Abstract

Tooth discoloration is considered as one of the most common dental problems among people, and in dentistry, the most common cases are claimed after the restoration. Therefore, in this research, we aim to evaluate the effect of carbonated beverages on the color stability of bulk and flowable composite resin. For the study, 12 composite disc samples were made using the standard dimensions of 10 mm diameter and 2 mm thick. To find the color stability, we used a VITA Easyshade spectrophotometer. We used two different composites of bulk fill and flowable composite resin; the composite brand we used was Tetric ecom plus; as an immersion medium, we used two different carbonated beverages, and the chosen beverages were Appy Fizz and 7Up. 24-h and 7-day postimmersion color stability was evaluated. In the results of postimmersion, we have found the Delta E value for 24 h immersion of flowable and bulk fill composite as 5.8115 and 7.4378, respectively; similarly, the Delta E value for 7 days immersion of flowable and bulk fill composite was 9.9559 and 10.1028, respectively. Using the independent “t”-test, we found that the significance is 0.633 and 0.328, which was statistically not significant. In the present study, when immersed in Appy Fizz juice and 7Up juice, bulk fill composite resins have shown greater discoloration when compared to flowable composite resin material. Thus, the flowable composite resin samples were more color stable.

Keywords: Bulk fill composite, carbonated drinks, color stability, flowable composite, innovative measurement, spectrophotometer

INTRODUCTION

Composite resins are made using bisphenol A-glycidyl methacrylate, dimethacrylate monomers, a filler substance like silica, and a photoinitiator. Dimethylglyoxime is used to provide specific physical qualities, such as flowability.[1,2] The resin wears well without a filler, has a lot of shrinkage, and is exothermic.[3] Exclusive resin blends compose the matrix of composites, much as tailored filler glasses and glass sintered production. Reduced polymerization shrinkage, enhanced compressive strength, and increased translucency are all benefits of the filler material.[4]

Light-cured resin composites, known as bulk fill resin composites, can be placed in layers or increments of 4–5 mm in depth.[5] The most notable advantage of these materials is initially the decrease in time needed for material insertion and polymerization, as well as the reduction in procedure sensitivity.[6] Light polymerization necessitates careful attention. Bulk cure is not usually synonymous with bulk fill.[7] Make sure the light tip is completely covering the material. Multiple exposures may be required to polymerize all of the composite resin materials.

The modification of color is largely linked to an individual's dental hygiene and eating habits, and it is a key quality that evaluates the success or failure of restorative treatment.[8] Carbonated beverages, sometimes known as bubbly drinks, are carbonated fluids that contain dissolved carbon dioxide (CO2).[9] Fizz or efflorescence is caused by CO2 dissolving in a liquid. CO2 is commonly used in the procedure, which is done at a high pressure.[10] Our team has a wealth of expertise and research experience, which has produced articles of the highest caliber.[11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] Therefore, in this research, we aim to evaluate the effect of carbonated beverages on the color stability of bulk and flowable composite resin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

For the study, 12 disc samples were made using the standard dimensions of 10 mm diameter and 2 mm thick. All of the disc specimens were polymerized using light-emitting diode light-curing equipment with a 1000 mW/cm2 light intensity and three 20-s exposure to the top. A 5 mm spacing was established between the light cure tip and the composite disc. We used two separate bulk fill and flowable composite resin composites; the brand name of the composite was Tetric ecom plus. With a low-speed handpiece, the surfaces were polished with Shofu brand composite polishing kit. As an immersion medium, we used two different carbonated beverages, and the chosen beverages were Appy Fizz and 7Up. These drinks were made in India. The color stability was measured using a spectrophotometer [Figure 1]. It was done for three times, namely before immersion, 24 h after immersion, and 7 days postimmersion. Before evaluating the color stability, the discs were rinsed in distilled water. L, A, and B value data were obtained from the spectrophotometer. Finally, Delta E values were calculated using the conventional formula.

Figure 1.

Vita Easyshade Spectrophotometer

RESULTS

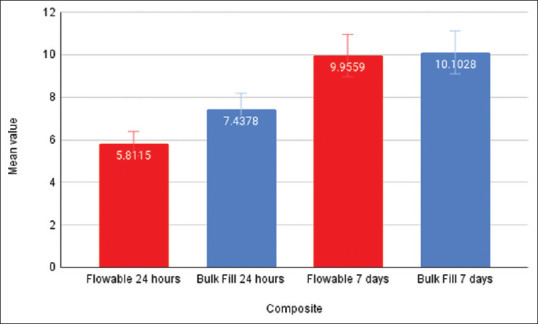

We have estimated the mean value for Delta E in postimmersion for 24 h and 7 days for both flowable and bulk fill composite resin. Table 1 shows the mean, standard deviation, and test significance for 24 h of postimmersion, and Table 2 shows the mean, standard deviation, and significance of postimmersion 7 days. The 24-h immersion mean was found to be 5.8115 ± 1.4560 in the flowable-type group. The 24-h immersion mean was found to be 7.4378 ± 2.36388 in the bulk fill group. The 7-day immersion mean was found to be 9.9559 ± 6.56956 in the flowable-type group. The 7-day immersion mean was found to be 10.1028 ± 5.72514 in the bulk fill group. [Figure 2] indicates the error bars for the mean values of comparing both 24 h and 7 days of postimmersion for flowable and bulk fill composite. Therefore, we have calculated the independent ’t’-test using the Spss version 22.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) and found that the significance P = 0.633 and 0.328, which was statistically not significant.

Table 1.

24-h immersion of both flowable and bulk fill composite

| Group | Mean | SD | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flowable | 5.8115 | 1.45603 | 0.633 |

| Bulk fill | 7.4378 | 2.36388 | 0.633 |

SD: Standard deviation

Table 2.

7-day immersion values of both flowable and bulk fill composite

| Group | Mean | SD | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flowable | 9.9559 | 6.56956 | 0.328 |

| Bulk fill | 10.1028 | 5.72514 | 0.328 |

SD: Standard deviation

Figure 2.

The mean of flowable and bulk fill composite for 24 h and 7 days, identified via independent “t”-test. X-axis is type of composite with the duration of immersion, Y-axis is the mean value. Red color indicates the flowable composite of both 24 h and 7 days postimmersion. Blue color indicates the bulk fill composite of both 24 h and 7 days postimmersion. The mean values of flowable composite for 24 h and 7 days are 5.8115 and 9.9559, respectively. Similarly, the mean values of bulk fill for 24 h and 7 days were 7.4378 and 10.1028, respectively. There was a significance of 0.633 for 24 h and 0.328 for 7 days postimmersion

DISCUSSION

The most significant and prevalent dental procedure in advanced dentistry is composite restoration. It is the most popular and appropriate treatment option, widely endorsed and recognized by both dental professionals and patients around the world. The focus of this research is on two types of composite restorative materials that are often utilized in dentistry.[26,27] The materials are all from the same manufacturer, and they come in two types: bulk fill and regular flowable composite. The Delta E value was determined to compare the color stability of composite materials. The selected carbonated beverages showed the most severe color changes, but the bulk fill resin had an increased color change than the flowable composite. Discoloration of tooth-colored normal and bulk fill resin composite materials can be a main cause of dental restoration replacement in cosmetic areas. This complication affects both patients and dentists.

A range of cosmetic restorative materials have already been examined in vitro for color stability. When compared to standard flowable fill composite, bulk fill resins show more discoloration, indicating that they are less color stable. Carbonated beverages have been shown in several tests to aid staining by weakening the resin matrix of composites. Furthermore, there are studies showing that carbonated beverages cause surface roughness on composite filled teeth.[28]

There are also studies indicating the similar Chi-square value where P = 0.239, which is statistically not significant. Another article declares that there is a significant color difference in bulk fill and flowable composites resin when immersed in the carbonated beverages; they estimated that the Delta E value was >3.5 times which is considered a significant color change in the composite materials. These levels were considered to be clinically unacceptable and visually visible.[29]

In this study, we have only considered a similar brand of two different composites which the results conclude only using those particular brand composites. Therefore, in further research, the need is to experiment the color stability of different composite materials for better restoration purposes. This study can help dental practitioners to use the adequate composite material for the restoration procedure, which can satisfy several criteria among the patients and dental practitioners.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, when immersed in Appy Fizz juice and 7Up juice, bulk fill composite resins have shown greater discoloration when compared to flowable composite resin material. Thus, the flowable composite resin samples were more color stable.

Financial support and sponsorship

The present study was supported by the following: Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai, and Azul Clothing Company.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The team extends our sincere gratitude to the Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals for their constant support and successful completion of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singhal P, Dhingra A, Bhandari M. Spectrophotometer analysis of bulk-fill composites on various beverages: An in-vitro study. IP Indian J Conserv Endod. 2019;4:20–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darabi F, Seyed-Monir A, Mihandoust S, Maleki D. The effect of preheating of composite resin on its color stability after immersion in tea and coffee solutions: An in-vitro study. J Clin Exp Dent. 2019;11:e1151–6. doi: 10.4317/jced.56438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyas MJ. Colour stability of composite resins: A clinical comparison. Aust Dent J. 1992;37:88–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1992.tb03042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim RJ, Kim YJ, Choi NS, Lee IB. Polymerization shrinkage, modulus, and shrinkage stress related to tooth-restoration interfacial debonding in bulk-fill composites. J Dent. 2015;43:430–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tekçe N, Tuncer S, Demirci M, Serim ME, Baydemir C. The effect of different drinks on the color stability of different restorative materials after one month. Restor Dent Endod. 2015;40:255–61. doi: 10.5395/rde.2015.40.4.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lepri CP, Palma-Dibb RG. Surface roughness and color change of a composite: Influence of beverages and brushing. Dent Mater J. 2012;31:689–96. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2012-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cebe MA, Cebe F, Cengiz MF, Cetin AR, Arpag OF, Ozturk B. Elution of monomer from different bulk fill dental composite resins. Dent Mater. 2015;31:e141–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shamszadeh S, Sheikh-Al-Eslamian SM, Hasani E, Abrandabadi AN, Panahandeh N. Color stability of the bulk-fill composite resins with different thickness in response to coffee/water immersion. Int J Dent 2016. 2016:7186140. doi: 10.1155/2016/7186140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbosa GF, Cardoso MB. Effects of carbonated beverages on resin composite stability. Am J Dent. 2018;31:313–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borges MG, Soares CJ, Maia TS, Bicalho AA, Barbosa TP, Costa HL, et al. Effect of acidic drinks on shade matching, surface topography, and mechanical properties of conventional and bulk-fill composite resins. J Prosthet Dent. 2019;121:868.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2019.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishnamurthy A, Sherlin HJ, Ramalingam K, Natesan A, Premkumar P, Ramani P, et al. Glandular odontogenic cyst: Report of two cases and review of literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3:153–8. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0117-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dua K, Wadhwa R, Singhvi G, Rapalli V, Shukla SD, Shastri MD, et al. The potential of siRNA based drug delivery in respiratory disorders: Recent advances and progress. Drug Dev Res. 2019;80:714–30. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdul Wahab PU Senthil, Nathan P, Madhulaxmi M, Muthusekhar MR, Loong SC, Abhinav RP. Risk factors for post-operative infection following single piece osteotomy. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2017;16:328–32. doi: 10.1007/s12663-016-0983-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thanikodi S, Kumar SD, Devarajan C, Venkatraman V, Rathinavelu V. Teaching learning optimization and neural network for the effective prediction of heat transfer rates in tube heat exchangers. Therm Sci. 2020;24:575–81. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Subramaniam N, Muthukrishnan A. Oral mucositis and microbial colonization in oral cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy and chemotherapy: A prospective analysis in a tertiary care dental hospital. J Investig Clin Dent. 2019;10:e12454. doi: 10.1111/jicd.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar SP, Girija AS, Priyadharsini JV. Targeting NM23-H1-mediated inhibition of tumour metastasis in viral hepatitis with bioactive compounds from Ganoderma lucidum: A computational study. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2020;82:300–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manickam A, Devarasan E, Manogaran G, Priyan MK, Varatharajan R, Hsu CH, et al. Score level based latent fingerprint enhancement and matching using SIFT feature. Multimed Tools Appl. 2019;78:3065–85. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravindiran M, Praveenkumar C. Status review and the future prospects of CZTS based solar cell –A novel approach on the device structure and material modeling for CZTS based photovoltaic device. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2018;94:317–29. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vadivel JK, Govindarajan M, Somasundaram E, Muthukrishnan A. Mast cell expression in oral lichen planus: A systematic review. J Investig Clin Dent. 2019;10:e12457. doi: 10.1111/jicd.12457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma Y, Karunakaran T, Veeraraghavan VP, Mohan SK, Li S. Sesame inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis through inhibition of STAT-3 translocation in thyroid cancer cell lines (FTC-133) Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2019;24:646–52. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathivadani V, Smiline AS, Priyadharsini JV. Targeting Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA-1) with Murraya koengii bio-compounds: An in-silico approach. Acta Virol. 2020;64:93–9. doi: 10.4149/av_2020_111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Happy A, Soumya M, Venkat Kumar S, Rajeshkumar S, Sheba RD, Lakshmi T, et al. Phyto-assisted synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Cassia alata and its antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2019;17:208–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prathibha KM, Johnson P, Ganesh M, Subhashini AS. Evaluation of salivary profile among adult type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in South India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1592–5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5749.3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paramasivam A, Vijayashree Priyadharsini J. Novel insights into m6A modification in circular RNA and implications for immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:668–9. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0387-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ponnanikajamideen M, Rajeshkumar S, Vanaja M, Annadurai G. In vivo type 2 diabetes and wound-healing effects of antioxidant gold nanoparticles synthesized using the insulin plant Chamaecostus cuspidatus in albino rats. Can J Diabetes. 2019;43:82–9.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mundim FM, Garcia Lda F, Pires-de-Souza Fde C. Effect of staining solutions and repolishing on color stability of direct composites. J Appl Oral Sci. 2010;18:249–54. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572010000300009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miletic V, Marjanovic J, Veljovic DN, Stasic JN, Petrovic V. Color stability of bulk-fill and universal composite restorations with dissimilar dentin replacement materials. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2019;31:520–8. doi: 10.1111/jerd.12529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Dharrab A. Effect of energy drinks on the color stability of nanofilled composite resin. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2013;14:704–11. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pepelascov DE, de Castro-Hoshino LV, da Silva LH, Hirata R, Sato F, Baesso ML, et al. Opalescence and color stability of composite resins: An in vitro longitudinal study. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26:2635–43. doi: 10.1007/s00784-021-04232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]