Abstract

A rare missense APOE variant (L28P; APOE*4Pittsburgh), which is present only in populations with European ancestry, has been reported to be a risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). However, due to the complete linkage disequilibrium of L28P with APOE*4 (C112R), its independent genetic association is uncertain. The original association study implicating L28P with LOAD risk was carried out in a relatively small sample size. In the current study, we have re-evaluated this association in a large case-control sample of 15,762 White U.S. subjects and investigated its independent effect in APOE 3/4 subjects, as L28P has been observed only in the heterozygous state of APOE*4 carriers and 3/4 is the most common genotype containing the APOE*4 allele. The heterozygous carrier frequency of L28P, all with APOE*4, was about 3-fold higher in AD cases than in cognitively intact controls (0.845% vs 0.277%). The age- and sex-adjusted meta-analysis odds ratio (OR) was 2.87 (95% CI: 1.34 – 6.13; p= 0.0066). Among APOE 3/4 subjects, age- and sex-adjusted meta-analysis OR was 1.53 (95% CI: 0.70 – 3.36; p= 0.28), indicating its effect was independent of APOE*4. The lack of statistical significance appears mainly due to the low power of 4,138 subjects with the 3/4 genotype (12% power at α= 0.05) compared to the required sample of 139,088 subjects with the 3/4 genotype to detect an OR of 1.5 at α= 0.05 and 80% power. Our data suggesting that L28P has an independent genetic effect on AD risk is reinforced by earlier experimental findings showing that this mutation leads to significant structural and conformational changes in the ApoE4 molecule and can induce functional defects associated with neuronal Aβ42 accumulation and oxidative stress. Additional functional studies in cell-based systems and animal models will help to delineate its functional significance in the etiology of AD.

Keywords: Late-onset Alzheimer’s Disease, Genetic Risk Factor, APOE, rare variants, rs769452

Introduction

Human apolipoprotein E (ApoE, protein; APOE, gene) plays a pivotal role in cholesterol/lipid transport in the peripheral and central nervous systems [1]. The most common APOE polymorphism due to missense mutations at codons 112 and 158 results in three allelic forms, of which APOE*4 is associated with an increased risk and earlier age-at-onset (AAO) of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), while APOE*2 is associated with decreased risk and later AAO of AD as compared to the wild type APOE*3 [2–6]. Since the original discovery of the association between APOE*4 and AD, evidence that APOE alleles differentially influence amyloid and tau pathology, network dysfunction, and neuroinflammation has been identified [7, 8].

In 1999, two groups independently identified a novel and rare missense mutation in the APOE gene [9, 10] in which the leucine residue is replaced by proline at codon 28 (L28P; rs769452). This mutation occurs in complete linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the APOE*4 allele, hence named APOE*4Pittsburgh and APOE*4Freiburg, and it was associated with an elevated risk for AD [9] and coronary artery disease [10]. Since then, this variant has been examined in additional AD case-control samples [11–13], although a consensus as to whether this mutation by itself increases the odds of developing AD is yet to be reached. The main drawbacks of aforementioned studies are the use of relatively limited samples, considering L28P is an ultra-rare variant and would require a very large sample size. The rarity of the L28P mutation, and its complete LD with the APOE*4 allele, makes it nearly impossible to separate its unique contribution from the overwhelming effect of the APOE*4 allele on the risk of developing AD. In the current study, we have re-evaluated this association in a large case-control sample of 15,762 U.S. White subjects and investigated its independent effect among subjects with the APOE 3/4 genotype, as L28P has been observed in the heterozygous state only on the APOE*4–containing chromosome and 3/4 is the most common genotype containing the APOE*4 allele.

Methods

Study Samples

To maximize the sample size for this rare variant study, we used data from 15,762 White AD cases and controls derived from three major cohorts: Alzheimer’s Disease Sequencing Project (ADSP), The Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory (GEM) study, and a cohort comprising three studies at the University of Pittsburgh: the case-control cohort at the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) and two population-based cognitively normal cohorts, the Monongahela Valley Independent Elders Survey (MoVIES) and the Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team (MYHAT). The demographic data on each study sample is presented in Table 1 and their detailed descriptions are given elsewhere [14–18].

Table 1.

Demographic information on the study samples

| Study | ADSP | GEM | Univ Pittsburgh | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD Case | Control | AD Case | Control | AD Case | Control | AD Case | Control | |

| N | 4316 | 5964 | 384 | 2217 | 1690 | 1191 | 6390 | 9372 |

| Mean Age ± SD | 73.7 ± 7.95 | 85.6 ± 4.10 | 79.9 ± 3.64 | 78.3 ± 3.11 | 72.0 ± 8.02 | 77.2 ± 7.79 | 73.6 ± 7.97 | 82.8 ± 5.88 |

| Sex Female (%) | 1973 (45.7%) | 2355 (39.5%) | 181 (47.1%) | 980 (44.2%) | 1077 (63.7%) | 742 (62.3%) | 3231 (50.6%) | 4077 (43.5%) |

| APOE*4 Carrier N (%) | 2201 (51%) | 814 (14%) | 150 (39%) | 461 (21%) | 974 (58%) | 234 (20%) | 3325 (52%) | 1509 (16%) |

Genotyping

Genotypes for the APOE/rs429358 (APOE*4) and APOE/rs7412 (APOE*2) SNPs in the Pittsburgh and GEM samples were determined using TaqMan genotyping assays followed by the determination of traditional six genotypes (2/2, 2/3, 2/4, 3/3, 3/4, 4/4) based on the three-allele APOE polymorphism [6]. The genotype identification of these variants in the ADSP sample were derived directly from the whole-exome sequencing (WES) data [19].

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression was implemented for calculating odds ratios (ORs) and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) while using sex and age as covariates. The ORs were calculated individually for each of the three research studies followed by the meta-analysis. To determine the independent effect of APOE*4Pittsburgh L28P from APOE*4 on AD risk, we examined the distribution of L28P among subjects with the APOE 3/4 genotype, since as detailed above, it has been observed in the heterozygous state only on the APOE*4–containing chromosome and 3/4 is the most common APOE*4 genotype. All statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.6.1 [20] using the R package epitools [21]; meta [22]; and metafor [23]. The power analysis for the current sample size and the required sample size for 80% power were calculated in G*Power 3.1 [24] following the formula in Demidenko [25].

Results and Discussion

We examined a total of 15,762 subjects from three studies (6,390 AD cases and 9,372 controls) for the L28P variant (Table 1). As expected, the frequency of APOE*4 carriers was higher in AD cases than in controls. Genotyping of L28P revealed two genotypes, TT and TC; no example of the rare allele homozygosity (CC) was observed. Table 2 shows the carrier frequency of the TC genotype along with the minor allele frequencies (MAF). Eighty subjects carried the L28P mutation, all with the APOE*4 allele. The L28P carrier frequency was significantly higher in AD cases than controls (0.845% vs 0.277%; P = 1.25E-06). The meta OR was 2.87 (95% CI: 1.34 – 6.13; P = 6.60E-03).

Table 2.

Distribution of L28P (rs769452) Carriers in AD cases and Controls

| Study | ADSP | GEM | Univ Pittsburgh | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD Case | Control | AD Case | Control | AD Case | Control | AD Case | Control | |

| N | 4316 | 5964 | 384 | 2217 | 1690 | 1191 | 6390 | 9372 |

| L28P Carrier N (%) | 29 (0.672%) | 10 (0.168%) | 4 (1.04%) | 9 (0.406%) | 21 (1.243%) | 7 (0.588%) | 54 (0.845%) | 26 (0.277%) |

| MAF % | 0.335% | 0.084% | 0.521% | 0.203% | 0.621% | 0.294% | 0.423% | 0.139% |

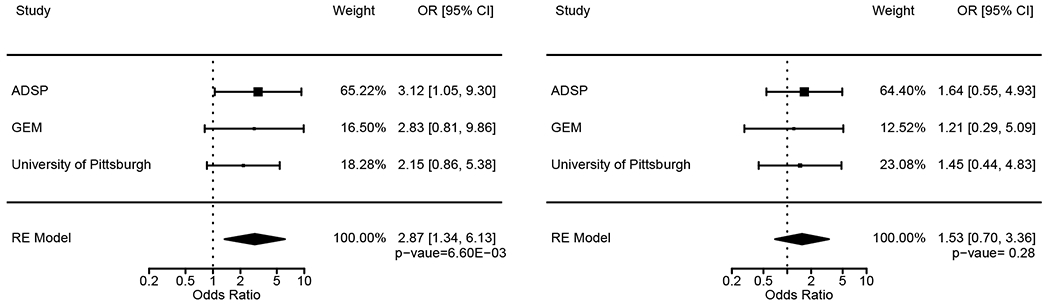

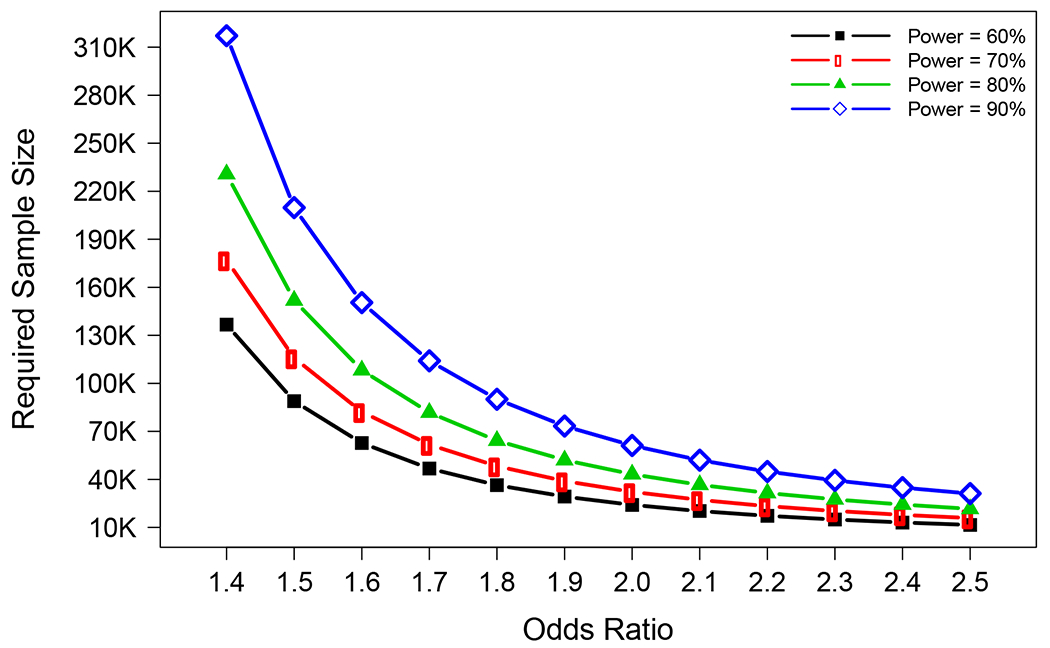

To distinguish the independent effect of L28P from APOE*4 on AD risk, we restricted the analysis among subjects with the APOE 3/4 genotype, as detailed above. Among the 4,834 AD cases and controls with APOE*4 carriers, 85.62% had the 3/4 genotype followed by 4/4 (8.05%) and 2/4 (6.33%) genotypes. Subjects with the APOE 2/4 and 4/4 genotypes were excluded in order to avoid the confounding protective effect of E2 and an extra copy of E4 on L28P. The age- and sex-adjusted meta-analysis OR of L28P among APOE 3/4 was 1.53 (95% CI: 0.70 – 3.36; p = 0.28; Figure 1). The lack of significance is mainly due to the low power of a sample size of 4,138 in the 3/4 genotype (12% power at α = 0.05); the calculated required sample size was 139,088 (Figure 2). Considering that about 25% of the European Whites carry the APOE*4 allele, the total required sample size to detect an OR of 1.5 at α = 0.05 and 80% power was 556,352 (139,088/0.25) European Whites.

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis of L28P in the total sample (left) and among subjects with the APOE 3/4 genotype (right).

Figure 2.

Required sample size for APOE 3/4 genotype individuals with different combinations of the odds ratio and the power (α=0.05).

Even with non-statistically significant p-value, the OR of 1.53 among 3/4 subjects suggests that the effect of L28P on AD risk is independent of APOE*4. This genetic observation is further supported by a comprehensive experimental study in which the L28P mutation was associated with significant structural and conformational changes in the wild type (WT) ApoE4 that resulted in intraneuronal Aβ42 accumulation and oxidative stress [26]. As compared to lipid-free WT ApoE4, lipid-free L28P induced the intracellular accumulation of Aβ42 in SK-N-SH human neuroblastoma cells and mouse primary neurons. Furthermore, lipidated L28P significantly reduced the viability of SK-N-SH cells when compared to lipidated WT ApoE4, which was due to greater cellular oxidative stress induced by L28P than WT ApoE4 [26]. Regardless of its lipidation state, if L28P promotes the in vivo neuronal accumulation of Aβ42 followed by induction of increased oxidative stress and ensuing AD pathogenesis, this would represent a gain of function over the WT ApoE4, that itself does not induce the intracellular accumulation of Aβ42. WT ApoE4 is more susceptible to proteolysis than the other ApoE isoforms (E2 and E3) and ApoE4 fragments have been found in brains of AD patients [27]. In this regard, a specific ApoE4 fragment, ApoE4[Δ(166-299)], has previously been found to promote the cellular uptake of extracellular Aβ42 and resulted in increased oxidative stress [28], similar to the effect of L28P. Since the intraneuronal accumulation of Aβ42 and the resulting persistent oxidative stress are considered early events in the pathogenesis of AD and the naturally occurring L28P mutation is associated with both these events as well as with AD risk, it will be important in future studies to examine the role of L28P in cell-based systems, such as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which can successfully recapitulate the pathology of AD [29, 30] and/or animal models.

In summary, our genetic data among APOE 3/4 subjects suggest that L28P has an effect independent of APOE*4 on AD risk, which is reinforced by earlier experimental findings. Further confirmation of our genetic data in much larger APOE 3/4 subjects would help validate this independent association.

Highlights.

A rare missense APOE (L28P) has been reported to be a risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD).

However, due to the complete linkage disequilibrium of L28P with APOE*4, its independent genetic association is uncertain.

we have re-evaluated the L28P association in 15,762 White U.S. case-control subjects and in 4,139 APOE 3/4 subjects, since APOE 3/4 is the most common genotype containing the APOE*4 allele

Our data suggesting that L28P has an independent genetic effect on LOAD.

Acknowledgements

University of Pittsburgh

The study was supported in part by NIH grants AG041718, AG030653, AG064877, AG066468, AG023651, and AG07562. A subset of samples used in this study were obtained from the National Centralized Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia (NCRAD), which receives government support under a cooperative agreement grant (U24 AG021886) awarded by the NIA. We thank contributors who collected samples used in this study, as well as patients and their families, whose help and participation made this work possible. This publication was made possible by Grant Number U01 AT000162 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

ADSP

The study was supported in part by NIH grants AG041718, AG030653, AG064877, AG005133, AG023651, and AG07562. The Alzheimer’s Disease Sequencing Project (ADSP) is comprised of two Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) genetics consortia and three National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) funded Large Scale Sequencing and Analysis Centers (LSAC). The two AD genetics consortia are the Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium (ADGC) funded by NIA (U01 AG032984), and the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) funded by NIA (R01 AG033193), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), other National Institute of Health (NIH) institutes and other foreign governmental and nongovernmental organizations. The Discovery Phase analysis of sequence data is supported through UF1AG047133 (to Drs. Schellenberg, Farrer, Pericak-Vance, Mayeux, and Haines); U01AG049505 to Dr. Seshadri; U01AG049506 to Dr. Boerwinkle; U01AG049507 to Dr. Wijsman; and U01AG049508 to Dr. Goate and the Discovery Extension Phase analysis is supported through U01AG052411 to Dr. Goate, U01AG052410 to Dr. Pericak-Vance and U01 AG052409 to Drs. Seshadri and Fornage. Data generation and harmonization in the Follow-up Phases is supported by U54AG052427 (to Drs. Schellenberg and Wang).

The ADGC cohorts include: Adult Changes in Thought (ACT), the Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADC), the Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP), the Memory and Aging Project (MAP), Mayo Clinic (MAYO), Mayo Parkinson’s Disease controls, University of Miami, the Multi-Institutional Research in Alzheimer’s Genetic Epidemiology Study (MIRAGE), the National Cell Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease (NCRAD), the National Institute on Aging Late Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Family Study (NIA-LOAD), the Religious Orders Study (ROS), the Texas Alzheimer’s Research and Care Consortium (TARC), Vanderbilt University/Case Western Reserve University (VAN/CWRU), the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP) and the Washington University Sequencing Project (WUSP), the Columbia University Hispanic- Estudio Familiar de Influencia Genetica de Alzheimer (EFIGA), the University of Toronto (UT), and Genetic Differences (GD).

The CHARGE cohorts are supported in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) infrastructure grant HL105756 (Psaty), RC2HL102419 (Boerwinkle) and the neurology working group is supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) R01 grant AG033193. The CHARGE cohorts participating in the ADSP include the following: Austrian Stroke Prevention Study (ASPS), ASPS-Family study, and the Prospective Dementia Registry-Austria (ASPS/PRODEM-Aus), the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), the Erasmus Rucphen Family Study (ERF), the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), and the Rotterdam Study (RS). ASPS is funded by the Austrian Science Fond (FWF) grant number P20545-P05 and P13180 and the Medical University of Graz. The ASPS-Fam is funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) project I904),the EU Joint Programme - Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) in frame of the BRIDGET project (Austria, Ministry of Science) and the Medical University of Graz and the Steiermärkische Krankenanstalten Gesellschaft. PRODEM-Austria is supported by the Austrian Research Promotion agency (FFG) (Project No. 827462) and by the Austrian National Bank (Anniversary Fund, project 15435. ARIC research is carried out as a collaborative study supported by NHLBI contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C). Neurocognitive data in ARIC is collected by U01 2U01HL096812, 2U01HL096814, 2U01HL096899, 2U01HL096902, 2U01HL096917 from the NIH (NHLBI, NINDS, NIA and NIDCD), and with previous brain MRI examinations funded by R01-HL70825 from the NHLBI. CHS research was supported by contracts HHSN268201200036C, HHSN268200800007C, N01HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083, N01HC85086, and grants U01HL080295 and U01HL130114 from the NHLBI with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Additional support was provided by R01AG023629, R01AG15928, and R01AG20098 from the NIA. FHS research is supported by NHLBI contracts N01-HC-25195 and HHSN268201500001I. This study was also supported by additional grants from the NIA (R01s AG054076, AG049607 and AG033040 and NINDS (R01 NS017950). The ERF study as a part of EUROSPAN (European Special Populations Research Network) was supported by European Commission FP6 STRP grant number 018947 (LSHG-CT-2006-01947) and also received funding from the European Community-s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/grant agreement HEALTH-F4-2007-201413 by the European Commission under the programme “Quality of Life and Management of the Living Resources” of 5th Framework Programme (no. QLG2-CT-2002-01254). High-throughput analysis of the ERF data was supported by a joint grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research and the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (NWO-RFBR 047.017.043). The Rotterdam Study is funded by Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (RIDE), the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the Ministry for Health, Welfare and Sports, the European Commission (DG XII), and the municipality of Rotterdam. Genetic data sets are also supported by the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research NWO Investments (175.010.2005.011, 911-03-012), the Genetic Laboratory of the Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus MC, the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (014-93-015; RIDE2), and the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI)/Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Aging (NCHA), project 050-060-810. All studies are grateful to their participants, faculty and staff. The content of these manuscripts is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The four LSACs are: the Human Genome Sequencing Center at the Baylor College of Medicine (U54 HG003273), the Broad Institute Genome Center (U54HG003067), The American Genome Center at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (U01AG057659), and the Washington University Genome Institute (U54HG003079).

Biological samples and associated phenotypic data used in primary data analyses were stored at Study Investigators institutions, and at the National Cell Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease (NCRAD, U24AG021886) at Indiana University funded by NIA. Associated Phenotypic Data used in primary and secondary data analyses were provided by Study Investigators, the NIA funded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs), and the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC, U01AG016976) and the National Institute on Aging Genetics of Alzheimer’s Disease Data Storage Site (NIAGADS, U24AG041689) at the University of Pennsylvania, funded by NIA, and at the Database for Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) funded by NIH. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of health, National Library of Medicine. Contributors to the Genetic Analysis Data included Study Investigators on projects that were individually funded by NIA, and other NIH institutes, and by private U.S. organizations, or foreign governmental or nongovernmental organizations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- 1.Mahley RW, Apolipoprotein E: from cardiovascular disease to neurodegenerative disorders. J Mol Med (Berl), 2016. 94(7): p. 739–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamboh MI, Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Biol, 1995. 67(2): p. 195–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrer LA, et al. , Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. JAMA, 1997. 278(16): p. 1349–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamboh MI, et al. , Genome-wide association analysis of age-at-onset in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry, 2012. 17(12): p. 1340–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naj AC, et al. , Effects of multiple genetic loci on age at onset in late-onset Alzheimer disease: a genome-wide association study. JAMA Neurol, 2014. 71(11): p. 1394–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamboh MI, Genomics and Functional Genomics of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics, 2022. 19(1): p. 152–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamazaki Y, et al. , Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: pathobiology and targeting strategies. Nat Rev Neurol, 2019. 15(9): p. 501–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koutsodendris N, et al. , Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer’s Disease: Findings, Hypotheses, and Potential Mechanisms. Annu Rev Pathol, 2022. 17: p. 73–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamboh MI, et al. , A novel mutation in the apolipoprotein E gene (APOE*4 Pittsburgh) is associated with the risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett, 1999. 263(2-3): p. 129–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orth M, et al. , Effects of a frequent apolipoprotein E isoform, ApoE4Freiburg (Leu28-->Pro), on lipoproteins and the prevalence of coronary artery disease in whites. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 1999. 19(5): p. 1306–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scacchi R, et al. , Screening of two mutations at exon 3 of the apolipoprotein E gene (sites 28 and 42) in a sample of patients with sporadic late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging, 2003. 24(2): p. 339–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medway CW, et al. , ApoE variant p.V236E is associated with markedly reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener, 2014. 9: p. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baron M, et al. , Apolipoprotein E Pittsburgh variant is not associated with the risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease in a Spanish population. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet, 2003. 120B(1): p. 121–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeKosky ST, et al. , The Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory (GEM) study: design and baseline data of a randomized trial of Ginkgo biloba extract in prevention of dementia. Contemp Clin Trials, 2006. 27(3): p. 238–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beecham GW, et al. , The Alzheimer’s Disease Sequencing Project: Study design and sample selection. Neurol Genet, 2017. 3(5): p. e194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamboh MI, et al. , Genome-wide association study of Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Psychiatry, 2012. 2: p. e117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganguli M, et al. , Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment by multiple classifications: The Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team (MYHAT) project. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2010. 18(8): p. 674–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganguli M, et al. , Ten-year incidence of dementia in a rural elderly US community population: the MoVIES Project. Neurology, 2000. 54(5): p. 1109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan KH, et al. , Whole-Exome Sequencing Analysis of Alzheimer’s Disease in Non-APOE*4 Carriers. J Alzheimers Dis, 2020. 76(4): p. 1553–1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Team, R.C., R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aragon TJ, epitools: Epidemiology Tools. R package version 0.5-10. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarzer G, meta: An R package for meta-analysis. R News, 2007. 7(3): p. 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lortie CJ and Filazzola A, A contrast of meta and metafor packages for meta-analyses in R. Ecol Evol, 2020. 10(20): p. 10916–10921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faul F, et al. , G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods, 2007. 39(2): p. 175–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demidenko E, Sample size determination for logistic regression revisited. Stat Med, 2007. 26(18): p. 3385–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Argyri L, et al. , Molecular basis for increased risk for late-onset Alzheimer disease due to the naturally occurring L28P mutation in apolipoprotein E4. J Biol Chem, 2014. 289(18): p. 12931–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Y, et al. , Apolipoprotein E fragments present in Alzheimer’s disease brains induce neurofibrillary tangle-like intracellular inclusions in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2001. 98(15): p. 8838–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dafnis I, et al. , An apolipoprotein E4 fragment can promote intracellular accumulation of amyloid peptide beta 42. J Neurochem, 2010. 115(4): p. 873–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lagomarsino VN, et al. , Stem cell-derived neurons reflect features of protein networks, neuropathology, and cognitive outcome of their aged human donors. Neuron, 2021. 109(21): p. 3402–3420 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao J, et al. , APOE4 exacerbates synapse loss and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease patient iPSC-derived cerebral organoids. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]