Abstract

A novel non-invasive system has been developed to measure transdermally emitted hydrogen sulfide (H2S) from the upper and lower limbs of human subjects. The transdermal arterial gasotransmitter sensor (TAGS™) has previously been shown to detect low levels of H2S ranging between 1 and 100 ppb considered relevant for physiological measurements (Shekarriz et al. 2020). This study was designed to compare its measurement precision in detecting transdermal H2S to a commercially available chemiluminescent device, the H2S-selective Ecotech Serinus 55 TRS™. Although TAGS™ does in-situ and real-time sampling, the comparative studies in this paper collected gases emitted from the lower arm of 10 heathy human subjects between the ages of 30 and 60. Three replicate samples of each individual were collected for 30 min in a sealed 10 L Tedlar® bag to allow readings from the same sample by both devices. Readings from the TAGS™ system correlated strongly with the values obtained from the Serinus™ device, both ranging between 0.31 ppb/min and 2.21 ppb/min, with a correlation coefficient of R2 = 0.8691, p < 0.0001. These results indicate that TAGS™ measures transdermal H2S specifically and accurately. Because vascular endothelial cells are a known source of H2S, TAGS™ measurements may provide a non-invasive means of detecting endothelial dysfunction, the underlying cause of peripheral artery disease (PAD) and microvascular disease. TAGS™ has potential clinical applications such as monitoring skin vascular perfusion in individuals with suspected vascular disease or to monitor progression of wound healing during treatment, which is of particular value in diabetic patients with calcified arteries limiting detection options.

Keywords: H2S, Biosensor, Medical device, TAGS, Electrochemical

1. Introduction

In the wake of the pioneering studies of Kimura’s group [2], many questions still remain about the roles of H2S as a biologically-relevant signaling molecule [3]. H2S is a gas molecule that is twice as soluble in lipid membranes as in water, allowing it to pass through the lipid bilayer of endothelial and other cells to reach the skin [4,5]. There are several methods available to detect H2S in plasma [3,6,7], but no methods have been described to measure free H2S in human tissues without extraction (i.e. transdermal H2S) [8]. Previous studies have evaluated the utility of measuring transdermal gases in biomedical applications. These studies used gas-chromatography with mass spectrometric detection (GC–MS) coupled with solid phase microextraction (SPME) as a pre-concentrator to provide data on many volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted from the human skin [9,10]. Such measurements have provided emission ranges of many hydrocarbons, ketones, aldehydes and sulfur compounds, however, there are no data on the rate of H2S emission from human skin. Consequently, there is relatively little evidence describing changes in H2S tissue concentration under different disease and physiological states since no methods accurately measure transdermal H2S levels in real-time [3,8,11]. Knowing the normal concentration of H2S released from the skin would provide a non-invasive way to monitor tissue emission of this important signaling molecule and could potentially provide an easy and accessible way to evaluate early changes in local bioavailability of H2S by diffusion and production to signal the presence of disease.

In an effort to fill this gap in measurement methods, we developed the TAGS™ system to detect low levels of transdermal H2S (~1–100 ppb) in near real-time (i.e., < 30 s response time) [1]. Our laboratory was the first to demonstrate the ability to perform measurement of localized transdermal H2S emission in humans. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to confirm the accuracy of the TAGS™ measurements of transdermal H2S by comparing to readings made using a previously validated, commercially available, H2S-selective device Ecotech Serinus 55 TRS™. Briefly, the Ecotech Serinus 55 TRS™ device (Serinus™ device) uses pulsed fluorescence, chemiluminescence to detect H2S by passing a gas sample through an SO2 scrubber and then converting H2S to SO2 in a thermocatalytic reactor prior to measurement of SO2 concentration [12]. Compared to the TAGS™ system, the Serinus™device has a lower detection limit (< 0.3 ppb vs. 2 ppb), but requires a much larger sample for H2S detection (i.e., ≥500 mL vs. 5 mL). The ability to use a smaller sample size makes the TAGS™ system more practical for clinical point-of-care applications than the Serinus™ device. The following sections discuss the protocol to collect a single transdermal sample large enough to conduct H2S readings using both the TAGS™ system and Serinus™ device to evaluate the hypothesis that H2S measurements made by the TAGS™ system would equate to H2S measurements by the Serinus™device.

2. Methodology

2.1. Comparing standard gas measurements between the TAGS™ system and Serinus™ device

Briefly, the clear, air-tight container with a rubber needle port allowed accurate injection or removal of gases using a syringe and needle. Calibration gas dilutions were generated from certified 10 PPM H2S gas (±2%) with balance N2 (Cal Gas Direct Inc., Huntington Beach, CA). A 1.0 L FlexFoil® bag (SKC Inc., Cat. No. 252–01) was filled with the certified gas. A 5.0 mL syringe (ThermoFisher Scientific, 2S7510–1) with a 1.25-in. 27-gauge needle (BD #305136), was used to transfer the precise volume of standard gas into the 1 L sealed container using the dilution formula (Eq. 1) derived from conservation of mass for ideal gasses at isobaric and isothermal conditions to get the four different calibration concentrations.

| (1) |

C and V are concentration and volume of the gas and subscripts 1 and 2 indicate the stock gas and calibration gas, respectively. Following calibration, standard gas of a known concentration were prepared in a 1.0 L FlexFoil® bag and sensor readings of a given H2S concentration were made with both the TAGS™ system and Serinus™ device. In total, 12 different standard gas concentrations, ranging between 10 ppb and 120 ppb, were prepared and measured using both devices. FlexFoil® bags were purged of standard gas between concentration steps. Linear regression analysis was performed to determine the correlation of the readings from the two devices.

2.2. Comparing human gas measurements by the TAGS™ system and the Serinus™ device

2.2.1. Subject recruitment

10 healthy participants (no indication of cardiovascular disease) between the ages of 30 and 60 were recruited for this study. Exclusion criteria included BMI > 30 kg/m2, liver disease, kidney disease, current or past smoker, diagnosis of cancer, diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (DM). Participants were asked to fast at least 8 h prior to their appointment.

2.2.2. Data collection

Before a participant arrived for testing, the TAGS™ system and Serinus™ device were calibrated using four H2S concentrations, namely, 25 ppb, 50 ppb, 75 ppb, and 100 ppb. Prior to conducting the gas collection, participant information (i.e., height, weight, and blood pressure (BP)) were measured and recorded in order to determine whether participants were in good health. Participants with a BMI > 30 kg/m2 and a systolic blood pressure > 180 mmHg were excluded. Briefly, BP was assessed on the upper arm with clothing removed from the arm using an appropriately sized cuff while participants sat with legs uncrossed and feet flat on the floor while their back and arm supported [13].

Following the collection of participant information, gas samples from the right arm were collected into the 10 L Tedlar® Bag that was sealed to the arm using Tegaderm™ (KCI Manufacturing, REF: M6275009/10, San Antonio, TX, USA). After attachment of the bag to the arm, the bag was emptied of all gases and then filled with 2.0 L of room air. After a 30-min collection period, collected gases were transferred into 2 different 1.0 L Tedlar® bags and H2S measured within 1 h of collection by both the TAGS™ and Serinus™ devices.

2.2.3. Data analysis

The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between the two groups (TAGS™ and Serinus™) were evaluated using a paired t-test. Simple linear regression analysis was performed to evaluate the correlation of H2S measurements by the TAGS™ system with measurements made by the Serinus™device. All of the analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

There were 5 females and 5 males in the study with a mean ± SD age (years) of 42 ± 13.4. Participants recruited were in good health. BMI (kg/m2) was 25.3 ± 2.5 and systolic blood pressure was 122 ± 15.2 mmHg.

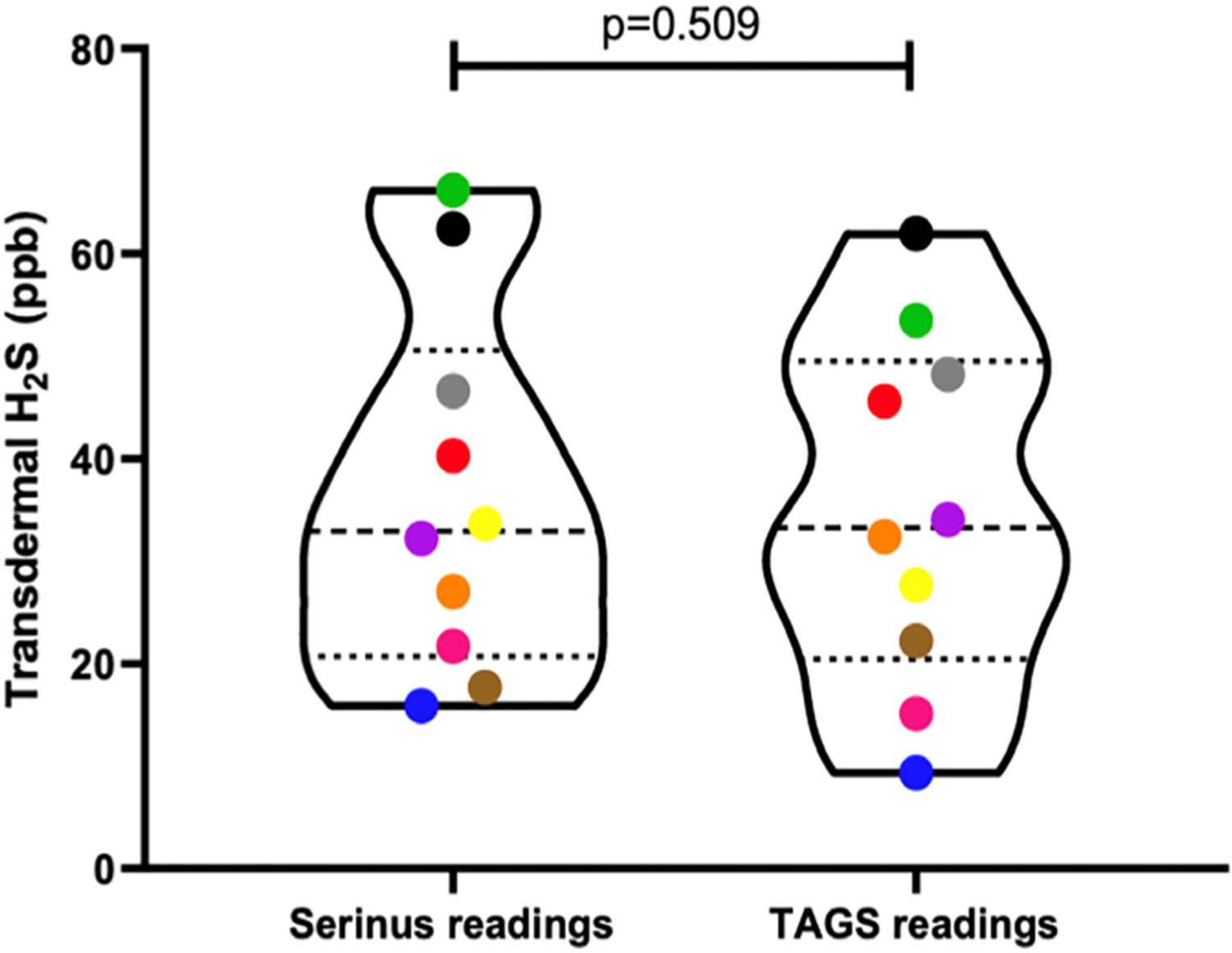

In a clinical setting, transdermal H2S gas from individuals (n = 10) were collected and then transferred into 2 different 1.0 L Tedlar® bags and measured within 1 h of collection by both the TAGS™ and Serinus™ devices. Individual H2S gas measurements were not significantly different between the two instruments, (i.e., p = 0.509, Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Violin plot of Serinus™ readings and TAGS™ readings of gas samples collected from 10 different humans analyzed via a paired t-test. No significant difference in mean values of transdermal H2S readings between the two groups (p = 0.509). Each individual is represented by a different colour.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patient population. Values are shown as mean ± SD.

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Male/female | (5/5), 10 |

| Age (yrs) | 42 ± 13.4 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 122 ± 15.2 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.3 ± 2.5 |

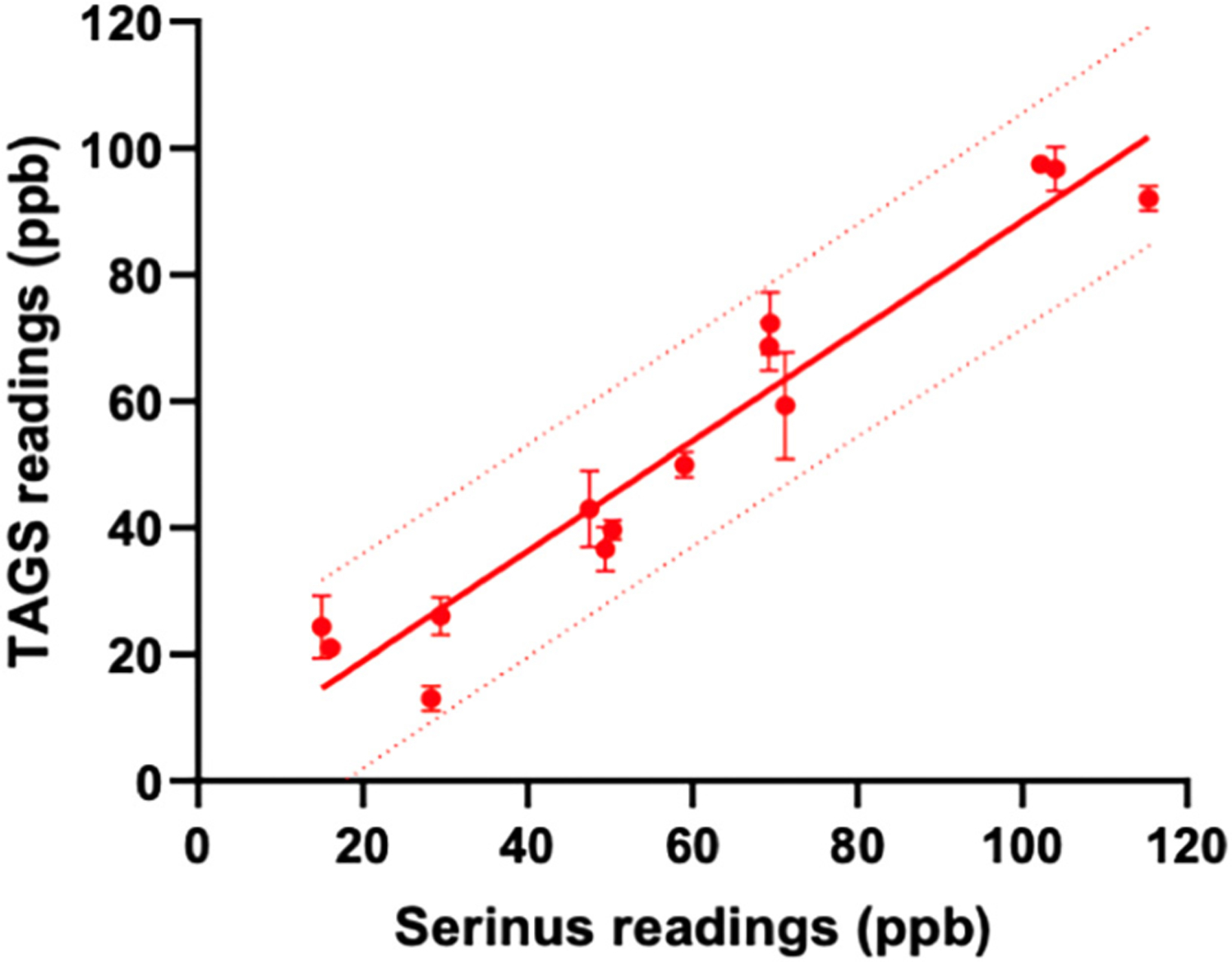

Simple linear regression analysis was also used to compare device readings using H2S standard gas as described in the previous sections. There was a statistically significant correlation between the TAGS™ and Serinus™ readings (i.e., R2 = 0.9189, p < 0.0001, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Regression lines for TAGS™ readings (ppb) and Serinus™ readings (ppb) of 14 samples. There is strong significant correlation between TAGS™ readings and Serinus™ readings (R2 = 0.9189, p < 0.0001). Device readings using varying concentrations of standard gas are represented by a red point. The solid red line is the linear regression line representing the goodness of fit between these two variables. The dotted red line represents the 95% prediction bands of the best-fit line testing standard gas.

Furthermore, the slope of linear regression line (y = x + 2.0) demonstrates that the H2S samples measured in each device is in a 1:1 ppb ratio with only a 2-ppb offset.

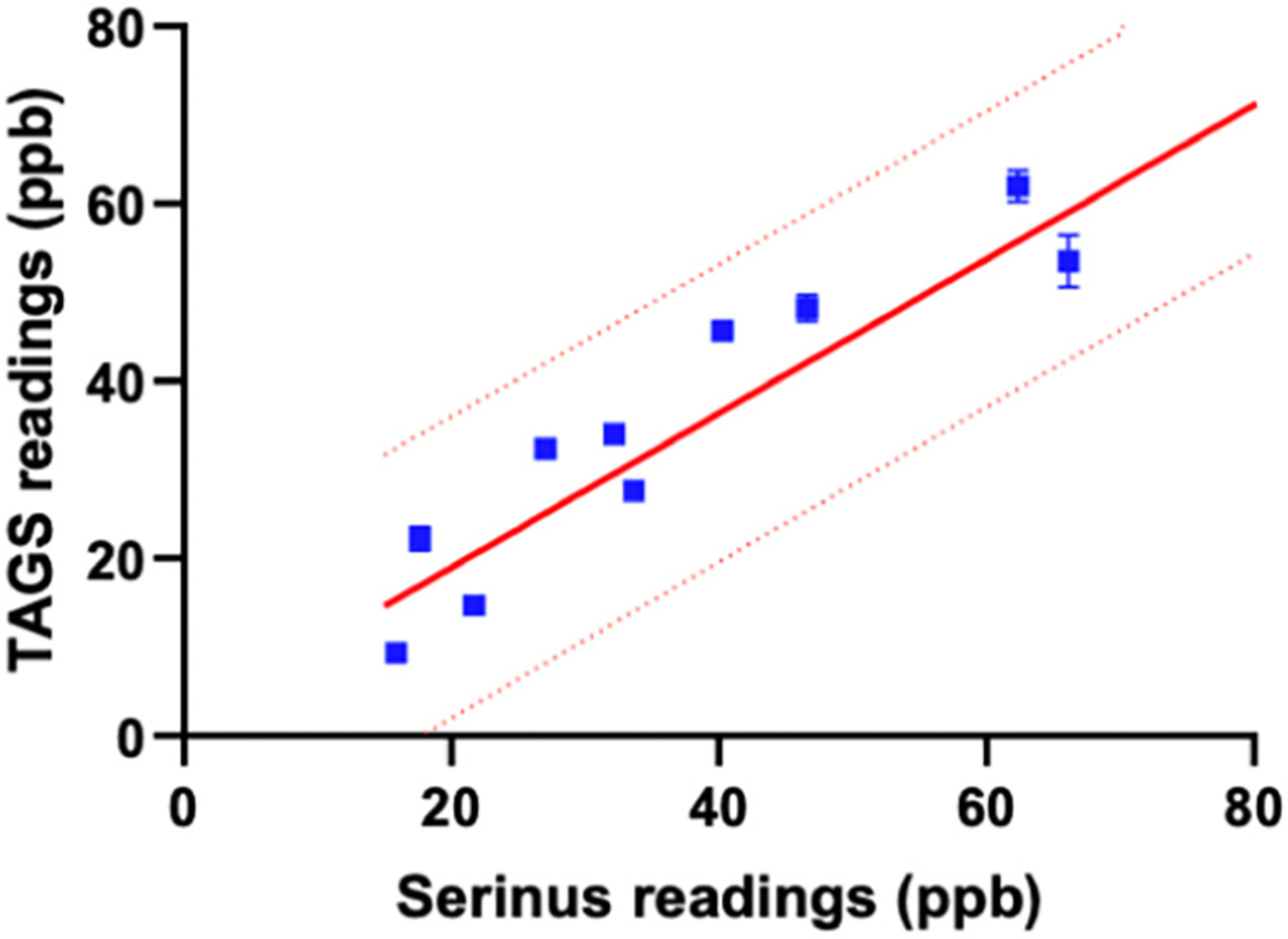

Lastly, to assess the correlation of transdermal H2S measurements between the two devices, linear regression analysis was performed on the readings from 10 human samples. TAGS™ readings significantly correlated with the transdermal H2S measurements from the Serinus™ device (i.e., R2 = 0.8691, p < 0.0001, Fig. 3). All 10 human gas samples fell within the 95% prediction bands of the best-fit line analyzed using standard gas measurements, demonstrating the level of accuracy of the TAGS™ system to measure transdermal H2S in humans.

Fig. 3.

Relationship between TAGS™ readings (ppb) and Serinus™ readings (ppb) of 10 human gas samples analyzed via linear regression analysis. Device readings using collected human gas samples are represented by a blue point. The solid red line is the linear regression line comparing the two device readings using calibration gas. The dotted red line represents the 95% prediction bands of the best-fit line testing calibration gas. All human gas samples fit within the 95% prediction bands.

4. Conclusion

The data from this study demonstrate that the TAGS™ system can accurately measure transdermal H2S emissions from healthy humans. The strong correlation between transdermal H2S measurements made using the Serinus™ device to readings made with the TAGS™ system demonstrate that the TAGS™ system is superior to the larger, bulkier and more expensive Serinus™ device for potential clinical applications. Furthermore, the similarity of the readings between the two systems demonstrates that the TAGS™ system accurately measures H2S released through the skin of healthy humans. This study showed that the TAGS™ system is an appropriate tool to further evaluate the generation of H2S in subcutaneous tissues. Since the endothelium of the microcirculation generates H2S in humans [14], changes in TAGS™ readings is likely to reflect changes in the health of the underlying tissue. Importantly, these data demonstrate that the electrocatalytic sensing approach engineered into the TAGS™ system detects physiological H2S levels in a sample size that is 10 to 100 times smaller than that of the fluorescent spectroscopy approach engineered in the Serinus™ device and which is currently not available in any other device.

From multiple target clinical applications of accurately sensing transdermal H2S, one possible application would be to evaluate decreases in transdermal H2S as an early indicator of vascular endothelial disease. Previous work has reported that diabetes [15], hypertension and atherosclerosis [14,16] decrease H2S levels in human subjects, while animal studies demonstrate that H2S protects the vasculature from developing endothelial disease [17–19]. Thus, non-invasive and accurate measures of this endothelium-derived vasodilator may serve as an early indicator of endothelial dysfunction. Therefore, the validation of the TAGS™ system represents a major enabling step toward rapid, sensitive detection of this biomarker during routine heath visits as a potential diagnostic technique to identify early stage microvascular disease. Further studies are warranted to investigate the relationship between the plasma H2S levels, microvascular health and transdermal H2S levels.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Reza Shekarriz reports a relationship with Exhalix, LLC that includes: equity or stocks. Reza Shekarriz has patent Transdermal Sampling Strip and Method for Analyzing Transdermally Emitted Gases issued to Patent US 10,856,790, 8 December 2020. D.M. Friedrichsen, corresponding author contracted for work by Exhalix, LLC B.J. Brooks, corresponding author contracted for work by Exhalix, LLC. The authors would like to acknowledge the funding provided by the NHLBI SBIR grants HL121871-1 thru-03.

References

- [1].Shekarriz R, Friedrichsen DM, Brooks B, et al. , Sensor of transdermal biomarkers for blood perfusion monitoring, Sens Bio-Sensing Res. 28 (January) (2020), 100328, 10.1016/j.sbsr.2020.100328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Abe K, Kimura H, The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator, J. Neurosci 16 (3) (1996) 1066–1071, 10.1523/jneurosci.16-03-01066.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Olson KR, Is hydrogen sulfide a circulating “gasotransmitter” in vertebrate blood? Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg 1787 (7) (2009) 856–863, 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cuevasanta E, Denicola A, Alvarez B, Möller MN, Solubility and permeation of hydrogen sulfide in lipid membranes, PLoS One 7 (4) (2012) 3–8, 10.1371/journal.pone.0034562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Missner A, Pohl P, 110 years of the Meyer-Overton rule: predicting membrane permeability of gases and other small compounds, ChemPhysChem. 10 (9–10) (2009) 1405–1414, 10.1002/cphc.200900270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wintner EA, Deckwerth TL, Langston W, et al. , A monobromobimane-based assay to measure the pharmacokinetic profile of reactive sulphide species in blood, Br. J. Pharmacol 160 (4) (2010) 941–957, 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Shen X, Pattillo CB, Pardue S, Bir SC, Wang R, Kevil CG, Measurement of plasma hydrogen sulfide in vivo and in vitro, Free Radic. Biol. Med 50 (9) (2011) 1021–1031, 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Olson KR, A practical look at the chemistry and biology of hydrogen sulfide, Antioxid. Redox Signal 17 (1) (2012) 32–44, 10.1089/ars.2011.4401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Agapiou A, Amann A, Mochalski P, Statheropoulos M, Thomas CLP, Trace detection of endogenous human volatile organic compounds for search, rescue and emergency applications, TrAC - Trends Anal Chem. 66 (2015) 158–175, 10.1016/j.trac.2014.11.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mochalski P, King J, Haas M, Unterkofler K, Amann A, Mayer G, Blood and breath profiles of volatile organic compounds in patients with end-stage renal disease, BMC Nephrol. 15 (2014) 43, 10.1186/1471-2369-15-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Olson KR, The therapeutic potential of hydrogen sulfide: separating hype from hope, Am. J. Phys. Regul. Integr. Comp. Phys 301 (2) (2011), 10.1152/ajpregu.00045.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].EcoTech - Enviornmental Monitoring Solutions, Serinus 55 User Manual 1.0, 2010.

- [13].Muntner P, Shimbo D, Carey RM, et al. , Measurement of Blood Pressure in Humans: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Vol 73, 2019, 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kutz JL, Greaney JL, Santhanam L, Alexander LM, Evidence for a functional vasodilatatory role for hydrogen sulphide in the human cutaneous microvasculature, J. Physiol 593 (9) (2015) 2121–2129, 10.1113/JP270054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sunzini F, De Stefano S, Chimenti MS, Melino S, Hydrogen sulfide as potential regulatory gasotransmitter in arthritic diseases, Int. J. Mol. Sci 21 (4) (2020), 10.3390/ijms21041180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Irving RJ, Walker BR, Noon JP, Watt GCM, Webb DJ, Shore AC, Microvascular correlates of blood pressure, plasma glucose, and insulin resistance in health, Cardiovasc. Res 53 (1) (2002) 271–276, 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Altaany Z, Moccia F, Munaron L, Mancardi D, Wang R, Hydrogen sulfide and endothelial dysfunction: relationship with nitric oxide, Curr. Med. Chem 21 (32) (2014) 3646–3661, 10.2174/0929867321666140706142930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hadi HAR, Al Suwaidi JA, Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus, Vasc. Health Risk Manag 3 (6) (2007) 853–876. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Greaney JL, Kutz JL, Shank SW, Jandu S, Santhanam L, Alexander LM, Impaired hydrogen sulfide-mediated vasodilation contributes to microvascular endothelial dysfunction in hypertensive adults, Hypertension. 69 (5) (2017) 902–909, 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]