Abstract

An interdisciplinary plenary session entitled “Rethinking and Rehashing Delirium” was held during the 2021 Annual Meeting of the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry to facilitate dialogue on the prevalent approach to delirium. Panel members included a psychiatrist, neurointensivist, and critical care specialist, and attendee comments were solicited with the goal of developing a statement. Discussion was focused on a reappraisal of delirium, and in particular its disparate terminology and history in relation to acute encephalopathy.

The authors endorse a recent joint position statement that describes acute encephalopathy as a rapidly evolving (< 4 weeks) pathobiological brain process that presents as subsyndromal delirium, delirium, or coma, and suggest the following points of refinement: (1) to suggest that “delirium disorder” describe the diagnostic construct including its syndrome, precipitant(s), and unique pathophysiology, (2) to restrict the term “delirium” to describing the clinical syndrome encountered at the bedside, (3) to clarify that the disfavored term “altered mental status” may occasionally be an appropriate preliminary designation where the diagnosis cannot yet be specified further, and (4) to provide rationale for rejecting the terms acute brain injury, failure, or dysfunction.

The final common pathway of delirium appears to involve higher-level brain network dysfunction, but there are many insults that can disrupt functional connectivity. We propose that future delirium classification systems should seek to characterize the unique pathophysiological disturbances (“endotypes”) that underlie delirium and delirium’s individual neuropsychiatric symptoms. We provide provisional means of classification, in hopes that novel subtypes might lead to specific intervention to improve patient experience and outcomes.

This paper concludes by considering future directions for the field. Key areas of opportunity include interdisciplinary initiatives to harmonize efforts across specialties and settings, enhance underrepresented groups in research, integration of delirium and encephalopathy in coding, development of relevant quality and safety measures, and exploration of opportunities for translational science.

Keywords: delirium disorder, acute encephalopathy, pathophysiology, neuropsychiatric symptoms, altered mental status, subtypes

Background

Roughly a third of hospitalized older adults experience delirium (1), including more than 50% of critically ill adults, up to 85% of palliative care patients at end of life (2), and nearly 90% of coma survivors (3). Delirium impacts more than 7 million older adults in the U.S. each year. The annual costs attributable to delirium in the U.S. are $40–164 billion (4); for context, the global cost of dementia is about US $1 trillion annually (5). Delirium after major surgery alone is associated with an additional $44 thousand in care costs per patient over the first postoperative year (6). Delirium confers a higher risk of all-cause dementia and mortality, and the experience of delirium often causes considerable personal distress to patients (2).

Despite the immense public health impact of delirium, its clinical detection remains limited, efficacious treatments are lacking, and no intervention has been shown to prevent its poor associated outcomes (7). It also remains unclear to what extent the relationship between delirium and its poor outcomes might be epiphenomenal and whether preventing or treating the syndrome of delirium improves these outcomes. We believe these failures of clinical practice call for a reevaluation of the prevalent model of delirium.

Recently, authors (including some of this paper) have begun to reconceptualize delirium—positing that delirium has physiologically distinct types beyond the traditional motoric subtypes (i.e., hyperactive, hypoactive, mixed level of activity) (8-10). A recent position statement on the nomenclature of delirium and acute encephalopathy (11) makes clear the need to integrate these constructs (12).

In the context of these open questions regarding how best to conceptualize delirium and its relationship to acute encephalopathy, the Chair of the 2021 Annual Meeting of the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry assembled a panel of delirium experts to reappraise delirium (13). The aims were to facilitate interdisciplinary dialogue among delirium experts across medical specialties, to solicit input from attendees, and to develop the session content into a manuscript.

Methods and process description

The virtual plenary session was developed by LR and moderated by CC. JM introduced the session and provided context for the discussion. The three panelists—MO, AS, and EWE—each provided brief prepared remarks, and this was followed by a question-and-answer session that comprised more than half the session. Written comments by the audience were encouraged. In preparation for the session a manuscript exploring the nuances of delirium and acute encephalopathy was circulated among session contributors, and common themes were discussed and established beforehand (14).

After the session, 59 deidentified attendee comments were reviewed and are included below. Comments that contained questions pertaining to multiple topics were divided based on content. One comment was divided into three topics and another nine comments were divided into two topics each, yielding 70 unique questions (see Supplement). These comments were then organized by content, and responses were drafted. Once all presenters had contributed to these responses they were then adapted into the following sections of this statement.

I. Terminology of delirium and acute encephalopathy

The terms delirium and acute encephalopathy describe overlapping clinical constructs yet have largely distinct traditions and bodies of literature with limited crosstalk between them (11). A recent interdisciplinary position statement recommends that the term acute encephalopathy be used to describe the underlying brain pathobiology that presents clinically as subsyndromal delirium, delirium, or coma (see Figure 1) (11). As a result, identifying the syndrome of delirium—i.e., the mental state encountered at the bedside—is incomplete without describing its underlying pathophysiology (12). Conversely, acute encephalopathy would not be diagnosed without first identifying a delirium-spectrum mental state—its telltale clinical presentation.

Figure 1: Spectrum of mental states caused by acute encephalopathy.

This figure represents both metabolic and toxic encephalopathies. Note that not all psychiatric syndromes due to medical conditions or states of substance intoxication or withdrawal necessarily qualify as an acute encephalopathy.

The definition in this position statement indicates that encephalopathy is a broader construct than delirium in that it can present with mental states beyond delirium alone (i.e., subsyndromal delirium or coma). However, on its own, a diagnosis of encephalopathy lacks operationalized criteria, making it impossible to identify reliably (12). Among many clinicians, the term encephalopathy is not clearly understood and rarely guides improvements in concept, research, or advocacy. Ultimately, delirium and encephalopathy should be understood as complementary and deserving of integration.

The authors endorse the recent position statement that describes acute encephalopathy as a rapidly evolving (< 4 weeks) pathobiological brain process that presents as subsyndromal delirium, delirium, or coma (11). The statement also makes clear that the “term acute encephalopathy is not recommended as a descriptor of clinical features that can be observed at the bedside.” We suggest the following points of refinement to this position statement:

- Delirium disorder. It is valuable to differentiate between the disorder of delirium (see prior descriptions of “delirium disorder” (9, 12, 14)) and the syndrome of delirium. We suggest using the term delirium disorder to describe the broader diagnostic construct, which includes the clinical syndrome, its proximate precipitant(s), and the unique pathophysiological disturbances mediating the two, and restricting the term delirium to describe the clinical phenotype seen at the bedside.

- This distinction fosters clear communication, as the term “delirium” is currently ambiguous, describing both the syndrome and the diagnosis.

- This proposal honors the common practice in psychiatric nosology to differentiate syndromes from diagnoses, such as distinguishing between the syndrome of a major depressive episode and the corresponding diagnosis of major depressive disorder (or bipolar disorder).

- This terminology parallels the introduction of major neurocognitive disorder in the DSM-5, a term that describes the broader diagnostic construct of dementia and incorporates underlying neuropathology.

- Restricting the term “delirium” to refer to the clinical syndrome encourages consideration of its core features (see section I. 2. Delirium) and of its unique neuropsychiatric symptoms that deserve independent attention (see section II. 1. Discrete neuropsychiatric symptoms)

- Rather than approaching all delirium as biologically “created equal,” it proposes pathophysiological subtypes (see section II. 2. Pathophysiological types).

Delirium. As operationalized in the DSM, which has long provided the field’s standard definition for both clinical practice and research, the delirium syndrome is described by Criteria A–D in DSM-III and III-R and Criteria A–C in DSM-IV through 5-TR. How best to define the syndrome of delirium, though, remains unsettled as definitions and severity thresholds vary across editions of the DSM, the ICD, common delirium assessments, and research criteria (15). In fact, even the iterative changes between editions of the DSM impact diagnosis considerably (16). There appears to be unique merit to the various approaches to validation, be it clinical prediction (17), correlation with electroencephalography (EEG) monitoring (18), or psychometric testing such as cluster analysis (19). Further work to harmonize delirium criteria drawing on the relative strengths of each approach to validation is to be encouraged. Interestingly, phenomenological analysis of delirium has identified three core domains (cognitive, higher-level thinking, and circadian); these findings deserve consideration in refining the field’s understanding of the syndrome (15). Also, given the importance of delirium screening, it remains to be seen how brief screening focused on these core domains (20) compares with alternative “ultra-brief” screening approaches (21).

Altered mental status. Although imprecise and disfavored when a more specific diagnosis is identifiable, “altered mental status” may be the most appropriate preliminary term available to describe clinical situations where the mental state cannot yet be specified further, as when evaluation is ongoing. For example, it may apply to early assessment of primary versus secondary psychiatric symptoms, particularly in emergency settings where background information is limited, and history and clinical course are yet to be determined (12). Nearly all instances of “altered mental status” deserve comprehensive medical assessment given the dangers of missing acute, treatable medical illness such as infections or electrolyte derangements.

Acute brain injury or acute brain failure, or acute brain dysfunction are disfavored, as these terms are imprecise. In each of these terms, “brain” is non-specific. For instance, transient ischemic attacks and acute demyelinating events (as in acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis) would also qualify, though these usually have presentations other than delirium. Notably, acute brain injury (ABI) is already used commonly to describe traumatic or anoxic brain injury, which might present with or without delirium. While delirium is associated with subsequent cognitive impairment and increased risk of dementia, not all of those with delirium develop new or accelerated cognitive decline. It is therefore misleading to describe delirium as inherently injurious. Regarding the term “failure,” we refer to Lipowski’s rationale in the preface to his second monograph on delirium: “The title [of my first book, Delirium: Acute Brain Failure in Man] was changed because the term ‘acute brain failure’ has been cogently criticized for being misleading. The brain as a whole does not fail in delirium; instead, its highest integrative functions, those subserving reception, processing, and retrieval of information, become disorganized, rendering a delirious person more or less incapable of thinking and acting in a rational, goal-directed manner” (22). Nevertheless, although “injury” and “failure” do not perfectly describe the phenomenon of delirium, such terms have the added benefit of calling attention to the sequelae that often attend delirium. The similar term “dysfunction” is also found in the now discouraged term “postoperative cognitive dysfunction” (23).

II. Nosology of delirium disorder and reappraisal of its subtypes

Future delirium classification systems should consider (1) its specific neuropsychiatric symptoms and (2) its unique pathophysiological disturbances, which entail more than simply “identifying the underlying causes” (9).

1. Discrete neuropsychiatric symptoms

The clinical syndrome of delirium has excellent reliability, validity, and clinical utility, but an under-explored aspect is its discrete neuropsychiatric symptoms. We provide a provisional list of such features that may receive independent clinical attention (see Table 1). Phenomenological work on delirium suggests that several of these symptoms tend to cluster together and may represent divergent manifestations of a similar underlying pathophysiological process (15). Future treatment trials should consider measuring and targeting specific neuropsychiatric symptoms as these are often the most dangerous and distressing aspect of delirium (readers are referred to psychiatrically informed delirium instruments (24-26)).

Table 1:

Neuropsychiatric features of delirium that may serve as a focus of clinical attention

| • Delusions or confabulation |

| • Perceptual disturbances, either illusions or hallucinations |

| • Affective lability or blunting |

| • Akathisia/restlessness |

| • Agitation* |

| • Inanition or abulia |

| • Catatonia |

| • Sleep-wake cycle disturbance |

• Other symptoms classically associated with delirium but variably captured by current tools include:

|

Specifically, a state of hyperarousal with psychomotor activation, reduced responsiveness to redirection, and often accompanied by verbal or physical aggression.

The current clinical approach to delirium commonly involves repurposing medications used for specific symptoms in other conditions for these symptoms occurring in delirium (e.g., antipsychotics to treat psychotic symptoms in delirium). This practice is pragmatic but not based on high-quality evidence. It is also not known how much the physiology underlying symptoms in delirium is like the physiology underlying these symptoms in other conditions. In other words, it is unknown how well evidence from other conditions generalizes to delirium.

The neuropsychiatric symptoms of delirium, similar in some respects to the non-cognitive features of dementia (27), are often severe, causing tremendous distress and potential danger to the patient, caregivers, and clinicians. Non-pharmacological approaches should be the foundation of delirium treatment, including its neuropsychiatric symptoms, though this is frequently inadequate to address acute clinical concerns. However, the use of any medications for delirium and its specific symptoms is off-label, and we are unable to make formal recommendations regarding specific treatments in the absence of high-quality evidence.

Delirium in relation to coma

Coma is a potential manifestation of acute encephalopathy with a very low level of arousal. Comatose patients do not open their eyes and do not follow commands to voice. Coma is therefore distinct from delirium, and its clinical significance is dependent on underlying conditions (e.g., coma during anesthesia has a better prognosis than coma due to a subarachnoid hemorrhage).

Delirium in relation to catatonia

Delirium and catatonia are clinical syndromes, and although they can occur together (28) the DSM-5-TR excludes catatonia diagnosis in the context of delirium. A conservative approach to evaluating for catatonia in delirium would be to exclude scoring any items confounded by medical status (e.g., omitting “mutism” in intubated patients), in the same way that one omits delirium assessment in patients with very low arousal (e.g., RASS < −3, as in patients on sedatives). Also, to avoid catatonia over-recognition in delirium, Wilson et al have suggested requiring 4 or more catatonia features to optimize both sensitivity and specificity (28). Although catatonia and delirium can each present across a motoric spectrum from hypokinetic to hyperkinetic, the pathophysiological significance of this convergence remains unknown. One conceptualization of this relationship posits that extreme motoric changes in delirium represent catatonic stupor or excitement, respectively (29). The state of the science on the relationship between delirium and catatonia remains in its early stages, limiting firm conclusions at this point. Given the difficulty of parsing out complex clinical syndromes, we would favor simpler conceptualization: that catatonia can be present in delirium and that it may inform diagnostic and treatment decisions, such as encouraging evaluation for encephalitis, structural brain pathology, or seizure activity (30).

Delirium in relation to psychotic disorders

Data on a relationship between psychotic disorders and delirium remain limited. It is unclear to what extent primary psychiatric illness represents a risk factor for delirium and in which contexts (31, 32) though one suspects that primary psychotic conditions, which involve salience network abnormalities, represent a general delirium vulnerability. It can be challenging to differentiate delirium from primary psychotic conditions, especially disorganized psychosis (33). The cognitive impairment associated with primary psychosis generally has minimal or mild impact on bedside cognitive tests (34). Differentiation of the etiology of psychosis requires serial assessments, detailed collateral, and care review of clinical course. EEG may be the most meaningful arbiter of primary vs secondary causes of delirium-like syndromes (33).

Delirium as a risk factor for posttraumatic stress disorder

Inconsistent data link delirium with subsequent PTSD (35, 36), and it remains unclear to what extent delirium may predict PTSD independent of intensive care unit (ICU)-level care or specific ICU-related factors. For instance, one study found that three quarters of patients had delusional memories of their ICU experience two weeks after discharge, and those without factual memories had the highest anxiety levels and PTSD symptoms after ICU discharge (37). Care-related risk factors for PTSD include benzodiazepine exposure, duration of sedation and mechanical ventilation. A systematic review of 26 studies in general ICU settings with mixed-diagnosis patients found a PTSD prevalence ranging from 8% to 27% (38); however, such observational studies should be interpreted with caution because confounding by comorbid anxiety may account for a portion these findings. Anxious patients may receive more sedatives, including benzodiazepines, and anxious patients have a higher risk of PTSD. Experiential factors include subjective experience of stress and fear, younger age/more aggressive treatments, and delusional memories. The data in support of delirium diaries is inconclusive regarding benefit to patients though the benefit to patients’ friends and families has been positive (39).

Antipsychotics in delirium

It is now well established from multi-center, placebo controlled RCTs that antipsychotics do not cure delirium (40, 41), though many questions remain regarding their role in delirium management. For instance, atypical antipsychotics may prevent postoperative delirium (42). Their role in treating individual neuropsychiatric symptoms of delirium remains undefined as large-scale studies of specific antipsychotics in specific types of delirium and for specific delirium symptoms have yet to be performed. Importantly, antipsychotics vary widely in receptor binding affinities, clinical activity, and side-effect profiles.

A prudent approach is to restrict the use of antipsychotics in delirium for managing severe agitation, psychotic symptoms, emotional distress of the patient, or otherwise to facilitate indicated treatment or prevent self-injury (e.g., risk of self-extubation due to perseveration, nondescript restlessness, or utilization behaviors). Their use should be for the shortest necessary time—typically a few days to a week, considering that the median duration of delirium in the ICU is 3 days (43). When these agents are used, clinicians should re-evaluate daily for ongoing need, effectiveness, and potential side effects (e.g., extra-pyramidal symptoms such as rigidity) that could paradoxically seem to worsen delirium symptoms. These agents should be discontinued prior to discharge unless there is a separate indication.

Clinicians should bear in mind that delirium symptoms may fluctuate, which can create the illusion that an intervention “worked,” introducing a possible post hoc ergo propter hoc logical fallacy (Latin for “after this, therefore because of this”). Clinicians should consider that patients with outlying symptoms such as severe agitation will tend to return to normal arousal. Consider the results of a recent trial of a single dose of adjunctive lorazepam 3 mg, added after 48 hours of scheduled haloperidol, for hyperactive delirium in patients with advanced cancer (44). Lorazepam led to greater sedation than placebo over the following 8 hours, yet the average Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) score of the placebo group ranged from −1 to 0 over the period from 30 minutes to 8 hours after administration. That is, the placebo group had regressed to the mean and was more likely to be at the traditional RASS target of −1 to 0 than those who received a sedative, whose average RASS was asleep.

Although only few randomized studies have associated antipsychotics with improved delirium-related outcomes (45, 46), it is also important to note that there is little evidence implicating them with harm. In both the REDUCE (41) and MIND-USA (40) critical care RCTs, the antipsychotics haloperidol (in both trials) and ziprasidone (in only MIND-USA) led to no difference in days alive without delirium or coma, and haloperidol had no effect on average ECG QT-time. In fact, a post hoc analysis of the REDUCE trial found a dose-dependent association between each milligram of haloperidol and decreased mortality at 28 and 90 days (47). By way of contrast, one RCT for delirium in palliative care patients found haloperidol to be associated with slightly higher mortality (48).

Electroconvulsive therapy and delirium

ECT in delirium is experimental as there are no more than small case series to support its use (49). Several ethical and judicial questions would also need to be addressed, as patients with delirium seldom retain capacity to consent, and many jurisdictions require a probate court to authorize ECT in the absence of patient consent. We would also urge caution regarding the use of ECT for delirium where it may inadvertently curtail an appropriate workup for underlying etiologies. Finally, where delirium presents with catatonic features, clinicians may conduct a careful analysis of the risks and benefits of catatonia-specific treatments such as benzodiazepines and other treatments, including ECT.

2. Pathophysiological types (endotypes)

The longstanding approach to treating delirium is to “treat the underlying cause,” but in most cases there are multiple precipitants and predisposing factors of delirium, many of which are non-modifiable. At times, treating the underlying cause might not be an option, such as when the cause is ambiguous, elusive, not readily reversible, historical (such as surgery or TBI), or already resolved. One cannot treat what cannot be identified or modified, thus, there is likely additional value in defining and treating physiological disturbances that mediate the proximate causes with the symptomatic expression of delirium. In most cases, this will represent the downstream effects of the proximate cause, such as neuroinflammation that mediates the tissue injury of surgery with postoperative delirium. At times the proximate cause may itself directly cause delirium, for example, anticholinergic toxidromes. In all cases, proximate causes should inform relevant neuropathophysiology as certain precipitants are associated with defined downstream physiological disturbances (e.g., the physiology of hepatic encephalopathy).

A physiologically informed approach to delirium management should treat not only the underlying cause but also any relevant “deliriogenic” physiological disturbances—for example, managing alcohol withdrawal delirium by addressing glutamatergic excess with benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or antiepileptic agents, and targeting adrenergic excess with an alpha-2 agonist (50)). Future work should consider validating a typology of delirium pathophysiology. Table 2 presents recent proposals to identify pathophysiological types (“endotypes”) of delirium, each of which has proposed very similar categories. One might also consider how delirium prevention and treatment interventions provide mechanistic insights into different biological mechanisms of delirium and encephalopathy (see Supplement).

Table 2:

Previously proposed pathophysiological types (endotypes) of delirium

| “Substrates” (8)* | Neurophysiological types (9)† | Biological mechanisms (2)‡ | Mechanisms (10)§ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endotypes | Neuroinflammation | Neuroinflammation | Inflammation | Neuroinflammation | CRP, procalcitonin, TNF-alpha, cortisol, S100B, interleukins |

| Oxidative stress | Oxidative stress | Brain energy metabolism | Oxidative stress | Reactive oxygen species, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, catalase | |

| Neuroendocrine | Neuroendocrine/HPA | Stress | Stress | Glucocorticoid release | |

| Circadian rhythm dysregulation | Circadian arrhythmia | Disturbed arousal¶ | Melatonin dysregulation | 6-sulphatoxymelatonin, sleep–wake cycle disruption | |

| Neuronal aging (multifactorial; vulnerability to physical stress) | Brain aging | Microglial and astrocytic priming Endothelial and blood–brain barrier dysfunction Neurodegenerative pathology |

Neuronal aging | Atrophy, white matter disruption, neurofilament light | |

| Neurotransmitter dysregulation# | Neurotransmitter dysfunction

|

Neurotransmitter disturbance | Neurotransmitter disturbance | Serotonin, dopamine, acetylcholine | |

| Final pathway | Systems integration failure# | Network dysconnectivity | Reduced integration of brain networks | Network dysconnectivity | Electroencephalography, functional magnetic resonance imaging |

Maldonado catalogs precipitants by the acronym END ACUTE BRAIN FAILURE

Oldham et al. describe prototypic conditions for each of the neurophysiological types; also omitted from this column is “cerebral edema,” which is not reflected in other systems.

Wilson et al. describe major perturbations including systemic triggers (i.e., acute systemic inflammation, hypoxemia, impaired blood flow, and metabolic derangement) and drugs (e.g., GABAergic sedatives, anticholinergics, antihistamines) that precipitate the biological mechanisms listed in this column.

Bowman et al. also propose biomarkers for each of the mechanisms described.

Sleep–wake or circadian disturbance is not included as a physiological mechanism, though reticular ascending arousal system, thalamocortical activation, and cortical integration are cited as contributory.

These substrates are described as leading to two “critical factors,” including “neurotransmitter dysregulation” and “network dysconnectivity”

As delirium often has a multifactorial etiology, pathophysiologically distinct syndromes have been largely unexplored in delirium research to date (with a notable exception (51)) in which different etiological groups could overlap. As unique precipitants cause delirium via different mechanisms, a one-size-fits-all approach to delirium management is not justified in many if not most instances. This also implies that if a clinical trial finds a treatment for “delirium” as efficacious in one setting, it may have limited relevance in other settings. Studies that include patients based on the clinical syndrome of delirium but do not simultaneously seek to identify relevant pathophysiological disturbances, as well as systematic reviews that pool studies of “delirium” across settings, are liable to introduce a high degree of heterogeneity.

Final common pathway

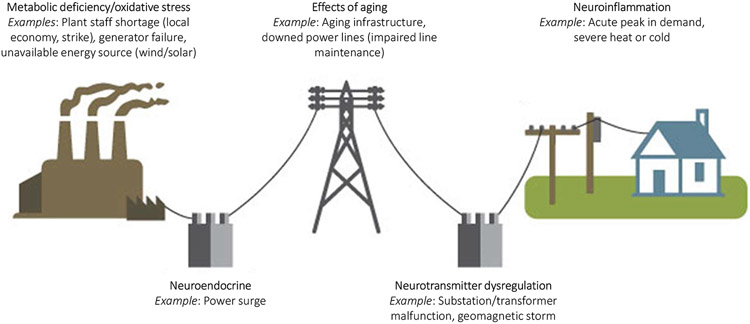

The link between delirium and subsequent dementia diagnosis (52) remains a driving motivation behind ongoing efforts to illuminate the biology of delirium (7). Such a drive may best approach delirium as biologically distinct “deliria” rather than a singular biological condition. It is presumed that upstream causes of delirium converge to cause downstream network dysfunction, characterized by disruption in the expected anticorrelation between default mode and cognitive executive networks (8, 53), loss of connectivity strength and brain network disintegration (54, 55). However, there may be several distinct and interactive biological paths that lead to this final common pathway. The recent Systems Integration Failure Hypothesis (SIFH) seeks to integrate many prior hypotheses and demonstrate how the specific cognitive and behavioral manifestations observed in delirium result from a combination of neurotransmitters function and availability, variability in integration and processing of sensory information, motor responses to both external and internal cues, and the degree of breakdown in neuronal network connectivity (8). There are many ways that a network can ‘break down’ such as energy deficiency, region-specific disturbances, direct effect on neurotransmitter systems, and neuro-inflammation (Figure 2), each of which would entail unique treatment considerations to restore network function.

Figure 2: Analogy of the different types of electrical grid disruption.

Consider the many ways an electrical grid might malfunction. Each kind of disruption requires its own approach to restore grid activity. Repairs may require that the grid function at a lower power for a time (e.g., reduced level of arousal), that certain customers lose power temporarily (e.g., dysfunction in specific neurocognitive domains) or that the entire grid be reset (e.g., a restorative night’s rest). Some insults will cause irreversible damage (e.g., aging) whereas others cause only a temporary disruption of service (e.g., anesthesia). Adapted from public domain image from US Energy Information Administration.

Electroencephalography and delirium

Patients with conditions that may mimic delirium, such as depression or psychosis, have typically a normal or a very mildly disturbed EEG. The most common EEG findings in delirium include slowing of peak and average frequencies, decreased alpha activity, and increased theta and delta activity resulting in diffuse slowing. Therefore, clinical EEG measurements have the potential to provide objective diagnostic information regarding the presence of delirium, the potential to identify clinical delirium objectively, and even to detect the presence of subsyndromal delirium or pre-delirium states. Data obtained from the limited number of studies available suggest that EEG changes correlate with the degree of cognitive deficit, but there does not appear to be a clear relationship between EEG patterns and delirium motoric type (56). In rare cases, delirium results from non-convulsive seizures or a non-convulsive status epilepticus (57, 58). This is particularly observed in patients with prior seizures, abnormal eye movements, or automatisms.

The clinical utility of EEG in diagnosing delirium may be constrained by the occasional impracticality in agitated and combative patients. Still, EEG can clarify diagnosis, such as identifying epileptiform activity (e.g., non-convulsive status), confirming an underlying encephalopathy (e.g., posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome due to the use of calcineurin inhibitors), or ruling out encephalopathy in primary catatonia or in presentations of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia or other permanent neurocognitive syndromes. For instance, the abulia or disinhibition occasionally encountered in dementia, particularly when there is frontal lobe (59) or cerebellar (60) involvement, can mimic hypo- or hyperactive motoric expressions of delirium, respectively.

There is no other way to assess acute encephalopathy than with EEG. Therefore, a normal EEG precludes acute encephalopathy (61). However, ample polymorphous delta activity may be associated with very mild delirium features (such as cognitive slowing), and with focal lesions (such as an infarction). To diagnose most acute encephalopathies, it is neither feasible nor necessary to require a standard 30-minute, 21-channel EEG with evaluation by a neurophysiologist.

A brief, one-channel EEG recording with automated analysis might serve as an objective tool to assess for the encephalopathy that underlies delirium (62). An assessment takes about 5 minutes to perform and results in a score indicating the probability of delirium. A device to monitor delirium with fixed electrodes and a dedicated detection algorithm has been approved for regular patient care in the European Union (i.e., CE certification) and is currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

III. Future directions

Harmonization

There are many opportunities for journals, professional societies, and interest groups to facilitate harmonization of criteria for delirium and encephalopathy. Inter-disciplinary collaboration and robust dialogue to promote awareness and design a shared framework is an essential first step. Currently, those who use these two sets of terms—delirium and acute encephalopathy—are almost entirely siloed from one another (11). Proposals that seek to integrate the two are likely to be better received than those that unilaterally favor one model over the other. Further, advocacy and educational efforts to enhance clinician knowledge will continue to be critical at gaining recognition for this set of conditions, as well as for the widespread implementation of prevention and treatment efforts. Prioritization of research funding as well as regulation and reimbursement coding will also be key to advancing the field.

Cognitive and functional outcomes of delirium

Delirium and dementia share a bidirectional relationship: even mild cognitive impairment is a significant risk factor for delirium (63), and delirium is a risk factor for accelerated cognitive decline (64) and categorical dementia diagnosis (52). However, our current understanding of the mechanisms underlying the link between delirium and neuropathology remains underdeveloped (65). Also, in the same way that the delirium and encephalopathy fields have been siloed from one another, the delirium and dementia fields have remained largely separate as well. One might anticipate that collaboration between researchers in these two fields could prove mutually beneficial as dementia is among the dire outcomes of delirium that delirium researchers aim to prevent and delirium is an acute neurophysiological disturbance with implications for long-term cognition and function.

Underrepresented groups in delirium research

Future studies should address the full age spectrum, from children to older adults. Notably, the science and practice of pediatric delirium remains underdeveloped in relation to adult delirium; hence, it is unknown whether, to what extent, or how pediatric delirium might differ from adult delirium. Only recently have the pediatric confusion assessment method (CAM) (66) and preschool CAM (67) been validated for reliable widespread screening efforts.

The roles of race, ethnicity and cultural factors in delirium risk and management are largely unknown. Much of delirium research to date, especially in English-speaking countries, has focused on White patients, which questions the generalizability of current evidence to patients of other races and ethnicities. In a rare study of the role of race on delirium risk, Khan et al. found no difference in delirium risk and perhaps lower rates of delirium among younger Black subjects (68), though the reasons for this remain largely unknown. Questions also remain regarding whether minority patients may be more or less likely to receive certain care interventions, such as antipsychotics.

Coding

Beyond the basic principle of advocating for mental health parity throughout healthcare, this change stands to facilitate several advancements in clinical care. First, it would signal alignment between widely advocated systematic screening efforts for delirium and appropriate recognition of delirium’s impact on care. Second, moving toward “delirium” as the case-defining clinical syndrome of acute encephalopathy prioritizes mental health considerations and requires that clinicians document patient experiences adequately (and, practically, have more meaningful conversations with their patients). Third, the use of the term “delirium” clinically would direct clinicians to delirium practice guidelines and the far more substantial evidence base on “delirium” than on the generic terms “metabolic encephalopathy” and “toxic encephalopathy.” Fourth, use of the term delirium can help clinicians to direct patients’ families and loved ones to resources to understand delirium and how they can help the patient. Fifth, a focus on delirium, which has reliable, operationalized criteria, allows for systematic screening and early detection efforts because the onset of delirium can often lead to a cascade of behavioral, psychological, and cognitive events that perpetuate or reinforce the delirium itself.

Clinical culture change

The comments above all pertain to varying aspects of hospital culture, collaborative care, and the liaison role of C-L psychiatry. Advocating for the importance of delirium as a singular diagnosis should share similarities to our advocacy of mental health in general—namely, to foster interdisciplinary relationships with colleagues, to share insights into the condition, and to review and follow the literature collaboratively with colleagues. Culture change takes time, and many—if not most—primary medical and surgical practitioners recognize that we have little available to “treat” delirium or hasten its resolution. The difficulties we have faced in advancing the science of delirium is a substantial barrier to advancing clinical practice.

A considered approach should acknowledge that not all instances of delirium are toxic, and we should be less alarmist about delirium as a “medical emergency.” Whereas it is a pressing concern and any change in mental status deserves close attention (regardless of whether it is considered as a new “vital sign” (69)), the risk of alarm fatigue and over-wrought concerns about delirium are likely to undermine the message. Until it is proven that systematic screening for delirium improves outcomes or that specific interventions reduce suffering, decrease duration of admission, improve long-term outcomes, or otherwise prove cost-effective, delirium implementation science will flag. Two notable standouts—the HELP model and A-to-F bundle—are cost-effective and warrant advocacy for their widespread adoption (70, 71).

Navigating conversations with colleagues and perceived “push-back” about delirium in specific patient care decisions requires diplomacy and should consider the expense of any pyrrhic short-term gains over longer-term collaboration and developing shared goals. Educational efforts to patients and teams, sharing updates on delirium science, reviewing systemic practices at one’s own institution, and developing clinical pathways that harmonize efforts across settings are likely to have greater impact—again, all of which draw upon our liaison role. A more robust model like delirium disorder may also help to offer meaningful clarification on the nature of this condition and highlight specific behaviors and symptoms that warrant clinical intervention.

Translational science

In line with the model of delirium disorder, which incorporates different physiological subtypes, we support and call for translational research to parse these out and identify novel treatments. Numerous agents with presumed neuroprotective effects have failed in RCTs in different conditions (e.g. traumatic brain injury, stroke). Whereas research on neuroprotective interventions in delirium, especially in those at greatest cognitive vulnerability, deserves attention, it is unlikely that delirium will be treated with neuroprotective agents soon. Anti-inflammatory strategies are conceptually interesting to explore in delirium, but currently lack evidence. Theoretically, brain network alterations as observed in delirium could be modified by non-invasive brain stimulation (72, 73), but empirical data using this approach are up until now lacking. MRI and EEG recordings have the potential to fundamentally increase our understanding of pathways that lead to delirium, of brain network changes during delirium, and of pathways related to the outcome of delirium. Severe agitation precludes MRI and EEG recordings, but these imaging techniques are feasible in less severely hyperactive patients with delirium (53, 62). Artificial intelligence techniques are increasingly used to investigate almost all aspects of delirium, including the relationships between etiological factors, EEG characteristics and clinical findings. Animal models have also received growing attention in studying delirium-like phenotypes (2, 7).

Although progress on pharmacotherapy of delirium may also be achieved with observational studies, RCTs remain pivotal. The American Delirium Society, the Australasian Delirium Association and the European Delirium Association are broadly interdisciplinary organizations focused on bringing clinicians and scientists together to advance the field. Also, the Network for Investigation of Delirium: Unifying Scientists (NIDUS) offers the Delirium Research Hub that seeks to link scientists for collaboration.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of delirium disorder offers a means of unifying the models of delirium and acute encephalopathy. It encompasses the presenting symptoms (“delirium”), pathophysiological complexity, and underlying causes. This model also encourages the field to move beyond subtyping delirium based solely on the level of motoric activity. We have proposed two ways that delirium might be classified in the future—based on (1) specific neuropsychiatric symptoms and (2) unique pathophysiological disturbances. Throughout, we have incorporated audience comments and questions to bridge the concepts presented during the plenary session with common and pressing clinical questions.

Though the proposals in this statement are based on the best evidence available, many fundamental questions remain, and research is needed to validate and refine new clinical subtypes of delirium disorder. We recommend that future approaches to neuropsychiatric symptoms and pathophysiological disturbances seek to balance validity with clinical utility because ultimately the value in the current set of proposals lies not necessarily in its formal adoption but in the advancing of clinical care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This review is derived from an interdisciplinary panel discussion entitled “Rethinking and Rehashing Delirium” held during the 2021 Annual Meeting of the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry.

Role of the funding source:

This article did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosures:

MO: Support from K23 AG072383

AS: Unsalaried advisor for Prolira, a start-up company developing an EEG-based delirium monitor. Any future profits from EEG-based delirium monitoring to be used for scientific research only.

EWE: Honoraria for CME lectures sponsored by Pfizer and Orion

CC, JRM, LR: No disclosures

References

- 1.Fuchs S, Bode L, Ernst J, Marquetand J, von Kanel R, Bottger S. Delirium in elderly patients: Prospective prevalence across hospital services. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;67:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson JE, Mart MF, Cunningham C, Shehabi Y, Girard TD, MacLullich AMJ, et al. Delirium. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNicoll L, Pisani MA, Zhang Y, Ely EW, Siegel MD, Inouye SK. Delirium in the intensive care unit: occurrence and clinical course in older patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(5):591–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leslie DL, Inouye SK. The importance of delirium: economic and societal costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59 Suppl 2:S241–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson C World Alzheimer report 2018. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International., 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gou RY, Hshieh TT, Marcantonio ER, Cooper Z, Jones RN, Travison TG, et al. One-Year Medicare Costs Associated With Delirium in Older Patients Undergoing Major Elective Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(5):430–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khachaturian AS, Hayden KM, Devlin JW, Fleisher LA, Lock SL, Cunningham C, et al. International drive to illuminate delirium: A developing public health blueprint for action. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(5):711–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maldonado JR. Delirium pathophysiology: An updated hypothesis of the etiology of acute brain failure. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(11):1428–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oldham MA, Flaherty JH, Maldonado JR. Refining Delirium: A Transtheoretical Model of Delirium Disorder with Preliminary Neurophysiologic Subtypes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(9):913–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowman EML, Cunningham EL, Page VJ, McAuley DF. Phenotypes and subphenotypes of delirium: a review of current categorisations and suggestions for progression. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slooter AJC, Otte WM, Devlin JW, Arora RC, Bleck TP, Claassen J, et al. Updated nomenclature of delirium and acute encephalopathy: statement of ten Societies. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):1020–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oldham MA, Holloway RG. Delirium disorder: Integrating delirium and acute encephalopathy. Neurology. 2020;95(4):173–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crone CC, Oldham MA, Ely EW, Slooter A. Rethinking and Rehasing Delirium. CLP 2021. Virtual: Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry; November 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oldham MA. Delirium disorder: Unity in diversity. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2022;74:32–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trzepacz PT, Meagher DJ, Franco JG. Comparison of diagnostic classification systems for delirium with new research criteria that incorporate the three core domains. J Psychosom Res. 2016;84:60–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meagher DJ, Morandi A, Inouye SK, Ely W, Adamis D, Maclullich AJ, et al. Concordance between DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria for delirium diagnosis in a pooled database of 768 prospectively evaluated patients using the delirium rating scale-revised-98. BMC Med. 2014;12:164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vasunilashorn SM, Guess J, Ngo L, Fick D, Jones RN, Schmitt EM, et al. Derivation and Validation of a Severity Scoring Method for the 3-Minute Diagnostic Interview for Confusion Assessment Method--Defined Delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(8):1684–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ely EW, Truman B, Manzi DJ, Sigl JC, Shintani A, Bernard GR. Consciousness monitoring in ventilated patients: bispectral EEG monitors arousal not delirium. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(8):1537–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sepulveda E, Franco JG, Trzepacz PT, Gaviria AM, Meagher DJ, Palma J, et al. Delirium diagnosis defined by cluster analysis of symptoms versus diagnosis by DSM and ICD criteria: diagnostic accuracy study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franco JG, Ocampo MV, Velasquez-Tirado JD, Zaraza DR, Giraldo AM, Serna PA, et al. Validation of the Delirium Diagnostic Tool-Provisional (DDT-Pro) With Medical Inpatients and Comparison With the Confusion Assessment Method Algorithm. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;32(3):213–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcantonio ER, Fick DM, Jung Y, Inouye SK, Boltz M, Leslie DL, et al. Comparative Implementation of a Brief App-Directed Protocol for Delirium Identification by Hospitalists, Nurses, and Nursing Assistants : A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(1):65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipowski ZJ. Delirium: Acute Confusional States. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evered L, Silbert B, Knopman DS, Scott DA, DeKosky ST, Rasmussen LS, et al. Recommendations for the Nomenclature of Cognitive Change Associated with Anaesthesia and Surgery-2018. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(5):872–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Roth A, Smith MJ, Cohen K, Passik S. The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(3):128–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trzepacz PT, Mittal D, Torres R, Kanary K, Norton J, Jimerson N. Validation of the Delirium Rating Scale-revised-98: comparison with the delirium rating scale and the cognitive test for delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13(2):229–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alosaimi FD, Alghamdi A, Alsuhaibani R, Alhammad G, Albatili A, Albatly L, et al. Validation of the Stanford Proxy Test for Delirium (S-PTD) among critical and noncritical patients. J Psychosom Res. 2018;114:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerlach LB, Kales HC. Managing Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. Clin Geriatr Med. 2020;36(2):315–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson JE, Carlson R, Duggan MC, Pandharipande P, Girard TD, Wang L, et al. Delirium and Catatonia in Critically Ill Patients: The Delirium and Catatonia Prospective Cohort Investigation. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(11):1837–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maldonado JR. Acute Brain Failure: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management, and Sequelae of Delirium. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(3):461–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oldham MA. The Probability That Catatonia in the Hospital has a Medical Cause and the Relative Proportions of Its Causes: A Systematic Review. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(4):333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milisen K, Van Grootven B, Hermans W, Mouton K, Al Tmimi L, Rex S, et al. Is preoperative anxiety associated with postoperative delirium in older persons undergoing cardiac surgery? Secondary data analysis of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oldham MA, Hawkins KA, Lin IH, Deng Y, Hao Q, Scoutt LM, et al. Depression Predicts Delirium After Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery Independent of Cognitive Impairment and Cerebrovascular Disease: An Analysis of the Neuropsychiatric Outcomes After Heart Surgery Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(5):476–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson JE, Andrews P, Ainsworth A, Roy K, Ely EW, Oldham MA. Pseudodelirium: Psychiatric Conditions to Consider on the Differential for Delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;33(4):356–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosca EC, Cornea A, Simu M. Montreal Cognitive Assessment for evaluating the cognitive impairment in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;65:64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bolton C, Thilges S, Lane C, Lowe J, Mumby P. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Following Acute Delirium. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2021;28(1):31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rengel KF, Hayhurst CJ, Jackson JC, Boncyk CS, Patel MB, Brummel NE, et al. Motoric Subtypes of Delirium and Long-Term Functional and Mental Health Outcomes in Adults After Critical Illness. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(5):e521–e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones C, Griffiths R, Humphris G, Skirrow PM. Memory, delusions, and the development of acute posttraumatic stress disorder-related symptoms after intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(3):573–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wade D, Hardy R, Howell D, Mythen M. Identifying clinical and acute psychological risk factors for PTSD after critical care: a systematic review. Minerva anestesiologica. 2013;79(8):944–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McIlroy PA, King RS, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Tabah A, Ramanan M. The Effect of ICU Diaries on Psychological Outcomes and Quality of Life of Survivors of Critical Illness and Their Relatives: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(2):273–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, Hough CL, Rock P, Gong MN, et al. Haloperidol and Ziprasidone for Treatment of Delirium in Critical Illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van den Boogaard M, Slooter AJC, Bruggemann RJM, Schoonhoven L, Beishuizen A, Vermeijden JW, et al. Effect of Haloperidol on Survival Among Critically Ill Adults With a High Risk of Delirium: The REDUCE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;319(7):680–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neufeld KJ, Needham DM, Oh ES, Wilson LM, Nikooie R, Zhang A, et al. Antipsychotics for the Prevention and Treatment of Delirium. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 2019. AHRQ. 2019;Publication No. 19-EHC019-EF. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pisani MA, Kong SY, Kasl SV, Murphy TE, Araujo KL, Van Ness PH. Days of delirium are associated with 1-year mortality in an older intensive care unit population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(11):1092–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hui D, Frisbee-Hume S, Wilson A, Dibaj SS, Nguyen T, De La Cruz M, et al. Effect of Lorazepam With Haloperidol vs Haloperidol Alone on Agitated Delirium in Patients With Advanced Cancer Receiving Palliative Care: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318(11):1047–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oh ES, Needham DM, Nikooie R, Wilson LM, Zhang A, Robinson KA, et al. Antipsychotics for Preventing Delirium in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nikooie R, Neufeld KJ, Oh ES, Wilson LM, Zhang A, Robinson KA, et al. Antipsychotics for Treating Delirium in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duprey MS, Devlin JW, van der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P, Briesacher BA, Saczynski JS, et al. Association Between Incident Delirium Treatment With Haloperidol and Mortality in Critically Ill Adults. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(8):1303–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, Draper B, Caplan GA, Rowett D, et al. Efficacy of Oral Risperidone, Haloperidol, or Placebo for Symptoms of Delirium Among Patients in Palliative Care: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nielsen RM, Olsen KS, Lauritsen AO, Boesen HC. Electroconvulsive therapy as a treatment for protracted refractory delirium in the intensive care unit--five cases and a review. J Crit Care. 2014;29(5):881 e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maldonado JR. Novel Algorithms for the Prophylaxis and Management of Alcohol Withdrawal Syndromes-Beyond Benzodiazepines. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(3):559–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Girard TD, Thompson JL, Pandharipande PP, Brummel NE, Jackson JC, Patel MB, et al. Clinical phenotypes of delirium during critical illness and severity of subsequent long-term cognitive impairment: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(3):213–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Richardson SJ, Davis DHJ, Stephan BCM, Robinson L, Brayne C, Barnes LE, et al. Recurrent delirium over 12 months predicts dementia: results of the Delirium and Cognitive Impact in Dementia (DECIDE) study. Age Ageing. 2021;50(3):914–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oh J, Shin JE, Yang KH, Kyeong S, Lee WS, Chung TS, et al. Cortical and subcortical changes in resting-state functional connectivity before and during an episode of postoperative delirium. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2019;53(8):794–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Numan T, Slooter AJC, van der Kooi AW, Hoekman AML, Suyker WJL, Stam CJ, et al. Functional connectivity and network analysis during hypoactive delirium and recovery from anesthesia. Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128(6):914–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Montfort SJT, van Dellen E, van den Bosch AMR, Otte WM, Schutte MJL, Choi SH, et al. Resting-state fMRI reveals network disintegration during delirium. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;20:35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koponen H, Partanen J, Paakkonen A, Mattila E, Riekkinen PJ. EEG spectral analysis in delirium. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1989;52(8):980–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nielsen RM, Urdanibia-Centelles O, Vedel-Larsen E, Thomsen KJ, Moller K, Olsen KS, et al. Continuous EEG Monitoring in a Consecutive Patient Cohort with Sepsis and Delirium. Neurocrit Care. 2020;32(1):121–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Naeije G, Depondt C, Meeus C, Korpak K, Pepersack T, Legros B. EEG patterns compatible with nonconvulsive status epilepticus are common in elderly patients with delirium: a prospective study with continuous EEG monitoring. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;36:18–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Finkel SI, Costa e Silva J, Cohen G, Miller S, Sartorius N. Behavioral and psychological signs and symptoms of dementia: a consensus statement on current knowledge and implications for research and treatment. International psychogeriatrics / IPA. 1996;8 Suppl 3:497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Argyropoulos GPD, van Dun K, Adamaszek M, Leggio M, Manto M, Masciullo M, et al. The Cerebellar Cognitive Affective/Schmahmann Syndrome: a Task Force Paper. Cerebellum. 2020;19(1):102–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hut SCA, Dijkstra-Kersten SMA, Numan T, Henriquez N, Teunissen NW, van den Boogaard M, et al. EEG and clinical assessment in delirium and acute encephalopathy. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;75(8):265–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Numan T, van den Boogaard M, Kamper AM, Rood PJT, Peelen LM, Slooter AJC, et al. Delirium detection using relative delta power based on 1-minute single-channel EEG: a multicentre study. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122(1):60–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oldham MA, Hawkins KA, Yuh DD, Dewar ML, Darr UM, Lysyy T, et al. Cognitive and functional status predictors of delirium and delirium severity after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: an interim analysis of the Neuropsychiatric Outcomes After Heart Surgery study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(12):1929–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Inouye SK, Marcantonio ER, Kosar CM, Tommet D, Schmitt EM, Travison TG, et al. The short-term and long-term relationship between delirium and cognitive trajectory in older surgical patients. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(7):766–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang S, Lindroth H, Chan C, Greene R, Serrano-Andrews P, Khan S, et al. A Systematic Review of Delirium Biomarkers and Their Alignment with the NIA-AA Research Framework. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith HA, Boyd J, Fuchs DC, Melvin K, Berry P, Shintani A, et al. Diagnosing delirium in critically ill children: Validity and reliability of the Pediatric Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(1):150–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smith HA, Gangopadhyay M, Goben CM, Jacobowski NL, Chestnut MH, Savage S, et al. The Preschool Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU: Valid and Reliable Delirium Monitoring for Critically Ill Infants and Children. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(3):592–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Khan BA, Perkins A, Hui SL, Gao S, Campbell NL, Farber MO, et al. Relationship Between African-American Race and Delirium in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(9):1727–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Flaherty JH, Rudolph J, Shay K, Kamholz B, Boockvar KS, Shaughnessy M, et al. Delirium is a serious and under-recognized problem: why assessment of mental status should be the sixth vital sign. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8(5):273–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hshieh TT, Yang T, Gartaganis SL, Yue J, Inouye SK. Hospital Elder Life Program: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Effectiveness. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(10):1015–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, Thompson JL, Aldrich JM, Barr J, et al. Caring for Critically Ill Patients with the ABCDEF Bundle: Results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in Over 15,000 Adults. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(1):3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shafi MM, Santarnecchi E, Fong TG, Jones RN, Marcantonio ER, Pascual-Leone A, et al. Advancing the Neurophysiological Understanding of Delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oh J, Ham J, Cho D, Park JY, Kim JJ, Lee B. The Effects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on the Cognitive and Behavioral Changes After Electrode Implantation Surgery in Rats. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.