Abstract

The genome of Helicobacter pylori contains numerous simple nucleotide repeats that have been proposed to have regulatory functions and to compensate for the conspicuous dearth of master regulatory pathways in this highly host-adapted bacterium. H. pylori strain 26695, whose genomic sequence was determined by The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR), contains a repeat of nine cytidines in the fliP flagellar basal body gene that splits the open reading frame in two parts. In this work, we demonstrate that the 26695C9 strain with a split fliP gene as sequenced by TIGR was nonflagellated and nonmotile. In contrast, earlier isolates of strain 26695 selected by positive motility testing as well as pig-passaged derivatives of 26695 were all flagellated and highly motile. All of these motile strains had a C8 repeat and consequently a contiguous fliP reading frame. By screening approximately 50,000 colonies of 26695C9 for motility in soft agar, a motile revertant with a C8 repeat could be isolated, proving that the described switch is reversible. The fliP genes of 20 motile clinical H. pylori isolates from different geographic regions possessed intact fliP genes with repeats of eight cytidines or the sequence CCCCACCC in its place. Isogenic fliP mutants of a motile, C8 repeat isolate of strain 26695 were constructed by allelic exchange mutagenesis and found to be defective in flagellum biogenesis. Mutants produced only small amounts of flagellins, while the transcription of flagellin genes appeared unchanged. These results strongly suggest a unique mechanism regulating motility in H. pylori which relies on slipped-strand mispairing-mediated mutagenesis of fliP.

Helicobacter pylori, the causative agent of gastritis and ulcer disease in humans, relies on its high motility in viscous environments to colonize and persist in the human stomach (14, 18). H. pylori carries a unipolar bundle of sheathed flagella (19). Relatively little is known about the regulation of flagellar biosynthesis in H. pylori (32, 33). The whole genome sequence of H. pylori strain 26695 (determined by The Institute for Genomic Research [TIGR]) has revealed a conspicuous lack of regulatory elements that are present in other eubacterial species (36). H. pylori does not possess a homolog of the flhCD master operon which is at the top of the regulatory hierarchy coupling cell division and motility functions in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Bacillus subtilis, and other eubacteria (23). H. pylori also appears to lack a homolog of the flgM gene that in other eubacteria codes for an antagonist of the flagellar sigma factor, ς28 (15). Except for the gene coding for the major H. pylori flagellin, flaA, most flagellar genes of H. pylori are governed by ς54- or ς70-dependent promoters (28, 33, 34). Taken together, the available data suggest that the regulation of flagellar biogenesis and motility differs considerably between H. pylori and other bacteria.

The complete genome sequences of H. pylori strains 26695 and J99 contain close to 30 genes with simple sequence repeats (dinucleotide repeats or homopolymeric tracts), either within the upstream regulatory regions or within the coding sequences (2, 36). Because of the abundance of such sequence repeats, slipped-strand mispairing has been suggested to be involved in the control of gene expression in H. pylori (31). Simple nucleotide repeats are mutational hot spots because they reduce the fidelity of both DNA replication and transcription. Changes of repeat length due to slipped-strand mispairing (insertion or deletion of repeat units) and consequent disruption of open reading frames by premature stop codons occur at a much higher rate than mutations in other areas of the chromosome. Slipped-strand mispairing plays a regulatory role, on both transcriptional and translational levels, in several other bacteria, mainly for the variation of surface-associated proteins and related structures such as fimbriae, capsules, or lipopolysaccharides (13, 25, 39; for a review, see reference 38). Recently, slipped-strand mispairing within fucosyltransferase genes of H. pylori has been demonstrated to play a role in the variation of lipopolysaccharide O-specific side chains (4, 40). Among the potentially phase-variable genes of H. pylori, there is also one motility-associated gene, fliP, the product of which is involved in the flagellar export apparatus of eubacteria (27, 31).

In H. pylori strain 26695, whose genome has been sequenced completely, fliP contains a repeat of nine cytidines (C9) within its coding region (36). This repeat causes a frameshift and splits the gene in two parts (HP0684 and HP0685). In the second complete genome sequence of an H. pylori strain (J99), fliP is a contiguous open reading frame with a C8 repeat (2).

We therefore wanted to know if the C9 repeat in fliP might in fact be involved in motility regulation in H. pylori and if the motility phenotype of the organism is dependent on expression of a full-length FliP protein. We have studied the fliP locus in different motile and nonmotile variants of strain 26695 and in different clinical isolates of H. pylori. In addition, we constructed and characterized isogenic fliP mutants of different H. pylori strains. The results make a convincing case for slipped-strand mispairing within the fliP locus as a novel regulatory feature of H. pylori motility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

H. pylori strains N6 (11) and 88-3887, a motile pig-passaged variant of H. pylori 26695 (36), and the mouse colonizing strain SS1 (21) were used for the construction of fliP mutants. fliP sequences were determined for various motile and nonmotile variants of 26695, for N6, SS1, the nonmotile strain Tx30a (22), and for 20 clinical isolates from Germany, South Africa, and Singapore (1, 35). Culture conditions for H. pylori strains were as described elsewhere (34).

DNA manipulation, PCR, and nucleotide sequencing.

DNA manipulations were done according to standard protocols (30). H. pylori genomic DNA for sequence determination was prepared with a QiaAmp tissue kit (Qiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany). Plasmid DNA was purified with the Qiagen Midi column plasmid purification kit. DNA restriction fragments or PCR products were purified from agarose gels with a QiaQuick DNA purification kit (Qiagen). Nucleotide sequences were determined by direct sequencing of PCR products generated using the primers OLHPFliP1 (CCTCATTTGCCCTTTAATATGC) and OLHPFliP2 (GGCAGAGAAATCATTACAGG). PCR consisted of 35 cycles as follows: denaturation, 94°C for 1 min; annealing, 50°C for 1 min; and extension, 72°C for 1 min; 75-ng aliquots of PCR products purified using the QiaQuick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) were used in cycle sequencing reactions from both strands with an ABI Prism dye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems), using the same primers and independent PCR products for each strand. Sequences were aligned using Seqlab and Pileup from the Wisconsin Package, version 9.1 (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.). All sequences were reduced to a common length of 480 nucleotides.

Construction of isogenic fliP mutants of H. pylori.

The complete fliP gene from the motile 26695 variant 88-3887 (fliPC8) including additional upstream and downstream sequences (1,622 bp) was amplified by PCR with the primers OLHPFliP3s (TATGGATCCCATAACCTTTAGGGTCAGC) and OLHPFliP4s (TTAGGATCCGACTTTTGGTATTAGCAGC), which both contained BamHI sites, and cloned into vectors pILL570 (20) and pUC18 cut with BamHI to give plasmids pCJ53 and pCJ51, respectively. Subsequently, the cloned fliP gene was disrupted by insertion of a cassette that contains a kanamycin resistance gene (aphA-3 [37]). The cassette was inserted in two different positions. In plasmid pCJ55, a direct derivative of pCJ53, the cassette was introduced into a natural EcoRI restriction site at nucleotide position 360 of the fliP locus in H. pylori KE26695, which is 151 nucleotides downstream of the C8 repeat and 96 nucleotides downstream of the stop codon. To construct a plasmid where the insertion was located exactly at the same position of the premature stop codon in C9 strains, the following strategy was used. Inverse PCR with primers OLHPFliP5s (TTAAGATCTCTATGATACAGGGATTAAGC) and OLHPFliP6s (ATTAGATCTCGAGACTAAAATTTGAGTGG) and plasmid pCJ51 (fliP insert in pUC18) as the template was used to generate a 50-bp deletion in fliP and to introduce a BglII restriction site at this deletion site just 18 nucleotides downstream of the C8 repeat. The deletion (nucleotides 229 to 279 of fliP) includes the stop codon generated by the fliPC9 locus in 26695 (the TIGR strain). The aphA-3 cassette (cut from pILL600 with BamHI) was ligated into this construct, yielding plasmid pCJ57. Since fliP is not part of an operon and the two genes downstream of fliP are transcribed in the opposite direction of fliP, polar effects of these disruptions were extremely unlikely. Nevertheless, in both plasmids pCJ55 and pCJ57, the aphA-3 cassette, which has a strong promoter and no transcription terminator, was inserted in the same transcriptional orientation with respect to fliP, further reducing the possibility of polar effects. Plasmids pCJ55 and pCJ57 were used to generate allelic replacement mutants of H. pylori strains SS1 and N6 and the motile 26695 variant 88-3887 by natural transformation. Natural transformation of H. pylori was performed as described elsewhere (6). After natural transformation, the bacteria were grown on nonselective plates for a period of 24 h and then transferred to plates containing kanamycin (20 mg/liter). Recombinant colonies were selected after 3 to 5 days of growth. The correct genotype of the kanamycin-resistant mutants was verified by PCRs with primers binding to the target gene and primers binding to the aphA-3 cassette as previously described (34) (data not shown).

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Whole-cell lysates of Helicobacter cells were obtained by sonication, while flagellar filament proteins were partially purified by mechanical shearing and ultracentrifugation as described elsewhere (12). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting were performed as described elsewhere (32). The blots were incubated with a mixture of antisera raised against purified recombinant FlaA and FlaB flagellins of H. pylori, each diluted 1:1,500. Bound antibodies were visualized with a peroxidase-coupled goat anti-rabbit antibody (diluted 1:3,000; Jackson Biologicals Laboratory, West Grove, Pa.).

Electron microscopy and motility testing.

Transmission electron microscopy of negatively stained bacteria was performed as described elsewhere (17). Motility testing of H. pylori strains was performed either in wet mounts or in 0.3% motility agar plates as described elsewhere (7, 17). Motility plates were incubated for 5 days.

Preparation of RNA from H. pylori.

RNA from H. pylori was prepared by the RNEasy Midi-Prep procedure (Qiagen) or using a CsCl centrifugation method described by Spohn and Scarlato (33). RNA was prepared from bacteria grown on two blood agar plates for 24 h or from 25 ml of liquid culture grown to an optical density at 600 nm of about 1.0 (mid-log phase, approximately 1010 bacteria). RNA slot blotting was done with a Bio-Dot slot blotting apparatus (Bio-Rad). The amount of specific mRNA was detected by hybridization with digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled DNA probes (flaA, flaB, flgE, and fliP; PCR-generated fragments; probes were generated with a DIG-labeling kit from Boehringer/Roche); 2-μg aliquots of RNA were analyzed on the blots. In all strains, the hybridization signal with a fliP probe was too weak to be evaluated, even when 5 μg of RNA was used. Control hybridizations using the four different probes on an Escherichia coli DH5α RNA gave no detectable background signal. The sequences of the primers used to generate the probes by PCR are available upon request.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequences described in this paper have been submitted to the GenBank database (accession no. AJ404379 to AJ404400).

RESULTS

H. pylori 26695C9 (the TIGR strain) is nonmotile and lacks flagella.

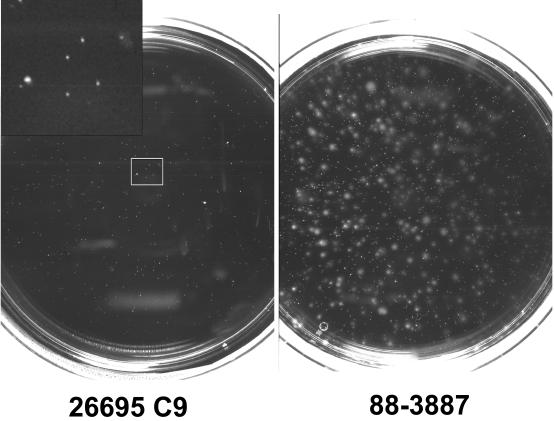

Because the genome sequence of H. pylori 26695C9 does not contain a full-length fliP gene, we analyzed whether this strain carried flagella and was motile. H. pylori 26695C9 was studied by electron microscopy, and no flagella were detected (data not shown). Bacteria were completely nonspreading in motility agar, and no motility was visible by direct microscopy of wet mounts (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Motility tests of H. pylori 26695C9 and the pig-passaged variant, 88-3887. The nonmotile 26695C9 strain shows only pinpoint colonies without spreading, while the majority of 88-3887 colonies have a spreading phenotype. The inset in the upper left corner shows a magnification of the area of the plate marked by the square.

Different fliP genotypes in motile and nonmotile variants of strain 26695.

Previous studies have shown that motility is essential for the ability of H. pylori and other Helicobacter spp. to colonize the gastric mucosa (3, 9, 16). It was therefore surprising that a virulent isolate of H. pylori was nonmotile. H. pylori 26695 was received by one of us in 1986. It was noted that colonies of highly motile and nonmotile bacteria could be identified in soft agar, and both variants were isolated and frozen (8).

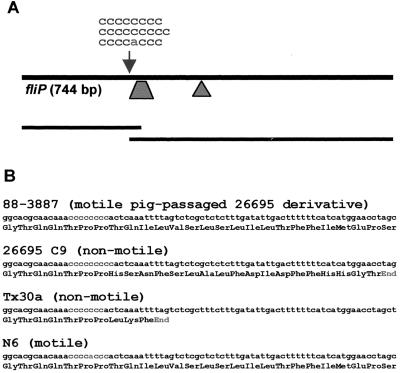

To clarify whether the motility of different 26695 variants depended on the length of the fliP repeat sequence, a 642-bp fragment of fliP that contained the homopolymeric repeat was amplified by PCR and sequenced directly from both strands for 26695C9 as well as several motile and nonmotile variant strains (Table 1). 26695C9 contained a C9 repeat and a premature stop codon in fliP 53 nucleotides downstream of the repeat, as reported by Tomb et al. (36) (Fig. 2). An original motile variant (26C) that had been selected because it formed large spreading colonies in motility agar had eight cytidine residues and a continuous fliP gene, while a nonmotile variant (26B) had nine cytidines (Table 1; Fig. 2). We also analyzed six strains each that had been obtained from initial motile or nonmotile variant strains by repeatedly passaging them in vitro without selection for or against motility (up to 10 passages). No changes in the repeat length were detectable in those passaged strains. Three strains (for example, strain 88-3887) that had been reisolated from piglets that had been experimentally infected with the original (mixed) H. pylori 26695 were fully motile and possessed the fliPC8 genotype.

TABLE 1.

H. pylori strains characterized in this study

| Strain | Origin or description | fliP genotype | Presence of flagella and motility |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26695 variants | |||

| 26695C9 | United Kingdom | C9 | No |

| 88-3887 | 26695, after 3 pig passages | C8 | Yes |

| 26B | Initial nonmotile subclone of 26695 | C9 | No |

| 26BH | Motile revertant of 26B | C8 | Yes |

| 26C | Initial motile subclone of 26695 | C8 | Yes |

| 26695-R1 | Motile revertant of 26695C9 | C8 | Yes |

| Laboratory strains | |||

| Tx30a | United States | C7 | No |

| N6 | France | CCCCACCC | Yes |

| NCTC11637 | Australia | CCCCACCC | Yes |

| NCTC11639 | Australia | C8 | Yes |

| SS1 | Australia | CCCCACCC | Yes |

| Asia | |||

| RE7003 | Singapore | CCCCACCC | Yes |

| RE8029 | Singapore | CCCCACCC | Yes |

| RE8038 | Singapore | CCCCACCC | Yes |

| RE12001 | Singapore | CCCCACCC | Yes |

| RE12004 | Singapore | CCCCACCC | Yes |

| South Africa | |||

| CC1 | Cape Town | CCCCACCC | Yes |

| CC7 | Cape Town | C8 | Yes |

| CC26 | Cape Town | C8 | Yes |

| CC29 | Cape Town | C8 | Yes |

| CC48 | Cape Town | C8 | Yes |

| CC56 | Cape Town | C8 | Yes |

| Germany | |||

| BO242 | Bochum | CCCCACCC | Yes |

| BO255 | Bochum | CCCCACCC | Yes |

| BO261 | Bochum | C8 | Yes |

| BO265 | Bochum | C8 | Yes |

| BO266 | Bochum | CCCCACCC | Yes |

| BO314 | Bochum | CCCCACCC | Yes |

FIG. 2.

(A) Schematic representation of H. pylori fliP and positions of the poly(C) repeat (arrow) and insertion points of the kanamycin resistance cassette in plasmids pCJ55 (triangle; insertion into EcoRI site) and pCJ57 (trapezoid; 50-bp deletion). (B) Nucleotide sequences and deduced translation (in three-letter code) of the region surrounding the poly(C) repeat in a motile and a nonmotile variant of H. pylori 26695, in the nonmotile strain Tx30a, and in H. pylori N6. The repeat is located 315 nucleotides downstream of the fliP start codon.

Isolation of motile revertants of 26695C9.

To demonstrate that the switch from motile (C8) to nonmotile (C9) was reversible, we isolated a motile revertant of 26695C9. The bacteria were diluted in motility agar and poured into petri dishes. Approximately 50,000 colonies were screened before a spreading colony was detected. The spreading colony was isolated and purified through a second round of motility testing. As expected, the motile revertant (26695-R1) had a C8 repeat. A second revertant (26BH) was isolated from strain 26B (C9) by growing a stab preparation of 26B in motility agar for 4 days, swabbing the edge of the streak, and culturing that in broth. That broth produced 117 motile colonies (of 152 total), one of which was colony purified and became 26BH. Like 26695-R1, 26BH had a C8 repeat.

fliP sequence comparison of different H. pylori strains.

To determine if the poly(C) repeat within fliP was conserved between different H. pylori strains, we evaluated fliP sequences (480 nucleotides) from 17 clinical isolates of H. pylori and from four widely used laboratory strains of H. pylori (SS1, NCTC11637, NCTC11639, and Tx30a [Table 1; Fig. 2]). With the exception of strain Tx30a, which, consistent with previous reports (7), was nonmotile and lacked flagella, all strains analyzed were motile and carried flagella. Strain Tx30a possessed a C7 stretch instead of the C8 sequence of the motile wild-type strains. All motile strains had a continuous fliP gene; 13 out of the 22 motile strains had an adenine instead of the fifth cytidine within the repeat (CCCCACCC). All five strains from Asia had the CCCCACCC-type allele, while only one out of six strains from the Cape Coloured population in South Africa had that allele.

Construction and characterization of isogenic fliP mutants.

To prove that the premature stop of FliP translation in the strains with a fliPC9 or fliPC7 sequence was sufficient to cause the loss of motility and flagellation observed in 26695C9 and Tx30a, isogenic fliP mutants of three different motile H. pylori strains (the mouse-colonizing strains SS1 and N6 and the piglet-passaged motile variant 88-3887 of strain 26695) were constructed by disruption of fliP with an aphA-3 cassette at two different positions, both close to the position of the premature stop codon in fliPC9 strains (Fig. 2A). For each of the wild-type strains, two different fliP mutants were constructed by natural transformation with pCJ55 or pCJ57. Prior to transformation, the wild-type strains were again checked for motility and the presence of flagella to ensure that motility had not accidentally been lost by repeated in vitro passage.

The fliP region of all mutant strains obtained by allelic exchange mutagenesis was resequenced to exclude that the repeat length had changed during the mutant selection process. All mutants had retained the C8 repeat and had integrated the aphA-3 cassette into their genome at the predetermined sites. In all mutant strains, independent of the parent strain, the sequenced part of fliP was identical to the 26695 fliP sequence, because during the double-crossover event, the wild-type fliP sequences had been replaced by the 26695 sequences flanking the aphA-3 cassette in the suicide plasmids. Both types of mutants in the different H. pylori strains were characterized for motility and the presence of flagella, and flagellin expression was checked by Western blot analysis. The phenotypes of both types of fliP mutants (pCJ55 and pCJ57) were identical in all strains and indistinguishable from the phenotype of 26695C9. All fliP mutants failed to form flagella as determined by transmission electron microscopy and were nonmotile.

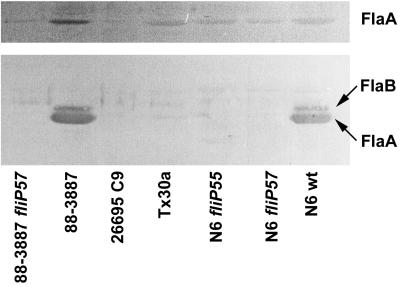

Whole-cell lysates and sheared flagellar material of selected wild-type strains with different fliP genotypes and isogenic fliP mutant strains were analyzed for the presence of flagellins by Western blotting with antisera raised against H. pylori FlaA and FlaB flagellins (Fig. 3). Flagellin synthesis in 26695C9 was very low compared to motile H. pylori wild-type strains, but FlaA was present in whole-cell lysates and, in much lower amounts, in sheared material. To exclude that free flagellin is released into the medium by the nonmotile strains, supernatants of strains grown in liquid culture were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid and analyzed; they did not contain significant amounts of flagellin (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of flagellin expression in H. pylori strains with different fliP genotypes. (Top) Whole-cell lysates; (bottom) partially purified flagella. Material prepared from equal numbers of bacteria was loaded in each lane of the gel. Blots were developed with antisera raised against recombinant H. pylori flagellins. wt, wild type.

Transcriptional analyses of flagella-associated genes in nonmotile H. pylori fliP mutant strains and in motile wild-type strains.

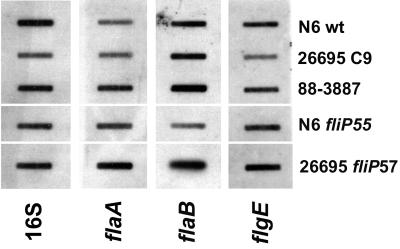

Transcription of the flaA and flaB flagellin genes and the hook gene, flgE, was measured by RNA slot blot hybridization in H. pylori 26695C9, the motile variant of 26695 (88-3887; fliPC8), an isogenic fliP mutant of 88-3887, and the N6 wild-type strain. In all strains with an interrupted fliP gene, flaA-, flaB-, and flgE-specific mRNAs were present in about the same amounts as in the motile wild-type strains (Fig. 4). These data ruled out the possibility that the observed profound reduction in flagellin in these strains was due to a downregulation of flagellin gene transcription.

FIG. 4.

Slot blot hybridization of RNA isolated from H. pylori strains with different fliP genotypes with DNA probes specific for 16S rRNA (16S) and flaA-, flaB-, or flgE-specific mRNA. Each slot contained 2 μg of total RNA. wt, wild type.

DISCUSSION

fliP genotypes and motility in H. pylori 26695.

The data presented here show that H. pylori can use slipped-strand mispairing-mediated frameshifting in fliP to switch the formation of flagella and hence motility off and on. fliP encodes a component of the flagellar basal body and was not previously known to be involved in flagellar regulation of any bacterial species (24). fliP can be reversibly inactivated by addition or deletion of a single cytidine which results in a frameshift and introduces an early stop codon. The consequence of fliP inactivation is a shutdown of flagellar assembly. The observed reduction in the expression of flagellins was not due to transcriptional regulation, because mRNA for major structural flagellar components was present in unchanged amounts in fliP knockout mutants and repeat length variants.

It has been known for a long time that H. pylori loses its motility after prolonged in vitro passage, but the mechanisms responsible for this loss of motility were not known. The H. pylori genome contains relatively few regulatory genes. A striking example is the absence of master regulatory genes (flhCD and flgM) from the flagellar regulatory cascade that have central roles in other bacterial species. In agreement with this, a lack of feedback mechanisms coupling flagellar assembly to the expression of late flagellar genes has been observed in H. pylori hook (flgE) and flagellin (flaA and flaB) mutants (28, 34). The switching mechanism described here may compensate, at least in part, for the lack of other regulatory elements.

The fliP-based switching mechanism appears to be relatively specific to H. pylori. A manual search of all available fliP sequences in GenBank for homopolymeric tracts or dinucleotide repeats was performed. No homopolymeric tract was present in the fliP gene of Campylobacter jejuni, whose flagellar system is otherwise quite similar to that of H. pylori, or the fliP genes of any other bacterium with the notable exception of Borrelia burgdorferi, where the potentially frameshiftable sequence T9AT6 is located only few nucleotides downstream of the start codon of fliP (GenBank accession no. L75945). It is tempting to speculate that B. burgdorferi, which, like H. pylori, has very few regulatory genes (e.g., only two two-component signal transduction systems) may employ a similar strategy to switch off motility. Indeed, frameshifts in a motility-associated gene have only recently been shown for the first time to be involved in switching of flagellar biogenesis. Park et al. (29) showed that a nonmotile variant of Campylobacter coli UA585 had an interrupted flhA gene, which was due to a length change in a short homopolymeric T repeat. Motile revertants had corrected the repeat length and restored an intact flhA gene. No repeat was present in C. jejuni flhA or in H. pylori flhA (formerly flbA) (34).

fliP mutants.

The hypothesis that the nonmotile phenotypes of H. pylori strains 26695 and Tx30a are caused by the frameshifts in fliP was verified by the construction of isogenic fliP knockout mutants of different motile H. pylori strains. Polar effects of the cassette mutagenesis were extremely unlikely, because fliP in H. pylori (unlike in salmonellae) is not part of an operon. The two genes located downstream of fliP are transcribed in the opposite direction. The phenotype of these mutants was indistinguishable from that of 26695C9.

FliP and flagellar assembly.

In salmonellae, FliP is an early flagellar protein on the second hierarchical level of flagellar biogenesis and under the direct control of the flhCD master operon, which is not present in H. pylori (27). FliP, of which in salmonellae there are about five subunits per flagellum, is considered a component of the flagellar type III export system in the flagellar basal body (10). It is highly likely that fliP mutants are no longer able to export flagellar components (27). In the H. pylori nonmotile wild-type strains as well as the isogenic fliP mutants, small amounts of flagellin were detected in the cytoplasmic fraction of the bacteria, showing that translation still takes place. In contrast to what was described for H. pylori flgE mutants (28), there was no accumulation of intracellular flagellin, suggesting that flagellin stability is reduced in fliP mutants.

Frequency of motility switching.

The switching frequencies of the motility phenotype had previously been determined to be 1.6 × 10−4 for the motile-to-nonmotile switch and less than 10−7 for the inverse event (8). We could not measure the rate of the fliP off switch, because when motile strains of H. pylori are tested in soft agar, many colonies appear nonmotile (such as the pinpoint colonies in the left panel of Fig. 1). Most of these either still express flagellins or, if they do not, still have a C8 genotype (data not shown). Thus, frameshifting in fliP does not seem to be the only mechanism responsible for loss of motility in H. pylori. With more than 50 genes involved in motility and flagellar biosynthesis, there are many different possible events that could cause a nonmotile phenotype. We succeeded in detecting the fliP on switch. Screening of a fliPC9 strain for back-mutation to C8 yielded two independent revertants with two different screening approaches. However, this event was so infrequent (1 revertant in 50,000 colonies screened) that it was impossible to determine an exact switching frequency.

Since nonmotile mutants of H. pylori are not able to colonize in animal models, a strong selective pressure for motility must favor a motile phenotype in vivo, as has previously been shown in animal experiments (8). On the other hand, loss of this pressure—such as when bacteria are grown in vitro—leads to a frequent loss of this energy-consuming property. It is not clear which role this propensity for a relatively frequent switch to a nonmotile phenotype by mutation in fliP or by other mechanisms might play in vivo. It is conceivable that there is a niche for a proportion of the H. pylori bacteria where motility is no longer needed. In certain parts of the stomach mucosa not directly exposed to the shedding forces of mucus production or peristalsis, the energy-saving loss of motility might be advantageous for a lifestyle of low nutrient requirements, continuous slow growth, and tight adherence to cells.

Sequence polymorphisms and recombination in fliP.

Thirteen out of 22 motile strains studied had an adenosine residue in the fifth position of the repeat. This mutation would greatly reduce the probability of slipped-strand mispairing mutagenesis. The relevance of this polymorphism in the repeat sequence is not known. Since motility is essential for colonization, it seems unlikely that a hypermutatable nucleotide sequence that renders the motility system more susceptible to functional inactivation would occur so frequently unless this had biological significance. However, the occurrence of the CCCCACCC sequence in more than half of the strains analyzed, including all of the Asian strains, shows that the presence of the C8 repeat is not essential, at least not in all hosts. It is conceivable that there are subgroups of strains or strains in particular hosts where loss of motility is particularly detrimental, and strains with a CCCCACCC sequence therefore have a selective advantage. Given the frequency of recombination in H. pylori (35), this mutation in the repeat sequence would not have to be a dead end for a given strain because the C8 repeat could be reacquired by recombination. Analysis of the fliP sequences with the Homoplasy test (26) shows that fliP has been involved in frequent recombination events (data not shown). Finally, it has recently been shown in Neisseria meningitidis that the frequency of slipped-strand mispairing-mediated phase variation of capsule biosynthesis is strongly dependent on the presence or absence of the mutator gene dam (5). Although nothing is yet known about the occurrence of mutator phenotypes in H. pylori, it is possible that similar differences of mutation frequencies exist in H. pylori, and these might strongly affect the frequency of fliP-mediated motility switching.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge expert technical assistance by Susanne Friedrich, Doris Jaromin, and Barbara Beuerle. We thank M. Heep and N. Lehn for the strains from Singapore and E. Kunstmann and P. van Helden for strains from South Africa. We thank Chi Aizawa for critical reading of the manuscript.

The work in S.S.'s laboratory was supported by grants SU 133/2-3 (Gerhard Hess award) and SU 133/3-1 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. Work in K.A.E.'s laboratory was supported by Public Health Service grants R01 AI43643 and R29 DK-45340 from the NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman M, Azuma T, Berg D E, Ito Y, Morelli G, Pan Z J, Suerbaum S, Thompson S A, van der Ende A, van Doorn L J. Recombination and clonal groupings within Helicobacter pylori from different geographic regions. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:459–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alm R A, Ling L S, Moir D T, King B L, Brown E D, Doig P C, Smith D R, Noonan B, Guild B C, deJonge B L, Carmel G, Tummino P J, Caruso A, Uria-Nickelsen M, Mills D M, Ives C, Gibson R, Merberg D, Mills S D, Jiang Q, Taylor D E, Vovis G F, Trust T J. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1999;397:176–180. doi: 10.1038/16495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrutis K A, Fox J G, Schauer D B, Marini R P, Li X, Yan L, Josenhans C, Suerbaum S. Infection of the ferret stomach by isogenic flagellar mutant strains of Helicobacter mustelae. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1962–1966. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1962-1966.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appelmelk B J, Martin S L, Monteiro M A, Clayton C A, McColm A A, Zheng P, Verboom T, Maaskant J J, van den Eijnden D H, Hokke C H, Perry M B, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C M, Kusters J G. Phase variation in Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide due to changes in the lengths of poly(C) tracts in α3-fucosyltransferase genes. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5361–5366. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5361-5366.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bucci C, Lavitola A, Salvatore P, Del Giudice L, Massardo D R, Bruni C B, Alifano P. Hypermutation in pathogenic bacteria: frequent phase variation in meningococci is a phenotypic trait of a specialized mutator biotype. Mol Cell. 1999;3:435–445. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copass M, Grandi G, Rappuoli R. Introduction of unmarked mutations in the Helicobacter pylori vacA gene with a sucrose sensitivity marker. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1949–1952. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1949-1952.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eaton K A, Morgan D R, Krakowka S. Campylobacter pylori virulence factors in gnotobiotic piglets. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1119–1125. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1119-1125.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton K A, Morgan D R, Krakowka S. Motility as a factor in the colonisation of gnotobiotic piglets by Helicobacter pylori. J Med Microbiol. 1992;37:123–127. doi: 10.1099/00222615-37-2-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eaton K A, Suerbaum S, Josenhans C, Krakowka S. Colonization of gnotobiotic piglets by Helicobacter pylori deficient in two flagellin genes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2445–2448. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2445-2448.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan F, Ohnishi K, Francis N R, Macnab R M. The FliP and FliR proteins of Salmonella typhimurium, putative components of the type III flagellar export apparatus, are located in the flagellar basal body. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:1035–1046. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6412010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrero R L, Cussac V, Courcoux P, Labigne A. Construction of isogenic urease-negative mutants of Helicobacter pylori by allelic exchange. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4212–4217. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4212-4217.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geis G, Leying H, Suerbaum S, Mai U, Opferkuch W. Ultrastructure and chemical analysis of Campylobacter pylori flagella. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:436–441. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.3.436-441.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammerschmidt S, Hilse R, van Putten J P, Gerardy-Schahn R, Unkmeir A, Frosch M. Modulation of cell surface sialic acid expression in Neisseria meningitidis via a transposable genetic element. EMBO J. 1996;15:192–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hazell S L, Lee A, Brady L, Hennessy W. Campylobacter pyloridis and gastritis: association with intercellular spaces and adaptation to an environment of mucus as important factors in colonization of the gastric epithelium. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:658–663. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes K T, Mathee K. The anti-sigma factors. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:231–286. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Josenhans C, Ferrero R L, Labigne A, Suerbaum S. Cloning and allelic exchange mutagenesis of two flagellin genes from Helicobacter felis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:350–362. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Josenhans C, Labigne A, Suerbaum S. Comparative ultrastructural and functional studies of Helicobacter pylori and Helicobacter mustelae flagellin mutants: both flagellin subunits, FlaA and FlaB, are necessary for full motility in Helicobacter species. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3010–3020. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3010-3020.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karim Q N, Logan R P, Puels J, Karnholz A, Worku M L. Measurement of motility of Helicobacter pylori, Campylobacter jejuni, and Escherichia coli by real time computer tracking using the Hobson BacTracker. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:623–628. doi: 10.1136/jcp.51.8.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kostrzynska M, Betts J D, Austin J W, Trust T J. Identification, characterization, and spatial localization of two flagellin species in Helicobacter pylori flagella. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:937–946. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.3.937-946.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labigne A, Cussac V, Courcoux P. Shuttle cloning and nucleotide sequences of Helicobacter pylori genes responsible for urease activity. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1920–1931. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.1920-1931.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee A, O'Rourke J, De Ungria M C, Robertson B, Daskalopoulos G, Dixon M F. A standardized mouse model of Helicobacter pylori infection: introducing the Sydney strain. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1386–1397. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leunk R D, Johnson P T, David B C, Kraft W G, Morgan D R. Cytotoxic activity in broth-culture filtrates of Campylobacter pylori. J Med Microbiol. 1988;26:93–99. doi: 10.1099/00222615-26-2-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X, Matsumura P. The FlhD/FlhC complex, a transcriptional activator of the Escherichia coli flagellar class II operons. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7345–7351. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7345-7351.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malakooti J, Ely B, Matsumura P. Molecular characterization, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the fliO, fliP, fliQ, and fliR genes of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:189–197. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.189-197.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maskell D J, Szabo M J, Butler P D, Williams A E, Moxon E R. Phase variation of lipopolysaccharide in Haemophilus influenzae. Res Microbiol. 1991;142:719–724. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90086-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maynard Smith J, Smith N H. Detecting recombination from gene trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:590–599. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minamino T, Macnab R M. Components of the Salmonella flagellar export apparatus and classification of export substrates. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1388–1394. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1388-1394.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Toole P W, Kostrzynska M, Trust T J. Non-motile mutants of Helicobacter pylori and Helicobacter mustelae defective in flagellar hook production. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:691–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park S F, Purdy D, Leach S. Localized reversible frameshift mutation in the flhA gene confers phase variability to flagellin gene expression in Campylobacter coli. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:207–210. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.1.207-210.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saunders N J, Peden J F, Hood D W, Moxon E R. Simple sequence repeats in the Helicobacter pylori genome. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1091–1098. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmitz A, Josenhans C, Suerbaum S. Cloning and characterization of the Helicobacter pylori flbA gene, which codes for a membrane protein involved in coordinated expression of flagellar genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:987–997. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.987-997.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spohn G, Scarlato V. Motility of Helicobacter pylori is coordinately regulated by the transcriptional activator FlgR, an NtrC homolog. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:593–599. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.593-599.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suerbaum S, Josenhans C, Labigne A. Cloning and genetic characterization of the Helicobacter pylori and Helicobacter mustelae flaB flagellin genes and construction of H. pylori flaA- and flaB- negative mutants by electroporation-mediated allelic exchange. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3278–3288. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3278-3288.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suerbaum S, Maynard Smith J, Bapumia K, Morelli G, Smith N H, Kunstmann E, Dyrek I, Achtman M. Free recombination within Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12619–12624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomb J-F, White O, Kerlavage A R, Clayton R A, Sutton G G, Fleischmann R D, Ketchum K A, Klenk H P, Gill S, Dougherty B A, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness E F, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak H G, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzegerald L M, Lee N, Adams M D, Hickey E K, Berg D E, Gocayne J D, Utterback T R, Peterson J D, Kelley J M, Cotton M D, Weidman J M, Fujii C, Bowman C, Watthey L, Wallin E, Hayes W S, Borodovsky M, Karp P D, Smith H O, Fraser C M, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trieu-Cuot P, Gerbaud G, Lambert T, Courvalin P. In vivo transfer of genetic information between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. EMBO J. 1985;4:3583–3587. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Belkum A, Scherer S, van Alphen L, Verbrugh H. Short-sequence DNA repeats in prokaryotic genomes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:275–293. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.275-293.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Ham S M, van Alphen L, Mooi F R, van Putten J P. Phase variation of H. influenzae fimbriae: transcriptional control of two divergent genes through a variable combined promoter region. Cell. 1993;73:1187–1196. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90647-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang G, Rasko D A, Sherburne R, Taylor D E. Molecular genetic basis for the variable expression of Lewis Y antigen in Helicobacter pylori: analysis of the alpha (1,2) fucosyltransferase gene. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1265–1274. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]