Abstract

Background

Although interest in nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infection has increased in the last decades, published data vary according to different geographical areas, diagnostic facilities and quality of study design. This study aims at assessing both prevalence and incidence of NTM infection and NTM pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) among adults with bronchiectasis, to describe patients’ characteristics, therapeutic options and clinical outcomes.

Methods

Bronchiectasis adults who had been tested for NTM were enrolled at the Bronchiectasis Program of the Policlinico Hospital in Milan, Italy, from 2016 to 2018.

Results

Among the 373 patients enrolled, 26.1% had at least one respiratory sample positive for NTM and 12.6% reached a diagnosis of NTM-PD. Incidence rates for NTM infection and NTM-PD were 13 (95% CI 10–16) and 4 (95% CI 2–6) per 100 person-years, respectively. The most prevalent NTM species causing NTM-PD were M. intracellulare (38.3%), M. avium (34.0%), M. abscessus (8.5%) and M. kansasii (8.5%). Once treatment for NTM-PD was initiated, a favourable outcome was documented in 52.2% of the patients, while a negative outcome was recorded in 32.6%, including recurrence (17.4%), treatment failure (10.9%), re-infection (2.2%) and relapse (2.2%). Treatment halted was experienced in 11 (23.9%) patients.

Conclusions

NTM infection is frequent in bronchiectasis patients and the presence of NTM-PD is relevant. The low success rate of NTM-PD treatment in bronchiectasis patients requires a call to action to identify new treatment modalities and new drugs to improve patients’ outcomes.

Short abstract

The low success rate of NTM pulmonary disease treatment in bronchiectasis patients necessitates a call to action to find novel treatment modalities and new drugs to improve outcomes https://bit.ly/3aNcBVd

Introduction

Bronchiectasis is a chronic respiratory disease characterised by a clinical syndrome of cough, sputum production and recurrent bronchial infection, along with an abnormal and permanent dilatation of the bronchi confirmed by chest high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) [1]. Chronic airway infection plays a key role in the pathogenesis and progression of the disease [2]. While Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Haemophilus influenzae are the most prevalent bacteria detected in bronchiectatic airways, other pathogens including fungi, mycobacteria and viruses can cause a chronic infection [3, 4].

Over the last decade, nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) have been progressively recognised as relevant pathogens in bronchiectasis [3, 5–9]. Data on their prevalence in bronchiectasis are scarce, varying according to different geographical areas and available diagnostic tools [10]. The prevalence can range from 1% to 50% [3–6, 11, 12]. Although NTM are nowadays considered relevant pathogens in bronchiectasis [3], treatment of NTM pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) remains challenging even in specialised centres, since most of the recommendations suggested by international guidelines are conditional and based on scarce scientific evidence [13–15].

To date, very few studies on NTM infection and NTM-PD in bronchiectasis patients have been conducted in Europe, and the majority are single-centre, retrospective and without standardised definitions of clinical outcomes [3]. Recently, an NTM-NET consensus definition for key outcomes in NTM-PD has been proposed, including cure, treatment failure, recurrence, relapse, re-infection, death and treatment halted [16]. So far, no studies have evaluated incidence and prevalence of NTM infection and NTM-PD in bronchiectasis patients, as well as their clinical outcomes according to the NTM-NET consensus definitions.

The objectives of this study were to assess both prevalence and incidence of NTM infection and NTM-PD among bronchiectasis patients, describe their demographic, clinical, functional and radiological characteristics, as well as the therapeutic approach and clinical outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

An observational, prospective study was conducted at the Bronchiectasis Program of the Policlinico Hospital in Milan, Italy, from 2016 to 2018. Adults (aged ≥18 years) with a clinical and radiological (at least one lobe involvement on HRCT scan) diagnosis of bronchiectasis were consecutively recruited during their stable state (at least 1 month from the last exacerbation and/or antibiotic use). All patients should have had their respiratory samples (either sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or bronchial aspirate (BAS)) tested for NTM to be included in the present study. Patients with either cystic fibrosis or traction bronchiectasis due to pulmonary fibrosis were excluded. Patients were followed-up to 3 years after enrolment. The study was approved by the local ethical committee and all recruited subjects provided written informed consent.

Data collection and microbiological analysis

Demographics, medical history, comorbidities, immune, clinical, radiological and functional status, microbiological and laboratory data, and long-term treatment data were collected at enrolment. NTM-PD treatments and patients’ clinical outcomes were collected during a 3-year follow-up. The severity of bronchiectasis was evaluated according to both Bronchiectasis Severity Index (BSI) [17] and FACED (forced expiratory volume in 1 s, age, chronic colonisation, extension and dyspnoea) scores [18]. The Bronchiectasis Aetiology Comorbidity Index (BACI) was calculated for all patients [19]. Radiological severity of bronchiectasis was assessed using a modified Reiff score, which rates the number of involved lobes (with the lingula considered to be a separate lobe) and the degree of dilatation (range 1–18) [20]. Murray–Washington criteria were used for sputum quality assessment in all cases, with all samples having less than 10 squamous cells and more than 25 leukocytes per low-power microscope field. Bacteriology was performed during a stable state on spontaneous sputum samples, BAL or BAS samples in patients showing an HRCT appearance of a tree-in-bud pattern without productive cough.

Study definitions

NTM-PD was defined according to the 2007 American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines as the presence of both clinical (pulmonary symptoms, radiographic abnormalities and appropriate exclusion of other diagnoses) and microbiological (positive culture from at least two separate sputum samples or one bronchoscopic specimen) criteria [14]. The Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines were used to define drug susceptibility testing and reporting [21]. Chronic infection was defined by evidence of positive respiratory tract cultures of the same microorganism by standard microbiology on two or more occasions at least 3 months apart over 1 year while the patient was in a stable state [1, 22]. Bronchiectasis exacerbation was defined by a change in bronchiectasis treatment determined by a clinician due to a deterioration in three or more of the following key symptoms for at least 48 h: cough; sputum volume and/or consistency; sputum purulence; breathlessness and/or exercise tolerance; fatigue and/or malaise; and haemoptysis [23].

NTM treatment and study outcomes

The NTM-PD treatment regimen was chosen according to the isolated pathogen, radiological pattern, clinical characteristics and potential drug toxicities after a multidisciplinary discussion between at least one pulmonologist and an infectious disease physician, and according to the 2007 ATS/IDSA guidelines [14].

The primary outcome of the study was the incidence of NTM infection. Incidence was defined by the number of new cases that were diagnosed during the study period.

Secondary outcomes included incidence of NTM-PD, prevalence of NTM infection and NTM-PD, culture conversion, microbiological and clinical cure, treatment failure, recurrence, relapse, re-infection, death, and treatment halted as defined by the NTM-NET consensus statement (see supplementary material) [16].

Study groups

The study population was divided in different groups according to the presence of NTM and NTM-PD: patients positive versus negative for NTM (including those with NTM-PD); patients with versus without NTM-PD; and patients with NTM-PD versus those with NTM isolation versus those who tested negative for NTM.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and Stata version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Characteristics of the population including respiratory symptoms, radiological features, pulmonary function tests and microbiological isolation, as well as study outcomes were considered for statistical analysis. Qualitative and quantitative variables were summarised with frequencies (absolute and relative (percentage)) and central tendency (mean and median) and variability (standard deviation and interquartile range (IQR)) indicators according to their parametric distribution. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was conducted for every quantitative variable to assess its parametric distribution. t-tests or Mann–Whitney tests were used for quantitative variables with a parametric or nonparametric distribution, respectively. χ2 was computed for qualitative variables. Comparison of more than two groups was conducted using the Kruskal–Wallis test. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

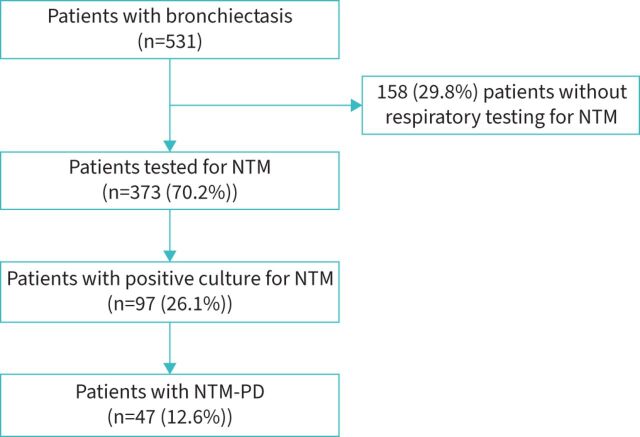

Among 531 bronchiectasis patients evaluated at first visit in the bronchiectasis programme during the study period, 373 (70.2%; median age 62 years; 77.5% female) underwent either sputum, BAL or BAS testing for NTM (figure 1 and table 1). The most common respiratory comorbidities were rhinosinusitis (35.9%), asthma (16.6%) and COPD (8%), whereas the most prevalent nonrespiratory comorbidities were gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (44.2%), systemic hypertension (22.3%), osteoporosis (15.3%) and neoplasia (12.9%). 228 (61.1%) patients had a history of an episode of pneumonia and 119 (31.9%) patients had a history of immunodeficiencies. 111 (30%) patients were frequent exacerbators (at least three exacerbations in the previous year) and 49 (13.2%) patients had at least one hospitalisation during the previous year.

FIGURE 1.

Characterisation of the bronchiectasis population according to microbiological isolations. NTM: nontuberculous mycobacteria; PD: pulmonary disease.

TABLE 1.

Demographics, medical history, immune status, disease severity, clinical, radiological and functional status, and microbiology, laboratory and treatment data of the study population (n=373)

| Demographics | |

| Age, years | 62 (50–71) |

| >65 years | 151 (40.5) |

| >75 years | 47 (12.6) |

| Female | 289 (77.5) |

| BMI, kg·m−2 | 21.4 (19.0–24.0) |

| Underweight (BMI <18.5 kg·m−2) | 63 (16.9) |

| Smoker or ex-smoker | 163 (43.7) |

| Medical history | |

| Pneumonia | 228 (61.1) |

| GORD | 165 (44.2) |

| Rhinosinusitis | 134 (35.9) |

| Childhood respiratory infection | 123 (33.0) |

| Systemic hypertension | 83 (22.3) |

| Asthma | 62 (16.6) |

| Osteoporosis | 57 (15.3) |

| Neoplastic disease | 48 (12.9) |

| Otitis | 39 (10.5) |

| Nasal polyps | 38 (10.2) |

| Depression | 36 (9.7) |

| COPD | 30 (8.0) |

| Primary ciliary dyskinesia | 28 (7.5) |

| Anxiety | 25 (6.7) |

| Tuberculosis | 19 (5.1) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 16 (4.3) |

| Diabetes | 15 (4.0) |

| History of connective tissue disease | 11 (3.0) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 10 (2.7) |

| Pertussis | 7 (1.9) |

| Chronic renal failure | 7 (1.9) |

| History of inflammatory bowel disease | 5 (1.3) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 5 (1.3) |

| Aspiration | 3 (0.8) |

| Active neoplastic disease | 3 (0.8) |

| Congenital airway abnormality | 2 (0.5) |

| Foreign body inhalation or obstruction | 1 (0.3) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1 (0.3) |

| Haemodialysis | 1 (0.3) |

| Immune status | |

| Any immunodeficiency | 71 (18.8) |

| Primary immunodeficiencies | 57 (15.3) |

| Secondary immunodeficiencies | 14 (3.8) |

| HIV | 1 (0.3) |

| IgG deficiency | 11 (3.0) |

| IgA deficiency | 9 (2.4) |

| IgG subclass deficiency | 44 (11.9) |

| IgM deficiency | 18 (4.9) |

| DiGeorge syndrome | 0 (0.0) |

| CVID | 4 (1.1) |

| History of immunodeficiency | 119 (31.9) |

| B-lymphocyte deficiency | 44 (11.8) |

| T-lymphocyte deficiency | 28 (7.5) |

| Natural killer cell deficiency | 13 (3.5) |

| Disease severity | |

| BSI score | 6 (4–9) |

| BSI risk class | |

| Mild | 115 (30.8) |

| Moderate | 136 (36.5) |

| Severe | 112 (30) |

| BACI score | 0 (0–3) |

| FACED score | 2 (1–3) |

| FACED risk class | |

| Mild | 231 (61.9) |

| Moderate | 112 (30) |

| Severe | 29 (7.8) |

| Radiological status | |

| Reiff score | 4 (3–6) |

| Involved lobes, n | 4 (2–5) |

| Cavitation | 17 (4.6) |

| Bronchiectasis in middle lobe | 306 (82.0) |

| Bronchiectasis in lingula | 260 (69.7) |

| Bronchiectasis in middle lobe and lingula | 243 (65.1) |

| Clinical status | |

| Sputum volume, mL | 10 (5–25) |

| Daily sputum | 278 (74.5) |

| Sputum colour | |

| Mucous | 51 (20.4) |

| Mucous–purulent | 114 (45.6) |

| Purulent | 85 (34.0) |

| mMRC grade | |

| 0 | 200 (53.6) |

| 1 | 116 (31.1) |

| 2 | 24 (6.4) |

| 3 | 17 (4.6) |

| 4 | 15 (4.0) |

| Exacerbations in previous year, n | 1 (1–3) |

| ≥3 exacerbations in previous year | 111 (30.0) |

| ≥1 hospitalisations in previous year | 49 (13.2) |

| Functional status | |

| FEV1, % pred | 82.5±24.0 |

| Microbiology | |

| Chronic infection with ≥1 pathogens | 131 (35.1) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 80 (21.4) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 21 (5.6) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 32 (8.6) |

| MRSA | 5 (1.3) |

| MSSA | 27 (7.2) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 3 (0.8) |

| Stenotrophomonas | 6 (1.6) |

| Achromobacter | 5 (1.3) |

| Other chronic infection | 10 (2.6) |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 2 (0.5) |

| Atypical mycobacteria | 97 (26) |

| Other bacteria | 70 (18.8) |

| Laboratory data | |

| C-reactive protein, mg·L−1 | 0.35 (0.12–0.94) |

| Long-term treatment | |

| Macrolide | 44 (11.8) |

| Inhaled antibiotics treatment | 31 (8.3) |

| Receiving ICS at NTM isolation | 123 (33.0) |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range), n (%) or mean±sd. BMI: body mass index; GORD: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease; CVID: common variable immunodeficiency; BSI: Bronchiectasis Severity Index; BACI: Bronchiectasis Aetiology Comorbidity Index; FACED: forced expiratory volume in 1 s, age, chronic colonisation, extension and dyspnoea; mMRC: modified Medical Research Council; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; MRSA: methicillin-resistant S. aureus; MSSA: methicillin-susceptible S. aureus; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; NTM: nontuberculous mycobacteria.

Epidemiology of NTM infection in bronchiectasis

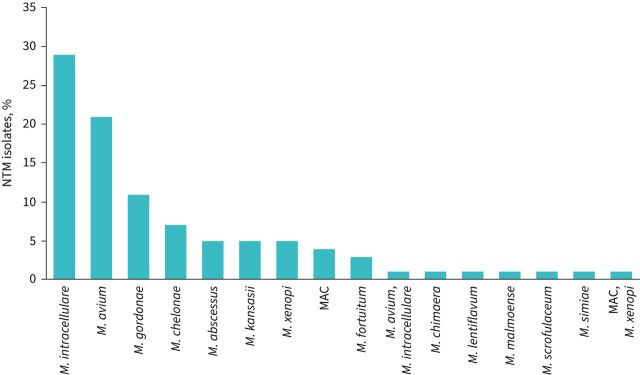

A total of 97 (26.1% among those who were tested for NTM and 18.3% among all bronchiectasis patients) patients had at least one respiratory sample positive for NTM (figure 2). Among bronchiectasis patients, the incidence rate for NTM infection was 13 (95% CI 10–16) per 100 person-years. 52.8% of patients had NTM isolated from sputum samples, 38.2% from BAL and 9% from BAS. The most prevalent NTM pathogens were M. intracellulare (29.9%), M. avium (21.6%) and M. gordonae (11.3%) (figure 2). A bacterial co-infection was detected in 30.9% (n=30) of NTM-positive patients, with P. aeruginosa being the most prevalent microorganism (n=20). Four out of 42 (9.5%) NTM-positive sputum samples showed resistance to amikacin and one out of 42 (2.4%) to macrolides. 41 (11%) patients had at least one environmental risk factor for NTM acquisition (e.g. gardening, fishing, visiting pools, spas, hot tubs, exposure to humidifiers and swimming). Four patients in our bronchiectasis cohort had allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and none of those had concomitant NTM infection/disease. Aspergillus fumigatus was isolated in the sputum of two patients with bronchiectasis and one of those had also NTM infection.

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) species isolated in the study population. MAC: M. avium complex.

Epidemiology of NTM-PD in bronchiectasis

A total of 47 (12.6% among NTM tested patients, 48.5% among NTM-positive patients and 8.8% among all bronchiectasis patients) patients received a diagnosis of NTM-PD. Among bronchiectasis patients, the incidence rate for NTM-PD was 4 (95% CI 2–6) per 100 person-years. The most frequent species were M. intracellulare (38.3%), M. avium (34%), M. abscessus (8.5%) and M. kansasii (8.5%). Two different NTM species were isolated in the same patient: M. avium complex and M. xenopi. One isolate showed resistance to macrolides (M. abscessus) and one to amikacin (M. kansasii). 19.1% of the NTM-PD patients had a fibro-cavitary pattern at chest CT.

Clinical characteristics of bronchiectasis patients with NTM infection or NTM-PD

NTM-positive patients were older, had a lower body mass index (BMI), had a higher frequency of B-lymphocyte and T-lymphocyte immunodeficiencies, were prescribed less inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), had more frequent exposure to inhaled antibiotics treatment, had more cavitations on chest CT scan, and had lower forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) values compared with the rest of the bronchiectasis population (table 2).

TABLE 2.

Demographics, medical history, clinical and radiological status, and pulmonary function, microbiology and laboratory data according to two study groups: patients with positive nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) testing (NTM+) and patients with bronchiectasis tested for NTM but without NTM isolation (NTM−)

| NTM+ (n=97) | NTM− (n=276) | p-value | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 65 (57–72) | 61 (47.5–71) | 0.015 |

| >65 years | 46 (47.4) | 105 (38) | 0.1 |

| >75 years | 14 (14.4) | 33 (11.9) | 0.5 |

| Male | 18 (18.6) | 66 (23.9) | 0.28 |

| BMI, kg·m−2 | 20.3 (18.5–22.04) | 22 (19.2–24.5) | <0.001 |

| Underweight (BMI <18.5 kg·m−2) | 24 (24.7) | 39 (14.1) | 0.017 |

| Smoker or ex-smoker | 47 (48.5) | 116 (42) | 0.27 |

| Medical history | |||

| Comorbid asthma | 10 (10.3) | 52 (18.8) | 0.05 |

| Comorbid COPD | 11 (11.3) | 19 (6.8) | 0.17 |

| Comorbid rhinosinusitis | 27 (27.8) | 107 (38.8) | 0.05 |

| B-lymphocyte deficiency | 20 (20.6) | 24 (8.7) | 0.002 |

| T-lymphocyte deficiency | 13 (13.4) | 15 (5.4) | 0.01 |

| Natural killer deficiency | 4 (4.1) | 9 (3.3) | 0.69 |

| IgA deficiency | 0 (0) | 9 (3.3) | 0.07 |

| IgM deficiency | 5 (5.2) | 13 (4.7) | 0.85 |

| IgG deficiency | 3 (3.1) | 8 (2.9) | 0.92 |

| IgG subclass deficiency | 11 (11.3) | 33 (12) | 0.89 |

| Long-acting β-agonist treatment | 44 (45.4) | 145 (52.5) | 0.22 |

| Long-acting muscarinic antagonist treatment | 46 (47.4) | 90 (32.6) | 0.009 |

| Receiving ICS at NTM isolation | 20 (20.6) | 103 (37.3) | 0.003 |

| Inhaled antibiotics treatment | 14 (14.4) | 17 (6) | 0.01 |

| Macrolide treatment | 11 (11.3) | 3 (11.9) | 0.87 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 37 (38.1) | 8 (30.7) | 0.19 |

| Clinical status | |||

| Sputum volume, mL | 10 (5–30) | 10 (5–25) | 0.85 |

| Daily sputum | 69 (71.1) | 209 (75.7) | 0.37 |

| mMRC grade | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.58 |

| BSI score | 7 (5–10) | 6 (4–9) | 0.014 |

| BSI risk class | |||

| Mild | 21 (21.6) | 94 (34.1) | 0.02 |

| Moderate | 39 (40.2) | 97 (35.1) | 0.35 |

| Severe | 34 (35.1) | 78 (28.3) | 0.19 |

| BACI score | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–3) | 0.27 |

| Exacerbations in previous year, n | 1 (0–3) | 1 (1–3) | 0.49 |

| ≥3 exacerbations in previous year | 28 (28.9) | 83 (30) | 0.84 |

| FACED score | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.3 |

| FACED risk class | |||

| Mild | 56 (57.7) | 175 (63.4) | 0.3 |

| Moderate | 33 (34) | 79 (28.6) | 0.33 |

| Severe | 8 (8.3) | 21 (7.6) | 0.85 |

| Radiological status | |||

| Reiff score | 4 (3–6) | 4 (2–6) | 0.54 |

| Involved lobes, n | 4 (3–5) | 4 (2–5) | 0.3 |

| Cavitation | 11 (11.3) | 6 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| Bronchiectasis in middle lobe | 84 (86.6) | 222 (80.4) | 0.09 |

| Bronchiectasis in lingula | 71 (74.7) | 189 (68.5) | 0.27 |

| Bronchiectasis in middle lobe and lingula | 67 (70.5) | 176 (63.8) | 0.27 |

| Functional status | |||

| FEV1, % pred | 74 (65.5–92) | 84 (68–101) | 0.02 |

| Microbiology | |||

| Chronic infection with ≥1 pathogens | 30 (30.9) | 101 (36.6) | 0.12 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 21 (21.6) | 59 (21.4) | 0.73 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| C-reactive protein, mg·L−1 | 0.45 (0.17–1.01) | 0.3 (0.12–0.9) | 0.049 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or n (%), unless otherwise stated. BMI: body mass index; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; mMRC: modified Medical Research Council; BSI: Bronchiectasis Severity Index; BACI: Bronchiectasis Aetiology Comorbidity Index; FACED: forced expiratory volume in 1 s, age, chronic colonisation, extension and dyspnoea; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s.

NTM-PD patients had a lower BMI, were less likely to have asthma and to receive ICS treatment, had a higher frequency of T-lymphocyte immunodeficiencies, had more cavitations on chest CT scan, and had fewer exacerbations compared with patients without NTM-PD (table 3).

TABLE 3.

Demographics, medical history, clinical and radiological status, and pulmonary function, microbiology and laboratory data according to two study groups: patients with nontuberculous mycobacteria pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) and patients with bronchiectasis tested for NTM but without NTM-PD

| NTM-PD+ (n=47) | NTM-PD− (n=326) | p-value | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 65 (60–70) | 62 (48–71) | 0.15 |

| >65 years | 21 (44.7) | 130 (39.9) | 0.53 |

| >75 years | 3 (6.4) | 44 (13.5) | 0.17 |

| Male | 8 (17) | 76 (23.3) | 0.34 |

| BMI, kg·m−2 | 20 (18–21.4) | 21.8 (19–24.4) | <0.001 |

| Underweight (BMI <18.5 kg·m−2) | 13 (27.7) | 50 (15.3) | 0.035 |

| Smoker or ex-smoker | 24 (51.1) | 139 (42.6) | 0.28 |

| Medical history | |||

| Comorbid asthma | 1 (2.1) | 61 (18.7) | 0.004 |

| Comorbid COPD | 2 (4.2) | 28 (8.6) | 0.3 |

| Comorbid rhinosinusitis | 9 (19.1) | 125 (38.3) | 0.01 |

| B-lymphocyte deficiency | 7 (14.9) | 37 (11.3) | 0.48 |

| T-lymphocyte deficiency | 7 (14.9) | 21 (6.4) | 0.04 |

| Natural killer deficiency | 2 (4.3) | 11 (3.4) | 0.76 |

| IgA deficiency | 0 (0) | 9 (2.8) | 0.25 |

| IgM deficiency | 3 (6.4) | 15 (4.6) | 0.56 |

| IgG deficiency | 1 (2.1) | 10 (3.1) | 0.74 |

| IgG subclass deficiency | 7 (14.9) | 37 (11.3) | 0.45 |

| Long-acting β-agonist treatment | 13 (27.7) | 176 (53.9) | <0.001 |

| Long-acting muscarinic antagonist treatment | 21 (44.7) | 115 (35.3) | 0.21 |

| Receiving ICS at NTM isolation | 2 (4.3) | 121 (37.1) | <0.001 |

| Inhaled antibiotics treatment | 6 (13.8) | 25 (7.7) | 0.24 |

| Macrolide treatment | 6 (12.8) | 38 (11.7) | 0.83 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 16 (34) | 106 (32.5) | 0.83 |

| Clinical status | |||

| Sputum volume, mL | 5.5 (5–30) | 10 (5–25) | 0.38 |

| Daily sputum | 30 (63.8) | 248 (76.1) | 0.07 |

| mMRC grade | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.78 |

| BSI score | 6.5 (4–10) | 6 (4–9) | 0.44 |

| BSI risk class | |||

| Mild | 13 (27.7) | 102 (31.3) | 0.75 |

| Moderate | 17 (36.2) | 119 (36.5) | 0.87 |

| Severe | 14 (29.8) | 98 (30.1) | 0.88 |

| BACI score | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–3) | 0.009 |

| Exacerbations in previous year, n | 1 (0–2) | 2 (1–3) | 0.002 |

| ≥3 exacerbations in previous year | 9 (19.1) | 102 (31.3) | 0.09 |

| ≥1 hospitalisations in previous year | 3 (6.4) | 46 (14.1) | 0.15 |

| FACED score | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.74 |

| FACED risk class | |||

| Mild | 30 (63.8) | 201 (61.7) | 0.79 |

| Moderate | 15 (31.9) | 97 (29.7) | 0.77 |

| Severe | 2 (4.3) | 27 (8.3) | 0.33 |

| Radiological status | |||

| Reiff score | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) | 0.69 |

| Involved lobes, n | 4 (2.5–6) | 4 (2–5) | 0.22 |

| Cavitation | 9 (19.1) | 8 (2.5) | <0.001 |

| Bronchiectasis in middle lobe | 40 (85.1) | 266 (81.6) | 0.26 |

| Bronchiectasis in lingula | 36 (76.6) | 224 (68.7) | 0.13 |

| Bronchiectasis in middle lobe and lingula | 34 (72.3) | 209 (64.1) | 0.14 |

| Functional status | |||

| FEV1, % pred | 74 (65.5–90.5) | 84 (67–101) | 0.07 |

| Microbiology | |||

| Chronic infection with ≥1 pathogens | 15 (31.9) | 116 (35.6) | 0.37 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 11 (23.4) | 69 (21.2) | 0.96 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| C-reactive protein, mg·L−1 | 0.59 (0.23–0.97) | 0.33 (0.12–0.93) | 0.14 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or n (%), unless otherwise stated. BMI: body mass index; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; mMRC: modified Medical Research Council; BSI: Bronchiectasis Severity Index; BACI: Bronchiectasis Aetiology Comorbidity Index; FACED: forced expiratory volume in 1 s, age, chronic colonisation, extension and dyspnoea; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s.

The comparison of clinical characteristics among patients with NTM-PD versus those infected by NTM but without pulmonary disease versus those without NTM isolation is reported in table 4.

TABLE 4.

Demographics, medical history, clinical and radiological status, and pulmonary function, microbiology and laboratory data according to three study groups: patients with nontuberculous mycobacteria pulmonary disease (NTM-PD), patients infected by NTM but without pulmonary disease development (NTM infection) and patients with bronchiectasis tested for NTM but without NTM isolation

| NTM-PD (n=47) | NTM infection (n=50) |

Bronchiectasis without

NTM isolation (n=276) |

p-value | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years | 65 (60–70) | 66.5 (54–75) | 61 (47.5–71) | 0.05 |

| >65 years | 21 (44.7) | 25 (50) | 105 (38) | 0.23 |

| >75 years | 3 (6.4) | 11 (22) | 33 (11.9) | 0.056 |

| Male | 8 (17) | 10 (20) | 66 (23.9) | 0.5 |

| BMI, kg·m−2 | 20 (18–21.4)¶ | 21 (18.9–24) | 22 (19.2–24.5)¶ | <0.001 |

| Underweight (BMI <18.5 kg·m−2) | 13 (27.7)¶ | 11 (22) | 39 (14.1)¶ | 0.04 |

| Smoker or ex-smoker | 2 (51.1) | 23 (46) | 116 (42) | 0.48 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Comorbid asthma | 1 (2.1)#,¶ | 9 (18)# | 52 (18.8)¶ | 0.017 |

| Comorbid COPD | 2 (4.2)# | 9 (18)#,+ | 19 (6.8)+ | 0.018 |

| Comorbid rhinosinusitis | 9 (19.1)¶ | 18 (36) | 107 (38.8)¶ | 0.035 |

| B-lymphocyte deficiency | 7 (14.9) | 13 (26)+ | 24 (8.7)+ | 0.002 |

| T-lymphocyte deficiency | 7 (14.9)¶ | 6 (12) | 15 (5.4)¶ | 0.033 |

| Natural killer deficiency | 2 (4.3) | 2 (4) | 9 (3.3) | 0.92 |

| IgA deficiency | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (3.3) | 0.2 |

| IgM deficiency | 3 (6.4) | 2 (4) | 13 (4.7) | 0.83 |

| IgG deficiency | 1 (2.1) | 2 (4) | 8 (2.9) | 0.87 |

| IgG subclass deficiency | 7 (14.9) | 4 (4) | 33 (12) | 0.55 |

| Long-acting β-agonist treatment | 13 (27.7)#,¶ | 31 (62)# | 145 (52.5)¶ | 0.002 |

| Long-acting muscarinic antagonist treatment | 21 (44.7) | 25 (50)+ | 90 (32.6)+ | 0.029 |

| Receiving ICS at NTM isolation | 2 (4.3)#,¶ | 18 (36)# | 103 (37.3)¶ | <0.001 |

| Inhaled antibiotics treatment | 6 (13.8) | 8 (16)+ | 17 (6)+ | 0.034 |

| Macrolide treatment | 6 (12.8) | 5 (10) | 33 (11.9) | 0.9 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 16 (34) | 21 (42) | 85 (30.7) | 0.29 |

| Clinical status | ||||

| Sputum volume, mL | 5.5 (5–30) | 10 (5–27.5) | 10 (5–25) | 0.62 |

| Daily sputum | 30 (63.8) | 39 (78) | 209 (75.7) | 0.19 |

| mMRC grade | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.85 |

| BSI score | 6.5 (4–10) | 7 (5–11)+ | 6 (4–9)+ | 0.03 |

| BSI score risk class | ||||

| Mild | 13 (27.7) | 8 (16)+ | 94 (34.1)+ | 0.029 |

| Moderate | 17 (36.2) | 22 (44) | 97 (35.1) | 0.56 |

| Severe | 14 (29.8) | 20 (40) | 78 (28.3) | 0.3 |

| BACI score | 0 (0–0)#,¶ | 0 (0–3)# | 0 (0–3)¶ | 0.03 |

| Exacerbations in previous year, n | 1 (0–2)#,¶ | 2 (1–4)# | 1 (1–3)¶ | 0.003 |

| ≥3 exacerbation in previous year | 9 (19.1) | 19 (38) | 83 (30.1) | 0.14 |

| FACED score | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.25 |

| FACED risk class | ||||

| Mild | 30 (63.8) | 26 (52) | 175 (63.4) | 0.29 |

| Moderate | 15 (31.9) | 18 (36) | 79 (28.6) | 0.56 |

| Severe | 2 (4.3) | 6 (12) | 21 (7.6) | 0.36 |

| Radiological status | ||||

| Reiff score | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (2–6) | 0.83 |

| Involved lobes, n | 4 (2.5–6) | 4 (3–4) | 4 (2–5) | 0.43 |

| Cavitation | 9 (19.1)#,¶ | 2 (4)# | 6 (2.2)¶ | <0.001 |

| Bronchiectasis in middle lobe | 40 (85.1) | 44 (88) | 222 (80.4) | 0.25 |

| Bronchiectasis in lingula | 36 (76.6) | 35 (70) | 18 (68.5) | 0.31 |

| Bronchiectasis in middle lobe and lingula | 34 (72.3) | 33 (66) | 176 (63.8) | 0.33 |

| Functional status | ||||

| FEV1, % pred | 74 (65.5–90.5)¶ | 77.5 (65.5–95) | 84 (68–101)¶ | 0.049 |

| Microbiology | ||||

| Chronic infection with ≥1 pathogens | 15 (31.9) | 15 (31.9) | 101 (36.6) | 0.29 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 11 (23.4) | 10 (21.3) | 59 (21.4) | 0.89 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| C-reactive protein, mg·L−1 | 0.59 (0.23–0.97) | 0.4 (0.16–1.05) | 0.3 (0.12–0.9) | 0.14 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or n (%), unless otherwise stated. BMI: body mass index; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; mMRC: modified Medical Research Council; BSI: Bronchiectasis Severity Index; BACI: Bronchiectasis Aetiology Comorbidity Index; FACED: forced expiratory volume in 1 s, age, chronic colonisation, extension and dyspnoea; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s. #: p<0.05 (NTM-PD versus NTM infection); ¶: p<0.05 (NTM-PD versus bronchiectasis without NTM isolation); +: p<0.05 (NTM infection versus bronchiectasis without NTM isolation).

Treatment and clinical outcomes during follow-up

46 out of 47 (97.9%) NTM-PD patients were prescribed antibiotics, including ethambutol in 41 (89.1%) cases, rifampicin in 33 (71.7%) cases, azithromycin in 32 (69.6%) cases, clarithromycin in 13 (28.3%) cases, rifabutin in 12 (26.1%) cases and intravenous amikacin in 11 (23.9%) cases. One patient refused pharmacological treatment. The median (IQR) treatment duration was 540 (370–770) days. The median (IQR) duration of follow-up from the first NTM isolation to the last visit was 1020 (600–2190) days. 20 (43.5%) patients who underwent NTM treatment experienced adverse events, including visual toxicity (n=8), gastrointestinal intolerance (n=5), allergy (n=5), liver toxicity (n=2) and cardiotoxicity (n=1).

Culture conversion was achieved in 27 (58.7%) patients. A positive outcome was documented in 24 (52.2%) patients, including clinical cure in 24 (52.2%) patients, microbiological cure in 19 (41.3%) patients and cure in 19 (41.3%) patients. A negative outcome was recorded in 15 (32.6%) patients, including recurrence in eight (17.4%) patients, treatment failure in five (10.9%) patients, re-infection in one (2.2%) patient and relapse in one (2.2%) patient. An unknown outcome was observed in four (8.7%) patients. Eight patients were still on active treatment at the end of the follow-up period. Treatment halted was experienced in 11 (23.9%) patients (seven (63.6%) cases because of treatment-related adverse events). No patients died. No differences were detected between patients with MAC-PD versus those with other NTM-PD in terms of unsuccessful outcomes (51.4% versus 44.4%; p=0.76). None of the studied clinical characteristics were statistically significantly associated with treatment success/failure.

Discussion

The present study shows that among adults with bronchiectasis tested for NTM: 1) the incidence rates of NTM infection and NTM-PD were 13 and 4 per 100 person-years, respectively, while the prevalence of NTM isolation and NTM-PD was 26.1% and 12.6%, respectively; 2) NTM-positive patients had a lower BMI, a more severe impairment of pulmonary function and cellular immunity, a higher frequency of cavitary lesions on chest CT, and a lower exacerbations rate compared with NTM-negative patients; 3) once treatment for NTM-PD was initiated, a negative outcome was recorded in almost one-third of the patients, including recurrence in 17.4%, treatment failure in 10.9%, re-infection in 2.2% and relapse in 2.2%; and 4) treatment halted was experienced in >20% of the patients, especially because of adverse events related to the prescribed regimens.

The prevalence of NTM isolation and NTM-PD found in our study is higher compared with the 12.2% and 8.8%, respectively, reported in a previous Italian study conducted from 2012 to 2015 [3]. A significant increase in NTM prevalence among bronchiectasis patients over the past few years has also been demonstrated by Lee et al. [7], who showed how NTM prevalence in patients with bronchiectasis doubled from 2012 to 2016. Furthermore, Máiz et al. [10] found a lower prevalence of both NTM isolation and NTM-PD disease (8.3% and 2.3%, respectively) in 218 adult bronchiectasis patients in Spain during follow-up from 2002 to 2010. This difference from our estimates could be explained by the inclusion of patients who produce sputum, thereby underestimating the burden. Indeed, only 64% of NTM-PD patients and 71% of NTM-positive patients had daily sputum production in our cohort, in agreement with previously published literature [24, 25]. Nevertheless, data on patients with NTM infection and bronchiectasis are limited, and most studies have small sample sizes [3, 6]. The role of bronchoscopy in bronchiectasis patients who do not expectorate and are at risk for NTM infection should be further elucidated in experimental and observational studies.

Our study shows that NTM were isolated in 26.1% of NTM tested patients, whereas a diagnosis of NTM-PD was made in 48.5% of NTM-positive patients, which is a higher frequency if compared with the prevalence of 28% found in the Spanish study by Máiz et al. [10].

MAC was the most frequent (57.7%) mycobacteria in our cohort, confirming previous data published by both Faverio et al. [3] and Máiz et al. [10] who detected MAC in 75% and 50% of all NTM isolates, respectively. A bacterial co-infection was found in a third (31.3%) of our NTM-positive patients, including P. aeruginosa in almost 22% of them, in line with previous studies showing a prevalence ranging from 31% to 52% [3, 8].

Patients with NTM-PD were more likely to have cavities on HRCT compared with bronchiectasis patients without NTM-PD; however, the localisation of bronchiectasis in the lung lobes was not statistically different. Low BMI and underweight are commonly described in patients with NTM-PD [24, 26]. Accordingly, we found a lower BMI and higher prevalence of underweight in the NTM-PD group compared with bronchiectasis patients without NTM-PD or NTM infection. Patients with NTM-PD and NTM infection were more likely to have B- and T-lymphocyte immunodeficiencies than bronchiectasis patients without NTM isolation, while no difference in humoral immune function was found between these groups. Finally, although ICS treatment is recognised as a clear risk factor for NTM infection, we had a lower prevalence than expected of NTM patients treated with ICS in our bronchiectasis cohort [27, 28]. This finding could be explained by both a low rate of asthma as a coexisting disease in this population and the fact that a practice of ICS withdrawal in bronchiectasis patients with neither asthma nor ABPA has been part of our standard operating procedures for several years.

97.9% of our NTM-PD patients underwent treatment; only one patient refused treatment. This prevalence is higher than that reported in the literature; one of the reasons is that all our enrolled patients belonged to a specific bronchiectasis programme [24]. These patients are seen by the same physician and a strong relationship has been built between them over several years. Thus, at the time of NTM-PD diagnosis, a long discussion between the patients and the physician had occurred, and the final outcome was a shared decision to start treatment for the majority of the patients. Only 52.2% of NTM-PD patients who underwent guideline-based treatment achieved clinical cure. This percentage is lower than that reported by Diel et al. [29] in a recent meta-analysis which showed treatment success in 61–66% of MAC-PD patients and that previously published in another Italian experience [25] showing treatment success in 64.7% of the cases. These differences might be explained by our strict implementation of the NTM-NET definitions. Furthermore, in the study published by Faverio et al. [3] cultures were not available in up to 43% of NTM-PD patients once treatment was started; consequently, the rate of unsuccessful outcomes could have been underestimated. The rate of adverse events (43.5%) in our experience was similar to a previous study on NTM-PD in patients with bronchiectasis in Italy (47.4%) [3].

Compared with another study conducted in Italy for 10 years and which used the same NTM-NET definition [25], our adverse events rate seems to be slightly higher (43.5% versus 37.6%). Unsuccessful outcomes total rate was equal (32.6% versus 35.3%); simultaneously, there were some differences across outcome categories: treatment halted was registered in 23.9% of patients in our cohort and in 13.5% of patients in the 10-year Italian study, recurrence in 17.4% versus 11.2%, treatment failure in 10.9% versus 4.1%, re-infection in 2.2% versus 5.3% and relapse in 2.2% versus 1.2%. The differences in results obtained may be connected with the differences in study design: the previous study was retrospective and enrolled a different population of patients [25].

In our study population 23.9% of patients experienced treatment halted, with 63.6% due to side-effects. This points to the need to reconsider treatment regimens and therapeutic opportunities for patients with bronchiectasis and NTM-PD.

Some study limitations should be acknowledged. First, the single-centre design has an impact on the generalisability. For instance, NTM species identified in our study may be linked to the local ecology, which may not reflect significant geographical diversity. Second, some NTM-positive patients also had other bacterial isolates, such as P. aeruginosa, which may affect clinical and laboratory data. Finally, a large percentage of NTM-PD patients were on long-term antibiotic therapy (e.g. macrolides), which may have influenced the exacerbation rate.

The major strengths of this study include the prospective design, inclusion of a homogeneous cohort of patients with high-quality data, detailed clinical and microbiological history, and management in a bronchiectasis and NTM referral centre. Furthermore, this is the first study in Italy reporting both prevalence and incidence of NTM infection and NTM-PD among adults with bronchiectasis, as well as treatment outcomes according to the NTM-NET consensus [16]. Further multicentre studies with a prospective design and a larger sample size are needed to evaluate the risk of NTM-PD and its risk factors, and to assess if patients with bronchiectasis and NTM-PD require other specific therapeutic regimens or duration of treatment since unsuccessful treatment outcomes are very common.

In conclusion, NTM infection is frequent in bronchiectasis patients and the presence of NTM-PD is relevant. The low success rate for bronchiectasis patients who are treated because of an NTM-PD requires a call to action to identify new treatment modalities and new drugs to improve outcomes.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00060-2022.SUPPLEMENT (256.7KB, pdf)

Footnotes

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Author contributions: Conception and design: K. Suska and S. Aliberti. Formal analysis: K. Suska, S. Aliberti and G. Sotgiu. Investigation: S. Aliberti, F. Amati, A. Gramegna, M. Mantero and M. Ori. Data curation: S. Aliberti and G. Sotgiu. Original draft preparation: K. Suska, F. Amati and S. Aliberti. Review and editing of the manuscript: all authors. Supervision: S. Aliberti and F. Blasi.

Conflict of interest: K. Suska reports a grant from the European Respiratory Society for a Clinical Training Fellowship. F. Amati has nothing to disclose. G. Sotgiu reports personal payments from Insmed, Qiagen and EMA, and is an Associate Editor of this journal. A. Gramegna reports personal payment from Insmed, Grifols and Zambon. M. Mantero reports personal payment from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline. M. Ori has nothing to disclose. M. Ferrarese reports personal payment from Insmed. L.R. Codecasa has nothing to disclose. A. Stainer has nothing to disclose. F. Blasi reports research grants from AstraZeneca, Chiesi and Insmed; and personal payments from Menarini, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Guidotti, Insmed, Novartis, Viatris and Vertex. S. Aliberti reports research grants from Chiesi, Insmed and Fisher & Paykel; and personal payments from McGraw Hill, Insmed, Zambon, CSL Behring GmbH, AstraZeneca, Grifols, Fondazione Charta, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, ZCUBE Srl and Menarini.

References

- 1.Aliberti S, Goeminne PC, O'Donnell AE, et al. Criteria and definitions for the radiological and clinical diagnosis of bronchiectasis in adults for use in clinical trials: international consensus recommendations. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10: 298–306. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00277-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalmers JD, Aliberti S, Blasi F. Management of bronchiectasis in adults. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 1446–1462. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00119114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faverio P, Stainer A, Bonaiti G, et al. Characterizing non-tuberculous mycobacteria infection in bronchiectasis. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17: 1913. doi: 10.3390/ijms17111913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amati F, Simonetta E, Gramegna A, et al. The biology of pulmonary exacerbations in bronchiectasis. Eur Respir Rev 2019; 28: 190055. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0055-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonaiti G, Pesci A, Marruchella A, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015: 197950. doi: 10.1155/2015/197950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu H, Zhao L, Xiao H, et al. Prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients with bronchiectasis: a meta-analysis. Arch Med Sci 2014; 10: 661–668. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2014.44857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SJ, Ju S, You JW, et al. Trends in the prevalence of non-TB mycobacterial infection in patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis in South Korea, 2012–2016. Chest 2021; 159: 959–962. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zoumot Z, Boutou AK, Gill SS, et al. Mycobacterium avium complex infection in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Respirology 2014; 19: 714–722. doi: 10.1111/resp.12287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowman S, van Ingen J, Griffith DE, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2019; 54: 1900250. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00250-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Máiz L, Girón R, Olveira C, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with nontuberculous mycobacteria in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a multicenter observational study. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16: 437. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1774-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prevots DR, Marras TK. Epidemiology of human pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria: a review. Clin Chest Med 2015; 36: 13–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ku JH, Henkle EM, Carlson KF, et al. Validity of diagnosis code-based claims to identify pulmonary NTM disease in bronchiectasis patients. Emerg Infect Dis 2021; 27: 982–985. doi: 10.3201/eid2703.203124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daley CL, Iaccarino JM, Lange C, et al. Treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: an official ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA clinical practice guideline. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2000535. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00535-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175: 367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haworth CS, Banks J, Capstick T, et al. British Thoracic Society guidelines for the management of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD). Thorax 2017; 72: Suppl. 2, ii1–ii64. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Ingen J, Aksamit T, Andrejak C, et al. Treatment outcome definitions in nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: an NTM-NET consensus statement. Eur Respir J 2018; 51: 1800170. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00170-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chalmers JD, Goeminne P, Aliberti S, et al. The Bronchiectasis Severity Index. An international derivation and validation study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: 576–585. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1575OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martínez-García MÁ, de Gracia J, Vendrell Relat M, et al. Multidimensional approach to non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: the FACED score. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 1357–1367. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00026313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonnell MJ, Aliberti S, Goeminne PC, et al. Comorbidities and the risk of mortality in patients with bronchiectasis: an international multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4: 969–979. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30320-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reiff DB, Wells AU, Carr DH, et al. CT findings in bronchiectasis: limited value in distinguishing between idiopathic and specific types. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995; 165: 261–267. doi: 10.2214/ajr.165.2.7618537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Laboratory Detection and Identification of Mycobacteria: Approved Guideline. CLSI Document M48-A. Wayne, CLSI, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasteur MC, Helliwell SM, Houghton SJ, et al. An investigation into causative factors in patients with bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162: 1277–1284. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9906120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill AT, Haworth CS, Aliberti S, et al. Pulmonary exacerbation in adults with bronchiectasis: a consensus definition for clinical research. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1700051. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00051-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moon SM, Jhun BW, Baek SY, et al. Long-term natural history of non-cavitary nodular bronchiectatic nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2019; 151: 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aliberti S, Sotgiu G, Castellotti P, et al. Real-life evaluation of clinical outcomes in patients undergoing treatment for non-tuberculous mycobacteria lung disease: a ten-year cohort study. Respir Med 2020; 164: 105899. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.105899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song JH, Kim BS, Kwak N, et al. Impact of body mass index on development of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2021; 57: 2000454. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00454-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu VX, Winthrop KL, Lu Y, et al. Association between inhaled corticosteroid use and pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; 15: 1169–1176. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201804-245OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brode SK, Campitelli MA, Kwong JC, et al. The risk of mycobacterial infections associated with inhaled corticosteroid use. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1700037. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00037-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diel R, Nienhaus A, Ringshausen FC, et al. Microbiologic outcome of interventions against Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Chest 2018; 153: 888–921. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00060-2022.SUPPLEMENT (256.7KB, pdf)