Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is a leading cause of skin and soft tissue infections and systemic infections. Wall teichoic acids (WTAs) are cell wall-anchored glycopolymers that are important for S. aureus nasal colonization, phage-mediated horizontal gene transfer, and antibiotic resistance. WTAs consist of a polymerized ribitol phosphate (RboP) chain that can be glycosylated with N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) by three glycosyltransferases: TarS, TarM, and TarP. TarS and TarP modify WTA with β-linked GlcNAc at the C-4 (β1,4-GlcNAc) and the C-3 position (β1,3-GlcNAc) of the RboP subunit, respectively, whereas TarM modifies WTA with α-linked GlcNAc at the C-4 position (α1,4-GlcNAc). Importantly, these WTA glycosylation patterns impact immune recognition and clearance of S. aureus . Previous studies suggest that tarS is near-universally present within the S. aureus population, whereas a smaller proportion co-contain either tarM or tarP. To gain more insight into the presence and genetic variation of tarS, tarM and tarP in the S. aureus population, we analysed a collection of 25 652 S . aureus genomes within the PubMLST database. Over 99 % of isolates contained tarS. Co-presence of tarS/tarM or tarS/tarP occurred in 37 and 7 % of isolates, respectively, and was associated with specific S. aureus clonal complexes. We also identified 26 isolates (0.1 %) that contained all three glycosyltransferase genes. At sequence level, we identified tar alleles with amino acid substitutions in critical enzymatic residues or with premature stop codons. Several tar variants were expressed in a S. aureus tar-negative strain. Analysis using specific monoclonal antibodies and human langerin showed that WTA glycosylation was severely attenuated or absent. Overall, our data provide a broad overview of the genetic diversity of the three WTA glycosyltransferases in the S. aureus population and the functional consequences for immune recognition.

Keywords: glycosylation, PubMLST, Staphylococcus aureus, tar glycosyltransferases, wall teichoic acid

Data Summary

All data used for analysis are available as open source data at PubMLST S. aureus BIGSdb (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/staphylococcus-aureus).

Impact Statement.

Wall teichoic acids (WTAs) are cell wall-anchored glycopolymers of Staphylococcus aureus that consist of a polymerized ribitol phosphate (RboP) chain that can be glycosylated with N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) by three glycosyltransferases: TarS, TarM, and TarP. Each glycosyltransferase modifies WTA differently, resulting in different WTA glycosylation patterns that impact immune recognition and clearance of S. aureus . To gain more insight into the presence and genetic variation of tarS, tarM, and tarP in the S. aureus population, we analysed a collection of 25 652 S. aureus genomes within the PubMLST database. We found that over 99 % of isolates contained tarS. Co-presence of tarS/tarM or tarS/tarP occurred in 37 and 7 % of isolates, respectively, and was associated with specific S. aureus clonal complexes. At sequence level, we identified tar alleles with amino acid substitutions in critical enzymatic residues or with premature stop codons. Expressing these tar variants in a S. aureus tar-negative strain showed that WTA glycosylation was severely attenuated or absent, emphasizing that gene absence or presence does not always predict phenotype. Studying the genetic presence and diversity of tarS, tarM, and tarP provides more insight into S. aureus WTA glycosylation, which can help in the development of anti- S. aureus preventive or therapeutic interventions such as monoclonal antibodies, phage therapy and vaccines. As such, our study provides a blueprint to dissect and functionally analyse S. aureus genes at a population-wide level.

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a common member within microbiota communities and colonizes approximately 30 % of the human population asymptomatically [1]. However, S. aureus is also a prominent bacterial pathogen in hospital- and community-acquired infections. Infections often start locally, for example in the skin, but if local immune recognition and immune defence fail, bacteria can disseminate and cause systemic infections. Even with timely treatment and clinical management, such infections are associated with high overall disease burden and mortality.

A major component of the S. aureus cell wall is wall teichoic acid (WTA), which is important for nasal colonization, β-lactam resistance and phage-mediated horizontal gene transfer [2, 3]. WTA molecules are composed of 20–40 ribitol phosphate (RboP) subunits that are polymerized into a linear backbone, which is modified with d-alanine and N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) moieties [4]. Currently, three different glycosyltransferases, i.e. TarS, TarM and TarP, are known to glycosylate WTA with GlcNAc [4–9]. GlcNAc is attached to the C-4 hydroxyl group of RboP in either the α- or β-configuration by TarM and TarS, respectively [4, 9]. Similar to TarS, TarP attaches GlcNAc in a β-configuration, but to the C-3 hydroxyl group of RboP [7]. All three enzymes have been characterized both functionally and structurally, providing insight into critical protein residues and features for catalysis [5–8].

The specific WTA GlcNAc modifications greatly influence β-lactam- and phage resistance of S. aureus [2, 4] as well as host–pathogen interactions [10–13]. For instance, the WTA glycan modifications represent dominant antigens in the S. aureus -reactive antibody pool in humans [2, 10, 13]. Most antibodies are directed against β-GlcNAc-modified WTA [10] and not every WTA glycoform may be similar in terms of immunogenicity or as a target for antibody-mediated clearance [7, 10]. With regard to innate immunity, β-GlcNAc-WTA but not α-GlcNAc-WTA is detected by the innate receptor langerin, which is expressed on skin epidermal Langerhans cells (LCs) [11, 12]. These findings indicate that different WTA glycosylation profiles, which depend on the presence and activity of the three known glycosyltransferases, impact S. aureus immune recognition and clearance.

Previous studies suggest that S. aureus near-universally contains tarS, whereas a smaller proportion co-contains either tarM or tarP [1, 7, 14]. Indeed, tarS is part of the S. aureus core genome and clusters with well-studied WTA biosynthesis genes [4]. In contrast, tarM is located elsewhere in the genome and is suggested to be an ancient genetic trait of S. aureus , based on the observation that strains belonging to the very early branching S. aureus bear both tarS and tarM in their genome [2, 14]. It is hypothesized that tarM was lost during S. aureus evolution, resulting in its absence in strains belonging to clonal complex (CC) 5 and CC398 [14]. The most recently identified enzyme, tarP, is encoded on different prophages and its presence seems to be restricted to isolates belonging to CC5 and CC398 [7]. However, an overview on the presence, co-presence and genetic variation of tarS, tarM and tarP within the S. aureus population is currently lacking.

In this study, we dissected the presence and genetic variation of tarS, tarM and tarP in a collection of 25 652 S . aureus genomes that are deposited in the open-access PubMLST database (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/staphylococcus-aureus). We also analysed whether specific combinations or tar allelic variants were associated with specific CCs of S. aureus . Finally, we performed in silico analyses followed by cloning and plasmid-expression of several tar variants in a S. aureus tar-deficient strain to observe the functional effect of tar sequence variation on WTA glycosylation using WTA-specific Fab fragments and human langerin. Overall, our data provide more insight into the genetic diversity of the three WTA GlcNAc-transferases and demonstrates how this natural variation can impact S. aureus immune recognition by both the innate and adaptive immune system. As such, our study provides a blueprint to dissect and functionally analyse S. aureus genes at a population-wide level.

Methods

S. aureus PubMLST database analysis

We analysed the S. aureus genomes deposited in the PubMLST Bacterial Isolate Genome Sequence Database (BIGSdb) [15] to determine the presence and genetic diversity of tar-glycosyltransferases tarS, tarM and tarP (identified as SAUR2940, SAUR2942 and SAUR2941, respectively in the PubMLST S. aureus database). Of the 26 605 genomes in the database (extracted on 8 February 2022), several genomes were excluded from further analysis based on the following criteria. Fifty-seven isolates were excluded since they were suspected to be contaminated or not S. aureus, based on the comments section of the database. Furthermore, 691 isolates were excluded because they contained more than 300 contigs and/or had a N50 contig length of <20 000 bp. Strains were also excluded when a tar-gene was not present within a single contig (n=205). After the exclusion of these strains, 25 652 S . aureus isolates remained for analysis. Allele numbers and nucleotide sequences of the three glycosyltransferases from these isolates were downloaded from the PubMLST S. aureus BIGSdb [15]. To verify that all isolates that contained a tar-gene also had an assigned allele in the database, an additional blast analysis was performed using allele 1 for each of the tar genes and default settings as defined in PubMLST (blastn word size of 11; blastn scoring parameters: reward: 2; penalty: −3; gap open: 5; gap extend: 2) [15]. Isolates that contained a tar-gene sequence but lacked an assigned allele were scanned using default parameters as defined in PubMLST (minimal nucleotide identity of 70 %; minimal alignment of 50 % of allele sequence; blastn word size of 20) [15]. New alleles were assigned and submitted to the database. In the case of a premature stop codon in a tar sequence, the gene was marked as ‘truncated’, and no allele was assigned. Information on the isolates’ sequence type (ST) and CC was also obtained from the PubMLST S. aureus BIGSdb. For some isolates the CC in the database was not defined, and therefore we manually added CC7, CC12, CC25, CC59, CC88, CC130, CC133, CC398 and CC425 based on ST information [16, 17].

Alignments and protein sequence analysis

The nucleotide sequences of all allelic variants of tarS, tarM and tarP were translated to amino acid sequences and aligned using muscle in mega version 11 [18]. We manually analysed critical residues of the enzymes (based on previous studies) [5–8] for amino acid substitutions in or ±1 amino acid next to the critical residues of Tar-enzymes. The effect of the amino acid substitutions on interactions with the acceptor substrate (poly-RboP) or the donor substrate (UDP-GlcNAc) was predicted and visualized using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.5.1 (Schrödinger). During visualization, we continuously chose the rotamer orientation for the mutated residue that had the fewest strains and clashes with other residues in the structure.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

All plasmids and S. aureus strains used for wet-lab experiments in this study are listed in Table S1 (available in the online version of this article). Bacteria were grown overnight in 5 ml tryptic soy broth (TSB; Oxoid) at 37 °C with agitation. For S. aureus strains that were complemented with plasmid, TSB was supplemented with 10 µg ml−1 chloramphenicol (Sigma). Overnight cultures were subcultured the next day in fresh TSB and grown to mid-exponential growth phase, corresponding to an optical density of 0.6–0.7 at 600 nm (OD600).

Generation of complemented RN4220 ΔtarMS strains with tar variants

Shuttle vector RB474 [19] containing full-length copies of tarS, tarM or tarP as inserts (Table S2) were used to recreate naturally occurring amino acid substitutions and premature stop codons in tar-glycosyltransferases [4, 7, 9]. Nucleotide substitutions were generated using either a QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent) or the required nucleotide sequence was ordered as gBlock (IDT). Used primers are listed in Table S3. Plasmids containing sequences of tarS, tarM or tarP were amplified in Escherichia coli DC10b [20] or E. coli XL-1 and transformed into electrocompetent S. aureus RN4220 ΔtarMS [3] through electroporation with a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser II (2.0 kV, 600 Ω, 10 µF). After recovery, bacteria were plated on tryptic soy agar (TSA) plates supplemented with 10 µg ml−1 chloramphenicol to select plasmid-complemented colonies. The presence of tarS, tarM or tarP was confirmed by PCR analysis using tar gene-specific primers, and nucleotide sequences of the constructs were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Analysis of WTA glycosylation using monoclonal Fab fragments and human langerin-FITC

The enzymatic activity of the tar-variants was assessed by analysing WTA glycosylation using WTA-specific Fab fragments [12]. Bacteria were grown to mid-exponential growth phase, collected by centrifugation (4000 rpm, 8 min, 4 °C) and resuspended at an OD600 of 0.4 (∼1×108 c.f.u. ml–1) in PBS (pH 7) with 0.1 % BSA (Sigma). Bacteria (1.25×106 c.f.u.) were incubated with 3.3 µg ml−1 monoclonal Fab fragments (pre-diluted in PBS 0.1 % BSA) specific to β-GlcNAc (clone 4497) or α−1,4-GlcNAc (clone 4461) WTA, respectively [12]. After washing, bacteria were incubated with a goat F(ab′)2 anti-human Kappa-Alexa Fluor 647 (pre-diluted in PBS 0.1 % BSA; 2.5 µg ml−1, Southern Biotech #2062–31) to detect bound Fab fragments. Bacteria were washed and fixed in PBS with 1 % paraformaldehyde, and analysed by flow cytometry on a BD FACSCanto II Flow Cytometer (BD Bioscience). Per sample, 10 000 gated events were collected and fluorescence was expressed as the geometric mean. Additionally, bacterial binding to recombinant FITC-labelled human langerin (kindly provided by Prof. C. Rademacher, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria) was assessed as previously described [11]. Briefly, bacteria were grown to mid-exponential phase, collected and resuspended at an OD600 of 0.4 in TSM buffer [2.4 gl–1 Tris (Sigma-Aldrich), 8.77 gl–1 NaCl (Merck), 294 mg l−1 CaCl2(H2O)2 (Merck), 294 mg l−1 MgCl2(H2O)6 (Merck), containing 0.1 % BSA (Sigma), pH 7]. Next, bacteria were incubated with shaking for 30 min at 37 °C with 20 µg ml−1 FITC-labelled human langerin-extracellular domain (ECD) constructs (referred to as langerin-FITC). Finally, bacteria were washed once with TSM 0.1 % BSA, fixed in 1 % paraformaldehyde in PBS and analysed by flow cytometry as described above.

Statistical analysis

Flow cytometry data were analysed using FlowJo 10 (FlowJo). Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism 9.1.0 (GraphPad Software) with a Chi-Square Goodness of Fit test or a one-way ANOVA followed by a Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. The P-values are depicted in the figures or mentioned in the caption, and P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

TarS is present in >99% of all S. aureus isolates

Analysis of 25 652 S . aureus genomes demonstrated that over 99 % of isolates contained tarS, with 36.7 and 6.6 % of isolates co-containing tarM (n=9 404) or tarP (n=1 702), respectively (Table 1). We also found 26 isolates (0.10 %) that contained all three glycosyltransferase genes (Table 1). Overall, to 186 isolates no tarS alleles could be assigned in the following combinations: to 67 isolates (0.26 %) no tar alleles could be assigned, to 58 isolates (0.23 %) only a tarP allele could be assigned, to 56 isolates (0.22 %) only a tarM allele could be assigned, and to five isolates (0.019 %) both tarP and tarM alleles could be assigned (Table 1). Further analysis of these strains lacking a tarS allele identified an incomplete ORF for tarS in 165 out of 186 isolates (88.7 %) due to the presence of a premature stop codon. We also found premature stop codons in tarM (n=106) and tarP (n=2) sequences. Isolates with premature stop codons in specific tar genes are indicated as ‘truncated’ in Table 1.

Table 1.

Presence of tarS, tarM and tarP in 25652 S. aureus isolates

|

tar genotype |

Isolates (n) |

Percentage of total |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

tarS |

14 334 |

55.9 |

|

|

tarS + truncated tarM |

98 |

||

|

tarS + truncated tarP |

2 |

||

|

tarS only |

14 234 |

||

|

tarS + tarM |

9404 |

36.7 |

|

|

tarS + tarP |

1702 |

6.6 |

|

|

tarS + tarP + truncated tarM |

4 |

||

|

tarS + tarP |

1698 |

||

|

No tar alleles assigned |

67 |

0.26 |

|

|

truncated tarS |

57 |

||

|

truncated tarM |

4 |

||

|

No tar genes |

6 |

||

|

tarP |

58 |

0.23 |

|

|

tarP + truncated tarS |

58 |

||

|

tarM |

56 |

0.22 |

|

|

tarM + truncated tarS |

45 |

||

|

tarM only |

11 |

||

|

tarS + tarM + tarP |

26 |

0.1 |

|

|

tarM + tarP |

5 |

0.02 |

|

|

tarP + tarM + truncated tarS |

5 |

||

|

Total |

25 652 |

100 |

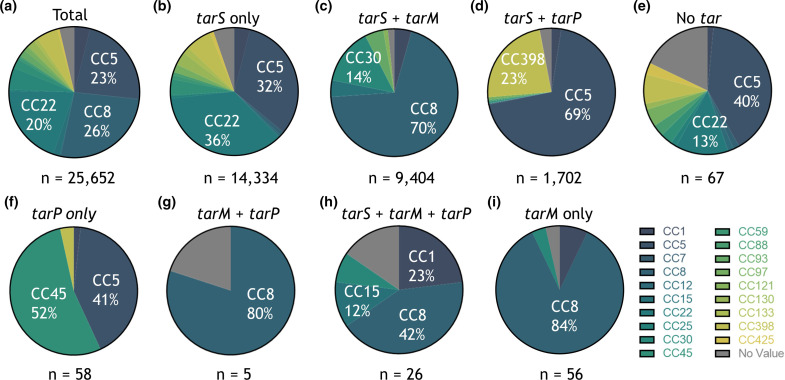

Presence of tar-glycosyltransferases is linked to S. aureus CCs

Next, we analysed whether tar genotype was associated with specific CCs of S. aureus . The most prevalent CCs in the database were CC8 (26 %), CC5 (23 %) and CC22 (20 %) (Fig. 1a), which are all CCs associated with human disease and include methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains [17, 21–23]. Besides being a successful human pathogenic lineage, CC5 is also often found in poultry infections [16, 24]. Other livestock- and animal-associated CCs that were present in the database include CC97, CC130, CC133, CC398, and CC425 [16, 17, 22, 24]. Of the isolates that only contained a complete tarS gene, 36 % belonged to CC22 and 32 % to CC5 (Fig. 1b). Overall, the tarS/tarM combination was predominantly found in isolates belonging to CC8 (Fig. 1c), even when tarP (Fig. 1g, h) or a truncated version of the tarS gene was present (Fig. 1i). In total, tarM was found in seven different CCs (Table S4). For isolates that contain tarS and tarP, nearly all belonged to CC5 (69 %) or CC398 (23 %) as previously described [7] (Fig. 1d). Yet, tarP was also identified in at least 11 additional CCs (Table S4). Interestingly, of the 58 isolates that only contained a complete tarP gene, 52 % belonged to CC45 (Fig. 1f), whereas this CC represented only 0.4 % of the tarS/tarP-containing isolates.

Fig. 1.

The tar genotype is linked to S. aureus clonal complexes. (a) Distribution of CCs for isolates within the PubMLST database on the extraction date. Only CCs that comprise >10 % of isolates are indicated. Colour coding of CCs is shown in the key on the right. (b–i) S. aureus CC distribution is shown for each tar genotype indicated as in (a). The difference between the CC distribution of each tar genotype compared to the total CC distribution was statistically significant for all tar genotypes (P<0.0001), except for (g) tarM+tarP (P=0.89).

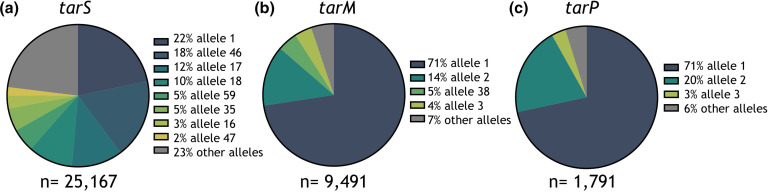

Tar alleles and CC distribution

Based on nucleotide sequence, 536 alleles (coding for 408 unique ORFs) were identified for tarS within the PubMLST S. aureus database, and eight alleles (coding for six unique ORFs) comprised 77 % of all tarS nucleotide sequences (Fig. 2a). The number of alleles was much smaller for tarM with 180 nucleotide sequences coding for 143 unique ORFs, and tarP with only 28 alleles coding for 19 unique ORFs. For these genes, allele 1 was most frequently found, representing 71 % of all tarM-sequences (Fig. 2b) and 71 % of all tarP-sequences (Fig. 2c). All CCs, except tarS CC1 and 8, were characterized by the presence of a single dominant allele of tar-glycosyltransferases (Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Allelic variants of tarS, tarM and tarP in the PubMLST S. aureus collection. (a) Representation of the dominant tarS alleles within the S. aureus isolates of the PubMLST database. Only alleles that cover >1 % of all sequences are displayed individually, while the remaining minor alleles are grouped (grey). The total number of alleles (based on nucleotide sequence) identified for tarS was 536. (b) Same as in (a) but for tarM; the total number of alleles was n=180. (c) Same as in (a) but for tarP; the total number of alleles was n=28.

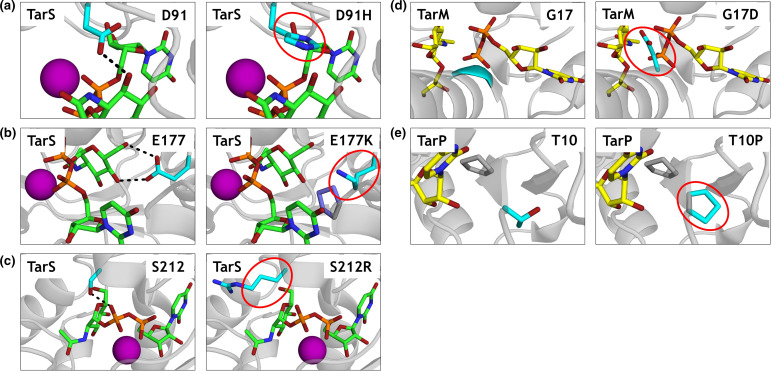

Amino acid substitutions in critical residues of Tar-glycosyltransferases

We identified several tar alleles with a naturally occurring amino acid substitution in a critical residue of the enzyme, based on information from the published crystal structures [6–8]. Overall, these alleles were identified in 32 isolates (0.12 %) of the analysed S. aureus genomes. The amino acid changes in these variants and the function assigned to these residues are listed in Table 2. Fig. 3 visualizes the amino acid substitutions and their predicted effect on molecular interactions in PyMOL. D91 is part of the DxD motif in TarS, which is directly involved in the interaction with UDP-GlcNAc [6] (depicted as a black dashed line; Fig. 3a). Substitution of an acidic aspartate for a basic histidine, which also has a bulkier side chain, is predicted to affect UDP-GlcNAc binding (Fig. 3a). TarS E177 makes contact with the C4-OH and C6-OH of the UDP-GlcNAc moiety [6] (black dashed line; Fig. 3b) and supports orientation of D178 (base catalyst). Consequently, the substitution of E177 to K177 is likely to conflict with P71 (slate; Fig. 3b) in addition to a change from a positively to a negatively charged residue. Moreover, the distance of the terminal primary amine group to UDP-GlcNAc C4-OH and C6-OH becomes 4.5 Å (compared to 2.7 and 3.0 Å of the E177 carboxy group to UDP-GlcNAc C4-OH and C6-OH, respectively), which may hamper sufficient hydrogen bonding (Fig. 3b). A third mutation in tarS results in substitution of S212 to R212 (Fig. 3c). TarS S212 coordinates the β-phosphate of the donor substrate UDP-GlcNAc and is positioned in close proximity to both the donor and acceptor substrate binding sites [6]. During the amino acid substitution (S212R) visualization in PyMOL, we placed several rotamers that did not conflict with TarS structure (Fig. 3c). However, all these rotamers point to the spaces between the two sulphates (yellow; Fig. S2) which might indicate the phosphate binding sites of poly-RboP and therefore may interfere with binding of the acceptor substrate. Furthermore, the coordination of the β-phosphate might be lost as arginine is too long to facilitate this (Fig. 3c). For TarM, the backbone nitrogen atom of G17 coordinates the α-phosphate of UDP-GlcNAc [8]. Consequently, the substitution of G17 to D17 is predicted to affect the interaction of TarM with UDP-GlcNAc as there appears to be little space for the aspartate side chain (Fig. 3d). In TarP, no amino acid substitutions of critical residues were identified, but we did identify an amino acid substitution (T10P) next to a critical residue (F11). F11 stabilizes the uracil moiety of UDP with its aromatic side chain and interacts with the backbone carbonyl of the ribose moiety [7], and mutation of the neighbouring amino acid may affect this interaction (Fig. 3e). Moreover, T10P forms a proline–proline peptide bond with P9, and this diproline segment is even more restricted in its conformational arrangement compared to a single proline (Fig. 3e).

Table 2.

Naturally occurring amino acid substitutions in tarS, tarM and tarP with function of the original residue

|

tar gene |

Substitution |

Isolates (n) |

Function of the residue |

|---|---|---|---|

|

tarS |

D91H |

14 |

Interaction with C3-OH of GlcNAc [6] |

|

E177K |

6 |

Interaction with C4-OH and C6-OH of GlcNAc [6] |

|

|

S212R |

3 |

Coordinates β-phosphate of UDP-GlcNAc [6] |

|

|

tarM |

G17D |

2 |

Interaction with α-phosphate of the UDP-GlcNAc [8] |

|

tarP |

T10P |

7 |

F11 is important for GlcNAc interaction [7] |

Fig. 3.

PyMOL visualizations of the effect of naturally occurring amino acid substitutions on molecular interactions within Tar-enzymes. (a) TarS is shown in grey cartoon presentation (PDB code 5TZE). The donor substrate UDP-GlcNAc (green) and the residues of interest: unaltered (left) and the substitution (right, circled red), both in cyan, are all displayed in stick form. Black dashed line indicates an interaction with UDP-GlcNAc. The Mn2+ ion coordinating the pyrophosphate of UDP is presented as a sphere in magenta. (b) In the E177K mutation (right) the conflicting residue P71 is displayed in stick form (slate). (c) TarS, S212 and S212R are displayed as in (a). (d) TarM is shown in cartoon presentation in grey (PDB code 4X7R). UDP and α-glyceryl-GlcNAc are displayed in stick form (yellow). The remaining residues are coloured as in (a). (e) TarP, T10 and T10P are shown as in (d) with P9 (grey) as a stick model (PDB code 6H4M).

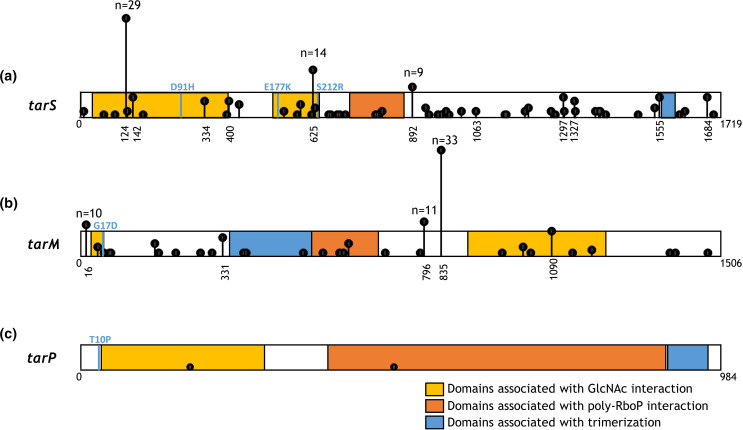

Premature stop codons found in tar-glycosyltransferase genes

Next, we wanted to predict the impact of the naturally occurring premature stop codons (indicated as truncated in Table 1). Therefore, we visualized the location of the stop codons in 2D-scaled models of tar-glycosyltransferases based on previously published enzyme structures [5–8] (Fig. 4)]. TarS (1719 nt) contains two domains that are important for GlcNAc interaction (nt 28–393 and 529–636; yellow) and a poly-RboP interaction domain (nt 742–888; red). Furthermore, TarS contains two residues that are associated with trimerization (nt 1561–1563 and 1594–1596; blue). Certain premature stop codon positions were found in five or more (up to 29) different isolates (Fig. 4a). A similar schematic overview is shown for tarM (Fig. 4b) and tarP (Fig. 4c). Premature stop codons in tarM (1506 nt) were identified in 106 isolates (Fig. 4b). For tarP (984 nt), only two isolates contained a premature stop codon (Fig. 4c). Overall, premature stop codons were found across the entire length of tarS and tarM genes and may affect enzymatic functionality depending on their position within the enzyme.

Fig. 4.

Tar-glycosyltransferase genes depicted as scaled-2D models with nucleotide position of premature stop codons. (a) Scaled 2D representation of tarS (nt 1719) containing two domains important for the GlcNAc interaction (nt 28–393 and 529–636; yellow), a poly-RboP interaction domain (nt 742–888; orange) and two residues associated with trimerization (nt 1561–1563 and 1594–1596; blue). Premature stop codons were identified in 165 isolates and are indicated by the vertical black lines that show position and frequency. For premature stop codons that were present in >4 isolates, the nucleotide position is shown, and for >8 the exact number of isolates is indicated. Amino acid substitutions are depicted in light blue. (b) tarM (1506 nt) contains two residues at the start (nt 49–54; yellow) and domain (nt 910–1233; yellow) that are important in the GlcNAc interaction. Domain 349–540 (blue) contains the HUB domain (formerly known as DUF1975) associated with TarM trimerization. Directly adjacent is the poly-RboP interaction domain (nt 543–699; orange). Premature stop codons (n=106 isolates) are indicated as in (a). (c) tarP (984 nt) contains a domain associated with the GlcNAc interaction (nt 31–285; yellow) followed by a poly-RboP interaction domain (385-789; orange). Domain 916–978 (blue) is associated with trimerization of the enzyme. Premature stop codons (n=2 isolates) are indicated as in (a).

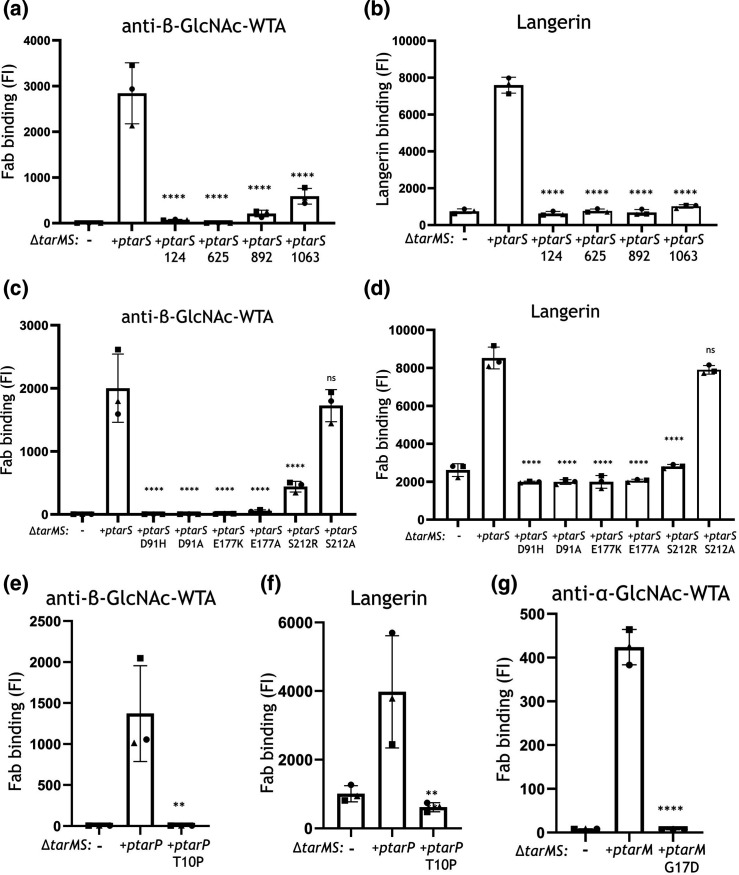

Amino acid substitutions and premature stop codons hamper S. aureus immune recognition by antibodies and langerin

The functional effect of naturally occurring amino acid substitutions and premature stop codons in tar-glycosyltransferases on WTA-GlcNAc decoration was assessed by expressing these tarS, tarM and tarP variants in a S. aureus mutant lacking WTA glycosylation (ΔtarMS). As a read-out of WTA glycosylation, we used specific Fab fragments against β-GlcNAc-WTA (clone 4497) and α−1,4-GlcNAc-WTA (clone 4461) [12]. Furthermore, we recently identified that β-GlcNAc-WTA is specifically detected by the human innate receptor langerin [11]. Therefore, we also determined the bacterial binding of the tar variants by langerin-FITC. For TarS, we tested the effect of a premature stop codon on nucleotide positions 124, 625, 892 and 1063 (Fig. 4a). Overall, β-GlcNAcylation of WTA is significantly (P<0.0001) decreased in all four premature stop codon variants of TarS compared to wild-type (WT) TarS but to varying extent. Premature stop codons on nucleotide positions 124 and 625 abrogated interaction with β-GlcNAc-specific Fab fragments and langerin (Fig. 5a, b). Closer to the C-terminus of TarS, stop codons at nucleotide positions 892 and 1063 severely hampered TarS function but still showed some residual activity, as β-GlcNAcylated WTA was still detectable with β-GlcNAc-specific Fab fragments (Fig. 5a). This level of glycosylation was insufficient for binding to langerin (Fig. 5b). Next, we analysed the effect of amino acid substitutions D91H, E177K and S212R in TarS and control mutations that were previously reported to attenuate TarS enzymatic activity in vitro [6]: D91A, E177A and S212A. Amino acid substitutions D91H and E177K in TarS completely abolished decoration of WTA with β-GlcNAc, similar to their controls D91A and E177A, as demonstrated by completely abrogated Fab binding (Fig. 5c, P<0.0001) and langerin binding (Fig. 5d, P<0.0001) compared to TarS WT (Fig. 5d). Of note, amino acid substitution S212R also significantly (P<0.0001) reduced WTA β-GlcNAcylation and thereby immune recognition (Fig. 5c, d). Interestingly, the control substitution S212A showed normal functionality similar to WT TarS. TarP substitution T10P significantly (P<0.01) reduced WTA β-GlcNAcylation as well as langerin binding (P<0.01) compared to WT TarP (Fig. 5e, f). Lastly, WTA α-GlcNAcylation by TarM was completely abolished by the G17D amino acid substitution (P<0.0001) compared to WT TarM (Fig. 5g). In conclusion, we showed that naturally occurring premature stop codons and amino acid substitutions can strongly diminish WTA GlcNAcylation, thereby reducing immune recognition by innate and the adaptive immune components.

Fig. 5.

Impact of amino acid substitutions and premature stopcodons in TarS, TarM and TarP on S. aureus immune recognition. Binding of (a, c, e) monoclonal Fab fragments specific to β-GlcNAc-WTA (4497) and (b, d, f) human recombinant langerin-FITC to S. aureus RN4220 ∆tarMS complemented with plasmid-expressed WT tarS or premature stop codon tarS (a, b), S. aureus RN4220 ∆tarMS complemented with plasmid-expressed WT tarS or amino acid substitution tarS variants (c, d), or S. aureus RN4220 ∆tarMS complemented with plasmid-expressed WT tarP or amino acid substitution tarP variant (e, f). (g) Binding of Fab fragments specific to α-GlcNAc-WTA to S. aureus ∆tarMS complemented with plasmid-expressed WT tarM or amino acid substitution tarM variant. Data are depicted as geometric mean fluorescence intensity (FI) of three individually displayed biological replicates +standard deviation and were compared to plasmid-expressed WT enzyme: **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001.

Discussion

GlcNAc decoration of S. aureus WTA by glycosyltransferases TarS, TarM and TarP is important for human nasal colonization, β-lactam resistance, phage-mediated horizontal gene transfer and immune recognition [1, 3, 4, 11, 12]. Functional and structural analysis of S. aureus Tar-enzymes has been performed using a select number of strains and may not be representative of the entire S. aureus population. By analysing 25 652 S . aureus genomes deposited in the PubMLST database, we confirmed that virtually all S. aureus isolates express tarS and that 37 and 7 % of isolates co-contain tarM and tarP, respectively. Co-presence of tarS/tarM or tarS/tarP correlated with specific S. aureus CCs. Moreover, we found a small number of tar sequences with natural amino acid substitutions in critical residues of the enzymes or with premature stop codons. By expressing these genes in a tarMS-deficient strain, we demonstrated that these genetic variants are severely attenuated in their enzymatic activity in vivo, thereby hampering immune recognition of S. aureus by innate and adaptive immune molecules.

Previous work on the presence of tar-glycosyltransferases only analysed strain collections containing up to ∼100 isolates using PCR [2, 7, 14, 25, 26]. In this study, we analysed 25 652 S . aureus genomes to obtain a more comprehensive overview of the distribution and genomic variability of the tar-glycosyltransferases across the S. aureus population. The PubMLST database contained isolates from 19 different CCs of human as well as animal origin, although there is clear skewing towards human clinical isolates. The lack of metadata for many of the deposited genomes does not allow for a complete determination of their origin. Overall, the broad number of species and diversity of CCs renders PubMLST an important tool for S. aureus research on the presence and genetic variation of specific genes at the population level.

The presence of tarP, which is encoded on three different prophages [7], was previously reported to be restricted to CC5 and CC3987. However, we also identified tarP in a small number of isolates from CC1, CC7, CC12, CC45, CC59, CC88, CC97 and CC425, and even in tarM-associated CC8. This may suggest that tarP is present on more, at present unknown, phages, or that the host range of tarP-containing phages is broader than currently known.

We found that the presence of tar genes as well as sequence (alleles) was associated with specific CCs of S. aureus . Most CCs contained a dominant allele for each of the tar genes. Since some S. aureus CCs display host tropism, these data may suggest that tar genes have co-evolved and adapted towards the host. However, as the tar genes encode glycosyltransferases that already glycosylate WTA intracellularly, the protein itself is not exposed to the host. Therefore, it may also be that most CCs have a dominant allele for the tar genes because of the closely related nature of the isolates belonging to a particular CC. Whether host adaptation plays a role in the presence and sequence of tar genes remains to be elucidated.

Overall, our analysis showed that the tar-enzymes are highly conserved within the S. aureus population and only a small proportion of the analysed genome sequences contained premature stop codons or critical amino acid substitutions. This highlights the importance of WTA glycosylation for S. aureus . Indeed, glycosylation of WTA is needed for the horizontal gene transfer of S. aureus [3], nasal colonization [1] and β-lactam resistance (independent of mecA or other β-lactam resistance-associated genes) [4]. These examples are indicative of why nearly all S. aureus isolates contain functional glycosyltransferases, especially tarS, and explains the high degree of sequence conservation among the isolates investigated.

Nevertheless, some isolates contained amino acid substitutions in critical residues of the enzymes or premature stop codons, resulting in proteins without or with strongly impaired enzymatic activity. Unfortunately, due to lack of metadata (e.g. provenance, host origin or clinical information) it is hard to determine what kind of host factors and/or genetic mechanisms of S. aureus may have contributed to the introduction of these inactivating genetic changes. An overview of the CC distribution (Fig. S4) shows no clear association to a specific ST or CC.

In addition to gene presence and sequence, environmental conditions also affect WTA glycosylation[25]. Indeed, glycosylation by TarM and TarP is dominant over TarS during in vitro culture [7, 14]. For TarM this might be explained by a higher inherent enzymatic activity [6], whereas for TarP this may be due to a higher affinity for RboP compared to TarS [7]. Furthermore, tar genes may be transcriptionally regulated; tarM expression is increased during oxidative stress, probably due to activation of the two-component GraRS regulon [27]. In contrast, S. aureus shifts towards TarS glycosylation at the expense of TarM/TarP WTA glycosylation during in vivo murine infection models and under high salt conditions [25]. Consequently, the presence of one or more tar genes (identified by PCR or genome sequencing) does not provide complete information on WTA glycosylation in a particular isolate. Overall, strain-specific WTA glycosylation will depend on a specific gene sequence in combination with environmentally dependent gene expression and can only be assessed by direct staining methods such as specific Fab fragments.

We investigated the effect of specific genetic mutations on the enzymatic functionality by expressing these variants in a tarMS-deficient S. aureus strain. This analysis confirmed reduced or abolished activity for several specific amino acid substitutions and premature stop codons in TarS, TarM and TarP. In addition to these naturally occurring amino acid substitutions, we included amino acid substitutions in TarS (D91A, E177A and S212A) that were previously reported to attenuate TarS enzymatic activity in vitro [6]. However, in our FACS experiments using live S. aureus bacteria, we observed no significant differences in levels of β-glycosylated WTA with the S212A mutation compared to WT TarS, indicating that TarS enzymatic activity was similar to WT TarS. This may suggest that results for TarS enzymatic activity obtained in vitro, in which solely enzyme and substrate are present, are not always predictive for WTA β-glycosylation in live bacteria. However, the reason for this discrepancy remains to be elucidated.

The effect of amino acid substitutions and stop codons on WTA glycosylation in live S. aureus was assessed with Fab fragments and recombinant FITC-labelled human langerin. Using this system, we could focus solely on the interaction of the antibody or langerin with the WTA-GlcNAc modifications without theF interference of additional molecular interactions as would occur in a cell-based model system. Consequently, it allowed us to more precisely determine the functional consequence of the potentially altered level of WTA glycosylation. Moreover, we have previously shown that langerin engagement by S. aureus affects interaction with and downstream responses of langerin-expressing cells such as in vitro-generated LCs. Therefore, the experiments using recombinant langerin serve as a proxy for downstream immunological processes in LCs [11, 12]. Finally, it should be noted that we only used the S. aureus RN4220 strain, which naturally contains tarS and tarM [2], and effects may not be identical in other S. aureus strains.

In conclusion, tar glycosyltransferases are highly conserved and very abundant. In particular, tarS was found to be present in >99 % of S. aureus strains. We show that there are few exceptions in which tar genes seem present but contain amino acid substitutions or premature stop codons, and for these isolates we show that tar genotype is not necessarily equal to tar phenotype and that thereby immune recognition is hampered. Studying the genetic presence and diversity of tarS, tarM and tarP provides more insight into S. aureus WTA glycosylation, which can help in the development of anti- S. aureus preventive or therapeutic interventions such as monoclonal antibodies, phage therapy and vaccines.

Supplementary Data

Funding information

This work was supported by the Vici (09150181910001) research programme to N.M.v.S. and S.M.T., which is financed by the Dutch Research Council (NWO). This study also made use of the S. aureus PubMLST database (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/staphylococcus-aureus), which is funded by the Wellcome Trust.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Carla J. C. de Haas and Dr A. Robin Temming for the production of the monoclonal Fab fragments.

Author contributions

Lab experiments: S.M.T., K.S. Data curation: S.M.T., Y.P. Software: S.L.V. Conceptualization: N.M.v.S., Y.P., T.S. Funding acquisition: N.M.v.S., T.S. Supervision: N.M.v.S., Y.P. Visualization: S.M.T., S.L.V. Writing – original draft: S.M.T. Writing – review and editing: N.M.v.S., Y.P., S.L.V.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest for the submitted work.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CC, clonal complex; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; LC, Langerhans cell; RpoP, ribitol phosphate; ST, sequence type; WTA, wall teichoic acid.

Four supplementary figures and four supplementary tables are available in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Winstel V, Kuhner P, Salomon F, Larsen J, Skov R, et al. Wall teichoic acid glycosylation governs Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization. mBio. 2015;6 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00632-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winstel V, Xia G, Peschel A. Pathways and roles of wall teichoic acid glycosylation in Staphylococcus aureus . Int J Med Microbiol. 2014;304:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winstel V, Liang C, Sanchez-Carballo P, Steglich M, Munar M, et al. Wall teichoic acid structure governs horizontal gene transfer between major bacterial pathogens. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2345. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown S, Xia G, Luhachack LG, Campbell J, Meredith TC, et al. Methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus requires glycosylated wall teichoic acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18909–18914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209126109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobhanifar S, Worrall LJ, Gruninger RJ, Wasney GA, Blaukopf M, et al. Structure and mechanism of Staphylococcus aureus tarm, the wall teichoic acid alpha-glycosyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E576–85. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418084112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sobhanifar S, Worrall LJ, King DT, Wasney GA, Baumann L, et al. Structure and mechanism of Staphylococcus aureus TarS, the wall teichoic acid β-glycosyltransferase involved in methicillin resistance. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:12. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerlach D, Guo Y, De Castro C, Kim S-H, Schlatterer K, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus alters cell wall glycosylation to evade immunity. Nature. 2018;563:705–709. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0730-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koç C, Gerlach D, Beck S, Peschel A, Xia G, et al. Structural and enzymatic analysis of TarM glycosyltransferase from Staphylococcus aureus reveals an oligomeric protein specific for the glycosylation of wall teichoic acid. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:9874–9885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.619924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia G, Maier L, Sanchez-Carballo P, Li M, Otto M, et al. Glycosylation of wall teichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus by TarM . J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13405–13415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.096172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Dalen R, Molendijk MM, Ali S, van Kessel KPM, Aerts P, et al. Do not discard Staphylococcus aureus WTA as a vaccine antigen. Nature. 2019;572:E1–E2. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Dalen R, De La Cruz Diaz JS, Rumpret M, Fuchsberger FF, van Teijlingen NH, et al. Langerhans cells sense Staphylococcus aureus wall teichoic acid through langerin to induce inflammatory responses. mBio. 2019;10 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00330-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendriks A, van Dalen R, Ali S, Gerlach D, van der Marel GA, et al. Impact of glycan linkage to Staphylococcus aureus wall teichoic acid on langerin recognition and langerhans cell activation. ACS Infect Dis. 2021;7:624–635. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehar SM, Pillow T, Xu M, Staben L, Kajihara KK, et al. Novel antibody-antibiotic conjugate eliminates intracellular S. aureus . Nature. 2015;527:323–328. doi: 10.1038/nature16057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X, Gerlach D, Du X, Larsen J, Stegger M, et al. An accessory wall teichoic acid glycosyltransferase protects Staphylococcus aureus from the lytic activity of Podoviridae . Sci Rep. 2015;5:17219. doi: 10.1038/srep17219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jolley KA, Bray JE, Maiden MCJ. Open-access bacterial population genomics: bigsdb software, the Pubmlst.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:124. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzgerald JR. Livestock-associated Staphylococcus aureus: origin, evolution and public health threat. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuny C, Wieler LH, Witte W. Livestock-associated MRSA:the impact on humans. Antibiotics (Basel) 2015;4:521–543. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics4040521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38:3022–3027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brückner R. A series of shuttle vectors for Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli . Gene. 1992;122:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90048-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monk IR, Shah IM, Xu M, Tan MW, Foster TJ. Transforming the untransformable: application of direct transformation to manipulate genetically Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis . mBio. 2012;3:e00277-11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00277-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feil EJ, Cooper JE, Grundmann H, Robinson DA, Enright MC, et al. How clonal is Staphylococcus aureus? J Bacteriol. 2003;185:3307–3316. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.11.3307-3316.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aires-de-Sousa M. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among animals: current overview. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCarthy AJ, Lindsay JA. Staphylococcus aureus innate immune evasion is lineage-specific: a bioinfomatics study. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;19:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richardson EJ, Bacigalupe R, Harrison EM, Weinert LA, Lycett S, et al. Gene exchange drives the ecological success of a multi-host bacterial pathogen. Nat Ecol Evol. 2018;2:1468–1478. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0617-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mistretta N, Brossaud M, Telles F, Sanchez V, Talaga P, et al. Glycosylation of Staphylococcus aureus cell wall teichoic acid is influenced by environmental conditions. Sci Rep. 2019;9:3212. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39929-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong M, Zhao J, Huang T, Wang W, Wang L, et al. Molecular characteristics, virulence gene and wall teichoic acid glycosyltransferase profiles of Staphylococcus aureus: a multicenter study in China. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:2013. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.02013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falord M, Mäder U, Hiron A, Débarbouillé M, Msadek T. Investigation of the Staphylococcus aureus GraSR regulon reveals novel links to virulence, stress response and cell wall signal transduction pathways. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.