Abstract

Ultrashort echo time (UTE) MRI techniques can be used to image the concentration of water in bones. Particularly, quantitative MRI imaging of collagen-bound water concentration (Cbw) and pore water concentration (Cpw) in cortical bone have been shown as potential biomarkers for bone fracture risk. To investigate the effect of Cbw and Cpw on the evaluation of bone mechanical properties, MRI-based finite element models of cadaver radii were generated with tissue material properties derived from 3D maps of Cbw and Cpw measurements. Three-point bending tests were simulated by means of the finite element method to predict bending properties of the bone and the results were compared with those from direct mechanical testing. The study results demonstrate that these MRI-derived measures of Cbw and Cpw improve the prediction of bone mechanical properties in cadaver radii and have the potential to be useful in assessing patient-specific bone fragility risk.

Keywords: MRI, bone, finite element analysis, bound water, pore water

Introduction

Bone fragility is a widespread problem and current X-ray based diagnostics have not proven effective in predicting who is likely to suffer a fragility fracture (Cosman et al. 2014; Kanis et al. 2001). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown promise to provide complimentary diagnostics of bone fracture risk (Manhard et al. 2017b). In cortical bone, MRI can measure concentrations water bound to collagen (bound water concentration, Cbw) and water inside pore spaces (pore water concentration, Cpw), and these two measures have been shown to correlate with various mechanical properties of cadaveric bone specimens (Horch et al. 2011) and whole bones (Manhard et al. 2016). This study aimed to determine whether MRI-derived Cbw and Cpw information can improve the prediction of mechanical bone properties, beyond what can be determined by structure alone. To this end, finite element (FE) analysis was used to incorporate MRI measurements of Cbw and Cpw along with the bone structure into the evaluation of whole cadaver bone mechanical properties.

Materials and Methods

Thirty-five fresh, frozen cadaveric forearms (elbow to fingertip, Nb = 35) from 29 donors (14 males, 15 females, age 57 to 84, mean 72 ± 8, right and left pairs came from the 6 donors) were obtained from the United Tissue Network (Phoenix, AZ, USA). Each arm was studied using three measurements. First, 3D MRI provided structure and maps of Cbw and Cpw of the cortical region of the radius. Second, mechanical properties of the radius were measured with a three-point bending test. Finally, using MRI to define structure and material properties, FE simulations of the 3-point bending test were performed with the objective of evaluating how Cbw and Cpw relate to whole bone mechanics. Figure 1 presents a summary of the overall experimental plan, and details of each phase of the study are presented below.

Figure 1.

The experiment overview. For the ith bone, i = 1 to Nb, material properties, Ei and Yi, were iteratively adjusted until the root mean square difference between the simulated and experimentally measured force-displacement curves was minimized.

Imaging

After thawing, MRI of each arm was acquired on a Philips Intera Achieva (Best, NL) 3 T scanner using a dStream Flex-M coil for signal reception and the body coil for RF transmission. Similar to previous work, an adiabatic inversion recovery (AIR) prepared ultra-short echo time (UTE) sequence was used to selectively image bound water, and a double adiabatic inversion recovery (DAFP) prepared UTE sequence was used for selective imaging of pore water (Horch et al. 2012; Manhard et al. 2013). All images were acquired with a 3D radial readout to encode a 20 cm × 20 cm × 20 cm field-of-view (FOV) with 1 mm nominal isotropic resolution. The AIR sequence used a 7.8 ms duration, 3.2 kHz bandwidth HS8 adiabatic inversion pulse, inversion time = 85 ms, and a repetition time (TR) = 400 ms. The DAFP sequence used a pair of the same adiabatic pulses and TR = 615 ms. Both AIR and DAFP acquisitions were accelerated by acquiring 16 radial spokes in k-space per repetition, using 115-μs duration hard pulse RF excitations with variable flip angle to generate an equal amplitude of transverse magnetization (initial angle = 12.5° and net effective flip angle = 60°). Conventional 3D UTE images were also acquired for anatomical reference of the bone with TR = 4.8 ms, 70 μs echo time, and a 7° flip angle excitation pulse.

Similar to previous studies (Manhard et al. 2016; Manhard et al. 2017a), UTE images were reconstructed (Johnson and Pipe 2009) based upon measured readout gradient trajectories (Duyn et al. 1998; Harkins et al. 2021), and image intensities were adjusted to account for the receive coil spatial sensitivity (Duyn et al. 1998; Fessler and Sutton 2003). After image reconstruction, Cbw and Cpw maps were calculated using previously presented signal equations (Manhard et al. 2013). These maps were computed in absolute units of concentration (moles of 1H per liter of bone) using signal a reference phantom (10% CuSO4 + H2O/90% D2O), which was included in the FOV. For each bone, the conventional UTE MRI was used to generate a 3D mask of cortical bone, 110 mm in length and centered on the distal-third site. Mean Cbw and Cpw values, ( and , respectively) were computed from within the mask at the central axial slice.

Mechanical testing

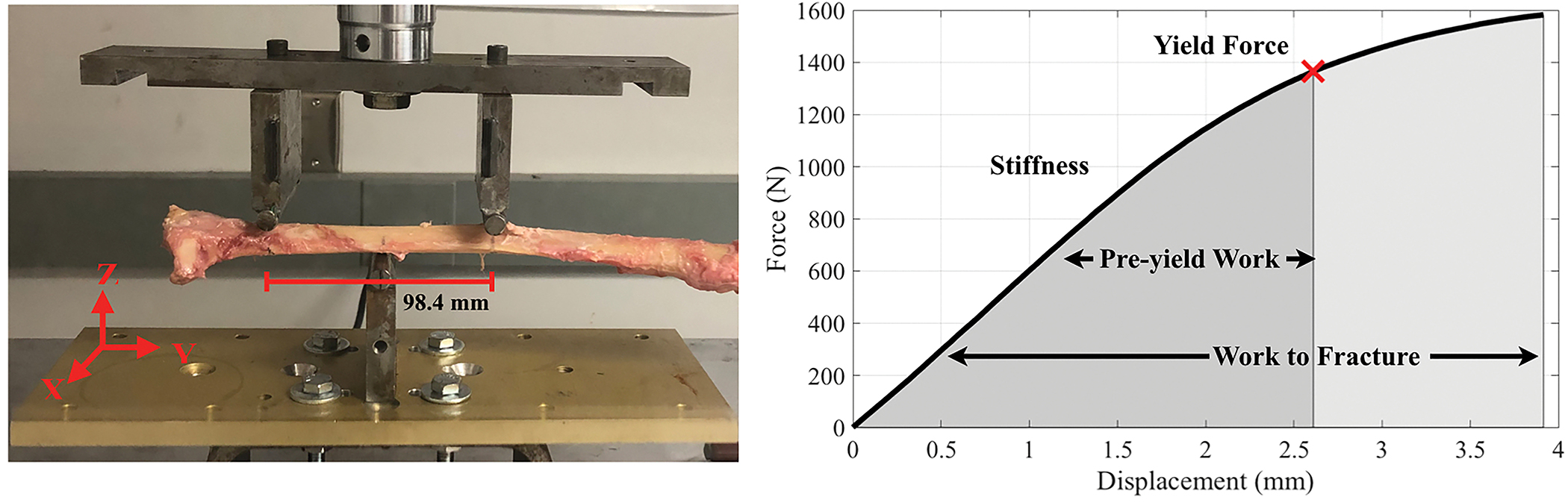

Following MRI, the radii were denuded and subjected to a three-point bending test with a material testing machine (MTS 858 Bionix, Eden Prairie, MN). The distal-third radius site, approximately the middle of the MRI FOV, was loaded at 6.5 mm/min until failure. Each bone was positioned with the anterior surface down and the medial side forward with the span supports equal to 98 mm. The resulting force and displacement data were recorded at 100 Hz with a 14.5 kN load cell and an MTS linear variable displacement transducer, respectively. From the force-displacement data, stiffness, yield force, pre-yield work, and work-to-fracture were calculated, and indicated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Three-point bending test setup (left) and force-displacement curve of a representative radius. From the force-displacement data, stiffness, yield force (15% loss in stiffness), pre-yield work (area under the force-vs.-displacement curve until the yield point), and work-to-fracture (area under the force-vs.- displacement curve until the failure point) were calculated (Manhard et al. 2016). Failure was defined as 5% decrease from the ultimate force.

FE Analysis

Using the 3D bone mask from the UTE MRI and TetGen (Si H. 2015), a first-order tetrahedral mesh of each bone was generated with elemental volume of 0.118 mm3 (i.e., edge length ≈ 1 mm, matching MRI resolution). With this mesh and using FEBioStudio (Maas et al. 2012) and the GIBBON toolbox (Moerman 2018), an FE model was used to simulate the same three-point bending mechanical test described above. The material behavior of bone was implemented with an elastic, perfectly plastic stress-strain model, as defined in the FEBioStudio software. (The material is perfectly elastic until a certain stress and then becomes perfectly plastic, i.e., no addition stress with additional strain.) The elastic regime was defined as isotropic and linear with Young’s modulus (E) and Poisson ratio of 0.3. The onset of the perfectly plastic regime was defined by the von Mises yield stress (Y).

From the simulation, the resulting force, displacement, stress, and strain were recorded at a minimum of twenty time-steps for each node. The global force-displacement data were then generated using the summation of reaction force data from the nodes at which the loading was applied. For each bone, the global force-displacement data from the simulation and mechanical tests were compared from the start of loading until failure point, defined as the mean von Mises equivalent strain along the maximum loading plane exceeding 3%. With this failure criterion, the simulations predicted a failure displacement between the experimental yield displacement and fracture displacement. The experimental and simulated forces were linearly interpolated to a uniformly spaced array of 100 points between the start of loading and ultimate force, and then the root mean square difference between the two was computed (δ).

Within this framework, simulations were repeated until values for E and Y were found that minimized δ, resulting in per-bone estimated material property values, and , for i = 1 to Nb. This was done with a Nelder-Mead simplex search, using initial values of E = 9 GPa and Y = 200 MPa. Across all bones, the minimization was completed in 18 to 41 iterations. In addition, simultaneous simulations across all bones were repeated until a global solution of E and Y were found that minimized the sum of δ from all Nb bones. These values were labeled EA and YA and were used on Case A evaluations—see definition below.

Predicting Mechanical Properties with MRI

First, linear models were defined that related MRI measures of mean bound and pore water concentrations ( and , respectively) to the estimated bone material properties, modulus () and yield stress (),

| (1) |

| (2) |

with i = 1 to Nb. These models were using standard linear regression, providing estimated parameters, and which were subsequently used in cases B and C, below. Second, to test the influences of Cbw and Cpw in predicting whole-bone mechanical test results, the FE simulations were repeated using three different cases to define modulus, E, and yield stress, Y. For each case, the simulated force-displacement curves were used to estimate predicted mechanical properties: stiffness, yield force, and pre-yield work, and work to fracture, as described above. The three cases evaluated were:

No influence of Cbw and Cpw. The modulus and yield stress were spatially homogenous and constant across bones, using the globally optimal parameters, EA and YA.

- Homogeneous influence of Cbw and Cpw. The modulus and yield stress were defined as spatially homogeneous but unique to each bone, based on and . Thus, for the ith bone, case B modulus and yield stress were:

(3)

respectively.(4) - Heterogeneous influence of Cbw and Cpw. The modulus and yield stress were defined as spatially varying maps, based on the Cbw and Cpw maps. Thus, for every FE element of the ith bone, case C modulus and yield stress were:

(5)

respectively.(6)

Results

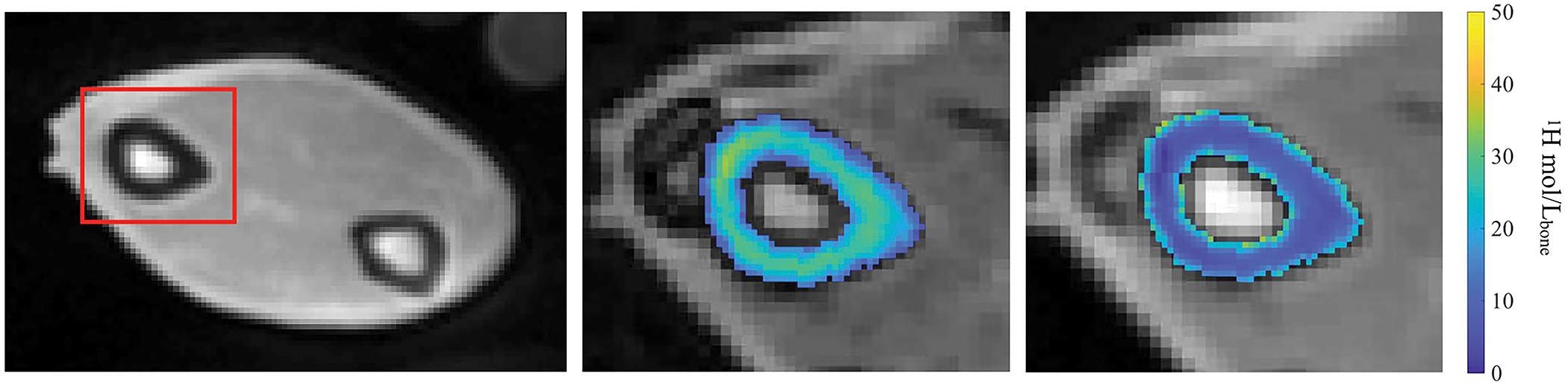

From a representative cadaver arm, cross-sectional UTE, AIR, and DAFP MRI images at the distal-third site are shown in Figure 3. The UTE image (left) was cropped to show the cross-sectional image of the arm and the red box indicates the location of the radius bone. Maps of Cbw and Cpw within the radius are overlaid on the corresponding AIR and DAFP images, respectively. Across all 35 bones, the median ± standard deviation of the mean Cbw and Cpw, calculated at middle slice, were 15.37 ± 4.22 1H mol/Lbone and 14.98 ± 9.34 1H mol/Lbone, respectively.

Figure 3.

MRI images of a representative radius acquired at distal third site. The left image shows the conventional UTE image with red box indicating the radius bone. The middle and right images show the maps of Cbw and Cpw overlaid on the corresponding AIR and DAFP images, respectively.

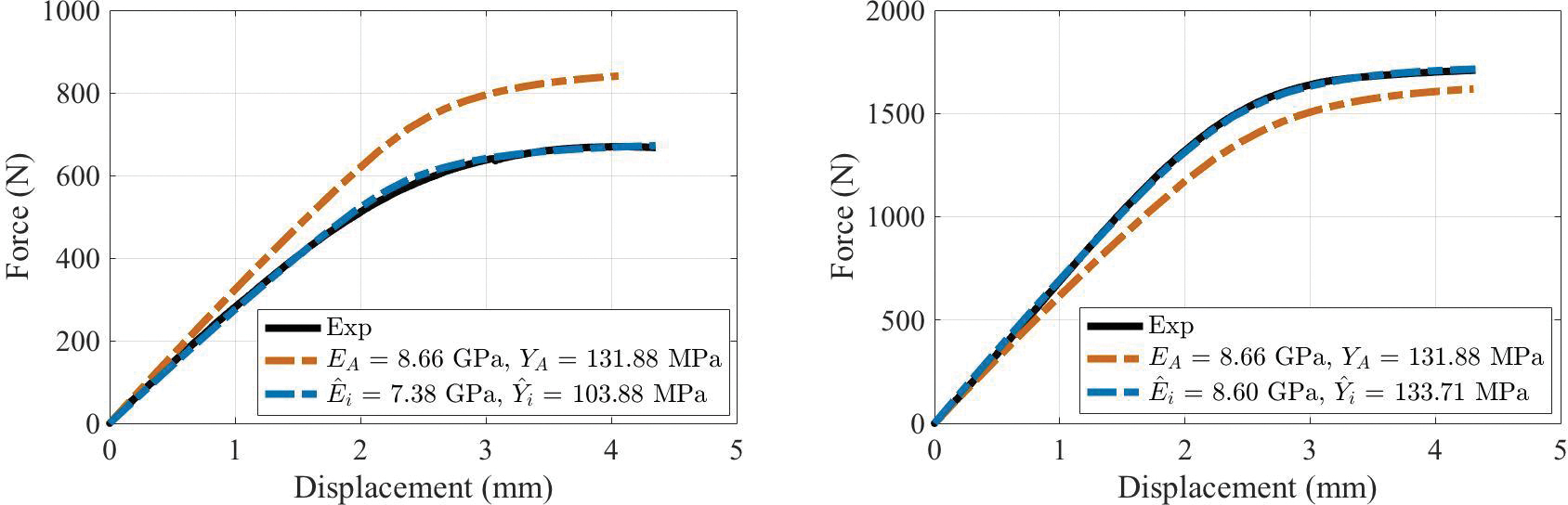

The results of the simulation-derived per-bone estimates of modulus, , and yield stress, , are shown in Figure 4 for two representative bones. Each frame shows the experimental force-vs.-displacement curve (black) as well as the simulation-derived curves generated using the per-bone (blue) and global (orange) estimates of elastic modulus and yield stress. In all cases, the spatially-uniform, per-bone optimized and values resulted in simulated force-displacement curves that closely matched the experimental results with average coefficient of determination, R2 ≈ 0.99 across all samples. The mean ± standard deviation (range) of the estimated and were 9.42 ± 2.13 GPa (5.26 to 14.48 GPa) and 140.72 ± 34.93 MPa (60.87 to 226.97 MPa), respectively. The globally-optimized elastic modulus and yield stress values, EA = 8.66 GPa and YA = 131.88 MPa, respectively (11 iterations), resulted in simulated force-vs.-displacement curves that were qualitatively similar to experimental data with average coefficient of determination, R2 ≈ 0.60. These EA and YA values were used for the case A evaluations.

Figure 4.

Experimental (solid line) and simulated (dashed line) force-displacement curves using (blue) and {EA, YA} (orange) parameters from two representative bones.

The linear models relating imaging measures, and , to and (Eqs 1 and 2) are shown in Figure 5. These models were primarily driven by bound water concentrations and captured approximately half of the variance of and (coefficient of determination, R2 = 0.47 and 0.60, for the models predicting modulus and yield stress, respectively). The fitted model parameters, and are presented in Table 1 and were used to define material properties EB, YB, and maps EC and YC, for the case B and C evaluations, below.

Figure 5.

Correlations of elastic modulus (left) and yield stress (right) with MRI-derived Cbw and Cpw.

Table 1:

Parameters estimation for multiple linear regression model between water concentration measurements and optimized tissue parameters.

| Properties | Coefficient (Variables) | Estimate (Mean ± SE) (Units) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Young’s Modulus (GPa) | a1 (Cbw) | 0.39 ± 0.08 (GPa∙Lbone/mol 1H) | 0.47 |

| a2 (Cpw) | 0.05 ± 0.04 (GPa∙Lbone/mol 1H) | ||

| a3 (Intercept) | 2.06 ± 1.88 (GPa) | ||

|

| |||

| Yield Strength (MPa) | b1 (Cbw) | 6.60 ± 1.17 (GPa Lbone/mol 1H) | 0.60 |

| b2 (Cpw) | 0.15 ± 0.53 (GPa∙Lbone/mol 1H) | ||

| b3 (Intercept) | 29.71 ± 26.74 (MPa) | ||

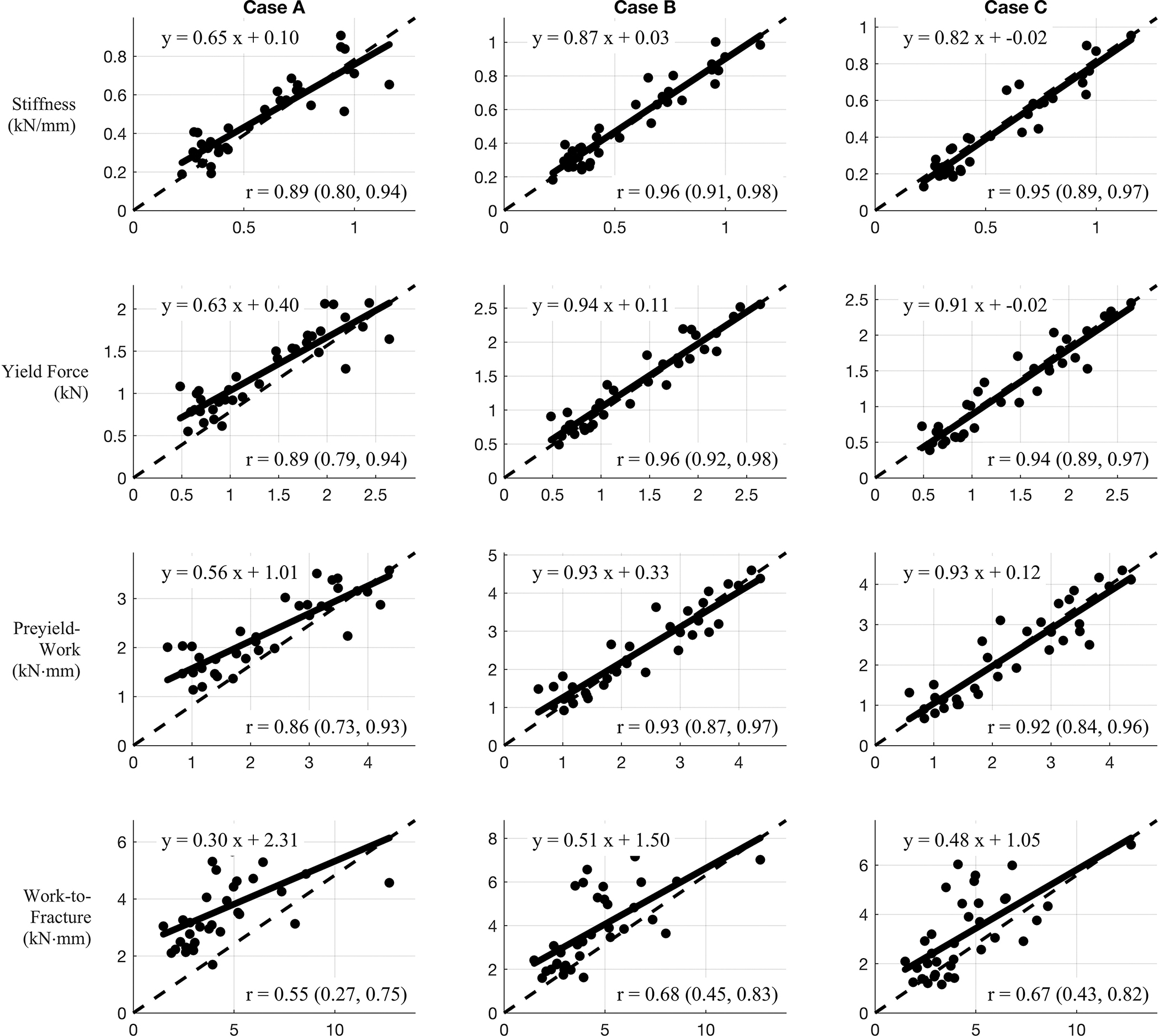

The three cases of simulations are compared in Figures 6 and 7 and Table 2. First, from two representative bones, Figure 6 shows the comparison between experimental force-displacement curve and the simulated curves from cases A, B, and C. Note that in Case C, 4 of the bone models failed to converge at high displacement but were successfully re-run using a neo-hookean nonlinear model (within FEBioStudio) in place of the isotropic elastic model. Subsequent analysis below is reported with and without inclusion of these four simulations.

Figure 6.

Experimental (solid line) and model-based (dashed line) simulated force-displacement curves from case A (orange), case B (green), and case C (blue) of two representative bones.

Figure 7.

Correlations between measured mechanical data (x-axis) and predicted mechanical data (y-axis) of three different models. Case A: Homogeneous tissue properties, Case B: Homogeneous tissue properties derived from Cbw and Cpw, and Case C: Heterogeneous tissue properties derived from Cbw and Cpw.

Table 2:

Linear model and correlation coefficients of mechanical properties between mechanical data and simulation data for three different models.

| Properties | Case | Linear Model Coefficients (with 95% confidence bounds) |

Correlation Coefficient (with 95% confidence bounds) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | Intercept | |||

|

| ||||

| Stiffness (kN/m) | A | 0.65 (0.56, 0.75) | 0.10 (0.04, 0.17) | 0.89 (0.80, 0.94) |

| B | 0.87 (0.79, 0.95) | 0.03 (−0.02, 0.08) | 0.96 (0.91, 0.98) | |

| C | 0.82 (0.74, 0.91) | − 0.02 (−0.07, 0.03) | 0.95 (0.89, 0.97) | |

|

| ||||

| Yield Force (kN) | A | 0.63 (0.54, 0.73) | 0.40 (0.26, 0.54) | 0.89 (0.79, 0.94) |

| B | 0.94 (0.85, 1.02) | 0.11 (−0.02, 0.23) | 0.96 (0.92, 0.98) | |

| C | 0.91 (0.82, 1.01) | − 0.02 (−0.16, 0.12) | 0.94 (0.89, 0.97) | |

|

| ||||

| Pre-yield Work (kNmm) | A | 0.56 (0.46, 0.66) | 1.01 (0.76, 1.26) | 0.86 (0.73, 0.93) |

| B | 0.93 (0.82, 1.03) | 0.33 (−0.07, 0.60) | 0.93 (0.87, 0.97) | |

| C | 0.93 (0.81, 1.04) | 0.12 (−0.18, 0.42) | 0.92 (0.84, 0.96) | |

|

| ||||

| Work to Fracture (kNmm) | A | 0.30 (0.17, 0.44) | 2.31 (1.63, 2.99) | 0.55 (0.27, 0.75) |

| B | 0.51 (0.35, 0.67) | 1.50 (0.69, 2.31) | 0.68 (0.45, 0.83) | |

| C | 0.48 (0.32, 0.63) | 1.05 (0.27, 1.83) | 0.67 (0.43, 0.82) | |

In terms of the four bending properties derived from the force-displacement data, Figure 7 displays the correlations between bending properties from mechanical testing and simulation for the three different cases. Case B and C displayed stronger prediction power for all evaluated bone mechanical properties in comparison to case A. Each frame reports a linear model along with a correlation coefficient (r) (with 95% confidence interval, CI) between predicted (from simulation) and measured bending property. These values along with the CI of the model parameters are summarized in Table 2. In almost all cases, the inclusion of bound and pore water concentrations (cases B and C) resulted in better prediction of measured properties than did predictions based on bone structure alone. Specifically, for all bending properties, the model slope and intercept parameters were closer to unity and zero, respectively, for cases B and C compared to case A. Similarly, the case B and C correlation coefficients were higher than those from case A, although the CIs overlapped in all comparisons. If we exclude the 4 Case C simulations that required the neo-hookean model, none of the correlation coefficients changed by more than 0.02.

Discussion

Image-based FE methods have been used in multiple studies together with computed tomography (Kopperdahl et al. 2014; Ladd et al. 1998; Ramezanzadehkoldeh and Skallerud 2017), or MRI data (Chang et al. 2014; Newitt et al. 2002; Rajapakse et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2013) to predict bone strength. For MRI studies, material properties were typically either assumed as homogeneous (E = 10 GPa) (Newitt et al. 2002), derived from bone volume fraction which requires high-resolution μMRI imaging (E = 15 GPa × BV/TV) (Chang et al. 2014; Rajapakse et al. 2018), or defined as a function of tissue strain (hyperbolic secant of εtissue × 15 GPa) (Zhang et al. 2013). Also, only one study compared FE predictions to experimental measurements, namely compression tests of distal tibia segments (Rajapakse et al. 2018). In the present study, FE simulations derived from MRI images used material properties encoded with matrix and micro-structural information to simulate force-displacement curves of whole radii subjected load-to-failure tests in three-point bending. In doing so, FE predictions of bone strength from MRI scans can be based on both images of structure and material characteristics, namely bound and pore water concentrations, akin to QCT-based FE predictions of bone strength that incorporate relationships between modulus or yield stress and calibrated X-ray attenuation values (Knowles et al. 2016).

Using only anatomical information from MRI and assuming Poisson’s ratio = 0.3, the elastic material properties, modulus and yield stress, were found that resulted in the best prediction of the mechanical tests. These values varied widely across the 35 bones tested (ranges: = 5.26 to 14.48 GPa and = 60.87 to 226.97 MPa) but are in reasonable agreement literature values for cortical bone (11.5 GPa elastic modulus and 114 MPa yield stress (Reilly and Burstein 1975). Measurements specific to whole bone bending properties of the human radius are scarce but are also generally similar. For example, Singh et al. reported mean and standard deviation of elastic modulus and strength from 6 cadaver radii as 3.66 ± 0.78 GPa and 80.31 ± 14.55 MPa, respectively (Singh et al. 2018). This same study also cited bending modulus and strength values of the radial diaphysis from Motoshima (Motoshima 1960) as 15.88 GPa elastic modulus and 211.82 ± 4.9 MPa strength. Thus, the optimal values of modulus and yield stress are in good general agreement with values reported for the radius.

Importantly, the results showed that when using optimal per-bone values, and , the FE simulations closely predicted force-displacement curves of mechanical tests (R2 ≈ 0.99 across all bones). The coefficient of determination dropped by nearly half (R2 = 0.60) when using the globally optimized values (EA = 8.66 GPa and YA =131.88 MPa) for all simulations. This observation indicates that, in addition to macroscopic structure, donor-specific bone material properties were important in determining the whole bone bending behavior (i.e., force vs. displacement). Given this, the subsequent FE simulations were used to determine if these material properties could be derived from MRI measures of bone and pore water concentration.

Our previous studies suggested positive and negative associations between both Cbw and Cpw, respectively, and various mechanical properties of cortical bone as determined by load-to-failure tests of uniform specimens (Granke et al. 2015; Horch et al. 2011). Horch et al. presented relatively strong linear correlations between bound- and pore- water 1H NMR concentrations and flexural modulus and yield stress (Horch et al. 2011). In our subsequent MRI study of cadaveric radii, Cbw and Cpw measurements also showed significant and independent linear relationship with bone bending strength (Manhard et al. 2016). For that study, material properties of whole bone radius, such as bending strength and toughness, were determined using beam theory and μCT-derived section modulus. Consequently, a linear model was chosen to relate these MRI measures to elastic modulus and yield stress (Equations 1 and 2, respectively). Overall, the models captured approximately half of the variance in and across bones and demonstrated that both modulus and strength are strongly dependent on Cbw (see fitted models in Figure 5 and fitted parameters in Table 1). These linear models were then used to compute per-bone values EB,i and YB,i, as well as per-bone maps EC,i and YC,i for repeated FE simulations.

The contribution of pore water concentration to E and Y was low despite the range in Cpw being greater in the present set of cadaveric radii than in our previous study (Manhard et al. 2016). There are several possible explanations for this weak contribution of Cpw to the material properties of cortical bone. Firstly, our previous study in which both Cpw and Cbw significantly contributed to the prediction of bending strength of the radial diaphysis did not use FEA to account for role of bone structure in strength. By accounting for size and shape of each bone in the FE simulations, the importance of Cpw was perhaps diminished. Secondly, although cortical porosity is a known determinant of bone strength (Curry 1990; McCalden et al. 1993; Wachter et al. 2002), its negative correlation with yield stress has been shown to be rather weak (e.g., R2 = 0.22, p=0.004) (Mirzaali et al. 2016). Lastly, higher pore water concentration (higher cortical porosity) does not necessarily translate to weaker bone if the Cpw is dictated by signal from the endosteum. Bone loss in the diaphysis of long bones occurs near the endosteum causing a “transition” zone in which cortical bone appears to be trabecular bone (Zebaze et al. 2010). Loading cadaveric radii in four-point bending to failure and imaging the micro-structure of the diaphysis by high-resolution μCT, Bigelow et al. observed a stronger correlation between pores distributed away from the neutral axis and bending strength than between overall porosity and bending strength (Bigelow et al. 2019). Since the imaging resolution of this study is 1 mm, high Cpw values could also be influenced by bone marrow signal in the endosteum region, especially for bones with a thin cortical shell. The literature values of mean cortical thickness of radius bones (2.51 0.58 mm (Louis et al. 1995) and 5.75 1.07 mm (Webber et al. 2015) also shown that cortical thickness for some bone samples could be relatively close to the imaging resolution. This effect would be smaller in Cbw measurements since bone marrow signals are suppressed in the AIR pulse sequence.

The potential for MRI measures of bound and pore water concentration to inform on the bending properties of bone was assessed by comparing results of three sets of FE simulations. Rather than simply computing the mean squared difference in the force-displacement curves between experiment and simulation, these evaluations compared four bending properties that were computed from the force-displacement data. The results across all cases for defining material properties and all four bending properties are summarized in Figure 7.

Using only structural information from MRI (Case A), the simulations predicted the experimentally measured bending properties well, with correlation coefficient values ranging 0.55 to 0.89. However, this level of predictive power required the use of optimal values of modulus and yield stress found for this particular collection of cadaver bones. Had these simulations relied on literature values, as has been done for some previous FE simulations (Newitt et al. 2002), the predictive power of the simulations would have been much lower. Using the MRI measures of Cbw and Cpw to define the bone material properties (Cases B and C) resulted in generally better prediction of bending properties by simulation. These improved predictions were reflected in both increased correlation coefficient values and models closer to the line of identity. The 95% confidence intervals of the slope and intercept included the values of 1 and 0, respectively, in stiffness for cases B and C (Table 2). The added value of MRI measures was particularly true for the one post-yield property (work-to-fracture) as the correlation coefficient values was increased by up to 23 percent. This may reflect the role of collagen and collagen hydration status in the ability of bone to resist crack propagation.

In comparing Cases B (homogeneous E and Y) and C (inhomogeneous E and Y), there was little or no improvement in predictive power. This result is not surprising, given that a uniform modulus and yield stress optimized for each bone ( and ) resulted in FE simulations that nearly perfectly predicted experimental force-displacement curves. Nonetheless, there were some differences in results between the results of Cases B and C. The bending properties predicted by Case B were generally higher than those from Case C, as apparent from the intercept terms and position of best fit lines relatively to the identity line (Figure 7). These subtle differences are consistent with one previous study of cancellous bone, which found an overestimation of elastic stiffness tensor with a homogeneous model but a generally minor influence of mineral heterogeneity (Gross et al. 2012).

Also, the comparison between Cases B and C may have been limited by the use of mean Cbw and Cpw values in establishing the material model linearly relating E and Y to these MR-derived characteristics. Ideally, the model parameters a1, a2, a3 and b1, b2, b3 could be estimated directly from iterative joint FE simulations of all bones, as was done to find EA and YA. However, the time required for such a computation made it infeasible. To our knowledge, no study has tested the effect of tissue modulus variation on the whole bone modulus and strength of cortical bone; however, apparent modulus of trabecular bone has been found to decrease nonlinearly with increasing coefficient of variation of intra-or-within-specimen tissue modulus (Jaasma et al. 2002). Moreover, several studies have presented the importance of the composition, distribution, and architecture of lamellar tissue in reproducing the micromechanical failure mode of trabecular bone (Hammond et al. 2019; Hammond et al. 2018; Torres et al. 2016; Renders et al. 2008). If the heterogeneity in actual material properties (tissue-level modulus) significantly affects whole bone bending properties, then the estimated and would not be an accurate representation for calculating EC and YC, and the predictive power of mechanical properties for case C could be underestimated. Since the hierarchical organization of bone tissues (e.g., interstitial volume relative to osteonal volume including variance in cement line perimeter, in lamellar variation of modulus that is distinct in transverse and longitudinal directions, and in the unknown distribution of mineralized collagen fibrils relative to surrounding extrafibrillar mineral) confounds the assessment of heterogeneity, the clinical importance of tissue-level heterogeneity to the fracture risk is equivocal (Nyman et al. 2016).

There are also limitations to this study related to the FE modeling. First, in order to reduce the computational burden of the FE simulations, the material was modeled as having isotropic properties, despite cortical bone having anisotropic and asymmetric properties with different tensile and compressive moduli in the longitudinal direction and the transverse direction and different failure strengths in compression and tension, respectively (Morgan et al. 2018). The dependency of mechanical properties of cortical bone on the direction of loading was not accounted for in this study. A previous FE study of cortical bone that employed both orthotropic and isotropic models found differences in resulting stress-strain characteristics between the two to be small (Peng et al. 2006), and so we assume the same to be the case for the present studies.

A second limitation of the model comes from the elastic-perfectly-plastic model, which allowed us to avoid modeling complex post-yield behavior (e.g., damage function). Elastic-perfectly-plastic behavior of the elements will always produce a non-negative increase of force with increasing displacement and no failure point (Figure 6), while some experimental data showed a decrease in force at displacement values beyond the yield or ultimate strength. For this study, the failure point of the model was defined at 3% strain, even though failure strain is not an invariant property. This limited the comparison of post-yield domain between simulation and experiment, preventing the prediction of other bending properties such as ultimate stress and post-yield toughness.

Third, It is worth noting that MRI resolution of 1 mm isotropic presents limits on the ability of FE simulations to fully incorporate the effect of microstructure features of bone. A previous μCT-based FE study of trabecular bone found that mineral heterogeneity can be neglected below ≤ 40 μm (Ramezanzadehkoldeh et al. 2017). We reason that this resolution is much larger for cortical bone, which does not have the same turnover rate and same variation in microstructural architecture (other than porosity being more prevalent near the endosteum). Eberle’s study on finite element analysis of human long bone found the maximum element size to be 1 mm for human femur undergoing compression test (Eberle et al. 2013). According to our results, the whole-bone bending behavior of the radius can be reasonably approximated with mean (case B) or coarse measurements (case C) of material properties. Finer distribution of bound and pore water could possibly improve the predictions; however, in practice, it is difficult to reduce UTE-MRI resolution with a clinical MRI system much below the 1 mm used in this study, and in vivo scans will likely use lower resolution due to scan time constraints.

Fourth, the relatively small sample size might limit the accuracy of the model. For this study, we used all samples to generate the six model parameters which could potentially create bias estimation; however, our primary aim is to compare results of simulations of the three cases. We had also used a 7-fold cross validation method to estimate the model accuracy. The estimated parameters ( and ) have the mean and standard deviation of 0.04 ± 0.04, 0.05 ± 0.03, 1.93 ± 1.11, 6.67 ± 0.58, 0.21 ± 0.41, and 27.50 ± 15.65 respectively. The results showed the average of 4.47% error between the bone material properties across all bone samples for case B model with and without bias estimation. Deep learning architecture is potentially useful tool for generating the model to define relationship between Cbw and Cpw measurements and bone properties with high accuracy. However, larger data base is necessary for this application.

Lastly, the model used in this study represents the bone behavior at room temperature, and further investigation is needed to determine the accurate model parameters for the in vivo case. An increase in temperature was shown to increase the T1 in cortical bone (Han et al., 2015) and could potentially affect the quantification of Cbw and Cpw. In a recent study (Ma et al., 2020), cortical bones’ compressive stress-strain and mechanical properties (porcine) appeared sensitive to temperature (room temperature vs. 38.5 °C), but importantly, temperature did not affect the relationship between the strength of bone and the orientation of the osteons relative to the direction of loading. Performing bending tests of human cortical bone (femur) at 21 °C and at 37 °C (submerged in Ringer’s solution), Sedlin and Hirsch found no significant differences in ultimate stress and energy-to-failure, but they noted that deflection at failure was significantly higher by ~6% when bone was tested at the higher body temperature (Sedlin and Hirsch 1966).

In conclusion, this study demonstrated the potential of UTE MRI to assess fracture risk at sites dominated by cortical bone. The results showed that FE simulations based on MRI-derived maps of macroscopic bone structure was sufficient to predict some whole bone bending properties well, but that these predictions improved with the inclusion of MRI-derived measures of collagen-bound water and pore water concentrations.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering EB014308. We also thank Dr. Kevin M. Moerman (National University of Ireland Galway) for help with GIBBON toolbox application.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in the present study.

Reference

- Bigelow EM, Patton DM, Ward FS, Ciarelli A, Casden M, Clark A, Goulet RW, Morris MD, Schlecht SH, Mandair GS, et al. 2019. External bone size is a key determinant of strength-decline trajectories of aging male radii. J Bone Miner Res. 34(5):825–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang G, Honig S, Brown R, Deniz CM, Egol KA, Babb JS, Regatte RR, Rajapakse CS. 2014. Finite element analysis applied to 3-T MR imaging of proximal femur microarchitecture: Lower bone strength in patients with fragility fractures compared with control subjects. Radiology. 272(2):464–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosman F, De Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, Lindsay R. 2014. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 25(10):2359–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currey J 1990. Physical characteristics affecting the tensile failure properties of compact bone. J Biomech. 23(8):837–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyn JH, Yang Y, Frank JA, Van der Veen JW. 1998. Simple correction method fork-space trajectory deviations in MRI. J Magn Reson. 132(1):150–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberle S, Göttlinger M, & Augat P 2013. An investigation to determine if a single validated density–elasticity relationship can be used for subject specific finite element analyses of human long bones. Med Eng Phys. 35(7):875–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessler J, Sutton B. 2003. Nonuniform Fast Fourier transforms using Min-Max Interpolation. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 51(2):560–574. [Google Scholar]

- Granke M, Makowski AJ, Uppuganti S, Does MD, Nyman JS. 2015. Identifying novel clinical surrogates to assess human bone fracture toughness. J Bone Miner Res. 30(7):1290–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross T, Pahr DH, Peyrin F, Zysset PK. 2012. Mineral heterogeneity has a minor influence on the apparent elastic properties of human cancellous bone: A SRΜCT-based finite element study. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 15(11):1137–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Rieke V, Scott SJ., Ozhinsky E, Salgaonkar VA., Jones PD, Larson PE, Diederich CJ, Krug R 2015. Quantifying temperature-dependent T1 changes in cortical bone using ultrashort echo-time MRI. Magn Reson Med. 74(6):1548–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond MA, Wallace JM, Allen MR, Siegmund T, 2018. Incorporating tissue anisotropy and heterogeneity in finite element models of trabecular bone altered predicted local stress distributions. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 17:605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond MA, Wallace JM, Allen MR, Siegmund T, 2019. Mechanics of linear microcracking in trabecular bone. J. Biomech, 83:34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkins KD, Does MD. 2021. Efficient gradient waveform measurements with variable-prephasing. J Magn Reson. 327:106945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horch RA, Gochberg DF, Nyman JS, Does MD. 2011. Non-invasive predictors of human cortical bone mechanical properties: T2-discriminated 1H NMR compared with high resolution X-ray. PLoS ONE. 6(1):e16359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horch RA, Gochberg DF, Nyman JS, Does MD. 2012. Clinically compatible MRI strategies for discriminating bound and pore water in cortical bone. Magn Reson Med. 68(6):1774–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaasma MJ, Bayraktar HH, Niebur GL, Keaveny TM. 2002. Biomechanical effects of intraspecimen variations in tissue modulus for trabecular bone. J. Biomech. 35(2):237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KO, Pipe JG. 2009. Convolution kernel design and efficient algorithm for sampling density correction. Magn Reson Med. 61(2):439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, De Laet C, Dawson A, Jonsson B. 2001. Ten year probabilities of osteoporotic fractures according to BMD and diagnostic thresholds. Osteoporos Int. 12(12):989–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles NK, Reeves JM, Ferreira LM. 2016. Quantitative computed tomography (QCT) derived bone mineral density (BMD) in Finite Element Studies: A review of the literature. J. Exp. Orthop. 3(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopperdahl DL, Aspelund T, Hoffmann PF, Sigurdsson S, Siggeirsdottir K, Harris TB, Gudnason V, Keaveny TM. 2014. Assessment of incident spine and hip fractures in women and men using finite element analysis of CT scans. J. Bone Miner. Res. 29(3):570–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd AJ, Kinney JH, Haupt DL, Goldstein SA. 1998. Finite-element modeling of trabecular bone: Comparison with mechanical testing and determination of tissue modulus. J. Orthop. 16(5):622–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis O, Willnecker J, Soykens S, Van den Winke P, Osteaux M. 1995. Cortical thickness assessed by peripheral quantitative computed tomography: Accuracy evaluated on radius specimens. Osteoporos Int. 5(6):446–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Qiang Z, Zhao H, Piao H, Ren L 2020. Mechanical properties of cortical bones related to temperature and orientation of Haversian canals. Mater Res Express, 7(1):015408. [Google Scholar]

- Maas SA, Ellis BJ, Ateshian GA, Weiss JA. 2012. FEBio: Finite Elements for Biomechanics. J Biomech Eng. 134(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manhard MK, Harkins KD, Gochberg DF, Nyman JS, Does MD. 2017. 30- second bound and pore water concentration mapping of cortical bone using 2D UTE with optimized half-pulses. Magn Reson Med. 77(3):945–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manhard MK, Horch RA, Harkins KD, Gochberg DF, Nyman JS, Does MD. 2013. Validation of quantitative bound- and pore-water imaging in cortical bone. Magn Reson Med. 71(6):2166–2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manhard MK, Nyman JS, Does MD. 2017. Advances in imaging approaches to Fracture Risk Evaluation. Transl Res. 181:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manhard MK, Uppuganti S, Granke M, Gochberg DF, Nyman JS, Does MD. 2016. MRI-derived bound and pore water concentrations as predictors of fracture resistance. Bone. 87:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCalden RW, McGeough JA, Barker MB, Court-Brown CM. 1993. Age- related changes in the tensile properties of cortical bone. the relative importance of changes in porosity, mineralization, and microstructure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 75(8):1193–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaali MJ, Schwiedrzik JJ, Thaiwichai S, Best JP, Michler J, Zysset PK, Wolfram U. 2016. Mechanical properties of cortical bone and their relationships with age, gender, composition and microindentation properties in the elderly. Bone. 93:196–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerman KM. 2018. Gibbon: The geometry and image-based bioengineering add-on. J. Open Source Softw. 3(22):506. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EF, Unnikrisnan GU, Hussein AI. 2018. Bone mechanical properties in healthy and diseased states. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 20(1):119–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoshima T 1960. Studies on the strength of bending of human long extremity bones. J Kyoto Pref Med Univ. 68:1377–1397. [Google Scholar]

- Newitt DC, Van Rietbergen B, Majumdar S. 2002. Processing and analysis of in vivo high-resolution MR images of trabecular bone for longitudinal studies: Reproducibility of structural measures and micro-finite element analysis derived mechanical properties. Osteoporos Int. 13(4):278–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyman JS, Granke M, Singleton RC, Pharr GM. 2016. Tissue-level mechanical properties of bone contributing to fracture risk. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 14(4):138–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Bai J, Zeng X, Zhou Y. 2006. Comparison of isotropic and orthotropic material property assignments on femoral finite element models under two loading conditions. Med Eng Phys. 28(3):227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajapakse CS, Kobe EA, Batzdorf AS, Hast MW, Wehrli FW. 2018. Accuracy of MRI-based finite element assessment of distal tibia compared to mechanical testing. Bone. 108:71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramezanzadehkoldeh M, Skallerud BH. 2017. MicroCT-based finite element models as a tool for virtual testing of cortical bone. Med Eng Phys. 46:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly DT, Burstein AH. 1975. The elastic and ultimate properties of compact bone tissue. J. Biomech. 8(6):393–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renders GAP, Mulder L, Langenbach GEJ, van Ruijven LJ, van Eijden TMGJ. 2008. Biomechanical effect of mineral heterogeneity in trabecular bone J Biomech 41(13):2793–2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlin ED, Hirsch C 1966. Factors affecting the determination of the physical properties of femoral cortical bone. Acta Orthop Scand, 37(1):29–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si H 2015. TetGen, a Delaunay-based quality tetrahedral mesh generator. ACM Trans Math Softw. 41(2):1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Singh D, Rana A, Jhajhria SK, Garg B, Pandey PM, Kalyanasundaram D. 2018. Experimental assessment of biomechanical properties in human male elbow bone subjected to bending and compression loads. J. Appl. Biomater. 17(2):228080001879381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres AM, Mathenya JB, Keaveny TM, Taylor D, Rimnace CM and Hernández ChJ, 2016. Material heterogeneity in cancellous bone promotes deformation recovery after mechanical failure. PNAS 113(11):2892–2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachter N, Krischak G, Mentzel M, Sarkar M, Ebinger T, Kinzl L, Claes L, Augat P. 2002. Correlation of bone mineral density with strength and microstructural parameters of cortical bone in vitro. Bone. 31(1):90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber T, Patel SP, Pensak M, Fajolu O, Rozental TD, Wolf JM. 2015. Correlation between distal radial cortical thickness and bone mineral density. J Hand Surg Am. 40(3):493–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebaze RM, Ghasem-Zadeh A, Bohte A, Iuliano-Burns S, Mirams M, Price RI, Mackie EJ, Seeman E. 2010. Intracortical remodelling and porosity in the distal radius and post-mortem femurs of women: A cross-sectional study. Lancet. 375(9727):1729–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Magland JF, Rajapakse CS, Bhagat YA, Wehrli FW. 2013. Potential of in vivo MRI-based nonlinear finite-element analysis for the assessment of trabecular bone post-yield properties. Med Phys. 40(5):052303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]