Abstract

Absorption-based spectroscopy in the mid-infrared (MIR) spectral range (i.e., 2.5–25 μm) is an excellent choice for directly sensing trace gas analytes providing discriminatory molecular information due to inherently specific fundamental vibrational, rovibrational, and rotational transitions. Complimentarily, the miniaturization of optical components has aided the utility of optical sensing techniques in a wide variety of application scenarios that demand compact, portable, easy-to-use, and robust analytical platforms yet providing suitable accuracy, sensitivity, and selectivity. While MIR sensing technologies have clearly benefitted from the development of advanced on-chip light sources such as quantum cascade and interband cascade lasers and equally small MIR detectors, less attention has been paid to the development of modular/tailored waveguide technologies reproducibly and reliably interfacing photons with sample molecules in a compact format. In this context, the first generation of a new type of hollow waveguides gas cells—the so-called substrate-integrated hollow waveguides (iHWG)—with unprecedented compact dimensions published by the research team of Mizaikoff and collaborators has led to a paradigm change in optical transducer technology for gas sensors. Features of iHWGs included an adaptable (i.e., designable) well-defined optical path length via the integration of meandered hollow waveguide structures at virtually any desired dimension and geometry into an otherwise planar substrate, a high degree of robustness, compactness, and cost-effectiveness in fabrication. Moreover, only a few hundred microliters of gas samples are required for analysis, resulting in short sample transient times facilitating a real-time monitoring of gaseous species in virtually any concentration range. In this review, we give an overview of recent advancements and achievements since their introduction eight years ago, focusing on the development of iHWG-based mid-infrared sensor technologies. Highlighted applications ranging from clinical diagnostics to environmental and industrial monitoring scenarios will be contrasted by future trends, challenges, and opportunities for the development of next-generation portable optical gas-sensing platforms that take advantage of a modular and tailorable device design.

Keywords: substrate-integrated hollow waveguides, gas sensors, mid-infrared sensing technology, hollow waveguides, chemical sensors

1. Background

1.1. Gas Sensing Based on Molecular Absorption in the Mid-Infrared Range

Optical methods based on light absorption at a specific wavelength are a powerful tool for the development of sensors for the identification and quantification of inorganic and organic species in liquid, solid, or gaseous phases. Within the electromagnetic spectrum, the mid-infrared spectral range (MIR)—from 2.5 to 25 μm—is an excellent choice for providing inherent molecular specific fundamental vibrational, rovibrational, and rotational absorption bands enabling the identification of molecular structures via their fingerprint spectra.1 In particular, the detection of gaseous species is preferably performed by infrared absorption spectroscopy, as the vast majority of gaseous substances exhibits specific absorption bands in the MIR resulting in remarkable selectivity toward a variety of gas-sensing applications.2

Conventional absorption spectroscopy associates the amount of light absorbed by atoms or molecules in a sample with their concentration upon an interaction of radiation.3 Generally, the transmitted light after passing through the sample with intensity (I) and the incident light (I0) are related to the analyte concentration, the absorption coefficient of the sample at a certain wavelength α(λ), and the optical path length (L) as formalized by the Beer–Lambert law.

| 1 |

The absorption cross-section (σ) is a wavelength-dependent parameter used to specify absorption properties of a certain molecular species, and it has an area unit (e.g., cm–2). The gas-absorption cross-section is a practical value employed to characterize the ability of a species to absorb light.4 The concentration of a certain molecule (C) is then determined via the relation with the absorption coefficient and the absorption cross-section as follows.

| 2 |

Additionally, the concentration C (i.e., the number of molecules (N) per unit of volume) of an absorbing specie is also a function of temperature T (K) and pressure P (atm), as described by eq 3, where N is the number density (2.6875 × 1019 mol cm–3) of an ideal gas at T0 of 273.15 K and P0 of 1 atm. The temperature and pressure dependences give rise to a certain line shape centered around the central absorption frequency.5,6 Therefore, the relation between an absorption profile and the concentration is more accurately derived by integrating across an entire absorption contour. This is expressed by the total single-pass absorbance A defined by eq 4.

| 3 |

| 4 |

Finally, the absorbance A of the analyte can be determined via the absorption coefficient and the length L of the absorbing medium (also known as (aka) the absorption path length). While A is indeed unitless, it is frequently described in absorption units (AU) and is related to the analyte concentration (C) as

| 5 |

where S is the absorption line strength defined as

| 6 |

The absorption spectrum displays the absorbance A as a function of wavelength (e.g., nm or μm) or wavenumber (e.g., cm–1) with the latter commonly used particularly in mid-infrared spectroscopy. Figure 1 shows exemplary mid-infrared spectra of selected relevant gases analyzed in environmental, medical diagnostic, and industrial application scenarios.

Figure 1.

MIR absorption spectra of selected relevant molecules addressed in a wide range of application scenarios. H2O: water; CO2: carbon dioxide; CO: carbon monoxide; NO: nitric oxide; NO2; nitrogen dioxide; CH4: methane; O3: ozone; NH3: ammonia. Reprinted with permission from Khan, S.; Newport, D.; Le Calvé, S. Gas Detection Using Portable Deep-UV Absorption. Sensors 2019, 19(23), 5210. Copyright 2019. MDPI.

1.2. Advances in Mid-Infrared Technology

With the application of near-infrared (NIR) as the standard wavelength regime for optical telecommunications (i.e., 1.55 μm) in the 1980s, the rapid growth of optoelectronic components technology provided remarkable performance levels of the corresponding light sources (e.g., laser diodes), waveguides, and detectors.1 Hence, spectroscopy techniques used for sensing schemes in the NIR regime (i.e., 800–2500 nm) have tremendously benefited from these advancements in terms of performance and cost-effectiveness. In contrast, the mid-infrared regime requires a wider variety of materials and optical components compared to the rather narrow NIR spectral band. In addition, optical materials used in the visible (VIS) and NIR regions are not transparent at the mid-infrared frequencies affecting, for example, the choice of waveguide materials. Likewise, the most commonly used semiconductor material in NIR radiation detection (i.e., Si) is less suitable in the MIR. Toward higher frequencies, a recent development in diode-based light sources such as (organic) light-emitting diodes (o)LEDs enabled the advancements of sensing technologies in VIS and UV spectroscopy and sensing.

The boost promoted by advances in optoelectronic components combined with the introduction of the miniaturization concepts—which resulted in the decrease of entire sensing devices—benefited sensing technologies in the UV/VIS/NIR spectral regime. This fact directly relates to the increase in the number of publications concerning absorption-based optical sensing techniques in the 200–2500 nm regime.3,8 However, as previously mentioned, no other spectral range offers the level of inherent selectivity provided by the MIR spectral window, especially for gaseous compounds. Moreover, multivariate statistical tools (aka chemometrics) provide enhanced data evaluation enabling the discrimination and quantification of multiple compounds in complex mixtures. Therefore, sensing devices based on MIR absorption spectroscopy are undoubtedly the most flexible strategy for monitoring gaseous species.7,9

Fundamentally, the instrumentation for absorption spectroscopy comprises a light source, a wavelength selector (i.e., filter, prism, grating, interferometer, etc.), a sample cell with a defined absorption path length, and a detection device. The typical instrument for absorption spectroscopy in the MIR is a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer, which employs a broadband light-enabling multianalyte detection. FTIR spectroscopy is based on the measurement of an interferogram via an interferometer. To create spectral data (i.e., in the frequency domain), a Fourier transform converts the interferogram (i.e., from the time domain). FTIR spectrometers provide improved signal-to-noise ratios (S/N) compared to dispersive spectrometers via the so-called multiplex advantage (i.e., providing the entire IR spectrum at once), allowing signal averaging by combining individual scans, and high optical throughput, as no slit is required.10

While FTIR spectroscopy has been used for analyzing a wide range of molecules, a miniaturization toward “IR-lab-on-a-chip” certainly has its limitations. The breakthrough facilitating this level of miniaturization has certainly been the advancement of MIR semiconductor laser technology evolving from initially heterostructure lead-salt laser diodes to—in part even broadly tunable—quantum cascade lasers (QCLs) and interband cascade lasers (ICLs), which are nowadays considered the most advanced state-of-the-art MIR light sources. With the increasing commercial availability of QCLs and ICLs, the development of robust, highly selective, and sensitive laser spectrometers has gained a high momentum.11−14 Tunable laser absorption spectroscopy (TDLAS) takes advantage of wavelength-tunable lasers with a narrow bandwidth and highly collimated beam, which eliminate the need for a wavelength selector due to the sequential emission of individual wavelengths (i.e., a very narrow wavelength band) tuned across a certain frequency window in milliseconds or less. MIR detectors are usually similar to the devices applied in conventional FTIR spectroscopy, that is, ranging from liquid nitrogen or thermoelectrically cooled mercury–cadmium–telluride (MCT) semiconductor detectors to deuterated glycine trisulfate detectors (DGTS), pyroelectrics, etc. More recently, quantum-well photoconductive devices or quantum cascade detectors have also been introduced providing a miniaturized on-chip format similar to that of QCLs/ICLs. For interested readers, there are excellent reviews available concerning the operation and recent advances on MIR light source and detector technologies used in a variety of sensing devices.1,5−7,13 The focus of the present review is to explore advances in the third crucial component of absorption-based optical sensor devices next to light source and detector: the actual transducer ensuring intimate interactions of molecules and photons!

1.3. Gas Cells: From Multipass Cells to Hollow Fiber Light Pipes

According to eq 5, the absorbance A is related to the absorption path length (L), where light will interact with the molecules. In principle, the detection sensitivity may thus be improved by increasing the optical path length (OPL), extending the molecular interaction with photons. Gas sensors based on absorption spectroscopy have been firstly developed using so-called multipass gas cells to achieve the highest sensitivity.15 Generally, a multipass cell is an optical device that provides an extended absorption path by allowing multiple passes of the radiation through a gas volume residing inside the cell. In MIR absorption spectroscopy this is achieved usually by concave mirrors coated with gold “folding” the IR beam to enable us to obtain OPLs of tens of meters. Additionally, using multipass configurations in so-called “cavity-enhanced” spectroscopies such as cavity ringdown spectroscopy (CRDS) makes OPLs of kilometers possible.16,17 The most commonly used types of multipass cells in conventional gas absorption spectroscopy were developed by Herriot and White in 1962 and 1942, respectively. The so-called Herriot multipass cell and White multipass cell have been extensively used in gas-sensor technology with limits of detection reaching the low part per million regime and below. An interesting arrangement used a Herriot cell incorporated into a weather balloon payload for determining methane and water vapor at an altitude of 32 000 m with OPLs of 74 and 32 m.18 Although multipass gas cells provide extended OPLs enhancing the detection sensitivity, they usually require a time-consuming optical alignment in a rather bulky configuration requiring large volumes of gas sample (i.e., hundreds of milliliters to liters) leading to extended response times preventing monitoring applications that require acceptable temporal resolution (i.e., minutes, seconds, or less). Also, sensing schemes based on multipass cells have issues with temperature stabilization and limitations for corrosive gases. An additional disadvantage is the rather high cost of such cells.

Optical fibers are typically produced with the core of a higher refractive index than the surrounding cladding leading to total internal reflection of the propagating radiation at a range of angles. Single-mode fibers usually employed in telecommunications have core diameters of 5–125 μm, whereas multimode fibers can reach core diameters up to 1000 μm. Using core-only optical fibers facilitates an evanescent field (EF) leaking in a wavelength-dependent manner from the surface of the fiber into an adjacent sample volume, one may probe gas-phase species adjacent to the fiber surface within the penetration depth of the EF (i.e., a few micrometers in the MIR) in a gas cell, which provides lower costs, remote sensing, and simplicity to the sensor device. However, since this is a rather inefficient sensing concept, a general discussion on options and types of optical fiber-based gas sensors—including microstructured optical fiber—is beyond the scope of this review, and the reader is referred to the pertinent literature.3,19

A much more efficient and innovative alternative to increase the sensitivity in waveguide-based gas sensing technologies is the adoption of so-called hollow waveguides (HWGs) in lieu of multipass or solid-core optical fiber gas cells.

Generally, a hollow waveguide is defined as a light pipe with the internal surface made from or coated with a dielectric material or metal (e.g., Al2O3, ZnS/Ag, AgI/Ag, etc.) with a coaxial hollow core enabling radiation propagation by a reflection at the inside walls.20 Although hollow waveguides were initially designed for delivering high peak power laser light in industrial laser applications and for surgical scenarios, they have proven their value also as highly efficient miniaturized gas cells providing exceedingly low hollow core volumes for probing gas samples (i.e., a few milliliters or less). In the late 1970s, the first HWG was produced by Garmire from two strips of aluminum separated by dielectric spacers.21 Cylindrical HWGs were introduced by Miyagi et al. via a deposition of germanium into an aluminum pipe and plating Ni on top.22 Multiple reflections at the metallic inner wall propagate radiation through the air core. A schematic illustration of the described waveguide concept is shown in Figure 2a. The application of HWGs as gas transmission cells was first shown by Saggese et al. in 1991, where a 150 mm long hollow sapphire fiber with a 1.06 mm inner diameter was used for the spectroscopic detection of 20% CO2.23 For the MIR range, an AgI-coated HWG provides excellent light transmission with losses as low as 0.1 db/m at 10.6 μm, whereas Ni-coated tubes with Ge show higher losses. ZnS/Ag-coated HWGs have been employed as an excellent alternative for remote gas sensing, although these materials are not suitable for corrosive gases.24 A typical setup using a cylindrical/fiberoptic HWG coupled to a conventional FTIR spectrometer is shown in Figure 2b.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic layout of the dielectrically coated silica HWG used in the sensor setup. Reprinted in part with permission from Wilk, A., Kim, S.-S., & Mizaikoff, B. An approach to the spectral simulation of infrared hollow waveguide gas sensors. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 395, 1661–1671. Copyright 2009 Springer Nature. (b) Integrated mid-infrared gas-sensing system combining a hollow-core optical fiber gas cell with an FTIR spectrometer. Reprinted in part with permission from Kim, S.-S.; et al. Midinfrared trace gas analysis with single-pass Fourier transform infrared hollow waveguide gas sensors. Appl. Spectrosc. 2009, 63, 331–337. Copyright 2009 OSA Publishing.

Many research groups have demonstrated that HWGs can be efficiently used as miniaturized gas cells providing shorter sensor response times when compared to conventional multipass cells due to small transient volumes of the gaseous analyte. Also, HWGs require a less demanding alignment versus the entire optical system as compared to Herriot or White cells. With this concept, several gases were detected via HWGs, as summarized in Table 1. Although such sensors achieved a reasonable sensitivity due the extended OPL, the integration of HWGs with compact sensing systems is limited by the mechanical flexibility (i.e., instability of the fiberoptic HWG) and the required waveguide length. As described in eq 3, the OPL is directly related to the sensitivity in absorbance-based measurements. Conventional HWG substrates are usually glass, silica, polymer tubes, and even sapphire with outer diameters ∼1 mm, which results in individual mechanical issues and optical outcoupling losses when curved or coiled depending on the material. This results in most IR-HWG sensors being governed in size by the required length of the HWG affecting the operational footprint of the entire device and limiting its utility in application scenarios requiring compact dimensions. While the limited potential for integration into compact systems is a drawback of conventional IR-HWG gas sensors, HWGs have a low beam divergence, and losses are proportional to a–3, where a is defined by the hollow core radius. Yet, HWGs suffer from substantial bending losses, which are proportional to R–1, where R is the bending radius. Hence, signal attenuation losses and mechanical stress due to coiling as well as signal fluctuations arising from the general flexibility of the fiberoptic waveguide format giving rise to mechanical vibrations limit their application as miniaturized transducers in MIR gas sensing in real-world scenarios.

Table 1. Examples of MIR Gas Sensors Based on Conventional Hollow Waveguides (HWG).

| instrumental setup | analyte | LOD | remarks | REF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QCL-DAS | ammonia (NH3) | not specified | Ag/AgI-coated HWG | (29) |

| FTIR-MCT detector | chlorinated aromatic amines | not specified | HWG sampler was coated with SPME | (30) |

| FTIR-MCT detector | dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) | 109.0 ppb | supported capillary membrane sampler (SCMS) | (31) |

| 1,4-dioxane (C4H8O2) | 15.6 ppb | |||

| chloroform (CHCl3) | 750.0 ppb | |||

| FTIR-MCT detector | benzene (C6H6), toluene (C7H8), xylene isomers (C8H10) chloroform (CHCl3) | not specified | HWG coupled to the SCMS | (32) |

| FTIR-MCT detector | ethene (C2H6) | 1.1 ppb | preconcentration of selective sorption tubes | (33) |

| FTIR-MCT detector | carbon monoxide (CO) | not specified | results compared with nondispersive infrared analyzer (NDIR) | (20) |

| nitrogen monoxide (NO) | ||||

| FTIR-MCT detector | methane (CH4) | 14.4 ppb | HWG composed of a silica capillary and a reflective Ag/AgI | (26) |

| carbon dioxide (CO2) | 15.8 ppb | |||

| Ethyl chloride (C2H5Cl) | 199 ppb | |||

| FTIR-MCT detector | methane (CH4), butane (C4H10), and isobutylene (C4H8) | not specified | 3D optical sensor simulation | (25) |

| ultrafast NIR | methane (CH4) | 1.33% (v/v) | Ag/AgI-coated iHWG | (34) |

| FTIR-MCT detector | benzene (C6H6), toluene (C7H8), xylenes (C8H10) | not specified | thermal desorption (TD) | (35) |

| FTIR-MCT detector | isobutylene (C4H8), methane (CH4), butane (C6H6), cyclopropane (C3H6) | not specified | use of chemometrics to improve the molecular selectivity of the spectra | (36) |

2. Substrate-Integrated Hollow Waveguides (iHWGs)

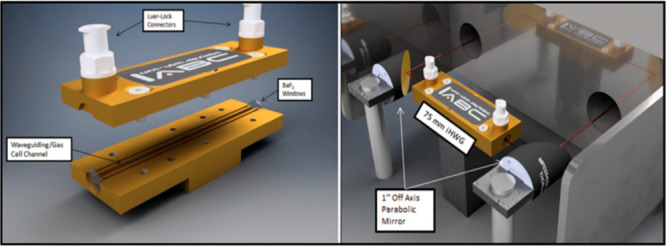

Taking advantage of the hollow waveguide concept yet resolving the main limitation of conventional HWGs, a new generation of hollow waveguide structures has been presented by Mizaikoff and collaborators in 2013.27 The so-called “substrate-integrated hollow waveguide” (iHWG) comprises a rather simple, yet exceedingly efficient, modular concept based on a layered structure, whereby radiation is guided via an integrated straight or meandered light channel fabricated into a solid-state substrate material. Most commonly, iHWGs consist of two elements: (i) the base plate with an integrated mirrorlike hollow channel simultaneously serving as gas cell and for reflective light guiding and (ii) a mirrorlike polished top plate enabling a closing off of the channel and containing access ports to facilitate the introduction of gas samples. Both plates are attached and sealed by either using mechanical clamping devices, such as screws, or glued together (e.g., with epoxy, etc.). MIR-transparent windows (e.g., ZnSe, BaF2, etc.) are glued to the radiation incoupling/outcoupling waveguide channel facet enabling radiation transmission. Figure 3 generically illustrates an assembly and optical configuration of iHWG based sensor systems.

Figure 3.

CAD renderings of (left) a custom 75 mm long straight-channel iHWG (channel cross-section: 4 mm2) equipped with Luer-Lock connectors for the gas inlet/outlet. (right) FTIR spectrometer optically coupled to the iHWG via two off-axis parabolic mirrors (OAPMs). The red line schematically indicates the IR beam path. Reproduced from Kokoric, V., Widmann, D., Wittmann, M., Behm, R. J., & Mizaikoff, B. Infrared spectroscopy: Via substrate-integrated hollow waveguides: A powerful tool in catalysis research. Analyst 2016, 141, 5990–5995 with permission from Royal Society of Chemistry.

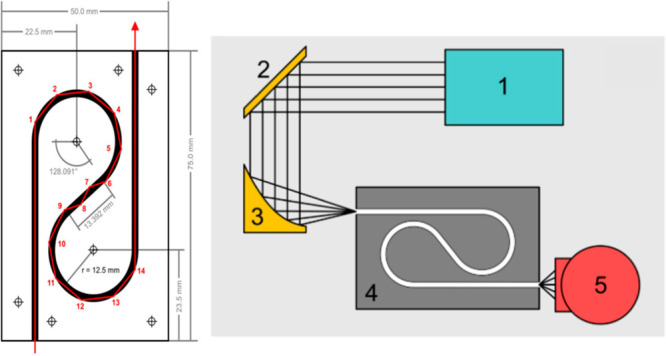

Wilk et al. have developed the first functional iHWG prototype tailored for advanced MIR gas sensing demonstrated for multianalyte quantification. The first generation of iHWGs was fabricated from Al–Mg alloy with substrate dimensions of 75 × 50 × 12 mm (length (L) × width (W) × height (H)) with an open channel cross-section of 4 mm2 and a meandered optical path.27 The waveguide channel was designedwith a “yin-yang” geometry providing an OPL of 22.45 cm, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Scheme of the first iHWG with substrate dimensions, channel geometry, and modeled propagation path of the center IR ray (left). Schematic of the experimental iHWG sensor setup with (1) FTIR spectrometer, (2) planar gold-coated mirror, (3) gold-coated off-axis parabolic mirror (OAPM), (4) iHWG assembly, and (5) MCT detector. The IR beam propagates from component 1 to 5 (right). Reproduced from reference Wilk, A.; et al. Substrate-integrated hollow waveguides: a new level of integration in mid-infrared gas sensing. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 11205–11210. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

In this study, bulk aluminum-based substrates were polished with a fused aluminum oxide/water suspension and subsequently shaped using a solid carbide end mill, resulting in a mirrorlike surface. Thin gold films were furthermore deposited onto the aluminum substrates using sputter deposition techniques for improving IR reflectivity. The final iHWG setup was optically coupled to an FTIR spectrometer via two gold-coated mirrors, and a nitrogen-cooled MCT detector was interfaced with the spectrometer. The analytical performance of the gas-sensing scheme was evaluated analyzing the spectra of several gaseous analytes including isobutylene, methane, cyclopropane, CO2, and butane. Limits of detection (LOD) as low as 5 ppm were achieved.

The innovative modular concept of iHWGs results in a variety of advantages versus conventional (i.e., fiberoptic) hollow waveguides-based sensors including superior mechanical robustness, adaptability (i.e., designability) of the optical path length via an integration of meandered hollow waveguide structures at desired geometries, a wide range of material choice and associated fabrication technologies, and gas sample volumes of a few hundred microliters resulting in exceedingly short transient times facilitating real-time monitoring capabilities. Besides, given the modular concept of iHWGs and the planar substrate integration, the monolithic integration of the gas cell/waveguide with conventional or miniaturized light sources, detector elements, and optical components is facilitated. Since the publication of the first iHWG prototype, this technology has rapidly matured and evolved into a possibly flexible key component improving modular sensing concepts across the board by enabling an application-oriented device design with unsurpassed flexibility.28

3. Exploring the Potential of iHWG-Based Sensors

3.1. Tailoring the Sensitivity Via the Hollow Channel Geometry

With the development of iHWG technology rather than conventional HWG structures, several advantageous features related to optical gas-sensing applications were achieved including: (i) compact sensor dimensions, (ii) rapid response times, (iii) adaptable to house additional optical sensor components (e.g., light source, detector, etc.), (iv) mechanical stability/robustness, (v) inertness against vibrations, and (vi) ease of optical alignment. Additionally, the MIR range provides an inherent molecular selectivity. The application of iHWGs is particularly attractive for scenarios that demand low sample volumes, yet, it requires a high discrimination power and sensitivity at parts per million-parts per billion level concentrations. As mentioned before, according to the Beer–Lambert law, an extended OPL is an interesting concept to improve the limit of detection in absorption-based techniques. Basically, an unlimited variety of waveguide channels designs is potentially achievable resulting in extended optical path lengths integrated into the substrate. However, the number of internal reflections at the inside walls of the iHWG is limited by an attenuation (i.e., reflection losses and surface roughness) resulting in a reduced light throughput and analytical performance. A variety of studies have focused on channel geometry performance evaluation and different device designs. Fortes et al.37 evaluated the geometry and the OPL of straight versus meandered waveguide channels with substrate dimensions of 75 × 55 × 15 mm (L × W × H) in order to maximize the achievable analytical performance in terms of SNR and LOD. Straight iHWGs were designed with a nominal path length of 75 mm and contrasted by one-turn and two-turn meandered waveguides. With the fabrication of iHWGs with a “funnel” light inlet and/or outlet it was found that inlet funnels were beneficial, whereas outlet funnels led to a decreased iHWG sensitivity due to an enhanced beam divergence. Figure 5 shows a variety of waveguide geometries and the experimental design of the study.

Figure 5.

Schematic of optical setup based on Bruker Alpha FTIR (left) and Bruker IRCube (right) spectrometers with integrated iHWGs. Straight iHWG structures; (I) nonflared channel without optical funnel; (II) channel with incoupling funnel; (III) channel with incoupling and outcoupling funnels. (e, f) One-turn and two-turn meandering waveguide channels. (1) IR source, (2) parabolic gold-coated mirrors, (3) iHWG, (4) detector, and (5) FTIR spectrometer. Reprinted with permission from Fortes, P. R.; et al. Optimized design of substrate-integrated hollow waveguides for mid-infrared gas analyzers. J. Opt. 2014, 16, 094006. Copyright 2014 IOP Publishing, Ltd.

Another variety of meandered geometry was explored in the so-called iHEART system, which comprised a heart-shaped iHWG combined with a portable NIR spectrometer (μNIR).38 The iHEART was tailored specifically to the optical arrangement of the μNIR spectrometer. Waveguide channels with a cross-section of 5 mm were milled into a 45 × 50 × 10 mm base substrate made from aluminum alloy and stacked to a matching top plate polished to a mirrorlike surface finish, thus establishing a heart-shaped waveguide with an ∼4.0 cm3 volumetric capacity. Additionally, straight—with different channel dimensions—and dual-channel geometries where the available light was split into equal parts for simultaneously enabling a sample and a reference measurement were explored, as further discussed. An overview on the different channel geometries already applied in IR-iHWG-based gas sensors is summarized in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

iHWG channel geometries (marked in dark gray): (a) straight with and without inlet and/or outlet funnel (lighter gray), (b) meandered one-turn (“yin-yang”), (c) meandered two-turn (“double yin-yang”), (d) coiled channel with reflecting mirror (green) at channel end, (e) heart-shaped, and (f) dual-channel iHWG (optical elements splitting and redirecting the beam marked in green). Red arrows indicate light coming from the source, blue arrows indicate light traveling toward the detector.

3.2. Materials and Fabrication Procedures

Initially, iHWGs were produced from a commercially available aluminum alloy (e.g., Al-MgO3) as a substrate material followed by a surface polishing using diamond suspensions in order to reach a mirrorlike finish. Additionally, thin gold films were deposited onto the substrate surface by sputtering to enhance the IR reflectivity. The quality of the surface expressed as surface roughness was ∼44 ± 11 nm for the waveguide channels, which is classified as a sufficient surface quality for MIR radiation (i.e., 2.5–25 μm) according to the λ/10th criterion.27 Moreover, other polished metals (with/without gold coating) were used as a substrate for iHWG-based gas sensors such as aluminum and brass alloys.

Besides the substrate material, advances in the assembly of iHWG structures were reported. While first a clamping device was used to attach the substrate components with BaF2 windows sealed at the optical ports using an acetoxy cure silicone, finally an epoxy-based glue was used as a less modular yet more robust alternative.39,40 Finally, substrate components have been combined via M4 screws and appropriate O-ring sealings to ensure gas-tightness and modularity.41

A miniaturization of the entire sensing device is dependent on a small footprint of all involved components and includes the light source, the detector, and the iHWG. As previously mentioned, miniaturized laser sources and detectors are readily available, while the development of the iHWG concept finally facilitated miniaturized device platforms. In this context, the size of substrate-integrated hollow waveguides can be tailored according to the sensor and application requirements. For example, an aluminum iHWG with an edge length of 5 cm and a height of 2 cm was used to integrate with a QCL,42 while a 15 cm OPL iHWG was coupled to a benchtop-type FTIR spectrometer for SO2/H2S measurements.43

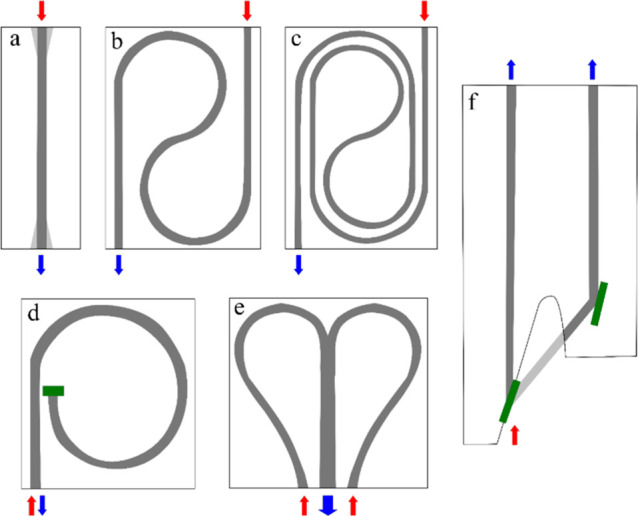

Significant advancements in manufacturing technology for iHWGs involves the usage of low-cost and time-effective prototyping techniques. Stach et al.44 have used three-dimensional (3D) printing for manufacturing iHWGs—the so-called polyHWG—which enhances the flexibility and enables an on-demand or on-site fabrication of miniaturized gas cells.44 PolyHWGs were produced by a fused modeling printer from acrylonitrile, butadiene, and styrene (ABS) filaments. Postprocessing steps (i.e., acetone etching and gold-sputtering) was conducted to decrease the final surface roughness and enhance the reflectivity. PolyHWGs were coupled to both QCL and FTIR light sources and an MCT detector to demonstrate the applicability in gas sensing for the example of CO2 and isopropyl alcohol (Figure 7). With the development of 3D-printed iHWGs a considerable reduction in fabrication cost and rapid fabrication capabilities were demonstrated.

Figure 7.

CAD rendering of the assembled 3D-printed polyHWG (left) and the top plate only (right) illustrating the interior structural features. (a) Waveguiding hollow channel/gas flow cell with diameter of 2 mm. (b) 6 mm diameter intrusions for silicon windows. (c) Gas inlet and outlet channels. (d) Gas inlet and outlet extensions to fit the Luer-lock system (top). MIR sensor system based on polyHWG coupled to a QCL. (a) TEC-cooled MCT detector. (b) polyHWG. (c) QCL light source. Overall system dimensions: ∼20 cm (bottom). Reproduced from Stach, R.; et al. PolyHWG: 3D Printed Substrate-Integrated Hollow Waveguides for Mid-Infrared Gas Sensing. ACS Sensors 2017, 2, 1700–1705. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

3.3. Integrated Sample Pretreatment Strategies

Analytical methods frequently require sample preconcentration and/or (pre)treatment steps prior to obtaining the actual analytical signal (i.e., direct methods) or the product generated by a previous reaction/conversion involving the analyte (i.e., indirect methods).

Two examples of a sample treatment prior to an IR analysis are exemplarily shown herein. Perez-Guaita et al.45 have hyphenated an IR-iHWG sensor with a sample preconcentration device in order to enrich gaseous isoprene prior to the IR analysis, thereby decreasing the detection limit. A 120 mm aluminum cylinder was used as a preconcentrator with an external and internal diameter of 10 and 4.3 mm, respectively, and the absorbent material was placed inside. The preconcentration tube was jacketed with a heating tape connected to a control unit for regulating and controlling the temperature, ensuring reproducible desorption conditions. The preconcentration step enabled a detection limit of 106 ppb for isoprene. Petruci et al.46 have developed a methodology for the online detection of H2S using an FTIR-iHWG device based on the rapid UV-induced conversion of the rather weak IR absorber H2S into the much more pronounced IR absorber SO2. The conversion was performed by exposing gas samples to a conventional UV light (emitting at 185 nm) using a custom quartz tube flow device with the tubular conversion cell coiled around the UV lamp (length of coiled segment: 95 cm). Both studies demonstrated the applicability of sample pretreatment/preconcentration steps in order to enhance the analytical performance of gas sensors. However, these additional steps should be performed in devices that not only enable an automation but also integrate with the compact dimensions of iHWG-based sensors.

In a next step, sample pretreatment/preconcentration devices with a similar footprint as the iHWG and in fact using the very same substrate concept were fabricated from aluminum readily providing a stacking/integration of the devices. The first published device was the so-called iPRECON, which comprises two substrate components made from aluminum with dimensions of 75 × 50 mm (i.e., the same dimensions as the iHWG) containing an internal channel structure housing the absorbent material.47 Luer-Lock connectors were used to attach the preconcentrator with computer-controlled three-way-valves. Recently, a multichannel preconcentrator (muciPRECON) was developed providing several channels each packed with different sorbent materials and integrated into an iHWG sensor device.48Figure 8 shows an overview of the iPRECON and muciPRECON concepts.

Figure 8.

Overview on iPRECON technology: (a) direct valve connectors, (b) Luer-Lock connector, (c) preconcentrator, (d) three-way valve, (e) solenoid valves (V1–V4), (f) imperial to metric adapter, (g) M5 to Luer-Lock adapter, (h) tubing. Cross-sectional view of muciPRECON device: blue and yellow colors illustrate two different sorbent materials loaded into the channels with a third channel (not filled with the sorbent) at the front. Reproduced from Kokoric, V., Wilk, A., & Mizaikoff, B. iPRECON: An integrated preconcentrator for the enrichment of volatile organics in exhaled breath. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 3664–3667 with permission from Royal Society of Chemistry and from Kokoric, V., Wissel, P. A., Wilk, A., & Mizaikoff, B. muciPRECON: multichannel preconcentrators for portable mid-infrared hydrocarbon gas sensors. Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 6645–6650 with permission from Royal Society of Chemistry.

Similarly, the so-called iCONVERT49 was designed to perform a UV-induced conversion using four miniaturized UV lamps emitting at 185 nm with a similar footprint and modular concept as the iHWG and iPRECON. Luer-Lock connectors were used to redaily attach to other modules such as iPRECON or iHWG. This proposed hyphenated technology—iCONVERT-iPRECON-iHWG—was applied by Petruci et al. for an online monitoring of SO2 and H2S with detection limits in the parts per billion concentration range.

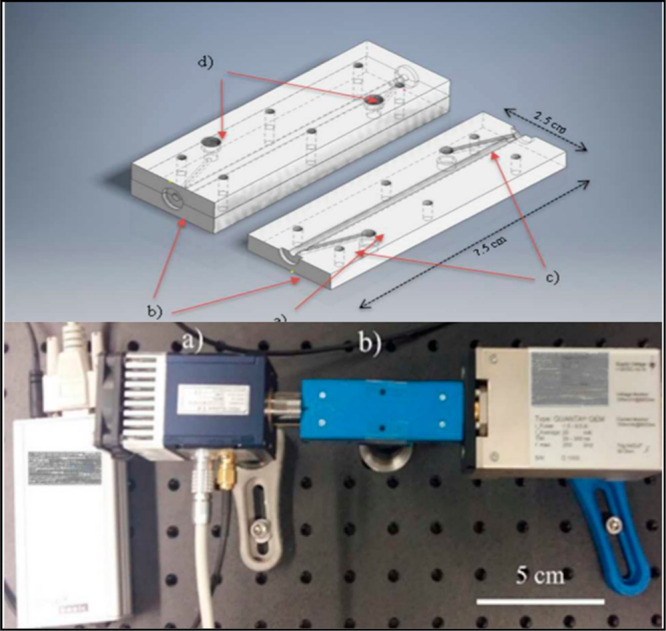

3.4. Fiberoptically Coupled iHWG Sensors for Remote Sensing

Since the first report, iHWG-based sensors were designed combining free-space optics with single-pass geometries, which require separate ports for the incoupling and outcoupling of MIR radiation. Parabolic gold-coated mirrors and optomechanics were used to guide the radiation to the iHWG input and at the distal end to the MCT detector. Such setups have been proven useful in a variety of scenarios; however, for applications in harsh or inaccessible environments where samples must be probed remotely and the detection must be performed in situ this approach is of limited utility. In this context, an innovative approach was first designed by Tütüncü et al.,50 whereby a double-pass iHWG-based sensor with a single integrated fiber bundle for signal coupling was developed (Figure 9). The direct fiber bundle coupling interface enables the integration of the iHWG “sensing head” with any MIR light source/detector combination, and MIR radiation is fibercoupled into the device with minimal optical losses. Moreover, the fiber bundle is replaceable and requires minimal optical alignment. Coiled and straight channel geometries were evaluated using the double-pass approach with mirrors at the end of each channel effectively doubling the OPL. This setup can be used in scenarios that require remote and in situ sensing yet avoid active light sources in the vicinity of the probed environment.

Figure 9.

Fully assembled double-pass iHWG with integrated fiber bundle. (a) Coiled (138 mm length) channel structure and (b) straight (58.5 mm length) channel structure with integrated reflecting mirror at one end of the iHWG optical channel. (c) Schematic diagram of the experimental setup: (1) FTIR spectrometer; (2) gold-coated planar mirror; (3, 6, 7) parabolic OAPMs; (4) 7-around-1 silver halide fiber bundle; (5) coiled iHWG; (8) MCT detector; (a) single IR delivery fiber, incoupling facet; (b) 7-around-1 fiber bundle (sensor interface); (c) 6-around-1 silver halide fiber bundle (IR collection fibers; outcoupling facet). Reproduced from Tütüncü, E.; et al. Fiber-Coupled Substrate-Integrated Hollow Waveguides: An Innovative Approach to Midinfrared Remote Gas Sensors. ACS Sensors 2017, 2, 1287–1293. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

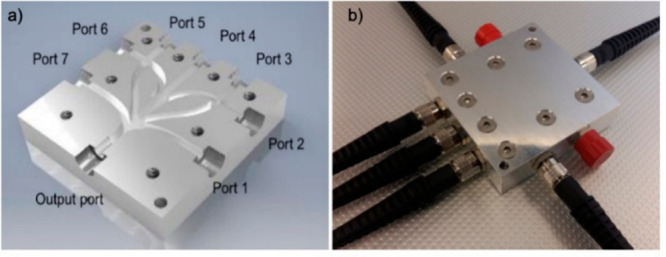

More recently,42 the fiber-coupling approach was employed in a similar design where a highly efficient multiport beam combiner aluminum-based iHWG was produced and coupled to radiation emitted from a set of individual QCLs operating in a continuous wave mode via AgX fibers and F-SMA connectors. This so-called iBEAM device (Figure 10) showed efficient fiber-coupling from the laser light sources and enabled the flexibility for adapting this concept to a wide variety of application scenarios. Fiber-to-hollow-core-channel coupling losses of 6.49 dB were derived. Propagation losses of 0.62 dB/cm at a wavelength of 5.8 μm and of 1.54 dB/cm at a wavelength of 10.6 μm confirmed adequate characteristics for a short-range propagation of MIR radiation as intended for integrated beam-combining purposes.

Figure 10.

(a) Internal channel layout and port assignment of a typical iBEAM beam combiner. (b) iBEAM fiber coupled with two blind/capped ports. Reprinted with permission from Haas, J.; et al. iBEAM: substrate-integrated hollow waveguides for efficient laser beam combining. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 23059. Copyright 2019 OSA Publishing.

3.5. Volatile Compound Analysis Via Integrated Microfluidics

Volatile substances can be detected by a determination of their physicochemical properties when equilibrating between liquid and vapor phases. However, direct and (near) real-time measurements of such scenarios remain an analytical challenge. Besides, according to Raoult’s law the concentration (or activity) can be derived from measurements of equilibrium partial pressures of each substance. To fabricate a tailored iHWG-based system to facilitate an analysis of volatile samples distributed between liquid and vapor phases, an innovative approach was designed to integrate a microfluidic cartridge and a liquid–vapor sampling cell based on iHWG technology for rapid equilibration in combination with an FTIR spectrometer light source.51 Basically, the liquid sample is injected into a microfluidic channel (bottom layer in Figure 11) separated from an iHWG channel above via a nanoporous membrane. All components in the condensed phase with non-negligible vapor pressure then evaporate via the membrane into an intermediate void layer (i.e., vapor diffusion cell) and subsequently diffuse through perforations into the light-guiding channel of the iHWG; top layer in Figure 11) sampled by IR radiation. The developed device for the first time provides a direct analysis of volatile compounds via evaporation from liquid using a combined iHWG-microfluidic device technology (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Schematic cross-section of the experimental setup (not to scale). Iin: intensity of the in-coupled radiation (emanating from the FTIR spectrometer). During the acquisition of a single-channel sample spectrum both solenoid valves are closed = equilibration phase. I: out-coupled radiation intensity; I < Iin due to the presence of absorbing molecules within the IR beam path within the iHWG. Reproduced from Kokoric, V.; et al. Determining the Partial Pressure of Volatile Components via Substrate-Integrated Hollow Waveguide Infrared Spectroscopy with Integrated Microfluidics. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 4445–4451. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society.

4. Applications

Since their introduction in 2013, the analytical utility of MIR-iHWG-based gas sensors was shown in a wide variety of application scenarios, which demand molecular selectivity, sensitivity, a compact device footprint, and measurements at or close to real-time. In addition, several studies demonstrated the potential of the modular concept of substrate-integrated hollow waveguides attached to different optoelectronic components and/or sample pretreatment/preconcentration strategies for clinical, environmental, industrial, and agricultural applications. Table 2 summarizes published studies using MIR-iHWG based sensors along with their main characteristics. Clinical and environmental/agricultural applications have tremendous potential for the iHWG technology platform, and they are therefore discussed in more detail herein.

Table 2. Selected Studies using MIR-iHWG-Based Sensors.

| instrumental setup | analyte | LOD | remarks | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR–MCT detector | ozone (O3) | 3.5 ppmv | gold-coated meandered iHWG | (55) |

| FTIR–MCT detector | hydrogen sulfide (H2S) | 3 ppmv | conversion of H2S to SO2 prior IR analysis | (46) |

| riQCL–MCT detector | furan (C4H4O) and 2-methoxyethanol (C3H8O2) | not specified | brass compact iHWG | (53) |

| FTIR–MCT detector | isoprene (C5H8) | 32.0 ppbv | a compact preconcentrator column was coupled to iHWG | (45) |

| FT-NIR | methane (CH4), ethane (C2H6), propane (C3H8) and butane (C4H10) | not specified | partial least-squares (PLS) regression | (56) |

| ICL-MCT detector | methane (CH4) | 6 ppmv | brass substrate gold-coated | (41) |

| FTIR–MCT detector | isobutylene (C4H8) and cyclopropane (C3H6) | 22 and 57 ppmv | fiber-iHWG | (50) |

| silver halide fibercoupled to the iHWG μFLUID-IR | ||||

| FTIR–MCT detector | EtOH (C2H5OH) | not specified | liquid phase sampling accessory for vapor phase studies | (51) |

| QCL-MCT detector | 12CO2 and 13CO2 | 45.0 ppmv and 8.0 ppmv | 3D printed polyHWGs coated with a gold layer | (44) |

| FTIR-MCT detector | nitrous oxide (N2O) | 5.0 ppbv | iHWG combined with a compact preconcentrator device | (57) |

| FTIR | carbon dioxide (CO2) | not specified | iHWG combined with a luminescence-based flowthrough oxygen sensor | (54) |

| FTIR-MCT detector | nitrogen monoxide (NO) | 1.5 ppbv | conversion of NO to NO2 using ultraviolet radiation | (39) |

| nitrogen dioxide (NO2) | 1.0 ppmv | |||

| nitrous oxide (N2O) | 0.5 ppbv | |||

| FTIR-DTGS detector | isobutane (C4H10) | 8.0 ppmv | simulation and optimization of iHWG structures. | (58) |

| MIR-MCT detector | methane (CH4) | 12.0 ppmv | multichannel preconcentrators | (48) |

| FTIR–MCT | carbon monoxide (CO) | 94 ppmv | dynamic catalyst performance studies | (59) |

| carbon dioxide (CO2) | 13 ppmv | |||

| FTIR–MCT | hydrogen sulfide (H2S) | 1.5 ppmv | UV-based conversion of H2S to SO2 (iCONVERT); preconcentrator unit (iPRECON) | (49) |

| FTIR-MCT Detector | hydrogen sulfide (H2S) | 0.207 ppmv | custom-made preconcentration tube (H2S to SO2) and an in-line UV-converter device | (43) |

| sulfur dioxide (SO2) | 0.077 ppmv | |||

| DFB-ICL-MCT | butane (C6H6) | 0.42 ppmv | combination of a distributed feedback laser (DFB) ICL with an iHWG | (52) |

4.1. Clinical Applications

An analysis of chemical compounds in exhaled breath (EB) is powerful strategy, which is of increasing importance in medical diagnostics for early disease detection and for monitoring therapy progress. Among the most relevant and prevalent components found in exhaled breath are volatile organic compounds (VOCs) serving as biomarkers at concentrations ranging from low parts per million to parts per trillion levels. For example, isoprene is a relevant biomarker found in EB as a byproduct of cholesterol synthesis and is therefore a useful biomarker for several metabolic disorders. Perez-Guaita et al.45 and Kokoric et al.47 have developed MIR sensors tailored for isoprene determination in exhaled breath based on the hyphenation of iHWG-based sensors with a preconcentration step using a polymeric adsorbent achieving detection limits of 106 and 260 ppbv, respectively.

Methane (CH4) is another frequently occurring hydrocarbon present in EB and can be used for a biomedical diagnosis at concentration levels of 3–8 ppmv. Therefore, the development of analytical platforms for an in situ and real-time monitoring of methane is essential. By taking advantage of its distinct molecular absorption at ∼3 μm, Tütüncü et al.41 and da Silva et al.52 have developed compact gas sensors that combine iHWGs with distributed feedback interband cascade lasers (DFB-ICLs) that emit single-mode radiation at 3.366 μm. In the first approach, gold-coated off-axis parabolic mirrors were used to guide light for in/outcoupling through a gold-coated brass 75 mm length iHWG, achieving an LOD of 38 ppm. Next, another device was developed with a direct coupling of a 250 mm aluminum straight iHWG with DBF-ICL light source and an MCT detector reaching an LOD of 7 ppmv.

Another relevant biomarker continuously monitored is carbon dioxide (CO2), which is among the most abundant molecules in exhaled breath. Its concentration determination provides important diagnostic insight into the metabolic status of a patient. Moreover, changes in the isotope ratio between 12CO2 and 13CO2 have been used for diagnoses of liver malfunction, bacterial overgrowth, fat absorption, and the diagnosis of Helicobacter pyroli infection. A noninvasive monitoring of glucose metabolism can be also performed by measurements of the 12CO2 and 13CO2 ratio. Breath analysis in animals either for veterinary diagnosis or research in preclinical animal models has grown the demand for analytical platforms handling exceedingly small sample volumes (e.g., as occurring in mouse breath analysis), near real-time response, and in situ analysis capability. In order to provide online measurements associated with the mentioned characteristics, gas sensors based on iHWGs and the distinct mid-infrared absorption signatures of 12CO2 and 13CO2 in the spectral window around 2294 cm–1 were developed. Tütüncü et al.53 have employed a gas sensor based on DFB-ICL emitting a single-mode IR radiation at 4.35 μm attached to a dual-channel 75 mm straight-line channel iHWG using a 50/50 beam splitter for reference measurements using two pyroelectric infrared detectors. In parallel, the oxygen concentration in exhaled breath was simultaneously monitored in a signal-synchronized fashion by ultrafast electrospun oxygen sensors based on a luminescence quenching of an immobilized dye. The sample volume was calculated as 315 μL, and the sensor was applied for an online monitoring of exhaled mouse breath performed in 14 mechanically ventilated and instrumented mice (Figure 12). Seichter et al.54 demonstrated the usage of a compact FTIR-iHWG-based gas sensor to monitor 12CO2/13CO2 and oxygen by a luminescence-based flow-through sensor integrated into the respiratory equipment of the mouse intensive care unit (MICU). These systems are nowadays in routine use in MICU stations and for the first time provide real-time information on the physiological condition of small animals via a noninvasive exhaled breath analysis.

Figure 12.

Mouse breath analysis system: PEEP (peep positive end expiratory pressure system); ICL (interband cascade laser); PD (pyroelectric detectors); dual-channel iHWG (measurement and reference); A/D (AD converter); DAQ (data acquisition system). Reprinted with permission from Seichter, F.; et al. Online Monitoring of Carbon Dioxide and Oxygen in Exhaled Mouse Breath via Substrate Integrated Hollow Waveguide–Fourier Transform Infrared–Luminescence Spectroscopy. J. Breath Res. 2018, 12, 036018. Copyright 2018 IOP Publishing.

4.2. Environmental and Agricultural Applications

The most relevant targets related to atmospheric pollution have a distinct absorption signature in the MIR range as shown in part in Figure 1. Among other monitoring and sensing concepts, many analytical platforms are based on using MIR and, more specifically, IR-iHWG approachs for probing molecular pollutants including O3, NOx, H2S, SO2, and CH4. Petruci et al.55 have developed a gas sensor for a direct ozone measurement using the absorption band at 1055 cm–1 with a “yin-yang” gold-coated iHWG optically attached to a benchtop FTIR spectrometer and a nitrogen-cooled MCT detector. A detection limit of 3.5 ppmv was achieved. A similar instrumental setup was used to monitor hydrogen sulfide after its light-induced conversion to SO2—which has a much pronounced absorption signature from 1395 to 1321 cm–1—with a detection limit of 3 ppmv.46 Additionally, this study was continued with the development of a more sensitive online gas sensor for H2S and SO2 monitoring via (i) a preconcentration (iPRECON) of H2S and SO2 analytes for 10 min using a Tenax GC followed by a thermal desorption and (ii) a light-induced conversion (iCONVERT) of H2S to SO2. Detection limits of 207 and 77 ppbv were achieved for H2S and SO2, respectively.43 Instrumental assembling involved a compact “shoe-box”-sized FTIR spectrometer coupled to a 150 mm straight iHWG and MCT detector.

Nitrogen oxides play an important role in the environment, indicating potential pollution sources related to an excessive burning of fossil fuels (e.g., diesel vehicle exhaust, etc.) as high levels of NO2 and NO are produced. Moreover, the application of nitrogen-based fertilizers can induce the release of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide (N2O) from microorganism activities in soil. A hyphenated preconcentrator-IR-iHWG sensor system was developed for N2O sensing using the strong absorption band with boundaries from 2222 to 2177 cm–1. By taking advantage of a adsorption/thermal desorption step and a 150 mm straight-line aluminum iHWG, a remarkable detection limit of 5 ppb was achieved, which enabled real-world sample monitoring as the background levels of atmospheric N2O is ∼330 ppbv.57 Besides, Petruci et al.39 proposed an innovative mid-infrared chemical sensor platform for the in situ, real-time, and simultaneous quantification of all relevant nitrogen-based gases (i.e., NO, NO2, and N2O) by combining a compact FTIR spectrometer with 150 mm straight iHWG as a miniaturized gas cell. The optical platform enabled limits of detection of 10, 1, and 0.5 ppmv of NO, NO2, and N2O, respectively. The linear concentration range evaluated in this study is suitable for the application of the sensing platform in vehicle exhaust air samples.

4.3. Other Applications

The ability to monitor dynamic changes in the gas mixtures due the rapid transient times is an important feature of the developed iHWG-based sensors. Particularly, modern catalysis research involves the kinetic and mechanistic studies on heterogeneously catalyzed gas-phase reactions, which demands a rapid analysis in order to dynamically detect changes in a gas-phase composition. Therefore, the FTIR-iHWG-based gas sensors also appear as an excellent alternative for such scenarios, and a novel concept for analyzing the performance of catalysts was proposed by Kokoric et al.59 In this approach, a 75 mm straight iHWG coupled to a compact FTIR spectrometer was employed to monitor compositional changes of a continuous gas stream after an interaction with a catalyst assembly. Carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO2) were the monitored gases in this study.

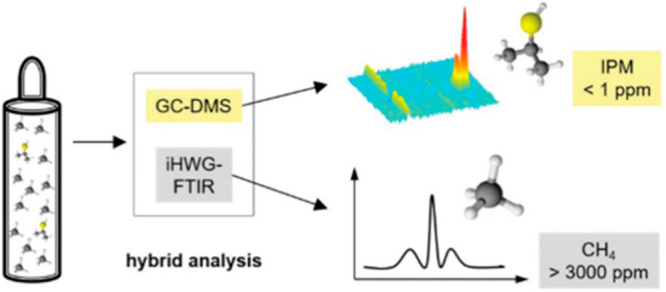

The development of portable analytical platforms for a multianalyte determination within complex sample mixtures in a different concentration range remains undoubtedly a challenging task in a wide variety of scenarios. An interesting alternative to meet this challenge is the design of hybrid analytical platforms that combine two or more analytical techniques, which provides complementary analyte information such as type and concentration. In this context, a cost-efficient and portable platform was proposed by Hagemann et al.60 that combined for the first time FTIR spectroscopy with gas chromatography coupled to differential ion mobility spectrometry (GC-DMS) providing a promising analytical system for the investigation of complex samples containing a variety of differently concentrated analytes. A 75 mm straight aluminum iHWG was optically coupled to a shoe-box-sized FTIR spectrometer using gold-coated off-axis parabolic mirrors. The sample was guided first to the FTIR-iHWG system followed by an injection into the GC-DMS. As a model analyte, 5 ppmv of isopropylmercaptan (IPM) was diluted in methane (CH4). Figure 13 shows the concept of the hyphenated device.

Figure 13.

A gaseous sample mixture of a low-concentration isopropylmercaptan (ppb range) and a highly concentrated methane (% range) was analyzed via the hybrid analytical setup that interfaced GC-DMS and iHWG-FTIR taking advantage of the orthogonality of the two methods. Reproduced from Hagemann, L. T.; et al. Portable combination of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and differential mobility spectrometry for advanced vapor phase analysis. Analyst 2018, 143, 5683–5691 with permission from Royal Society of Chemistry.

More recently, another hybrid analytical device was developed combining eNose technology based on semiconducting metal oxide (MOX) sensors with FTIR-iHWG gas sensors to enhance the data space enabling the analysis of complex sample mixtures (e.g., exhaled breath).61 A 75 mm straight iHWG was coupled to a compact FTIR spectrometer, and samples were first injected into the FTIR-iHWG system followed by a flow-through analysis within an MOX gas sensor array. The device was evaluated for the simultaneous detection of methane and carbon dioxide at low parts per million concentrations.

5. Outlook and Perspectives

Chemical sensors based on the absorption of radiation in the mid-infrared spectral regime are an excellent choice for monitoring relevant gaseous compounds with an inherent molecular selectivity and remarkable sensitivity. Despite significant advances toward miniaturized MIR light sources and detectors in the recent decades, much less attention was paid to the development of compact gas cells as a viable alternative for conventional multipass gas cells or conventional dielectric hollow waveguides.

Almost a decade ago, a simple yet innovative modular approach that provides a new generation of miniaturized gas cell, aka substrate-integrated hollow waveguides, pioneered by the research team of Mizaikoff and collaborators were introduced as efficient photon-propagating conduits that simultaneously serve as highly miniaturized gas cells. iHWGs are characterized by rapid sample transient times, low required sample volumes, robustness, ease of optical alignment, and mechanical robustness next to low cost in material and fabrication. Furthermore, the compactness and modularity of iHWGs facilitate their integration into miniaturized sensing systems along with essentially any light source, detector, sample preconcentration/pretreatment strategy, and orthogonal analytical technique(s). The application of iHWGs in mid-infrared-based sensor systems has been particularly successful and has, thus, been the focus of the present review.

Despite the versatility and flexibility of iHWG-based sensing systems, there are a few drawbacks that remain a challenge. The achievable optical path length remains limited not only for device footprint/size/weight considerations but also for attenuation losses when reflection losses increase by meandering. Hence, the gain in an extended absorption path length is counterbalanced by the associated optical losses when the physical photon propagation path is elongated. This in turn limits the achievable sensitivity to the parts per million–parts per billion concentration range depending on the absorption cross-section of the individual species. Hence, preconcentration and conversion strategies have to be integrated to lower the limits of detection, if required by the respective application, yet, under consideration that the temporal resolution of the analytical signal will be compromised.

Despite the number of real-world applications shown to date, iHWG sensor systems still face challenges with increasingly complex sample mixtures. However, this problem persists for almost any kind of chemical sensing technology when translated from a laboratory technique into an in-field device. A possible and indeed viable solution is the smart hyphenation with additional—ideally orthogonal—analytical techniques that provide hybrid analytical platforms to address increasingly complex samples.

In conclusion, almost a decade after their introduction, iHWG-based sensors have left a distinct “footprint” in the optical gas-sensing community, and it appears they not only are here to stay but are expanding into additional spectral regimes such as the NIR/vis/UV on the short wavelength end and the THz at the long wavelength end of the electromagnetic spectrum. Given ongoing efforts in device miniaturization involving all essential components of optical chemical sensor systems, a wide variety of future application scenarios may be envisaged that capitalize on the discussed technologies including but not limited to drone-mounted ultralightweight devices for environmental and agricultural monitoring or disposable low-cost sensor interfaces in medical/clinical applications, for example, exhaled breath analysis in less-favored regions.

Acknowledgments

D.N.B. and J.F.S.P. are thankful to the Brazilian agencies Coordination of the Improvement of Higher Education (CAPES) and Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq)—Proc. 428094/2018-0—for scholarships and financial support. B.M. and V.K. thank the Ministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Kunst (MKW) Baden-Württemberg, Germany, under the Program “Special Measures against the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic” and the European Union Horizon 2020 Programme within the Project VOGAS (Grant No. 82498) for partial support.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ICL

interband cascade laser

- QCL

quantum cascade laser

- iHWG

substrate-integrated hollow waveguide

- HWG

hollow waveguide

- OPL

optical pathlenght

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared

- MCT

mercury-cadmium-tellurite detector

- DFB

distributed feedback laser

- DAS

direct absorption spectroscopy

- SCMS

supported capillary membrane sampler

- SPME

solid phase microextraction

- MIR

mid-infrared

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Coordination of the Improvement of Higher Education 001 and Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development—Proc. 428094/2018-0.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Mizaikoff B. Waveguide-enhanced mid-infrared chem/bio sensors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 8683–8699. 10.1039/c3cs60173k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman L. S.; et al. The HITRAN 2008 molecular spectroscopic database. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 2009, 110, 533–572. 10.1016/j.jqsrt.2009.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson J.; Tatam R. P. Optical gas sensing: a review. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2013, 24, 012004. 10.1088/0957-0233/24/1/012004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orphal J. A critical review of the absorption cross-sections of O3and NO2in the ultraviolet and visible. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2003, 157, 185–209. 10.1016/S1010-6030(03)00061-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Sahay P. Breath analysis using laser spectroscopic techniques: Breath biomarkers, spectral fingerprints, and detection limits. Sensors 2009, 9, 8230–8262. 10.3390/s91008230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Yu B.; Zhao W.; Chen W. A review of signal enhancement and noise reduction techniques for tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2014, 49, 666–691. 10.1080/05704928.2014.903376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Popa D.; Udrea F. Towards integrated mid-infrared gas sensors. Sensors 2019, 19, 1–15. 10.3390/s19092076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S.; Newport D.; Le Calve S. Gas Detection Using Portable Deep-UV Absorption. Sensors 2019, 19 (23), 5210. 10.3390/s19235210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risby T. H.; Tittel F. K. Current status of midinfrared quantum and interband cascade lasers for clinical breath analysis. Opt. Eng. 2010, 49, 111123. 10.1117/1.3498768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haseth J. A. De; Griffiths P. R.. Attenuated Total Reflection. In Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrom ,2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007; pp 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mikołajczyk J.; Bielecki Z.; Wojtas J.; Chojnowski S. Cavity Enhanced Absorption Spectroscopy in Air Pollution Monitoring. Sensors, Transducers 2015, 193, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Manfred K. M.; Hunter K. M.; Ciaffoni L.; Ritchie G. A. D. ICL-Based OF-CEAS: A Sensitive Tool for Analytical Chemistry. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 902–909. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaighofer A.; Brandstetter M.; Lendl B. Quantum cascade lasers (QCLs) in biomedical spectroscopy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 5903–5924. 10.1039/C7CS00403F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. S.; Chen W.; Fischer H. Quantum cascade laser spectrometry techniques: A new trend in atmospheric chemistry. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2013, 48, 523–559. 10.1080/05704928.2012.757232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J.; Zhu F.; Zhang S.; Kolomenskii A.; Schuessler H. A ppb level sensitive sensor for atmospheric methane detection. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2017, 86, 194–201. 10.1016/j.infrared.2017.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cossel K. C.; et al. Analysis of trace impurities in semiconductor gas via cavity-enhanced direct frequency comb spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. B: Lasers Opt. 2010, 100, 917–924. 10.1007/s00340-010-4132-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romanini D.; et al. Optical-feedback cavity-enhanced absorption: A compact spectrometer for real-time measurement of atmospheric methane. Appl. Phys. B: Lasers Opt. 2006, 83, 659–667. 10.1007/s00340-006-2177-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gurlit W.; et al. Lightweight diode laser spectrometer CHILD (compact high-altitude In-situ laser diode) for balloonborne measurements of water vapor and methane. Appl. Opt. 2005, 44, 91–102. 10.1364/AO.44.000091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanf S.; Bögözi T.; Keiner R.; Frosch T.; Popp J. Fast and highly sensitive fiber-enhanced Raman spectroscopic monitoring of molecular H2 and CH4 for point-of-care diagnosis of malabsorption disorders in exhaled human breath. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 982–988. 10.1021/ac503450y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B. T.; Inberg a; Croitoru N.; Mizaikoff B. Characterization of a mid-infrared hollow waveguide gas cell for the analysis of carbon monoxide and nitric oxide. Appl. Spectrosc. 2006, 60, 266–71. 10.1366/000370206776342661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmire E.; McMahon T.; Bass M. Propagation of ir light in flexible hollow waveguides: erratum. Appl. Opt. 1976, 15, 20281. 10.1364/AO.15.2028_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagi M.; Hongo A.; Aizawa Y.; Kawakami S. Fabrication of germanium-coated nickel hollow waveguides for infrared transmission. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1983, 43, 430–432. 10.1063/1.94377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saggese S. J.; Harrington J. A.; Sigel G. H. Attenuation of incoherent infrared radiation in hollow sapphire and silica waveguides. Opt. Lett. 1991, 16, 27. 10.1364/OL.16.000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z.; Zhang S.; Li J.; Gao N.; Tong K. Mid-infrared tunable laser-based broadband fingerprint absorption spectroscopy for trace gas sensing: A review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1–33. 10.3390/app9020338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk A.; Kim S.-S.; Mizaikoff B. An approach to the spectral simulation of infrared hollow waveguide gas sensors. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 395, 1661–71. 10.1007/s00216-009-3104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.-S.; et al. Mid-infrared trace gas analysis with single-pass fourier transform infrared hollow waveguide gas sensors. Appl. Spectrosc. 2009, 63, 331–7. 10.1366/000370209787598924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk A.; et al. Substrate-integrated hollow waveguides: a new level of integration in mid-infrared gas sensing. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 11205–10. 10.1021/ac402391m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoric V.; Widmann D.; Wittmann M.; Behm R. J.; Mizaikoff B. Infrared spectroscopy: Via substrate-integrated hollow waveguides: A powerful tool in catalysis research. Analyst 2016, 141, 5990–5995. 10.1039/C6AN01534D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; et al. Quantitative analysis of ammonia adsorption in Ag/AgI-coated hollow waveguide by mid-infrared laser absorption spectroscopy. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2019, 121, 80–86. 10.1016/j.optlaseng.2019.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Tsui C. P. Detection of chlorinated aromatic amines in aqueous solutions based on an infrared hollow waveguide sampler. Anal. Chim. Acta 2001, 442, 267–275. 10.1016/S0003-2670(01)01173-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Melas F.; Pustogov V. V.; Croitoru N.; Mizaikoff B. Development and Optimization of a Mid-Infrared Hollow Waveguide Gas Sensor Combined with a Supported Capillary Membrane Sampler. Appl. Spectrosc. 2003, 57, 600–606. 10.1366/000370203322005265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Melas F.; et al. Combination of a mid-infrared hollow waveguide gas sensor with a supported capillary membrane sampler for the detection of organic compounds in water. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2003, 83, 573–583. 10.1080/0306731021000003473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pogodina O. a; et al. Combination of sorption tube sampling and thermal desorption with hollow waveguide FT-IR spectroscopy for atmospheric trace gas analysis: determination of atmospheric ethene at the lower ppb level. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 464–8. 10.1021/ac034396j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey C. M.; Luxenburger F.; Droege S.; Mackoviak V.; Mizaikoff B. Near-infrared hollow waveguide gas sensors. Appl. Spectrosc. 2011, 65, 1269–74. 10.1366/11-06286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young C. R.; et al. Infrared hollow waveguide sensors for simultaneous gas phase detection of benzene, toluene, and xylenes in field environments. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 6141–7. 10.1021/ac1031034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Guaita D.; et al. Improving the performance of hollow waveguide-based infrared gas sensors via tailored chemometrics. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 8223–8232. 10.1007/s00216-013-7230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortes P. R.; et al. Optimized design of substrate-integrated hollow waveguides for mid-infrared gas analyzers. J. Opt. 2014, 16, 094006. 10.1088/2040-8978/16/9/094006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ribessi R. L.; et al. iHEART: a miniaturized near-infrared in-line gas sensor using heart-shaped substrate-integrated hollow waveguides. Analyst 2016, 141, 5298–5303. 10.1039/C6AN01027J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruci J. F. da S.; Tütüncü E.; Cardoso A. A.; Mizaikoff B. Real-Time and Simultaneous Monitoring of NO, NO2, and N2O Using Substrate-Integrated Hollow Waveguides Coupled to a Compact Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectrometer. Appl. Spectrosc. 2019, 73, 98–103. 10.1177/0003702818801371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruci J. F. D. S.; Cardoso A. A.; Wilk A.; Kokoric V.; Mizaikoff B. ICONVERT: An Integrated Device for the UV-Assisted Determination of H2S via Mid-Infrared Gas Sensors. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 9580–9583. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tütüncü E.; Nägele M.; Fuchs P.; Fischer M.; Mizaikoff B. iHWG-ICL: Methane Sensing with Substrate-Integrated Hollow Waveguides Directly Coupled to Interband Cascade Lasers. ACS Sensors 2016, 1, 847. 10.1021/acssensors.6b00238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas J.; et al. iBEAM: substrate-integrated hollow waveguides for efficient laser beam combining. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 23059. 10.1364/OE.27.023059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruci J. F. D. S.; Wilk A.; Cardoso A. A.; Mizaikoff B. Online Analysis of H2S and SO2 via Advanced Mid-Infrared Gas Sensors. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 9605. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stach R.; et al. PolyHWG: 3D Printed Substrate-Integrated Hollow Waveguides for Mid-Infrared Gas Sensing. ACS Sensors 2017, 2, 1700–1705. 10.1021/acssensors.7b00649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Guaita D.; Kokoric V.; Wilk A.; Garrigues S.; Mizaikoff B. Towards the determination of isoprene in human breath using substrate-integrated hollow waveguide mid-infrared sensors. J. Breath Res. 2014, 8, 026003. 10.1088/1752-7155/8/2/026003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavio da Silveira Petruci J.; Fortes P. R.; Kokoric V.; Wilk A.; Raimundo I. M.; Cardoso A. A.; Mizaikoff B.; et al. Monitoring of hydrogen sulfide via substrate-integrated hollow waveguide mid-infrared sensors in real-time. Analyst 2014, 139, 198–203. 10.1039/C3AN01793A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoric V.; Wilk A.; Mizaikoff B. iPRECON: An integrated preconcentrator for the enrichment of volatile organics in exhaled breath. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 3664–3667. 10.1039/C5AY00399G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoric V.; Wissel P. A.; Wilk A.; Mizaikoff B. muciPRECON: multichannel preconcentrators for portable mid-infrared hydrocarbon gas sensors. Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 6645–6650. 10.1039/C6AY01447J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petruci J. F. D. S.; Cardoso A. A.; Wilk A.; Kokoric V.; Mizaikoff B. ICONVERT: An Integrated Device for the UV-Assisted Determination of H2S via Mid-Infrared Gas Sensors. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 9580–9583. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tütüncü E.; et al. Fiber-Coupled Substrate-Integrated Hollow Waveguides: An Innovative Approach to Mid-infrared Remote Gas Sensors. ACS Sensors 2017, 2, 1287–1293. 10.1021/acssensors.7b00253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoric V.; et al. Determining the Partial Pressure of Volatile Components via Substrate-Integrated Hollow Waveguide Infrared Spectroscopy with Integrated Microfluidics. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 4445–4451. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b04425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JoséGomes da Silva I.; et al. Sensing hydrocarbons with interband cascade lasers and substrate-integrated hollow waveguides. Analyst 2016, 141, 4432–4437. 10.1039/C6AN00679E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tütüncü E.; et al. Advanced gas sensors based on substrate-integrated hollow waveguides and dual-color ring quantum cascade lasers. Analyst 2016, 141, 6202–6207. 10.1039/C6AN01130F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seichter F.; et al. Online Monitoring of Carbon Dioxide and Oxygen in Exhaled Mouse Breath via Substrate Integrated Hollow Waveguide - Fourier Transform Infrared - Luminescence Spectroscopy. J. Breath Res. 2018, 12, 036018. 10.1088/1752-7163/aabf98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silveira Petruci J. F.; Fortes P. R.; Kokoric V.; Wilk A.; Raimundo I. M.; Cardoso A. A.; Mizaikoff B.; et al. Real-time monitoring of ozone in air using substrate-integrated hollow waveguide mid-infared sensors. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1–5. 10.1038/srep03174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohwedder J. J. R.; et al. iHWG-μNIR: A miniaturised near-infrared gas sensor based on substrate-integrated hollow waveguides coupled to a micro-NIR-spectrophotometer. Analyst 2014, 139, 3572–3576. 10.1039/c4an00556b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silveira Petruci J. F.; Wilk A.; Cardoso A. A.; Mizaikoff B. A hyphenated preconcentrator-infrared-hollow-waveguide sensor system for N2O sensing. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–12. 10.1038/s41598-018-23961-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann L. T.; Ehrle S.; Mizaikoff B. Optimizing the Analytical Performance of Substrate-Integrated Hollow Waveguides: Experiment and Simulation. Appl. Spectrosc. 2019, 73, 1451–1460. 10.1177/0003702819867342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoric V.; Widmann D.; Wittmann M.; Behm R. J.; Mizaikoff B. Infrared spectroscopy via substrate-integrated hollow waveguides: a powerful tool in catalysis research. Analyst 2016, 141, 5990–5995. 10.1039/C6AN01534D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann L. T.; et al. Portable combination of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and differential mobility spectrometry for advanced vapor phase analysis. Analyst 2018, 143, 5683–5691. 10.1039/C8AN01192C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glöckler J. iHWG-MOX: A Hybrid Breath Analysis System via the Combination of Substrate-Integrated Hollow Waveguide Infrared Spectroscopy with Metal Oxide Gas Sensors. ACS Sensors 2020, 5, 1033. 10.1021/acssensors.9b02554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]