Abstract

Cardiac injury initiates a tissue remodeling process in which aberrant fibrosis plays a significant part, contributing to impaired contractility of the myocardium and the progression to heart failure. Fibrotic remodeling is characterized by the activation, proliferation, and differentiation of quiescent fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, and the resulting effects on the extracellular matrix and inflammatory milieu. Molecular mechanisms underlying fibroblast fate decisions and subsequent cardiac fibrosis are complex and remain incompletely understood. Emerging evidence has implicated the Hippo-Yap signaling pathway, originally discovered as a fundamental regulator of organ size, as an important mechanism that modulates fibroblast activity and adverse remodeling in the heart, while also exerting distinct cell type-specific functions that dictate opposing outcomes on heart failure. This brief review will focus on Hippo-Yap signaling in cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts, and other non-myocytes, and present mechanisms by which it may influence the course of cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction.

Keywords: Hippo signaling pathway, Yap, Taz, Cardiac Remodeling, fibrosis, inflammation, heart failure, myofibroblast

Introduction

Cardiac fibrosis and adverse cardiac remodeling are present in all etiologies of heart disease. The act of remodeling the extracellular matrix (ECM) is an active process with pleiotropic effects. While it is needed to prevent wall rupture in response to an acute injury associated with extensive myocyte loss, persistent fibrosis also drives pathology, and strongly correlates with worsened cardiac outcomes, including increased risk for arrhythmias and progression to heart failure, making it a clinical concern of great importance1. Importantly, there are currently no effective treatments for fibrosis, either to limit or reverse the process. Based on studies leveraging cell type-specific and inducible genetic mouse models to manipulate in vivo gene expression, it has become evident that the resident fibroblast is the predominant cell type maintaining cardiac ECM at baseline, and is largely responsible for coordinating and executing fibrotic remodeling in response to stress2–6. An emerging paradigm posits that cardiac fibroblasts are more heterogeneous and transit between more states than originally thought including quiescent or resting fibroblasts, activated intermediate fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and matrifibrocytes7. However, a more comprehensive understanding of how fibroblasts transition between these diverse functional phenotypes during injury and wound healing, and how fibroblasts interact with and influence other cells within the myocardium, will likely be essential to developing improved therapeutic interventions targeting pathological cardiac remodeling.

Integrative regulation of fibroblast state and activity

Until recently, resident quiescent fibroblasts were thought to become activated and terminally differentiate to myofibroblasts, the cell type largely responsible for increased production of matricellular proteins and ECM modification following stress, eventually succumbing to apoptosis and tissue clearance. However, through the use of single cell RNA sequencing, it has become clear that determination of fibroblast fate following injury such as myocardial infarction (MI) requires more nuanced classification, and is likely more fluid than originally thought8. In the healthy heart, quiescent fibroblasts make up roughly 15% of non-myocytes9, and greater than 95% of these resident fibroblasts give rise to the active myofibroblast population post injury2. Evidence indicates that periostin (Postn)-expressing activated fibroblasts peak ~2–3d post-MI and are highly proliferative, whereas differentiated myofibroblasts are greatest roughly 5–7 days after MI, and are defined by enhanced expression of fibrillar collagens and α smooth muscle actin (αSMA, Acta2 gene). Approximately 2 weeks post-MI and beyond, the matrifibrocyte predominates the mature scar, and exhibits high levels of chondrocyte and osteogenic gene expression, presumably to maintain scar integrity4, 5, 10, 11. Importantly, not all active fibroblasts transition to the myofibroblast state as evidenced by αSMA expression in only a subset of fibroblasts following heart injury, suggesting multifaceted regulation of fate decisions12. Moreover, the progressive loss of identifiable myofibroblast markers in cells of fibroblast origin that persist long-term following injury suggests this status is transient and is resolved through some combination of further differentiation/maturation (i.e. matrifibrocyte)10, deactivation4, and/or senescence, further highlighting the complexity of fibroblast state determination.

Elucidating the underlying signaling mechanisms that modulate fibroblast activation during cardiac stress are vitally important and have been the focus of much study. Fibroblast fate is regulated by extracellular cues that activate complex signaling networks and epigenetic modulation that ultimately results in modified transcriptional responses. Soluble ligands such as transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), wingless/integrated (Wnt), or angiotensin II (AngII) signal through cognate receptors to activate downstream effectors and initiate cell responses1, 13. Convincing evidence has demonstrated that mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) p38α is a critical node regulating fibroblast function14. p38 is activated by non-canonical TGF-β signaling, as well as mechanical stimuli, and facilitates fibroblast activation through multiple mechanisms including serum response factor (SRF)- myocardin related transcription factor A (MRTF-A) transcriptional activation15 and transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily C member 6 (TRPC6)-mediated Ca2+ signaling to promote Calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) function16. Histone and chromatin modification also regulate fibroblast differentiation. Inhibitors of class I histone deacetylases (HDACs), as well as bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET) family inhibitors, can prevent transcription of key fibroblast activation genes17, suppress cardiac fibroblast proliferation, and antagonize myofibroblast differentiation18, 19 demonstrating the importance of epigenetic regulation in determining fibroblast state transitions20. Moreover, the RNA binding protein muscleblind-like1 (MBNL1) has been shown to stabilize and alternatively splice transcripts of many previously identified mediators of myofibroblast differentiation providing an additional level of positive regulation of fibrotic signaling pathways21.

Hippo-Yap pathway overview

The Hippo signaling pathway is a fundamental growth regulatory mechanism that was originally discovered in Drosophila and is evolutionarily conserved to humans. It is a kinase cascade whose activation is controlled by diverse inputs including growth factors, oxidative stress, and mechanical perturbation to mediate various cellular outputs, e.g. proliferation, differentiation, and survival22. The core components of the mammalian pathway include the serine/threonine kinases mammalian STE20-like (Mst1/2) and large tumor suppressor kinases (Lats1/2), the scaffold proteins Salvador (Sav1) and Mps one binder kinase activator (MOB1A/B), and the transcriptional co-activators Yes-associate protein (Yap) and transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (Taz). Hippo pathway activation results in enhanced kinase activity leading to increased phosphorylation and cytosolic retention/degradation of Yap/Taz. When Hippo is turned off, Yap/Taz accumulate in the nucleus and stimulate expression of genes that regulate cell cycling, survival, and cell fate, a response that is primarily mediated through interaction with the TEA domain family transcription factors (TEAD1–4), although partnering with additional transcription factors also occurs22.

There is accumulating evidence that Hippo-Yap signaling modulates fibroblast activation and differentiation, and can impact the extent of fibrosis following tissue injury in multiple organs. Increased mechanical stresses are a hallmark of fibrotic remodeling and can result from altered cell-cell contacts, changes in cellular tension, or differences in ECM stiffness. The actin cytoskeleton is highly responsive to these mechanical cues, which are transduced intracellularly by membrane spanning protein complexes (e.g. adherens junctions, focal adhesions) and stimulate increased F-actin stress fiber formation. Yap/Taz monitor and respond to altered actin dynamics through increased activation, thereby linking mechanosensation to gene expression modulation23. For example, enhanced substrate rigidity causes increased assembly of focal adhesion complexes and stress fiber formation, which elicits Yap/Taz nuclear localization and activity24. Soluble factors including TGF-β, Wnt, and AngII have also been shown to cause Yap/Taz upregulation and promote enhanced function in fibroblasts through Hippo dependent and independent mechanisms25, 26. Importantly, this Yap/Taz mediated transcriptional response has been directly implicated in mechanical stress-induced fibroblast proliferation, migration, and expression of myofibroblast and contractile associated genes including pro-collagen, αSMA, brain derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf), fibronectin, and plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1)27–29. Conversely, fibroblasts cultured on soft matrix had reduced Yap/Taz function and suppressed fibroblast-related gene induction30. Additional studies have demonstrated key in vivo roles for Yap and Taz in mediating fibroblast activation and ECM remodeling in liver, kidney, and lung27, 28, 31, suggesting broad implications for Yap/Taz signaling in cell fate responses to physical stress and tissue fibrosis and remodeling.

Hippo-Yap signaling in cardiomyocytes: heart development and disease

Disruption of the Hippo pathway via cardiomyocyte deletion of Sav1 (or Mst1/2, or Lats1/2) during development, led to enhanced Yap activity and hyperproliferation of cardiomyocytes, abnormal heart growth, thickened ventricles, and embryonic lethality32 (Table). Conversely, targeted cardiomyocyte deletion of Yap resulted in cardiac hypoplasia, heart failure and early embryonic death, demonstrating the importance of balanced Yap activation for proper heart development. Hippo-Yap signaling in adult cardiomyocytes also plays a critical role in modulating responses to cardiac stress33, 34. Cardiac Mst1 is activated in response to ischemic and non-ischemic pressure overload (PO) stress35, 36. Transgenic inhibition of cardiomyocyte Mst1 was shown to attenuate adverse remodeling and improve survival through upregulation of autophagy and inhibition of apoptosis caused by MI37. Similarly, inhibition of cardiomyocyte Lats2 reduced apoptosis and cardiac dysfunction induced by PO stress38. The role of Sav1 is less straightforward, as inducible myocyte deletion in the adult heart triggered Yap activation and reversed MI-induced adverse remodeling and heart failure39, demonstrating a robust cardioprotective benefit. On the other hand, postnatal Sav1 deficiency led to worsened cardiac function in response to chronic PO40. This difference in outcomes is likely due to the type of stress imposed (permanent coronary artery occlusion vs increased left ventricular afterload) and the resulting effect on cardiomyocyte loss, which would be ameliorated by enhanced cardiomyocyte proliferation in the setting of MI but not necessarily during PO, where persistent myocyte dedifferentiation impaired contractile function.

Table.

Cardiac effects of Hippo-Yap pathway modulation in mice.

| Gene | Model | Intervention | Phenotype | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yap | cKO | Nkx2.5-Cre | Lethal by E10.5, reduced CM proliferation, thin myocardium. | 33 |

| Yap | cKO | Tnnt2-Cre | Lethal by E16.5, reduced ventricle size, reduced CM proliferation, hypoplastic myocardium. | 34 |

| Yap | cKO | αMHC-Cre | Die between 11–20 weeks, dilated cardiomyopathy, increased CM apoptosis, and increased fibrosis. Defective neonatal cardiac regeneration post-MI. Hemizygous mice showed attenuated adaptive growth, worsened remodeling and greater cardiac dysfunction after MI or PO stress. | 41–43 |

| Yap | cTG | αMHC-YapS112A | Increased heart size, wall thickness, CM proliferation, improved function post-MI injury. | 42 |

| Yap | cKO | Tcf21-MCM | Attenuated fibrosis and improved cardiac function after MI. | 26 |

| Yap/Taz | cKO | Col1a2-CreERT | Reduced fibrosis and inflammation with improved heart function post-MI injury. | 25 |

| Yap/Taz | cKO | LysM-Cre | Attenuated fibrotic remodeling, reduced inflammation and enhanced angiogenesis in response to MI. | 50 |

| Yap/Taz | cKO | Wt1-CreERT2 | Increased inflammation, fibrosis, wall rupture, and lethality following MI stress. | 55 |

| Sav1 | cKO | Nkx2.5-Cre | Increased CM proliferation, cardiomegaly, ventricular septal defect. | 32 |

| Sav1 | cKO | αMHC-CreERT2 | Cardioprotective after MI, reduced fibrosis, improved function | 39 |

| Sav1 | cKO | αMHC-Cre | Increased CM proliferation/dedifferentiation, worsened heart function after PO stress. | 40 |

| Lats1/2cKO | Nkx2.5-Cre | Excessive heart growth, ventricular septal defect. | 32 | |

| Lats1/2cKO | Wt1-CreERT2 | Lethal by E15.5, defective transition of epicardial precursors, reduced mature cardiac fibroblasts, impaired coronary vessel development. | 46 | |

| Lats1/2cKO | Tcf21-MCM | Spontaneous fibrosis, myofibroblast differentiation, increased inflammation, and cardiac dysfunction. | 49 | |

| Lats2 | cTG-Dn | αMHC-Lats2K697A | Reduced CM apoptosis and improved fun ction after PO stress | 38 |

| Mst1/2 | cKO | Nkx2.5-Cre | Excessive heart growth, vent icular septal defect. | 32 |

| Mst1 | cTG-Dn | αMHC-Mst1K59R | Increased autophagy, reduced scar size, and improved cardiac function after MI. | 37 |

| Rassf1a | cKO | αMHC-Cre | Reduced CM apoptosis and fibrosis, with improved cardiac function after PO stress. | 36 |

| Rassf1a | cTG-Dn | αMHC-Rassf1aL308P | Attenuated CM apoptosis and fibrosis in response to PO. | 36 |

cKO, conditional knockout; cTG, cell type-specific transgenic; CM, cardiomyocyte; Dn, dominant-negative; MI, myocardial infarction; PO, pressure overload.

In contrast to the interventions above that upregulated Yap activity, cardiomyocyte-specific postnatal deletion of Yap caused spontaneous dilated cardiomyopathy associated with increased apoptosis and premature death between 11–20 weeks41, 42. Consistently, mice with hemizygous reduction of myocyte Yap had increased cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction following either MI or PO stress41, 43. Neonatal cardiac regeneration, which occurs in mice prior to P744, was abolished in Yap deficient mice, whereas cardiac expression of a constitutively active Yap was able to attenuate myocyte apoptosis and fibrosis, and improve heart function in response to MI42. Additionally, cardiomyocyte Yap was shown to promote the expression of Wntless and subsequent secretion of Wnt5a and Wnt9a, which mediated paracrine inhibitory effects on cardiac fibroblasts resulting in reduced inflammation and fibrosis, and enhanced scar resolution after MI45. In sum, it has become increasingly clear that cardiomyocyte modulation of Hippo signaling is a critical determinant of cardiac remodeling and dysfunction in response to pathological stress, and interventions that promote Yap activation in the cardiomyocyte confer protection through enhanced survival and regenerative potential in the adult heart.

Function of Hippo-Yap/Taz in cardiac fibroblasts: homeostatic and injury responses

Studies using targeted genetic approaches in mice have demonstrated an important role for Hippo-Yap in modulating cardiac fibroblast maturation as well as myofibroblast differentiation. Epicardial cell-specific deletion of Lats1/2 kinases during embryonic development using the Wt1CreERT driver mice resulted in defective transition of epicardial precursors to mature cardiac fibroblasts, improper coronary vessel formation, and rapid lethality46. In a series of elegant single cell RNA sequencing and lineage tracing experiments, this was shown to be driven through aberrant Yap activation, and at least partly mediated through newly identified Yap-TEAD target genes, Dpp4 and Dhrs3. Enhanced Dhrs3 expression antagonized retinoic acid signaling to prevent epicardial fibroblast formation, while upregulation of the matricellular factor Dpp4 altered ECM composition and blunted normal vascular development. These results indicate a critical role for Lats-Yap in the proper state transition of epicardial precursors to differentiated cardiac fibroblasts that occurs during cardiogenesis.

Conditional deletion of Lats1/2 in adult cardiac fibroblasts using Tcf21-MerCreMer (to target resident cardiac fibroblasts for Cre expression) was sufficient to induce spontaneous fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction within 3 weeks of tamoxifen administration29. Hearts from Lats1/2 mutant mice also contained increased populations of inflammatory cardiac fibroblasts, as well as increased myofibroblast-like cells that arose from quiescent fibroblasts indicating that Lats1/2 deletion in resting cardiac fibroblasts promotes a cell state transition typically seen following injury. Enhanced Yap activity in Lats1/2 targeted cells mediated myofibroblast differentiation, and was also responsible for non-cell autonomous paracrine effects that elicited cardiac myeloid cell recruitment. Importantly, Lats1/2 deficient mice subjected to MI had augmented fibrosis, decreased survival, and an extension of the cardiac fibroblast proliferative window, a phenotype that was partly rescued by concomitant deletion of Yap and Taz. ATAC-seq analysis of global chromatin accessibility signatures indicated that Lats1/2 cardiac fibroblast deletion favored a myofibroblast-like epigenetic and transcriptional profile, likely mediated by enrichment of Yap-TEAD occupancy at active enhancer regions. These findings demonstrate a key role for Lats-Yap in modulating cardiac fibroblast state transition, whereby Lats1/2 activity restrains myofibroblast differentiation of quiescent fibroblasts and pro-inflammatory signaling between cell types.

Myocardial infarction fundamentally alters properties of the ECM and leads to heterogeneity of collagen deposition and alignment. Disturbed collagen fiber organization not only impairs heart pump function, but also signals locally to endogenous cells to influence their behavior. To this effect, recent work has elegantly demonstrated that regions of infarcted myocardium with aligned collagen were more prevalent at the border zone and exhibited myofibroblast enrichment when compared to the more disorganized collagen containing infarct core47. Moreover, providing an aligned ECM substrate in vitro was sufficient to promote myofibroblast differentiation of adult cardiac fibroblasts, and this response was mediated by focal adhesion-dependent upregulation of a Yap-TEAD-p38 signaling complex. These findings expanded upon previous work that identified a requirement of fibroblast p38α for scar formation and myofibroblast differentiation in vivo14, and revealed a novel mechanism that links p38 to YAP posttranslational regulation and activation of myofibroblast transcriptional activity in response to collagen fiber disorganization after MI.

Several studies have examined the role of cardiac fibroblast Yap and Taz by directly modulating their expression in vivo. Yap is upregulated and activated in cardiac fibroblasts 3–5 days following MI, and selective deletion of Yap in quiescent cardiac fibroblasts using Tcf21-MerCreMer prior to infarct attenuated the extent of cardiac fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition, and preserved heart function26. Yap was shown to positively regulate expression of MRTF-A through TEAD-dependent transcription, and Yap mutant mice had reduced myocardial MRTF-A post-MI. No difference in cardiac hypertrophy was observed, although cardiomyocyte apoptosis was reduced in Yap deficient mice, indicating potential pathological paracrine Yap dependent signaling from cardiac fibroblasts to myocytes during MI. Of note, the Hippo pathway activator, Ras association domain family 1 isoform A (RASSF1A), was shown to suppress the expression and secretion of tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) from cardiac fibroblasts thereby influencing cardiomyocyte function, however the role of Yap in mediating this response was not defined36. Importantly, similar results were observed using a different Cre driver (Col1a2-CreERT) to induce deletion of both Yap and Taz in cardiac fibroblasts prior to MI25. Targeted inhibition of both genes prevented cardiac dysfunction and reduced fibrosis after injury. Intriguingly, no increase in ventricular rupture was observed in Yap/Taz deficient mice after MI indicating other pathways mediate reparative processes. Double mutant mice also had attenuated macrophage recruitment and blunted pro-inflammatory gene expression. Indeed, cardiac fibroblasts deficient for Yap/Taz had reduced ability to stimulate macrophage inflammatory polarization via impaired IL-33 paracrine signaling from cardiac fibroblasts. Together these studies demonstrate the important role for cardiac fibroblast Yap/Taz in mediating fibrotic remodeling and dysfunction in response to ischemic injury, a clear contrast to their beneficial functions in cardiomyocytes (Figure).

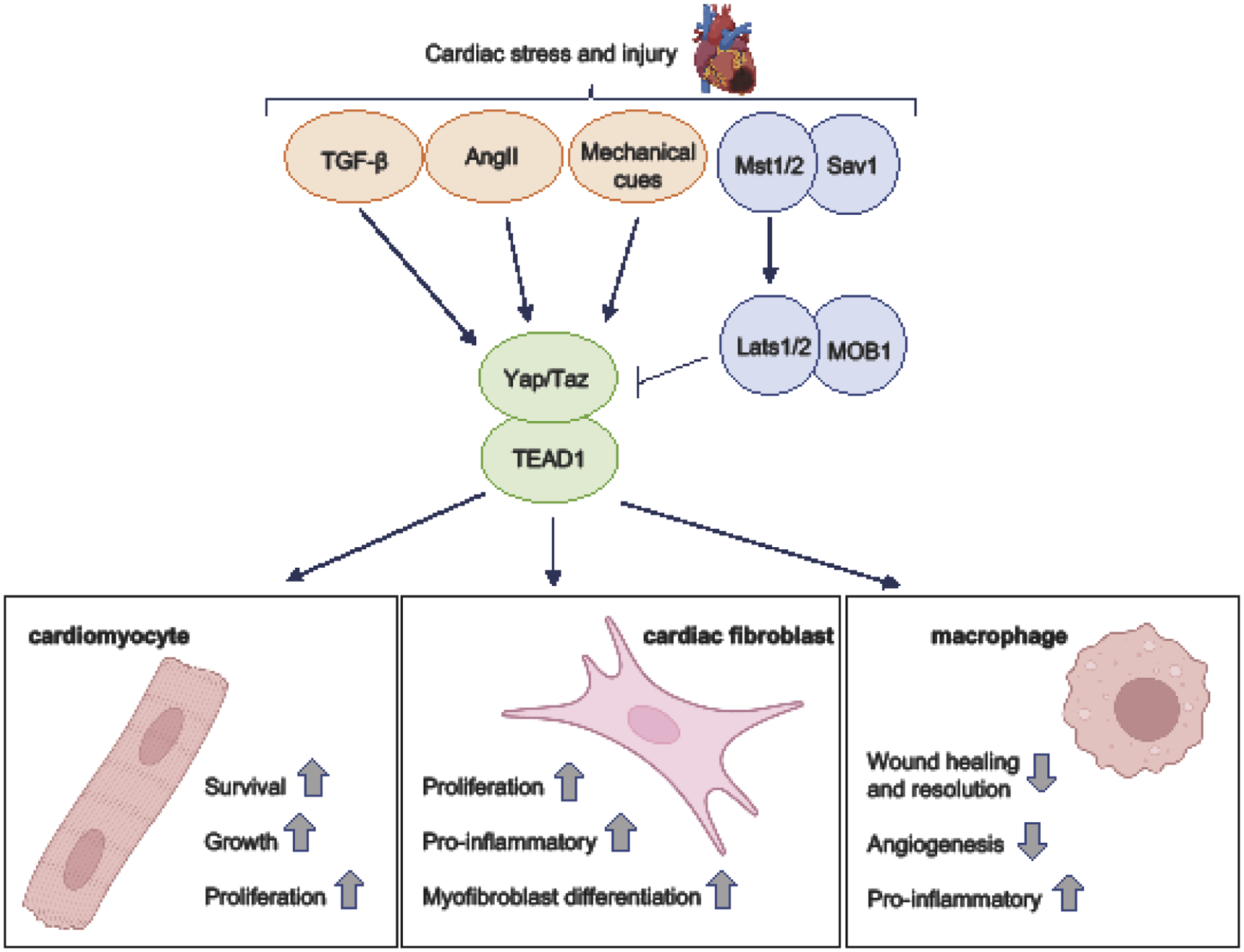

Figure.

The role of Hippo-Yap signaling in response to cardiac stress – the cell type-specific functions of Yap/Taz activation and their influence on fibrotic remodeling. Cardiac injury resulting from myocardial infarction (MI) or pressure overload (PO) stress can modulate Hippo-Yap signaling in both positive and negative directions and is dependent on downstream signaling mechanism engagement and cell type. Activation of canonical Hippo signaling (i.e. Mst1/2 and Lats1/2) causes the inhibitory phosphorylation of Yap/Taz and their subsequent nuclear exclusion and degradation. In cardiomyocytes, this leads to increased apoptosis, suppression of cell growth and impaired heart function. Conversely, Hippo disruption and Yap activation promotes cardiomyocyte survival, growth, proliferation, and generally attenuates dysfunction. Cardiac stress can also elicit increased availability of soluble factors (e.g. TGF-β, AngII) and altered tissue stiffness, leading to increased Yap/Taz activation. In cardiac fibroblasts, Yap/Taz mediate proliferation, myofibroblast differentiation, and pro-inflammatory signaling including the secretion of cytokines and chemokines that contribute to enhanced immune cell recruitment. Following MI, Yap/Taz are activated in macrophages present in the heart. Myeloid selective deletion of Yap/Taz affords cardioprotection against MI-induced inflammation, adverse fibrotic remodeling, and cardiac dysfunction through effects on macrophage polarization, wound healing and angiogenic responses. Due to disparate outcomes mediated by Hippo-Yap signaling according to cell type, interventions aimed at modulating the pathway therapeutically must prove selective or risk unintended deleterious effects.

To directly investigate the effect of Yap gain of function in cardiac fibroblasts in vivo, an adeno-associated virus-mediated approach was employed48. Ectopic expression of activated Yap was driven by the Tcf21 promoter in mice, and elicited myofibroblast differentiation and increased collagen deposition in the absence of stress. Markers of inflammation including macrophage abundance and pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression were also observed in Yap transduced myocardium. CC motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), which is required for the tissue recruitment of CC motif chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2)-positive monocytes/macrophages49, was shown to be a Yap target gene in cultured cardiac fibroblasts and was upregulated following Yap expression in vivo. A similar phenotype was observed in mice genetically engineered to selectively express active mutant Yap in cardiac fibroblasts25. After MI, Yap transgenic mice showed augmented myocardial fibrosis, elevated myofibroblast burden, and enhanced inflammatory gene expression compared to controls. Taken together, these studies indicate activation of cardiac fibroblast Yap can induce and enhance injury-related fibrotic and inflammatory remodeling in the heart.

Function of Yap/Taz in cardiac macrophages and epicardium to influence inflammation

Macrophages are critical mediators of cardiac inflammation and fibrosis in response to injury. Mice with myeloid selective Yap/Taz deletion (LysM-Cre) showed improved cardiac function following MI injury50. Reduced fibrotic area, along with reduced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, and enhanced expression of angiogenic markers including vascular endothelial growth factor (Vegf) and cluster of differentiation 31 (CD31) were also observed in Yap/Taz double knockout mice. Conversely, using LysM-Cre to drive ectopic expression of activated mutant Yap in the myeloid compartment resulted in increased collagen deposition post-infarct. To investigate a potential mechanism, transcriptome profiling of Yap/Taz double knockout bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) was performed and revealed altered gene expression patterns that indicated impaired pro-inflammatory polarization and an enhanced reparative phenotype. The ability of Yap to directly promote IL-6 expression while transcriptionally repressing arginase 1 (Arg1) via engagement of an HDAC3-nuclear receptor corepressor (NCor1) complex was demonstrated and likely contributed to the shift in polarization and the aberrant inflammatory phenotype. These findings are consistent with reports that Yap exerts pro-inflammatory functions in macrophages in other systems51–54, and supports the hypothesis that interventions to target Yap/Taz inhibition may antagonize pathological remodeling through cell autonomous and non-autonomous mechanisms.

The function of Yap/Taz in the adult epicardium has also been investigated55. Conditional deletion of both genes resulted in a hyperinflammatory response and diffuse fibrosis throughout the LV posterior wall, and was associated with worsened cardiac function and increased mortality after MI. Yap/Taz deletion caused dysregulated cytokine expression, and further analysis identified interferon gamma (IFNγ) as a direct transcriptional target of Yap-TEAD. Blunted IFNγ expression in Yap/Taz deficient mice prevented Treg recruitment and accentuated inflammation in response to infarct. These results demonstrate the importance of Yap/Taz function in the epicardium during ischemic injury to restrain inflammation and pathological remodeling, and serve to highlight once again the cell type-specificity of Hippo-Yap function in the regulation of wound healing processes in the heart.

Implications for human heart disease

The potential relevance of Hippo-Yap in fibrotic remodeling in human heart failure is beginning to emerge. Recent work has reported that Yap expression was downregulated in myocardium from heart failure patients39, however this analysis did not discriminate by cell type and likely reflects Yap status in cardiomyocytes. In contrast, Yap expression and activation were selectively increased in cardiac fibroblasts isolated from heart tissue of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) patients56, indicating that differences in cell type-specific regulation of Hippo-Yap observed in mice may also occur in humans. Additional evidence to suggest Yap involvement in cardiac fibrosis in patients was revealed using RNA sequencing. Enrichment of genes associated with ECM organization and ECM-membrane interactions were found to overlap between DCM cardiac fibroblasts and healthy cardiac fibroblasts expressing active Yap. Moreover, forced Yap expression in healthy human cardiac fibroblasts upregulated myofibroblast-associated gene expression26 and stimulated the ability to contract collagen lattice, while cardiac fibroblasts from DCM patients showed comparable enhanced contractile capability that was abolished by Yap pharmacological inhibition using verteporfin56. These findings implicate Yap activity in diseased cardiac fibroblasts as a potential pathological driver of ECM remodeling in heart failure patients, although more studies are needed to further refine this hypothesis.

Conclusion

Cardiac injury initiates adverse remodeling of the myocardium characterized by excessive deposition of the ECM, increased stiffness, and impaired contractility that contributes to the progression of heart failure. The fibrotic response is incredibly complex, is mediated by multiple integrated signaling pathways, and involves interactions between distinct cell types, yet our understanding of the molecular circuitry that governs it remains incomplete. The Hippo-Yap pathway has emerged as an important mechanism regulating stress responses in cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts, macrophages, and others, and has evident implications for fibrosis, inflammation, and wound healing. The question remains, how do we leverage this knowledge to bridge the translational gap to patients? Future studies should continue to elucidate cell type specific Hippo-Yap functions, which thus far have been shown to mediate selective and sometimes opposing outcomes on cardiac physiology and disease progression. A focus on potential differences in transcription factor accessibility and partnering with Yap/Taz may prove important. Moreover, mechanisms governing how these signals influence cell-to-cell interactions to modulate pathological remodeling of the heart are only beginning to manifest and require further investigation. For example, Hippo-Yap mediates bidirectional communication between immune and cardiac resident cells50, 55, yet how these paracrine actions can be leveraged to improve outcomes remains unclear. It will also be imperative that disease model be carefully considered (e.g. ischemia versus PO) when interpreting the efficacy of Hippo pathway modulation, as the type of injury can elicit distinct responses and may necessitate selective interventions. Ultimately, therapeutics aimed at manipulating this signaling pathway still hold great promise, yet will likely require targeted approaches to alleviate fibrotic responses while maintaining myocardial integrity and function.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01HL127339) and the American Heart Association (AHA 20TPA35490150).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

References

- 1.Frangogiannis NG. Cardiac fibrosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2021;117:1450–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acharya A, Baek ST, Huang G, Eskiocak B, Goetsch S, Sung CY, Banfi S, Sauer MF, Olsen GS, Duffield JS, Olson EN and Tallquist MD. The bHLH transcription factor Tcf21 is required for lineage-specific EMT of cardiac fibroblast progenitors. Development. 2012;139:2139–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore-Morris T, Guimaraes-Camboa N, Banerjee I, Zambon AC, Kisseleva T, Velayoudon A, Stallcup WB, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Cedenilla M, Gomez-Amaro R, Zhou B, Brenner DA, Peterson KL, Chen J and Evans SM. Resident fibroblast lineages mediate pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2921–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanisicak O, Khalil H, Ivey MJ, Karch J, Maliken BD, Correll RN, Brody MJ, SC JL, Aronow BJ, Tallquist MD and Molkentin JD. Genetic lineage tracing defines myofibroblast origin and function in the injured heart. Nature communications. 2016;7:12260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrated that Tcf21 lineage-traced resident cardiac fibroblasts are the predominant source of injury-induced myofibroblasts in the heart, and that periostin is a faithful marker of cardiac myofibroblasts in vivo. This paper also observed myofibroblast de-differentiation to a state resembling quiescent fibroblasts in response to stress application and removal (i.e. transient AngII/PE infusion).

- 5.Ali SR, Ranjbarvaziri S, Talkhabi M, Zhao P, Subat A, Hojjat A, Kamran P, Muller AM, Volz KS, Tang Z, Red-Horse K and Ardehali R. Developmental heterogeneity of cardiac fibroblasts does not predict pathological proliferation and activation. Circ Res. 2014;115:625–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaur H, Takefuji M, Ngai CY, Carvalho J, Bayer J, Wietelmann A, Poetsch A, Hoelper S, Conway SJ, Mollmann H, Looso M, Troidl C, Offermanns S and Wettschureck N. Targeted Ablation of Periostin-Expressing Activated Fibroblasts Prevents Adverse Cardiac Remodeling in Mice. Circ Res. 2016;118:1906–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reichardt IM, Robeson KZ, Regnier M and Davis J. Controlling cardiac fibrosis through fibroblast state space modulation. Cell Signal. 2021;79:109888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farbehi N, Patrick R, Dorison A, Xaymardan M, Janbandhu V, Wystub-Lis K, Ho JW, Nordon RE and Harvey RP. Single-cell expression profiling reveals dynamic flux of cardiac stromal, vascular and immune cells in health and injury. eLife. 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper leveraged single cell RNA sequencing analysis of myocardial tissue after infarction and demonstrated greater heterogeneity of cardiac fibroblast populations at baseline and stress conditions than previously appreciated. These findings also challenged the idea that myofibroblast differentiation is a linear, binary process.

- 9.Pinto AR, Ilinykh A, Ivey MJ, Kuwabara JT, D’Antoni ML, Debuque R, Chandran A, Wang L, Arora K, Rosenthal NA and Tallquist MD. Revisiting Cardiac Cellular Composition. Circ Res. 2016;118:400–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu X, Khalil H, Kanisicak O, Boyer JG, Vagnozzi RJ, Maliken BD, Sargent MA, Prasad V, Valiente-Alandi I, Blaxall BC and Molkentin JD. Specialized fibroblast differentiated states underlie scar formation in the infarcted mouse heart. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:2127–2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLellan MA, Skelly DA, Dona MSI, Squiers GT, Farrugia GE, Gaynor TL, Cohen CD, Pandey R, Diep H, Vinh A, Rosenthal NA and Pinto AR. High-Resolution Transcriptomic Profiling of the Heart During Chronic Stress Reveals Cellular Drivers of Cardiac Fibrosis and Hypertrophy. Circulation. 2020;142:1448–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivey MJ, Kuwabara JT, Pai JT, Moore RE, Sun Z and Tallquist MD. Resident fibroblast expansion during cardiac growth and remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;114:161–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khalil H, Kanisicak O, Prasad V, Correll RN, Fu X, Schips T, Vagnozzi RJ, Liu R, Huynh T, Lee SJ, Karch J and Molkentin JD. Fibroblast-specific TGF-beta-Smad2/3 signaling underlies cardiac fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:3770–3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molkentin JD, Bugg D, Ghearing N, Dorn LE, Kim P, Sargent MA, Gunaje J, Otsu K and Davis J. Fibroblast-Specific Genetic Manipulation of p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase In Vivo Reveals Its Central Regulatory Role in Fibrosis. Circulation. 2017;136:549–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Small EM, Thatcher JE, Sutherland LB, Kinoshita H, Gerard RD, Richardson JA, Dimaio JM, Sadek H, Kuwahara K and Olson EN. Myocardin-related transcription factor-a controls myofibroblast activation and fibrosis in response to myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2010;107:294–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis J, Burr AR, Davis GF, Birnbaumer L and Molkentin JD. A TRPC6-dependent pathway for myofibroblast transdifferentiation and wound healing in vivo. Dev Cell. 2012;23:705–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexanian M, Przytycki PF, Micheletti R, Padmanabhan A, Ye L, Travers JG, Gonzalez-Teran B, Silva AC, Duan Q, Ranade SS, Felix F, Linares-Saldana R, Li L, Lee CY, Sadagopan N, Pelonero A, Huang Y, Andreoletti G, Jain R, McKinsey TA, Rosenfeld MG, Gifford CA, Pollard KS, Haldar SM and Srivastava D. A transcriptional switch governs fibroblast activation in heart disease. Nature. 2021;595:438–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams SM, Golden-Mason L, Ferguson BS, Schuetze KB, Cavasin MA, Demos-Davies K, Yeager ME, Stenmark KR and McKinsey TA. Class I HDACs regulate angiotensin II-dependent cardiac fibrosis via fibroblasts and circulating fibrocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;67:112–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuetze KB, Stratton MS, Blakeslee WW, Wempe MF, Wagner FF, Holson EB, Kuo YM, Andrews AJ, Gilbert TM, Hooker JM and McKinsey TA. Overlapping and Divergent Actions of Structurally Distinct Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors in Cardiac Fibroblasts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;361:140–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stratton MS, Bagchi RA, Felisbino MB, Hirsch RA, Smith HE, Riching AS, Enyart BY, Koch KA, Cavasin MA, Alexanian M, Song K, Qi J, Lemieux ME, Srivastava D, Lam MPY, Haldar SM, Lin CY and McKinsey TA. Dynamic Chromatin Targeting of BRD4 Stimulates Cardiac Fibroblast Activation. Circ Res. 2019;125:662–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis J, Salomonis N, Ghearing N, Lin SC, Kwong JQ, Mohan A, Swanson MS and Molkentin JD. MBNL1-mediated regulation of differentiation RNAs promotes myofibroblast transformation and the fibrotic response. Nature communications. 2015;6:10084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng Y and Pan D. The Hippo Signaling Pathway in Development and Disease. Dev Cell. 2019;50:264–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dasgupta I and McCollum D. Control of cellular responses to mechanical cues through YAP/TAZ regulation. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:17693–17706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, Enzo E, Giulitti S, Cordenonsi M, Zanconato F, Le Digabel J, Forcato M, Bicciato S, Elvassore N and Piccolo S. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature. 2011;474:179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mia MM, Cibi DM, Binte Abdul Ghani SA, Singh A, Tee N, Sivakumar V, Bogireddi H, Cook SA, Mao J and Singh MK. Loss of Yap/taz in cardiac fibroblasts attenuates adverse remodeling and improves cardiac function. Cardiovasc Res. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francisco J, Zhang Y, Jeong JI, Mizushima W, Ikeda S, Ivessa A, Oka S, Zhai P, Tallquist MD and Del Re DP. Blockade of Fibroblast YAP Attenuates Cardiac Fibrosis and Dysfunction Through MRTF-A Inhibition. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2020;5:931–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu F, Lagares D, Choi KM, Stopfer L, Marinkovic A, Vrbanac V, Probst CK, Hiemer SE, Sisson TH, Horowitz JC, Rosas IO, Fredenburgh LE, Feghali-Bostwick C, Varelas X, Tager AM and Tschumperlin DJ. Mechanosignaling through YAP and TAZ drives fibroblast activation and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308:L344–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mannaerts I, Leite SB, Verhulst S, Claerhout S, Eysackers N, Thoen LF, Hoorens A, Reynaert H, Halder G and van Grunsven LA. The Hippo pathway effector YAP controls mouse hepatic stellate cell activation. J Hepatol. 2015;63:679–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao Y, Hill MC, Li L, Deshmukh V, Martin TJ, Wang J and Martin JF. Hippo pathway deletion in adult resting cardiac fibroblasts initiates a cell state transition with spontaneous and self-sustaining fibrosis. Genes Dev. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This was the first study to directly modulate cardiac fibroblast Lats1/2 and Yap/Taz in the adult heart. Results demonstrated that endogenous Lats1/2 restrain Yap/Taz activity, myofibroblast differentiation, myocardial fibrosis, and pro-inflammatory signaling in uninjured hearts and in response to MI.

- 30.Kurotsu S, Sadahiro T, Fujita R, Tani H, Yamakawa H, Tamura F, Isomi M, Kojima H, Yamada Y, Abe Y, Murakata Y, Akiyama T, Muraoka N, Harada I, Suzuki T, Fukuda K and Ieda M. Soft Matrix Promotes Cardiac Reprogramming via Inhibition of YAP/TAZ and Suppression of Fibroblast Signatures. Stem Cell Reports. 2020;15:612–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang M, Yu M, Xia R, Song K, Wang J, Luo J, Chen G and Cheng J. Yap/Taz Deletion in Gli(+) Cell-Derived Myofibroblasts Attenuates Fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3278–3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heallen T, Zhang M, Wang J, Bonilla-Claudio M, Klysik E, Johnson RL and Martin JF. Hippo pathway inhibits Wnt signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science. 2011;332:458–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xin M, Kim Y, Sutherland LB, Qi X, McAnally J, Schwartz RJ, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R and Olson EN. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor signaling by Yap governs cardiomyocyte proliferation and embryonic heart size. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Gise A, Lin Z, Schlegelmilch K, Honor LB, Pan GM, Buck JN, Ma Q, Ishiwata T, Zhou B, Camargo FD and Pu WT. YAP1, the nuclear target of Hippo signaling, stimulates heart growth through cardiomyocyte proliferation but not hypertrophy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:2394–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Del Re DP, Matsuda T, Zhai P, Maejima Y, Jain MR, Liu T, Li H, Hsu CP and Sadoshima J. Mst1 promotes cardiac myocyte apoptosis through phosphorylation and inhibition of Bcl-xL. Mol Cell. 2014;54:639–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Del Re DP, Matsuda T, Zhai P, Gao S, Clark GJ, Van Der Weyden L and Sadoshima J. Proapoptotic Rassf1A/Mst1 signaling in cardiac fibroblasts is protective against pressure overload in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3555–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maejima Y, Kyoi S, Zhai P, Liu T, Li H, Ivessa A, Sciarretta S, Del Re DP, Zablocki DK, Hsu CP, Lim DS, Isobe M and Sadoshima J. Mst1 inhibits autophagy by promoting the interaction between Beclin1 and Bcl-2. Nat Med. 2013;19:1478–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsui Y, Nakano N, Shao D, Gao S, Luo W, Hong C, Zhai P, Holle E, Yu X, Yabuta N, Tao W, Wagner T, Nojima H and Sadoshima J. Lats2 Is a Negative Regulator of Myocyte Size in the Heart. Circ Res. 2008;103:1309–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leach JP, Heallen T, Zhang M, Rahmani M, Morikawa Y, Hill MC, Segura A, Willerson JT and Martin JF. Hippo pathway deficiency reverses systolic heart failure after infarction. Nature. 2017;550:260–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Prior work had shown that interventions that disrupt Hippo signaling prior to heart injury were protective. This study demonstrated that conditional deletion of cardiomyocyte Sav1 after MI-induced remodeling and heart failure had been established, was able to stimulate cardiomyocyte renewal and restore heart function through the activation of endogenous Yap.

- 40.Ikeda S, Mizushima W, Sciarretta S, Abdellatif M, Zhai P, Mukai R, Fefelova N, Oka SI, Nakamura M, Del Re DP, Farrance I, Park JY, Tian B, Xie LH, Kumar M, Hsu CP, Sadayappan S, Shimokawa H, Lim DS and Sadoshima J. Hippo Deficiency Leads to Cardiac Dysfunction Accompanied by Cardiomyocyte Dedifferentiation During Pressure Overload. Circ Res. 2019;124:292–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Del Re DP, Yang Y, Nakano N, Cho J, Zhai P, Yamamoto T, Zhang N, Yabuta N, Nojima H, Pan D and Sadoshima J. Yes-associated protein isoform 1 (Yap1) promotes cardiomyocyte survival and growth to protect against myocardial ischemic injury. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:3977–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xin M, Kim Y, Sutherland LB, Murakami M, Qi X, McAnally J, Porrello ER, Mahmoud AI, Tan W, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Sadek HA, Bassel-Duby R and Olson EN. Hippo pathway effector Yap promotes cardiac regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13839–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Byun J, Del Re DP, Zhai P, Ikeda S, Shirakabe A, Mizushima W, Miyamoto S, Brown JH and Sadoshima J. Yes-associated protein (YAP) mediates adaptive cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:3603–3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Porrello ER, Mahmoud AI, Simpson E, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Olson EN and Sadek HA. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science. 2011;331:1078–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu S, Tang L, Zhao X, Nguyen B, Heallen TR, Li M, Wang J, Wang J and Martin JF. Yap Promotes Noncanonical Wnt Signals From Cardiomyocytes for Heart Regeneration. Circ Res. 2021;129:782–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiao Y, Hill MC, Zhang M, Martin TJ, Morikawa Y, Wang S, Moise AR, Wythe JD and Martin JF. Hippo Signaling Plays an Essential Role in Cell State Transitions during Cardiac Fibroblast Development. Dev Cell. 2018;45:153–169 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bugg D, Bretherton R, Kim P, Olszewski E, Nagle A, Schumacher AE, Chu N, Gunaje J, DeForest CA, Stevens K, Kim DH and Davis J. Infarct Collagen Topography Regulates Fibroblast Fate via p38-Yes-Associated Protein Transcriptional Enhanced Associate Domain Signals. Circ Res. 2020;127:1306–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Francisco J, Zhang Y, Nakada Y, Jeong JI, Huang CY, Ivessa A, Oka S, Babu GJ and Del Re DP. AAV-mediated YAP expression in cardiac fibroblasts promotes inflammation and increases fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:10553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adamo L, Rocha-Resende C, Prabhu SD and Mann DL. Reappraising the role of inflammation in heart failure. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2020;17:269–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mia MM, Cibi DM, Abdul Ghani SAB, Song W, Tee N, Ghosh S, Mao J, Olson EN and Singh MK. YAP/TAZ deficiency reprograms macrophage phenotype and improves infarct healing and cardiac function after myocardial infarction. PLoS Biol. 2020;18:e3000941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Prior work had demonstrated a pro-inflammatory role for Yap/Taz in macrophages in culture and in non-cardiac systems. This paper demonstrated that myeloid specific deletion of Yap/Taz during MI conferred functional benefit to the heart through restorative macrophage polarization and resolution of wound healing, including attenuation of fibrosis and adverse cardiac remodeling.

- 51.Zhou X, Li W, Wang S, Zhang P, Wang Q, Xiao J, Zhang C, Zheng X, Xu X, Xue S, Hui L, Ji H, Wei B and Wang H. YAP Aggravates Inflammatory Bowel Disease by Regulating M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization and Gut Microbial Homeostasis. Cell reports. 2019;27:1176–1189 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu M, Yan M, Lv H, Wang B, Lv X, Zhang H, Xiang S, Du J, Liu T, Tian Y, Zhang X, Zhou F, Cheng T, Zhu Y, Jiang H, Cao Y and Ai D. Macrophage K63-Linked Ubiquitination of YAP Promotes Its Nuclear Localization and Exacerbates Atherosclerosis. Cell reports. 2020;32:107990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang D, Zhang Y, Xu X, Wu J, Peng Y, Li J, Luo R, Huang L, Liu L, Yu S, Zhang N, Lu B and Zhao K. YAP promotes the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome via blocking K27-linked polyubiquitination of NLRP3. Nature communications. 2021;12:2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Francisco J, Byun J, Zhang Y, Kalloo OB, Mizushima W, Oka S, Zhai P, Sadoshima J and Del Re DP. The tumor suppressor RASSF1A modulates inflammation and injury in the reperfused murine myocardium. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:13131–13144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramjee V, Li D, Manderfield LJ, Liu F, Engleka KA, Aghajanian H, Rodell CB, Lu W, Ho V, Wang T, Li L, Singh A, Cibi DM, Burdick JA, Singh MK, Jain R and Epstein JA. Epicardial YAP/TAZ orchestrate an immunosuppressive response following myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:899–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perestrelo AR, Silva AC, Oliver-De La Cruz J, Martino F, Horvath V, Caluori G, Polansky O, Vinarsky V, Azzato G, de Marco G, Zampachova V, Skladal P, Pagliari S, Rainer A, Pinto-do OP, Caravella A, Koci K, Nascimento DS and Forte G. Multiscale Analysis of Extracellular Matrix Remodeling in the Failing Heart. Circ Res. 2021;128:24–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]