Abstract

Infant rats primed during the first week of life with soluble antigen displayed adult-equivalent levels of T-helper 2 (Th2)-dependent immunological memory development as revealed by production of secondary immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibody responses to subsequent challenge, but in contrast to adults failed to prime for Th1-dependent IgG2b responses. We demonstrate that this Th2 bias in immune function can be redressed by oral administration to neonates of a bacterial extract (Broncho-Vaxom OM-85) comprising lyophilized fractions of several common respiratory tract bacterial pathogens. Animals given OM-85 displayed a selective upregulation in primary and secondary IgG2b responses, accompanied by increased gamma interferon and decreased interleukin-4 production (both antigen specific and polyclonal), and increased capacity for development of Th1-dependent delayed hypersensitivity to the challenge antigen. We hypothesize that the bacterial extract functions via enhancement of the process of postnatal maturation of Th1 function, which is normally driven by stimuli from the gastrointestinal commensal microflora.

During the preweaning period, the immature immune system is faced with antigenic challenges that are qualitatively and quantitatively different from those encountered during fetal life. In particular, it must learn to discriminate between antigens on pathogenic microorganisms and trivial antigens from domestic animals and plant sources (e.g., danders and pollens), and it must also develop the capacity to respond in a fashion that is qualitatively and quantitatively appropriate to these different types of challenges.

Failure to develop such immune competence in a timely fashion after birth confers increased risk of development of a number of diseases. For example, it is well recognized that transient maturational deficiencies in immune and inflammatory functions predispose infant animals and humans to infections (42). Therefore, interest in the concept that similar deficiencies may predispose toward allergic sensitization against environmental allergens and development of some autoimmune diseases (16, 19) is growing. The precise nature of these maturational deficiencies remains to be determined. However, a common feature appears to be an imbalance between the T-helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 arms of the cellular immune response (e.g., see references 1, 17, 27, and 33).

As a result of a series of regulatory mechanisms that selectively dampen aspects of Th1 function, such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production (18, 41), the fetal immune system appears constitutively biased toward Th2 function, and this imbalance is not usually redressed until biological weaning. Antigen challenge during this period evokes relatively low-level immune responses, which prime selectively for Th2 immunity (3–5, 35), and the relative deficiency in Th1 memory generation can be partially corrected by the use of potent Th1-selective adjuvants (4).

Accumulating evidence suggests that the normal postnatal maturation of immune competence, and in particular the selective postnatal upregulation of Th1 functions, is driven by contact with microbial stimuli, especially signals provided by the commensal flora of the gastrointestinal tract (16, 38). There is increasing interest in the potential therapeutic use of such immunostimulatory stimuli, especially in relation to immunocompromised subjects, who are at increased risk of mucosal infections. There is a particular need for the development of safe and effective immunostimulants for use in immunocompromised children, but there is currently little clinical or experimental information on the utility and mechanism of action of such agents in early postnatal life. The present study examines an animal model designed to systematically address this issue.

We report below on a rat model to study potential methods of boosting the development of humoral and cellular immunity to antigen challenge during the early postnatal period. We have utilized an oral bacterial extract (Broncho-Vaxom OM-85) derived from a mixture of heat-killed respiratory pathogens, which has previously been used in a number of clinical and experimental settings. These include studies of immunostimulation in normal adult experimental animals (7, 8) and double-blind multicenter clinical trials with humans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (12, 30). The principal end points employed for the present study are production of immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2b subclass antibodies, which in the rat are respectively dependent upon Th2 versus Th1 cytokines (14, 36). Our findings confirm earlier reports indicating that immunization in the neonatal period selectively primes for production of Th2-dependent IgG subclass antibodies and further demonstrate that oral administration of the bacterial extract OM-85 circumvents this Th2 bias via selective upregulation of Th1-dependent IgG subclass production. Furthermore, this switch toward Th1 immunity is accompanied by increases in antigen-specific and polyclonal lymphoproliferation and IFN-γ production in vitro and development of antigen-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Inbred PVG.RT7b rats were bred free of common rat pathogens in house at the TVW Telethon Institute for Child Health Research and housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions. Newborn rat pups within 24 h of birth and 8- to 12-week-old adult male rats were used.

Immunization procedures.

Rats were anesthetized under ether and administered primary immunization with ovalbumin (OVA; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) intraperitoneally (i.p), or combined with incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA; Flow Laboratories, Sydney, Australia) subcutaneously (s.c) on an approximate dose-per-body-weight basis. (The i.p. route was avoided for IFA, because this adjuvant can cause prolonged peritonitis.) Newborns were given 25 μg of OVA, and adults were given 100 μg. An antigen challenge was given 28 days after immunization containing 100 μg of OVA in PBS alone (i.p.) or combined with IFA, complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA; Flow Laboratories) s.c., or aluminum hydroxide (AH; Wyeth Amphojel) i.p.

Oral delivery of OM-85 and placebo.

OM-85 (Broncho-Vaxom; OM Pharma, Geneva, Switzerland) is a lyophilized extract of eight common respiratory pathogens (Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus viridans, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella ozaenae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Moraxella catarrhalis), currently in use in many countries as an oral immunostimulant. OM-85 and placebo (lyophilized extract vehicle) were dissolved in sterile water to 400 mg/ml and delivered by mouth to newborn rats at 1 μl per g of body weight. Feeding was provided for 14 consecutive days and then every second day until day 28.

Media and reagents.

Cell isolation procedures were performed in ice-cold PBS supplemented with 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA; CSL, Melbourne, Australia) and 0.5 g each of CaCl2 and MgCl2 per ml (DAB/BSA). The tissue culture medium used was RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Life Technologies) supplemented with 2 g of sodium bicarbonate per liter and 2 mM l-glutamine, 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME; Sigma), and antibiotics, as well as 5% fetal calf serum (FCS; CSL).

OVA-specific IgG subclass analysis.

OVA-specific IgG subclass serum antibodies were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with Maxisorp microtiter plates (Nunc) coated overnight at 4°C with 10 μg of OVA per ml in PBS to 50 μl/well. The wells were blocked with 2% FCS in PBS; serum samples were added and serially diluted in a mixture of 1% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20 (Sigma) in PBS (PBS-Tween-BSA) and incubated with shaking for 2 h at room temperature. Each subsequent antibody was added after being washed three times in PBS–0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-Tween), diluted to the appropriate predetermined concentration in PBS-Tween, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Bound IgG subclasses were detected with biotin-conjugated rabbit anti-rat IgG1 and IgG2b monoclonal antibodies (MAb) (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) followed by a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and then horseradish peroxidase substrate (K-Blue; Neogen, Lexington, Ky.). The color reaction was stopped after 10 min by the addition of 25 μl of 1 M H3PO4, and the optical density at 450 nm was assessed. The concentration of each IgG subclass was determined by comparison with standard curves run in parallel, generated by coating plates with dilutions of purified rat IgG1 and IgG2b isotype standards (PharMingen), followed by detection via the system described above. The IgG subclass titers of test sera were determined by reference to the rat IgG isotype standard curves with the use of the Assay Zap software package for Apple Macintosh (Biosoft, Ferguson, Mo.). The limits of detection of both subclasses are 1 ng/ml.

Cell preparations.

Spleens, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), and pooled iliac and inguinal lymph nodes (I+I) were collected in ice-cold DAB/BSA. Spleens were perfused with DAB/BSA with a bent needle, all tissues were minced with scalpel blades, and clumps were pushed through wire mesh and washed in RPMI–5% FCS. Adult splenic erythrocytes (RBC) were lysed with 0.83% (wt/vol) NH4Cl, and newborn RBC were lysed with a lysis buffer containing 0.15 M NH4Cl, 0.001 M KHCO3, and 0.1 mM EDTA (3). Cell debris and clumps were removed by rapid filtration through prewetted cotton wool columns and collected in RPMI–5% FCS for cell culture.

T-cell proliferation and cytokine assays.

Single-cell suspensions of spleens, pooled iliac and inguinal lymph nodes, and mesenteric lymph nodes were prepared 2 weeks after primary immunization and OM-85 or placebo feeding or for the analysis of recall responses at 1, 2, or 4 weeks after antigen challenge. Cells were incubated in 96-well tissue culture plates (Nunc) at 8 × 105 cells/well in 200-μl volumes at 37°C in RPMI–5% FCS supplemented with 2-ME and containing 100 μg of OVA per ml. For T-cell-receptor (TCR) and CD28 stimulation of T cells, mouse anti-rat TCR MAb (R73) (21) at 10 μg/ml and control MAb (mouse anti-human C3b inactivator; OX21) (20) were captured in wells precoated overnight at 40°C with 40 μg of sheep anti-mouse Ig per ml. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 1% normal mouse serum (NMS), and splenocytes were added at 4 × 105 cells/well in 100 μl followed by 10 μl of mouse anti-rat CD28 MAb (JJ319) tissue culture supernatant (39). Control wells contained bound anti-human C3b inactivator MAb (OX21) and anti-rat CD28 MAb. Medium was added to a final volume of 200 μl, and the culture was incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 72 h, cell proliferation was assessed by the addition of 0.5 μCi of [3H]thymidine for the last 18 h of culture. Results are expressed as mean cpm ± standard errors for triplicate wells and as stimulation ratios.

At the 24-h time point, culture supernatants were taken for analysis of bioactive rat interleukin-4 (IL-4) by a bioassay using the upregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II on splenic B cells with slight modifications of a previously described method (37). Briefly, adult rat spleens were plated in 50 μl (5 × 105 cells) per microwell. One hundred microliters of test tissue culture supernatants was added in triplicate, and the volume was brought up to a final concentration of 200 μl with 50 μl of either medium or the rat IL-4-neutralizing MAb OX81 (28) at a final IgG concentration of approximately 100 μg/ml to monitor assay specificity. To those wells containing supernatants from cultures stimulated with concanavalin A (ConA), 10 μl of 200-mg/ml α-methyl-d-mannoside (grade III; Sigma) was added to neutralize residual ConA. Serial dilutions of recombinant rat IL-4 obtained as tissue culture supernatant (104 U/ml) from a transfected CHO cell line (28) were prepared in parallel with the test wells. The culture was incubated for 40 h at 37°C, and the cells were labeled for flow cytometry. Briefly, B cells were labeled with 200 μl of mouse anti-rat Ig κ chain (OX12) (22). Binding of mouse MAb was detected with a goat anti-mouse IgG-phycoerythrin (GAM-PE) conjugate (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). MHC class II expression was marked with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated OX6 (29). Isotype controls were used as TCS (OX21) or as IgG1-FITC conjugate (Dako). Bioassay responder cells were analyzed for surface MHC class II expression by flow cytometry with a FACscan (Becton Dickinson, Oxford, United Kingdom) by gating on OX12+ cells and collecting data based on the mean flourescence intensity (MFI) of OX6+ B cells. Results are expressed as arbitrary units (AU)/ml, with 1 AU defined as the concentration of IL-4 that gives 50% of maximal induction of MHC class II on B cells, as assessed by flow cytometry. The limits of detection in the assay are 0.01 AU/ml.

Rat IFN-γ protein was measured in 48-h supernatants by ELISA as previously described (37). Briefly, microwells were coated overnight with the MAb DB-1 (specific for rat IFN-γ) (40) at 10 μg/ml in PBS. The next day, the plates were washed three times with PBS, and nonspecific binding sites were blocked by 1% BSA in PBS. Purified rat IFN-γ standard (Biosource International, Becton Dickinson) was diluted to 200 U/ml in PBS with 5% FCS. Next, a serial dilution standard curve was prepared and mixtures were incubated in parallel with diluted and undiluted test tissue culture supernatants (50 μl/well) for 2 h followed sequentially by rabbit anti-rat IFN-γ polyclonal antibody (Biosource) and a goat anti-rabbit Ig-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antiserum (Becton Dickinson, PharMingen). The optical density at 450 nm was determined after addition of the TMB substrate for 15 min, and the color reaction was stopped with 25 μl of 1 M H3PO4. The IFN-γ content of test wells was determined by reference to the rat IFN-γ standard curve by using the Assay Zap software package for Apple Macintosh (Biosoft). Values are expressed as units per milliliter of IFN-γ. The limit of detection in the assay is 0.5 U/ml.

Skin testing for DTH.

Eight-week-old rats immunized neonatally with OVA in IFA, fed OM-85 or placebo, and challenged with OVA in PBS at 4 weeks of age or unimmunized, age-matched (8 weeks old) control rats received an intradermal (i.d.) injection of 20 μg of OVA in 10 μl of PBS or PBS alone in the left and right ears, respectively. Ear swelling was measured after 24 h with a micrometer, and the increments (10−2 mm) were obtained by subtracting values for the thickness of the PBS ear from the test ear. Untouched animals with untouched ears were included to establish background variation.

Statistics.

Statistical comparisons of mean values were performed with the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test for unpaired samples by using the StatView software package (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

RESULTS

Primary and secondary IgG subclass antibody responses in newborn versus adult rats.

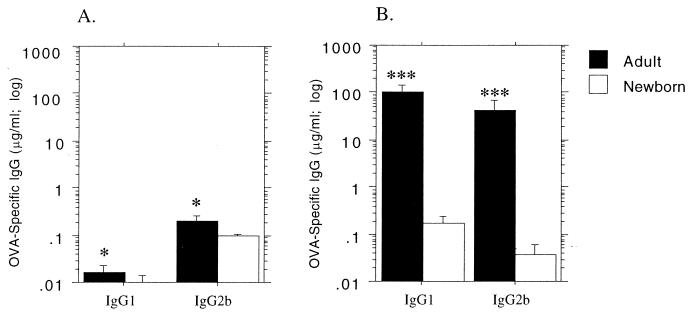

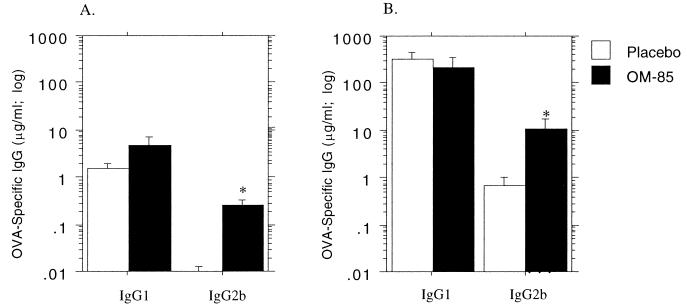

In the experiments shown in Fig. 1, newborn animals <1 day old, together with adults, were primed with soluble OVA i.p., and they were bled 2 weeks later (determined in preliminary experiments to be the peak of the primary response). All animals were rechallenged with soluble OVA i.p. 4 weeks postpriming, bled 2 weeks thereafter, and assayed for IgG1 and IgG2b anti-OVA antibody. It can be seen that this prime-challenge protocol elicits very low primary responses, particularly in the newborns. It is additionally evident that strong secondary responses (indicative of successful initial priming) occurred for both IgG subclasses in the adults; however, the newborns demonstrated weak secondary IgG1 responses, but displayed no evidence of priming for the IgG2b subclass.

FIG. 1.

Primary and secondary IgG subclass antibody responses to soluble OVA in rats as a function of age at priming. Newborn pups less than 24 h old and adult 12-week-old rats were immunized i.p. with soluble OVA in PBS at 25 μg/1-day-old rat (1do) and 100 μg/adult rat, respectively. Two weeks after immunization, serum was collected and primary OVA-specific IgG1 and IgG2b antibody titers were measured by ELISA (A). An i.p. challenge dose of 100 μg of soluble OVA was given to all rats 4 weeks after immunization, and serum was collected after a further 2 weeks for measurement of IgG1 and IgG2b recall responses (B). The data are representative of three separate experiments, and each bar represents the group mean (n = 6 rats) ± standard error. Mann-Whitney U test-generated P values indicate significant differences in antibody titers due to age of immunization (∗, 0.05 > P > 0.01; ∗∗, 0.01 > P > 0.005; and ∗∗∗, 0.005 > P > 0.0001).

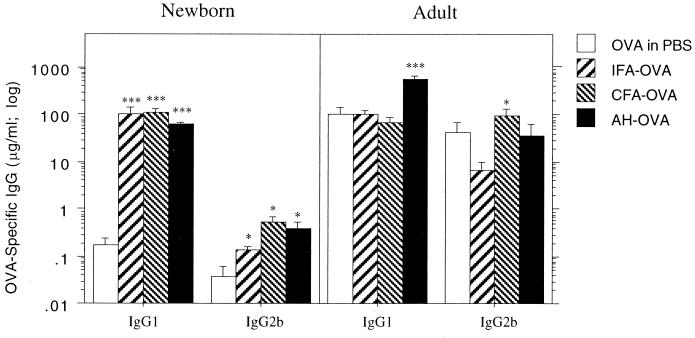

Figure 2 further contrasts the capacity of newborn and adult animals to express secondary immune responses, in this case when potent adjuvants are employed to unmask earlier priming. In the adults, the highest IgG1 and IgG2b recall responses occurred following respective challenge with OVA in AH versus OVA in CFA, a finding consistent with the known Th2 versus Th1 selectivity of these two adjuvants.

FIG. 2.

Influence of adjuvants on secondary IgG subclass responses in newborn versus adult rats. Groups of newborn rat pups and 12-week-old adult rats were immunized intraperitoneally with soluble OVA (25 and 100 μg of OVA, respectively) and challenged 28 days later with 100 μg of OVA in PBS or combined with CFA or AH. After another 14 days, serum was collected and OVA-specific IgG1 and IgG2b antibody titers were measured by ELISA. The results are representative of eight separate experiments, and each bar represents the group mean (n = 5 to 9 rats) ± standard error. Mann-Whitney U test-generated P values indicate a significant change in IgG subclass antibody response compared with those of rats challenged with soluble OVA. (∗, 0.05 > P > 0.01; ∗∗, 0.01 > P > 0.005; and ∗∗∗, 0.005 > P > 0.0001).

Effects of the oral bacterial extract OM-85 on IgG subclass responses.

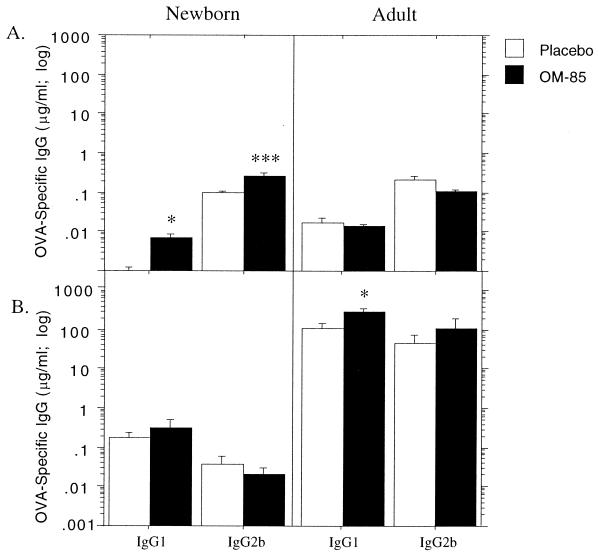

In Fig. 3, newborn or 12-week-old rats were primed i.p. with soluble OVA and given daily doses of OM-85 thereafter for 14 consecutive days, prior to serum collection for determination of peak primary response titers of IgG1 and IgG2b. OM-85 administration was continued as detailed in the legend to Fig. 3, prior to elicitation of a secondary response via rechallenge i.p. with soluble OVA. In the adult, i.p. priming was effective, as shown by the log-scale increase in titers following rechallenge, and OM-85 administration significantly enhanced priming for the IgG1 subclass.

FIG. 3.

Influence of OM-85 on primary and secondary IgG1 antibody responses of newborn rat pups immunized with soluble antigen. Administration of OM-85 or placebo (400 μg per g of body weight) to newborn rat pups and 12-week-old adult rats commenced on the same day as i.p. immunization with soluble OVA (25 and 100 μg, respectively). Dose administration was continued for 14 consecutive days, and serum was collected for the measurement of OVA-specific IgG1 and IgG2b primary antibody response titers (A). Administration of OM-85 or placebo was continued every second day until day 28, when treatment was withdrawn and each rat received a challenge dose of 100 μg of OVA in PBS i.p. After another 14 days, sera were collected and secondary antibody response titers were measured by ELISA (B). The data are representative of three separate experiments, and each bar represents the group mean (n = 5 to 9 rats). Mann-Whitney U test-generated P values indicate a significant difference in peripheral antibody response due to administration of OM-85 (∗, 0.05 > P > 0.01; ∗∗, 0.01 > P > 0.005; and ∗∗∗, 0.005 > P > 0.0001).

In contrast, titers of both the Th1-dependent and Th2-dependent IgG subclasses in primary responses of infant animals were boosted by OM-85 feeding. Consistent with the pattern demonstrated in Fig. 1, i.p. immunization of newborn animals resulted in weak priming for IgG1 subclass responses, but not for IgG2b, and this priming was not enhanced by OM-85.

Unmasking of the enhancing effects of oral bacterial extract OM-85 by the use of adjuvants.

In the experiments shown in Fig. 4, newborn rat pups were primed with soluble OVA i.p. and given doses of OM-85 up to day 28 as in Fig. 3. However, unlike the animals in Fig. 3, which were rechallenged on day 28 with soluble OVA, these animals were challenged with OVA together with the adjuvant IFA. It can be seen that the use of IFA unmasks substantial levels of priming for IgG1 antibody (c.f. titers in the placebo group in Fig. 4 versus those in the same group in Fig. 3B) and that the titers attained are equivalent to those for immunocompetent adults. OM-85 did not further boost these responses.

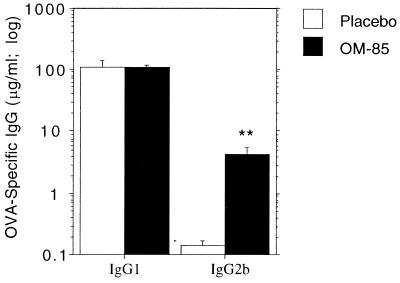

FIG. 4.

Unmasking of immunostimulatory activity of OM-85 by the use of adjuvant. Newborn rat pups were given 400 μg of OM-85 or placebo per g of body weight and received soluble OVA immunization i.p. Administration was continued daily until day 14 and thereafter every second day until day 28, when all rats received 100 μg of OVA in IFA. After another 14 days, serum was collected and IgG1 and IgG2b antibody titers were measured by ELISA. The results are representative of three separate experiments, and each bar represents the group mean (n = 6) ± standard error. Mann-Whitney U test-generated P values indicate significant differences in IgG titers due to neonatal exposure to OM-85 (∗, 0.05 > P > 0.01; and ∗∗, 0.01 > P > 0.005).

In contrast, and consistent with the data shown in Fig. 1B and 3B, IgG2b responses following secondary challenge were extremely low in the placebo group, indicating poor development of immunological memory in response to priming. However, corresponding responses in the OM-85-treated group were more than 1 log fold higher than those in placebo controls, suggesting that the vaccine had facilitated development of significant levels of immunological memory.

In Fig. 5, an alternative prime-challenge protocol was examined, in which OM-85 treatment of infant rats was carried out prior to initial OVA priming; OM-85 administration was continued thereafter up until secondary challenge, as detailed in the legend. This resulted in higher levels of OM-85 stimulation of IgG2b production, particularly in the secondary response.

FIG. 5.

Effect of OM-85 preexposure on priming for IgG subclass antibody response of newborn rat pups. Newborn rat pups were given oral doses of OM-85 or placebo (400 μg per g of body weight) on day 1. Dose administration was continued for 4 consecutive days, and on the 5th day, the pups were immunized s.c. with 25 μg of OVA in IFA. Administration of OM-85 or placebo was continued each day for a further 14 days (postimmunization), when serum was collected and primary OVA-specific IgG1 and IgG2b antibody titers were measured by ELISA (A). OM-85 or placebo was then given every second day until the day of challenge (3 weeks postimmunization). An i.p. challenge dose of 100 μg of OVA in PBS was given to all rats, and serum was collected after a further 2 weeks for measurement of IgG1 and IgG2b recall responses (B). The data are representative of four separate experiments, and each bar represents the group mean (n = 6 to 7 rats) ± standard error. Mann-Whitney U test-generated P values indicate significant differences in antibody titers due to administration of OM-85 (∗, 0.05 > P > 0.01; ∗∗, 0.01 > P > 0.005; and ∗∗∗, 0.005 > P > 0.0001).

Effect of OM-85 on in vitro T-cell responses.

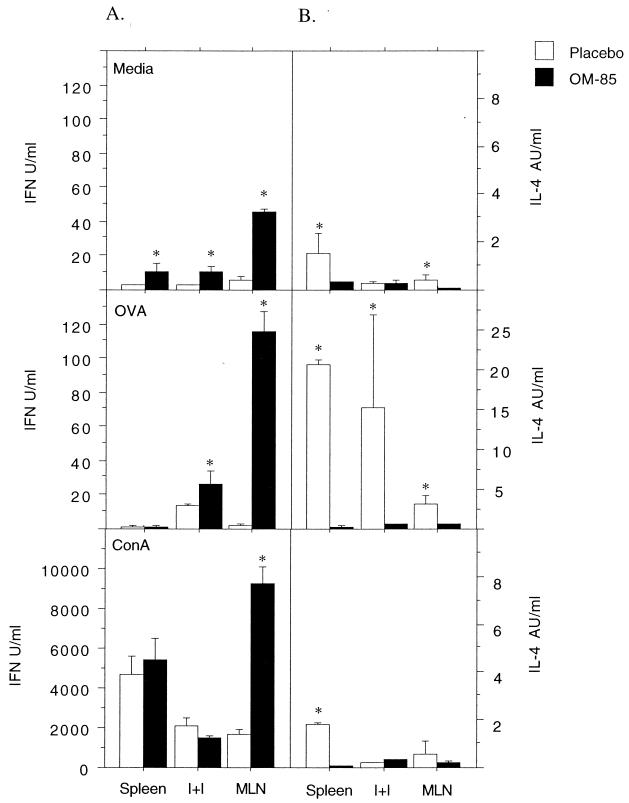

In Fig. 6, newborn rats were primed with OVA in IFA, with or without accompanying OM-85 administration, as detailed in the legend to Fig. 5. The methodology employed is standard in the field for T-helper-cell activation, and the cytokines produced in these cultures are primarily from T cells, but small and variable contributions from other cell types cannot be ruled out. The in vitro cytokine responses were assessed 21 days later, a time point identified in earlier experiments as the peak or plateau of T-helper-cell reactivity. Several key observations are illustrated. First, feeding of the OM-85 extract increases levels of spontaneous IFN-γ production (note medium controls), in particular in the MLN draining the gut, and a reciprocal pattern of decreased IL-4 production is also evident. Maximal IFN-γ response capacity, as determined by polyclonal ConA stimulation, was also increased in MLN, again accompanied by decreased IL-4 release. A similar pattern of markedly increased antigen-specific IFN-γ production and a parallel decrease in the IL-4 response were observed in lymph nodes and, to a lesser extent, spleens.

FIG. 6.

Orally administered OM-85 increases IFN-γ production and decreases IL-4 production by neonatally immunized rats. Newborn rat pups were given OM-85 or placebo and immunized with OVA in IFA as described in the legend to Fig. 5, except that no secondary antigen challenge was given. Single-cell preparations of spleen, pooled I+I, and MLN cells were prepared 21 days after immunization. The cells were plated in triplicate and stimulated with medium, OVA, or ConA, and culture supernatants were collected after 24 and 48 h. IFN-γ production was measured at 48 h by ELISA (A), and IL-4 was measured at 24 h by a bioassay (B). The data are representative of three separate cell culture experiments, and each bar represents the mean (background subtracted) ± standard error of triplicate wells of pooled spleen, I+I, and MLN cells from 6 to 10 rats. Mann-Whitney U test-generated P values indicate significant differences in cytokine levels due to administration of OM-85 (∗, 0.05 > P > 0.01; ∗∗, 0.01 > P > 0.005; and ∗∗∗, 0.005 > P > 0.0001).

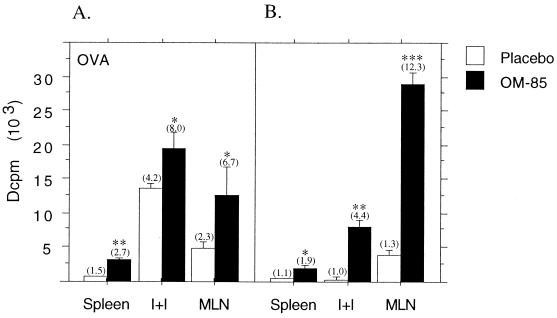

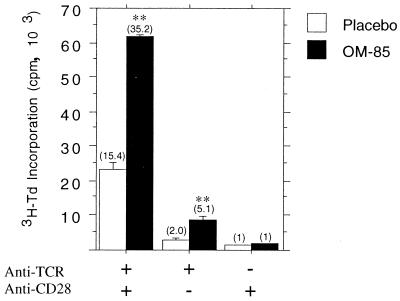

The experiments shown in Fig. 7 examined the effects of OM-85 on lymphoproliferative responses during primary and secondary responses to OVA, focusing on time points during active in vivo expansion of specific T cells. It can be seen that OVA-specific lymphoproliferative responses are significantly enhanced in OM-85-treated animals during both the primary and secondary responses in all lymphoid organs tested, in particular MLN. In Fig. 8, the effects of OM-85 on splenic lymphoproliferative responses were examined by employing an alternative polyclonal stimulant, anti-TCRαβ ± anti-CD28. In these experiments, donor animals did not receive any immunization prior to splenocyte preparation. It is evident that with these polyclonal stimuli, lymphocytes from OM-85-treated animals exhibit marked enhancement of activation and/or proliferation.

FIG. 7.

OM-85 administration increases in vitro lymphoproliferative responses in neonatally immunized rats. Newborn rat pups were given OM-85 or placebo and immunized with OVA in IFA as described in the legend to Fig. 5. Single-cell preparations of spleen, I+I, and MLN cells were made 10 days after immunization (A) and 7 days after soluble OVA challenge (B). The cells were plated in triplicate and stimulated with OVA for 72 h, with [3H]thymidine added for the final 16 h. The data are representative of four separate experiments, and each bar represents the mean Δcpm (103 [medium background subtracted]) ± standard error of triplicate wells of individual spleen and pooled I+I and MLN cells from six rats. Mann-Whitney U test-generated P values indicate significant differences in proliferation due to administration of OM-85 (∗, 0.05 > P > 0.01; ∗∗, 0.01 > P > 0.005; and ∗∗∗, 0.005 > P > 0.0001). Values in parentheses above bars represent stimulation ratios (fold increase above background controls).

FIG. 8.

Oral OM-85 increases the in vitro proliferative response of unimmunized neonatal T cells to a polyclonal stimulus. Newborn rat pups were given OM-85 (n = 12) or placebo (n = 12) (400 μg per g of body weight) for 14 consecutive days. Splenocytes were then prepared and plated into anti-TCR antibody-coated tissue culture wells and stimulated with anti-CD28 antibody or medium alone. Control wells were coated with a non-rat-specific antibody (OX21), and splenocytes were also stimulated with anti-CD28 antibody. The cells were harvested after 72 h with the addition of [3H]thymidine (3H-Td) for the last 16 h. The data are representative of three separate experiments, and each bar represents mean [3H]thymidine incorporation as 103 cpm ± standard error of triplicate wells. Mann-Whitney U test-generated P values indicate significant differences in proliferation due to administration of OM-85 (∗, 0.05 > P > 0.01; ∗∗, 0.01 > P > 0.005; and ∗∗∗, 0.005 > P > 0.0001). Values in parentheses above bars represent stimulation ratios.

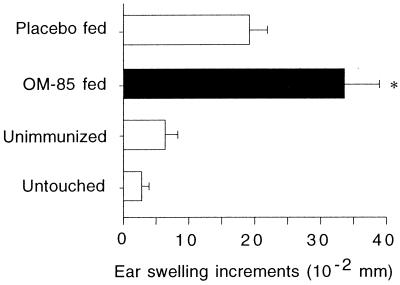

Effects of OM-85 on priming in vivo DTH responses.

In the experiments shown in Fig. 9, animals were OVA primed by a protocol known to elicit DTH responses and given a dose of OM-85 or placebo, prior to secondary immunization and subsequent intradermal challenge (in the ear) with soluble OVA. DTH responses were assessed as changes in ear thickness 24 h after challenge. It can be seen that DTH responses are significantly elevated in the OM-85-fed group.

FIG. 9.

Neonatal administration of OM-85 enhances priming for subsequent DTH responses. Newborn rat pups were given OM-85 (n = 6) or placebo (n = 7; 400 μg/ml per g of body weight) and immunized s.c. with 25 μg of OVA in IFA. OM-85 or placebo was given each day for 14 days after immunization and then every second day until day 28. On this day, feeding treatments were withdrawn, and each animal received 100 μg of OVA in PBS i.p. After another 4 weeks, rats (now 8 weeks old) were injected i.d. in the right ear with OVA in PBS and in the left ear with PBS alone. Unimmunized age-matched control rats (n = 6) were injected i.d. with OVA in PBS and with PBS alone in order to establish background swelling responses. Twenty-four hours later, skin swelling of both ears was measured with a micrometer. The left ear thickness (PBS) was subtracted from the right ear thickness (OVA) to give increments of ear swelling. Ears of untouched animals (n = 4) were measured in order to establish background variation. The data are representative of five separate experiments, and each bar represents the mean difference in ear swelling ± standard error. Mann-Whitney U test-generated P values indicate significant differences in ear swelling due to administration of OM-85 (∗, 0.05 > P > 0.01).

DISCUSSION

It is generally acknowledged that while the transition from fetal to adult life involves “maturation” of several aspects of innate and adaptive immune function, the nature and degree of the maturational deficit in newborns may vary significantly between species (2, 18, 26). However, the two species studied in the most detail, humans and mice, share as a common feature the generalized Th2 bias, which is characteristic of the fetal compartment.

In murine systems, this bias is manifested as differential expression of Th2-polarized immunological memory in response to priming during the preweaning period, together with diminished capacity to develop Th1-polarized immunity (3–5, 10), which appears attributable principally to deficiencies in the antigen-presenting cell (APC) compartment (34). In humans, it has been demonstrated that early postnatal responses to environmental allergens (31, 32) and microbial antigens (35) also display an intrinsic Th2 bias, and recent findings from our laboratory suggest that this bias is associated with reduced capacity of infants to generate long-lasting Th1-polarized memory in response to vaccines (35a). Underlying this Th2 bias in human infants is reduced capacity to generate T-cell IFN-γ responses in vitro (24, 35a, 43), which appears to be derived from functional deficiencies in both the T-cell and APC compartments (2, 17, 24, 26, 43).

As noted in the introduction, the functional consequences of “inefficient” postnatal maturation of Th1 function in humans are increasingly being considered as potential etiologic factors in a variety of immunoinflammatory diseases, as well as risk factors for infections in infancy and childhood. Accordingly, potential avenues for selective boosting of Th1 activity during early life warrant further investigation.

Our studies reported here were carried out with an infant rat model, which shares the principal characteristics of the established murine models and of infant humans, notably reduced capacity to generate Th1 (as opposed to Th2)-polarized memory responses (Fig. 1 and 2). We have employed this model to investigate the possibility that microbial extract provided orally may be able to enhance the capacity of infant animals to develop a balanced Th1-Th2 memory response against parenterally administered antigen.

Our initial interest in this approach derives from the extensive literature on germfree animals, which has established that the principal signals for maturation of immune function in mammals are provided by the gastrointestinal microflora that are established in early postnatal life. It is evident from studies with germfree rats (13), and in particular from recent experiments with germfree mice (38), that denial of gastrointestinally derived microbial stimulation effectively prevents the infant immune system from developing a balance between the Th1 and Th2 arms of the adaptive immune response, effectively “locking” it into the Th2 bias characteristic of the fetal compartment. Additionally, microbial conventionalization of the gastrointestinal tract redresses this imbalance (38).

Additional impetus for these studies was provided by reports on the immunostimulatory effects of the OM-85 oral bacterial extract in animal models (7, 8) and in human clinical trials (12, 30). This agent, which is an extract of cell walls from eight bacterial species commonly responsible for respiratory infections, has been demonstrated to exert a variety of stimulatory effects upon humoral and cellular immunity and upon the expression of protective immunity at mucosal surfaces.

The salient findings from this study on the effects of OM-85 in infant rats are as follows. First, treatment of animals with the extract during primary immune responses had variable effects, which were related to the intensity of antigen rechallenge and the timing of administration of OM-85 relative to initial antigen priming. Thus, administration of OM-85 clearly boosted priming for Th1-dependent IgG2b responses, providing an adjuvant (IFA in the experiments shown) was employed during secondary challenge (Fig. 4). The magnitude of the OM-85-boosted IgG2b response in Fig. 5B is approximately threefold that in Fig. 4. This indicates that the effects of the extract are maximal if it is given for several days before priming (Fig. 5), suggesting that time-dependent “maturation” of one or more elements of the immune response was required before the optimal immunostimulatory effects occur.

The results of experiments in Fig. 6 to 8 suggest that one cell population implicated in the effects of the OM-85 extract are Th cells. These findings establish that concomitant with upregulation of the IgG2b component of the memory response, the overall capacity of the Th cell compartment to expand upon polyclonal activation and the capacity for expansion of OVA-specific Th cells are increased. More importantly, accompanying these changes are alterations in the Th1-Th2 balance, as demonstrated by upregulation of the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ and concomitant downregulation of IL-4 production. These effects are most notable in the MLN, which directly drains the site of administration of the OM-85 extract, but are also observed at distal sites in the immune system. Further confirmation of the efficacy of the oral vaccine in preferential upregulation of Th1 immunity is the demonstration in Fig. 9 that treated animals develop enhanced memory DTH responses.

Whether this stimulation is the direct result of effects of the oral extract on Th cells remains to be established. However, the finding that the boosting effects of OM-85 were only observed when adjuvant was employed in the secondary response (cf. Fig. 3 and 4) suggests a possible common cellular target or targets for both agents. A likely candidate for these effects are APC, which have been demonstrated in the mouse to display a maturational deficiency in Th1-stimulatory capacity during the neonatal period and to accordingly prime preferentially for Th2 immunity (34). APC are also acknowledged to play a central role in mediating the effects of immunological adjuvants, and studies with other systems have demonstrated modulatory effects of OM-85 on functions of several cell types that display APC activity (6–8, 23, 25). In particular, it has been shown that the extract stimulates IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells via induction of IL-12 secretion in APC (9). Given the important role of APC-derived IL-12 in stimulating the preferential development of Th1 immunity (15), this pathway appears to be a likely target for the effects of OM-85 in this model. Accordingly, more detailed studies on the antigen processing and presentation functions and costimulatory activity of APC following OM-85 treatment, appear warranted.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that repeated oral administration of the bacterial extract Broncho-Vaxom OM-85 to rats during the preweaning period selectively amplifies Th1 function and in doing so appears to accelerate the normal postnatal maturation of adaptive immune competence. It appears plausible that the vaccine may function via mechanisms analogous to those employed via the normal gastrointestinal microflora, which have been shown in other systems to drive this natural process postnatally. The Th1-stimulatory effects observed here are likely to contribute to the clinical efficacy of this bacterial extract in enhancing resistance to infections, as demonstrated in human trials (11, 12, 30).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aberle J H, Aberle S W, Dworzak M N, Mandl C W, Rebhandl W, Vollnhofer G, Kundi M, Popow-Kraupp T. Reduced interferon-γ expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of infants with severe respiratory syncytial virus disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1263–1268. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9812025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adkins B. T-cell function in newborn mice and humans. Immunol Today. 1999;20:330–335. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adkins B, Du R-Q. Newborn mice develop balanced Th1/Th2 primary effector responses in vivo but are biased to Th2 secondary responses. J Immunol. 1998;160:4217–4224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrios C, Brandt C, Berney M, Lambert P-H, Siegrist C-A. Partial correction of the Th2/Th1 imbalance in neonatal murine responses to vaccine antigens through selective adjuvant effects. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2666–2670. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrios C, Brawand P, Berney M, Brandt C, Lambert P-H, Siegrist C-A. Neonatal and early life immune responses to various forms of vaccine antigens qualitatively differ from adult responses: predominance of a Th2-biased pattern which persists after adult boosting. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1489–1496. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bessler W G, Huber M. Bacterial cell wall components as immunomodulators. II. The bacterial cell wall extract OM-85 BV as unspecific activator, immunogen and adjuvant in mice. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1997;19:551–558. doi: 10.1016/s0192-0561(97)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broug-Holub E, Kraal G. In vivo study on the immunomodulating effects of OM-85 BV on survival, inflammatory cell recruitment and bacterial clearance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1997;19:559–564. doi: 10.1016/s0192-0561(97)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broug-Holub E, Schornagel K, Persoons J H, Kraal G. Changes in cytokine and nitric oxide secretion by rat alveolar macrophages after oral administration of bacterial extracts. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;101:302–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb08355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byl B, Libin M, Gerard M, Clumeck N, Goldman M, Mascart-Lemone F. Bacterial extract OM85-BV induces interleukin-12-dependent IFN-gamma. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1998;18:817–821. doi: 10.1089/jir.1998.18.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen N, Gao Q, Field E H. Expansion of memory Th2 cells over Th1 cells in neonatal primed mice. Transplantation. 1995;60:1187–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collet J-P, Ducruet T, Kramer M S, Haggerty J, Floret D, Chomel J-J, Durr F T. E. R. Group. Stimulation of nonspecific immunity to reduce the risk of recurrent infections in children attending day-care centers. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12:648–652. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199308000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collet J-P, Shapiro S, Ernst P, Renzi P, Ducruet T, Robinson A P.-I. S. S. C. A. R. Group. Effects of an immunostimulating agent on acute exacerbations and hospitalizations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1719–1724. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.6.9612096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durkin H G, Bazin H, Waksman B H. Origin and fate of IgE-bearing lymphocytes. I. Peyer's patches as differentiation site of cells simultaneously bearing IgA and IgE. J Exp Med. 1981;154:640–648. doi: 10.1084/jem.154.3.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gracie J A, Bradley J A. Interleukin-12 induces interferon-gamma-dependent switching of IgG alloantibody subclass. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1217–1221. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heufler C, Koch F, Stanzl U, Topar G, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Enk A, Steinman R M, Romani N, Schuler G. Interleukin-12 is produced by dendritic cells and mediates T helper 1 development as well as interferon-g production by T helper 1 cells. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:659–668. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holt P G. Environmental factors and primary T-cell sensitisation to inhalant allergens in infancy: reappraisal of the role of infections and air pollution. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1995;6:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1995.tb00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holt P G, Clough J B, Holt B J, Baron-Hay M J, Rose A H, Robinson B W S, Thomas W R. Genetic 'risk' for atopy is associated with delayed postnatal maturation of T-cell competence. Clin Exp Allergy. 1992;22:1093–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1992.tb00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holt P G, Jones C A. The development of the immune system during pregnancy and early life. Allergy. 2000;55:688–697. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holt P G, Macaubas C. Development of long term tolerance versus sensitisation to environmental allergens during the perinatal period. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:782–787. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsiung L M, Barclay A N, Brandon M R, Sim E, Porter R R. Purification of human C3b inactivator by monoclonal-antibody affinity chromatography. Biochem J. 1982;203:293. doi: 10.1042/bj2030293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hünig T, Wallny H J, Hartley J K, Lawetzky A, Tiefenthaler G. A monoclonal antibody to a constant determinant of the rat T cell antigen receptor that induces T cell activation. Differential reactivity with subsets of immature and mature T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1989;169:73–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunt S V, Fowler M H. A repopulation assay for B and T lymphocyte stem cells employing radiation chimeras. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1981;14:446–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1981.tb00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacquier-Sarlin R M, Polla B S, Dreher D. Selective induction of the glucose-regulated protein grp78 in human monocytes by bacterial extracts (OM-85): a role for calcium as second messenger. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;226:166–171. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis D B, Larsen A, Wilson C B. Reduced interferon-gamma mRNA levels in human neonates. Evidence for an intrinsic T cell deficiency independent of other genes involved in T cell activation. J Exp Med. 1986;163:1018–1023. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.4.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchant A, Goldman M. OM-85 BV upregulates the expression of adhesion molecules on phagocytes through CD 14-independent pathway. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1996;18:259–262. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(96)84505-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall-Clarke S, Reen D, Tasker L, Hassan J. Neonatal immunity: how well has it grown up? Immunol Today. 2000;21:35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01548-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez F D, Stern D A, Wright A L, Holberg C J, Taussig L M, Halonen M. Association of interleukin-2 and interferon-γ production by blood mononuclear cells in infancy with parental allergy skin tests and with subsequent development of atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96:652–660. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKnight A J, Classon B J. Biochemical and immunological properties of rat recombinant interleukin 2 and interleukin 4. J Immunol. 1992;120:2027–2032. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMaster W R, Williams A F. Identification of Ia glycoproteins in rat thymus and purification from rat spleen. Eur J Immunol. 1979;9:426–433. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830090603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orcel B, Baud M, Delclaux B, Derenne J P. Oral immunization with bacterial extracts for protection against acute bronchitis in elderly institutionalized patients with chronic bronchitis. Eur Respir J. 1994;7:446–452. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07030446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prescott S L, Macaubas C, Holt B J, Smallacombe T, Loh R, Sly P D, Holt P G. Transplacental priming of the human immune system to environmental allergens: universal skewing of initial T-cell responses towards the Th-2 cytokine profile. J Immunol. 1998;160:4730–4737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prescott S L, Macaubas C, Smallacombe T, Holt B J, Sly P D, Holt P G. Development of allergen-specific T-cell memory in atopic and normal children. Lancet. 1999;353:196–200. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Renzi P M, Turgeon J P, Marcotte J E, Drblik S P, Bérubé D, Gagnon M F, Spier S. Reduced interferon-γ production in infants with bronchiolitis and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1417–1422. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9805080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ridge J P, Fuchs E J, Matzinger P. Neonatal tolerance revisited: turning on newborn T cells with dendritic cells. Science. 1996;271:1723–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowe J, Macaubas C, Monger T, Holt B J, Harvey J, Poolman J T, Sly P D, Holt P G. Antigen-specific responses to diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis vaccine in human infants are initially Th2 polarized. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3873–3877. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.3873-3877.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35a.Rowe, J., C. Macaubas, T. Monger, B. J. Holt, J. Harvey, J. T. Poolman, R. Loh, P. D. Sly, and P. G. Holt. Heterogeneity in DTaP vaccine-specific cellular immunity during infancy: relationship to variations in the kinetics of postnatal maturation of systemic Th1 function. J. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Saoudi A, Kuhn J, Huygen K, de Kozak Y, Velu T, Goldman M, Druet P, Bellon B. TH2 activated cells prevent experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis, a TH1-dependent autoimmune disease. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:3096–3103. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stumbles P, Mason D. Activation of CD4+ T cells in the presence of a nondepleting monoclonal antibody to CD4 induces a Th2-type response in vitro. J Exp Med. 1995;182:5–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sudo N, Sawamura S-A, Tanaka K, Aiba Y, Kubo C, Koga Y. The requirement of intestinal bacterial flora for the development of an IgE production system fully susceptible to oral tolerance induction. J Immunol. 1997;159:1739–1745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tacke M, Clark G J, Dallman M J, Hünig T. Cellular distribution and costimulatory function of rat CD28. Regulated expression during thymocyte maturation and induction of cyclosporin A sensitivity of costimulated T cell responses by phorbol ester. J Immunol. 1995;154:5121–5127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van der Meide P H, Borman A H, Beljaars H G, Dubbeld M A, Botman C A, Shellekens H. Isolation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies directed to rat interferon-gamma. Lymphokine Res. 1989;8:429–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wegmann T G, Lin H, Guilbert L, Mosmann T R. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a Th2 phenomenon? Immunol Today. 1993;14:353–356. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90235-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson C B. Immunologic basis for increased susceptibility of the neonate to infection. J Pediatr. 1986;108:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80761-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson C B, Westall J, Johnston L, Lewis D B, Dover S K, Apert A R. Decreased production of interferon gamma by human neonatal cells. Intrinsic and regulatory deficiencies. J Clin Investig. 1986;77:860–867. doi: 10.1172/JCI112383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]