Abstract

Background:

A frequently encountered problem in laparoscopic surgery is an impaired visual field. The Novel Intracavitary Laparoscopic Cleaning Device (NILCD) is designed to adequately clean a laparoscopic lens quickly and efficiently without requiring removal from the surgical cavity. Animal and cadaver studies showed good efficacy and a short learning curve. This study aims to describe the efficacy and initial human experience with the device during laparoscopic operations.

Methods:

Since 2020, NILCD was used in 167 cases with surgeons at 12 different institutions in Texas, California, and Massachusetts. The rate of scope removal in each case was examined. Following each trial, users were asked to rank the NILCD on ease of set up, insertion, adjustment, and cleaning efficacy. A survey was then used to evaluate surgeon satisfaction.

Results:

The NILCD was tested in a variety of cases, including colorectal, gynecological, general, pediatric, hepatobiliary, thoracic, bariatric and foregut surgery. NILCD usage eliminated the need for scope removal in 90.14% of debris events, with only 97 removals in 984 events. Eighty-six percent of users reported that the NILCD improved their visual field. When asked to rate specific qualities of the device using a 5-point Likert scale, surgeons gave an average score of 4.56 for ease of setup, 4.10 for ease of insertion, and 4.12 for ease of adjusting and cleaning efficacy.

Conclusion:

In an initial analysis of 167 cases, the NILCD proved to be an effective and convenient method of cleaning the laparoscopic lens in-vivo. It was associated with good surgeon satisfaction.

Keywords: General surgery, Innovation, Laparoscopic surgery

INTRODUCTION

Dr Kelling, a German surgeon and inventor, is thought to be the founding father of laparoscopic surgery. He initially invented his “coelioscopy” as a method of evaluating his “Lufttamponade”, a technique involving air insufflation to high levels into the abdominal cavity to tamponade gastrointestinal bleeding.1 It was not until the 1980s that laparoscopic surgery gained more traction in general surgery after its use for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.2 In the past 10 years the field of laparoscopic surgery has developed rapidly, with more and more procedures safely being performed laparoscopically resulting in decreased length of stay and improved patient outcomes.3

However, in this time of rapid development, laparoscopic instruments have not seen major changes, the current system of a long camera with a light source is not dramatically different than the initial scope developed by Kelling. The introduction of robotic surgery has decreased some of the focus on laparoscopic surgery.4 Many significant problems still have not been addressed in laparoscopic surgery including impaired visualization.

An impaired visual field is a frequently encountered problem in laparoscopic surgery. Observational studies have found that only 56% of laparoscopic operating room time is spent with a clear visual field, with issues such as condensation, tissue debris, and blood causing decreased lens clarity.5 Many different strategies have been developed to clear the camera lens; however, these methods are time consuming and not always effective. Antifogging, heating, and cleaning devices have all been advertised as being effective in rapid and effective lens cleaning, yet data proving their effectiveness is lacking.6

In addition to being frustrating to surgeons and a detriment to patient safety, a problem with impaired visual fields is the time it takes to clean the lens. Studies have shown that up to 7% of the time during laparoscopic operations is spent cleaning the lens. The current gold standard solution requires 20 to 60 seconds to remove, clean, and replace the dirty lens; with this interruption occurring 3 – 10 times on average for each laparoscopic case.5 As longer operative times are related to worse patient outcomes and increased cost, it is important to address this preventable cause of increased operative time.7

The Novel Intracavitary Laparoscopic Cleaning Device (NILCD) was designed to address the problem of an impaired visual field and wasted time in laparoscopic cases to clean the lens (Figure 1). It is essentially a windshield wiper designed to adequately clean a laparoscopic lens quickly and efficiently without requiring removal from the surgical cavity. Animal and cadaver studies had been performed which showed good efficacy and a short learning curve for operating surgeons. This study aims to describe the efficacy and initial human experience with the device during actual laparoscopic operations.

Figure 1.

The novel intracorporeal cleaning device.

METHODS

After receiving Food and Drug Administration approval in 2020, the NILCD was used in 167 cases at different institutions across the country in a variety of surgical subspecialties including colorectal, gynecological, general, pediatric, hepatobiliary, thoracic, bariatric, and foregut surgery. Before each operation, the surgeon was educated on the method of NILCD usage. The number of debris events as well as their characteristics were recorded. Debris events were described as an impaired visual field due to condensation, fog, blood, tissue, or fat on the lens. The effectiveness of NILCD in removal of the debris was examined, and the rate of scope removal was documented. Following each trial, users were asked to rank the NILCD on ease of set up, insertion, adjustment, and cleaning efficacy. A survey was then used to evaluate surgeon satisfaction.

The NILCD was designed to fit on existing 5-mm laparoscopes. Each scrub tech was trained on the set up of the NILCD before the case, which involves slipping the NILCD over the scope and securing it in place by wrapping the elastic band around the scope and securing the loop over the existing knob on the NILCD (Figure 1). After one training session, all scrub techs were able to successfully complete the set-up. In the process of this study, it was discovered that the distance between the lens was not identical in each of the scopes. A spacer device was then introduced, which allowed the scrub tech to measure the distance and place a spacer to create an exact contact between the lens and the NILCD each time (Figure 2). The changes in satisfaction scores before and after the introduction of the spacer were examined. The Likert scores were tabulated and an average was calculated. The number of scope removals mitigated with the use of the NILCD was also documented.

Figure 2.

The placement of spacers specific to each laparoscope.

RESULTS

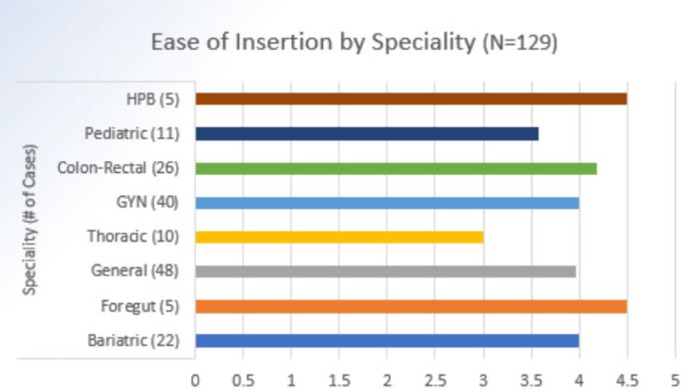

The NILCD was used in a total of 167 operations in a variety of specialties. There were a total number of 984 debris events. NILCD usage eliminated the need for scope removal in 90.14% of debris events, with NILCD being effective in clearing the lens intraoperatively 887 times (Table 1). In individual cases examined, the wiper was actuated on average one to three times depending on the substance being cleaned from the scope (Table 1). In 97% of cases, the scope was removed three or fewer times with over 65% of cases requiring no scope removal (Table 2). A majority of users (86%) reported that using NILCD improved their visual field. When asked to rate specific qualities of the device using a 5-point Likert scale, surgeons gave an average score of 4.56 for ease of setup, 4.10 for ease of insertion, and 4.12 for ease of adjusting and cleaning efficacy (Table 3). The initial cases were performed without the use of a spacer, and the spacer was introduced in the following 88 cases. Surgeon satisfaction was found to increase greatly with the introduction of the spacer (Table 4). The variety of surgical subspecialties were compared, and hepatobiliary and foregut cases were found to have the highest rankings on the Likert scale (Table 5).

Table 1.

Number of Debris Events and Scope Removals per Case

| Events per surgery/case | Condensation/Fog | Blood | Tissue/Smudge | Total Debris Event | Total Scope Removal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 5.9 | 0.6 |

| St. Dev | 1.7 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 6.1 | 1.2 |

| Max | 8 | 44 | 30 | 51 | 10 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sample Size | 167 | 167 | 167 | 167 | 167 |

Table 2.

Number of Scope Removals per Case

| # of Scope Removals for Lens Cleaning | # of Cases | % of Total Cases |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 110 | 65.09 |

| ≤ 1 | 145 | 85.80 |

| ≤ 2 | 158 | 93.49 |

| ≤ 3 | 164 | 97.04 |

| > 3 | 3 | 1.78 |

Table 3.

Surgeon Satisfaction on the Likert Scale

| Ease of Insertion |

Ease of Operation |

Ease of Use |

Ease of Setup |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Cases 1 – 35 (n = 10) | 3.2727 | 0.6467 | 2.8182 | 0.7508 | 2.7273 | 0.9045 | 3.3636 | 1.3618 |

| Cases without spacers (36 – 79) (n = 54) | 3.9091 | 0.6404 | 3.8182 | 1.1054 | 3.4545 | 1.1300 | 3.9318 | 0.6611 |

| Spacer cases (80 – 167) (n = 88) | 4.1098 | 0.6668 | 4.1220 | 0.8072 | 3.9024 | 0.8694 | 4.5610 | 0.5235 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Table 4.

Comparison of Surgeon Satisfaction Before and After Introduction of Spacers

Table 5.

Comparison of Surgeon Satisfaction Based on Specialty

DISCUSSION

This study sought to examine the experience of surgeons with the NILCD while performing a variety of laparoscopic operations. We hypothesized that there would be a short learning curve and high surgeon satisfaction, in addition to improvement in visualization during surgeries. Our results showed that the use of the NILCD mitigated scope removal and was effective in clearing the lens in most settings. Unlike more complicated devices, the learning curve for mastering the use of the NILCD is relatively short. Prolonged use of the NILCD leads to more familiarity and an increase in satisfaction. Even for first time users, the NICLD decreased operative time by mitigating the need for scope removal, and with increased familiarity this time saved in the operating room will become more significant.

The development of the NILCD has been dynamic, with changes made as deemed necessary. The addition of spacers that allow for more consistent cleaning was one of these changes, which has led to increased surgeon satisfaction. As the use of NILCD becomes more widespread, new information will be gathered about aspects of the device that can be improved and changed.

One limitation of our study is the inability to follow surgeons on a longitudinal basis. Surgeon satisfaction was evaluated after a one-time experience with the NILCD. Future research can be done to follow each surgeon after multiple uses to better understand the learning curve. At the time of writing this paper, a small sample size is also a limitation; however, as the use of the NILCD becomes more widespread the number of cases is increasing dramatically and further studies will have a larger sample size. Advantages of our study include the wide variety of specialties and operations that the NILCD was trialed in. Limitations of the NILCD itself are that they are currently only compatible with 5-mm scopes, further work is being done on creating different sized NILCDs. Some of the specific challenges with using the NILCD is remembering to return the wiper to the center of the scope before removal so that it does not catch on the trocar; however, no instances of the wiper falling off were reported in any of the cases.

The addition of an NILCD to an operation will add minimal cost with a significant improvement in quality of care. The NILCD adds a total cost of $97.50, which is easily made up for by decreasing the time spent cleaning the scope and therefore decreasing overall operating time, which will come with substantial cost decrease. Avoiding the need to remove the scope multiple times will allow for a smoother operation with fewer distractions and reduced anesthesia time for the patient.

CONCLUSION

In an initial analysis of 167 cases, the NILCD proved to be an effective and convenient method of cleaning the laparoscopic lens in-vivo across a variety of surgical disciplines and was associated with good surgeon satisfaction especially after the introduction of spacers. Intracorporeal lens cleaning could significantly impact the field of laparoscopic surgery by decreasing operative time and interruptions to clean the lens - consequently decreasing operative complications and cost.

Footnotes

Disclosure: C.I. is employed by Clear Cam, J.U., J.A., C.R. have equity in ClearCam.

Funding sources: none.

Acknowledgements: none.

Conflict of interests:

Informed consent: Dr. Simin Golestani declares that written informed consent was obtained from the patient/s for publication of this study/report and any accompanying images.

Contributor Information

Simin Golestani, Department of Surgery and Perioperative Care, University of Texas at Austin Dell Seton Medical Center, Austin, TX..

Charles Hill, Department of Surgery and Perioperative Care, University of Texas at Austin Dell Seton Medical Center, Austin, TX..

Jawad Ali, Department of Surgery and Perioperative Care, Ascension Seton Medical Center Hayes, Kyle, TX..

Christopher Idelson, Clear Cam, Austin, TX..

Christopher Rylander, Clear Cam, Austin, TX..

John Uecker, Department of Surgery and Perioperative Care, University of Texas at Austin Dell Seton Medical Center, Austin, TX.; Clear Cam, Austin, TX.

References:

- 1.Litynski GS. Laparoscopy–the early attempts: spotlighting Georg Kelling and Hans Christian Jacobaeus. JSLS. 1997;1(1):83–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vecchio R, MacFayden BV, Palazzo F. History of laparoscopic surgery. Panminerva Med. 2000;42(1):87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spaner SJ, Warnock GL. A brief history of endoscopy, laparoscopy, and laparoscopic surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1997;7(6):369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheetz KH, Claflin J, Dimick JB. Trends in the adoption of robotic surgery for common surgical procedures. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1918911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yong N, Grange P, Eldred-Evans D. Impact of laparoscopic lens contamination in operating theaters: a study on the frequency and duration of lens contamination and commonly utilized techniques to maintain clear vision. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2016;26(4):286–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lawrentschuk N, Fleshner NE, Bolton DM. Laparoscopic lens fogging: a review of etiology and methods to maintain a clear visual field. J Endourol. 2010;24(6):905–913. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Cheng H, Clymer J, Chen B, et al. Prolonged operative duration is associated with complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Surg Res. 2018;229:134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]