Abstract

Two male patients aged above 70 years were investigated for chronic non-specific symptoms and evidence of significant systemic inflammation, but without classic ‘cranial symptoms’ of giant cell arteritis (GCA). Each patient had multiple non-diagnostic investigations, but finally extensive large-vessel vasculitis was revealed by whole body positron emission tomography/CT imaging. Both cases were confirmed to have GCA on temporal artery biopsy and responded well to initial high-dose prednisolone therapy. The patients successfully completed 12 months of steroid-sparing therapy with tocilizumab and achieved remission of their condition.

Keywords: Immunology, Geriatric medicine, General practice / family medicine, Vasculitis, Medical education

Background

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a well-recognised cause of large-vessel vasculitis (LVV), which classically manifests in the elderly with cranial symptoms of headache, visual disturbances and jaw claudication. Studies have revealed that 1.4%–1.7% of patients have solitary extracranial involvement with low positive results on gold standard temporal artery biopsies (TAB) and 22% demonstrated acephalic symptomatology leading to diagnostic challenges and treatment delays.1–5 Here, we present a case series of patients with atypical GCA diagnosed with whole body positron emission tomography (PET) imaging.

Case 1

A Caucasian man in his early 70s presented with a 3-month history of lethargy, night sweats, subjective fevers, modest weight loss of 2 kg, nocturia and urgency. The patient reported an initial 4-day history of generalised non-pulsating headaches and painless jaw ‘weakness’, which resolved spontaneously without treatment. He denied any symptoms of jaw claudication, visual disturbance or temporal muscle pain, and no characteristic features of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR).

Initial investigations demonstrated raised inflammatory markers with a C reactive protein (CRP) of 94.8 mg/L and Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 94 mm/hour. Full blood examination revealed mild normocytic normochromic anaemia (Hemoglobin 108 g/L) with normal haematinic screen. Results on autoimmune serology, HIV testing, serum free light chains, blood cultures and urinalysis were non-diagnostic.

There was evidence of mild prostatomegaly on whole-body CT imaging. He was further evaluated with an MRI prostate which demonstrated acute on chronic inflammatory changes suggestive of possible prostatitis.

A presumptive diagnosis of chronic prostatitis was made, and consequently, he was commenced on a 12-week course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg two times per day orally. Unfortunately, following completion of antibiotic therapy, there was no observable improvement in his condition with persistence of raised inflammatory markers (CRP 62.8 mg/L, ESR 83 mm/hour) and new symptoms of mid-thoracic and cervical back pain. Repeat physical examination revealed no focal neurological deficits or spinal tenderness.

Given the negligible response to antibiotic therapy, a non-infective inflammatory process was considered. Differentials included occult malignancy and LVV. Whole-body FDG(Fluorodeoxyglucose)-18 PET imaging subsequently revealed evidence of extensive LVV (figure 1). A TAB was performed with histological confirmation of GCA.

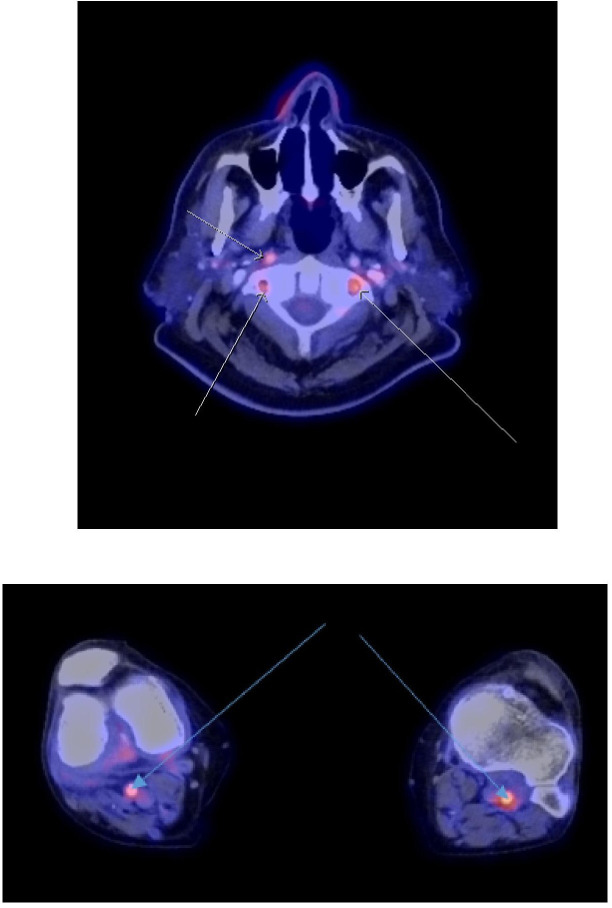

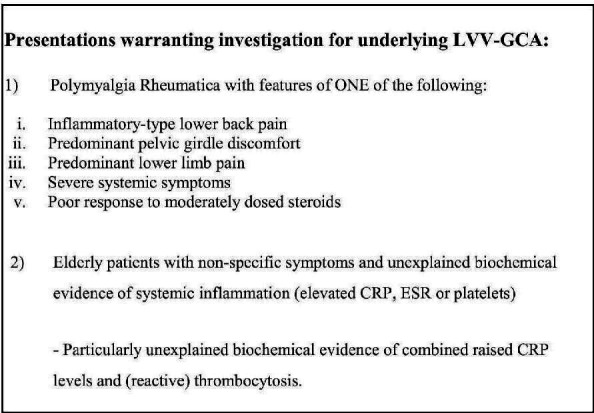

Figure 1.

(A–C) revealed intense FDG avidity involving the thoracic aorta, abdominal aorta, bilateral iliac and popliteal arteries. FDG, Fluorodeoxyglucose.

Treatment with high-dose prednisolone (1 mg/kg daily orally) resulted in rapid clinical improvement and complete normalisation of the inflammatory markers. Within 5 weeks from the diagnosis, he was commenced on steroid-sparing therapy with a 12-month course of weekly tocilizumab (162 mg/0.9 mL) injections and maintenance leflunomide 10 mg orally, while receiving 3 monthly outpatient clinic follow ups. Over a 7-month period, he was weaned down and established on a prednisolone dose of 5 mg. At 16 months post-GCA diagnosis, he remained in clinical remission with no further relapses.

Case 2

An elderly man in his late 70s had multiple hospital admissions over 6 months due to recurrent syncope with falls. Further history revealed severe fatigue, 6 kg weight loss and progressive functional impairment requiring wheelchair assistance. There was no clinical history otherwise to suggest a diagnosis of temporal arteritis or PMR. The patient had a significant history of stage 1 prostate cancer, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and chronic back pain secondary to lumbar canal stenosis.

On initial presentation, there was evidence of significant symptomatic postural hypotension (120/85 mm Hg supine, 75/50 mm Hg erect), with no compensatory tachycardic response. His cardiorespiratory examination was otherwise normal. There was no evidence of focal neurological deficit, parkinsonism or gait disorder.

Initial investigations including blood tests, chest X-ray, CT abdominal/pelvic imaging, colonoscopy and endoscopy revealed normocytic normochromic anaemia (Hb 88 g/L), raised inflammatory markers (CRP 92–150 mg/L) and chronic renal impairment presumed secondary to hypertension (creatinine 130–150 mmol/L). Thyroid function tests and morning cortisol levels were normal. Iron studies were consistent with iron deficiency and concomitant chronic inflammation. There was no evidence of occult malignancy on imaging, although there were findings of reactive intra-abdominal and pelvic lymphadenopathy of unclear significance.

His postural hypotension was non-responsive to treatment with iron and blood transfusions, cessation of blood pressure lowering medications, intravenous hydration and medical therapy with midodrine and fludrocortisone. His inflammatory markers (CRP >100 mg/L) remained persistently elevated with no improvement in constitutional symptoms.

Whole-body PET imaging was arranged to rule out the differentials of occult malignancy with paraneoplastic phenomena and ‘silent’ vasculitis. The PET findings were consistent with mixed medium and LVV (figure 2). Days following completion of the PET CT, the patient was diagnosed with bilateral anterior optic ischaemia. Prompt amelioration of visual disturbances and postural hypotension was noted after administration of intravenous methyl-prednisolone (500 mg daily for 3 days). Histology of a TAB confirmed GCA.

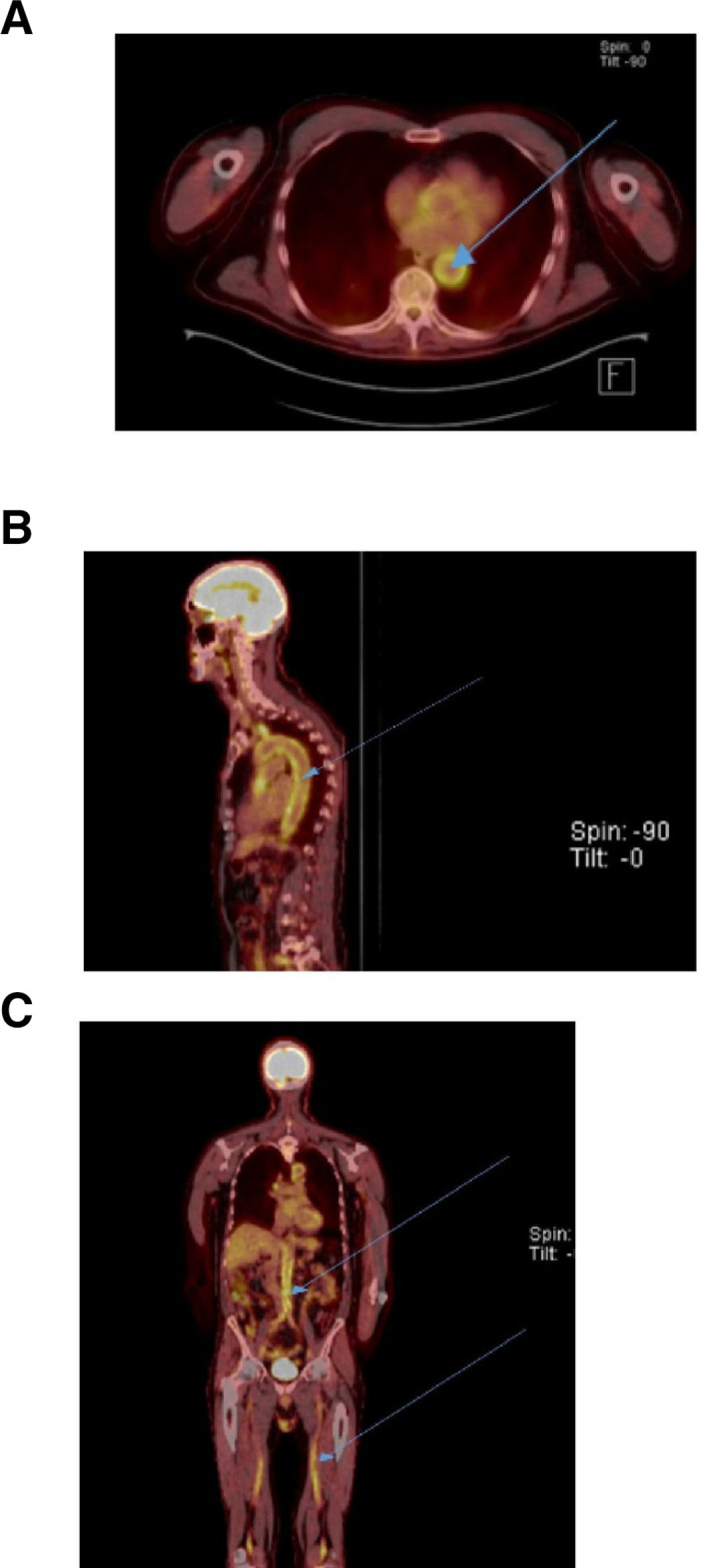

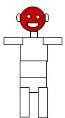

Figure 2.

Moderately intense FDG avidity involving the bilateral vertebral, right carotid and bilateral popliteal arteries. FDG, Fluorodeoxyglucose

The patient commenced 70 mg prednisolone orally with monthly outpatient clinic follow-up. He completed 12 months of tocilizumab therapy with only two mild flares of GCA reported over the last 2 years. Currently, he remains in clinical remission on 8 mg oral prednisolone with no active symptoms and normal inflammatory markers (CRP 4.4 mg/L, ESR 8 mm/hour).

Discussion

GCA is a non-necrotising granulomatous mixed large and medium vessel vasculitis, which primarily affects those aged 50 and over. This classically manifests with symptoms of temporal muscle tenderness, headache, jaw claudication and visual impairment. Abnormal blood tests generally reveal non-specific findings of anaemia and elevated inflammatory markers (CRP, ESR). TAB remains the gold standard investigation for diagnosis with a sensitivity of 15%–40% and specificity of 100%. Over time, there has been increasing recognition of extracranial arterial involvement in GCA, including cases with isolated extracranial syndromes. These patients pose significant diagnostic challenges due to the absence of specific clinical features, low yield of positive TAB and inability to satisfy standardised criteria for GCA (eg, European Congress of Rheumatology (EULAR) criteria and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria).1–5

LVV-predominant GCA demonstrates a rather diverse array of manifestations that differs to that of cranial GCA. González-Gay et al further define these by subdividing the condition into three categories of clinical presentation: (1) atypical PMR, (2) constitutional syndrome (fatigue, weight loss) and (3) fever of unknown origin. Interestingly compared with cranial GCA, it was also observed that patients with LVV-GCA demonstrated features of younger age onset (<70 years) and milder elevations of inflammatory markers. Based on these observations, an algorithm was developed to facilitate early diagnosis of LVV-GCA of which recommendations were made to order PET CT or MR/CT angiography in patients aged 50–70 years presenting with 1 out the 3 above-mentioned clinical presentation types and raised inflammatory markers±ischaemic symptomatology.6

Atypical presentations of GCA can also present with undifferentiated constitutional symptoms (pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO), fatigue, weight loss) and organ-related ischaemia or inflammatory disorders including mucocutaneous (lingual and scalp necrosis, panniculitis),7–12 neurological (mononeuritis multiplex, cerebral vasculitis, cranial nerve palsies, acute stroke),13–17 ocular (uveitis, choroidal infarction),18–21 musculoskeletal (peripheral joint arthritis, focal myositis)22–24 and inflammatory pseudotumour (skin, uterine, breast),25–28 along with orchitis, myocardial infarction and mesenteric ischaemia.29–32

Delayed establishment of diagnosis can result in serious vascular complications eg. aortic aneurysms and vascular dissections.33–36

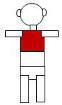

Approximately 10%–20% of cases are associated with PMR, another immune-mediated disorder that classically manifests with proximal joint stiffness, constitutional symptoms (weight loss, fatigue, fevers) and pronounced response to oral steroids.37 38 PMR patients with atypical features, which include inflammatory-type lower back pain, predominant pelvic girdle discomfort or lower limb pain, severe systemic symptoms and poor response to moderately dosed steroids, were more likely to have concurrent LVV and therefore should be investigated as such.39 One study recommended screening for LVV in all elderly patients with non-specific symptoms and biochemical evidence of systemic inflammation (elevated CRP, ESR or platelets).40 An extension of this concept was also depicted by Chan et al in a retrospective audit, which suggested that the combination of high CRP and thrombocytosis demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for GCA and possibly a better diagnostic yield for the condition than isolated elevations in CRP or ESR (figure 3).41

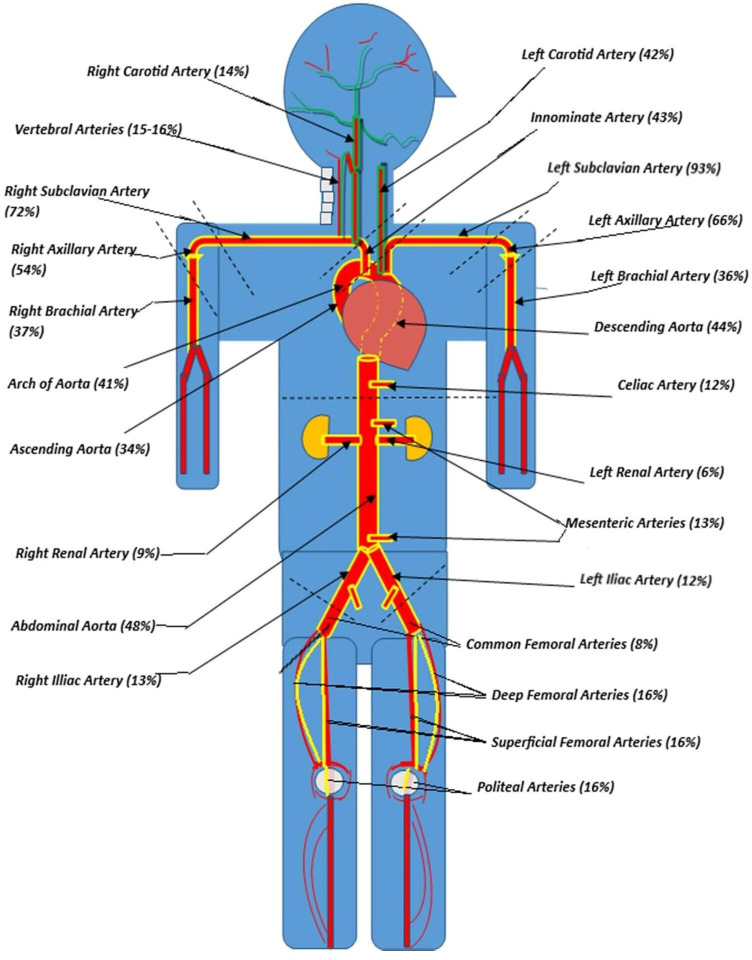

Figure 3.

The following delineates the presentations requiring exclusion of underlying LVV-GCA. CRP, C reactive protein; GCA, giant cell arteritis; LVV, large-vessel vasculitis; ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

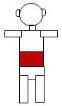

Physician-driven assessments are often limited to ‘cranial’ symptoms, with a tendency to overlook potential involvement of extracranial vascular territories (figure 4). Several sources have proposed for these patients to undergo complete examinations of all peripheral arteries (including temporal arteries) and cardiovascular system with attention to clinical signs of decreased upper limb pulses, blood pressure and pulse discrepancies, auscultatory findings of aortic regurgitant murmurs and vascular bruits. The clinical history should also define the absence or presence of limb claudication.35 42 43

Figure 4.

Prevalence of artery involvement in GCA. The vascular territories involved in cranial and LVV-GCA are outlined in ‘green’ and ‘yellow’, respectively. Subclavian and axillary arteries predominate the major extracranial arteries in GCA, while the renal, mesenteric and lower limb vascular territories were the least involved. GCA, giant cell arteritis; LVV, large-vessel vasculitis.

It is worth noting that GCA is defined as a systemic inflammatory condition involving both large-sized and medium-sized vessels. Indeed, several of the lesser recognised GCA-related symptoms (eg, skin necrosis, digital gangrene, mesenteric ischaemia, orchitis, prostatitis) mirror presentations of the primary medium-vessel vasculitides, polyarteritis nodosa.44–47 Hence, it is appropriate to assess for organ-specific signs and symptoms of medium-vessel vasculitis including a dedicated examination of the integumentary system, mucous membranes, peripheral nerves, abdomen, perineum and cardiorespiratory systems (table 1).

Table 1.

Review of systems in GCA with interpretation of findings

| System | Presentation | Pathophysiology | Medium-sized artery involved | Large-sized artery of origin | Imaging modality to consider |

| Systems review of GCA with interpretation of findings cranial GCA | |||||

Head/scalp

|

Scalp necrosis | Cutaneous ischaemia to: (1) frontal, superior and temporal regions of scalp | Superficial temporal arterial branch of ICA Occipital arterial branch of ICA |

Common carotid artery | Temporal artery±axillary arteries US If conclusive, MRA cranial arteries |

| (2) Posterior auricular region of scalp | Posterior auricular branch of ECA | ||||

| (3) Posterior region of scalp | Occipital Arterial branch of ICA | ||||

| Facial pain | Ischaemia to the fifth cranial nerve | Epineural Arteries of ICA and ECA | |||

Oral

|

Lingual necrosis | Ischaemia to tongue | Lingual Arterial branch of ECA | ||

| Lip necrosis | Ischaemia to lip | Labial arterial branch of facial artery | |||

| Jaw claudication | Ischaemia to masseter muscles | Maxillary arterial branch of ECA | |||

Upper respiratory tract

|

Sore throat | Ischaemia to pharyngeal tissue | Ascending pharyngeal arterial branch of ECA | ||

| Cough | Irritation of cough receptors (cough reflex pathway) adjacent to inflamed tissue | Ascending pharyngeal arterial branch of ECA | |||

Ophthalmological

|

Visual impairment |

|

Ophthalmic arterial branches of ICA | ||

| Diplopia | Ocular motor palsies secondary to ischaemia of third, fourth or sixth cranial nerve | Epineural arteries derived from ICA, ECA and VBA | Common carotid and subclavian artery | ||

Auditory

|

Deafness, vertigo or tinnitus | Ischaemia of eighth cranial nerve | Epineural arteries derived from VBA and ECA | Subclavian and common carotid artery | |

Neurological

|

Focal neurological deficits from acute stroke | Cerebral infarction | VBA (most common) | Subclavian artery | |

| ICA (uncommon) | Common carotid artery | ||||

| Stroke-like syndrome, encephalopathy headache | Cerebral vasculitis | Cranial arteries of ICA±VBA | Subclavian and common carotid artery | ||

| LVV-GCA | |||||

Neck

|

Unilateral neck swelling, carotidynia | Inflammation of common carotid | Nil | Common carotid artery±arch of aorta |

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of thoracic vasculature or FDG-18 (Fluorodeoxyglucose 18) PET CT |

Cardiovascular

|

Angina ischaemic ECG changes |

Myocardial ischaemia/infarction Rarely, myopericarditis |

Coronary arteries | Nil | |

| Dyspnoea | Aortic insufficiency secondary to inflammation of the aortic root | Nil | Ascending aorta | ||

| Upper back pain | Thoracic aortitis | Nil | Thoracic aorta | ||

Upper limbs

|

Upper limb claudication Vascular bruit. Differential pulse between arms >10 mm Hg |

Subclavian artery stenosis with inducible ischaemia of upper limb | Nil | Subclavian artery±arch of aorta | |

| ‘Glove’ distribution pain Wrist drop. |

Ischaemia to the peripheral nerves. | Epineural branches of upper limb arteries | Subclavian artery | ||

Abdomen

|

Lower back pain or abdominal pain Abdominal bruit Pulsatile mass |

Abdominal aortitis±aneurysm, dissection | Nil | Abdominal aorta | MRA of abdominal vasculature or FDG-18 PET CT |

| Postprandial abdominal pain | Mesenteric ischaemia±bowel infarction | Mesenteric arteries | |||

Perineum

|

Testicular pain/swelling | Orchitis secondary ischaemia and inflammation of testicular tissue | Testicular Artery | MRA of abdominal vasculature or FDG-18 PET CT |

|

| Rectal pain Dysuria |

Prostatitis secondary ischaemia and inflammation of prostatic tissue | Internal pudendal arterial branch of internal iliac artery | Common iliac artery | ||

Lower limbs

|

Lower limb claudication—pain in thigh or buttocks on movement | Lower limb large-vessel vasculitis with inducible ischaemia. | Nil | Lower abdominal Aorta/common Iliac Arteries | MRA of lower limb extremities or FDG-18 PET CT |

| Leg ulcers | Dermal or subcutis ischaemia of lower limbs | Cutaneous arterial branches of lower limb arteries | Common iliac artery | ||

| ‘Stocking’ distribution pain. Foot drop. | Ischaemia to the peripheral nerves | Epineural branches of lower limb arteries | |||

ECA, external carotid artery; GCA, giant cell arteritis; ICA, internal carotid artery; PET, positron emission tomography; VBA, vertebrobasilar arterial system.

Abnormal haemodynamic changes including bradycardia and orthostatic hypotension have been reported in cases of LVV. Orthostatic hypotension appears to be an extremely rare manifestation of GCA, with only one other case report noted. It was suggested that immune-complex mediated injury to the central catecholamine neuron system could have been responsible for this presentation.48 49 Another case report of a patient with GCA complicated by syncope and inducible asystole proposed that carotid hypersensitivity syndrome was the causative factor.50 This novel theory, however, was contradicted by contrary findings of baroreflex failure in a study conducted on patients with Takayasu’s disease.51 Another potential explanation for the above-mentioned haemodynamic changes includes the possibility of an isolated ischaemic or inflammatory injury to either the afferent baroreflex input (with preservation of efferent parasympathetic function) or sympathetic adrenergic neuronal structures, which neighbour involved vascular territories, causing selective baroreflex failure or autonomic dysfunction, respectively.52–59 Attention to abnormal vital signs, especially in the setting of a systemic inflammatory response, may not only drive clinical suspicion of LVV-GCA but also provide clues to the location of the involved extracranial arteries (eg, orthostatic hypotension secondary to possible thoracic aortitis with resultant ganglionopathy).

Employment of multiple imaging modalities such as MRI or whole-body PET scans in conjunction with a strong clinical suspicion can aid in the early diagnosis of LVV-GCA, revealing both structural and functional changes associated with active LVV. Studies have demonstrated temporal artery ultrasounds to be highly specific and sensitive in the diagnosis of cranial GCA (87% and 96%, respectively).60 61 However, this modality is highly technician dependent and may not be particularly useful in diagnosing extracranial GCA given that 50% of cases have a negative TAB.62–64 High-resolution MRI has proven utility in the evaluation of both cranial and extracranial GCA involving the aortic arch and its branches.65–68 However, its usefulness is limited by high cost, limited availability, higher incidence of patient contraindications and lack of supportive studies.69 Furthermore, the diagnostic yield in patients with cranial GCA appears non-superior to that of temporal artery ultrasound.70 Whole body FDG-PET imaging has demonstrated value to evaluating multivascular territories in extracranial GCA. Its limitations revolve around high cost, lack of accessibility and restricted ability to denote inflammatory changes in cranial arteries (hence not indicated in the diagnosis of cranial GCA).71 72 Utilisation of these investigations, depending on the clinical history, can identify or exclude LVV with high accuracy without the need for tissue biopsy and histological diagnosis.73

Utilisation of FDG-PET CT scanning in the diagnostic workup of LVV in PMR without GCA-related cranial symptomatology has been well acknowledged. Furthermore, its use has allowed us to enhance our understanding of this condition and its clinical presentations. González-Gay MA et al conducted a retrospective study with the distinct purpose of identifying the clinical predictive factors for PET positivity for LVV in patients with PMR. Patients who had cranial manifestations of GCA or did not satisfy the ACR/EULAR criteria of PMR, were excluded from the study. Data was collected over a period of 2 years via a single healthcare centre. In the PET positive group, an array of atypical symptoms was identified of which the best set of predictors for LVV included bilateral diffuse lower limb pain (OR 8.8, 95% CI 1.7 to 4.3, p<0.0001), pelvic girdle pain and lower back pain.73

The utility of PET imaging in the diagnosis of GCA has been well documented in other studies. In the GAPS study, a prospective, double-blinded, cross-sectional study evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of head, neck and chest PET/CT imaging for GCA demonstrated that PET/CT scans diagnosed GCA with a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 85% compared with TAB, thereby highlighting its high diagnostic accuracy. The results of this study also revealed a negative predictive value of 98%, which demonstrates the usefulness of PET imaging in excluding GCA in those with low-diagnostic probability for the condition.74 Gildberg-Mortensen et al denoted the diagnosis of underlying LVV using whole body PET imaging in a small cohort of 22 patients who presented with either clinical GCA, presumed PMR or non-specific symptoms of inflammation (fever, fatigue, high ESR). In this cohort, 82% had positive TAB and vascular inflammation on PET imaging concurrently. These results depict the utility of this imaging modality in diagnosing or excluding GCA in an array of medical presentations and show the strong concordance of positive PET findings with positive TABs.75 In support of these outcomes, a 2020 prospective, observational, cross-sectional study by Emamifar et al revealed a high level of concordance between 18F-FDG-PET scan, clinical diagnosis and TAB in patients with PMR and GCA (75% and 93%, respectively).76 PET/CT scans have also been identified as a useful investigation for diagnosing LVV in patients with negative TAB. As demonstrated by a 2019 retrospective study, 35% (22 out of 63) of patients with suspected GCA, but negative TAB, had confirmed a diagnosis of LVV via FDG PET imaging. Many of the patients were treated with corticosteroids, which did not seem to impact significantly on its diagnostic accuracy.77 Other studies also support the reliability of FDG-PET/CT scans in suspected cases who have been commenced on high-dose steroids, although the sensitivity appears to diminish when the duration of treatment exceeds greater than 3 days (figure 5).78 79 Though this investigatory tool is restricted to diagnosing suspected extracranial LVV, there are limited studies evaluating the incorporation of visual and semiquantitative assessments of localised FDG uptake such as measurement of maximum standard unit value into PET imaging to facilitate delineation of cranial artery inflammation.80 81 At present, however, temporal artery ultrasonography remains the mainstay imaging modality of choice for cranial GCA.69 82–87

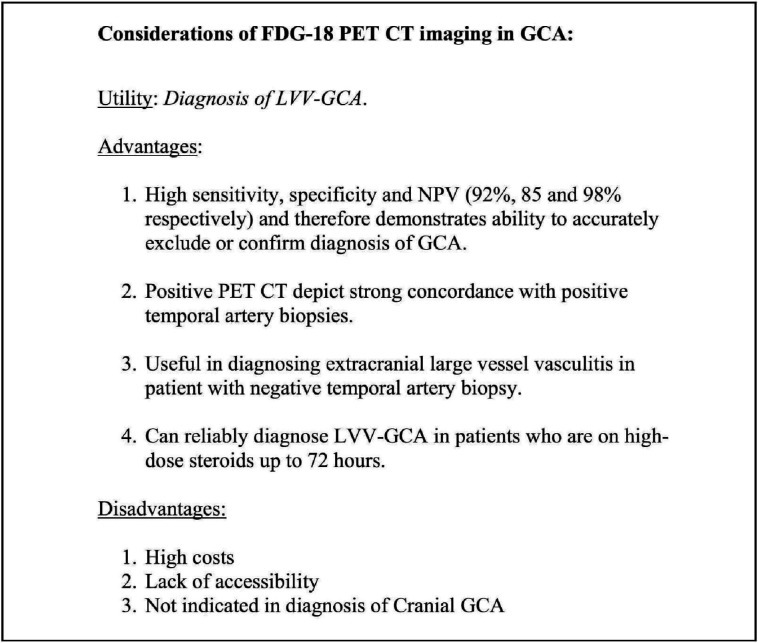

Figure 5.

The utility of FDG-18 PET CT imaging in GCA. LVV-GCA, large-vessel vasculitis-giant cell arteritis, NPV, negative predictive value; PET, positron emission tomography; FDG-18, Fluorodeoxyglucose 18.

High-dose steroids remain the mainstay treatment for GCA. However, the treatment is limited by significant steroid-related complications (hyperglycaemia, osteoporosis, avascular necrosis, psychosis, infections) and increased risk of disease relapse in the setting of steroid tapering or cessation. Conventional immunosuppressants (eg, methotrexate, azathioprine) has been trialled with variable response observed. IL-6 is a pleotropic cytokine that has been implicated in the pathophysiology of PMR and GCA, and therefore, identified as a promising target for treatment. A retrospective multicentre open label study, by Loricera et al, conducted on 22 GCA patients (either refractory GCA or steroid intolerant) treated with tocilizumab, revealed that 86% of cases demonstrated a rapid and sustained improvement. The GIACTA trial was the first large scale double-blinded, randomised placebo-control study, published in NEJM, that evaluated the potential of tocilizumab as a steroid sparing agent. This trial demonstrated that sustained remission (clinical absence of flare signs and symptoms with normal ESR) was achieved in 56% and 53% of patients treated with weekly and alternate weekly tocilizumab injections, respectively, compared with 14% in the placebo group that underwent the 26-week prednisolone weaning regime (p<0.001). The overall incidence of serious adverse events was lower in the treatment group in comparison to the placebo group. Based on these two studies, tocilizumab has demonstrated efficacy as a steroid-sparing agent with superiority in achieving sustained disease remission over high-dose prednisolone alone. There also appeared to be no significant difference in adverse treatment events between those receiving tocilizumab and placebo, thereby delineating that the treatment benefit outweighed the risk.88 89 In 2017, tocilizumab was Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved as a treatment for GCA.90

To summarise, our case series delineates the notable heterogeneity of clinical symptoms in GCA. Increased awareness of the variability of GCA presentations, particularly those with solitary extracranial involvement, is important. A more comprehensive history that addresses features of moderate (as well as large) vessel ischaemia may aid physicians in establishing early clinical suspicion of atypical GCA. Suspected acephalic cases should be considered for urgent diagnostic imaging with whole body-PET CT. There are limited classification criteria or guidelines available for an approach to evaluation of extracranial GCA and further research into this is warranted to improve awareness and diagnostic accuracy of this condition.

Learning points.

Non-specific presentations of giant cell arteritis (GCA) are well known with associated diagnostic challenges leading to delayed management and potential vascular complications.

A comprehensive evaluation of signs and symptoms specific to medium and large-vessel vasculitis (LVV) is required to establish a high index of suspicion for LVV-GCA.

Suspected extracranial GCA cases should be immediately considered for early imaging with MR Angiography or whole-body PET.

Further research into the modification of guideline approaches to LVV and GCA should be considered.

Acknowledgments

Dr David Nolan, Consultant Physician and Head of Department at Royal Perth Hospital, Department of Immunology, Victoria Square, Perth WA 6000.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors (NV, OO, JM and WJ) were involved in the conceptualisation and design of the article. Tables and images (exempting the PET images) were created by NV. Authors, OO, NV and WJ were personally involved in the management of one or both cases. Clinical information on the cases were obtained through patient hospital records and analysed thoroughly by all four authors. Additional information on the presentation and management of the cases were obtained via personal interviews with the patients conducted by WJ, OO and NV. This article was extensively reviewed and formatted by all four authors before unanimous approval of the final manuscript draft was achieved.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

References

- 1. Ponte C, Rodrigues AF, O'Neill L, et al. Giant cell arteritis: current treatment and management. World J Clin Cases 2015;3:484. 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i6.484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lazarewicz K, Watson P. Giant cell arteritis. BMJ 2019;110:l1964. 10.1136/bmj.l1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meskimen S, Cook T, Blake Jr R. Management of giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. AFP Journal 2000;61:2061–8 https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2000/0401/p2061.html [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tucker LJ, Mankia KS, Magliano M. Extra-cranial giant cell arteritis: a diagnostic challenge. QJM 2015;108:823–5. 10.1093/qjmed/hcv021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Boysson H, Lambert M, Liozon E, et al. Giant-cell arteritis without cranial manifestations. Medicine 2016;95:e3818. 10.1097/MD.0000000000003818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. González-Gay MA, Prieto-Peña D, Martínez-Rodríguez I, et al. Early large vessel systemic vasculitis in adults. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2019;33:101424. 10.1016/j.berh.2019.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lenton J, Donnelly R, Nash JR. Does temporal artery biopsy influence the management of temporal arteritis? QJM 2006;99:33–6. 10.1093/qjmed/hci141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Idoudi S, Ben Kahla M, Mselmi F, et al. Scalp necrosis revealing severe giant-cell arteritis. Case Rep Med 2020;2020:1–3. 10.1155/2020/8130404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gonzalez-Gay MA, Garcia-Porrua C, Amor-Dorado JC, et al. Fever in biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis: clinical implications in a defined population. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:652–5. 10.1002/art.20523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nys M, Van der Cruyssen F, David K, et al. A case of giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica misdiagnosed as temporomandibular dysfunction. Oral Sci Int 2018;15:81–5. 10.1016/S1348-8643(18)30006-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zaragoza JR, Vernon N, Ghaffari G. Tongue necrosis as an initial manifestation of giant cell arteritis: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Rheumatol 2015;2015:1–4. 10.1155/2015/901795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sobrinho RABdeS, de Lima KCA, Moura HC, et al. Tongue necrosis secondary to giant cell arteritis: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Med 2017;2017:1–5. 10.1155/2017/6327437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. García Gasalla M, Yebra Bango M, Vargas Núñez JA, et al. Giant cell arteritis associated with demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Ann Rheum Dis 2001;60:812–3. 10.1136/ard.60.8.812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larivière D, Sacre K, Klein I, et al. Extra- and intracranial cerebral vasculitis in giant cell arteritis: an observational study. Medicine 2014;93:e265. 10.1097/MD.0000000000000265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ross M, Bursztyn L, Superstein R, et al. Multiple cranial nerve palsies in giant cell arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol 2017;37:398–400. 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dardick JM, Esenwa CC, Zampolin RL, et al. Acute lateral medullary infarct due to giant cell arteritis: a case study. Stroke 2019;50:e290–3. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.026566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dimancea A, Guidoux C, Amarenco P. Minor ischemic stroke and a smoldering case of giant-cell arteritis: a case report. Stroke 2021;52:e749-e752. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.035432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Slemp SN, Martin SE, Burgett RA, et al. Giant cell arteritis presenting with uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2014;22:391–3. 10.3109/09273948.2013.849351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Awh C, Reichstein DA, Thomas AS. A case of giant cell arteritis presenting with nodular posterior scleritis mimicking a choroidal mass. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2020;17:100583. 10.1016/j.ajoc.2019.100583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kopsachilis N, Pefkianaki M, Marinescu A, et al. Giant cell arteritis presenting as choroidal infarction. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med 2013;2013:1–3. 10.1155/2013/597398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Olali C, Aggarwal S, Ahmed S, et al. Giant cell arteritis presenting as macular choroidal ischaemia. Eye 2011;25:121–3. 10.1038/eye.2010.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cimmino MA, Camellino D, Paparo F, et al. High frequency of capsular knee involvement in polymyalgia rheumatica/giant cell arteritis patients studied by positron emission tomography. Rheumatology 2013;52:1865–72. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lyons HS, Quick V, Sinclair AJ, et al. A new era for giant cell arteritis. Eye 2020;34:1013–26. 10.1038/s41433-019-0608-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jacobs ZG, Mohan N. A case of giant cell arteritis with lower extremity myositis on MRI. Internet Journal of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology 2016;4. 10.15305/ijrci/v4i1/210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Butendieck RR, Abril A, Cortese C. Unusual presentation of giant cell arteritis in 2 patients: uterine involvement. J Rheumatol 2018;45:1201–2. 10.3899/jrheum.171341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Buyukpinarbasili N, Gucin Z, Ersoy YE, et al. Giant cell arteritis of the breast. Bezmialem Science 2015;3:87–9. 10.14235/bs.2015.481 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McKendry RJ, Guindi M, Hill DP. Giant cell arteritis (temporal arteritis) affecting the breast: report of two cases and review of published reports. Ann Rheum Dis 1990;49:1001–4. 10.1136/ard.49.12.1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prieto-Peña D, Castañeda S, Atienza-Mateo B, et al. A review of the dermatological complications of giant cell arteritis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2021;14:303–12. 10.2147/CCID.S284795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Patil A, Upadhyaya S, Kashyap V, et al. An unusual case of giant cell arteritis with monoarthritis and orchitis at presentation. Arch Rheumatol 2017;32:268–70. 10.5606/ArchRheumatol.2017.6268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tariq S, Jonny S, Asalieh H. Atypical presentation of giant cell arteritis associated with SIADH: a rare association. BMJ Case Rep 2021;14:e246187. 10.1136/bcr-2021-246187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Evans DC, Murphy MP, Lawson JH. Giant cell arteritis manifesting as mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg 2005;42:1019–22. 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Morris CR, Scheib JS. Fatal myocardial infarction resulting from coronary arteritis in a patient with polymyalgia rheumatica and biopsy-proved temporal arteritis. A case report and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:1158–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Helliwell T, Muller S, Hider SL, et al. Challenges of diagnosis and management of giant cell arteritis in general practice: a multimethods study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019320. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lie JT. Aortic and extracranial large vessel giant cell arteritis: a review of 72 cases with histopathologic documentation. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1995;24:422–31. 10.1016/s0049-0172(95)80010-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Koster MJ, Matteson EL, Warrington KJ. Large-vessel giant cell arteritis: diagnosis, monitoring and management. Rheumatology 2018;57:ii32–42. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nuenninghoff DM, Hunder GG, Christianson TJH, et al. Incidence and predictors of large-artery complication (aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, and/or large-artery stenosis) in patients with giant cell arteritis: a population-based study over 50 years. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:3522–31. 10.1002/art.11353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Unwin B, Williams C, Gilliland W. Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis. Aafp.org, 2022. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2006/1101/p1547.html [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cleveland Clinic . Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR) & Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA): Symptoms, 2022. Available: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4473-polymyalgia-rheumatica-pmr-and-giant-cell-arteritis-gca [Accessed 23 Feb 2022].

- 39. González-Gay Miguel Á, Ortego-Jurado M, Ercole L, et al. Giant cell arteritis: is the clinical spectrum of the disease changing? BMC Geriatr 2019;19:200. 10.1186/s12877-019-1225-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McCausland B, Desai D, Havard D, et al. A stab in the dark: a case report of an atypical presentation of giant cell arteritis (GCA). Geriatrics 2018;3:36. 10.3390/geriatrics3030036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chan FLY, Lester S, Whittle SL, et al. The utility of ESR, CRP and platelets in the diagnosis of GCA. BMC Rheumatol 2019;3:14. 10.1186/s41927-019-0061-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Giant cell arteritis: Always keep it in your head - BPJ 53, 2013. Bpac.org.nz. Available: https://bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2013/June/arteritis.aspx [Accessed 23 Feb 2022].

- 43. Monti S, Águeda AF, Luqmani RA, et al. Systematic literature review Informing the 2018 update of the EULAR recommendation for the management of large vessel vasculitis: focus on giant cell arteritis. RMD Open 2019;5:e001003. 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stanton M, Tiwari V. Polyarteritis nodosa, 2021. Statpearls.com. Available: https://www.statpearls.com/ArticleLibrary/viewarticle/27394 [Accessed 23 Feb 2022]. [PubMed]

- 45. Chhakchhuak C. Isolated polyarteritis nodosa presenting as acute epididymo-orchitis: a case report. J Med Cases 2011. 10.4021/jmc97w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pagnoux C, Seror R, Henegar C, et al. Clinical features and outcomes in 348 patients with polyarteritis nodosa: a systematic retrospective study of patients diagnosed between 1963 and 2005 and entered into the French vasculitis study group database. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:616–26. 10.1002/art.27240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lopez-Beltran A. Vasculitis involving the prostate. Pathol Case Rev 1996;1:70–3. 10.1097/00132583-199607000-00006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pastorino PR, De Merra FE, Carozzi S. [Orthostatic hypotension disclosing an autonomic deficit in a case of horton's temporal arteritis]. Riv Neurol 1990;60:137–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nelveg-Kristensen KE, Le Goueff A, Smith RM, et al. Cardiac decompensation revealing giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology 2021;60:iii9–11. 10.1093/rheumatology/keab106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cocksedge SH, Pozniak AL, Dixon AS. Giant cell (temporal) arteritis presenting with syncope. Clin Rheumatol 1984;3:235–7. 10.1007/BF02030761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Takeshita A, Tanaka S, Orita Y, et al. Baroreflex sensitivity in patients with takayasu's aortitis. Circulation 1977;55:803–6. 10.1161/01.cir.55.5.803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ketch T, Biaggioni I, Robertson R, et al. Four faces of baroreflex failure. Circulation 2002;105:2518–23. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000017186.52382.F4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tulbă D, Popescu BO, Manole E, et al. Immune axonal neuropathies associated with systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:610585. 10.3389/fphar.2021.610585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Phillips AM, Jardine DL, Parkin PJ, et al. Brain stem stroke causing baroreflex failure and paroxysmal hypertension. Stroke 2000;31:1997–2001. 10.1161/01.STR.31.8.1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Biaggioni I, Whetsell WO, Jobe J, et al. Baroreflex failure in a patient with central nervous system lesions involving the nucleus tractus solitarii. Hypertension 1994;23:491–5. 10.1161/01.HYP.23.4.491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fonkoue IT, Le N-A, Kankam ML, et al. Sympathoexcitation and impaired arterial baroreflex sensitivity are linked to vascular inflammation in individuals with elevated resting blood pressure. Physiol Rep 2019;7:e14057. 10.14814/phy2.14057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bellocchi C, Carandina A, Montinaro B, et al. The interplay between autonomic nervous system and inflammation across systemic autoimmune diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:2449. 10.3390/ijms23052449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Čelovská D, Vlčková K, Gonsorčík J. Negative association between lipoprotein associated phospholipase A2 activity and baroreflex sensitivity in subjects with high normal blood pressure and a positive family history of hypertension. Physiol Res 2021;70:183–91. 10.33549/physiolres.934467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mehler MF, Rabinowich L. The clinical neuro-ophthalmologic spectrum of temporal arteritis. Am J Med 1988;85:839–44. 10.1016/s0002-9343(88)80031-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Weerakkody Y. Giant cell arteritis | radiology reference article | Radiopaedia.org Radiopaedia.org; 2010. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/giant-cell-arteritis [Accessed 25 Feb 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Schmidt WA. Role of ultrasound in the understanding and management of vasculitis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2014;6:39–47. 10.1177/1759720X13512256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schmidt WA. Ultrasound in the diagnosis and management of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology 2018;57:ii22–31. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lensen KDF, Voskuyl AE, Comans EFI, et al. Extracranial giant cell arteritis: a narrative review. Neth J Med 2016;74:182–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ameer M, Peterfy R, Khazaeni B. Temporal arteritis, 2021. Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459376

- 65. Zhang K-J, Li M-X, Zhang P, et al. Validity of high resolution magnetic resonance imaging in detecting giant cell arteritis: a meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 2022;32:3541–52. 10.1007/s00330-021-08413-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bley TA, Wieben O, Uhl M, et al. High-resolution MRI in giant cell arteritis: imaging of the wall of the superficial temporal artery. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005;184:283–7. 10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Klink T, Geiger J, Both M, et al. Giant cell arteritis: diagnostic accuracy of Mr imaging of superficial cranial arteries in initial diagnosis-results from a multicenter trial. Radiology 2014;273:844–52. 10.1148/radiol.14140056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Koenigkam-Santos M, Sharma P, Kalb B, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography in extracranial giant cell arteritis. J Clin Rheumatol 2011;17:306–10. 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31822acec6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Dejaco C, Ramiro S, Duftner C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in large vessel vasculitis in clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:636–43. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yip A, Jernberg ET, Bardi M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging compared to ultrasonography in giant cell arteritis: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res Ther 2020;22:247. 10.1186/s13075-020-02335-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Prieto-Peña D, Castañeda S, Martínez-Rodríguez I, et al. Imaging tests in the early diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. J Clin Med 2021;10:3704. 10.3390/jcm10163704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Robinette ML, Rao DA, Monach PA. The immunopathology of giant cell arteritis across disease spectra. Front Immunol 2021;12:623716. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.623716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. González-Gay MA, Prieto-Peña D, Castañeda S. The role of PET/CT in the evaluation of patients with large-vessel vasculitis: useful for diagnosis but with potential limitations for follow-up. Rheumatology 2022;61:4587–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/keac251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sammel AM, Hsiao E, Schembri G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of positron emission tomography/computed tomography of the head, neck, and chest for giant cell arteritis: a prospective, double-blind, cross-sectional study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1319–28. 10.1002/art.40864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gildberg-Mortensen RA, Øster-Jørgensen E, Weihe JP, et al. SAT0171 FDG PET-CT in polymyalgia reumatica and giant cell arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:A639.2–A639. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-eular.1897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Emamifar A, Ellingsen T, Hess S, et al. The utility of 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with clinical suspicion of polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis: a prospective, observational, and cross-sectional study. ACR Open Rheumatol 2020;2:478–90. 10.1002/acr2.11163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hay B, Mariano-Goulart D, Bourdon A, et al. Diagnostic performance of 18F-FDG PET-CT for large vessel involvement assessment in patients with suspected giant cell arteritis and negative temporal artery biopsy. Ann Nucl Med 2019;33:512–20. 10.1007/s12149-019-01358-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Nielsen BD, Gormsen LC, Hansen IT, et al. Three days of high-dose glucocorticoid treatment attenuates large-vessel 18F-FDG uptake in large-vessel giant cell arteritis but with a limited impact on diagnostic accuracy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2018;45:1119–28. 10.1007/s00259-018-4021-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Clifford AH, Murphy EM, Burrell SC, et al. Positron emission tomography/computerized tomography in newly diagnosed patients with giant cell arteritis who are taking glucocorticoids. J Rheumatol 2017;44:1859–66. 10.3899/jrheum.170138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Nienhuis PH, Sandovici M, Glaudemans AW, et al. Visual and semiquantitative assessment of cranial artery inflammation with FDG-PET/CT in giant cell arteritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2020;50:616–23. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Anati T, Hoffman Ben Shabat M. Pet/Ct uncovers cranial giant cell arteritis. Eur J Hybrid Imaging 2021;5:20. 10.1186/s41824-021-00114-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Muratore F, Kermani TA, Crowson CS, et al. Large-vessel giant cell arteritis: a cohort study. Rheumatology 2015;54:463–70. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kermani TA, Warrington KJ. Lower extremity vasculitis in polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2011;23:38–42. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283410072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ling JD, Hashemi N, Lee AG. Throat pain as a presenting symptom of giant cell arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol 2012;32:384. 10.1097/WNO.0b013e318270ffaf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kondo T, Ohira Y, Uehara T, et al. Cough and giant cell arteritis. QJM 2018;111:747–8. 10.1093/qjmed/hcy095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Shikino K, Yamashita S, Ikusaka M. Giant cell arteritis with carotidynia. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:1403–4. 10.1007/s11606-017-4093-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Nair JR, Somauroo JD, Over KE. Myopericarditis in giant cell arteritis: case report of diagnostic dilemma and review of literature. BMJ Case Rep 2012;2012. 10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5469. [Epub ahead of print: 28 Jun 2012]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Stone JH, Tuckwell K, Dimonaco S, et al. Trial of tocilizumab in giant-cell arteritis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:317–28. 10.1056/NEJMoa1613849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Loricera J, Blanco R, Hernández JL, et al. Tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis: multicenter open-label study of 22 patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2015;44:717–23. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Commissioner Oof the. FDA approves first drug to specifically treat giant cell arteritis. Fda. Available: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-drug-specifically-treat-giant-cell-arteritis