Abstract

Introduction

The operational definitions of treatment response, partial response, and remission in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are widely used in clinical trials and regular practice. However, the clinimetric sensitivity of these definitions, that is, whether they identify patients that experience meaningful changes in their everyday life, remains unexplored.

Objective

The objective was to examine the clinimetric sensitivity of the operational definitions of treatment response, partial response, and remission in children and adults with OCD.

Methods

Pre- and post-treatment data from five clinical trials and three cohort studies of children and adults with OCD (n = 1,528; 55.3% children, 61.1% female) were pooled. We compared (1) responders, partial responders, and non-responders and (2) remitters and non-remitters on self-reported OCD symptoms, clinician-rated general functioning, and self-reported quality of life. Remission was also evaluated against post-treatment diagnostic interviews.

Results

Responders and remitters experienced large improvements across validators. Responders had greater improvements than partial responders and non-responders on self-reported OCD symptoms (Cohen's d 0.65–1.13), clinician-rated functioning (Cohen's d 0.53–1.03), and self-reported quality of life (Cohen's d 0.63–0.73). Few meaningful differences emerged between partial responders and non-responders. Remitters had better outcomes across most validators than non-remitters. Remission criteria corresponded well with absence of post-treatment diagnosis (sensitivity/specificity: 93%/83%). Using both the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) and the Clinical Global Impression Scale yielded more conservative results and more robust changes across validators, compared to only using the Y-BOCS.

Conclusions

The current definitions of treatment response and remission capture meaningful improvements in the everyday life of individuals with OCD, whereas the concept of partial response has dubious clinimetric sensitivity.

Keywords: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, Response, Partial response, Remission, Recovery

Introduction

After decades of inconsistent definitions of treatment response, remission, recovery, and relapse in clinical trials of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), the field recently converged to endorse a set of conceptual and operational definitions [1]. These definitions have received additional empirical support [2] and are now widely used in clinical trials and regular practice; this has improved the comparability across treatment studies and communication between researchers, clinicians, and patients. However, an unexplored property of the definitions is their clinimetric sensitivity, which refers to the ability of a measure to identify clinically meaningful groups of patients [3, 4]. In the context of response and remission, this translates into the ability of the definitions to discriminate between groups of individuals who experience broad and meaningful improvements in everyday life versus those who require further treatment or follow-up.

The aim of this study was to examine the clinimetric sensitivity of the operational definitions of treatment response and remission in OCD. We leveraged a large sample of children and adults with OCD and examined to what extent individuals classified as responders, partial responders, or remitters experienced clinically meaningful improvements across three validators: self-reported OCD symptoms, clinician-rated general functioning, and self-reported quality of life (QoL).

Materials and Methods

Participants

We pooled data from 5 Swedish randomized controlled trials and 3 cohort studies [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11] resulting in a sample of 1,528 well-characterized children and adults with OCD (55.3% children; 61.1% female). All participants were assessed at specialist clinics prior to and after evidence-based interventions for OCD (i.e., cognitive-behaviour therapy and/or pharmacotherapy) or control conditions (e.g., waitlist). A wide range of study designs and treatment conditions, including control conditions in randomized controlled trials, were pooled to maximize variation in outcome. Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of the full sample are presented in the online supplementary Table S1 (for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000527115). All studies were approved by appropriate ethical review boards. All participants provided written informed consent (or assent if younger than 15).

Measures

Diagnostic Interviews

OCD diagnoses were confirmed at intake by multidisciplinary clinical or research teams using the DSM-IV or DSM-5 versions of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM − Axis I disorders (SCID-I) [12] or the child or adult version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview [13]. A subsample of participants (n = 214) [5, 6] had diagnostic SCID-I interviews conducted after treatment, providing an opportunity for diagnostic validation of the remission definitions.

Operational Definitions

The international expert consensus definitions of response and partial response [1] are based on a combination of pre-to-post changes on the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) [14, 15] and post-treatment scores on the Clinical Global Impression Scale − Improvement (CGI-I) [16]. Remission is defined by combining post-treatment Y-BOCS and post-treatment Clinical Global Impression Scale − Severity (CGI-S) [16] scores (Table 1).

Table 1.

Consensus definitions and operationalization of treatment response, partial response, and remission in OCD (from Mataix-Cols et al. [1])

| Conceptual definition | Operationalization | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment Response | A clinically meaningful reduction in symptoms (time, distress, and interference associated with obsessions, compulsions, and avoidance) relative to baseline severity in an individual who meets diagnostic criteria for OCD | A ≥35% reduction in Y-BOCS scores plus CGI-I rating of 1 (“very much improved”) or 2 (“much improved”), lasting for at least 1 week |

|

| ||

| Partial Response | As above | A ≥25% but <35% reduction in Y-BOCS scores plus CGI-I rating of at least 3 (“minimally improved”), lasting for at least 1 week |

|

| ||

| Remission | The patient no longer meets syndromal criteria for the disorder and has no more than minimal symptoms. Residual obsessions, compulsions, and avoidance may be present but are not time consuming and do not interfere with the person's everyday life | If a structured diagnostic interview is feasible, the person no longer meets diagnostic criteria for OCD for at least 1 week If a structured diagnostic interview is not feasible, a score of <12 on the Y-BOCS plus CGI-S rating of 1 (“normal, not at all ill”) or 2 (“borderline mentally ill”), lasting for at least 1 week |

CGI-I, Clinical Global Impression Scale − Improvement; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression Scale − Severity; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; Y-BOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale.

Clinical Validators

Self-reported symptom severity was assessed using the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory − Revised (OCI-R) for adults and the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory − Child Version (OCI-CV) for children and adolescents [17, 18]. Scores ≥18 points on the OCI-R and ≥11 points on the OCI-CV denote caseness [17, 19]. Global psychosocial functioning was assessed using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) for adults and the Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) for youth [20, 21]. Scores equal to or below 60 on both measures denote moderately impaired function. Subsets of participants self-reported their QoL using the EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) for adults and the Child Health Utility Instrument (CHU9D) for children [22, 23]. To our knowledge, there are no established cut-offs for these QoL instruments.

Statistical Analysis

Paired-samples t tests and Cohen's d effect sizes (small = 0.2, medium = 0.5, large = 0.8) were used to analyse changes within groups. Between-group differences were examined using two-way repeated measures ANOVA models and effect sizes were evaluated using partial eta squared (η2; small = 0.01, medium = 0.06, large = 0.14). An alpha level of 0.05 was used as an indicator of statistical significance and the Holm-Bonferroni method was used for follow-up pairwise comparisons. For the sub-sample with available structured diagnostic interviews at post-treatment (n = 214), sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were calculated.

While the use of the Y-BOCS is widespread, the CGI-I and CGI-S are not always used in clinical trials or routine clinical care. We therefore examined whether the Y-BOCS alone was equally sensitive as the recommended combination of Y-BOCS plus CGI-I (response) or CGI-S (remission) by comparing the subgroup of individuals who were differentially classified using one or both instruments.

Results

Classification

The operational definitions classified 888 participants (58.2%) as treatment responders, 173 (11.3%) as partial responders, and 464 (30.4%) as non-responders. Further, 577 participants (37.9%) were classified as being in remission and 944 (61.1%) as not being in remission.

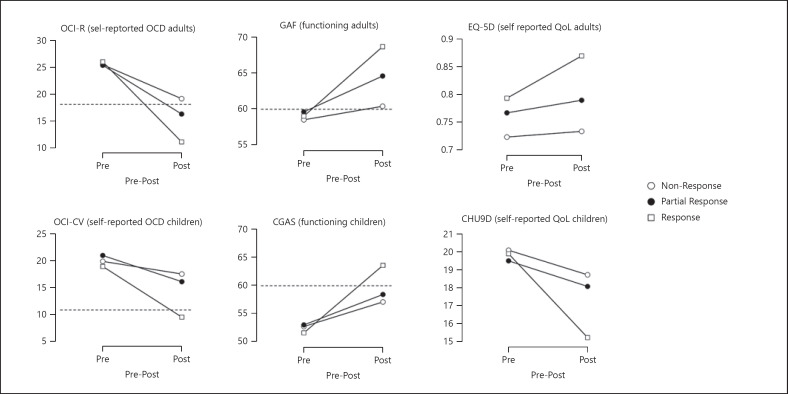

Self-Reported OCD Symptoms

All groups improved significantly (ps < 0.01), but improvement was largest in responders (d adults = 1.44, d children = 1.27), followed by partial responders (d adults = 1.03, d children = 0.65), and non-responders (d adults = 0.74, d children = 0.37). Significant two-way interactions emerged in both children and adults (η2 adults = 0.143, η2 children = 0.143, see Fig. 1 for descriptive data). No between-group differences were observed at pre-treatment in either adults or children. Adult responders had lower post-treatment scores than partial responders (pholm = 0.001, d = 0.65) and non-responders (pholm < 0.001 Cohen's, d = 0.85), with no significant difference between the two latter groups (pholm = 0.25 d = 0.26). In children, responders had lower post-treatment scores than partial responders (pholm < 0.001, d = 0.91) and non-responders (pholm < 0.001, d = 1.13), with no significant difference between the two latter groups (pholm = 0.81, d = 0.18).

Fig. 1.

Pre-to-post treatment changes across validators in responders, partial responders, and non-responders. The dashed lines indicate cut-off values that best separate clinical from non-clinical cases (not available for QoL measures). CGAS, Children's Global Assessment Scale; CHU9D, Child Health Utility Instrument; EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 Dimension; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; OCI-CV, Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory − Child Version; OCI-R, Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory − Revised.

General Functioning

All groups improved significantly (ps < 0.01), with the largest improvement among responders (d adults = 1.17, d children = 1.42), followed by partial responders (d adults = 0.57, d children = 0.64), and non-responders (d adults = 0.24, d children = 0.62). Significant two-way interactions emerged for children and adults (η2 adults = 0.155, η2 children = 0.146, see Fig. 1). No between-group differences were observed at pre-treatment in either adults or children. Adult responders had better post-treatment functioning than partial responders (d = 0.53) and non-responders (d = 1.03); and partial responders had better functioning than non-responders (d = 0.55). In children, responders had better post-treatment functioning than partial responders (d = 0.55) and non-responders (d = 0.70); no significant difference emerged between the two latter groups (pholm = 0.64, d = 0.14).

Self-Reported QoL

Only the responder group improved significantly on self-reported QoL (ps < 0.001, d adults = 0.40, d children = 0.90). There was no statistically significant two-way interaction between group and time in adults (F(2, 205) = 2.40, p = 0.09, η2 = 0.023), but follow-up comparisons showed that responders had better QoL than non-responders at post-treatment (d = 0.78). In children, there was a significant two-way interaction between group and time (η2 = 0.085). Follow-up comparisons showed that the groups did not differ significantly at pre-treatment. At post-treatment, responders had better QoL than non-responders (d = 0.63).

Remission

Both remitters and non-remitters improved significantly on all outcome measures (ps < 0.05), but effect sizes favoured remitters: self-reported OCD (d for adult remitters/non-remitters = 1.27/1.06, d for child remitters/non-remitters = 1.31/0.69), general functioning (d for adult remitters/non-remitters = 1.56/0.55, d for child remitters/non-remitters = 1.48/0.86), and QoL (d for adult remitters/non-remitters = 0.39/0.21, d for child remitters/non-remitters = 0.88/0.37). There were significant two-way interactions for all measures except for self-reported QoL in adults (EQ-5D, p = 0.41). The observed differences favoured remitters and ranged from very small/small (η2 for EQ-5D = 0.003; η2 for OCI-R = 0.037; η2 for CHU9D = 0.057) to moderate/large (η2 for OCI-CV = 0.092; η2 for GAF = 0.171; η2 for CGAS = 0.171) (see online supplementary Figure S1 for a graphical depiction of these results).

Among the 214 adult participants who were assessed with a diagnostic interview after treatment, 69 (32.2%) no longer met criteria for OCD. Of these, 64 (92.8%) were classified as remitters according to the operational criteria (sensitivity: 92.8%, specificity: 83.4%, positive predictive value: 72.7%, negative predictive value: 96.0%).

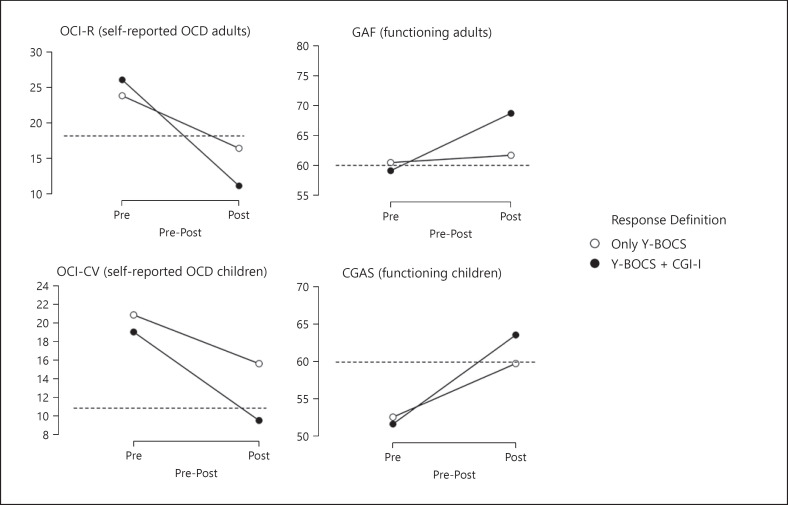

Are the Y-BOCS and the CGI Both Needed?

For response versus non-response, 1,447 participants (94.9%) were identically classified using the combination of the Y-BOCS and the CGI-I versus the Y-BOCS alone. When only the Y-BOCS was used, the number of treatment responders increased from 888 to 966, an increase of 8.9%. The group that was differentially classified using one versus both instruments (n = 78) was compared to the group who received the same classification using both instruments (n = 1,447). Results are graphically presented in Figure 2. Significant two-way interactions were present for all measures with mostly small between-group effect sizes (η2 OCI-R = 0.031; η2 OCI-CV = 0.019; η2 GAF = 0.054; η2 CGAS = 0.023), indicating larger improvement in those classified as responders using a combination of both instruments. QoL was not examined due to insufficient participants with eligible data.

Fig. 2.

Pre-to-post treatment changes in self-reported obsessive-compulsive symptom severity and clinician-rated functioning when using only Y-BOCS scores compared to Y-BOCS + CGI-I scores to define treatment response. The dashed lines indicate cut-off values that best separate clinical from non-clinical cases. CGAS, Children's Global Assessment Scale; CGI-I, Clinical Global Impression Scale − Improvement; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; OCI-CV, Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory − Child Version; OCI-R, Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory − Revised; Y-BOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale.

For remission, 577 participants were classified as remitters using both definitions (Y-BOCS + CGI-S vs. Y-BOCS score only), and an additional 241 when only the Y-BOCS was used, an increase of 41.8%. When contrasting these two groups, significant two-way interactions emerged for general functioning (η2 GAF = 0.225; η2 CGAS = 0.072). No significant two-way interaction emerged for OCI-R (p = 0.71) and a borderline significant difference for OCI-CV (p = 0.049, η2 = 0.014; see online supplementary Fig. S2).

Discussion

This study is the first clinimetric evaluation of existing operational definitions of treatment response, partial response, and remission in OCD. Individuals identified as responders had significantly better outcomes across validators than partial responders and non-responders, with few statistically significant differences between the two latter groups. At post-treatment, only responders systematically scored below established cut-offs for self-reported OCD severity and above established cut-offs for general function. Similarly, remitters had better outcomes across most validators, compared to non-remitters, and the operational criteria for remission corresponded well with absence of diagnosis at post-treatment. These results indicate that clinicians and researchers using these operational definitions can be reassured that patients meeting strict response or remission criteria have experienced meaningful improvements in various areas of life, including general function and subjective ratings of symptom severity and QoL. Therefore, the current definitions of (full) treatment response and remission in OCD are well suited to guide clinical decision-making (e.g., to help decide whether to continue treatment or initiate follow-up) and can be used in clinical trials to increase transparency and facilitate cross-trial comparisons.

In most analyses, partial responders showed similar outcomes as non-responders. Thus, the clinimetric sensitivity of the partial response definition is limited. We propose that it may be best to adopt a conservative approach and consider partial responders as non-responders. This will clearly signal the need for additional treatment in this group.

We also found that, while it is possible to obtain reasonable results when operational definitions are based solely on the Y-BOCS, this will likely result in an overestimation of treatment response by approximately 9% and remission by approximately 42%. We strongly recommend the use of both the Y-BOCS and the CGI-I/S, whenever possible.

The main strength of this study is the use of a high-quality dataset from individuals diagnosed in specialist clinics across Sweden and the use of a clinimetric approach which prioritized broad outcomes that matter to patients. Despite the large sample size, some sub-analyses may have been underpowered. The use of additional validators, such as family function, educational attainment, or employment, would be an important next step. Further work is needed on the clinimetric definition of recovery, a concept which includes not only sustained remission but also psychological well-being [24], in individuals with OCD. To conclude, the current definitions of treatment response and remission capture meaningful improvements in the everyday life of individuals with OCD, whereas the concept of partial response has dubious clinimetric sensitivity.

Statement of Ethics

Each of the studies included in this secondary analysis was reviewed and approved by their respective Ethics Committees in Stockholm and Lund. Stockholm Regional Ethics Board reference numbers: 2010/1750-31/1; 2014/673-31/2; 2014/1897-31; 2011/1620-31/2; 2017/1070/31-1; and 2015/1099-31/2. Lund Regional Ethics Board reference numbers: 2015/663 and 2016/394. All participants in each of the included cohorts provided written informed consent (or assent if younger than 15).

Conflict of Interest Statement

Prof. Mataix-Cols receives royalties for contributing articles to UpToDate, Wolters Kluwer Health, outside of the submitted work. Dr. Fernández de la Cruz receives royalties for contributing articles to UpToDate, Wolters Kluwer Health and personal fees from Elsevier for editorial work, both outside the submitted work. Dr. Andersson receives royalties from Natur & Kultur from a self-help book on health anxiety, outside of the submitted work. Prof. Rück receives book royalties from Natur & Kultur and Studentlittertur, outside the submitted work. Dr. Cervin receives financial compensation from Springer for editorial work, outside of the submitted work. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding Sources

The Swedish OCD genetics study was funded by grants from the Swedish Research Council (2015-02271, 2018-02487, and 2020-01343) and the NIMH (R01MH110427). The Lenhard et al. [7] (2017) trial was funded by Stockholm County Council (PPG project 20120167, 20140085), Swedish Research Council and Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (2014-4052), and the Jane and Dan Olsson Foundation. Prof. Serlachius was supported by Region Stockholm (clinical research appointment, Grant No. 20170605). Dr. Aspvall was supported by grants from Drottning Silvias Jubileumsfond, Fonden för psykisk hälsa, and Fredrik och Ingrid Thurings stiftelse. The Aspvall et al. [10] (2021) trial was funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (Grant No. 2014-4052), ALF Medicin Project Grant by Region Stockholm (Grant No. 20160247), and Jane and Dan Olssons Foundation (Grant No. 2016-64). The Lundström et al. [11] (2022) study was funded by grants from the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, the Swedish Medical Association, and the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet. Dr. Cervin was supported by grants from the L.J. Boëthius Foundation, the Lindhaga Foundation, the Jerring Foundation, and Region Skåne.

Author Contributions

David Mataix-Cols and Matti Cervin conceived and designed the study. David Mataix-Cols, Mattin Cervin, Erik Andersson, James J. Crowley, Christian Rück, and Eva Serlachius obtained grant funding. Erik Andersson, Kristina Aspvall, Julia Boberg, Elles de Schipper, Oskar Flygare, Eikaterina Ivanova, Fabian Lenhard, Lorena Fernández de la Cruz, and Lina Lundström collected data. Matti Cervin performed the statistical analyses. David Mataix-Cols drafted the manuscript. All authors provided critical comments on the manuscript and approved its final version for submission.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are not publicly available due to their sensitive nature. Data sharing for some of the included datasets may be possible depending on ethical approval. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Funding Statement

The Swedish OCD genetics study was funded by grants from the Swedish Research Council (2015-02271, 2018-02487, and 2020-01343) and the NIMH (R01MH110427). The Lenhard et al. [7] (2017) trial was funded by Stockholm County Council (PPG project 20120167, 20140085), Swedish Research Council and Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (2014-4052), and the Jane and Dan Olsson Foundation. Prof. Serlachius was supported by Region Stockholm (clinical research appointment, Grant No. 20170605). Dr. Aspvall was supported by grants from Drottning Silvias Jubileumsfond, Fonden för psykisk hälsa, and Fredrik och Ingrid Thurings stiftelse. The Aspvall et al. [10] (2021) trial was funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (Grant No. 2014-4052), ALF Medicin Project Grant by Region Stockholm (Grant No. 20160247), and Jane and Dan Olssons Foundation (Grant No. 2016-64). The Lundström et al. [11] (2022) study was funded by grants from the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, the Swedish Medical Association, and the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet. Dr. Cervin was supported by grants from the L.J. Boëthius Foundation, the Lindhaga Foundation, the Jerring Foundation, and Region Skåne.

References

- 1.Mataix-Cols D, Fernández de la Cruz L, Nordsletten AE, Lenhard F, Isomura K, Simpson HB. Towards an international expert consensus for defining treatment response, remission, recovery and relapse in obsessive-compulsive disorder. World Psychiatry. 2016 Feb;15((1)):80–1. doi: 10.1002/wps.20299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farhat LC, Vattimo EF, Ramakrishnan D, Levine JL, Johnson JA, Artukoglu BB, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: an empirical approach to defining treatment response and remission in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;61((4)):495–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2021.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fava GA, Tomba E, Sonino N. Clinimetrics: the science of clinical measurements. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66((1)):11–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrozzino D, Patierno C, Guidi J, Berrocal Montiel C, Cao J, Charlson ME, et al. Clinimetric criteria for patient-reported outcome measures. Psychother Psychosom. 2021;90((4)):222–32. doi: 10.1159/000516599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson E, Enander J, Andrén P, Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Hursti T, et al. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2012 Oct;42((10)):2193–203. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson E, Hedman E, Enander J, Radu Djurfeldt D, Ljótsson B, Cervenka S, et al. D-cycloserine vs placebo as adjunct to cognitive behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder and interaction with antidepressants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72((7)):659–67. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lenhard F, Andersson E, Mataix-Cols D, Rück C, Vigerland S, Högström J, et al. Therapist-guided, internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017 Jan;56((1)):10–9.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.09.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cervin M, Perrin S. Incompleteness and disgust predict treatment outcome for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Ther. 2020;52((1)):53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2020.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mataix-Cols D, Hansen B, Mattheisen M, Karlsson EK, Addington AM, Boberg J, et al. Nordic OCD & related disorders consortium: rationale, design, and methods. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2020;183((1)):38–50. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aspvall K, Andersson E, Melin K, Norlin L, Eriksson V, Vigerland S, et al. Effect of an internet-delivered stepped-care program vs in-person cognitive behavioral therapy on obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms in children and adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021 May 11;325((18)):1863–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundström L, Flygare O, Andersson E, Enander J, Bottai M, Ivanov VZ, et al. Effect of internet-based vs face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5((3)):e221967. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lobbestael J, Leurgans M, Arntz A. Inter-rater reliability of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID I) and Axis II disorders (SCID II) Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18((1)):75–9. doi: 10.1002/cpp.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RD, Janavs J, Bannon Y, Rogers JE, et al. Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID) J Clin Psychiatry. 2010 Mar;71((3)):313–26. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006–11. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, Ort SI, King RA, Goodman WK, et al. Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997 Jun;36((6)):844–52. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Institute of Mental Health . ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Washington: U.S. Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S, Langner R, Kichic R, Hajcak G, et al. The obsessive-compulsive inventory: development and validation of a short version. Psychol Assess. 2002;14((4)):485–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foa EB, Coles M, Huppert JD, Pasupuleti RV, Franklin ME, March J. Development and validation of a child version of the obsessive compulsive inventory. Behav Ther. 2010 Mar;41((1)):121–32. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rough HE, Hanna BS, Gillett CB, Rosenberg DR, Gehring WJ, Arnold PD, et al. Screening for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder using the obsessive-compulsive inventory-child version. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2020;51((6)):888–99. doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-00966-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, et al. A children's global assessment scale (CGAS) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983 Nov;40((11)):1228–31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33((5)):337–43. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furber G, Segal L. The validity of the Child Health Utility instrument (CHU9D) as a routine outcome measure for use in child and adolescent mental health services. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13((1)):22. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fava GA. The concept of recovery in affective disorders. Psychother Psychosom. 1996;65((1)):2–13. doi: 10.1159/000289025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are not publicly available due to their sensitive nature. Data sharing for some of the included datasets may be possible depending on ethical approval. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.