As one of the most severe forms of ocular trauma, open-globe injury (OGI) causes significant vision loss. Timely and meticulous repair of these injuries can improve patient outcomes. This video-based educational curriculum is intended to serve as an efficient yet comprehensive reference for OGI repair. We hope that these video-based articles help surgeons and trainees from around the world find answers to specific surgical questions in OGI management. The curriculum has been divided into six separate review articles, each authored by a different set of authors, to facilitate a systematic and practical approach to the subject of wound types and repair techniques. This third article highlights the use of antibiotics before, during, and after surgery; suture selection; surgical knots, and “ship-to-shore” suturing.

Curriculum Editors

Preoperative, Intraoperative, and Postoperative Antibiotics

Surgical repair of an open-globe injury (OGI) is critical to improving function, preserving vision, and reducing risk of infection after traumatic eye injury. Antibiotic therapy also plays a critical role in achieving good outcomes. In the absence of prophylactic antibiotic use, post-traumatic endophthalmitis occurs in approximately 10% of cases, whereas use of antibiotics may reduce the rate of endophthalmitis to as low as 0.9%.1,2 The most common infectious agents are Gram positive cocci (eg, streptococcus, coagulase-negative staphylococcus), bacillus species, and fungi.3 Additionally, risk factors for endophthalmitis include delay of closure beyond 24 hours, wound contamination, retained intraocular foreign body (IOFB), involvement of the lens capsule, and trauma occurring in a rural setting.4

Preoperative Antibiotics

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated as early as possible from the onset of initial injury to reduce the risk of possible infection. Two common, broad-spectrum agents employed at Massachusetts Eye and Ear are intravenous vancomycin (15 mg/kg for children or ∼1 g twice daily for a total of 4 doses) and a third-generation cephalosporin (ceftazidime 50 mg/kg for children or ∼1g three times daily for a total of 6 doses), for a total treatment duration of 48 hours.5,6 This standardized treatment regimen covers the majority of bacterial etiologies. In patients with penicillin allergies, fluoroquinolones may be used instead. Tabatabaei and colleagues7 found no difference between oral and intravenous antibiotic administration in occurrence of endophthalmitis or visual acuity at 1 year’s follow-up. Thus, in circumstances without capacity for intravenous medications, and when transfer to an outside hospital might require several hours, initiation of an oral regimen may be appropriate.

Antifungal prophylaxis is not routinely administered unless there is a high risk, as, for example, in cases of intraocular foreign organic material. Clinical trials have shown similar efficacy of oral fluoroquinolones as well as intravitreal vancomycin and ceftazidime or intravitreal clindamycin and gentamicin.6 However, unless there is an IOFB or suspicion for endophthalmitis, the potential benefits of intravitreally injected medications in the context of limited proven benefit do not outweigh the risks, offering no compelling rationale for routine administration.

The possibility of a Clostridium tetani infection may occur in patients with complicated perforating wounds; thus, tetanus post-exposure prophylaxis is recommended.8,9

Intraoperative Antibiotics

During surgical repair of zone I injuries, where the anterior segment can be safely manipulated, intracameral moxifloxacin may be used. Moxifloxacin has been found to be effective against other similar microorganisms that are encountered in routine anterior segment surgery.10 At the conclusion of repair, a subconjunctival injection of cefazolin (100 mg/0.5 mL) and dexamethasone (400 mcg/0.1 mL) is commonly used, administered away from the site of injury.

Postoperative Antibiotics

In tandem with cycloplegic agents and corticosteroid topical therapy, a topical antibiotic is routinely used. The common agents are the fluoroquinolones (eg, moxifloxacin, ofloxacin), applied at a frequency per physician or institutional protocol in the injured eye. If necessary and as an alternative, combination drops or ointment (ie, antibiotic and corticosteroid) may also be used.

In the postoperative phase, broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic therapy should be continued for a total of 48 hours.

Discharge Antibiotics

Beginning on postoperative day 1, as mentioned above, topical antibiotic therapy is initiated postoperatively. We continue this for a total of 1 week.6

(NS, GWA)

Suture Selection

OGIs can involve any structure of the eye, and proper surgical repair requires choosing the appropriate suture (including material, size, and needle) for a given wound type. Nylon monofilament suture is a nonabsorbable, minimally reactive suture producing little scarring; loss of tensile strength because of hydrolysis occurs very gradually.11 Nylon is the preferred suture for primary wound closure in OGI, because it is nonabsorbable and can remain permanently in scleral wounds and be removed gradually from corneal wounds. For corneal wounds, 10-0 nylon sutures are used to achieve the best optical outcome12; 9-0 nylon is used for limbal lacerations and 8-0 nylon is used for scleral lacerations. No matter the size of the suture, a spatulated needle is recommended in OGI repair: the flat tip on the upper and lower surfaces allows precise depth control through the sclera and cornea.13 It is important to be aware that the lateral edges are the sharp “cutting edges,” and care should be taken not to inadvertently widen a tunnel while passing the suture.

Silk is a nonabsorbable braided suture with easy maneuverability, but it has increased risk of bacterial infectivity. Thus, it should not be used for primary wound closure; however, it can be useful for manipulating the eye during surgery. A 4-0 silk suture on a reverse cutting needle may be used for limbal fixation in order to manipulate the globe for more posterior repairs, and 4-0 silk on a tapered needle can be useful for retracting lids when the injury impedes the use of a conventional eyelid retractor, as could be the case after severe eyelid trauma. Finally, 2-0 silk can be threaded through a Gass hook and used to isolate extraocular muscles for further globe control and exposure.

Polyglactin 910 is a braided absorbable suture that offers wound support for 7–10 days and fully dissolves after 60–90 days. Muscle disinsertion and reattachment may be necessary in complex zone III lacerations; commonly a 6-0 polyglactin 901 double-armed suture on a spatulated needle is used to secure the muscle. For conjunctival repair, an 8-0 polyglactin 910 suture is useful, given its rapid dissolvability. Some surgeons argue that the absorbable and pro-inflammatory properties of polyglactin sutures preclude its use for primary open-globe injury repair.

Choosing the appropriate suture gives a surgeon the best opportunity to successfully close the globe. Video 1 provides examples of the various sutures discussed above (see also Appendix 1).

Video 1.

Examples of the various sutures.

(MCW, CMM)

Surgical Knots

Proper suturing and knot tying technique is necessary to ensure proper wound closer, maintain suture tension during healing, and prevent wound leak. It is important to ensure wounds are water tight as wound leaks are associated with higher rates of microbial keratitis and endophthalmitis.14 Note, all techniques below are described for a right-handed surgeon.

Surgeon’s Knot

The surgeon’s knot is a variation on the simple square knot that prevents loss of tension prior to the second throw.15 Surgeon’s knots are described according to the number of loops in each throw, most commonly 2-1-1. Nylon suture, because of the low friction, will often require a 3-1-1.11 Video 2 illustrates the surgeon’s knot (see also Appendix 2).

First, the needle is passed right-to-left through both sides of the wound, the needle is released, and the forceps (in the left hand) are used to grasp the longer suture end (ie, with the needle still attached). The forceps should grasp the suture at an acute angle, such that the suture is an extension of the forceps. A second set of forceps or the needle driver, in the right hand, is then placed in the center or “valley” of the knot, with the jaws closed and parallel to the wound. The forceps are used to wrap the long end of the suture inward toward the center of the knot (clockwise in this example) around the jaws of the needle driver at least twice (the number varies based on suture type and wound tension). While maintaining the loops around the needle driver, the second forceps or needle driver’s jaws are opened and used to grasp the short tail end of the suture. The tail is then pulled toward the surgeon while the long end is pulled away from the surgeon. Enough tension should be applied such that the walls of the wounds approximate.

The short and long ends should now be on opposite sides from where they started. The needle driver is placed in the center of the wound, jaws closed, parallel to the wound. The forceps are used to wrap the suture once, inward, toward the center of the knot (counterclockwise in this example) around the jaws of the needle driver. The jaws of the needle driver are then opened and used to grasp the tail of the suture while maintaining the single loop over the jaws, and this is pulled tight. With nylon suture, it can be useful to pull at a 90° angle to the direction of the suture embedded in the tissue.

Further single throws can be added for additional knot security. The long end will always be wrapped around the needle driver, such that it is rotated inward toward the center of the knot (in this example the next loop would be clockwise and the following loop would be counterclockwise, and so on). Typically, one more single throw is placed to complete the 2-1-1 or 3-1-1 knots that are used in globe closure.

Video 2.

Surgeon’s knot.

Slip Knot

A slip knot uses a 1-1-1 knot and is useful in corneal wounds since the knot tension can be adjusted at any time, particularly if the final tension is to be determined at the end of the closure. When a corneal laceration is large or complex, requiring multiple sutures, it can be difficult to gauge the appropriate tension when starting the closure. All sutures are left adjustable until the final tensions are appropriate across the length of the wound, at which time they are locked down. Sutures that are too tight can cause astigmatism, whereas sutures that are too loose may allow wound leakage. Additionally, the 1-1-1 knot results in a much smaller knot that is easier to rotate and bury in the corneal stroma. The knot is constructed with three single overhand knots; however, the first two knots are tied in the same direction. As the name implies, the knot can be “slipped” along the suture to tighten or loosen the tension prior to placing the third and final throw. Video 3 illustrates the slip knot (see also Appendix 3).

First, the needle is passed right-to-left through both sides of the wound, the needle is released and the forceps (in the left hand) are used to grasp the longer suture end (ie, with the needle still attached). The forceps should grasp the suture at an acute angle such that the suture is an extension of the forceps. The needle driver, in the right hand, is then placed in the center of the wound, between the two suture ends, with the jaws closed and parallel to the wound. The forceps are then used to wrap the long end of the suture inwards towards the center of the knot (clockwise in this example) around the jaws of the needle driver one time. While maintaining the loops around the needle driver, the needle driver’s jaws are opened and used to grasp the tail end of the suture. The tail is then pulled toward the surgeon while the long end (in the forceps) is pulled away from the surgeon.

The directionality of this second suture is essential to creating the slip knot. The short and long ends should now be on opposite sides from where they started. The needle driver is placed “outside” the knot or “outside” the valley, meaning it is placed on the side of the long suture that is not adjacent to the short end. In this example, that would be on the right side of the long suture. The forceps in the left hand then wrap the suture around the needle driver away from the wound (clockwise in this example). The needle driver is then rotated to the right to grab the short end and pull it through. The long and short side of the suture material must be laid down in the same orientation as before the second throw.

The result is that there are two knots thrown in the same direction.

This slip knot can be adjusted to the desired suture tension. If multiple sutures are being placed, the needle can be cut at this time, leaving the tails long enough to place the final throw that ultimately locks the knot.

Multiple sutures can be placed in this manner. Once the desired tension is achieved along the entire wound, a single throw should be placed to lock each knot. This is done in the conventional fashion, with the needle driver placed in the center of the knot, and the long end is wrapped around once in an “inward” direction. In this case, it would be wrapped counterclockwise. The short tail is then pulled through and the knot is locked.

The tension of each suture must be checked prior to tying a knot, because tension changes in one suture will affect the tension of adjacent sutures.

Video 3.

Slip knot.

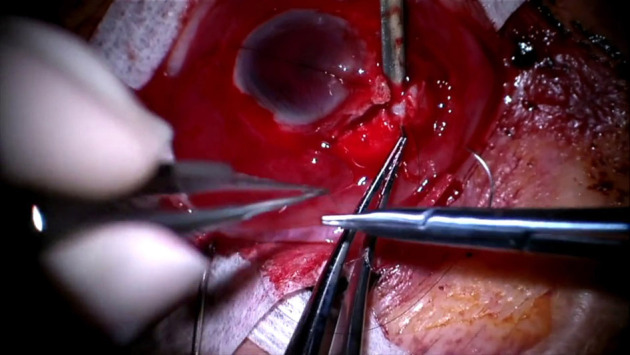

Extraocular Muscle Secure Suture

Proper technique to secure an extraocular muscle to the globe is important for disinsertion and reinsertion of muscles during OGI repair. This suture prevents the surgeon from losing the muscle behind the globe during the case and allows for precise reinsertion to minimize postoperative motility abnormalities. Video 4 details the proper way to secure an extraocular muscle (see also Appendix 4).

The muscle is isolated and marked, a double-armed 6-0 polyglactin 910 suture on a spatulated needle is passed full-thickness through the middle third of the muscle, approximately 1 mm behind the tendon insertion. The suture is pulled, allowing for equal length tails, and a 3-1-1 surgeon’s knot is tied. When cinching this suture, two needle drivers are used to hold the suture tails close to the knot and pull evenly and parallel to the ground to lay the knot flat.

One of the needles is loaded and passed partial thickness through the muscle belly, starting just posterior the central knot and exiting at the lateral muscle edge. If the suture is appropriately weaved partial thickness, the needle will remain stationary in the tissue without tilting after it is released from the needle driver. Then, starting from the muscle edge where the suture just exited, a full-thickness locking suture is passed from posterior to anterior through approximately one-fourth to one-third of the muscle width. Care is taken to not accidentally cut the previously placed sutures with the spatulated needle. To lock the suture, the needle is passed through the resulting loop before tightening. The knot is then rotated posteriorly by gently pulling on the anterior exiting portion of the suture.

The same step is repeated on the other side of the muscle using the second arm of the suture.

The muscle is now secure to be disinserted. Care is taken to not cut suture material when disinserting the muscle from the globe. The needles should not be cut off as they will be used to reinsert the muscle at the desired origin once globe repair is complete.11

Video 4.

Securing an extraocular muscle.

Locking Knot

A locking knot is a temporary secure hold in the suture material to maintain tension on a wound during repair. This is usually done after the first throw, which allows the surgeon to maintain the tension required to hold the wound edges together while reloading the needle. The tension can then be maintained while making the remaining throws to complete the knot. This knot requires that the first throw has multiple loops (typically two or three). This is most commonly used with corneal nylon sutures.

The first throw of the knot uses two or more loops (see surgeon’s knot, above).

After tightening the suture, both ends of the suture are pulled evenly toward one side of the wound. Typically, one hand is kept stationary while the other moves the suture end to the first hand’s side, pulling them together. This “locks” the first throw under tension. Care is taken to ensure even pulling; otherwise, the knot may become loose.

The second throw is carefully done so as to not disrupt the tension on the locked knot. Note, a third throw is still needed to stabilize and secure the knot.8

(CMM, MCW)

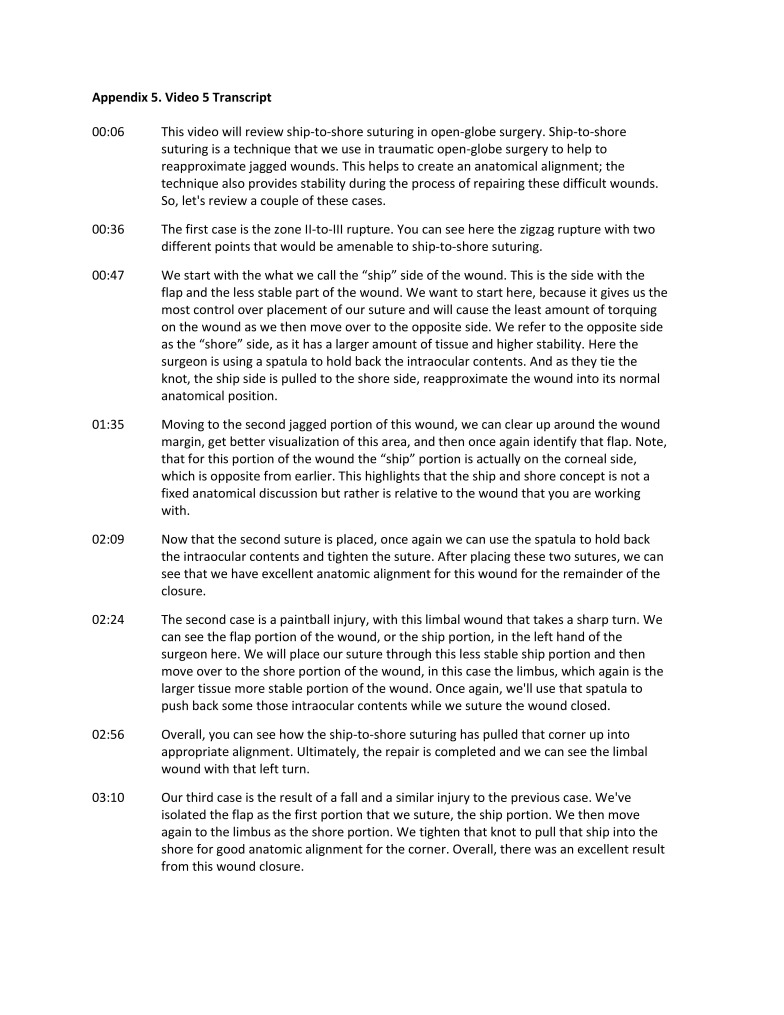

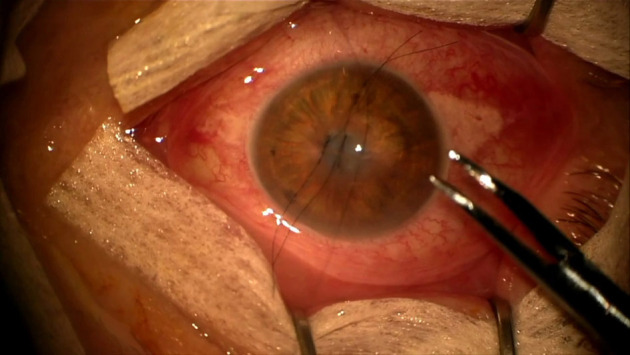

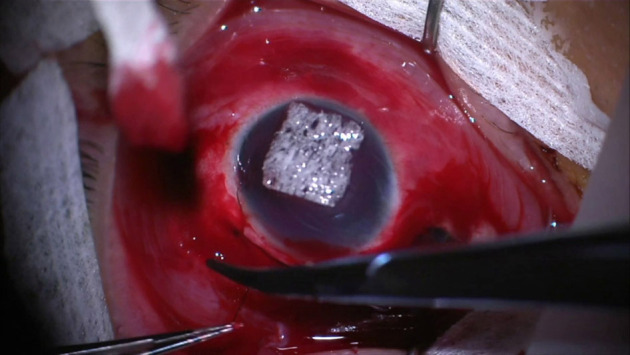

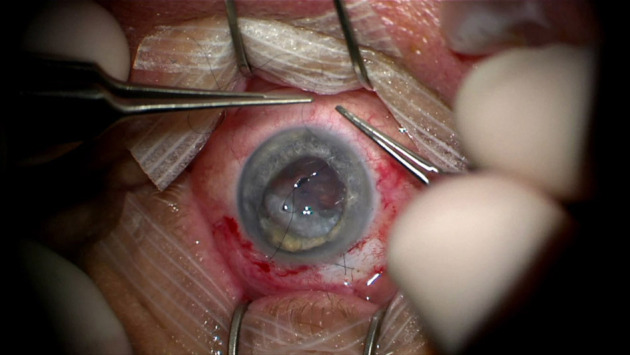

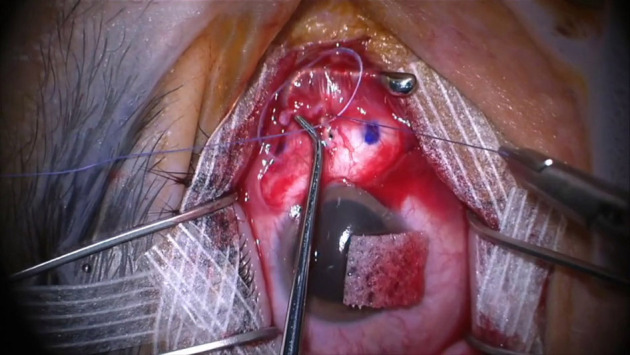

Ship-to-Shore Suturing

Although ship-to-shore suturing is a concept commonly discussed in penetrating keratoplasty, moving from the graft to the host tissue, this technique is highly relevant to OGI. Specifically, ship-to-shore suturing is an approach in trauma surgery to repair jagged wounds often with small flaps and wounds with sharp, angled edges.

Jagged wounds present two major challenges: alignment and wound stability. Ship-to-shore suturing assists with both. The concept is to place a suture at the location of a turn or corner in the wound, moving from the side with a more acute angle (ie, the smaller side), like a mobile flap, to the side with more tissue.8 When tightened, this pulls the tissue together, as a ship pulled to shore. By moving from the less stable flap (“ship” side) of the wound to the more robust (“shore”) side the surgeon has more control over the needle and suture placement. Furthermore, by joining the jagged corners of the zig-zag wound, this aligns anatomical landmarks and eases repair of the remainder of the wound. For this reason, ship-to-shore suturing should be performed early in jagged wound repair. Notably, unlike in penetrating keratoplasty, where the anatomic relationship of the “ship” and “shore” are constant, in open globe repair, the “ship” side of the wound can change, even within a single wound. Every corner of a jagged wound should be treated independently, assessing which side has the acute angle or flap as the “ship” and which side has more stable tissue as the “shore” side. Video 5 demonstrates proper ship-to-shore suturing (see also Appendix 5).

Wound edges should be explored and identified. Turns within a jagged wound must be located and the acute flap (“ship”) side as well as the corresponding angle in the more robust (“shore”) side identified.

Start with toothed forceps in the left hand and needle driver with a nylon suture (size dependent on location of wound) on a spatulated needle in the right hand. With the toothed forceps, the edge of the “ship” edge of the wound is grasped. A partial-thickness pass through the “ship” side is performed using the needle driver, exiting at the wound margin.

Next, the “shore” edge of the wound is grasped, and another partial-thickness pass at equal depth through the “shore” side of the wound is performed using the needle driver.

If the sclera is being repaired, a surgeon’s knot using a locking technique is tied in a 3-1-1 fashion. If the cornea is being repaired, a slip knot can be used. If intraocular contents are extruding, a spatula can be helpful in repositioning the uvea so contents do not get caught in the wound closure.

Video 5.

Ship-to-shore suturing.

(MCW, CMM)

Key Learning Points

Post-traumatic endophthalmitis occurs in about 10% of cases and can be lowered to 0.9% in the setting of systematic institution of antibiotic therapy.

At our institution, intravenous vancomycin in tandem with a third-generation cephalosporin is used for a total of 48 hours to provide coverage against a wide spectrum of possible organisms.

Postoperatively, topical fluoroquinolones are used for 1 week.

For sustained wound support, a nonabsorbable suture (eg, nylon) should be used.

Select suture size based on wound location: corneal repair with 10-0 nylon, limbal repair with 9-0 nylon, and scleral repair with 8-0 nylon.

Spatulated needles are helpful for partial-thickness passes through cornea, sclera, or muscle, whereas reverse cutting needles are helpful for traction sutures.

Surgeon’s knots are particularly useful in limbal, scleral, and conjunctival closure because they maintain tension between the first and second throws.

Slip knots allow the surgeon to adjust the tension prior to completing the knot. The knot is also less bulky, which is useful in corneal wounds.

Extraocular muscle suturing (securement and disinsertion) may be necessary to expose hidden posterior scleral wounds.

Locking knots are useful for maintaining tension during wound repair temporally.

Ship-to-shore suturing improves anatomic alignment and stability in jagged wounds and should be an early step in OGI repair.

References

- 1.Zhang Y, Zhang MN, Jiang CH, Yao Y, Zhang K. Endophthalmitis following open globe injury. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:111–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.164913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang JM, Pansick AD, Blomquist PH. Use of intravenous vancomycin and cefepime in preventing endophthalmitis after open globe injury. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2016;32:437–41. doi: 10.1089/jop.2016.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long C, Liu B, Xu C, Jing Y, Yuan Z, Lin X. Causative organisms of post-traumatic endophthalmitis: a 20-year retrospective study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014;14:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-14-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed Y, Schimel AM, Pathengay A, Colyer MH, Flynn HW., Jr Endophthalmitis following open-globe injuries. Eye (Lond) 2012;26:212–17. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andreoli CM, Andreoli MT, Kloek CE, Ahuero AE, Vavvas D, Durand ML. Low rate of endophthalmitis in a large series of open globe injuries. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:601–8.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andreoli C, Teiger MG, Kloek C, Lorch AC. Antibiotic prophylaxis for open globe injury: expert opinion controversies in open globe injury management. In: Grob S, Kloek C, editors. Management of Open Globe Injuries. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. pp. 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabatabaei SA, Soleimani M, Behrooz MJ, Sheibani K. Systemic oral antibiotics as a prophylactic measure to prevent endophthalmitis in patients with open globe injuries in comparison with intravenous antibiotics. Retina. 2016;36:360–5. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang JL, Tiwari T, Moro P, et al. Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1–44. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6702a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iyer MN, Kranias G, Daun ME. Post-traumatic endophthalmitis involving Clostridium tetani and Bacillus spp. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:116–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00948-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Libre PE, Mathews S. Endophthalmitis prophylaxis by intracameral antibiotics: in vitro model comparing vancomycin, cefuroxime, and moxifloxacin. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2017;43:833–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2017.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J, Cater KD. Basic Principles of Ophthalmology. 3rd ed. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2015. Suture Materials and Needles; pp. 111–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tannen BL, Hersh PS, Sohn EH. Surgical repair: ocular injuries Basic Techniques of Ophthalmic Surgery. 2nd ed. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2015. pp. 555–67. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan P. The Open Globe—Surgical Techniques for the Closure of Ocular Wounds. Eyelearning Ltd; 2013. Surgical principles; pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong GY, Henderson RH, Sandhu SS, Essex RW, Allen PJ, Campbell WG. Wound-related complications and clinical outcomes following open globe injury repair. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;43:508–13. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wladis EJ, Langer PD. Basic Principles of Ophthalmology. 3rd ed. American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2015. Suturing and knot tying; pp. 177–86. [Google Scholar]