Abstract

We constructed county-level models to examine properties of the SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant wave of infections in North Carolina and assessed immunity levels (via prior infection, via vaccination, and overall) prior to the Delta wave. To understand how prior immunity shaped Delta wave outcomes, we assessed relationships among these characteristics. Peak weekly infection rate and total percent of the population infected during the Delta wave were negatively correlated with the proportion of people with vaccine-derived immunity prior to the Delta Wave, signaling that places with higher vaccine uptake had better outcomes. We observed a positive correlation between immunity via infection prior to Delta and percent of the population infected during the Delta wave, meaning that counties with poor pre-Delta outcomes also had poor Delta wave outcomes. Our findings illustrate geographic variation in outcomes during the Delta wave in North Carolina, highlighting regional differences in population characteristics and infection dynamics.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Delta wave, B.1.617.2, Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity

1. Background

The first case of COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection, was detected in Washington state on January 20, 2020 (CDC, 2022a), and SARS-CoV-2 rapidly spread across the United States (US). To mitigate transmission, states and localities enacted a variety of nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) such as mask mandates, limits on gathering sizes, school and nonessential business closures, and stay-at-home orders with varying levels of success. Many of the more stringent NPIs were rescinded prior to or shortly after vaccination began in December 2020 (CDC, 2022a; NC COVID-19, 2022; NC.gov, 2022). Although multiple effective vaccines were freely available, vaccination rates remained low in many regions across the US and, during summer 2021, there was a “third” wave of SARS-CoV-2 infections due to the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant of the virus (Callaway, 2021), which is approximately 60% more transmissible than prior strains (Shiehzadegan et al., 2021). Other highly transmissible strains have emerged since that time, including the B.1.1.529 (Omicron) variant, which caused another large wave of infections (Zimmer and Jacobs, 2022). On April 1, 2022, the US topped 80 million reported cases of COVID-19, and on May 24, 2022, the 1 millionth death due to COVID-19 was reported (CDC, 2022b).

The repeated waves of SARS-CoV-2 infections have been fueled by many people who remained susceptible to infection. Individual immunity from an infection can be achieved via prior infection or vaccination; those without immunity remain susceptible. Susceptible members of a population can still be protected from infection via herd or community immunity wherein a large proportion of the population has immunity and acts as a shield that protects susceptible people from being infected by reducing the probability that they come into contact with an infectious person. The herd immunity threshold (HIT) is the proportion of the population with immunity to an infection to tip transmission into a decline and thereby protect some susceptible members of the population (Fine, 1993). A simple definition of the HIT for an infection is 1-1/R0 with R0 being the infection's basic reproductive number, defined as the number of secondary cases expected to result from a single, typical infected person over the course of that person's infectious period in an entirely susceptible population (Delamater et al., 2019; Fine, 1993). R0 is a measure of the contagiousness or transmissibility of an infectious agent, but is also context-dependent such that variations in contact rates and patterns among different populations may lead to different R0 values for the same infection (Delamater et al., 2019).

An important aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the geographic variation in SARS-CoV-2 infections, COVID-19 outcomes, and vaccination uptake. Several studies found that the COVID-19 outbreak in Europe was associated with geographical characteristics, specifically with cityscapes, land-use, and transportation (Hass and Jokar Arsanjani, 2021; Rose-Redwood et al., 2020; Sharifi and Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020). Kim and Castro (2020) found strong spatial autocorrelation with the use of space-time scan clusters of COVID-19 cases and showed that disease initially started in the densely and more heavily populated regions and then moved to more remote areas over time. Huang et al. (2021) found that in South Carolina, spatial and temporal patterns differed in which infection was initially concentrated in small towns within metro counties and then diffused to centralized urban and major cities. Moreover, case rates and mortality rates were positively correlated with pre-existing social vulnerability. Despite the large amount of research on the pandemic (in general), there is a large amount that is still unknown, especially regarding the nature of the various waves of infections and how the properties of the infection have interacted with a highly uneven geographic landscape of human behavior (e.g., mobility and social distancing, adherence to COVID-related nonpharmaceutical interventions such as masking, or vaccine uptake).

In this analysis, we examine the spatiotemporal characteristics of the wave of infections caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant at the county level in North Carolina. Specifically, we estimate and assess immunity levels (via prior infection, via vaccination, and overall) prior to the Delta wave and characteristics of the Delta wave itself. We then assess the relationships among these characteristics to assess the role of prior immunity in shaping outcomes of the Delta wave at the county level. The results of this research highlight the geographically varying nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and how immunity levels in the population can affect infection transmission dynamics.

2. Data and methods

2.1. Data

Data were extracted from the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) public database “NCDHHS Data Behind the Dashboards” (NCDHHS, 2022). The data include weekly positive tests (reported cases) and number of people who received a COVID-19 vaccination (broken down by first or second dose) for each North Carolina county (N=100). County level population data were gathered from the 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates from the US Census Bureau (US Census Bureau, 2022).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Estimate percent immune

People acquire immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection via a prior infection or vaccination. However, some people may have been infected prior to vaccination and others may be vaccinated prior to infection (a breakthrough infection). As such, the percentage of the population with immunity can be considered a function of the total number of people infected (with immunity), the total number vaccinated (with immunity), and the number of people who have been both infected and vaccinated (with immunity):

2.2.2. Estimate People Immune Via Prior Infection

Reported cases of COVID-19 only represent a subset of the total number of people who were infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus due to limitations in testing availability (especially during the early stage of the pandemic) and the presence of people with asymptomatic infections. To account for this, we estimated the number of people who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 using two distinct approaches:

-

(1)

We multiplied the reported number of positive cases by a factor of 4 based on estimates of the proportion of all infections detected via testing in the United States from February 2020 to September 2021 (CDC, 2021a; Reese et al., 2021).

-

(2)

We divided the number of reported deaths from COVID-19 by the infection fatality ratio (0.0065 deaths per infection), then lagged the infections by the median number of days from death to reporting (7 days for ages 18-64 and 6 days for ages 65 and above) (CDC, 2021a).

We calculated the mean of the two infection estimates. We assumed that all people with prior infection were immune (CDC, 2021b).

2.2.3. Estimate people immune via vaccination

The two mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Moderna and Pfizer) confer immunity from SARS-CoV-2 infection (Alpha and Delta) for 82% of recipients after 14 days from receipt of the first dose and 92% of recipients one week after receipt of the second dose (Baden et al., 2021; Pilishvili et al., 2021; Polack et al., 2020). The one-dose Johnson & Johnson (Janssen) vaccine confers immunity for 70% of recipients after 14 days from receipt (Oliver et al., 2021). We estimated immunity via vaccination for each county using two approaches, given data limitations of the mRNA vaccines (the data include the number of people receiving their first and second dose during each week, but do not include when those receiving their second dose received their first dose).

-

1.

We multiplied the number of people who received their first dose of an mRNA vaccine by 82% and lagged by 14 days (into the future) to estimate immunity after the first dose. We assumed that everyone in this group would receive their second dose on time (21 days for the Pfizer vaccine and 28 days for the Moderna vaccine) and some would gain immunity after this dose; because the data are not disaggregated by mRNA vaccine, we assumed 21 days. Thus, in the model, 35 days (21 days between doses plus 14 days to develop immunity) from receipt of the first mRNA vaccine dose, we assumed that an additional 10% of first dose recipients would gain immunity (bringing the total percent immune to 92% after receiving both doses). For those receiving the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, we multiplied the number receiving the vaccine by 70% and lagged by 14 days (into the future). We then summed the total number immune via vaccination for each week (those gaining immunity 14 days after the first dose of an mRNA vaccine, those gaining immunity 14 days after the second dose of an mRNA vaccine, and those gaining immunity 14 days after the single dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

-

2.

In the second approach, we used the same methods to estimate immunity based on the number of people receiving the first dose of the mRNA vaccines and the number of people receiving the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. However, rather than assuming all first dose recipients of the mRNA vaccines received their second dose on time, we used the observed number of people who received a second dose. We used two different approaches to estimating immunity via vaccination and we averaged over the immunity levels that we would get using the CDC Case Multiplier and Observational Vaccine Estimates, CDC Case Multiplier and Theoretical Vaccine Estimates, Infection by Death backsolve method and Observational Vaccine Estimate, and Infection by Death backsolve method and Theoretical Vaccine Estimates. We averaged over the values of these models to obtain immunity estimates since an average would result in a more reliable trend.

We calculated the mean of the two estimates of immunity via vaccination.

2.2.4. Estimate immunity via infection and vaccination

Given that the immunity estimates via infection and vaccination were derived independently, we accounted for people who were both infected with SARS-CoV-2 and received the COVID-19 vaccine. We assumed prior infection and vaccination were independent events and therefore used the multiplication rule for independent events (the percent of people with immunity from both infection and vaccination are the product of the two values). While this assumption is likely not perfectly true, we were unable to find compelling evidence to inform an alternate assumption. We used the mean values of immunity via prior infection and immunity via vaccination to estimate the overall percent of people immune in each county. Moreover, our model did not account for waning immunity after vaccination and immunity.

2.2.5. Estimate delta wave characteristics

We estimated the start date of the Delta wave for each county by fitting a loess curve over the weekly new infections and finding the last (or second to last) minimum point of the fitted loess curve using the “find peaks” function from the R package ggpmisc (Aphalo et al., 2022). Using the start date of the Delta wave, we filtered the data strictly to observations after the Delta wave began and found the peak date by finding the maximum of the observed weekly new infections. For each county, we summed the estimated infections over the course of the Delta wave and divided by the total population to calculate the percent of the population infected during the Delta wave.

We constructed an SIR (Susceptible, Infected, Recovered) deterministic compartmental model for each county in North Carolina during the SARS-CoV-2 Delta wave using the R package pomp (King et al., 2022). The SIR model assumes homogeneous mixing of people within a population and a constant population (no births or deaths). The transitions among compartments over time are determined by the following set of equations:

In the equations, S(t) is the number of people susceptible at time t, I(t) is the number of people infected, and R(t) is number of people recovered at time t. The number of people in the three components always sums to N(t), the total population at time t (this quantity is constant). The infection transmission rate (β) determines the rate in which people move from susceptible to infected and is primarily a function of human behavior, as it varies with the contact rate among members of a population (Martcheva, 2015). The infection recovery rate (γ) determines the rate in which infected people move to the recovered compartment. While γ is largely a function of the pathogen, it also may vary from place to place in real world settings due to the age structure (or other characteristics) of the population (Martcheva, 2015).

For each county, we estimated β and γ by minimizing the Sum-of-Squared Errors (SSE) between new weekly infections derived from the SIR model (I(tj)) and estimated infections from the observed data (Yj):

For each county, we used β and γ to calculate the R0 of the Delta wave using the following formula (Martcheva, 2015). In this equation, β is a function of human behavior and γ is a function of the pathogenicity of the virus:

2.2.6. Comparisons

We evaluated whether immunity levels prior to the Delta wave were associated with characteristics and outcomes of the Delta wave. To do so, we used Pearson's correlation to compare county-level immunity percent (via infection, via vaccination, and overall) at the start of the Delta wave and the Delta wave start and peak date (dates were converted to numeric day of year to facilitate analysis), peak weekly infection rate, and percent of the population infected.

2.2.7. Sensitivity analysis

Given uncertainty in the parameters and assumptions in our immunity estimation models, we conducted a sensitivity analysis that included two alternate inputs for the percent immune via infection (prior to the Delta wave) as well as two additional scenarios regarding the overlap in people who had been both infected and vaccinated. In the main analysis of people immune via prior infection, we used an average of estimates derived from death data and from case data; in the sensitivity analysis, we used each individual estimate of immunity as an input. Our main analysis assumed that prior infection and vaccination were independent events. In the sensitivity analysis, we used this assumption to probe the lower and upper limits of our estimates by setting the lower bound of immunity to the maximum overlap among those who had been both vaccinated and infected and setting the upper bound to the minimum overlap. For example, if a county had 20% immune due to prior infection and 30% immune from vaccination, in the main analysis this would result in an overall immunity estimate of 20% + 30% - (20% * 30%) = 44%. For the lower bound analysis, this would result in an estimate of 30% (assumes 100% overlap between people infected and vaccinated); the immunity estimate would be 50% in the upper bound analysis (assumes 0% overlap between people infected and vaccinated).

3. Results

Estimates of new weekly infections per 10,000 people over the course of the Delta wave in North Carolina are plotted by county and for the entire state in Fig. 1 . The earliest detected start date of the Delta wave was the week of May 9th, 2021 (in Person County). At that time, an estimated 32.0% and 38.4% of all state residents had immunity via infection and vaccination, respectively; after accounting for people who had been both infected and vaccinated, we estimate overall immunity statewide at 58.4% during this week.

Fig. 1.

New weekly infection estimates (per 10,000 people) by county (transparent lines) and for North Carolina (dashed line) during the Delta wave.

3.1. Immunity

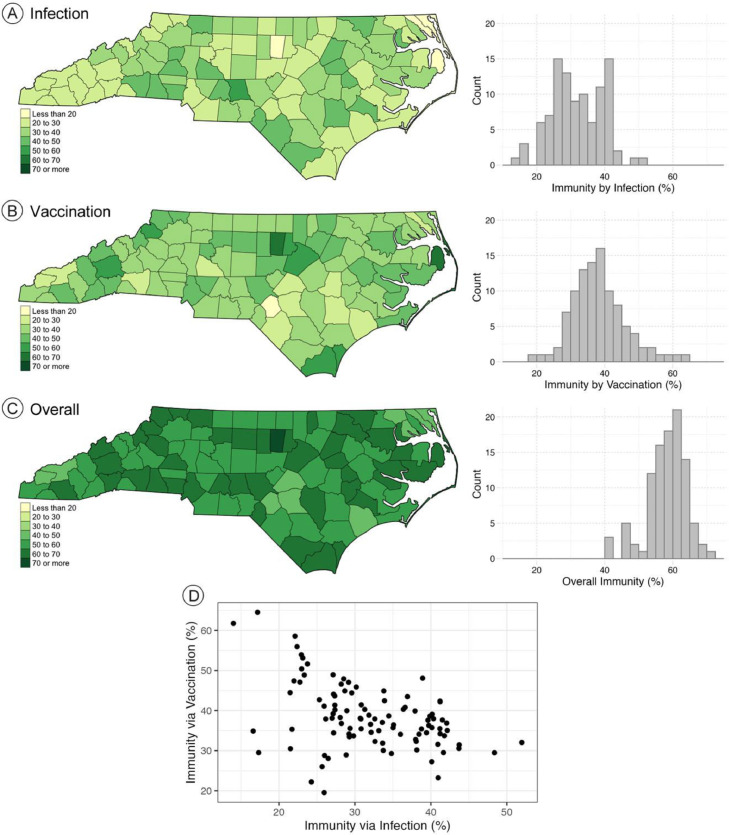

The county level immunity estimates via infection (A), vaccination (B), and overall (C) at the county-specific onset of the Delta wave are presented as maps and histograms in Fig. 2 . Orange County had the highest level of overall immunity (70.6%) when the Delta wave began, while Hoke County had the lowest (40.4%). Orange County (64.5%) and Hoke County (19.5%) also had the highest and lowest levels of immunity by vaccination. Montgomery County (52%) and Dare County (14%) had the highest and lowest estimated levels of immunity by prior infection when the Delta wave began. The county averages for immunity via infection, vaccination, and overall at the county-specific onset of the Delta wave were 32%, 38.4%, and 58.4%, respectively. In general, counties with higher immunity via prior infection had lower immunity via vaccination, as shown in Fig. 2(D).

Fig. 2.

Estimated immunity percentage in North Carolina at the county-specific onset of the Delta wave (A) via prior infection, (B) via vaccination, and (C) for overall immunity. (D) Scatterplot of immunity via prior infection and immunity via vaccination at the start of the Delta wave.

3.2. Delta wave characteristics

The county-specific start dates for the Delta wave are mapped in Fig. 3 . The average start date was June 10, 2021, and start dates ranged from May 9th (Person County) to July 4th (Jones County); counties in the southern and western part of North Carolina generally experienced an earlier onset of the Delta wave compared with the northern and eastern counties. The average peak date for the Delta wave in North Carolina was September 3rd, 2021. The peak dates ranged from August 8th (Bladen County) to October 3rd (Wayne County), which are also mapped in Fig. 3. The county-level start and peak dates of the Delta wave are also plotted as a density plot in Fig. 3, showing the roughly 3 month difference between the start and peak dates and largely symmetrical distributions around the mean dates. A scatterplot is provided in Fig. 3(D) showing that, overall, counties that began the Delta wave on an earlier date had an earlier peak infection date.

Fig. 3.

(A) Start date and (B) peak date of Delta wave for each county, (C) density plot of the start and peak dates, and (D) scatterplot of start date and peak date.

The parameters from the county-level SIR models fit to the estimated infections are summarized in Table 1 . The county-level mean value for the β parameter was 4.08 with a standard deviation of 1.10; the mean value for the γ parameter was 1.29 with a standard deviation of 0.3. The county-level mean R0 value (calculated from the β and γ parameters) for the Delta wave was 3.18 with a standard deviation of 0.48. The distributions of the SIR model parameters are plotted in Fig. 4 . The β values were more dispersed than the γ values, which is expected given that β varies based on numerous factors including human behavior, environment, and contact rate (which all have the potential vary substantially from region to region) whereas γ describes the recovery rate of infected people (which should only vary depending on biological factors affecting recovery such as differences in the age distribution among counties or differences in the overall health status of county residents).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for parameter values from county-level SIR models.

| Parameter | Mean | SD | Median | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 4.08 | 1.10 | 3.9 | 1.05 |

| γ | 1.29 | 0.30 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| R0 | 3.18 | 0.48 | 3.2 | 0.58 |

| HIT (%) | 67.7 | 5.44 | 68.8 | 5.68 |

Fig. 4.

(A) Violin and box plots of β, γ, and R0 from the county-level SIR models and (B) map of R0 values with corresponding Herd Immunity Thresholds (HIT).

The county-level R0 values and corresponding HIT are mapped in Fig. 4; the R0 values range from a low of 2.0 (HIT = 50.0%) in Camden, Hoke, and Onslow Counties to a high of 4.22 (HIT = 76.3%) in Hyde, Montgomery, and Orange Counties. Overall, the map reveals high R0 values somewhat concentrated in the eastern part of North Carolina along with other counties with high R0 values found scattered across the state.

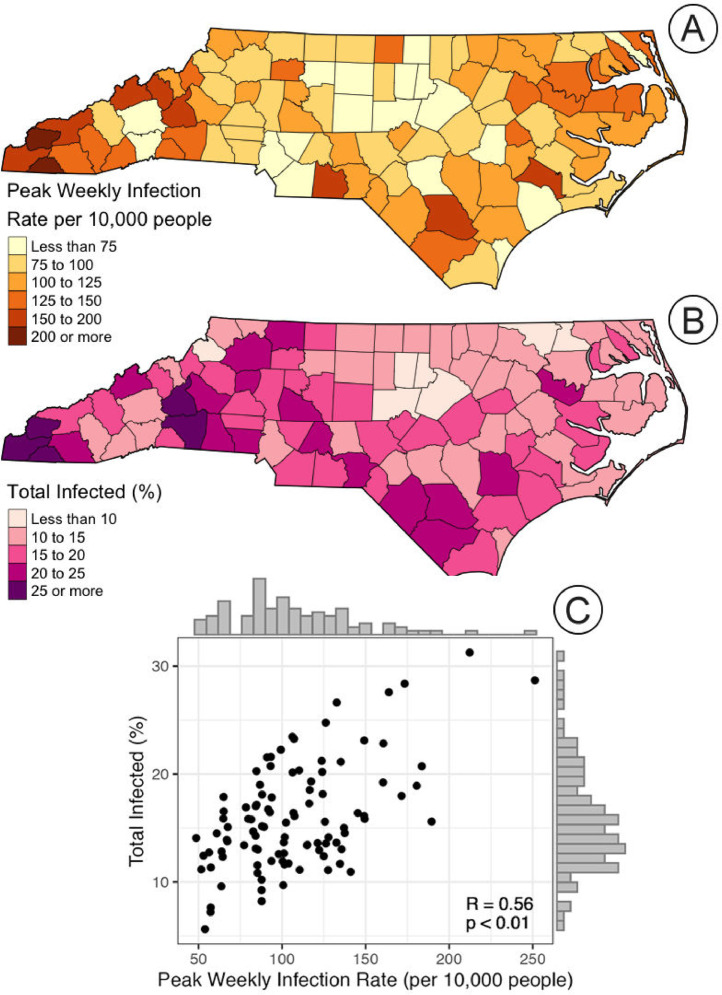

The county-specific peak weekly infection rates and the total percent of the population infected during the Delta wave are presented in Fig. 5 . The peak rate map captures the short-term intensity of the Delta wave, highlighting the regional variation across the state; the lowest peak rates are largely found in the central portion of the state, and the highest in the western, southern, and eastern portions of the state. The map of the total percent of the population infected during the Delta wave provides a different aspect of this portion of the pandemic, illustrating the overall infection burden in these regions. The counties with the highest percent infected appear to be generally located in the western and southern regions of the state. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the two maps appear quite similar; this is confirmed by the scatterplot and Pearson's R correlation test (R = 0.56, p < 0.01). Yet, this is not a perfect relationship, suggesting that the Delta wave may have had shorter and more intense in some regions (infecting a lower proportion of the total population than other regions that may have seen less intense, but sustained, transmission during the wave).

Fig. 5.

(A) Map of peak weekly infection rate per 10,000 people during the Delta wave, (B) map of the total percent of the population infected during the Delta wave, and (C) scatterplot comparing the two characteristics with correlation results (R = 0.56 and p < 0.01).

3.3. Comparisons

Scatterplots and the results of the Pearson's R correlation tests comparing immunity levels prior to the Delta wave (via prior infection, via vaccination, and total) to Delta wave outcomes (start date, peak infection rate, and total percent of population infected) are presented in Fig. 6 . Notably, total percent of a county's residents who were infected during the Delta wave was positively correlated (R = 0.34, p < 0.01) with the percent of the county's population with immunity from prior infection before the Delta wave; this means that the regions with the highest level of infections during earlier waves of the pandemic also had the highest infection levels during the Delta wave. There was no appreciable relationship among the other variables.

Fig. 6.

Scatterplots of Delta wave start date, peak weekly infection date during Delta wave (per 10,000 people), and percent of total population infected during the Delta wave with immunity by infection only, immunity by vaccination only, and total immunity (at the start of the Delta wave) for North Carolina counties. LOESS curves are included to help illustrate the nature of the relationships between the variables.

For immunity via vaccination, we found a slight positive relationship between the start date of the Delta wave and prior immunity due to vaccination (R = 0.27, p < 0.01), signaling that higher levels of vaccination uptake may have delayed the onset of the Delta wave. Counties with higher levels of immunity via vaccination also appeared to have better Delta wave outcomes, as we observed negative correlation with peak infection rate (R = -0.24, p = 0.01) and strong negative correlation with percent of the population infected (R = -0.47, p < 0.01).

The relationships among Delta wave characteristics and overall level of immunity prior to the wave were mixed due to the differences in the relationships with the underlying components of immunity (via infection and via vaccination). Accounting for all immunity, we did observe a positive relationship with the Delta wave start date (R = 0.23, p = 0.02); however, the relationships with peak infection rate and total percent of population infected were not notable (nor statistically significant).

3.4. Sensitivity analysis

The detailed results from the sensitivity analysis can be found in the Supplementary Material. Estimating infections using on the observed case counts resulted in higher values (overall) than doing so using observed deaths. Because the sensitivity analysis used the minimum and maximum potential overlap among people who had both been infected and vaccinated to calculate overall immunity in the population, the results varied (expectedly) from scenario to scenario.

The general nature of the county-level start and peak dates of the Delta wave was very similar to the main analysis for sensitivity scenarios S1, S2, S3 (those using the case counts to estimate infections); in all three, the both the start and peak dates were estimated to be slightly later than in the main analysis. In the scenarios using deaths to estimate infections, the start date for the Delta wave was much more distributed than in the main analysis; the peak dates overall were earlier than in the main analysis with a strong right skew on the distribution.

In the SIR model results, the county-level R0 values did not deviate substantially from the main analysis except in S2, which had extremely high R0 values because the scenario parameters (high infection estimates from cases and high prior immunity given the minimum overlap) resulted in extremely high estimates of immunity at the start of the Delta wave, thus requiring extremely high R0 values in order to have a large surge in infections in populations with high levels of prior immunity.

The sensitivity analysis of peak weekly infection rate and total infected during the Delta wave did produce some results quite different from the main analysis. Notably, in the set of results using case counts to estimate infections (S1, S2, S3), both the peak infection rate and total percent of the population infected during Delta were in the high range for more counties than the main analysis; further, the relationship between these two outcomes appeared to be stronger as well. In the other three scenarios (S4, S5, S6), the opposite results were found. More counties had a low value of peak infection rate and total infected. These results are unsurprising, given the infection estimates were higher than the main analysis for S1, S2, S3 and lower in S4, S5, S6.

Overall, the correlation results in the sensitivity analysis did not produce substantial deviations from the main analysis. While there were differences in the strength and statistical significance between some of the pairs of variables, the general takeaways were quite consistent with those from the main analysis.

4. Conclusions

This research adds to the quickly growing literature that has demonstrated concerningly high levels of geographic, demographic, and socioeconomic variation in uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine (e.g., Hughes et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2022; Murthy et al., 2021; Saelee et al., 2022) and what appears to be strong vaccine hesitancy to the COVID-19 vaccine in some regions of North Carolina. In the earliest stages of the Delta wave (roughly at the beginning of June 2021) more than half of North Carolina counties had uptake (completion) percentages lower than 40% of their total population, despite all people aged 12 and over being eligible to receive a vaccine at the time (NC.gov, 2021). While vaccine hesitancy is not a new phenomenon, the severe politicization of COVID-19 vaccination (and pandemic response in general) and vaccine misinformation campaigns led by the anti-vaccination movement and foreign actors have hindered vaccination efforts (Omer et al., 2021). As of June 2022, North Carolina had vaccinated 65.7% of eligible recipients (those aged 5 years and above), which ranked in the bottom half of states in the US (CDC, 2022b).

While the various “waves” of SARS-CoV-2 infections are often discussed as single entities, we demonstrated that the Delta wave in North Carolina had notable differences in its characteristics (start and peak date, R0, β and γ) and outcomes when interrogated at the county level. The results underscore the importance of considering geographic resolution and the near certainty that there will be regional differences in infection dynamics and population characteristics during epidemics. In this case, by constructing county-specific SIR models, we were able to account for these differences by allowing β and γ (and therefore R0) to vary while fitting the model to estimated county-level infection data. This approach offers clear advantages over models with fixed parameters, with the main one being the ability to account for regional differences in factors such as contact intensity and population age structure (which are implicitly captured in the β and γ parameters).

We examined whether levels of immunity prior to the Delta wave were associated with Delta wave characteristics and outcomes. Importantly, we examined overall immunity as well as separately for immunity via prior infection and via vaccination. While our finding that prior immunity via vaccination was negatively related with the Delta wave's peak infection rate and overall proportion of people infected during the wave was not surprising (Harris, 2021), finding a positive association between immunity from prior infection (prior to the Delta wave) and overall percent infected during the Delta wave was unexpected. This means that regions most affected in prior SARS-CoV-2 waves were again the most affected during the Delta wave. Whether these were the regions with the most infections in later waves remains to be examined, which is a clear pathway for extending this research.

There are several limitations in our analysis that deserve further discussion, the most important being the lack of observed data and the necessity of using modeled estimates to conduct the analysis. We had to estimate the number of people in each compartment of the SIR models, most notably the number of people who were immune to SARS-CoV-2 infection. While we attempted to use a robust approach to estimate immunity via prior infection (averaging estimates from two independent approaches), this may have led to under or overestimates of the actual infections given regional differences in testing availability and utilization, age structure, and presence of other medical conditions. Additionally, we assumed that all people infected gained immunity, which may have led to overestimating immunity levels. The vaccination data we used were also somewhat incomplete due to their ecological nature, as we were not able to explicitly link when a person received their initial dose and completion dose of the mRNA vaccines; this required another modeled estimate given the vaccines were partially effective after a single dose. Again, we averaged the two estimates in an effort to mitigate error if one of the estimates deviated largely from the true value. To estimate overall immunity in each county, we assumed that immunity from prior infection and immunity from vaccination were completely independent events. This could have led to either over or underestimations of the true values for each county; unfortunately, we could not locate any guidance on this matter and chose independence as the safest assumption. We are encouraged by the results of the sensitivity analysis, wherein we evaluated the impacts of our immunity estimation approach and alternate assumptions about the overlap in people who had both a prior infection and vaccination, which were consistent with the main findings.

Other limitations stem from our use of an SIR model; specifically, SIR models are highly simplified representations of infection dynamics and thus cannot capture the nuances of the extremely complex real-world processes that drive them. For example, our model did not account for age-dependent transmission or mortality, differences in transmissibility among people with symptomatic versus asymptomatic infections, or heterogeneity among the populations of each county. These provide opportunities for improvement in future models. Another limitation is that we did not account for people who become susceptible again after prior infection (moving from Recovered to Susceptible); this likely led to slight overestimates of the number of people immune. Finally, our model cannot be extended to examine the Omicron variant wave due to changes in vaccine efficacy, the presence of vaccine booster doses, and waning durability of immunity via prior infection or vaccination. Given the noted absence of observed data related to SARS-CoV-2 immunity, they are likely to be present in all similar research and present clear avenues for future study.

Our analysis highlights the substantial local and regional differences in responses to and outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic in North Carolina. We found that immunity via vaccination and infection (and overall) varied widely prior to the onset of the Delta wave, which ultimately led to differences in the nature of the Delta wave as it progressed through each county as well as the overall outcomes associated with this portion of the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we found that the Delta wave started and peaked at different times throughout the state and that short-term (peak infection rate) and long-term (total percent of the population infected during the wave) outcomes were heterogeneous across the state, resulting in a highly uneven geographic footprint of the Delta wave in North Carolina.

Source of support

This work was funded by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Grant 1K01AI151197. The funder played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgements (If any)

N/A.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.sste.2023.100566.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

All data is public and cited in the submission.

References

- Aphalo P.J., Slowikowski K., Mouksassi S. ggpmisc: Miscellaneous Extensions to “ggplot2” 2022.

- Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway E. Delta coronavirus variant: scientists brace for impact. Nature. 2021;595:17–18. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01696-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. CDC Museum COVID-19 Timeline 2022a. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html (accessed January 29, 2022).

- CDC. CDC COVID Data Tracker 2022b. https://www.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/index.html (accessed May 30, 2022).

- CDC. COVID-19 Pandemic Planning Scenarios 2021a. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/planning-scenarios.html (accessed February 21, 2022).

- CDC. Science Brief: SARS-CoV-2 Infection-induced and Vaccine-induced Immunity 2021b. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/vaccine-induced-immunity.html (accessed February 22, 2022).

- Delamater P.L., Street E.J., Leslie T.F., Yang Y.T., Jacobsen K.H. Complexity of the Basic Reproduction Number (R 0) Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:1–4. doi: 10.3201/eid2501.171901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine P.E.M. Herd Immunity: History, Theory, Practice. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:265–302. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J.E. COVID-19 Incidence and hospitalization during the delta surge were inversely related to vaccination coverage among the most populous U.S. Counties. Health Policy Technol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2021.100583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hass F.S., Jokar Arsanjani J. The Geography of the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Data-Driven Approach to Exploring Geographical Driving Forces. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2803. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18062803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q., Jackson S., Derakhshan S., Lee L., Pham E., Jackson A., et al. Urban-rural differences in COVID-19 exposures and outcomes in the South: A preliminary analysis of South Carolina. PLOS ONE. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M.M., Wang A., Grossman M.K., Pun E., Whiteman A., Deng L., et al. County-Level COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage and Social Vulnerability — United States, December 14, 2020–March 1, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:431–436. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7012e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C., Yee R., Bhatkoti R., Carranza D., Henderson D., Kuwabara S.A., et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Provider Access and Vaccination Coverage Among Children Aged 5–11 Years — United States, November 2021–January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:378–383. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7110a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Castro M.C. Spatiotemporal pattern of COVID-19 and government response in South Korea (as of May 31, 2020) Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A.A., Ionides E.L., Breto C., Ellner S.P., Ferrari M.J., Funk S., et al. pomp: Statistical Inference for Partially Observed Markov Processes 2022.

- Martcheva M. Vol. 61. Springer US; Boston, MA: 2015. (An Introduction to Mathematical Epidemiology). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy B.P., Sterrett N., Weller D., Zell E., Reynolds L., Toblin R.L., et al. Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Between Urban and Rural Counties — United States, December 14, 2020–April 10, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:759–764. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7020e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NC COVID-19. 2022. https://www.nc-covid.org (accessed January 29, 2022).

- NCDHHS. Data Behind the Dashboards 2022. https://covid19.ncdhhs.gov/dashboard/data-behind-dashboards (accessed January 30, 2022).

- NC.gov. COVID-19 Orders & Directives 2022. https://www.nc.gov/covid-19/covid-19-orders-directives#secretarial-orders,-directives-&-advisories%E2%80%8B (accessed January 29, 2022).

- NC.gov. FDA and CDC Authorize Pfizer COVID-19 Vaccine for Children Age 12 and Older 2021. https://www.ncdhhs.gov/news/press-releases/fda-and-cdc-authorize-pfizer-covid-19-vaccine-children-age-12-and-older (accessed May 31, 2022).

- Oliver S.E., Gargano J.W., Scobie H., Wallace M., Hadler S.C., Leung J., et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Interim Recommendation for Use of Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine — United States, February 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:329–332. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7009e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omer S.B., Benjamin R.M., Brewer N.T., Buttenheim A.M., Callaghan T., Caplan A., et al. Promoting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: recommendations from the Lancet Commission on Vaccine Refusal, Acceptance, and Demand in the USA. The Lancet. 2021;398:2186–2192. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02507-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilishvili T., Fleming-Dutra K.E., Farrar J.L., Gierke R., Mohr N.M., Talan D.A., et al. Interim Estimates of Vaccine Effectiveness of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 Vaccines Among Health Care Personnel — 33 U.S. Sites, January–March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:753–758. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7020e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese H., Iuliano A.D., Patel N.N., Garg S., Kim L., Silk BJ, et al. Estimated Incidence of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Illness and Hospitalization—United States, February–September 2020. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1780. e1010–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Redwood R., Kitchin R., Apostolopoulou E., Rickards L., Blackman T., Crampton J., et al. Geographies of the COVID-19 pandemic. Dialogues Hum Geogr. 2020;10:97–106. doi: 10.1177/2043820620936050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saelee R., Zell E., Murthy B.P., Castro-Roman P., Fast H., Meng L., et al. Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Between Urban and Rural Counties — United States, December 14, 2020–January 31, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:335–340. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7109a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi A., Khavarian-Garmsir A.R. The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management. Sci Total Environ. 2020;749 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiehzadegan S., Alaghemand N., Fox M., Venketaraman V. Analysis of the Delta Variant B.1.617.2 COVID-19. Clin Pract. 2021;11:778–784. doi: 10.3390/clinpract11040093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau Data Releases. CensusGov. 2022 https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/news/data-releases.html (accessed May 31, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer C., Jacobs A. Omicron: What We Know About the New Coronavirus Variant. N Y Times. 2022 https://www.nytimes.com/article/omicron-coronavirus-variant.html (accessed February 22, 2022) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data is public and cited in the submission.