Abstract

In the era of precision medicine, with the deepening of the research on malignant tumor driving genes, clinical oncology has fully entered the era of targeted therapy. For non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the development of targeted drugs targeting driver genes, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), has successfully opened up a new model of targeted therapy. At present, proto-oncogene rearranged during transfection (RET) fusion gene is an important novel oncogenic driving target, and specific receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) targeting RET fusion have been approved. This article will review the latest research about the molecular characteristics, pathogenesis, detection, and clinical treatment strategies of RET rearrangements especially in China.

Keywords: non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), RET rearrangements, targeted therapy

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause in cancer mortality with 1.79 million deaths worldwide accounting for 18%, and ranks second in new cases with approximately 2.20 million accounting for 11.4% in 2020, according to the report by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).1 With the advent of targeted drugs, the treatment approaches of lung cancer, especially non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), have been to a large extent expanded. Targets represented by epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) have created the era of tumor precision targeted therapy.2,3 To date, the targeted drugs such as osimertinib and crizotinib are not only widely used in locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC, but also in postoperative adjuvant therapy.4

With the continuous in-depth research on NSCLC driver genes, rearranged during transfection (RET) gene fusions are one type of driver genes identified in recent years.5 For NSCLC patients with the mutations, specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) Selpercatinib6 and Pralsetinib7 targeting RET gene fusions have been approved for marketing. This article will review the latest research advances in the pathogenic mechanism of RET gene fusions, audience population and detection methods, and targeted therapy drugs around the world, especially in China.

Overview and Pathogenic Mechanism of RET Gene

Overview of RET Gene

In 1985, Takahashi, et al. discovered a gene in transformed mouse NIH3T3 cells for the first time, which was produced during the recombination of 2 unconnected DNA fragments during the transfer process, later named the RET gene.8,9 The gene is confirmed to be a proto-oncogene formed by rearrangement or fusion during the transfection process. RET gene is located in the 10q11.2 region of the long arm of chromosome 10, contains 21 exons, 60kb in size, and mainly encodes for a protein of approximately 1100 amino acids belonging to the tyrosine kinase receptor superfamily (single transmembrane receptor glycoprotein) with at least 4 transcription products.10 The expression of RET can be detected in normal neurons, para/sympathetic ganglia, parafollicular cells of thyroid, adrenal medulla cells, which is necessary for normal development of the nervous system and kidney. RET is a member of the gail cell line-derived neurotrophic growth factor (GDNF) family receptor complex and a receptor for the ligands GDNF, Neurtirin, Artemin, or Persephin, which contains 3 relatively independent domains, including carboxy-terminal intracellular tyrosine kinase domain, transmembrane domain and cysteine-rich cadherin-like extracellular domain.11 RET protein can be activated by the complex of GDNF family ligand-GFRα complex-RET kinase between 4 co-receptors called GFRα1-4 and 4 GDNF family ligands. GFRα can specifically bind to GDNFs family members, promote the phosphorylation of RET protein receptors and activate RET, thereby triggering RAS-RAF-MARK, PI3K-AKT-mTOR, and JAK-STAT signal pathways to promote the occurrence and development of tumors.12,13

Mutant Form of RET Gene

RET gene is a new type of proto-oncogenic driver gene, which has been proved to be closely related to the occurrence and development of various tumors.14 The overall mutation rate of RET is 1.8%,15 including deletion, point mutation, amplification, rearrangement, and fusion.16 (1) RET deletion: Related to the onset of congenital Hirschsprung's disease (CHD). (2) Point mutations in RET gene: The most common M918T point mutation is commonly found in familial medullary thyroid carcinoma (FMTC); (3) Rearrangement and fusion of RET gene: Under certain circumstances, the nucleotide sequences of RET gene and other genes are rearranged or fused to form a brand new fusion transcript and fusion protein. These genes combined with RET gene are called gene partners. After RET fused with gene partners, oncogenic activation relies on the activation of RET kinase, thus to maintain the proliferation and survival of tumor cells, that is, the carcinogenic gene addiction.17–19 Carcinogenic gene addiction is mainly found in papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) and NSCLC (especially lung adenocarcinoma, LADC), which is also observed in tumors of the digestive system, breast cancer, and ovarian cancer.20,21

Pathogenic Mechanism of RET Rearrangement

RET gene can be an oncogene in a variety of tumors, and the RET rearrangement protein that retains the kinase domain is the driving target of NSCLC and medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC). Currently, more than 50 types of RET rearrangement have been found in patients with PTC and NSCLC. Abnormal structural activation is achieved mainly through chromosomal rearrangement (Table 1).22 For different diseases, the rearrangement and fusion forms are varied. In PTC, coiled-coil domain-containing protein 6 (CCDC6)-RET contributes to about 60%; nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4)-RET contributes to 30%; and protein kinase A regulatory subunit 1α (PRKAR1A)-RET contributes to 9%.22–24 In NSCLC, the most common RET rearrangement are pericentric or paracentric inversion with kinesin family member 5B (KIF5B) contributing to ∼68.3%; with CCDC6 contributing to 16.8%; with NCOA4 contributing to 1.2% and rare fusions EPHA5-RET, TRIM33-RET, and CLIP1-RET.25,26

Table 1.

RET Fusions and Common Tumors.

| RET fusions | PTC | NSCLC | Other tumor types | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCDC6-RET | RET/PTC1 | √ | √ | Breast cancer, colon cancer |

| PRKAR1A-RET | RET/PTC2 | √ | ||

| NCOA4-RET | RET/PTC3 | √ | √ | Breast cancer, colon cancer |

| ELE1-RET | RET/PTC4 | √ | ||

| GOLGA5-RET | RET/PTC5 | √ | ||

| TRIM24-RET | RET/PTC6 | √ | √ | Colon cancer |

| TRIM33-RET | RET/PTC7 | √ | √ | |

| KTN1-RET | RET/PTC8 | √ | ||

Abbreviations: CCDC6, coiled-coil domain-containing protein 6; NCOA4, nuclear receptor coactivator 4; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; RET, rearranged during transfection.

It is reported that the molecular mechanism of RET rearrangement is similar to that of ALK fusion in NSCLC.26 The recombination is mainly through its own DNA breakage and connection with connecting with other genes. The resulting fusion gene containing the N-terminus of the fusion partner joined with the C-terminus of the RET gene, including the catalytic tyrosine kinase domain. The breakpoints of the gene partner can provide dimer domains for the successful formation of fusion genes in the cytoplasm. The degraded fusion partner after ubiquitination can alter domains and expose the phosphorylation site, thus activating the RET gene, leading to the occurrence and development of tumors.18,26,27

In addition, RET rearrangement may affect the function of gene partners to some extent. The pro-apoptotic CCDC6 can inhibit the expression of transcription factor CREB1, and negatively regulate the growth and differentiation of cell. Overexpression of CCDC6 can induce thyroid cell death. NCOA4 is a co-activator of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and androgen receptors (ARs), and its expression is down-regulated in aggressive prostate cancer and breast cancer.28–30 Overall, on the one hand, the generation of this new fusion gene may cause the abnormal activation of downstream signaling pathways; on the other hand, it weakens the anticancer effect of gene partners to a certain extent, leading to the occurrence and development of tumors.31

Detection of RET Rearrangement

Population Undergoing RET Rearrangement Detection

With the development of medicine, drugs targeting rare gene mutations are commonplace. The reason is that they have brought revolutionary breakthroughs and even subversions to the original treatments. Although the incidence of RET rearrangement in NSCLC is only 1.4% to 2.5%,32 it is primarily seen mainly seen in young patients with poorly differentiated LADC who do not smoke or have a history of mild smoking.33,34 Due to China’s huge population base in NSCLC patients, the number of new cases with RET rearrangement-positive NSCLC is not small every year.

It is currently believed that RET rearrangement is independent and mutually exclusive with the existence of EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and other driver genes.35 In contrast, some studies show that RET rearrangement is one of the potential resistance mechanisms after targeted drug therapy.36,37 Therefore, when patients are pathologically diagnosed as locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC, or adenosquamous carcinoma containing adenocarcinoma components or even combined small-cell lung cancer (C-SCLC)38; patients develop drug resistance after EGFR-TKI and ALK-TKI treatments; and patients with invasive adenocarcinoma are pathologically confirmed after surgery, RET rearrangement detection is recommended if possible.26,39

Conditions and Methods of RET Rearrangement Detection

Accurate detection is prior to precise treatment. In practice, detection is mainly based on tumor tissue and cytology DNA or RNA, cell-free DNA (cfDNA), or protein. The common molecular pathology detection methods are summarized as follows, next-generation sequencing (NGS), reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), immunohistochemistry (IHC), and so on. However, any detection method can be limited to the requirements of detection conditions, sample quantity, and quality, amount and type of gene mutations, instruments, and technology. It is recommended to use multiple platforms to cross-complement each other for verification, if necessary.

FISH Technology

Currently, FISH technology is the gold standard for gene fusion and translocation detection. The main principle is to use fluorescently labeled specific nucleic acid probes to hybridize with the corresponding sequences of target DNA in the cell, and then to determine the fusion/separation status of the target gene by monitoring fluorescence signal intensities. Considering the high requirement for clinical operation and interpretation and the flaw in clarifying the fusion information of gene partners, FISH technology is not recommended.40,41 In addition, some studies have shown that FISH technology has low sensitivity compared to some nonclassical fusions.42

NGS

The detailed information of gene partners and other potential therapeutic targets can be clarified for detecting RET rearrangement by NGS based at the DNA and RNA levels.43,44 Currently, NGS is preferentially recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines (NCCN) and the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO) for detecting RET rearrangement. It is noted that the result based on detecting DNA could not completely represent the result based on detecting RNA. In addition, in rare cases, gene translocation at the DNA level would not cause the specific expression of the fusion gene. The detection at the RNA level effects sequencing library construction, which is limited to specific common types of RET rearrangements, and requires high-quality sample, narrow time window, and higher operation skills.45,46

RT-PCR

It is characterized by quickly and easily identifying the known RET rearrangement variants. However, there may be a possibility of false negative results.26

Liquid Biopsy-Based Free DNA Detection

cfDNA widely exists in various body fluids, such as blood, polyserositis (pleural effusion, ascites, and pelvic effusion), cerebrospinal fluid, and so on. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) with the size 130 to 150 kb is the free DNA containing tumor-specific mutation information that was released by tumor cells into the circulatory system through apoptosis, necrosis, or secretion.47–49 At present, clinical guidelines recommend that gene mutation information can be obtained based on liquid biopsy when solid tumor tissue is not accessible.50 Considering the low concentration of ctDNA and its short half-life of only a few hours,51,52 the detection equipment has higher requirement for the sensitivity and time limit and the detection result needs to be viewed dialectically, even if it's negative.

The Treatment Strategy of NSCLC with RET Rearrangement Gene

Limitations of Existing Treatments

Before the emergence of specific RET inhibitors, the treatments of RET rearrangement-positive NSCLC are limited and lacked specificity, and the first-line treatment was basically the same with NSCLC patients harboring negative driver mutations.

Chemotherapeutic Drug Treatment

In 108 RET-rearranged patients with NSCLC, the progression-free survival (PFS) was 6.6 months, and ORR was 51%.53 A multicenter retrospective study in China showed that PFS is 5.2 to 9.2 months on chemotherapy-based comprehensive treatment first-line program, 2.8 to 4.9 months on the second-line program and ORR 45%, and that chemotherapeutic drug treatment containing pemetrexed was more effective.54

Treatment of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs)

ICIs is not an effective treatment for NSCLC patients with RET rearrangement gene. First, the expression of programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) in RET-rearranged patients varies greatly, about 0% to 70%.55 Second, the response rate to programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/PD-L1 treatment is low. Three retrospective analyses revealed that the median progression-free survival (mPFS) ranged from 2.1 to 7.6 months and the ORR ranged from only 6.0% to 37.5% after ICIs treatment in patients with RET rearrangement-positive NSCLC.56–58 The safety and efficacy of immunotherapy in relation to patients with RET gene abnormalities as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Safety and Efficacy of Immunotherapy for Patients With RET Fusion-Positive Metastatic NSCLC.

| Study | n | ORR | mPFS (months) | mOS (months) | PD-L1 positive rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mazieres et al. 201956 | 16 | 6.0% | 2.1 | 21.3 | / |

| Bhandari et al. 202157 | 69 | / | 4.2 | 19.1 | 46% |

| Guisier et al. 201958 | 9 | 37.5% | 7.6 | / | 33% |

| Meng et al. 202259 | 49 | 21.0% | 6.7 | / | / |

Abbreviations: ORR, objective response rate; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; RET, rearranged during transfection; mPFS, median progression-free survival; mOS, median overall survival.

Multi-TKI

Cabozantinib, known as the “anti-cancer all-rounder”, is a TKI targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (VEGFR1), VEGFR 2, VEGFR 3, neurotrophin receptor kinase (NTRK), ROS1, mesenchymal–epithelial transformation factor (MET), RET, AXL, and KIT (CD117). We summarized the clinical trials of multi-target inhibitors for RET-rearranged patients with NSCLC (Table 3). In phase II clinical trial (NCT01639508), adverse reactions are responsible for 96.2% of patients with advanced RET-rearranged NSCLC, and 73% of patients required drug reductions due to treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs).60 Vandetanib is a small molecule TKI targeting RET, EGFR, VEGFR, and other driver oncogenes. The LURET phase II study evaluated the efficacy and safety of vandetanib in previously treated patients with RET-rearranged advanced NSCLC and the relevant results were shown in Table 3.61 In 2017, Solomon et al. summarized the application effects of the multi-target inhibitors cabozantinib, vandetanib, sunitinib, sorafenib, and lenvatinib in 53 patients, which showed the median duration of response (DOR) of only 1.8 months, mPFS 2.3 months, and median overall survival (mOS) 6.8 months.62 In addition, these TKIs could simultaneously inhibit proteins such as RET, VEGR, EGFR, and induce vasoconstriction to bring about adverse reactions such as hypertension and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.63

Table 3.

Summary of Clinical Trials of Multi-Target Inhibitors for RET-Rearranged Patients With NSCLC.

| Trial | n | Dosage | ORR | mPFS (months) | mOS (months) | Downgraded dose rate | Treatment termination rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabozantinib | II | 26 | 60mg daily | 28% | 5.5 | 9.9 | 73% | 8% | |

| Japan Vandetanib | II | 19 | 300mg daily | 18% | 4.7 | 11.1 | 53% | 21% | |

| Korea[64] | II | 18 | 53% | 4.5 | 11.6 | 23% | - | ||

| Vandetanib + everolimus [65] | I | 17 | 300mg + 10mg daily | 73% | 8 | - | - | - | |

| Sorafenib [66] | II | 3 | 400mg daily | 0 | - | - | 33% | - | |

| Sunitinib [67] | I | 22 | 50mg daily (4 weeks on, 2 weeks off) |

9% | 2.95 | 5.85 | 9.10% | 0 | |

| Lenvatinib [68] | II | 25 | 24mg daily | 16% | 7.3 | - | 64% | 20% | |

| RXDX-105 [69] | I/Ib | 31 | 275mg daily | 19% | - | - | - | - | |

Abbreviations: ORR, objective response rate; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; RET, rearranged during transfection; mPFS, median progression-free survival; mOS, median overall survival.

It can be seen that multi-target inhibitors do not have an ideal therapeutic effect with high-efficiency, low-toxicity, and precise targeting. Whether it is chemotherapy, ICIs, or multi-targeted TKIs, the effectiveness is very limited in patients with RET rearrangement-positive NSCLC.64–69

Specific Drugs That Target RET Rearrangement Genes

It is urgent to find targeted drugs with better clearance rates and longer half-lives that can strongly inhibit wild-type RET and RET mutation, avoid VEDF-2, and drug-resistant mutations.

Selpercatinib (LOXO-292)

Selpercatinib (LOXO-292, Retevmo®, Eli Lilly and Company) is a novel, highly selective, and potent, small-molecule inhibitor of RET. A global phase I/II clinical trial LIBRETTO-001 enrolled 144 patients with RET rearrangement-positive NSCLC from 65 medical centers in 12 countries.70 105 patients with RET-rearranged NSCLC were given platinum-based chemotherapy, including 49 patients in a phase I dose escalation trial, and 56 patients in a phase I dose escalation trial or a phase II dose expansion trial. In addition, 39 treatment-naive patients participated in phase II clinical trial. The findings demonstrated that a 64% objective response rate (ORR) (95% CI: 54-73) in patients given platinum-based chemotherapy and 85% ORR (95% CI: 70-94) in treatment-naive patients with RET rearrangement-positive NSCLC (n = 39), a median PFS of 18.4 months and 1-year PFS rate of 68%. Especially, for brain metastasis, Selpercatinib showed good ability to control intracranial lesions with 82% intracranial ORR and 100% intracranial disease control rate (DCR). In all 80 patients with brain metastasis, the intracranial mPFS was 13.7 months. The majority of adverse reactions were grades 3/4 TRAEs occurring in increased ALT level (12%), increased AST level (10%), hypertension (21%), and hyponatremia (11%). Selpercatinib was designated as an orphan drug by the US FDA in 2019, and then granted breakthrough therapy, accelerated approval, and priority -review designations.71 (1) Patients with RET rearrangement-positive NSCLC who have progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy and PD-(L)1 treatment; (2) Patients with RET mutant MTC who have progressed after previous treatment and have no alternative treatments; (3) Patients with advanced RET rearrangement-positive thyroid cancer who have progressed after previous treatment and have no alternative treatments, and require systemic treatment. Selpercatinib was approved by the US FDA in May 2020, and became the first broad spectrum anticancer drug that carries the RET gene over the world.70,72

Currently, a phase III clinical trial LIBRETTO-431 (NCT04194944) is still in progress, which aims to compare the effectiveness between Selpercatinib used as first-line treatment and pemetrexed + cisplatin or carboplatin ± Prembrolizumab for advanced or metastatic RET rearrangement NSCLC, and the preliminary results are expected to be announced in 2023.73

Libretto-321 Trial (NCT04280081) was a part of the LIBRETTO-431 study and led by Professor Lu Shun from Shanghai, China. At the World Conference on Lung Cancer (WCLC) in 2021, Professor Lu Shun shared the efficacy and safety of Selpercatinib in Chinese patients with advanced RET rearrangement NSCLC.74 The study was divided into 3 cohorts: (1) Cohort 1 (n = 30) included patients with advanced RET rearrangement solid tumors who were progressive or intolerable during the previous standard first-line treatment; (2) Cohort 2 (n = 26) included patients with advanced RET mutant MTC who had received or not systemic treatment; (3) Cohort 3 (n = 21) included patients who met the criteria of cohort 1 or 2 but had no measurable lesions, or patients who did not meet the criteria of cohorts 1 or 2, or patients whose ctDNA was RET rearrangement but had no lesions. In the main analysis group (n = 26), patients who received Selpercatinib 160mg bid showed an ORR (a complete or partial response) of 69.2%, as determined by an Independent Review Committee (IRC) after 9.7 months of follow-up; and an ORR 87.5% in treatment-naive patients with RET rearrangement-positive NSCLC, and an ORR 61.1% in previously treated patients. Safety analysis (n = 77) showed the most common grade 3 TRAEs were hypertension (19.5%), increased ALT level (15.6%), and increased AST level (15.6%). There were 35.2% of patients adjusting treatment doses due to related TEAEs, and 3 patients had undergone treatment interruptions. The findings were basically consistent with the results of the previous Phase I/II clinical trial LIBRETTO-001 (NCT03157128) among the global and East Asian populations. Selpercatinib demonstrated high specificity, high efficiency, and low side effects.

In addition, the LIBRETTO-121 study (NCT03899792) is an open-label, multicenter Phase 1/2 study of oral LOXO-292 in pediatric participants with an activating RET alteration and an advanced solid or primary CNS tumor, which is still ongoing. As of October 2, 2020, 11 patients have been treated and the best response evaluation profile shows unconfirmed partial responses in 4 patients, stable disease in 6 patients (2 patients lasting ≥16 weeks), and progressive disease in 1 patient. Conclusions consistent with the results of the adult trial, preliminary evidence of the safety and efficacy of Selpercatinib in pediatric patients with solid tumors with RET mutations was demonstrated.75

Pralsetinib (BLU-667)

Pralsetinib (BLU-667, developed by Blueprint Medicines), an oral RET inhibitor, was approved by the US FDA in September 2020,7 and approved conditionally by NMPA China in March 2021 on basis of ARROW (NCT03037385) clinical trial.76 ARROW study was a phase I/II clinical trial, which aimed at evaluating the safety, tolerability, and effectiveness of Pralsetinib in patients with RET-rearranged NSCLC, RET mutant MTC, and RET-driven advanced solid tumors. The study enrolled patients with metastatic NSCLC with RET rearrangement who had progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy or did not receive systemic treatment in different cohorts. In the cohort of 87 patients who have previously received platinum-based chemotherapy drugs, 37 Chinese patients were included. According to the RECIST version 1.1, ORR and DOR were evaluated by blinded independent central review (BICR) (Table 4). In terms of drug safety, the most common grade 3 TRAEs were mainly neutropenia (43 cases, 18%), hypertension (26 cases, 11%), and anemia (24 cases, 10%). No treatment-related deaths were reported. The findings of the study demonstrated that Pralsetinib has a wide-ranged and long-lasting anti-tumor activity in RET rearrangement-positive NSCLC, and the data for the Chinese population is basically consistent with the global trial.

Table 4.

Statistics of Basic Information and Validity Results of ARROW Clinical Trial Among Patients who Have Previously Received Platinum-Based Chemotherapy and RET Fusion-Positive Metastatic NSCLC.

| Global cases (n = 87) | Chinese cases (n = 37) | |

|---|---|---|

| Basic information | ||

| Median age (years) | 60 (28–85) | 54 (26–77) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 44 (51%) | 17 (46%) |

| Female | 43 (49%) | 20 (54%) |

| Previously received treatments (n, %) | 2 | 2 |

| CNS metastasis | 37 (43%) | 15 (41%) |

| PD-1/PD-L1 treatment | 39 (45%) | 14 (38%) |

| Kinase inhibitor therapy | 22 (25%) | 14 (38%) |

| Radiotherapy | 45 (52%) | 11 (30%) |

| Detection method for RET fusion | ||

| NGS | 67 (77%) | — |

| FISH | 18 (21%) | — |

| Others | 2 (2%) | — |

| Common RET fusion gene | ||

| KIF5B | 65 (75%) | 23 (62%) |

| CCDC6 | 15 (17%) | 7 (19%) |

| Effective cases (n) | 87 | 32 |

| ORR (95% CI) | 57 (46-68) | 56 (38-74) |

| CR | 5.70% | 3.10% |

| PR | 52% | 53% |

| DOR (n) | 50 | 18 |

| Median (months, 95% CI) | NE (15.2-NE) | NE (NE-NE) |

| DOR ≥6 months | 80% | NE |

Abbreviations: CR, complete remission rate; CNS, central nervous system; CCDC6, coiled-coil domain-containing protein 6; DOR, duration of response; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; KIF5B, kinesin family member 5B; ORR, objective response rate; DOR, duration of response; NE, not yet estimable; NGS, next-generation sequencing; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; PR, partial remission rate; RET, rearranged during transfection.

Based on precise research and development, these potent RET inhibitors have currently changed the guidelines and clinical practice, which makes “de chemotherapy” possible in the era of precision medicine.

Zeteletinib (BOS172738)

Zeteletinib is an oral targeted RET mutation-specific inhibitor. In phase I clinical study (NCT03780517),77 a dose escalation clinical trial and a cohort study of 67 cases with advanced solid tumors with RET mutation were included. Notably, of the 67 cases, 30 patients with NSCLC and 16 patients with MTC were recruited, whose ORR was 33% (n = 10/30) and 44% (n = 7/16), respectively. The ORR estimated by the investigator was 33% (n = 18/54). The most common TEAEs are elevated creatine kinase accounting for 54%, and dyspnea accounting for 34%. The overall safety of Zeteletinib is controllable. Currently, Zeteletinib is undergoing a phase I/II clinical study (NCT04161391) .9

TAS0953/HM06

TAS0953/HM06, a novel adenosine triphosphate-competitive and highly selective RET inhibitor. The binding of TAS0953/HM06 analogue to RET does not fill the space in the direction of the side chain of G810, suggesting that TAS0953/HM06 could effectively circumvent steric hindrance from solvent front substitutions. TAS0953/HM06 is highly active in the exnograft tumor model derived from Ba/F3 cells from mice expressing wild type (WT) or G810R KIF5B-RET. Therefore, most of the mutations induced by Selpercatinib or Pralsetinib resistance showed strong inhibition and showed a more potent anti-tumor effect in tumor models in theory. The drug is undergoing a phase I/II clinical study (NCT04683250).78

RXDX105

RXDX105 is an oral VEGF-sparing potent RET inhibitor. RXDX-105, a potent RET inhibitor developed by Ignyta, had an ORR of 0% in 20 patients with KIF5B-RET rearrangement NSCLC and 67% in 9 patients without KIF5B-RET rearrangement. Obviously, RXDX-105 does not have the potential to cover KIF5B-RET gene fusion .79 Possible reasons for this include the fact that KIF5B-RET-containing cell lines were not readily and widely available early in the development of RET inhibitors and that studies have shown at least a twofold increase in cellular IC50 values for KIF5B-RET-containing cell lines compared to CCDC6-RET or NCOA4-RET cell lines; also, KIF5B is thought to lead to KIF5B-RET rearrangement tumors with high levels of RET expression, compared to other chaperone genes such as CCDC6 and NCOA4, which are thought to lead to low levels of RET expression in tumors, implying that tumors containing KIF5B-RET rearrangement may have higher levels of RET chimeric proteins that require more precise targeted therapy to overcome. The most common adverse reactions were malaise (25%), diarrhea (24%), hypophosphatemia (18%), maculopapular rash (18%), and non-papular rash (17%), with no grade 4 adverse reactions observed.68,77

Drug Resistance of RET Inhibitors

It is to be appreciated that the 2 drugs Selpercatinib and Pralsetinib are effective against the gatekeeper mutations, such as V804M and S904F, produced by the multitarget inhibitors cabozantinib, levatinib, and vandetanib.80,81 However, new problem emerged along with the launch of two highly selective and potent RET TKIs—Selpercatinib and Pralsetinib. Similar to drug resistance of the first-generation RET inhibitors, a key question is how long they can be used. Drug resistance resulting from RET solvent front mutations in 2 cases was reported in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology in January 2020. Solvent frontal mutations refer to the region on the kinase surface where selective inhibitors can attach, and is destroyed by drug-resistant mutations, which greatly increases the possibility of drug resistance. Structural model predicted that the G810R/S/C/V mutant form of the RET solvent front mutations (ie, the evolution of G810) could spatially hinder the binding of Selpercatinib, leading to a common mechanism of drug resistance .62 In vitro experiments have confirmed that multikinase RET inhibitors such as cabotinib and vandetanib, and selective RET-TKIs would lose their drug activity due to such mutations. In addition, amplification of MET or KRAS is also one of the mechanisms of acquired resistance.82

Currently, the second-generation RET inhibitors are still in different stages of clinical trials. The phase I/II SWORD study80 is aimed to verify the safety and efficacy of TPX-0046 (Turning Point Therapeutics) for patients with RET mutations, and the preclinical studies of TPX-0046 have shown that the drug is sensitive to solvent front mutation G810R/S. The study recruited 21 patients, including 10 NSCLC and 11 MTC patients. The preliminary results showed that among the 5 patients who had not received RET inhibitor treatment, 4 patients showed significant tumor regression with a sustained remission time exceeding 5.5 months, accounting for 42%, 37%, 23%, and 3%, respectively. Among the 9 patients treated with RET inhibitor, the regression ratio of 3 patients reached 44%, 27%, and 17%, respectively. Finally, we look forward to the final results of clinical trial.

China Exploration and Research With RET Rearrangement in NSCLC

Long before selective RET inhibitors were approved by China, Chinese scholars have already recognized and explored the NSCLC with RET-rearranged. In an NGS analysis of 6125 Chinese NSCLC patients, 84 cases were found to be associated with RET-rearranged (1.4%), mostly in female LADC patients with no smoking history.40 A statistical analysis of 39 Chinese NSCLC patients with RET-rearranged found that KIF5B-RET was the most common type of fusion (52%), with a PFS of 4.0 months (95% CI: 3.2-4.8) and mOS of 25 months (95% CI: 1.5-48.5), with no significant difference in PFS and OS between the 2 group of patients treated with or without multi-TKIs but not RET-selective inhibitors.83 In another Chinese multicenter study exploring the relationship between RET rearrangement and pemetrexed efficacy in patients with NSCLC, 62 patients with NSCLC with RET-rearranged, 40 of whom received pemetrexed-based first-line chemotherapy compared to other regimens, had a significant difference in mPFS of 9.2 versus 5.2 months (P = .007). The difference in mPFS between the KIF5B-RET rearrangement and non-KIF5B-RET rearrangement groups was not statistically significant. For OS, it was 35.2 versus 22.6 months, respectively, for those who received and didn’t receive pemetrexed-based chemotherapy (P = .052).54

In March 2021, the State Drug Administration of China approved Pralsetinib for the treatment of adult patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC with RET rearrangements who had previously received platinum-containing chemotherapy. This marked the approval of the first and only selective RET inhibitor in China. In June, the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association (CACA) and the Pathology Branch of the Chinese Medical Association jointly released the Expert Consensus on Clinical Testing for RET rearrangements in NSCLC in China. Although Chinese mainland was late in receiving approval for such drugs compared to the United States, there has been relevant therapeutic experience and exploration for the treatment of the drug.

In a pathologic histological analysis of 9431 Chinese NSCLC patients, 167 (1.77%) were found to have concomitant RET rearrangements, with the majority of patients being nonsmoking female LADC patients. The most common forms of fusion were KIF5B-RET (68.3%), CCDC6 (16.8%), and NCOA4 (1.2%). The concordance of result between FISH and NGS in this study was 83.3% (25/30), while the concordance between IHC and NGS was lower at 28.1% (16/57). NGS and FISH assays performed well in identifying RET rearrangement, but IHC was not as sensitive for RET detection.84

A Chinese scholar who reviewed real-world data from 75 patients with RET rearrangement from 2017 to September 2021 showed that 73% (55 of 75) of patients carried the driver gene KIF5B-RET. 15 patients who received Pralsetinib/Selpercatinib had an ORR of 53.3% (8/15) and a PFS of 10.0 months (95% CI: 5.2-14.9), and an additional 15 patients received chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy in the second-line treatment, with 5 (33.3%) achieving objective remission and mPFS of 6.6 months (95% CI: 4.7-8.4), with 1 patient with a PD-L1 TPS of 90% achieving PR after optimal efficacy in first-line treatment with Pembrolizumab and PFS of 5.5 months.59

In addition, Pralsetinib achieved good therapeutic results even in patients with advanced NSCLC after multiline therapy and with rare RET rearrangement double fusion of mutations (ANK3-RET and CCDC6-RET), further suggesting the importance of highly selective targeting of our driver genes.85

In terms of neoadjuvant therapy, Chinese scholars reported the first case in the world in which neoadjuvant therapy with Pralsetinib was applied and achieved success. The patient underwent successful surgery 1 month after the application of targeted therapy and the patient achieved an optimal treatment outcome of PR after neoadjuvant therapy. This encouraging result further suggests that neoadjuvant treatment with Pralsetinib is effective and exciting compared to chemotherapy for patients with driver genes and Pralsetinib has the potential to further expand the indications.86

Meanwhile, the LIBRETTO⁃432 study (NCT04819100) is a phase III clinical study of Selpercatinib adjuvant treatment of patients with early stage RET rearrangement NSCLC, with the primary endpoint of investigator-assessed event-free survival (EFS). The study is an evaluation of adjuvant treatment with Selpercatinib in patients with stages IB-IIIA RET rearrangement-positive NSCLC after radical therapy. The major difference between this study and previous adjuvant-targeted therapies is the inclusion of patients not only after radical resection but also after radical radiotherapy.87 The Chinese study centers were fully enrolled in the trial at the start of the study, and China has already completed the dosing of the first patient worldwide, although it started 6 months later than global research. This may show that the changing role of China in global clinical research has gradually changed from follower to leader.

Conclusions

In the era of precision medicine, the small RET rearrangement-positive population should not be ignored. Although the incidence of RET rearrangement-positive NSCLC is as low as ALK fusion mutation, the specific targeted RET selective inhibitors show the high-efficiency and low-toxicity and can bring long-term survival benefits to such patients.88 With the development of medicine, the diagnosis and treatment mode of lung cancer has gradually changed from a simple pathological classification to a combination of pathological and molecular classification (Figure 1). In clinical practice, it is important to discover the patients with RET rearrangement-positive NSCLC as much as possible to prevent the loss of precise treatment opportunities. It is also critical to actively identify RET rearrangement subtypes and explore potential drug resistance mechanisms. In addition, for postoperative adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies, EGFR-TKIs already have the support of relevant evidence-based medicine, making it possible to “de-chemotherapy”. However, there is still a gap in the exploration of RET rearrangement mutations. The research of targeted drugs for rare gene mutations is in the ascendant, and the research results are worth expecting.

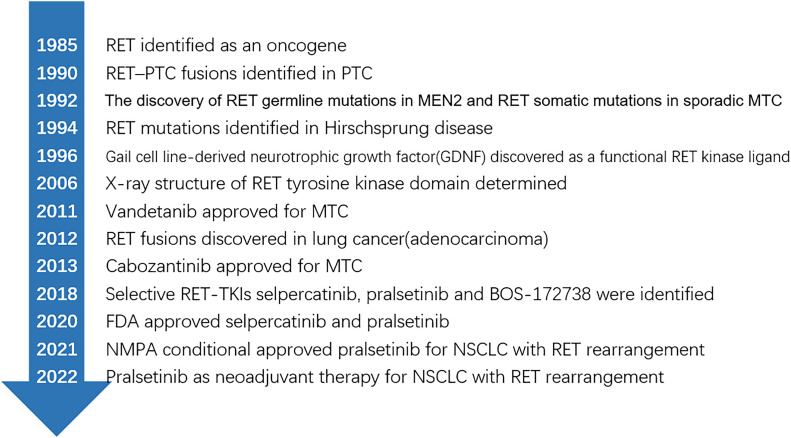

Figure 1.

Identification of rearranged during transfection (RET) proto-oncogene and progress of targeted therapy.

Abbreviations

- ARs

androgen receptors

- ALK

anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- BICR

blinded independent central review

- CACA

Chinese Anti-Cancer Association

- CCDC6

coiled-coil domain-containing protein 6

- CHD

congenital Hirschsprung's disease

- cfDNA

cell-free DNA

- ctDNA

circulating tumor DNA

- C-SCLC

combined small-cell lung cancer

- CSCO

Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology

- DCR

disease control rate

- DOR

duration of response

- EFS

event-free survival

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- FMTC

familial medullary thyroid carcinoma

- GDNF

gail cell line-derived neurotrophic growth factors

- ICIs

immune checkpoint inhibitors

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- IRC

Independent Review Committee

- IARC

International Agency for Research on Cancer

- KIF5B

kinesin family member 5B

- LADC

lung adenocarcinoma

- ORRs

objective response rate

- PD-1

programmed cell death protein 1

- PD-L1

programmed cell death ligand 1

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PPARs

proliferator-activated receptors

- PTC

papillary thyroid carcinoma

- MET

mesenchymal–epithelial transformation factor

- mPFS

median progression-free survival

- MTC

medullary thyroid carcinoma

- mOS

median overall survival

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines

- NCOA4

nuclear receptor coactivator 4

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- NSCLC

non-small-cell lung cancer

- NTRK

neurotrophin receptor kinase

- RET

rearranged during transfection

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- TKI

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- TRAEs

treatment-related adverse events

- VEGFR1

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1

- WCLC

World Conference on Lung Cancer

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iDs: Tao Li https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9038-4794

Ting-Ting Liu https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1725-7748

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer[J] . N Engl J Med . 2018;378(2):113-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solomon BJ, Kim DW, Wu YL, et al. Final overall survival analysis from a study comparing first-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol . 2018;36(22):2251-2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu YL, Herbst RS, Mann H, et al. ADAURA: Phase III, double-blind, randomized study of osimertinib versus placebo in EGFR mutation-positive early-stage NSCLC after complete surgical resection[J]. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19(4):e533-e536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pall G, Gautschi O. Advances in the treatment of RET-fusion-positive lung cancer[J]. Lung Cancer. 2021;156:136-139. Epub 2021 Apr 24. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.04.017. PMID: 33933276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markham A. Selpercatinib: First approval[J]. Drugs. 2020;80(11):1119-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markham A. Pralsetinib: First approval[J]. Drugs. 2020;80(17):1865-1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi M, Ritz J, Cooper GM. Activation of a novel human transforming gene, ret, by DNA rearrangement[J]. Cell. 1985;42(2):581-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salvatore D, Santoro M, Schlumberger M. The importance of the RET gene in thyroid cancer and therapeutic implications[J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(5):296-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li AY, McCusker MG, Russo A, et al. RET fusions in solid tumors[J]. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;81:101911. Epub 2019 Oct 30. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2019.101911. PMID: 31715421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohno T, Tsuta K, Tsuchihara K, et al. RET fusion gene: Translation to personalized lung cancer therapy[J]. Cancer Sci. 2013;104(11):1396-1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altanerová V. Cancers connected with mutations in RET proto-oncogene[J]. Neoplasma. 2001;48(5):325-331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi M, Kawai K, Asai N. Roles of the RET proto-oncogene in cancer and development[J]. JMA J . 2020;3(3):175-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prete A, Borges de Souza P, Censi S, et al. Update on fundamental mechanisms of thyroid cancer[J] . Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:102. 10.3389/fendo.2020.00102. PMID: 32231639; PMCID: PMC7082927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coniac S, Stoian M. Updates in endocrine immune-related adverse events in oncology immunotherapy[J]. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar) . 2021;17(2):286-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belli C, Anand S, Gainor JF, et al. Progresses toward precision medicine in RET-altered solid tumors[J]. Clin Cancer Res . 2020;26(23):6102-6111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subbiah V, Velcheti V, Tuch BB, et al. Selective RET kinase inhibition for patients with RET-altered cancers[J]. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(8):1869-1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romei C, Ciampi R, Elisei R. A comprehensive overview of the role of the RET proto-oncogene in thyroid carcinoma[J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(4):192-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeuchi K, Soda M, Togashi Y, et al. RET, ROS1 and ALK fusions in lung cancer[J]. Nat Med . 2012;18(3):378-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipson D, Capelletti M, Yelensky R, et al. Identification of new ALK and RET gene fusions from colorectal and lung cancer biopsies[J]. Nat Med. 2012;18(3):382-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watanabe S, Takeda M, Otani T, et al. Complete response to selective RET inhibition with selpercatinib (LOXO-292) in a patient with RET fusion-positive breast cancer[J]. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021;5:PO.20.00282. 10.1200/PO.20.00282. PMID: 34036231; PMCID:PMC8140803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santoro M, Moccia M, Federico G, et al. RET gene fusions in malignancies of the thyroid and other tissues[J]. Genes . 2020;11(4):424. 10.3390/genes11040424. PMID: 32326537; PMCID: PMC7230609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staubitz JI, Schad A, Springer E, et al. Novel rearrangements involving the RET gene in papillary thyroid carcinoma[J]. Cancer Genet. 2019;230:13-20. Epub 2018 Nov 13. 10.1016/j.cancergen.2018.11.002. PMID: 30466862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iyama K, Matsuse M, Mitsutake N, et al. Identification of three novel fusion oncogenes, SQSTM1/NTRK3, AFAP1L2/RET, and PPFIBP2/RET, in thyroid cancers of young patients in Fukushima[J]. Thyroid . 2017;27(6):811-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bronte G, Ulivi P, Verlicchi A, et al. Targeting RET-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer: Future prospects[J]. Lung Cancer . 2019;10:27-36. 10.2147/LCTT.S192830. PMID: 30962732; PMCID:PMC6433115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrara R, Auger N, Auclin E, et al. Clinical and translational implications of RET rearrangements in non-small cell lung cancer[J]. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(1):27-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richardson DS, Gujral TS, Peng S, et al. Transcript level modulates the inherent oncogenicity of RET/PTC oncoproteins[J]. Cancer Res. 2009;69(11):4861-4869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulligan LM. RET Revisited: Expanding the oncogenic portfolio[J]. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(3):173–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li P, Yu X, Ge K, et al. Heterogeneous expression and functions of androgen receptor co-factors in primary prostate cancer[J]. Am J Pathol. 2002;161(4):1467-1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ligr M, Li Y, Zou X, et al. Tumor suppressor function of androgen receptor coactivator ARA70alpha in prostate cancer[J]. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(4):1891-1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morandi A, Martin LA, Gao Q, et al. GDNF-RET signaling in ER-positive breast cancers is a key determinant of response and resistance to aromatase inhibitors[J]. Cancer Res. 2013;73(12):3783-3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spanheimer PM, Park JM, Askeland RW, et al. Inhibition of RET increases the efficacy of antiestrogen and is a novel treatment strategy for luminal breast cancer[J]. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(8):2115-2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Platt A, Morten J, Ji Q, et al. A retrospective analysis of RET translocation, gene copy number gain and expression in NSCLC patients treated with vandetanib in four randomized Phase III studies[J]. BMC Cancer. 2015;15::171. 10.1186/s12885-015-1146-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W, Guo L, Liu Y, et al. Potential unreliability of uncommon ALK, ROS1, and RET genomic breakpoints in predicting the efficacy of targeted therapy in NSCLC[J]. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(3):404-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stinchcombe TE. Current management of RET rearranged non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020;12:1758835920928634. 10.1177/1758835920928634. PMID: 32782485; PMCID: PMC7385825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu HA, Suzawa K, Jordan E, et al. Concurrent alterations in EGFR-mutant lung cancers associated with resistance to EGFR kinase inhibitors and characterization of MTOR as a mediator of resistance[J]. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(13):3108-3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCoach CE, Le AT, Gowan K, et al. Resistance mechanisms to targeted therapies in ROS1( + ) and ALK( + ) non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(14):3334-3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shields MD, Hicks JK, Boyle TA, et al. Selpercatinib overcomes CCDC6-RET-mediated resistance to osimertinib[J]. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(3):e15-e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li T, Zhang F, Wu Z, et al. PLEKHM2-ALK: A novel fusion in small-cell lung cancer and durable response to ALK inhibitors[J]. Lung Cancer. 2020;139:146-150. Epub 2019 Nov 6. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.11.002. PMID:31794921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang K, Chen H, Wang Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and molecular patterns of RET-rearranged lung cancer in Chinese patients[J]. Oncol Res. 2019;27(5):575-582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang R, Hu H, Pan Y, et al. RET Fusions define a unique molecular and clinicopathologic subtype of non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(35):4352-4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan AC, Seet A, Lai G, et al. Molecular characterization and clinical outcomes in RET-rearranged NSCLC[J]. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(12):1928-1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beadling C, Wald AI, Warrick A, et al. A multiplexed amplicon approach for detecting gene fusions by next-generation sequencing[J]. J Mol Diagn. 2016;18(2):165-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reeser JW, Martin D, Miya J, et al. Validation of a targeted RNA sequencing assay for kinase fusion detection in solid tumors[J]. J Mol Diagn . 2017;19(5):682-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benayed R, Offin M, Mullaney K, et al. High yield of RNA sequencing for targetable kinase fusions in lung adenocarcinomas with no mitogenic driver alteration detected by DNA sequencing and low tumor mutation burden[J]. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(15):4712-4722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levin JZ, Berger MF, Adiconis X, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of a cancer transcriptome enhances detection of sequence variants and novel fusion transcripts[J]. Genome Biol. 2009;10(10):R115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jenkins S, Yang JC, Ramalingam SS, et al. Plasma ctDNA analysis for detection of the EGFR T790M mutation in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer[J]. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(7):1061-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bernabé R, Hickson N, Wallace A, et al. What do we need to make circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) a routine diagnostic test in lung cancer?[J]. Eur J Cancer . 2017;81:66-73. Epub 2017 Jun 10. 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.04.022. PMID: 28609695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bent A, Kopetz S. Going with the flow: The promise of plasma-only circulating tumor DNA assays[J]. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(20):5449-5451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rich TA, Reckamp KL, Chae YK, et al. Analysis of cell-free DNA from 32,989 advanced cancers reveals novel co-occurring activating RET alterations and oncogenic signaling pathway aberrations[J]. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(19):5832-5842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rolfo C, Mack PC, Scagliotti GV, et al. Liquid biopsy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A statement paper from the IASLC[J]. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(9):1248-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reinert T, Henriksen TV, Christensen E, et al. Analysis of plasma cell-free DNA by ultradeep sequencing in patients with stages I to III colorectal cancer[J]. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(8):1124-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drilon A, Bergagnini I, Delasos L, et al. Clinical outcomes with pemetrexed-based systemic therapies in RET-rearranged lung cancers[J]. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(7):1286-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen T, Pu X, Wang L, et al. Association between RET fusions and efficacy of pemetrexed-based chemotherapy for patients with advanced NSCLC in China: A multicenter retrospective study[J]. Clin Lung Cancer. 2020;21(5):e349-e354. Epub 2020 Feb 10. 10.1016/j.cllc.2020.02.006. PMID: 32143967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lu C, Dong XR, Zhao J, et al. Association of genetic and immuno-characteristics with clinical outcomes in patients with RET-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer: A retrospective multicenter study[J]. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mazieres J, Drilon A, Lusque A, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: Results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry[J]. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(8):1321-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhandari NR, Hess LM, Han Y, et al. Efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. Immunotherapy. 2021;13(11):893-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guisier F, Dubos-Arvis C, Viñas F, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC with BRAF, HER2, or MET mutations or RET translocation: GFPC 01-2018[J]. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(4):628-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meng Y, Yang Y, Fang Y, et al. The treatment status of patients in NSCLC with RET fusion under the prelude of selective RET-TKI application in China: A multicenter retrospective research[J]. Front Oncol. 2022;12:864367. 10.3389/fonc.2022.864367. PMID: 35692799; PMCID: PMC9176213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Drilon A, Rekhtman N, Arcila M, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced RET-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer: An open-label, single-centre, phase 2, single-arm trial[J]. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):1653-1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoh K, Seto T, Satouchi M, et al. Final survival results for the LURET phase II study of vandetanib in previously treated patients with RET-rearranged advanced non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Lung Cancer. 2021;155:40-45. Epub 2021 Mar 10. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.03.002. PMID: 33725547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Solomon BJ, Tan L, Lin JJ, et al. RET Solvent front mutations mediate acquired resistance to selective RET inhibition in RET-driven malignancies[J]. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(4):541-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ancker OV, Wehland M, Bauer J, et al. The adverse effect of hypertension in the treatment of thyroid cancer with multi-kinase inhibitors[J]. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(3):625. 10.3390/ijms18030625. PMID: 28335429; PMCID: PMC5372639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee SH, Lee JK, Ahn MJ, et al. Vandetanib in pretreated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer-harboring RET rearrangement: A phase II clinical trial[J]. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(2):292-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Subbiah V, Berry J, Roxas M, et al. Systemic and CNS activity of the RET inhibitor vandetanib combined with the mTOR inhibitor everolimus in KIF5B-RET re-arranged non-small cell lung cancer with brain metastases[J]. Lung Cancer. 2015;89(1):76-79. Epub 2015 Apr 22. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.04.004. PMID: 25982012; PMCID: PMC4998046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Horiike A, Takeuchi K, Uenami T, et al. Sorafenib treatment for patients with RET fusion-positive non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Lung Cancer. 2016;93:43-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hida T, Velcheti V, Reckamp KL, et al. A phase 2 study of lenvatinib in patients with RET fusion-positive lung adenocarcinoma[J]. Lung Cancer. 2019;138:124-130. Epub 2019 Sep 16. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.09.011. PMID: 31710864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Drilon A, Fu S, Patel MR, et al. A phase I/ib trial of the VEGFR-sparing multikinase RET inhibitor RXDX-105[J]. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(3):384-395. Epub 2018 Nov 28. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0839. PMID: 30487236; PMCID: PMC6397691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ping G, Hui-Min W, Wei-Min W, et al. Sunitinib in pretreated advanced non-small-cell lung carcinoma: A primary result from Asian population[J]. Med Oncol. 2011;28(2):578-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Drilon A, Oxnard GR, Tan D, et al. Efficacy of selpercatinib in RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):813-824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tiedje V, Fagin JA. Therapeutic breakthroughs for metastatic thyroid cancer[J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(2):77-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bradford D, Larkins E, Mushti SL, et al. FDA Approval summary: Selpercatinib for the treatment of lung and thyroid cancers with RET gene mutations or fusions[J]. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(8):2130-2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Solomon BJ, Zhou CC, Drilon A, et al. Phase III study of selpercatinib versus chemotherapy ± pembrolizumab in untreated RET positive non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. Future Oncol. 2021;17(7):763-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lu S, Cheng Y, Huang D, et al. Efficacy and safety of selpercatinib in Chinese patients with advanced RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: A phase II clinical trial (LIBRETTO-321)[J]. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2022;14:17588359221105020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zheng H, Chen ZS, Li J. Selpercatinib for lung and thyroid cancers with RET gene mutations or fusions[J]. Drugs Today (Barc). 2021;57(10):621-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gainor JF, Curigliano G, Kim DW, et al. Pralsetinib for RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (ARROW): A multi-cohort, open-label, phase 1/2 study[J]. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(7):959-969. Epub 2021 Jun 9. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00247-3. PMID: 34118197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Belli C, Penault-Llorca F, Ladanyi M, et al. ESMO Recommendations on the standard methods to detect RET fusions and mutations in daily practice and clinical research[J]. Ann Oncol . 2021;32(3):337-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Subbiah V, Yang D, Velcheti V, et al. State-of-the-art strategies for targeting RET-dependent cancers[J]. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(11):1209-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ackermann CJ, Stock G, Tay R, et al. Targeted therapy for RET-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer: Clinical development and future directions[J]. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:7857-7864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Terzyan SS, Shen T, Liu X, et al. Structural basis of resistance of mutant RET protein-tyrosine kinase to its inhibitors nintedanib and vandetanib[J]. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(27):10428-10437. Epub 2019 May 22. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007682. PMID: 31118272; PMCID: PMC6615680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ding S, Wang R, Peng S, et al. Targeted therapies for RET-fusion cancer: Dilemmas and breakthrough[J]. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;132:110901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lyra J, Vinagre J, Batista R, et al. mTOR activation in medullary thyroid carcinoma with RAS mutation[J]. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;171(5):633-640. Epub 2014 Aug 27. 10.1530/EJE-14-0389. PMID: 25163725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xing P, Yang N, Hu X, et al. The clinical significance of RET gene fusion among Chinese patients with lung cancer[J]. Transl Cancer Res. 2020;9(10):6455-6463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Feng J, Li Y, Wei B, et al. Comprehensive analysis of characteristics, detecting techniques and clinical outcomes of RET-rearranged NSCLCs from real-world practice in China[A]. 其他:Department of Molecular Pathology, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Henan Cancer Hospital;中国医学科学院北京协和医院,2021.

- 85.Meng Y, Li L, Wang H, et al. Pralsetinib for the treatment of a RET-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patient harboring both ANK-RET and CCDC6-RET fusions with coronary heart disease: A case report[J]. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10(8):496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhou N, Li T, Liang M, et al. Use of pralsetinib as neoadjuvant therapy for non-small cell lung cancer patient with RET rearrangement[J]. Front Oncol. 2022;12:848779. 10.3389/fonc.2022.848779. PMID: 35223529; PMCID: PMC8866561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tsuboi M, Goldman JW, Wu YL, et al. LIBRETTO-432, a phase III study of adjuvant selpercatinib or placebo in stage IB-IIIA RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. Future Oncol. 2022;18(28):3133-3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhao W, Choi YL, Song JY, et al. ALK, ROS1 and RET rearrangements in lung squamous cell carcinoma are very rare[J]. Lung Cancer. 2016;94:22-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]