Abstract

Since the first wave of COVID-19 in March 2020 the number of people living with post-COVID syndrome has risen rapidly at global pace, however, questions still remain as to whether there is a hidden cohort of sufferers not accessing mainstream clinics. This group are likely to be constituted by already marginalised people at the sharp end of existing health inequalities and not accessing formal clinics. The challenge of supporting such patients includes the question of how best to organise and facilitate different forms of support. As such, we aim to examine whether peer support is a potential option for hidden or hardly reached populations of long COVID sufferers with a specific focus on the UK, though not exclusively. Through a systematic hermeneutic literature review of peer support in other conditions (57 papers), we evaluate the global potential of peer support for the ongoing needs of people living with long COVID. Through our analysis, we highlight three key peer support perspectives in healthcare reflecting particular theoretical perspectives, goals, and understandings of what is ‘good health’, we call these: biomedical (disease control/management), relational (intersubjective mutual support) and socio-political (advocacy, campaigning & social context). Additionally, we identify three broad models for delivering peer support: service-led, community-based and social media. Attention to power relations, social and cultural capital, and a co-design approach are key when developing peer support services for disadvantaged and underserved groups. Models from other long-term conditions suggest that peer support for long COVID can and should go beyond biomedical goals and harness the power of relational support and collective advocacy. This may be particularly important when seeking to reduce health inequalities and improve access for a potentially hidden cohort of sufferers.

Keywords: Narrative hermeneutic review, Post COVID-19 syndrome, COVID recovery, Long COVID, Peer support, Health inequalities

1. Introduction

‘Long COVID’, the term preferred by those living with the condition (Callard and Perego, 2021), is a growing global problem. We follow recent evidence from the UK to define Long COVID as persistent COVID-19 symptoms >4 weeks after acute onset (National Health Service (NHS), 2022). Now affecting between 10 and 20% of British COVID sufferers, representing 2 million people (Office of National Statistics, 1st June 2022) and an estimated 200 million people worldwide (Chen et al., 2022). Yet, scepticism still exists around the nature, diagnosis and even existence of the condition.

Long COVID can persist for months or years; be severe and diverse; including ongoing fever, pain, extreme fatigue, breathlessness, newly arising mental health issues, and neurocognitive problems (Davis et al., 2021; NHS, 2022; Ziauddeen et al., 2021). When symptoms become chronic, this impacts on employment, caring responsibilities, and social activities and even more so for those from underserved groups that are more likely to have underlying health conditions and increased social isolation (Ladds et al., 2021; Office of National Statistics, 2021).

Literature supporting definition, assessment and diagnosis exists (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2022; World Health Organisation, 2021) but there are gaps in our understanding of what support people are seeking or need outside of formal healthcare arrangements and in particular the Long COVID clinics provided in the UK. The impetus for this review grew from the demographic disparity that exists between those people diagnosed with COVID-19 and those diagnosed with Long COVID. In the UK and America, for example, COVID-19 infection and mortality were highest amongst older people, minority ethnic communities, those from lower socio-economic backgrounds and men (Maness et al., 2021; Office of National Office for National Statistics, 2020; 2022a, 2022b). However, Long COVID data in the UK show an over-representation of White women aged 40–50 years (Office of National Statistics, 2021, 22). Moreover, preliminary results from recent unpublished research into clinic attendance, rates of Long COVID diagnosis and the membership of online Long COVID support groups affirm these broader demographic findings (Multi-disciplinary, Consortium Long COVID Project study, unpublished data).

It seems, then, that there may be a hidden cohort of people who are experiencing Long COVID symptoms but are not accessing formal Long COVID clinics and support. Based on data about COVID demographics, it would appear this hidden population is likely to be minority ethnic, older aged, male, and from lower Socio-economic status (SES) backgrounds, all groups already underserved in biomedicine and disadvantaged by health inequalities. Accurately identifying those people experiencing Long COVID and the best forms of support is, therefore, an important area of research in order to prevent the exclusion of a hidden cohort of sufferers.

With the paucity of evidence-based assessment and self-management guidance in the first wave of Long COVID, those affected sought validation, advice and support from one another on social media platforms (Callard and Perego, 2021; Rushforth et al., 2021). These virtual informal peer support groups grew, becoming catalysts for action and credence to the experience of Long COVID. In a climate where the voices of those living with ongoing symptoms were often silenced, the Long COVID narratives captured by Rushforth et al. (2021) starkly reveal the realities and loneliness felt amongst those rejected by the medical system and a powerful call to action during that early period of the pandemic. Indeed, the patient-driven advocacy (including a high proportion of people from healthcare backgrounds) and organising through peer-led online spaces has led to the recognition of Long COVID as a severe, enduring condition, shifting academic focus from solely acute management (Ladds et al., 2021; Ladds et al., 2020; Rushforth et al., 2021). The continued uptake of members to these groups also suggests benefit in these virtual spaces for ‘long haulers’ which warrants study and exploration (Brown et al., 2022).

Similarly, peer support has played a key role in the management of several long-term conditions such as diabetes and major trauma (Callard and Perego, 2021; Graham and Rutherford, 2016; Grant et al., 2021; Rushforth et al., 2021). It is well recognised as the most beneficial form of support for long term addictions, such as Alcoholics Anonymous whereby ideas of fellowship and peer accountability are the cornerstone of the programme (Kurtz, 2010).

As such, and given the origins of how the condition has been recognised and the denial of the condition from wider healthcare communities, the relevance of peer support for people living with the Long COVID is of significant interest. Adopting a systematic hermeneutic enquiry, we examine the role, types, and challenges of peer support and their possible value for those living with this emerging and enduring condition. Moreover, we focus on how peer support can best be made inclusive for under-represented, disadvantaged and underserved groups. In doing so, this paper also aims to provide some guidance for those developing peer support services wishing to ensure inclusivity and reach. To do this we draw on a wide peer support literature covering an array of conditions that share certain commonalities with Long COVID. For example, long term conditions that lead to substantial lifestyle changes and often necessitate rehabilitation, such as, diabetes, heart conditions, mental health conditions, head injury and strokes to name a few.

2. Method

We applied a hermeneutic method that has been used successfully in previous reviews covering similarly complex conditions that have serious public health implications such as heart failure (for details of the method, Boell and CecezKecmanovic, 2014; for successful application, (Greenhalgh et al., 2017) et al., 2017). Taking its name from the philosophical movement, hermeneutics is a theory of the interpretation of texts. It is iterative, with the interpreter(s) generating new meanings and avenues of enquiry as research questions develop through engagement with existing literature (Greenhalgh et al., 2017).

Mead and MacNeil (2006) describe the ways in which meaning is ‘storied’ in nature and generated through the articulation of lived experience. Moreover, retaining the value of storied meaning is crucial, argue Tovey and Manson (2004), when social scientists explore the relationship between relational health treatment approaches such as complementary alternative medicine and more biomedically informed treatment practice, such as nursing. In a similar way, peer support groups operate as a space for the sharing of lived experience through personal narratives. These stories draw on medical knowledge and re-appropriate it through the lens of lived experience. A narrative framework therefore lends itself to articulating the practice of this unique form of support by generating new meanings and understanding for how this support works.

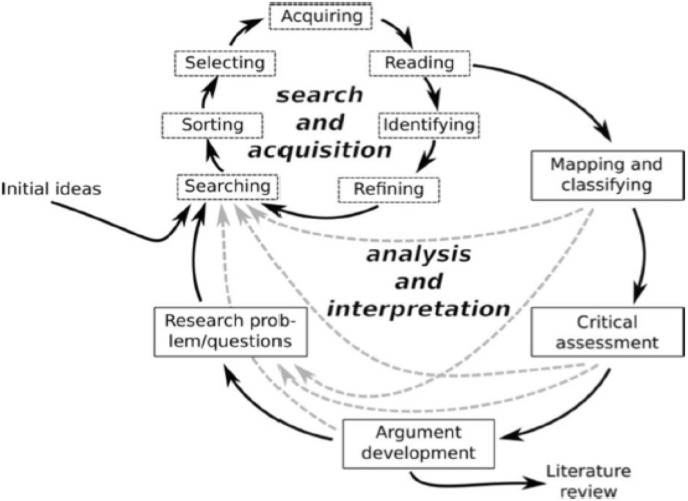

When adopting a hermeneutic methodology, there are two interwoven processes: (i) searching for, selecting and interpreting relevant literature, (ii) and then feeding back to reflectively develop research questions (Fig. 1 ). As papers accumulate, the researchers use the ideas and arguments formed to filter out less relevant papers. The method is both systematic and flexible, beginning with a predefined search strategy but also using progressive focusing to allow the researchers’ own evidence-driven arguments to play a role in the selection of papers (Boell and CecezKecmanovic, 2014; Greenhalgh et al., 2017).

Fig. 1.

Hermeneutic systematic review. Reproduced under creative commons licence fromGreenhalgh et al., 2017:3).

2.1. Search strategy

A number of relevant key words were identified, and the same search terms were used across the three databases: Google Scholar, Jstor, and PubMed. The following combinations of search terms were used: (“Long COVID”, “Post COVID” OR “Chronic”) AND (“Peer support” OR “Informal Support” OR “Social Support”, OR “Community-led Support OR “Grassroots Support”) AND (“framework” OR “model”). This enabled a rapid identification of highly-cited systematic reviews as well as a number of other types of papers which were relevant to the topic under study. We focussed initially on systematic reviews of peer support to develop an overview of the type of literature and findings available. We then moved on to looking at research papers such as single studies and literature reviews. It is important to note that though we do include some studies from a variety of contexts, including those from the Global South, we still only selected papers that were published in English. We make note here that this does exclude a wealth of literature that may be relevant to a more comprehensive global systematic review of peer support and therefore recognise the limitations of our own study.

The initial searches began on 30.12.2021 and continued until 13.01.2022. After this date, more papers emerged as the study unfolded (through snowballing). Citation tracking was carried out which maximised the snowballing effect. The process of citation tracking involved using google scholar to track where each of our included papers had been cited since they were published. This enabled us to identify new sources which were incorporated into the current study if they were relevant to the topic. Citation tracking is a powerful method for identifying high quality sources even in obscure locations.

Inclusion of papers was based on relevance and pre-prints were considered if they were highly relevant. We included highly cited papers as well as less highly cited ones which were relevant to the topic under study. This review focussed on systematic reviews initially because they aim to collate relevant empirical evidence which fitted in with our research aims. We then moved on to looking at research papers such as single studies and literature reviews which were relevant to the research questions.

2.2. Data extraction and synthesis

For each systematic review, single study and other research papers on peer support, we summarised key data and arguments, focusing on key questions, theories, methods, findings and scholarly arguments relevant to our research questions.

-

1.

What, if any, models of peer support are being adopted by people with Long COVID and what are their strengths and limitations?

-

2.

What can we learn from the wider literature on peer support and its effectiveness from studies of long-term conditions?

-

3.

What can we learn from studies of peer support aimed at tackling health inequalities and supporting disadvantaged and underserved populations?

We highlighted and summarised systematic reviews that were obtained through the citation tracking process which enabled further insights into key data and arguments from a wider range of sources. We used the hermeneutic principle to progressively refine and enrich our overall summary of the sample of primary sources and previous reviews. Each new source was added to this developing picture of the whole.

3. Findings

3.1. Overview

Findings are presented under several key headings that represent the narrative synthesis of our findings. In total, we reviewed 57 papers in our review. We begin by presenting the theoretical perspectives we define as underpinning current forms of peer support in our review, then we highlight three key themes (summarised in Table 1 ), we then provide a discussion of the implications of peer support for Long COVID and what peer support for the condition might look like (summarised in Table 2 ), and how we might balance the biomedical, relational and socio-political aspects of peer support. The papers reviewed lent themselves to analysis under several key themes and as such they are included under each appropriate heading, one to three, in the table below. The Overviews and commentaries’ theme include papers or websites that explore peer support from an applied and or narrative lens.

Table 1.

Included papers.

Table 2.

Dimensions of peer support to consider when designing Long COVID services.

| Dimension | Options |

|---|---|

| Philosophical/theoretical basis | Biomedical (education for self-management) Relational (support and belonging) Socio-political (advocacy, campaigning and role of social context) |

| Definition of health | Medical (health as absence of disease, illness and/or injury) Social/functional (ability to fulfil valued social roles and associated activities) Idealist (health is a state of physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease of infirmity (World Health Organisation, 2002). |

| Delivery model | Service-led (developed and run as part of clinical services) Community-based (developed by or in partnership with community members, social services or third-sector organisations) Online (developed and run by patients and carers on social media) |

| Type of interaction | One-to-one (face to face, online or hybrid) Small groups (face to face, online or hybrid) Social media networks (may be extensive and international) |

| Mechanism by which peer support may work | Sharing ‘factual’ knowledge about the condition Sharing system knowledge (e.g. how to access/navigate healthcare) Sharing practical tips and strategies for living with the condition Vicarious and social learning (i.e., learning by observing others) Validation of experience Reciprocity (in which participants gain from both giving and receiving support, leading to a greater sense of wellbeing and friendship) Emotional support from the group (may reduce reliance on family members) Signposting to community-based or online resources Development of critical consciousness Organising for advocacy and campaigning Patient-led action research |

| Measures to improve uptake of peer support by socially excluded groups | Co-design peer support programmes with community partners and embrace transcultural understanding Promote ethos of trust and respect; where needed, address lack of trust in particular services or programmes Offer a flexible service that responds to needs, including outreach, listening to feedback, flexible opening hours, breaks to accommodate fatigue and cognitive impairment, travel, childcare, and providing the services participants want Involve participants directly in their own care and promote autonomy, strength and asset-based approaches Select peer supporters from within target communities Acknowledge cultural-historical experiences of particular groups (e.g. diasporas) and how these may compound the personal trauma of illness and encounters with services Address language, literacy including digital literacy, and cultural health capital issues Obtain adequate funding Avoid exclusionary language and communication approaches Avoid ‘over professionalisation’ of peer support programmes (which may inadvertently impose an overly biomedical model and normative assumptions of the majority user group) Design programmes to take account of intersectionality of social determinants of health (e.g. poor and female and limited English speaker) Avoid power imbalances between peer supporters and service users |

3.2. Perspectives on peer support: biomedical, relational and socio-political

Peer support for health conditions can come in multiple forms and the breadth and scope of these often relate to the particular definition of health being taken forward. These definitions are characterised as the medical definition of health as being the absence of disease or injury, a social definition of health that considers the impact of wider social relations and inequalities, and an idealist model (seen in the WHO definition) that sees health as not merely the absence of disease or injury but that health is complete physical, social and mental wellbeing.

Moreover, the definition most favoured shapes the accent, timbre, and we suggest, ultimate success of peer support design and delivery, particularly when seeking to address health inequalities. We note three contrasting peer support perspectives within the literature; we have termed these the biomedical, relational and socio-political. Differences between these framings are associated with both the language used to conceptualise support and the rationale, justification and methods offered for peer support. Relatedly, we note three key peer support design and delivery models—within an existing health service (‘service-led’ often top-down) and external to it (‘community-based’ and ‘via social media platforms online’ often bottom-up) which draw in different ways on the three theoretical perspectives (biomedical, relational, and socio-political) and their particular understandings of ‘good health’. Table 2 draws the findings together under these theoretical and design models to highlight what structures of peer support may work best for people with Long COVID.

3.2.1. Biomedical framings of peer support

Health-based peer support can be understood through the lens of biomedicalisation. According to Adele Clarke et al. (2003), biomedicine represents the increasingly complex multidirectional processes of medicalisation that often focus on health technologies, risk, surveillance, and medical information management and knowledge production. The five facets of biomedicalisation share an over-arching focus on co-transformation and production of bodies and technologies. Within this, self-management and surveillance is linked to how technologies reshape the body as a site of risk, and introduce new modes for surveillance and risk reduction. For example, such approaches view peer support as an educational self-management intervention, lending itself well to assessing the impact of particular interventions and knowledge sharing in terms of measurable outcomes – such as, disease progression or symptom control (Casteltein et al., 2008; Grant et al., 2021). However, such approaches tend to view patients, their bodies, experiences, and conditions as compartmentalised. For example, Castelein, et al., (2008) carried out a randomised control trial in which the impact of peer support was examined for patients with psychosis. Although incorporating aspects of wellbeing, these were broken down into measurable components such as: personal networks; social support and positive social interactions; self-efficacy; self-esteem; and quality of life or general health. These outcomes were measured through questionnaires that yielded a numerical score for each variable of interest. While helpful up to a point, this kind of approach is reductionist because the patient's multifaceted and interconnected experience is compartmentalised into variables which are assumed to interact according to a more or less generalisable model and set of rules, producing similar disease or illness mitigation outcomes across a diverse sample (Dollarhide and Oliver, 2014; Elkins, 2009). Biomedical models of peer support are not designed to explore or address – and may unintentionally overlook – the relatedness between a person's, or group's, social context, inter-personal relationships and behaviours that combined make up the lived experience of a particular condition or illness, nor do they centrally address structural inequalities (Mullard, 2021). Quite often biomedical models of peer support are, then, seen through the lens of self-quantification, encouraging patients to construct an understanding of self through reconfiguring the quantifiable truths about their conditions and the hopes of wellness. In doing so, patients co-create experiential knowledge about their conditions and how to manage them (Moreira and Palladino, 2005). Despite its limitations, the biomedical lens often drives the design and delivery of service-led peer support (Casteltein et al., 2008; Grant et al., 2021).

3.2.2. Relational framings of peer support

What we call relational approaches to peer support are designed with the individual's wider social context in mind. They seek to take a holistic and humanistic view of lived experience, including physical, mental and social wellbeing. The emphasis is on treating the whole individual recognising that ‘good health’ is not simply the absence of disease. Such framings focus primarily on the social and personal benefits of peer support; whilst they do not deny that people who gain from peer support may also improve their scores on medically-determined outcome measures, the latter are given less emphasis.

Models we deem relational emphasise a process in which individuals gain a sense of belonging through interacting with those with shared experiences to create wider understandings of both self, community, and the condition that brought them together in the first place, thus reduce isolation and increase the validation of the lived experience of managing the condition (Mavhu et al., 2013; Willis et al., 2018; Juul Nielsen and Grøn, 2012). This form of biosociality, whereby what brings these people together is their shared biological condition, operate as particular forms of citizen projects aiming to create commensality amongst people with the same biological conditions (c.f., Rabinow, 1992; Rose and Novas, 2005). An extension of this biocitizenship is the establishment of reciprocity between members. In a study into experiences of peer support for people living with dementia, reciprocity of support was an important factor; enabling patients to both give and receive support led to a greater sense of wellbeing and friendship (Keyes et al., 2016). Additionally, ideas of reciprocity successfully underpin many forms of very well established peer support programmes for drug and alcohol addictions, such as Alcoholics Anonymous. The use of second stories or the reciprocal recounting of lived experiences to the group, for example, establish what Arminen (2004) highlights as alignment and identification with the previous speaker. This happens through a process of transvaluation that mutually serves to present alternative ways of understanding your own narrative.

Questions of reciprocity are seen as key for effective and authentic peer support (Mead et al., 2001; Rebeiro Gruhl et al., 2016; Repper and Carter, 2011; Gillard, 2019). Reciprocity, however, is a complex concept that has been discussed at great length by anthropologists and social scientists more generally. For example, it has been perceived as the foundation of kinship in anthropology (Bloch, 1975) and the basis of universal or ‘normative’ stability in social systems in functionalist sociology (Becker, 1973; Gouldner, 1960 respectively). Indeed, Kost and Jamie (2022) build on Davenport et al.‘s., (2018) concept of ‘knowing community’ to highlight how online peer support for fat women (their emphasis) develops a form of ‘knowing kinship’ that through a reciprocity of understanding negative experiences can act as forms of everyday resistance to the fatphobia met in medical encounters, which ultimately supports the development of ‘cultural health capital’. First coined by Shim (2010) as “the repertoire of cultural skills, verbal and nonverbal competencies, attitudes and behaviours, and interactional styles, cultivated by patients and clinicians alike, that, when deployed, may result in more optimal health care relationships” (Ibid.: 1).

Reciprocity, however, can occur in many forms and is practised in various ways cross-culturally. Essentially, it is about obligation, dependency and the particular cultural logics of relatedness which reflexively adapt in a performative environment (Sahlins, 2013). In this framing, peer support groups or situations can be considered a performative context in which the obligation works to unify people through biosociality on the understanding that they will protect and understand each other in that performative space. As we note below, however, reciprocity in peer support is not an inevitable benefit experienced by all but embedded within the varying commensalities of status found within a particular group or dyad. Members who are disempowered in various ways may benefit less or not at all.

3.2.3. Socio-political framings of peer support

Structural inequalities, disadvantage and discrimination have a powerful impact on access to health services and health outcomes (Marmot, 2010; 2020). Some peer support groups originate from exclusion, with roots in social action to address the social and political struggles of different communities for recognition and rights (Pattinson et al., 2021). The most well-known health-related example of this is the Independent Living Movement (ILM), which grew out of activism around the social, physical and treatment barriers experienced by people with physical disabilities (Mead and MacNeil, 2006). Rehabilitation paradigms in the 1970s and 80s were dominated by a medical view of disability, which viewed disability through a deficit lens. Conversely, ILM, mobilised through organisations such as Union of the Physical Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS), promulgated a social model of disability to advocate for a shift in focus: it was society that was deficient—for example, in accessible spaces, enabling attitudes, laws to safeguard the rights of those with disabilities, and so on (Oliver, 1990, 2013).

Contemporary examples of socio-political peer support movements aim to recognise the interplay of social, medical and embodied experiences of exclusion. For example, Pattinson et al. (2021) highlight inequities in mental health support for LGBTQ + communities who have higher rates of mental distress but lower rates of seeking support services, due partly to fear of homophobia and limited staff awareness. Young people identifying as LGBTQ + may seek support from one another rather than approach mainstream services because their individual needs are not being met (Nazroo and Becares, 2021).

Another example is minority ethnic and faith communities. In settings where mainstream services pay little attention to cultural awareness or the systemic relationship between social inequality, racism and health, community-led grass-roots forms of peer support emerge, often with little or no funding (Hope and Ali, 2019). Peer support initiatives for marginalised communities of colour in the UK have addressed breastfeeding Black mothers and maternal health; depression; HIV; and dementia carers (Ingram et al., 2008; Templeton et al., 2003). Not always borne from exclusion, these forms of support supplement other forms of support in order to focus on the specific needs of groups. Community-based peer support activities that involve a Community Health Worker (known as a link worker in the UK) with shared lived experience have shown to be highly successful for increasing uptake of health services—for example improved uptake of screening and treatment services for African-Caribbean men with prostate cancer in the UK and uptake of breast cancer screening amongst Latina women in California (Centre for BME Health, 2008; Mishra et al., 1998 respectively). More recently, a programme to deploy Community Health Workers from specific targeted communities have been trained in America to help prevent the spread of COVID-19 amongst high risk populations (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). However, it is rare for link workers in the UK to be systematically drawn from the specific demographic communities they seek to serve. Moreover, whilst peer support community groups may sometimes be commissioned by statutory healthcare providers, they are often poorly integrated with mainstream services and hence less able to connect their members with the full range of support available to the majority ethnic population (Mir et al., 2001). The danger is that it becomes people from marginalised groups that bear the burden of support for these groups which then allows mainstream services to focus on ‘everyone else’.

3.2.4. Complementarity of different framings

Biomedical, relational and socio-political framings of peer support are not incompatible. Greenhalgh et al's., (2005) narrative research with ethnic minority groups with type 2 diabetes, for example, demonstrated the benefits of combining medical and social understandings of health through a holistic peer support setting. Participants learnt key principles of biomedical management (e.g. knowledge about medication, diet and exercise), but such learning needed to be made meaningful through various personal and interpersonal changes, such as rebuilding identity after diagnosis and developing a care network, and achieved partly through collective action such as campaigning for women-only gym sessions.

Socio-political framings, then, can both highlight the structural causes of health inequities and the ways these interact to produce ill health. Mir and Sheikh (2010) suggest that focusing on models that aim to increase knowledge and capacity within communities has advantages but may not address the underlying inequalities causing disproportionate rates of ill health; peer groups may also need to lobby for more responsive healthcare services and demand that attention be paid to the structural determinants of health (Mir and Sheikh, 2010).

The United States (US) philanthropic organisation Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has supported initiatives around the world which combine biomedical goals (disease control) with attention to relational and socio-political goals (Peers or Progress, 2022b; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2022). The ‘Peers for Progress’ initiative is built on the notion that people with (say) diabetes can draw on peer support to help them adopt particular behaviours and lifestyles aimed at improving their glycaemic control and cardiovascular risk (hence, a biomedical component) but that such initiatives will have limited success unless they are culturally tailored and include social support and their community is empowered and equipped to provide the resources they need (Peers or Progress, 2022a). Approaches of this kind could have traction amongst underserved communities living with Long COVID.

3.3. Peer support in long COVID

To date, peer support for Long COVID within the UK has occurred almost exclusively in online groups, whose membership is disproportionately White, middle-aged and female. This reflects the current pattern of diagnosis, both self-reported and through primary care, of Long COVID but contrasts with severe forms of acute COVID-19, which disproportionately affects older men from minority ethnic groups [Office of National Office for National Statistics, 2020)]. The discrepancy may be because Long COVID affects a different demographic, but structural inequalities in access and care are likely to play a part because evidence shows that marginalised groups do not access care and do not get referred as readily as majority populations (Goddard and Smith, 2001; Mclean et al., 2003; Murray and Pearson, 2006). Moreover, the interplay of cultural health capital and the lack there of with unresponsive medical professionals, can often underpin the poor representation of marginalised groups. Shim (2010) notes that patient-provider interactions often contain inherent power dynamics and that the way these encounters unfold can generate non purposeful inequalities in the healthcare provided. Even though her focus is on the US, cultural health capital extends well beyond these territorial boundaries and evidence from both low and high income countries suggest similar patterns of disproportionate care are generated through the often unintentional display of unequal dynamics within the patient-provider encounter (Bloom et al., 2008; Greenhalgh et al., 2017; Peitzmeier et al., 2020; Poteat et al., 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2021; Subramani, 2018). Whilst as yet unproven, it is likely that there is a hidden cohort of people with Long COVID who have not yet sought, generated, or been able to access formal support and are therefore missing from the current picture of Long COVID both within the UK and internationally. Moreover, online peer support may not suit disadvantaged groups that do not have regular access to the internet or the technology that facilitates it. As such, understanding the different roles and impacts of models of peer support may help social scientists and policy makers better understand both the support needs, options for effective support, and strategies to reduce unequal power dynamics in support encounters for marginalised cohorts.

Due to the emerging and rapidly developing nature of Long COVID there is a pressing need for new forms of support for these patients. We focus our paper on developing models of peer support by looking at what lessons can be learned from other long term conditions. As such, our findings provide a useful starting point from which to assess the potential value of this intervention for Long COVID—both in general and specifically in relation to reducing health inequalities.

3.4. How has peer support been defined?

Models of peer support delivery are notoriously difficult to systematically review due to differences in how the term was defined and operationalised in primary studies (Eysenbach et al., 2004; Fisher et al., 2015). Our sample of studies illustrates that peer support can take place as one-to-one interactions, within a group setting, face-to-face, via telephone or virtually. Peer support interventions can range from informal, small group gatherings to wide-reaching online social media platforms, as well as formalised pathways with set protocols, referral systems, and funding in place. No single standardised model of peer support is likely to be universally applicable, due to the contextual nature of participants’ needs and the different balance required between biomedical, relational and socio-political emphasis and, more prosaically, the practicalities of service provision. Our literature review reveals that a model of peer support is often dependent on the definition of health being adopted (social, medical, idealist, for further details see Table 2) and how the peer support is developed such as, whether it is organised within or outside the health service.

A helpful framework for designing a bespoke model for peer support delivery has been developed by Heisler (2006). These authors recommend that contextual considerations are linked to all stages, and attention given to who is the target population. Such considerations include the following questions. What are the aims of the peer support? Will educational, counselling or behavioural approaches be used? What is the process through which peers are recruited, trained and supervised? How will information be given to those receiving support? What is the expectation of support in terms of location, frequency, duration and flexibility of contact and extent to which peer support is integrated into other health services?

The above questions are useful for service-led initiatives but (perhaps inadvertently) imply a somewhat biomedical framing oriented to improving patients' knowledge and changing their behaviour. However, there are important questions to be asked of all three: biomedical, relational and socio-political perspectives, such as: Which stakeholders should be around the table when the peer support programme is designed? Whose voices risk being unheard and how might we better hear these? How will power be shared among stakeholders? Whose definition of programme success should be used? How will conflicts be resolved if people don't agree?

3.5. Studies on peer support and long COVID

Peer support for Long COVID emerged in a unique context. In the early months after Long COVID was first described, access to clinical services was restricted and little had been written in the medical literature; some doctors did not even believe the condition existed. In that context, many people came together in online groups and discovered common experiences both with the illness and with the frustrations of trying to access services (Rushforth et al., 2021). A strong community of peer support developed via social media, articulating the nature of Long COVID and depicting it as a real condition requiring active management and specialist support (Callard and Perego, 2021; Rushforth et al., 2021). Members of these groups described them as having played a pivotal role in improving awareness of their unmet needs, improving their wellbeing, allowing information-sharing and reducing isolation (Callard and Perego, 2021; Graham and Rutherford, 2016; Grant et al., 2021; Hope et al., 2021; Rushforth et al., 2021).

Hope et al. (2021) carried out a review of the Critical and Acute Illness Recovery Organization (CAIRO) during the pandemic, an organisation committed to improving the quality of life of patients and families after critical illness. They suggest that health systems were required to rapidly develop a more robust infrastructure to improve the recovery and social integration of adult COVID-19 survivors which ultimately led to growth of peer-led models for ICU patients in America. The authors proposed a number of stages including preparation, recruitment, facilitation, a trauma informed approach, planning logistics and debriefing. However, the programmes developed were largely led by healthcare professionals online and concerns were raised by the authors of how effectively participants of all racial, physical and cognitive backgrounds were included.

The paper provides solid theoretical contributions to how peer support can improve the lives of Long COVID patients particularly after discharge from ITUs. However, a weakness of this study, and an area of future research which the authors highlighted, was that we need to understand more about posttraumatic growth before we can fully understand the role of peer support in long COVID and other chronic conditions. Given the high prevalence of traumatic experiences in ICU survivors and their families, it was argued that facilitators should use a trauma-informed approach which acknowledges that all types of traumas may adversely affect how survivors interact and cope. Whether peer support programmes can be useful in facilitating posttraumatic growth (defined as a positive psychological change that can come from processing a trauma) is a question that could be investigated in future research studies. Suffice to say, a trauma-centred approach may also be useful for building inclusive peer support spaces, particularly if our definition of trauma is extended beyond simply the trauma of the condition itself to one that includes recognition of other types of trauma that patients may be already coping with.

Indeed, Russell et al. (2022) highlight in their qualitative interviews with 20 people living with Long COVID, that many had negative first encounters with healthcare professionals leaving them frustrated and further traumatised by their experience. For this group, the authors note how online peer support helped them to gain recognition of their condition as well as develop strategies to educate healthcare professionals that were, in the early days of the condition, reluctant to listen to them. They argue, however, that because these early online support groups contained unregulated content, which added to anxiety amongst those interviewed.

A similar study carried out by Day (2022) with 11 online Long COVID peer support users in the UK, found that such groups were filling the gaps of NHS services through lack of geographical availability, or what was felt to be lack of adequate provision, as well as providing a space for validation and shared understanding for a condition that sufferer's existing support networks may not still fully understand. The study presents the complexity and diversity of varying experiences within peer support, highlighting the dichotomy of expectations, needs and impacts. For example, whilst shared learning around management strategies were valued by some participants, others felt, similar to the participants in Russell et al., 2022 article, that the unregulated nature allowed for potentially harmful content to circulate and burdened members to determine for themselves the safety of recommendations. Conflicting views were also expressed around the psychological impact of utilising social media based peer support with some seeking it in times of low mood and others actively avoiding it. To hear about the prolonged journeys of some sufferers elicited fear and anxiety for some, although successful recovery stories were valued by several as offering hope. Of note, and contrast to established literature, Day (2022) found that in person support was felt to enhance the connections made especially as smaller groups versus the vastness of the online forums, indicative that a flexible, range of complimentary mediums should be considered for future peer support co-design.

What is clear, however, is that Long COVID peer support groups have so far played a key relational role. They also played an important socio-political role (i.e., campaigning and advocacy). Within the UK, for example, many peer support groups for Long COVID originated in the campaigning group ‘Long COVID Support’ whose large membership is drawn mainly from the UK and US. This group was established in May 2020 during a period when patients experiencing prolonged COVID symptoms were not having their voices heard. Offshoot groups have developed that are based on regional needs, research involvement, or for specific age groups (e.g. children) or clinical focus (e.g. physiotherapy) (National Voices, 2022).

3.6. Studies of peer support and their limitation in other clinical conditions

In our review we highlight 31 studies covering a range of conditions including: HIV, diabetes, cancer, long term mental health conditions, spinal cord injuries, dementia, chronic pain and stroke. Studies of peer support undertaken within clinical services have tended to take a quantitative and experimental approach. Randomised controlled trials (Casteltein et al., 2008; Cherrington et al., 2018; Legg et al., 2011; Kallish and Adshead, 2018; Muller et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2010; Sweet et al., 2018), typically run via a hospital clinic and with a waiting-list control group, have shown that peer support groups may produce significant improvements in depression and feelings of isolation in conditions which have some shared characteristics with Long COVID, including diabetes (which, similar to Long COVID, requires major lifestyle change and may fluctuate in severity over time), psychosis (a condition that can become chronic and have relapsing and remitting phases) and spinal cord injury (a condition requiring an adaption to a new identity and functional abilities).

Despite the fact that positive results were reported by these studies, their study designs often raise questions about the transferability of findings. For example, Casteltein et al. (2008)'s trial of peer support for patients with psychosis in the Netherlands drew its population from hospitalised cohorts. They randomly selected 106 patients through the allocation of concealed envelopes across four different mental health centres. Patients were then told that they were either on a waiting-list and could expect to be part of the programme in 8 months or had been allocated a position in the peer support group (16 × 90-min sessions delivered biweekly over 8 months). During the sessions patients decided topics to discuss either in pairs or as a group; the sessions were guided by nurses who were trained in the study protocol. The nurses also received some training on the ‘minimal guidance attitude’, which was to provide structure, continuity, and a sense of security without actively interfering with the group process (Casteltein et al., 2008: 65). However, the findings could be explained by a Hawthorne effect, given that the peer support groups were run by hospital nurses who were presumably known to the patients. Whilst randomised controlled trials are sometimes depicted as a ‘gold standard’ (Timmermans and Berg, 2010), poor design (inadequate blinding, poorly comparable control groups) can reduce internal validity and selective sampling (drawing all participants from a hospital cohort) can reduce external validity (Hu et al., 2020). These are relevant limitation for studies that wish to be systematically transferable. Similar kinds of critiques can be levied at qualitative studies, however, the epistemological premises upon which such studies are designed are fundamentally different. Qualitative studies do not necessarily seek to find objective measures, instead it is the context and narrative of participants reasoning that is championed as insightful data. That is not to say that one is necessarily more valuable than the other, it is simply that they generate different ways of understanding a phenomena.

Clinic-based research trials of peer support groups often include process evaluations which seek to identify mechanisms of success, explanations for failure or partial success, and estimates of cost. Øgård-Repål (2021), for example, conducted a scoping review of 53 studies of peer support for people with HIV that included 20,657 participants from 16 countries. Of the 53 studies, 43 included evaluations of the effectiveness of peer support and 10 evaluations of the implementation, process, feasibility and cost of peer support. Out of this, they identified the key functions of peer support and concluded that the most common were linked to clinical care and community resources and assistance in daily management, with only one study directly related to chronic care (Ibid., 2021: 1). Limitations in the primary studies, according to these reviewers, included an over-emphasis on quantitative data with limited qualitative findings, over-representation of high-income countries (despite HIV being commoner in low-income countries), lack of attention to context (many interventions were introduced into communities experiencing complex living arrangements that created barriers to accessing effective and affordable HIV health services), exclusion of non-binary genders (a group at particular risk of HIV), and a predominance of service-led models with few examples of community-based and other non-mainstream routes of support. The skewed sample of primary studies likely led to under-recognition of the role social stigma plays in the everyday lives of people living with HIV/AIDS, the impacts of this on seeking healthcare support, and the wealth of peer campaigning and support around this issue. Qualitative studies based in the community were able to reveal how people living with HIV/AIDS may contribute, through a more bottom-up, relational and socio-political design (including collective campaigning and support), to the reduction in HIV/AIDS stigma in Uganda (Embuldeniya et al., 2013; Mburu et al., 2013).

Peer support groups have been widely studied in chronic pain, a condition that is frequently misunderstood or misdiagnosed by health care professionals. Peer support may provide the emotional and social assistance that received little attention in the biomedical model of care (Carr, 2016). Qualitative studies have linked the reduction in depression to increased sense of belonging and sharing of experiences (Chemtob et al., 2018; Haas et al., 2013; Litchman et al., 2018; Monroe et al., 2017; Power and Hegarty, 2010).

Our findings from other chronic conditions present a mixed picture. They highlight the varied quality of peer support design and delivery, and also the varied quality of primary research studies (hence the questionable trustworthiness of findings). On the one hand, it is clear a literature exists to highlight the effectiveness of peer support for health outcomes in individuals with chronic illnesses (Berg et al, 2021; Dale et al., 2012; Gatlin et al., 2017; Kowitt et al., 2018; Lyons et al., 2021; Odgers-Jewell et al., 2017; Sokol and Fisher, 2016; Thompson et al., 2022). But on the other hand, the literature hints at the dangers of peer support, particularly when ‘over-professionalised’ and overly biomedical in ethos (see HIV/AIDS examples above).

Many of the studies we reviewed focused on measuring the efficacy of peer support groups on a predefined primary outcome (thus emphasising the biomedical elements of the intervention). Many also studied the relationship between the leaders of peer support sessions and members or the design and structure of peer support groups but very few considered the relationship between the peers themselves. Yet as noted in the introduction, a major element at play in the peer support process is likely to be the reciprocity experienced by the individuals in the peer support space—and this may not necessarily be equally experienced. It may depend, for example, on whether the peer support is organised as group activity or a dyadic 1:1 activity. Bracke et al. (2008) set out to empirically study the reciprocity experienced in peer support programmes for people in mainstream mental health settings. They suggest that the generalised exchange of support in a group setting is likely to produce greater reciprocity because status and power disparities, however muted or incrementally measured, will tend to be more evident in dyadic interactions.

Several studies in our sample highlighted challenges with access and engagement in peer support groups for chronic conditions—for example, groups were not always able to adapt to the changing recovery needs of patients. Several authors recommended a hybrid model which combined on-line and face-to-face options to provide more flexibility in engagement (McCosker, 2018; Muller, 2014). However, few studies exploring different models had been rigorously evaluated (Dale et al., 2012; Grant et al., 2021; Lloyd-Evans et al., 2014).

Though many of the studies in our sample offered evidence of beneficial effects of engagement in peer support groups, such as improvements in overall recovery (Barclay and Hilton, 2019; Carter et al., 2020; Grant et al., 2021,Øgard-Repål, 2021), many have given limited attention to the contexts of the studies they have showcased in their reviews and the impact of different health systems and health funding landscapes on the development of peer support.

3.7. Studies of peer support as a means of reducing inequalities

Some qualitative studies in our sample highlighted the ways in which peer support groups may help to overcome apprehensions in communities that have experienced mistreatment, discrimination and social exclusion from mainstream health provision. Particularly for those affected by poverty, low health or system literacy, limited English, or extremes of age. The studies illustrate the complex ways in which patients have to navigate health systems, feel a lack of support or trust in service providers, and how discussing these can provide opportunities for system change (Erangey et al., 2020; Goldman et al., 2013; Harris et al., 2015; Hope and Ali, 2019; Im and Rosenberg, 2015; Pattinson et al., 2021).

In their systematic review, Sokol and Fisher (2016) assessed the reach, effectiveness, and forms of peer support for individuals they termed ‘hardly reached’ (to challenge the more commonly used and somewhat pejorative term ‘hard to reach’ or ‘hard-to-engage’); 39 of the 47 peer support studies they examined had a higher participant retention rate if they embedded a strategy of trust and respect (83% retention compared to 48% retention of those that did not have this strategy) (Ibid., 2016: e1). They explored studies of peer support groups that adopted conceptual and operational strategies to engage hardly reached communities.

Overall, these authors conclude that peer support that aims to reach those often excluded from mainstream provision display a flexible response to different contexts, including the intended audience, health problems and setting. The emphasis on flexibility and responsiveness is key to the relational approach that aims to nurture a narrative, sharing environment for those attending a peer support space. Although this systematic review had many positive features, it appeared to treat categories of disadvantage in disaggregated ways rather than exploring how multiple forms of disadvantage (e.g. racial discrimination, disability, poverty and gender) may interact.

Bagnall et al. (2015) conducted a global systematic review of 57 peer support programmes within prisons and young offender institutions—a group vulnerable to significant health inequalities. According to the authors, peer support education interventions had a positive impact on reducing risky behaviours and improved emotional outcomes amongst the participants, and thereby contributed to achieving health and social goals within the prison environment and beyond. Those delivering the peer support appeared to gain the trust of prison authorities. The peer support intervention appeared particularly beneficial to those prisoners who were resistant to professional advice through traditional authoritative means. Whilst the review reached positive conclusions about the value of peer support, the original studies included in the review were heterogeneous in design, covered multiple countries with very different judicial systems, and varied in quality. The question of publication bias also arises (studies of peer support that generated neutral or negative findings would be less likely to reach publication).

Hu et al. (2020)'s systematic review and meta-analysis compared the impact of peer support interventions among ethnic minorities (Black, Latinx and Asian Americans) with interventions designed to promote the uptake of colorectal screening in United States America (USA) by way of a mailed faecal occult blood test kit and printed instructions. Peer support raised awareness of screening services. Interventions based on an empowerment model that addressed racism and medical mistrust, were culturally specific, led by members of the community, and also contained practical support to participants such as transport or childcare services they were far more beneficial than other interventions across the full range of communities included (Black, Latinx and Asian Americans). Whilst perhaps unsurprising, these findings illustrate how peer support programmes that follow the principles of trust and respect, flexibility, user involvement and community partnership identified by Sokol and Fisher (2016) can achieve reduction in a well-documented area of inequality (poor uptake of cancer screening by underserved minority groups).

A quantitative study by Ojeda et al. (2021) used programme survey data to test the hypothesis that the availability of peer support reduced inequalities in service use among young minority groups aged 16–24 across two counties in the US (Los Angeles and San Deigo). The authors defined peer support as having a peer specialist on staff; the primary outcome measure was the annual number of outpatient mental health visits (on the assumption that peer support would improve attendance for such visits). They also examined the relationship between racial/ethnic concordance of youth and peer specialists and use of outpatient services. They found that of 13,363 youth included in the data, 46% received services from programmes that employed peer specialists. Broadly, availability of peer support was significantly associated with more outpatient visits and fewer service use disparities among disadvantaged minority groups, perhaps as a result of a relatable peer supporter who could draw on shared experience (Ibid., 2021: 295).

The importance of shared experience was also highlighted by Turner et al.‘s., (2021) mixed method study into the enrolment and engagement in peer coaching for diabetes management among low-income Black veteran men. These authors highlight the importance of developing and respecting the autonomy of patients and the development of what they call an ‘autonomy-supportive’ communication style (defined as one that promotes “shared understanding, decision making, and power while working to understand people's unique perspectives and meet emotional and informational needs”) by peer coaches (Turner et al., 2021: 537). This, they argue, is particularly important for Black men where other forms of patient-centred communication have failed as it foregrounds patients as resilient, self-determined and resourceful, thereby conveying their capability for self-management strategies and for engaging in the programme. The qualitative interviews showed the importance of having peer coaches who had shared experiences and common ground with the participants, especially lived experience of the condition and shared ethnicity. The authors also suggest that incorporating dimensions of masculinity (ie, sex norms, roles, sex role conflict, and perceptions of masculinity) and race centrality into future investigations could provide insight into how those factors shape diabetes management for Black men in the US context (Turner et al., 2021: 538).

A specific disadvantage of peer support when it is developed and led by majority group service-leaders, not affected by the condition, is that unless a diverse group of those living with the condition are involved at the design stage, groups can unintentionally exclude communities with intersecting needs.

Hope and Ali (2019) highlight that although socially excluded communities often experience worse health outcomes, they are also less likely to seek out formalised support networks. In their narrative study of mental health peer support drawing on both their own lived experience as case studies and secondary sources, they cite a number of barriers to such groups accessing formalised peer support, for example: limited transcultural understanding within the recovery approaches of formalised peer support groups; the lack of trust in mental health services among some communities; approaches to language and communication that are inadvertently exclusionary, and lack of funding.

Minority ethnic communities are less represented in patient and survivor movements more generally. The authors suggest that models of empowerment that tend to underpin grass roots peer support (which are often explicitly linked to what we have called socio-political framings and an advocacy agenda) are often lacking in mainstream provision (which tend to have a more biomedical framing), or that such models conform to dominant White values (Hope and Ali, 2019: 74).

Hope and Ali (2019) show how a deeper understanding of social exclusion and intersectionality is necessary for effective service-led peer support and offer various guided exercises and best practice strategies practitioners could use in their sessions. These include acknowledgement and acceptance of the historical experience of mental health services felt by ethnic minorities; recognition of the importance of their involvement in service design and delivery; co-production; and a recognition of intersecting inequalities that impact on patient experience, past trauma and stigmatisation. Additionally, they argue the over-professionalisation of service-led peer support can threaten the transformational power of peer support.

Beales and Wilson (2015) in their position paper “Peer Support: The what, why, who, how and now” examine the workings of the Service User Involvement Directorate at Together, a large voluntary sector provider of mental health peer support in the UK. They do so from the position of working for the organisation at a time that was four years after the UK mental health strategy No Health Without Mental Health (Department of Health, 2011). They suggest that this legislation led to an over-professionalisation of peer-support that has limited its transformational power. Taking a more ethnographic, participatory observation approach, the paper raises some interesting theoretical points about the ethos underlying peer support; and how peer support is structured and delivered on the ground in the particular context of this organisation, at a time where peer support was becoming more mainstream and therefore, according to Beales and Wilson (2015), less authentic.

They argue that for peer support to be authentic and useful it must have the following characteristics:

“… it must be service user led, based on supporters and clients being people of equal value with mutuality of benefit and joint responsibility for outcomes and finally, peer support services must be the result of genuine service user-led co-production between staff, peer supporters and people accessing the service” (Ibid., 2015: 316).

Moreover, they argue that the key factor influencing the success of peer support is the question of who leads it and in particular the role of intersecting identities and accurate peer support matching can play in the overall success of the initiative. For example, they highlight how the identity and social experience of peer support leaders are crucial in the matching process:

“While someone might experience different mental health conditions to the person who is supporting them, it could mean more for them to have a fellow Bangladeshi woman supporting them, or someone else who has gone through a gender transition, than someone whose diagnosis looks the same on paper” (Ibid., 2015: 317).

The organisation, Together, according to the authors, incorporates these dimensions into the recruitment of peer support workers from the service user membership. Avoiding power imbalances between the peer supporter and the service user is especially effective because it:

“… transforms stigma into understanding; it transforms people from passive recipients of what the medical model and society have always told them was good for them into allies that see another way; it changes people from being seen as ‘scroungers on benefits’ into vital leaders in their own and others' recoveries” (Ibid., 2015: 321–22).

Beales and Wilson provide an insightful and contextually rich lens on the challenges and value of peer support outside mainstream services (and the dangers of ‘over-professionalising’ peer support models), they write as staff members of an organisation that receives specific funding for a particular model.

4. Discussion

4.1. 4.1. summary and critique of findings

This hermeneutic review has synthesised a diverse literature on peer support in Long COVID, comparable chronic conditions that lead to substantial changes in lifestyle and impact daily activities, and in relation to reduction of inequalities. We identified a relatively large dataset (57 papers) including several systematic reviews covering dozens of primary studies. Overall, these studies demonstrated a positive impact of peer support on various biomedical outcome measures along with numerous socio-emotional benefits and impacts on services and societal attitudes (e.g. reduction in stigma). Many of the Long COVID peer support groups have been exclusively online and led by service users, there are, however, many insights from service-led peer support models for other chronic conditions including mental health, chronic pain, and HIV/AIDS, and also from studies which sought to draw on peer support to reduce inequalities for disadvantaged and underserved groups.

However, many questions remain about the effectiveness of peer support groups both in general and in specific contexts and circumstances, for several reasons. First, the primary studies were of variable methodological quality; there were various design flaws and many studies were underpowered. Second, the commonly used waiting-list control group for trials of peer support meant that a Hawthorne effect (i.e., positive impact of non-specific attention), rather than peer support itself, may account for some or all of the differences between study arms. Third, the large number of primary studies which appeared to show a small positive impact of peer support groups, along with few or no studies showing large positive or negative impacts, suggests that publication bias may have influenced findings.

4.2. Implications for the design of peer support for long COVID

Table 2 summarises the implications for design of Long COVID peer support services. As detailed in the introduction, Long COVID is a complex condition with an unpredictable course and physical, mental and social impacts. Findings from comparable conditions suggest that well-designed peer support services combining biomedical, relational and socio-political framings may well produce positive changes in disease biomarkers and ongoing course of the condition (i.e., such services are likely to deliver biomedical benefits). Moreover, adopting a co-production framework that unites the top-down interests of service providers with the bottom-up needs of patients would further lead to better outcomes.

This review has also highlighted the social and relational benefits of peer support, with reciprocity as an important factor in improving the wellbeing of patients with chronic conditions (Keyes et al., 2016; Litchman et al., 2018; Muller et al., 2014)—a benefit that may have particular salience to Long COVID patients, many of whom experienced confusion and struggled to gain legitimacy, assessment and support in the early months of their illness (Rushforth et al., 2021). Findings that peer support groups may help improve individual patients’ feelings of autonomy, relatedness and competence (Casteltein et al., 2008; ChemtobCaron et al., 2018; Sweet et al., 2018) and build self-efficacy and self-determination (Bugental, 1964; Ryan and Deci, 2000) also offer hope to Long COVID patients who may have become demotivated and disengaged as a result of their chronic and unpredictable illness. The positive role of peer support groups in providing members with information, resources and connections within their networks (Hope and Ali, 2019; Im and Rosenberg, 2015) could potentially help overcome the confusion and isolation experienced by Long COVID patients and their families. Whether these socio-emotional and socio-material benefits actually occur will depend on the detail of the specific interventions, their contexts and the fidelity of its delivery.

4.3. Balancing biomedical, relational and socio-political aspects of peer support

Much has been achieved through biomedical models of peer support, but these models have been rightly criticised for being overly concerned with eliminating diseases rather than holistically considering the individual's psychosocial wellbeing and wider social relations. Moreover, ‘deficit-based’ models (which define patients as deficient in health, knowledge, skills and so on) located in clinics can demean and even infantilise patients (Scott and Doughty, 2012). To minimise these negative effects, peer support programmes could incorporate strength-based or asset-based approaches that utilise community assets such as voluntary sector organisations, faith-based centres and facilities, lunch clubs, and baby groups (Hope and Ali, 2019; Mead et al., 2001). In this way, the person with Long COVID might shift from being someone suffering from shame and blame to someone who is aware of shared experiences and risks, is part of a collective narrative and contributes to a body of shared practical knowledge, which in turn can generate deeper understandings of recovery linked to a holistic model of health incorporating wellbeing, autonomy and the ability to participate in society (Marmot, 2006; World Health Organisation, 2002).

Whilst online peer support networks for Long COVID have had evident success and thousands of patients have gained much from them (especially relational benefits), this model needs to be supplemented by a different approach to ensure that the benefits of peer support are extended to all socio-economic groups. Evidence reviewed above from the inequalities literature consistently shows that community development and empowerment approaches that are tailored to the needs of individuals and communities through co-production, co-design and co-delivery are important for ensuring inclusive peer support spaces (Heisler, 2007; Scott and Doughty, 2012; Tang and Fisher, 2021). Despite the fact that this evidence is indirect, it suggests that these aspects of peer support are likely to benefit Long COVID patients from disadvantaged groups (e.g. those affected by poverty, low health or system literacy, limited English, extremes of age). However, it is important to note that the current demographics for people living with Long COVID does not necessarily fit the criteria of excluded groups being that they are largely from White ethnic minority backgrounds, of relatively middle-class socioeconomic status and largely located in the Global North (Office of National Statistics (ONS), 2021, 2022). As such, the study, “Multi-disciplinary, Consortium Long COVID Project” [study pseudonym] has a workstream, led by (anonymous), exploring the experiences of a potentially ‘hidden cohort’ of marginalised communities that are living with the condition but are not yet attending Long COVID clinics to better understand the barriers to healthcare provision for these groups. As such, it is possible to infer that the strategies to overcome apprehensions around discrimination raised in the studies into the role of peer support for reducing inequalities for other conditions, may have great potential for marginalised, minoritsed and more underserved communities that are living with Long COVID.

Attention to digital inclusion and acknowledgement of socioeconomic barriers to participation will be an important feature of empowering and inclusive peer support groups. Both face-to-face options (for those who lack digital connection or capability, or who prefer non-digital services (O'Connor et al., 2016)) and virtual options (for those unable to attend in person (McCosker, 2018; Muller et al., 2014)) are likely to be needed. Peer support groups that provide practical support such as transport or childcare are likely to be more inclusive of those from deprived communities.

A key finding of this review is the need to ensure minority ethnic communities are represented within peer support groups to increase the chance that members of those communities will find them accessible and relatable. In some cases there will be mistrust of health services as a result of a lack of cultural understanding or a history of racism and discrimination (Dovidio et al., 2008). Community-led initiatives that are culturally specific and led by members of minority communities also need to be resourced and supported. Minority ethnic groups are often overrepresented in deprived communities, so attention to socio-economic factors is particularly important in promoting the diversity of uptake.

One of the commonest symptoms of Long COVID is fatigue; other common symptoms are cognitive impairment, breathlessness and chronic pain. The design of peer support interventions must take account of these realities, offering flexible options to accommodate various disabilities and needs. This may, for example, include online options for people unable to travel to sessions; frequent rest breaks; and accommodating the fact that fluctuating symptoms may mean that patients miss sessions.

4.4. Strengths and limitations of this study

We have used a rigorous qualitative systematic review method to identify and synthesise studies addressing peer support in Long COVID, related chronic conditions and initiatives to reduce inequalities. The iterative hermeneutic method allowed us to draw together literature from various disciplinary traditions and consider the relevance to our goal of designing peer support services as part of the multi-disciplinary, consortium Long COVID Project study.

As with all secondary research, a limitation of this study is the limitations of the primary studies on which our work and previous syntheses were based. Many studies were small and methodologically flawed, and publication bias was likely. Most primary studies were undertaken in a handful of countries (notably USA), and very few provided sufficient details of context to allow assessment of transferability. The predominance of randomised controlled trials with narrow definitions of success (e.g. a biomedical primary outcome measure) leaves unanswered questions about real-world impact.

5. Conclusion

Long COVID is a serious, disabling condition with uncertain prognosis. Peer support in the form on online networks has benefited many Long COVID patients already, but does not suit everyone in its current format. This study has identified some principles and preconditions for developing more inclusive and accessible peer support programmes which have potential for extending the biomedical, psychosocial and advocacy benefits of peer support to a more diverse population. The multi-disciplinary, consortium Long COVID Project study will draw on our findings to develop and pilot such programmes in collaboration with our patient advisers and linking with community, faith and voluntary sector groups as appropriate in participating sites.

We suggest that future research should evaluate how effective peer support groups are in increasing engagement in health services and the degree to which health services pro-actively engage with peer support groups. Qualitative research into the full range of Long COVID peer support activity (including socio-political forms and barriers to accessing online support) would elucidate more clearly how peer support groups contribute to recovery and support for Long COVID by providing rich descriptions of unique experiences of individuals from diverse backgrounds. Future research is also warranted into how reciprocity develops (or why it fails to develop) in the context of peer support and its role for improving outcomes in Long COVID.

Author contributions

JM conceptualisation (co-lead), methodology (equal), writing original draft preparation (lead), writing-review and editing (lead), investigation (equal); JK investigation (equal), methodology (equal) writing original draft (equal); AP investigation (equal), methodology (equal), writing original draft (equal); CR contribution of patient comments and review (lead); GM writing-review and editing (equal); MS funding acquisition (lead), writing – review and editing (equal); TG conceptualisation (co-lead) methodology (lead), funding acquisition (lead), supervision (lead), writing – review and editing (co-lead).

Patient involvement

On completion of the first draft of the review, we shared our findings with patient advisors on the LOCOMOTION study, and further refined the paper in the light of their comments.

Ethics, integrity and dissemination

LOCOMOTION is sponsored by the University of Leeds and approved by Yorkshire & The Humber - Bradford Leeds Research Ethics Committee (ref: 21/YH/0276). The research and production of this paper was carried out with strict adherence to ethical standards in research and intellectual integrity as set out by the Journal. Dissemination plans include academic and lay publications, and partnerships with national and regional policymakers to influence service specifications and targeted funding streams.

Study registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05057260; ISRCTN15022307.

Funding statement

This research is supported by Research England Policy Support Fund (Ref RG. RMRE.124682.021) It is independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) (long COVID grant, Ref: COV-LT2-0016). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of NIHR or The Department of Health and Social Care.

Declaration of competing interest

TG is a member of Independent SAGE and NHS England long COVID national task force. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This paper is part of a collaborative study entitled ‘Long Covid Multidisciplinary consortium: Optimising treatments and services across the NHS’ (LOCOMOTION), funded by the National Institute for Health Research (grant number COV-LT2-0016). The authors acknowledge the contribution of the wider LOCOMOTION consortium members and study Project Manager Dr Carole Paley, who provided valuable logistical and wider support. We also thank the LOCOMOTION Patient and Public Advisory Group and Patient Advisory Network contributors who gave their time to review and provide valuable feedback on earlier drafts. In particular we would like to acknowledge Dr Clare Rayner (PPI Lead on LOCOMOTION) and Ian Tucker Bell (patient advisor).

Handling Editor: Stefan Timmermans

Data availability

A hermeneutic systematic review that draws on secondary sources. Only published data has been used in this article.

References