Abstract

Purpose:

Appalachian residents have higher cancer prevalence and invasive cancer incidence in almost all cancer types relative to non-Appalachian residents. Public health interventions have been carried out to increase preventive cancer screening participation. However, no studies have evaluated the effectiveness of existing interventions targeting cancer screening uptake in this high-risk population. The main objective of this study is to assess the effectiveness of interventions aimed at increasing uptake and/or continuing participation in screened cancers (breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate) in Appalachia.

Methods:

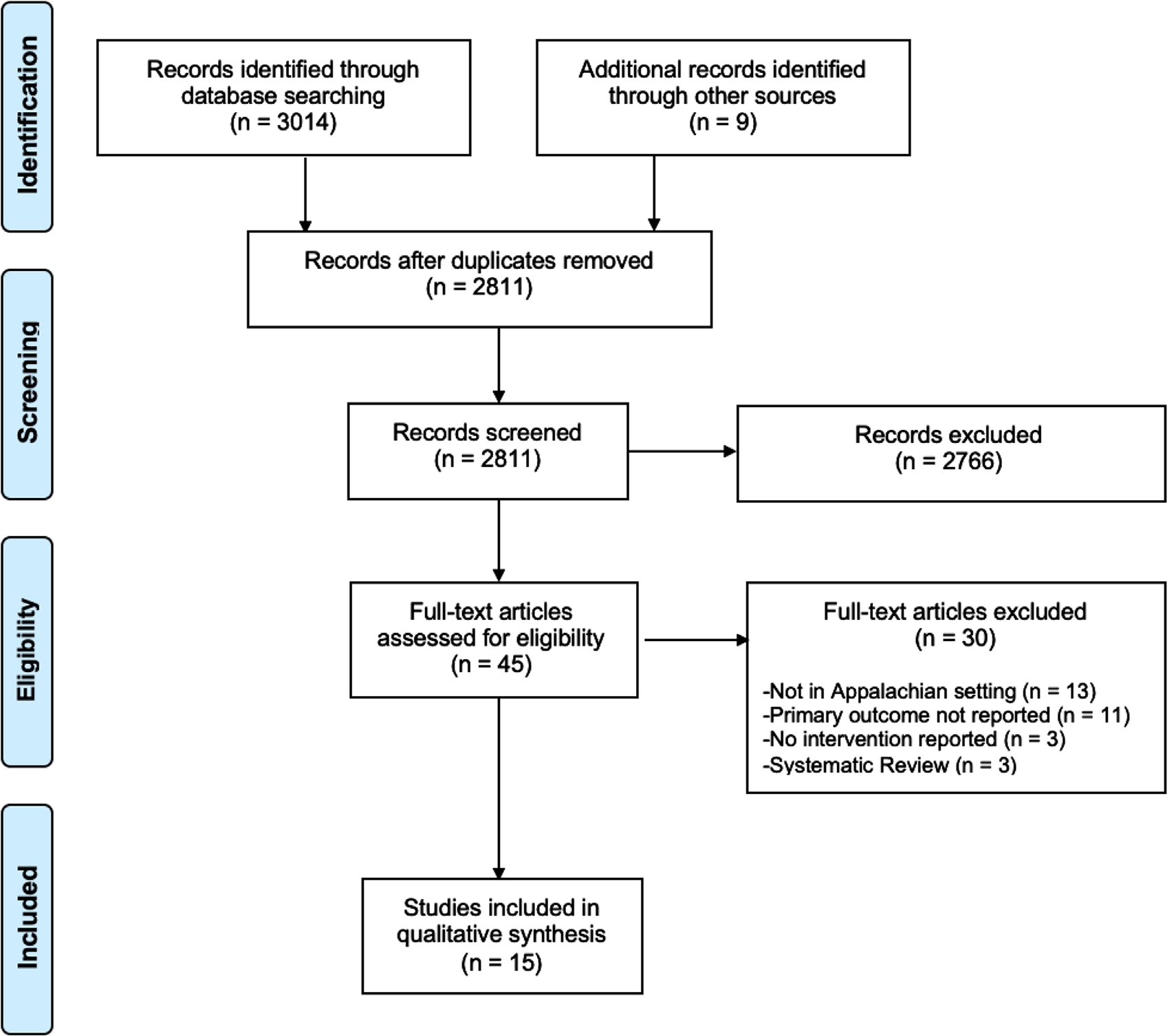

We conducted a systematic review of electronic databases and gray literature using a combination of MeSH and free-text search terms related to breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer; mass screening; health promotion; and Appalachia. We identified 3,014 articles of which 15 articles were included. We assessed methodological quality using validated tools and analyzed findings using narrative synthesis.

Findings:

Fifteen studies reported uptake and/or continued participation in screening interventions; these focused on cervical (n = 7), colorectal (n = 5), breast (n = 2), and lung (n = 1) cancers in Appalachia. Interventions included diverse components: mass media campaigns, community outreach events, community health workers, interpersonal counseling, and educational materials. We found that multi-strategy interventions had higher screening uptake relative to interventions employing 1 intervention strategy. Studies that targeted noncompliant populations and leveraged existing community-based organization partnerships had a substantial increase in screening participation versus others.

Conclusions:

There is an urgent need for further research and implementation of effective cancer prevention and screening interventions to reduce disparities in cancer morbidity and mortality in Appalachian populations.

Keywords: Appalachia, cancer screening, health promotion, intervention, secondary prevention

High cancer incidence and mortality rates are concentrated in the Appalachian region of the United States. While the United States has seen cancer mortality rates reduced by 20% from 1991 to 2010, the Appalachian region of the United States has not seen these drastic reductions in cancer mortality rates.1,2 The Appalachian region of the Eastern United States includes rural regions of 13 states from New York to Mississippi surrounding the Appalachian Mountains. Forty-two percent of Appalachia is classified as rural. This is substantially higher than the total US population at 20% rurality.3 There are 25 million people residing in this impoverished region, and the region suffers from historically high unemployment rates, low educational attainment, low health-seeking behaviors, and poor health outcomes.5,6

Disparities in cancer incidence and mortality exist in all cancer types between Appalachian residents and non-Appalachian residents.2 Mortality rates in rural Appalachian counties range from 166.3 deaths per 100,000 people to 231.5 deaths per 100,000 people in Kentucky, which was up to 36% higher compared to their urban non-Appalachian counterparts.2 In Kentucky, the age-adjusted cancer mortality rate for all cancer sites is 223.4 deaths per 100,000 people in Appalachian residents and 187.6 deaths per 100,000 people in non-Appalachian residents from 2012 to 2016.7 Appalachian residents have a higher cancer prevalence and invasive cancer incidence in almost all cancer types regardless of sex or race/ethnicity when compared to non-Appalachian residents.8 Cancer disparities in Appalachian populations have been attributed to a complex interplay of rising rates of obesity, tobacco use, alcohol and substance abuse, low educational attainment, lack of access to health care services, and exposure to environmental risk factors such as coal mining and water pollution.9

To detect and identify cancer at earlier stages, the American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends routine, preventative screenings for breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer at specified times throughout an individual’s life as detailed in Table 1.10 In Appalachia, a unique interplay of cancer screening barriers includes distrust in the health care system, low health literacy, geographic isolation, societal beliefs, and a fatalistic view of cancer.11–14 These barriers perpetuate a lower screening uptake, defined by the proportion of a population that engages with a screening program after being introduced to it, in Appalachia compared to urban and non-Appalachian residents.15 As a result, public health professionals and organizations have implemented diverse health promotion interventions such as educational sessions, mobile health interventions, and lay health worker counseling. Despite these efforts, the burden of cancer in Appalachia remains almost unchanged since the 1960s.2 Understanding the effectiveness of the wide range of public health interventions targeting cancer screening in Appalachia in terms of uptake of breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer screening may lead to more effective interventions and detection of cancer at earlier stages.

Table 1.

PICOS Framework for Included Studies Relating to the Review Question

| Criteria | Determinants |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Population | |

| - Participants over 18 years of age | |

| - Appalachian residents as defined by the Appalachian Regional Commission’s list of Appalachian counties | |

| - Participants eligible for annual cancer screening according to cancer type10: | |

| • Breast cancer: females 40–54 years screened every year and after 55 years yearly or every 2 years | |

| • Cervical cancer: females 21–65 years screened every 3 years | |

| • Colorectal cancer: males and females above 45 years screened every 10 years | |

| • Lung cancer: males and females 55–74 years screened every year if they are | |

| ○ Individuals that currently smoke or quit within the past 15 years | |

| ○ Individuals with at least 30-pack-year smoking history | |

| • Prostate screening: males above 50 years, screening frequency varies | |

| Intervention | Interventions (behavioral intervention and/or health promotion and/or education intervention) carried out in Appalachia |

| Comparison | Studies with and without a control group |

| Outcomes | Primary: proportion/percent of uptake and/or the continuing participation of cervical, breast, prostate, lung, and/or colorectal cancer screening |

| Secondary: barriers and facilitators to screening, willingness to screen, cancer knowledge, acceptability of screening procedure or program, and access to cancer screening programs or services | |

| Study design | Randomized controlled trials, quasi-experiments, observational (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional), and mixed-methods studies |

Systematic reviews have been previously published on health promotion interventions for cancer screening in the United States, but Appalachian residents make up a minority of participants in these studies. No readily identifiable systematic reviews exist in the medical literature, which evaluate cancer screening uptake in this vulnerable population. The objective of this systematic review is to assess the effectiveness of interventions aimed at increasing uptake and/or continuing participation in screened cancers (breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate) among Appalachian residents.

Methods

Data Sources and Searches

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) to guide the development and reporting of this review.16 An electronic search was carried out using MEDLINE, Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Psychological Information Database (PsycINFO), Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. We also searched the Web of Science Core Collection for gray literature. There were no language or date restrictions. Search terms related to breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer; secondary prevention; mass screening; early diagnosis; health promotion; intervention; and Appalachia. The base search strategy in MEDLINE is reported in Table S1. We developed and combined database-specific thesaurus terms, such as Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms, and free text terms. We translated this search strategy into the other databases using appropriate, applicable controlled vocabulary for each database. We identified additional literature by hand searching reference lists of screened studies.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We specified the eligibility criteria of included studies by the PICOS (Problem or Population, Interventions, Comparisons, Outcomes, and Study design) framework as summarized in Table 1.17 We limited our review to studies that included participants that met our criteria: Appalachian residents (according to the Appalachian Regional Commission’s list of Appalachian counties) who were eligible for respective cancer screening according to the 2019 ACS guidelines (Table 1). The intervention of interest was health promotion interventions related to cancer screening including strategies such as behavioral interventions, health education, media campaigns, decision aids, community events, and screening fairs set in Appalachia. Included interventions aimed to satisfy our primary outcome: uptake and/or the continuing participation of breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and/or prostate cancer screening, which was defined as the proportion of a population that engages with a screening program after being introduced to it. If available, we evaluated secondary outcome(s) including barriers and facilitators to screening, willingness to screen, cancer knowledge, acceptability of screening procedure or program, and access to cancer screening programs or services. We included a diverse range of study designs such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional), quasi-experimental, and mixed-methods studies. Qualitative study designs were excluded. For studies that included other cancer types or other diseases, or included Appalachian and non-Appalachian residents, we extracted results for breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer and Appalachian residents, respectively, contacting the corresponding author via email as needed. We excluded studies with participants that did not satisfy respective cancer screening guidelines (Table 1).

Study Selection

We ran the search strategy on all selected electronic databases and stored and managed identified study titles and abstracts in EndNote X8.2. After duplicates were removed, 2 reviewers (NR, LH) independently screened the remaining titles and abstracts using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. For these studies, the 2 reviewers (NR, LH) independently screened the full-text articles with detailed reasons for exclusion recorded. At each stage, disagreements between reviewers were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, a third reviewer resolved disagreements.

Synthesis of Results and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (NR, LH) independently extracted the data from included studies, using created data extraction forms with differences between reviewers resolved by discussion. We requested missing data from studies’ corresponding authors by email as needed. To evaluate the quality of studies we utilized validated quality appraisal tools (Table 2). The Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) evaluated the quality of quantitative and mixed-methods studies, respectively (Table 2).18,19 We scored all included studies for bias according to the quality assessment tool’s guidelines. Due to the heterogeneity of study designs (experimental and observational), study populations, and interventions, we utilized a narrative synthesis approach to analysis rather than a meta-analysis. According to Popay and colleagues’ framework, we conducted a narrative synthesis of included studies and analyzed findings relative to our outcomes and significance of the findings for future practice and research.20

Table 2.

Quality Assessment Tools for Each Study Design

| Tools | Study Design |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP): Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies | Randomized controlled trials |

| Cohort studies | |

| Case-control studies | |

| Cross-sectional studies | |

| Interrupted time series studies | |

| Quasi-experiments | |

| Other nonrandomized intervention studies | |

| Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) | Mixed-methods studies |

Results

Electronic database and gray literature search yielded 3,014 articles. An additional 9 articles were identified through hand searching. After removal of duplicates (n = 212), both reviewers (NR, LH) screened the titles and abstracts of 2,811 articles and excluded 2,766 articles. We then assessed 45 full-text articles from which a further 30 were excluded due to non-Appalachian setting, unreported cancer screening participation, lack of intervention, or systematic review study design. We ultimately included 15 studies in this review (Figure 1 and Table 3). Included studies were published in English from 1989 to 2020 and dealt with populations of Appalachian regions in Kentucky (n = 6), Pennsylvania (n = 4), Ohio (n = 3), and North Carolina (n = 2). The majority of studies consisted of exclusively rural Appalachian participants; 2 studies did not. Dignan and associates included 95.1% urban/suburban participants and Michielutte and colleagues included 91.5% urban/suburban participants. Included studies reported interventions to improve cervical (n = 7), colorectal (n = 5), breast (n = 2), and lung (n = 1) cancer screening uptake and/or continued participation.21,22 No studies described prostate cancer screening interventions. Effectiveness of cancer screening interventions was measured by the proportion of study participants who were presented with a screening opportunity who eventually participated in screening as described in Figures 2–4. Various screening modalities were reported: Pap testing and HPV self-testing for cervical cancer; colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, home-based fecal immunochemical test (FIT), and fecal occult blood test (FOBT) for colorectal cancer (CRC); mammography for breast cancer; and low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) for lung cancer.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram for Cancer Screening Articles Selection and Evaluation.16

Table 3.

Summary of Included Studies

| Study (Author, Publication Year) | Setting | Study Design and Data Collection Dates | Study Population | Intervention | Screening Modality | Primary Outcome: Proportion/Percent of Uptake and/or the Continuing Participation of Cancer Screening | Secondary Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Cervical cancer | |||||||

| Reiter et al, 201935 | Ohio* | Randomized controlled trial 2015–2016 |

103 women 30–65 years with no Pap test in the last 3 years in an Ohio Appalachia county | This intervention had 2 components: (a) specific HPV self-testing instructions with larger text, pictures and simplified language and (b) a photo story brochure containing Information on HPV, cervical cancer, and cervical cancer screening. The photo story is a style of entertainment-education that told a story about women discussing cervical cancer screening. | HPV self-testing |

There was 78% (n = 80) uptake of HPV self-testing in intervention vs 77% (n = 79) in control group (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 0.43 to 2.76) | Facilitators: interest in current health status, HPV diagnosis, and convenience. Barriers: lack of priority, fear of pain and incorrect use, lack of pain as symptom, and fear of HPV diagnosis. |

| Collins et al, 201526 | Kentucky | Cross-sectional reporting pre- and post-intervention results 2011–2014 |

317 women aged 18–65 years, eligible to receive health department services, and self-report of never receiving a Pap test or within the past 3 years | This community-based intervention consisted of Women’s Health Day events in which health department staff provided education and recruited incompliant women to receive a pap test with results mailed to each participant. | Pap test | 0% participants compliant with Pap test guidelines (rarely or never screened) pre-intervention and 99% (n =314) uptake of Pap test post-intervention | Facilitators: referral by provider/health dept., experience symptoms, perceive need of screening Barriers: cost, lack of perceived need for screening, and lack of transportation |

| Vanderpool et al, 201429 | Kentucky | Pre- and post-intervention study Nov 2011-Jan 2012 |

31 women 30–64 years attending free primary care clinic and not having a Pap test in the past 4 years | Primary-care-based intervention in which women were offered HPV self-testing to screen for HPV and thus cervical cancer. Nurses counseled women on the importance of receiving routine, guideline-appropriate cervical cancer screening according to current recommendations. Nurse-navigators provided help scheduling Pap tests at local health departments and assistance with transportation, childcare, and personal support as needed. | HPV self-testing |

90.3% (n = 28) participants ever reported cervical cancer screening pre-intervention and 100% (n = 31) reported HPV self-testing intervention post-intervention | 100% acceptance of HPV self-testing procedure Facilitators and barriers: None reported |

| Studts et al, 201228 | Kentucky** | Randomized controlled trial Dec 2005-June 2008 |

345 women 40–64 years attending Appalachian church with no Pap test in the last 12 months | Local lay health advisors (LHAs) from community churches conducted home-visits and prepared newsletters addressing individualized counseling addressing community member barriers to Pap testing. LHAs also educated women on cervical cancer and Pap tests at 2-hour home-visits. | Pap test | At baseline 0% participants in intervention and control groups had a Pap test within the past 1 year; after study follow-up (post-intervention for treatment group) 18% (n = 31) in intervention group and 11% (n = 19) in control group had a Pap test within the past 1 year. Compared to participants in the control arm, participants in the intervention arm had 2.56 increased odds of receiving a Pap test (95% CI: 1.03 to 6.38, P = .04). | Facilitators: prior Pap test participation Barriers: None reported |

| Paskett et al, 20119 | Ohio | Randomized controlled trial March 2005-Feb 2008 |

270 women over 18 years at an Appalachian clinic in need of a Pap test | Local Appalachian women 40–50 years were trained as LHAs. LHAs conducted 2 in-person visits, 2 telephone calls, and 4 postcards to community members over a 10-month period. LHAs visited women at their homes or community locations for 45–60 minutes providing educational information surrounding cervical cancer, Pap test screening, and the importance of follow-up after an abnormal test. individualized counseling surrounding cervical cancer knowledge and barriers were addressed. | Pap test | After follow-up (post-intervention) 51.1% (n = 71) participants in intervention group and 42.0% (n = 55) in control group had a Pap test within the last 12 months, which was not a statistically significant difference (OR = 1.44, 95% CI: 0.89 to 2.33; P = .135). | Facilitators and barriers: None reported |

| Dignan et al, 199421 | Forsyth County, North Carolina | Pre- and post-intervention Nov 1988-Sept 1991 |

474 Black women over 18 years of age within Forsyth county | This intervention had 2 components: (a) mass media- public service announcements on TV, radio, posters, pamphlets, leaflets, newsletters, and promotional items. (b) direct education-interactive group workshop on cervical cancer prevention and offered question and answer sessions. |

Pap test | In Forsyth County, pre-intervention 70.2% (n = 315) participants had a Pap test in the past year and post-intervention 75.1% (n = 311) participants had a Pap test in the past year, which was not statistically significant (P = .761) | Cervical cancer knowledge ranged from a decrease of 5.5% to an increase of 7.4% from pretest to posttest due to the intervention Facilitators and barriers: None reported |

| Michielutte et al, 198922 | Forsyth County, North Carolina | Pre-and post-intervention study Nov 1988–1991 |

474 Black women over 18 years of age with 94 participants reporting the primary outcome | This intervention had 3 components: (a) media campaign of print and broadcast materials about uterine health; (b) workshop with brief presentation on uterine health with time for questions; and (c) educating primary care physicians on educational information about cervical cancer and screening | Pap test | In Forsyth County, pre-intervention 69.1% (n = 65) and post-intervention 69.8% (n = 66) had a Pap test in the past year | At baseline 25% participants had some degree of Pap test knowledge; Cervical cancer awareness increased from 26.8% at baseline to 46.6% post-intervention. Facilitators and barriers: None reported |

| Colorectal cancer | |||||||

| Key et al, 202024 | Kentucky | Mixed-methods Data collection dates not reported |

56 community members over 50 years with noncompliance with current colorectal cancer (CRC) screening guidelines and at least one modifiable colorectal cancer risk factor | Social media campaign using evidence-based Facebook posts targeting modifiable CRC risk factors. Topics included nutrition, physical activity, CRC susceptibility, family history and CRC risk, screening experience, and community and financial screening resources. A private Facebook group (#CRC-Free) had 3 daily posts and community members were asked to view the page daily for the 12-week study period. | Colonoscopy | Pre-intervention 14% (n = 8) participants had a colonoscopy and post-intervention 17.9% (n = 10) participants had a colonoscopy. | Facilitators and barriers: None reported |

| Crosby et al, 201727 | Kentucky | Pre- and post-intervention study Data collection dates not reported |

345 community members 50–75 years incompliant with current CRC screening guidelines | Community outreach events provided direct referrals for CRC screening at local health departments and explained the fecal immunochemical test’s (FIT) use. Additionally, outreach was conducted at Appalachian senior citizen centers and health and wellness events. | Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) | Pre-intervention 0% participants were compliant with CRC screening guidelines and post-intervention 82.0% (n = 283) participants completed the FIT | Facilitators and barriers: None reported |

| Krok-Schoen et al, 201525 | Ohio | Randomized controlled trial 2006–2011 |

1,123 men and women aged 51–75 years that were resident of one of the 12 Ohio Appalachian counties with no prior history of Invasive CRC and no strong CRC history | “Get Behind Your Health! Talk to Your Doctor About Colon Cancer Screening” intervention is a culturally sensitive media campaign to increase CRC screening. Three intervention strategies were tested: (a) media campaign addressing perceived barriers and facilitators of screening (b) clinic intervention utilizing clinic-based reminders of educational posters and brochures and (c) both the media and clinic components (a and b) | Colonoscopy or Sigmoidoscopy | At baseline (2006) 55.3% participants had ever screened for CRC in intervention vs 56.2% in control groups. After follow-up in 2011 (post-intervention for intervention group) 70.3% had ever screened for CRC in intervention vs 60.6% in control groups | Facilitators: perceived CRC risk, physician screening recommendation, and willingness to screen; Barriers: None reported 85.1% and 81.9% participants reported willingness to have CRC screening in intervention and control counties, respectively, |

| Kluhsman et al, 201232 | Pennsylvania | Cohort study 2008–2009 |

232 patients over 50 years and not in compliance with CRC screening guidelines | Patients approached in clinical settings and received a free take-home FIT and the American Cancer Society brochure outlining how to prevent colon cancer. Telephone counseling was provided to patients that were nonadherent after receiving the FIT. Telephone counseling consisted of client-centered problem-solving techniques to address patient barriers. | Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) | Pre-intervention 72.5% (n = 145) participants had completed the FIT and post-intervention 84% (n = 168) participants completed the FIT | Facilitators: None reported Barriers: lack of CRC knowledge, lack of perceived risk, uncomfortable, inconvenient, low literacy, and cost |

| Curry et al, 201133 | Pennsylvania | Pre- and post-intervention study Feb 2008-Jan 2009 |

323 Appalachia primary care patients 50 years or older | Community-based coalition ACTION Health Cancer Task Force and Penn State Ambulatory Care Research Network partnership in primary care setting disseminating screening tools and patient education materials | Fecal occult blood test (FOBT), FIT, flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS), colonoscopy |

Pre-intervention 17% (n = 56) participants had a CRC screening In the past year and post-intervention 35% (n = 106) participants had a CRC screening in the past year (P <.001) | Facilitators: CRC screening recommendation Barriers: None reported |

| Breast cancer | |||||||

| Gallant et al, 201334 | Pennsylvania | Pre- and post-intervention study Sept-Dec 2010 |

139 Appalachian women over 40 years of age with 69 women reporting the breast cancer screening uptake | Generated fact sheets from the Strong Women program and Susan G. Komen for the Cure were used as educational aids covering topics such as Breast cancer prevention, early detection, and survivorship. Weekly classes were hosted and fact sheets addressed ways to reduce breast cancer risk such as dietary changes and exercise. One or 2 fact sheets were discussed each week at the beginning of class. |

Mammogram | Pre-intervention 94.1% (n = 64) participants had yearly screening mammograms and post-intervention 98.6% (n = 68) participants had yearly screening mammograms | Facilitators and barriers: None reported |

| Bendvenga et al, 200831 | Indiana County, Pennsylvania | Cross-sectional reporting pre- and post-intervention results Feb-June 2005 |

302 women aged 40+ years receiving food from Indiana County Community Action Program | Indiana County Cancer Community Action Program low-cost food outreach program implemented the American Cancer Society Tell a Friend campaign consisting of reminders and one-on-one peer counseling to recommend mammograms | Mammogram | Pre-intervention 47.7% (n = 144) participants were compliant with mammogram guidelines and post-intervention 93.4% (n = 282) participants were compliant with mammogram guidelines | Facilitators and barriers: None reported |

| Lung cancer | |||||||

| Cardarelli et al, 201723 | Kentucky*** | Mixed Methods Oct 2014-March 2015 |

145 men and women 55–77 years old with at least 30 pack-years of smoking | Mail postcards to clinical and community providers with low-dose CT (LDCT) guidelines and a physician roundtable describing LDCT screening. Internet resources were provided to community members. A media campaign consisted of ads ran every 2 weeks and on radio twice daily for 6 months. | LDCT scan | Pre-intervention no (0%) participants had a lung cancer screening and post-intervention 3.4% (n = 5) participants had a lung cancer screening. | 6.9% (10/145) of participants reported increased willingness and contemplation to receive LDCT scan due to the intervention Facilitators and barriers: None reported |

Adams, Jackson, Pike, Scioto counties.

Harlan, Knott, Letcher, Perry counties.

Pike, Letcher, Floyd, Martin, Perry, Knott, Harlan, Leslie, Breathitt, Clay, Owsley, Rowan, Fleming, Lewis, Carter, Elliott, Morgan, Menifee, and Bath counties.

Abbreviations: HPV, human papillomavirus; LHA, lay health advisors; CRC, colorectal cancer; FOBT, fecal occult blood test; FIT, fecal immunochemical test; FS, flexible sigmoidoscopy; LDCT, low-dose computed tomography.

Figure 2.

Included Studies (n = 7) Describing Proportion of Screening Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening Interventions.

Figure 4.

Included Studies (n = 2) Describing Proportion of Screening Uptake of Breast Cancer Screening Interventions.

Primary Outcome by Intervention Strategy

The primary outcome of uptake and/or continued participation in cancer screening is reported by intervention strategy category as mass media campaigns, community outreach events, community health workers, interpersonal counseling, and educational materials (Table 4).

Table 4.

Intervention Component Characteristics of Included Studies

| Study (Author, Year) | Mass media campaign | Community outreach events | Community health workers | Interpersonal counseling | Educational materials | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Cervical | Reiter et al, 2019 | X | ||||

| Collins et al, 2015 | X | |||||

| Vanderpool et al, 2014 | X | X | ||||

| Studts et al, 2012 | X | X | ||||

| Paskett et al, 2011 | X | X | X | |||

| Dignan et al, 1994 | X | X | ||||

| Michielutte et al, 1989 | X | X | X | |||

| Colorectal | Key et al, 2020 | X | ||||

| Crosby et al, 2017 | X | |||||

| Krok-Schoen et al, 2015 | X | X | ||||

| Kluhsman et al, 2012 | X | X | ||||

| Curry et al, 2011 | X | |||||

| Breast | Gallant et al, 2013 | X | ||||

| Bencivenga et al, 2008 | X | |||||

| Lung | Cardarelli et al, 2017 | X | X | |||

Mass Media Campaigns

Five studies described the use of community-targeted mass media campaigns including radio, TV, print (newspapers and flyers), and social media for breast, cervical, colorectal, and lung cancer screening.21–25 Key and associates utilized the social media intervention #CR-CFREE and demonstrated 17.9% (n = 10) uptake of colonoscopy post-intervention relative to 14% (n = 8) pre-intervention.24 Krok-Schoen and colleagues implemented a culturally sensitive print mass media campaign using billboards, posters, and newspapers and found a 15% increase in CRC “ever” screening uptake (55.3% pre-intervention vs 70.3% post-intervention) with a multicomponent approach.25 Interventions that used a combination of broadcast and print mass media were minimally effective in increasing cancer screening uptake.21–23

Community Outreach Events

Three studies reported community outreach events including 1-day events and community workshops focused on cervical cancer and CRC screening.22,26,27 Among cervical cancer screening interventions, Collins and associates used Women’s Health Day events to identify “never” cervical cancer screeners and educate women on the importance of screening.26 This substantially increased Pap testing from 0% at baseline to 99% (n = 314) post-intervention. However, Michielutte and colleagues’ intervention using a group question and answer workshop on reproductive health was less effective in Forsyth County, North Carolina; they noted 69.1% (n = 65) and 69.8% (n = 66) Pap test uptake pre-intervention versus post-intervention, respectively.22 Similar to Collins and associates, Crosby and colleagues used community outreach events targeting unscreened populations specifically at senior citizen centers and health events to increase CRC screening in community members noncompliant to current CRC guidelines.26,27 This increased CRC screening compliance and participation in FIT completion by 82% (0% baseline vs 82% post-intervention, n = 283).

Community Health Workers

Three studies investigated the use of community health workers (CHWs) to educate and counsel community members one-on-one to increase uptake of cervical cancer.9,28,29 CHWs included local lay health advisors (LHAs) and nurse navigators. The study by Vanderpool and associates was the only primary care-based CHW intervention utilizing nurse navigators to counsel women on cervical cancer screening and address barriers to screening such as cost and transportation.29 This study reported high baseline uptake of cervical cancer screening (90.3%, n = 28), leading to an increase of 9.3% (n = 3) from baseline with use of HPV self-sampling. Two RCTs assessed community-based interventions utilizing LHAs to provide individualized counseling on cervical cancer screening.9,28 LHAs are respected and trusted community members with limited medical training that often provide guidance and support in their social networks.30 Studts and colleagues leveraged LHAs within a faith-based infrastructure in Kentucky to conduct home visits and provide one-on-one counseling through personalized newsletters.28 At baseline, no participants in the intervention and control groups had a Pap test within the past year; after follow-up 18% (n = 31) in the intervention and 11% (n = 19) in the control group had a Pap test within the past year.28 Compared to participants in the control arm, participants in the intervention arm had 2.56 increased odds of receiving a Pap test (95% CI: 1.03–6.38, P = .04). Paskett and associates described the use of LHAs to conduct educational home visits and individualized counseling on cervical cancer.9 Their intervention showed higher Pap test in the intervention group (51.1%, n = 71) relative to the control group (42.0%, n = 55) 12 months post-intervention (OR = 1.44, 95%CI: 0.89–2.33; P = .135).9

Interpersonal Counseling

Five studies described interpersonal counseling components primarily consisting of telephone counseling for CRC screening, peer counseling for breast cancer screening, and CHW-delivered interpersonal counseling for cervical cancer screening.9,28,29,31,32 Bencivenga and associates performed a cross-sectional study utilizing a one-on-one peer counseling program that recommended mammograms to 302 women over 40 years old who were identified due to prior participation in the Indiana County Cancer Community Action Program food outreach program.31 Pre-intervention, 47.7% (n = 144) versus post-intervention, 93.4% (n = 282) of participants were compliant with mammogram guidelines, which suggests the counseling was highly effective. Kluhsman and colleagues designed a cohort study that provided fecal immunochemical testing and subsequent telephone counseling to 232 participants aged over 50 years and nonadherent to CRC screening to address potential participant barriers.32 This face-to-face intervention was moderately successful with FIT uptake and completion increasing 11.5% (72.5% pre-intervention vs 84% post-intervention).

Educational Materials

Nine studies had educational material components consisting of print educational materials, group workshop presentations, educating physicians to counsel patients, and Internet educational resources.9,21–23,25,32–35 Reiter and associates used a picture-based instructional manual and a photo story brochure to facilitate cervical cancer and screening knowledge as the sole intervention strategy.35 There was no increase in HPV self-testing uptake as a result of intervention with 78% (n = 80) in intervention and 77% (n = 79) in control group (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 0.43–2.76). However, other cervical cancer screening interventions using print educational materials have coupled additional interventions with some effectiveness: CHW visits yielded a 9.1% (n = 16) increase in uptake in Pap test, mass media campaign a 4.9% (n = 4) increase in uptake in Pap test, and workshops and mass media campaign a 0.7% (n = 1) increase in Pap test uptake.9,21,22

CRC screening interventions used multicomponent strategies. Included studies in clinical settings showed that dissemination of print educational materials in primary care settings increased CRC screening uptake in the past year by 18% (n = 50) (P < .001),33 while supplementing print-based educational materials with a mass media campaign and clinic-based reminders increased CRC screening by 15%.25 Similarly, patients approached in primary care settings with educational brochures and follow-up peer telephone counseling increased modestly in FIT completion (72.5% [n = 145] pre-intervention vs 84.0% [n = 168] post-intervention).32

For breast cancer screening interventions, Gallant and colleagues found the use of print educational aids, such as fact sheets, had a minimal 4.5% (n = 4) increase in uptake of yearly mammograms.34 Likewise, a lung cancer screening intervention using Internet educational resources was minimally effective with a 3.4% (n = 5) increase of LDCT among a “never” screened population.23

Secondary Outcomes

A subset of included studies reported on the following secondary outcomes: facilitators and barriers to screening; acceptability of screening; level of baseline and post-intervention cancer knowledge and awareness; and willingness to undergo cervical, colorectal, and lung cancer screening. Cervical cancer screening studies reported on cervical cancer knowledge, awareness, acceptability, facilitators, and barriers to cervical cancer screening.21,22,26,28,29,35 Cervical cancer awareness among participants increased from 26.8% at baseline to 46.6% following an intervention consisting of 3 components: a media campaign, workshop on reproductive health, and educational intervention to primary care providers.22 However, there was no consistent change in cervical cancer knowledge following a coupled mass media and educational intervention.21 All (n = 31) participants reported that HPV self-testing was an acceptable procedure.29 Facilitators to cervical cancer screening included prior screening participation, referral by health professional, experiencing positive symptoms, perceived need of screening, prior HPV diagnosis, convenience, and interest in health status.26,28,35 Barriers to cervical cancer screening included cost, lack of perceived need for screening, lack of transportation, lack of priority, fear of pain with incorrect HPV self-test use, lack of positive symptoms (pain), and fear of HPV diagnosis.26,35

CRC screening studies reported on willingness, facilitators, and barriers to colorectal cancer screening.25,32,33 After an intervention utilizing a culturally sensitive media campaign, clinic-based reminders, and print educational materials, 85.2% of participants were willing to screen for CRC.25 Facilitators to CRC screening included perceived CRC risk and screening recommendation25,33 Barriers to CRC screening included lack of CRC knowledge, lack of perceived risk, low literacy, high cost, inconvenience, and discomfort during screening.32 In a lung cancer screening study, willingness to receive LDCT was reported in 6.9% (n = 10) of participants as a result of the intervention.23

Quality Assessment

We performed quality assessment based on quantitative (n = 13) or mixed-method study (n = 2) design. The EPHPP tool assessed RCTs, observational studies, pre- and post-intervention studies, and other non-randomized studies (Table 5). Among our included quantitative studies (n = 13), many (n = 5) were “weak” quality. Three studies were “moderate” and 5 studies were “strong” (n = 5) quality. Many studies had substantial selection bias due to participant recruitment from primary care practices and clinic-based registries. Some studies that reported mass media campaign intervention components were limited by small sample sizes and study designs to measure population-level cancer screening uptake outcomes. Additionally, some studies did not discuss statistical methods for addressing confounding or blinding of assessors in RCTs and quasi-experimental study designs. Few studies reported statistical significance and P values of screening uptake between study groups. Using the MMAT for 2 studies, we found that the mixed-methods studies were high quality with limited selection bias, and participants were representative of the target population.23,24 In the mixed-methods studies, qualitative and quantitative data collection and findings were effectively integrated and justified to address the research question.

Table 5.

Quality Assessment of Quantitative Studies Using the EPHPP Tools (n = 13)

| Study (Author, Year) | Selection bias | Study design | Confounders | Blinding | Data collection methods | Withdrawals and drop-outs | Global rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Bencivenga et al, 2008 | |||||||

| Collins et al, 2015 | |||||||

| Crosby et al, 2017 | |||||||

| Curry et al, 2011 | |||||||

| Dignan et al, 1994 | |||||||

| Gallant et al, 2013 | |||||||

| Kluhsmna et al, 2012 | |||||||

| Krok-Schoen et al, 2015 | |||||||

| Michielutte et al, 1989 | |||||||

| Paskett et al, 2011 | |||||||

| Reiter et al, 2019 | |||||||

| Riehman et al, 2017 | |||||||

| Studts et al, 2012 | |||||||

| Vanderpool et al, 2014 | |||||||

Quality Assessment Ratings: green, strong; yellow, moderate; red, weak; gray, not applicable.

Note: While this systematic review included 15 studies, 13 of these studies were quantitative studies, so quality was assessed using the EPHPP tool. The remaining 2 studies were assessed using the mixed-methods assessment tool with results reported above.

Discussion

This systematic review reports on the uptake and/or continued participation in common cancer screenings of 15 intervention studies based in Appalachian regions. Based on the combined results of these studies, we found that effective interventions targeted populations that were primarily never screened, included multiple intervention components, and leveraged existing connections within the community. Appalachian populations are more at risk for developing and dying from cancer, but it is increasingly common for impoverished, rural populations to have low knowledge about cancer prevention and little to no prior experience with screening.36–38 Interventions targeting populations with low baseline screening uptake and providing Appalachian participants with educational resources surrounding general cancer knowledge had increased awareness of the importance of cancer screenings.26,27 Therefore, interventions targeting unscreened populations saw great success in increasing screening participation and potentially detecting cancer at earlier, more treatable stages. Additionally, studies that included multi-intervention strategies saw similar improvement in screening participation. Interventions that included multiple components such as print media, clinic-based reminders, and follow-up telephone counseling gave participants multiple opportunities to understand and ask questions about the information presented.25,32,33 The accessibility and replication of cancer-related information that these interventions garnered showed a substantial increase in screening participation. Lastly, studies that utilized existing community organizations such as churches, health departments, and nonprofit organizations also saw a pronounced improvement in screening uptake.26,28,31 This success may reflect increased trust in communications originating from other Appalachian community members.39 Prior research has shown that interventions addressing these personal and cultural barriers for community members increase cancer screening uptake and screening maintenance.11 By including community-based organizations as the cornerstones of the intervention, these studies ensured that information was locally adapted and enhanced the likelihood of participants’ trust in the presented information.

Conversely, interventions that included solely social media campaigns were not effective in Appalachian populations.24 Limited or unreliable Internet access likely reduces the ability for some participants to access these types of interventions.40 In the United States, only 64% of adults over the age of 50 use social media, compared to 78% of adults aged 30–49 and 88% of 18- to 29-year-olds.41 Specifically, in Appalachia, only 51.1% of households have a smartphone with cellular data use.40 This significant difference makes this intervention strategy less effective for cancer screenings more pertinent to older populations, such as CRC screenings. Furthermore, with the changing landscape of mass media technology, mass media interventions reported varying effectiveness. Cervical cancer screening interventions that utilized mass media in the 1980s and 1990s included print media and broadcast media (TV and radio), which were of minimal success in effectiveness of increasing cancer screening participation.21,22 However, despite technological advances in mass media interventions in the last decade, interventions have had minimal success in increasing cancer screening participation in Appalachia.24,27

Few published systematic reviews exist on cancer screening uptake and/or continued participation in the United States, but even fewer exist on rural populations. A 2020 systematic review examined the increase in cancer screening following patient-targeted interventions in rural communities.42 The authors reported that multicomponent interventions as well as nurse-led interventions showed the greatest increase in screening rates. This aligns with our findings regarding multi-strategy interventions. A similar review reporting on the uptake of CRC screenings in African Americans reported that interventions using FOBT demonstrated greater increases in uptake due to its accessibility for rural populations.43 We also noted that interventions and screening modalities that were readily available and accessible for the community saw a substantial increase in screening uptake. Lastly, a systematic review including 22 breast cancer screening intervention studies in rural communities determined that while health promotion interventions boosted breast cancer screening, many of the studies were of low quality.44 We similarly rated 33% (n = 5) of our studies as “weak” quality. For this reason, additional well-designed research is needed in this area in order to implement high-quality and effective interventions.

Our findings are applicable to rural Appalachian communities and are likely generalizable to similar rural communities as they strive to improve early cancer detection rates and reduce cancer-related morbidity and mortality. Although the Appalachian region spans 13 states, we found only 15 studies covering 4 states (Kentucky, North Carolina, Ohio, and Pennsylvania) that reported a change in screening uptake following an intervention. Prioritizing the development and implementation of intervention studies in Appalachia has the potential to further improve cancer screening compliance and early detection. Many of these interventions can be developed based on the strengths and weaknesses of existing studies in similar populations. Because Appalachian communities and other communities like them have unique social, economic, and cultural circumstances, all future interventions should be locally adapted and actively involve local community members during development.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review examining cancer prevention strategies in the Appalachian region of the United States. A strength of this systematic review is the robust methodology by searching multiple electronic databases and gray literature with no date or language restrictions and utilization of Cochrane methodology and PRISMA reporting guidelines to limit selection bias.

A limitation of our study includes the inability to perform a meta-analysis to measure the pooled effectiveness of community interventions due to high heterogeneity of results and study designs. In addition, the amount of included studies available for evaluation was low, likely due to increased likelihood of publishing positive rather than negative results (publication bias), few studies conducted in Appalachia, and underreporting of the results of cancer screening interventions in Appalachia. This is further exemplified by our finding that the 15 identified studies of cancer screening interventions were clustered in 4 of the 13 states in the Appalachia region. Further research is needed to analyze the effectiveness of various community interventions on cancer screening uptake in Appalachian populations, especially in states with Appalachia counties with no identified cancer screening interventions. Therefore, publishing both positive and negative findings and strengthening academic partnerships in the future can strengthen the body of cancer screening literature in Appalachia. This systematic review included 1 study focused on lung cancer and no studies on prostate cancer screening interventions, thus limiting applicability of findings to these cancers. We included observational studies, which were not as robust in their methodology, but this review benefited from the inclusion of observational studies due to the low number of cancer prevention interventions carried out in Appalachia. Additionally, some of the observational studies offered longer follow-up time than RCTs, which was helpful in measuring long-term influence of interventions on cancer screening uptake.

Conclusion

Of the limited available literature, we have demonstrated that interventions with multiple strategies, community-based organization involvement, and targeting unscreened populations were effective in increasing cancer screening uptake and/or continued participation in Appalachia. Few studies focused on breast and lung cancer screening, and no studies focused on prostate cancer. As disparities in cancer screening, morbidity, and mortality between Appalachian and non-Appalachian residents widen, this review further highlights the urgent need for further research and implementation of effective cancer prevention and screening interventions in this vulnerable region.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. MEDLINE Search Strategy

Figure 3.

Included Studies (n = 5) Describing Proportion of Screening Uptake of Colorectal Cancer Screening Interventions.

Funding:

Support for the writing of this manuscript was provided by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, through Grant UL1TR001998, and by the University of Kentucky HealthCare/College of Medicine. Lauren Hudson was supported by a summer research fellowship funded by the University of Kentucky’s Office of the Vice President for Research and the Office of Undergraduate Research, and the University of Kentucky’s Appalachian Center Eller and Billings Student Research Award. Dr. Vanderford is supported by the University of Kentucky’s Cancer Center Support Grant (NCI P30CA177558), the Center for Cancer and Metabolism (NIGMS P20GM121327), and the Appalachian Career Training in Oncology (ACTION) Program (NCI R25CA221765).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemel A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64(1):9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao N, Alcala HE, Anderson R, Balkrishnan R. Cancer disparities in rural Appalachia: incidence, early detection, and survivorship. J Rural Health. 2017;33(4):375–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appalachian Regional Commission. The Appalachian Region. Published 2020. Accessed July 28, 2020. https://www.arc.gov/appalachian_region/TheAppalachianRegion.asp#:∼:text=It%20includes%20all%20of%20West,percent%20of%20the%20national%20population.

- 4.Gohl E. The Appalachian Region. Appalachian Regional Commission, Published 2018. Accessed July 28, 2020. https://www.arc.gov/appalachian_region/theappalachianregion.asp [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lengerich EJ, Tucker TC, Powell RK, et al. Cancer incidence in Kentucky, Pennsylvania and West Virginia: disparities in Appalachia. J Rural Health. 2006;21(1):39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollard K, Jacobsen LA. The Appalachian Region: A Data Overview From the 2006–2010 American Community Survey Chartbook. Washington, DC: Appalachian Regional Commission; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kentucky Cancer Registry. Age-Adjusted Invasive Cancer Incidence Rates in Kentucky Cancer Rates. Published 2016. Accessed July 28, 2020. https://www.cancer-rates.info/ky/

- 8.Wilson RJ, Ryerson AB, Singh SD, King JB. Cancer Incidence in Appalachia, 2004–2011. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(2):250–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paskett ED, McLaughlin JM, Lehman AM, Katz ML, Tatum CM, Oliveri JM. Evaluating the efficacy of lay health advisors for increasing risk-appropriate Pap test screening: a randomized controlled trial among Ohio Appalachian women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(5):835–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Cancer Society (ACS). American Cancer Society Guidelines for the Early Detection of Cancer. Published 2019. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.cancer.org/healthy/find-cancer-early/cancer-screening-guidelines/american-cancer-society-guidelines-for-the-early-detection-of-cancer.html

- 11.Ely GE, White C, Jones K, et al. Cervical cancer screening: exploring Appalachian patients’ barriers to follow-up care. Soc Work Health Care. 2014;53(2):83–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAlearney AS, Oliveri JM, Post DM, et al. Trust and distrust among Appalachian women regarding cervical cancer screening: a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shell R, Tudiver F. Barriers to Cancer screening by rural Appalachian primary care providers. J Rural Health. 2004;20(4):368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanderpool RC, Huang B, Deng Y, et al. Cancer-related beliefs and perceptions in Appalachia: findings from 3 states. J Rural Health. 2019;35(2):176–188. 10.1111/jrh.12359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoenberg NE, Howell BM, Fields N. Community strategies to address cancer disparities in Appalachian Kentucky. Fam Commun Health. 2012;35(1):31–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. System Rev. 2015;4(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(1):12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Souto R, Khanassov V, Hong QN, Bush P, Vedel I, Pluye P. Systematic mixed studies reviews: updating results on the reliability and efficiency of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(1):500–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews a product from the ESRC methods programme. England: Lancaster University; 2006. Accessed July 28, 2020. www.esrc.ac.uk/ESRCInfoCentre/index.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dignan M, Michielutte R, Wells HB, Bahnson J. The Forsyth County Cervical Cancer Prevention Project–I. Cervical cancer screening for black women. Health Educ Res. 1994;9(4):411–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michielutte R, Dignan MB, Wells HB, Young LD, Jackson DS, Sharp PC. Development of a community cancer education program: the Forsyth County, NC cervical cancer prevention project. Public Health Rep. 1989;104(6):542–551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cardarelli R, Reese D, Roper KL, et al. Terminate lung cancer (TLC) study—a mixed-methods population approach to increase lung cancer screening awareness and low-dose computed tomography in Eastern Kentucky. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;46:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Key KV, Adegboyega A, Bush H, Aleshire ME, Contreras OA, Hatcher J. #CRCFREE: using social media to reduce colorectal cancer risk in rural adults. Am J Health Behav. 2020;44(3):353–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krok-Schoen JL, Katz ML, Oliveri JM, et al. A media and clinic intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening in Ohio Appalachia. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:943152. 10.1155/2015/943152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins T, Stradtman LR, Vanderpool RC, Neace DR, Cooper KD. A community-academic partnership to increase Pap testing in Appalachian Kentucky. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2):324–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crosby RA, Stradtman L, Collins T, Vanderpool R. Community-based colorectal cancer screening in a rural population: who returns fecal immunochemical test (FIT) kits? J Rural Health. 2017;33(4):371–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Studts CR, Tarasenko YN, Schoenberg NE, Shelton BJ, Hatcher-Keller J, Dignan MB. A community-based randomized trial of a faith-placed intervention to reduce cervical cancer burden in Appalachia. Prev Med. 2012;54(6):408–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanderpool RC, Jones MG, Stradtman LR, Smith JS, Crosby RA. Self-collecting a cervico-vaginal specimen for cervical cancer screening: an exploratory study of acceptability among medically underserved women in rural Appalachia. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132(Suppl 1):S21–S25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Earp JAL, Viadro CI, Amy A, et al. Lay health advisors: a strategy for getting the word out about breast cancer. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(4):432–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bencivenga M, DeRubis S, Leach P, Lotito L, Shoemaker C, Lengerich EJ. Community partnerships, food pantries, and an evidence-based intervention to increase mammography among rural women. J Rural Health. 2008;24(1):91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kluhsman BC, Lengerich EJ, Fleisher L, et al. A pilot study for using fecal immunochemical testing to increase colorectal cancer screening in Appalachia, 2008–2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curry WJ, Lengerich EJ, Kluhsman BC, et al. Academic detailing to increase colorectal cancer screening by primary care practices in Appalachian Pennsylvania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallant NR, Corbin M, Bencivenga MM, et al. Adaptation of an evidence-based intervention for Appalachian women: new STEPS (Strength Through Education, Physical fitness and Support) for breast health. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(2):275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reiter PL, Shoben AB, McDonough D, et al. Results of a pilot study of a mail-based human papillomavirus self-testing program for underscreened women from Appalachian Ohio. J Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46(3):185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blake KD, Moss JL, Gaysynsky A, Srinivasan S, Croyle RT. Making the case for investment in rural cancer control: an analysis of rural cancer incidence, mortality, and funding trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:992–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mokdad AH, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Fitzmaurice C, et al. Trends and patterns of disparities in cancer mortality among US counties, 1980–2014. JAMA. 2017;317(4):388–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kutner M, Greenburg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The health literacy of America’s adults: results from the 2003 national assessment of adult literacy. National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. Report No. NCES 2006–483. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Behringer B, Friedell G. Appalachia: where place matters in health. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(4):A113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollard K, Jacobsen LA. Appalachia’s Digital Gap in Rural Areas Leaves Some Communities Behind. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith A, Anderson M. Social Media Use in 2018. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; March 1, 2018. Accessed July 28, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/ [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodríguez-Gómez M, Ruiz-Pérez I, Martín-Calderón S, Pastor-Moreno G, Artazcoz L, Escribà-Agüir V. Effectiveness of patient-targeted interventions to increase cancer screening participation in rural areas: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;101:103401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roy S, Dickey S, Wang HL, et al. Systematic review of interventions to increase stool blood colorectal cancer screening in African Americans [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 24]. J Commun Health. 2020;1–13. 10.1007/s10900-020-00867-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agide FD, Sadeghi R, Garmaroudi G, Tigabu BM. A systematic review of health promotion interventions to increase breast cancer screening uptake: from the last 12 years. Eur J Public Health. 2018;28(6):1149–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. MEDLINE Search Strategy