Abstract

Background:

Health-related quality of life is decreased in burn survivors, with scars implicated as a cause. The authors aim to characterize the use of reconstructive surgery following hospitalization and determine whether patient-reported outcomes change over time. The authors hypothesized improvement in health-related quality of life following reconstructive surgery.

Methods:

Adult burn survivors undergoing reconstructive surgery within 24 months after injury were extracted from a prospective, longitudinal database from 5 U.S. burn centers (Burn Model System). Surgery was classified by problem as follows: scar, contracture, and open wound. The authors evaluated predictors of surgery using logistic regression. Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 health survey outcomes at 6, 12, and 24 months were compared at follow-up intervals and matched with nonoperated participants using propensity score matching.

Results:

Three hundred seventy-two of 1359 participants (27.4 percent) underwent one or more reconstructive operation within 24 months of injury. Factors that increased the likelihood of surgery included number of operations during index hospitalization (p < 0.001), hand (p = 0.001) and perineal involvement (p = 0.042), and range-of-motion limitation at discharge (p < 0.001). Compared to the physical component scores of peers who were not operated on, physical component scores increased for participants undergoing scar operations; however, these gains were only significant for those undergoing surgery more than 6 months after injury (p < 0.05). Matched physical component scores showed nonsignificant differences following contracture operations. Mental component scores were unchanged or lower following scar and contracture surgery.

Conclusions:

Participants requiring more operations during index admission were more likely to undergo reconstructive surgery. There were improvements in Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores for those undergoing scar operations more than 6 months after injury, although contracture operations were not associated with significant differences in Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores.

Burn survivors experience physical and psychological injuries that evolve over the course of their acute treatment and rehabilitation. Patients report decreased health-related quality of life for up to 24 months after burn injury.1 Despite best efforts at early excision and reconstruction, burn survivors experience significant scarring that can limit health-related quality of life, impacting both physical and psychological health.2,3 Furthermore, many burn survivors are discharged with persistent wounds or develop new wounds that require ongoing care and surgery that may affect health-related quality of life.

Reconstructive surgery attempts to ameliorate scarring and wounds through operations that reduce tension, improve cosmesis, and enhance function.4 However, little is known about which population of burn survivors undergoes surgery following discharge. In addition, no publication to date has reported whether reconstructive surgery during the first 24 months of burn recovery actually improves health-related quality of life. This study aims to (1) identify the population most likely to undergo reconstructive operations and (2) evaluate differences in patient-reported outcomes before and after surgery. We hypothesize (1) that patients with more severe burn injuries undergo more operations after discharge, and (2) that health-related quality of life improves following reconstructive operations.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data Set

The Burn Model System national database is a prospectively collected longitudinal data set that includes data from five burn centers within the United States.5 Patients are enrolled in the database if they are able to provide written consent and satisfy one of the following enrollment criteria:

Aged 18 to 64 years with a burn injury greater than or equal to 20 percent total body surface area with surgical intervention.

Aged 65 years or older with a burn injury greater than or equal to 10 percent total body surface area with surgical intervention.

Aged 18 years or older with a burn injury to their face/neck, hands, or feet with surgical intervention.

Aged 18 years or older with a high-voltage electrical burn injury with surgical intervention.

Study participants are surveyed at hospital discharge and 6 ± 2, 12 ± 3, and 24 ± 6 months after their injury date.6 Data from adult Burn Model System participants who were burned between 2003 and 2016 were included, and data were pulled at the end of 2018 to include follow-up of people burned in 2016. Only participants who responded to the postdischarge burn surgery questionnaire were extracted for this data set.

Variables

Demographics included age, sex, race/ethnicity, and payer. Burn characteristics included burn size (percentage total body surface area), cause, location involved, number of inpatient burn operations, and any range-of-motion deformity at discharge. Participants were queried at their postinjury follow-up visits regarding recent burn-related operations. Surgical procedures were categorized under the following predetermined headings: scar (noncontracture), contracture, and wound. The database does not include information regarding the anatomical location of these operations and does not include nonsurgical scar treatments such as laser or steroid injection. The Burn Model System has used the Short Form12 since 2003 and the Veterans RAND 12 since 2015. Veterans RAND 12 scores were converted to Short Form-12 scores for comparative purposes.7,8 These two 12-item questionnaires are validated, generalizable, patient-reported outcome measures that assess physical and mental health.8 The physical health component summary contains the following information: general health, physical functioning, physical role, and bodily pain. The mental health component summary contains the following information: emotional role, vitality, mental health, and social functioning. For reference, the Short Form-12 and Veterans RAND 12 general population mean is 50 with a standard deviation of 10.9

Analysis

The first aim of our study was to evaluate predictors for burn-related surgery following discharge. Explanatory variables (i.e., independent variables) included all demographic and burn characteristics. Logistic regression was chosen for the binary outcome. Model fitness was assessed with a C statistic.

The second aim of our study was evaluation of the relationship between postinjury Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores and reconstructive operations. The Burn Model System data set characterizes the timing of surgery based on follow-up visit windows after injury. Thus, Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores can be measured before and after surgery. Evaluating changes in Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores only within the surgical cohort is problematic because it lacks controls. If an individual has improvements in Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores following surgery, this could have occurred regardless of surgery.10 Therefore, we matched participants who underwent surgery with Burn Model System participants who reported no surgery in the follow-up window. We matched with variables that were significant predictors for undergoing surgery (i.e., parsimonious variable selection). We also accounted for the timing windows such that comparisons were made only at specific follow-up time points. Appreciating that participants may undergo multiple different procedures in the study period (e.g., wound surgery at 6 months and scar surgery at 18 months), we compared Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores for participants undergoing only single operations at these time intervals. Propensity score matching was used to model average treatment effects of surgery on Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores. We used the following propensity score matching parameters: 1:1 matching using greedy nearest-neighbor selection without replacement. The following variables were selected given significance in the multivariable logistic regression: percentage total body surface area burned, number of procedures during index admission, presence of hand burn, presence of perineal burn, payer status, and range-of-motion deficiency at discharge. The maximum caliper distance was set at 0.2. Standardized mean differences were compared after matching. Analysis was completed with Stata/IC version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas). Significance for all models was determined at an alpha level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Cohorts and Frequency of Reconstructive Operations

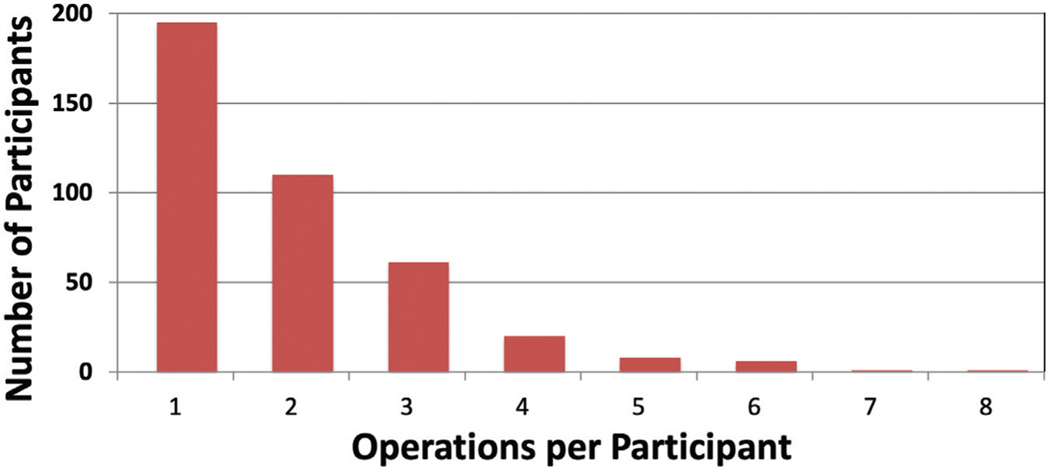

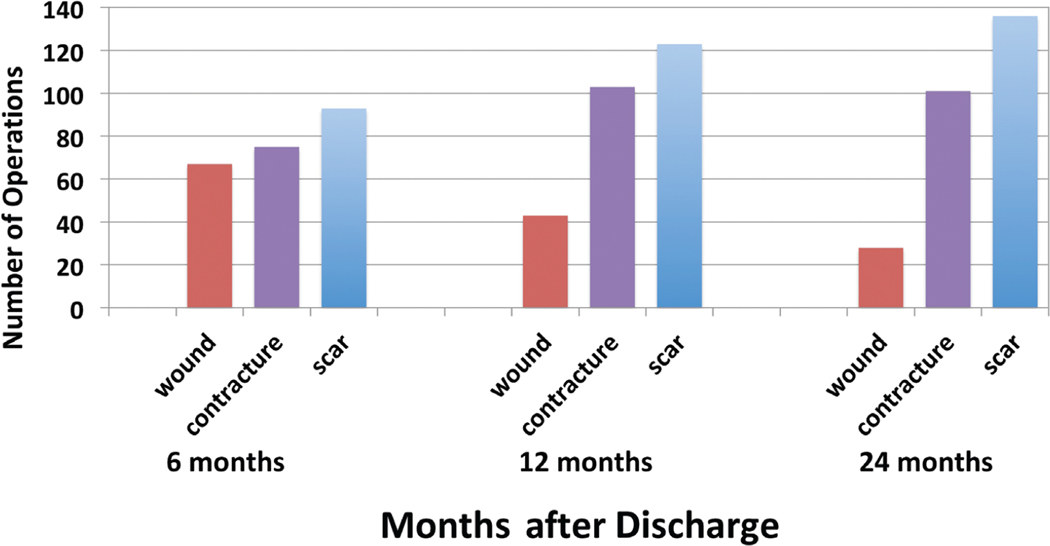

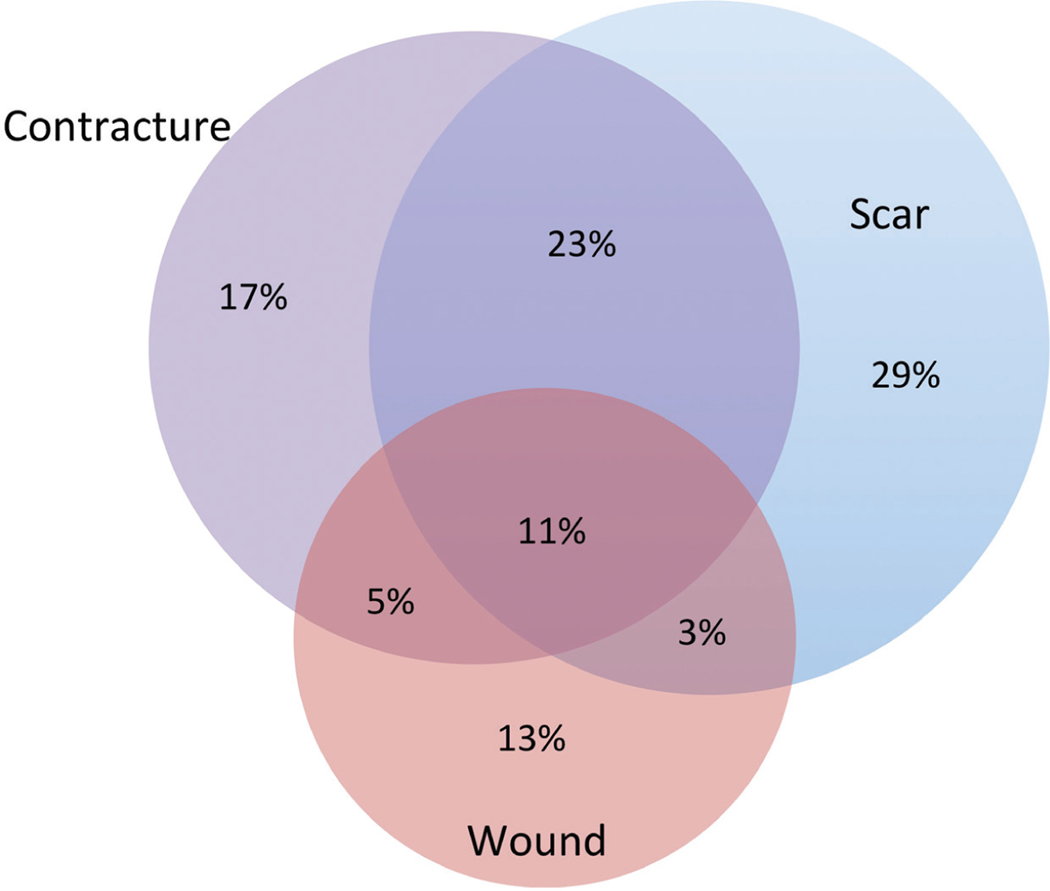

Of 3939 adult Burn Model System participants, 1359 responded to the question about whether they had undergone a burn-related surgical procedure since discharge. Of these, 372 (27.4 percent) responded that they underwent at least one burn-related operation within 24 months of injury (Fig. 1). Of the participants who underwent surgery, the mean number of operations was 1.91 ± 1.20, with a median of 2 (interquartile range, 1 to 2.5). Scar-related operations were most frequent, followed by contracture and wound-related surgery (Fig. 2). The total numbers of scar-and contracture-related operations increased during each period, whereas wound-related operations decreased over time. The majority of participants (59 percent) underwent only one type of operation (Fig. 3). When participants underwent more than one type of operation, most (23 percent) underwent a combination of scar and contracture procedures.

Fig. 1.

Number of operations per participant.

Fig. 2.

Number of operations for entire cohort by type and follow-up period.

Fig. 3.

Venn diagram of procedural types for study participants.

Multivariable Model Evaluating Predictors of Reconstructive Operations

The study population was parsed into two cohorts based on whether they underwent a burn-related operation after discharge (Table 1). Using white as the reference group, race distribution was similar between the groups, with the exception of “other” race, which showed significantly lower odds of undergoing surgery after discharge (OR, 0.41; 95 percent CI, 0.18 to 0.92; p = 0.031). Payer at the time of discharge demonstrated that participants with Medicaid insurance (OR, 0.60; 95 percent CI, 0.37 to 0.98; p = 0.043) and other insurance (i.e., unlisted/Veterans Affairs/self-pay) (OR, 0.42; 95 percent CI, 0.26 to 0.68; p < 0.001) were significantly less likely to undergo reconstructive surgery.

Table 1.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Evaluating Predictors of Burn-Related Operation after Hospitalization

| Surgery (%) | No Surgery (%) | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 372 | 987 | |||

| Male | 274 (73.7) | 677 (68.6) | 1.09 | 0.78–1.52 | 0.612 |

| Mean age ± SD, yr | 41.3 ± 15.9 | 44.1 ± 16.3 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.567 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 235 (63.2) | 613 (62.1) | Ref | ||

| Black | 45 (12.1) | 161 (16.3) | 0.85 | 0.54–1.33 | 0.475 |

| Hispanic nonwhite | 75 (20.2) | 142 (14.4) | 0.87 | 0.58–1.31 | 0.511 |

| Asian | 4 (1.1) | 14 (1.4) | 0.46 | 0.10–2.05 | 0.311 |

| Other | 12 (3.2) | 50 (5.1) | 0.41 | 0.18–0.92 | 0.031 |

| Unknown | 1 (0.3) | 7 (0.7) | 0.63 | 0.06–6.60 | 0.699 |

| Payer | |||||

| Private | 76 (20.4) | 192 (19.5) | Ref | ||

| Medicare | 44 (11.8) | 154 (15.6) | 0.82 | 0.48–1.40 | 0.461 |

| Medicaid | 57 (15.3) | 138 (14.0) | 0.59 | 0.36–0.98 | 0.042 |

| Workers’ compensation | 86 (23.1) | 133 (13.5) | 1.39 | 0.85–2.26 | 0.191 |

| Managed care | 38 (10.2) | 99 (10.0) | 1.12 | 0.65–1.92 | 0.682 |

| Philanthropy | 23 (6.2) | 10 (1.0) | 0.70 | 0.38–1.32 | 0.273 |

| Other* | 71 (19.1) | 271 (27.5) | 0.42 | 0.25–0.72 | 0.001 |

| Burn size (%TBSA) | |||||

| ≤10 | 99 (26.6) | 461 (46.7) | Ref | ||

| 11–20 | 54 (14.5) | 197 (20.0) | 1.04 | 0.66–1.64 | 0.855 |

| 21–30 | 72 (19.4) | 160 (16.2) | 1.11 | 0.71–1.74 | 0.654 |

| 31–40 | 49 (13.2) | 72 (7.3) | 1.33 | 0.76–2.32 | 0.321 |

| 41–50 | 23 (6.2) | 54 (5.5) | 0.56 | 0.28–1.13 | 0.105 |

| 51–60 | 34 (9.1) | 16 (1.6) | 2.08 | 0.93–4.62 | 0.074 |

| 61–70 | 20 (5.4) | 13 (1.3) | 1.27 | 0.50–3.21 | 0.610 |

| 71–80 | 11 (3.0) | 6 (0.6) | 0.76 | 0.21–2.72 | 0.671 |

| 81–90 | 6 (1.6) | 2 (0.2) | 2.31 | 0.21–25.12 | 0.490 |

| >90 | 4 (1.1) | 6 (0.6) | 1.63 | 0.18–15.15 | 0.668 |

| Mean no. of trips to the operating room ± SD | 4.9 ± 4.9 | 2.3 ± 2.6 | 1.15 | 1.09–1.22 | <0.001 |

| Cause | |||||

| Flame | 236 (68.8) | 558 (59.8) | Ref | ||

| Scald | 49 (14.3) | 253 (27.1) | 1.09 | 0.70–1.71 | 0.692 |

| Other | 58 (16.9) | 122 (13.1) | 1.17 | 0.73–1.87 | 0.508 |

| Body site | |||||

| Hand burn | 314 (84.4) | 681 (69.0) | 1.90 | 1.29–2.80 | 0.001 |

| Head/neck burn | 251 (67.8) | 470 (47.9) | 1.31 | 0.93–1.85 | 0.125 |

| Burn perineum | 97 (26.1) | 128 (13.0) | 1.52 | 1.01–2.27 | 0.042 |

| DC range of motion | 290 (78.0) | 541 (54.8) | 2.16 | 1.51–3.07 | <0.001 |

Ref, reference; %TBSA, percentage total body surface area burned; IQR, interquartile range; DC, discharge.

Includes unknown, Veterans Affairs, and self-pay.

Number of trips to the operating room at index admission was significantly correlated with subsequent reconstructive procedures. Compared to participants that did not undergo reconstructive surgery, those undergoing reconstruction underwent 2.6 more operations during their index admission (OR, 1.15; 95 percent CI, 1.09 to 1.22; p < 0.001). Burn size and cause were not associated with the incidence of reconstructive operations. However, location of burn was correlated; participants with burns involving the hand (OR, 1.90; 95 percent CI, 1.29 to 2.80; p = 0.001) or perineum (OR, 1.52; 95 percent CI, 1.01 to 2.27; p = 0.042) were significantly more likely to undergo reconstructive operations. Finally, documented range-of-motion limitation at discharge was a significant predictor of subsequent reconstructive operations, such that 78 percent of all participants undergoing reconstructive surgery (i.e., scar, contracture, or wound) had reduced range of motion at discharge from index admission (OR, 2.16; 95 percent CI, 1.51 to 3.07). The overall C statistic for this model was 0.76, indicating a good fit.

Short Form-12 and Veterans RAND 12 Scores following Discharge with Average Treatment Effects of Reconstructive Operations by Type

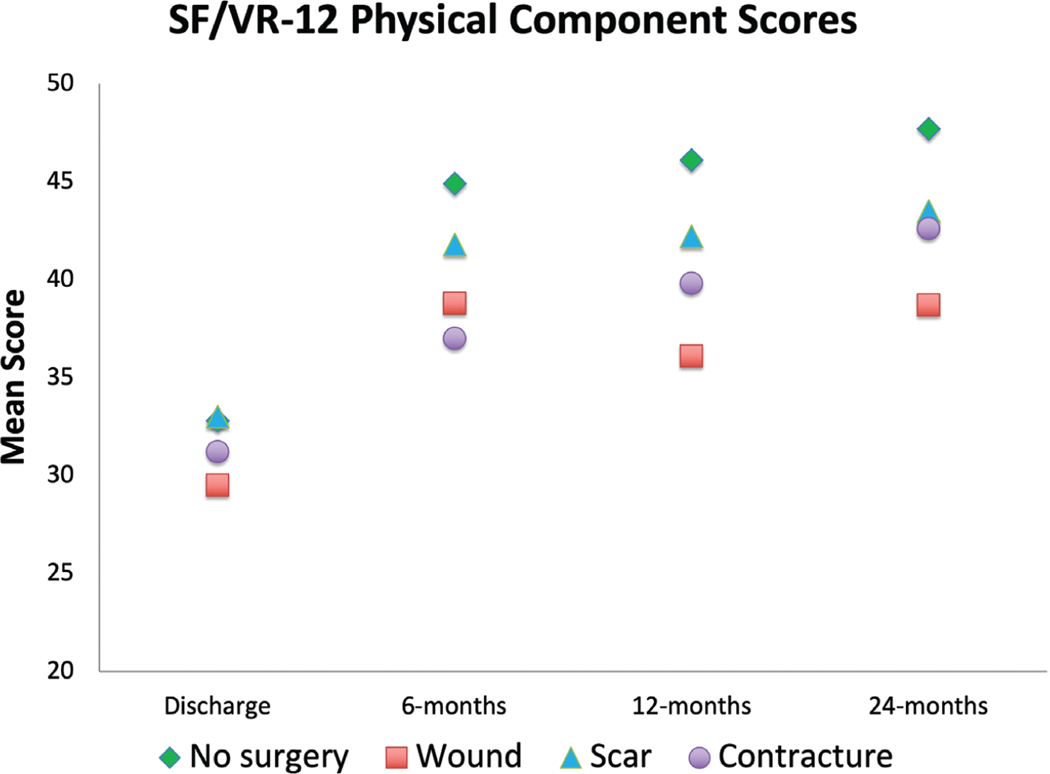

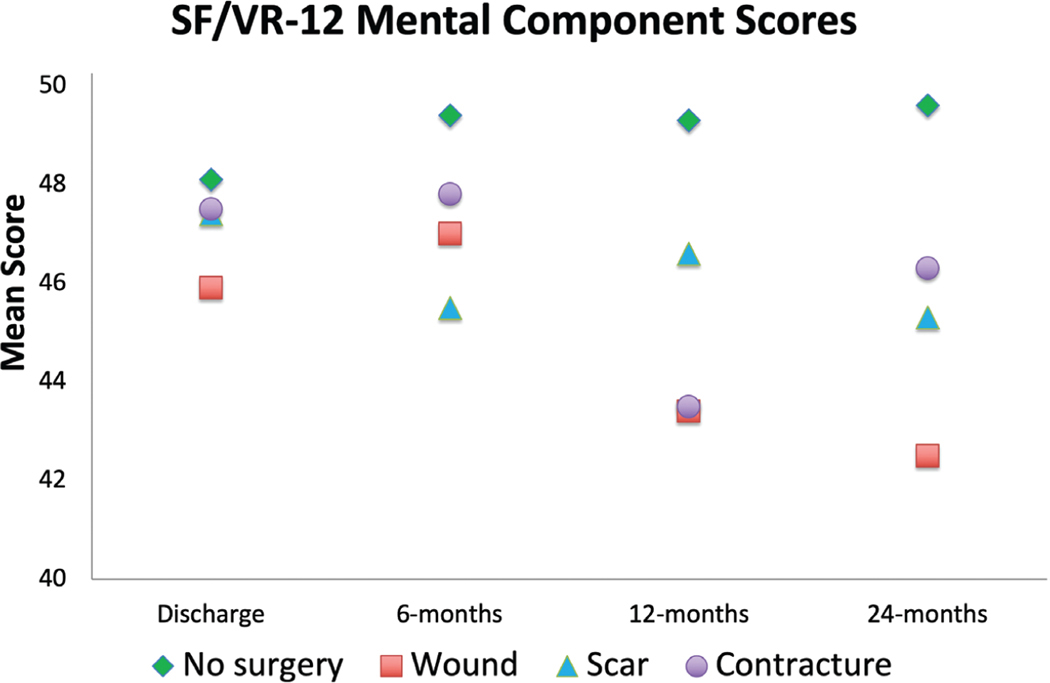

Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 physical component summary scores increased for most participants 24 months after injury, except those undergoing wound-related operations (Fig. 4). Likewise, Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 mental health summary scores increased for participants not undergoing surgery over time; the surgical cohort’s scores stagnated or declined over the 24-month period (Fig. 5). Mean standard differences were all less than or equal to 0.10 after propensity score matching.

Fig. 4.

Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 physical component summary scores at follow-up time points. SF, Short Form-12; VR-12, Veterans RAND 12.

Fig. 5.

Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 mental component summary scores at follow-up time points. SF, Short Form-12; VR-12, Veterans RAND 12.

For the cohort undergoing wound-related surgery between 0 and 6 months after injury, there were no significant differences in physical component scores in the first 12 months; however, at the 24-month follow-up, scores were 4.1 points lower, consistent with poorer quality of life (p = 0.045) (Table 2). Likewise, participants who underwent wound-related surgery between 6 and 12 months after injury reported physical component summary scores 5.7 points lower than matched controls at the 12-month follow-up (p = 0.009). Those undergoing wound-related surgery between 12 and 24 months after injury demonstrated mental component summary scores 6.3 points lower than matched controls (p = 0.009).

Table 2.

Short Form-12/Veterans RAND Physical and Mental Component Summary Scores for Wound Surgery*

| 6 Mo | 12 Mo | 24 Mo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Average Treatment Effects | p | Average Treatment Effects | p | Average Treatment Effects | p | |

| Physical component scores* | ||||||

| 0–6 | −1.2 | 0.555 | −2.2 | 0.242 | −4.1 | 0.045 |

| >6–12 | −5.7 | 0.009 | −2.6 | 0.402 | ||

| >12–24 | −0.9 | 0.719 | ||||

| Mental component scores | ||||||

| 0–6 | 0.1 | 0.979 | 5.3 | 0.039 | 4.9 | 0.128 |

| >6–12 | −4.5 | 0.041 | −1.2 | 0.056 | ||

| >12–24 | −6.3 | 0.009 | ||||

The p values represent the significance in mean difference of Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores between the surgical and nonsurgical cohorts at the follow-up time point. Average treatment effects are the mean differences in Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores between those participants who underwent surgery vs. those who did not undergo surgery. The positivity or negativity of the value implies a positive or negative difference between the matched groups. The p values represent the statistical significance of the mean difference in Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores.

Surgery timing (months after injury).

For those participants undergoing scar-related operations within 6 months of injury, there were no significant differences in physical component scores at any follow-up time point (Table 3). For those undergoing surgery between 6 and 12 months after injury, physical component scores were significantly higher by 4.1 points at 24 months (p = 0.010). Similarly, scores were 1.0 point higher at the 24-month visit for participants undergoing surgery between 12 and 24 months after injury (p = 0.036).

Table 3.

Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 Physical and Mental Component Summary Scores for Scar Surgery*

| 6 Mo | 12 Mo | 24 Mo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Average Treatment Effects | p | Average Treatment Effects | p | Average Treatment Effects | p | |

| Physical component score | ||||||

| 0–6 | −0.9 | 0.684 | −2.4 | 0.202 | 1.7 | 0.406 |

| >6–12 | 0.4 | 0.821 | −2.1 | 0.239 | ||

| >12–24 | −3.3 | 0.055 | ||||

| Mental component score | ||||||

| 0–6 | 1.5 | 0.558 | −3.0 | 0.314 | −1.2 | 0.640 |

| >6–12 | −5.4 | 0.012 | −3.3 | 0.019 | ||

| >12–24 | −0.3 | 0.096 | ||||

The p values represent the significance in mean difference of Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores between the surgical and nonsurgical cohorts at the follow-up time point. Average treatment effects are the mean differences in Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores between those participants who underwent surgery vs. those who did not undergo surgery. The positivity or negativity of the value implies a positive or negative difference between the matched groups. The p values represent the statistical significance of the mean difference in Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores.

For the contracture surgery cohort, there were no significant differences in physical component scores at any time point (Table 4). Mental component scores were significantly lower at 12 and 24 months after injury for those undergoing surgery 6 to 12 months after injury (p = 0.012 and p = 0.019).

Table 4.

Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 Physical and Mental Component Summary Score for Contracture Surgery*

| 6 Mo | 12 Mo | 24 Mo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Average Treatment Effects | p | Average Treatment Effects | p | Average Treatment Effects | p | |

| Physical component score | ||||||

| 0–6 | 1.6 | 0.426 | 1.0 | 0.644 | 1.6 | 0.515 |

| >6–12 | — | — | 3.7 | 0.082 | 4.1 | 0.010 |

| >12–24 | — | — | — | — | 1.0 | 0.036 |

| Mental component scores | ||||||

| 0–6 | −4.3 | 0.157 | −5.2 | 0.056 | −0.8 | 0.800 |

| >6–12 | — | — | 1.2 | 0.534 | −0.3 | 0.928 |

| >12–24 | — | — | — | — | 0.2 | 0.931 |

The p values represent the significance in mean difference of Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores between the surgical and nonsurgical cohorts at the follow-up time point. Average treatment effects are the mean differences in Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores between those participants who underwent surgery vs. those who did not undergo surgery. The positivity or negativity of the value implies a positive or negative difference between the matched groups. The p values represent the statistical significance of the mean difference in Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores.

DISCUSSION

Our study represents the largest prospective analysis of health-related quality of life following reconstructive surgery in burn patients. For wound-related surgery, declining physical component scores over time suggest that the burden of ongoing wound care may be similar to what has been reported in the diabetic wound literature.11 Nonhealing ulcers have been strongly associated with declines in 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey scores because of ongoing dressing changes. Surprisingly, contracture-related operations showed no significant changes in physical component summary scores, even though these operations should theoretically improve physical function.

The relationship between scars and health-related quality of life is complicated and complex. One might speculate that if scarring were severe enough to cause contracture, it would compromise health-related quality of life through various mechanisms. For one, contractures limit range of motion, which may interfere with activities of daily living. Psychologically, one would assume that amelioration of scar contractures would improve health-related quality of life. Our data showed increases in Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 scores for participants undergoing contracture-related surgery, but these gains in health-related quality of life were not greater than what would be expected in a similar burn survivor who did not undergo surgery. Some participants in this study may have undergone staged procedures, and the 24-month study period was insufficient to capture the ultimate gains in health-related quality of life. Alternatively, there may be a subset of patients who did have improved health-related quality of life, but a less satisfied group eclipsed them.

The timing of non–contracture scar–related surgery appeared to influence health-related quality of life. Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 physical component scores at the 24-month post-burn visit were significantly higher for participants undergoing scar operations at 6 to 12 months after burn and 12 to 24 months after burn. This was not observed for participants undergoing surgery within 6 months after burn. Prior longitudinal studies evaluating burn-related scars with health questionnaires12 have demonstrated that scars severity improves from 3 months to 12 months after injury. It is possible that the group of participants undergoing scar surgery before 6 months after injury were too early in the scar maturation process to benefit.

The Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 instrument has been used widely in varied surgical settings, including spine surgery,13 prostatectomy,14 and knee arthroplasty.15 Furthermore, the Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 has been used extensively in evaluating burn outcomes within the Burn Model System database.16,17 Whereas the data in this study did not show significant gains in health-related quality of life related to contracture surgery, this does not indicate futility. Participants undergoing contracture-related operations might have experienced other benefits that are not addressed by the Short Form12/Veterans RAND 12 instrument. Other investigations of outcomes following reconstructive surgery have used scar-centric instruments such as the Vancouver Scar Scale,18 the University of North Carolina 4P,10 the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale,19 the Brisbane Burn Scar Impact Profile,20 or the Scar-Q.21 These instruments are sensitive to changes in scar, but lack information on more generic health-related quality of life. Use of instruments developed to measure burn-related health-related quality of life, including the Burn Specific Health Scale,22 the Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation,23 and the Burn Outcome Questionnaire,24 may demonstrate that reconstructive surgery for nonhealing wounds, scars, and contractures improves health-related quality of life.

Whereas other publications report up to a 72 percent prevalence of hypertrophic scarring after burn injuries,4 none have specifically addressed the percentage of burn survivors who undergo reconstructive surgery. Our study indicates that 27.4 percent of participants report a burn-related operation within 24 months of injury. Most predictors of surgery were self-explanatory, such as range-of-motion limitations at discharge and number of operations during initial hospitalization. More difficult to explain is why participants with Medicaid insurance were significantly less likely to undergo reconstructive surgery. Because approximately 52.3 percent of U.S. burn patients are insured by Medicaid, understanding barriers to care is essential.25 Those insured by Medicaid may experience unique challenges that interfere with access to reconstructive surgery, such as inadequate social support,26 inability to leave work, and limited transportation.27 From a provider vantage, Medicaid reimburses less than commercial payers, resulting in few providers who accept this form of insurance.28 Alternatively, Medicaid authorization for semielective operations could be more stringent or limited. The burn community should be aware of the potential legislative gains regarding reimbursement for postmastectomy reconstruction,29 which could be considered as a framework for improving access to reconstructive burn surgery. Additional investigations could also evaluate how Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act has increased the percentage of burn survivors who undergo reconstructive surgery.

Whether a patient undergoes reconstructive surgery depends on other intangible factors related to the surgeon and patient. Because a patient might be offered several surgical opinions, reconstructive burn operations are preferencesensitive.30 However, surgeon consensus about appropriate reconstructive procedures is lacking. Variation likely exists in both a binary dimension (i.e., whether to perform surgery at all) and a contextual dimension (i.e., which operation). Current discussions in elective and semielective surgical planning recommend a process of shared decision-making, explicitly considering patient preferences and well-being.31 Decision aids such as interactive electronic modules and videos are at the cutting-edge of this process, and have been validated in other fields with preference-sensitive surgery.32–34 Challenges exist in designing tools for reconstructive burn surgery, including difficulties in predicting functional outcomes and how these translate into health-related quality of life. In other surgical scenarios such as breast reconstruction and prostate cancer treatment where decision aids have proven helpful,35,36 the clinical problem is clearly defined in terms of specific anatomy and outcomes. Scarring in burn survivors is highly variable, and no two scars or patients are exactly the same.

Limitations

The control group for our study was composed of participants who were matched with the reconstructive surgery group based on predictor variables from the logistic regression. Although this attempted to lessen confounding by indication, there are likely residual confounders that are not captured in the Burn Model System database. For one, we have no means of knowing the severity of any scar or contracture, which presents the greatest difficulty in truly knowing the effects of reconstructive operations. Through propensity score matching, we assumed that patients with a similar severity of burn and hospital course had similar scarring; however, this may not be true. It is possible that patients who did not undergo surgery had less scarring, even though their burns were similar. Currently, there is no investigation (or data set) dedicated to scar or reconstructive operations in burn patients. Creating such a repository could benefit the burn survivor population through understanding the effects of scar on patient-reported outcomes and how surgery changes health-related quality of life.

The survey response rate for postdischarge surgery was 34.5 percent, which questions how nonresponse bias37 could confound our results. Possibly, participants who did not undergo surgery simply ignored the question, implying that a nonresponse was equal to a no. This could confound our comparator group (i.e., no surgery) given that it misses many burn survivors who simply did not answer. In contrast, it is also possible that participants who had a bad experience with surgery might have skipped the question, which could bias the results toward higher satisfaction in the surgical cohorts.

Our analysis of wound-related operations was unable to account for patients who were discharged earlier in their treatment course with planned return to the operating room for débridement and grafting. The Burn Model System data set does not capture the surgical plan or intent at discharge, which could potentially confound our results for the wound surgery cohort. Also, some participants surveyed in this study underwent different types of operations within each time point (e.g., scar at 6 months and contracture at 12 months); thus, for these scenarios, we were unable to attribute changes in health-related quality of life to specific types of reconstructive surgery.

CONCLUSIONS

Range-of-motion limitations at discharge, frequency of operations during index hospitalization, and hand/perineal burns were associated with increased likelihood of reconstructive surgery in the rehabilitation period. Participants with Medicaid insurance were significantly less likely to undergo reconstructive operations compared to privately insured participants. Health-related quality of life declined in participants with ongoing treatment of open wounds. Conversely, Short Form-12/Veterans RAND 12 physical component scores showed significant increases in scar-related surgery for those undergoing operations after 6 months after injury. Contracture-related operations were not associated with differences in health-related quality of life, regardless of timing. Our data raise critical questions about access to reconstructive surgery and the benefits of reconstructive surgery on health-related quality of life in burn survivors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The content of this publication was developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (no. 90DPBU0004). The National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research is a center within the Administration for Community Living, Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

DISCLAIMER

The content of this publication does not necessarily represent the policy of the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research; the Administration for Community Living; or the Department of Health and Human Services, and one should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures related to this article.

PSYCHOSOCIAL INSIGHTS

Dr. David B. Sarwer, associate dean for research, professor of social and behavioral sciences, director of the Center for Obesity Research and Education, College of Public Health, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pa.

Individuals recovering from burn injuries can challenge the most experienced multi-disciplinary plastic surgery teams and burn centers. Many burn survivors deal with limitations in physical functioning and pain. Others suffer from the psychosocial burden of their injuries. Some report guilt over the event that led to their injuries. Still others may believe that their burns were a “punishment” for specific life choices. Their scars, regardless of the size, are a lifelong reminder of the horror they experienced.

This large study of burn survivors provides important information on the quality of life of those who undergo additional reconstructive procedures. Recruiting patients from the Burn Model Systems National Database, the authors assessed changes in quality of life at 6, 12, and 24 months after the injury with the Short Form-12, a psychometrically valid, abbreviated version of the Short Form-36, the gold standard measure of health-related quality of life. More than one-quarter of participants reported at least one reconstructive procedure in the first 2 years after the injury. Likelihood of a reconstructive procedure was predicted by the number of initial procedures, the location of the burn (hand or perineal involvement), and limited range of motion. Those who underwent a reconstructive procedure more than 6 months after the injury, compared with those who did not, reported significant improvements on the physical component of the Short Form-12. No changes on the mental component subscales were observed.

Reconstructive plastic surgical procedures are typically undertaken with the goal of improving physical functioning but also lessening the psychosocial burden of the residual disability and disfigurement from the original injury or illness. Thus, it is surprising and disappointing that the study did not find additional improvements in self-reported, health-related quality of life. This may be explained in a number of ways. First, as the authors note, the relationship between scars and health-related quality of life is complex. Variables of the scar—size, location, visibility to others, and so on—may influence the impact on quality of life and psychosocial functioning more generally. Unfortunately, it appears that these data were not readily available in the Burn Model Systems National Database. Both the database and future studies in this area are recommended to collect these important data.

Second, data on the impact of the scar on physical functioning also appear to have been limited. As the authors again note, scar contractures may limit range of motion, which would impact physical functioning. Surgical treatment would have the potential to improve this, but that was not consistently seen in the present study.

Finally, while the Short Form-12 is a psychometrically validated, patient-reported outcome measure, it provides a rather general assessment of health-related quality of life. Thus, it may not be specific enough to have detected the relevant changes in physical and psychosocial functioning experienced by burn survivors who undergo additional reconstructive procedures. Measures such as the recently developed SCAR-Q hold great potential to provide more granular information on the unique experiences of burn survivors who seek additional treatment for their scars.

There is a great need for additional, high-quality, prospective studies on the physical and psychosocial experiences of burn survivors. These studies should strive to recruit large sample sizes and use validated measures to assess outcomes, as done in the present investigation. At the same time, the assessment of other domains not included here should be considered. Body image is an important domain of quality of life. There are several widely used, validated measures of body image that would provide relevant insight into the appearance concerns of burn survivors. Unfortunately, neither the Short Form-12 nor the Short Form-36 directly assesses body image.

Finally, symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in burn survivors are highly relevant and can have a profound impact on psychosocial functioning even years after the original injury. A burn scar, regardless of its location, serves as a daily reminder of the horror of the injury. Researchers, as well as members of the treatment team, are encouraged to assess for symptoms of posttraumatic stress—arousal, re-experiencing, and avoidance—at all clinical contacts. Posttraumatic stress disorder can be effectively treated by cognitive-behavioral psychotherapeutic interventions, and referrals to mental health professionals with this expertise should be routinely made for patients with symptoms of the disorder.

Disclosure: Dr. Sarwer currently has grant funding from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disease (R01-DK-108628–01), the U.S. Department of Defense, and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (PA CURE). He is a member of the board of directors of the American Board of Plastic Surgery and the Aesthetic Surgery Education and Research Foundation. He has consulting relationships with Ethicon, Merz, and Novo Nordisk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koljonen V, Laitila M, Sintonen H, Roine RP. Health-related quality of life of hospitalized patients with burns: Comparison with general population and a 2-year follow-up. Burns 2013;39:451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh H, Boo S. Quality of life and mediating role of patient scar assessment in burn patients. Burns 2017;43:1212–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anzarut A, Chen M, Shankowsky H, Tredget EE. Quality-of-life and outcome predictors following massive burn injury. Plast Reconstr Surg, 2005;116:791–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence JW, Mason ST, Schomer K, Klein MB. Epidemiology and impact of scarring after burn injury: A systematic review of the literature. J Burn Care Res, 2012;33:136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Data and Statistical Center; National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research. Burn Model System (Internet). Available at: http://burn-data.washington.edu/. Accessed April 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burn Model System: National Data and Statistical Center. Guidelines for collection of follow-up data: Standard operating procedure (Internet). Available at: http://burn-data.washington.edu/sites/burndata/files/files/105BMS%20-%20Guidelines%20for%20Collection%20of%20Follow-up%20Data2015-12-21.pdf. Accessed April 23, 2019.

- 7.Kazis LE, Lee A, Spiro A, et al. Measurement comparisons of the medical outcomes study and veterans SF-36 health survey. Health Care Financ Rev, 2004;25:43–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selim AJ, Rogers W, Fleishman JA, et al. Updated U.S. population standard for the Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey (VR-12). Qual Life Res, 2009;18:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiro A, Rogers WH, Qian S, Kazis LE. Imputing physical and mental summary scores (PCS and MCS) for the Veterans SF-12 Health Survey in the context of missing data. Available at: https://www.hosonline.org/globalassets/hos-online/publications/hos_veterans_12_imputation.pdf. Accessed April 23, 2019.

- 10.Hultman CS, Friedstat JS, Edkins RE, Cairns BA, Meyer AA. Laser resurfacing and remodeling of hypertrophic burn scars: The results of a large, prospective, before-after cohort study, with long-term follow-up. Ann Surg, 2014;260:519–529; discussion 529–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribu L, Birkeland K, Hanestad BR, Moum T, Rustoen T. A longitudinal study of patients with diabetes and foot ulcers and their health-related quality of life: Wound healing and quality-of-life changes. J Diabetes Complications 2008;22:400–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Wal MB, Vloemans JF, Tuinebreijer WE, et al. Outcome after burns: An observational study on burn scar maturation and predictors for severe scarring. Wound Repair Regen, 2012;20:676–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh A, Gnanalingham K, Casey A, Crockard A. Quality of life assessment using the Short Form-12 (SF-12) questionnaire in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy: Comparison with SF-36. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:639–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA, et al. ; ProtecT Study Group. Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med, 2016;375:1425–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webster KE, Feller JA. Comparison of the short form12 (SF-12) health status questionnaire with the SF-36 in patients with knee osteoarthritis who have replacement surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2016;24:2620–2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goverman J, Mathews K, Holavanahalli RK, et al. The National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research Burn Model System: Twenty years of contributions to clinical service and research. J Burn Care Res, 2017;38:e240–e253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller T, Bhattacharya S, Zamula W, et al. Quality-of-life loss of people admitted to burn centers, United States. Qual Life Res, 2013;22:2293–2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baryza MJ, Baryza GA. The Vancouver Scar Scale: An administration tool and its interrater reliability. J Burn Care Rehabil, 1995;16:535–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Draaijers LJ, Tempelman FR, Botman YA, et al. The patient and observer scar assessment scale: A reliable and feasible tool for scar evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg, 2004;113:1960–1965; discussion 1966–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tyack Z, Ziviani J, Kimble R, et al. Measuring the impact of burn scarring on health-related quality of life: Development and preliminary content validation of the Brisbane Burn Scar Impact Profile (BBSIP) for children and adults. Burns 2015;41:1405–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klassen AF, Ziolkowski N, Mundy LR, et al. Development of a new patient-reported outcome instrument to evaluate treatments for scars: The SCAR-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2018;6:e1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kildal M, Andersson G, Fugl-Meyer AR, Lannerstam K, Gerdin B. Development of a brief version of the Burn Specific Health Scale (BSHS-B). J Trauma 2001;51: 740–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kazis LE, Marino M, Ni P, et al. Development of the life impact burn recovery evaluation (LIBRE) profile: Assessing burn survivors’ social participation. Qual Life Res, 2017;26:2851–2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daltroy LH, Liang MH, Phillips CB, et al. American Burn Association/Shriners Hospitals for Children burn outcomes questionnaire: Construction and psychometric properties. J Burn Care Rehabil, 2000;21:29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duquette S, Soleimani T, Hartman B, Tahiri Y, Sood R, Tholpady S. Does payer type influence pediatric burn outcomes? A national study using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Kids’ Inpatient Database. J Burn Care Res, 2016;37:314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Witgert K. Why Medicaid is the platform best suited for addressing both health care and social needs. Health Affairs (Internet). September 7, 2017. Available at: 10.1377/hblog20170907.061853/full/. Accessed June 10, 2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: Transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health 2013;38:976–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skaggs DL, Clemens SM, Vitale MG, Femino JD, Kay RM. Access to orthopedic care for children with medicaid versus private insurance in California. Pediatrics 2001;107:1405–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berlin NL, Wilkins EG, Alderman AK. Addressing continued disparities in access to breast reconstruction on the 20th anniversary of the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act. JAMA Surg, 2018;153:603–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birkmeyer JD, Reames BN, McCulloch P, Carr AJ, Campbell WB, Wennberg JE. Understanding of regional variation in the use of surgery. Lancet 2013;382:1121–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oshima Lee E, Emanuel EJ. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. N Engl J Med, 2013;368:6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee CN, Deal AM, Huh R, et al. Quality of patient decisions about breast reconstruction after mastectomy. JAMA Surg, 2017;152:741–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, Walker E, Watson P, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ 2010;341:c5146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knops AM, Legemate DA, Goossens A, Bossuyt PM, Ubbink DT. Decision aids for patients facing a surgical treatment decision: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg, 2013;257:860–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luan A, Hui KJ, Remington AC, Liu X, Lee GK. Effects of a novel decision aid for breast reconstruction: A randomized prospective trial. Ann Plast Surg, 2016;76(Suppl 3):S249–S254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin GA, Aaronson DS, Knight SJ, Carroll PR, Dudley RA. Patient decision aids for prostate cancer treatment: A systematic review of the literature. CA Cancer J Clin, 2009;59:379–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson TP, Wislar JS. Response rates and nonresponse errors in surveys. JAMA 2012;307:1805–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]