Abstract

Aims and Objectives

: The aim of our study was to present an experience of elective tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients at our institute.

Materials and methods

The present prospective study was conducted, after approval by Institutional Ethics Committee, in the Department of ENT, SMGS Hospital, GMC Jammu from May 2020 to March 2021 over 60 patients having need for prolonged mechanical ventilation and having tested positive for COVID-19 with nasopharyngeal swab on rtPCR assay testing. Detailed information regarding following aspects was gathered :Age, Gender, Comorbidities (Diabetes, Cardiovascular disease, Pulmonary disease, Malignancy), time of endotracheal intubation to tracheostomy, time to wean sedation after tracheostomy, time to wean mechanical ventilation after tracheostomy, surgical complications, mortality, any health care worker in operating team getting infected by SARS-CoV-2. All 60 patients underwent Elective Open Tracheostomy Bed-side in the ICU section of our institute.

Results

The mean age of presentation was 55.9 ± 2.34 years, with male preponderance. The most common indication for tracheostomy was ARDS (Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome) (56.6%). Out of 60 patients, co-morbidities were present in 44 patients (73.3%). The mean time between endotracheal intubation and tracheostomy was 12.2 ± 4.9 days. The mean time to wean mechanical ventilation after tracheostomy was 10.4 ± 2.31 days. The mean time to wean sedation was 2.2 ± 0.83 days. There were no deaths during the procedure. Out of 60 patients, 5 patients (8.3%) died due to complications of COVID-19.

Conclusion

Our study provides important clinical data (such as timing of tracheostomy, pre-operative evaluation of patients, recommendations during procedure, outcomes of tracheostomy and postoperative care) on this threatening issue of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients and might be of immense help to various Otorhinolaryngologists who are dealing with the same situation.

Keywords: COVID-19, Tracheostomy, Ventilation, ARDS

Introduction

World Health Organization declared Corona virus 2019 disease (COVID-19) as a pandemic due to increasing number of cases across globe, resulting in rise of emergency hospital visits, hospitalisations and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admissions [6]. COVID-19 is caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus, and is found abundantly in the upper aerodigestive tract mucosa. The mode of transmission is usually via close contact, droplets or aerosols from aerosol generating procedures like cardiopulmonary resuscitation, tracheal intubation, bronchoscopy and tracheostomy [22].

Respiratory decompensation in the form of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) with need for mechanical ventilation is the hallmark of severe novel corona virus 2019 (COVID-19) [3]. Around 3–15% of all COVID-19 hospitalisations require mechanical ventilation [18]. At present, it is advocated to perform early invasive intubation and avoid non-invasive positive pressure ventilation measures like BiPAP, High flow nasal cannula and bag masking, as they carry significantly increased risk of aerosol generation [7].

Prolonged mechanical ventilation is associated with many side-effects such as ventilator induced lung injury, ventilator associated pneumonia and disuse myopathies [19]. Tracheostomy is a common surgical procedure done in ICU to facilitate weaning from ventilator support, to decrease use of sedation, to ease airway and pulmonary toilet, to improve patient comfort and daily living activity, to reduce airway resistance, to decrease laryngeal injury from endotracheal intubation, to decrease dead space and to prevent long term complications like tracheal stenosis [5].

Tracheostomy is one of the most high-risk surgical procedures in COVID-19 patients, as signalled by experiences from SARS outbreak in 2002–2004 and early reports from USA and Italy. There are two types of tracheostomy techniques that can be used- Percutaneous dilatational and Open conventional. An open technique is usually recommended over percutaneous technique for minimisation of aerosol generation and aerosol exposure. Unfavourable neck anatomy- short neck, enlarged thyroid, neck cicatricial contracture, also make percutaneous dilatational technique unsuitable [2].

World Health Organisation (WHO), Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Centre for Health Protection (CHP) recommend full barrier protection and negative pressure operating room facility when performing tracheostomy for patients COVID-19 infection, in order to avoid disease transmission to health care workers. Such Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) includes gloves, goggles, face shield, gowns, N95 face masks/ Powered air purifying respirator hoods, and aprons [20].

However, there is very limited literature regarding the timing of tracheostomy in COVID-19 ventilated patients and any other specific considerations for tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients. With our study, we aim to bridge this gap in knowledge.

The aim of our study was to present an experience of elective tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients at our institute.

Materials and methods

The present prospective study was conducted, after approval by Institutional Ethics Committee, in the Department of ENT, SMGS Hospital, GMC Jammu from May 2020 to March 2021 over 60 patients.

Inclusion criteria: Patients having need for prolonged mechanical ventilation and having tested positive for COVID-19 with nasopharyngeal swab on rtPCR assay testing.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with grave hypoxemia, severe abnormal coagulopathy, multiple organ failure.

Detailed information regarding following aspects was gathered:

Age, Gender, Comorbidities (Diabetes, Cardiovascular disease, Pulmonary disease, Malignancy).

Time of endotracheal intubation to tracheostomy.

Time to wean sedation after tracheostomy.

Time to wean mechanical ventilation after tracheostomy.

Surgical complications.

Mortality.

Any health care worker in operating team getting infected by SARS-CoV-2.

All 60 patients underwent Elective Open Tracheostomy Bed-side in the negative pressure ICU section of our institute. All the staff (including One Consultant of our department, One Senior Resident of our department, One Junior Resident of our department, One Consultant of department of Anaesthesia, One Senior Resident of Department of Anaesthesia, One ENT OT nurse, One ICU nurse) involved in the procedure used Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) including gloves, goggles, face shield, gowns, surgical cap, shoe cover and N95 face masks.

In all 60 patients, vertical skin incision from lower border of cricoid cartilage to just above the sternal notch was given. Subcutaneous fat, soft tissues were dissected. Strap muscles were retracted. Thyroid isthmus was retracted superiorly. Once trachea was exposed, the Anaesthetist was informed to confirm paralysis, pre-oxygenate with PEEP and then stop ventilation and turn off flows. ETT was clamped, cuff deflated and advanced beyond proposed tracheal window. Then, cuff was hyperinflated and oxygenation re-established with PEEP. When adequately oxygenated, anaesthetist was advised to cease ventilation prior to opening trachea. Tracheal window was created, ETT cuff was deflated and drawn back proximally. Cuffed, non-fenestrated tracheostomy tube was inserted and tracheostomy tube cuff inflated immediately, with prompt circuit attachment and ventilation was resumed. Once position of tube was confirmed with end tidal CO2 (avoiding contamination of stethoscope by auscultation), doffing of PPE was done in designated room appropriately.

PPE was worn by health personnel during postoperative care of patients as well. First tracheostomy tube change was done at 10th post-operative day.

Results

The mean age of presentation was 55.9 ± 2.34 years, with maximum number of patients (50%) in the group of 51–65 years (Table1). Out of 60 patients, 49 were males and 11 were females, male to female ratio being 4.4:1.

Table 1.

Age Distribution

| Age Group (in years) | Number of Patients (n = 60) |

|---|---|

| Less than 20 | 0 (0%) |

| 20–35 | 07 (11.6%) |

| 36–50 | 11 (18.3%) |

| 51–65 | 30 (50%) |

| 66 and above | 12 (20%) |

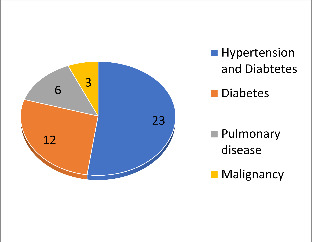

The indication for tracheostomy was ARDS in 34 patients (56.6%), failure to wean in 25(41.6%) and retained secretion management in 1 patient (1.6%). Out of 60 patients, co-morbidities were present in 44 patients (73.3%). Out of 44 patients (Figure 1), 23 patients (52.2%) had hypertension and diabetes mellitus both, 12 patients had diabetes mellitus (20%), 6 patients had pulmonary disease (10%) and 3 patients gave past history of malignancy (5%).

Fig. 1.

CO-MORBIDITY DISTRIBUTION

The mean time between endotracheal intubation and tracheostomy was 12.2 ± 4.9 days. The mean time to wean mechanical ventilation after tracheostomy (Table 2) was 10.4 ± 2.31 days. The mean time to wean sedation was 2.2 ± 0.83 days.

Table 2.

Outcome After Tracheostomy

| OUTCOME AFTER TRACHEOSTOMY | TIME (IN DAYS) |

|---|---|

| Mean time to wean sedation | 2.2 ± 0.83 |

| Mean time to wean mechanical ventilation | 10.4 ± 2.31 |

| Mean time to death | 14.5 ± 3.7 |

Out of 60 patients, 3 patients developed surgical complications (5%) − 2 patients (3.3%) developed subcutaneous emphysema and 1 patient (1.6%) developed wound infection. There were no deaths during the procedure.

Out of 60 patients, 5 patients (8.3%) died due to complications of COVID-19, the mean duration between tracheostomy and death being 14.5 ± 3.7 days.

No health care team member contracted the COVID-19 viral infection post-procedure.

Discussion

Endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation are the most common and indispensable life-saving treatment for severe COVID-19 patients. Prolonged endotracheal intubation places the ENT specialist in midst of an increasing request for tracheostomy.

Tracheostomy is an aerosol generating procedure, with the risk of health care workers performing the procedure contracting the infection being about four-times more. The risk of contracting the infection is not only during the procedure, but also during post-tracheostomy care of patients. Hence, full personal protective equipment should be used by all health care workers performing the procedure as well as during post-procedure care of these patients. [21]

The mean age of presentation in our study was 55.9 ± 2.34 years, with maximum number of patients (50%) in the group of 51–65 years. This finding was consistent with studies conducted by Chao TN et al. (2020) [2], Yu Chow VL et al. (2020) [20] and Yeung E et al. (2020) [19]. However, Zhang et al. (2020) [21] in their study showed more older mean age of presentation of 69.4 years. The reason for majority of patients in the age group could be due to the fact that older patients with COVID-19 infection are associated with adverse clinical outcomes, requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation.

Out of 60 patients, 49 were males and 11 were females, male to female ratio being 4.4:1. This finding was comparable to study conducted by Volo T et al. (2021) [16]. The male preponderance could be due to the fact that COVID-19 disease exhibits differences in morbidity and mortality between sexes, with male gender identified as a risk factor for death and ICU admission. Females have higher number of CD4 + T cells, more robust CD8 + T cell cytotoxic activity and increased B cell production of immunoglobulins as compared to males.[11].

In our study, the indication for tracheostomy was Acute Respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in 34 patients (56.6%), failure to wean in 25(41.6%) and retained secretion management in 1 patient (1.6%). This finding was consistent with Chao TN et al. (2020)[3], who in their study showed ARDS as the most common indication, followed by Failure to wean, airway oedema, sedation and secretion management. However, it is extremely necessary to form a multi-disciplinary team of ENT specialists and Anaesthesiologists for discussion of each and every case before proceeding with tracheostomy.

Out of 60 patients, co-morbidities were present in 44 patients (73.3%). Out of 44 patients, 23 patients (52.2%) had hypertension and diabetes mellitus both, 12 patients had diabetes mellitus (20%), 6 patients had pulmonary disease (10%) and 3 patients gave past history of malignancy (5%). In our study, outcome of patient undergoing tracheostomy and their postoperative course were not affected by associated comorbidity. This was consistent with study conducted by Chiesa-Estomba CM et al. (2020) [4]. However, COVID-19 patients with associated comorbidities have a poorer prognosis and thus, appropriate decision should be taken before proceeding with a high aerosol generating procedure like tracheostomy.

In our study, all tracheostomies were done bed-side in order to reduce additional viral exposure in route to Operation theatre and also, minimise the procedural time. In our study, all tracheostomies were done by open conventional technique, as percutaneous technique involves increased exposure to viral secretions and aerosolised particles due to- additional airway manipulation with repeated dilatations firstly and use of bronchoscope evaluation, secondly. These findings were comparable to study conducted by Mecham et al. (2020) [10], who also favoured doing bedside open conventional tracheostomies in COVID-19 patients. In all 60 patients, vertical skin incision was used to minimise risk of vascular injury and gain rapid access to trachea.

In our study, the mean time between endotracheal intubation and tracheostomy was 12.2 ± 4.9 days. This finding was consistent with European guidelines (excluding British guidelines) [14] who suggest tracheostomy within 14 days of endotracheal intubation. However, British, North American and South African guidelines [17] suggest tracheostomy to be done after 14 days or after a negative COVID-19 swab test. Early Tracheostomy within 7 days of ventilation is not considered appropriate because in the early phase, aggressive treatments and intensive care is required for the patients and tracheostomy cannot lead to any improvement in hypoxia, multi-organ dysfunction and virus clearance. Also, available evidence suggests that viral shedding is maximum in the first week of infection and that viability of virus decreases after 8 days, although positive RNA on swab may persist for much longer time [9].

The mean time to wean mechanical ventilation after tracheostomy was 10.4 ± 2.31 days. This finding was comparable to studies conducted by Yeung E et al. (2020) [19] and Angel L et al. (2020) [1], both studies showing a median time duration of 11 days to wean mechanical ventilation. The mean time to wean sedation was 2.2 ± 0.83 days, this finding being comparable to study conducted by Yeung E et al. (2020) [19], who showed a median time duration of 0.5 days.

Out of 60 patients, 3 patients developed surgical complications (5%) − 2 patients (3.3%) developed subcutaneous emphysema and 1 patient (1.6%) developed wound infection. There were no deaths during the procedure. Out of 60 patients, 5 patients (8.3%) died due to complications of COVID-19, the mean duration between tracheostomy and death being 14.5 ± 3.7 days. The mortality rate of our study was comparable to studies conducted by Angel L et al. (2020) [1] and Takhar A et al. (2020) [15]. However, Ferri E et al. (2020) [5] and Riestra-Ayora J et al. (2020) [13] reported mortality rate of 25% and 41% respectively. The reason for mortality after tracheostomy can be due to the fact that survival in COVID-19 patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation is very low (< 20%) and tracheostomy doesn’t impact on natural history of these patients [10].

No health care team member contracted the COVID-19 viral infection post-procedure. This finding was consistent with studies conducted by Zhang et al. (2020) [21], Mecham et al. (2020) [10] and Chao TN et al. (2020) [2], suggesting it is safe and effective to perform tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients on prolonged endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, if proper PPE is used by all concerned health personnels.

Postoperative care of tracheostomised patients is equally important. In our study, Full PPE was worn by health personnel in postoperative period as well, for droplet/aerosol precautions and first tracheostomy tube change was done after 7 days. This was consistent with study conducted by Jacob T et al. (2020) [8], who in their study conducted tracheostomy tube change after an interval of 7–10 days. However, Spanish guidelines [12] recommend changing tracheostomy tube after 14–21 days. The general recommendation for postoperative care is that if the patient is on mechanical ventilation, viral filter should be used with ventilator circuit and closed in-line suctions should be used. If patient is off-mechanical ventilation, unnecessary suctioning should be avoided and tracheostomy tube change should be deferred till patient is no longer infectious.

Conclusion.

Due to constant exposure to droplets/aerosols infected with SARS-CoV-2, Tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients is a very high-risk aerosol generating procedure. Hence, comprehensive evaluation of all patients requiring tracheostomy, and adequate PPE for health care workers is necessary before proceeding with the procedure.

Our study provides important clinical data (such as timing of tracheostomy, pre-operative evaluation of patients, recommendations during procedure, outcomes of tracheostomy and postoperative care) on this threatening issue of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients and might be of immense help to various Otorhinolaryngologists who are dealing with the same situation.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Nil.

The study was approved by Institutional Ethics Committee, GMC Jammu to be conducted on 60 human patients (no animals were used in this research).

Written and Informed consent was taken from all the patients in the language that patients/attendants understood.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Angel L, Kon ZN, Chang SH et al. Novel percutaneous tracheostomy for critically ill patients with COVID-19. Ann Thorac Surg 2020;1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chao TN, Braslow BM, Martin ND et al. Tracheotomy in ventilated patients with COVID-19- guidelines from the COVID-19 Tracheotomy task force, a working group of the airway safety committee of the University of Pennsylvania Health System. Annals of Surgery 2020

- Chao TN, Harbison SP, Braslow BM, et al. Outcomes after tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients. Ann Surg. 2020;272:181–186. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa-Estomba CM, Lechien JR, Calvo-Henriquez C, et al. Systematic review of international guidelines for tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients. Oral Oncol. 2020;108:104844. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri E, Nata FB, Perduzzi B, et al. Indications and timing for tracheostomy in patients with SARS-CoV2- related. Eur Arch Oto Rhino Laryngol. 2020;277:2403–2404. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06068-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M. Critical care utilisation for COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: early experience and forecast during an emergency response. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1545. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui DS. Severe acute respiratory syndrome(SARS): lessons learnt in Hong Kong. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5(2):122–126. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.06.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Walker A, Mantelakis A, et al. A framework for open tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients. Clin Otolaryngol. 2020;45:649–651. doi: 10.1111/coa.13549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattioli F, Fermi M, Ghirelli M, et al. Tracheostomy in the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Arch Oto Rhino Laryngol. 2020;277:2133–2135. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05982-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecham JC, Thomas OJ, Pirgousis P et al(2020) Utility of tracheostomy in patients with COVID-19 and other special considerations.Laryngoscope:28734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Peckham H, de Gruijter NM, Raine C, et al. Male sex identified by global COVID-19 meta-analysis as a risk factor for death and ITU admission. Nat Commun. 2020;11:6317. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19741-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recomendaciones de la Sociedad Espanola de Otorrinolaringologia y Cirugia de Cabeza y Cuello (SEORL-CCC) para la realizacion de traqueotomias en pacientes infectados por la COVID-19 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Riestra-Ayora J, Yanes-Diaz J, Penuelas O et al. Safety and prognosis in percutaneous vs surgical tracheostomy in 27 patients with COVID-19. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;1177 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schultz P, Morvan JB, Fakhry N, et al. French consensus regarding precautions during tracheostomy and post-tracheostomy care in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2020;137(3):167–169. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takhar A, Walker A, Tricklebank S, et al. Recommendation of a practical guideline for safe tracheostomy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277:2173–2184. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05993-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volo T, Stritoni P, Battel I, et al. Elective tracheostomy during COVID-19 outbreak: to whom, when, how? Early experience from Venice, Italy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278:781–789. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06190-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter S, Rocke J, Heward E. Guidance for surgical tracheostomy and tracheostomy tube change during the COVID-19 pandemic. Head and Neck Surgery: The South African Society of Otorhinolaryngology; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM(2019) Characteristics of and important lessons from coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72,314 cases from chinese centre for Disease Control and Prevention.JAMA;2648 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yeung E, Hopkins P, Auzinger G, et al. Challenges of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients in a tertiary centre in inner city London. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;4518:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2020.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Chow VL, Wai Chan JY, Yee Ho VW, et al. Tracheostomy during COVID-19 pandemic- Novel Approach. Head Neck. 2020;42:1367–1373. doi: 10.1002/hed.26234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Huang Q, Niu X et al(2020) Safe and effective management of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients.Head & Neck;1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]