Abstract

Background:

In total pancreatectomy with islet auto-transplantation, successful diabetes outcomes are limited by islet loss from the instant blood mediated inflammatory response. We hypothesized that blockade of the inflammatory response with either etanercept or alpha-1-antitrypsin would improve islet function and insulin independence.

Methods:

We randomized 43 participants to receive A1AT (90 mg/kg x 6 doses; n=13), or etanercept (50 mg then 25 mg x 5 doses, n=14), or standard care (n=16), aiming to reduce detrimental effects of innate inflammation on early islet survival. Islet graft function was assessed using mixed meal tolerance testing, intravenous glucose tolerance testing, glucose-potentiated arginine-induced insulin secretion studies, HbA1c, and insulin dose 3 months and 1 year post-TPIAT.

Results:

We observed the most robust acute insulin response (AIRglu) and acute C-peptide response to glucose (ACRglu) at 3 months after TPIAT in the etanercept-treated group (p≤0.02), but no differences in other efficacy measures. The groups did not differ overall at 1 year but when adjusted by sex, there was a trend towards a sex-specific treatment effect in females (AIRglu p=0.05, ACRglu p=0.06), with insulin secretion measures highest in A1AT-treated females.

Conclusion:

Our randomized trial supports a potential role for etanercept in optimizing early islet engraftment but it is unclear whether this benefit is sustained. Further studies are needed to evaluate possible sex-specific responses to either treatment.

Keywords: Chronic pancreatitis, Cytokines, Diabetes, Islet autotransplantation, TPIAT

1-. Introduction:

Chronic pancreatitis is a potentially incapacitating disease that affects as many as 1 in 2,500 persons.1 While medical management and endoscopic procedures are considered first-line therapy, total pancreatectomy with islet autotransplantation (TPIAT) may be performed for severe, chronic pancreatitis or recurrent acute pancreatitis refractory to medical and endoscopic therapies.2,3 Although TPIAT reduces pain and improves patients’ quality of life for most recipients, its success is limited by high prevalence of postsurgical diabetes. Around 70% of patients require supplemental exogenous insulin lifelong after TPIAT.4 Islets are subject to the stress of islet isolation and intraportal infusion; following TPIAT, islets must engraft in the liver and establish a vascular supply. The greater the functional islet mass engrafted, the lower the risk of post-operative diabetes.3,5,6-8

Factors contributing to islet loss include hyperglycemia, hypoxic injury, and inflammatory damage sustained in the early post-transplant period known as the instant blood-mediated inflammatory response (IBMIR).9 Even with optimal glycemic control, beta cell apoptosis is common during the first month post-transplant.10 Cytokine-mediated islet damage resulting from the inflammatory response to islet infusion is a major contributor to islet loss during the perioperative and islet engraftment period.11-17 Blocking the inflammatory component of IBMIR has thus been an appealing target for improving islet auto-transplant outcomes.

Etanercept, a TNFα inhibitor, is a dimeric fusion protein containing an extracellular ligand-binding portion of the TNF receptor linked to the Fc portion of human IgG. Etanercept functions by binding TNFα, thus preventing its interaction with the TNFα receptor. Etanercept therapy prolonged islet allograft survival in murine models18 and has been commonly administered as part of induction immunosuppression in clinical trials of alloislet transplantation for type 1 diabetic recipients, resulting in improved insulin independence rates up to 5 years after transplantation.19 Non-randomized retrospective clinical data in TPIAT patients treated with etanercept and anakira suggested better glycemic outcomes, but was limited by use of historical controls.20

Alpha-1-antitrypsin (A1AT) is a serine protease inhibitor. A1AT inhibits the enzymatic activity of neutrophil elastase, thrombin, cathepsin G, proteinase 3, trypsin, and chymotrypsin. A1AT downregulates inflammatory cytokines including TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8. It also inhibits complement activation and reduces cellular infiltrates, all of which mediate beta cell damage post-transplant.21,22 Streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice treated with human A1AT exhibit superior islet allograft survival in a dose-dependent fashion, and superior syngeneic islet transplant survival with a marginal mass transplanted.23,24 These results were replicated in non-human primates receiving marginal mass islet autografts infused intraportally following subtotal pancreatectomy and streptozotocin treatment.25 In vitro data showed that beta cell apoptosis was reduced in A1AT-treated versus untreated cultured human islets exposed to TNFα.26

We hypothesized that blockade of the innate inflammatory response with either alpha-1-antitrypsin or etanercept administered perioperatively in patients undergoing TPIAT would improve islet function and insulin independence. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a pilot study in which we randomized 43 nondiabetic TPIAT recipients at our institution to receive either etanercept or alpha-1 antitrypsin versus standard care in the peri-infusion period after islet auto-transplantation. This study's aim was to determine if one or both interventions showed enough improvement of islet engraftment and function to support larger, definitive double-blinded placebo trials.

2-. Materials and methods:

2.1. Participants:

Adult patients 18 to 68 years old who were scheduled for TPIAT at the University of Minnesota (UMN) from 12/2016 through 3/2020 were eligible. All patients who are approved for TPIAT at UMN are reviewed by a multi-disciplinary committee to confirm the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis and suitability for surgery as previously described.27 Patients were excluded for pre-existing diabetes or other medical contraindications (see supplemental table 1).

Informed consent was obtained from all participants before screening. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of Minnesota's Institutional Review Board. This study was performed under an Investigational New Drug Application (IND #119828) from the Food and Drug Administration and was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT#02713997).

2.2. Surgical and islet isolation procedure:

Participants underwent total pancreatectomy with partial duodenectomy, splenectomy, cholecystectomy, and roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy. Islet cells were isolated by enzymatic digestion with collagenase followed by mechanical disruption using the semi-automated method of Ricordi, and then were infused into the portal vein of the liver. In cases of elevated portal pressures, a portion of the islets were infused elsewhere, mostly in the peritoneal cavity.3 Heparin was administered at the time of islet infusion as a 70 unit/kg bolus, 35 u/kg in the islet prep and 35 u/kg given to the patient, and then low dose heparin IV or SQ (enoxaparin) was continued for 1 week after the transplantation. Islet mass is expressed as islet equivalents (IEQ) or IEQ per kilogram recipient body weight (IEQ/kg), which is the islet mass standardized to an islet size of 150 μm, consistent with the islet literature. We also assessed islet number (IN) and IN/kg as a measure of the total number of islets without adjusting for islet volume.

2.3. Treatment provided:

Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to A1AT, or etanercept, or standard care. Alpha-1 antitrypsin (Aralast NP) was administered intravenously at a dose of 90 mg/kg, with the first dose administered 1 day before surgery and subsequent doses on days 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 after infusion. Etanercept was given at a dose of 50 mg subcutaneously on day 0 (pre-operatively), and 25 mg subcutaneously on days 3, 7, 10, 14, 21.

Randomization was stratified on BMI (< or ≥27 kg/m2). The investigational pharmacist dispensed study medication according to a randomization schedule provided by the biostatistician. Because the drugs are administered intravenously and subcutaneously, this pilot study was not blinded.

2.4. Study visits and assessments:

Participants had study visits before surgery (“Baseline”) and at 3 months and at 1 year after TPIAT. At each visit, participants underwent comprehensive metabolic testing with mixed meal tolerance testing (MMTT), intravenous glucose tolerance testing (IVGTT), and glucose-potentiated arginine-induced insulin secretion (GPAIS) studies as described below. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level was also obtained. Efficacy of islet graft function was assessed based on metabolic testing measures, HbA1c, insulin use and insulin dose. Also, blinded continuous glucose monitoring (iPro2, Medtronic) data were collected for 6 days following the 3 month and 1 year visits to assess mean glucose, standard deviation, and percent of time in hypo- and hyperglycemia.

Adverse events (AEs) were assessed by telephone calls between visits and at each follow-up visit.

All adverse events regardless of severity were recorded for all participants from day 0 to the day 90 visit. Because patients were only exposed to investigational medication treatment for the first 3-4 weeks post operatively, from the 3 month to the 1 year visit only severe AE’s were collected.

Mixed meal tolerance tests

For MMTT, glucose and C-peptide levels were drawn at time 0, 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes. Participants consumed Boost HP (high protein) 6 cc/kg (maximum 360 cc) within 5 minutes after the time 0 blood draw. Area under the curve for glucose (AUC glucose) and C-peptide (AUC C-peptide) were calculated using the trapezoidal rule including baseline.

Intravenous glucose tolerance testing

The IVGTT is performed by administering a bolus of 0.3 grams/kg of dextrose at time 0, and insulin, C-peptide, and glucose are sampled at times −10, −5, −1, and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 10 minutes. The AUC for the 10-minute insulin or C-peptide values minus baseline are used to calculate the acute insulin response to glucose (AIRglu) and acute C-peptide response to glucose (ACRglu) respectively.

Glucose-potentiated arginine-induced insulin secretion

GPAIS was performed following the IVGTT. For this test, a 20% dextrose solution was infused starting at +20 minutes after the IVGTT dextrose bolus, and then maintained at a variable rate to target blood glucose ~230 mg/dL until completion of the test. Glucose levels were drawn and measured by bedside autoanalyzer every 5 minutes to maintain glucose in target range. At +60 minutes, following a minimum of 30 minutes at target blood glucose (~230 mg/dL), baseline samples for glucose, insulin, and C-peptide were drawn (three samples over 5 minutes), a bolus of 5 grams arginine was administered, and samples for glucose, insulin, and C-peptide were obtained at 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 10 minutes after the arginine bolus. Results were used to calculate the glucose-potentiated acute insulin response to arginine (AIRpot) and the glucose-potentiated acute C-peptide response to arginine (ACRpot) as surrogate markers for islet mass.

2.5. Statistical analysis:

We chose a sample size of 45 randomized participants to give 80% power to detect a difference between any two groups of at least 1.06 × (within-group standard deviation of the outcome). Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, we terminated enrollment early but at near goal for this pilot, with 43 participants.

Data collected at the 3 month and 1 year visits were analyzed separately; for each visit, the various outcomes were analyzed separately. We present group comparisons using unadjusted one-way ANOVA except for two binary outcomes (insulin independence and islet graft function), for which groups were compared using Fisher's exact test. For outcomes analyzed using ANOVA, we also did adjusted analyses using multiple linear regression, adjusting in separate analyses for IEQ/kg, sex, and whether all islets were transplanted intraportally. These adjustments had negligible effects and are not presented, except for sex-adjusted analyses of IVGTT and GPAIS results.

For adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs (SAEs), we considered three outcomes for each person: whether they had any SAEs (yes/no); how many SAEs they had; and how many AEs they had, including SAEs. These outcomes were analyzed separately for five categories of AE -- blood/lymphatics, cardiovascular/vascular, gastrointestinal, infection, and metabolism/nutritional -- and for all categories of AEs combined. To compare groups by the fraction of people who had any SAEs, we used Fisher's exact test; for the two count outcomes, the comparison used Poisson regression with log link and overdispersion parameter estimated by Pearson's chi-squared/DF.

All analyses used JMP (v. 16 Pro, SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC).

3-. Results:

3.1. Participant characteristics:

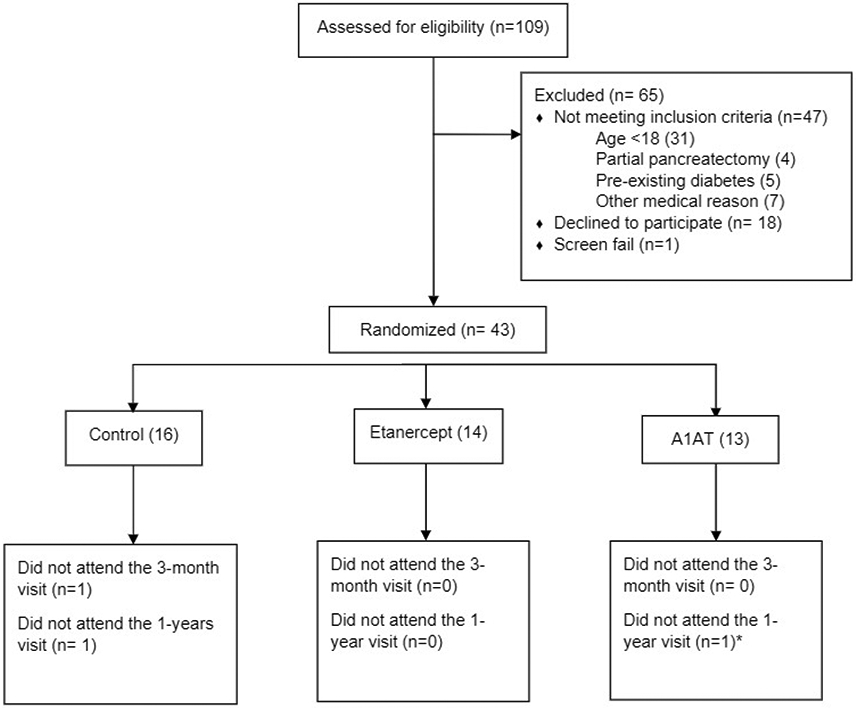

Table 1 summarizes participant and disease characteristics. Forty-four patients were recruited into the study, 1 was excluded for past history of treatment for latent tuberculosis. Forty-three participants were randomized, with 16, 14, and 13 patients in the control, etanercept, and A1AT groups respectively (CONSORT diagram, Figure 1).

Table 1:

Characteristics of the treatment groups, displayed as mean (SD) or N (%)

| Characteristic | All participants |

Control | Etanercept | A1AT | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 43 | 16 | 14 | 13 | |

| Age, years | 38.5 (12.0) | 37.4 (12.1) | 40.8 (12.0) | 37.3 (12.6) | 0.69 |

| Sex (male) | 17 (40%) | 3 (19%) | 4 (29%) | 10 (77%) | 0.004 |

| White | 40 (93%) | 16 (100%) | 11 (79%) | 13 (100%) | 0.053 |

| Hispanic | 4 (9%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (7%) | 2 (15%) | 0.67 |

| BMI Pre-TPIAT (kg/m2) | 24.9 (4.2) | 24.1 (4.5) | 24.7 (3.7) | 26.0 (4.5) | 0.51 |

| Etiology | 0.15 | ||||

| Genetic | 20 (47%) | 7 (44%) | 4 (29%) | 9 (69%) | |

| Obstructive | 9 (21%) | 2 (13%) | 6 (43%) | 1 (8%) | |

| Idiopathic | 10 (23%) | 6 (38%) | 2 (14%) | 2 (15%) | |

| Other | 4 (9%) | 1 (6%) | 2 (14%) | 1 (8%) | |

| Total IEQ (x 105) | 2.38 (1.32) | 2.16 (1.35) | 2.68 (1.33) | 2.33 (1.30) | 0.57 |

| IEQ/kg | 3313 (1987) | 3342 (2396) | 3800 (1899) | 2752 (1455) | 0.40 |

| Total islet number (x 105) | 2.73 (1.43) | 2.80 (1.55) | 3.16 (1.47) | 2.18 (1.13) | 0.21 |

| Islet number / kg body weight | 3851 (2239) | 4329 (2758) | 4485 (1964) | 2581 (1156) | 0.045 |

| Tissue volume (mL) | 14.1 (9.8) | 13.5 (10.3) | 18.5 (10.3) | 10.1 (6.9) | 0.08 |

| All islets intraportal | 31 (72%) | 12 (75%) | 6 (43%) | 13 (100%) | 0.003 |

| Pre-Op labs | |||||

| HbA1c | 5.3 (0.4) | 5.3 (0.4) | 5.2 (0.4) | 5.3 (0.4) | 0.45 |

| ACRglu (ng/mL*min) | 30.8 (18.9) | 25.9 (12.5) | 39.6 (26.8) | 27.0 (10.7) | 0.10 |

| ACRpot (ng/mL*min) | 8.3 (4.5) | 7.2 (4.1) | 9.2 (4.4) | 8.7 (5.3) | 0.48 |

| AIRglu (mU/L*min) | 472 (398) | 382 (270) | 632 (579) | 398 (179) | 0.18 |

| AIRpot (mU/L*min) | 176 (115) | 158 (107) | 186 (133) | 187 (109) | 0.74 |

| AUC glucose (mg/dL*min) | 13771 (2253) | 14039 (2638) | 13497 (1922) | 13757 (2245) | 0.82 |

| AUC C-peptide (ng/mL*min) | 600 (408) | 545 (432) | 730 (502) | 523 (220) | 0.35 |

Figure 1: Flowchart of participant enrollment and treatment assignment.

* An additional 1 participant in the A1AT group attended the 1 year study visit but incidentally developed an emergency small bowel obstruction (not related to study procedures) that limited study assessments to only fasting blood samples and diabetes history.

The three groups were similar in age, BMI, and baseline metabolic testing results. The A1AT group had a much higher proportion of males (P = 0.004). IEQ and IEQ/kg were similar among groups but the A1AT group had a lower islet number (unadjusted for islet size) per kilogram (p=0.045), while the etanercept group was more likely to have islets transplanted outside the liver (p=0.003), probably driven by a trend towards higher tissue volumes infused in this group (p=0.08).

3.2. Islet cell function 3 months post TPIAT:

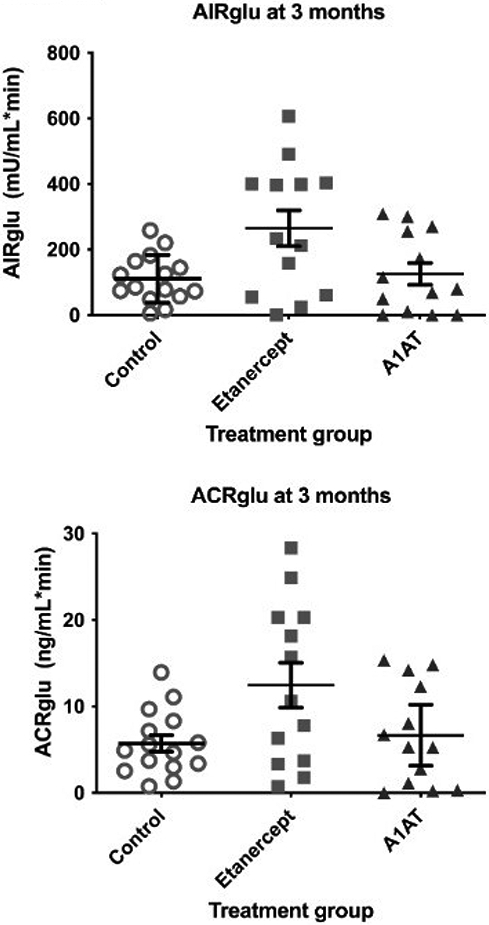

Participants treated with etanercept had significantly higher AIRglu and ACRglu during the IVGTT (P=0.01 and 0.02 respectively), suggesting better first-phase insulin secretion with etanercept treatment (Figure 2). This remained significant even adjusting for IEQ/kg, sex, or whether all islets were transplanted intraportally (p≤0.04 for all). Insulin requirement (units/day) was lower in the etanercept group, though not significantly, averaging 17 units/day compared to 22 units/day in controls and 26 units/day in A1AT group (p=0.42). The three groups did not differ statistically for other 3 month measures including HbA1c, or measures derived from MMTT, GPAIS, and continuous glucose monitoring (Table 2), either with or without adjustment for sex, IEQ/kg and whether all islets were transplanted intraportally.

Figure 2:

IVGTT response at 3 months by treatment assignment. Lines represent mean and standard error.

Table 2:

Measures of glycemic control and islet function 3 months after TPIAT, representing the early postengraftment period. Table entries are average (standard error)

| Metabolic Measure | Control | Etanercept | A1AT | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin use (unit/day) | 22.3 (4.3) | 17.2 (4.6) | 26.0 (4.7) | 0.42 * |

| HbA1c | 6.0 (0.1) | 5.95 (0.1) | 6.3 (0.1) | 0.06 |

| ACRglu (ng/mL*min) | 5.7 (1.7) | 12.4 (1.8) | 6.6 (1.8) | 0.02 |

| AIRglu (mU/L*min) | 110.4 (35.5) | 264.7 (38.1) | 125.6 (38.1) | 0.01 |

| ACRpot (ng/mL*min) | 1.06 (0.26) | 1.52 (0.28) | 1.29 (0.28) | 0.51 |

| AIRpot (mU/L*min) | 24.85 (6.26) | 34.96 (6.99) | 30.43 (6.72) | 0.56 |

| AUC glucose (mg/dL*min) | 18404 (1245) | 18144 (1289) | 19734 (1338) | 0.66 |

| AUC C-peptide (ng/mL*min) | 186.6 (29.44) | 247.6 (30.47) | 171.9 (31.6) | 0.19 |

| Mean glucose on CGM, mg/dL | 124 (5.1) | 128 (5.3) | 131 (5.5) | 0.65 |

| % time < 70 mg/dl | 5.6 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.4) | 0.37 |

| % time >180 mg/dl | 8.3 (3.1) | 9.5 (2.0) | 12.0 (3.3) | 0.72 |

The group comparison was sensitive to a single person in the control group with very high insulin units per day total. The table presents the test from a one-way ANOVA for consistency with the rest of the table, with P = 0.42. A one-way ANOVA of the logarithm of insulin dose, which is strongly indicated by the Box-Cox procedure, has P = 0.12 for the group comparison. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test gives P = 0.04.

3.3. Islet cell function 1 year post TPIAT:

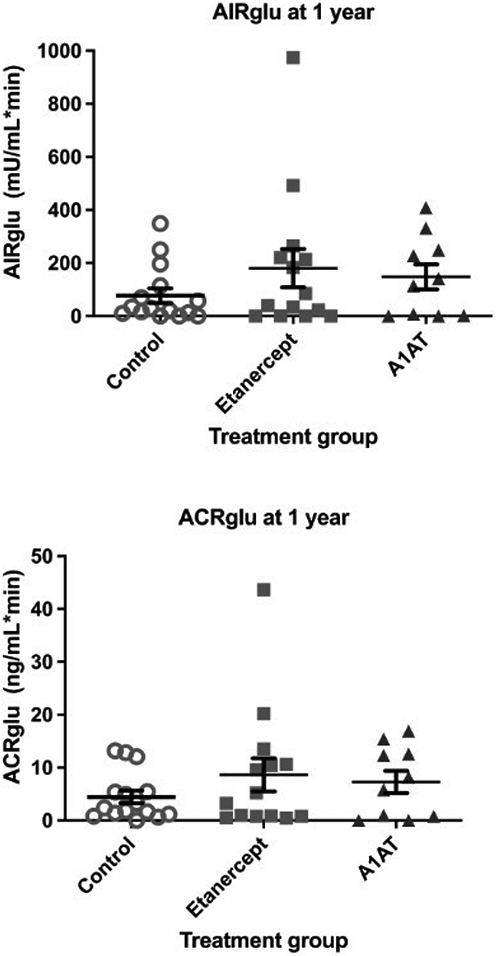

At 1 year follow up, the three treatment groups did not differ significantly for any measure of islet function (Table 3) including no significant differences in the ACRglu and AIRglu (Figure 3). However, when adjusted for sex, the two treatment groups showed a sex-specific difference in insulin secretory responses in females. In particular, females treated with A1AT had the largest insulin secretory responses to IVGTT (P=0.05) and GPAIS (P=0.03) followed by females in the etanercept group, suggesting a potential sex-specific response to treatment (Table 4).

Table 3:

Measures of glycemic control and islet function at 1 year after TPIAT. Table entries are average (standard error) except for "Insulin independent" and "Islet graft function".

| Metabolic Measure | Control | Etanercept | A1AT | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin use (unit/day) | 15.7 (3.8) | 12.0 (4.0) | 24.4 (4.4) | 0.12 |

| Insulin independent, n (%) | 2 (12.5%) | 4 (28.6%) | 2 (15.4%) | 0.61 |

| Islet graft function, n (%)** | 14 (93%) | 14 (100%) | 10 (91%) | 0.73 |

| HbA1c | 6.35 (0.20) | 6.36 (0.22) | 6.23 (0.23) | 0.90 |

| ACRglu (ng/mL*min) | 4.45 (2.15) | 8.63 (2.23) | 7.29 (2.63) | 0.86 |

| AIRglu (mU/L*min) | 77.3 (49.2) | 180.8 (50.9) | 148.1 (60.1) | 0.65 |

| ACRpot (ng/mL*min) | 1.16 (0.32) | 1.44 (0.33) | 1.88 (0.39) | 0.38 |

| AIRpot (mU/L*min) | 28.4 (9.0) | 37.2 (9.4) | 44.6 (11.0) | 0.52 |

| AUC_glucose (mg/dL*min) | 21099 (1558) | 20770 (1612) | 21712 (1819) | 0.93 |

| AUC_C-peptide (ng/mL*min) | 192 (39) | 257 (40) | 223 (45) | 0.77 |

| Mean BG on CGM, mg/dL | 145.9 (9.2) | 130.6 (9.2) | 127.2 (11.6) | 0.53 |

| % time < 70 mg/dl | 1.46 (0.94) | 2.92 (0.94) | 3.12 (1.20) | 0.46 |

| % time >180 mg/dl | 29.0 (6.7) | 15.2 (6.7) | 13.0 (8.6) | 0.60 |

Tests are F-tests from one-way ANOVA except for Insulin independent and Islet graft function, which use two-sided Fisher's exact test.

3 participants had missing data, so n = 15, 14, and 11 for Control, Etanercept, and A1AT respectively.

Figure 3:

IVGTT response at 1 year by treatment assignment. Lines represent mean and standard error.

Table 4:

Measures of glycemic control and islet function at 1 year after TPIAT after adjusting to sex. Table entries are average (standard error)

| Metabolic Measure | Controls | Etanercept | A1AT | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACRglu (ng/mL*min) | 1.4 (2.3) | 6.9 (2.2) | 9.8 (2.6) | 0.066 |

| AIRglu (mU/L*min) | 7.2 (52.2) | 139.8 (49.3) | 205.5 (59.4) | 0.050 |

| ACRpot (ng/mL*min) | 0.68 (0.3) | 1.16 (0.3) | 2.28 (0.4) | 0.023 |

| AIRpot (mU/L*min) | 14.1 (9.3) | 28.8 (8.8) | 56.4 (10.6) | 0.033 |

3.4. Safety:

All participants had >1 adverse event (severe or non-severe), but the number of adverse events per participant was similar in the three treatment groups in the first 3 months after surgery (P= 0.67; average (SE) number of AE+SAEs were 7.3 (0.8), 7.5 (0.9), 6.5 (0.9) for Control, Etanercept, A1AT respectively). Most AEs were known risks of TPIAT surgery and deemed unlikely related to study treatment. The most frequent system affected was gastrointestinal. Severe adverse events were tracked through the 1 year follow up visit and similarly did not differ between treatment groups in rate of occurrence (P=0.47) or number of events per participant (P=0.22; average (SE) number of SAEs were 0.9 (0.4), 1.7 (0.5), 0.7 (0.5) for Control, Etanercept, A1AT respectively).

4-. Discussion:

TPIAT remains an important treatment for patients suffering from intractable chronic or recurrent acute pancreatitis. Although most patients have islet graft function, as evidenced by C-peptide secretion, only a minority have sufficient function to wean entirely off insulin after TPIAT. Autologous islet grafts are damaged by hypoxic, ischemic, and inflammatory insults leading to islet loss in the early post-operative period, likely compromising long-term TPIAT success. Drugs that may reduce cytokine-mediated islet damage and reduce beta cell death following TPIAT thus have appeal for improving peri-transplant islet survival. Based on promising preclinical and limited clinical data, we conducted this randomized trial of two agents, etanercept and alpha-1 antitrypsin, aiming to determine if either improves islet engraftment and provides clinical benefit. We observed superior acute insulin and C-peptide responses to intravenous glucose 3 months after TPIAT in etanercept-treated participants, suggesting potentially superior islet engraftment with etanercept, but these benefits were not sustained 1 year after TPIAT. Interestingly, 1 year after TPIAT, our data suggest a sex-specific response to treatment, particularly for females treated with A1AT, but this finding requires conformation in a larger study.

We selected two therapies -- etanercept and alpha 1 antitrypsin -- that showed promise in reducing IBMIR-mediated islet loss in pre-clinical studies at the time that our protocol was developed. Etanercept had also been used in non-randomized settings in auto and allo-islet transplantation with some suggestion of benefit, i.e., either reduced inflammation or better islet survival18-20. Although apha-1 antitrypsin had only been studied in animal models, it had quite promising results in improving islet graft survival in autografts in non-human primates23,24,26. These preclinical and non-randomized clinical results were the impetus for our current study.

Our results indicated that patients who received etanercept had better beta cell function 3 months after the IAT, possibly suggesting more rapid and complete islet engraftment compared to the other treatments. Those, in the etanercept group were more likely to have a portion of islets transplanted outside the liver, where islets are less susceptible to IBMIR, potentially reducing benefits derived from blocking IBMIR. However, our results remained significant after adjusting for whether all islets transplanted intra portal or not. Etanercept blocks TNF-α activity and has been associated with superior long-term insulin independence when used with other immunosuppressants for islet allotransplantation for type 1 diabetes patients.28 More recently, while our trial was ongoing, Naziruddin et al20 published retrospective data suggesting that etanercept reduces inflammatory markers and improves surrogate markers of islet function if combined with IL-1 blockade with anakinra, but not when used alone. However, key differences between our study and this prior study are our study's randomized comparison with a control group (vs. historical untreated controls), longer treatment duration (21 vs 10 days), and sophisticated measures of islet graft function (IVGTT, GPAIS, and MMTT). Because our randomized trial studied only drug monotherapy, we cannot eliminate the possibility of more robust or sustained benefit with combined drug therapy.

Our study is the first of alpha-1 antitrypsin in human islet transplant. Earlier studies found superior islet graft survival in both syngeneic rodent and autologous non-human primate models treated with peri-transplant alpha-1 antitrypsin. Our pilot data does not show an obvious generalized benefit with A1AT in TPIAT. However, we identified a potential signal for a treatment-sex interaction, with females treated with A1AT exhibiting superior islet graft function at 1 year. We hypothesize that female patients may respond better to anti-inflammatory drugs compared to males due to immune system differences between the sexes. Testing this hypothesis would require a larger study as the A1AT-treated group included few female participants.

It is plausible that a sex-specific treatment response could be driven by differences between sexes in beta cell or immunologic characteristics. It has been postulated that estradiol protects islets from metabolic injury and even promotes islet engraftment and revascularization in rodent models.29,30 Females may have lower pro-inflammatory cytokine production (at least in the presence of estrogen) and islets may be less susceptible to pro-inflammatory damage in the presence of estradiol.31,32 Thus, there may be mechanistic pathways that explain differential responses to treatment in men and women. We did not, however, stratify randomization on sex in this pilot trial and our conclusions are limited by male predominance in the A1AT group. Furthermore, we did not collect data on endogenous estradiol or menopausal status, which would be necessary to draw conclusions about estradiol-mediated effects specifically.

Both etanercept and A1AT were generally well-tolerated. Although adverse events were common, most were attributable to the TPIAT itself and not to drug therapy. Adverse events and severe adverse events were no more common in either treatment group than in the untreated controls. Thus, we found no safety risk to pursuing either drug as a short-term treatment in TPIAT recipients. However, both medications are expensive, so the downside to using these agents without evidence of clear and robust efficacy is additional medical costs.

This study's TPIAT recipients generally had excellent metabolic control and low insulin needs, highlighting the benefit of a TPIAT procedure. However, first phase insulin response as measured by the AIRglu and ACRglu was more often absent (at or near 0) at 1 year compared to 3 months. The high frequency of absent first phase insulin response at 1 year (Figure 3) suggests islet attrition after the period of islet engraftment. Such long-term islet attrition is not addressed by peri-transplant infusion of anti-inflammatory drugs.

Our study's findings should be interpreted in the context of its design and limitations. Most importantly, this study was designed as a pilot trial and thus has inherently low power, which may have masked a small but true benefit of treatment beyond 3 months. The pilot-study sample size also limited our ability to study potential differences in treatment response by patient sex. The treatments themselves were short-term, limited to 4 weeks after TPIAT, to target the period when IBMIR is active. This was based on the speculated mechanism by which these drugs would block IBMIR, but we cannot eliminate the possibility that sustained use for longer durations may increase benefit. While most participants returned for testing, some data are missing due to missed visits or technical limitations (e.g., lost IV access). The current report has only 1 year follow up, but these study participants will be followed long-term with repeat testing 2-3 years post TPIAT, with assays that permit examination of possible mechanistic markers of treatment effect, including inflammatory cytokines and beta cell death markers. We studied a single dose for each drug based on the existing literature, and cannot eliminate the possibility of greater benefit with different dosing, treatment durations, or combination therapies.

In conclusion, this pilot study found modest benefits in the insulin response and acute C-peptide response to glucose 3 months after TPIAT when etanercept was administered but it was unclear if this benefit was sustained long-term. There may be a sex-specific response to anti-inflammatory treatment, with females on alpha-1 antitrypsin exhibiting the most robust insulin secretion 1 year after TPIAT. However, due to this preliminary study's small sample size, further investigation will be needed to confirm this finding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

Funding:

This study was funded by the National Institute of Health. Grant number R01DK109914 (PI Bellin). This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR002494. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Abbreviations:

- A1AT

Alpha 1 antitrypsin

- ACRglu

Acute C-peptide response to glucose

- ACRpot

Glucose-potentiated acute C-peptide response to arginine

- AE

Adverse event

- AIRglu

Acute insulin response to glucose

- AIRpot

Glucose-potentiated acute insulin response to arginine

- AUC

Area under the curve

- BMI

Body mass index

- GPAIS

Glucose-potentiated arginine-induced insulin secretion

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- IEQ

Islet equivalent

- IEQ/KG

Islet equivalent per kilogram body weight

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- IL-6

Interleukin 6

- IL-8

Interleukin 8

- IVGTT

intravenous glucose tolerance tests

- MMTT

Mixed meal tolerance test

- T1D

Type 1 diabetes

- TNF α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TPIAT

Total pancreatectomy with islet auto-transplantation

Footnotes

Disclosure: MDB discloses support from Insulet (DSMB membership), Viaycte (research support), and Dexcom (research support).

Clinical Trial Notation: This study was performed under an Investigational New Drug Application (IND #119828) from the Food and Drug Administration and was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT#02713997).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data availability statement:

Data are available upon reasonable request to the authors.

References

- 1.Yadav D, Timmons L, Benson JT, Dierkhising RA, Chari ST. Incidence, prevalence, and survival of chronic pancreatitis: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. Dec 2011;106(12):2192–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellin MD, Balamurugan AN, Pruett TL, Sutherland DE. No islets left behind: islet autotransplantation for surgery-induced diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. Oct 2012;12(5):580–6. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0296-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutherland DE, Radosevich DM, Bellin MD, et al. Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. Apr 2012;214(4):409–24; discussion 424-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howes N, Lerch MM, Greenhalf W, et al. Clinical and genetic characteristics of hereditary pancreatitis in Europe. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Mar 2004;2(3):252–61. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00013-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blondet JJ, Carlson AM, Kobayashi T, et al. The role of total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. Surg Clin North Am. Dec 2007;87(6):1477–501, x. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutherland DE, Gruessner AC, Carlson AM, et al. Islet autotransplant outcomes after total pancreatectomy: a contrast to islet allograft outcomes. Transplantation. Dec 27 2008;86(12):1799–802. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31819143ec [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellin MD, Sutherland DE. Pediatric islet autotransplantation: indication, technique, and outcome. Curr Diab Rep. Oct 2010;10(5):326–31. doi: 10.1007/s11892-010-0140-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmad SA, Lowy AM, Wray CJ, et al. Factors associated with insulin and narcotic independence after islet autotransplantation in patients with severe chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. Nov 2005;201(5):680–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.06.268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naziruddin B, Iwahashi S, Kanak MA, Takita M, Itoh T, Levy MF. Evidence for instant blood-mediated inflammatory reaction in clinical autologous islet transplantation. Am J Transplant. Feb 2014;14(2):428–37. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itoh T, Iwahashi S, Kanak MA, et al. Elevation of high-mobility group box 1 after clinical autologous islet transplantation and its inverse correlation with outcomes. Cell Transplant. Feb 2014;23(2):153–65. doi: 10.3727/096368912x658980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biarnés M, Montolio M, Nacher V, Raurell M, Soler J, Montanya E. Beta-cell death and mass in syngeneically transplanted islets exposed to short- and long-term hyperglycemia. Diabetes. Jan 2002;51(1):66–72. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.1.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boker A, Rothenberg L, Hernandez C, Kenyon NS, Ricordi C, Alejandro R. Human islet transplantation: update. World J Surg. Apr 2001;25(4):481–6. doi: 10.1007/s002680020341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matarazzo M, Giardina MG, Guardasole V, et al. Islet transplantation under the kidney capsule corrects the defects in glycogen metabolism in both liver and muscle of streptozocin-diabetic rats. Cell Transplant. 2002;11(2):103–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabinovitch A, Sumoski W, Rajotte RV, Warnock GL. Cytotoxic effects of cytokines on human pancreatic islet cells in monolayer culture. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Jul 1990;71(1):152–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-1-152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanley S, Liu S, Lipsett M, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by human islets leads to postisolation cell death. Transplantation. Sep 27 2006;82(6):813–8. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000234787.05789.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oancea AR, Omori K, Orr C, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers in the blood and pancreatic tissue of organ donors that predict human islet isolation success and function. Islets. 2020;12(1):9–19. doi: 10.1080/19382014.2019.1696127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montolio M, Téllez N, Soler J, Montanya E. Role of blood glucose in cytokine gene expression in early syngeneic islet transplantation. Cell Transplant. 2007;16(5):517–25. doi: 10.3727/000000007783464920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angaswamy N, Fukami N, Tiriveedhi V, Cianciolo GJ, Mohanakumar T. LMP-420, a small molecular inhibitor of TNF-α, prolongs islet allograft survival by induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling-1: synergistic effect with cyclosporin-A. Cell Transplant. 2012;21(6):1285–96. doi: 10.3727/096368911x637371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellin MD, Barton FB, Heitman A, et al. Potent induction immunotherapy promotes long-term insulin independence after islet transplantation in type 1 diabetes. Am J Transplant. Jun 2012;12(6):1576–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03977.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naziruddin B, Kanak MA, Chang CA, et al. Improved outcomes of islet autotransplant after total pancreatectomy by combined blockade of IL-1β and TNFα. Am J Transplant. Sep 2018;18(9):2322–2329. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang B, Lu Y, Campbell-Thompson M, et al. Alpha1-antitrypsin protects beta-cells from apoptosis. Diabetes. May 2007;56(5):1316–23. doi: 10.2337/db06-1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shahaf G, Moser H, Ozeri E, Mizrahi M, Abecassis A, Lewis EC. α-1-antitrypsin gene delivery reduces inflammation, increases T-regulatory cell population size and prevents islet allograft rejection. Mol Med. Sep-Oct 2011;17(9-10):1000–11. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis EC, Shapiro L, Bowers OJ, Dinarello CA. Alpha1-antitrypsin monotherapy prolongs islet allograft survival in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Aug 23 2005;102(34):12153–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505579102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis EC, Mizrahi M, Toledano M, et al. alpha1-Antitrypsin monotherapy induces immune tolerance during islet allograft transplantation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Oct 21 2008;105(42):16236–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807627105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koulmanda M, Sampathkumar RS, Bhasin M, et al. Prevention of nonimmunologic loss of transplanted islets in monkeys. Am J Transplant. Jul 2014;14(7):1543–51. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalis M, Kumar R, Janciauskiene S, Salehi A, Cilio CM. α 1-antitrypsin enhances insulin secretion and prevents cytokine-mediated apoptosis in pancreatic β-cells. Islets. May-Jun 2010;2(3):185–9. doi: 10.4161/isl.2.3.11654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellin MD, Beilman GJ, Dunn TB, et al. Sitagliptin Treatment After Total Pancreatectomy With Islet Autotransplantation: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Am J Transplant. Feb 2017;17(2):443–450. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellin MD, Kandaswamy R, Parkey J, et al. Prolonged insulin independence after islet allotransplants in recipients with type 1 diabetes. Am J Transplant. Nov 2008;8(11):2463–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02404.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saber N, Bruin JE, O'Dwyer S, Schuster H, Rezania A, Kieffer TJ. Sex Differences in Maturation of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived β Cells in Mice. Endocrinology. Apr 1 2018;159(4):1827–1841. doi: 10.1210/en.2018-00048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu S, Kilic G, Meyers MS, et al. Oestrogens improve human pancreatic islet transplantation in a mouse model of insulin deficient diabetes. Diabetologia. Feb 2013;56(2):370–81. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2764-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Contreras JL, Smyth CA, Bilbao G, Young CJ, Thompson JA, Eckhoff DE. 17beta-Estradiol protects isolated human pancreatic islets against proinflammatory cytokine-induced cell death: molecular mechanisms and islet functionality. Transplantation. Nov 15 2002;74(9):1252–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200211150-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gannon M, Kulkarni RN, Tse HM, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Sex differences underlying pancreatic islet biology and its dysfunction. Mol Metab. Sep 2018;15:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the authors.