Future pandemic responses demand a globally coherent approach based on the costly lessons learnt during the COVID-19 pandemic. These themes are discussed in the comprehensive Lancet Commission by Sachs and colleagues,1 and in reports from throughout 2022 on the mpox (formerly known as monkeypox) outbreak,2 and the resurgence of poliomyelitis.3 But what is missing from these discussions is a consistent approach for selecting optimal response strategies for these major emerging and re-emerging diseases. This need is particularly important for outbreaks with the potential to be declared a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC), which is the current status for all three of these diseases.

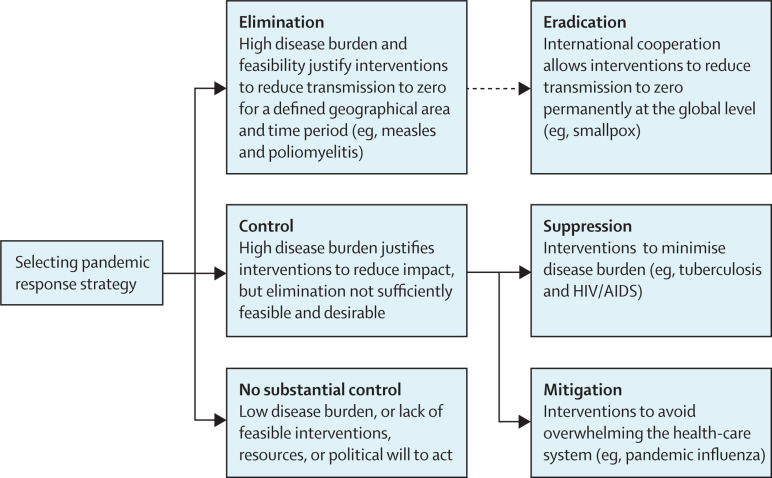

The high-level strategic choices for managing any infectious disease with pandemic and PHEIC potential are illustrated in the figure . This typology is well established and for that reason the term elimination is preferable to the more ambiguous term containment.5 Elimination has the goal of reducing disease transmission to zero for a defined geographical area and time period. In practice, elimination definitions could use less stringent disease-specific criteria in some instances, such as with measles.6 Elimination strategies are widely used for a range of diseases, including poliomyelitis, measles, rubella, filariasis, and dracunculiasis.6, 7 As COVID-19 has shown, an elimination strategy can also be highly effective against a pandemic disease.8 Global eradication, however, is a much more demanding goal, but this has been achieved for smallpox and rinderpest.

Figure.

Major strategic choices for managing an emerging infectious disease with pandemic and public health emergency of international concern potential

Eradication requires additional decision making beyond an initial pandemic response, so its link to elimination is marked with a dotted line. Adapted from Baker et al.4

We consider that a response strategy should be identified for all newly detected emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, and that elimination should be the default option for any infectious disease with a sufficiently high burden and when this goal is potentially feasible.4 Choosing an elimination strategy and making this decision early can potentially delay spread of new infectious diseases, providing time to develop more effective interventions (eg, vaccines and antimicrobials). If applied swiftly in a coordinated way, it could successfully eliminate the disease in some jurisdictions and even contribute to global eradication (which appears to have been the case with severe acute respiratory syndrome, caused by SARS-CoV). Even if elimination is ultimately unsuccessful, it still provides a strong unifying goal for organising interventions. A shared elimination strategy held by neighbouring countries improves the chance of sustained success.

As COVID-19 has shown in several jurisdictions, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region, using an elimination strategy to delay widespread transmission of SARS-CoV-2 for 18 months or more allowed time for development and distribution of effective vaccines. This approach was particularly evident in New Zealand, Australia, and Singapore. The net effect was that such countries had relatively low cumulative COVID-19 mortality, less pressure on health services, and better economic outcomes, than most other high-income countries.4, 9

A clear strategy provides a purposeful way of organising interventions. An elimination lockdown is a relatively short, intense, stay-at-home order designed to help end an infectious disease outbreak. Elimination lockdowns were used very successfully by several jurisdictions as part of their elimination strategy.8 By contrast, a lockdown used as part of a mitigation or suppression strategy has a completely different meaning and purpose and typically needs to be extended or repeated as the still circulating infectious agent will cause a resurgence if controls are reduced.

Even with a pandemic disease threat that is less severe than COVID-19, such as mpox, much of the world appears to have adopted an elimination strategy without articulating this common goal. Global eradication of mpox is not feasible at present as there are unknown animal reservoirs for this infection in Africa. A strategy of eliminating this disease could also support capacity building in low-income and middle-income countries.

WHO is the obvious agency to coordinate global infectious disease strategies. This organisation is leading explicit regional elimination and global eradication programmes for multiple diseases such as poliomyelitis.7 Even with that role, WHO did not provide similar strategic leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic despite the conspicuous success of elimination strategies in some countries.

Possibly the greatest lesson from the COVID-19 pandemic is the crucial need for a coherent and consistent strategy for managing new emerging infectious diseases.10 We recommend that WHO, as part of the PHEIC assessment process, also decides on an optimal response strategy, for example elimination, suppression, or mitigation. This step could strengthen the role of WHO in supporting a more proactive, coordinated, and effective approach to global pandemic management. As with declaring a PHEIC, the response strategy could explicitly change over time as new information and interventions become available.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sachs JD, Karim SSA, Aknin L, et al. The Lancet Commission on lessons for the future from the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2022;400:1224–1280. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01585-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nuzzo JB, Borio LL, Gostin LO. The WHO declaration of monkeypox as a global public health emergency. JAMA. 2022;328:615–617. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.12513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mercader-Barceló J, Otu A, Townley TA, et al. Rare recurrences of poliomyelitis in non-endemic countries after eradication: a call for global action. Lancet Microbe. 2022;3:e891–e892. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker MG, Wilson N, Blakely T. Elimination could be the optimal response strategy for COVID-19 and other emerging pandemic diseases. BMJ. 2020;371 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowdle WR. The principles of disease elimination and eradication. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76(suppl 2):22–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espinal MA, Alonso M, Sereno L, et al. Sustaining communicable disease elimination efforts in the Americas in the wake of COVID-19. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;13 doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopkins DR. Disease eradication. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1200391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker MG, Wilson N, Anglemyer A. Successful elimination of COVID-19 transmission in New Zealand. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:e56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliu-Barton M, Pradelski BSR, Aghion P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 elimination, not mitigation, creates best outcomes for health, the economy, and civil liberties. Lancet. 2021;397:2234–2236. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00978-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark H, Cárdenas M, Dybul M, et al. Transforming or tinkering: the world remains unprepared for the next pandemic threat. Lancet. 2022;399:1995–1999. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00929-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]