Abstract

Malocclusion has been linked to various factors out of which certain dietary patterns and unhealthy habits are the most overlooked. The dietary patterns and unhealthy habits vary according to socioeconomic status. The present research was aimed to perform an association of malocclusion severity with socioeconomic status. This study was done in a retrospective manner and was conducted at Saveetha Dental College. A total of 241 clinical case records of the participants with malocclusion reporting for orthodontic therapy were selected and enrolled for the study. Data on the socioeconomic status and the severity of malocclusion as assessed with the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Needs (IOTNs) index were noted. All these records were collected and entered into Excel and then analyzed through statistics. Descriptive statistics and nonparametric Chi-square tests were performed. From the analysis, the proportion of IOTN Grade 1 malocclusion (30%) was found to be the highest. The highest number of patients with Grade 1 malocclusion belonged to the lower socioeconomic class. Socioeconomic status and the severity of malocclusion were significantly associated with each other. Malocclusion prevalence and severity were more among participants belonging to lower socioeconomic groups.

Keywords: Dental aesthetic index, Index of orthodontic treatment needs, Innovative, Malocclusion, Social status

INTRODUCTION

Malocclusion is termed a deviation in the interarch relationship in any plane or when a tooth is inappropriately positioned, as well as abnormalities in the form, number, and developmental position of teeth that are outside of normal boundaries.[1] It is primarily a clinically significant deviation from normal occlusion or tooth interdigitation. The popularly used Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI) and index of orthodontic treatment need (IOTN)[2,3] indices were used to estimate the limit and severity of malocclusion in a person or a population for this study. Malocclusion treatment has been connected to a higher level of subjectivity and a unique perspective on treatment demands.[4] Despite the inadequacy of evidence linking psychosocial well-being to tooth malalignment, it has been proven that self-perception has an impact on facial traits, including oral esthetics.[5] In older teens and young adults, physical attraction has a considerable impact on colonial interactions and self-perception, which can impact their quality of life significantly.[6,7,8]

The reasons for malocclusion affecting each individual have been accredited to inheritable and environmental factors.[9] There are hereditary patterns for facial characteristics including jaw size and tooth size. Occlusion is caused by a variety of environmental factors, one of which appears to be diet. However, little research has been done on the relationship between food and malocclusion of the teeth.[10] Malocclusion has also been linked to certain dietary patterns and unhealthy habits.[11] Nutrition has also been connected to other anomalies such as bone deformities and cartilage derangement. An individual's diet and nutrition are intrinsically related to his or her socioeconomic status.[12] Our team has conducted many studies that have contributed to the high number of publications.[13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] The aim of the study was to report on the association of severity of malocclusion with the socioeconomic status of an individual.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study included a total of 241 patients (n = 241) from various age groups and genders who underwent treatment for malocclusion at a private dental hospital in Chennai city.

The study comprised participants between the age group of 18 and 40 years, regardless of gender, who reported to the department with a chief complaint of malocclusion and were treated there. Before the study began, the ethical committee granted their approval (IHEC/SDC/ORTHO/21/232). After describing the study's purpose to the participants, oral agreement was acquired. The IOTNs were used to determine the malocclusion severity (IOTN). The Kuppuswamy scale was used to determine each patient's socioeconomic position. We used descriptive statistics and nonparametric Chi-square testing.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

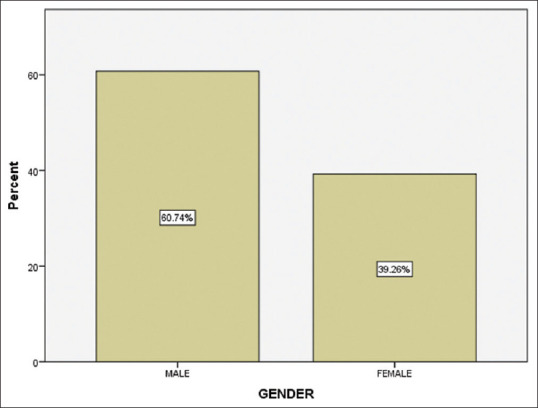

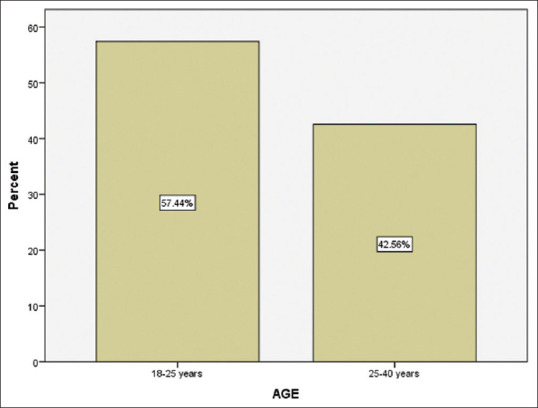

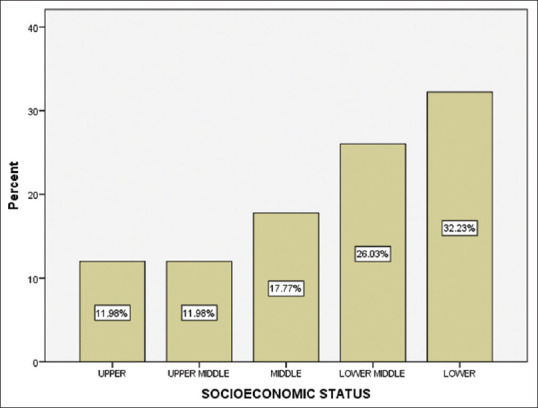

A total of 241 patients took part in the research. The gender and age distribution of the included sample are shown in Figures 1 and 2. According to the Kuppuswamy socioeconomic status scale, around 12% of the participants are upper-middle class, 12% higher-middle class, 18% middle class, 26% lower-middle class, and 32% lower class. The lower class percentage was higher [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Gender distribution of the included sample

Figure 2.

Distribution of the included sample in different age groups.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the included subjects in different socioeconomic groups

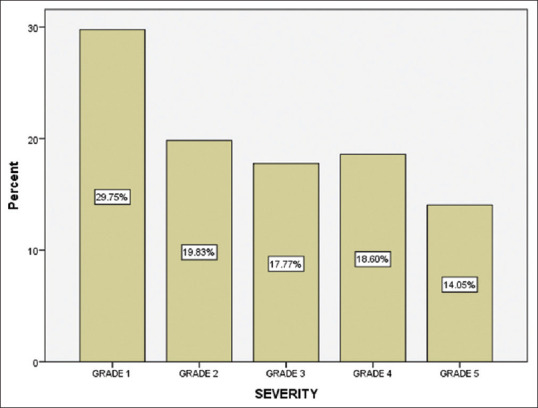

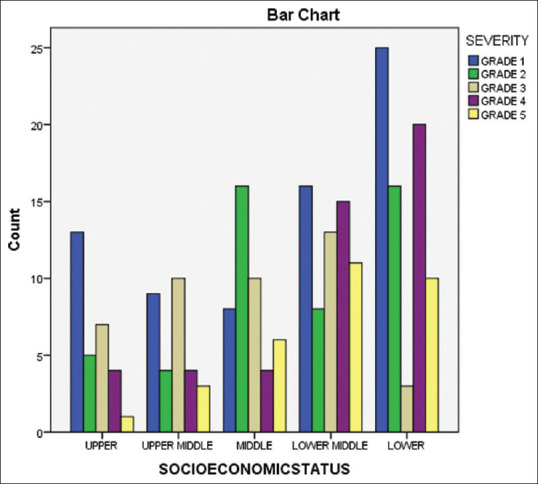

According to IOTN, 30% of the included participants presented with Grade 1 malocclusion, 20% presented with Grade 2 malocclusion, 18% presented with Grade 3 malocclusion, 19% presented with Grade 4 malocclusion, and 13% had Grade 5 malocclusion [Figure 4]. The P was found to be < 0.05, according to statistics. As a result, there was a high correlation between socioeconomic position and the severity of malocclusion [Figure 5].

Figure 4.

Distribution of subjects in different IOTN grades.

Figure 5.

The relationship between socioeconomic class and the severity of malocclusion is depicted in a bar diagram. There was a high correlation between socioeconomic status and the severity of malocclusion (Chi-square test; P = 0.003)

After dental caries, the most common dental problem in India is malocclusion among young adults and children.[33] In the Indian population, the frequency of malocclusion has been estimated to be between 22% and 33% in similar age groups.[34] Several indices have been developed to quantify the severity of certain malocclusion traits. These indicators assess the severity of malocclusion, either in terms of treatment requirements or as a deviation from ideal occlusion.[35] Despite the fact that there are a number of indices and metrics for the assessment of malocclusion, there is no universal consensus on which one is best for varying situations. According to Bellot-Arcs et al., IOTNs and DAI were used more frequently in cross-sectional studies;[36] IOTN is utilized mostly in child and adolescent populations. According to previous studies, males had higher orthodontic treatment demands also, in this study, it was noted that males had a higher incidence of malocclusion.[37,38,39,40]

In the present study, about 30% were Grade 1 malocclusion, 20% were Grade 2 malocclusion, 18% were Grade 3 malocclusion, 19% were Grade 4 malocclusion, and 13% were Grade 5 malocclusion. According to the results of an IOTN index research conducted by Gudipaneni et al.[41] just 21% of all participants were in the extreme need category for therapy (IOTN Grades 4 and 5), while the borderline need was for 29.3% of the population, and 49.4% of participants had Grades 1 and 2 a need for treatment. These findings matched those of our research. According to Al-Azemi and Artun[42] for over 30% of teenage Kuwaiti females, there was a definite treatment need (Grades 4 and 5). According to Hedayati et al.[43] of the Iranian population, 18.39% had a severe or very severe need for therapy, 25.8% were borderline, 48.1% had a little need, and 7.63% of the population did not have a need for treatment.

Borzabadi-Farahani et al. showed that there was a clear need for orthodontic treatment in 36.1% of Iranian school children, treatment need in 20.2% was moderate need, and 43.8% had a slight or no need for treatment.[44]

The IOTN index is employed in epidemiological research but its ability to predict prospective functional inadequacies or oral health concerns is questionable. Revalidation of the IOTN index may be required in future as a result of new study findings.[45]

The study's drawback was that the link between malocclusion severity and socioeconomic position was only seen since the patients studied were from a specific group. Future research with higher sample size and a diverse population should be conducted in future.

CONCLUSION

The socioeconomic status of the participants is related to malocclusion severity. Malocclusion prevalence and severity was higher among participants in the lower socioeconomic group.

Financial support and sponsorship

The current research is supported by Saveetha University, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences and Murugan Industries, Private Limited, Chennai.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their appreciation to the management of Saveetha University Dental College and Hospital for their continuous support and cooperation with the research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kharbanda OP. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2019. Orthodontics: Diagnosis of & Management of Malocclusion & Dentofacial Deformities –E Book ISBN: 978-81-312-4281-2, e-ISBN 978-81-312-4236-9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brook PH, Shaw WC. The development of an index of orthodontic treatment priority. Eur J Orthod. 1989;11:309–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ejo.a035999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz MI. Angle classification revisited 2: A modified Angle classification. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992;102:277–84. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(05)81064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borzabadi-Farahani A. An insight into four orthodontic treatment need indices. Prog Orthod. 2011;12:132–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pio.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burden DJ. Oral health-related benefits of orthodontic treatment. Semin Orthod. 2007;13(2):76–80. doi: 10.1053/j.sodo2007.03.002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marques LS, Pordeus IA, Ramos-Jorge ML, Filogônio CA, Filogônio CB, Pereira LJ, et al. Factors associated with the desire for orthodontic treatment among Brazilian adolescents and their parents. BMC Oral Health. 2009;9:34. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-9-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paula DF, Jr, Silva ÉT, Campos AC, Nuñez MO, Leles CR. Effect of anterior teeth display during smiling on the self-perceived impacts of malocclusion in adolescents. Angle Orthod. 2011;81:540–5. doi: 10.2319/051710-263.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiyak HA. Does orthodontic treatment affect patients'quality of life? J Dent Educ. 2008;72:886–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Proffit WR, Fields HW, Sarver DM. Contemporary Orthodontics –E-Book. St. Louis Mo: eBook ISBN: 9780323543880: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proffit WR, Fields HW, Jr, Moray LJ. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in the United States: estimates from the NHANES III survey. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998;13:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren JJ, Bishara SE, Steinbock KL, Yonezu T, Nowak AJ. Effects of oral habits'duration on dental characteristics in the primary dentition. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:1685–93. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsson E. Dummy- and finger-sucking habits with special attention to their significance for facial growth and occlusion. 7. The effect of earlier dummy- and finger-sucking habit in 16-year-old children compared with children without earlier sucking habit. Swed Dent J. 1978;2:23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felicita AS. Orthodontic extrusion of Ellis Class VIII fracture of maxillary lateral incisor –The sling shot method. Saudi Dent J. 2018;30:265–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandrasekar R, Chandrasekhar S, Sundari KK, Ravi P. Development and validation of a formula for objective assessment of cervical vertebral bone age. Prog Orthod. 2020;21:38. doi: 10.1186/s40510-020-00338-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arvind PT, Jain RK. Skeletally anchored forsus fatigue resistant device for correction of Class II malocclusions –A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2021;24:52–61. doi: 10.1111/ocr.12414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan A, Verpoort F, Asiri AM, Hoque ME, Bilgrami AL, Azam M, et al. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Chemical Reactions: From Organic Transformations to Energy Applications. eBook ISBN: 9780128232620 Elsevier; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alam MK, Alfawzan AA, Haque S, Mok PL, Marya A, Venugopal A, et al. Sagittal jaw relationship of different types of cleft and non-cleft individuals. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:651951. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.651951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marya A, Venugopal A. The use of technology in the management of orthodontic treatment-related pain. Pain Res Manag 2021. 2021:5512031. doi: 10.1155/2021/5512031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adel S, Zaher A, El Harouni N, Venugopal A, Premjani P, Vaid N. Robotic applications in orthodontics: Changing the face of contemporary clinical care. Biomed Res Int 2021. 2021:9954615. doi: 10.1155/2021/9954615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivakumar A, Nalabothu P, Thanh HN, Antonarakis GS. A comparison of craniofacial characteristics between two different adult populations with class II malocclusion –A cross-sectional retrospective study. Biology (Basel) 2021;10:438. doi: 10.3390/biology10050438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venugopal A, Vaid N, Bowman SJ. Outstanding, yet redundant? After all, you may be another Choluteca Bridge! Semin Orthod. 2021;27:53–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gopalakrishnan U, Felicita AS, Mahendra L, Kanji MA, Varadarajan S, Raj AT, et al. Assessing the potential association between microbes and corrosion of intra-oral metallic alloy-based dental appliances through a systematic review of the literature. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9:631103. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.631103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venugopal A, Vaid N, Bowman SJ. The quagmire of collegiality vs. competitiveness. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2021;159:553–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marya A, Karobari MI, Selvaraj S, Adil AH, Assiry AA, Rabaan AA, et al. Risk perception of SARS-CoV-2 infection and implementation of various protective measures by dentists across various countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:5848. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramesh A, Varghese S, Jayakumar ND, Malaiappan S. Comparative estimation of sulfiredoxin levels between chronic periodontitis and healthy patients –A case-control study. J Periodontol. 2018;89:1241–8. doi: 10.1002/JPER.17-0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arumugam P, George R, Jayaseelan VP. Aberrations of m6A regulators are associated with tumorigenesis and metastasis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Oral Biol. 2021;122:105030. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2020.105030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joseph B, Prasanth CS. Is photodynamic therapy a viable antiviral weapon against COVID-19 in dentistry? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2021;132:118–9. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2021.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ezhilarasan D, Apoorva VS, Ashok Vardhan N. Syzygium cumini extract induced reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis in human oral squamous carcinoma cells. J Oral Pathol Med. 2019;48:115–21. doi: 10.1111/jop.12806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duraisamy R, Krishnan CS, Ramasubramanian H, Sampathkumar J, Mariappan S, Navarasampatti Sivaprakasam A. Compatibility of nonoriginal abutments with implants: Evaluation of microgap at the implant-abutment interface, with original and nonoriginal abutments. Implant Dent. 2019;28:289–95. doi: 10.1097/ID.0000000000000885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gothandam K, Ganesan VS, Ayyasamy T, Ramalingam S. Antioxidant potential of theaflavin ameliorates the activities of key enzymes of glucose metabolism in high fat diet and streptozotocin – Induced diabetic rats. Redox Rep. 2019;24:41–50. doi: 10.1080/13510002.2019.1624085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ezhilarasan D. Hepatotoxic potentials of methotrexate: Understanding the possible toxicological molecular mechanisms. Toxicology. 2021;458:152840. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2021.152840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preethi KA, Sekar D. Dietary microRNAs: Current status and perspective in food science. J Food Biochem. 2021;45:e13827. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sng JHT, Lum JL, Loy CHR, Yeo JF. A diagnostic challenge: Gingival lesions in a post irradiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma patient. Austin Head Neck Oncol. 2021;4(1):1010. doi: 10.26420/austinheadneckoncol.2021.1010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhardwaj VK, Veeresha KL, Sharma KR. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment needs among 16 and 17 year-old school-going children in Shimla city, Himachal Pradesh. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:556–60. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.90296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Firestone AR, Beck FM, Beglin FM, Vig KW. Evaluation of the peer assessment rating (PAR) index as an index of orthodontic treatment need. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;122:463–9. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.128465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellot-Arcís C, Montiel-Company JM, Almerich-Silla JM, Paredes-Gallardo V, Gandía-Franco JL. The use of occlusal indices in high-impact literature. Community Dent Health. 2012;29:45–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oshagh M, Salehi P, Pakshir H, Bazyar L, Rakhshan V. Associations between normative and self-perceived orthodontic treatment needs in young-adult dental patients. Korean J Orthod. 2011;41(6):440. doi: 10.4041/kjod2011.41.6.440. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Onyeaso CO, Arowojolu MO. Perceived, desired, and normatively determined orthodontic treatment needs among orthodontically untreated Nigerian adolescents. West Afr J Med. 2003;22:5–9. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v22i1.27968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baca-Garcia A, Bravo M, Baca P, Baca A, Junco P. Malocclusions and orthodontic treatment needs in a group of Spanish adolescents using the Dental Aesthetic Index. Int Dent J. 2004;54:138–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernabé E, Flores-Mir C. Orthodontic treatment need in Peruvian young adults evaluated through dental aesthetic index. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:417–21. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0417:OTNIPY]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gudipaneni RK, Aldahmeshi RF, Patil SR, Alam MK. The prevalence of malocclusion and the need for orthodontic treatment among adolescents in the northern border region of Saudi Arabia: An epidemiological study. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18:16. doi: 10.1186/s12903-018-0476-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Azemi R, Artun J. Orthodontic treatment need in adolescent Kuwaitis: Prevalence, severity and manpower requirements. Med Princ Pract. 2010;19:348–54. doi: 10.1159/000316371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hedayati Z, Fattahi HR, Jahromi SB. The use of index of orthodontic treatment need in an Iranian population. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2007;25:10–4. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.31982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borzabadi-Farahani A, Borzabadi-Farahani A, Eslamipour F. Orthodontic treatment needs in an urban Iranian population, an epidemiological study of 11-14 year old children. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2009;10:69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borzabadi-Farahani A. A review of the oral health-related evidence that supports the orthodontic treatment need indices. Prog Orthod. 2012;13:314–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pio.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]