+) of the desired product. ‘obsd.’ and ‘calcd.’ indicate observed and calculated m/z values, respectively. (c) Expression levels of P2-MeAsp and P2-MeAla. Translation was carried out in the presence of 0, 1, 2, 4 and 8 µM EF-Sep or EF-Tu. The basal EF-Tu concentration is 20 µM and the concentrations of additional EF-Sep and EF-Tu are indicated. Numbers indicate the ratio of the expression levels in the presence of EF-Sep or EF-Tu to those in the absence. p-values were estimated by Student's t-test and indicated by asterisks (n = 3). See the electronic supplementary material, figure S1b for the raw data of tricine SDS–PAGE. (Online version in colour.)

(c) . Ribosomal synthesis of model macrocyclic peptides containing multiple d-Asp or MeAsp

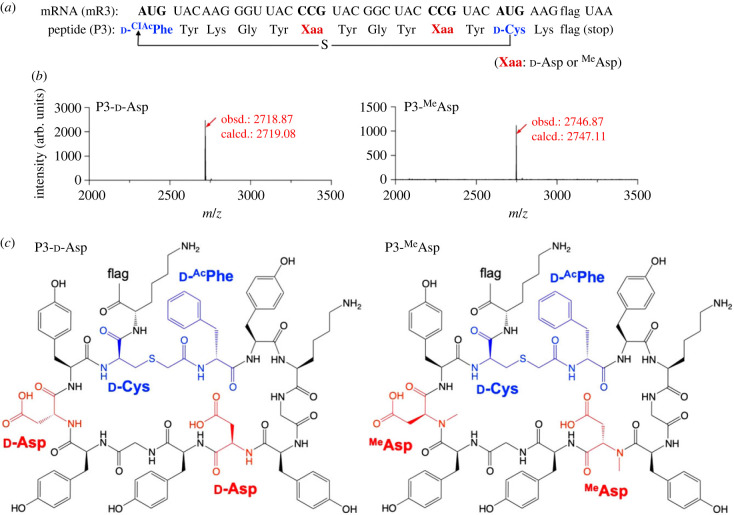

As a showcase, we next demonstrated expression of a model macrocyclic peptide, P3, containing multiple d-Asp or MeAsp in the presence of EF-Sep (figure 4a). N-chloroacetyl-d-phenylalanine (ClAcd-Phe) and d-Cys were assigned at the initiator and elongator AUG codons using pre-charged ClAcd-Phe-tRNAfMetCAU and d-Cys-tRNAPro1E2CAU, respectively. Note that Met was removed from the translation system in order to reprogramme the initiator and elongator AUG codons. The N-terminal ClAc and the downstream sulfhydryl groups of these d-amino acids spontaneously formed a thioether bond to give a macrocyclic structure [52]. Between these cyclizing residues, two d-Asp or MeAsp residues were introduced at CCG codons by using tRNAPro1E2CGG. Expression of the macrocyclic peptides containing d-Asp or MeAsp residues were confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS (figure 4b,c, P3-d-Asp and P3-MeAsp).

Figure 4.

Ribosomal synthesis of model macrocyclic peptides containing d-Asp or MeAsp. (a) Sequence of mRNA (mR3) and the corresponding peptide (P3). The thiol group of d-Cys attacks the N-terminal chloroacetyl group to form a thioether bond. (b) MALDI-TOF MS of P3-d-Asp and P3-MeAsp. Translation was carried out in the presence of 5 µM EF-Sep. d-Asp or MeAsp was introduced at the CCG codon using tRNAPro1E2CGG. ClAcd-Phe and d-Cys were introduced at the initiator and elongator AUG codons using tRNAfMetCAU and tRNAPro1E2CAU, respectively. Red arrows indicate monovalent ions ([M + H]+) of the desired peptides. ‘obsd.’ and ‘calcd.’ indicate observed and calculated m/z values, respectively. (c) Structures of P3-d-Asp and P3-MeAsp. (Online version in colour.)

4. Discussion

In this study, we showed that EF-Sep is able to promote ribosomal incorporation of dAA and MeAA with negatively charged sidechains, d-Asp, d-Glu, MeAsp and MeGlu, into model peptides. This is the first report, to the best of our knowledge, of application of EF-Sep to incorporation of these substrates. In addition, the reinforcement of the T-stem affinity of tRNA to EF-Tu/EF-Sep also contributed to enhancing their incorporation efficiency. Even though the observed enhancement of the single incorporation by EF-Sep was rather modest (approx. 2-fold), greater than 3-fold enhancement was observed for the consecutive incorporation. Since the E216N and D217G of EF-Sep were designed for improving the Sep incorporation, EF-Sep might not be yet optimal for the dAA and MeAA incorporation. Therefore, the appropriate optimization of residues in the binding pocket may further improve their incorporation efficiencies. Other EF-Tu variants, such as EF-pY and EF-Sel1, could also be applicable for the same purpose.

Our group has previously succeeded in preparation of random macrocyclic peptide libraries that have multiple dAA and/or MeAA and applied them to in vitro selection of inhibitor peptides against various target proteins by means of the RaPID (random non-standard peptides integrated discovery) system [44,53,54]. Here we have demonstrated the ribosomal synthesis of a model macrocyclic peptide bearing multiple d-Asp or MeAsp. This work adds d-Asp and MeAsp to the reprogrammed genetic code, increasing the diversity of available chemical space in macrocyclic peptides. This enables us to perform discovery campaigns of potent ligands containing d-Asp and MeAsp against protein targets of interest. Such efforts are underway in our laboratory.

Data accessibility

All the data that support the findings in this study are available within the article and the electronic supplementary material [55].

Contributor Information

Takayuki Katoh, Email: katoh@chem.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Hiroaki Suga, Email: hsuga@chem.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Authors' contributions

T.K.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, writing—original draft; H.S.: funding acquisition, supervision, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (grant no. 18H02080), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (grant no. 22H00439), Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Exploratory) (grant no. 21K18233) to T.K. and Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (grant no. 20H05618) to H.S.

References

- 1.Miller SM, Simon RJ, Ng S, Zuckermann RN, Kerr JM, Moos WH. 1995. Comparison of the proteolytic susceptibilities of homologous L-amino acid, D-amino acid, and N-substituted glycine peptide and peptoid oligomers. Drug Dev. Res. 35, 20-32. ( 10.1002/ddr.430350105) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elmquist A, Langel Ü. 2003. In vitro uptake and stability study of pVEC and its all-D analog. Biol. Chem. 384, 387-393. ( 10.1515/bc.2003.044) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen S, Gfeller D, Buth SA, Michielin O, Leiman PG, Heinis C. 2013. Improving binding affinity and stability of peptide ligands by substituting glycines with D-amino acids. Chembiochem 14, 1316-1322. ( 10.1002/cbic.201300228) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ollivaux C, Soyez D, Toullec JY. 2014. Biogenesis of D-amino acid containing peptides/proteins: where, when and how? J. Pept. Sci. 20, 595-612. ( 10.1002/psc.2637) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao YY, et al. 2016. Antimicrobial activity and stability of the D-amino acid substituted derivatives of antimicrobial peptide polybia-MPI. AMB Express 6, 1-11. ( 10.1186/s13568-016-0295-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elfgen A, et al. 2019. Metabolic resistance of the D-peptide RD2 developed for direct elimination of amyloid-β oligomers. Sci. Rep. 9, 1-13. ( 10.1038/s41598-019-41993-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conradi RA, Hilgers AR, Ho NFH, Burton PS. 1992. The influence of peptide structure on transport across Caco-2 Cells. II. Peptide bond modification which results in improved permeability. Pharm. Res. 09, 435-439. ( 10.1023/a:1015867608405) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chikhale EG, Ng KY, Burton PS, Borchardt RT. 1994. Hydrogen bonding potential as a determinant of the in vitro and in situ blood-brain barrier permeability of peptides. Pharm. Res. 11, 412-419. ( 10.1023/a:1018969222130) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haviv F, Fitzpatrick TD, Swenson RE, Nichols CJ, Mort NA, Bush EN, Diaz G, Bammert G, Nguyen A. 2002. Effect of N-methyl substitution of the peptide bonds in luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists. J. Med. Chem. 36, 363-369. ( 10.1021/jm00055a007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biron E, et al. 2008. Improving oral bioavailability of peptides by multiple N-methylation: somatostatin analogues. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 2595-2599. ( 10.1002/anie.200705797) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doedens L, Opperer F, Cai M, Beck JG, Dedek M, Palmer E, Hruby VJ, Kessler H. 2010. Multiple N-methylation of MT-II backbone amide bonds leads to melanocortin receptor subtype hMC1R selectivity: pharmacological and conformational studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 8115-8128. ( 10.1021/ja101428m) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bockus AT, Schwochert JA, Pye CR, Townsend CE, Sok V, Bednarek MA, Lokey RS. 2015. Going out on a limb: delineating the effects of β-branching, N-methylation, and side chain size on the passive permeability, solubility, and flexibility of sanguinamide A analogues. J. Med. Chem. 58, 7409-7418. ( 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00919) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Räder AFB, Reichart F, Weinmüller M, Kessler H. 2018. Improving oral bioavailability of cyclic peptides by N-methylation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 26, 2766-2773. ( 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.08.031) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh CT, O'Brien RV, Khosla C. 2013. Nonproteinogenic amino acid building blocks for nonribosomal peptide and hybrid polyketide scaffolds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 7098-7124. ( 10.1002/anie.201208344) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Süssmuth RD, Mainz A. 2017. Nonribosomal peptide synthesis-principles and prospects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 3770-3821. ( 10.1002/anie.201609079) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McIntosh JA, Donia MS, Schmidt EW. 2009. Ribosomal peptide natural products: bridging the ribosomal and nonribosomal worlds. Nat. Prod. Rep. 26, 537. ( 10.1039/b714132g) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müller MM. 2017. Post-translational modifications of protein backbones: unique functions, mechanisms, and challenges. Biochemistry 57, 177-185. ( 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00861) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dedkova LM, Fahmi NE, Golovine SY, Hecht SM. 2003. Enhanced D-amino acid incorporation into protein by modified ribosomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 6616-6617. ( 10.1021/ja035141q) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dedkova LM, Fahmi NE, Golovine SY, Hecht SM. 2006. Construction of modified ribosomes for incorporation of D-amino acids into proteins. Biochemistry 45, 15 541-15 551. ( 10.1021/bi060986a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujino T, Goto Y, Suga H, Murakami H. 2013. Reevaluation of the D-amino acid compatibility with the elongation event in translation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1830-1837. ( 10.1021/ja309570x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Achenbach J, et al. 2015. Outwitting EF-Tu and the ribosome: translation with D-amino acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 5687-5698. ( 10.1093/nar/gkv566) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katoh T, Tajima K, Suga H. 2017. Consecutive elongation of D-amino acids in translation. Cell Chem. Biol. 24, 1-9. ( 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.11.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katoh T, Iwane Y, Suga H. 2017. Logical engineering of D-arm and T-stem of tRNA that enhances D-amino acid incorporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 12 601-12 610. ( 10.1093/nar/gkx1129) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frankel A, Millward SW, Roberts RW. 2003. Encodamers: unnatural peptide oligomers encoded in RNA. Chem. Biol. 10, 1043-1050. ( 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.11.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merryman C, Green R. 2004. Transformation of aminoacyl tRNAs for the in vitro selection of ‘drug-like’ molecules. Chem. Biol. 11, 575-582. ( 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan Z, Forster AC, Blacklow SC, Cornish VW. 2004. Amino acid backbone specificity of the Escherichia coli translation machinery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 12 752-12 753. ( 10.1021/ja0472174) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawakami T, Murakami H, Suga H. 2008. Messenger RNA-programmed incorporation of multiple N-methyl-amino acids into linear and cyclic peptides. Chem. Biol. 15, 32-42. ( 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.12.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subtelny AO, Hartman MCT, Szostak JW. 2008. Ribosomal synthesis of N-methyl peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6131-6136. ( 10.1021/ja710016v) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nissen P, Kjeldgaard M, Thirup S, Polekhina G, Reshetnikova L, Clark BFC, Nyborg J. 1995. Crystal structure of the ternary complex of Phe-tRNAPhe, EF-Tu, and a GTP analog. Science 270, 1464-1472. ( 10.1126/science.270.5241.1464) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asahara H, Uhlenbeck OC. 2002. The tRNA specificity of Thermus thermophilus EF-Tu. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 3499-3504. ( 10.1073/pnas.052028599) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanderson LE, Uhlenbeck OC. 2007. Directed mutagenesis identifies amino acid residues involved in elongation factor Tu binding to yeast Phe-tRNAPhe. J. Mol. Biol. 368, 119-130. ( 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.075) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LaRiviere FJ, Wolfson AD, Uhlenbeck OC. 2001. Uniform binding of aminoacyl-tRNAs to elongation factor Tu by thermodynamic compensation. Science 294, 165-168. ( 10.1126/science.1064242) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dale T, Sanderson LE, Uhlenbeck OC. 2004. The affinity of elongation factor Tu for an aminoacyl-tRNA is modulated by the esterified amino acid. Biochemistry 43, 6159-6166. ( 10.1021/bi036290o) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asahara H, Uhlenbeck OC. 2005. Predicting the binding affinities of misacylated tRNAs for Thermus thermophilus EF-Tu·GTP. Biochemistry 44, 11 254-11 261. ( 10.1021/bi050204y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schrader JM, Chapman SJ, Uhlenbeck OC. 2011. Tuning the affinity of aminoacyl-tRNA to elongation factor Tu for optimal decoding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 5215-5220. ( 10.1073/pnas.1102128108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uhlenbeck OC, Schrader JM. 2018. Evolutionary tuning impacts the design of bacterial tRNAs for the incorporation of unnatural amino acids by ribosomes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 46, 138-145. ( 10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.07.016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanzel M, Schon A, Sprinzl M. 1994. Discrimination against misacylated tRNA by chloroplast elongation factor Tu. Eur. J. Biochem. 219, 435-439. ( 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19956.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwane Y, Kimura H, Katoh T, Suga H. 2021. Uniform affinity-tuning of N-methyl-aminoacyl-tRNAs to EF-Tu enhances their multiple incorporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 10 807-10 817. ( 10.1093/nar/gkab288) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park H-S, Hohn MJ, Umehara T, Guo L-T, Osborne EM, Benner J, Noren CJ, Rinehart J, Söll D. 2011. Expanding the genetic code of Escherichia coli with phosphoserine. Science 333, 1151-1154. ( 10.1126/science.1207203) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fan C, Ip K, Söll D. 2016. Expanding the genetic code of Escherichia coli with phosphotyrosine. FEBS Lett. 590, 3040-3047. ( 10.1002/1873-3468.12333) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haruna K, Alkazemi MH, Liu Y, Söll D, Englert M. 2014. Engineering the elongation factor Tu for efficient selenoprotein synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 9976-9983. ( 10.1093/nar/gku691) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saito H, Kourouklis D, Suga H. 2001. An in vitro evolved precursor tRNA with aminoacylation activity. EMBO J. 20, 1797-1806. ( 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1797) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murakami H, Ohta A, Ashigai H, Suga H. 2006. A highly flexible tRNA acylation method for non-natural polypeptide synthesis. Nat. Methods 3, 357-359. ( 10.1038/nmeth877) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamagishi Y, Shoji I, Miyagawa S, Kawakami T, Katoh T, Goto Y, Suga H. 2011. Natural product-like macrocyclic N-methyl-peptide inhibitors against a ubiquitin ligase uncovered from a ribosome-expressed de novo library. Chem. Biol. 18, 1562-1570. ( 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.09.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goto Y, Katoh T, Suga H. 2011. Flexizymes for genetic code reprogramming. Nat. Protoc. 6, 779-790. ( 10.1038/nprot.2011.331) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katoh T, Wohlgemuth I, Nagano M, Rodnina MV, Suga H. 2016. Essential structural elements in tRNAPro for EF-P-mediated alleviation of translation stalling. Nat. Commun. 7, 11657. ( 10.1038/ncomms11657) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katoh T, Suga H. 2018. Ribosomal incorporation of consecutive β-amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 12 159-12 167. ( 10.1021/jacs.8b07247) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katoh T, Sengoku T, Hirata K, Ogata K, Suga H. 2020. Ribosomal synthesis and de novo discovery of bioactive foldamer peptides containing cyclic β-amino acids. Nat. Chem. 12, 1081-1088. ( 10.1038/s41557-020-0525-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katoh T, Suga H. 2020. Ribosomal elongation of aminobenzoic acid derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 16 518-16 522. ( 10.1021/jacs.0c05765) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katoh T, Suga H. 2020. Ribosomal elongation of cyclic γ-amino acids using a reprogrammed genetic code. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 4965-4969. ( 10.1021/jacs.9b12280) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katoh T, Suga H. 2021. Consecutive ribosomal incorporation of α-aminoxy/α-hydrazino acids with L/D-configurations into nascent peptide chains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 18 844-18 848. ( 10.1021/jacs.1c09270) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goto Y, Ohta A, Sako Y, Yamagishi Y, Murakami H, Suga H. 2008. Reprogramming the translation initiation for the synthesis of physiologically stable cyclic peptides. ACS Chem. Biol. 3, 120-129. ( 10.1021/cb700233t) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Passioura T, Liu W, Dunkelmann D, Higuchi T, Suga H. 2018. Display selection of exotic macrocyclic peptides expressed under a radically reprogrammed 23 amino acid genetic code. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 11 551-11 555. ( 10.1021/jacs.8b03367) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Imanishi S, Katoh T, Yin Y, Yamada M, Kawai M, Suga H. 2021. In vitro selection of macrocyclic D/L-hybrid peptides against human EGFR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 5680-5684. ( 10.1021/jacs.1c02593) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katoh T, Suga H. 2023. Ribosomal incorporation of negatively charged d-α- and N-methyl-l-α-amino acids enhanced by EF-Sep. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6328851) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Katoh T, Suga H. 2023. Ribosomal incorporation of negatively charged d-α- and N-methyl-l-α-amino acids enhanced by EF-Sep. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6328851) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

All the data that support the findings in this study are available within the article and the electronic supplementary material [55].