Abstract

Interferon γ (IFNγ) produced by T cells represents the featured cytokine and is central to the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis (LN). Here, we identified nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), the rate-limiting enzyme in the salvage NAD+ biosynthetic pathway, as playing a key role in controlling IFNγ production by CD4+ T cells in LN. Our data revealed that CD4+ T cells from LN showed an enhanced NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthetic process, which was positively correlated with IFNγ production in CD4+ T cells. NAMPT promoted aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration in CD4+ T cells from patients with LN or MRL/lpr mice through the production of NAD+. By orchestrating metabolic fitness, NAMPT promoted translational efficiency of Ifng in CD4+ T cells. In vivo, knockdown of NAMPT by small interfering RNA (siRNA) or pharmacological inhibition of NAMPT by FK866 suppressed IFNγ production in CD4+ T cells, leading to reduced inflammatory infiltrates and ameliorated kidney damage in lupus mice. Taken together, this study uncovers a metabolic checkpoint of IFNγ-producing CD4+ T cells in LN in which therapeutically targeting NAMPT has the potential to normalize metabolic competence and blunt pathogenicity of CD4+ T cells in LN.

Keywords: lupus nephritis, NAMPT, metabolic checkpoint, IFNγ expression, translation efficiency

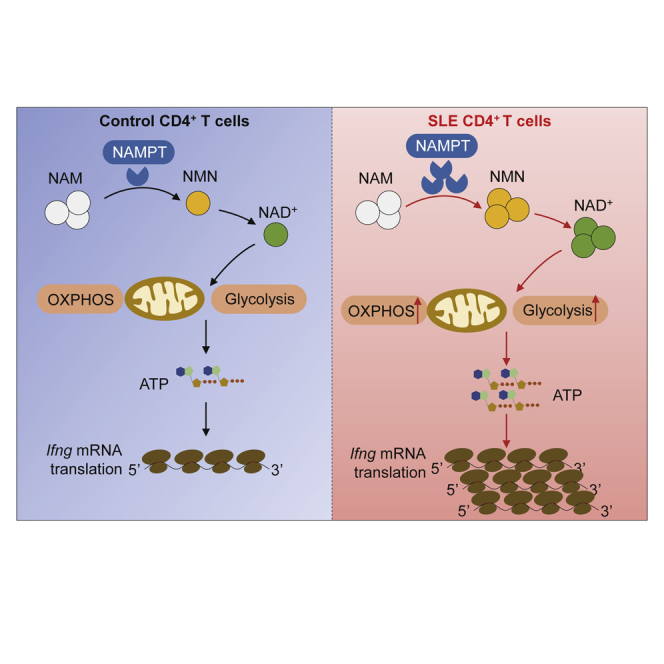

Graphical abstract

The study by Li et al. uncovers the novel functions and mechanism insights of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) in enhancing Ifng translation and driving proinflammatory CD4+ T cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. These findings link NAMPT to the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus, providing a molecular basis for development of novel therapeutics.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the prototype of autoimmune disease that involves multiple organs and systems.1 Lupus nephritis (LN) is one of the most severe conditions of SLE. SLE is characterized by the loss of immune tolerance that causes overactivation of adaptive immunity, resulting in immune deposition and leukocyte infiltration.2,3 The generation of autoreactive CD4+ T cells is critical for the development and progression of LN.4 The underlying mechanisms for autoreactive T cell response in LN remain to be further elucidated.

Interferon γ (IFNγ) signaling is important for the activation of immune cells.5,6 IFNγ-producing CD4+ T cells are the hallmark of proinflammatory T helper (Th) cells and play a critical role in human autoimmune diseases.7,8 Early studies have revealed that IFNγ-producing CD4+ T cells are one of the causal factors in the pathogenesis of SLE. Gene expression profiles reveal that higher levels of IFNγ-induced transcripts are characterized in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from SLE patients.9 In LN, data from single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) show that IFNγ is a main driver of immune activation in the kidney.10 Moreover, IFNγ induces lupus-like autoimmune disease in patients with myeloproliferative disorders.11 IFNγ receptor deficiency prevented the initiation and development of kidney disease in lupus-prone mice.12 However, the regulation of IFNγ expression in SLE is not clear yet.

Metabolic dysregulation of immune cells is emerging as a hallmark of autoimmune diseases.13 The activation of autoreactive T cells relies heavily on cellular bioenergetic strategies.14 T cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis show defects in mitochondrial respiration.15 Targeting the glycolytic enzyme of pyruvate kinase M2 limits the development of proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 cells in vitro and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in vivo.16 In SLE, CD4+ T cells show enhanced aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration.17 However, the metabolic profile of CD4+ T cells from patients with SLE needs further investigation. Data regarding the mechanisms of dysregulated T cell metabolism in SLE are limited.

Nicotinamide (NAM) adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), as a coenzyme, is central to cellular metabolism, DNA repair, and cell survival.18 NAD+ is synthesized via three distinct but interconnected pathways: the de novo biosynthetic pathway, the Preiss-Handler pathway, and the salvage pathway.18 In mammals, the salvage pathway represents the predominant NAD+ biosynthetic pathway. NAM phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) is the rate-limiting enzyme in the salvage pathway that metabolizes NAM to NAM mononucleotide (NMN), which is then converted into NAD+.19

NAMPT was originally identified as a cytokine that acted as a co-factor for B cell maturation and was termed pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF) initially.20 It has been shown that NAMPT has a crucial role in immune response in both cancer and autoimmune diseases. As in cancer, NAMPT inhibits CXCR4 expression and prevents the mobilization of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment.21 In contrast, NAMPT expression in tumor cells drives the expression of PD-L1 and governs tumor immune evasion in a CD8+ T cell-dependent manner.22 Moreover, NAMPT expression is increased in macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide, and loss of NAMPT alters their inflammatory potential.23 In a mouse model of inflammatory bowel diseases, NAMPT inhibition by FK866 results in ameliorated colitis by modulating monocyte/macrophage biology and macrophage polarization.24 In addition, knockdown of NAMPT in Ly6Chigh monocytes inhibited the progression of collagen-induced arthritis.25 However, the roles of NAMPT in SLE have not been studied yet.

In this study, we showed that CD4+ T cells from patients with LN exhibited enhanced NAD+ biosynthetic process. NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis contributed to enhanced glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration in CD4+ T cells from patients with LN or MRL/lpr mice. In a humanized lupus model, knockdown of NAMPT inhibited IFNγ expression in kidney-infiltrated CD4+ T cells and reduced inflammatory infiltrates into the kidney. MRL/lpr mice treated with NAMPT inhibitor FK866 showed fewer IFNγ-producing T cells and reduced inflammatory infiltrates, resulting in ameliorated kidney damage. In summary, NAMPT promoted translation efficiency of Ifng to drive the development of proinflammatory CD4+ T cells in LN.

Results

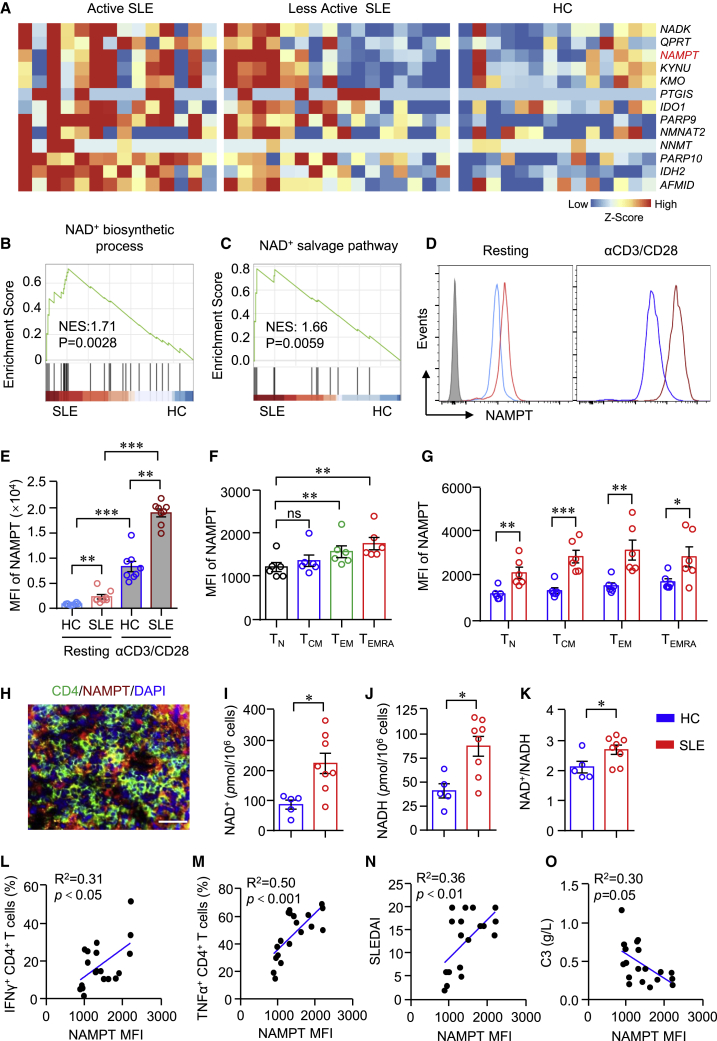

Enhanced NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis in CD4+ T cells from SLE

NAD+ plays an important role during immune response.26 Bulk RNA-seq data of CD4+ T cells from active SLE, less active SLE, and healthy controls (HCs) revealed that genes for NAD+ metabolism were notably increased in SLE (Figure 1A). Transcripts of NAD+ metabolic genes were higher in active SLE than that of less active SLE (Figure 1A). The result of gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showed that signaling pathways of the NAD+ biosynthetic process and NAD+ salvage pathway were significantly upregulated and enriched in CD4+ T cells from SLE (Figures 1B and 1C). NAMPT is the rate-limiting enzyme for NAD+ biosynthesis in the salvage pathway in mammals.19 We found that gene expression of NAMPT was among the top upregulated genes in CD4+ T cells from SLE, suggesting a role for NAMPT in CD4+ T cell activation in SLE. LN represents one of the most severe conditions of SLE. To further investigate whether NAMPT plays a role in LN, we measured NAMPT expression in CD4+ T cells from patients with LN or HCs by flow cytometry. Accordingly, NAMPT was significantly higher in CD4+ T cells from LN either at resting or activation states (Figures 1D and 1E). Notably, anti-CD3/CD28 beads stimulation increased NAMPT expression dramatically, and NAMPT expression was increased to a greater extent in CD4+ T cells from LN (Figures 1D and 1E). To further characterize NAMPT expression within CD4+ T cell subsets, we subjected CD4+ T cells to naive T (TN) cells (CD45RA+CCR7+), central memory T (TCM) cells (CD45RA−CCR7+), effector memory T (TEM) cells (CD45RA−CCR7−), and terminally differentiated T (TEMRA) cells (CD45RA+CCR7−). The data revealed that TN cells had the lowest expression of NAMPT. NAMPT expression in TEM and TEMRA cells was significantly higher than that in TN cells (Figure 1F). Consistently, NAMPT expression was higher in all of the CD4+ T cell subsets from patients with LN. It is worth noting that NAMPT was already increased in TN cells from LN (Figure 1G), suggesting a role of NAMPT in the early phase of disease development. Moreover, we found that kidney-infiltrated CD4+ T cells expressed a high level of NAMPT as measured by immunofluorescence (Figure 1H). Accordingly, NAD+ and NADH concentrations were higher in CD4+ T cells from patients with LN (Figures 1I–1K).

Figure 1.

Enhanced NAD+ metabolism in CD4+ T cells correlates with disease activities in patients with SLE

(A–C) Bulk RNA-seq data of CD4+ T cells from active systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), less active SLE, and healthy controls (HCs) were acquired from the GEO database (GEO: GSE97263) and adopted for further analysis. (A) Heatmap of gene expression for NAD+ metabolism from RNA-seq data. (B and C) Gene sets derived from Gene Ontology (GO) showing the enrichment scores of the NAD+ biosynthetic process and NAD+ salvage pathway through gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). (D and E) CD4+ T cells from patients with lupus nephritis (LN) or HCs were stimulated with or without anti-CD3/CD28 beads for 3 days. NAMPT expression was measured by flow cytometry. Data are from eight independent samples. (F) CD4+ T cells were divided into four subsets according to CD45RA and CCR7: CD45RA+CCR7+ naive T (TN) cells, CD45RA−CCR7+ central memory T (TCM) cells, CD45RA−CCR7− effector memory T (TEM) cells, and CD45RA+CCR7− terminally differentiated T (TEMRA) cells. NAMPT expression of all four subsets was measured by flow cytometry. Data are from six independent samples. (G) NAMPT expression levels of TN, TCM, TEM, and TEMRA cells from patients with LN or HCs were measured by flow cytometry. Data are from six independent samples. (H) Immunofluorescence image of CD4 (green) and NAMPT (red) staining in kidney sections from patients with LN. Scale bar: 40 μm. (I–K) NAD+/NADH in CD4+ T cells from patients with LN or HCs were measured using a WST-8-based colorimetric assay (HCs = 5, patients with LN = 8). (L and M) NAMPT, IFNγ, and TNF-α expression in CD4+ T cells from patients with LN were measured by flow cytometry. Correlations of NAMPT mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) with IFNγ and TNF-α (n = 19). (N and O) Correlation of NAMPT MFI with SLEIDA and serum concentration of C3 (n = 19). Data are mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA followed by adjustments for multiple comparisons in (E) and (F) and by Student’s t test in (G)–(K). Correlation was done by Pearson correlation coefficient.

To find out whether increased NAD+ metabolism is in association with enhanced effector functions of CD4+ T cells in LN, we measured NAMPT and cytokine expression in CD4+ T cells by flow cytometry, which showed that NAMPT expression was in close correlation with the production of IFNγ and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in LN CD4+ T cells (Figures 1L and 1M). Further, the level of NAMPT in CD4+ T cells was correlated with disease activities as determined by the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) and the concentration of complement component C3 in the serum (Figures 1N and 1O). These data linked NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis to CD4+ T cells activation in LN.

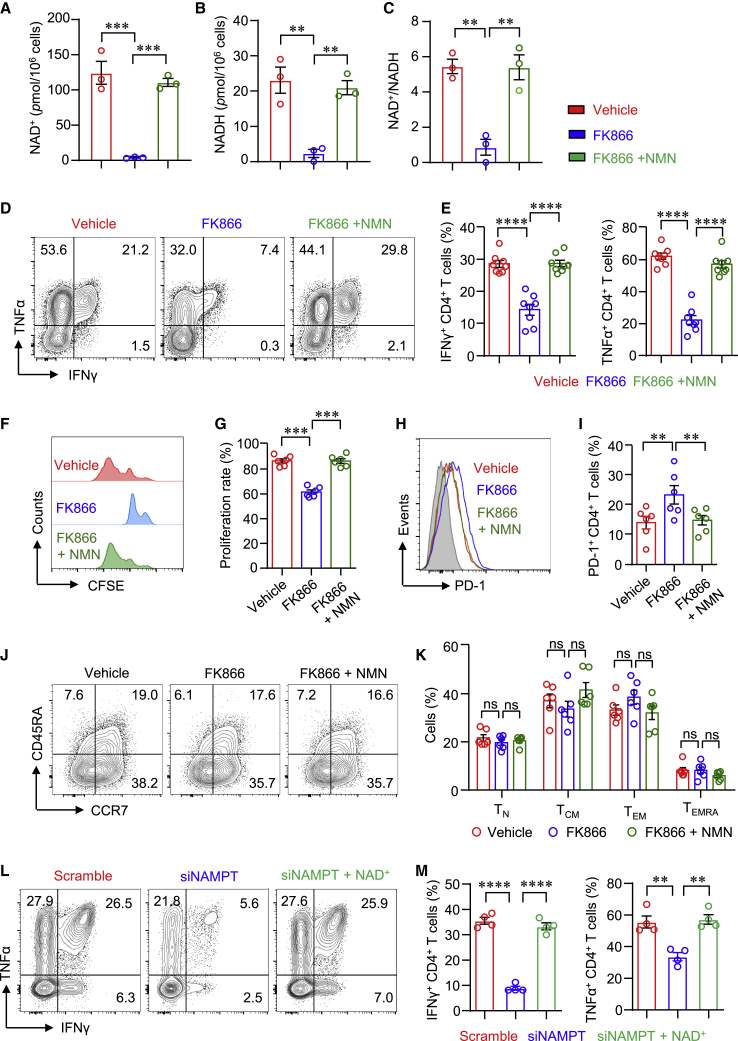

NAMPT-dependent effector functions of CD4+ T cells in LN

To further investigate the role of NAMPT in CD4+ T cells in LN, we treated LN CD4+ T cells with NAMPT inhibitor FK866 or vehicle. We first evaluated the importance of the NAMPT-controlled salvage pathway for NAD+ biosynthesis in CD4+ T cells. The data revealed that NAMPT inhibition almost depleted NAD+ production in human CD4+ T cells. The production of NADH was also dramatically reduced by FK866 (Figures 2A–2C), suggesting that NAD+ biosynthesis in human CD4+ T cells was mainly through a salvage pathway. In addition, the supplement of NMN completely reversed NAD+ production in CD4+ T cells (Figures 2A–2C). It is worth noting that NAMPT inhibition was not involved with cytotoxicity (Figure S1). Moreover, FK866 notably suppressed IFNγ and TNF-α production in LN CD4+ T cells (Figures 2D and 2E). Interestingly, FK866 failed to decrease IL-17A production in CD4+ T cells (Figure S2). The proliferation of LN CD4+ T cells was also inhibited by FK866 (Figures 2F and 2G). The supplement of NAD+ precursor NMN reversed cytokine production and cell proliferation completely (Figures 2D–2G), which was further confirmed using CD4+ T cells from HCs (Figure S3). The expression levels of PD-1, TIGIT, and Tim-3 in CD4+ T cells were increased by FK866, which was normalized by the supplement of NMN (Figures 2H, 2I, and S4). Phenotypically, the distribution of TN, TCM, TEM, and TEMRA CD4+ T cells was not affected by FK866 (Figures 2J and 2K). To further confirm the roles of NAMPT in LN CD4+ T cells, we knocked down NAMPT using NAMPT-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA). Similar results were found that knockdown of NAMPT reduced IFNγ and TNF-α expression in LN CD4+ T cells. Consistently, reduced IFNγ and TNF-α expression was reversed by the supplement of NAD+ completely (Figures 2L and 2M). These data indicate that NAMPT regulates IFNγ and TNF-α expression in CD4+ T cells through the synthesis of NAD+.

Figure 2.

NAMPT is required for CD4+ T cell effector function in LN

(A–K) LN CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads. FK866 or NMN was included in some experiments. (A–C) NAD+/NADH in LN CD4+ T cells was measured using a WST-8-based colorimetric assay after 3-day stimulation. Data are from three independent samples. (D and E) IFNγ and TNF-α expression in LN CD4+ T cells were measured by flow cytometry. Data are from eight independent samples. (F and G) LN CD4+ T cells were labeled with CFSE and stimulated for 3 days. T cell proliferation was measured by flow cytometry and representative histograms (n = 6). (H–K) PD-1, CD45RA, and CCR7 expression in LN CD4+ T cells were measured by flow cytometry (n = 6). Representative contour plots were shown. (L and M) Freshly purified CD4+ T cells were transfected with Scramble siRNA or NAMPT siRNA following stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 beads for 3 days. NAD+ was included in some experiments. IFNγ and TNF-α expression were measured by flow cytometry (n = 4). Data are mean ± SEM. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA followed by adjustments for multiple comparisons.

NAMPT has both intracellular and extracellular effects influencing several signaling pathways.27 The level of extracellular form of NAMPT, also called Visfatin, was found to be very low in the supernatant (<0.5 ng/mL) of CD4+ T cells even days after anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation (Figure S5A). In addition, Visfatin could not reverse the inhibition of FK866 over cytokine production in CD4+ T cells (Figures S5B–S5D), suggesting different roles and functions between intracellular and extracellular NAMPT for CD4+ T cells.

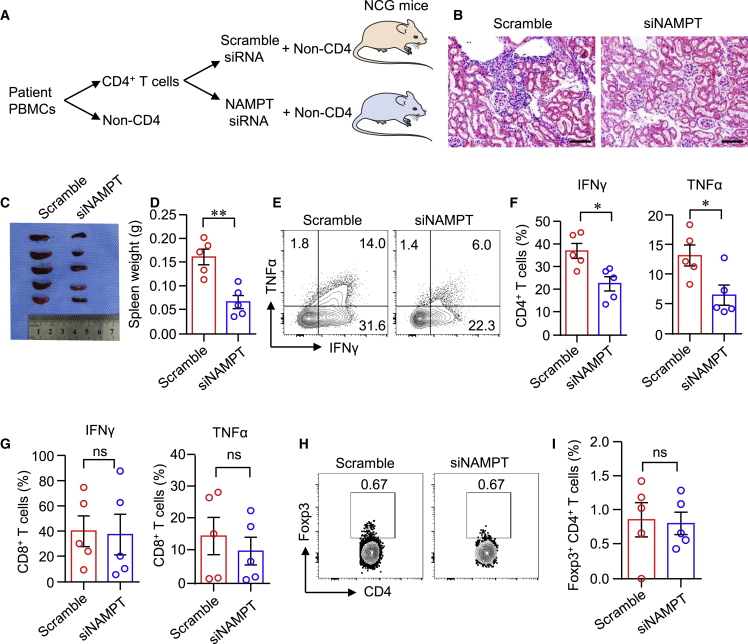

NAMPT promotes inflammatory CD4+ T cells

To mechanistically link NAMPT expression and functional behavior of kidney-infiltrated T cells in LN, we exploited a humanized mouse lupus model. In this model, CD4+ T cells sorted from LN PBMCs were treated with NAMPT or Scramble siRNA. NAMPT or Scramble siRNA-treated CD4+ T cells together with non-CD4+ PBMCs were co-transferred into NOD-Prkdcem26Cd52Il2rgem26Cd22/Gpt (NCG) mice (Figure 3A). Selective knockdown of NAMPT expression in LN CD4+ T cells impaired proinflammatory potential of CD4+ T cells. The density of kidney infiltrates was markedly reduced when NAMPT was knocked down (Figure 3B). Knockdown of NAMPT in LN CD4+ T cells affected T cell proliferationsince spleen weight was profoundly lower in mice that received NAMPT siRNA-treated CD4+ T cells (Figures 3C and 3D). Because the kidney inflammation and damage are closely correlated to the presence of IFNγ-producing T cells,10 we isolated single cells from the kidneys and quantified IFNγ production in kidney-infiltrated T cells by flow cytometry. Selective knockdown of NAMPT in CD4+ T cells markedly suppressed IFNγ and TNF-α expression in kidney-infiltrated CD4+ T cells (Figures 3E and 3F). The expression of IFNγ and TNF-α in kidney-infiltrated CD8+ T cells was not affected (Figure 3G). Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) play an important role in maintaining tissue inflammation.28 However, knockdown of NAMPT in LN CD4+ T cells did not affect Treg migration to the kidney. The percentages of Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells were similar between NAMPT siRNA and Scramble siRNA groups (Figures 3H and 3I). Taken together, NAMPT promotes IFNγ expression in CD4+ T cells, and knockdown of NAMPT reduces IFNγ-producing CD4+ T cell-induced tissue inflammation.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of NAMPT in CD4+ T cells reduces kidney inflammation

NOD-Prkdcem26Cd52Il2rgem26Cd22/Gpt (NCG) mice were immune reconstituted with LN PBMCs. Prior to the adoptive transfer, CD4+ T cells were sorted from PBMCs of patients with LN and treated with Scramble or NAMPT siRNA. (A) Schematic representation of experiment design. Humanized NCG mice were randomly injected with LN PBMCs containing CD4+ T cells treated with Scramble siRNA or NAMPT siRNA (n = 5). (B) Representative H&E images of the kidney. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C and D) Image and weight of spleen. (E and F) IFNγ and TNF-α expression by kidney-infiltrated CD4+ T cells were measured by flow cytometry. (G) IFNγ and TNF-α expression by kidney-infiltrated CD8+ T cells. (H and I) Percentage of Foxp3+CD4+ T cells in the kidney was measured by flow cytometry. Data are mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.05 by Student’s t test.

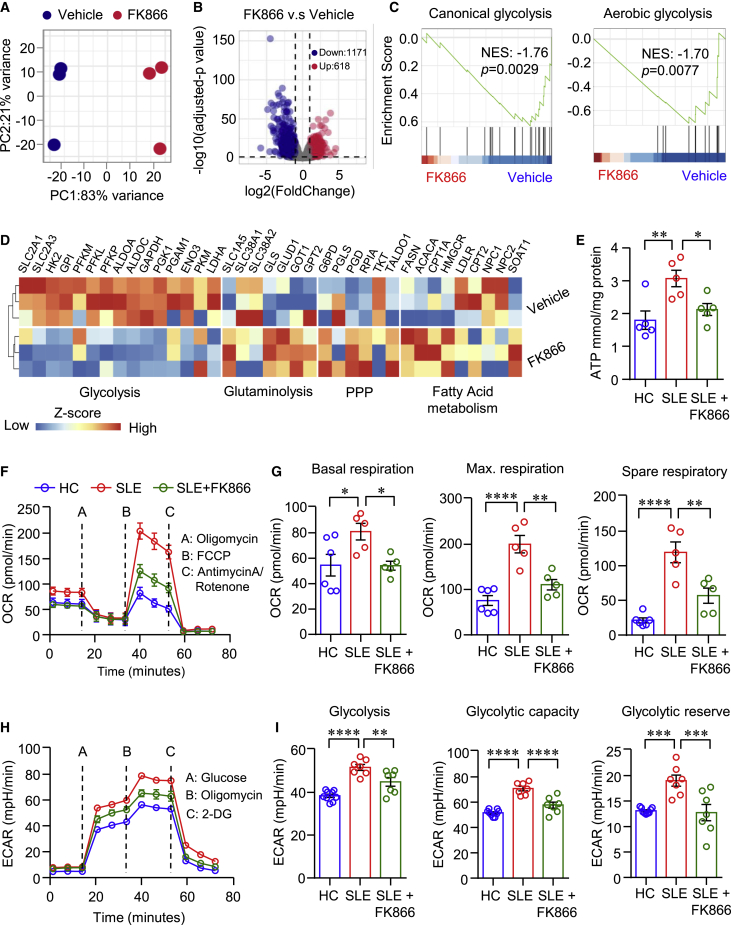

NAMPT reprograms metabolism of CD4+ T cells in LN

To explore the underlying mechanisms of NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis in regulating the effector functions of CD4+ T cells in LN, we performed RNA-seq to identify differential expression genes (DEGs) and significantly enriched signaling pathways in FK866-treated CD4+ T cells. The RNA-seq data revealed that FK866-treated CD4+ T cells were distinct fromvehicle-treated CD4+ T cells as illustrated by principal-component analysis (PCA) (Figure 4A), suggesting the fundamental DEGs profile between the two groups. As shown in the volcano plot, 1,171 genes were downregulated and 618 genes were upregulated in FK866-teated CD4+ T cells (Figure 4B). Further analysis by GSEA showed the signaling pathways of canonical glycolysis and aerobic glycolysis were significantly downregulated in FK866-treated CD4+ T cells (Figure 4C). Genes associated with glucose glycolysis were significantly decreased by FK866. In contrast, genes associated with glutaminolysis, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) were upregulated in FK866-treated CD4+ T cells (Figure 4D). Previous data have shown that aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration were enhanced in CD4+ T cells from SLE patients.17 Combined with our data above, we hypothesized that NAMPT should contribute to cellular metabolism disorder in LN CD4+ T cells. To test the hypothesis, we first measured ATP production in CD4+ T cells from LN or HC. We found that the level of ATP was significantly higher in LN CD4+ T cells, and NAMPT inhibition suppressed ATP production in patient CD4+ T cells to the level of healthy CD4+ T cells (Figure 4E). Further, seahorse assay was applied to measure extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in CD4+ T cells. We found that mitochondrial respiration and aerobic glycolysis were both significantly enhanced in CD4+ T cells from patients with LN, which were inhibited by FK866 (Figures 4F–4I), suggesting that NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis promotes cellular energy metabolism in CD4+ T cells from patients with LN.

Figure 4.

NAMPT reprograms CD4+ T cell metabolism in LN

(A–D) CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads in the presence of FK866 (8 nM) for 6 days. RNA-seq was performed to identify differential expression genes (DEGs, n = 3) and significantly enriched signaling pathways. (A) Unsupervised principal-component analysis (PCA) plot for gene expression regarding FK866- or vehicle-treated CD4+ T cells. (B and C) Volcano plot of DEGs and gene sets showing the enrichment scores of canonical glycolysis and aerobic glycolysis. (D) Heatmap of gene expression for glucose glycolysis, glutaminolysis, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and fatty acid metabolism. (E) ATP production in CD4+ T cells. (F–I) CD4+ T cells from patients with LN or HCs were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads for 3 days. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) (F and G) of basal respiration, maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity, and (H and I) extracellular acidification rates (ECAR) were measured by a Seahorse XF96 analyzer. Data are mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA followed by adjustments for multiple comparisons.

We further confirmed these data using CD4+ T cells from HCs. NAMPT inhibition by FK866 effectively reduced NAD+ biosynthesis in CD4+ T cells (Figures S6A–S6F). Further, the supplies of NMN to CD4+ T cells completely reversed energy production as suppressed by FK866 (Figures S6D–S6F). Interestingly, the inhibition of NAMPT or supplies of NMN did not affect glucose or lipid uptake by CD4+ T cells (Figures S6G–S6N). The supplement of pyruvate reversed inhibition of IFNγ production in CD4+ T cells as mediated by FK866 (Figures S6O and S6P), indicating that NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis is not required for glucose uptake but is essential for the breakdown and utilization of glucose.

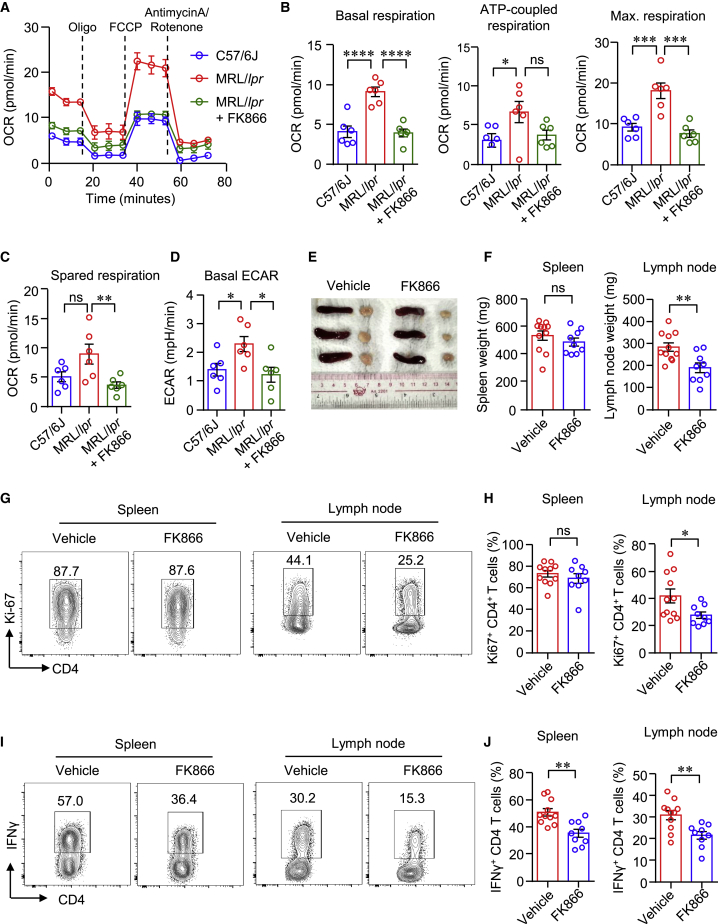

FK866 normalizes cellular metabolism and suppresses proinflammatory T cells in MRL/lpr lupus mice

To further explore whether NAMPT contributes to T cell metabolism and activation in LN, we treated MRL/lpr mice with FK866. Here, we observed that CD4+ T cells from MRL/lpr mice exhibited a higher level of cellular metabolism compared with that of normal mice (Figure 5). OCRs for mitochondrial respirations and ECAR for aerobic glycolysis were significantly higher in CD4+ T cells from lymph nodes of MRL/lpr mice as measured by seahorse assay (Figures 5A–5D). Notably, FK866 decreased mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis of CD4+ T cells in MRL/lpr mice (Figures 5A–5D). The size of lymph nodes was smaller in MRL/lpr mice treated with FK866. However, spleen weight was not affected by FK866 treatment (Figures 5E and 5F). The percentage of Ki-67+ CD4+ T cells in the spleen was not changed by FK866 either, whereas the percentage of Ki-67+ CD4+ T cells in the lymph nodes was decreased by FK866 significantly (Figures 5G and 5H), which is in accordance to the weights of spleen or lymph node. Interestingly, the percentage of IFNγ+ CD4+ T cells was decreased dramatically in both the spleen and the lymph node (Figures 5I and 5J). As for CD8+ T cells, the percentage of IFNγ+ CD8+ T cells in both the spleen and the lymph nodes was reduced significantly (Figures S7A–S7C). Consistent with CD4+ T cells, FK866 reduced the percentages of Ki-67+ CD8+ T cells in the lymph nodes, but not in the spleen (Figures S7D–S7F). It is worth noting that the percentages of Foxp3+ Tregs and CD103+ tissue-resident memory T cells were similar between vehicle and FK866 groups (Figures S7G–S7J).

Figure 5.

FK866 normalizes cellular metabolism and suppresses proinflammatory T cells in MRL/lpr lupus mice

(A–D) CD4+ T cells were isolated from kidney draining lymph nodes (DLNs) of MRL/lpr mice treated with FK866 or vehicle. Metabolic activities were measured using a Seahorse XF96 analyzer. OCR of basal respiration, respiration coupled to ATP production, maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity, and ECAR were summarized (n = 6). (E) Representative images of spleen and DLNs in mice treated with FK866 or vehicle. (F) Weights of spleen and DLNs in mice treated with FK866 or vehicle. (G and H) Ki-67 expression in CD4+ T cells from the spleen or DLNs was measured by flow cytometry. (I and J) IFNγ expression by CD4+ T cells in the spleen or DLNs was determined by flow cytometry. n = 11 in the vehicle group and n = 9 in the FK866 group. Data are mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA followed by adjustments for multiple comparisons in (B)–(D) and Student’s t test in (F), (H), and (J).

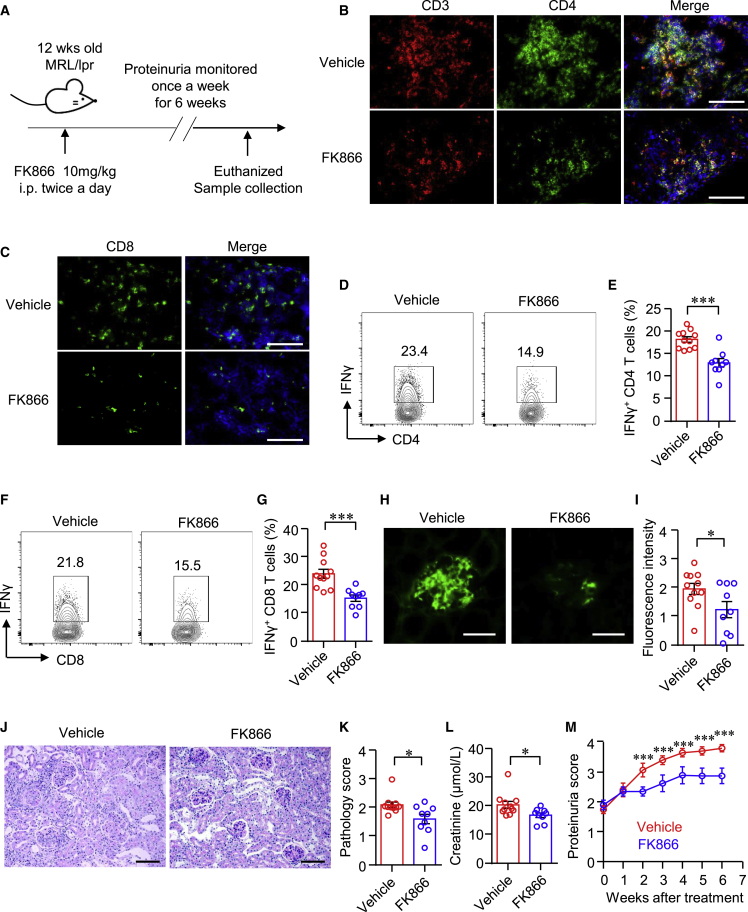

FK866 suppresses T cell response in the kidney microenvironment and ameliorates kidney damage

To further test the role of NAMPT in kidney-infiltrated T cells and the therapeutic effects of FK866 over the progression of nephritis in lupus-prone mice, we treated MRL/lpr mice with FK866 or vehicle for 6 weeks (Figure 6A). We found that FK866 profoundly decreased T cell infiltration into the kidney. The intensities of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the kidney were dramatically decreased as measured by immunofluorescence (Figures 6B and 6C). Consistently, IFNγ production by kidney-infiltrated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was decreased significantly as measured by flow cytometry (Figures 6D–6G). In addition, the deposition of immune complex in the glomeruli was reduced notably after the treatment as measured by immunofluorescence staining of IgG (Figures 6H and 6I). The pathological damage was ameliorated by FK866 (Figures 6J and 6K), which led to a decreased level of creatinine in the serum and reduced proteinuria (Figures 6L and 6M).

Figure 6.

FK866 suppresses kidney-infiltrated T cells and ameliorates kidney damage

(A) Scheme of the mouse experiment. Twelve-week-old MRL/lpr mice were treated with FK866 (10 mg/kg) or vehicle for 6 weeks. (B and C) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining showing CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells in the kidney of mice treated with FK866 or vehicle. Scale bar: 100 μm. (D–G) Single cells were isolated from the kidneys of mice treated with FK866 or vehicle. IFNγ expression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was measured by flow cytometry. Representative contour plots were shown. (H and I) Immunofluorescence staining of IgG in the glomeruli of mice treated with FK866 or vehicle. Representative images were shown. Scale bar: 50 μm. (J and K) Kidney sections were stained with PAS. Representative images were shown. Scale bar: 100 μm. (L) Level of creatinine in the serum of mice treated with FK866 or vehicle. (M) Proteinuria score of mice treated with FK866 or vehicle. Data are mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by Student’s t test.

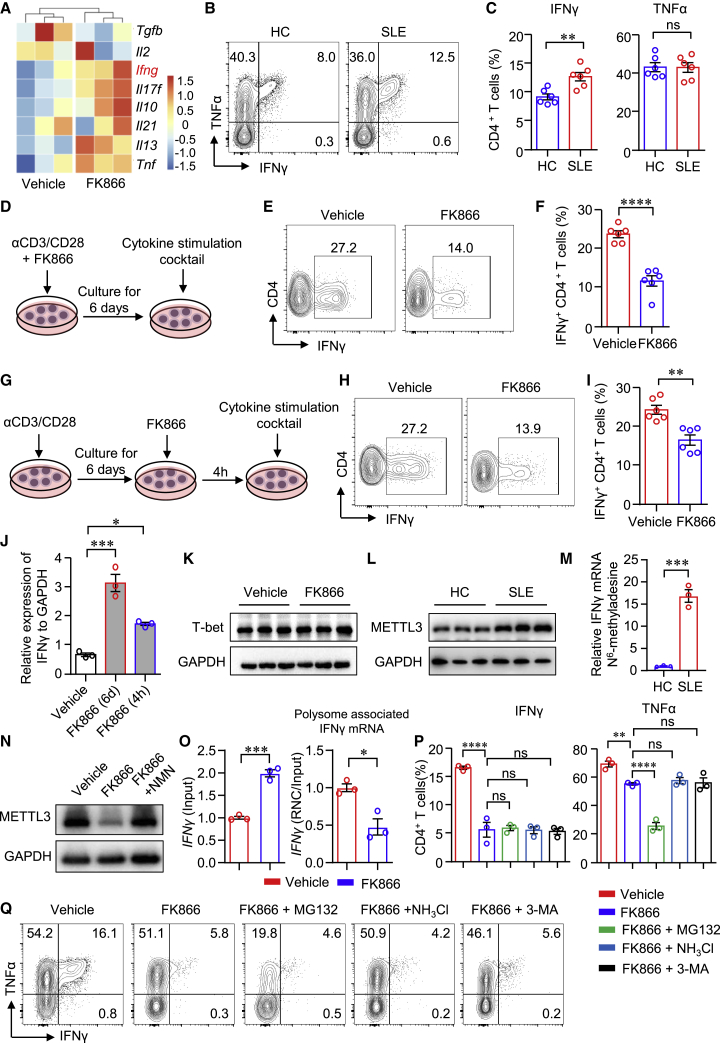

NAMPT controls translation efficiency of Ifng in CD4+ T cells

The bulk RNA-seq data revealed that transcripts of cytokines, including Ifng, Il17f, Il21, Il13, and Tnf, were increased in CD4+ T cells when treated with FK866, while Tfgb expression was decreased (Figure 7A). Ifng was among the top increased genes by FK866. IFNγ production was significantly increased in CD4+ T cells from patients with SLE, whereas TNF-α in CD4+ T cells were not different between SLE and HC (Figures 7B and 7C). IFNγ production by T cells is controlled at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels.29 From the in vitro and in vivo experiments, we found that NAMPT inhibition by FK866 clearly suppressed the protein expression of IFNγ. Thus, we speculated that NAMPT might control IFNγ expression at the posttranslational level. To test the hypothesis, we first performed two separate experiments in which CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads for 6 days and FK866 was added to the culture at the beginning or 4 h before sample collection (Figures 7D–7I). We found that IFNγ production was suppressed when FK866 was added at the beginning of cell culture (Figures 7D–7F). Surprisingly, IFNγ expression was decreased even when FK866 was added 4 h before cytokine measurement, although to a less extent when compared with that added from the beginning (Figures 7G–7I). In contrast, the mRNA expression of Ifng was increased by FK866 added either at the beginning or the last 4 h (Figure 7J), which was consistent with the RNA-seq data. Similar results were found in CD8+ T cells in which IFNγ expression was dramatically decreased when FK866 was added 4 h before cytokine measurement. Consistently, mRNA level of Ifng in CD8+ T cells was increased by FK866 (Figure S8). Albeit FK866 suppressed IFNγ expression but induced IL-4 expression under both Th1/Th2 differentiation conditions (Figures S9A and S9B), and the expression of T-bet, the master transcription factor for IFNγ expression,30 was not affected by FK866 (Figure 7K). Moreover, NAMPT expression in CD4+ T cells was not different when naive CD4+ T cells were cultured under different Th cell differentiation conditions (Figures S9C–S9G).

Figure 7.

NAMPT promotes Ifng translational efficiency in CD4+ T cells

(A) Heatmap of cytokine expression in FK866- or vehicle-treated CD4+ T cells from bulk RNA-seq analysis. (B and C) IFNγ and TNF-α production in CD4+ T cells from patients with LN or HCs was measured by flow cytometry (n = 6). (D–F) CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads in the presence or absence of FK866 (8 nM) for 6 days. IFNγ expression was measured by flow cytometry. Data are from six independent samples. (G–I) CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads for 6 days. IFNγ expression was measured by flow cytometry. Data are from six independent samples. (J) CD4+ T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads for 3 days. Ifng expression was measured by qPCR.

(K) T-bet expression measured by western blot and representative bands. (L–N) CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads in the presence or absence of FK866 for 3 days. (L) METTL3 expression of CD4+ T cells from patients with SLE or HCs was measured by western blot. Representative bands of six samples. (M) MeRIP-qPCR analysis of IFNγ mRNA in CD4+ T cells from patients with SLE or HCs. (N) METTL3 expression was measured by western blot. Representative bands were shown. (O) Ifng mRNA in total mRNA (input) or polysome-associated mRNA (RNC/input) was measured by real-time PCR. (P and Q) CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads for 3 days. IFNγ and TNF-α expression were measured by flow cytometry. Data are from three independent samples. Data are mean ± SEM. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by Student’s t test in (C), (F), (I), (M), and (O) and by one-way ANOVA followed by adjustments for multiple comparisons in (P).

mRNA methylation is actively involved in post-transcriptional gene regulation and controls protein synthesis in eukaryotes.31 METTL3, as an RNA methyltransferase, has been implicated in mRNA biogenesis, decay, and translation through N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification.32 We found that METTL3 expression was increased in patient CD4+ T cells (Figure 7L). Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing combined with real-time PCR (MeRIP-qPCR) was applied to quantify m6A modification level in Ifng mRNA. The data revealed that m6A modification in Ifng mRNA was increased in CD4+ T cells from SLE (Figure 7M). In addition, we found that METTL3 expression was significantly decreased in CD4+ T cells by FK866. The supplement of NMN reversed the inhibition of METTL3 expression in CD4+ T cells (Figure 7N), suggesting that NAMPT might regulate the translational efficiency by controlling the expression of METTL3. The important function of METTL3 is to promote mRNA translation.32,33 Ribosome nascent-chain complex-bound mRNA (RNC) analysis revealed that FK866 profoundly reduced polysome-associated Ifng mRNA (Figure 7O), suggesting that FK866 decreased translation efficiency of Ifng mRNA and thus lowered IFNγ production. Increased protein degradation could also lead to reduced protein level. To investigate whether NAMPT is involved with protein degradation, we applied proteasome inhibitor MG132, lysosome inhibitor NH4Cl, and autophagy inhibitor 3-Methyladenine (3-MA). The data revealed that none of these inhibitors was able to reverse the inhibition by FK866 (Figures 7P and 7Q). Together, NAMPT controls the translation efficiency of Ifng. The increased Ifng mRNA by FK866 might be because of the negative feedback from decreased protein expression of IFNγ.

Discussion

IFNγ-producing CD4+ T cells represent the major proinflammatory T cells in the blood and kidney infiltrates of LN.10 The expansion of IFNγ-producing CD4+ T cells and how their pathogenicity is regulated are not understood in LN. This study explored the underlying signals and identified NAMPT as a key regulator of metabolism in LN CD4+ T cells. Specifically, NAMPT promoted IFNγ production by CD4+ T cells through the biosynthesis of NAD+. Mechanistically, NAMPT promoted glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration to increase translation efficiency of Ifng mRNA in CD4+ T cells. Interruption of NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis suppressed IFNγ production by CD4+ T cells, leading to reduced renal inflammation and ameliorated kidney damage, pinpointing a key role of the NAD+ biosynthesis enzyme NAMPT in LN.

NAD+ exerts multiple well-described functions.34 We found that CD4+ T cells from patients with LN were “equipped” with greater potential of cellular metabolism for their increased ability to generate NAD+ in the cells, placing LN CD4+ T cells in the position that they are able to exert sustained and enhanced immune response. NAMPT inhibition dramatically reduced aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration in both healthy and LN CD4+ T cells, which could be reversed by supplement of NAD+ precursors. Our data demonstrate that NAMPT regulates IFNγ production through the synthesis of NAD+. In the glycolysis pathway, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) converting NAD+ into NADH is a key step to catalyze the simultaneous phosphorylation and oxidation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate to 1,3-biphosphoglycerate. In the mitochondria, mitochondrial membrane is impermeable to NAD+ and NADH; thus, mitochondrial NAD+ levels fluctuate independently.35 NAD/NADH-redox shuttles facilitate NADH flux to mitochondria.36 NAD+ could be produced from NADH by complex I in the electron transport chain37; thus, increased mitochondrial respiration could generate more NAD+. The amount of NAD+ should equal the amount of NADH in the cells in theory. The reality is that mitochondrial NAD/NADH ratios are maintained at 7–8,36 suggesting a more important role of NAD+ biosynthetic pathways in maintaining the mitochondrial NAD+ pool. NAMPT has been identified to locate in the mitochondria and mediate biosynthesis of NAD+ in mitochondria.38 NAMPT mediated NAD+ biosynthesis in the salvage pathway and NAD+ generated by complex I should coordinate to maintain the homeostasis of the NAD+ pool in the mitochondria.

Glycolysis is important for the differentiation of effector T cells. Th1 differentiation is driven by the upregulation of glycolysis to support the expression of the key transcriptional factor T-bet and IFNγ primarily.39 Aerobic glycolysis could also promote Th1 cell differentiation through an epigenetic mechanism that lactate dehydrogenase A maintains acetyl-coenzyme A to enhance histone acetylation and transcription of Ifng.40 IFNγ expression in T cells is controlled at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels.29 From the bulk RNA-seq data, we found that CD4+ T cell differentiation was not affected by NAMPT inhibition (data not shown). Our data confirmed that the expression of T-bet was not affected by NAMPT inhibition. Interestingly, the RNA-seq data revealed that the transcript of Ifng was increased when NAMPT was inhibited, suggesting that IFNγ production regulated by NAMPT might be at the posttranslational level. Previous data showed that the glycolytic enzyme GAPDH could bind to AU-rich elements within the 3′ UTR of Ifng mRNA and promotes the translation of Ifng mRNA.41 Our further data showed that FK866 suppressed the expression of METTL3, which could be reversed by the supplement of NAD+ precursor. These data suggest that NAMPT regulates METTL3 expression by the production of NAD+. It has been shown that METTL3 regulated translation of β-catenin.42 Regarding the important role of METTL3 in mRNA translation, NAMPT might regulate translation efficiency of Ifng through METTL3. In line with this, NAMPT inhibition significantly reduced polysome-associated Ifng mRNA. Moreover, inhibition of protein degradation could not reverse IFNγ production in CD4+ T cells, indicating that NAMPT is not involved with protein degradation. Together, NAMPT regulates IFNγ production in CD4+ T cells by enhancing translation efficiency of Ifng.

The mammalian family of sirtuins comprises NAD+-dependent deacetylases with a range of functions in energy metabolism, cell survival, transcription regulation, inflammation, and circadian rhythm.43 However, we did not observe the different expression of the sirtuins from the gene profile of CD4+ T cells from patients with LN (Figure S10), suggesting that NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis does not function through the sirtuins in LN CD4+ T cells. Mitochondria are central for cellular energy metabolism, including glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, and FAO.44 Distinct mitochondrial metabolism modes uncouple differentiation and function of CD4+ T cells.45 NAMPT could promote mitochondrial respiration by increasing NAD+ production in the mitochondria, which then support the translational machinery for Ifng.

In summary, we report here that NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis informs CD4+ T cells into a pathogenic program by promoting aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration. The data implicate NAMPT as a metabolic checkpoint in controlling cellular energy metabolism of IFNγ-producing CD4+ T cells in general. Mechanistically, NAMPT promotes translation efficiency of Ifng mRNA in CD4+ T cells. In this light, NAMPT could serve as the potential therapeutic target in the treatment of LN.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients who fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification of SLE with renal involvement were recruited from the First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University.46 Clinical disease activity was scored using SLEDAI.47 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the SLE patients are shown in Table S1. Age- and gender-matched HCs were enrolled. This study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Cell isolation

Human PBMCs were obtained by density gradient centrifugation using Lymphoprep (STEMCELL Technologies). Immunomagnetic negative selection Human CD4+ T cell Isolation Kit (STEMCELL Technologies) and immunomagnetic negative selection Human Naive CD4+ T cell Isolation Kit (STEMCELL Technologies) were used to purify total CD4+ T cells and naive CD4+ T cells from PBMCs, respectively. For adoptive transfer experiments, CD4+ and CD4− fractions of PBMCs were sorted by flow cytometry (FACSAria; BD Biosciences).

Cell culture

Purified human CD4+ T cells were activated with Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (beads/cell ratio 1:4; Gibco) in complete medium containing RPMI 1640, 10% heat-inactivated FBS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin for indicated time. FK866 (Selleck), NMN (Sigma-Aldrich), NAM riboside (NR; MedChemExpress), NAM (Sigma-Aldrich), NAD+ (Sigma-Aldrich), pyruvate (Agilent), recombinant human Visfatin (BioLegend), MG-132 (Selleck), NH4Cl (Selleck), and 3-MA (Selleck) were included at indicated concentrations in some of the experiments. Cytotoxicity of FK866 over CD4+ T cells was determined by Annexin V/7-AAD (BioLegend) and analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure S1).

To induce the differentiation of CD4+ T cells in vitro, we stimulated naive human CD4+ T cells with anti-CD3/CD28 beads in the presence of the following stimulating cocktails for 6 days: recombinant IL-12 (10 ng/mL; Sino Biological) and anti-IL-4 antibody (1 μg/mL) for Th1 polarization; IL-4 (40 ng/mL) for Th2 polarization; TGF-β (10 ng/mL) and IL-6 (50 ng/mL) for Th17 polarization; TGF-β (10 ng/mL) for Treg polarization; and IL-12 (5 ng/mL), IL-6 (20 ng/mL), IL-21 (20 ng/mL; PeproTech ), and TGF-β (1 ng/mL) for T follicular helper (Tfh) cells polarization.

Flow cytometry analysis

PBMCs isolated from SLE patients or HCs were stained with Pacific Blue™-anti-CD3 (1:100, clone #HIT3a; BioLegend) antibodies and allophycocyanin (APC)-anti-CD8 (1:100, clone #SK1; BioLegend), Pacific Blue™-anti-CCR7 (1:100, clone #G043H7; BioLegend), Alexa Fluor 700-anti-CD45RA (1:100, clone #HI100; BioLegend), BV605-anti-PD1 (1:100, clone #NAT 105; BioLegend), PE-anti-TIGIT (1:100, clone #A15153G; BioLegend), and APC-anti-Tim3 (1:100, clone #F38-2E2; Thermo Fisher) at 4°C for 30 min. Then cells were washed with PBS twice. For intracellular staining, cells were first fixed and permeabilized with Fixation/Permeabilization solution (BD Biosciences) and then washed with Perm/Wash Buffer (BD Biosciences). Cells were then incubated with primary antibody against NAMPT (1:500, clone #EPR21980; Abcam), followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488- conjugated Goat anti-Rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:500; Thermo Fisher). For intracellular cytokine measurement, cells were stimulated with PMA (50 ng/mL; Sigma-Aldrich), ionomycin (500 ng/mL; Sigma-Aldrich), and brefeldin A (5 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 h. Cells were then stained with PE/cy7-anti-IFNγ (1:50, clone #4S.B3; BioLegend), PE-anti-TNF-α (1:50, clone #MAb11; BioLegend), APC-anti-IL-17A (1:50, clone #TC11-18H10.1; BioLegend), and APC/cy7-anti-IL-4 (1:50, clone #MP4-25D2; BioLegend). In addition, cells were permeabilized with Foxp3 Staining Set (eBioscience) and then stained with APC-anti-Ki-67 (1:50, clone #16A8; BioLegend), PE-anti-Foxp3 (1:50, clone #MF-14; BioLegend), Alexa Fluor 488-GATA-3 (1:100, clone #16E10A23; BioLegend), and PE/Cyanine7-anti-Bcl-6 (1:100, clone #7D1; BioLegend) antibodies. In addition, cells were stained with primary antibody against RORγt (1:100, clone #AFKJS-9; eBioscience) followed by incubation with Dylight 488-conjugated Goat anti-Rat IgG secondary antibody (1:500; Abbkine). Samples were analyzed using a BD FACS LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences). FlowJo (Tree Star, USA) software was used for data analysis.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

For extracellular NAMPT measurement in the supernatant, purified human CD4+ T cells (1 × 105) were seeded in 96-well plates and activated with anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads. Cultured medium was collected after 24-h, 72-h, and 6-d stimulation. NAMPT concentration was measured using a commercially available ELISA kit for human NAMPT (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China).

NAD+ and NADH quantification

The NAD+ and NADH concentrations were determined using a NAD+/NADH Assay Kit with WST-8 (Beyotime, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The readings were measured using Thermo Scientific ™ Varioskan ™ LUX.

ATP quantification

Cellular ATP concentration of CD4+ T cells was determined using an ATP Assay Kit (Beyotime, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The readings were measured using Thermo Scientific™ Varioskan™ LUX.

Metabolic assays

ECAR and OCR were measured by an XF-96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). CD4+ T cells (2×105) were plated into each well of Seahorse XF96 cell culture microplates and incubated at 37°C for 1 h in the absence of CO2 in Seahorse XF RPMI Medium (Agilent Technologies) supplemented with 1 mM pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 20 mM glucose for mitochondrial stress test (or only 2 mM L-glutamine for glycolytic stress test). The Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress Test Kit and the Seahorse XF Cell Glycolysis Stress Test Kit were used to measure OCR and ECAR, respectively. For OCR, 1.5 μM oligomycin, 1.5 μM Trifluoromethoxy carbonylcyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP), and 1 μM rotenone/antimycin A were added during measurement. For ECAR, 10 mM glucose, 1 μM oligomycin, and 50 mM 2-Deoxyglucose (2-DG) were added during measurement. Results were collected with Wave software version 2.6.1 (Agilent Technologies).

T cell proliferation assay

Purified human T cells were stained with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Invitrogen) at 5 μM for 15 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped using pre-cold culture medium on ice for 5 min. Cells were then washed with PBS three times. CFSE-labeled cells were treated with the indicated treatment for 5 days, and the proliferation of cells was examined by flow cytometry.

Glucose uptake and lipid measurement

To measure glucose uptake, we incubated cells in glucose-free RPMI-1640 (Procell) containing 20 μM 2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino]-2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-NBDG) (Thermo Fisher) for 30 min at 37°C in a cell incubator. To measure lipid uptake, we incubated cells with complete medium containing 1 μM Bodipy 500 (Thermo Fisher) for 30 min at 37°C in a cell incubator. To measure lipid content in the cells, we added Bodipy 493 (1 μg/mL; Thermo Fisher) and incubated it for 30 min at 4°C. Data were acquired by flow cytometry.

Immunoblotting analysis

Cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA), including 1% Halt Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitor (Asegene). Proteins extracted from cells were separated by 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). After blockade with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST), membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies against NAMPT (1:1,000, clone #EPR21980; Abcam), T-bet (1:1,000, catalog [cat] #ab181400; Abcam), GAPDH (1:1,000, clone #D16H11; Cell Signaling Technology), and METTL3 (1:1,000, clone #D2I6O; Cell Signaling Technology). After washing three times with TBST, membranes were incubated with their corresponding secondary antibodies. The signals on the membranes were detected by a chemiluminescence analysis kit (Millipore).

T cell transfection

NAMPT siRNA or Scramble siRNA was synthesized by RiboBio (Guangzhou, China). Isolated human CD4+ T cells were transfected with NAMPT siRNA using a Nucleofector Kit (Lonza) according to the manufacturer’s protocols as described previously.48 Cells were left to rest and recover from the electroporation overnight. Cells were then activated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads.

qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using the TRIzol reagent and then subjected to reverse transcription using Evo M-MLV RT Premix (Accurate Biology, China). qPCR was performed using SYBR Green Chemistry (Accurate Biology). For amplification, cDNA was denatured at 95°C for 30 s, then amplified for 35 cycles at 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 30 s for annealing and elongation, respectively. Transcripts for individual genes were normalized to β-actin transcripts and presented as relative expression. Reactions were run on a qPCR system (Applied Biosystems). Primers used in this study were listed in Table S2.

MeRIP-qPCR

MeRIP-qPCR was performed as described previously.49 In brief, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol. A total of 20 μg RNA was incubated with α-m6A antibody (cat #202003; Synaptic Systems) or control IgG in immunoprecipitation buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40 [NP-40]) at 4°C for 2 h with gentle rotation. Then the RNA-antibody mixture was immunoprecipitated with pre-cleared Protein A + G Agarose (Beyotime, China) at 4°C for another 2 h with gentle rotation. After adequate washing, the bound RNAs were extracted using TRIzol and processed for qPCR analysis.

RNA-seq analysis

RNA was extracted from the isolated CD4+ T cells treated with either FK866 or vehicle as indicated. Libraries were sequenced on a BGIseq500 platform (BGI-Shenzhen, China) to generate single-end 50-base reads. Reads were aligned against Human reference genome (GRCh38) using HISAT2 (version 2.2.1) and were quantified using featurecounts (version 2.0.1). In order to improve the efficacy of the analytic process, we included only genes with more than 10 reads in all samples for further analysis. PCA and differential expression analyses were performed by using DESeq2 (version 1.28.1) R package.50 A PCA plot was drawn to illustrate variances between samples. Differential gene expression between different conditions was assessed via a moderated t test using the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method. The cutoff values were set as adjusted p < 0.05 and |log2 (fold change)| > 1. GSEA was applied by using clusterProfiler (version 4.1.0) R package to evaluate whether a specific gene signature was enriched in the FK866- or vehicle-treated group.51,52 Pathways were considered significantly enriched with p value corrected for multiple hypothesis testing using BH method less than 0.05. In addition, publicly available bulk RNA-seq data were used to compare NAD+ metabolism in CD4+ T cells of SLE verse HC (GEO: GSE97263). Accordingly, CD4+ T cells were isolated from peripheral blood of 14 SLE patients with active disease, 16 SLE patients with less active disease, and 14 HCs. Active disease was defined as an SLEDAI >6 and less active disease as SLEDAI <4. Differential expression analysis of CD4+ T cells between SLE and HC was explored by using DESeq2 as well. GSEA analysis was also conducted to assess enrichment of NAD+-associated signaling pathways. Core genes that contributed to the enrichment were all selected for the illustration of NAD+ metabolism in the heatmap. Data with gene read counts were analyzed and visualized using R (version 4.0.5) and RStudio (integrated development for R; RStudio). The raw sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in National Genomics Data Center,53,54 China National Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (GSA-Human: HRA002720) and are publicly accessible at: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human.

Immunofluorescence

Renal samples were obtained from patients with LN who underwent diagnostic renal biopsy. Acetone-fixed cryostat kidney sections (4 μm) were blocked with 5% BSA in PBS for 30 min and then incubated with primary antibodies against NAMPT (1:100, clone #EPR21980; Abcam) and CD4 (1:50, clone #34930; Abcam) at 4°C overnight. Sections were washed with PBS three times and subsequently incubated with Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500, cat #A32732; Thermo Fisher) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1,000; Thermo Fisher) at room temperature for 1 h. Sections were washed with PBS and counterstained with DAPI in mounting medium (Vector). Images were taken with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus).

RNC analysis

RNC analysis was performed as previously described.55 In brief, cells were treated with 100 mg/mL cycloheximide for 15 min at 37°C. Then cells were washed with cold PBS and incubated with 1 mL cell lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100 in ribosome buffer [RB buffer]: 20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.4], 15 mM MgCl2, 200 mM KCl, 100 mg/mL cycloheximide, and 2 mM dithiothreitol) on ice for 30 min. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 16,200 × g for 10 min at 4°C. 10% of the extraction was used as input control. The remaining extraction was layered onto 11 mL sucrose buffer (30% sucrose in RB buffer) and then subjected to ultra-centrifugation at 174,900 × g for 5 h at 4°C in an SW32 rotor (Beckman Coulter, USA) to collect the RNC pellets that contain the polysome fractions. Next, RNA samples were isolated from the input and RNC samples for real-time PCR.

Measurement of proteinuria and creatinine

Mouse urine samples were tested with proteinuria analysis strips (Albustix). Six different colors can be distinguished: negative (score for 0), trace (score for 0), 30–100 mg/dL (score for 1), 100–300 mg/dL (score for 2), 300–2,000 mg/dL (score for 3), and ≥2,000 mg/dL (score for 4) protein. Concentrations of serum creatinine were determined by a commercial autoanalyzer (Beckman Coulter).

Histology and immunofluorescence analysis of mouse kidney

Paraffin section (4 μm) of kidneys were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), and glomerular lesions were graded on a scale of 0–3 as previously described by two independent observers blinded to the study.56 Acetone-fixed cryostat sections (4 μm) of the kidneys were blocked with 5% BSA in PBS for 30 min and then incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Thermo Fisher). The fluorescence intensity was accessed on a scale of 0–3 and analyzed as described previously.56 For infiltrated T cell staining, kidney sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated anti-mouse CD3 (R&D Systems), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 (R&D Systems), and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse CD8 (R&D Systems) at 4°C overnight. Sections were washed with PBS and counterstained with DAPI in mounting medium (Vector). Images were taken with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus).

Mouse experiments

Female MRL/lpr mice were obtained from SLAC Laboratory Animal Company (Shanghai, China). Age- and gender-matched C57B6/L mice were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center at Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (Guangzhou, China). In addition, female NCG mice were purchased from GemPharmatech (Jiangsu, China). Mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free condition at the Experimental Animal Center of Sun Yat-sen University. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University, and all experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Animals. MRL/lpr mice were treated with either FK866 (10 mg/kg, twice a day) or an equal volume of vehicle intraperitoneally from 12 to 18 weeks of age. Urine was collected weekly for proteinuria measurement. At the end of treatment, mice were anesthetized and euthanized. Spleens, lymph nodes, and kidney samples were collected for single-cell analysis or tissue staining.

A humanized lupus mouse model PBMC-NCG chimera was generated as previously described.57 Female 8-week-old NCG mice were reconstituted with PBMCs (1 × 107/mouse) from patients with active LN. To inhibit NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis, we enriched CD4+ T cells by flow cytometry and transfected them with siRNA targeting NAMPT or control siRNA. NAMPT- or control siRNA-treated CD4+ T cells together with CD4+ T cell-depleted PBMCs were adoptively transferred into the NCG mice. On day 14, mice were euthanized, and kidneys were harvested for further measurements.

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0. The differences were assessed by t test or one-way ANOVA as appropriate. For correlation analysis, Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient was applied as appropriate. Two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071819 to H.Z.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82001712 to C.G.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81971519, 81671593, and 81471598), and National Key Research and Development Project (2017YFC0907602 to N.Y.).

Author contributions

M.L., C.G., and H.Z. conceived and designed the study. M.L., Y.L., C.G., B.C., M.Z., and J.L. recruited patients and analyzed clinical data. M.L., Y.L., C.G., B.C., and S.W. performed the experiments. M.L., Y.L., B.C., and H.Z. analyzed and interpreted the data. H.Z. and N.Y. wrote the manuscript with all authors providing feedback.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.09.013.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Kaul A., Gordon C., Crow M.K., Touma Z., Urowitz M.B., van Vollenhoven R., Ruiz-Irastorza G., Hughes G. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev. Dis. Primers. 2016;2:16039. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anders H.J., Saxena R., Zhao M.H., Parodis I., Salmon J.E., Mohan C. Lupus nephritis. Nat Rev. Dis. Primers. 2020;6:7. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu F., Haas M., Glassock R., Zhao M.H. Redefining lupus nephritis: clinical implications of pathophysiologic subtypes. Nat Rev. Nephrol. 2017;13:483–495. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suárez-Fueyo A., Bradley S.J., Klatzmann D., Tsokos G.C. T cells and autoimmune kidney disease. Nat Rev. Nephrol. 2017;13:329–343. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ivashkiv L.B. IFNgamma: signalling, epigenetics and roles in immunity, metabolism, disease and cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev. Immunol. 2018;18:545–558. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0029-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoenborn J.R., Wilson C.B. Regulation of interferon-gamma during innate and adaptive immune responses. Adv. Immunol. 2007;96:41–101. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(07)96002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luckheeram R.V., Zhou R., Verma A.D., Xia B. CD4(+)T cells: differentiation and functions. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012;2012:925135. doi: 10.1155/2012/925135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baccala R., Kono D.H., Theofilopoulos A.N. Interferons as pathogenic effectors in autoimmunity. Immunol. Rev. 2005;204:9–26. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crow M.K. Interferon-alpha: a new target for therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus? Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2396–2401. doi: 10.1002/art.11226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fava A., Buyon J., Mohan C., Zhang T., Belmont H.M., Izmirly P., Clancy R., Trujillo J.M., Fine D., Zhang Y., et al. Integrated urine proteomics and renal single-cell genomics identify an IFN-gamma response gradient in lupus nephritis. JCI Insight. 2020;5 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.138345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wandl U.B., Nagel-Hiemke M., May D., Kreuzfelder E., Kloke O., Kranzhoff M., Seeber S., Niederle N. Lupus-like autoimmune disease induced by interferon therapy for myeloproliferative disorders. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1992;65:70–74. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(92)90250-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarting A., Wada T., Kinoshita K., Tesch G., Kelley V.R. IFN-gamma receptor signaling is essential for the initiation, acceleration, and destruction of autoimmune kidney disease in MRL-Fas(lpr) mice. J. Immunol. 1998;161:494–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang N., Perl A. Metabolism as a target for modulation in autoimmune diseases. Trends Immunol. 2018;39:562–576. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacIver N.J., Michalek R.D., Rathmell J.C. Metabolic regulation of T lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013;31:259–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y., Shen Y., Jin K., Wen Z., Cao W., Wu B., Wen R., Tian L., Berry G.J., Goronzy J.J., Weyand C.M. The DNA repair nuclease MRE11A functions as a mitochondrial protector and prevents T cell pyroptosis and tissue inflammation. Cell Metab. 2019;30:477–492.e476. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angiari S., Runtsch M.C., Sutton C.E., Palsson-McDermott E.M., Kelly B., Rana N., Kane H., Papadopoulou G., Pearce E.L., Mills K.H.G., O'Neill L.A.J. Pharmacological activation of pyruvate kinase M2 inhibits CD4(+) T cell pathogenicity and suppresses autoimmunity. Cell Metab. 2020;31:391–405.e398. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin Y., Choi S.C., Xu Z., Perry D.J., Seay H., Croker B.P., Sobel E.S., Brusko T.M., Morel L. Normalization of CD4+ T cell metabolism reverses lupus. Sci Transl. Med. 2015;7:274ra18. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa0835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Covarrubias A.J., Perrone R., Grozio A., Verdin E. NAD(+) metabolism and its roles in cellular processes during ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021;22:119–141. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00313-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kincaid J.W., Berger N.A. NAD metabolism in aging and cancer. Exp Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2020;245:1594–1614. doi: 10.1177/1535370220929287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garten A., Schuster S., Penke M., Gorski T., de Giorgis T., Kiess W. Physiological and pathophysiological roles of NAMPT and NAD metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015;11:535–546. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Travelli C., Consonni F.M., Sangaletti S., Storto M., Morlacchi S., Grolla A.A., Galli U., Tron G.C., Portararo P., Rimassa L., et al. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase acts as a metabolic gate for mobilization of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2019;79:1938–1951. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv H., Lv G., Chen C., Zong Q., Jiang G., Ye D., Cui X., He Y., Xiang W., Han Q., et al. NAD(+) metabolism maintains inducible PD-L1 expression to drive tumor immune evasion. Cell Metab. 2021;33:110–127.e115. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cameron A.M., Castoldi A., Sanin D.E., Flachsmann L.J., Field C.S., Puleston D.J., Kyle R.L., Patterson A.E., Hässler F., Buescher J.M., et al. Inflammatory macrophage dependence on NAD(+) salvage is a consequence of reactive oxygen species-mediated DNA damage. Nat. Immunol. 2019;20:420–432. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0336-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerner R.R., Klepsch V., Macheiner S., Arnhard K., Adolph T.E., Grander C., Wieser V., Pfister A., Moser P., Hermann-Kleiter N., et al. NAD metabolism fuels human and mouse intestinal inflammation. Gut. 2018;67:1813–1823. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Présumey J., Courties G., Louis-Plence P., Escriou V., Scherman D., Pers Y.M., Yssel H., Pène J., Kyburz D., Gay S., et al. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase/visfatin expression by inflammatory monocytes mediates arthritis pathogenesis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013;72:1717–1724. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navarro M.N., Gomez de Las Heras M.M., Mittelbrunn M. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide metabolism in the immune response, autoimmunity and inflammageing. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021;179:1839–1856. doi: 10.1111/bph.15477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dahl T.B., Holm S., Aukrust P., Halvorsen B. Visfatin/NAMPT: a multifaceted molecule with diverse roles in physiology and pathophysiology. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2012;32:229–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071811-150746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esensten J.H., Muller Y.D., Bluestone J.A., Tang Q. Regulatory T-cell therapy for autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases: the next frontier. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018;142:1710–1718. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fenimore J., H A.Y. Regulation of IFN-gamma expression. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016;941:1–19. doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-0921-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lugo-Villarino G., Maldonado-Lopez R., Possemato R., Penaranda C., Glimcher L.H. T-bet is required for optimal production of IFN-gamma and antigen-specific T cell activation by dendritic cells. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:7749–7754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332767100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao B.S., Roundtree I.A., He C. Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:31–42. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin S., Choe J., Du P., Triboulet R., Gregory R.I. The m(6)A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes translation in human cancer cells. Mol Cel. 2016;62:335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choe J., Lin S., Zhang W., Liu Q., Wang L., Ramirez-Moya J., Du P., Kim W., Tang S., Sliz P., et al. mRNA circularization by METTL3-eIF3h enhances translation and promotes oncogenesis. Nature. 2018;561:556–560. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0538-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie N., Zhang L., Gao W., Huang C., Huber P.E., Zhou X., Li C., Shen G., Zou B. NAD(+) metabolism: pathophysiologic mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2020;5:227. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00311-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cambronne X.A., Stewart M.L., Kim D., Jones-Brunette A.M., Morgan R.K., Farrens D.L., Cohen M.S., Goodman R.H. Biosensor reveals multiple sources for mitochondrial NAD(+) Science. 2016;352:1474–1477. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stein L.R., Imai S.i. The dynamic regulation of NAD metabolism in mitochondria. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;23:420–428. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Navas L.E., Carnero A. NAD(+) metabolism, stemness, the immune response, and cancer. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2021;6:2. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00354-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang H., Yang T., Baur J.A., Perez E., Matsui T., Carmona J.J., Lamming D.W., Souza-Pinto N.C., Bohr V.A., Rosenzweig A., et al. Nutrient-sensitive mitochondrial NAD+ levels dictate cell survival. Cell. 2007;130:1095–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michalek R.D., Gerriets V.A., Jacobs S.R., Macintyre A.N., MacIver N.J., Mason E.F., Sullivan S.A., Nichols A.G., Rathmell J.C. Cutting edge: distinct glycolytic and lipid oxidative metabolic programs are essential for effector and regulatory CD4+ T cell subsets. J. Immunol. 2011;186:3299–3303. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng M., Yin N., Chhangawala S., Xu K., Leslie C.S., Li M.O. Aerobic glycolysis promotes T helper 1 cell differentiation through an epigenetic mechanism. Science. 2016;354:481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang C.H., Curtis J.D., Maggi L.B., Jr., Faubert B., Villarino A.V., O'Sullivan D., Huang S.C., van der Windt G.J., Blagih J., Qiu J., et al. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 2013;153:1239–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J., Xie G., Tian Y., Li W., Wu Y., Chen F., Lin Y., Lin X., Wing-Ngor Au S., Cao J., et al. RNA m(6)A methylation regulates dissemination of cancer cells by modulating expression and membrane localization of beta-catenin. Mol. Ther. 2022;30:1578–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haigis M.C., Sinclair D.A. Mammalian sirtuins: biological insights and disease relevance. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2010;5:253–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spinelli J.B., Haigis M.C. The multifaceted contributions of mitochondria to cellular metabolism. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018;20:745–754. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bailis W., Shyer J.A., Zhao J., Canaveras J.C.G., Al Khazal F.J., Qu R., Steach H.R., Bielecki P., Khan O., Jackson R., et al. Author Correction: distinct modes of mitochondrial metabolism uncouple T cell differentiation and function. Nature. 2019;573:E2. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1490-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hochberg M.C. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gladman D.D., Ibañez D., Urowitz M.B. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J. Rheumatol. 2002;29:288–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu B., Qiu J., Zhao T.V., Wang Y., Maeda T., Goronzy I.N., Akiyama M., Ohtsuki S., Jin K., Tian L., et al. Succinyl-CoA ligase deficiency in pro-inflammatory and tissue-invasive T cells. Cell Metab. 2020;32:967–980.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Y., Cai J., Yang X., Wang K., Sun K., Yang Z., Zhang L., Yang L., Gu C., Huang X., et al. Dysregulated m6A modification promotes lipogenesis and development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Ther. 2022;30:2342–2353. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Love M.I., Anders S., Kim V., Huber W. RNA-Seq workflow: gene-level exploratory analysis and differential expression. F1000Res. 2015;4:1070. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7035.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B.L., Gillette M.A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S.L., Golub T.R., Lander E.S., Mesirov J.P. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu T., Hu E., Xu S., Chen M., Guo P., Dai Z., Feng T., Zhou L., Tang W., Zhan L., et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation. 2021;2:100141. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen T., Chen X., Zhang S., Zhu J., Tang B., Wang A., Dong L., Zhang Z., Yu C., Sun Y., et al. The genome sequence archive family: toward explosive data growth and diverse data types. Dev. Reprod. Biol. 2021;19:578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2021.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Database resources of the national genomics data center, China national center for bioinformation in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab951. D27–D38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang T., Cui Y., Jin J., Guo J., Wang G., Yin X., He Q.Y., Zhang G. Translating mRNAs strongly correlate to proteins in a multivariate manner and their translation ratios are phenotype specific. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:4743–4754. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao J., Wang H., Dai C., Wang H., Zhang H., Huang Y., Wang S., Gaskin F., Yang N., Fu S.M. P2X7 blockade attenuates murine lupus nephritis by inhibiting activation of the NLRP3/ASC/caspase 1 pathway. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:3176–3185. doi: 10.1002/art.38174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wen Z., Xu L., Xu W., Xiong S. Retinoic acid receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor gammat licenses the differentiation and function of a unique subset of follicular helper T cells in response to immunogenic self-DNA in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:1489–1500. doi: 10.1002/art.41687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.