Abstract

Heat-killed Brucella abortus (HBa) has been proposed as a carrier for therapeutic vaccines for individuals with immunodeficiency, due to its abilities to induce interleukin-2 (IL-2) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and to upregulate antigen-presenting cell functions (including IL-12 production). In the current study, we investigated the ability of HBa or lipopolysaccharide isolated from HBa (LPS-Ba) to elicit β-chemokines, known to bind to the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) coreceptor CCR5 and to block viral cell entry. It was found that human peripheral blood mononuclear cells secreted β-chemokines following stimulation with HBa, and this effect could not be blocked by anti-IFN-γ neutralizing antibodies. Among purified T cells, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α and 1β (MIP-1α and MIP-1β, respectively) secretion was observed primarily in human CD8+ T cells. The kinetics of β-chemokine induction in T cells were slow (3 to 4 days). The majority of β-chemokine-producing CD8+ T cells also produced IFN-γ following HBa stimulation, as determined by triple-color intracellular staining. A significant number of CD8+ T cells contained stored MIP-1β that was released after HBa stimulation. Both HBa and LPS-Ba stimulated high levels of MIP-1α and MIP-1β production in elutriated monocytes and even higher levels in macrophages. In these cells, β-chemokine mRNA was upregulated within 30 min and proteins were secreted within 4 h of stimulation. The monocyte- and macrophage-derived β-chemokines were sufficient to block CCR5-dependent HIV-1 envelope-mediated cell fusion. These data suggest that, in addition to the ability of HBa to elicit antigen-specific humoral and cellular immune responses, HBa-conjugated HIV-1 proteins or peptides would also generate innate chemokines with antiviral activity that could limit local viral spread during vaccination in vivo.

The discovery that several β-chemokines (i.e., macrophage inflammatory proteins 1α and 1β [MIP-1α and MIP-1β, respectively] and RANTES) secreted by short-term human CD8+ cell lines can effectively block infection of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with macrophage-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) strains led to the realization that several chemokine receptors function as coreceptors that are required for HIV-1 cell entry in addition to the CD4 molecule (4, 6, 7, 8, 21). It was also established that the chemokine receptors most often used in vivo by HIV-1 strains are CCR5 (R5) and CXCR4 (X4) (38). Furthermore, most primary infections are restricted to R5-dependent viral strains, and individuals carrying a genetic deletion in the R5 gene (Δ32/Δ32) are protected against infection (26, 30). Heterozygous individuals (Δ32/+) can be infected but show slower disease progression (5, 19). More recently, it was shown that the propagation of R5-tropic HIV-1 strains in polarized human CD4+ TH1 lines was limited compared with that in polarized TH2 lines. The limited expression of R5-tropic HIV-1 strains in TH1 cell lines was explained by their ability to produce RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β following viral infection (1). Similarly, it was found that bone marrow-derived CD34+ cells and megakaryoblasts secrete β-chemokines that block infection of hematopoietic cells by R5-tropic HIV strains (27). Thus, local secretion of β-chemokines may limit viral spread in vivo. In agreement with this prediction, several studies demonstrated that PBMCs from HIV-1-infected, long-term nonprogressors often produce higher levels of β-chemokines upon antigen stimulation in vitro than do PBMCs from rapid progressors (9, 29).

These important findings suggested that the ability to elicit β-chemokines in vivo could enhance the protective potential of HIV-1 vaccine candidates. Indeed, it was reported that β-chemokines and neutralizing antibody titers correlated with sterilizing immunity generated against simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) in subunit-vaccinated macaques (16, 23).

Our group has been evaluating the use of the heat-inactivated gram-negative bacterium Brucella abortus (HBa) as a vaccine carrier for either therapeutic or prophylactic HIV vaccines. So far, it has been demonstrated that HBa is a potent stimulator of TH1-type cytokines (gamma interferon [IFN-γ] and interleukin-2 [IL-2]) in murine and human T cells (both CD4+ and CD8+), can elicit IL-12 p70 from dendritic cells and monocytes, and upregulates stimulatory and adhesion molecules on antigen-presenting cells (3, 12, 13, 18, 36, 37). In addition, HBa conjugated to HIV-1 V3-derived peptide generated neutralizing antibodies and virus-specific cytotoxic T cells both in normal mice and in mice depleted of CD4+ T cells (10, 11, 22, 32). In the current study, we demonstrate the ability of HBa and of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) isolated from HBa (LPS-Ba) to induce β-chemokines from human PBMCs, T-cell subsets, monocytes, and monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM). In addition, we investigated the ability of HBa-induced β-chemokines derived from human monocytes and macrophages to block HIV-1 envelope-mediated cell fusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

HBa was obtained from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Ames, Iowa (heat inactivation is done at 80oC for 1 h; complete bacterial inactivation is determined and certified by the U.S. Department of Agriculture). HBa was used at 108 organisms/ml in all cultures. LPS-Ba was derived by butanol extraction as described previously (2, 15) and was used at a concentration of 3 or 0.3 μg/ml. These doses of LPS-Ba were selected based on earlier determinations in which the amount of LPS associated with 108 organisms of HBa/ml was calculated to be in the range of 0.5 to 2.3 μg/ml. The polyclonal T-cell activators phytohemagglutinin (PHA) and phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) were used at 1 μg/ml and 10 ng/ml, respectively.

Cell preparation.

Heparinized peripheral blood was drawn from healthy donors at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Blood Bank. Interphase cells enriched for PBMCs from Ficoll-Hypaque (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) gradient centrifugation were collected. In some experiments, PBMCs were passed through a nylon wool column, and the nonadherent cell population, enriched for T cells (≥90%), was used in the experiments. In some experiments, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were obtained from PBMCs using positive selection with anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Human blood monocytes from healthy volunteers were isolated with an elutriator at the NIH Blood Bank. To obtain MDM, 3 × 106 elutriated monocytes were incubated in 2 ml of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (1,000 U/ml; Immunex Corp., Seattle, Wash.) and 10% fresh pooled human serum (from the NIH Blood Bank) (heat inactivated) in six-well plates (Costar; Corning Inc., Corning, N.Y.) for 5 days. The medium was replaced every other day. Elutriated monocytes and MDM were 100% CD3−, ≥85% CD14+, and >95% HLA-DR+, as determined by flow cytometry.

Cell cultures.

To induce chemokine production, PBMCs or purified T cells were resuspended at 4 × 106 cells in 2 ml of RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 4 U of recombinant IL-2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) and incubated alone or in the presence of various stimuli in six-well plates. In some experiments, neutralizing antibodies specific to human IFN-γ (R&D Systems) were added at 2 μg/ml to the cultures of PBMCs. Five million elutriated monocytes were cultured in 2 ml of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% human serum in 15-ml conical tubes. Macrophages were derived from elutriated monocytes during 5 days of culturing as described above. HBa (at 108 organisms/ml) or LPS-Ba (at 3.0 or 0.3 μg/ml) was added to the PBMC, T cell, or monocyte cultures at the initiation of culturing. The same stimuli were added to macrophage cultures on day 5, and supernatants were collected after 24 and 48 h.

At various times, PBMCs, pure CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, monocytes, and macrophages were harvested, and total RNA was isolated to detect β-chemokine mRNA expression by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (see below). In addition, supernatants from the cultures of PBMCs, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, monocytes, and macrophages were harvested and analyzed for β-chemokine protein expression by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs).

β-Chemokine RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes, from monocytes, or from macrophages using RNAzol B solution (TelTest Inc., Friendswood, Tex.). cDNA was prepared from total RNA using oligo-dT primers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and Moloney murine leukemia virus RT enzyme (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Aliquots of cDNA were amplified by PCR using Taq polymerase (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primer pairs specific for MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES were synthesized at the CBER Core Facility (Bethesda, Md.) on the basis of previously published sequences (30): MIP-1α, 5′-CGC CTG CTG CTT CAG CTA CAC CTC CCG GCA GA-3′ (sense) and 5′-TGG ACC CCT CAG GCA CTC AGC TCC AGG TCG CT-3′ (antisense); MIP-1β, 5′-ACC CTC CCA CCG CCT GCT GCT TTT CTT CAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTT GCA GGT CAT ACA CGT ACT CCT GGA CCC-3′ (antisense); and RANTES, 5′-ACC ACA CCC TGC TGC TTT GCC TAC ATT GCC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTC CCG AAC CCA TTT CTT CTC TGG GTT GGC-3′ (antisense). Amplifications were performed for 28 cycles with denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 58°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min. The amplified products had predicted sizes of 195 bp for MIP-1α, 190 bp for MIP-1β, and 162 bp for RANTES. The β-actin mRNA-specific primers and PCR conditions were reported previously (36).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of intracellular staining for chemokine expression.

PBMCs were enriched for T cells by nylon wool separation and were cultured for 48 h in the presence of HBa at 108 organisms/ml, 2 × 106 cells/ml, 10 ml per flask. Monensin (10 μM; Sigma) was added for the last 10 h of cell culturing, and EDTA was added at 2 mM for the last 15 min of cell culturing. Cells were harvested, stained with a Cy-Chrome-conjugated anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) for 1 h on ice, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde solution for 10 min on ice, washed once with phosphate-buffered saline, and then permeabilized with a FIX & Perm kit (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Intracellular cytokine and chemokine expression was determined using phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibodies against IFN-γ or IL-4 (both reagents from BD Pharmingen) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibody against MIP-1α (BD Pharmingen) or MIP-1β (R&D Systems). Thirty thousand cells were collected per sample and analyzed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) with Cell Quest software. Spectral overlap between cells stained with specific antibodies and those incubated with PE-, Cy-Chrome-, and FITC-conjugated isotype controls was electronically compensated for using analogue subtraction.

Measurements of β-chemokine secretion by ELISAs.

Conditioned media from the cultures of PBMCs, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, monocytes, or MDM were collected and analyzed using ELISA kits specific for MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES according to the manufacturer's instructions (Endogen Inc., Woburn, Mass.).

HIV Env-dependent cell fusion assay.

CD4− 12E1 cells (generated in our laboratory [11]) were infected with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the envelope from JR-FL (R5 strain) at 10 PFU/cell. As targets we used PM1 cells that were derived from the Hut 78 cell line and shown to be susceptible to infection with both X4 and R5 viruses. PM1 cells are available through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (McKesson BioService Corp., Rockville, Md.). PM1 cells were mixed with 12E1 cells expressing the JR-FL envelope at a 1:1 ratio (105 cells each) and cocultured (in duplicate) for 4 to 5 h. Cell fusion activity was quantified by counting syncytia. Supernatants from B. abortus- and LPS-Ba-activated macrophages were added at several dilutions to PM1 cells for 1 h at 37°C before the addition of Env-expressing 12E1 cells.

In some experiments, a mixture of anti-MIP-1α and anti-MIP-1β antibodies (2 μg/ml each; R&D Systems) was added to the supernatants derived from the macrophage cultures for 1 h at room temperature. MIP-1α and MIP-1β (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, N.J.) and the supernatants derived from HBa- or LPS-Ba-activated macrophages pretreated with anti-β-chemokine antibodies were added to the target PM1 cells 1 h before the effector 12E1 (JR-FL Env-expressing) cells were added.

RESULTS

Induction of β-chemokine production in PBMCs by HBa.

It was recently suggested that HIV-1 vaccines that elicit the local production of R5-blocking β-chemokines may provide additional protection against infection or cell-to-cell spread of R5 strains (24). Since HBa was proposed as a carrier for therapeutic or prophylactic HIV vaccines and was shown to promote TH1- or TC1-type cytokines (11, 12, 13, 36), it was important to determine if HBa or LPS-Ba also generates β-chemokines in human cells. To address this question, peripheral blood lymphocytes were cultured in vitro in the presence of HBa, LPS-Ba, or a mixture of the polyclonal T-cell activators PHA and PMA. Low levels of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES in the supernatants of untreated PBMCs were detected by ELISAs (Table 1). HBa induced a significant increase in MIP-1α production (4- to 10-fold in four experiments) and a modest increase in MIP-1β secretion (2- to 4-fold) but only minimal or no induction of RANTES (1.1- to 1.5-fold) (Table 1 and data not shown). LPS derived from other gram-negative bacteria was shown to induce β-chemokine production from PBMCs and from macrophages (17, 34). Thus, it was of interest to determine the contribution of LPS in HBa to its β-chemokine-inducing activity. As shown in Table 1, LPS-Ba induced only a 2.8-fold increase in MIP-1α secretion and no increase in MIP-1β production in total PBMCs. In the same experiments, the PHA-PMA combination (maximal polyclonal activators) induced moderate increases in MIP-1α and RANTES production but not in MIP-1β secretion compared with the results for unstimulated cultures. In other experiments, the induction of MIP-1β mRNA and protein by PMA-PHA was observed (see below). The highest dose of LPS-Ba used (3 μg/ml) was previously found to be optimal in terms of human PBMC activation. These data suggest that the β-chemokine-inducing activity of HBa in total PBMCs could not be fully attributed to the activity of LPS-Ba.

TABLE 1.

Human PBMCs produce β-chemokines in response to HBa and LPS-Baa

| Cell treatmenta | Concn of:b

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MIP-1α | MIP-1β | RANTES | |

| None | 11.4 | 40.6 | 9.0 |

| HBa | 93.8 (8.2) | 98.1 (2.4) | 10.0 (1.1) |

| LPS-Ba | |||

| 3.0 μg/ml | 32.5 (2.8) | 40.9 (1.0) | 17.2 (1.9) |

| 0.3 μg/ml | 33.4 (2.9) | 38.1 (1) | 13.0 (1) |

| PHA-PMA | 65.0 (5.7) | 40.0 (0) | 40.2 (4.4) |

Human PBMCs at 2 × 106 cells/ml were incubated with HBa (108 organisms/ml), with LPS-Ba (3.0 or 0.3 μg/ml), or with a mixture of PMA at 10 ng/ml and PHA at 1 μg/ml for 24 h.

The concentrations (nanograms per milliliter) of chemokines in the culture supernatants were determined by ELISAs. Numbers in parentheses indicate the fold increase over the values for control cultures. Data represent four experiments.

Role of IFN-γ in β-chemokine production by HBa-activated PBMCs.

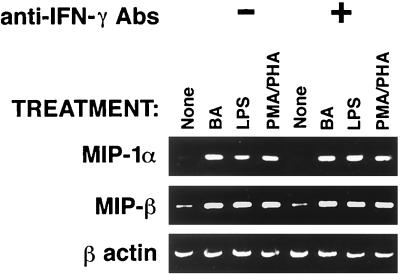

IFN-γ was shown to be a potent inducer of MIP-1α and MIP-1β in macrophages (35). In addition, earlier studies on the ability of HBa to induce TH1-type cytokines demonstrated that HBa induces IFN-γ in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (36). Therefore, it was possible that the observed increases in β-chemokine production in cultures of HBa-stimulated PBMCs were indirectly mediated by IFN-γ induced in these cultures. To test this hypothesis, PBMCs were incubated with various stimuli in the absence or presence of anti-IFN-γ neutralizing antibodies and β-chemokine mRNAs were measured several days before IFN-γ proteins could be detected in the supernatants (36). After 48 h of cell culturing, total RNA was isolated and the levels of MIP-1α and MIP-1β mRNAs were determined by RT-PCR (Fig. 1). HBa, LPS-Ba, and the mixture of PHA and PMA induced increases in the levels of β-chemokine mRNAs compared with the results for untreated PBMCs. No reduction in the levels of β-chemokine mRNAs was observed in the presence of anti-IFN-γ neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 1). In addition, no IL-12 was detected in these cultures at these early time points (data not shown). These data suggest that β-chemokine production is upregulated either by direct effects of HBa and LPS-Ba or by secondary mediators other than IFN-γ and IL-12 (33).

FIG. 1.

Effect of anti-IFN-γ antibodies (Abs) on β-chemokine mRNA induction in PBMCs activated with HBa or LPS-Ba. Human PBMCs were cultured with HBa at 108 organisms/ml, LPS-Ba at 3 μg/ml, or PHA and PMA at 1 μg/ml and 10 ng/ml, respectively, in the absence or presence of anti-IFN-γ antibodies at 2 μg/ml. Total RNA was isolated after 24 h and subjected to RT-PCR using primer pairs specific for MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, and β-actin.

CD8+ and not CD4+ T cells are the main source of β-chemokine secretion in B. abortus-activated human T cells.

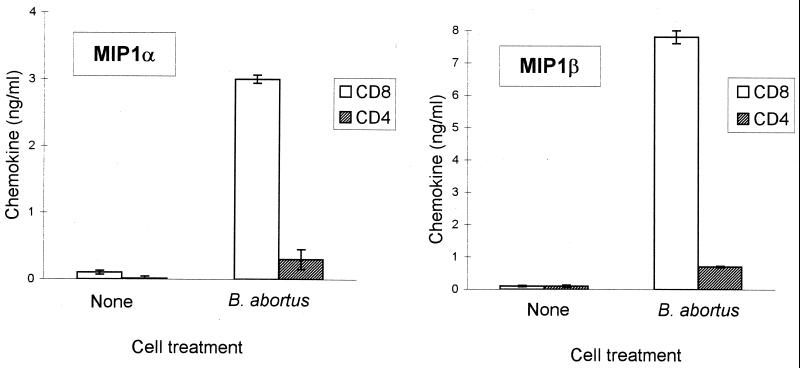

Since β-chemokine production was detected in HBa-activated PBMCs, it was of interest to determine which cell types, i.e., CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, or monocytes, produce chemokines in response to HBa. To distinguish among these possibilities, T cells were isolated from PBMCs using nylon wool purification and then were separated into subpopulations of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells using magnetic bead selection. Purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were cultured in vitro alone or with HBa, and supernatants of T-cell cultures were tested in ELISAs (Fig. 2). No significant production of chemokines was detected in these cultures during the first 3 days. The data depicted in Fig. 2 represent the results obtained with day 4 supernatants. No chemokines were detected in the supernatants of unstimulated CD8+ or CD4+ cells (Fig. 2). In CD8+ cells, HBa induced 21- and 14-fold increases in MIP-1α and MIP-1β production, respectively, but only a 1.5-fold increase in RANTES production (data not shown). In contrast, no significant increase in β-chemokine secretion was detected in CD4+ T cells stimulated with HBa (Fig. 2). The polyclonal activators PHA and PMA induced significant β-chemokine production in both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (data not shown). The inability to detect β-chemokines in the supernatants of HBa-stimulated CD4+ T cells was unexpected. Therefore, total RNA was isolated from activated T-cell subsets on day 3 of culturing and β-chemokine mRNA levels were measured by RT-PCR. Increases in MIP-1α and MIP-1β mRNAs were seen in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells stimulated with either HBa or the polyclonal activators PHA and PMA (Fig. 3). Therefore, the inability to detect β-chemokines in CD4+ T-cell culture supernatants may reflect a rapid adsorption of the secreted chemokines by activated (R5-positive) T cells or may be due to earlier blocks in chemokine translation and/or secretion in these cells (this notion is under investigation).

FIG. 2.

B. abortus-induced β-chemokine secretion primarily in CD8+ T cells. Purified CD4+ (hatched columns) and CD8+ (open columns) T cells were obtained by positive selection with magnetic beads and cultured with HBa (or medium) in triplicate. Day 4 supernatants were harvested and tested by ELISAs for the presence of MIP-1α and MIP-1β. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

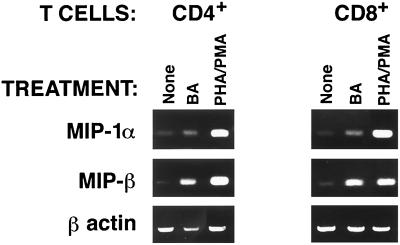

FIG. 3.

Induction of MIP-1α and MIP-1β mRNAs in purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells following activation with HBa. Bead-purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were cultured for 3 days in medium supplemented with 4 U of IL-2 and in the absence or presence of stimulation with HBa or with PHA and PMA. Total RNA was extracted, and RT-PCR to detect MIP-1α, MIP-1β, or β-actin mRNA was conducted as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

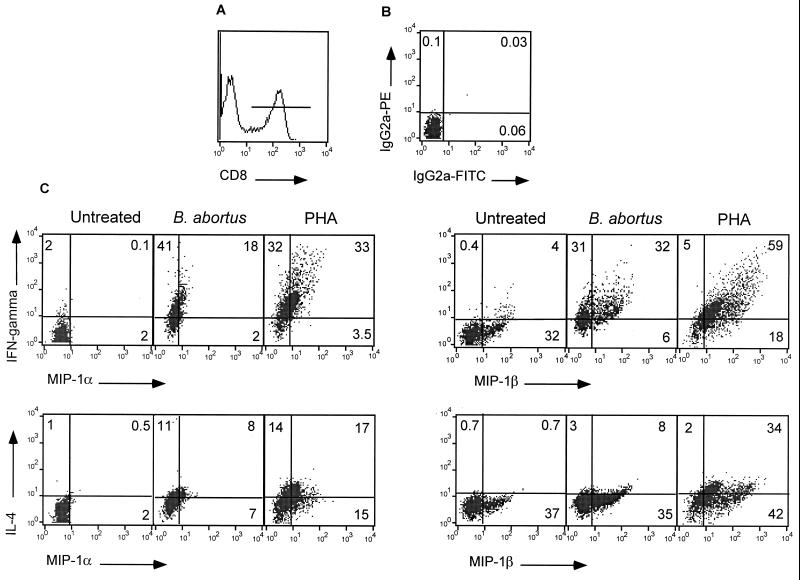

Intracellular staining for β-chemokines and IFN-γ or IL-4 in CD8+ T cells following short-term activation with HBa

B. abortus was shown to promote a TC1 or TH1 type of differentiation in both human and murine systems (13, 14, 36). To determine whether chemokine production in response to HBa occurs in polarized TC1 or TC2 CD8+ T cells (or in both), human T cells were cultured in vitro with HBa for 2 days and then subjected to three-color flow cytometry to analyze the levels of intracellular MIP-1α or MIP-1β in CD8+ T cells producing either IFN-γ or IL-4 (Fig. 4). No intracellular IFN-γ, IL-4, or MIP-1α proteins were detected in unstimulated CD8+ T cells. On the other hand, more than 30% of unstimulated CD8+ T cells contained MIP-1β intracellularly. This finding is in accord with the low level of constitutive MIP-1β mRNA transcription found in these cells (Fig. 1 and data not shown). Activation of T cells with HBa induced intracellular IFN-γ in 60 to 70% of CD8+ T cells and IL-4 in only 10 to 20% of CD8+ T cells (in three separate experiments), indicating a strong bias toward TC1-type cytokine production (Fig. 4). The frequencies of CD8+ T cells expressing intracellular MIP-1α and MIP-1β increased 2 days after stimulation with HBa to 20 to 25% and 38 to 45%, respectively, in three separate experiments. Importantly, 18% out of the 20% MIP-1α-positive cells and 32% out of the 38% MIP-1β-positive cells also stained positive for IFN-γ. Thus, almost 90% of CD8+ T cells staining positive for intracellular β-chemokines acquired a TC1-type phenotype following activation with HBa (Fig. 4). In contrast, only 8% out of 15% MIP-1α-positive cells and 8% out of 43% MIP-1β-positive cells coexpressed IL-4 (Fig. 4). Our analysis did not allow us to determine the number of unpolarized CD8+ T cells expressing both IFN-γ and IL-4. In contrast to HBa, the polyclonal activator PHA stimulated cytokine and chemokine production in a larger fraction of human CD8+ cells. Both TC1 (IFN-γ producers) (65%) and TC2 (IL-4 producers) (35%) were generated (Fig. 4). β-Chemokine production was observed primarily in IFN-γ-producing cells, but TC2 cells also contained intracellular MIP-1α (17%) and MIP-1β (34%) (Fig. 4). So, in agreement with previous studies, HBa behaved as a TH1-polarizing stimulus.

FIG. 4.

Three-color FACS analysis for intracellular chemokine and cytokine expression in CD8+ T cells activated with B. abortus. Human T cells were cultured with B. abortus for 48 h. Monensin was added to the cell cultures for the last 10 h. Cells were harvested, stained with Cy-Chrome-conjugated anti-CD8 antibodies (A), fixed with paraformaldehyde, permeabilized, and then stained with isotype control antibodies (B) or with PE-conjugated antibodies against either IFN-γ or IL-4 along with FITC-conjugated antibodies against MIP-1α or MIP-β (C). FACS analysis was performed on gated CD8+ T cells as shown in panel A. Numbers represent percentages of cells falling into each quadrant. Data represent three experiments. IgG2a, immunoglobulin G2a.

Monocytes and macrophages secrete high levels of MIP-1α and MIP-1β in the presence of HBa.

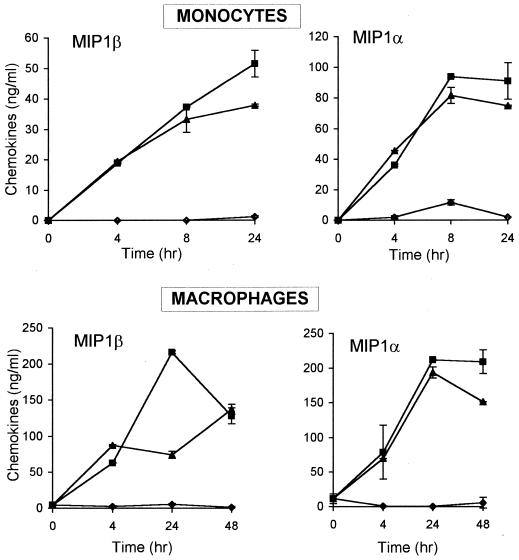

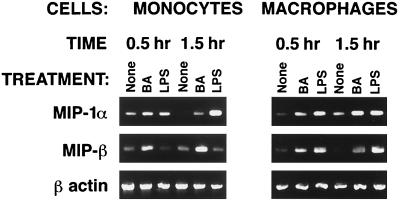

Since significant β-chemokine secretion was detected in cultures of total PBMCs but not of purified T cells after 24 h of stimulation with HBa, it was conceivable that the source of β-chemokines at the early time points was not T cells but monocytes. To address this possibility, elutriated human monocytes or MDM were cultured alone or in the presence of HBa or LPS-Ba, and culture supernatants were evaluated for chemokine production at various time points (Fig. 5). MIP-1α and MIP-1β were both detected in cultures of activated monocytes and macrophages as early as 4 h after initiation of the cell cultures; maximum chemokine production was observed between 8 and 24 h (Fig. 5). Similar kinetics and levels of β-chemokine production were observed in cultures of HBa- or LPS-Ba-stimulated monocytes and macrophages. Monocytes secreted somewhat higher levels of MIP-1α than MIP-1β, and in most cultures, macrophages produced significantly higher levels of β-chemokines than did monocytes following HBa or LPS-Ba stimulation. No RANTES was detected in any of the monocyte or MDM supernatants. To determine if the early secretion of β-chemokines reflected a release of preformed chemokines from intracellular stores or new transcription, total RNA was collected from unstimulated or HBa-stimulated cells after 0.5 and 1.5 h of culturing. As shown in Fig. 6, in most samples, a very low level of or no chemokine mRNA was detected in unstimulated macrophages and monocytes. Following stimulation with HBa or LPS-Ba, mRNAs of both MIP-1α and MIP-1β were induced within 0.5 h (Fig. 6).

FIG. 5.

Kinetics of MIP-1α and MIP-1β chemokine production by monocytes and macrophages activated in vitro with HBa or with LPS-Ba. Monocytes and MDM (5 × 106 per well) were incubated alone (♦) or in the presence of HBa (▪) or LPS-Ba (▴). Supernatants were harvested at the indicated times and tested for chemokine production by ELISAs. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

FIG. 6.

Early induction of MIP-1α and MIP-1β mRNA transcription in monocytes and macrophages in response to HBa. Human elutriated monocytes and 5-day MDM were incubated alone or with LPS-Ba. After 0.5 and 1.5 h, cells were harvested and total RNA was isolated. RT-PCR was performed using primer pairs specific for MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and β-actin. Results are representative of three experiments.

MIP-1α and MIP-1β mRNAs are expressed in monocytes and macrophages early after activation with HBa.

Since β-chemokines were detected in culture supernatants from HBa-activated monocytes and macrophages at 4 h, it was of interest to determine the minimum time required for the induction of their mRNAs. Total RNA was collected from monocytes and macrophages 0.5 and 1.5 h after stimulation with HBa or LPS-Ba. RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that low levels of MIP-1α and MIP-1β mRNAs were present in unstimulated cells. Both mRNAs were significantly upregulated after 30 min of stimulation with HBa (Fig. 5 and data not shown). LPS-Ba consistently upregulated β-chemokine mRNA to higher degrees in differentiated macrophages than in monocytes (Fig. 6). The rapid secretion of β-chemokines in monocytes or macrophages may be accounted for partly by the release of preformed or stored chemokines (as recently demonstrated for IL-12 in some cells [28]) and by the rapid upregulation of transcription and translation following stimulation with HBa or LPS-Ba.

Fusion inhibition activity of supernatants derived from macrophages activated in vitro with HBa or with LPS-Ba

MIP-1α and MIP-1β were shown to mediate the inhibition of HIV-1 infection of PBMCs with macrophage-tropic (R5-dependent) HIV-1 strains (4). To determine if the amounts of β-chemokines produced by HBa-activated monocytes and macrophages are sufficient for inhibition of HIV-1 cell entry, a surrogate, viral envelope-dependent cell fusion assay was performed. Human PM1 cells expressing both CD4 and HIV-1 coreceptors (R5 and X4) were mixed with 12E1 effector cells expressing the R5 envelope (JR-FL) in the absence or presence of supernatants derived from macrophages activated with either HBa or LPS-Ba for 24 or 48 h. High numbers of syncytia were scored in cultures of PM1 cells and effector cells in the presence of control supernatants from untreated macrophages (Table 2). On the other hand, the addition of supernatants from macrophages activated with HBa for 24 h (diluted 1:2 or 1:20) completely blocked syncytium formation (Table 2). At a 1:200 dilution, the fusion inhibition activity of supernatants from HBa-activated macrophages was greatly reduced. A similar pattern of fusion inhibition was observed with supernatants from macrophages activated with LPS-Ba. However, lower inhibitory activity was detected in the 1:20-diluted supernatants from LPS-Ba-stimulated cells than in HBa-induced supernatants at this dilution. This finding could be explained by the somewhat lower levels of β-chemokines detected in LPS-Ba-treated macrophages than in HBa-treated macrophages (Fig. 5 and Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Fusion of PM1 cells with R5 envelope-expressing 12E1 cells is inhibited by supernatants from HBa- or LPS-Ba-stimulated macrophages and monocytesa

| Supernatant source | Treatment | Supernatant dilution | No. of syncytia (% inhibition) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macrophages | None | None | 199 ± 23 (0) |

| HBa | 1:2 | 2 ± 1 (99) | |

| 1:20 | 4 ± 1 (98) | ||

| 1:200 | 102 ± 13 (49) | ||

| LPS-Ba | 1:2 | 1 ± 1 (99) | |

| 1:20 | 27 ± 3 (86) | ||

| 1:200 | 149 ± 4 (25) | ||

| Monocytes | HBa | 1:2 | 11 ± 2 (95) |

| 1:20 | 24 ± 1 (88) | ||

| 1:200 | 112 ± 32 (44) | ||

| LPS-Ba | 1:2 | 12 ± 1 (94) | |

| 1:20 | 76 ± 1 (62) | ||

| 1:200 | 158 ± 5 (21) |

The data were generated with supernatants from 24-h cultures. Similar results were obtained with 48-h culture supernatants. Data represent three experiments. PM1 cells (CD4+ R5 positive) were mixed (1:1 ratio) with 12E1 cells (CD4− R5 negative) infected with vCB28 recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the R5 envelope (JR-FL). Syncytia were scored after 5 h; data are given as means and standard errors of the means. Monocyte or macrophage supernatants at the indicated dilutions were added to PM1 cells for 1 h at 37°C prior to the addition of 12E1 effector cells. The percent inhibition values were calculated in comparison with the effects of 24-h supernatants from unstimulated macrophages or monocytes cultured under the same conditions.

Similar inhibitory effects on the fusion of PM1 cells with R5 envelope-expressing 12E1 cells were obtained with supernatants derived from cultures of elutriated monocytes stimulated with HBa or with LPS-Ba for 24 h (Table 2) and with 48-h supernatants from cultures of both macrophages and monocytes (data not shown). The inhibitory activities of the macrophage- and monocyte-derived supernatants in the HIV fusion assay correlated well with the high levels of MIP-1α and MIP-1β in these supernatants. In the same experiments, recombinant chemokines MIP-1α and MIP-1β both inhibited the fusion of PM1 cells with R5 envelope-expressing cells in a dose-dependent fashion (Table 3). However, at this point, we could not exclude the possibility that other soluble factors with inhibitory activity in the fusion assay were also produced by HBa-stimulated macrophages and monocytes.

TABLE 3.

Inhibitory activities of MIP-1α and MIP-1βa

| Inhibitor | Dose (μg/ml) | No. of syncytia (% inhibition) |

|---|---|---|

| MIP-1α | 1.0 | 6 ± 1 (97%) |

| 0.1 | 99 ± 12 (50%) | |

| MIP-1β | 1.0 | 1 ± 1 (99%) |

| 0.1 | 21 ± 4 (89%) |

Data for syncytia are given as means and standard errors of the means.

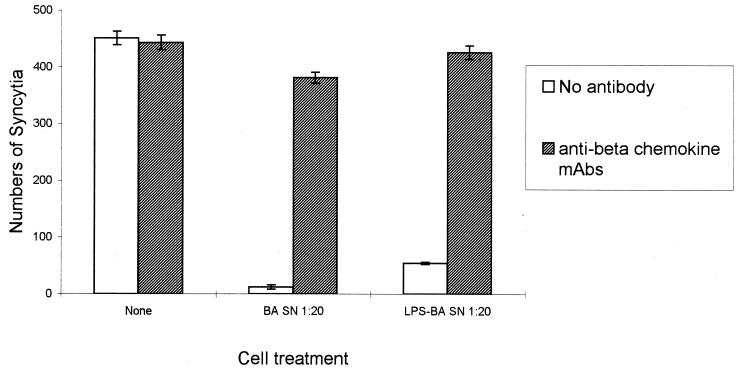

Anti-MIP-1α and anti-MIP-1β antibodies reverse the fusion inhibition effect of supernatants from HBa-activated macrophages.

It was important to formally demonstrate that the inhibition of fusion observed in the presence of macrophage (or monocyte)-derived supernatants was mediated by the β-chemokines in these supernatants. Therefore, supernatants derived from macrophages cultured with either HBa or LPS-Ba were pretreated with a combination of anti-MIP-1α and anti-MIP-1β antibodies (or isotype control mouse antibodies) and then added to the fusion assay. Supernatants derived from macrophages cultured with HBa or with LPS-Ba inhibited fusion when used at 1:2 (data not shown) and at 1:20 (Fig. 7) dilutions. The inhibitory effects were greatly reduced after treatment of the supernatants with the MIP-1α- plus MIP-1β-specific antibodies (but not with the control antibodies) for 1 h at 37°C. These results demonstrate that the β-chemokines induced in cultures of HBa-activated macrophages were biologically active and were the main factors responsible for the inhibition of R5 envelope-mediated cell fusion. Similar findings were obtained with monocyte-derived supernatants (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Antibodies against MIP-1α and MIP-1β abrogate the fusion inhibition activity found in supernatants of HBa-activated macrophages. Macrophages were left unactivated or were stimulated with either HBa or LPS-Ba for 48 h. Supernatants (SN) were diluted 1:20 with culture medium and were left untreated or were treated with anti-MIP-1α and anti-MIP-1β antibodies (at 2 μg/ml each) (hatched columns) or with isotype control antibodies (open columns). PM1 cells expressing CD4 and R5 were mixed 1:1 with JR-FL envelope-expressing 12E1 cells in the presence of supernatants derived from untreated macrophages (none) or supernatants derived from HBa-activated macrophages either left untreated (open columns) or pretreated with anti-MIP-1α and anti-MIP-1β antibodies (hatched columns). Syncytia were scored after 5 h. Data are presented as the mean numbers of syncytia and standard errors of the mean from triplicate cultures. mAbs, monoclonal antibodies.

DISCUSSION

Efforts to design successful prophylactic or therapeutic HIV vaccines have been hampered by the lack of knowledge regarding the immune mechanisms required for protection and viral elimination in infected individuals. In addition to virus-specific neutralizing antibodies and cytotoxic T cells, it was suggested recently that the in vivo generation of non-antigen-specific mediators, such as β-chemokines, known to bind to one of the primary HIV-1 coreceptors, R5, could be of added value. Thus, it was important to determine if HBa, a candidate vaccine carrier for HIV-1 vaccines, could also elicit β-chemokines in human cells.

The main findings of the current study were (i) HBa elicits the production of the β-chemokines MIP-1α and MIP-1β but not RANTES from human PBMCs; (ii) the induction of these β-chemokines could not be attributed to a secondary effect mediated by IFN-γ in these cultures; (iii) among purified T cells, CD8+ cells were the main source of secreted β-chemokines, although the upregulation of MIP-1α and MIP-1β mRNAs was observed in both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells after HBa stimulation; (iv) the majority of β-chemokine-secreting CD8+ T cells also produced IFN-γ (TC1), but a small subset of IL-4-producing cells (TC2) coexpressing β-chemokine proteins was detected by intracellular staining; and (v) high levels of β-chemokine production, with rapid kinetics, were observed in elutriated monocytes, and even higher levels were observed in macrophages stimulated with either HBa or LPS-Ba. Importantly, the β-chemokines generated in these cultures were effective in blocking HIV-1 R5 envelope-mediated cell fusion, and the inhibition of fusion could be reversed by antibodies specific for MIP-1α and MIP-1β.

Following the detection of MIP-1α and MIP-1β production in total PBMCs, a systematic approach was taken to identify which cell types within PBMCs were secreting β-chemokines in response to HBa and LPS-Ba. Monocytes, macrophages, and pure T-cell subsets were studied. For T cells, an effort was made to further categorize the responding cells as either TH1 and TC1 or TH2 and TC2 by using three-color intracellular staining. It was found that HBa could induce MIP-1α and MIP-1β (but not RANTES) production and secretion in subsets of purified T cells; however, the kinetics of T-cell activation were much slower than those seen with monocytes and macrophages, and the total amount of β-chemokine secretion by T cells was at least 10-fold lower.

It was previously found that HBa can induce TH1-type cytokines (IL-2 and IFN-γ) in both CD4+ and CD8+ human T cells (36). Surprisingly, in the current study, we detected MIP-1α and MIP-1β primarily in culture supernatants of CD8+ T cells. Three-color FACS analysis indicated that most of the β-chemokine production occurred primarily in TC1 cells that expressed intracellular IFN-γ following HBa stimulation. In contrast, the polyclonal activator PHA induced β-chemokine production in both TC1 and TC2 cells. Although no β-chemokines could be detected in supernatants from HBa-stimulated CD4+ T cells, RT-PCR analyses detected the induction of β-chemokine mRNA in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells stimulated with either HBa or the polyclonal activators PHA and PMA. There may be a posttranscriptional block in the translation or in the transport and release of β-chemokines in these cells (this notion is under investigation). On the other hand, it is conceivable that CD4+ T cells do secrete low levels of β-chemokines in response to HBa (and possibly other bacterial or viral stimulation) but that most of the secreted chemokines immediately bind to R5 expressed by activated CD4 cells and are therefore not detected in culture supernatants. This hypothesis is supported by the work of Annunziato et al. with polarized human TH1 CD4+ cell lines (1). Such a mechanism may also be operative in vivo in long-term nonprogressor patients, as previously demonstrated (29, 31).

With regard to CD8+ T cells, other laboratories also found that a subset of memory CD8+ cells (CD45R0+ CD28+ CD38lo) is the predominant source of MIP-1β after polyclonal stimulation with PMA plus ionomycin or LPS, as determined by intracellular staining (R. Kamin-Lewis, personal communication). It will be important to determine if long-term memory T cells generated in mice following vaccination with HBa-protein conjugates secrete β-chemokines upon secondary stimulation. Our data also demonstrate for the first time that a significant percentage of human CD8+ T cells contains preformed intracellular MIP-1β (but not MIP-1α). We did not determine the memory phenotype of these cells, but it may be intriguing to determine if it is mainly memory CD8+ T cells that maintain constitutive MIP-1β production. It was recently reported that some dendritic cells contain preformed stores of IL-12 p70 intracellularly and rapidly release them upon cell activation (28). Therefore, the storing of intracellular cytokines or chemokines ready to be released upon cell activation may be a more general mechanism ensuring rapid early responses to infectious agents and/or inflammation.

Previous work from several groups demonstrated that LPS from other gram-negative bacteria can elicit potent β-chemokine production in monocytes and macrophages (17, 34). However, the LPS of B. abortus differs structurally from the LPSs of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi and was shown to be much less pyrogenic in rabbits and mice and to induce less tumor necrosis factor alpha production from human monocytes (2, 15). These properties make B. abortus a safer candidate for vaccine production. Thus, it was important to demonstrate that HBa and/or LPS-Ba elicit biologically important cytokines and chemokines. In previous studies, HBa and LPS-Ba induced IL-12 production and upregulated B7.1, B7.2, and ICAM-1 in human monocytes (37). In addition, HBa activated murine dendritic cells to secrete IL-12 and to migrate to the T-cell areas in the spleen (13; L.-Y. Huang, C. Reis e Sousa, Y. Itoh, J. Inman, and D. E. Scott, submitted for publication). The current study demonstrates that HBa and LPS-Ba also induce biologically relevant quantities of MIP-1α and MIP-1β from both monocytes and differentiated macrophages, with very rapid kinetics. Treatment of human macrophages with exogenous IFN-γ was shown recently to induce MIP-1α and MIP-1β production (35). However, in the current study, we used pure monocytes and macrophages (i.e., no source of IFN-γ), and in the case of total PBMCs, we could not block β-chemokine mRNA induction with anti-IFN-γ neutralizing antibodies. These data suggest that the upregulation of MIP-1α and MIP-1β transcription in macrophages, monocytes, or total PBMCs was most likely mediated by direct HBa signaling and not by secondary mediators.

Previous and current findings indicate that LPS-Ba is an important component contributing to the immunomodulating properties of HBa in monocytes and macrophages. However, in multiple studies (with murine and human cells), HBa was found to be a more potent stimulator of dendritic cells, macrophages, and T cells than LPS-Ba (at saturating concentrations). Taken together, the data suggest that other bacterial components (e.g., DNA or cell wall components) also contribute to the activation potential of HBa in different cell types.

The cell receptor(s) involved in B. abortus stimulation of monocytes, macrophages, or T cells is unknown. Triggering of monocytes or macrophages may be due in part to LPS stimulation of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). However, in mice, B. abortus was able to stimulate tumor necrosis factor alpha secretion from non-LPS-responsive mice that lacked TLR4, suggesting that other TLRs may be involved (C. Huang and B. Golding, unpublished data). A recent report showed that an outer membrane protein from gram-negative bacteria signals via TLR2 on dendritic cells (20). This could also be true for B. abortus. Evidence obtained here and from previous experiments (36) indicated that highly purified T cells could be stimulated by B. abortus to secrete cytokines. It is possible that T cells bear receptors that belong to the TLR family but are yet to be discovered.

The current findings provide an important addition to the properties of HBa as a potential carrier for therapeutic HIV vaccines. Recently, Lehner et al. put forward the idea that both antigen-specific and nonspecific immune mechanisms may be necessary for effective mucosal protection against HIV-1 transmission (24). Virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as antibody responses to immunizing viral antigens play a primary protective role and make up the pool of long-term memory cells. In addition, the generation of innate antiviral factors, such as β-chemokines, may have an important antiviral effect by downmodulating or blocking R5, the coreceptor most widely used by newly transmitted HIV-1 strains (24). The latter group demonstrated with a macaque-SIV infection model that protection against rectal SIV challenge in animals immunized with a mixture of soluble proteins in alum correlated with immunoglobulin A secretion at the mucosal surface as well as high levels of systemic β-chemokines (16, 23). A reverse correlation was found between the levels of β-chemokine production and R5 expression on CD4+ T cells (25).

Due to its ability to directly elicit IL-2 and IFN-γ from CD8+ T cells, it was predicted that HBa conjugated to viral proteins would stimulate effector mechanisms in CD4+ T-cell-deficient mice. Indeed, HIV-1-specific neutralizing antibodies and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells could be generated not only in normal mice but also in mice depleted of CD4+ T cells (to mimic the situation in AIDS patients) (10, 11, 22, 32). The current findings further extend these properties of HBa, demonstrating that it can elicit significant amounts of R5-inhibiting β-chemokines from human CD8+ T cells as well as human monocytes and macrophages. Most of the fusion inhibition activities in the supernatants were blocked by a mixture of anti-MIP-1α and anti-MIP-1β antibodies. However, it is still possible that other molecules capable of blocking HIV-1 cell entry are also produced by HBa-activated cells.

One of the risks associated with vaccination of HIV-1-infected individuals is the possibility that the immune stimulation will result in viral reactivation and spread in responding and neighboring cells. Thus, in the context of a therapeutic HIV-1 vaccine, the local production of β-chemokines capable of blocking R5 on target cells (i.e., CD4+ T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells) is highly desirable and may be sufficient to block local viral spread. Taken together, these findings support the proposed use of HBa as a vaccine carrier for HIV-1 proteins in therapeutic (or prophylactic) vaccines. HBa could also be considered for vaccination in other conditions associated with depressed T-helper cell function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are thankful to Richard Kenney and Dorothy Scott for critical review of the manuscript.

These studies were supported by a grant from the NIH Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program (IATAP).

REFERENCES

- 1.Annunziato F, Galli G, Nappi F, Cosmi L, Manetti R, Maggi E, Ensoli B, Romagnani S. Limited expression of R5-tropic HIV-1 in CCR5-positive type 1 polarized T cells explained by their ability to produce RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β. Blood. 2000;95:1167–1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betts M, Beining P R, Inman J, Brunswick M, Hoffman T, Golding B. Lipopolysaccharide from Brucella abortus behaves as a T-cell-independent type 1 carrier in murine antigen-specific antibody responses. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1722–1729. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1722-1729.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blay R, Clerici M, Lucey D, Hendrix C, Hoffman T, Golding B. Brucella abortus stimulates human T cells from uninfected and infected individuals to secrete IFNγ. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1992;8:479–486. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cocchi F, DeVico A L, Garzino-Demo A, Cara A, Gallo R C, Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β as the major HIV suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270:1181–1185. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley G A, Smith M W, Allikmets R, Goedert J J, Buckbinder S P, Vittingholff E, Gomperts E, et al. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion of the CKR5 structural allele. Science. 1996;273:1856–1862. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng H K, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drajic T, Litwin V, Allaway G P, Martin S R, Huang Y, Nagashima K A, Cayanan C, Maddon P J, Koup R A, Moore J M, Paxton W A. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng Y, Broder C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane G protein coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garzini-Demo A, Moss R B, Margolick J B, Cleghorn F, Sill A, Blattner W A, Cocchi F, Carlo D J, DeVico A L, Gallo R C. Spontaneous and antigen-induced production of HIV-inhibitory β-chemokines are associated with AIDS-free status. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11986–11991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golding B, Golding H, Preston S, Hernandez D, Beining P R, Manischewitz J, Harvath L, Blackburn R, Lizzio E, Hoffman T. Production of a novel antigen by conjugation of HIV-1 to Brucella abortus: studies of immunogenicity, isotype analysis, T-cell dependency, and syncytia inhibition. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1991;7:435–436. doi: 10.1089/aid.1991.7.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golding B, Inman J, Highet P, Blackburn R, Manischewitz J, Blyveis N, Angus R D, Golding H. Brucella abortus conjugated with gp120 or V3-loop peptides derived from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 induces neutralizing antibodies even after CD4+ T-cell depletion. J Virol. 1995;69:3299–3307. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3299-3307.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golding B, Inman J, Golding H. Design of vaccines for the induction of antibody responses in Th-cell deficient individuals. In: Gregoriades G, editor. Vaccines: new-generation immunological adjuvants. Vol. 282. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1995. p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golding B, Scott D E, Scharf O, Huang L, Zaitseva M, Lapham C, Eller N, Golding H. Immunity and protection against Brucella abortus. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:43–48. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golding H, Zaitseva M, Inman J J, Golding B, Lapham C. Strategies for the stimulation of CD4/CD8 T subsets. In: Gregoriades G, editor. Vaccines: new generation immunological adjuvants. Vol. 282. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1995. p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein J, Hoffman T, Frasch C, Lizzio E L, Beining P R, Hochstein D, Lee Y L, Angus R D, Golding B. Lipopolysaccharide from Brucella abortus is less toxic than lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli, suggesting the possible use of B. abortus as a carrier in vaccines. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1385–1389. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1385-1389.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heeney J L, Teeuwsen V J, van Gils M, Bogers W M, De Guili M C, Radaelli A, Barnett S, Morein B, Akerblom L, Wang Y, Lehner T, Davis D. Beta chemokines and neutralization antibody titers correlate with sterilizing immunity generated in HIV-1 vaccinated macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10803–10808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hone D M, Powell J, Crowley R W, Maneval D, Lewis G K. Lipopolysaccharide from an Escherichia coli htrB msbB mutant induces high levels of MIP-1α and MIP-1β secretion without inducing TNF-α and IL-1β. J Hum Virol. 1998;1:251–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang L-Y, Krieg A M, Eller N L, Scott D E. Induction and regulation of Th1-inducing cytokines by bacterial DNA, lipopolysaccharide, and heat-inactivated bacteria. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6257–6263. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6257-6263.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Y, Paxton W A, Wolinsky S M, Neumann A U, Zhang L, He T, Kang S, Ceradini D, Jin Z, Yazdanbaksh K, et al. The role of a mutant CCR5 allele in HIV-1 transmission and disease progression. Nat Med. 1996;2:1240–1243. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeannin P, Renno T, Goetsch L, Miconnet I, Aubry J-P, Delneste Y, Herbault N, Baussant T, Magistrelli G, Soulas C, Romero P, Cerottini J-C, Bonnefoy J-Y. OmpA targets dendritic cells, induces their maturation and delivers antigen into the MHC class I presentation pathway. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:502–509. doi: 10.1038/82751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lapham C K, Ouyang J, Chandrasekhar B, Nguyen N Y, Dimitrov D S, Golding H. Evidence for cell-surface association between fusin and the CD4-gp120 complex in human cell lines. Science. 1996;274:602–605. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lapham C K, Golding B, Inman J, Blackburn R, Manischewitz J, Highet P, Golding H. Brucella abortus conjugated with a peptide derived from the V3 loop of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 induces HIV-specific cytotoxic T-cell responses in normal and in CD4+ cell-depleted BALB/c mice. J Virol. 1996;70:3084–3092. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3084-3092.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehner T, Wang Y, Cranage M, Bergmeier L A, Mitchell E, Tao L, Hall G, Dennis M, Cook N, Brookes R, Klavinskis L, Jones I, Doyle C, Ward R. Protective mucosal immunity elicited by targeted iliac lymph node immunization with a subunit SIV envelope and core vaccine in macaques. Nat Med. 1996;2:767–775. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehner T, Bergmeier L, Wang Y, Tao L, Mitchell E. A rational basis for mucosal vaccination against HIV infection. Immunol Rev. 1999;170:183–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehner T, Wang Y, Carnage M, Tao L, Mitchell E, Bravery C, Doyle C, Paratt K, Hall G, Dennis M, Villinger L, Bergmeier L. Up-regulation of beta chemokines and down-modulation of CCR5 co-receptors inhibit simian immunodeficiency virus transmission in non-human primates. Immunology. 2000;99:569–577. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00993.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu R, Paxton W A, Choe S, Ceradini D, Martin S R, Horuk R, MacDonald M E, Stuhlmann H, Koup R A, Landau N R. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86:367–378. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majka M, Rozmyslowicz T, Lee B, Murphy S L, Pietrzkowski Z, Gaulton G N, Silberstein L, Ratajczak M Z. Bone marrow CD34(+) cells and megakaryoblasts secrete β-chemokines that block infection of hematopoietic cells by M-tropic R5 HIV. J Clin Investig. 1999;104:1739–1749. doi: 10.1172/JCI7779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quinones M, Ahuja S K, Melby P C, Pate L, Reddick R L, Ahuja S S. Preformed membrane-associated stores of interleukin (IL)-12 are a previously unrecognized source of bioactive IL-12 that is mobilized within minutes of contact with an intracellular parasite. J Exp Med. 2000;192:507–515. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saha K, Bentsman G, Chess L, Volsky D. Endogenous production of β-chemokines by CD4+, but not CD8+, T-cell clones correlates with the clinical state of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected individuals and may be responsible for blocking infection with non-syncytium-inducing HIV-1 in vitro. J Virol. 1998;72:876–881. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.876-881.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samson M, Libert F, Doranz B J, Rucker J, Liesnard C, Farber C M, Saragosi S, Lapoumeroulie C, Cogniaux J, Forceille C, et al. Resistance to HIV-1 infection of Caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CKR5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature. 1996;382:722–725. doi: 10.1038/382722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schrum S, Probst P, Fleischer B, Zipfel P F. Synthesis of β-chemokines MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES is associated with a type I immune response. J Immunol. 1996;157:3598–3604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott D E, Golding H, Huang L-Y, Inman J, Golding B. HIV peptide conjugated to heat-killed bacteria promotes antiviral responses in immunodeficient mice. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1998;14:1263–1269. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tough D F, Sun S, Sprent J. T cell stimulation in vivo by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) J Exp Med. 1997;185:2089–2094. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.12.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verani A, Scarlatti G, Comar M, Tresoldi E, Polo S, Giacca M, Lusso P, Siccardi A G, Vercelli D. C-C chemokines released by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated human macrophages suppress HIV-1 infection in both macrophages and T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:805–816. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaitseva M, Lee S, Lapham C, Taffs R, King L, Romantseva T, Manischewitz J, Golding H. Interferon gamma and interleukin 6 modulate the susceptibility of macrophages to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Blood. 2000;96:3109–3117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaitseva M B, Golding H, Betts M, Yamauchi A, Bloom E T, Butler L E, Stevan L, Golding B. Human peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cells express Th1-like cytokine mRNA and proteins following in vitro stimulation with heat-inactivated Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2720–2728. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2720-2728.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaitseva M B, Golding H, Manischewitz J, Webb D, Golding B. Brucella abortus as a potential vaccine candidate. Induction of interleukin-12 secretion and enhanced B7.1, B7.2, and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 surface expression in elutriated monocytes stimulated by heat-inactivated B. abortus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3109–3117. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3109-3117.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Moore J P. Will multiple coreceptors need to be targeted by inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry? J Virol. 1999;73:3443–3448. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3443-3448.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]