Abstract

The intracellularly acting protein toxin of Pasteurella multocida (PMT) causes numerous effects in cells, including activation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) signaling, Ca2+ mobilization, protein phosphorylation, morphological changes, and DNA synthesis. The direct intracellular target of PMT responsible for activation of the IP3 pathway is the Gq/11α-protein, which stimulates phospholipase C (PLC) β1. The relationship between PMT-mediated activation of the Gq/11-PLC-IP3 pathway and its ability to promote mitogenesis and cellular proliferation is not clear. PMT stimulation of p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase occurs upstream via Gq/11-dependent transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. We have further characterized the effects of PMT on the downstream mitogenic response and cell cycle progression in Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells. PMT treatment caused dramatic morphological changes in both cell lines. In Vero cells, limited multinucleation, nuclear fragmentation, and disruption of cytokinesis were also observed; however, a strong mitogenic response occurred only with Swiss 3T3 cells. Significantly, this mitogenic response was not sustained. Cell cycle analysis revealed that after the initial mitogenic response to PMT, both cell types subsequently arrested primarily in G1 and became unresponsive to further PMT treatment. In Swiss 3T3 cells, PMT induced up-regulation of c-Myc; cyclins D1, D2, D3, and E; p21; PCNA; and the Rb proteins, p107 and p130. In Vero cells, PMT failed to up-regulate PCNA and cyclins D3 and E. We also found that the initial PMT-mediated up-regulation of several of these signaling proteins was not sustained, supporting the subsequent cell cycle arrest. The consequences of PMT entry thus depend on the differential regulation of signaling pathways within different cell types.

The protein toxin from Pasteurella multocida (PMT) is the primary etiological agent of progressive atrophic rhinitis (11), and purified PMT experimentally induces all of the major symptoms of atrophic rhinitis in animals (2, 23). PMT appears to bind to and enter mammalian cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis (30, 33), although the details of this process are still unclear. In fibroblasts and osteoblasts, PMT acts intracellularly to enhance inositolphospholipid hydrolysis (25, 26), mobilize intracellular Ca2+ pools (40), increase protein phosphorylation (41), stimulate cytoskeletal changes such as stress fiber formation and focal adhesion assembly (5, 21), and initiate DNA synthesis (33). In contrast to the case for fibroblast cells, PMT exerts cytotoxic or cytopathic effects on Vero cells (2, 28), embryonic bovine lung cells (34), and canine osteosarcoma cells (30).

PMT exerts its effects on these cellular processes by acting on the free, monomeric α subunit of the Gq/11 family of heterotrimeric G-proteins (46), which stimulates phospholipase C (PLC) β1 to hydrolyze phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol. Accordingly, the release of these second messengers stimulates Ca2+ mobilization and activates protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation. Recent evidence demonstrated that PMT-mediated stimulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway occurs via Gq/11-dependent transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (38). G-protein-coupled receptors have been found to activate mitogenic signaling pathways and cellular proliferation by a number of diverse mechanisms (3, 13, 14, 18, 36), which are largely dependent upon cell type. Since PMT mediates its effects via regulation of the Gq/11 protein, the different effects observed for PMT on fibroblastic cells compared to other cell types might be due to differential modulation of Gq/11-dependent mitogenic signaling pathways in these cells.

In this study, we have compared PMT-mediated morphological changes, mitogenic signaling, and cell cycle progression in Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells under both confluent, quiescent conditions and subconfluent, proliferative conditions. The effect of recombinant PMT (rPMT) on cellular proliferation and cell cycle progression was characterized by cell numbers, DNA synthesis, and flow cytometry analysis. We also examined the effect of rPMT on the regulation of a number of key mitogenic signaling and cell cycle markers. Our results indicate that rPMT differentially modulates cellular responses in different cell types, resulting in different cellular consequences. In addition, in contrast to the long-lasting morphological changes, the initial mitogenic response to rPMT is not sustained, and further treatment with rPMT does not reinitiate mitogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

rPMT was cloned, expressed, and purified as previously described (45). African green monkey kidney (Vero) cells (CCL-81) and Swiss 3T3 murine fibroblast cells (CCL-92) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. [3H]-thymidine was obtained from Amersham Life Science. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated phalloidin, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), Triton X-100, and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG)–alkaline phosphatase conjugate (A3687) were purchased from Sigma. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to c-Myc (sc-764), cyclin D2 (sc-754), Rb/p107 (sc-318), and Rb/p130 (sc-317); mouse monoclonal antibodies to cyclin D1 (sc-8396), cyclin D3 (sc-6283), PCNA (sc-56), and p21 (sc-6246); goat polyclonal antibodies to cyclin E (sc-481-G) and β-actin (sc-1616); and rabbit anti-goat IgG–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (sc-2033), were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to p42/p44 MAPK (9102S), phospho-p42/p44 MAPK (9101S), p38 MAPK (9211S), and phospho-p38 MAPK (9211S), as well as goat anti-rabbit IgG–HRP conjugate (7071-1), were obtained from New England Biolabs. Goat anti-mouse IgG–HRP conjugate (170-6520) and goat anti-rabbit IgG–HRP conjugate (170-6518) were obtained from Bio-Rad. Tissue culture media, sera, antibiotics, and PCR primers and reagents were purchased from Gibco/BRL. All other reagents were of the highest quality commercially available.

Subconfluent cell culture assays.

Vero cells were maintained at 37°C and 10% carbon dioxide in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (pH 7.4) and containing 100 U of penicillin G per ml and 100 μg streptomycin per ml. Swiss 3T3 cells were maintained at 37°C and 10% carbon dioxide in DMEM supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated calf serum (CS) (pH 7.4) and containing 100 U of penicillin G per ml and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. Cells were plated onto 12-well plates (Falcon) at a density of 4 × 104 cells per well for Vero cells and at 2 × 104 cells per well for Swiss 3T3 cells. Prior to application, rPMT was added to the cell culture medium at a final concentration of 200 ng/ml and the toxin-containing medium was filter sterilized. Heat-inactivated toxin was prepared by heating rPMT at 70°C for 45 min and was similarly added to the medium at the same concentration as the active toxin. After 18 h, the medium containing no toxin, heat-inactivated toxin, or toxin was added to the cells. For each time point, cells were analyzed for cell number and [3H]thymidine incorporation and were visualized using phase-contrast microscopy for toxin-induced morphological changes with an Olympus IX-70 inverted microscope. Images of photomicrographs were obtained using a ScanJet 3C scanner (Hewlett-Packard) with DeskScan II (Hewlett-Packard) image acquisition software. The micrographs were produced using Adobe Photoshop 4.0.1 on a Macintosh G3 computer.

Confluent cell culture assays.

Vero and Swiss 3T3 cells were maintained as described above. Cells were plated onto 12-well plates (Falcon) at a density of 4 × 104 cells per well for Vero cells and at 2 × 104 cells per well for Swiss 3T3 cells. The cell culture medium was changed 1 day after plating. Vero cells were allowed to reach confluency 5 days after plating, and then the medium was changed to DMEM–1% FBS (pH 7.4) containing antibiotics. Swiss 3T3 cells were allowed to reach confluency 5 days after plating, and then the medium was changed to DMEM–1% CS (pH 7.4) containing antibiotics. Two days after quiescence with low-serum medium, medium containing no toxin, heat-inactivated rPMT, or rPMT, was added to the confluent cultures as described above. The culture medium was changed daily with DMEM–1% FBS (pH 7.4) containing antibiotics for the Vero cells and with DMEM–1% CS (pH 7.4) containing antibiotics for the Swiss 3T3 cells. For each time point, cells were analyzed for cell number and [3H]thymidine incorporation and were visualized for toxin-induced morphological changes using an Olympus IX-70 inverted microscope. Images and graphics were generated as described above.

Determination of [3H]thymidine incorporation.

In the subconfluent cell culture assays, at each time point, the cells were exposed to DMEM-Waymouth medium (1:1) (pH 7.4) containing [3H]thymidine (0.5 μCi/ml). After 2 h of exposure to this medium at 37°C and 10% CO2, the medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), trypsinized, and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS. The resuspended cells were centrifuged, the PBS was removed, and the cells were resuspended in 1 ml of cold 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and then centrifuged to collect the TCA-precipitable material. The TCA was removed, the cells were washed with 1 ml of cold 100% ethanol, and the pellets were solubilized in 1 ml of 0.1 M NaOH plus 2% Na2CO3. The amount of radiolabel incorporation was determined by adding 4 ml of ScintiVerse (Fisher) scintillation cocktail to 500 μl of the solubilized cell sample and counting on a Packard Tri-Carb 2300TR liquid scintillation analyzer. Data were plotted using Cricket Graph III (Computer Associates).

Determination of cell number.

In both the subconfluent and confluent cell culture assays, at each time point, the medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with PBS and trypsinized. The cells were then resuspended in 1 ml of PBS for subconfluent cells and in 2 ml of PBS for confluent cells. The resuspended cells were counted using a hemocytometer. For each experiment, cells in four samples were counted from each well to obtain the mean for each data point. Data were plotted as described above.

Fluorescence staining of rPMT-treated Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells.

Cells were plated at low density (2 × 104 cells/mL for Swiss 3T3 cells or 4 × 104 cells/ml for Vero cells) on glass chamber slides (Lab-Tek) in 2 ml of DMEM (pH 7.4) supplemented with antibiotics and 10% FBS for Vero cells or 10% CS for Swiss 3T3 cells. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 18 to 24 h to allow adherence to the matrix. The medium was changed and replaced with medium containing no toxin or rPMT at 200 ng/ml, and the cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C and 10% CO2. The cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 30 min, washed with PBS, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS, washed with PBS, incubated for 40 min at room temperature with FITC-conjugated phalloidin (50 μg/ml) (Sigma) and DAPI (2 μg/ml) (Sigma) in PBS, washed twice with PBS, and mounted in glycerol-PBS (3:1). The cells were visualized by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy using an Olympus IX-70 inverted microscope equipped with U-MWB and U-MWU fluorescence cubes for observing FITC and DAPI, respectively, and with a digital camera connected to a Power Macintosh 7600 computer. Images were captured with National Institutes of Health Image 1.61 image acquisition and analysis software. The micrographs were produced as described above.

Flow cytometry analysis.

Cells in six-well plates were treated as described above. At the specified times, the cells were washed with PBS and lysed in either 1 ml (for subconfluent cells) or 2 ml (for confluent cells) of hypotonic staining buffer (0.1% sodium citrate containing 0.3% Triton X-100, 0.1 mg of propidium iodide per ml, and 20 μg of RNase A per ml). The samples were kept in the dark at 4°C for no more than 1 h prior to analysis. The stained nuclei were analyzed using an EPICS-XL flow cytometer (Coulter). For each sample, data from at least 10,000 events were collected and analyzed using ModFit cell cycle analysis and modeling software (Verity). The data shown are representative of at least three separate experiments.

Preparation of Swiss 3T3 and Vero cell lysates.

Whole-cell lysates were prepared from cells treated with or without toxin under the indicated conditions and at the indicated times. Monolayers on six-well plates were washed with ice-cold PBS containing protease inhibitors (1 μg each of pepstatin A, leupeptin, and aprotinin per ml; 1 mM benzamidine, 0.25 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; 2 mM sodium vanadate; 50 mM sodium fluoride; and 2 mM EGTA), and cells were lysed in 100 μl (for Swiss 3T3 cells) or 400 μl (for Vero cells) of lysis buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8] containing 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10% glycerol, 50 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% bromophenol blue, and protease inhibitors). The cells were scraped from each well, and the contents were transferred into 1.5-ml centrifuge tubes. Each tube was heated at 100°C for 5 min and then immersed in a water bath sonicator for 5 min. Cellular proteins, approximately 20 μg of total protein per lane, were resolved via sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the protein bands were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for detection of protein expression levels by Western immunoblot analysis using appropriate primary antibodies, following by the appropriate HRP-conjugated anti-IgG secondary antibodies. Membranes were treated with chemiluminescence reagent according to the protocol of the manufacturer (New England Biolabs). Quantitation of scanned images of X-ray film exposed to the membranes was performed using National Institutes of Health Image 1.61, and graphics were generated as described above. After quantitation of phosphorylation of MAPK proteins using anti-phospho-p42/p44 MAPK antibodies, the membranes were stripped and reprobed using anti-p42/p44 MAPK antibodies to confirm equal loading of MAPK proteins. All immunoblots were also reprobed with anti-β-actin antibodies as control for protein loading.

Statistical analysis.

Data for thymidine incorporation and cell numbers are presented as the means and standard errors from replicate experiments, where N denotes the number of experiments performed for each data point and n denotes the number of replicate wells used. The significance of differences between control and rPMT-treated cells was analyzed by two-way analysis of variance with replication using the Microsoft Excel program and is presented as the P value between two series of measurements.

RESULTS

Effect of rPMT on confluent, quiescent cells.

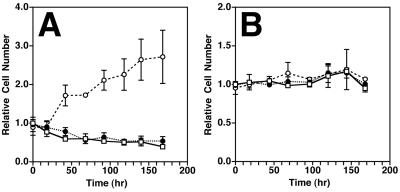

We have previously reported the effects of rPMT on confluent, quiescent monolayers of Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells (45). In those studies, we observed that rPMT-treated Swiss 3T3 cells did not form a monolayer characteristic of untreated fibroblasts and instead proliferated into a dense monolayer, which eventually formed foci or dense cell clusters. We also found in those earlier studies that confluent, quiescent Vero cells treated with rPMT rapidly underwent drastic morphological changes and developed foci. When we subsequently examined the effect of rPMT on cell numbers in these two cell lines, we found that the rPMT-induced increase in cell density of Swiss 3T3 monolayers was accompanied by a two- to threefold increase in cell number over the course of 6 to 7 days (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the dramatic morphological changes in Vero cells were not accompanied by changes in cell numbers (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Effects of rPMT on confluent, quiescent Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells. Time courses of relative cell numbers for confluent Swiss 3T3 cells (N = 3; n = 1, 1, and 1; P = 0.0005) (A) and Vero cells (N = 2; n = 1 and 1; P = 0.95) (B) are shown. Open squares, untreated controls; open circles, cells treated with rPMT; closed circles, cells treated with heat-inactivated rPMT.

Effect of rPMT on subconfluent, proliferating cells.

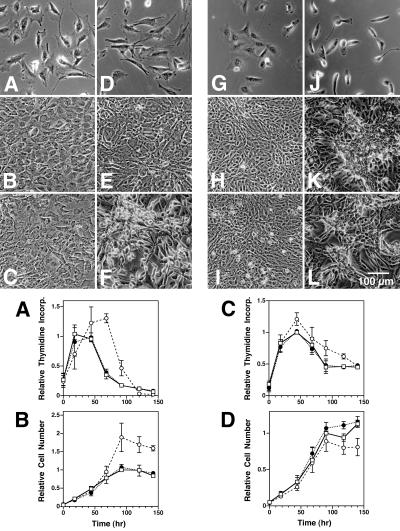

Since rPMT did not appear to have a significant effect on proliferation in confluent Vero cells, we next examined whether rPMT might influence the rate of proliferation in subconfluent cells under normal serum conditions. Subconfluent, proliferating cultures of Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells treated with rPMT underwent marked morphological changes within 1 day, as observed by phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 2, upper panels A, D, G, and J). The initial stages were characterized by rounding up of individual cells and cytoplasmic retraction. Once the cells began to reach confluence, the Vero cell monolayer developed foci or patches of dense cell clusters surrounded by enlarged cells (Fig. 2K). This uneven distribution of the monolayer progressed (Fig. 2L) and eventually (after 6 to 7 days) resulted in rolling up and detachment of the monolayer as rolled sheets from the matrix (data not shown). This phenomenon is consistent with the reported “cytopathic” or “cytotoxic” effect of PMT on Vero cells (2, 28), although these detached cells remained viable by trypan blue dye exclusion assay (data not shown). For earlier time points, detached cells were included in the cell counts.

FIG. 2.

Effects of rPMT on subconfluent, proliferating Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells. (Top panels) Representative phase-contrast micrographs of confluent Swiss 3T3 cells treated without (A to C) or with (D to F) rPMT for 18 h (A and D), 96 h (B and E), and 144 h (C and F) and of Vero cells treated without (G to I) or with (J to L) rPMT for 18 h (G and J), 96 h (H and K), and 144 h (I and L) under conditions as described in Materials and Methods. (Bottom panels) Time courses of relative rate of [3H]thymidine incorporation into DNA for subconfluent Swiss 3T3 cells (N = 3; n = 2, 2, and 2; and P = 0.004) (A) and Vero cells (N = 3; n = 1, 2, and 2; and P = 0.45) (C) and relative cell numbers for Swiss 3T3 cells (N = 2; n = 1 and 1; and P = 0.007) (B) and Vero cells (N = 3; n = 1, 1, and 1; and P = 0.63) (D). Open squares, untreated controls; open circles, cells treated with rPMT; closed circles, cells treated with heat-inactivated rPMT.

The rPMT-treated Swiss 3T3 cells first reached confluence in an apparently normal manner and then formed a dense monolayer (Fig. 2E). The dense monolayer subsequently developed foci and exhibited a transformed phenotype with loss of adherence of the cells to the matrix (Fig. 2F), but the monolayer did not detach in sheets from the matrix as was observed in the case of the Vero cells. Again, the detached cells remained viable as assayed by trypan blue dye exclusion (data not shown). For earlier time points, detached cells were included in the cell counts.

rPMT prolonged DNA synthesis in subconfluent Swiss 3T3 cells and caused them to reach a higher density at confluence than untreated cells, as evidenced by the rate of tritiated thymidine incorporation into DNA (Fig. 2, lower panel A) and cell numbers (Fig. 2, lower panel B). Interestingly, there was a decrease in both the rate of DNA synthesis and cell numbers observed at later time points after day 3, indicating that the initial increased mitogenic and proliferative activity was not sustained. Similarly, there was a decrease in the rate of tritiated thymidine incorporation in control and rPMT-treated Vero cells after day 3 (Fig. 2, lower panel C), but unlike the case for Swiss 3T3 cells, no significant differences in tritiated thymidine incorporation (Fig. 2, lower panel C) or overall cell numbers (Fig. 2, lower panel D) were observed between rPMT-treated cells and controls. This lack of rPMT-induced mitogenic response in Vero cells is in contrast to the pronounced morphological effect observed throughout the time course of the experiment.

Effect of rPMT on cell cytoskeletal organization.

Fluorescence staining of actin was performed to visualize the effect of rPMT on the organization of actin microfilaments in subconfluent, proliferating Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells. In the untreated Swiss 3T3 cells, actin staining was primarily diffused around the perinuclear region and throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 3A). Since the cells were proliferating, actin fibers were visible to some extent in many cells, particularly in those that were in the process of dividing. In rPMT-treated Swiss 3T3 cells, prominent actin fibers were visible throughout the cytoplasm in most of the cells after 2 h of exposure (Fig. 3B to D). Strong staining of stress fibers was not observed to any significant extent at 30 min but began to appear at 1 h and persisted for more than 24 h (not shown). These findings are consistent with previous reports on PMT-treated Swiss 3T3 cells (21, 33).

FIG. 3.

Effects of rPMT on actin cytoskeletal organization and nucleation of Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells. Shown are representative phase-contrast, FITC-conjugated-phalloidin-stained fluorescence micrographs and DAPI-stained fluorescence micrographs of Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells treated with rPMT (200 ng/ml) under subconfluent, proliferative conditions as described in Materials and Methods. (A to D) Swiss 3T3 cells; (E to H) Vero cells; (A and E) controls without rPMT treatment; (B to D and F to H) cells treated with rPMT for 2 h. Within each panel phase-contrast (top), FITC-phalloidin-stained (middle), and DAPI-stained (bottom) micrographs are shown. Arrows indicate multinucleation or nuclear fragmentation.

Vero cells treated with rPMT did not exhibit the prominent stress fibers as observed in Swiss 3T3 cells, but some cells showed evidence of disruption of cytoskeletal organization by 2 h of toxin exposure (Fig. 3E to H). We observed a limited amount of bi- and multinucleation (Fig. 3F to H), nuclear fragmentation (Fig. 3G), and disruption of cytokinesis (Fig. 3H, right panel), which has not previously been reported. These aberrant cells, making up about 10% of the total at 2 h, were rarely observed after longer treatment with toxin (not shown). By 18 h none were observed, and instead most appeared rounded and less adherent to the matrix by that point (Fig. 2J).

Effect of rPMT on cell cycle progression.

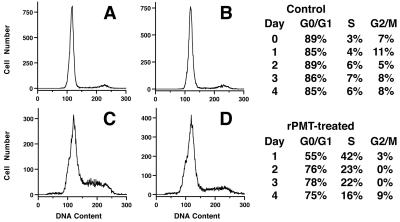

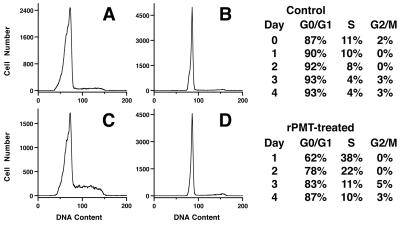

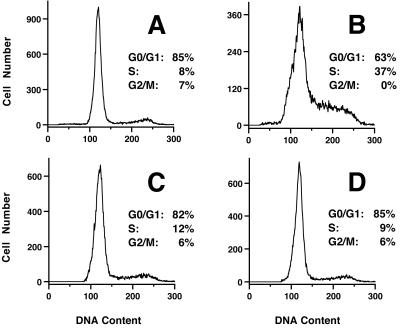

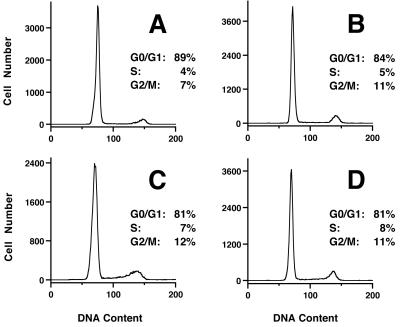

To determine if rPMT could initiate cell cycle progression in Vero cells similar to that seen with Swiss 3T3 cells, we compared the effects of rPMT on cell cycle progression in Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells using flow cytometry. Confluent, quiescent Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells, in the presence of 1% serum (Figs. 4 and 5) or 5% serum (data not shown), were found predominantly in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle, with 85 to 90% in G0/G1 for Swiss 3T3 cells (Fig. 4A and B) and 90 to 95% for Vero cells (Fig. 5A and B). After 1 day of toxin exposure, both Swiss and Vero cells were induced by rPMT treatment to progress through the cell cycle, with 40 to 45% of the cells (Fig. 4C and 5C, respectively) found in S phase. However, after 3 to 4 days, most of the cells were again found in G0/G1 (Figs. 4D and 5D), with the percentage returning to near the levels of controls by day 5. Under subconfluent conditions, there was no significant difference observed between controls and toxin-treated cells in the percentage of cells progressing through the cell cycle, with both treated and untreated Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells eventually arresting in G0/G1 by day 6 to 7 (data not shown). These results suggest that while there is a clear mitogenic response to rPMT in both cells, exposure to rPMT for 1 day does not allow for sustained cell cycle progression in either of these cell types, with both cell types subsequently arresting predominantly in G0/G1.

FIG. 4.

Effect of rPMT on cell cycle progression in confluent Swiss 3T3 cells. (Left) Representative DNA histograms from time courses of untreated (A and B) or rPMT-treated (C and D) confluent Swiss 3T3 cells from day 1 (A and C) and day 4 (B and D). (Right) Summary of the percentages of control (top) or rPMT-treated (bottom) cells found in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle during the time course, determined as described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 5.

Effect of rPMT on cell cycle progression in confluent Vero cells. (Left) Representative DNA histograms from time courses of untreated (A and B) or rPMT-treated (C and D) confluent Vero cells from day 1 (A and C) and day 4 (B and D). (Right) Summary of the percentages of control (top) or rPMT-treated (bottom) cells found in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle, determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Effect of rPMT on mitogenic signaling and cell cycle proteins.

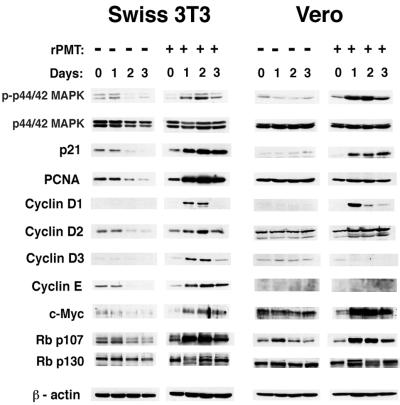

To determine at what point in the cell cycle rPMT exerts its effects, we assessed the effect of rPMT on the expression of a number of cell cycle markers involved in progression from G0 through G1 and into S phase. These markers included the MAPKs, the D and E cyclins, p21, PCNA, c-Myc, and the Rb proteins (p107 and p130). The levels of these proteins and their phosphorylation states have been shown to vary as cells progress through the cell cycle (19, 31, 39, 43).

As confluent Swiss 3T3 cells reached quiescence over the course of 3 days, the expression levels of the D and E cyclins, p21, PCNA, c-Myc, and Rb/p107 declined to undetectable levels (Fig. 6, left panels). During this time, the phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK also decreased, and the Rb/p130 protein was present in a hypophosphorylated state. These results are consistent with previous reports for the behavior of these proteins in normal, quiescent fibroblastic cells. Treatment with rPMT resulted in a pronounced up-regulation in the expression levels of the cyclins D1, D2, D3, and E, p21, PCNA, c-Myc, and Rb/p107 and increased protein phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK and Rb/p130, which was sustained through day 2. However, by day 3 the protein expression levels of cyclin D3 were markedly reduced and cyclin D1 levels were undetectable. Expression levels of PCNA, cyclins D2 and E, and Rb/p107, while continuing to remain relatively high, began to decline slightly by day 3. Only c-Myc and p21 protein levels remained high. Phosphorylation levels of p42/p44 MAPK also declined by day 3, but the hyperphosphorylated state of Rb/p130 continued.

FIG. 6.

Effect of rPMT on expression profiles of mitogenic signaling and cell cycle markers. Shown are representative Western blots of cell lysates from time courses of untreated or rPMT-treated confluent Swiss 3T3 (left panels) and Vero (right panels) cells, prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Antibodies against signaling and cell cycle proteins that were used for immunoblotting are indicated to the left. Approximately 20 μg of total protein was used per lane. Antibodies against β-actin were used as an internal control for protein content.

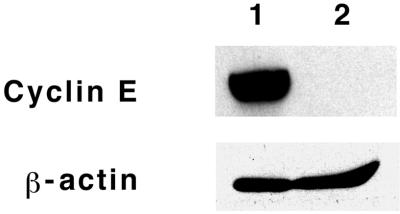

In Vero cells, a somewhat different expression pattern was observed (Fig. 6, right panels). No detectable expression of cyclin D1 or E was observed in confluent, quiescent Vero cells. Cyclins D2 and D3, p21, PCNA, and c-Myc were all expressed at a low, constitutive level in these cells. rPMT treatment caused a sustained up-regulation of cyclin D2, p21, Rb/p107, and particularly c-Myc. rPMT also caused a transient up-regulation of the expression of cyclin D1 by day 1, which declined again by day 2. However, unlike the case for cyclin D1, rPMT had no effect on the expression of cyclin E in confluent Vero cells. When we compared the expression of cyclin E in subconfluent, proliferating cells with its expression in confluent, quiescent Vero cells, we found that cyclin E was expressed only prior to confluence (Fig. 7). Thus, the results suggest that rPMT treatment was not sufficient to up-regulate cyclin E expression in confluent Vero cells. rPMT treatment also had no effect on the expression levels of PCNA. Interestingly, rPMT treatment caused a down-regulation in cyclin D3 expression to undetectable levels by day 1. Phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK was increased by rPMT treatment during days 1 and 2 but declined again by day 3. Rb/p130, on the other hand, was hyperphosphorylated in response to rPMT and remained so through day 3.

FIG. 7.

Cyclin E expression in Vero cells. Shown is a representative Western blot indicating cyclin E expression levels in cell lysates from subconfluent, proliferating (lane 1) and confluent, quiescent (lane 2) Vero cells, prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Approximately 20 μg of total protein were used per lane. Antibodies against β-actin were used as an internal control for protein content.

Effect of multiple treatments with rPMT on cell cycle progression.

To determine if rPMT could restimulate the cells to initiate cell cycle progression, we examined the effect of additional treatment with rPMT on day 5 after the first exposure in confluent Swiss 3T3 cells (Fig. 8) and Vero cells (Fig. 9). After 5 days under confluent, low-serum conditions, Swiss 3T3 cells responded dramatically to rPMT treatment (compare Fig. 8A and B). In contrast, under similar conditions, Vero cells showed little or no cell cycle progression (compare Fig. 9A and B), despite pronounced morphological changes. In both cell lines, treatment with rPMT at day 0 resulted in cell cycle reentry, with subsequent arrest predominantly at G0/G1 by day 5 (Fig. 8C and 9C). A second addition of rPMT had no effect on the percentage of cells in G0/G1 or S and G2/M phases (Figs. 8D and 9D), indicating that after the first treatment, subsequent treatments with rPMT failed to stimulate cell cycle progression.

FIG. 8.

Effect of multiple rPMT treatments on Swiss 3T3 cell cycle progression. Shown are representative DNA histograms of confluent Swiss 3T3 cells, indicating the effect of multiple rPMT treatments. (A) Untreated control cells analyzed on day 5. (B) Cells treated with rPMT on day 5 and analyzed on day 6. (C) Cells treated with rPMT on day 0 and analyzed on day 5. (D) Cells treated with rPMT on day 0 and again on day 5 and analyzed on day 6. The percentages of cells found in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle, determined as described in Materials and Methods, are also shown.

FIG. 9.

Effect of multiple rPMT treatments on Vero cell cycle progression. Shown are representative DNA histograms of confluent Vero cells, indicating the effect of multiple rPMT treatments. (A) Untreated control cells analyzed on day 5. (B) Cells treated with rPMT on day 5 and analyzed on day 6. (C) Cells treated with rPMT on day 0 and analyzed on day 5. (D) Cells treated with rPMT on day 0 and again on day 5 and analyzed on day 6. The percentages of cells found in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle, determined as described in Materials and Methods, are also shown.

DISCUSSION

rPMT is known to induce cellular proliferation in confluent, quiescent fibroblastic cells and markedly increases the total amount of tritiated thymidine incorporation into DNA over a period of 40 h (33). rPMT also induces striking changes in the morphology of other cells, including confluent Vero cells and embryonic bovine lung cells, which has been reported as a “cytotoxic” or “cytopathic” effect (2, 28, 34). rPMT has also been reported to induce anchorage-independent cell growth of fibroblasts (16), as evidenced by colony formation in soft agar, suggesting that rPMT has the ability to promote a transformed phenotype. Consistent with these reports, we found that confluent, quiescent Swiss 3T3 cells treated with rPMT formed dense monolayers, concomitant with an overall two- to threefold increase in cell number over a period of 4 to 6 days. More convincingly, we found that subconfluent, proliferating Swiss 3T3 cells treated with rPMT first formed a confluent monolayer but then underwent drastic morphological changes, along with enhanced DNA synthesis, increased cell numbers, rounding up, and decreased adherence. Interestingly, the rPMT-induced increase in the rate of DNA synthesis, while prolonged over that of untreated cells, was not sustained and declined after day 3. Likewise, while the overall cell numbers were doubled over those of untreated cells, there was no further increase in cell numbers after day 4. Detachment from the cell matrix did not account for this lack of increase in cell numbers, since detached cells remained viable and were included in the counting.

Consistent with earlier reports on Swiss 3T3 cells (5, 21), rPMT caused rearrangement of the more diffuse actin cytoskeleton into numerous, prominent stress fibers, which were significant by 2 h of toxin exposure. These stress fibers were rarely seen at 30 min but were first evident by 1 h and persisted for more than 24 h. We also observed a limited amount (1 to 2%) of bi- and multinucleation in the Swiss 3T3 cells. This effect has not been previously reported by others and is most likely due to the proliferative conditions under which we conducted our experiments, since the other investigators had used exclusively quiescent cells in their studies (5, 21).

Vero cells underwent dramatic morphological changes in response to rPMT treatment under confluent, quiescent conditions, as well as under subconfluent, proliferative conditions. The morphological response to toxin was much more rapid and pronounced under both conditions for Vero cells than for Swiss 3T3 cells. We observed no evidence of cytotoxicity or cell death under our conditions, although the observed morphological effects are consistent with the “cytotoxic” effects described in earlier reports of the changes observed for toxin-treated confluent, quiescent Vero cells (2, 28, 34). However, rPMT had no apparent effect on mitogenesis or proliferation in Vero cells, as evidenced by the lack of a significant increase in thymidine incorporation into DNA or cell numbers, compared to untreated cells. Cell cycle analysis indicated that a portion of the Vero cells could be stimulated to enter G1 and S phases with up to 10% of the cells undergoing multinucleation or DNA fragmentation, but this response was not sustained, and most cells subsequently arrested in G1.

Proliferating Vero cells treated with rPMT showed significant cytoskeletal rearrangement but did not form prominent stress fibers similar to those of Swiss 3T3 cells. Instead, at early times within 1 to 2 h of toxin exposure, a portion of the cells appeared to be bi- and multinucleated, while others had evidence of interference with cytokinesis, as well as nuclear fragmentation. The Vero cells appeared to have a greater tendency to form bi- or multinuclear and nuclear-fragmented cells than the Swiss 3T3 cells, with the incidence being about 10% of the cell population. The aberrant Vero cells became less evident at later times, probably due to subsequent cell death, and were no longer present at 18 h; instead, by that time most of the cells appeared viable but more rounded.

The cellular effects we observed for rPMT are similar to those observed for two other related toxins, the cytotoxic necrotizing factors (CNF1 and CNF2) of Escherichia coli (6, 27) and the dermonecrotic toxin (DNT) of Bordetella species (32, 44). Although there is no significant sequence similarity between PMT and DNT, PMT does share about 30% homology in the N-terminal 500 amino acids with the CNFs (6, 24, 27), and there is a 100-amino-acid region of significant homology between the CNFs and DNT near their C termini (44). All of these toxins have a mitogenic effect (increased DNA synthesis) on quiescent cells. rPMT has both a mitogenic effect and a proliferative effect (reference 33 and this study), whereas DNT and the CNFs cause primarily bi- and multinucleation (17, 22, 27, 32). We have now shown that rPMT is also capable of eliciting bi- and multinucleation in cells that are proliferating (up to ∼10%), albeit to a lesser extent than DNT and the CNFs, which can induce multinucleation in up to 90% of the cells by 2 to 3 days (7, 35).

Like PMT, DNT and the CNFs also induce actin stress fiber formation (8, 17, 22). The known target proteins modified by DNT and the CNFs are the Rho GTPases (9, 10, 17, 35), which are involved in regulating the actin cytoskeleton, the assembly of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions, cell motility, and cytokinesis. Whether PMT is also able to directly modify the Rho proteins is unclear, but we have not been able to demonstrate a similar rPMT-mediated deamidase modification of Rho as that reported for DNT and the CNFs (B. A. Wilson and Q. Yin, unpublished results). On the other hand, we have shown that the primary intracellular target of rPMT that activates the PLC-IP3 pathway is the Gqα protein (38, 46). Unlike PMT, DNT and the CNFs do not activate the IP3 pathway in Swiss 3T3 cells (22). This suggests that DNT and the CNFs do not act on the Gq protein or PLC and that the mechanism by which PMT mediates mitogenesis and cytoskeletal rearrangement in cells is different from that of the other toxins.

Our results suggest that rPMT has a greater effect on the cytoskeletal organization in Vero cells than in Swiss 3T3 cells but has a greater initial effect on DNA synthesis in Swiss 3T3 cells than in Vero cells. Cell cycle analysis indicated that PMT treatment induced both cell types to reinitiate cell cycle progression, albeit to a lesser extent in Vero cells. However, both cell types subsequently returned to and remained in the G0/G1 phase thereafter, despite additional treatment with rPMT. In fact, rPMT was able to stimulate cell cycle progression only in Vero cells that were not yet confluent; once they reached full confluence, rPMT had no further influence on mitogenesis or cell cycle progression. This transient mitogenic response, which is followed by cell cycle arrest, is in contrast to previous reports, which suggested that rPMT treatment caused a sustained and irreversible mitogenic response in fibroblasts (16, 33). Our results instead suggest that the initial mitogenic response to rPMT was not sustained and that cells thereafter arrest and become unresponsive to further treatment with rPMT.

Since the method employed for cell cycle analysis did not allow us to discriminate between the G0 and G1 phase, we wanted to determine whether cells had indeed progressed through the cell cycle at early times after treatment (days 1 to 2) and then had arrested in G0 or G1. We also wanted to determine at what point in the cell cycle PMT was exerting its effects and what might be the difference between Swiss 3T3 and Vero cells that could account for the observed differences. To achieve this, we assessed the effect of rPMT on the expression of a number of cell cycle markers. Specifically, we focused on events associated with the transition from G0 to G1; through early-, mid-, and late-G1 phases; and into early S phase of the cell cycle. The key proteins that regulate cell cycle progression through these early phases include the MAPKs, the D and E cyclins, p21, PCNA, c-Myc, and the Rb proteins (p110, p107, and p130) (19, 31, 39, 43).

Dephosphorylated Rb proteins sequester E2F transcription factors that are required for progression into and through S phase (19). Rb proteins are hypophosphorylated in G0 and are progressively phosphorylated as cells progress through G1, finally reaching a hyperphosphorylated state at the G1/S border (39, 43). Hypophosphorylated Rb/p130 maintains cells in G0, and its phosphorylation, in particular, plays an important role in allowing the transition from G0 to early G1 (4, 15, 43). The observed hyperphosphorylation of p130 by rPMT indicated that rPMT induced cells to exit G0 and enter the G1 phase of the cell cycle, and the continued presence of hyperphosphorylated p130 suggested that cells did not later exit the cell cycle into G0.

Members of the cyclin D family form complexes with Cdk4/6 or Cdk2, PCNA, and p21, which then causes Rb inactivation via phosphorylation and release of E2F proteins (43). Normally, expression of cyclins D1 and D2, as well as p21 and PCNA, begins early in G1 near the G0-to-G1 transition (29, 31, 39). Cyclins D3 and E are synthesized later in G1 (4, 15, 31), with maximal accumulation of cyclin E occurring with cell entry into S phase. Both p21 and PCNA play critical roles in regulating transition through early to mid-G1. Low levels of p21 promote Rb phosphorylation, whereas subsequent high levels of p21 inhibit Rb phosphorylation. The release of E2F drives cell cycle progression by inducing expression of enzymes required for DNA synthesis, cyclin E, and c-Myc, which are required for driving cells through G1 and into S phase (37, 39).

rPMT treatment clearly up-regulated the expression of each of the D and E cyclins in Swiss 3T3 cells, confirming that rPMT induces cell cycle reentry from G0 into G1 and progression through G1 and into S. Coupled with the concomitant increase in p21, PCNA, p107, and c-Myc levels, and p130 hyperphosphorylation, along with the flow cytometry results, this strongly supports an initial rPMT-induced mitogenic response. Thus, rPMT-treated Swiss 3T3 cells were stimulated enough to progress through the cell cycle for at least one or two complete rounds, accounting for the two- to threefold increase in cell numbers. However, the subsequent decline in cyclin, PCNA, and p107 levels and the return to control percentages of cells in G1, S, and G2/M indicate that this initial response is not sustained and that thereafter, the cells again arrested in G1 and became unresponsive to further rPMT treatment. Based on the expression profiles, rPMT-treated cells appear to arrest primarily in mid- to late G1, since cyclin D2 and E and hyperphosphorylated Rb/p130 levels continued to remain relatively high.

In contrast to the case for Swiss 3T3 cells, there was a low, basal level of PCNA and c-Myc expression in confluent Vero cells but no expression of cyclin E. rPMT up-regulated cyclin D1 and D2, p21, p107, and particularly c-Myc protein levels but did not up-regulate the expression of PCNA or cyclins D3 and E. PCNA was initially identified as a marker for proliferating cells in S phase (1, 20). However, PCNA has been shown more recently to be a critical component of cyclin D2 and D3 complexes with Cdks that regulate cell transition through early to mid-G1 phase (39, 42). PCNA expression normally begins to increase during early to mid-G1 phase and continues to increase in amount throughout the cell cycle, remaining high in proliferating cells (12, 42). Failure to produce adequate quantities of PCNA would result in a cell cycle block in mid- or late G1 phase. In addition, rPMT's failure to up-regulate cyclins D3 and E in Vero cells, both of which are critical for driving cells from G1 into S phase (4, 15, 31), would likewise result in a cell cycle block in late G1, despite relatively high levels of c-Myc and hyperphosphorylated p130. Such a cell cycle arrest is consistent with our observations for Vero cells, where despite a pronounced morphological response, we observed no significant increase in cell number or continued cell cycle progression.

Study of the mechanism of action of bacterial toxins has significantly contributed to our understanding of how these protein toxins mediate their pathogenic effects on host cells and has provided a wealth of information about the roles of heterotrimeric G proteins in cellular signaling. Our data suggest that rPMT utilizes Gq/11 proteins to differentially modulate mitogenic and cytoskeletal signaling pathways in host cells. The mitogenic response in fibroblast cells is thought to be a downstream event of Gq/11 activation by rPMT (26, 38, 46). Recent evidence suggests that stimulation of the p42/p44 MAPK pathway by rPMT occurs upstream via Gq/11-dependent transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor, which is not protein kinase C dependent (38). We have now shown that the rPMT-mediated mitogenic response is dependent on the differential regulation of downstream signaling proteins involved in cell cycle progression. This finding points to an important pathogenic consequence of toxins during bacterial infection, i.e., the potential for differential cellular outcome due to their action on different target cells.

We have also shown that the initial rPMT-mediated mitogenic response is not sustained. After 2 to 3 days, cells arrest in mid- to late G1 phase of the cell cycle and become insensitive to further treatment with rPMT. This finding is in keeping with our earlier observations that rPMT only transiently activates the Gq/11 protein (46), which is then followed by irreversible inactivation and uncoupling of the signaling pathway. This finding further suggests that the initial enhanced modulation of mitogenic signaling pathways by rPMT-mediated activation of Gq/11-protein is followed by a subsequent, irreversible shutdown of the pathway that is no longer responsive to further stimulation by rPMT.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants NIH/NIAID AI38396 and USDA/NRI 1999-02295 (to B.A.W.).

We thank Barbara Hull and Nancy Bigley for helpful discussions, Gary Durack for assistance with cell cycle analysis, and Brian Ho for assistance with photomicrographic imaging.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bravo R, Frank R, Blundell P A, Macdonald-Bravo H. Cyclin/PCNA is the auxiliary protein of DNA polymerase-δ. Nature. 1987;326:515–517. doi: 10.1038/326515a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chrisp C E, Foged N T. Induction of pneumonia in rabbits by use of a purified protein toxin from Pasteurella multocida. Am J Vet Res. 1991;52:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dikic I, Blaukat A. Protein tyrosine kinase-mediated pathways in G protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell Biochem Biophys. 1999;30:369–387. doi: 10.1007/BF02738120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong F, Cress W D, Jr, Agrawal D, Pledger W J. The role of cyclin D3-dependent kinase in the phosphorylation of p130 in mouse BALB/c 3T3 fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6190–6195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudet L I, Chailler P, Dubreuil J D, Martineau-Doize B. Pasteurella multocida toxin stimulates mitogenesis and cytoskeleton reorganization in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol. 1996;168:173–182. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199607)168:1<173::AID-JCP21>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falbo V, Pace T, Picci L, Pizzi E, Caprioli A. Isolation and nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4909–4914. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4909-4914.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiorentini C, Arancia G, Caprioli A, Falbo V, Ruggeri F M, Donelli G. Cytoskeletal changes induced in HEp-2 cells by the cytotoxic necrotizing factor of Escherichia coli. Toxicon. 1988;26:1047–1056. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(88)90203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiorentini C, Donelli G, Matarrese P, Fabbri A, Paradisi S, Boquet P. Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1: evidence for induction of actin assembly by constitutive activation of the p21 Rho GTPase. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3936–3944. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.3936-3944.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiorentini C, Fabbri A, Flatau G, Donelli G, Matarrese P, Lemichez E, Falzano L, Boquet P. Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (CNF1), a toxin that activates the Rho GTPase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19532–19537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flatau G, Lemichez E, Gauthier M, Chardin P, Paris S, Fiorentini C, Boquet P. Toxin-induced activation of the G protein p21 Rho by deamidation of glutamine. Nature. 1997;387:729–733. doi: 10.1038/42743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foged N T. Pasteurella multocida toxin: the characterization of the toxin and its significance in the diagnosis and prevention of progressive atrophic rhinitis in pigs. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand. 1992;100(Suppl. 25):1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giordano M, Danova M, Pellicciari C, Wilson G D, Mazzini G, Conti A M, Franchini G, Riccardi A, Romanini M G. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)/cyclin expression during the cell cycle in normal and leukemic cells. Leukoc Res. 1991;15:965–974. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(91)90101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutkind J S, Novotny E A, Brann M R, Robbins K C. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes as agonist-dependent oncogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4703–4707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall R A, Premont R T, Lefkowitz R J. Heptahelical receptor signaling: beyond the G protein paradigm. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:927–932. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herzinger T, Reed S I. Cyclin D3 is rate-limiting for the G1/S phase transition in fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14958–14961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins T E, Murphy A C, Staddon J M, Lax A J, Rozengurt E. Pasteurella multocida toxin is a potent inducer of anchorage-independent cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4240–4244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horiguchi Y, Inoue N, Masuda M, Kashimoto T, Katahira J, Sugimoto N, Matsuda M. Bordetella bronchiseptica dermonecrotizing toxin induces reorganization of actin stress fibers through deamidation of Gln-63 of the GTP-binding protein Rho. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11623–11626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Igishi T, Gutkind J S. Tyrosine kinases of the Src family participate in signaling to MAP kinase from both Gq and Gi-coupled receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;244:5–10. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King K L, Cidlowski J A. Cell cycle regulation and apoptosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:601–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurki P, Lotz M, Ogata K, Tan E M. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)/cyclin in activated human T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1987;138:4114–4120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lacerda H M, Lax A J, Rozengurt E. Pasteurella multocida toxin, a potent intracellularly acting mitogen, induces p125FAK and paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation, actin stress fiber formation, and focal contact assembly in Swiss 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:439–445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacerda H M, Pullinger G D, Lax A J, Rozengurt E. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 from Escherichia coli and dermonecrotic toxin from Bordetella bronchiseptica induce p21(rho)-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase and paxillin in Swiss 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9587–9596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lax A J, Chanter N. Cloning of the toxin gene from Pasteurella multocida and its role in atrophic rhinitis. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:81–87. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-1-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lax A J, Chanter N, Pullinger G D, Higgins T, Staddon J M, Rozengurt E. Sequence analysis of the potent mitogenic toxin of Pasteurella multocida. FEBS Lett. 1990;277:59–64. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80809-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mullan P B, Lax A J. Pasteurella multocida toxin is a mitogen for bone cells in primary culture. Infect Immun. 1996;64:959–965. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.959-965.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy A C, Rozengurt E. Pasteurella multocida toxin selectively facilitates phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis by bombesin, vasopressin, and endothelin. Requirement for a functional G protein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25296–25303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oswald E, Sugai M, Labigne A, Wu H C, Fiorentini C, Boquet P, O'Brien A D. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 2 produced by virulent Escherichia coli modifies the small GTP-binding proteins Rho involved in assembly of actin stress fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3814–3818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pennings A M, Storm P K. A test in Vero cell monolayers for toxin production by strains of Pasteurella multocida isolated from pigs suspected of having atrophic rhinitis. Vet Microbiol. 1984;9:503–508. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(84)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez-Roger I, Kim S H, Griffiths B, Sewing A, Land H. Cyclins D1 and D2 mediate myc-induced proliferation via sequestration of p27(Kip1) and p21(Cip1) EMBO J. 1999;18:5310–5320. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pettit R K, Ackermann M R, Rimler R B. Receptor-mediated binding of Pasteurella multocida dermonecrotic toxin to canine osteosarcoma and monkey kidney (Vero) cells. Lab Invest. 1993;69:94–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pines J. Cyclins and their associated cyclin-dependent kinases in the human cell cycle. Biochem Soc Trans. 1993;21:921–925. doi: 10.1042/bst0210921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pullinger G D, Adams T E, Mullan P B, Garrod T I, Lax A J. Cloning, expression, and molecular characterization of the dermonecrotic toxin gene of Bordetella spp. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4163–4171. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4163-4171.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rozengurt E, Higgins T, Chanter N, Lax A J, Staddon J M. Pasteurella multocida toxin: potent mitogen for cultured fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:123–127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rutter J M, Luther P D. Cell culture assay for toxigenic Pasteurella multocida from atrophic rhinitis of pigs. Vet Rec. 1984;114:393–396. doi: 10.1136/vr.114.16.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt G, Sehr P, Wilm M, Selzer J, Mann M, Aktories K. Gln 63 of Rho is deamidated by Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factor-1. Nature. 1997;387:725–729. doi: 10.1038/42735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schoneberg T, Schultz G, Gudermann T. Structural basis of G protein-coupled receptor function. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;151:181–193. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuhmacher M, Staege M S, Pajic A, Polack A, Weidle U H, Bornkamm G W, Eick D, Kohlhuber F. Control of cell growth by c-Myc in the absence of cell division. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1255–1258. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80507-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seo B, Choy E W, Maudsley S, Miller W E, Wilson B A, Luttrell L M. Pasteurella multocida toxin stimulates mitogen-activated protein kinase via Gq/11-dependent transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2239–2245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shackney S E, Shankey T V. Cell cycle models for molecular biology and molecular oncology: exploring new dimensions. Cytometry. 1999;35:97–116. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19990201)35:2<97::aid-cyto1>3.3.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staddon J M, Barker C J, Murphy A C, Chanter N, Lax A J, Michell R H, Rozengurt E. Pasteurella multocida toxin, a potent mitogen, increases inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and mobilizes Ca2+ in Swiss 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4840–4847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Staddon J M, Chanter N, Lax A J, Higgins T E, Rozengurt E. Pasteurella multicoda toxin, a potent mitogen, stimulates protein kinase C-dependent and -independent protein phosphorylation in Swiss 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11841–11848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szepesi A, Gelfand E W, Lucas J J. Association of proliferating cell nuclear antigen with cyclin-dependent kinases and cyclins in normal and transformed human T lymphocytes. Blood. 1994;84:3413–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas N S B, Pizzey A R, Tiwari S, Williams C D, Yang J. p130, p107, and pRb are differentially regulated in proliferating cells and during cell cycle arrest by alpha-interferon. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23659–23667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker K E, Weiss A A. Characterization of the dermonecrotic toxin in members of the genus Bordetella. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3817–3828. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3817-3828.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson B A, Ponferrada V G, Vallance J E, Ho M. Localization of the intracellular activity domain of Pasteurella multocida toxin to the N terminus. Infect Immun. 1999;67:80–87. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.80-87.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson B A, Zhu X, Ho M, Lu L. Pasteurella multocida toxin activates the inositol triphosphate signaling pathway in Xenopus oocytes via Gqα-coupled phospholipase C-β1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1268–1275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]