Abstract

Importance

Vaccines are a safe and efficacious way to prevent a variety of infectious diseases. Over the course of their existence, vaccines have prevented immeasurable morbidity and mortality in humans. Typical symptoms of systemic immune activation are common after vaccines and may include local soreness, myalgias, nausea, and malaise. In the vast majority of cases, the severity of the infectious disease outweighs the risk of mild adverse reactions to vaccines. Rarely, vaccines may be associated with neurological sequela that ranges in severity from headache to transverse myelitis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and Guillain–Barre syndrome (GBS). Often, a causal link cannot be confirmed, and it remains unclear if disease onset is directly related to a recent vaccination.

Observations

This review serves to summarize reported neurologic sequelae of commonly used vaccines. It will also serve to discuss potential pathogenesis. It is important to note that many adverse events or reactions to vaccines are self-reported into databases, and causal proof cannot be obtained.

Conclusions and relevance

Recognition of reported adverse effects of vaccines plays an important role in public health and education. Early identification of these symptoms can allow for rapid diagnosis and potential treatment. Vaccines are a safe option for prevention of infectious diseases.

Keywords: Vaccine, Immunization, Central nervous system, Neurologic sequela, Post-vaccination, Demyelination

Introduction

Bacterial, viral, and fungal pathogens have led to extensive morbidity and mortality in humans for millennia. The discovery of antibiotics in 1928 has resulted in longer human lifespans and avoided innumerable deaths. Over a century prior, Edward Jenner inoculated James Phipps with cowpox resulting in the first vaccine against small pox and discovering a new mechanism to prevent deadly viral infections [1].

Immunization of the body against a pathogen can occur actively or passively. Active immunization occurs when the immune system encounters a foreign antigen. An antigen is defined as a foreign molecular structure on or in pathogens which can trigger an immune response in humans. In active immunization, the response produces antibodies and upregulates immune cells [1, 2]. Passive immunization occurs when antibodies are transferred into circulation, such as maternal transmission.

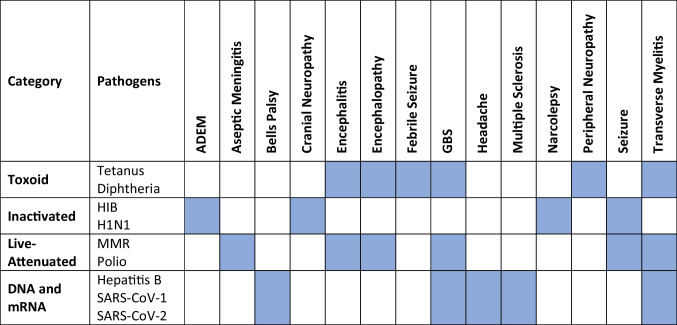

Vaccines are classified into different categories, including toxoid, inactivated, subunit, live-attenuated subtypes, and DNA or mRNA (Table 1) [1]. Toxoid vaccines utilized weakened toxins produced by pathogens and include tetanus, diphtheria, botulism, and cholera vaccines [1]. Inactivated vaccines contain inactivated microorganisms which can no longer multiply and include hepatitis A, rabies, typhoid, and meningococcal vaccines. Inactivated vaccines require multiple doses in order to induce protective immunity and may require boosters later in life [1, 2]. Live-attenuated vaccines consist of weakened, live microorganisms and result in immune responses identical to that produced by natural infection [1, 2]. DNA and mRNA vaccines are the new wave of vaccines and have been developed against influenza, malaria, hepatitis B, HIV-1, Ebola, Zika virus, rabies virus, and SARS-CoV-2 [3, 4].

Table 1.

Summary of neurological sequelae within vaccine categories

Potential neurologic adverse events can be broken up into two general categories: autoimmune demyelinating disease and non-demyelinating disease. Demyelinating diseases occur by damage to the myelin sheath surrounding nerves in the central and peripheral nervous system. This results in slowed conduction of nervous system impulses and can result in a variety of clinical manifestations. Acute demyelinating disease can be triggered following viral and bacterial infections and is caused by an autoimmune mechanism [5]. In the central nervous system, demyelinating diseases include acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) and transverse myelitis, while in the peripheral nervous system, acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuritis (AIDP, also known as Guillain–Barre syndrome (GBS)) can be seen [5, 6]. Non-demyelinating disease after vaccines can include encephalopathy, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, febrile seizures, and neuropathy [7]. The incidence of these diseases is low in the general population and generally considered rare diseases. Globally, encephalitis affects 19.33 people per 100,000 annually, and transverse myelitis affects 1.34–4.6 people per million annually [8, 9]. GBS has a worldwide prevalence of 1 to 2 cases per 100,000 people per year [10, 11]. Febrile seizures occur in approximately 2–5% of children [12].

This review will serve to summarize previously reported neurologic complications of common vaccinations and discuss the relevant pathophysiology. It aims to provide a central location for clinicians and researchers to review the previously reported neurologic complications of vaccines. It is important to note that many adverse events or reactions to vaccines are self-reported into databases, and causal proof cannot be obtained. The observed incidence is reported in Table 2 for each pathogen. While neurologic complications have been reported for the majority of vaccines, the benefits of vaccines far outweigh the risks. There is abundant evidence vaccines have prevented countless deaths since their introduction. Most reporting regarding vaccine adverse effects is through self-reporting and reports by physicians which can result in slightly skewed data.

Table 2.

Summary of reported neurological sequelae of vaccines

| Pathogen | Non-demyelinating (reported frequency) | Demyelinating (reported frequency) |

|---|---|---|

| Diphtheria and tetanus |

Encephalopathy (case report) Febrile seizure (7/133,500) Hemiplegia (2/133,500) |

Brachial neuritis (case report) Encephalitis (case report) GBS (case report) Peripheral mononeuropathy (28 cases) Polyneuromyeloencephalopathy (case report) Transverse myelitis (3 case reports) |

| Measles and mumps |

Aseptic meningitis (1/4000) Encephalopathy (case report) Lymphocytic meningitis (case report) Seizure (26/170,000) |

Encephalitis (47/3,000,000 and 7/174,725) GBS (2 case reports) Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (10 cases) Transverse myelitis (case report) |

| Polio |

GBS (10/1,170,000) Transverse myelitis (2 case reports) |

|

| Hepatitis B |

GBS (9/850,000 and 5/53,618) Transverse myelitis (case report) Optic neuritis (case report) Multiple sclerosis (2 case reports) |

|

| Haemophilus influenzae type B |

Hypotonic unresponsive episode (7 cases) Seizure (55 cases) |

|

| Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 | Seizure (23 cases) |

ADEM (8 cases) Cranial neuropathies (12 cases) GBS (81 cases) Narcolepsy (37 cases) |

| SARS-CoV-1 | Headache (case report) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Headache (42/108) |

Transverse myelitis (99 cases) GBS (IRR: 2.90) Bell’s palsy (7/40,000) |

Methods

In October of 2021, we performed a systematic review of published literature using PubMed and Google Scholar. We identified clinical studies reporting outcomes on patients who reported new onset neurological symptoms or conditions after a recent vacation.

Our search terms included vaccine, immunization, post-vaccination, central nervous system, neurologic sequela, demyelination, headache, seizure, encephalitis, GBS, diphtheria, tetanus, measles, mumps, rabies, polio, hepatitis B, haemophilus influenzae type B, influenza A virus subtype H1N1, and SARS-CoV-2.

Additionally, we reviewed pertinent articles which deal with the neurologic syndromes that often present after vaccination, including encephalitis, GBS, and central demyelinating disorders.

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to identify appropriate articles.

Inclusion:

Studies or reports of patients with recent vaccine administration who had onset of a new neurological symptom or condition post-vaccination

A vaccine in clinical use today

-

Reports with thorough clinical information including timing and onset of symptoms in relation to vaccination

Exclusion:

Articles which proposed hypotheses

Quantitative outcomes not provided

Articles which did discuss post-vaccination complications

Discussion

Tetanus and diphtheria vaccines

A tetanus infection is caused by the tetanospasmin exotoxin produced by Clostridium tetani, a gram-positive spore forming anaerobic bacillus. The exotoxin enters the nervous system by binding to a receptor at peripheral nerve endings. The toxin is internalized via endocytosis and travels retrograde along the axon to the central nervous system [13]. The neurologic sequalae of a tetanus infection include irritability, sleep disturbances, myoclonus, and electroencephalogram abnormalities [14]. Animal studies have demonstrated inoculation with small amounts of toxin induce protective neutralizing antibodies [13, 15].

Diphtheria is an acute respiratory infection caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Patients typically develop myocarditis, peripheral neuritis, and a fibrinous pharyngeal membrane [16]. The diphtheria toxin is made up of A and B toxins. Fragment A is an enzyme that blocks intracellular protein synthesis, while fragment B recognizes receptors on mammalian cells and facilitates translocation of fragment A into cells [17, 18]. Neutralizing antibodies against fragment B are protective in humans. Diphtheria antiserum raised in horses was used in the late nineteenth century to treat human diphtheria via passive immunization [15, 19]. In the USA today, children are vaccinated with a combined diphtheria and tetanus toxoid vaccine in five doses starting at 2 months through 6 years old.

Febrile seizures are a common compilation of vaccines in children. The North West Thames study observed 133,500 children from 1975 through 1981 who completed three doses of diphtheria (DT) vaccine. Only seven children reported seizures post-vaccination and none incurred lasting effects. Two other neurological events included a seizure complicated by hemiplegia and new-onset hemiparesis, both of which were normal on follow-up examination [20]. Another North West Thames study in 1979 identified 21 children under the age of two who were hospitalized with a neurological event after the DT vaccine. Twenty of the children were hospitalized for a febrile seizure and one for encephalopathy. In the 1980s, clinical trials showed no serious neurologic adverse events after receipt of DT [21, 22]. Two case series from that time also evaluated for adverse events and found no adverse neurologic events following receipt of DT [23, 24]. Case reports highlighting neurological complications of DT included polyneuromyeloencephalopathy, encephalitis, transverse myelitis, and syncope with visual disturbance [25–28].

In the peripheral nervous system, cases of GBS have been reported after DT, diphtheria, and tetanus vaccine administration [15, 28–31]. Additionally, cases of peripheral mononeuropathy and brachial neuritis have been reported after the tetanus toxoid [32–35].

Measles and mumps vaccines

Measles is a viral infection caused by a paramyxovirus and can lead to significant morbidity. Complications of the viral infection including otitis media, pneumonia, para-infectious encephalitis, and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Initially, measles was treated with immune gamma globulin postexposure prophylaxis [15]. This protection needed to be administered shortly after exposure and was short-lived. An inactivated vaccine was developed but discontinued due to poor efficacy [15]. The live-attenuated measles vaccine has resulted in longer lasting immunity with fewer side effects.

Mumps viral infections can result in serious neurological conditions, including aseptic meningitis, meningoencephalitis, and deafness [36, 37]. Initially, an inactivated vaccine was developed, but it had poor efficacy and was replaced by a live-attenuated vaccine [38].

Reported neurologic sequela of the measles and/or mumps vaccines includes encephalopathy, aseptic meningitis, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, seizures, and transverse myelitis. The first case of encephalopathy after the measles vaccine was reported in 1967 [39]. From 1965 to 1967, a case series described 23 reports of neurological disease after the measles vaccine, 18 of which were encephalitis [40]. The CDC received reports of 59 patients with new onset neurologic disorders within 6–15 days following vaccination of measles vaccination, the period of the highest viral replication [41]. Large studies out of the UK (3 million doses) and former East Germany (174,725 doses) reported 47 and 7 cases of encephalitis, respectively [42, 43]. For the MMR vaccination, 212 adverse events were reported to the Swedish health authorities between 1982 and 1984 including 17 neurologic cases (10 with encephalitis, 6 with motor symptoms, and 1 with seizure) [44].

The National Childhood Encephalopathy Study reported an association between measles vaccination and onset of convulsions or encephalopathy within 7 to 14 days of receiving the vaccine [45]. Aseptic meningitis has been reported after the MMR vaccination [46–49]. One study showed an increase in cases of lymphocytic meningitis in patients who received MMR compared to those who had not [46]. This was thought to be secondary to the Urabe vaccine strain which was suspended in many countries. Seizures have also been reported in patients receiving the live measles vaccine. In the North West Thames region of England between 1975 and 1981, there were 26 reports of convulsions out of 170,000 children who received the live measles vaccine [20]. Additional case series describe seizures after measles vaccination [50, 51].

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) was first reported after vaccination with the live attenuated measles vaccine in 1968 [15]. Following this development, additional reports of SSPE after the measles vaccine emerged [52–55]. Transverse myelitis, another demyelinating condition, has also been reported [41]. Lastly, GBS has also been reported in patients receiving the measles vaccine or MMR [41, 56].

Rabies vaccine

The rabies vaccine was first developed in the 1880s by Louis Pasteur and was produced from the infected rabbit spinal cord [57, 58]. In 1972, it was documented that a rabies vaccine which was prepared in unmyelinated neonatal mouse brains resulted in some cases of an acute polyneuritis similar to GBS [59]. Rabies vaccines using neural elements are now rarely used given the severity of neurologic complications [60]. Modern rabies vaccines are typically developed using purified chick embryo cells and is inactivated [61]. The modern vaccine is widely tolerated with no reports of serious neurologic sequela [62, 63].

Polio vaccines

Poliomyelitis is caused by an enterovirus and can result in infection of the central nervous system. The clinical manifestations can vary from asymptomatic infection or mild illness to aseptic meningitis and paralytic poliomyelitis. The paralytic disease is caused by infection of the central nervous system resulting in viral replication in the anterior horn motor neurons, motor cortex, and brainstem [64]. In 1949, development of a new tissue culture technique to support viral growth was critical in developing the vaccine [65]. Two forms of the vaccine were ultimately created: inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) and the live attenuated vaccine, known as the oral polio vaccine (OPV). The IPV was developed by Jonas Salk in 1953 [66].

Neurologic side effects of the vaccine can include transverse myelitis, GBS, and polio-like symptoms. Case reports exist of transverse myelitis in patients receiving the OPV [28, 67]. GBS has also been reported in the literature [68, 69]. While these conditions are rare, they can lead to morbidity, and providers should be vigilant to assess for these complications.

Hepatitis B vaccine

The hepatitis B vaccine (HBV) was introduced in 1982 and initially derived from plasma. Today, the HBV is developed with recombinant technology using yeast to produce the viral surface antigen [70]. A surveillance study of the first three years after introduction included 850,000 vaccinations and reported nine cases of GBS [71]. An observational study of 43,618 Alaskan natives reported five patients with GBS, including two who developed GBS long after vaccination (three and nine months) [72]. Other reported demyelinating conditions included transverse myelitis, optic neuritis, new onset multiple sclerosis, and flare of multiple sclerosis [71, 73]. These episodes did not occur with greater frequency than seen in the general public [15].

Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccines

The haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine was introduced in 1990 and has nearly eliminated HiB meningitis in the USA. It is an inactivated vaccine that uses a polysaccharide conjugate. Over a 23-year coverage period, the U.S. Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System received 29,747 reports regarding the HiB vaccine, which included only 55 seizures and 7 hypotonic-hyporesponsive episodes [74]. Japan undertook a study to prospectively evaluate the safety of the HiB vaccine. Out of 11,197 vaccinated children, there was only one report of seizure [75]. Overall, there are very few reported adverse neurological side effects to the HiB vaccine.

Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 vaccine

The H1N1 influenza outbreak spreads across the world in 2009, and a vaccine became available later that year. There were several reports of GBS, seizures, cranial neuropathies, and ADEM after H1N1 vaccines [76–78]. Within a year, consistent reports began to emerge of new-onset narcolepsy within 12 weeks of vaccination [79]. In one report from Sweden, all patients were positive for HLA-DQB1*0602, and this HLA type imparted a 25-fold increased risk of developing narcolepsy after vaccination [79]. New onset narcolepsy was also reported after infection with H1N1 influenza suggesting a unique viral antigen was the likely culprit [80]. One study found that the European inactivation and purification protocol was associated with a higher risk of narcolepsy after vaccination compared to vaccines prepared with the Canadian protocol [80]. The etiology of narcolepsy type 1 is under debate. One of the leading theories proposes that narcolepsy is, in fact, an autoimmune disease caused by loss of hypocretin secreting cells in the lateral hypothalamus [81]. The strong association with HLA-DQB1*0602 and onset of disease after viral exposure supports this theory.

SARS-CoV-1 vaccine

A successful commercial vaccine against SARS-CoV-1 has not been developed. Animal studies demonstrated promising targets with live attenuated vaccines [82–86]. A DNA vaccine was developed and also shown to be effective in animal models [87]. A phase 1 trial of an inactivated vaccine reported no neurologic adverse events [88]. A small, phase 1 clinical trial of a DNA vaccine showed encouraging results, and only one of ten patients reported transient headache [89].

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine

There have been a numerous studies and case reports looking into the efficacy and adverse effects of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Overall, the rates of adverse neurological events after vaccination are significantly lower than after a natural infection and depends on the type of vaccination. The types of neurologic conditions reported include GBS, Bell’s palsy, hemorrhagic stroke, transverse myelitis (TM), and myasthenia gravis (MG). There are two main types of vaccinations available in the USA. Viral vector vaccines are available from AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) and Johnson and Johnson (Ad26.COV2.S), while mRNA vaccines are available from Moderna (mRNA-1273) and BioNTech/Pfizer (BNT162b2). CoronaVac (PiCoVacc) is a whole inactivated virus vaccine. The most common adverse neurologic event after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination is a self-limited headache. Depending on age, 51–59% of individuals receiving the Pfizer vaccine experience a headache compared to 17–23% of controls [90]. A thorough analysis by Klein et al. of adverse events after mRNA vaccinations to 6.2 million individuals showed no excess cases of Bell’s palsy, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, or GBS per million doses. There was a small increase in excess cases per million doses for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (0.2 [CI − 1.1 to 0.5]), TM (0.1 [CI − 1.6 to 0.2]), encephalitis (0.3 [CI − 1.8 to 1.1]), and seizure (0.9 [CI − 4.8 to 5.6]) [91].

Myelitis

Three cases of transverse myelitis were reported in the preliminary AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) vaccine study. The first case occurred 14 days after the booster dose and was deemed likely related to the vaccine by an independent neurological committee [92]. The second case occurred 10 days after the vaccine in a patient with undiagnosed multiple sclerosis (MS), which begs the question whether the MS flare was triggered by the vaccine or unrelated. The third case occurred 68 days after vaccination, and an independent neurological committee deemed it unrelated to the vaccine [92]. Since this initial publication, other reports of TM after AstraZeneca vaccination (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) have emerged [93]. There have been rare reports of TM after the mRNA vaccines including one case within 48 h of receiving the Pfizer vaccine (BNT162b2) and another within 5 days of receiving the Moderna vaccine (mRNA-1273) [94, 95]. Kahn et al. reported a case of TM one day after mRNA-1273 vaccination and reviewed the National Board reporting records in the UK, which received notice of 22 cases of myelitis after Pfizer vaccination and 72 cases of myelitis after AstraZeneca vaccination [96]. Both the US and UK have comprehensive adverse event reporting sites, but reports are not reviewed or verified.

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS)

GBS has been reported after vaccination against SARS-CoV-2. A thorough review of the literature found 14 cases of GBS after AstraZeneca vaccination (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19), four after Pfizer vaccination (BNT162b2), and one after Johnson and Johnson vaccination (Ad26.COV2.S) [97]. GBS has been reported 20 days after Pfizer vaccination (BNT162b2) as well as 21 days and 10 days after AstraZeneca vaccination (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) [98–100]. Given GBS rarely occurs after vaccination, CDC guidelines recommend patients with prior GBS illnesses obtain the vaccine series. A case–control study of > 40 million individuals in the UK compared participants who had a COVID-19 illness to those who received AstraZeneca or Pfizer vaccination [101]. Neurological complications within 28 days were included. There was an increased risk of GBS (IRR: 2.90; CI 2.15–3.92) after AstraZeneca vaccination. There was a much higher risk of GBS after a COVID-19 illness (IRR: 5.25; CI 3.00–9.18). Overall, this translates to an estimated 38 excess cases of GBS per 10 million individuals after AstraZeneca vaccination and 145 excess cases per 10 million individuals after a COVID-19 illness.

Bell’s palsy

In the original vaccine trials, there were seven cases of Bell’s palsy cases reported among 40,000 participants receiving the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. There was one case of Bell’s palsy in the placebo groups, which suggests that there may be a small increased risk of Bell’s palsy after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination [102]. Further studies have found that post-vaccine Bell’s palsy occurrence is quite rare. A study of > 400,000 participants found 16 confirmed cases after Pfizer vaccination and 28 cases after CoronaVac [103]. When reviewing the US Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System [VAERS], Sato et al. found no increased risk of Bell’s palsy after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination compared to the influenza vaccine [104]. A case–control study in Israel found no association between the risk of Bell’s palsy and the Pfizer vaccine [105]. Of note, Bell’s palsy has been reported after COVID-19 illness. A study of almost 350,000 participants found 248 cases of Bell’s palsy within eight weeks of confirmed COVID-19 illness [106]. As with every reported adverse event, the risk of occurrence after vaccine must be weighed with risk of occurrence after illness.

Myasthenia gravis

MG exacerbations can be triggered vaccination or infections. COVID-19 illnesses have been associated with severe illness and poor outcomes in patients with MG. One study in Brazil found that 87% of patients with MG who contracted COVID were admitted to the ICU, and almost three quarters required mechanical ventilation [107]. In contrast, vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 appears to be relatively safe based on preliminary data. A case series of patients with MG demonstrated only a slight self-limited worsening of symptoms within 4 weeks of vaccination in 2 patients. One case of MG exacerbation requiring intubation has been reported after Moderna vaccination [108].

Conclusion

Vaccines are an important asset in preventing the spread of a plethora of infectious diseases. The introduction of vaccines has led to the prevention of immeasurable mortality in humans. While there may be side effects or sequelae after vaccine administration, in the vast majority of cases, the adverse effects of the vaccine are dwarfed by the possible severity of the diseases which they defend against.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rabello GD. Postvaccinal neurological complications. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2013;71(9B):747–751. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20130163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baxter D. Active and passive immunity, vaccine types, excipients and licensing. Occup Med (Lond) 2007;57(8):552–556. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqm110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kutzler MA, Weiner DB. DNA vaccines: ready for prime time? Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(10):776–788. doi: 10.1038/nrg2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pardi N, et al. mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2018;17(4):261–279. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anilkumar AC, Foris LA, Tadi P, Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, in StatPearls. © 2020. Treasure Island FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simone CG, Emmady PD, Transverse myelitis, in StatPearls. © 2020. Treasure Island FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piyasirisilp S, Hemachudha T. Neurological adverse events associated with vaccination. Curr Opin Neurol. 2002;15(3):333–338. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200206000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H, et al. Global magnitude of encephalitis burden and its evolving pattern over the past 30 years. J Infect. 2022;84(6):777–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berman M, et al. Acute transverse myelitis: incidence and etiologic considerations. Neurology. 1981;31(8):966–966. doi: 10.1212/WNL.31.8.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bragazzi NL, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Guillain-Barré syndrome and its underlying causes from 1990 to 2019. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18(1):264. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02319-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortiz Torres M, GA, Mesfin FB (2022) Brachial plexitis. StatPearls Publishing. [PubMed]

- 12.Seizures SOF, Febrile seizures: guideline for the neurodiagnostic evaluation of the child with a simple febrile seizure. Pediatrics 127(2) 389–394. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Bae C, Bourget D, Tetanus, in StatPearls. © 2020. Treasure Island FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Illis LS, Taylor FM. Neurological and electroencephalographic sequelae of tetanus. Lancet. 1971;1(7704):826–830. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(71)91496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adverse events associated with childhood vaccines: evidence bearing on causality, ed. K.R. Stratton, C.J. Howe, and R.B. Johnston, Jr. 1994, Washington DC: 1994 by the National Academy of Sciences. [PubMed]

- 16.Chaudhary A, Pandey S, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, in StatPearls. © 2020. Treasure Island FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madshus IH. The N-terminal alpha-helix of fragment B of diphtheria toxin promotes translocation of fragment A into the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(26):17723–17729. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)32500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stenmark H, et al. Interactions of diphtheria toxin B-fragment with cells Role of amino- and carboxyl-terminal regions. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(13):8957–62. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)50373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cherry JD. The history of pertussis (Whooping Cough); 1906–2015: facts, myths, and misconceptions. Current Epidemiology Reports. 2015;2(2):120–130. doi: 10.1007/s40471-015-0041-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollock TM, Morris J. A 7-year survey of disorders attributed to vaccination in North West Thames region. Lancet. 1983;1(8327):753–757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(83)92037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cody CL, et al. Nature and rates of adverse reactions associated with DTP and DT immunizations in infants and children. Pediatrics. 1981;68(5):650–660. doi: 10.1542/peds.68.5.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barkin RM, et al. Primary immunization with diphtheria-tetanus toxoids vaccine and diphtheria-tetanus toxoids-pertussis vaccine adsorbed: comparison of schedules. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1985;4(2):168–171. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198503000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feery BJ. Incidence and type of reactions to triple antigen (DTP) and DT (CDT) vaccines. Med J Aust. 1982;2(11):511–515. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1982.tb132550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waight PA, et al. Pyrexia after diphtheria/tetanus/pertussis and diphtheria/tetanus vaccines. Arch Dis Child. 1983;58(11):921–923. doi: 10.1136/adc.58.11.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quast U, Hennessen W, Widmark RM. Mono- and polyneuritis after tetanus vaccination (1970–1977) Dev Biol Stand. 1979;43:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Read SJ, Schapel GJ, Pender MP. Acute transverse myelitis after tetanus toxoid vaccination. Lancet. 1992;339(8801):1111–1112. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90703-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Topaloglu H, et al. Optic neuritis and myelitis after booster tetanus toxoid vaccination. Lancet. 1992;339(8786):178–179. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90241-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whittle E, Robertson NR. Transverse myelitis after diphtheria, tetanus, and polio immunisation. Br Med J. 1977;1(6074):1450. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6074.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holliday PL, Bauer RB. Polyradiculoneuritis secondary to immunization with tetanus and diphtheria toxoids. Arch Neurol. 1983;40(1):56–57. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1983.04050010076025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newton N, Jr, Janati A. Guillain-Barré syndrome after vaccination with purified tetanus toxoid. South Med J. 1987;8:1053–4. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198708000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollard JD, Selby G. Relapsing neuropathy due to tetanus toxoid Report of a case. J Neurol Sci. 1978;1–2:113–25. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(78)90232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bensasson M, Lanoe R, Assan R. A case of algodystrophic syndrome of the upper limb following tetanus vaccination. Sem Hop. 1977;53(36):1965–1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eicher W, Neundörfer B. Paralysis of the recurrent laryngeal nerve following a booster injection of tetanus toxoid (associated with local allergic reaction) Munch Med Wochenschr. 1969;111(34):1692–1695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiwit JC. Neuralgic amyotrophy after administration of tetanus toxoid. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984;47(3):320. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.47.3.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ling CM, Loong SC. Injection injury of the radial nerve. Injury. 1976;8(1):60–62. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(76)90012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bester JC. Measles and measles vaccination: a review. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1209–1215. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su, S.B., H.L. Chang, and A.K. Chen, Current status of mumps virus infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and vaccine. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020. 17(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Enders JF. Mumps; techniques of laboratory diagnosis, tests for susceptibility, and experiments on specific prophylaxis. J Pediatr. 1946;29:129–142. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(46)80101-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trump RC, White TR. Cerebellar ataxia presumed due to live, attenuated measles virus vaccine. JAMA. 1967;199(2):129–130. doi: 10.1001/jama.1967.03120020123031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nader PR, Warren RJ. Reported neurologic disorders following live measles vaccine. Pediatrics. 1968;41(5):997–1001. doi: 10.1542/peds.41.5.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landrigan PJ, Witte JJ. Neurologic disorders following live measles-virus vaccination. JAMA. 1973;223(13):1459–1462. doi: 10.1001/jama.1973.03220130011003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beale AJ. Measles vaccines. Proc R Soc Med. 1974;67(11):1116–1119. doi: 10.1177/003591577406701114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dietzsch HJ, Kiehl W. Central nervous complications following measles vaccination. Dtsch Gesundheitsw. 1976;31(52):2489–2491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taranger J, Wiholm BE. The low number of reported adverse effects after vaccination against measles, mumps, rubella. Lakartidningen. 1987;84(12):948–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alderslade R, B.M., Rawson NSB, Ross EM, Miller DL (1981) The National Childhood Encephalopathy Study: a report on 1000 cases of serious neurological disorders in infants and young children from the NCES research team. Department of Health and Social Security. Whooping Cough: Reports from the Committee on the Safety of Medicines and the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation.

- 46.Colville A, Pugh S. Mumps meningitis and measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine. Lancet. 1992;340(8822):786. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cizman M, et al. Aseptic meningitis after vaccination against measles and mumps. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8(5):302–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sugiura A, Yamada A. Aseptic meningitis as a complication of mumps vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10(3):209–213. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fujinaga T, et al. A prefecture-wide survey of mumps meningitis associated with measles, mumps and rubella vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10(3):204–209. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199103000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fescharek R, et al. Measles-mumps vaccination in the FRG: an empirical analysis after 14 years of use I Efficacy and analysis of vaccine failures. Vaccine. 1990;4:333–6. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(90)90090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abe T, et al. Acute and delayed neurologic reaction to inoculation with attenuated live measles virus. Brain Dev. 1985;7(4):421–423. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(85)80140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Payne FE, Baublis JV, Itabashi HH. Isolation of measles virus from cell cultures of brain from a patient with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. N Engl J Med. 1969;281(11):585–589. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196909112811103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parker JC, Jr, et al. Uncommon morphologic features in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). Report of two cases with virus recovery from one autopsy brain specimen. Am J Pathol. 1970;2:275–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gerson KL, Haslam RH. Subtle immunologic abnormalities in four boys with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. N Engl J Med. 1971;285(2):78–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197107082850203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cho CT, Lansky LJ, D'Souza BJ. Panencephalitis following measles vaccination. JAMA. 1973;224(9):1299. doi: 10.1001/jama.1973.03220230059028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grose C, Spigland I. Guillain-Barré syndrome following administration of live measles vaccine. Am J Med. 1976;60(3):441–443. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tarantola, A., Four thousand years of concepts relating to rabies in animals and humans its prevention and its cure. Trop Med Infect Dis 2017. 2(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Radhakrishnan, S., et al., Rabies as a public health concern in india-a historical perspective. Trop Med Infect Dis 2020. 5(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Held JR, Adaros HL. Neurological disease in man following administration of suckling mouse brain antirabies vaccine. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;46(3):321–327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tullu MS, et al. Neurological complications of rabies vaccines. Indian Pediatr. 2003;40(2):150–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramezankhani R, et al. A comparative study on the adverse reactions of purified chick embryo cell vaccine (PCECV) and purified vero cell rabies vaccine (PVRV) Arch Iran Med. 2016;19(7):502–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mahendra BJ, et al. Comparative study on the immunogenicity and safety of a purified chick embryo cell rabies vaccine (PCECV) administered according to two different simulated post exposure intramuscular regimens (Zagreb versus Essen) Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(2):428–434. doi: 10.4161/21645515.2014.995059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li R, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of purified chick-embryo cell rabies vaccine under Zagreb 2-1-1 or 5-dose Essen regimen in Chinese children 6 to 17 years old and adults over 50 years: a randomized open-label study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(2):435–442. doi: 10.4161/21645515.2014.994460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang Y, et al. Global prevalence and burden of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. A meta-analysis. 2020;95(19):e2610–e2621. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Enders JF, Weller TH, Robbins FC. Cultivation of the Lansing strain of poliomyelitis virus in cultures of various human embryonic tissues. Science. 1949;109(2822):85–87. doi: 10.1126/science.109.2822.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Salk JE. Recent studies on immunization against poliomyelitis. Pediatrics. 1953;12(5):471–482. doi: 10.1542/peds.12.5.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Douglas, S.D. and R. Anolik, Postvaccination paralysis in a 20-month-old child. Hosp Pract (Off Ed), 1981. 16(9): p. 40A, 40F. [PubMed]

- 68.Uhari M, Rantala H, Niemelä M. Cluster of childhood Guillain-Barré cases after an oral poliovaccine campaign. Lancet. 1989;2(8660):440–441. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90609-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kinnunen E, et al. Incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome during a nationwide oral poliovirus vaccine campaign. Neurology. 1989;39(8):1034–1036. doi: 10.1212/WNL.39.8.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hilleman MR. Yeast recombinant hepatitis B vaccine. Infection. 1987;15(1):3–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01646107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shaw FE, Jr, et al. Postmarketing surveillance for neurologic adverse events reported after hepatitis B vaccination Experience of the first three years. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127(2):337–52. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McMahon BJ, et al. Frequency of adverse reactions to hepatitis B vaccine in 43,618 persons. Am J Med. 1992;92(3):254–256. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90073-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Herroelen L, de Keyser J, Ebinger G. Central-nervous-system demyelination after immunisation with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine. Lancet. 1991;338(8776):1174–1175. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92034-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moro PL, et al. Adverse events following Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccines in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, 1990–2013. J Pediatr. 2015;166(4):992–997. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nishi J, et al. Prospective safety monitoring of <i>Haemophilus influenzae</i> type b and heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in Kagoshima. Japan Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;66(3):235–237. doi: 10.7883/yoken.66.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee SJ, et al. Neurologic adverse events following influenza A (H1N1) vaccinations in children. Pediatr Int. 2012;54(3):325–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Williams SE, et al. Causality assessment of serious neurologic adverse events following 2009 H1N1 vaccination. Vaccine. 2011;29(46):8302–8308. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cárdenas G, et al. Neurological events related to influenza A (H1N1) pdm09. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2014;8(3):339–346. doi: 10.1111/irv.12241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Szakács A, Darin N, Hallböök T. Increased childhood incidence of narcolepsy in western Sweden after H1N1 influenza vaccination. Neurology. 2013;80(14):1315. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828ab26f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ahmed SS, et al. Narcolepsy, 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic influenza, and pandemic influenza vaccinations: what is known and unknown about the neurological disorder, the role for autoimmunity, and vaccine adjuvants. J Autoimmun. 2014;50:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kornum BR, Jennum P. The case for narcolepsy as an autoimmune disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16(3):231–233. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2020.1719832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Graham RL, et al. A live, impaired-fidelity coronavirus vaccine protects in an aged, immunocompromised mouse model of lethal disease. Nat Med. 2012;18(12):1820–1826. doi: 10.1038/nm.2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Regla-Nava JA, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronaviruses with mutations in the E protein are attenuated and promising vaccine candidates. J Virol. 2015;89(7):3870–3887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03566-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.DeDiego ML, et al. A severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus that lacks the E gene is attenuated in vitro and in vivo. J Virol. 2007;81(4):1701–1713. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01467-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Netland J, et al. Immunization with an attenuated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus deleted in E protein protects against lethal respiratory disease. Virology. 2010;399(1):120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lamirande EW, et al. A live attenuated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus is immunogenic and efficacious in golden Syrian hamsters. J Virol. 2008;82(15):7721–7724. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00304-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang ZY, et al. A DNA vaccine induces SARS coronavirus neutralization and protective immunity in mice. Nature. 2004;428(6982):561–564. doi: 10.1038/nature02463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lin JT, et al. Safety and immunogenicity from a phase I trial of inactivated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine. Antivir Ther. 2007;12(7):1107–1113. doi: 10.1177/135965350701200702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martin JE, et al. A SARS DNA vaccine induces neutralizing antibody and cellular immune responses in healthy adults in a Phase I clinical trial. Vaccine. 2008;26(50):6338–6343. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kaur RJ, et al. Adverse events reported from COVID-19 vaccine trials: a systematic review. Indian J Clinical Biochemistry : IJCB. 2021;36(4):427–439. doi: 10.1007/s12291-021-00968-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Klein NP, et al. Surveillance for adverse events after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1390–1399. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.15072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Voysey M et al. (2020) Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet (London, England) p. S0140–6736(20)32661–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.Tan WY, et al. Longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis following ChAdOx1 nCOV-19 vaccine: a case report. BMC Neurol. 2021;21(1):395. doi: 10.1186/s12883-021-02427-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McLean P, Trefts L. Transverse myelitis 48 hours after the administration of an mRNA COVID 19 vaccine. Neuroimmunology Reports. 2021;1:100019. doi: 10.1016/j.nerep.2021.100019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Khan, E., et al., Acute transverse myelitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a case report and review of literature. Journal of neurology, 2021: p. 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Khan E, et al. Acute transverse myelitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a case report and review of literature. J Neurol. 2022;269(3):1121–1132. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10785-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Finsterer J, Scorza FA, Scorza CA. Post SARS-CoV-2 vaccination Guillain-Barre syndrome in 19 patients. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2021;76:e3286. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2021/e3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Razok A, et al. Post-COVID-19 vaccine Guillain-Barré syndrome; first reported case from Qatar. Annals of Med Surg. 2021;67:102540. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.McKean N, Chircop C. Guillain-Barré syndrome after COVID-19 vaccination. BMJ Case Reports. 2021;14(7):e244125. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-244125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Allen CM, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome variant occurring after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Ann Neurol. 2021;90(2):315–318. doi: 10.1002/ana.26144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Patone M, et al. Neurological complications after first dose of COVID-19 vaccines and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27(12):2144–2153. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01556-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ozonoff A, Nanishi E, Levy O. Bell's palsy and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(4):450–452. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00076-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wan EYF, et al. Bell's palsy following vaccination with mRNA (BNT162b2) and inactivated (CoronaVac) SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: a case series and nested case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00451-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sato K, et al. Facial nerve palsy following the administration of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: analysis of a self-reporting database. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;111:310–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shemer A, et al. Association of COVID-19 vaccination and facial nerve palsy: a case-control study. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;147(8):739–743. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2021.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tamaki A, et al. Incidence of Bell palsy in patients With COVID-19. JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery. 2021;147(8):767–768. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2021.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Camelo-Filho AE, et al. Myasthenia Gravis and COVID-19: Clinical characteristics and outcomes. Front Neurol. 2020;11:1053. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.01053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tagliaferri AR, et al. A case of COVID-19 vaccine causing a myasthenia gravis crisis. Cureus. 2021;13(6):e15581–e15581. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]