ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: The aim of this study was to identify a signature lipid profile from cerebral thrombi in acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients at the time of ictus. METHODS: We performed untargeted lipidomics analysis using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry on cerebral thrombi taken from a nonprobability, convenience sampling of adult subjects (≥18 years old, n = 5) who underwent thrombectomy for acute cerebrovascular occlusion. The data were classified using random forest, a machine learning algorithm. RESULTS: The top 10 metabolites identified from the random forest analysis were of the glycerophospholipid species and fatty acids. CONCLUSION: Preliminary analysis demonstrates feasibility of identification of lipid metabolomic profiling in cerebral thrombi retrieved from AIS patients. Recent advances in omic methodologies enable lipidomic profiling, which may provide insight into the cellular metabolic pathophysiology caused by AIS. Understanding of lipidomic changes in AIS may illuminate specific metabolite and lipid pathways involved and further the potential to develop personalized preventive strategies.

Keywords: acute ischemic stroke, biomarkers, cerebral thrombus, cholesterol, lipidomics, metabolomic profile, nursing research

Ischemic stroke is the second leading cause of death and one of the leading causes of disability globally.1 The consequences of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) are both individual and social, leading to an estimated $34 billion annually in direct and indirect costs, primarily due to lost productivity.1 In AIS, the blockage caused by the cerebral thrombus produces initial hypoxic damage, followed by inflammation and disturbances of lipid metabolism.2,3 There is limited research examining the effects of the physiological lipidomic changes associated with adults after AIS. Acute ischemic stroke treatments focus on removing the thrombus and reestablishing cerebral blood flow as quickly as possible, via intravenous lytics (tissue plasminogen activator or mechanical thrombectomy).4–6 Mechanical thrombectomy provides a novel opportunity to study lipid metabolism by allowing researchers to collect the aspirated thrombus and blood from the infarct zone.7,8

There is evidence of interactions between plasma lipoproteins in ruptured atherosclerotic plaques and platelet function.9 Some patient population groups (eg, hypercholesterolemia patients) have evidence of abnormal platelet function, which is mediated by the binding of lipoproteins, especially oxidized low-density lipoprotein, to surface receptors.10 In addition, abnormal plasma lipid levels precipitate membrane composition changes by increasing the cholesterol-to-phospholipid ratio.11 The resulting changes in microviscosity seem to affect transmembrane signaling and may influence receptor binding.11 This has important implications not only with regard to preventive lipid-lowering drug therapy but also with regard to the development of more focused therapeutics in the setting of acute stroke. New science is emerging on the role of the human microbiota in ischemic stroke and processes resulting from human host-microbial interactions.12,13 Metabolic and other cellular debris within stroke thrombi may provide valuable information as to origin and perhaps inform future treatment.

A limited number of studies have analyzed the histological contents of retrieved cerebral thrombi. These analyses have largely focused on the thrombus morphology and the relative concentration of erythrocytes, leucocytes, platelets, and fibrin within the thrombus.14,15 These human host-derived structural components aid in the selection of devices used in thrombectomy and have also been correlated with the efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator.16 Other omic studies have identified 50 unique microRNA signatures in cerebral thrombi from AIS patients (n = 55; 71 years old) that correlate with stroke subtype etiology (large artery atherosclerosis, cardioembolism with atrial fibrillation, and cardioembolism with valvular heart disease).17 Recently, nonhuman host components of cerebral thrombi have also been described. Patrakka et al18 identified bacterial signatures in cerebral thrombi (Streptococcus species, mainly S. mitis, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans) from AIS patients (n = 75; 67 years old). Bacterial DNA was detected in 84% of aspirated thrombus samples. The Streptococcus species DNA contained approximately 5 times more S. mitis DNA in samples from AIS patients compared with controls.18

These studies demonstrate that analysis of thrombus structure is important, but there is a critical knowledge gap related to the functional components within thrombus. Lipidomic profiling is a powerful tool enabling large-scale study of pathways and networks of lipid metabolites in a biological system at a specific point in time.19 Sphingomyelin, ceramide, and cholesterol are involved in structural and functional integrity of neuronal membranes and mediate inflammatory responses.20 Changes in membrane sphingolipids and cholesterol may lead to changes in membrane permeability and result in neurodegeneration. Characterization of the lipid profile from cerebral thrombi in AIS has the potential to elucidate additional pathophysiological mechanisms underlying AIS, offering new avenues of research related to stroke etiology and prevention. The purpose of the study was to identify a signature lipid profile from cerebral thrombi in AIS patients at the time of ictus.

Materials and Methods

A prospective observational study design was used to identify a signature lipid profile from cerebral thrombi in AIS patients at the time of ictus. This study was conducted at a large academic comprehensive stroke center in Seattle, Washington. Thrombi not required for clinical studies were collected for this investigation from May 2020 through December 2020. Specimens were retrieved during standard-of-care procedures and preserved using a tissue banking protocol optimized for omic analysis. This study was a nonprobability, convenience sampling of adult subjects (≥18 years old) who underwent thrombectomy for large vessel occlusion. All subjects were documented to be COVID negative at the time of thrombectomy. The institutional review board of the University of Washington approved the study.

Study Setting

Adult patients (≥18 years old) were eligible for inclusion if they underwent mechanical thrombectomy for large vessel occlusion as defined by established guidelines,21 and a thrombus was retrieved for analysis.

Data Collection

A medical record review was conducted to collect admission clinical and demographic variables. These variables included age, sex, ethnicity, race, body mass index, chronic comorbid conditions, smoking status, lipid panel on admission, home medication, lytic treatment, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) on admission, and time of last known well symptom (before ischemic stroke). In addition, end point variables were collected, namely, thrombolysis in cerebral infarction scores, stroke location, and NIHSS at discharge. Clinical and demographic variables, along with postthrombectomy end points, were deidentified and maintained in our institution's REDCap software.

Thrombus Collection and Storage

During the thrombectomy, a combined technique was used. In addition to stent retriever, aspiration was applied through an intermediate catheter as well as a large-bore guide catheter positioned in the cervical carotid to help ensure first-pass reperfusion. Because the thrombus is frequently adherent to the stent retriever or catheters, it must be washed with sterile saline and gently manipulated in order for transfer into the sterile collection receptable. All thrombi were retrieved after a single pass, to minimize confounding effects from vascular injury and/or blood products that may accumulate after multiple passes are attempted. Thrombus samples were transferred to the −80°C freezer at the conclusion of the procedure, within 4 hours of collection, and stored until lipidomic analysis.

Untargeted Lipidomics Approach

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry grade methanol, dichloromethane, and ammonium acetate were purchased from Fisher Scientific and high-performance liquid chromatography grade 1-propanol was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Milli-Q water was obtained from an in-house Ultrapure Water System by EMD Millipore. The Lipidyzer isotope-labeled internal standards mixture consisting of 54 isotopes from 13 lipid classes was purchased from SCIEX.

Sample Preparation

Untargeted lipidomic profiling was conducted at the University of Washington's Northwest Metabolomics Research Center in December 2020. Each thrombus sample was weighed at room temperature (25°C). Because the weights did not match the appearance after homogenization, 10% of the homogenized sample was taken to measure protein by bicinchoninic acid. On the basis of the protein results, the amount of homogenized sample was scaled to aliquot for lipid extraction so that the sample amounts were similar. Each sample homogenization was transferred to a borosilicate glass culture tube (16 × 100 mm). Next, 250 μL of water, 1 mL of methanol, and 450 μL of dichloromethane were added to all samples. The mixture was vortexed for 5 seconds, and 25 μL of the isotope-labeled internal standards mixture was added to the tube. Samples were left to incubate at room temperature for 30 minutes. Next, another 500 μL of water and 450 μL of dichloromethane were added to the tube, followed by gentle vortexing for 5 seconds, and centrifugation at 2500 × g at 15°C for 10 minutes. The bottom organic layer was transferred to a new tube, and 900 μL of dichloromethane was added to the original tube for a second extraction. The combined extracts were concentrated under nitrogen and reconstituted in 250 μL of the running solution (10-mM ammonium acetate in 50:50 methanol-dichloromethane). A pooled quality control sample was then made by combining small aliquots (~10 μL) from each sample. This pooled quality control was analyzed twice for the study samples to serve as a replicate throughout the data set to assess process reproducibility and allow for data normalization to account for any instrument drift.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

Quantitative lipidomics was performed with the SCIEX Lipidyzer platform consisting of Shimadzu Nexera X2 LC-30AD pumps, a Shimadzu Nexera X2 SIL30 AC autosampler, and a SCIEX QTRAP 5500 mass spectrometer equipped with SelexION for differential mobility spectrometry (DMS). 1-Propanol was used as the chemical modifier for DMS. Initiation of the samples to the mass spectrometer by flow injection analysis occurred at 8 μL/min. Each sample was injected twice, once with the DMS on (PC/PE/LPC/LPE/SM) and once with the DMS off (CE/CER/DAG/DCER/FFA/HCER/LCER/TAG). The lipid molecular species were measured using multiple reaction monitoring and positive/negative polarity switching. Positive ion mode detected lipid classes SM/DAG/CE/CER/DCER/HCER/DCER/TAG, and negative ion mode detected lipid classes LPE/LPC/PC/PE/FFA. A total of approximately 1000 lipids were targeted in the analysis. Overall, 650 to 700 lipids were detected in the lipid library from the assay.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive and frequency statistics (means, standard deviations, frequency distribution, and percentages) were used to characterize AIS subjects. Demographics and baseline characteristics were analyzed using SPSS version 28 software (IBM). Lipid species composition data were analyzed and processed using Analyst 1.6.3 and Lipidomics Workflow Manager 1.0.5.0. We determined whether each lipid species had been previously characterized in the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB), LIPIDMAPS, KEGG, and NIST libraries.22,23

Statistical and pathway analyses were carried out using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (Free Software Foundation), an open-source software for metabolomics/lipidomics.24 MetaboAnalyst 5.0 uses standard hyperparameters including node size, number of trees, and number of features sampled before training. MetaboAnalyst supports a wide variety of data input types generated by metabolomic studies including GC/LC-MS raw spectra, MS/NMR peak lists, NMR/MS peak intensity table, NMR/MS spectral bins, and metabolite concentrations.25 The Web interface of MetaboAnalyst was implemented based on the JavaServer Faces Technology using the PrimeFaces library (v11.0). The interactive visualization was implemented using JavaScript. Most of the back-end computations are evaluated by 700+ functions written and built into R (MetaboAnalystR package). For the past decade, MetaboAnalyst has evolved to become the most widely used platform (>300 000 users) in the metabolomics community.

Random forest was applied for data analysis. Random forest is a supervised machine learning classification algorithm used for classification that combines the output of multiple decision trees to reach a single result. Random forest has been shown to generate accurate and stable predictions for data analysis with relatively small sample sizes. Each forest contained 5000 trees, and each tree was grown from randomly selected 7 features. The importance of each feature was quantified by the mean decrease in accuracy when the feature was excluded from building a forest.26 We removed any metabolite/lipid with >50% missing values, estimated missing values using k-nearest neighbor, and standardized data by mean and standard deviation. To search for metabolites/lipids from AIS participants, we performed supervised statistical methods for signal selection. The leave-one-person-out cross-validation approach, a k-fold cross-validation technique,27 was applied to this data set. Leave-one-person-out cross-validation has been used to validate models where large variations are expected between participants.28 Because of the limitations described previously, leave-one-person-out cross-validation was selected for model validation to reduce bias from standard test/train splits during analysis.29

Results

Sample Characteristics

Five subjects were included in this study from the University of Washington Clot Bank registry; individual subject characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The average age was 53 ± 26.4 years, and most subjects were male (3 men, 2 women) and White. The most common comorbid conditions were atrial fibrillation (40%) and hypertension (40%). The most common home medications (before AIS) were β-blockers (60%), followed by low-dose aspirin (40%) and diuretics (40%). The NIHSS was 12 on admission and 6 at discharge (median scores). Cerebral thrombus samples were collected at one of the earliest time points (average of 9 hours and 37 minutes from last known well to reperfusion time) during an ongoing stroke.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

| Persons With Acute Ischemic Stroke (n = 5) | |

|---|---|

| Male sex, % | 60 |

| Age, y | 53.0 (26.4) |

| Race | |

| Black | 20% |

| White | 60% |

| Declined | 20% |

| Comorbidities and stroke risks | |

| Smokers (current) | 60% |

| Atrial fibrillation | 40% |

| Hypertension | 40% |

| Carotid stenosis | 10% |

| BMI | |

| Underweight/normal weight | 20% |

| Overweight | 40% |

| Obese | 20% |

| Morbidly obese | 20% |

| Lipid panel on admission | |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 134.2 (23.2) |

| HDL, mg/dL | 28.8 (16.2) |

| LDL, mg/dL | 74.0 (21.4) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 233.4 (155.5) |

| Medications (home) | |

| ACE-I | 20% |

| Low-dose ASA | 40% |

| β-Blockers | 60% |

| Diuretics | 40% |

| Thyroid medication | 20% |

| NIHSS on admission | 12a (15.6) |

| Moderate stroke (5–15) | 60% |

| Severe stroke (≥21) | 40% |

| NIHSS on discharge | 6a (15.5) |

| Minor stroke (1–4) | 40% |

| Moderate stroke (5–15) | 20% |

| Severe stroke (≥21) | 40% |

| tPA administration | 40% |

| Stroke location | |

| Left MCA | 40% |

| Right MCA | 20% |

| Right ICA | 40% |

| TICI score | |

| 3, complete reperfusion | 100% |

| LKW to reperfusion time, h | 9.4 (2.4) |

Note. Data are reported as mean (SD), unless otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ASA, aspirin; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; ICA, internal carotid artery; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LKW, last known well; MCA, middle cerebral artery; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; TICI, thrombolysis in cerebral infarction; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator.

aIndicates median.

Phospholipids of Cerebral Thrombi

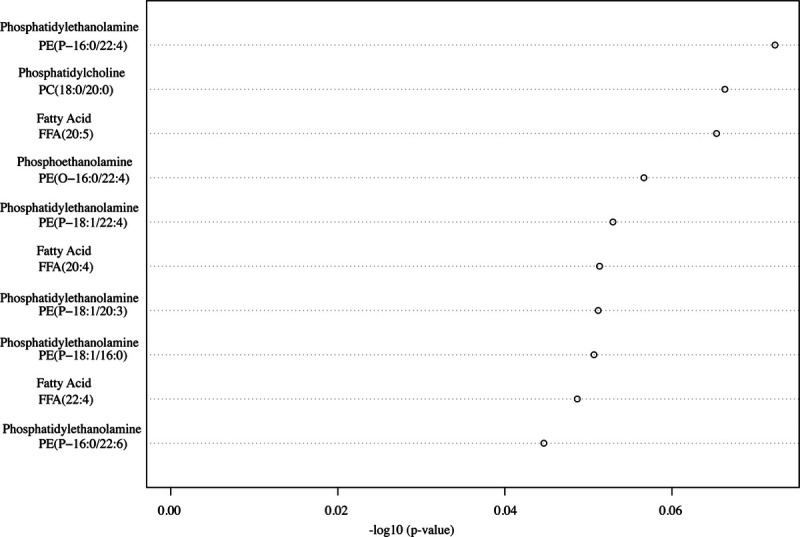

The top 10 metabolites identified from the preliminary random forest analysis were mainly of the glycerophospholipid species (phosphatidylethanolamine [PE], phosphoethanolamine, and phosphocholine) and fatty acids (Fig 1). The 10 metabolites were PE (PE[P-18:1/16:0], HMDB0011371; PE[P-18:1/20:3], HMDB0011391; PE[P-16:0/22:6], HMDB0005780; PE[O-16:0/22:4], HMDB0009009; PE[P-16:0/22:4], HMDB11358), phosphoethanolamine (PE[O-16:0/22:4], HMDB0011158), phosphatidylcholine (PC) (PC[18:0/20:0], HMDB0008043), lignoceric acid/tetracosanoic acid (FFA[24:0], HMDB0002003), flufenamic acid (FFA[20:5], HMDB0252331), and hexadienoic acid (FFA[22:4], HMDB0029581).

FIGURE 1.

The top 10 lipids of interests from adults with acute ischemic stroke.

Discussion

Our preliminary analysis identified the top 10 lipids of interests from adults with AIS, PE, phosphoethanolamine, phosphocholine, and fatty acids. The brain is rich is phospholipid content and comprises 75% of lipids in cells. In addition to their role in mediating the host inflammatory response, phospholipids are involved in structural and functional integrity of cellular membranes of both the host and the human microbiota.30,31 Changes in the structure or function of membrane phospholipids of host or relevant human microbiota may lead to alterations in membrane permeability and contribute to the pathology of diverse conditions including AIS, trauma, and neurodegeneration.32 However, with appropriate and timely recognition, the potential exists to reverse metabolic consequences of “at-risk” brain tissue.

Lipidomic results demonstrated elevated concentration levels of PCs, PEs, and fatty acids among adults with AIS within the first 24 hours of hospitalization. An explanation for the increased concentration levels in phospholipids could be attributed to repair of compromised phospholipid membranes and an early response to AIS. Phospholipid levels have been reported in the brains, serum, and plasma of patients with AIS and/or in animal models of AIS (transient middle cerebral artery occlusion). Phosphoethanolamine and PC have been shown to be significantly higher in individuals with chronic comorbidities who experienced AIS compared with those without AIS.33 Furthermore, serum metabolic profiling has identified higher levels of lipid metabolites, including PE, lyso-PE, PC, lyso-PC, and phosphatidylserine in AIS patients compared with healthy controls.34 The presence of altered lipid metabolism in AIS has also been confirmed in animal studies. A transient middle cerebral artery occlusion mouse model using mass spectrometry imaging demonstrated a significant increase of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate in the penumbra 24 hours post transient middle cerebral artery occlusion and PC and lyso-PC isoforms in the infarction region compared with uninjured healthy brain tissue.35

Lipids identified in thrombi may relate to etiology subtypes, systemic thrombosis or pathology at the site of origin, or local tissue responses and continued interaction with blood products at the site of occlusion. In hypercholesterolemia patients, there is evidence of abnormal platelet function mediated by the binding of lipoproteins. In subjects with diffuse intracranial atherosclerosis, arterial wall cholesterol content is a predictor of development and severity of arterial thrombosis and may contribute to additional thrombogenesis.36 These findings suggest there may be opportunities to exploit a novel metabolic regulatory pathway in platelets that influences thrombus formation by modulating the content of specific lipids/phospholipids, which generate key mediators of platelet activation. In addition, abnormal plasma lipid levels precipitate membrane composition changes by increasing the cholesterol-to-phospholipid ratio. The resulting changes in microviscosity may contribute to thrombus structure, and elevated ratios identified in thrombi may reinforce or present new opportunities for secondary prevention. Furthermore, the propensity of atherosclerotic plaques to rupture may be influenced by their lipid distribution and content. After plaque disruption and mobilization, additional thrombus formation may occur once exposed to blood from the arterial lumen because plaque debris has been shown to contain potent thrombogenic agents such as tissue factor, collagen, and lipids.37 Differences in thrombus lipid composition, species, and distribution between stable and unstable plaques may reflect differences in lipid pools and the degree of macrophage involvement.38 The role of lipidomic molecules in AIS is complex, requiring additional studies to determine how and whether plaque lipids influence the stability of plaques, or whether these are causal risk factors related to stroke subtypes and metabolic comorbid conditions, or reflect anticoagulation, antiplatelet, and lipid-lowering therapies.

Distinguishing between stroke subtypes and knowing the time of stroke onset are critical in clinical and nursing practice. Classification of stroke subtype could aid in early treatment and prevention of long-term recurrence in patients. A complementary approach for blood biomarkers in acute stroke diagnosis may be to identify thrombus biomarkers that reflect the body's response to the damage at the site of origin caused by the different types of stroke. This could assist in clarifying the pathophysiological mechanism of AIS and promoting the secondary prevention and management of patients who experienced AIS.

The pilot nature of this study, including a small sample size (n = 5), and lack of controls are limitations to this study. Using an untargeted lipidomics approach provides several thousands of known and unknown metabolites and lipids, thus limiting much of our focus to the known associations and causing difficulty in identifying unknown but potentially relevant lipids. Additional studies using a targeted lipidomic approach will be necessary to verify lipids associated with AIS, including an assessment of the human host response, environmental controls, and any microbial-derived contributions. Identified lipids in this study may also be influenced by the gut microbiome. We did not control for diet, and because of the emergent nature of AIS, subjects may not have fasted before thrombus collection. Lipid-altering medications may also affect lipidomic investigations, but it is not known whether the lipid metabolites identified in the thrombi are acute or chronic contributors to pathology and at what stage of AIS they are generated. Acute ischemic stroke subjects received propofol infusion for sedation during thrombectomy, and this may have affected lipid levels.

Nurses play a key role in the prevention and management of AIS. Recent advances in omics-based science may inform tailored approaches to nursing practice.39 Biomarker signatures offer a vital resource for predicting stroke severity and identifying those who would benefit from early intervention to promote optimal recovery. Analysis of thrombi samples using approaches such as lipidomics may provide knowledge of early pathophysiological changes after AIS onset, the interplay of different pathways of injury, and responsiveness to reperfusion treatment. Future studies will focus on specific lipids and related metabolites compared between plasma and thrombi samples, and associations to symptoms and outcomes. Should pathophysiological mechanisms related to lipid metabolism underlie development of symptoms and outcomes in AIS, relevant treatments to address changes could be tested for efficacy in AIS survivors in a future clinical trial. Interventions (eg, dietary, physical activity) that reduce or enhance lipid metabolism could be used to improve symptoms and outcomes in AIS survivors. The presence of increased lipid levels and association to clinical outcomes may indicate those with an increased risk for disability and poorer health post AIS, enabling development of personalized interventions to improve symptoms and functional outcomes.

Conclusion

High-throughput techniques were applied to cerebral thrombi from AIS subjects for the purpose of testing feasibility of lipidomic analysis on this novel biospecimen. Multiple substances were identified including PE, phosphoethanolamine, phosphocholine, and fatty acids. Thrombi from cerebral arteries of AIS patients are untapped resources that enable direct evaluation of lipid biological markers. Understanding of lipidomic changes in AIS may illuminate specific metabolite and lipid pathways involved and further the potential to develop personalized preventive strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the University of Washington's Northwest Metabolomics Research Center for their analytical support.

Footnotes

The data sets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author (S.R.M.).

This work was supported by Dr. Hilaire Thompson’s Joanne Montgomery Endowed Professorship. Dr. Sarah Martha was supported by NIH/NINR T32NR016913 and is currently supported by NIH/NINR K23NR019864.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. M.R.L. has received educational grants from Stryker and Medtronic. M.R.L. has equity interest in Synchron, Cerebrotech, Proprio, Hyperion Surgical, and Fluid Biomed. M.R.L. is an adviser for Metis Innovative. M.R.L. is a consultant for Medtronic and Aeaean Advisers. M.W. has received research support from Cerenovus and was previously an educational consultant to Medtronic.

Contributor Information

Samuel H. Levy, Email: samlevy@uw.edu.

Emma Federico, Email: emmafed@uw.edu.

Michael R. Levitt, Email: mlevitt@u.washington.edu.

Melanie Walker, Email: walkerm@uw.edu.

References

- 1.Virani SS Alonso A Aparicio HJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(8):e254–e743. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doyle KP, Simon RP, Stenzel-Poore MP. Mechanisms of ischemic brain damage. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55(3):310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tobin MK, Bonds JA, Minshall RD, Pelligrino DA, Testai FD, Lazarov O. Neurogenesis and inflammation after ischemic stroke: what is known and where we go from here. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34(10):1573–1584. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group . Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/nejm199512143332401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goyal M Menon BK van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387(10029):1723–1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkhemer OA Fransen PS Beumer D, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser JF Collier LA Gorman AA, et al. The Blood And Clot Thrombectomy Registry And Collaboration (BACTRAC) protocol: novel method for evaluating human stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019;11(3):265–270. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maekawa K Shibata M Nakajima H, et al. Erythrocyte-rich thrombus is associated with reduced number of maneuvers and procedure time in patients with acute ischemic stroke undergoing mechanical thrombectomy. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2018;8(1):39–49. doi: 10.1159/000486042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bentzon JF, Otsuka F, Virmani R, Falk E. Mechanisms of plaque formation and rupture. Circ Res. 2014;114(12):1852–1866. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang N, Tall AR. Cholesterol in platelet biogenesis and activation. Blood. 2016;127(16):1949–1953. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-631259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gasser JA, Betteridge DJ. Lipids and thrombosis. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;4(4):923–938. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(05)80085-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battaglini D Pimentel-Coelho PM Robba C, et al. Gut microbiota in acute ischemic stroke: from pathophysiology to therapeutic implications. Front Neurol. 2020;11:598. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pluta R, Januszewski S, Czuczwar SJ. The role of gut microbiota in an ischemic stroke. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(2):915. doi: 10.3390/ijms22020915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niesten JM van der Schaaf IC van Dam L, et al. Histopathologic composition of cerebral thrombi of acute stroke patients is correlated with stroke subtype and thrombus attenuation. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bacigaluppi M, Semerano A, Gullotta GS, Strambo D. Insights from thrombi retrieved in stroke due to large vessel occlusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2019;39(8):1433–1451. doi: 10.1177/0271678x19856131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niessen F, Hilger T, Hoehn M, Hossmann KA. Differences in clot preparation determine outcome of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator treatment in experimental thromboembolic stroke. Stroke. 2003;34(8):2019–2024. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000080941.73934.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JM Byun JS Kim J, et al. Analysis of microRNA signatures in ischemic stroke thrombus. J Neurointerv Surg. 2022;14(5):neurintsurg-2021-017597. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-017597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patrakka O Pienimäki JP Tuomisto S, et al. Oral bacterial signatures in cerebral thrombi of patients with acute ischemic stroke treated with thrombectomy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(11):e012330. doi: 10.1161/jaha.119.012330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh A. Tools for metabolomics. Nat Methods. 2020;17(1):24. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0710-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF. Altered lipid metabolism in brain injury and disorders. Subcell Biochem. 2008;49:241–268. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8831-5_9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powers WJ Rabinstein AA Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344–e418. doi: 10.1161/str.0000000000000211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanehisa M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 2019;28(11):1947–1951. doi: 10.1002/pro.3715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institute of Standards and Technology . National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Standard Reference Database. Available at: https://www.nist.gov/srd/nist-standard-reference-database-1a-v17. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- 24.Chong J, Wishart DS, Xia J. Using MetaboAnalyst 4.0 for comprehensive and integrative metabolomics data analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2019;68(1):e86. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia J, Psychogios N, Young N, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst: a web server for metabolomic data analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(suppl 2):W652–W660. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Ishwaran H. Random forests for genomic data analysis. Genomics. 2012;99(6):323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu T, Sun Y, Jia W, Li D, Zou M, Zhang M. Study on the estimation of forest volume based on multi-source data. Sensors. 2021;21(23):7796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kearns M, Ron D. Algorithmic stability and sanity-check bounds for leave-one-out cross-validation. Neural Comput. 1999;11(6):1427–1453. doi: 10.1162/089976699300016304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ko AH, Cavalin PR, Sabourin R, De Souza Britto A. Leave-one-out-training and leave-one-out-testing hidden Markov models for a handwritten numeral recognizer: the implications of a single classifier and multiple classifications. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2009;31(12):2168–2178. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2008.254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF. Role of lipids in brain injury and diseases. Future Lipidol. 2007;2(4):403–422. doi: 10.2217/17460875.2.4.403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho G, Lee E, Kim J. Structural insights into phosphatidylethanolamine formation in bacterial membrane biogenesis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):5785. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85195-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muralikrishna Adibhatla R, Hatcher JF. Phospholipase A2, reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxidation in cerebral ischemia. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40(3):376–387. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Afshinnia F Jadoon A Rajendiran TM, et al. Plasma lipidomic profiling identifies a novel complex lipid signature associated with ischemic stroke in chronic kidney disease. J Transl Sci. 2020;6(6):419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun H, Zhao J, Zhong D, Li G. Potential serum biomarkers and metabonomic profiling of serum in ischemic stroke patients using UPLC/Q-TOF MS/MS. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mulder IA Ogrinc Potočnik N Broos LAM, et al. Distinguishing core from penumbra by lipid profiles using mass spectrometry imaging in a transgenic mouse model of ischemic stroke. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1090. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37612-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lepropre S Kautbally S Octave M, et al. AMPK-ACC signaling modulates platelet phospholipids and potentiates thrombus formation. Blood. 2018;132(11):1180–1192. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-02-831503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilcox JN. Analysis of local gene expression in human atherosclerotic plaques by in situ hybridization. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1991;1(1):17–24. 10.1016/1050-1738(91)90054-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rezkalla SH, Holmes DR, Jr. Lipid-rich plaque masquerading as a coronary thrombus. Clin Med Res. 2006;4(2):119–122. doi: 10.3121/cmr.4.2.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martha SR, Auld JP, Hash JB, Hong H. Precision health in aging and nursing practice. J Gerontol Nurs. 2020;46(3):3–6. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20200129-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]