PURPOSE:

Stigma surrounding prescription opioids, or opioid stigma, is increasingly recognized as a barrier to effective and guideline-concordant cancer pain management. Patients with advanced cancer report high rates of pain and prescription opioid exposure, yet little is known about how opioid stigma may manifest in this population.

METHODS:

We conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with 20 patients with advanced cancer and 11 support providers between March 2020, and May 2021. We took a rigorous inductive, qualitative descriptive approach to characterize how opioid stigma manifests in the lives of patients with advanced cancer.

RESULTS:

Patients and their support providers described three primary manifestations of opioid stigma: (1) direct experiences with opioid stigma and discrimination in health care settings (eg, negative, stigmatizing interactions in pharmacies or a pain clinic); (2) concerns about opioid stigma affecting patient care in the future, or anticipated stigma; and (3) opioid-restricting attitudes and behaviors that may reflect internalized stigma and fear of addiction (eg, feelings of guilt).

CONCLUSION:

This qualitative study advances our understanding of opioid stigma manifestations in patients with advanced cancer, as well as coping strategies that patients may use to alleviate their unease (eg, minimizing prescription opioid use, changing clinicians, and distancing from perceptions of addiction). In recognition of the costs of undermanaged cancer pain, it is important to consider innovative treatment strategies to address opioid stigma and improve pain management for patients with advanced cancer. Future research should examine opportunities to build an effective, multilevel opioid stigma intervention targeting patients, clinicians, and health care systems.

INTRODUCTION

Prescription opioids are considered to be standard, guideline-concordant pain care and commonly perceived as efficacious for cancer pain.1-3 However, high-profile efforts to contain the opioid epidemic may contribute to negative views of prescription opioids. Patients with cancer are typically exempted from opioid-restricting state laws and clinical guidelines.4 Despite recognition that prescribing restrictions may not be appropriate for patients with cancer, effective cancer pain management is complicated by stigma surrounding prescription opioids, or opioid stigma.

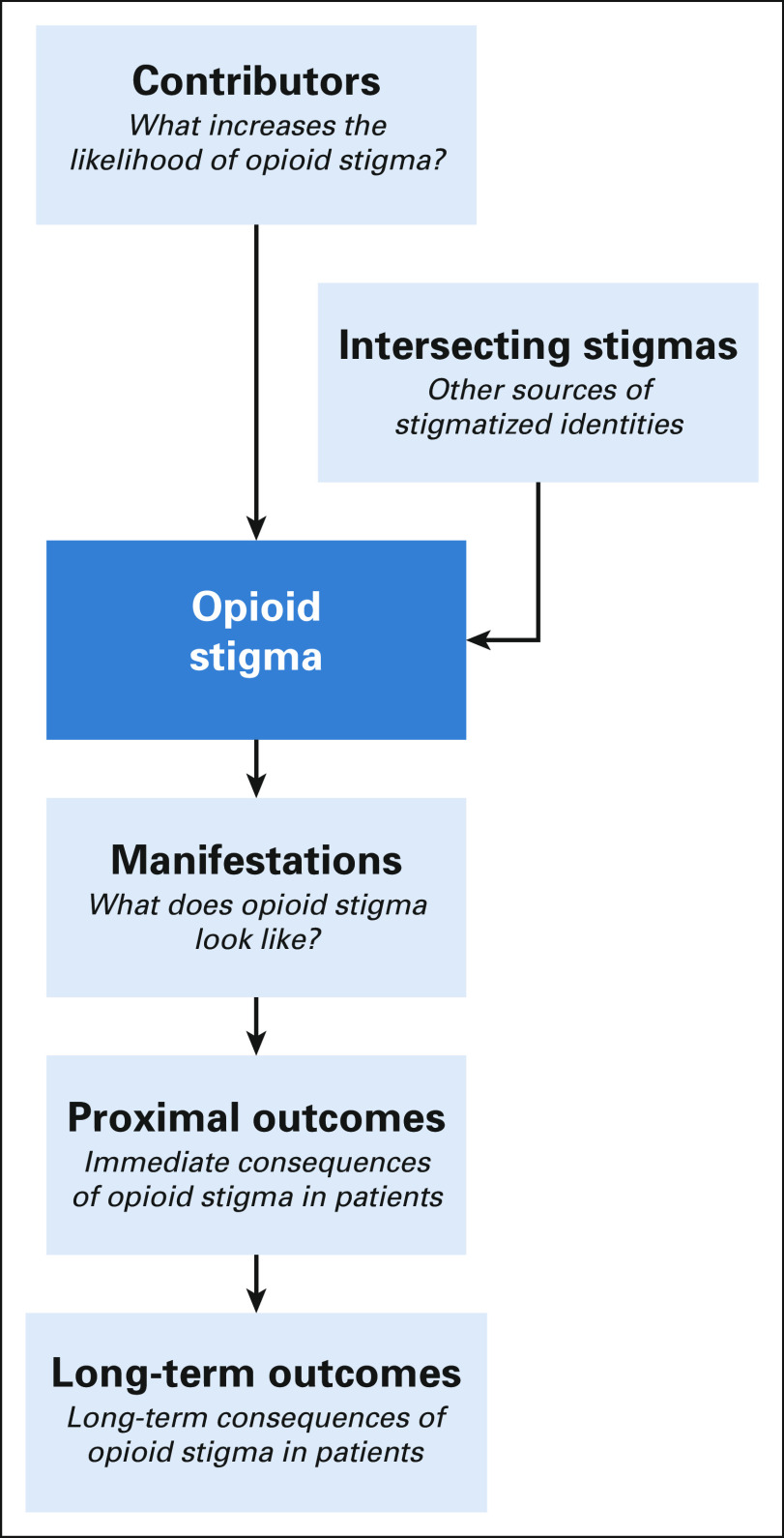

Opioid stigma can be conceptualized using the Opioid Stigma Framework (OSF), a multilevel conceptual framework that integrates oncology, health-related stigma, and pain literature (Fig 1).5 Manifestations, or ways in which opioid stigma can be observed and experienced, is a key concept in understanding barriers to effective opioid pain management for patients with cancer. In theory, opioid stigma manifestations can include direct experiences of discrimination; internalized stigma, or the degree to which patients apply negative attitudes toward themselves; and anticipated stigma, in which patients expect poor future treatment.

FIG 1.

Opioid stigma framework.

Emerging evidence offers a glimpse into how opioid stigma may manifest for patients with cancer. In 2019, a survey of patients with active disease in Florida demonstrated that opioid stigma is common (61%) and is associated with potentially negative behavior changes (29%), including underutilizing prescribed opioids and avoiding health care interactions.6 Since then, studies conducted in Massachusetts, Georgia, Texas, and the Midwest described patient-reported fears of addiction, difficulty filling opioid prescriptions, negative media coverage, and guilt.7-10 A recent study of oncologists in western Pennsylvania, an area severely affected by the opioid crisis, described stigmatizing interactions between patients and clinicians, pharmacists, and society in general.11 Exploring these concerns with patients directly will fill an important gap in this literature.

Patients with advanced cancer pain report particularly high rates of pain (approximately 75%-90%), and the majority receive opioids.12-14 In a mixed group of inpatients and outpatients with advanced cancer, Azizoddin et al7 reported pervasive fear, guilt, and stigma that contributed to suboptimal opioid behavior and impeded patient-clinician communication. However, how opioid stigma manifests in the day-to-day lives of outpatients with advanced cancer is understudied. Exploring this population's perspectives is critical to refine our understanding of opioid stigma in cancer pain and provide a broad scientific evidence base in support of the OSF. Thus, in the current study, we conducted in-depth interviews with patients with advanced solid-tumor cancers and their self-identified support providers to explore experiences with opioid stigma.

METHODS

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Eligible patients were adults with advanced (stage III or IV) solid tumors currently receiving care from a UPMC Hillman Cancer Center medical oncologist, who were prescribed or recommended opioids for moderate-to-severe pain related to cancer or its treatment. Patients were excluded if their referring oncologist determined that they were unable to participate in an in-depth interview, they did not have a telephone for study contact, or they were unable to respond to questions in English. Eligible support providers were adult family members or friends of a participating patient, who were identified by the patient as the person most involved in their care. Support providers were excluded if they did not have a telephone for study contact, or if they were unable to respond to questions in English.

Recruitment Approach

UPMC Hillman Cancer Center medical oncologists who participated in a prior qualitative study on pain management in patients with advanced cancer11 were asked to identify potentially eligible patients under their care and obtain permission for contact. A member of the study team then approached the patient, either in person during a regularly scheduled clinical visit or over the phone at a convenient time for the patient, explained the study, answered questions, and documented the patient's verbal consent.

Support providers were approached in person (if available) or contacted via telephone and provided written or verbal consent after being told about the study. Although encouraged, patient participants were not required to identify a support provider.

Qualitative Interview Methods

Qualitative description is common in qualitative health research and seeks to describe, understand, and interpret participants' experiences without abstracting to the level of social theory. We took an inductive, qualitative descriptive approach to analysis in this study.15,16 Initial interview guides were developed by the PI and reviewed by the qualitative methodology team to ensure proper flow, verbiage, and phrasing (ie, open-ended questions that were not leading). The patient interview guides covered the interviewees' experiences with pain and pain treatment, their experiences with cancer-related pain and the treatment of that pain (including experiences with prescribers and pharmacists), their friends'/family's opinions on taking opioids for cancer-related pain, their storage and use of opioids, and their general thoughts on the opioid epidemic. The interview guide for support providers covered experiences providing support for the patient, experiences in helping manage cancer-related pain, thoughts on the use of opioids for cancer-related pain management, their own experiences with opioids (if any), and thoughts on the opioid epidemic (Data Supplement, online only).

All interviews were conducted via telephone by two trained qualitative interviewers (F.d.A.C. and R.W.). Interviewers reported preliminary findings to the study team throughout data collection. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, with identifying details redacted. Because sample size in qualitative studies is frequently driven by the concept of thematic saturation (ie, the point at which conducting additional interviews does not result in additional insights), we planned to interview 20 patient participants, and at least 10 support providers, to have a high likelihood of reaching saturation. As is common in qualitative research, the interviewer kept detailed notes as they were conducting the interviews, which were then used to determine that thematic saturation was reached.

Data Analysis

Data analysis followed established procedures for thematic analysis, including review and coding of data and the identification of themes in the coded data.17,18 One interviewer (R.W.) served as the primary coder and analyst for all interviews. Transcripts were reviewed by the primary analyst (R.W.) and the lead qualitative methodologist (M.H.) as they were produced to create inductively derived codebooks tailored to each set of interviews. Codebooks were composed of codes and concepts identified from the content of the interviews, and then used to code the interviews. To ensure consistency in coding, two experienced qualitative coders (members of the QualEASE team, B.K. and A.D., supervised by M.H.) coded 16 of the 20 patient transcripts and resolved coding differences, clarifying code definitions and rules for use as necessary. The remaining four interviews were conducted independently by the primary coder. The primary coder (R.W.) and another experienced coder (A.D.) both coded all of the support provider interviews, and resolved all coding differences as previously described. Once coding was finalized, the primary coder reviewed the coding to conduct both content and thematic analyses of both sets of data.19 The content and thematic analyses were presented to the PI and the rest of the study team for review and refinement as a form of investigator triangulation.

Given the wide-ranging nature of the interview guide, the resulting data encompasses many topics. In this manuscript, we present a thematic analysis of the interview findings related to opioid stigma. Planned future analyses will focus on (1) intersecting addiction and prescription opioid stigmas, and (2) structural and systems-level challenges with prescription opioid pain management.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

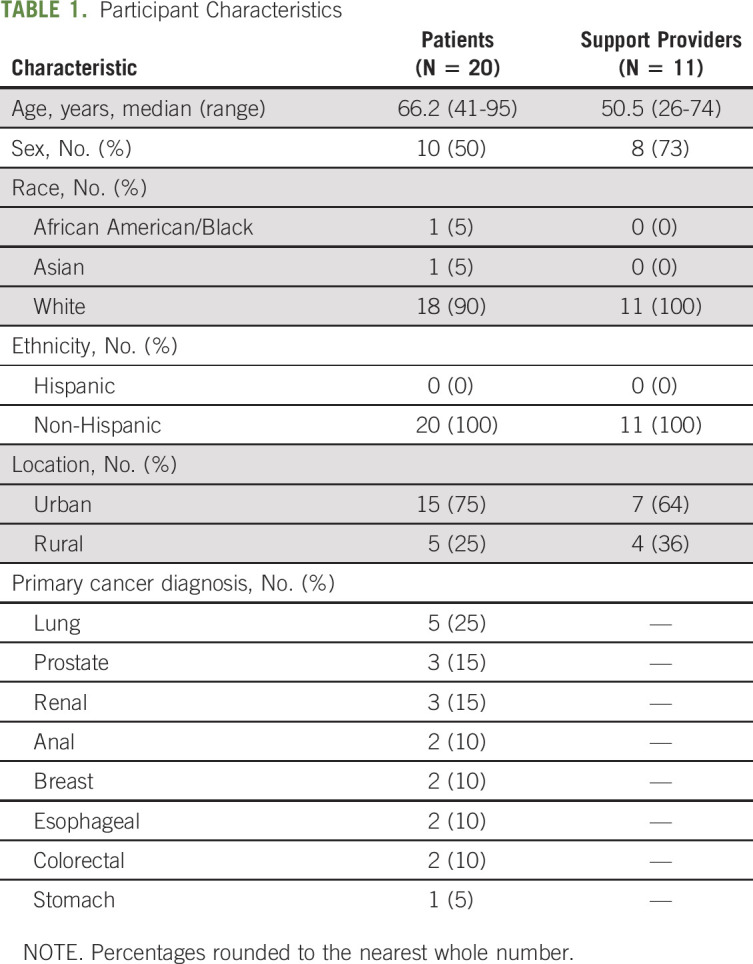

Sociodemographic characteristics and primary cancer diagnosis are shown in Table 1. A total of 20 patients and 11 support providers participated in the interviews, which were conducted between March 2020 and May 2021. Cancer history varied widely, although most patients reported being diagnosed with their current cancer 1-2 years before the interview with an initial diagnosis range of 1 month-12 years.

TABLE 1.

Participant Characteristics

Prescription Opioid Behaviors and Perceived Benefits

The majority (16/20) of patients consistently used at least one type of prescription opioid to manage cancer-related pain—including oxycodone (10), hydrocodone/acetaminophen (four), morphine (two), codeine (one), tramadol (one), and a fentanyl patch (one)—typically prescribed by their oncologist (12). Two patients described using opioids during specific periods during treatment only. One patient reported using morphine, but for pain unrelated to their cancer. One patient denied pain (just discomfort), and thus did not require opioids.

Most patients managed their own opioid medication regimens on a day-to-day basis. In general, patients felt that their opioid medications helped to improve—but not eliminate—their pain (it makes it more tolerable) and improved daily functioning.

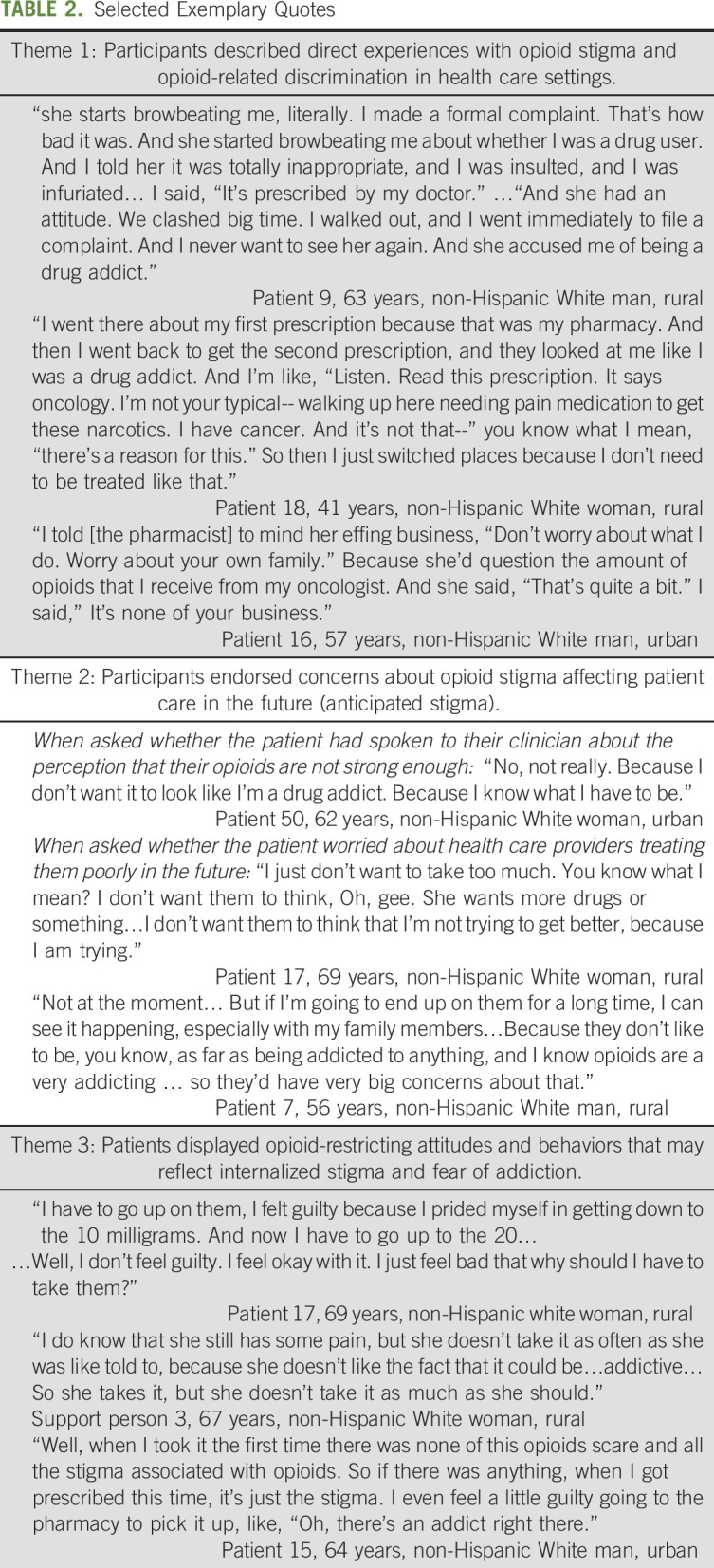

Themes Identified

Please see exemplary quotes for each theme listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Selected Exemplary Quotes

Theme 1: participants described direct experiences with opioid stigma and opioid-related discrimination in health care settings.

Generally, participants reported feeling comfortable talking with their current prescribers (typically oncologists) about opioids for pain management and highlighted the importance of a positive clinician-patient relationship. However, some patients described stigmatizing experiences in other health care settings (eg, a pain clinic or the pharmacy). Participants commonly described feeling as if they were being treated like a drug user in these situations. They combatted this perception by defending the legitimacy of cancer pain and citing the valid prescription (eg, “I have cancer, it's not that. There's a reason for this,” “It's prescribed by my doctor.”) In some cases, these experiences led patients to change care providers, switch pharmacies, or send family members in their place.

One participant recounted an episode in which she noticed that her prescription was running out faster than she was using it, leading to an awkward encounter with her prescribing oncologist. Eventually, she discovered that her medications were being stolen by her in-home nurse. The participant commented on how her race contributed to the situation:

“I’m a Black female, and people automatically think sometimes that you’re trying to just do things. And I didn’t know whether I was justly or unjustly being insulted.…I’m going to be honest with you. I was [inaudible] on a racial thing because the person was Caucasian who was doing this, and I’d say had the roles been reversed I’m pretty sure that they’d have had me right up under the bus. But I’m trying not to be that way.”

Patient 19, 66 years, non-Hispanic Black female, urban

Theme 2: participants expressed concerns about opioid stigma affecting patient care in the future (anticipated stigma).

Some participants expressed worries about stigma occurring in the future, even if they had not directly experienced stigma or discrimination. These concerns led some patients to avoid communicating about their pain to their clinician, even if they had not experienced stigma with that clinician to date. Patient participants were concerned about their clinician's views of them and wanted to ensure that they would not be viewed as seeking more drugs. Outside of health care settings, participants generally endorsed strong support from their family and loved ones in their use of prescription opioids for pain management. However, a few participants also expressed concerns about this support shifting in the future, especially if they were to be on opioids for an extended period of time.

Theme 3: patients displayed opioid-restricting attitudes and behaviors that may reflect internalized stigma and fear of addiction.

Most patient participants rejected internalizing overt stereotypes about prescription opioid use. Participants described cancer pain and opioid prescriptions as legitimate and reiterated their commitment to taking opioids as prescribed (“if you take it to manage your pain, you're fine”). As before, participants drew distinctions between patients with advanced cancer and patients with addiction (“I think it's fine to be aware of the risks of addiction and things, but it's necessary medicine to treat a very, very painful and at times debilitating condition.”). Despite the common perception that opioids are appropriate for cancer pain, several participants desired less opioid prescribing and/or attempted to minimize their medication use. Patient pain levels often fluctuated, and some participants felt they should be able to just quit taking the pain medication. Patients noted that the current stigma around opioids resulted in them feeling guilty about their prescription opioid use, especially when interacting with others (eg, when filling prescriptions at the pharmacy).

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study identified several ways in which opioid stigma manifests in patients with advanced cancer, including direct experiences with health care professionals, anticipated worry, and internalized concerns. Findings advance a growing body of opioid stigma-related literature by analyzing direct patient and support provider perspectives on outpatient opioid pain management in the context of advanced cancer. Additionally, the results of this study offer support for the OSF concept of opioid stigma manifestations and extends its applicability to patients with advanced disease.5

In general, most participants felt that overt stereotypes about opioid misuse were not applicable to patients with advanced cancer. Participants often specified that opioid prescribing was appropriate for legitimate pain, although they also wanted to minimize prescription opioid use. These attitudes may reflect a subtle sense of internalized stigma, characterized by opioid-restricting behaviors and uneasiness with medication changes. Left unaddressed, internalized stigma can lead to worsening shame and guilt when cancer progresses, pain worsens, and opioid dosages increase. Rejection of overt stereotypes contrasts with prior work by Azizoddin et al,7 where participants considered use of prescription opioids to be a distressing moral failure. Notably, the prior study included patients hospitalized in the midst of a pain crisis, suggesting that opioid stigma may manifest differently in acute inpatient settings. The current study focused solely on outpatient opioid pain management, and thus may represent a day-to-day perspective on opioid pain management.

By tightly controlling prescription opioid use, patients can better manage how they are perceived by others. Throughout this study, participants drew clear contrasts between patients with advanced cancer pain and people with addiction, creating a sense of distance between the two groups. Social distancing (in the cognitive sense) is an established coping strategy where people highlight differences between themselves and members of a stigmatized group.20 In context of the opioid crisis, distancing may be used as a protective mechanism to guard against pervasive stereotypes, judgments, and discrimination commonly associated with opioid addiction. However, there are significant limitations to this coping strategy, because cancer and addiction are not mutually exclusive. Although estimates vary, as many as one in five patients with cancer pain might be at risk for nonmedical opioid use (ie, use of opioids differently than prescribed).21 If patients feel the need to distance themselves from perceptions of addiction, they will be less likely to recognize potential problematic behaviors and seek appropriate help.

Decades of literature show that particular patient groups (eg, people of color, patients in rural areas, and women) are at higher risk for pain undertreatment and face barriers to accessing pain care.9,22-27 Further work is needed to understand how systemic influences such as racism may intersect with opioid stigma to create unique challenges for people of color. Our sample was lacking in racial and ethnic diversity, likely because of a sampling strategy that relied on oncologist referral without identifying specific goals for patient attributes, combined with a primarily non-Hispanic White patient population in these clinics. However, examining how opioid stigma manifests in diverse populations is critical to building a comprehensive understanding of opioid stigma. Thus, the next step of this work is to specifically solicit perspectives from a diverse population of patients with cancer pain that focuses on patient at high risk for pain undertreatment, including people from racial and ethnic minority groups, people from rural, underserved areas, and people of low socioeconomic status, among others. Building on this research in diverse populations will provide the necessary literature base for creating robust, inclusive interventions to effectively target opioid stigma. Opioid stigma and its sequelae, including undermanaged pain, has the potential undermine the health and well-being of patients with cancer. Stigma has been repeatedly associated with worse health outcomes in individuals with serious medical and psychiatric illnesses.28-35 As outlined in the OSF and prior literature, potential consequences of opioid stigma specifically include avoidance of health care interactions, suboptimal prescription opioid behaviors, social isolation, emotional distress, limited access to opioids, reduced quality of life, and suboptimal pain management. In turn, undermanaged cancer pain is also associated with a variety of adverse health consequences, including functional limitations (eg, inability to work), suboptimal health behaviors (eg, disturbed sleep and reduced physical activity), emotional distress, social isolation, high health care utilization, and shorter survival.36-40 Given these wide-ranging consequences, it is important to develop strategies to mitigate opioid stigma in patients with cancer pain. Prior research in other stigmatized conditions (eg, HIV and mental health) offer promise that multilevel interventions, spanning patients, clinicians, and health care institutions, can be effective at addressing stigma.41,42 Taking current and prior research into account, along with the conceptual basis of the OSF, future interventions to address manifestations of opioid stigma may include efforts to minimize internalized stigma (eg, guilt, fear, and discomfort), address pervasive negative attitudes about addiction, and improve clinician-patient interactions in medical settings.

Limitations to this study must be noted. For instance, three fifths of participants were having their pain managed by their oncologists. However, recent data suggest that oncologist opioid prescribing decreased in recent years,43,44 so these experiences may not apply to all patients with advanced cancer pain. Additionally, consistent with prior work, most patients reported positive oncologist-patient relationships.11 This sample was referred by oncologists who participated in a prior phase of qualitative interviews. Thus, participants with good relationships with their oncologist may have been more likely to be referred for and/or to participate in this study. Finally, as noted above, the sample was primarily non-Hispanic White from urban areas, with little racial and ethnic diversity. Given documented disparities in cancer pain management,22,24,27,45,46 the results may not be generalizable to people of color, who face additional barriers to cancer pain management.

In summary, this qualitative study described several manifestations of opioid stigma in patients with advanced cancer, including internalized and anticipated stigma and direct experiences of discrimination. The results also reflected a pervasive unease with perceptions of addiction, which may influence patient coping strategies (eg, distancing and opioid-restricting behaviors) and efforts to maintain a positive image with their clinicians. In recognition of the costs of undermanaged cancer pain, it is important to consider innovative treatment strategies to address opioid stigma and improve pain management for patients with advanced cancer. Future research should examine opportunities to build an effective, multilevel opioid stigma intervention targeting patients, clinicians, and health care systems.

Megan Hamm

Employment: Arcadia Health Solutions (I)

Antoinette Wozniak

Consulting or Advisory Role: BeyondSpring Pharmaceuticals, Epic, HUYA Bioscience International, Odonate Therapeutics, Janssen Oncology, GlaxoSmithKline, Regeneron, Novocure, OncLive/MJH Life Sciences, Premier, Inc, oncoboard, BeiGene, Incyte, Daiichi Sankyo/Lilly, kneis, Genentech

Jessica S. Merlin

Research Funding: Cambia Health Foundation

Yael Schenker

Honoraria: UpToDate

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

Supported by a grant from the Hillman Development Fund and the Palliative Research Center (PaRC) at the University of Pittsburgh. The project used resources provided through the Clinical Protocol and Data Management and Protocol Review and Monitoring System, which are supported in part by award P30CA047904. Dr H.W.B. time was financially supported by an institutional K award at the University of Pittsburgh (NIH KL2 TR001856 [PI: Rubio]). Dr Y.S. was supported by K24AG070285.

J.S.M. and Y.S. contributed equally to this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Hailey W. Bulls, Megan Hamm, Shane Belin,Lindsay M. Sabik, Jessica S. Merlin, Yael Schenker

Financial support: Lindsay Sabik, Yael Schenker

Administrative support: Shane Belin, Yael Schenker

Provision of study materials or patients: Shane Belin, Yael Schenker

Collection and assembly of data: Hailey W. Bulls, Megan Hamm, Rachel Wasilko, Flor de Abril Cameron, Shane Belin, Jessica S. Merlin, Yael Schenker

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Manifestations of Opioid Stigma in Patients With Advanced Cancer: Perspectives From Patients and Their Support Providers

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Megan Hamm

Employment: Arcadia Health Solutions (I)

Antoinette Wozniak

Consulting or Advisory Role: BeyondSpring Pharmaceuticals, Epic, HUYA Bioscience International, Odonate Therapeutics, Janssen Oncology, GlaxoSmithKline, Regeneron, Novocure, OncLive/MJH Life Sciences, Premier, Inc, oncoboard, BeiGene, Incyte, Daiichi Sankyo/Lilly, kneis, Genentech

Jessica S. Merlin

Research Funding: Cambia Health Foundation

Yael Schenker

Honoraria: UpToDate

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) : ASCO Policy Statement on Opioid Therapy: Protecting Access to Treatment for Cancer-Related Pain, 2016. https://www.asco.org/sites/new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/advocacy-and-policy/documents/2016-ASCO-Policy-Statement-Opioid-Therapy.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.ESMO Guidelines Committee, Fallon M, Giusti R, et al. : Management of cancer pain in adult patients: ESMO clinical practice guidelines. Ann Oncol 29:iv166-iv191, 2018. (suppl 4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network : NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Adult Cancer Pain Version 2.2016, 2016. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/pain.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bulls HW, Bell LF, Orris SR, et al. : Exemptions to state laws regulating opioid prescribing for patients with cancer-related pain: A summary. Cancer 127:3137-3144, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulls HW, Chu E, Goodin BR, et al. : A framework for opioid stigma in cancer pain. Pain 163:e182-189, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulls HW, Hoogland AI, Craig D, et al. : Cancer and opioids: Patient experiences with stigma (COPES)—A pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manag 57:816-819, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azizoddin DR, Knoerl R, Adam R, et al. : Cancer pain self-management in the context of a national opioid epidemic: Experiences of patients with advanced cancer using opioids. Cancer 127:3239-3245, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown JH, Torres HP, Maddi RD, et al. : Cancer patients’ perceived difficulties filling opioid prescriptions after receiving outpatient supportive care. J Pain Symptom Manage 60:915-922, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jefferson K, Quest T, Yeager KA: Factors associated with Black cancer patients’ ability to obtain their opioid prescriptions at the pharmacy. J Palliat Med 22:1143-1148, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwekkeboom K, Serlin RC, Ward SE, et al. : Revisiting patient-related barriers to cancer pain management in the context of the US opioid crisis. Pain 162:1840-1847, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schenker Y, Hamm M, Bulls H, et al. : “This is a different patient population”: Oncologists’ views on challenges to safe and effective opioid prescribing for patients with cancer-related pain and recommendations for improvement. JCO Oncol Pract 17:e1030-31037, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nersesyan H, Slavin KV: Current aproach to cancer pain management: Availability and implications of different treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag 3:381-400, 2007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paice JA: Cancer pain management and the opioid crisis in America: How to preserve hard-earned gains in improving the quality of cancer pain management. Cancer 124:2491-2497, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Cancer Society : Addressing State Policy Barriers to Cancer Pain Management, 2007. https://secure.fightcancer.org/site/DocServer/Policy_-_Addressing_State_Policy_Barriers_to_Cancer_Pain.pdf;jsessionid=00000000.app30038a?docID=6824&NONCE_TOKEN=2B10B424E86E78A0B0751B4246ED6809 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandelowski M: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 23:334-340, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim H, Sefcik JS, Bradway C: Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: A systematic review. Res Nurs Health 40:23, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun V, Clarke V: Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77-101, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guest G, MacQueen K, Namey E: Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, California, SAGE Publications, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE: Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15:1277-1288, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Link BQ, Yang LH, Phelan JC, et al. : Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophr Bull 30:511-541, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carmichael A-N, Morgan L, del Fabbro E: Identifying and assessing the risk of opioid abuse in patients with cancer: An integrative review. Subst Abuse Rehabil 7:71, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R: Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: Causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain 10:1187-1204, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartley EJ, Fillingim RB: Sex differences in pain: A brief review of clinical and experimental findings. Br J Anaesth 111:52-58, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, et al. : The unequal burden of pain: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med 4:277-294, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green CR, Ndao-Brumblay SK, West B, et al. : Differences in prescription opioid analgesic availability: Comparing minority and white pharmacies across Michigan. J Pain 6:689-699, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joynt M, Train MK, Robbins BW, et al. : The impact of neighborhood socioeconomic status and race on the prescribing of opioids in emergency departments throughout the United States. J Gen Intern Med 28:1604-1610, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephenson N, Dalton JA, Carlson J, et al. : Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer pain management. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc 20:11-18, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsang HWH, Ching SC, Tang KH, et al. : Therapeutic intervention for internalized stigma of severe mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 173:45-53, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turan B, Hatcher AM, Weiser SD, et al. : Framing mechanisms linking HIV-related stigma, adherence to treatment, and health outcomes. Am J Public Heal 107:863-869, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, et al. : Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev 16:319-326, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livingston JD, Boyd JE: Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med 71:2150-2161, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, et al. : HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: A test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav 17:1785-1795, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR: From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: A review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav 13:1160-1177, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fox AB, Earnshaw VA, Taverna EC, et al. : Conceptualizing and measuring mental illness stigma: The mental illness stigma framework and critical review of measures. Stigma Heal 3:348-376, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fife BL, Wright ER: The dimensionality of stigma: A comparison of its impact on the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. J Heal Soc Behav 41:50-67, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Connor M, Weir J, Butcher I, et al. : Pain in patients attending a specialist cancer service: Prevalence and association with emotional distress. J Pain Symptom Manage 43:29-38, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breivik H, Cherny N, Collett B, et al. : Cancer-related pain: A pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann Oncol 20:1420-1433, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Theobald DE: Cancer pain, fatigue, distress, and insomnia in cancer patients. Clin Cornerstone 6:S15-S21, 2004. (suppl 1D) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayer DK, Travers D, Wyss A, et al. : Why do patients with cancer visit emergency departments? Results of a 2008 population study in North Carolina. J Clin Oncol 29:2683-2688, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mantyh PW: Cancer pain and its impact on diagnosis, survival and quality of life. Nat Rev Neurosci 7:797, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nyblade L, Stangl A, Weiss E, et al. : Combating HIV stigma in health care settings: What works? J Int AIDS Soc 12:15, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rao D, Elshafei A, Nguyen M, et al. : A systematic review of multi-level stigma interventions: State of the science and future directions. BMC Med 17:41, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Enzinger AC, Wright AA: Reduced opioid prescribing by oncologists: Progress made, or ground lost? JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 113:225-226, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agarwal A, Roberts A, Dusetzina SB, et al. : Changes in opioid prescribing patterns among generalists and oncologists for Medicare Part D beneficiaries from 2013 to 2017. JAMA Oncol 6:1271-1274, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McNeill JA, Reynolds J, Ney ML: Unequal quality of cancer pain management: Disparity in perceived control and proposed solutions. Oncol Nurs Forum 34:1121-1128, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Enzinger AC, Ghosh K, Keating NL, et al. : U.S. trends and racial/ethnic disparities in opioid access among patients with poor prognosis cancer at the end of life (EOL). J Clin Oncol 38, 2020. (suppl 15; abstr 7005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]