Abstract

The causative agent of plague, Yersinia pestis, is regarded as being noninvasive for epithelial cells and lacks the major adhesins and invasins of its enteropathogenic relatives Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. However, there are studies indicating that Y. pestis invades and causes systemic infection from ingestive and aerogenic routes of infection. Accordingly, we developed a gentamicin protection assay and reexamined invasiveness of Y. pestis for HeLa cells. By optimizing this assay, we discovered that Y. pestis is highly invasive. Several factors, including the presence of fetal bovine serum, the configuration of the tissue culture plate, the temperature at which the bacteria are grown, and the presence of the plasminogen activator protease Pla-encoding plasmid pPCP1, were found to influence invasiveness strongly. Suboptimal combinations of these factors may have contributed to negative findings by previous studies attempting to demonstrate invasion by Y. pestis. Invasion of HeLa cells was strongly inhibited by cytochalasin D and modestly inhibited by colchicine, indicating strong and modest respective requirements for microfilaments and microtubules. We found no significant effect of the iron status of yersiniae or of the pigmentation locus on invasion and likewise no significant effect of the Yops regulon. However, an unidentified thermally induced property (possibly the Y. pestis-specific capsular protein Caf1) did inhibit invasiveness significantly, and the plasmid pPCP1, unique to Y. pestis, was essential for highly efficient invasion. pPCP1 encodes an invasion-promoting factor and not just an adhesin, because Y. pestis lacking this plasmid still adhered to HeLa cells. These studies have enlarged our picture of Y. pestis biology and revealed the importance of properties that are unique to Y. pestis.

The causative agent of plague, Yersinia pestis, is regarded as being unable to invade epithelial cells, because it does not express the established invasins of the enteropathogenic yersiniae (41, 58) and because three studies testing for invasion of HeLa cells failed to detect significant invasion by Y. pestis (26, 45, 47). However, a recent study of pneumonic plague in monkeys suggested that Y. pestis may invade the lung-associated lymphoid tissue and cause systemic disease (12). A study of mice and other rodents intragastrically inoculated with Y. pestis or infected via drinking water found rapid dissemination to liver and spleen and the development of fatal systemic disease without involvement of the lungs, enteric pathology, or excretion of yersiniae in feces (6). This suggests that there was negligible surface colonization and that invasion was highly efficient, leading to rapid systemic dissemination. When carnivores contract plague by eating infected animals (reference 46 and references therein), the yersiniae must invade to cause lethal systemic disease. In one study of oral infection of rats with Y. pestis, the necropsy findings were more consistent with tonsillar invasion than with infection by the gastric or pulmonary route (46). Hence, this study also suggested that Y. pestis is able to efficiently invade an epithelial layer over lymphoid tissue.

Virulence properties that might potentially affect invasiveness include the surface plasminogen activator protease Pla, which can activate plasminogen and promote adherence to components of basement membranes (36). The pH 6 antigen PsaA forms fibrils on the bacterial surface and has been shown to promote adherence and hemagglutination in the related enteropathogenic species Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (29, 61). At ambient temperature, the hemin storage hms genes of Y. pestis mediate the accretion of heme or Fe3+ in the outer membrane (37), creating a modified surface that might affect interactions of the bacteria with host cells. Y. pestis also responds to the iron status of the environment by altering expression of many genes encoding surface proteins, and these may potentially modulate bacterium-host cell interactions (30). The capsular protein Caf1 is antiphagocytic for phagocytes, especially polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) (8). The Yops regulon (low-Ca2+ response phenotype [Lcr+]), encoded by a 70-kb virulence plasmid, includes the expression and contact-dependent (type III) secretion of six protein toxins called Yops. Among the effects mediated by Yops is the inhibition of phagocytosis, including entry into epithelioid cells (10, 58). Of these Y. pestis properties, Pla and Caf1 are unique to Y. pestis and are encoded by virulence plasmids not present in the enteropathogenic yersiniae Y. pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia enterocolitica. The enteropathogenic yersiniae have versions of the other properties except for Hms, which is active only in some isolates of Y. pseudotuberculosis (21, 36, 58).

Y. pestis is a highly disseminative organism (see, e.g., reference 53) capable of surviving and replicating within nonactivated macrophages (56). However, like the enteropathogenic yersiniae, Y. pestis is thought to be predominantly extracellularly located during infection, due to the action of Yops (10) and Caf1 (see, e.g., references 8, 12, and 18). Y. pestis has lost by frameshift mutation or transposon insertion the major adhesins and invasins (Inv, Ail, and YadA) identified for the enteropathogenic yersiniae (41, 58). However, Y. pestis must have some adhesins in order for the contact-mediated delivery of Yops to occur (55), and Y. pestis does indeed adhere strongly to epithelial cells and deliver Yops into those cells (see, e.g., references 17 and 48). Y. pestis expresses PsaA (27, 29), but this fibril is not the major adhesin in Y. pseudotuberculosis and may not have a large adhesive role in Y. pestis (55, 61). The surface protease Pla recently has been found to act as an adhesin to extracellular matrix components, especially laminin, and to several cell lines (24, 25), and it appears to have lectin-like activity, with specificity for the globo series of glycolipids (24). It could be an important adhesin for Y. pestis.

In the present study, we reexamined the invasiveness of Y. pestis for epithelial cells and found that in fact Y. pestis is highly invasive. In the course of optimizing our assay conditions, we discovered several factors that likely contributed to the negative findings of the earlier studies that tested for invasiveness of Y. pestis. We characterized Y. pestis invasion for some bacterial and host cell requirements. One of our findings was a significant invasive role for a product of the Pla-encoding plasmid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were inoculated from storage onto agar slants or plates and kept at 4°C (for up to 1 week for Y. pestis on tryptose blood agar [Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.] and 2 weeks for Escherichia coli on Luria-Bertani agar [13]). E. coli DH5α was grown in Luria-Bertani broth or on Luria-Bertani agar at 37°C. For invasion experiments, growth of E. coli HB101 at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth or of Y. pestis and Y. enterocolitica at 26°C in heart infusion broth was initiated for ca. 6 h using a culture/flask ratio of up to 1:10 and shaking at 200 rpm. Cultures were diluted so as to maintain exponential growth for at least seven generations and a final optical density at 620 nm (OD620) not exceeding 2.0 (where an OD620 of 1.0 = 6 × 108 cells/ml). Heart infusion broth was supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract, 0.2% xylose, and 2.5 mM CaCl2 and adjusted to pH 6.0 or 8.0 in tests for the roles of pH and PsaA (pH 6 antigen) in invasion (27). The pH of the medium during growth of the yersiniae otherwise was in the range of 7 to 7.4. For invasion experiments where the iron status of yersiniae was modulated, Y. pestis was grown in the iron-deficient medium PMH (54) unsupplemented or supplemented with 10 μM iron as FeCl3 dissolved in 10 mM HCl or 50 μM hemin dissolved in 10 mM NaOH.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| HB101 | pro leu thi lacY hsdR endA recA rpsL20 ara-14 galK2 xyl-5 mtl-1 supE44 | 4 |

| DH5α | F−endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 (Nalr) relA1 Δ(lacIZYA-argF)U169 deoR[φ80dlacΔ(lacZ)M15] | GIBCO-BRL |

| Y. pestis medievalis biotypea | ||

| KIM5-3001 | Smr; Pgm−; pCD1 (Lcr+), pPCP1 (Pla+), pMT1 | 27 |

| KIM8-3002 | Smr; Pgm−; pCD1 (Lcr+), pPCP1− (Pla−), pMT1 | 33 |

| KIM6+ | Pgm+; pCD1− (Lcr−), pPCP1 (Pla+), pMT1 | R. R. Brubaker |

| KIM6 | Pgm−; pCD1− (Lcr−), pPCP1 (Pla+), pMT1; two versions used in this study were made by screening Y. pestis KIM5 (Pgm−; pCD1 [Lcr+], pPCP1 [Pla+], pMT1) for spontaneous loss of pCD1 and by screening Y. pestis KIM6+ for spontaneous Hms− colonies (having deleted the pgm locus [15]) | R. R. Brubaker |

| KIM10 | Pgm−; pCD1− (Lcr−), pPCP1− (Pla−), pMT1 | R. R. Brubaker |

| KIM5-3001.1 | Pgm−; psaA3:mTn3Cm (Psa−), pCD1 (Lcr+), pPCP1 (Pla+), pMT1 | 27 |

| KIM6-2008 | Kmr; hmsH-2008::mini-kan (Hms−); pCD1− (Lcr−), pPCP1, pMT1 | 34 |

| Orientalis biotype EV76b | Pgm−; pYV76 (Lcr+), pPCP2 (Pla+), pMT2 | R. R. Brubaker |

| Y. enterocoliticac | ||

| WA | O:8; pYVWA (Lcr+) | 7 |

| WA-LOX | O:8; pYVWA− (Lcr−) | 35 |

| Plasmid pTrc99A | Expression vector; Apr; ColE1 replicon; Ptrc promoter upstream of multiple cloning sequence | Pharmacia |

Native plasmids of Y. pestis KIM are the 70-kb pCD1 encoding the Ysc type III secretion-targeting apparatus and LcrV and Yops (Lcr+ phenotype) (38), the 9.6-kb pPCP1 encoding the surface protease Pla and the bacteriocin pesticin and its immunity protein (44, 50), and the 100-kb pMT1 encoding the capsular Caf1 protein and the “murine toxin” Ymt (28).

The single virulence plasmid in Y. enterocolitica WA confers the Lcr+ phenotype (35).

Invasion assay.

HeLa human epithelioid cells were grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 in 6-well cluster dishes containing 2 ml of medium per well or in 24-well cluster dishes with 1 ml of medium per well. The medium for most experiments was RPMI 1640 plus 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.). In several tests, Eagle's minimal essential medium (Life Technologies) plus 10% FBS was used. HeLa cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells per well for 6-well dishes and at 2 × 104 cells per well for 24-well dishes and incubated for 2 days to obtain ca. 80% confluent monolayers in 24-well dishes and approximately confluent monolayers in 6-well dishes. On the day of the experiment, cells in one well were detached with trypsin (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Mo.) and counted using a hemacytometer. The remaining wells were washed twice with warm medium lacking FBS and returned to 37°C plus 5% CO2, covered with medium, until infection. Bacteria were pelleted in a microcentrifuge, washed once with room temperature (RT) phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (135 mM NaCl, 2.68 mM KCl, 10 mM NaHPO4, 1.76 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.4]), and resuspended in PBS. They were diluted (based on their OD620 and the number of HeLa cells per well) into warm medium, the medium was removed from the HeLa cells, and 2 or 1 ml (for 6- or 24-well dishes, respectively) of bacterial suspension was added, giving a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. The infecting dose was verified by CFU determination. Infection was initiated by centrifugation at 200 × g for 5 min at RT. The dishes were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 5% CO2, at which time one set of triplicate wells received 7.5 μg (Y. pestis) or 20 μg (Y. enterocolitica or E. coli) of gentamicin (GM) per ml. At the time of GM addition, a second set of triplicate wells was harvested by cold-water lysis as follows. The medium was removed to a tube on ice, the cells were washed once with 1 ml of PBS/well, and the wash was added to the harvest tube. One milliliter or 0.5 ml of ice-cold water was added per well (for 6- or 24-well dishes, respectively), and the dish was set on ice for 10 min. The cells were then disrupted by vigorous pipetting across the well, and the lysate was added to the tube on ice and vortexed. The wells receiving GM treatment were incubated for 1 h, and then the medium was removed and discarded, the cells were washed once with 1 ml of RT PBS per well, and the wash was discarded. The cells were lysed as described above. Serial dilutions of the lysate (GM wells) or of the total well contents (no-GM wells) were made into PBS and plated in duplicate to determine the number of CFU per well (corresponding to total yersiniae for no-GM wells and intracellular yersiniae for GM wells). Percent invasion was determined as CFU of GM wells ÷ CFU of no-GM wells × 100%. Experiments were repeated at least once (and many were done at least in duplicate in both the 24-well and 6-well formats). In experiments testing for sensitivity of invasion to cytochalasin D or colchicine (Sigma), these drugs were present at 5 or 0.5 μg/ml (cytochalasin D) or at 10 or 5 μg/ml (colchicine) in the HeLa cell cultures for 30 min prior to infection and throughout the 1-h infection prior to GM treatment.

Microscopy.

For electron microscopy, duplicate wells of HeLa cells were infected for 1 h in six-well dishes (Falcon; Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lake, N.J.), washed once with 0.1 M Sorenson's phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) (23) to remove medium, and then fixed for 45 min on ice in 3.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Sorenson's buffer. The wells were then washed four times (5 min per change) with Sorenson's buffer, held overnight under Sorenson's buffer at 4°C, postfixed for 45 min at 4°C with 1% OsO4 in 0.1 M Sorenson's buffer, and washed two times with Sorenson's buffer. They were then dehydrated through a series of increasing ethanol concentrations from 50 to 100% (5 min per change) and infiltrated at RT for 6 to 8 h or overnight, uncovered, under a 60-W lamp with Eponate 12 (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, Calif.) resin mixture diluted 2:1 with 100% ethanol. Polymerization agents were dodecenyl succinic anhydride (Ernest F. Fullam, Inc., Latham, N.Y.), nadic methyl anhydride (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, Pa.), and tris-dimethylaminomethyl phenol (Fullam). The next day, the wells were infiltrated twice with Eponate 12 mixture (1 h per change), and then several Beem capsules containing Eponate were inverted onto each monolayer, and the blocks were polymerized for 36 to 48 h at 60°C. The blocks with their surface layer of HeLa cells were snapped off the dishes, and 60- to 80-nm sections were cut with a Reichert O'Lang Ultracut E microtome and collected on 300-mesh Thin Bar grids. Sections were poststained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and viewed with a Hitachi model 7000 transmission electron microscope, using an accelerating voltage of 75 kV.

RESULTS

Optimizing the assay.

Three previous studies tested for invasion of HeLa cells by Y. pestis and reached the conclusion that Y. pestis does not invade epithelial cells (26, 45, 47). We reexamined this question, because we felt that Y. pestis likely is invasive for epithelial cells, given its ability to cause systemic disease following ingestion and during pneumonic plague. We used a GM protection assay, in which yersiniae were centrifuged onto monolayers of HeLa cells seeded in cluster dishes and allowed 1 h to invade. To optimize the parameters of this system, we made a series of tests, always at least in duplicate experiments run on different days. The concentrations of GM (7.5 μg/ml for Y. pestis and 20 μg/ml for Y. enterocolitica WA) were determined so as to have a 104- to 105-fold kill after a 1-h treatment to yersiniae incubating in tissue culture medium in a cluster dish at 37°C and 5% CO2. This was tested for both Lcr+ and Lcr− strains for Y. enterocolitica and Y. pestis and for Pla+ and Pla− strains for Y. pestis. Two tissue culture media (RPMI 1640 and Eagle's minimal essential medium) gave similar percent invasion; RPMI was used in all other experiments. The presence of 5% FBS during the assay decreased invasion by 7.9- ± 4.0-fold (eight tests in four experiments). We omitted FBS in other experiments, because its relevance to epithelial invasion that might occur in vivo was not clear. MOIs of 10 and 50 gave the same percent invasion, so we used an MOI of 10 for other experiments, to lessen the possibility of receptor saturation on the eucaryotic cells. Yersiniae grown to stationary phase invaded as well as mid- and late-exponential-phase bacteria. The degree of confluency of HeLa cells (ca. 80% confluent versus essentially confluent) did not significantly affect invasion, so we used approximately confluent monolayers for a more meaningful MOI. Curiously, it made a difference if the cluster dish contained 6 or 24 wells (8.5- ± 2.0-fold greater invasion for 6-well dishes in two experiments directly comparing the two configurations and many experiments with only one or the other kind of plate). We do not fully understand this effect but think that it may relate in part to an edge effect on the monolayer (where the smaller wells would have a proportionately larger area dominated by the wall of the well). We used 6-well dishes for data subsequent to this discovery and confirmed conclusions from experiments done with the 24-well format at least once. In all such cases, confirmation has verified the same relative effects of the treatments under investigation.

General features of Y. pestis invasion.

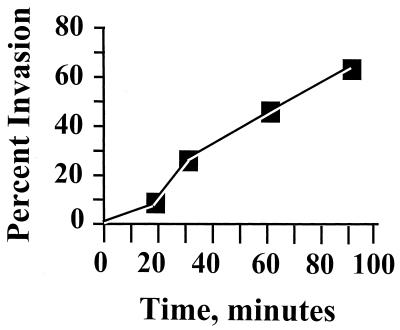

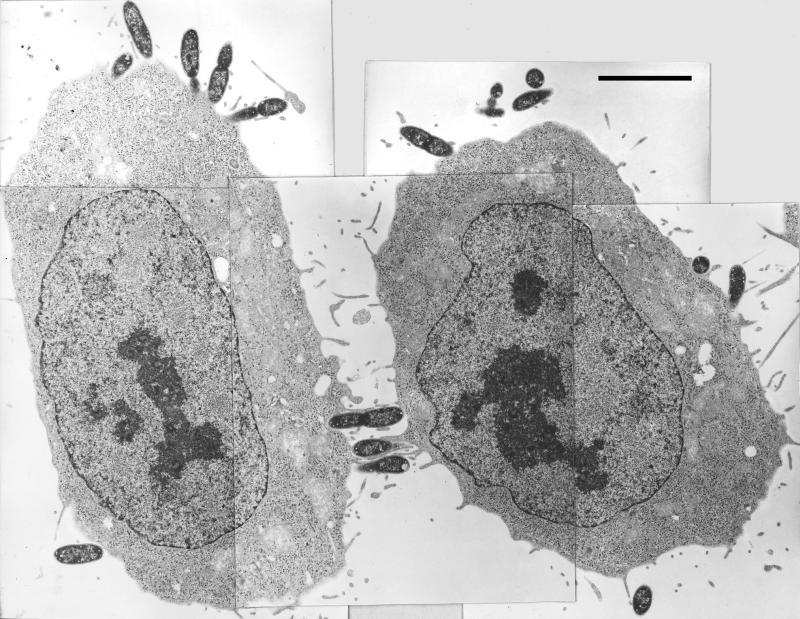

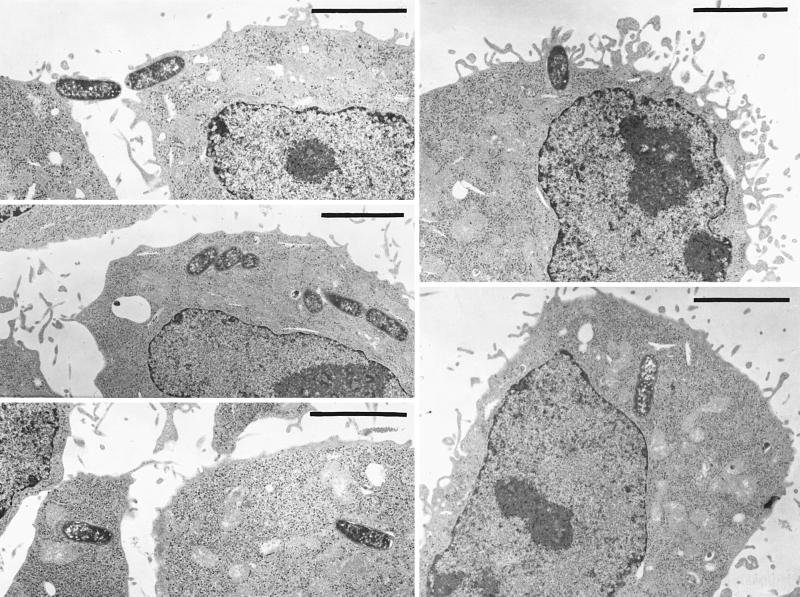

Figure 1 shows a typical time course for invasion of HeLa cells by Y. pestis, illustrating the maximal invasion efficiency that we have obtained. Invasion was rapid, with 30 to 50% invasion occurring after 60 min. The high invasion that we saw for Y. pestis actually did reflect an intracellular location of the bacteria and not any peculiar surface inaccessibility to GM, based on electron microscopy (right panel in Fig. 2) and confocal microscopy with a strain that constitutively expresses green fluorescent protein (C. Cowan and S. C. Straley, unpublished data). There was nothing unique about our strain of Y. pestis; the EV76 strain used by Rosqvist et al. (45) was as invasive as Y. pestis KIM. Likewise, there was nothing unique about our HeLa cells. We tested invasiveness for the human type I pneumocyte cell line WI-26 and found strong invasiveness: e.g., in one experiment using both HeLa and WI-26 cells, Lcr+ Y. pestis KIM5-3001 showed 65% invasion for WI-26 cells compared to 45% for HeLa cells; our Lcr− Y. pestis KIM6 strain showed 75% invasion for WI-26 cells and 61% for HeLa cells. The significance of the low-Ca2+ response will be addressed below. For comparison, we made a few tests with the wild-type O:8 Y. enterocolitica strain WA (7), a highly mouse-virulent strain not studied previously for its invasiveness. It was 5- to 10-fold less invasive than Y. pestis both in tests where the bacteria had been grown at 26°C and in ones where bacteria that had been grown at 26°C were incubated for 3 h at 37°C before infection of HeLa cells. E. coli HB101 was noninvasive (less than 0.01% invasion), as expected (49). Several tests found that invasion by Y. pestis was strongly inhibited by treatment of the HeLa cells with cytochalasin D. When the cytochalasin D concentration was 5 μg/ml, there was a toxic effect of the drug, manifested as a greatly diminished plating efficiency (however, this was seen only when undiluted harvested yersiniae were plated). In two tests with 0.5 μg of cytochalasin D per ml, there was no toxic effect, and the drug caused a 45- ± 28-fold inhibition of invasion. Similar treatment with colchicine (which had no toxic effect at either tested concentration) had a smaller but consistent inhibitory effect on invasion (5.4- ± 2.7-fold for 10 μg/ml, done in four tests in three experiments using 24-well plates; 4.1-fold in one test using 6-well dishes). These results indicate that Y. pestis invasion strongly depends upon actin cytoskeletal function but also may involve some participation of microtubules. Once within HeLa cells, the yersiniae reside within a tightly fitting membrane-bound compartment (Fig. 2, right panel, and higher-magnification micrographs not shown). We have not tested whether Y. pestis can grow within epithelioid cells.

FIG. 1.

Time course for invasion of HeLa cells by Y. pestis. Pla+ Pgm− Y. pestis KIM6 was grown at 26°C, washed, and used at an MOI of 10 to infect confluent HeLa cell monolayers in six-well cluster dishes. At various times, replicate infected cultures were analyzed for intracellular and total bacteria by the GM protection technique.

FIG. 2.

Typical electron microscopic images of Pla+ and Pla− Y. pestis interactions with HeLa cells at the time of harvest in a 60-min invasion assay. Prior to addition of the glutaraldehyde prefixative, the cultures for electron microscopy were handled exactly as in our optimized invasion assay. In parallel, replicate cultures were assayed for invasion by the GM protection assay. For the experiment depicted, the Pla+ Y. pestis showed 33% invasion, whereas the Pla− strain showed 3.2% invasion. (Left panel) Pla−. Five adjacent frames are combined into one montage. (Right panel) Pla+. Five nonadjacent frames are presented. Bars, 5 μm.

Iron status and invasion.

A previous study had found that surface coatings of iron or hemin on Hms+ Y. pestis did not enhance the total numbers of yersiniae that associated with HeLa cells (26) under conditions that did not promote invasion. However, with better control over invasion, we wanted to revisit this question, as it is relevant to early events following injection of the yersiniae into skin by fleabite. Accordingly, we made this test for the Pgm+ (Hms+) Lcr− Y. pestis KIM6+ strain grown at 26°C in the iron-deficient defined medium PMH unsupplemented or supplemented with 10 μM FeCl3 or 50 μM hemin. The data showed that the iron status of Y. pestis prior to infection of HeLa cells had no effect on invasion (Table 2). Accordingly, it is not essential that Y. pestis be coated with Fe or hemin for it to be highly invasive for epithelial cells, and the iron status of the bacteria does not appear to affect invasion.

TABLE 2.

Effect of treatment of bacteria or expression of virulence properties on invasion of HeLa cells by Y. pestisa

| Conditions | No. of exptb | Fold effectc (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Pgm+; hemin (50 μM) vs. none; 26°C | 6 | 0.96 ± 0.21 |

| Pgm+; Fe (10 μM) vs none; 26°C | 4 | 1.2 ± 0.34 |

| Pgm+ vs Pgm−; 26°C, Fe starved | 2 | 2.3 ± 1.2 |

| Pgm+ vs Pgm−; 26°C, +10 μM Fe | 2 | 1.8 ± 0.58 |

| Pgm+ vs Pgm−; 26°C, +50 μM hemin | 2 | 4.1 ± 2.6 |

| pCD1+ (Lcr+) vs pCD1−; growth at 26°C | 8 | 0.73 ± 0.46 |

| pCD1+ (Lcr+) vs pCD1−; 26°C growth, then 3 h at 37°C | 4 | 0.73 ± 0.19 |

| pCD1+ (Lcr+); 26°C growth, then 3 h at 37 vs 26°C | 2 | 0.32 ± 0.039 |

| pCD1−; 37 vs 26°C for ca. 7 generations | 2 | 0.057 ± 0.026 |

| PsaA+ vs PsaA−; pH 6, 37°C, 7 generations | 2 | 1.3 ± 0.20d |

| PsaA+ pCD1−; pH 6 vs pH 7, 37°C, 7 generations | 2 | 3.5 ± 1.0 |

| PsaA+ pCD1−; pH 8 vs pH 7, 37°C, 7 generations | 2 | 2.5 ± 0.53 |

| pPCP1+ vs pPCP1−; 26°C | 4 | 18 ± 8.1 |

Mid-exponential-phase bacteria were used for studies of the effect of iron status and of the Pgm+ locus on invasion; the other studies used late-exponential-phase yersiniae.

Experiments were done on different days.

Fold effect is percent invasion by yersiniae treated or expressing a virulence property divided by percent invasion by yersiniae lacking treatment or the virulence property (e.g., for hemin versus none, percent invasion for yersiniae grown in the presence of hemin divided by percent invasion for iron-starved yersiniae). Fold effects on invasion differing from 1.0 by more than two standard deviations or more than twice the half-range are indicated in boldface.

Done only in the 24-well configuration.

In addition to hms genes, the 102-kb Y. pestis pgm locus also contains two additional potentially virulence-related loci: genes encoding homologs of the BvgAS two-component regulatory system and a fimbrial-like gene cluster (5). As these might potentially affect invasion, we compared the invasiveness of the Pgm+ Lcr− strain Y. pestis KIM6+ to that of a spontaneous deletant derivative lacking the entire pgm region, KIM6 (16). These strains were grown at 26°C in defined medium unsupplemented or supplemented with Fe or hemin and were tested for invasiveness (Table 2). Loss of the pgm locus had little effect on invasiveness. No one has yet studied either the fimbrial locus or the BvgAS homologs for their regulation of expression and function, and we do not know if in fact they are functional at 26°C (our simulated flea temperature). However, we speculate that they would not have a large impact on the earliest interactions of Y. pestis with epithelial cells following introduction of Y. pestis into skin by fleabite.

Yops regulon and invasion.

We carried out a series of tests for the effect of expression of the Yops regulon on invasion, initially comparing Lcr+ Y. pestis having the plasmid pCD1 (which encodes the Yops regulon) and a pCD1− strain, grown at 26°C in heart infusion broth (to simulate yersiniae having just been injected into a mammal by fleabite) (Table 2). There was no significant effect of pCD1-encoded gene products on invasion. To test further for a role of the Yops regulon, we gave the yersiniae a 3-h thermal induction prior to infection (done in heart infusion broth, which we know is calcium deficient [42] and permits strong induction). This would simulate the condition of yersiniae after several hours following an infection via flea delivery or inhalation of an ambient-temperature aerosol. In some experiments there was less invasion by the Lcr+ strain, but in others there was no effect or a small opposite effect of the presence of pCD1 on invasion. These findings suggest that the Yops regulon has a relatively small antiphagocytic effect in Y. pestis.

Temperature and invasion.

In the tests for effects of the Yops regulon, the actual percent invasion was lower by about threefold when the yersiniae had been given the thermal induction compared to experiments on different days in which the bacteria had been grown only at 26°C. This clearly was independent of the presence of pCD1 and the Yops regulon, as it occurred with pCD1− as well as pCD1+ strains. To demonstrate this effect within the same experiment, we gave the pCD1+ strain a thermal induction and compared its invasion to that by the same strain incubated only at 26°C, and we found a ca. threefold inhibition of invasion due to thermal induction (Table 2). To eliminate any potential contribution to inhibition of invasion from the Yops regulon, we compared pCD1− yersiniae grown at 26 or 37°C for a longer induction period to allow any thermal effect to manifest itself strongly. In this case, there was a ca. 20-fold inhibition of invasion.

pH 6 antigen and pH.

We tested for a potential role for the pH 6 antigen PsaA in invasion. This surface fibril is expressed at 37°C and acidic pH (27) and also when Y. pestis is within macrophages and perhaps other acidic environments such as abscesses (29). However, this fibril apparently is not an invasin for Y. pestis, because PsaA− yersiniae with an insertional inactivation of psaA (Table 1) invaded as well as did the parent PsaA+ strain (Table 2) when the bacteria were grown so as to permit strong expression of pH 6 antigen. The pH at which PsaA+ yersiniae were grown at 37°C did not have a large effect on invasion (Table 2).

pPCP1 (Pla+) and invasion.

Presence of the plasmid pPCP1, which encodes the surface protease Pla, enhanced invasion of HeLa cells significantly (11- to 30-fold) (Table 2). Our assays did not distinguish adherence effects from invasion per se; however, pPCP1− (Pla−) Y. pestis did still adhere to HeLa cells, based on electron microscopy (Fig. 2) and on confocal microscopy of HeLa monolayers infected with pPCP1+ and pPCP1− Y. pestis expressing green fluorescent protein (Cowan and Straley, unpublished data). To assess only the adherence effect of Pla, we infected HeLa cells for 15 min with the Pla+ Y. pestis KIM6 or the Pla− Y. pestis KIM10 and determined the numbers of cell-associated yersiniae after washing the infected HeLa cells three times. In two tests, the Pla− strain showed 88% ± 1% of the number of cell-associated bacteria seen with the Pla+ Y. pestis (with absolute adherence values being 56 and 80% for Pla+ and 50 and 69% for Pla− in the respective tests).

DISCUSSION

In this study we have found that Y. pestis is in fact at least as invasive for epithelioid cells as the enteropathogenic yersiniae. We believe that the conditions we developed for the assay were critical for revealing high invasiveness. In the previous studies, several of the parameters we optimized and strain characteristics would have decreased invasion, with large cumulative effects. For example, in the study by Rosqvist et al. (45), invasion was tested in the presence of 5% FBS, and the Y. pestis strain used was Pla−. In the other two studies (26, 47), FBS was present, and the experimental configuration was different (24-well dishes or roller bottles). In addition, a significant effect in those studies could have come from the use of a 10-fold-higher concentration (75 μg/ml) of GM (26) or kanamycin (47). In the present study, we used the lowest concentration of GM that would give an adequate killing of extracellular bacteria in 1 h and did not explore this variable further.

Our preliminary tests for the cytochalasin D sensitivity of invasion indicated that invasion of HeLa cells by Y. pestis is mediated by actin microfilaments, as has been found previously for Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis (19, 32). However, we also found a modest inhibition of invasion by colchicine. This could indicate some microtubule involvement for uptake of Y. pestis, in contrast to uptake of Y. enterocolitica (19). This is intriguing and likely reflects the use of different eucaryotic receptors for binding and entry of Y. pestis, which does not express the invasin, YadA, and Ail adhesins that dominate invasion of the enteropathogenic yersiniae (41, 55).

The Y. pestis pgm locus potentially could have contributed to invasiveness in at least three ways. Binding of iron or hemin to the bacterial surface via hms-encoded proteins might influence bacterial uptake by epithelial cells, as in the case of Shigella (11). However, our experiments did not support this idea, in agreement with a previous study (26). Absence of the pgm locus altogether had no effect on Y. pestis invasiveness, indicating that at least under our experimental conditions, none of the other products of this 102-kb region has a significant invasive role. A pathogenicity island within the region encodes the siderophore-dependent yersiniabactin iron transport system (5, 20). However, neither deletion of the system nor the iron status of the bacterial cells affected invasion. This is in contrast to the case for Listeria monocytogenes, where an iron surplus enhanced transcription of inlAB and invasion of Caco-2 cells (9).

We were surprised to find no significant antiphagocytic effect of expression of the Yops regulon on invasion of HeLa or WI-26 cells. This could reflect in part that invasion by Y. pestis occurs through a mechanism that has some dependence on microtubules and not solely on actin microfilaments (at present, no effects of Yops on microtubules have been documented). However, even in Y. pseudotuberculosis, significant invasion has been reported to occur despite the functioning of the Yops regulon. As many as 25% of YadA− Y. pseudotuberculosis cells were intracellular in HeLa cells (39, 40) or J774 macrophage-like cells (1) when assayed only 30 min after initiation of infection by centrifugation. This is for yersiniae given a 1- to 2-h incubation at 37°C prior to infection to thermally induce expression of the Yops regulon (10). We agree with the opinion (2) that inhibition of phagocytosis (at least by epithelial cells) is not the major virulence outcome of the Yops regulon—rather, rapid immunosuppression to prevent effective cytokine expression and to cripple downstream killing mechanisms is the most potent virulence outcome of the Yops system.

Our experiments revealed a thermally induced property that decreases invasion efficiency independent of the expression of Yops. We speculate that this property is the capsular protein Caf1, which is expressed at 37 but not 26°C (57). Our findings mirrored the results of an old but excellent study, where Y. pestis grown below 28°C was phagocytosis sensitive for human monocytes and PMNs and expressed little capsule on its surface (8). After 3 h of incubation at 37°C, Y. pestis was resistant to phagocytosis by PMNs but not monocytes and expressed significantly more capsule. After overnight culture at 37°C, intracellular growth in monocytes, or growth for 3 to 5 h in mice, the yersiniae were strongly resistant to phagocytosis by both PMNs and monocytes and heavily encapsulated (8). In nature, yersiniae infecting via the fleaborne route would initially be highly sensitive to phagocytosis (this was shown in the laboratory for Y. pestis grown in fleas [8]), and the bacteria would find a safe niche within tissue macrophages and perhaps also epithelial cells, where they would gain phagocytosis resistance upon expression of thermally induced properties such as the capsule Caf1. Subsequently, they would be protected from phagocytosis and killing by PMNs through the action of the combination of Caf1 and Yops. In the situation of aerogenic or ingestive exposure to Y. pestis, the yersiniae would be coming directly from a 37°C environment and would likely be relatively phagocytosis resistant. However, our study has shown that Y. pestis retains some invasiveness for epithelial cells and macrophages even after growth at 37°C, as evidenced by 1 to 2% invasion in our 1-h experiments. At that efficiency, the actual numbers of Y. pestis that invade epithelial cells in pneumonic or ingestive plague still could amount to hundreds of lethal doses.

We tested two putative Y. pestis adhesins for their importance as invasins for epithelioid cells. The pH 6 antigen fibril did not contribute significantly to invasiveness. In contrast, we found that the presence of the Y. pestis-specific plasmid pPCP1 is responsible for 90 to 95% of the invasiveness by Y. pestis for HeLa cells. The 9.6-kb pPCP1 encodes the outer membrane serine protease Pla (22, 51) as well as a copy of IS100 (22), a bacteriocin (pesticin) that attacks peptidoglycan (via N-acetylmuramidase activity [59]), and the small pesticin immunity protein (22, 50). A pesticin mutant retains full virulence, whereas a mutant lacking Pla is avirulent (53, 60). Pla has been found by two research groups to have activity as an adhesin (24, 25). Consequently, Pla is the most likely pPCP1-encoded factor contributing to invasion. However, Pla is not the sole significant adhesin in Y. pestis, because Pla− Y. pestis still adhered to HeLa cells (Fig. 2). This indicates that there is an additional adhesin(s) in Y. pestis encoded by the chromosome or the 100-kb virulence plasmid. Pla had not been tested previously for its ability to sponsor invasion. Pla is expressed at 37°C as well as at 26°C (31) and elicits an antibody response in mice challenged aerogenically and then cured of infection by antibiotic treatment (3). It potentially could help promote invasion of 37°C-grown yersiniae such as those infecting from natural aerogenic and ingestive routes as well as yersiniae injected into skin by fleabite.

Pla is an outer membrane serine protease that is essential for virulence from the subcutaneous (but not intravenous) route of infection (53, 60). It is necessary for the intense disseminative character of Y. pestis and hence indirectly for infection of fleas (by ensuring a strong bacteremia) (53). Pla also has been proposed to contribute to a limited neutrophil response seen in mice infected subcutaneously (53); however, a different Pla+ strain of Y. pestis elicited a strong neutrophil response in a second study (60). It has not been determined how Pla specifically enhances dissemination through tissues, but Pla does activate plasminogen, which could prevent walling off of the bacteria in fibrin matrices. Alternatively, plasmin or Pla could have other substrates, degradation of which could promote dissemination in the body (53). Pla also degrades some Yops in vitro (52), but the relevance of this is unclear, as Yops are thought to be targeted directly into host cells and not to be accessible to degradation by Pla (and indeed, Pla+ and Pla− Y. pestis target Yops equally well [48]).

pPCP1 is unique to Y. pestis, and its mechanism for promoting invasion is not known. Future studies will be required to prove that Pla is the pPCP1-encoded invasin and, if so, to discover how it may induce engulfment by epithelioid cells. We do not know if the serine protease activity of Pla has any direct role, e.g., in unmasking surface ligands on the bacteria or receptors on the mammalian cells.

A practical consequence of our findings in this study applies to studies of Yop targeting and function. In such experiments it is important that the Yop-expressing bacteria all have a surface location, to avoid an erroneous conclusion that Yops within intracellular bacteria have been delivered by the pCD1-encoded type III secretion mechanism. Accordingly, we use pPCP1− Y. pestis in such experiments (see, e.g., references 17, 33, and 48), because pPCP1− strains still adhere to epithelioid cells and target Yops but themselves enter the cells poorly.

In summary, this study has been the first to demonstrate the ability of Y. pestis to invade epithelioid cells and to identify an invasion-promoting element that is unique to Y. pestis: the Pla-encoding plasmid pPCP1. These findings fill an important gap in our understanding of Y. pestis biology. It is likely that invasion is a critical step in ingestive plague in natural foci (6, 46) and perhaps also in the infection of lymphoid tissue and systemic dissemination that occur in pneumonic plague (12). We do not know if invasion by Y. pestis is restricted to epithelioid cells and macrophages (56). It will be important for future work to establish whether Y. pestis has an intracellular niche beyond the hypothesized residence within tissue macrophages early after delivery by fleabite (see, e.g., reference 57).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Jim Rizzo, Greta Fowler, and Pat Payne were involved in preliminary experiments to set up the invasion assays, and their contribution is appreciated. The Imaging Facility at the University of Kentucky and in particular the expert help of Mary Gail Engle and Richard Watson with electron microscopy are gratefully acknowledged.

S.C.S. and C.C. were supported by Public Health Service grant AI21017. R.D.P. and H.A.J. were supported by Public Health Service grants AI33481 and AI25098.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson K, Carballeira N, Magnusson K-E, Persson C, Stendahl O, Wolf-Watz H, Fallman M. YopH of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis interrupts early phosphotyrosine signalling associated with phagocytosis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1057–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson K, Magnusson K-E, Majeed M, Stendahl O, Fällman M. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis-induced calcium signaling in neutrophils is blocked by the virulence effector YopH. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2567–2574. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2567-2574.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benner G E, Andrews G P, Byrne W R, Strachan S D, Sample A K, Heath D G, Friedlander A M. Immune response to Yersinia outer proteins and other Yersinia pestis antigens after experimental plague infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1922–1928. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1922-1928.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolivar F, Backman K. Plasmids of Escherichia coli as cloning vectors. Methods Enzymol. 1979;68:245–267. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)68018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchreiser C, Rusniok C, Frangeul L, Couve E, Billault A, Kunst F, Carniel E, Glaser P. The 109-kilobase pgm locus of Yersinia pestis: sequence analysis and comparison of selected regions among different Yersinia pestis and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis strains. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4851–4861. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4851-4861.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler T, Fu Y, Furman L, Almeida C, Almeida A. Experimental Yersinia pestis infection in rodents after intragastric inoculation and ingestion of bacteria. Infect Immun. 1982;36:1160–1167. doi: 10.1128/iai.36.3.1160-1167.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter P B, Francis Varga C, Keet E E. New strain of Yersinia enterocolitica pathogenic for rodents. Appl Microbiol. 1973;26:1016–1018. doi: 10.1128/am.26.6.1016-1018.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavanaugh D C, Randall R. The role of multiplication of Pasteurella pestis in mononuclear phagocytes in the pathogenesis of flea-borne plague. J Immunol. 1959;84:348–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conte M P, Longhi C, Polidoro M, Petrone G, Buonfiglio V, Di Santo S, Papi E, Seganti L, Visca P, Valenti P. Iron availability affects entry of Listeria monocytogenes into the enterocytelike cell line Caco-2. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3925–3929. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3925-3929.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornelis G R, Boland A, Boyd A P, Geuijen C, Iriarte M, Neyt C, Sory M-P, Stainier S. The virulence plasmid of Yersinia, an antihost genome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1315–1352. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1315-1352.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daskaleros P A, Payne S M. Congo red binding phenotype is associated with hemin binding and increased infectivity of Shigella flexneri in the HeLa cell model. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1393–1398. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.6.1393-1398.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis K J, Fritz D L, Pitt M L, Welkos S L, Worsham P L, Friedlander A M. Pathology of experimental pneumonic plague produced by fraction 1-positive and fraction 1-negative Yersinia pestis in African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) Arch Path Lab Med. 1996;120:156–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis R H, Botstein D, Roth J R. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferber D M, Brubaker R R. Plasmids in Yersinia pestis. Infect Immun. 1981;31:839–841. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.2.839-841.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fetherston J D, Perry R D. The pigmentation locus of Yersinia pestis KIM6+ is flanked by an insertion sequence and includes the structural genes for pesticin sensitivity and HMWP2. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:697–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fetherston J D, Schuetze P, Perry R D. Loss of the pigmentation phenotype in Yersinia pestis is due to the spontaneous deletion of 102 kb of chromosomal DNA which is flanked by a repetitive element. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2693–2704. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fields K A, Straley S C. LcrV of Yersinia pestis enters infected eukaryotic cells by a virulence plasmid-independent mechanism. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4801–4813. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4801-4813.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finegold M J. Pneumonic plague in monkeys. Am J Pathol. 1969;54:167–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finlay B B, Falkow S. A comparison of microbial invasion strategies of Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia species. In: Horowitz M A, editor. Bacterial-host cell interaction. New York, N.Y: Alan R. Liss, Inc.; 1988. pp. 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gehring A M, DeMoll E, Fetherston J D, Mori I, Mayhew G F, Blattner F R, Walsh C T, Perry R D. Iron acquisition in plague: modular logic in enzymatic biogenesis of yersiniabactin by Yersinia pestis. Chem Biol. 1998;5:573–586. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinnebusch B J. Bubonic plague: a molecular genetic case history of the emergence of an infectious disease. J Mol Med. 1997;75:645–652. doi: 10.1007/s001090050148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu P, Elliott J, McCready P, Skowronski E, Garnes J, Kobayashi A, Brubaker R R, Garcia E. Structural organization of virulence-associated plasmids of Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5192–5202. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5192-5202.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyat M A. Fixation for electron microscopy. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kienle Z, Emody L, Svanborg C, O'Toole P W. Adhesive properties conferred by the plasminogen activator of Yersinia pestis. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1679–1687. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-8-1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lahteenmaki K, Virkola R, Saren A, Emody L, Korhonen T K. Expression of plasminogen activator Pla of Yersinia pestis enhances bacterial attachment to the mammalian extracellular matrix. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5755–5762. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5755-5762.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lillard J W, Jr, Bearden S W, Fetherston J D, Perry R D. The haemin storage (Hms+) phenotype of Yersinia pestis is not essential for the pathogenesis of bubonic plague in mammals. Microbiology. 1999;145:197–209. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-1-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindler L E, Klempner M S, Straley S C. Yersinia pestis pH 6 antigen: genetic, biochemical, and virulence characterization of a protein involved in the pathogenesis of bubonic plague. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2569–2577. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2569-2577.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindler L E, Plano G V, Burland V, Mayhew G F, Blattner F R. Complete DNA sequence and detailed analysis of the Yersinia pestis KIM5 plasmid encoding murine toxin and capsular antigen. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5731–5742. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5731-5742.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindler L E, Tall B. Yersinia pestis pH 6 antigen forms fimbriae and is induced by intracellular association with macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:311–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucier T S, Fetherston J D, Brubaker R R, Perry R D. Iron uptake and iron-repressible polypeptides in Yersinia pestis. Infect Immun. 1991;64:3023–3031. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3023-3031.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonough K A, Falkow S. A Yersinia pestis-specific DNA fragment encodes temperature-dependent coagulase and fibrinolysin-associated phenotypes. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:767–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller V L, Finlay B B, Falkow S. Factors essential for the penetration of mammalian cells by Yersinia. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1988;138:15–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nilles M L, Fields K A, Straley S C. The V antigen of Yersinia pestis regulates Yops vectorial targeting as well as Yops secretion through effects on YopB and LcrG. J Bacteriol. 1997;180:3410–3420. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3410-3420.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pendrak M L, Perry R D. Characterization of a hemin-storage locus of Yersinia pestis. Biol Metals. 1991;4:41–47. doi: 10.1007/BF01135556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perry R D, Brubaker R R. Vwa+ phenotype of Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect Immun. 1983;40:166–171. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.166-171.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perry R D, Fetherston J D. Yersinia pestis—etiologic agent of plague. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:35–66. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perry R D, Lucier T S, Sikkema D J, Brubaker R R. Storage reservoirs of hemin and inorganic iron in Yersinia pestis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:32–39. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.32-39.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perry R D, Straley S C, Fetherston J D, Rose D J, Gregor J, Blattner F R. DNA sequencing and analysis of the low-Ca2+-response plasmid pCD1 of Yersinia pestis KIM5. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4611–4623. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4611-4623.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Persson C, Carballeira N, Wolf-Watz H, Fallman M. YopH inhibits uptake of Yersinia, tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and FAK, and the associated accumulation of these proteins in peripheral focal adhesions. EMBO J. 1997;16:2307–2318. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Persson C, Nordfelth R, Andersson K, Forsberg A, Wolf-Watz H, Fallman M. Localization of the Yersinia PTPase to focal complexes is an important virulence mechanism. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:828–838. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pierson D E. Mechanisms of Yersinia entry into mammalian cells. In: Miller V L, Kaper J B, Portnoy D A, Isberg R R, editors. Molecular genetics of bacterial pathogenesis. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 235–247. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pollack C, Straley S C, Klempner M S. Probing the phagolysosomal environment of human macrophages with a Ca++-responsive operon fusion in Yersinia pestis. Nature. 1986;322:834–836. doi: 10.1038/322834a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Portnoy D A, Falkow S. Virulence-associated plasmids from Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:877–883. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.3.877-883.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Protsenko O A, Anisimov P I, Mosharov O T, Konnov N P, Popov Y A, Kokushkin A M. Detection and characterization of Yersinia pestis plasmids determining pesticin I, fraction I antigen, and “mouse” toxin synthesis. Sov Genet. 1983;19:838–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosqvist R, Forsberg A, Rimpilainen M, Bergman T, Wolf-Watz H. The cytotoxic protein YopE of Yersinia obstructs the primary host defence. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rust J H, Harrison D N, Marshall J D, Cavanaugh D C. Susceptibility of rodents to oral plague infection: a mechanism for the persistence of plague in inter-epidemic periods. J Wildlife Dis. 1972;8:127–133. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-8.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sikkema D J, Brubaker R R. Resistance to pesticin, storage of iron, and invasion of HeLa cells by yersiniae. Infect Immun. 1987;55:572–578. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.3.572-578.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skrzypek E, Cowan C, Straley S C. Targeting of the Yersinia pestis YopM protein into HeLa cells and intracellular trafficking to the nucleus. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:1051–1065. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Small P L, Isberg R R, Falkow S. Comparison of the ability of enteroinvasive Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, and Yersinia enterocolitica to enter and replicate within Hep-2 cells. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1674–1679. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.7.1674-1679.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sodeinde O A, Goguen J D. Genetic analysis of the 9.5-kilobase virulence plasmid of Yersinia pestis. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2743–2748. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.10.2743-2748.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sodeinde O A, Goguen J D. Nucleotide sequence of the plasminogen activator gene of Yersinia pestis: relationship to ompT of Escherichia coli and gene E of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1517–1523. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.5.1517-1523.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sodeinde O A, Sample A K, Brubaker R R, Goguen J D. Plasminogen activator/coagulase gene of Yersinia pestis is responsible for degradation of plasmid-encoded outer membrane proteins. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2749–2752. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.10.2749-2752.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sodeinde O A, Subrahmanyam Y V B K, Stark K, Quan T, Bao Y, Goguen J D. A surface protease and the invasive character of plague. Science. 1992;258:1004–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1439793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Staggs T M, Perry R D. Identification and cloning of a fur regulatory gene in Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:417–425. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.417-425.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Straley S C. Adhesins in Yersinia pestis. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1:285–286. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(93)90001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Straley S C, Harmon P A. Growth in mouse peritoneal macrophages of Yersinia pestis lacking established virulence determinants. Infect Immun. 1984;45:649–654. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.3.649-654.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Straley S C, Perry R D. Environmental modulation of gene expression and pathogenesis in Yersinia. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:310–317. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88960-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Straley S C, Starnbach M N. Yersinia: strategies that thwart immune defenses. In: Cunningham M W, Fujinami R S, editors. Effects of microbes on the immune system. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vollmer W, Pilsl H, Hantke K, Höltje J-V, Braun V. Pesticin displays muramidase activity. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1580–1583. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1580-1583.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Welkos S L, Friedlander A M, Davis K J. Studies on the role of plasminogen activator in systemic infection by virulent Yersinia pestis strain CO92. Microb Pathog. 1997;23:211–223. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang Y, Merriam J, Mueller J P, Isberg R R. The psa locus is responsible for thermoinducible binding of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis to cultured cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2483–2489. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2483-2489.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]