Abstract

Background

Observed sex differences in COVID-19 outcomes suggest that men are more likely to experience critical illness and mortality. Thrombosis is common in severe COVID-19, and D-dimer is a significant marker for COVID-19 severity and mortality. It is unclear whether D-dimer levels differ between men and women, and the effect of D-dimer levels on disease outcomes remains under investigation.

Objectives

We aimed to evaluate the sex difference in the D-dimer level among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and the effect of sex and D-dimer level on disease outcomes.

Methods

We meta-analyzed articles reporting D-dimer levels in men and women hospitalized for COVID-19, until October 2021, using random effects. Primary outcomes were mortality, critical illness, and thrombotic complications.

Results

In total, 11,682 patients from 10 studies were analyzed (N = 5606 men (55.7%), N = 5176 women (44.3%)). Men had significantly higher odds of experiencing mortality (odds ratios (OR) = 1.41, 95% CI: [1.25, 1.59], P ≤ .001, I2 = 0%) and critical illness (OR = 1.76, 95% CI: [1.43, 2.18], P ≤ .001, I2 = 61%). The mean D-dimer level was not significantly different between men and women (MD = 0.08, 95% CI: [−0.23, 0.40], P = .61, I2 = 52%). In the subgroup analysis, men had significantly higher odds of experiencing critical illness compared with women in both the “higher” (P = .006) and “lower” (P = .001) D-dimer subgroups.

Conclusion

Men have significantly increased odds of experiencing poor COVID-19 outcomes compared with women. No sex difference was found in the D-dimer level between men and women with COVID-19. The diversity in D-dimer reporting impacts data interpretation and requires further attention.

Keywords: COVID-19, critical illness, D-dimer, sex differences, thrombosis

Essentials

-

•

Marked elevation in D-dimer levels is reported to be associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes.

-

•

Hospitalized men have greater odds of poor COVID-19 outcomes compared with women.

-

•

No difference in the D-dimer level was found between hospitalized men and women with COVID-19.

-

•

Inconsistencies among D-dimer assays and unit reporting hinder the validity of D-dimer studies.

1. Introduction

COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2, infected >400 million people worldwide. Although many cases of COVID-19 infection are asymptomatic or mild, a large subset of patients experience severe clinical manifestations and require life-supporting treatment [1,2]. Men are reported to be more likely to experience severe COVID-19 illness and mortality than women [[3], [4], [5], [6]]. However, it is unknown whether the sex difference in COVID-19 outcomes is linked to the biological differences.

Efforts to identify a reliable prognostic indicator of COVID-19 severity have led to interest in elevated D-dimer level as being the most promising [7]. Unlike other fibrin degradation products, D-dimer is only generated when there is plasmin-mediated degradation of stabilized, cross-linked fibrin [8]. Thus, D-dimer serves as an evidence of potential thrombotic activity in patients. COVID-19 viral-mediated cell death can induce severe inflammation that leads to aberrant induction of procoagulant factors, increases fibrinogen, and promotes fibrin clot formation and systemic intravascular coagulation [9]. Elevated D-dimer appears to be the most common finding among the thromboembolic panel of markers in patients with COVID-19 [10]. Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, are frequently reported in cases of severe COVID-19 [9]. This risk contributed to the widespread use of D-dimer testing during the pandemic. One study reported that healthy women have higher D-dimer levels than healthy men, but the difference is not clinically significant [11], whereas another study found no significant difference in the mean D-dimer levels between healthy male and female subgroups [12].

We hypothesized that sex differences in the D-dimer levels may help evaluate sex differences in COVID-19 outcomes. The aims of this study were to (1) investigate the effect of sex difference on experiencing poor COVID-19 outcomes (thrombosis, critical illness, and mortality) and (2) investigate the sex difference in the D-dimer level and the relationship to COVID-19 outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources and selection criteria

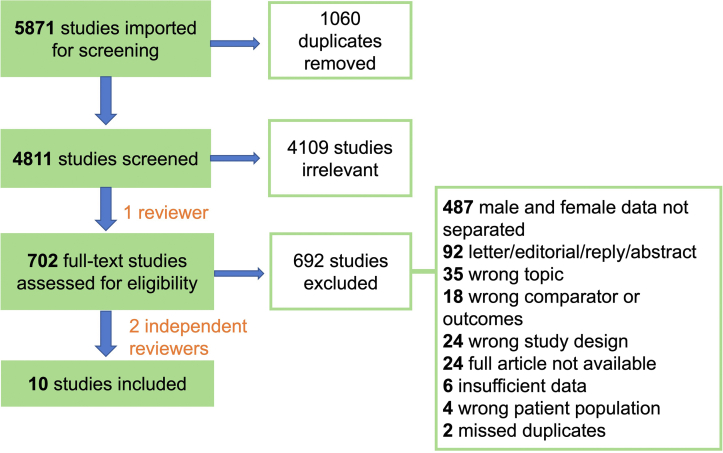

We conducted a systematic literature search in EMBASE and PubMed until October 1, 2021, to identify all studies evaluating the D-dimer levels in adult men and women hospitalized for COVID-19 and reporting on their mortality, critical illness, and thrombotic complications. Our search strategy was as follows: (COVID-19 OR Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) AND (D dimer) AND (sex difference OR gender OR clinical outcome OR hospitalization OR intensive care unit OR mortality). The retrieved articles were imported to and manually screened in Covidence [13]—a web-based software platform that streamlines the production of systematic reviews. Our selection process, according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [14] framework is shown in Figure 1. One investigator (O.S.) performed the title and abstract screening for the selection of potentially relevant articles. Two reviewers (O.S. and Y.T.) independently performed the full-text screening for the selection of included articles. All selections were decided by consensus. After eliminating duplicate records, 4811 articles were retrieved, 4801 articles were excluded because they did not meet all the inclusion criteria, and 10 articles were included in the meta-analysis. We included studies with full-text prospective, retrospective, or registry-based design. Only studies examining the adult patients admitted to the hospital for a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 were considered. Studies reporting any of the outcomes such as death at any time interval, critical illness, and thrombotic events were included. Only studies directly comparing male and female populations (with laboratory values reported separately and D-dimer reported as a concentration) were included. We excluded letters to the editor, individual case reports or case series (<10 participants), studies on special populations, including pregnancy or children, and studies with a secondary disease focus.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the systematic literature search.

A single reviewer (O.S.) independently assessed the quality of the included studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [15], which considers patient selection, study comparability, and three components of outcomes assessment to evaluate the quality of the original work [15]. An assigned score ≥6 stars indicates high quality.

2.2. Data extraction and statistical analysis

A single reviewer (O.S.) independently extracted the study and patient variables from the included articles, presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. A random-effects meta-analysis was performed using Cochrane RevMan5 [26]. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs were calculated to describe the relationship between sex and poor COVID-19 outcomes (critical illness and mortality) between men and women. A P < .05 was considered statistically significant. The level of heterogeneity was interpreted as I2 <30% = low, >50% = moderate, and >75% = high [27]. The mean differences (MDs) and 95% CIs were calculated between male and female D-dimer concentrations. When studies reported D-dimer as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), the corresponding mean (SD) were estimated with the formula of Wan et al. [28]. When D-dimer assay calibration units (fibrinogen equivalent units [FEU] or D-dimer units [DDU]) were not reported, the corresponding author was contacted. If the data could not be retrieved, the study was omitted from D-dimer meta-analysis. The subgroup analysis was performed to calculate the difference in odds of critical illness between men and women at lower versus higher D-dimer levels. Male and female D-dimer concentrations were averaged in each study, then ordered from highest to lowest. The “lower” D-dimer subgroup contained the studies from the lower half of the data set, whereas the “higher” D-dimer subgroup contained studies from the upper half of the dataset.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 10 included studies.

| Study | Country | Study period | Study design | Sample size (n) | Men (n) | Mean/median age in years (y), M/F | NOS (stars) | Reported D-dimer units | Reported outcomes | D-dimer units retrieved through author correspondence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancochea et al. [16] | Spain | January 1, 2020, to May 1, 2020 | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 2531 | 1449 | 63.3/61.7 | 6 | Mean (SD) and median (IQR); mg/L | Critical illness | DDU |

| Holler et al. [17] | Denmark | January 1, 2020, to July 8, 2020 | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 2431 | 1315 | 67.3/67.3 | 7 | Median (IQR); U/L | Critical illness, mortality | No response |

| J. Liu et al. [18] | China | December 29, 2019, to February 28, 2020 | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 1190 | 635 | 56.3/57.7 | 6 | Mean (95% CI); ug/mL | Mortality, thrombotic complications | No response |

| Marik et al. [19] | USA | January 2020 to June 2020 | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 701 | 370 | 62/61 | 8 | Median (IQR); ng/L | Critical illness, mortality | Unable to obtain |

| Minhas et al. [20] | USA | March 1, 2020, to July 4, 2020 | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 2060 | 1088 | 60.3/60.7 | 7 | Median (IQR); mg/dL | Critical illness, mortality, thrombotic complications | FEU |

| Giacomelli et al. [21] | Italy | February 21, 2020, to May 31, 2020 | Prospective cohort, multicenter | 520 | 349 | 60.7/61.0 | 8 | Median (IQR); ug/L | Critical illness, mortality | DDU |

| Jin et al. [22] | China | January 17, 2020, to March 20, 2020 | Retrospective case-control, multicenter | 681 | 362 | 47.2/47.2 | 9 | Median (IQR); ug/L | Critical illness | DDU |

| D. Liu et al. [23] | China | January 20, 2020, to April 1, 2020 | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 459 | 248 | 63.0/64.4 | 8 | Median (IQR); mg/L | Mortality | DDU |

| Quaresima et al. [24] | Italy | March 23, 2020, to December 29, 2020 | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 1000 | 633 | 63.2/65.0 | 7 | Median (range); ng/ml; FEU | Critical illness, mortality, thrombotic complications | NA |

| Nizami et al. [25] | UAE | Not provided | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 109 | 57 | 44.5/37.9 | 5 | Mean (SD); ug/mL; FEU | Critical illness | NA |

NOS, quality assessment; 6 on the 9-star scale indicates a high-quality study.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 11,682 hospitalized patients with COVID-19: demographics, comorbidities, and outcomes.

| Demographics | |

|---|---|

| Total patients (n) | 11,682 |

| Male age in years (y), mean SD | 61.6 17.0 |

| Female age in years (y), mean SD | 61.4 18.6 |

| Male n (%) | 6506 (55.7) |

| Non-White/White patient ratio, male | 1030/1021 |

| Non-White/White patient ratio, female | 888/757 |

|

Comorbidities | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies (n) | Male n (%) | Female n (%) | |

| Respiratory disease | 6 | 523 (8) | 344 (6.6) |

| Hypertension | 7 | 2246 (34.5) | 1787 (34.5) |

| Diabetes | 8 | 1276 (19.6) | 986 (19) |

| Cardiac disease | 7 | 1644 (25.2) | 1164 (22.5) |

| Kidney disease | 6 | 350 (5.4) | 196 (3.8) |

| Liver disease | 5 | 135 (2) | 77 (1.5) |

| Cancer | 6 | 484 (7.4) | 329 (6.4) |

|

In-hospital COVID-19 outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies (n) | Male n (%) | Female n (%) | |

| Critical illness | 8 | 1722 (26.5) | 1282 (22.0) |

| Mortality | 7 | 852 (13.1) | 508 (9.8) |

| Thrombotic complications | 3 | 110 | 67 |

2.3. Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed to determine whether the study quality influenced the OR of poor COVID-19 outcomes. Studies with <6 stars according to the NOS were omitted from the pooled meta-analysis. We also determined whether outlier D-dimer values influenced the mean difference in D-dimer level by omitting them from the pooled meta-analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the included studies

The characteristics of the 10 included studies are outlined in Table 1. All were retrospective, multi-, or single-center cohort studies except for 1 prospective cohort and 1 retrospective case-control study. The D-dimer level was reported as mean (SD), mean (95% CI), median (IQR), and median (range) by 2, 1, 6, and 1 studies, respectively. All selected studies were of high quality ( 6 stars) except for 1 of moderate quality (5 stars) by the Newcastle–Ottawa criteria.

3.2. Patient characteristics from the included studies

Data from 11,682 patients were used to analyze critical illness, mortality, and D-dimer levels in adult patients hospitalized for COVID-19. In total, 6506 (55.7%) were men and 5176 (44.3%) were women. The mean ages for men and women were 61.6 ± 17.0 years and 61.4 (18.6) years, respectively. The most commonly reported comorbidities were respiratory disease, hypertension, diabetes, cardiac disease, kidney disease, liver disease, and cancer. The prevalence of each comorbidity was similar between sexes, but they tended to be slightly (2%–3%) more common in men. Smoking and drinking statuses were generally not reported, sex-stratified ethnicity was only reported by 3 studies, and vaccination status was not reported. These data are summarized in Table 2.

3.3. Sex differences in COVID-19 outcomes and D-dimer

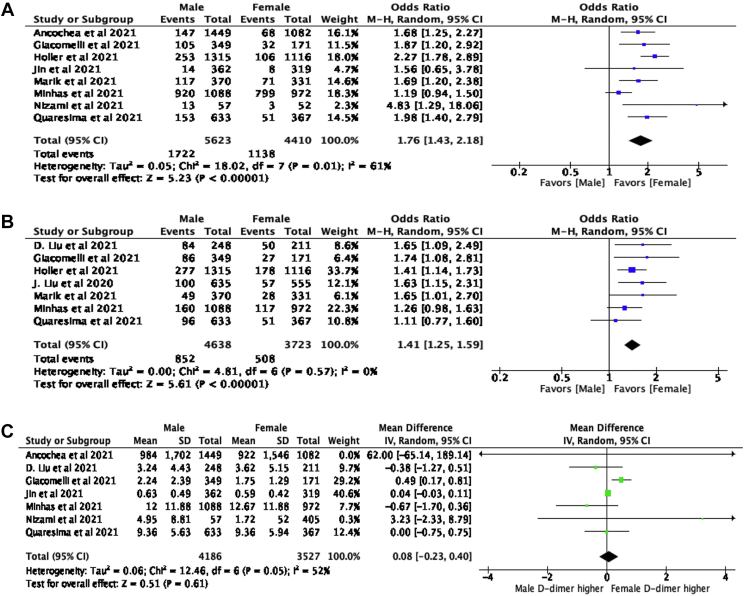

Critical illness, reported as a primary COVID-19 outcome by 8 studies, was experienced by 1722 (26.5%) men and 1282 (22.0%) women. A significantly higher number of men experienced critical illness (OR = 1.76, 95% CI: [1.43, 2.18], P ≤ .001, I2 = 61%) compared with women. Mortality, reported as a primary outcome by 7 studies, was experienced by 852 men (13.1%) and 508 women (9.8%). A significantly higher number of men experienced mortality (OR = 1.41, 95% CI: [1.25, 1.59], P ≤ .001, I2 = 0%). Thrombotic complications were only reported as a COVID-19 outcome by 3 studies, which is insufficient to describe the incidence rates. The absolute numbers of thrombotic events reported in men and women were 110 and 67, respectively. D-dimer concentration was not significantly different between men and women (MD = 0.08, 95% CI: [−0.23, 0.40], P = .61, I2 = 52%). Forest plots showing the odds of critical illness and mortality, and the mean difference in D-dimer is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of (A) difference in odds of critical illness between males and females, (B) difference in odds of mortality between males and females, (C) mean difference in male and female D-dimer concentration (mg/L, FEU). ‘Events’ is the number of males/females that experienced mortality/critical illness. ‘Total’ is the total number of males/females in the study. Blue/green squares represent the OR or MD. Horizontal lines represent the 95% CI of each study. Black diamond represents the overall OR or MD and 95% CI.

3.4. Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

Subgroup analysis, stratifying studies into “high” and “low” D-dimer, showed that a significantly higher number of men experienced critical illness compared with women in both the “higher” (OR = 1.55, 95% CI: [1.14, 2.11], P = .006, I2 = 71%) and “lower” (OR = 1.97, 95% CI: [1.31, 2.95], P = .001, I2 = 4%) D-dimer groups; there was no significant subgroup difference (P = .36). In the sensitivity analysis, removing the study of moderate quality (<6 stars on NOS) yielded (Z = 5.15, P ≤ .001) and (Z = 0.46, P = .65) in the test of OR for mortality and MD in the D-dimer level, respectively. Removal of the study with outlier D-dimer values yielded (Z = 0.50, P = .62) in the test for MD in D-dimer levels. The magnitude and the direction of the effect sizes were not substantially different from the pooled results in Figure 2.

4. Discussion

The aim of the current study was to investigate the sex differences in the outcomes of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and to determine whether sex differences in the D-dimer levels could help explain the differences in COVID-19 outcomes. We found that men were significantly more likely to experience poor outcomes, such as critical illness and mortality, compared with women, which is consistent with the previous published reports [4,29]. However, the D-dimer levels did not differ between men and women. These results may, to some degree, resemble observations from the studies on recurrent VTE. D-dimer levels are associated with a higher risk of VTE recurrence, and men have a higher recurrence risk than women [30,31]. However, some studies reported that the D-dimer level was not predictive of VTE recurrence in men [32,33]. The mean age of men (61.6 17.0) and women (61.4 18.6) was similar, and both sexes had comparable incidence of various comorbidities (Table 2). Subgroup analysis, stratifying studies into “high” and “low” D-dimer values, indicated that the D-dimer level did not affect the sex difference in COVID-19 outcomes.

The number of included studies was too small to statistically power a meta-regression [34]. Most available COVID-19 studies fail to compare male and female D-dimer levels. Many of the studies that do stratify D-dimer level by sex fail to report D-dimer values in a manner that allows for meta-analysis. Thus, meta-analyses with a larger sample size and the use of meta-regression are needed to confirm our results that D-dimer levels do not differ between men and women hospitalized for COVID-19.

5. Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the variation in D-dimer reporting among the 10 included studies may impact our data interpretation. Many of the studies reported D-dimer as a median, from which the mean (SD) had to be estimated to perform meta-analysis. The estimation model [28] may not accurately reflect the true mean of the patient data. In addition, there was inconsistency in unit reporting: mg/L, U/L, μg/mL, μg/L, ng/mL, and mg/dL were all reported at least once. As a result, unrecognized data reporting errors can occur. For instance, through author correspondence, we discovered that one included study published D-dimer data in mg/L when it was measured in g/L. Furthermore, 8 of the 10 studies failed to report D-dimer unit calibration (FEU or DDU), and only 5 of those 8 studies provided the outstanding units on correspondence. Some included studies also used the FEU cutoff value (>500 g/L or >0.5 mg/L) [35] to identify the patients with elevated D-dimer, despite using an assay calibrated in DDU. FEU express the mass of D-dimer as the equivalent mass of fibrinogen that would be needed to produce the D-dimer in the sample [36]. One FEU has approximately two times the mass of one DDU: 1 mg/L FEU = 0.5 mg/L DDU [36].

6. Future Diretions and Significfance

Future work is required to bring awareness to the diversity in D-dimer assay methods and to promote standardization in D-dimer reporting. This will enable data combination from various studies and allow for meta-regression to be performed. The use of patient level data in sex-based D-dimer meta-analyses is also needed. More than 30 different D-dimer assays are commercially available, and they differ widely in their manufacturing and operating characteristics [35,36]. The D-dimer cutoff level is specific to each assay, and the study results with one assay cannot be reliably extrapolated to other assays [37]. We believe that applying the recommendations recently published by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis [37] would be a simple first step toward improving D-dimer testing and reporting.

Non-sex-stratified studies continue to find that elevated D-dimer level is an independent risk factor for COVID-19 severity [[28], [29], [30]]. Accurate reporting and interpretation of D-dimer tests is important for effective triage of newly admitted patients, particularly during COVID-19 surges that strain healthcare systems. Early prediction of prognosis may identify patients who require enhanced observation and aid advanced care planning and treatment decisions.

7. Conclusion

Men are more likely to experience poor COVID-19 outcomes than women. Further investigation is required to determine whether D-dimer is associated with sex-based differences in outcomes, and this depends on the improvement of D-dimer reporting.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Author contributions

M.O., M.E., and Y.D. conceived and designed the study. O.S. and Y.T. acquired the data. O.S. performed the statistical analysis. O.S. and M.E. interpreted the data. O.S. drafted the manuscript. M.O. and M.E. critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

Relationship Disclosure

There are no competing interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Funding information The authors received no funding for this study.

Handling Editor: Dr Suzanne Cannegieter

References

- 1.Bohn M.K., Hall A., Sepiashvili L., Jung B., Steele S., Adeli K. Pathophysiology of COVID-19: mechanisms underlying disease severity and progression. Physiology. 2020;35:288–301. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00019.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peltan I.D., Caldwell E., Admon A.J., Attia E.F., Gundel S.J., Mathews K.S., et al. Characteristics and outcomes of US patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Am J Crit Care. 2022;31:146–157. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2022549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popadic V., Klasnja S., Milic N., Rajovic N., Aleksic A., Milenkovic M., et al. Predictors of mortality in critically Ill COVID-19 patients demanding high oxygen flow: a thin line between inflammation, cytokine storm, and coagulopathy. Oxidative Med Cell Longevity. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/6648199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alharthy A., Aletreby W., Faqihi F., Balhamar A., Alaklobi F., Alanezi K., et al. Clinical characteristics and predictors of 28-day mortality in 352 critically ill patients with COVID-19: A retrospective study. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;11:98–108. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.200928.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ñamendys-Silva S.A., Alvarado-Ávila P.E., Domínguez-Cherit G., Rivero-Sigarroa E., Sánchez-Hurtado L.A., Gutiérrez-Villaseñor A., et al. Outcomes of patients with COVID-19 in the intensive care unit in Mexico: a multicenter observational study. Heart Lung. 2021;50:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tay M.Z., Poh C.M., Rénia L., MacAry P.A., Ng L.F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:363–374. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao Y., Cao J., Wang Q., Shi Q., Liu K., Luo Z., et al. D-dimer as a biomarker for disease severity and mortality in COVID-19 patients: a case control study. J Intensive Care. 2020;8:49. doi: 10.1186/s40560-020-00466-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weitz J.I., Fredenburgh J.C., Eikelboom J.W. A test in context: D-dimer. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2411–2420. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semeraro N., Colucci M. The prothrombotic state associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: pathophysiological aspects. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2021;13 doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2021.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iba T., Levy J.H., Levi M., Connors J.M., Thachil J. Coagulopathy of coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:1358–1364. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leger R., Bryant S. c., Edwards K., Tange J.I., Fylling K.A., Warad D.M., et al. An age distribution of D-dimer values in normal healthy donor population: an indirect verification of the age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs for VTE exclusion. Blood. 2016;128:1432. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ercan Ş., Ercan Karadağ M. Establishing biological variation for plasma D-dimer from 25 healthy individuals. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2021;81:469–474. doi: 10.1080/00365513.2021.1947522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Covidence Systematic Review Software Veritas health innovation, Melbourne, Australia. www.covidence.org [accessed October 1, 2021]

- 14.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells G.A., Shea B., O'Connell D., Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M., et al. The Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta analyses. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp 2013 [accessed June 11, 2021].

- 16.Ancochea J., Izquierdo J.L., Soriano J.B. Evidence of gender differences in the diagnosis and management of coronavirus disease 2019 patients: an analysis of electronic health records using natural language processing and machine learning. J Womens Health. 2021;30:393–404. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holler J.G., Eriksson R., Jensen T.Ø., van Wijhe M., Fischer T.K., Søgaard O.S., et al. First wave of COVID-19 hospital admissions in Denmark: a nationwide population-based cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:39. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05717-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J., Zhang L., Chen Y., Wu Z., Dong X., Teboul J.L., et al. Association of sex with clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients: a retrospective analysis of 1190 cases. Respir Med. 2020;173:106159. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marik PE, DePerrior SE, Ahmad Q, Dodani S. Gender-based disparities in COVID-19 patient outcomes. J Investig Med. 2021. 10.1136/jim-2020-001641. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Minhas A.S., Shade J.K., Cho S.M., Michos E.D., Metkus T., Gilotra N.A., et al. The role of sex and inflammation in cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in COVID-19. Int J Cardiol. 2021;337:127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giacomelli A., De Falco T., Oreni L., Pedroli A., Ridolfo A.L., Calabrò E., et al. Impact of gender on patients hospitalized for SARS-COV-2 infection: a prospective observational study. J Med Virol. 2021;93:4597–4602. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin S., An H., Zhou T., Li T., Xie M., Chen S., et al. Sex- and age-specific clinical and immunological features of coronavirus disease 2019. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu D., Ding H.L., Chen Y., Chen D.H., Yang C., Yang L.M., et al. Comparison of the clinical characteristics and mortalities of severe COVID-19 patients between pre- and post-menopause women and age-matched men. Aging (Albany NY) 2021;13:21903–21913. doi: 10.18632/aging.203532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quaresima V., Scarpazza C., Sottini A., Fiorini C., Signorini S., Delmonte O.M., et al. Sex differences in a cohort of COVID-19 Italian patients hospitalized during the first and second pandemic waves. Biol Sex Differ. 2021;12:45. doi: 10.1186/s13293-021-00386-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nizami D.J., Raman V., Paulose L., Hazari K.S., Mallick A.K. Role of laboratory biomarkers in assessing the severity of COVID-19 disease. A cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10:2209–2215. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_145_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Review Manager (RevMan) The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; Copenhagen: 2008. Version 5.0. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Section 10.10.2 Identifying and measuring heterogeneity. Cochrane. 2022. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-10#section-10-10-2. [accessed May 7, 2022].

- 28.Wan X., Wang W., Liu J., Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin J.M., Bai P., He W., Wu F., Liu X.F., Han D.M., et al. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Front Public Health. 2020;8:152. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bjøri E., Johnsen H.S., Hansen J.-B., Brækkan S.K. D-dimer at venous thrombosis diagnosis is associated with risk of recurrence. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:917–924. doi: 10.1111/jth.13648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tagalakis V., Kondal D., Ji Y., Boivin J.F., Moride Y., Ciampi A., et al. Men had a higher risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism than women: a large population study. Gend Med. 2012;9:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinbrecher O., Šinkovec H., Eischer L., Kyrle P.A., Eichinger S. D-dimer levels over time after anticoagulation and the association with recurrent venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2021;197:160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cosmi B., Legnani C., Tosetto A., Pengo V., Ghirarduzzi A., Testa S., et al. Sex, age and normal post-anticoagulation D-dimer as risk factors for recurrence after idiopathic venous thromboembolism in the Prolong study extension. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1933–1942. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Section 10.11.5.1 Selection of study characteristics for subgroup analyses and meta-regression. Cochrane. 2022. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-10#section-10-10-2. [accessed May 24, 2022].

- 35.Favaloro E.J., Dean E. Variability in D-dimer reporting revisited. Pathology. 2021;53:538–540. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2020.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linkins L.A., Lapner S.T. Review of D-dimer testing: good, bad, and ugly. Int J Lab Hematol. 2017;39:98–103. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thachil J., Longstaff C., Favaloro E.J., Lippi G., Urano T., Kim P.Y., et al. The need for accurate D-dimer reporting in COVID-19: communication from the ISTH SSC on fibrinolysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:2408–2411. doi: 10.1111/jth.14956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurien S.S., David R.S., Chellappan A.K., Varma R.P., Pillai P.R., Yadev I. Clinical profile and determinants of mortality in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective analytical cross-sectional study in a Tertiary Care Center in South India. Cureus. 2022;14 doi: 10.7759/cureus.23103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu X.Q., Xue S., Xu J.B., Ge H., Mao Q., Xu X.H., et al. Clinical characteristics and related risk factors of disease severity in 101 COVID-19 patients hospitalized in Wuhan, China. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022;43:64–75. doi: 10.1038/s41401-021-00627-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Q., Yuan Y., Zhang J., Li J., Li W., Guo K., et al. Early predictors of severe COVID-19 among hospitalized patients. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36 doi: 10.1002/jcla.24177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]