Abstract

The adrenal is a small, anatomically unimposing structure that escaped scientific notice until 1564 and whose existence was doubted by many until the 18th century. Adrenal functions were inferred from the adrenal insufficiency syndrome described by Addison and from the obesity and virilization that accompanied many adrenal malignancies, but early physiologists sometimes confused the roles of the cortex and medulla. Medullary epinephrine was the first hormone to be isolated (in 1901), and numerous cortical steroids were isolated between 1930 and 1949. The treatment of arthritis, Addison’s disease, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) with cortisone in the 1950s revolutionized clinical endocrinology and steroid research. Cases of CAH had been reported in the 19th century, but a defect in 21-hydroxylation in CAH was not identified until 1957. Other forms of CAH, including deficiencies of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, 11β-hydroxylase, and 17α-hydroxylase were defined hormonally in the 1960s. Cytochrome P450 enzymes were described in 1962-1964, and steroid 21-hydroxylation was the first biosynthetic activity associated with a P450. Understanding of the genetic and biochemical bases of these disorders advanced rapidly from 1984 to 2004. The cloning of genes for steroidogenic enzymes and related factors revealed many mutations causing known diseases and facilitated the discovery of new disorders. Genetics and cell biology have replaced steroid chemistry as the key disciplines for understanding and teaching steroidogenesis and its disorders.

Keywords: Addison disease, adrenal hyperplasia, cortisone, cytochrome P450, genetic disease, steroid

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

ESSENTIAL POINTS.

The functions of the adrenal were inferred from the adrenal insufficiency syndrome described by Addison and from the Cushingoid obesity and virilization that accompanied many adrenal malignancies.

Medullary epinephrine was the first hormone to be isolated (1901), and numerous cortical steroids were isolated between 1930 and 1949.

Cases of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) were reported in the 19th century, but the causative biosynthetic defects were defined hormonally in the 1950s and 1960s.

The treatment of arthritis, Addison’s disease, and CAH with cortisone in 1950 revolutionized clinical endocrinology and steroid research.

Great advances in the understanding of steroidogenesis and the various forms of CAH were achieved through steroid chemistry.

Understanding the genetic and biochemical basis of adrenal disorders advanced very rapidly from 1984 to 2004 with the cloning of the genes for steroidogenic enzymes and related factors, revealing a vast array of mutations in a comparatively small number of genes and facilitating detailed understanding of known diseases and discovery of new disorders.

Genetics and cell biology have replaced steroid chemistry as the key disciplines for understanding and teaching steroidogenesis and its disorders.

The history of the adrenal closely parallels the history of Western medical and biological science and vividly illustrates how investigators of different eras formulated their questions and sought answers. The philosophical ruminations of Aristotle and Galen gave way to Renaissance anatomy and then to clinical observation, but scientific understanding of the adrenal required a marriage of clinical medicine with basic science: the chemistry of steroid hormones (1920s-1950s) and the revolution in molecular genetics (1980s-2000s). Hundreds of investigators writing thousands of papers have provided today’s detailed but still incomplete knowledge of the adrenal. Herein we trace this history, concentrating on the adrenal cortex, emphasizing how incisive observation and the application of the newest available scientific techniques have advanced knowledge.

Antiquity to 1800: Finding the Adrenal

The early history of adrenal discovery and research has been reviewed previously (1-6) and is summarized briefly here. It appears that ancient observers did not identify the adrenal as a structure distinct from perinephric fat. In Homer’s Iliad, Book 21, Achilles slew Asteropaios with a single sword stroke: “Near the navel he slashed his belly; all his bowels dropped out uncoiling to the ground” (line 210). Achilles then cast the body into the river Xanthos (Skamander): “… to lie in the sand, where the dark water lapped at it. Then eels and fish attended to the body, picking and nibbling kidney fat away” (lines 236-238) (7). The familiar King James version of the Bible contains 2 verbatim identical passages (Leviticus 3:4 and 4:9) referring to animal sacrifice “… the two kidneys, and the fat that is on them, which is by the flanks . . . .” The great physician of second-century Rome Galen of Pergamon (circa 130-201) may have been the first to mention the adrenal: he described “loose flesh” atop the left kidney and described the vein going to the “capsule of the right kidney.” “For when the vein first appears outside the liver, before reaching the loin, being still high, at its own right side, it sends to the capsule of the right kidney and the bodies around this sometimes spiderweb-like, sometimes hairlike, and sometimes thicker contributions” (8).

The Renaissance brought the scientific study of anatomy. Unpublished anatomical sketches by Leonardo da Vinci in 1485-1490, in the Royal Collection Trust and exhibited in Scotland in 2013 (9), show supra-renal structures that might have been adrenals or perinephric fat (Fig. 1), but Leonardo did not discuss what he was drawing, and he made no effort to inform the world of his observation. Viselius’ famous (and well-illustrated) “De Humanis Corporis Fabrica” (1543) shows the kidneys without adjacent adrenals. The first published description of the adrenal gland was provided by Bartolomeo Eustachio (circa 1520-1574), who described the adrenals as “glandulae quae renibus incumbent” (glands lying on the kidney) in his book Opuscola Anatomica, published in 1564. Eustachio states the adrenals were “diligently overlooked by other anatomists” (perhaps referring to Vesalius) and describes them clearly: “Both kidneys are capped on the extremity towards the cava by a gland. Both are connected with a fold of the peritoneum in such a way that one, if he is not very attentive, does really overlook them, as if they were not present. Their shape resembles that of the kidneys … sometimes one is bigger, sometimes another … early anatomists and those who write ample treatises on this art in our days failed to detect them” (2, 3). Eustachio had planned an anatomical “magnum opus” that was to rival that of Vesalius’ and, with Roman artist Pier Matteo Pini, had prepared 47 engraved copper plates to illustrate the text, but Eustacchio died before completing this project. The first 8 plates were published in the preliminary Opuscula Anatomica, including a clear illustration of the adrenals sitting atop the kidneys (Fig. 2a). Pini’s engraved plates found their way to the papal library, where they remained for about 150 years, until Pope Clement XI gave them to his personal physician, Giovanni M. Lancisi, who published all 47 plates, plus his own notes, in 1714 as Tabulae Anatomicae Clarissimi viri Bartholomaei Eustacci (Fig. 2b). Eustachio’s book was not circulated widely, and most anatomists first encountered his work through Lancisi’s book. Although Lancisi credits Eustachio’s discovery of the adrenal, some authors have reported that this was the first publication of Pini’s engravings (10). D. Lynn Loriaux, who was president of the Endocrine Society in 1995, published his personal account of viewing Eustachio’s book at the Vatican in 1977 or 1978 (11).

Figure 1.

A sketch by DaVinci ca. 1485-1490 of the kidney with an apparent adrenal in the correct anatomic location (RCIN 912597, in the public domain at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leonardo_da_Vinci_-_RCIN_912597,_The_major_organs_and_vessels_c.1485-90.jpg).

Figure 2.

Left, Plate 2 from Eustacchio’s “Opuscola Anatomica,” as reproduced by JM Lancisi in 1714 as “Tabulae Anatomicae” (image from page 64 of Lancisi’s volume, in the public domain at https://search.lib.virginia.edu/sources/uva_library/items/u3606395?idx=0&page=64. This image was also published as Fireu. 2 in Endocrine Reviews 41(1):1-46, 2020). Right, Faceplate of Lancisi’s book (image captured online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bartolomeo_Eustachi).

Eustachio’s work was not widely known; in 1627, Giulio Cesare Casseri (1552-1616) published an illustration of the adrenals atop the kidneys, which may have been the first widely seen illustration of the correct anatomy (Fig. 3) (12). Between 1650 and 1750, multiple anatomists described the adrenals as hollow, fluid-filled organs. The first of these may have been Danish anatomist Caspar Bartholin the Elder (1585-1629), who described the adrenals as filled with “black bile,” probably referring to the medulla undergoing postmortem autolysis (13). His son, Thomas Bartholin, who followed his father as professor of anatomy at the University of Copenhagen, described different anatomic appearances of the adrenal (14), including the hollow adrenal filled with “black bile” (Fig. 4). Bartholin the Elder was the grandfather of Caspar Bartholin the Younger (1655-1738), who described Bartholin’s glands. Others also described an adrenal filled with “black bile,” including Johann Vesling (15), Thomas Wharton (16), and Antonio Molinetti (17); these and other anatomists offered fanciful theories concerning adrenal function, but without evidence (1). There also were “adrenal deniers”: Piccolomini (1586) claimed that the adrenals were rare renal “excrescences” (outgrowths), similar to supernumerary digits (2), and Andre du Laurens, physician to Henry IV of France, wrote in 1640 that “Eustachius claims to find a gland above the kidneys. Sometimes we saw that too; often, however, we stated that there was no such gland” (3) (deniers of science have always been with us). In 1805 Georges Cuvier, professor of animal anatomy at the Museum of Natural History in Paris, established that the adrenal is a solid organ (lacking a hollow cavity filled with “black bile”) and distinguished the cortex from the medulla but provided no insight into their functions (18). In 1831, Friedrich Arnold, professor of anatomy in Heidelberg, showed that the fetal adrenal developed from the embryonic Wolffian ducts (19). Based on histologic studies, the terms “cortex” and “medulla” were introduced in 1836 (20) but without functional insight.

Figure 3.

Left, Giulio Cesare Casseri, from the frontispiece of his book Tabulae Anatomica (Deuchinus, 1627) (in the public domain at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giulio_Cesare_Casseri#/media/File:Casserius.png). Right, Casseri’s illustration of the kidneys, featuring the adrenals, indicated by “G” and labeled “corpuscula reni incumbentia sive Renes succenturiati” (renal corpuscles lying on or above the kidney) (images from page 174 of Casseri’s volume in the public domain at https://archive.org/details/tabulaeanatomica00cass/page/174/mode/2up).

Figure 4.

Thomas Bartholin’s varied adrenal anatomy. The top figure shows hollow, ovoid adrenals, supporting the notion that the adrenals were filled with “black bile”; a variant of this illustration was also published by Johann Vesling (1647) [from (14)] (in the public domain at http://mateo.uni-mannheim.de/camenaref/bartholin/bartholin1/jpg/s123.html).

1697-1889: Discovering Adrenal Functions

The discovery of the adrenals offered no clues to their function, and as detailed by Shumacker, between the time of Eustaccio and Casseri until the time of Addison, at least 50 publications offered fanciful theories, without evidence (1). In 1716 the Academy of Sciences of Bordeaux sponsored an essay competition to discover “Quel est l’usage des glandes surrenales?” (“What is the use of the suprarenal glands?”). The Baron Montesquieu judged the competition but decided none of the entries merited the prize (21). As described by Schäfer, Montesquieu concluded “Perhaps chance may some day effect what all these careful labours have been unable to perform” (22).

Disease often leads to functional insights, and adrenal tumors suggested the adrenal influenced multiple systems. In 1697, Henry Sampson described the clinical course, death, and autopsy of a 6-year-old girl who died in 1688 (23); a 21st-century reading indicates she was virilized, Cushingoid, and died from metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma and a probable renal vein thrombosis (24). Sampson apparently did not know about the adrenal, although other 17th-century writers had mentioned it. In 1809 Cooke reported a similar case in another 6-year-old obese, virilized girl, having a tumor “intimately blended” into the left kidney, but made no mention of the adrenals (25); Cooke did not cite Sampson or any other reports. In 1865, JW Ogle reported the death and autopsy of a 3-year-old girl with obesity and poor growth who had a 22/16 pound left adrenal mass with at least one hepatic metastasis (26). TC Fox reported a similar course in a 2-year-old girl in 1885; he identified a 1½ pound left adrenal tumor with “secondary growths” in the mesenteric lymph nodes and cited reports of 5 other cases (27). Many of these early cases also had venous thromboses. Bulloch and Sequira reviewed the pathology literature concerning adrenal tumors in 1905, compiling 12 cases (28). These authors notably included early cases of probable CAH, clearly noting that the adrenal could profoundly influence the sexual phenotype. Thus, by the beginning of the 20th century, it was apparent that the adrenal, presumably through some form of hyperactivity, could influence body mass, growth, and virilization, but how this happened was unclear.

The role of adrenal insufficiency was first studied in the mid-18th century. The first reports that the adrenals were physiologically important came from Thomas Addison. In describing probable pernicious anemia, he noted that 3 deceased patients “had a diseased condition of the suprarenal capsules”; one had malignancy, one atrophy and one had ‘struma’ (probable tuberculosis) (29). He followed this with a more detailed description of 11 patients, of whom 6 had adrenal tuberculosis; some others may have had autoimmune adrenalitis (Fig. 5). His clinical description of adrenal insufficiency remains clear and lucid today: “The discoloration pervades the whole surface of the body, but is commonly most strongly manifested on the face, neck, superior extremities, penis, scrotum, and in the flexures of the axillae and around the navel … The leading and characteristic features of the morbid state … are, anaemia, general languor and debility, remarkable feebleness of the heart’s action, irritability of the stomach, and a peculiar change of the colour in the skin, occurring in connection with a diseased condition of the suprarenal capsules” (30).

Figure 5.

Left, Thomas Addison (photographer unknown); in the public domain at (https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35152865). Right, Reproduction of Plate 11, showing a postmortem “sketch” of “Mr. S” from Thomas Addison’s 1855 monograph (30) (https://wellcomecollection.org/works/xsmzqpdw). Most of the patients described by Addison had tuberculous adrenalitis, but the patchy vitiligo and scant pubic hair illustrated here suggests autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2f.

Aware of Addison’s work, in 1856 the peripatetic Charles-Edouard Brown-Sequard (1817-1894) wrote 2 papers showing that adrenalectomy caused death (in dogs), inferring that this was due to lack of an adrenal secretion (31). Brown-Sequard wrote 3 additional papers describing the lethal effects of adrenalectomy in 1857 and 1858 (32-34) but others questioned his results [see (35)]; it was not until 1908 that the medical world generally agreed that the adrenals were necessary for life (22). Most famously (or infamously), in 1889 Brown-Sequard reported “rejuvenated sexual prowess” after injecting himself with testicular extracts (36). This was certainly a placebo effect, as recapitulation of Brown-Sequard’s procedures yield a fluid with insignificant amounts of steroids [reviewed in (37)]. Brown-Sequard’s “organotherapy” may have been quackery, but it inspired other research work. In 1891 George Murray injected an extract of sheep thyroid into a woman with myxedema (38), and hypothyroidism was successfully treated with oral desiccated thyroid into the 1960s. Many investigators worked on the isolation of sex steroids; for example, TF Gallagher and Fred Conrad Koch (for whom the Endocrine Society’s most prestigious Laureate Award is named) were early leaders in developing the cock’s comb assay for androgens (39) and in isolating “the testicular hormone” (40). The history of testosterone is reviewed elsewhere (41-43).

Nineteenth-Century Reports of CAH

Because it was a relatively common disease, there must have been individuals who survived with virilizing non-salt-losing CAH throughout history, but the earliest probable case may be the one reported anonymously in The Lancet in 1833, which reiterates a case initially reported in Journal Hebdomadaire by M. (monsieur) Bouillaud: “A person named Valmont, aet. 62, a widower, of small stature, was admitted on the 6th of April into the cholera wards of La Pitie, and died next morning. As Valmont appeared to possess all the attributes of the male sex when received into the wards, we were not a little astonished, when the abdominal organs were opened, at finding in the cavity of the pelvis a perfectly-formed womb!” The anatomic examination was detailed by a M. Manec, who observed “a penis, perfectly formed, of middling size” with hypospadias (Fig. 6). He found no testes but “two ovaries, of the same size as in a girl of 16, and two Fallopian-tubes, with their extremities opening into the uterus, as in a perfect female.” There is a detailed description of the uterus, vagina, and the urethra opening “surrounded by a perfect prostate gland” into the vagina; the adrenals were not mentioned. The anonymous British author in The Lancet concludes that “hermaphrodism can no longer be disputed” and that “[i]n many countries, modifying clauses must be, consequently, introduced into the laws relative to the civil state, the succession of property, and the administration of criminal justice, in order to regulate the position, attributes, and social duties of these intermediate beings” (44).

Figure 6.

Autopsy of genitourinary structures of a virilized female patient with congenital adrenal hyperplasia in 1833 (44). The larger illustration, labeled “Fig. 1” is accompanied by a listing of 15 numbered structures; notable structures include (1) the urethra immediately inferior to the glans penis; (6 and 7) bladder and ureters, respectively; (8) vagina; (10) uterus; (11,12) ovaries; (11) 1 of the Fallopian tubes. The smaller illustration, labeled “Fig. 2” is accompanied by a listing of 7 structures labeled a though g, showing the urethra, Cowper’s glands, corpora cavernosa, and accompanying musculature (in the public domain at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140673602937700).

The best-described early case was reported by Luigi de Crecchio (1832-1894), a forensic pathologist (“professor of legal medicine”) in Naples, who reported the postmortem anatomical findings in Giuseppe Marzo, showing that Marzo had a uterus, Fallopian tubes, and ovaries (45) (Fig. 7). De Crecchio investigated Marzo’s life, including interviews with family and associates. Marzo’s sex assignment at birth was female (with the given name Maria Giuseppa) but was changed at age 4 when a surgeon determined Marzo was a boy with undescended testes. Marzo lived as a man, was twice treated for gonorrhea, never married, and died in an apparent Addisonian crisis at age 44. De Crecchio noted that Marzo had very large adrenals but thought Marzo’s findings indicated a disorder of puberty, and he did not discuss a possible role for the adrenal hyperplasia. A complete translation and exegesis of De Crecchio’s paper was published in 2015 (46).

Figure 7.

Plate 3 from De Crecchio’s paper (45), containing 3 drawings. Fig. 1: longitudinal view of the pelvic contents. Some relevant structures are: 5. Urethra (opened). 10. Vagina. 14. Uterus (opened). 15. Cervix. 17. Right broad ligament, containing the right ovary and Fallopian tube 19. Left Fallopian tube and fimbriae. 20. Left ovary. 23. Right corpus cavernosum (cut). 24. Urethral meatus. Fig. 2: connection of the vagina to the prostatic urethra; numbers as in Fig. 1; for details see (46). Fig. 3: drawing of a Graafian follicle from Marzo, as seen microscopically at 620× (in the public domain; from the University of Michigan Library, http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015013772457).

Possibly the earliest report of familial CAH was in 1886 from John Phillips, “Physician to the British Lying-In Hospital; Senior Assistant Physician, Chelsea Hospital for Women.” He reported the delivery of a woman’s ninth child; 4 of the previous children had “spurious hermaphroditism” (a term that preceded “pseudohermaphroditism,” both referring to individuals whose external genital anatomy did not correspond to the physician’s expectations based on the gonadal anatomy). The 4 affected children “gradually wasted” and died at 24, 59, 40, and 19 days of age. The last of these children is described in detail, with clitoromegaly, a urogenital sinus, and a palpable uterus. At the postmortem examination “the pelvic organs were found to be entirely female” “with the kidneys and suprarenal capsules (which were very large) …” (47). This history strongly suggests salt-wasting CAH in these 4 infants, but the hereditary basis of CAH was vigorously debated into the 1950s. The proximity of the adrenal and kidney and the resemblance of renal cell cancer cells to adrenocortical cancer cells has led to confusion, as renal-cell cancers were once believed to originate from aberrant adrenal tissue. In 1883 Grawitz described renal-cell cancers and termed them “struma lipomatodes aberrata renis” (48). His theory that these renal tumors arise from adrenal tissue led to the common term “hypernephroma,” a misleading term that persisted into the mid-20th century.

These early reports of CAH contributed to the understanding that the adrenals can influence sexual phenotypes. In 1912 Ernest Glynn, a pathologist in Liverpool, reviewed the literature concerning adrenal tumors that influenced the patient’s sexual phenotype (49). His Table I lists 17 cases of “Sex Abnormalities in Children associated with Adrenal Hypernephroma verified post mortem” and 6 cases of “Adrenal Hypernephroma in Young Adult Females associated with Changes in Sex Characters”; his Table II lists 6 cases of “Male Sex Characters in Adult Females Associated with Adrenal Hypernephroma.” Glynn’s Tables I and II list virilizing adrenal tumors, although his case #22 (on page 166) was most likely a case of CAH. Under the heading of “Pseudo-hermaphroditism” he says, “The occurrence of hyperplasia of the adrenal gland, or of accessory adrenals with some cases of pseudo-hermaphroditism, is another example of the association between the adrenal and sex”; he then summarizes 9 cases, several of whom (including 2 siblings) certainly had CAH. Glynn’s Table III lists 13 cases “of the Association of Pseudo-hermaphroditism, particularly Feminine, with Bilateral Hyperplasia of the Adrenal Gland”; most of these individuals clearly had CAH. Glynn correctly concluded “The adrenal cortex and medulla have a different development and different functions; the former is especially connected with growth and sex characters, the latter with blood pressure” and “In pseudo-hermaphroditism the sex abnormalities are mainly congenital, and the adrenal lesions, if any, are bilateral hyperplasia or cortical rests” (49).

In 1912 Alfred Gallais presented his doctoral thesis to the Faculté de Medécine de Paris (Sorbonne), in which he describes “le Syndrome Génito-Surrénal” (50). His work summarizes a hodge-podge of clinical reports of people with adrenal tumors and Cushing disease, and some with probable CAH, and does not attempt to categorize the cases as does Glynn, but it is remembered as the origin of the term “adrenogenital syndrome.” Gallais was widely cited in the early 20th century, and the term persisted into the late 20th century. For example, in 1940, Marks et al reported “adrenal obesity” in a profoundly Cushingoid 10-month-old girl (Fig. 8) with adrenogenital syndrome caused by an adrenal adenoma found at autopsy (51). Their accompanying review of 24 cases of “obesity in children with tumors of the adrenal cortex” found a 21:3 preponderance of girls and a 14:10 preponderance of carcinomas; of the 6 who underwent surgical removal of the tumor, only 2 survived. A case report and literature review in 1946 described 54 children with adrenogenital syndrome caused by virilizing adrenal carcinomas (52), and a 1953 review of adrenogenital syndrome stated the term should only be applied to adult patients with adrenal hyperplasia or adrenal tumors, although some had ovarian tumors (possibly adrenal rests) or apparent polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (53). Fortunately, the term “adrenogenital syndrome” has been abandoned by contemporary endocrinology.

Figure 8.

10½-month-old girl with “adrenogenital syndrome” and “adrenocortical obesity” caused by a 3 cm diameter, 12 g right adrenal adenoma (51) (in the public domain at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/1178993).

Finding the First Adrenal Hormone—Epinephrine

The first adrenal hormone to be isolated, purified, characterized chemically, and synthesized in vitro was epinephrine. Early adrenal investigators had difficulties in differentiating the effects of the medulla and cortex. This important chapter in adrenal history has been reviewed in detail elsewhere (54, 55) and is summarized here.

In 1856 in Paris, Alfred Vulpian (1826-1896) discovered the 2 colorimetric reactions of the adrenal medulla that ultimately identified epinephrine (ferric chloride turns medullary extracts green, whereas iodine turns it “rose-carmine”). He noted this reaction with the adrenals of multiple mammals and birds and that blood from the adrenal vein, but not other veins, gave the same reactions, from which he inferred that the responsible substance is secreted into the circulation (56). Vulpian became dean of the faculty of medicine at the University of Paris and a member of the French Académie des Sciences; a statue of him adorns the Rue de l’École de Médicine in Paris. The reaction of medullary extracts with chromic acid was reported by Bartholdus Werner in 1847 and described in detail by Jacob Henle in 1865 (57); this led to the terms “chromaffin reaction” and medullary “chromaffin cells” introduced by Alfred Kohn in 1902 (58). In 1885, Carl Krukenberg noted that the color reaction of pyrocatechol resembled that the color reaction of adrenal extracts (59), eventually leading to the term “catecholamines.”

In 1894, George Oliver and Edward S. Schäfer reported that intravenous administration of a glycerin extract of calf adrenals caused vasoconstriction and hypertension in dogs (60, 61). In 1908, Schafer said, “Perhaps within the next few years a successor of mine in this lectureship will be able to put before you as much positive knowledge regarding the cortex as we now possess regarding the medulla, the function of which seemed, no more than fifteen years ago, as obscure as that of the cortex appears at present. And with the hope that this obscurity may speedily be removed, I cannot do better than terminate my lecture.” (22). Shortly thereafter, William Horatio Bates, an ophthalmologist in New York, reported that a sheep adrenal extract whitened the conjunctiva of the eye, indicating a vasoconstrictor effect (62) and which others subsequently used as a bioassay for epinephrine. In Philadelphia, Solomon Solis-Cohen suggested that adrenal extracts might be useful therapeutic agents for hay fever and asthma (63, 64), accelerating pharmaceutical interest in the adrenal.

The 3 leading investigators aiming to purify the adrenal hypertensive agent were Benjamin Moore in London, John Jacob Abel at Johns Hopkins, and Otto von Fürth in Strassburg (then in Germany) (65). Abel reacted adrenal extracts with benzyl chloride to prepare an agent that raises blood pressure; he termed this “epinephrin” (no “e”) (66). He proposed the empirical formula C17H15NO4 for “the active principle of the suprarenal capsule” (ie, “epinephrin”) (67). Unfortunately for Abel this was incorrect, as his formula included the benzyl group added in the purification, and benzoylation yielded inactive material. These investigators opposed one another vigorously, preparing different extracts, performing different derivatization procedures, proposing different chemical compositions, and claiming each other’s results were incorrect.

On July 21, 1900, working in the laboratory of Jokishi Takamine on Manhattan’s 109th Street West under a contract with Parke, Davis & Co., Keizo Uenaka (Wooyenaka), Takamine’s lab technician, first purified “adrenalin” (no “e”) from aqueous adrenal extracts furnished by Parke-Davis. Uenaka used procedures similar to those he had used for ephedrine with Nagayoshi Nagai in Tokyo and made the key observation that he had to avoid oxidation (68). When administered to the eye of an unfortunate mouse that had been caught in the lab, the conjunctiva lost its color, indicating vasoconstriction, much as Bates had described. Uenaka then obtained “adrenalin” crystals; he scaled up his procedures, extracting 10 g of crystals from 10 kg of bovine adrenals. On Oct 13, 1900, Uenaka applied a drop of 1:1000 dilution to his own eye and observed vasoconstriction (0.1% epinephrine remains in use today). On Nov 5, 1900, Takamine accepted the suggestion of Dr. Norton Wilson to call the material “adrenalin” (no “e”) and applied for a patent. Takamine published this work in December 1901 (69, 70), estimating the empirical formula to be C10H15NO3. Working at Parke-Davis independently of Takamine, Thomas B. Aldrich, who had worked with Abel, determined the correct formula of C9H13NO3, but says in his paper that his material is the same as Takamine’s (71). Takamine registered the trade name “adrenalin,” and Parke-Davis began sales of “Adrenalin Chloride Solution,” both in 1901. Adrenalin was advertised for “bloodless surgery”, and commercial success was immediate.

In the late 19th century America was awash with “patent medicines” (often termed “snake oil”) that were of dubious value; patents were pursued by charlatans and quacks, not by “real doctors” or “legitimate” pharmaceutical companies. At this time, existing precedent has already drawn the line at patenting natural objects or laws of nature. Takamine had previously obtained US Patent 525 823 for a “Process for making diastatic enzyme,” a yeast preparation that he had devised for the brewing industry but eventually sold as a digestive aid, first marketed in 1895 as “Taka-Diastase” (55). Takamine had licensed this financially successful patent to Parke-Davis. He similarly applied for a US Patent for “adrenalin” in 1901 and was granted US Patent no. 730 175 “Process of obtaining products from suprarenal glands” on June 2, 1903 (72). Adrenaline rapidly became a commercial success, and others marketed equivalent products: Takamine’s patents were challenged in court by HK Mulford Company. In a key ruling by Judge Learned Hand in the US Circuit (District) Court for the Southern District of New York, Takamine’s patents were upheld (73). Judge Hand, who had been on the bench for only 24 months, wrote, “But, even if it were merely an extracted product without change, there is no rule that such products are not patentable. Takamine was the first to make it available for any use by removing it from the other gland-tissue in which it was found, and, while it is of course possible logically to call this a purification of the principle, it became for every practical purpose a new thing commercially and therapeutically.” This foundational (and controversial) precedent affects virtually all pharmaceutical and biotechnology patents to the present day, primarily because “Takamine’s product was patentable as an isolated and purified substance only because purification delivered a transformative difference in utility between the new product and its natural precursor” (74); in other words, the new material was substantially more useful than the natural product, hence it was patentable.

Many early investigators used the name “adrenaline”, as used by Takamine, but this term was copyrighted as a trademark of Parke-Davis, so that “epinephrine” was eventually adopted as the official generic name, with substantial acrimony. Much of the early disagreement among Abel, von Fürth, and Takamine derived from the fact, learned only later, that Uenaka’s crystals of “adrenalin” were contaminated with norepinephrine. In 1906, Ernst Josef Friedmann, who had worked with von Fürth, published the correct chemical structure of epinephrine (75). Hans Meyer and Otto Loewi synthesized “adrenalin” in 1905 but found the pressor effect of the synthetic material to be less than that of the natural product (76); this resulted from the synthesis yielding a racemic mixture of d- and l- optical isomers, whereas the active hormone is only l-epinephrine (77). The epinephrine biosynthetic pathway was proposed by Hermann Blaschko in 1939 (78) and confirmed by others. Epinephrine was distinguished from norepinephrine in the 1940s; the original Takamine “adrenaline” contained about 36% norepinephrine (79).

Finding Steroid Hormones: Early Studies of Adrenal Physiology

Takamine believed he had identified the active principle of the suprarenal gland, and many other early-20th-century investigators also thought the adrenal secreted a single hormone, confounding physiologic work examining the effects of adrenalectomy. In describing the “fight-or-flight” response, Walter Cannon emphasized the sympathetic nervous system and catecholamines but apparently was unaware that adrenocortical hormones also participated (80). Carl and Gerty Cori received a Nobel Prize for describing glycogenolysis (the Cori cycle), which is driven by medullary catecholamines, and noted that adrenalectomy decreased hepatic glycogen (81), but they did not appreciate the role of adrenocortical steroids on carbohydrate metabolism. Glynn had distinguished the functions of the medulla from those of the cortex in 1912 (49), but confusion persisted. Baumann and Kurland may have been first to provide clear evidence for a mineralocorticoid effect by documenting that adrenalectomy (in cats) resulted in hyponatremia and hyperkalemia (82). Rogoff and Stewart showed that adrenalectomized dogs could be kept alive with adrenal cortical extracts (83, 84).

Early efforts to isolate biologically active hormonal substances using extraction procedures with water, saline, or alcohol had been successful with epinephrine (69, 71), thyroxine (85), insulin (86-88) and parathyroid hormone (89) but, as shown by the failure of Brown-Sequard’s testicular extract, had failed with steroids. Frank A. Hartman et al at the University of Buffalo used mild acetic acid and “salting-out” with NaCl to prepare an extract from bovine adrenals that modestly prolonged the life of adrenalectomized cats (90). They concluded: “The hormone of the adrenal cortex has been salted out with NaCl. Cortin is proposed as the name for this substance. Completely adrenalectomized cats injected twice daily with this substance have survived an average of 27.4 days or longer as compared with 5 to 6 days for controls” (90). Philip E. Smith then devised a rat pharyngeal hypophysectomy procedure that spared the pars tuberalis and hypothalamus: the animals stopped growing; the liver, spleen, and kidneys shrunk; prepubertal animals remained prepubertal; and the adrenals, thyroid, and gonads atrophied (91, 92). Smith’s work provided definitive evidence connecting the pituitary to the adrenal and provided important evidence for the role of the hypothalamus (93). In 1930, Swingle and Pfiffner at Princeton (94) and Hartman and Brownell at Buffalo (95, 96) published preliminary reports of the use of lipoidal extraction procedures to prepare adrenocortical material that could sustain the life of adrenalectomized animals and relieve the symptoms of Addison disease; the Swingle-Pfiffner preparation was the first to be used to save an adrenally insufficient, moribund patient at the Mayo Clinic (97). Swingle and Pfiffner improved their preparation somewhat (98, 99), and this preparation was then manufactured and distributed by Parke-Davis under the brand name Eschatin. A few papers describe successful treatment of Addison disease (100) and possible CAH (101) with this preparation, but it was of unclear composition and low potency in vivo (102) and in vitro (103).

Noting that “the sodium content of the blood of patients suffering from Addison’s disease is decreased, as it is in adrenalectomized cats,” Robert F. Loeb at Columbia University showed that oral administration of saline alone extended the life of a patient with Addison’s disease (104), but the basis of this effect remained unclear until aldosterone was isolated 20 years later. George Harrop at Johns Hopkins Hospital similarly noted high potassium and low sodium in animals and patients with adrenal insufficiency. At the Mayo Clinic, patients with Addison’s disease were given a high-sodium, low-potassium diet; some patients were stabilized for months on this diet.

Harvey Cushing (105) described pituitary tumors associated with what we now call Cushing syndrome and noted that many of the clinical features observed resembled those seen in patients with adrenal tumors, and some of the autopsy reports mentioned adrenal enlargement, but the pituitary-adrenal linkage was unclear. His concluding paragraph clearly centers on the pituitary: “While there is every reason to concede, therefore, that a disorder of somewhat similar aspect may occur in association with pineal, with gonadal, or with adrenal tumors, the fact that the peculiar polyglandular syndrome, which pains have been taken herein conservatively to describe, may accompany a basophil adenoma in the absence of any apparent alteration in the adrenal cortex other than a possible secondary hyperplasia, will give pathologists reason in the future more carefully to scrutinize the anterior-pituitary for lesions of similar composition.” It was apparent that the pituitary did not control all adrenal function, because adrenalectomy killed animals more rapidly than hypophysectomy (106), but our contemporary understanding of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis developed much later [reviewed in (107)]. Menkin observed an anti-inflammatory effect of adrenal extracts in 1940 but thought this reflected a reduction in capillary permeability (108). In Montreal, Hans Selye reported that rats receiving “nocuous agents” (exposure to cold, surgery, spinal transection, sublethal doses of drugs or formalin) exhibited a 3-phase stress response that included adrenal hyperplasia and involution of the thymus—the discovery of glucocorticoid action (109). He integrated these and other findings into the conceptualization of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, defined what we now know as “the stress response,” coined the terms “mineralocorticoid” and “glucocorticoid,” and emphasized that both classes of steroids were needed for survival (110). Thus, chemical identification of adrenocortical factor(s) was needed.

Finding Steroid Hormones: Early Studies of Adrenal Steroid Chemistry

Heinrich Otto Wieland and Adolf Otto Heinrich Windaus will always be remembered together. These German chemists were personal friends and colleagues and won sequential Nobel Prizes in Chemistry in 1927 and 1928 (both awarded in 1928) for work with sterols (111, 112). Both also openly resisted the Nazi regime and refused to sign the Nazi loyalty oath in 1933 [“Bekenntnis der Professoren an den Universitäten und Hochschulen zu Adolf Hitler und dem nationalsozialistischen Staat” (the “Vow of allegiance of the Professors of the German Universities and High-Schools to Adolf Hitler and the National Socialistic State”)] but were shielded from Nazi persecution by their status as Nobel laureates (113). Wieland was a professor in Munich and in Freiburg who received the Nobel “for his investigations of the constitution of the bile acids and related substances” (111). Windaus, a professor in Göttingen, received his Nobel “for the services rendered through his research into the constitution of the sterols and their connection with the vitamins” (specifically, vitamin D) (112). Illustrating the difficulty of determining complex chemical structures with the tools available in the 1920s, Wieland and Windaus published structures for cholesterol, but both got it wrong (Fig. 9). Rosenheim and King reported the correct structure in 1932 (114).

Figure 9.

Structures proposed for cholesterol. Left, structure according to Heinrich Wieland (111) (in the public domain at https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/wieland-lecture.pdf). Center, structure as proposed by Adolf Windaus (112) (in the public domain at https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/windaus-lecture.pdf). Right, structure as proposed by Rosenheim and King (114).

In 1933, Carl von Ossietzky, the German author, pacifist, and publisher of the political journal The World Stage was arrested by the Nazis and imprisoned at Esterwegen prison and then at the Sonnenburg concentration camp (where he died of tuberculosis in 1938) for documenting German rearmament in violation of the Treaty of Versailles, beginning during the Weimar Republic (115). In response, Hitler ordered all Nazis to refuse Nobel Prizes, much to the dismay of many scientists who viewed themselves as candidates (and had signed the Nazi loyalty oath). In 1939, Windaus’s former student Adolf Freidrich Johann Butenandt (Nazi Party member #3716562) and Leopold Ruzika (a Swiss/Croatian) were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for isolating estrone, androstenedione, and progesterone. Butenandt apparently lacked his former mentor’s ethics. On orders from the Reich, Butenandt declined the prize and instead was given the infamous “War Merit Cross” by Hitler in 1942 (among the approximately 100 other Nazis so recognized were Adolf Eichmann, Josef Mengele, and Albert Speer). Ruzika delivered his Nobel lecture in 1945, after World War II (116). Butenandt appealed to the Nobel Committee and was officially listed as a Nobel laureate in 1949 and received the diploma and medal but no prize money, and he did not deliver a Nobel lecture. Butenandt directed the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biochemistry from 1937 to 1945, directing biochemical research for Germany’s war effort (115). After the war, Butenandt returned to science and attempted to rehabilitate his reputation: with Karlson he isolated and determined the structure of the insect steroid hormone ecdysone (117).

Major advances in steroid chemistry were made by Tadeus Reichstein, whose family escaped the pogroms in Russian-occupied Poland and eventually settled in Switzerland. Reichstein became a Swiss citizen and received his doctorate from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zürich in 1922, working under Hermann Staudinger (1953 Nobel Prize in Chemistry) and later under Leopold Ruzicka (1939 Nobel Prize in Chemistry) (Figs. 10, 11). Much of Reichstein’s biography has been recorded by Miriam Rothschild, with whom he later isolated insect cardioglycosides (118). Working with his lifelong assistant Joseph von Euw, Reichstein first achieved prominence in organic chemistry by isolating aromatic components of coffee in 1931 (119) and then by devising what is now known as “the Reichstein Process” for synthesizing vitamin C (first isolated in 1928 by Albert Szent-Gyorgyi) (114, 120). His work with steroid hormones at ETH was well underway (121, 122) supported by the Dutch pharmaceutical company NV Organon, but Ruzicka, the director at ETH, had a contract with CIBA that required that patent rights concerning steroid research had to be assigned to CIBA; Reichstein’s contract with Organon excluded this, so Reichstein left in 1938 to become chair of the Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry in Basel. From 1938 to 1950, Reichstein published hundreds of papers describing the isolation, chemical characterization, and synthesis of over 2 dozen steroids (123). Prior work to identify, purify, and isolate hormones, such as epinephrine, thyroxine, insulin, and parathyroid hormone, had been facilitated by their abundant intracellular storage, but this is not the case for steroids. Steroidogenic cells do not produce steroids and store them for later release; the rate of steroid release is determined by steroid synthesis so that the amount of steroid in an adrenal cortex is surprisingly low (as described later, this ultimately led to the discovery of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein in the 1990s). Starting with ~500 kg adrenals from 10 000 cattle (provided by NV Organon, whose main business was extracting bovine insulin), Reichstein isolated and determined the structures of 28 adrenal “corticoids,” only 5 of which had biological activity. In 1953, 3 years after winning the Nobel, in collaboration with Sylvia Simpson and James Tait, he isolated aldosterone (124, 125).

Figure 10.

Structures of the 28 steroids that were chemically characterized by Reichstein between 1938 and 1949 (123) (in the public domain at https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/reichstein-lecture.pdf).

Figure 11.

Left, Tadeus Reichstein (1897-1996) as a well-dressed graduate student at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zürich, 1923. From (118); reproduced courtesy of Schweitzerische Stiftung für die Photographie. Right, The Kendall lab, 1948, with the principal investigators of the use of cortisone for rheumatoid arthritis. Left to right: Charles H. Slocumb, Howard F. Polley, Edward C. Kendall, and Philip S. Hench [from (126), reprinted with permission].

The preparation of “cortin” by Swingle and Pfiffner (94, 98, 99) spurred great interest in adrenal steroids in the United States. Most notably and contemporaneously with Reichstein, Edward C. Kendall at Mayo Clinic was trying to isolate adrenal steroids in the 1930s. Kendall was an established figure: he had purified thyroxine in 1915 (127) and had isolated glutathione and determined its structure (128), but his attempts to determine thyroxine’s structure failed. Harington and Barger at University College London published the correct structure in 1927 (129). In 1929, Albert Szent-Gyogyi, who had isolated vitamin C, was a visiting professor at Mayo for 8 months, where he prepared vitamin C from bovine adrenals. It was at this time that the Swingle-Pfiffner adrenocortical extract (“Eschatin”) had been used by Leonard G. Rowntree, chair of medicine at Mayo, to help save an adrenally insufficient, moribund patient (97). As related by Ingle in his obituary for Kendall for the National Academy of Sciences (130), Rowntree then urged Kendall to pursue the preparation of adrenal extracts, rather than just making cortin, Kendall decided to pursue the isolation of its active principle. Kendall made an arrangement with Parke-Davis to receive about 900 pounds of bovine adrenal glands each week, Kendall would separate crude epinephrine for Parke-Davis and retain the “left-over” cortical material to prepare the cortin that was used to treat Mayo’s Addisonian patients who had failed treatment with their high-sodium, low-potassium diet; this was also the starting material for his efforts to purify the cortical hormone. Like others in the field, Kendall initially thought there was only 1 adrenocortical hormone. Many adrenal steroids will cocrystalize and appear to represent a single compound, but the work of Reichstein in the 1930s showed this was not the case; by about 1934, most investigators acknowledged that the adrenal secreted multiple biologically active steroids. By 1935, 4 groups were trying to isolate adrenal compounds: Kendall at the Mayo Clinic, JJ Pfiffner who had moved from Princeton to join Oskar Wintersteiner at Columbia University (131), Cartland and Kuizenga working at Upjohn, Inc. (132), and Reichstein in Zurich. By then it was known that adrenocortical secretions influenced carbohydrate metabolism, virilization, and salt and water balance; it was logical to presume that different steroids exerted different effects, but only small amounts of the individual steroids could be prepared, and the animal bioassays then available were insufficiently sensitive. Although there was rivalry among the groups, they also shared samples and information. Reichstein and Wintersteiner were superior chemists, but they lacked assays for biological activity.

In 1934, Dwight J. Ingle (president of the Endocrine Society, 1959-1960) finished his doctorate (in psychology) at the University of Minnesota after joining Kendall’s lab in 1932. Ingle had developed an assay to measure muscular work in anesthetized rats: a 100-g weight was affixed to the gastrocnemius muscle and was stimulated electrically to lift the weight 3 times per second. Normal rats could do this for >14 days, but the work capacity of an adrenalectomized rat fell below that of sham-operated controls within 2 hours, and muscular responsiveness was lost within a day (133). Ingle developed a modified 24-h assay of adrenal cortical extract that was sensitive, fast, and reliable. Replacement with epinephrine was of no avail, but Kendall’s cortical extract permitted nearly complete recovery, in a dose-response fashion: there was now a viable laboratory bioassay for glucocorticoid action (134). Although Kendall’s first crystalline adrenocortical preparation (announced with much fanfare in 1934) (135) was inactive, they were on track. Kendall’s “compound E” (later identified as cortisone) was active in the muscle work test in late 1935 (136); Wintersteiner and Pfiffner (131) and Reichstein (122) had also isolated compound E but were unaware of its biological activity. Kendall then converted compound E to a diketone, and Fred Conrad Koch demonstrated this derivative had androgenic activity that “was one-sixth to one-fourth as active as androsterone in stimulating comb-growth in the capon” (136). Thus, independently and by different tactics, the different groups now knew that compound E was a steroid. Ingle left Mayo for the University of Pennsylvania, where he used his assay to measure and compare the work capacity of multiple, structurally characterized steroids (137).

Steiger and Reichstein prepared 11-desoxy-corticosterone (DOC) in 1937 (138), and several groups showed it could sustain the life of adrenalectomized animals or patients with Addison’s disease (139-142). Kendall’s other compounds, termed “A,” “B,” “E,” and “F,” were 11-oxygenated; Hans Selye called the 11-hydroxy steroids “glucocorticoids” and the 11-deoxy steroids “mineralocorticoids” (110); like many oversimplifications, this one contained a nub of truth. Kendall’s operational alphabetical names were applied before the structures were known; “A” was 11-dehydrocorticosterone, “B” was corticosterone, “E” was 17-hydroxy-11-dehydrocorticosterone (cortisone), and “F” was 17-hydroxy corticosterone (cortisol). Wintersteiner and Pfiffner found that noncrystalline adrenocortical extracts were much more potent than Kendall’s compound E in sustaining the life of adrenalectomized animals (131), and only miniscule amounts of DOC were found in adrenal extracts, suggesting that DOC was not the life-maintaining (salt-retaining) adrenocortical hormone. Much of that activity remained in what Kendall called “the amorphous fraction,” which was later shown to contain aldosterone (124, 125).

With the synthesis of DOC, much of the fire went out of the competition to isolate a clinically important adrenocortical hormone; many major players, including Pfiffner and Wintersteiner and Cartland and Kuizenga, left the field. Kendall remained committed. World War II essentially ended expensive animal experimentation but also stimulated adrenal research. It was rumored that Germany was procuring beef adrenals in Argentina and preparing an adrenocortical extract that permitted Luftwaffe pilots to fly to higher altitudes (130). The rumors about Argentine adrenals were false, but the US military considered that adrenocortical extracts might be useful in treating traumatic shock and surgical shock and might improve soldiers’ responses to stressors. The medical research division of the Office of Scientific Research and Development gave high priority to the synthesis of Kendall’s compound A as a precursor to making the more active compound F (cortisol). Several pharmaceutical groups were involved, and communications with Reichstein were maintained; by the end of the war, Merck and Co. had prepared ~100 g of compound A, but animal studies failed to show utility in hypoxia or surgical or traumatic shock, and clinical studies showed little value in Addison’s disease. Most of the chemists involved quit the project (130). Nevertheless, Kendall convinced Merck to continue work toward compound E, and, by 1948, they had prepared ~9 g of compound E; by this time Merck had invested over $14 million on the project. With no proven medical use, Merck was ready to “pull the plug” on compound E.

Philip Showalter Hench was the Mayo Clinic’s first rheumatologist; he had been recruited by Leonard G. Rountree and was appointed head of the new Division of Rheumatology in 1926 at age 30. In 1929 he began to take interest in how the symptoms and clinical courses of arthritis differed in patients who also had other conditions. Hench was a brilliant clinical observer who could see patterns in disease that others had not. He first reported symptomatic improvement in 16 patients with chronic rheumatoid arthritis who also had hepatitis with jaundice (most caused by the hepatotoxicity of the analgesic drug cinchophen) (143). In 1938, he reported 31 more cases; he noted that the degree of symptomatic remission correlated with the degree of jaundice rather than with the cause of the liver disease and that administering bile or bile salts did not reproduce the analgesic effect (144). He also noted that arthritis and allergies improved in pregnant patients and that the benefits persisted long after parturition or the remission of the liver disease, suggesting that the salutary effects were not mediated by metabolites of bilirubin. Hench was a student of medical history, noting dozens of earlier reports about spontaneous temporary remission of arthritis associated with hepatic injury or pregnancy, but none of the earlier reports pursued the observation, considered similarities and differences among the reports, or tried systematic interventions (145). He postulated that the effects were due to an unknown, endogenous “substance x” that was made in both men and women (144).

Kendall and Hench began collaborating in about 1938; in 1941 they agreed to try compound E for arthritis when sufficient material became available. They tried “cortin” in 3 patients, with negative results (146). Hench’s military service in World War II and the high cost and difficult preparation of compound E delayed the planned trial. In September of 1948, compound E became available from Merck and was injected into a severely affected arthritic patient, yielding a dramatic improvement. The clinical study was expanded; almost all arthritic patients so treated went into a remission that lasted so long as the treatment was continued. Intramuscular adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) yielded similar results. This produced great excitement at Mayo, but caution initially prevailed, and the results remained confidential for several months. There were concerns that the doses used to suppress the symptoms of arthritis were large, and it was suspected that prolonged high-dose treatment would cause Cushing’s syndrome, cause adrenal atrophy, or inhibit the pituitary’s ability to control adrenal secretions normally (147). Nevertheless, the results became known to the press, and great excitement ensued about a “cure” for arthritis. Hench, Kendall, and their collaborators (Fig. 11) described their basic work and clinical results in great detail, cautioning that compound E was experimental, that it was not a cure, and that overdose effects were likely (146), but the press and the public didn’t understand or care. A movie clip of a wheelchair-bound arthritic patient arising and walking after 3 days of intramuscular cortisone (100 mg/d) was seen widely, and there was tremendous pressure on the Mayo Clinic and Merck to provide compound E. Kendall, Reichstein, and Hench equally shared the 1950 Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology (123). In Hench’s speech at the Nobel banquet, he acknowledged Kendall and Reichstein by saying “Perhaps the ratio of one physician to two chemists is symbolic, since medicine is so firmly linked to chemistry by a double bond.” Many chemists received Nobels for work with sterols (Wieland, Windaus, Butenandt, Ruzika, Kendall, Reichstein), but Hench’s unique contributions vaulted steroids from an esoteric branch of organic chemistry to the very center of medicine and pharmacology.

With the advent of the clinical use of cortisone and the identification of the structures of the “alphabet soup” of compounds identified by Reichstein and Kendall, the golden age of steroid chemistry was nearly over. Only 1 major question remained—the nature of the life-sustaining component (sometimes called “electrocortin”) that powerfully influenced electrolyte balance presumably an 11-desoxy-steroid in Kendall’s “amorphous fraction” of adrenal extracts. Kendall did not pursue this question, but Reichstein and his colleagues did. Simpson and Tait developed a sensitive bioassay that permitted the crystallization of 21 mg of electrocortin from 500 kg of bovine adrenals (124) and, with the subsequent determination of its structure, the last major biologically active steroid, aldosterone, had been discovered [reviewed in (148)], greatly aided by the new technique of paper chromatography (149).

History of CAH Due to 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency

To most endocrinologists, the term “congenital adrenal hyperplasia” means “steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency” (21OHD), but in fact there are multiple forms of CAH; these are attributable to mutations in different genes and to variations in severity and clinical phenotypes of mutations within single genes. We consider the history of each form separately. Lipoid CAH is discussed in the section titled “The Role of Corticotrophin (ACTH) in Regulating Adrenal Steroidogenesis.”

Clinical Investigation

Understanding of CAH as a distinct entity developed fairly rapidly in the 1930s; several cases were reported, and Marrian and Butler established that the urinary steroid pregnane-3,17,20-triol (pregnanetriol) was elevated in all cases of adrenal virilism (both CAH and virilizing adrenocortical carcinomas) (150-152), while others, notably Russell E. Marker, identified multiple steroids in the urine of pregnant women (153). Marker subsequently achieved fame and fortune by inventing the “Marker Degradation” for preparing progesterone from diosgenin extracted from Mexican Dioscorea root, the origins of the oral contraceptive industry (which will not be covered here). Fifteen years later, Bongiovanni et al showed that urinary pregnanetriol was the hepatic metabolite of 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17OHP) (154). However, the early measurements urinary pregnanetriol required huge volumes of urine (>1 week’s excretion) and was technically demanding, hence its use as a marker for CAH had to await technical advances.

The 1940s saw the first scientific clinical investigations of CAH, reported by 2 of the founding fathers of pediatric endocrinology, Lawson Wilkins (1894-1963) at Johns Hopkins University and Nathan B. Talbot (1909-1994) at Massachusetts General Hospital. Talbot was 15 years younger than Wilkins, but their research careers with CAH began contemporaneously in the late 1930s. By this time, it was generally understood that the adrenal made several hormones that did different things: DOC acted on electrolyte balance, corticosterone (and later compound E) raised blood sugar via gluconeogenesis, and as-yet-undescribed hormones could result in virilization. Working under Allan M. Butler (chief of the Children’s Medical Service and staff physician in charge of the Chemical Laboratories at Massachusetts General Hospital), Talbot co-authored a case report of probable CAH, published in December 1939 (101); that report mentions Wilkins’ oral presentation of a similar case, published in March 1940 (155). The case reported by Butler and Talbot was a male infant followed from age 2 weeks to 20 months with skin pigmentation, enlarged genitalia (but small testes), a propensity to “collapse” with associated hyponatremia and hyperkalemia if fluids or salt were withheld, urinary excretion of large amounts of “estrogens and androgens,” and successful maintenance with added salt and bicarbonate (101). Treatment with the Parke-Davis “Eschatin” adrenal extract was ineffective, but the addition of 5 g of sodium chloride and a charcoal adsorbate of adrenal cortical extract containing “3 rat units” daily resulted in weight gain without edema and normalization of the serum Na and K, but the adrenal extract without added sodium was ineffective (the “rat units” probably refer to Ingle’s muscle-work bioassay, described earlier). The patient could be maintained with parenteral cortical extract from Upjohn “providing 4 rat units daily.” A diet supplemented with sodium chloride and sodium bicarbonate yielded moderate weight gain and improved levels of sodium and potassium.

Lawson Wilkins had been in the private practice of pediatrics in Baltimore for 14 years before establishing the world’s first pediatric endocrine clinic at Johns Hopkins in 1935. Personal biographies of Wilkins have been published by his daughter (156) and by his former trainee and colleague Claude Migeon (157); a summary of his career is contained in Delbert Fisher’s history of pediatric endocrinology (158). Wilkins was at the forefront of efforts to link anatomical adrenal hyperplasia with functional adrenal insufficiency and androgen excess. Wilkins encountered a 31/2-year-old boy with “marked development of his secondary sex organs” who had developmental delay, mental retardation, low serum sodium, and a profound craving for salt, a clinical point he emphasized in his first report of this child (155). Wilkins’ more detailed report of this early case of CAH combined astute clinical observation with then-new bioassays of steroids (159). In addition to the salt craving, Wilkins reported polyuria, polydipsia, and a deceased 5-week-old “female pseudohermaphrodite” sibling. His “parents noticed at birth that his penis and scrotum were unusually large”; he developed acne at 5 months, pubic hair at 15 months, and asymmetric testicular enlargement “several months later.” He was thin, tall, muscular, generally pigmented (including the gums), and had asymmetric pubertal-sized testes; blood pressure was 90/50 (Fig. 12). Laboratory data showed normal glucose, calcium, and phosphorus; hemoglobin of 16.3 g/100 ml; white count of 19 000; and elevated nonprotein nitrogen. He died unexpectedly on day 6 of hospitalization. “Immediately after his death blood was taken by cardiac puncture for chemical studies, which showed serum sodium 111 m.eq. per liter.” Autopsy showed grossly enlarged adrenals (total weight 27 g) with “accumulation of large cells” “characteristic of the androgenic type.” The testes contained masses containing cells “similar to those described in the adrenals” but without Leydig cells (ie, probable testicular adrenal rest tumors). A castrate rat bioassay for urinary androgens showed 30 IU per day, the same as that of a normal adult man. Alcohol extracts of 6.3 g of testicular tissue yielded 5 IU of androgen, whereas 31 g of normal adult testicular tissue yielded no detectable androgen. Using the cock’s comb bioassay for androgens initially described in 1849 by Arnold Berthold (160), an extract of 3.5 g of adrenal tissue “failed to show measurable androgen,” but extract from 2 g of adrenal tissue “caused growth when rubbed into the comb of a 11-day-old-chick over a period of 7 days.” Wilkins’ discussion proposes that “female pseudohermaphrodites” have hyperplasia of the “prenatal zone” of the adrenal and that virilizing tumors contained the same tissue, indicating that this “androgenic zone” is distinguished from “the electrolyte-controlling portions of the cortex, the ‘interrenal cells.’”

Figure 12.

Patient with congenital adrenal hyperplasia reported by Wilkins et al (159), with scrotal enlargement suggesting the presence of testicular adrenal rest tumors.

A friendly rivalry arose between Boston and Baltimore. Boston had all the advantages—a larger clinical base, outstanding biochemistry, and the world’s best endocrinologist: Fuller Albright. Talbot described 12 additional patients with CAH, focusing on 17-ketosteroid (17KS) excretion and contrasting them with patients with virilizing adrenocortical carcinomas (161). Talbot’s 1943 paper about a patient with Addison’s disease (probably due to autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1) also reported increases in urinary 17KS in CAH and showed that unilateral adrenalectomy was not valuable in CAH (162). Albright distinguished adrenogenital syndrome (CAH) from Cushing syndrome in 1943 (163). Debate concerning the roles of the pituitary and adrenal in Cushing syndrome persisted (164) until about 1950, when Bauer concluded that both the pituitary and the adrenal can separately cause “the so-called Cushing’s syndrome” and that the term “Cushing’s disease” be reserved for the pituitary form (165).

Talbot’s principal interests were in practical steroid chemistry: he worked with George Langstroth at MIT to devise apparatus for determining urinary androgens in clinical laboratories (166) and refined existing colorimetric assays for 17KS (161, 167, 168) and corticoids (168). However, Talbot’s 1950 paper describing the long-term follow-up of the patient he had described with Butler et al in 1939 added no new clinical, physiological, or chemical insights (169). And despite their shared institutional affiliation and interests, Talbot and Albright collaborated only once, correlating urinary “11-oxocorticosteroid-like substances” (17-hydroxycorticosteroids) and the apparent activity of what they called the “S-hormone” (designating the “sugar-active” adrenal hormone(s), cortisol) (170). Fuller Albright only became involved in CAH in 1950.

In 1949, Zuelzer and Blum proposed that “the combination of cortical insufficiency, masculinization, and diffuse adrenal hyperplasia forms a distinct anatomic-physiologic entity” (171). Their literature survey found 9 papers published from 1937 to 1945 reporting 17 cases, including those reported by Wilkins (155) and by Butler (101) cited earlier. They presumed the disorder to be fairly common as they found 4 cases among 1068 autopsies of children 0 to 13 years old, with most cases in infancy. The genital virilization in the females was typical of the congenital form of the adrenogenital syndrome “in which excessive production of androgens by the fetal adrenals is thought to inhibit differentiation of female structures and to stimulate growth of the sex organs along male lines of development.”

The state of understanding of adrenal pathophysiology just before CAH was first treated with cortisone is vividly shown by the presentations by Talbot and by Wilkins at the 1949 meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the following question and answer dialogue (172). Talbot reviewed steroid structure-function relationships and their physiologic actions. He described DOC as the principal “Na-K hormone,” 11-oxo-corticosteroids as the “sugar-fat-nitrogen” hormone(s) active in carbohydrate metabolism, and an “androgenic, or protein anabolic ‘N’ hormone” that is metabolized to 17KS. He speculated about their importance in normal physiology but did not address disease states. Wilkins discussed (i) “adrenogenital syndromes,” distinguishing congenital (CAH) from “postnatal” (adrenal tumors), and (ii) “Cushing’s syndrome,” which he described as of hypothalamic, pituitary, or primary adrenal origin, and correctly listed the apparent steroidal abnormalities in each. His description of the anatomy of girls with CAH is quite contemporary; he erred in saying that CAH is more common in girls than boys but correctly suggested that boys may be under-ascertained because of infant death and lack of distinct early anatomic findings. Notably, he distinguished CAH from precocious puberty based on testicular enlargement (an important point of the physical exam that many physicians still overlook today). He illustrated infants treated successfully with DOC or “adrenal cortical extract” and discussed the differential diagnosis of the various forms of hyperandrogenism. This paper is remarkable in showing Wilkins’ early understanding of adrenarche, presumed adrenal insufficiency in infants, and the proper management of “pseudohermaphroditism” in CAH, issues that remain under investigation today. At about the same time he showed that adrenalectomy had salutary effects in CAH but that its efficacy was severely limited by then-inadequate adrenal replacement therapy (173).

The isolation and synthesis of cortisone and its success in treating Addison’s disease and arthritis quickly suggested use in CAH. Wilkins saw the potential of Kendall’s compound E, but Talbot had become involved in nonsteroidal areas of endocrinology and was not involved in the revolutionary treatment of CAH with cortisone. By 1949, Wilkins was clearly the leading authority on CAH, but the Boston-Baltimore rivalry remained, as Fuller Albright and his fellow Frederic C. Bartter at Massachusetts General Hospital entered this academic contest. Fuller Albright had an unmatched career of clinical and basic endocrine investigation in the 1930s and 1940s, mostly in bone metabolism, but his progressive Parkinson’s disease impaired him severely in the 1940s. Wilkins and others had successfully treated salt loss with deoxycorticosterone but failed in treating CAH with ACTH or testosterone (174). Wilkins then published a brief “Preliminary Report” in the Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital describing suppression of urinary 17KS in 1 CAH patient treated with 100 mg cortisone daily (175); the paper was received on Feb 13, 1950, and published in April; the Bulletin did not use external review. Wilkins begins: “Unsuccessful attempts have been made by us (unpublished) to suppress the secretion of 17-ketosteroids in patients with this disorder by the administration of steroids, such as 17-ethyl testosterone, 17-vinyl testosterone, 17-methyl androstenediol and 17-methyl androstanediol, which have a chemical structure similar to that of androgens but possess relatively little androgenic activity” and concludes that cortisone “suppressed the secretion of adrenal hormones responsible for the urinary excretion of 17KS” (175). Wilkins did not mention the pituitary or ACTH. At the same time, Bartter presented an abstract on May 1, 1950, at the annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Investigation describing his and Albright’s unsuccessful treatment of CAH with ACTH but successful treatment with cortisone. They concluded: “These findings suggest that the adrenogenital syndrome results, not from an abnormal pituitary stimulation of the adrenal, but from an abnormal adrenal response to a normal pituitary” (176). Both groups followed their preliminary reports with full papers. Wilkins’ paper was received for publication on Nov 21, 1950, and was published in Jan 1951 (177); Bartter’s paper was received on Nov 2, 1950, and was published in Feb 1951 (178). Each group cited the other’s preliminary report. Wilkins began by describing unsuccessful treatments with steroids “which have a chemical structure similar to that of androgens but possess relatively little androgenic activity” before trying cortisone. Wilkins correctly concluded: “We suggest that the action of cortisone is to suppress the output of pituitary adrenocorticotropin, thereby causing marked diminution of the secretion of the pathologic adrenals” (177). Bartter and Albright approached the problem by considering the similarities and differences between CAH and Cushing’s syndrome and concluded with a diagram of the correct physiology (Fig. 13) (178). Thus Wilkins and Bartter/Albright deserve equal credit for proposing the treatment of CAH with cortisone. Following the reports of successful treatment of CAH with cortisone, Wilkins exerted tremendous effort to optimize its use and investigate the effects of cortisone on sexual development, growth, electrolyte metabolism, hypertension, and testicular development (179-183). These detailed metabolic balance studies established the therapeutic approach to CAH that largely remains in effect today (184, 185). Talbot also made important further contributions, showing that both cortisone (186) and diethyl stilbesterol (187) could cause growth arrest. Albright was rendered vegetative by unsuccessful chemopallidectomy for his Parkinson’s in 1956, and Bartter went on to describe syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone ADH release but did not follow up on the work with CAH.

Figure 13.

The physiology of congenital adrenal hyperplasia, described by Bartter et al in 1951 (178) (in the public domain at https://www.jci.org/articles/view/102438/pdf). In these diagrams, “S” does not refer to Reichstein’s compound S (11-deoxycortisol) but to the then-unknown steroid active in sugar metabolism (now known to be cortisol); “N” refers to the then-unknown adrenal androgen that influences nitrogen retention (now known to be 11-keto-testosterone). In the right-hand panel, “E” refers to Kendall’s compound E (cortisone).

What Is Disordered in CAH?

Both Wilkins and Bartter/Albright assessed responses of patients with CAH to treatment with cortisone by measuring urinary 17KS, but they did not know they were dealing with steroid 21OHD. Before the biochemical lesion could be identified, a general knowledge of the adrenal steroidogenic pathways was needed. The 30 steroids identified by Reichstein and others could, hypothetically, be arranged into several different potential steroidogenic pathways. Oscar Hechter and Gregory Pincus at the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, devised the novel procedure of isolating bovine adrenals with their arteries and veins intact, then infusing a potential precursor into the adrenal artery and measuring the steroids in the venous effluent (188, 189). With the new availability of radiolabeled steroids, the specificity of the conversions was assured (190). When adrenals were perfused with 14C-labeled acetate, cholesterol, or progesterone, ACTH stimulated incorporation of 14C into steroid products only when cholesterol was the precursor; ACTH had no effect on conversion of acetate to cholesterol (191). This study established that ACTH acts on the conversion of cholesterol to progesterone. However, their data with 14C-acetate suggested the existence of steroidogenic pathways that do not involve cholesterol; later studies showed that this is not the case. With this powerful new technique, Hechter and Pincus proposed the first steroidogenic pathways (192, 193) (Fig. 14). These and other studies were often inconsistent and difficult to apply to measurements from human patients, as early investigators did not anticipate the significant differences in the enzymes and pathways of steroidogenesis among various mammals, especially human beings.

Figure 14.

The first steroidogenic pathway, as proposed by Hechter and Pincus in 1954 (193); reprinted with permission. The pathway is largely correct, as acetate is converted to cholesterol through a complex, 30-step pathway, represented by “x.” However, none of the intermediates in that pathway is converted to progesterone or other steroids without first being converted to cholesterol.

Alfred M. Bongiovanni (1921-1986) trained in steroid chemistry with William Eisenmenger at Rockefeller (194, 195) and clinically with Wilkins at Hopkins, where he became an assistant professor and worked independently, establishing the steroid assay lab at Johns Hopkins (196, 197). In 1955 he showed that different patients with CAH had different steroidogenic lesions: most accumulated pregnanetriol in their urine, indicating an inability to convert 17OHP to compound F(ie, 21OHD), but 1 patient had hypertension and “large quantities of Reichstein’s compound S (11-deoxycortisol) and its metabolites” in blood and urine. This was the first steroidal evidence for a variant form of CAH [11-hydroxylase deficiency (11OHD)] and permitted the drawing of the first truly modern steroidogenic pathway (Fig. 15) (198, 199). In a footnote he adds, correctly, “The hypertension described as a complication of the adrenogenital syndrome may be due to the secretion of desoxycorticosterone.” Bongiovanni followed up on this work with even more sophisticated steroidal analyses showing that (i) CAH is due to a lack of “21-hydroxylase,” (ii) that normal and 21OHD adrenals have an “11-hydroxylase,” and (iii) 21-hydroxylation precedes 11-hydroxylation in the human adrenal (200).

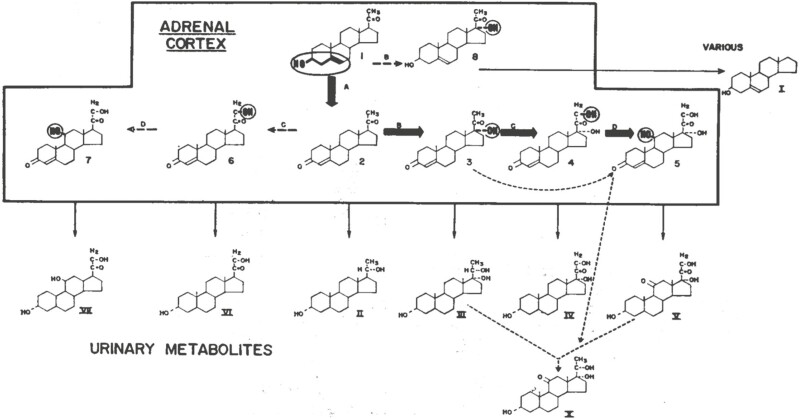

Figure 15.

Bongiovanni’s steroidogenic pathway from 1963 (199). Cortisol is (5) and corticosterone is (7). The various enzymes, A (3 β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase), B (17-hydroxylase), C (21-hydroxylase), and D (11-hydroxylase) are illustrated, and their sites of action are shown by the encircled heavy type. The most common form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia is characterized by a lack of 21-hydroxylase (C) and hence an accumulation of 17-hydroxyprogesterone (3) with the excretion of large quantities of the latter’s reduced metabolite, pregnanetriol (III) (reprinted with permission; ©1963 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved).