Abstract

Immunization with the merozoite surface glycoprotein gp45 induces protection against challenge using the homologous Babesia bigemina strain. However, gp45 B-cell epitopes are highly polymorphic among B. bigemina strains isolated from different geographical locations within North and South America. The molecular basis for this polymorphism was investigated using the JG-29 biological clone of a Mexico strain of B. bigemina and comparison with the Puerto Rico, St. Croix, and Texcoco strains. The molecular size and antibody reactivity of gp45 expressed by the JG-29 clone were identical to those of the parental Mexico strain. gp45 cDNA and the genomic locus encompassing gp45 were cloned and sequenced from JG-29. The locus sequence and Southern blot data were consistent with a single gp45 copy in the JG-29 genome. The JG-29 cDNA expressed the full-length protein recognized by the gp45-specific monoclonal antibody 14/1.3.2. The genomes of the Puerto Rico and St. Croix strains of B. bigemina were shown to lack a closely related gp45-like gene by PCR using multiple primer sets and by Southern blots using both full-length and region-specific gp45 probes. This genomic difference was confirmed using unpassaged isolates from a 1999 disease outbreak in Puerto Rico. In contrast, the Texcoco strain retains a gp45 gene, encoding an open reading frame identical to that of JG-29. However, the Texcoco gp45 gene is not transcribed. These two mechanisms, lack of a closely related gp45-like gene and failure to transcribe gp45, result in generation of antigenic polymorphism among B. bigemina strains, and the latter mechanism is unique compared to prior mechanisms of antigenic polymorphism identified in babesial parasites.

Babesiosis is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among cattle throughout regions where vector ticks are endemic (1, 7). Recovery from natural infection confers protective immunity against subsequent challenge. However, mortality rates of up to 80% can occur when susceptible adult cattle are imported into areas of endemic babesiosis (1, 10, 15). While attenuated live vaccines afford significant decreases in mortality, their use does not prevent infection, nor does it uniformly confer protection against disease (3, 7, 16, 17, 26, 28). Importantly, the use of these blood-derived live vaccines has been limited by the risk of transmitting contaminating known or unknown pathogens. The development of a safer killed vaccine has focused on babesial antigens that play vital roles in the parasite's invasion of host cells (4, 26).

Babesia-infected ticks inject saliva containing sporozoites into the host bloodstream during feeding. Initial invasion of host cells is followed by sequential rounds of intracellular asexual replication, merozoite development, release, and new invasion (4, 31). With Babesia bigemina and B. bovis, the most prevalent and severe causes of babesiosis in cattle, invasion and multiplication are limited to mature erythrocytes. Although the mechanism of erythrocyte invasion by these two parasites is still incompletely understood, initial attachment has been postulated to involve the merozoite outer membrane glycoproteins MSA-1 and MSA-2 of B. bovis and gp45 and gp55 of B. bigemina (11, 14, 26). Antibody against B. bovis MSA-1 significantly reduces parasitemia in vitro, consistent with the postulated role of MSA-1 in erythrocyte invasion (11). Notably however, MSA-1 and the coexpressed MSA-2 are not antigenically conserved among B. bovis strains isolated from babesiosis-endemic regions worldwide (11, 27, 34).

Recently, the msa-1 genes of several B. bovis strains from the Americas have been identified and characterized (34). MSA-1 antigenic diversity among strains is attributed to genomic polymorphism of a single msa-1 gene, resulting in amino acid substitutions, insertions, and deletions with identity varying from 52 to 98% between individual strains (34). In contrast, B. bovis MSA-2 is encoded by tandemly arranged genes within the variable merozoite surface antigen family (vmsa) (5, 14, 27, 30; C. E. Suarez, M. Florin-Christensen, G. H. Palmer, and T. F. McElwain, unpublished data). The presence of multiple genes may confer on B. bovis the capacity to alter msa-2 expression through genetic recombination within a strain.

In contrast to the well-characterized vmsa family in B. bovis, the genes encoding B. bigemina membrane glycoproteins gp45 and gp55 have not been identified, and the molecular basis of their antigenic diversity among strains remains unexplained. Immunization with affinity-purified native gp45 from the Mexico strain induces protection against homologous challenge, defined as a significant decrease in peak parasitemia compared to adjuvant-inoculated control cattle (21). However gp45, like B. bovis MSA-1, is antigenically polymorphic among strains (21, 27). Sera from Mexico strain gp45-immunized cattle and monoclonal antibody against native Mexico gp45 bind merozoites of the homologous Mexico strain (19–21, 35). In contrast, there is no antibody binding to other strains of B. bigemina isolated from Brazil, Puerto Rico, St. Croix (U.S. Virgin Islands), and Texcoco (Mexico) (19, 21). This complete lack of reactivity using monospecific polyclonal sera from immunized and protected cattle indicates that marked B-cell epitope variation among strains would limit the efficacy of a gp45-based vaccine (4, 6, 24). Whether this antigenic variation reflects polymorphism in a single gp45 gene, analogous to B. bovis msa-1, or the presence of a variably expressed multigene family, similar to B. bovis msa-2, is unknown. In this article, we report the identification of a molecular basis for gp45 antigenic polymorphism among B. bigemina strains isolated from the Americas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

B. bigemina.

The Mexico strain was provided by Will Goff (USDA Animal Disease Research Unit, Pullman, Wash.) and propagated by in vitro cultivation in bovine erythrocytes. The JG-29 biological clone of the Mexico strain was obtained by limiting dilution, as previously described (36, 37). The Puerto Rico, St. Croix, Argentina S1A, and Texcoco strains were isolated from infected cattle in their respective locations (9) and provided as cyropreserved stabilates (37) by Gerald Buening (University of Missouri, Columbia, Mo.) and Ignacio Echaide (Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria, Rafaela, Argentina). An additional six B. bigemina isolates were obtained from acute cases of babesiosis in Puerto Rico that occurred in 1999 and were provided by David Jimenez (Mayaguez, P.R.). All six isolates were analyzed directly without prior cryopreservation, in vitro culture, or in vivo passage.

Antibodies.

Anti-B. bigemina monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) were produced by immunizing mice with Mexico strain merozoites (20). The selection and characterization of these MAbs have been reported in detail previously (20). The MAbs used in this study were 14/1.3.2, which binds the 45-kDa merozoite surface glycoprotein gp45, and 14/16.1.7, which binds the 58-kDa rhoptry-associated protein 1 (RAP-1). Monospecific polyclonal antisera were obtained following immunization of cattle and rabbits with purified gp45 or RAP-1. Rabbits were immunized subcutaneously with 25 μg of native gp45 or RAP-1 in Freund's complete adjuvant and boosted with 15 μg of antigen in incomplete Freund's adjuvant at 1- to 2-week intervals. Calf B261 was immunized intramuscularly with 50 μg of native gp45 in Freund's complete adjuvant, followed by four intramuscular immunizations with 50 μg of native gp45 in incomplete Freund's adjuvant at 2-week intervals. Calf B279 was immunized following the same regimen but with native RAP-1. Sera from a nonimmunized rabbit and from an uninfected, nonimmunized calf (B235) were used as additional negative controls.

Cloning and sequencing of Mexico strain gp45 cDNA.

The gp45 transcript was initially identified by expression screening of a B. bigemina cDNA library in lambda phage ZAP. Merozoites were isolated from an expansion culture of the biological clone JG-29 using a 70% Percoll gradient centrifuged at 30,000 × g (22, 23). mRNA was extracted from these merozoites by lysis in a concentrated guanidinium thiocyanate solution, followed by dilution and binding to an oligo(dT) column. Isolated mRNA was reverse transcribed using a linker-poly(dT) primer according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene). Following blunting and the ligation of EcoRI adapters, the resulting cDNA was cloned into lambda ZAP Express vector. Gigapack II Gold was used to package the cDNA library and transfect Escherichia coli XL1 Blue MRF′ in the presence of 3 mM isopropylthio-β-galactoside and 5 mg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside per ml. Plaque lifts from XL1 Blue-transfected E. coli were immunologically screened using rabbit anti-gp45 serum (R929) at a dilution of 1:10,000, followed by horseradish peroxidase—conjugated caprine anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; heavy and light chains; (Kirkegaard & Perry; 1:2,500 dilution) and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Positive plaques were selected and purified by repeated expansion, plating, and immunological screening. Following phagemid excision, six positive clones were identified, and two were fully sequenced. These sequences were analyzed, assembled, and translated with the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) version 10 Bestfit, Assemble, and Translate programs, respectively (8). Nonredundant GenBank, EMBL, DDBJ, and PDB databases were searched for homologous nucleotide sequences using the BlastN 2.0.10 search engine at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (2). Alignments of multiple sequences were done using PileUp and Gap of GCG version 10 and ClustalW program of the Baylor College of Medicine Search Launcher at www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu. The Swissprot program from GCG was used to search sequence databases for homologous amino acid sequences. Potential modification sites within the gp45 protein were located using the FindPattern and Prosite programs from GCG.

Binding of recombinant gp45 by anti-native gp45 monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies.

Recombinant gp45 protein expressed from XL1 Blue E. coli transformed with gp45 cDNA clone 4.2.2.1.1.1 was tested for specific binding by monoclonal and polyclonal anti-native gp45 antibodies. XL1 Blue E. coli transformed with clone 4.2.2.1.1.1 was grown at 37°C in the presence of 1 mM isopropylthio-β-galactoside for 4 h and then pelleted and lysed as previously described (32). Equivalent amounts of protein from 4.2.2.1.1.1 bacterial lysate supernatant, bacterial lysate supernatant from E. coli transformed with a control plasmid, JG-29 merozoite lysate, and uninfected erythrocyte lysate were electrophoretically separated on a 4 to 20% polyacrylamide gel and transblotted to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked overnight and then incubated for 1 h with 1:500 dilutions of either anti-gp45 monospecific bovine serum (B261) or negative-control calf serum (B235). For MAb binding, membranes were blocked for 30 min, followed by overnight incubation with either MAb 14/1.3.2 or MAb Tryp1E1 (anti-Trypanosoma brucei variable surface glycoprotein) at a final concentration of 2 μg of IgG per ml. For rabbit antibody binding, membranes were blocked for 30 min, followed by overnight incubation with 1:5,000 dilutions of either anti-gp45 monospecific rabbit serum (R929) or nonimmunized rabbit serum. Membranes were then washed, and antibody binding was detected by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated recombinant protein G (Zymed; 1:5,000 dilution), caprine anti-murine IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry; 4 μg/ml), or caprine anti-rabbit IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry; 1:2,500 dilution), followed by ECL detection.

Cloning and sequencing the gp45 genomic locus.

Genomic DNA was isolated from B. bigemina JG-29 merozoites via standard phenol-chloroform extraction methods (32). Isolated DNA was digested with EcoRI, separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, and transblotted to a nylon membrane. For probe construction, 4.2.2.1.1.1 plasmid insert DNA was amplified using primers TGF1.0 and TGF4.1.5 and labeled with digoxigenin according to the manufacturer's instructions (Boehringer Mannheim) with melting, annealing, and extension temperatures of 96, 60, and 72°C, respectively. The resulting 718-bp gp45-specific probe was then hybridized with the membrane overnight at 50°C. The membrane was then washed with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at room temperature, followed by an additional higher-stringency wash of 0.5× SSC–0.1% SDS at 65°C. Probe binding was immunologically detected using a 1:10,000 dilution of antidigoxigenin alkaline phosphatase-labeled Fab fragments (Boehringer Mannheim) followed by ECL detection. Isolated plasmid DNA from the gp45 cDNA clone was used as a positive control for probe binding. A single band of approximately 6.5 kb was detected in the EcoRI-digested genomic DNA.

Genomic DNA was then digested to completion with EcoRI, and the 6- to 7.5-kb fragments were purified and cloned into the Lambda ZAP Express vector. The packaged library was used to transfect XL1 Blue MRF strain E. coli. Plaque lifts onto Hybond N+ nylon membranes (Amersham) were made from transfected E. coli and screened by hybridization using the 718-bp gp45-specific probe as described above. Positive plaques were purified, and phagemids were excised. Two independent positive clones were identified and sequenced in both directions.

Southern blot analysis of gp45 in Mexico strain genomic DNA.

Genomic DNA isolated from B. bigemina JG-29 merozoites was digested with restriction enzymes selected based on the gp45 cDNA and genomic locus sequences and predicted to cleave either within or outside the gp45 gene. In each Southern blot, genomic DNA digested with an enzyme predicted to cut outside the gp45 gene was compared to DNA digested with an enzyme predicted to cut within gp45 and with DNA doubly digested with both types of enzymes. The resulting digested fragments of genomic DNA were separated on a 0.8% agarose gel and transblotted to a nylon membrane. Membranes were then hybridized overnight at 50°C with the 718-bp gp45-specific probe described above or a full-length gp45-specific probe made in the same manner but using primers TGF1.0 and TGF10R. Membranes were then washed, and probe binding was immunologically detected as described above. Isolated plasmid DNA from the gp45 cDNA clone was used as a positive control for probe binding.

Expression of gp45 by B. bigemina strains.

Merozoites were collected from B. bigemina cryopreserved stabilates of Mexico, Puerto Rico, St. Croix, Argentina S1A, and Texcoco strains and the JG-29 clone by centrifugation at 43,700 × g. Merozoite lysates were electrophoretically separated on a 4 to 20% polyacrylamide gel, transblotted to nitrocellulose membranes, and incubated with monospecific bovine serum diluted 1:500 or with MAbs at a final concentration of 2 μg of IgG/ml. Bound antibody was detected as described above. The six 1999 B. bigemina isolates from Puerto Rico were tested for expression of gp45 and RAP-1 using MAbs 14/1.3.2 and 14/16.1.7 in an immunofluorescence assay (27). MAb Tryp1E1 was used as a negative control.

Detection of gp45 genes in additional strains.

Genomic DNA from each strain (Mexico, Puerto Rico, St. Croix, and Texcoco) and the six Puerto Rico 1999 isolates was analyzed in a PCR using gp45-specific primers. Four primer sets were tested: TGF5.0 and TGF10R, TGF1.0 and TGF4.1.5, TGF1.0 and TGF4.3.5, and TGF1.3 and TGF4.1. Amplifications were performed using 30 cycles with melting, annealing, and extension temperatures of 96, 60, and 72°C, respectively. Plasmid DNA from the full-length gp45 cDNA clone served as a positive control. The rap-1 primers B483Fx and B822R, which amplify a 339-bp fragment (12, 13), were used as a positive control for DNA quality of each strain.

For Southern blot detection of gp45-related genes, EcoRI-digested DNA was separated on a 0.8% agarose gel and transblotted to nylon membranes. Membranes were hybridized with the 718-bp gp45-specific probe overnight at 50°C and then washed twice with 2× SSC–0.1% SDS at room temperature for 5 min, followed by two 15-min washes with 0.5×SSC–0.1% SDS at 65°C. Membranes with DNA from the six Puerto Rico isolates from the 1999 outbreak were also incubated with three additional probes spanning the gp45 cDNA sequence: nucleotides (nt) 6 to 257, nt 287 to 630, and nt 827 to 1037. Probe binding was immunologically detected using a 1:10,000 dilution of antidigoxigenin alkaline phosphatase-labeled Fab fragments, followed by ECL detection. Isolated plasmid DNA from the gp45 cDNA clone was used as a positive control for probe binding. To control for the quality of the DNA from each strain and isolate, a 339-bp digoxigenin-labeled rap-1-specific probe, generated using primers B483Fx and B822R (12, 13), was tested under identical hybridization conditions.

Cloning and sequencing of Texcoco gp45 gene.

Primers TGF5.0 and TGF10R, derived from the cDNA sequence of JG-29 gp45, were used to amplify a 1,098-bp segment of the gp45 gene from Texcoco genomic DNA. The amplified product was ligated into pCR-2.1 vector and used to transform INV-F′ bacteria. Recombinant clones were selected, the presence of a gp45 insert was confirmed by PCR with primers TGF 1.0 and TGF4.1.5, and the insert DNA was sequenced. In order to amplify the genomic sequence upstream of the Texcoco gp45 open reading frame (ORF), specific primers were derived from the sequence of the 6.5-kb fragment in the JG-29 clone genomic DNA. These primers, TGF20 and TGF7.0, were used to amplify a 151-bp product from the Texcoco DNA. The amplicon was ligated into pCR-Blunt and used to transform One Shot TOP 10 ultracompetent bacteria (Invitrogen). Recombinant clones were selected, digestion with EcoRI was performed to confirm the presence and size of the insert, and insert DNA was sequenced in both directions.

Detection of gp45 transcription.

Transcription was examined in merozoites containing a gp45 gene, the JG-29 clone of the Mexico strain and the Texcoco strain. Total RNA was isolated from washed merozoites with the RNAqueous total RNA kit (Ambion). Two DNase I treatments of total RNA were performed using 5 U of DNase I per μg of RNA, with incubation for 30 min at 37°C, and were followed by a third incubation using 2 U of DNase I per μg of RNA at 37°C for 60 min. Reverse transcription (RT) was performed using an oligo(dT20) primer and the ThermoScript RT-PCR System (Gibco-BRL). The resulting cDNA was amplified using primers TGF1.0 and TGF4.3.5. As a control for RNA and cDNA quality and amplification conditions, rap-1 was amplified from the cDNA with the B483Fx and B822R primers under the same conditions used for the gp45 amplifications. Identical amplifications but without reverse transcriptase treatment were done to control for contaminating DNA.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Genbank accession nos. AF298630 to AF298632 were assigned to our sequences.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of Mexico strain gp45.

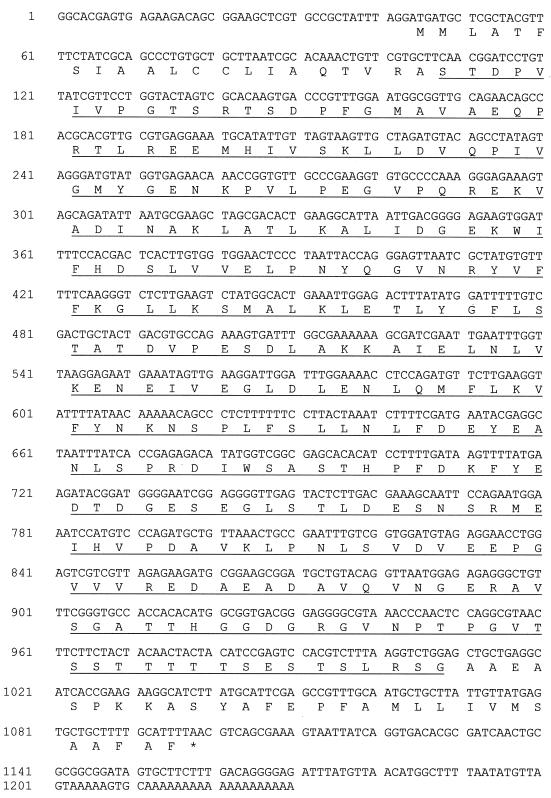

Screening of a cDNA Lambda ZAP expression library of JG-29 B. bigemina with rabbit anti-gp45 monospecific polyclonal serum (R929) led to the identification of four independent gp45-containing clones. The clones each contained a ≥1.5-kb insert, identified by restriction enzyme digestion of immunoreactive clones, and were sequenced in their entirety in both directions. Clone 4.2.2.1.1.1 contained a 1.5-kb cDNA insert composed of 40 bp preceding a 1,058-bp ORF, 110 bp beyond the stop codon, and a poly(A) tail (GenBank accession no. AF298630). The ORF translated into a 351-amino-acid polypeptide. The encoded polypeptide initiated with a double methionine and contained a predicted leader sequence followed by an extracytoplasmic domain (Fig. 1). The amino-terminal hydrophobic domain contains a leader sequence with a predicted cleavage site between amino acids 21 and 22 (25), while the carboxy-terminal domain sequence contains a signal for addition of a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor near amino acid 322 (P = 0.04; ExPASy Molecular Biology Server [expasy.cbr.nrc.ca/program DGPI]).

FIG. 1.

Mexico strain JG-29 gp45 cDNA and amino acid sequence. Nucleotide sequence of clone 4.2.2.1.1.1 and translated ORF. The underlined amino acids designate the mature protein following predicted amino- and carboxy-terminal processing. Base numbers along the left margin refer to nucleotide position.

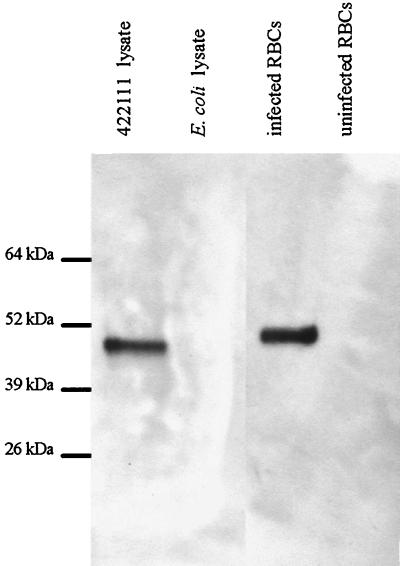

Immunologic reactivity of recombinant gp45.

Proteins within the 4.2.2.1.1.1 bacterial lysate were specifically bound by bovine and rabbit monospecific gp45 polyclonal antisera (B216 and R929) and not by negative control sera (data not shown). Anti-gp45 MAb 14/1.3.2 bound to a single band in each of the 4.2.2.1.1.1 and the JG-29 merozoite lysates (Fig. 2). There was no binding using the control MAb Tryp1E1. The recombinant gp45 protein recognized within the 4.2.2.1.1.1 bacterial lysate had an apparent molecular size 3 kDa smaller than that of native gp45 detected within the JG-29 merozoite lysate (Fig. 2), consistent with the lack of posttranslational modification in E. coli.

FIG. 2.

Recognition of recombinant gp45 by MAb. Lysates from E. coli transfected with plasmid 4.2.2.1.1.1, E. coli transfected with plasmid lacking an insert, B. bigemina-infected bovine erythrocytes (RBCs), and uninfected bovine erythrocytes were electrophoresed on a polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and reacted with anti-gp45 MAb 14/1.3.2. There was no reactivity using the negative control MAb Tryp1E1 (data not shown). Molecular sizes are indicated in the left margin.

Genomic organization of gp45 locus.

An unamplified genomic library prepared from EcoRI-digested JG-29 DNA was screened using a gp45-specific 718-bp probe derived from the cDNA clone, and two independent positive clones were identified. The 6.5-kb cloned inserts were sequenced entirely in both directions and found to be identical. The complete locus sequence has been given accession number AF298631. The gp45 ORF contained within the genomic gp45 clone was identical to that identified in the cDNA clone 4.2.2.1.1.1. There were no homologous gp45 or gp45-like genes within the 1,422 bp upstream or the 3,980 bp downstream of gp45. Three additional ORFs with start and stop codons and encoding a polypeptide of ≥100 amino acids were identified within the 6.5-kb genomic fragment. Four other motifs begin with a start codon and end with a stop codon but encode fewer than 100 amino acids. None of the complete or partial ORFs had an amino acid sequence similar to that of gp45. A Blast search did not reveal significant similarity of these additional ORFs to any other genes in the database.

Southern blots were performed on restriction enzyme-digested genomic DNA isolated from biologically cloned JG-29 merozoites. The 718-bp gp45-specific probe hybridized with a single band of approximately 6.5 kb in EcoRI-digested DNA (data not shown) and a single band of approximately 7.3 kb in XbaI-digested DNA (Fig. 3). Neither EcoRI nor XbaI cuts within gp45 cDNA. The 718-bp probe hybridized with two bands of approximately 12 and 2.8 kb in BamHI-digested DNA (data not shown) and two bands of approximately 4.4 and 2.9 kb in NdeI-digested DNA (Fig. 3). Both BamHI and NdeI cut once within the gp45 cDNA sequence. Double digestion with EcoRI and BamHI resulted in two bands of approximately 4.9 and 1.5 kb (data not shown), EcoRI and NdeI digestion resulted in bands of approximately 5.5 and 2 kb (data not shown), and digestion using XbaI and NdeI resulted in bands of approximately 4.4 and 2.9 kb (Fig. 3). DNA digested with EcoRI, BamHI, or EcoRI and BamHI was also hybridized with a full-length gp45 probe in an attempt to identify sequences homologous to the 3′ end of gp45 that were not represented in the 718-bp probe. However, the banding pattern was the same using the full-length gp45 probe as when the 718-bp probe was used (Fig. 3). The restriction enzyme digestion patterns of JG-29 genomic DNA were consistent with the presence of a single-copy gene, as previously reported for the B. bovis msa-1 locus (11).

FIG. 3.

Southern blot analysis of gp45. Genomic DNA was isolated from JG-29 strain B. bigemina, digested with restriction enzymes, electrophoretically separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, and transblotted to nylon membranes. The selected restriction enzymes were expected to predicted to cleave outside of (∗) or within (+) the gp45 ORF. EcoRI, EcoRI-BamHI, and BamHI digests were hybridized with the full-length gp45 digoxigenin-labeled probe, while XbaI, XbaI-NdeI, and NdeI digests were hybridized with a 718-bp digoxigenin-labeled gp45 probe. (A) Southern blots exposed for 8 min. (B) Two-hour exposure of the EcoRI-BamHI and BamHI lanes of panel A.

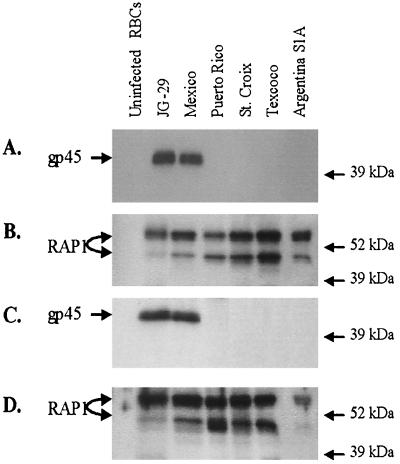

Polymorphism in expression of gp45 among B. bigemina strains.

Western blot analysis of merozoites from American strains of B. bigemina demonstrated strain-specific expression of gp45 B-cell epitopes. Both murine MAbs and bovine monospecific polyclonal serum to native Mexico strain gp45 bound only merozoites of the homologous strain and the biological clone JG-29, derived from the parent Mexico strain (Fig. 4). These antibodies did not bind to merozoite lysates of the other American strains examined here (Argentina S1A, Puerto Rico, St. Croix, and Texcoco), while monospecific polyclonal serum to RAP-1 bound all strains (Fig. 4). The two RAP-1 proteins detected represent the products of the polymorphic rap-1 alleles in each strain (12, 13). These findings replicate previous results using the Mexico, Puerto Rico, St. Croix, and Texcoco strains (20, 21) and demonstrate the binding to the JG-29 clone. In addition to these strains, six uncloned isolates from a 1999 babesiosis outbreak in Puerto Rico were examined for RAP-1 and gp45 expression by immunofluorescence assay on acetone-fixed blood smears. All six isolates were bound by MAb 14/16.1.7 (anti-RAP-1), while MAb 14/1.3.2 (anti-gp45) failed to bind any of the isolates. As a positive control, MAbs 14/16.1.7 and 14.1.3.2 bound the Mexico strain. Neither MAb bound uninfected erythrocytes, and a negative control MAb, Tryp1E1, did not bind to any of the blood smears.

FIG. 4.

Strain-specific expression of gp45. Equal amounts of protein from infected erythrocytes (RBCs) of each strain or from uninfected erythrocytes were electrophoresed on a polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and reacted with antibodies in Western blots. The membranes were reacted with 1:500 dilutions of anti-gp45 (A) or anti-RAP-1 (B) monospecific bovine serum or with 2 μg of anti-gp45 MAb 14/1.3.2 (C) or anti-RAP-1 MAb 14/16.1.7 (D) per ml. Molecular sizes are indicated in the right margin, and the locations of gp45 and RAP-1 are indicated in the left margin.

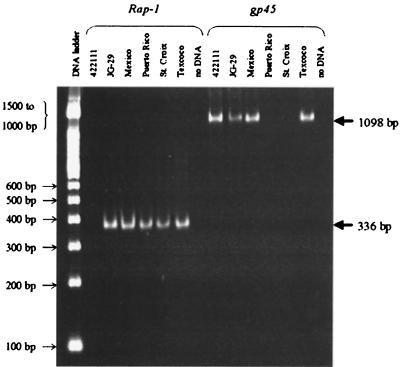

Detection of gp45 genes in additional strains.

Amplicons of the predicted size, 1,098 bp, were obtained when genomic DNA isolated from the parental Mexico strain, the JG-29 Mexico strain clone, and the Texcoco strain was amplified with gp45-specific primer pair TGF5.0 and TGF10R (Fig. 5). No amplicons were obtained from Puerto Rico or St. Croix genomic DNA using the same primers and identical amplification conditions (Fig. 5). Amplification using three additional primer sets, TGF1.0/TGF4.1.5, TGF1.0/TGF4.3.5, and TGF1.3/TGF4.1, resulted in the same pattern, detection in the Mexico and Texcoco strains and the JG-29 clone but not in the Puerto Rico or St. Croix strains (data not shown). Simultaneous amplification of each genomic DNA sample with rap-1-specific primers generated a 339-bp amplicon, confirming the presence of intact B. bigemina genomic DNA (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

PCR-based detection of gp45 genes in American strains of B. bigemina. DNA was amplified using gp45- or rap-1-specific primers under identical reaction conditions, electrophoretically separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel, and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The gp45 cDNA clone 4.2.2.1.1.1 was used as a positive control. Molecular size standards are shown in the left margin, and the predicted sizes of the gp45 amplicons (1,098 bp) and rap-1 amplicons (336 bp) are shown in the right margin.

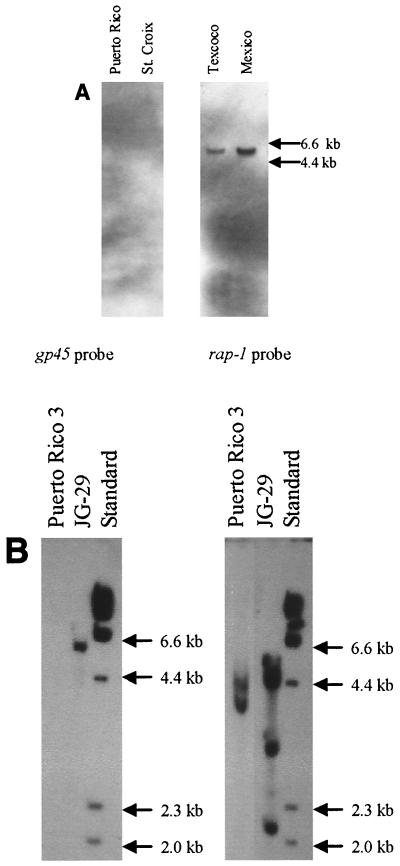

Southern blot analysis using the 718-bp probe derived from the JG-29 gp45 cDNA clone (nt 6 to 724) confirmed the presence of gp45-related genes within the Mexico and Texcoco strains of B. bigemina (Fig. 6A). No gp45-related sequences were detected within genomic DNA from the Puerto Rico or St. Croix strains of B. bigemina (Fig. 6A). Three additional probes derived from the JG-29 cDNA gp45 sequence (251-bp probe spanning nt 6 to 257, 343-bp probe spanning nt 287 to 630, and 210-bp probe spanning nt 827 to 1037) were used to screen additional Southern blots of the uncloned Puerto Rico isolates. No gp45-related gene sequences were detected (Fig. 6B). The presence of intact genomic DNA in each Southern blot was confirmed by the binding of a 339-bp rap-1-specific probe to the multiple rap-1 genes of each sample. The variable number and arrangement of polymorphic rap-1 genes among strains have been described previously in detail (12, 13).

FIG. 6.

(A) Southern blot detection of gp45 genes in American strains of B. bigemina. Equal amounts of genomic DNA from each of the B. bigemina strains were digested with EcoRI, separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, and transblotted to nylon membranes. Membranes were hybridized with a digoxigenin-labeled 718-bp gp45 probe derived from JG-29. Left panel: Puerto Rico and St. Croix strains. Right panel: Texcoco and Mexico strains. Molecular size markers are indicated in the right margin. Distinct bands were observed in all strains using replicate blots which were hybridized with a rap-1 probe under identical conditions (data not shown). (B) Southern blot detection of gp45 in isolates from the 1999 Puerto Rico outbreak. Equal amounts of DNA were digested with EcoRI, electrophoretically separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, and transblotted to nylon. Membranes were hybridized with each of the following three probes derived from the JG-29 strain gp45: nt 6 to 257, nt 287 to 630, and nt 827 to 1037. Replicate membranes were hybridized with a rap-1 probe. Puerto Rico 3 is isolate number 3 from the 1999 outbreak. Molecular size standards are indicated in the right margin. The left panel represents hybridization with the 210-bp gp45 probe spanning nt 827 to 1037. The right panel represents hybridization with a 336-bp rap-1 probe.

Cloning and sequencing of Texcoco gp45 gene.

A 1,098-bp amplicon was generated from Texcoco genomic DNA using gp45-specific primers derived from the cDNA sequence of JG-29 gp45. The 5′ TGF5.0 primer incorporated the start codon of the ORF, and the 3′ TGF10R primer was derived from downstream of the stop codon. This amplicon was cloned and sequenced entirely in both directions. The cloned sequence was identical to the cDNA sequence of JG-29 extending through the entire ORF to the stop codon. Additional primers flanking the start codon (TGF7.0) and upstream of the gp45 orf (TGF20) were used to amplify the 111 bp upstream of and including the start codon of the Texcoco genomic gp45 sequence. The full-length gp45 ORF and upstream sequences in the Texcoco strain have been given GenBank accession no. AF298632. While the gp45 start codon is conserved within the Texcoco strain, 14 mutations were observed within the upstream sequence.

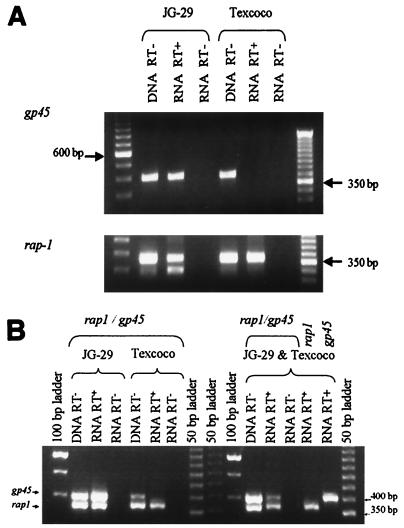

Detection of gp45 transcription.

Transcripts of gp45 were detected within mRNA from JG-29 but not from the Texcoco strain (Fig. 7A). The sequence of the JG-29 amplicon was identical to the corresponding sequence previously identified in both the JG-29 cDNA and genomic DNA. Amplification of rap-1 transcripts from both strains confirmed the integrity of the RNA and cDNA tested (Fig. 7A). Both gp45 and rap-1 could be amplified simultaneously from JG-29 reverse-transcribed mRNA, but only rap-1 could be amplified from Texcoco reverse-transcribed mRNA (Fig. 7B). In contrast, both gp45 and rap-1 could be amplified simultaneously from DNA of either strain (Fig. 7B). The possibility that Texcoco RNA was specifically inhibitory for gp45 transcript amplification was excluded by showing that rap-1 and gp45 could be amplified from cDNA generated using equal amounts of JG-29 and Texcoco RNA (Fig. 7B). No amplicons were generated using RNA as a template if reverse transcriptase was excluded (Fig. 7A and B).

FIG. 7.

Detection of gp45 transcripts. B. bigemina total RNA isolated from JG-29 or the Texcoco strain was reverse transcribed using an oligo(dT20) primer and amplified in reactions using specific primers, TGF1.0 and TGF4.3.5 for gp45 or B483Fx and B822R for rap-1. DNA from each strain was used as a positive control for gene-specific amplification, and RNA without addition of reverse transcriptase (RT) was used as a control for contaminating DNA in the RNA templates.(A) JG-29 or Texcoco strain RNA was reverse transcribed using an oligo(dT20) primer, and cDNA or genomic DNA was amplified using separate reactions for each primer set. Molecular size markers are in the outside lanes, with the positions of the 350-bp and 600-bp markers indicated in the margins. (B) JG-29 and the Texcoco strain RNA were reverse transcribed using an oligo(dT20) primer either in separate reactions or with equal amounts from each strain together in a single reaction. The cDNA or genomic DNA was then amplified using either separate reactions for each primer set or both primer sets in the same reaction. Molecular size markers are in the outside lanes and middle lanes, with the positions of the 300-bp and 400-bp markers indicated in the margins.

DISCUSSION

Multiple lines of evidence support that we have identified the gene that encodes the 45-kDa merozoite surface glycoprotein, gp45, of B. bigemina. First and most importantly, lysates of E. coli transfected with gp45 cDNA clone 4.2.2.1.1.1 and B. bigemina merozoite lysates were compared in a Western blot format using anti-gp45 MAb 14/1.3.2. This MAb, which defines gp45 as a surface-exposed and protection-inducing glycoprotein (20, 21), detected a single protein band in both lysates, while MAb to an unrelated protein failed to detect any proteins within either lysate. The recombinant gp45 is 3 kDa smaller than native gp45, as anticipated from the lack of posttranslational modification of eukaryotic proteins expressed within bacteria. Second, lysates of E. coli transfected with gp45 cDNA clone 4.2.2.1.1.1 and E. coli transfected with control plasmid were compared in a Western blot using polyclonal anti-gp45 serum. Both monospecific polyclonal rabbit anti-native gp45 antibody and native gp45-immunized bovine serum recognized a protein of the predicted size within the 4.2.2.1.1.1. lysates but not in the control E. coli lysates. This protein was not detected by negative control rabbit or bovine serum. Third, the encoded protein is predicted to have structural features, an amino-terminal signal peptide, a central hydrophilic domain in the mature protein, and a carboxy-terminal signal for addition of a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor, previously identified in the native gp45 protein, which is surface exposed, glycosylated, and myristylated (20, 21).

B. bigemina gp45 lacks introns, as shown by the identical ORFs of the genomic and cDNA clones. In addition, unlike the tandem arrangement of B. bovis msa-2 genes, gp45, similar to B. bovis msa-1 (34), is flanked by unrelated ORFs and appears to be present as a single-copy gene. The stringency of the Southern blot analysis was predicted to be capable of detecting additional gp45-like genes with ≥55% homology to the defined gp45 gene. While no additional gp45-like sequences were identified in the Southern blot analysis, the alternative but unlikely explanation of multiple identical copies with identical flanking sequences cannot be definitively excluded (5, 11, 14). Nonetheless, the genomic structure of gp45 is clearly different from that of the multicopy B. bovis msa-2 gene family (14) and suggests that gp45 antigenic polymorphism among strains involves strain-specific differences in the presence, sequence, or regulation of a single gene.

The antigenic polymorphism among B. bigemina strains is a significant constraint to vaccine development (6, 24, 27). The experiments presented here replicate previous results and confirm surface B-cell epitope variation among strains isolated from the Americas (19–21). Both MAb and polyclonal monospecific serum against native gp45 bind epitopes only in the homologous Mexico strain. As anticipated, the expression of gp45 by the biological clone JG-29 mimics that of the uncloned parental Mexico strain. In addition, analysis of six unpassaged Puerto Rico isolates replicated those of the cryopreserved Puerto Rico strain. Together, these results indicate that the epitope variation cannot be attributed to in vitro or in vivo passage, cryopreservation, or biological cloning.

Lack of gp45 expression in American strains was attributed to mechanisms at two levels. The first, typified by the Puerto Rico and St. Croix strains, was the absence of a closely related gp45-like gene. This conclusion was based initially on the inability of PCR with JG-29 gp45-specific primers to generate an amplicon from either strain. The four primer sets selected were from the JG-29 gp45 ORF and allowed amplification of the gene in both the Mexico and Texcoco strains. As a control, rap-1 sequences could be amplified from all strains, including Puerto Rico and St. Croix. To avoid the obvious bias of using specific gp45 primers, Southern blots were then done using four gp45 probes. Initial Southern blots of Puerto Rico and St. Croix genomic DNA were performed using a 718-bp probe derived from the 5′ half of gp45. It is predicted that under the hybridization stringency used, sequences of ≥55% homology would have been detected. Thus, any gp45-like genes in the Puerto Rico and St. Croix strains would be highly polymorphic compared to the Mexico strain and JG29 clone. Three additional probes, ranging from 210 to 343 bp in length and collectively spanning the entire gp45 gene, were used to screen for the presence of any shorter gp45-like sequences within the genomic DNA of uncloned Puerto Rico isolates. These probes would have detected sequences of ≥75% homology to the 5′, central, or 3′ third of gp45 regardless of the homology to the full-length JG-29 gp45 gene, but did not hybridize with the Puerto Rico or St. Croix strains. Furthermore, a gp45-like gene could not be identified within the Puerto Rico strain genome when the orthologous locus was PCR amplified using primers derived from the unrelated ORFs flanking the JG-29 gp45, cloned, and probed for related sequences (data not shown).

Do B. bigemina strains, like Puerto Rico and St. Croix, which lack a closely related gp45-like gene have another functional orthologue? A second glycosylated and myristylated merozoite surface protein, gp55, has been demonstrated to be expressed by the Mexico strain of B. bigemina (20). However, neither gp45 nor gp55, as defined in the Mexico strain, is expressed by the Puerto Rico and St. Croix strains of B. bigemina (20, 21). Alternatively, the Puerto Rico and St. Croix strains may express an as yet unidentified, functionally analogous surface glycoprotein. The ability of parasites defective in a single invasion pathway to utilize alternative pathways has been clearly shown in malarial parasites. Whether this applies to Babesia spp. is unknown.

The second mechanism responsible for the lack of gp45 expression is exemplified by the Texcoco strain. The Texcoco strain contains a gp45 ORF which was identical to that in the Mexico strain and JG-29 clone but was not transcribed. This lack of transcription is specific to gp45, as Texcoco rap-1 transcripts were readily detected. Why this gene is not transcribed is unresolved. However, 9 of 13 potential transcription factor-binding site sequences (TESS and Matlnspector/TRANSFC [29] programs) that are identical to known eukaryotic transcription factor-binding sites, including those shown to function in Plasmodium spp. (18, 33), were altered in the Texcoco genome by the presence of base substitutions. Furthermore, the NNPP/Eukaryotic program identified a single eukaryotic promoter site within the genomic sequence upstream of the JG-29 gp45 gene. Four of the observed base changes upstream of the Texcoco gp45 gene occur within this sequence. Thus, gp45 in the Texcoco strain could simply represent a pseudogene. Alternatively, transcription may be tightly regulated and occur only in nonerythrocytic stages of the parasite life cycle.

The mechanism of B-cell epitope variation in B. bovis MSA-1 has been attributed to extensive polymorphism, presumably arising by mutation, within ORFs encoded by msa-1 in the Mexico and Argentina strains (34). The gp45 antigenic polymorphism in B. bigemina may reflect a similar mechanism, as illustrated by the Puerto Rico and St. Croix strains, in which any gp45-like sequences would be highly polymorphic (<55% identity) compared to the Mexico strain. However, the antigenic polymorphism of gp45 B-cell epitopes between the Mexico and Texcoco strains does not reflect this same mechanism. This generation of antigenic polymorphism in merozoite surface glycoproteins using at least two mechanisms in B. bovis and B. bigemina supports a critical role for surface glycoprotein polymorphism in successful parasitism.

TABLE 1.

PCR primers used to amplify gp45 sequences

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Positiona | Orientation |

|---|---|---|---|

| TGF1.0 | CTCGCTACGTTTTCTATCGC | 6/25 | Sense |

| TGF1.3 | CAGATGCTGTTAAACTGCCG | 750/769 | Sense |

| TGF4.1 | AGATGCCTTCTTCGGTGATG | 997/977 | Antisense |

| TGF4.1.5 | TGCTTTCGTCAAGAGTACTC | 724/705 | Antisense |

| TGF4.3.5 | GTGCCATAGACTTCAAGAGACC | 407/385 | Antisense |

| TGF5.0 | AGGATGATGCTCGCTACGTT | −3/17 | Sense |

| TGF7.0 | GCGATAGAAAACGTAGCGAG | 26/7 | Antisense |

| TGF10R | AGTTGATCGCGTGTCACCTGAT | 1095/1074 | Antisense |

| TGF20 | GCGTAGTCTGTTGCACCTG | −125/−107 | Sense |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Deb Alperin, Bev Hunter, and Carla Robertson for technical assistance and Kelly Brayton and Rich Scott for assistance with the figures.

This work was supported by USAID PCE-G-00-98-00043-00, USDA NRI 96-35204-3667, and NIH K11 AI 01269.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso M, Arello-Sota C, Cereser V H, Cordoves C O, Guglielmone A A, Kessler R, Mangold A J, Nari A, Patarroyo J H, Solari M A, Vega C A, Vizcaino O, Camus E. Epidemiology of bovine anaplasmosis and babesiosis in Latin America and the Caribbean. Rev Sci Technol. 1992;11:713–733. doi: 10.20506/rst.11.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-Blast: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bock R E, de Vos A J, Lew A, Kingston T G, Fraser I R. Studies on failure of T strain live Babesia bovis vaccine. Aust Vet J. 1995;72:296–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1995.tb03558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown W C, Palmer G H. Designing blood-stage vaccines against Babesia bovis and Babesia bigemina. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:275–281. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01471-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowman A F, Bernard O D, Stewart N, Kemp D J. Genes of the protozoan parasite Babesia bovis that rearrange to produce RNA species with different sequences. Cell. 1984;37:653–660. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalrymple B P. Molecular variation and diversity in candidate vaccine antigens from Babesia. Acta Trop. 1993;53:227–238. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(93)90031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Castro J J. Sustainable tick and tickborne disease control in livestock improvement in developing countries. Vet Parasitol. 1997;71:77–97. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(97)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Figueroa J V, Buening G M, Kinden D A, Green T J. Identification of common surface antigens among Babesia bigemina isolates using monoclonal antibodies. Parasitology. 1990;100:161–175. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000061163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guglielmone A A. Epidemiology of babesiosis and anaplasmosis in South and Central America. Vet Parasitol. 1995;57:109–119. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(94)03115-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hines S A, Palmer G H, Jasmer D P, McGuire T C, McElwain T F. Neutralization-sensitive merozoite surface antigens of Babesia bovis encoded by members of a polymorphic gene family. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;55:85–94. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hotzel I, Brown W C, McElwain T F, Rodriguez S D, Palmer G H. Dimorphic sequences of rap-1 genes encode B and CD4+ T helper lymphocyte epitopes in the Babesia bigemina rhoptry associated protein-1. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;81:89–99. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02686-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hotzel I, Suarez C E, McElwain T F, Palmer G H. Genetic variation in the dimorphic regions of rap-1 genes and rap-1 loci of Babesia bigemina. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;90:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jasmer D P, Reduker D W, Hines S A, Perryman L E, McGuire T C. Surface epitope localization and gene structure of a Babesia bovis 44-kilodalton variable merozoite surface antigen. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;55:75–84. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufmann J, editor. Parasitic infections of domestic animals: a diagnostic manual. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhauser Verlag; 1996. pp. 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawrence J A, de Vos A J. Methods currently used for the control of anaplasmosis and babesiosis: their validity and proposals for future control strategies. Parassitologia. 1990;32:63–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence J A, Malika J, Whiteland A P, Kafuwa P. Efficacy of an Australian Babesia bovis bovis vaccine strain in Malawi. Vet Rec. 1993;132:295–296. doi: 10.1136/vr.132.12.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis A P. Sequence analysis upstream of the gene encoding the precursor to the major merozoite surface antigen of Plasmodium yoelii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;39:285–288. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90068-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madruga C R, Suarez C E, McElwain T F, Palmer G H. Conservation of merozoite membrane and apical complex B cell epitopes among Babesia bigemina and Babesia bovis strains isolated in Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 1996;61:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00809-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McElwain T F, Perryman L E, Davis W C, McGuire T C. Antibodies define multiple proteins with epitopes exposed on the surface of live Babesia bigemina merozoites. J Immunol. 1987;138:2298–2304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McElwain T F, Perryman L E, Musoke A J, McGuire T C. Molecular characterization and immunogenicity of neutralization-sensitive Babesia bigemina merozoite surface proteins. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;47:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra V S, McElwain T F, Dame J B, Stephens E B. Isolation, sequence and differential expression of the p58 gene family of Babesia bigemina. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;53:149–158. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90017-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishra V S, Stephens E B, Dame J B, Perryman L E, McGuire T C, McElwain T F. Immunogenicity and sequence analysis of recombinant p58: a neutralization-sensitive, antigenically conserved Babesia bigemina merozoite surface protein. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;47:207–212. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90180-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musoke A J, Palmer G H, McElwain T F, Nene V, McKeever D. Prospects for subunit vaccines against tick-borne diseases. Br Vet J. 1996;152:617–619. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1935(96)80117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielson H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer G H, McElwain T F. Molecular basis for vaccine development against anaplasmosis and babesiosis. Vet Parasitol. 1995;57:233–253. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(94)03123-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer G H, McElwain T F, Perryman L E, Davis W C, Reduker D W, Jasmer D P, Shkap V, Pipano E, Goff W L, McGuire T C. Strain variation of Babesia bovis merozoite surface-exposed epitopes. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3340–3342. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3340-3342.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Payne R C, Osorio O, Ybanez A. Tick-borne diseases of cattle in Paraguay. II. Immunisation against anaplasmosis and babesiosis. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1990;22:101–108. doi: 10.1007/BF02239833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quandt K, Frech K, Karas H, Wingender E, Werner T. Matlnd and Matlnspector—new fast versatile tools for detection of consensus matches in nucleotide sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4878–4884. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.23.4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reduker D W, Jasmer D P, Goff W L, Perryman L E, Davis W C, McGuire T C. A recombinant surface protein of Babesia bovis elicits bovine antibodies that react with live merozoites. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;35:239–248. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ristic M, Kreier J P, editors. Babesiosis. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 445–457. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T, editors. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. pp. 9.16–9.23. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saul A, Battistutta D. Analysis of the sequences flanking the translational start sites of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;42:55–62. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90112-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suarez C E, Florin-Christensen M, Hines S A, Palmer G H, Brown W C, McElwain T F. Characterization of allelic variation in the Babesia bovis merozoite surface antigen-1 (msa-1) locus and identification of a cross-reactive, inhibition-sensitive MSA-1 epitope. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6865–6870. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6865-6870.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suarez C E, McElwain T F, Echaide I, Torioni de Echaide S, Palmer G H. Interstrain conservation of babesial RAP-1 surface-exposed B-cell epitopes despite rap-1 genomic polymorphism. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3576–3579. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3576-3579.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vega C A, Buening G M, Rodriguez S D, Carson C A. Cloning and in vitro propogated Babesia bigmenia. Vet Parasitol. 1986;22:223–233. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(86)90109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vega C A, Buening G M, Rodriguez S D, Carson C A, McLaughlin K. Cryopreservation of Babesia bigmenia for in vitro cultivation. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:421–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]