Abstract

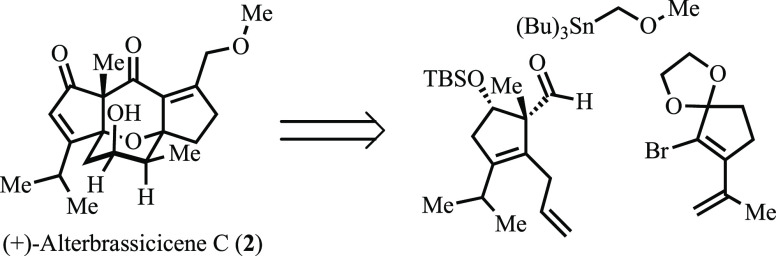

Herein, the first total synthesis of (+)-alterbrassicicene C (2) is described. Key features of the synthesis include an oxiranium mediated ether ring expansion, an oxa-Michael/retro-oxa-Michael cascade, and installation of a vinyl methoxy ether moiety via Stille coupling.

A recent report from Zhang and co-workers described the isolation of seven novel fusicoccane diterpenoids from the fungal plant pathogen Alternaria brassicicola.1 The most complex of the isolated congeners, alterbrassicicenes B and C (1 and 2, respectively), were found to possess unprecedented tetracyclic oxa-bridged ring systems (Figure 1). Although several fusicoccane diterpenoids possess important biological activity and have been the focus of numerous synthetic efforts (e.g., 3),2−5 there are no reports directed toward 1 and 2. Intrigued by the densely packed ring system of 2 and challenges associated with assembling the core structure, we began developing a total synthesis. Herein we report these recent efforts which have culminated in the successful synthesis of 2.

Figure 1.

Isolates from Alternaria brassicola (1, 2) and a previously prepared fusicoccane diterpenoid (3).

As illustrated retrosynthetically in Scheme 1, (+)-alterbrassiciciene C (2) was seen as arising from oxa-bicycle 4 via a series of reactions, central to which would be a retro-oxa-Michael/oxa-Michael cascade that would deliver the core bicycle. Additionally, we hoped to leverage the conformational preferences of intermediate 6 in facilitating the stereoselective transannular migration of oxygen (red) from C1 to C8 (cf., 6 and 2), a sequence envisioned as proceeding via the intermediacy of 5 and 4, which would respectively arise from halo-etherification and Lewis acid promoted 1,2-migration reactions. This strategic transfer of stereochemistry would then be predicated upon effectively setting the C1 hydroxyl stereochemistry in 6 via diastereoselective coupling of 7 and 8. The electrophilic component of this latter coupling, aldehyde 8, would arise from the known cyclopentanone 9.

Scheme 1. Retrosynthetic Analysis.

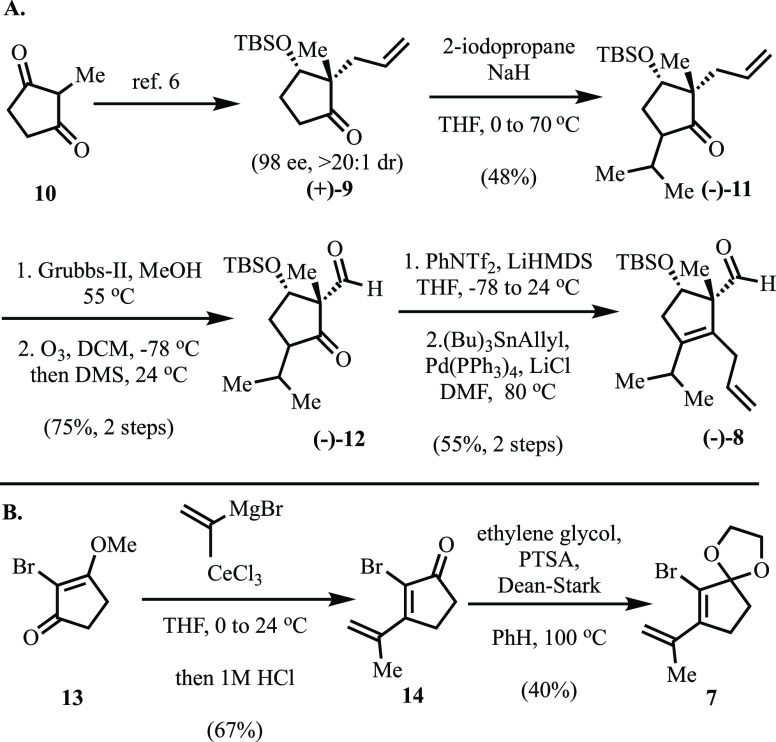

In implementing our planned approach (Scheme 2A), we began by employing a yeast mediated reductive desymmetrization to convert dione 10 to known ketone 9 in 98 ee and >20:1 dr.6,7 Alkylation of 9 with 2-iodopropane afforded the isopropyl ketone 11 as an inconsequential mixture of diastereomers. Migration of the terminal olefin in 11 (Grubbs-II) to the internal position was followed directly by reductive ozonolysis to provide aldehyde 12 in good yield.8 Treatment of 12 with lithium hexamethyldisilazide (LiHMDS) followed by phenyl triflimide furnished the corresponding vinyl triflate, which was further advanced via Stille cross-coupling to give skipped-diene 8 in 55% yield over the two steps.

Scheme 2. (A) Synthesis of Substituted Cyclopentene 8, (B) Synthesis of Bromo-cyclopentene 7.

Our point of departure for the preparation of vinyl bromide 7 (Scheme 2 B) was known bromo-vinylogous ester 13(9) which, upon exposure to Corey’s modified Danheiser–Stork conditions, furnished dienone 14 in 67% yield.10 Protection of the derived ketone with ethylene glycol under Dean–Stark conditions then gave the desired dioxolane 7.

Having prepared both 7 and 8, we turned next to their coupling (Scheme 3). To this end, we found that exposure of 7 to tBuLi in Et2O as solvent, followed by addition of aldehyde 8, produced a single diastereomer of intermediate alcohol 15 which, without purification, could be advanced to 6 via Grubbs-II-promoted ring-closing metathesis and in situ exposure to 2 M HCl (54% yield, two steps). Although high diastereoselectivity has been observed upon nucleophilic additions to α-methyl cyclopentene-carbaldehydes containing substituents capable of chelation, we were hesitant to base a structural assignment on these precedents given that siloxy ether 8 would be less prone to chelation.11 Fortunately, 6 proved to be a crystalline solid and thus single crystal X-ray analysis was employed to unambiguously assign the illustrated stereochemistry of the newly formed and critical C1-hydroxyl. To our delight, this analysis revealed that the highly diastereoselective coupling of 7 and 8 had furnished the C1-stereochemistry required for the planned synthesis. In addition, it appeared that, at least in the solid state, the cyclooctadiene moiety adopted a conformation poised for the planned transannular haloetherification. In practice, exposure of 6 to N-bromosuccinimide smoothly induced the latter reaction as well as concomitant removal of the TBS-group to furnish oxa-bicycle 5. Next, we began exploring conditions for advancing 5 via 1,2-migration of the newly formed oxygen bridge. Based on the pioneering work of Bartlett,12 we hoped that exposure of 5 to a suitable halophile would induce formation of an intermediate oxiranium ion (5a) which, upon capture by an external nucleophile (e.g., hydride), would generate 4 (Scheme 1), thereby setting both the C7-methyl and C8-oxo stereochemistry. This notion was thwarted by the discovery that, upon bromide abstraction (AgTFA) and presumed oxiranium formation, 5a rapidly undergoes intramolecular SN2′ addition of the pendant secondary alcohol and furnishes bis-oxa-bicycle 16 in excellent yield. This unexpected outcome was subsequently confirmed by single crystal X-ray analysis.

Scheme 3. Unexpected Formation of a Bis-oxa-bicycle.

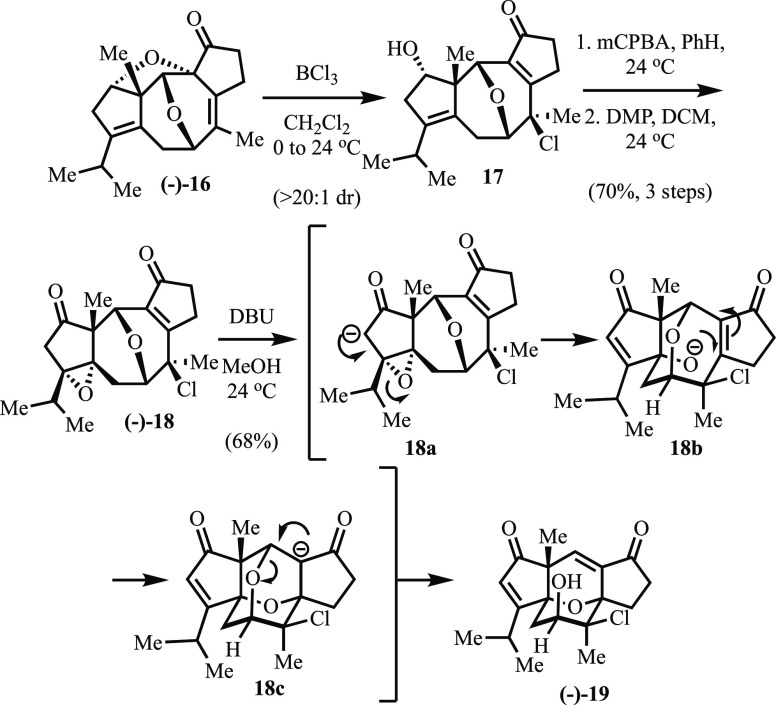

Although we had rapidly assembled the carbocyclic core of 2 and successfully initiated the transannular migration of hydroxyl from C1 to C8, the unanticipated formation of 16 derailed not only our planned approach to controlling the functionality at C7 and C8 but also our intention of employing a late-stage oxa-Michael to construct the core ring system. To prevent formation of 16, we explored masking the hydroxyl in 5 with a variety of protecting groups. However, these latter efforts proved unsuccessful, and we thus began considering methods whereby we might reverse the undesired SN2′ addition. To this latter end, we screened the reactivity of 16 toward a variety of Lewis acids (Scheme 4) and were delighted to discover that BCl3 rapidly promotes diastereoselective opening of the tetrahydrofuran in SN2′ fashion where chloride now serves as the nucleophile. Based on crystallographic data obtained on subsequent intermediates, the derived product (17) arises from exoaddition of the chloride anion to the oxa-bicycle thus delivering the illustrated diastereomer. Having reintroduced the enone moiety, we began preparing for oxa-Michael addition by subjecting 17 to hydroxyl-directed epoxidation with m-CPBA and subsequent oxidation with the Dess-Martin Periodinane. Exposure of the resultant keto-epoxide 18 to DBU in methanol initiates a cascade that involves β-eliminative epoxide opening (18a), trans-annular oxa-Michael addition (18b), and completion of the C1 to C8 oxygen transfer by β-eliminative opening of bis-oxa-adamantane intermediate 18c to furnish 19, which possesses the core 5/6/6/5 ring system of 2.13 Interestingly, a total of six C–C and C–O bonds are either broken or formed in the course of this oxa-Micahel/retro-oxa-Michael cascade.

Scheme 4. Novel Oxa-Michael Cascade.

With the core oxa-bicycle in place, efforts turned toward introducing the remaining two oxygen atoms (Scheme 5). The first was by way of a hydroxyl-directed nucleophilic epoxidation of 19, which furnished 20.14 The remaining oxygen resides in a pendent methoxy methyl moiety which we found could be introduced via Stille-coupling of known stannyl ether 22 with vinyl triflate 21,15 which was, in turn, readily produced from ketone 20 using a combination of KHMDS and Comins’s reagent. Interestingly, subjecting 21 to the Stille conditions resulted in not only the desired coupling but also the formation of a new tetrahydrofuran ring (cf. 21 and 23). Given that the epoxide had proved stable during the conversion of 20 to 21, we surmised that the ring forming event leading to 23 was not the result of simple nucleophilic epoxide opening but instead involved the likely intermediacy of a π-allyl-palladium species (21a) that forms from the initial Stille product.16,17

Scheme 5. Unexpected Alkyl-Stille Byproduct.

Unfortunately, efforts to advance 23 toward the natural product proved fruitless. Thus, it became necessary to prevent the deleterious ring formation by masking the nucleophilic hydroxyl moiety of 21. As illustrated in Scheme 6, this was accomplished by exposure of 21 to TESOTf in the presence of 2,6-lutidine to furnish the corresponding triethylsilyl ether 24. Subjecting 24 to the previously employed Stille coupling afforded the expected vinyl methoxy methyl ether 25 in 88% yield. Introduction of the final carbonyl and TES deprotection were next accomplished by treatment of 25 with BF3·Et2O, followed by TBAF. Monitoring by NMR indicated that this sequence proceeds by an initial Meinwald rearrangement (epoxide ring opening and 1,2-hydride shift) and concomitant double bond migration.18 This was followed by desilylation to enone 26. Finally, exposure of 26 to radical dehalogenation with AIBN and (Bu)3SnH afforded (+)-alterbrassicicene C (2).

Scheme 6. Completetion of (+)-Alterbrassicicene C.

In conclusion, the enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-alterbrassicicene C (2) has been achieved from known ketone 9. The synthetic strategy leverages the conformational preferences of the carbocyclic core structure to control the stereochemistry in a series of transannular carbon–oxygen bond forming reactions that culminate in an oxa-Michael/retro-oxa-Michael cascade reaction of epoxide 18, which delivers the requisite oxa-bicyclic core. In addition to providing enantioselective access to the natural product our synthetic efforts have produced numerous advanced intermediates that can be used to access additional congeners and, given the potent activity of many related fusicoccanes, assayed for biological activity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amy Jackson, Joey Tuccinardi, and Kevin Klausmeyer for their assistance in obtaining and analyzing X-ray crystallographic data. The authors also acknowledge financial support from the Welch Foundation (Chair, AA-006), then Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT, R1309), NIGMS-NIH (R01GM136759), and the NSF (CHE-1764240).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c12275.

Experimental procedures, analytical data, spectra, and crystallographic data for C25H40O3Si (6) and C19H24O3 (16) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Li F.; Lin S.; Zhang S.; Pan L.; Chai C.; Su J.-C.; Yang B.; Liu J.; Wang J.; Hu Z.; Zhang Y. Modified Fusicoccane-Type Diterpenoids from Alternaria Brassicicola. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 1931–1938. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uwamori M.; Osada R.; Sugiyama R.; Nagatani K.; Nakada M. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of Cotylenin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5556–5561. 10.1021/jacs.0c01774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R.; Robinson L. A.; Nevill R.; Reddy J. P. Strategies for the Synthesis of Fusicoccanes by Nazarov Reactions of Dolabellaidenones: Total Synthesis of (+)-Fusicoauritone. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 915–918. 10.1002/anie.200603853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman T. R.; Kuroo A.; Sato R.; Shenvi R. A.. Concise Synthesis of (−)-Cotylenol, a 14-3-3 PPI Molecular Glue ChemRxiv Preprint, 2022-08-28. 10.26434/chemrxiv-2022-dcbd8 (Accessed 2022-08-28). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B.; Wu Q.; Xu D.; Zhang X.; Ding Y.; Bao S.; Zhang X.; Wang L.; Chen Y. A Two-Phase Approach to Fusicoccane Synthesis to Uncover a Compound that Reduces Tumourigensis in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, 19. 10.1002/anie.202117476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks D. W.; Grothaus P. G.; Irwin W. L. Chiral Cyclopentanoid Synthetic Intermediates via Asymmetric Microbial Reduction of Prochiral 2,2-Disubstituted Cyclopentanediones. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 2820–2821. 10.1021/jo00135a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The desired diastereomer (10:1 dr) could be separated from the undesired diastereomer via flash column chromatography (see Supporting Information).

- Hanessian S.; Giroux S.; Larsson A. Efficient Allyl to Propenyl Isomerization in Functionally Diverse Compounds with a Thermally Modified Grubbs Second-Generation Catalyst. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 5481–5484. 10.1021/ol062167o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger A. C.; Kati W. M.; Carroll W. A.; Pratt J. K.; Hutchinson D. K. Anti-Viral Compounds U.S. Patent WO 2012083170, June 21, 2012.

- He F.; Bo Y.; Altom J. D.; Corey E. J. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of Aspidophytine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 6771–6772. 10.1021/ja9915201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi P. A.; Selnick H. G. Total Synthesis of (±)-Gnididione and (±)-Isognididione. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 202–209. 10.1021/jo00288a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett P. A.; Mori I.; Bose J. A. A Subtotal Synthesis of Methynolide via an Electrophilic Spirocyclization Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 3236–3239. 10.1021/jo00274a061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Under modified conditions we were able to isolate the bis-oxa-adamantane intermediate (18c) as a minor product.

- Stereochemistry was corroborated by low-quality X-ray crystal (see Supporting Information).

- Blaszczak L. C.; Brown R. F.; Cook G. K.; Hornback W. J.; Indelicato J. M.; Jordan C. L.; Katner A. S.; Kinnick M. D.; Mcdonald J. H. Comparative Reactivity of 1-Carba-1-dethiacephalosporins with Cephalosporins. J. Med. Chem. 1990, 33, 1656–1662. 10.1021/jm00168a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X. T.; You L.; Li Y. H.; Yu H. X.; Chen J. H.; Yang Z. Asymmetric Total Synthesis of Propindilactone G, Part 3: The Final Phase and Completion of the Synthesis. Chem. Asian J. 2016, 11, 1425–1435. 10.1002/asia.201600131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- This route was initially explored with racemic material (see Supporting Information).

- Nagumo S.; Miura T.; Mizukami M.; Miyoshi I.; Imai M.; Kawahara N.; Akita H. Intramolecular Friedel-Crafts type reaction of vinyloxiranes linked to an ester group. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 9884–9896. 10.1016/j.tet.2009.09.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.