Abstract

Background

Prompt, effective CPR greatly increases the chances of survival in out-of-hospital c ardiac arrest. However, it is often not provided, even by people who have previously undertaken training. Psychological and behavioural factors are likely to be important in relation to CPR initiation by lay-people but have not yet been systematically identified.

Methods

Aim: to identify the psychological and behavioural factors associated with CPR initiation amongst lay-people.

Design: Systematic review

Data sources: Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycInfo and Google Scholar.

Study eligibility criteria: Primary studies reporting psychological or behavioural factors and data on CPR initiation involving lay-people published (inception to 31 Dec 2021).

Study appraisal and synthesis methods: Potential studies were screened independently by two reviewers. Study characteristics, psychological and behavioural factors associated with CPR initiation were extracted from included studies, categorised by study type and synthesised narratively.

Results

One hundred and five studies (150,820 participants) comprising various designs, populations and of mostly weak quality were identified. The strongest and most ecologically valid studies identified factors associated with CPR initiation: the overwhelming emotion of the situation, perceptions of capability, uncertainty about when CPR is appropriate, feeling unprepared and fear of doing harm. Current evidence comprises mainly atheoretical cross-sectional surveys using unvalidated measures with relatively little formal testing of relationships between proposed variables and CPR initiation.

Conclusions

Preparing people to manage strong emotions and increasing their perceptions of capability are likely important foci for interventions aiming to increase CPR initiation. The literature in this area would benefit from more robust study designs.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO: CRD42018117438.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12872-022-02904-2.

Keywords: CPR, Bystander, Laypeople, Systematic review, Psychological, Behavioural, Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

Introduction

Out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) has a devastatingly high mortality rate [1]. Survival to hospital discharge ranges between countries from < 1% [2] to 25% in the best European centres [3], reflecting differences in case identification, demography, geography and emergency service provision [4]. Reducing the mortality associated with OHCA is a strategic priority of many countries [5–10].

Prompt, effective bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is the most important factor determining survival from OHCA, increasing survival almost 4-fold [11, 12]. Registry data show most OHCA occur at home [2, 13, 14]. Even the most prompt emergency medical response will take at least a few minutes (median 6 mins.) [15], and so the response of others in the home is critical.

Governments and charities invest significantly in training lay-people in CPR [16–18]. Despite this, those in OHCA often do not receive CPR prior to the arrival of emergency services [19]. Even amongst those who are trained, less than half attempt CPR when required [20]. Increasing the proportion of lay-people trained in CPR who actually apply their skills in a real emergency situation is essential [21] as otherwise much of the effort expended in training lay-people will not improve outcomes for patients.

Research relating to CPR training of lay-people has largely been concerned with increasing knowledge and achieving competence in the skill of CPR. Questions of how best to teach CPR tend to be answered by studies using skills performance (e.g. compression depth) and assessment of knowledge as outcome measures [22, 23]. However the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation [24] and behavioural science [25] would suggest that psychological factors (e.g. people’s attitudes about CPR) are likely to be critical in explaining whether or not people initiate CPR. To date there has not been a systematic synthesis of this literature.

The aim of this review was to synthesise evidence relating to lay-people initiating CPR and to identify the psychological and behavioural factors that facilitate or inhibit people’s willingness to perform CPR.

Method

Protocol and registration

In line with best practice, a review protocol was published (2018) and registered with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of systematic reviews (protocol number 117438): https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=117438.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion

Types of study

All primary study designs.

Types of participants

Lay members of the public (i.e. not healthcare professionals or others who receive CPR training as a part of their job, e.g. lifeguards) of any age.

Types of outcome measure

Studies which contained psychological/behavioural data (not CPR knowledge or training status) related to 1) why the participants did or did not perform CPR in real emergencies or 2) would or would not perform CPR in a hypothetical or simulated situation. CPR was defined as performing chest compressions (CC), mouth-to-mouth ventilations, applying an Automated External Defibrillator (AED) or any combination of these.

Exclusion

Papers which did not report a primary empirical study (e.g. reviews, editorials, opinion pieces) were excluded.

Information sources and search strategy

Six electronic databases - Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycInfo and Google Scholar- were searched for publications from inception of each database to 13th December 2019 (search strategy is supplied in supplementary materials Additional file 1). Supplementary searches included: a) reference lists of included studies, b) citations of included studies (Science Citation Index (SCI), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI), c) hand-searches of titles (Jan 2005 – Jan 2020) of Resuscitation and a further update database search performed 01/06/21.

Study selection

Screening of titles was undertaken independently by two reviewers (BF and DD) to exclude titles that were obviously irrelevant. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied to abstracts of studies and irrelevant abstracts were excluded. Inter-rater agreement kappa was 0.85, pabak kappa = 0.85. Full texts considered potentially relevant by either reviewer were screened independently (BF and DD). At full-text stage, any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by discussion.

Assessment of methodological quality and risk of bias

The methodological quality of studies was assessed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for quantitative studies [26] and the Joanna Briggs Institute’s Quality Assessment and Review Instrument (QARI) for qualitative studies [27]. Included studies were independently assessed by two reviewers (BF and CT) for methodological quality, with discrepancies being resolved through discussion.

Data extraction

Guided by the CONSORT guidelines [28] and the published protocol, the following data were extracted for each study: study details (author & date, location, study duration, objectives), study methods (design, setting, target population, sample size estimation, actual sample size, sampling and recruitment method, behavioural and psychological data, analysis, dates of recruitment) and study results.

BF and SM independently performed data extraction on 20% of the included studies (n = 20) to assess reliability. No discrepancies in independently extracted data were found and the remainder were extracted by a single researcher (BF or SM).

Synthesis and analysis

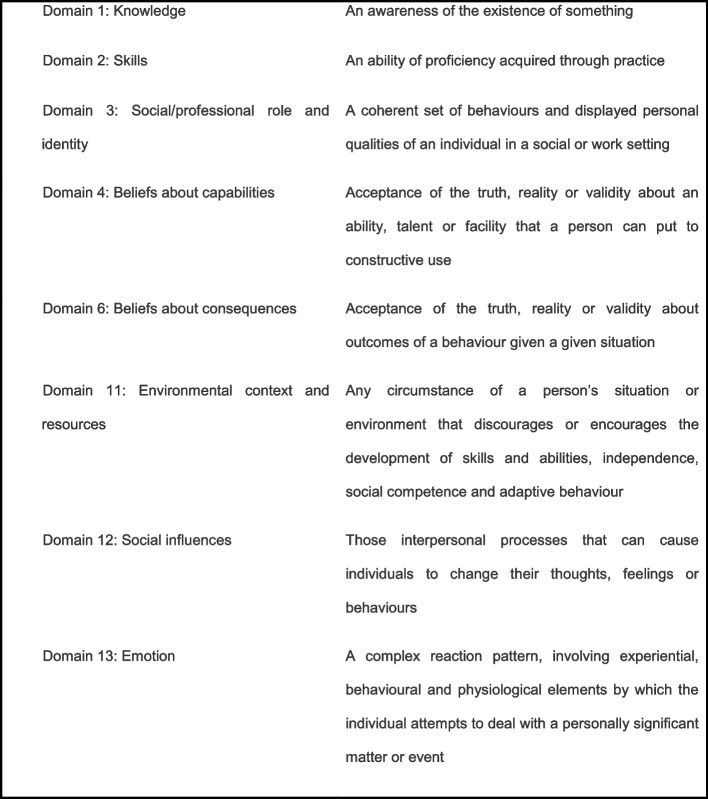

Behavioural and psychological factors identified during extraction were grouped into conceptually similar ‘factors’ by BF: 51 individual factors were identified. To facilitate interpretation, this large number of factors were grouped using categorisations or domains from the Theoretical Domains Framework Version 2 [29] (a validated, comprehensive, theory-informed approach to identifying determinants of behaviour). Definition of domains referred to in this paper are provided in Box 1. Domain categorisations were confirmed by a second reviewer (DD).

Included studies were differentiated according to the study population, study design and whether factors were identified by participants in response to an open question or endorsed from a list of factors presented by researchers. In order to facilitate comparisons studies were grouped according to the summary statistics used and p-values and Odds Ratios compared where possible. We prioritised 1) the most ecologically valid data [30, 31] (i.e. real-life OHCA calls and accounts of people who had actually witnessed OHCA), 2) studies which formally assessed posited relationships and 3) methodologically strong studies (i.e. assessed as low risk of bias) in the findings section.

Results

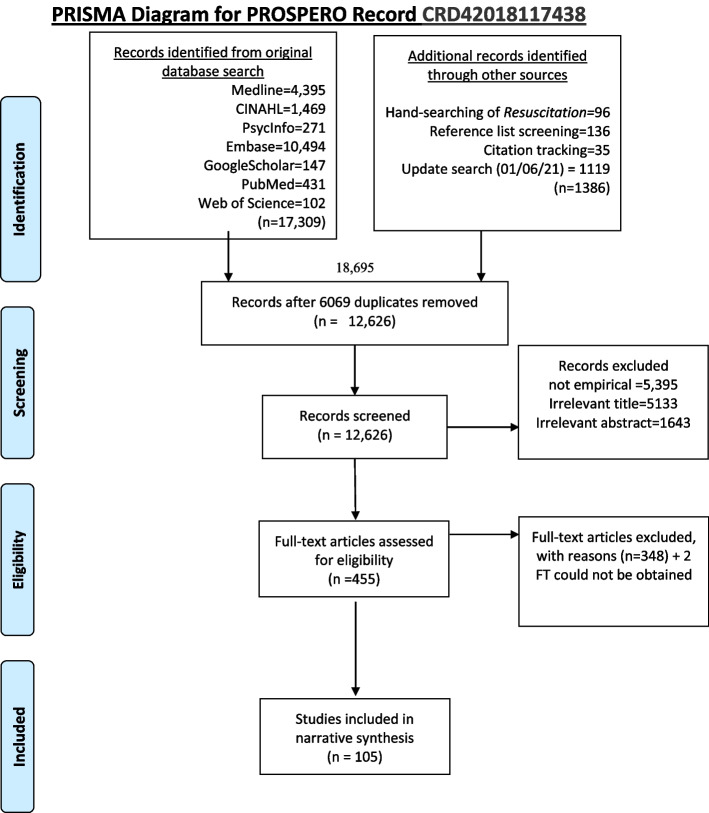

Original database searches conducted on 13th Dec 2018 (see PRISMA diagram, Fig. 1) identified 17,309 citations with 87 studies included after screening for eligibility. An update search conducted 01/06/21 identified 1119 additional titles, 15 of which were assessed as eligible. Hand-searching of Resuscitation (Jan 2005-Dec 2021) identified 96 potentially relevant titles, seven of which had not already been identified by database screening, none met the inclusion criteria. Reference lists of included studies identified an additional 136 papers, 26 of which had not been previously identified, two studies were eligible and included. Finally, citation tracking identified 35 potentially relevant titles, seven not previously screened and one study included. Therefore, a total of 105 studies were included in the narrative synthesis.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram

Description of included studies

Table 1 summarises the main characteristics of the 105 included studies comprising a total of 150,820 participants. The studies were published between 1989 and 2021 and conducted across 30 countries. The studies were heterogenous in design and included: randomised controlled trials (n = 6); non-randomised trials (n = 1); a quasi-experimental deign (n = 1), prospective cohort study (n = 1); before and after studies (n = 15); cross sectional studies (n = 67), qualitative studies (n = 9) and studies examining actual OHCA calls to Emergency Medical Services (n = 5).

Table 1.

List of included studies

| Author(s) | Country | Study Type | Participants | (n=) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aaberg et al. 2014 [32] | Denmark | Before and after study | High School students | 399 |

| Alhussein et al. 2021 [33] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥18 years) | 856 |

| Alshudukhi et al. 2018 [34] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥18 years) | 310 |

| Anto-Ocra et al. 2020 [35] | Ghana | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥18 years) | 277 |

| Axelsson et al. 1996 [36] | Sweden | Cross-sectional survey | People who reported making a CPR attempt between 1990 and 1994 | 742 |

| Axelsson et al. 2000 [37] | Sweden | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥18 years) who had received training in basic CPR in January 1997 | 1012 |

| Babic et al. 2020 [38] | Slovenia | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥18 years) | 198 |

| Becker et al. 2019 [39] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥18 years) who attended CPR training event | 677 |

| Bin et al. 2013 [40] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional survey | High school students | 575 |

| Birkun & Kosova 2018 [41] | Crimea | Cross-sectional survey | Adult (≥18 yrs) | 384 |

| Bohn et al. 2012 [42] | Germany | Prospective cohort | Grammar school pupils (age 10 and age 13) | 280 |

| Bouland et al. 2017 [43] | USA | Before and after study | Laypeople (≥14 years) | 238 |

| Bray et al. 2017 [44] | Australia | Cross-sectional survey | Adult (≥18 yrs) | 404 |

| Breckwoldt, Scholesser & Arntz 2009 [45] | Germany | Cross-sectional survey | Witnesses of an OHCA | 138 |

| Brinkrolf et al. 2018 [46] | Germany | Cross-sectional survey | Witnesses of an OHCA | 101 |

| Case et al. 2018 [47] | Australia | Retrospective analysis of emergency calls for OHCA | Calls to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 120 |

| Chen et al. 2017 [48] | China | Cross-sectional survey | Adult laypersons (≥18 yrs) + 3 < 18 years | 1841 |

| Cheng et al. 1997 [49] | Taiwan | Cross-sectional survey | Families of cardiac patients and general public | 856 |

| Cheng-Yu et al. 2016 [50] | Taiwan | Before and after study | Adults (≥20 years) | 401 |

| Cheskes et al. 2016 [51] | Canada | Cross-sectional survey | Adult (≥18 yrs) | 428 |

| Chew et al. 2009 [52] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional survey | School teachers | 73 |

| Chew et al. 2019 [53] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional survey | Adult (min age NR) participants at a mass CPR training event | 6248 |

| Cho et al. 2010 [54] | Korea | Before and after study | Lay people aged 11 years and over | 890 |

| Compton et al. 2003 [55] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | School teachers | 201 |

| Coons & Guy 2009 [56] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Adult (≥18 years) | 755 |

| Cu, Phan & O’Leary 2009 [57] | Australia | Cross-sectional survey | Caregivers of children presenting to the Emergency Department (≥18 years) | 348 |

| Dami et al. 2010 [58] | Switzerland | Retrospective analysis of emergency calls for OHCA | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 738 |

| De Smedt et al. 2018 [59] | Belgium | Cross-sectional survey | Schoolchildren aged 10–18, teachers and principals | 929 |

| Dobbie et al. 2018 [60] | Scotland | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥16 years) | 1027 |

| Donohoe, Haefeli & Moore 2006 [61] | England | Qualitative: focus groups | Adults (≥16 years) | NR |

| Dracup et al. 1994 [62] | USA | Randomised Controlled Trial | Family members of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 172 |

| Dwyer 2008 [63] | Australia | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥18 years) | 1208 |

| Enami et al. 2010 [64] | Japan | Before and after study | Adults (≥17 years). New driver licence applicants | 8890 |

| Fratta et al. 2020 [65] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Attendees at large public gatherings (aged ≥14) | 516 |

| Han et al. 2018 [66] | Korea | Before and after study | Family members (≥18 years) of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 203 |

| Hauff et al. 2003 [67] | USA | Retrospective analysis of emergency calls for OHCA | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 404 |

| Hawkes et al. 2019 [68] | UK | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥18 years) | 2084 |

| Hollenberg et al. 2019 [69] | Sweden | Randomised Controlled Trial | School students (13 years) | 641 |

| Huang, Hu & Mao 2016 [70] | China | Cross-sectional survey | School and University students (13–21 years) | 1407 |

| Hubble et al. 2003 [71] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | High school students | 683 |

| Hung et al. 2017 [72] | Hong Kong | Cross-sectional survey | College and University students (≥15 years) | 351 |

| Iserbyt 2016 [73] | Belgium | Before and after study | Secondary school pupils | 313 |

| Jelinek et al. 2001 [74] | Australia | Cross-sectional survey | General public (age not recorded) | 803 |

| Johnston et al. 2003 [75] | Australia | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥18 years) | 4490 |

| Kandakai & King 1999 [76] | USA | Before and after study | College students | 214 |

| Kanstad, Nilsen & Fredriksen 2011 [77] | Norway | Cross-sectional survey | Secondary school students (16–19 years) | 376 |

| Karuthan et al. 2019 [78] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional survey | College students | 393 |

| Kua et al. 2018 [79] | Singapore | Before and after study | School students (11–17 years) | 966 |

| Kuramoto et al. 2008 [80] | Japan | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥15 years) | 1132 |

| Lam et al. 2007 [81] | Hong Kong | Cross-sectional survey | Laypersons who attended the CPR course (aged ≥7 years) | 305 |

| Lee et al. 2013 [82] | South Korea | Before and after study | College students | 2029 |

| Lerner et al. 2008 [83] | USA | Retrospective analysis of emergency calls for OHCA | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 168 |

| Lester, Donnelly & Weston 1997 [84] | Wales | Cross-sectional survey | First year high school pupils | 233 |

| Lester, Donnelly & Assar 1997 [85] | Wales | Cross-sectional survey | General public | 241 |

| Lester, Donnelly & Assar 2000 [86] | UK | Cross-sectional survey | Participants who had attended a CPR course | 416 |

| Liaw et al. 2020 [87] | Malaysia | Before and after study | University employees (non-medical) | 184 |

| Locke et al. 1995 [88] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Lay people (minimum age not reported) & health care providers | 975 |

| Lu et al. 2017 [89] | China | Cross-sectional survey | College students | 609 |

| Lynch & Einspruch 2010 [90] | USA | Randomised Controlled Trial | Adults (≥18 years) | 1065 |

| Maes et al. 2015 [91] | Belgium | Before and after study | Hospital visitors (≥13 years) | 85 |

| Magid et al. 2019 [92] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | College students | 588 |

| Mathiesen et al. 2017 [93] | Norway | Qualitative: interviews | Witnesses of an OHCA | 10 |

| Mausz, Snobelen & Tavares 2018 [94] | Canada | Qualitative: interviews/focus groups | Witnesses of an OHCA | 15 |

| McCormack, Damon & Einsenberg 1989 [95] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Witnesses of an OHCA | 34 |

| Mecrow et al. 2015 [96] | Bangladesh | Cross-sectional survey | Lay people (≥10 years) | 721 |

| Meischke et al. 2002 [97] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Older adults (minimum age not reported) | 159 |

| Moller et al. 2014 [98] | Denmark | Qualitative: interviews | Witnesses of an OHCA | 33 |

| Nielsen et al. 2013 [99] | Denmark | Before and after study | Adults (≥15 years) | 1639 |

| Nishiyama et al. 2019 [100] | Japan | Cross-sectional survey | University students | 5549 |

| Nolan et al. 1999 [101] | Canada | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥45 years) | 786 |

| Nord et al. 2016 [102] | Sweden | Cluster randomised trial | Schoolchildren | 1124 |

| Nord et al. 2017 [103] | Sweden | Cluster randomised trial | Schoolchildren | 587 |

| Omi et al. 2008 [104] | Japan | Cross-sectional survey | High school students | 3316 |

| Onan et al. 2018 [105] | Turkey | Quasi-experimental study | High school students (aged 17–18) | 77 |

| Parnell et al. 2006 [106] | New Zealand | Cross-sectional survey | High school students | 494 |

| Pei-Chuan Huang et al. 2019 [107] | Taiwan | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥20 years) | 1073 |

| Platz et al. 2000 [108] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Family members of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 100 |

| Rankin et al. 2020 [109] | Australia | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (18–21 years) | 178 |

| Riou et al., 2020 [110] | Australia | Retrospective analysis of emergency calls for OHCA | Call to Ambulance service with OHCA where caller initially did not agree to perform CPR | 65 |

| Ro et al. 2016 [111] | Korea | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥19 years) | 62,425 |

| Rowe et al. 1998 [112] | Canada | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥44 years) | 811 |

| Sasaki et al. 2015 [113] | Japan | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥15 years) | 4853 |

| Sasson et al. 2013 [114] | USA | Qualitative: focus groups | Laypeople (minimum age not stated) | 42 |

| Sasson et al. 2015 [115] | USA | Qualitative: focus groups | Laypeople (≥13 years) | 64 |

| Schmid et al. 2016 [116] | Costa Rica | Cross-sectional survey | Laypeople (minimum age not stated) | 370 |

| Schmitz et al. 2015 [117] | Netherlands | Randomised Controlled Trial | High school students | 201 |

| Schneider et al. 2004 [118] | Austria | Before and after study | Survivors of OHCA and people who know them | 112 |

| Shams et al. 2016 [119] | Lebanon | Cross-sectional survey | University students | 948 |

| Shibata et al. 2000 [120] | Japan | Cross-sectional survey | High school students and teachers | 626 |

| Sipsma, Stubbs & Plorde 2011 [121] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥18 years) | 1001 |

| Skora & Riegel 2001 [122] | USA | Cross-sectional survey (qualitative analysis) | Laypersons who had provided out-of-hospital CPR to strangers | 12 |

| Smith et al. 2003 [123] | Australia | Cross-sectional survey | Householders (age not reported) | 1489 |

| Sneath & Lacey 2009 [124] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥18 years) | 78 |

| So et al. 2020 [125] | Hong Kong | Before and after study | High school students (12–15 years) | 128 |

| Swor et al. 2006 [20] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Witnesses of an OHCA | 684 |

| Swor et al. 2013 [126] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Witnesses of an OHCA | 30 |

| Tang et al. 2020 [127] | China | Cross-sectional survey | High school students (senior, age NR) | 397 |

| Taniguchi, Omi & Inaba 2007 [128] | Japan | Cross-sectional survey | High school students and teachers | 3444 |

| Taniguchi et al. 2012 [129] | Japan | Cross-sectional survey | High school students and teachers | 1946 |

| Thorén et al. 2010 [130] | Sweden | Qualitative: interviews | Partners of people who experienced OHCA | 15 |

| Vaillancourt et al. 2013 [131] | Canada | Cross-sectional survey | Adults (≥55 years) | 192 |

| Vetter et al. 2016 [132] | USA | Non-randomised trial | High school students | 412 |

| Wilks et al. 2015 [133] | Hong Kong | Cross-sectional survey | Secondary school students (15–16 years) | 383 |

| Winkelman et al. 2009 [134] | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Teacher candidates | 582 |

| Zinckernagel et al. 2016 [135] | Denmark | Qualitative: interviews and focus groups | Secondary school leaders and teachers | 25 |

Methodological quality

Of the quantitative studies, four [58, 69, 103, 110] were identified as strong, six as moderate [83, 90, 102, 117, 125, 131] with the remaining 87 quantitative studies rated ‘weak’ (see Table 2). There was a predominance of non-randomised designs, uncontrolled confounders, and use of unvalidated data collection methods. All qualitative studies were assessed as of sufficient quality for inclusion but also varied in quality (n = 8).

Table 2.

EPHPP Quality Assessment of included studies

| Selection Bias | Study Design | Confounders | Blinding | Data Collection Method | Withdrawals & Drop outs | Global rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aaberg et al. 2014 [32] | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Alhussein et al. 2021 [33] | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Weak |

| Alshudukhi et al. 2018 [34] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Anto-Ocra et al. [35] | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak |

| Axelsson et al. 1996 [36] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Axelsson et al. 2000 [37] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak |

| Babic et al. 2020 [38] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Becker et al. 2019 [39] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Bin et al. 2013 [40] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Birkun & Kosova 2018 [41] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Weak |

| Bohn et al. 2012 [42] | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Bouland et al. 2017 [43] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

| Bray et al. 2017 [44] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Breckwoldt, Scholesser & Arntz 2009 [45] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Brinkrolf et al. 2018 [46] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Case et al. 2018 [47] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Weak |

| Chen et al. 2017 [48] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Cheng et al. 1997 [49] | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Cheng-Yu et al. 2016 [50] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Cheskes et al. 2016 [51] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Weak |

| Chew et al. 2009 [52] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Chew et al. 2019 [53] | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Cho et al. 2010 [54] | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Compton et al. 2003 [55] | Strong | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Coons & Guy 2009 [56] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Cu, Phan & O’Leary 2009 [57] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Dami et al. 2010 [58] | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| De Smedt et al. 2018 [59] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak |

| Dobbie et al. 2018 [60] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Dracup et al. 1994 [62] | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Dwyer 2008 [63] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| Enami et al. 2010 [64] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Fratta et al. 2020 [65] | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Han et al. 2018 [66] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Hauff et al. 2003 [67] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Weak |

| Hawkes et al. 2019 [68] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Hollenberg et al. 2019 [69] | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Huang, Hu & Mao 2016 [70] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak |

| Hubble et al. 2003 [71] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Hung et al. 2017 [72] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| Iserbyt 2016 [73] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

| Jelinek et al. 2001 [74] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Johnston et al. 2003 [75] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Kandakai & King 1999 [76] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Kanstad, Nilsen & Fredriksen 2011 [77] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Karuthan et al. 2019 [78] | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Kua et al. 2018 [79] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Kuramoto et al. 2008 [80] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| Lam et al. 2007 [81] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Lee et al. 2013 [82] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| Lerner et al. 2008 [83] | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Moderate |

| Lester, Donnelly & Weston 1997 [84] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Lester, Donnelly & Assar 1997 [85] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Lester, Donnelly & Assar 2000 [86] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Liaw et al. 2020 [87] | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Locke et al. 1995 [88] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Lu et al. 2016 [89] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

| Lynch & Einspruch 2010 [90] | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Maes et al. 2015 [91] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Magid et al. 2019 [92] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

| Mecrow et al. 2015 [96] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Meischke et al. 2002 [97] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Nielsen et al. 2013 [99] | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Nishiyama et al. 2019 [100] | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Nolan et al. 1999 [101] | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Nord et al. 2016 [102] | Strong | Strong | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Moderate |

| Nord et al. 2017 [103] | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong |

| Omi et al. 2008 [104] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Onan et al. 2018 [105] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Parnell et al. 2006 [106] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Pei-Chuan Huang et al. 2019 [107] | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Platz et al. 2000 [108] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

| Rankin et al. 2020 [109] | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Riou et al. 2020 [110] | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Ro et al. 2016 [111] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Rowe et al. 1998 [112] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| Sasaki et al. 2015 [113] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Schmid et al. 2016 [116] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

| Schmitz et al. 2015 [117] | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Schneider et al. 2004 [118] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Shams et al. 2016 [119] | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Shibata et al. 2000 [120] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Sipsma, Stubbs & Plorde 2011 [121] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Skora & Riegel 2001 [122] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Smith et al. 2003 [123] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Sneath & Lacey 2009 [124] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| So et al. 2020 [125] | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Moderate |

| Swor et al. 2006 [20] | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Swor et al. 2013 [126] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Tang et al. 2020 [127] | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Taniguchi, Omi & Inaba 2007 [128] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Taniguchi et al. 2012 [129] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Vaillancourt et al. 2013 [131] | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Vetter et al. 2016 [132] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Wilks et al. 2015 [133] | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak |

| Winkelman et al. 2009 [134] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak |

| Zinckernagel et al. 2016 [135] | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

The psychological and behavioural factors identified from the included studies are reported below and summarised in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 below. Studies were divided into subgroups according to the study population (i.e. results from those with direct experience versus general samples responding to a ‘hypothetical’ OHCA); study design and statistics used. Data were further categorised depending on whether the ‘predictor’ was identified by participants in response to an open question or whether it was presented as a possible factor and subsequently endorsed. Factors are presented in relation to the domains of the Theoretical Domains Framework so that theoretically similar factors are grouped together and can be compared across study designs (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Psychological and behavioural factors associated with LOWER actual/intended CPR initiation (grouped using Theoretical Domains Framework V.2 [29])

| Factor related to reluctance | Participants | Number (total) | Number in analysis for each factor | Unprompted identification of each factor (% of whole sample and % of unwilling subsample) | Endorsement of each factor when prompted (% of whole sample and % of unwilling subsample) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6. Beliefs about Consequences | ||||||

| Concerns about doing something wrong | ||||||

| Aaberg et al. 2014 [32] | High School students | 399 | 399 responding as to their worst fear | NR (1 of 3 qualitative themes identified) | ||

| Compton et al. 2003 [55] | School teachers | 201 | 180 | 71% of untrained | ||

| 42% of trained | ||||||

| Coons & Guy 2009 [56] | Adults (≥18) | 755 | 435 (who endorsed reasons) | 20% (stranger) | ||

| 22.5% (family) | ||||||

| Dwyer 2008 [56] | Adults (≥18) | 1208 | 379 (not confident) | 55% | ||

| Iserbyt 2016 [63] | Secondary school pupils | 313 | 313 | 38% (girls) | ||

| 26% (boys) | ||||||

| Nolan et al. 1999 [101] | Adults (≥45) | 786 | 203 (not ready to perform CPR) | 53% | ||

| Onan et al. 2018 [105] | High School students | 83 | 83 | NR (concern identified) | ||

| Sasson et al. 2013 [114] | Lay-people (min age not stated) | 42 | 42 | NR (1 of 10 qualitative barriers) | ||

| Swor 2006 [20] | Witnesses of OHCA | 684 | 279 (did not perform CPR) | 11% | ||

| Tang et al. 2020 [127] | High school students (senior, age NR) | 397 | 397 | 78% (fail to meet professional standards) | ||

| Zinckernagel et al. 2016 [135] | Secondary school leaders and teachers | 25 | 25 | NR (a qualitative theme identified) | ||

| Concerns about doing harm | ||||||

| Aaberg et al. 2014 [32] | High School students | 399 | 399 responding as to their worst fear | NR (1 of 3 qualitative themes identified) | ||

| Alhussein 2021 [33] | Adults (≥18) | 856 | Those whose source of knowledge was media sources (largest group) (n = 331) | Break rib 22% (family/friend) | ||

| Break rib 21% (stranger) | ||||||

| Organ damage 14% (family/friend) | ||||||

| Organ damage 12% (stranger) | ||||||

| Stopping heart 8% (family/friend) | ||||||

| Stopping heart 5% (stranger) | ||||||

| Anto-Ocra et al. 2020 [35] | Adults (≥18 years) | 277 | 277 | 35% | ||

| Babic et al. 2020 [38] | Adults (≥18 years) | 198 | 198 | 15% (MMV) | ||

| 23% (compressions) | ||||||

| Becker et al. 2019 [39] | Adults (≥18 years) who attended CPR training event | 677 | 306 resp. concerns elderly patient | 63% | ||

| 249 resp. concerns for woman | 21% | |||||

| 291 resp. concerns for child | 51% | |||||

| Cheng-Yu et al. 2016 [50] | Adults (≥20) | 401 | 144 (unwilling to perform on stranger) | 11% | ||

| Compton et al. 2003 [55] | School teachers | 201 | 180 | 64% of untrained | ||

| 41% of trained | ||||||

| Coons & Guy 2009 [56] | Adults (≥18) | 755 | 435 (who endorsed reasons) | 19.4% stranger | ||

| 26.4% (family) | ||||||

| Cu 2009 [50] | Caregivers of children presenting to the Emergency Department (≥18 years) | 348 | 125 (unwilling to perform CPR on adult) | 38% | ||

| Dami 2010 [51] | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 738 | 73 medically appropriate who refused | 3% | ||

| Dobbie 2018 [53] | Adults (≥16 years) | 1027 | 1027 | 22% | ||

| Donohoe 2006 [54] | Adults (≥16 years) | NR | Focus groups (NR) | NR (Qualitative theme identified) | ||

| Dwyer 2008 [56] | Adults (≥18) | 1208 | 379 (not confident) | 10% | ||

| Han 2018 [58] | Family members (≥18 years) of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 203 | 88 | 7% | ||

| Huang 2016 [60] | School and University students (13–21 years) | 1407 | 546 (unwilling to perform on stranger) | 68% | ||

| Hubble 2003 [61] | High school students | 683 | 683 | 25% (MMV) | ||

| 31% (AED) | ||||||

| 25% (CC) | ||||||

| Hung 2017 [62] | College and University students (≥15 years) | 351 | 351 | 26% | ||

| Kandakai & King 1999 [76] | College students | 214 | 214 | 65% | ||

| Kanstad, Nilsen & Fredriksen 2011 [77] | Secondary school students (16–19 years) | 376 | 376 | 17% | ||

| Karuthan et al. 2019 [78] | College students | 393 | 393 | 5% (HO stranger) | ||

| 3% (HO family-member) | ||||||

| Kua et al. 2018 [79] | School students (11–17 years) | 1196 | 966 | 58% | ||

| Liaw et al. 2020 [87] | University employees (non-medical) | 184 | NR | Fear and concern identified as significantly reduced by training in 54% | ||

| Maes et al. 2015 [91]a | Hospital visitors (≥13 years) | 85 | 51 who did not feel able to use AED | 2% | ||

| Omi 2008 [91] | High school students | 3316 | 2203 unwilling to perform CPR | 23% | ||

| Onan et al. 2018 [105] | High School students | 83 | 83 | NR (concern identified) | ||

| Magid et al. 2019 [92] | College students | 588 | 300 (who identified barriers) | 52% | ||

| Pei-Chuan Huang et al. 2019 [107] | Adults (≥20) | 1073 | 141 (who provided reasons why not) | 36.5% | ||

| Platz et al. 2000 [108] | Family members of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 100 | 100 | 49% | ||

| Rankin et al. 2020 [109] | Adults (18–21 years) | 178 | Not CPR trained, for family 76% | |||

| CPR trained, for family 67% | ||||||

| Not CPR trained, for stranger 69% | ||||||

| CPR trained, for stranger 57% | ||||||

| Sasson et al. 2013 [114] | Lay-people (min age not stated) | 42 | 42 | NR (1 of 10 qualitative barriers) | ||

| Schmid et al. 2016 [116] | Laypeople (minimum age not stated) | 370 | 370 | 17.30% | ||

| Shams et al. 2016 [119] | University students | 948 | 948 | 53% | ||

| So et al. 2020 [125] | High school students (12–15 years) | 128 | NR | 94% | ||

| Swor 2006 [20] | Witnesses of OHCA | 684 | 279 (did not perform CPR) | 2% | ||

| Taniguchi 2012 [112] | High school students and teachers | 1946 | 1708 (students on a stranger) | 14% | ||

| Thoren 2010 [113] | Partners of people who experienced OHCA | 15 | 15 | NR (Qualitative theme identified) | ||

| Wilks et al. 2015 [133] | Secondary school students (15–16 years) | 383 | NR | 28% | ||

| Concern about being the cause of the person’s death | ||||||

| Aaberg et al. 2014 [32] | High School students | 399 | 399 responding as to their worst fear | NR (1 of 3 qualitative themes identified) | ||

| Becker et al. 2019 [39] | Adults (≥18 years) who attended CPR training event | 677 | 306 resp. concerns elderly patient | 6% | ||

| 249 resp. concerns for woman | 2% | |||||

| 291 resp. concerns for child | 4% | |||||

| Nolan et al. 1999 [101] | Adults (≥45) | 786 | 203 (not ready to perform CPR) | 40% | ||

| Onan et al. 2018 [105] | High School students | 83 | 83 | NR (concern identified) | ||

| Tang et al. 2020 [127] | High school students (senior, age NR) | 397 | 397 | 9% (fear of treating dying person) | ||

| Belief CPR futile | ||||||

| Axelsson et al. 1996 [36] | People who reported making a CPR attempt between 1990 and 1994 | 742 | 51 bystanders described hesitation | NR | ||

| Case et al. 2018 [47] | OHCA Calls | 120 | 120 calls where no CPR given | 28% | ||

| Hauff 2003 [59] | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 404 | 52 who did not accept CPR instructions | 23% | ||

| Nolan et al. 1999 [101] | Adults (≥45) | 786 | 203 (not ready to perform CPR) | 34% | ||

| Riou et al. 2020 [110] | Retrospective analysis of emergency calls for OHCA | 65 | 57 (where caller responded with an account) | 50% expressed an ‘epistemic’ account – i.e. too late or futile | ||

| Skora & Riegel 2001 [122] | Previously performed CPR | 12 | 12 participants | NR (Qualitative theme identified) | ||

| Swor 2006 [20] | Witnesses of OHCA | 684 | 279 (did not perform CPR) | 4% | ||

| Belief CPR does not work | ||||||

| Babic et al. 2020 [38] | Adults (≥18 years) | 198 | 198 | 0.5% (MMV) | ||

| 1% (compressions) | ||||||

| Schmid et al. 2016 [116] | Laypeople (minimum age not stated) | 370 | 370 | 10% | ||

| Shams et al. 2016 [119] | University students | 948 | 948 | 9% | ||

| Violates beliefs about death | ||||||

| Hubble 2003 [61] | High school students | 683 | 683 | 4% (MMV) | ||

| 4% (AED) | ||||||

| 4% (CC) | ||||||

| Schmid et al. 2016 [116] | Laypeople (minimum age not stated) | 370 | 370 | 5% | ||

| Concerns about MMV | ||||||

| Anto-Ocra et al. 2020 [35] | Adults (≥18 years) | 277 | 277 | 5% | ||

| Axelsson et al. 1996 [36] | People who reported making a CPR attempt between 1990 and 1994 | 742 | 51 bystanders described hesitation | NR | ||

| Cheng-Yu et al. 2016 [50] | Adults (≥20) | 401 | 144 (unwilling to perform on stranger) | 46% | ||

| Cho et al. 2010 [54] | Lay people aged 11 years and over | 890 | 539 (unwilling to perform CPR) | 17% | ||

| Coons & Guy 2009 [56] | Adults (≥18) | 755 | 435 (who endorsed reasons) | 19% (stranger) | ||

| 16.5% (family) | ||||||

| Dobbie 2018 [53] | Adults (≥16 years) | 1027 | 1027 | 7% | ||

| Donohoe 2006 [54] | Adults (≥16 years) | NR | Focus groups (NR) | NR (Qualitative theme identified) | ||

| Iserbyt 2016 [63] | Secondary school pupils | 313 | 313 | 19% (girls) | ||

| 10% (boys) | ||||||

| Pei-Chuan Huang et al. 2019 [107] | Adults (≥20) | 1073 | 141 (who provided reasons why not) | 13% | ||

| Sasson et al. 2013 [114] | Lay-people (min age not stated) | 42 | 42 | NR (1 of 10 qualitative barriers identified) | ||

| Schmid et al. 2016 [116] | Laypeople (minimum age not stated) | 370 | 370 | 18% | ||

| Shams et al. 2016 [119] | University students | 948 | 948 | 19% | ||

| Swor 2006 [20] | Witnesses of OHCA | 684 | 279 (did not perform CPR) | 1% | ||

| Concern about legal ramifications | ||||||

| Alhussein 2021 [33] | Adults (≥18) | 856 | Those whose source of knowledge was media sources (largest group) (n = 331) | 5% (family/friend) | ||

| 22% (stranger) | ||||||

| Alshudukhi et al. 2018 [34] | Adults (≥18) | 310 | 168 unwilling to perform CPR | 2% | ||

| Anto-Ocra et al. 2020 [35] | Adults (≥18 years) | 277 | 277 | 8% | ||

| Chen et al. 2017 [48] | Adult laypersons (≥18 yrs) + 3 < 18 years | 1841 | 1841 | 53% | ||

| Cheng-Yu et al. 2016 [50] | Adults (≥20) | 401 | 144 (unwilling to perform on stranger) | 37% | ||

| Cho et al. 2010 [54] | Lay people aged 11 years and over | 890 | 539 (unwilling to perform CPR) | 55% | ||

| Compton et al. 2003 [55] | School teachers | 201 | 180 | 52% of untrained | ||

| 54% of trained | ||||||

| Coons & Guy 2009 [56] | Adults (≥18) | 755 | 435 (who endorsed reasons) | 20.9% (stranger) | ||

| 12.1% (family) | ||||||

| Dobbie 2018 [53] | Adults (≥16 years) | 1027 | 1027 | 8% | ||

| Donohoe 2006 [54] | Adults (≥16 years) | NR | Focus groups (NR) | NR (Qualitative theme identified) | ||

| Huang 2016 [60] | School and University students (13–21 years) | 1407 | 546 (unwilling to perform on stranger) | 91% | ||

| Hubble 2003 [61] | High school students | 683 | NR | 16% (MMV) | ||

| 17% (AED) | ||||||

| 13% (CC) | ||||||

| Hung 2017 [62] | College and University students (≥15 years) | 351 | 351 | 17% | ||

| Iserbyt 2016 [63] | Secondary school pupils | 313 | 313 | 4% (girls) | ||

| 6% (boys) | ||||||

| Jelinek 2001 [64] | General public (age not reported) | 803 | 84 unwilling to perform MMV | 4% | ||

| 26 unwilling to perform CC | 19% | |||||

| Johnston 2003 [65] | Adults (≥18 years) | 4490 | 4490 | 2% | ||

| Kandakai & King 1999 [76] | College students | 214 | 214 | 48% | ||

| Karuthan et al. 2019 [78] | College students | 393 | 393 | 1% (HO stranger) | ||

| 1% (HO family-member) | ||||||

| Lerner et al. 2008 [83] | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 168 | 145 who did not follow CPR instructions | 1% | ||

| Liaw et al. 2020 [87] | University employees (non-medical) | 184 | NR | Fear and concern identified as significantly reduced by training in 59% | ||

| Lu et al. 2016 [89] | College students | 609 | 609 (non-medical) | 7–21% (dep on subject) | ||

| Nolan et al. 1999 [101] | Adults (≥45) | 786 | 203 (not ready to perform CPR) | 38% | ||

| Pei-Chuan Huang et al. 2019 [107] | Adults (≥20) | 1073 | 141 (who provided reasons why not) | 44% | ||

| Rankin et al. 2020 [109] | Adults (18–21 years) | 178 | Not CPR trained, for family 32% | |||

| CPR trained, for family 26% | ||||||

| Not CPR trained, for stranger 60% | ||||||

| CPR trained, for stranger 75% | ||||||

| Sasson et al. 2013 [114] | Lay-people (min age not stated) | 42 | 42 | NR (1 of 10 qualitative barriers identified) | ||

| Sasson et al. 2015 [115] | Lay-people (≥13) | 64 | 64 | NR (qualitative barrier identified) | ||

| Schmid et al. 2016 [116] | Laypeople (minimum age not stated) | 370 | 370 | 30% | ||

| Shams et al. 2016 [119] | University students | 948 | 948 | 25% | ||

| So et al. 2020 [125] | High school students (12–15 years) | 128 | NR | 52% | ||

| Tang et al. 2020 [127] | High school students (senior, age NR) | 397 | 397 | 67% | ||

| Wilks et al. 2015 [133] | Secondary school students (15–16 years) | 383 | NR | 14% | ||

| Winkelman et al. 2009 [134] | Teacher candidates | 582 | 47 | 17% | ||

| Concerns about risk to self | ||||||

| Becker et al. 2019 [39] | Adults (≥18 years) who attended CPR training event | 677 | 306 resp. concerns elderly patient | 2% | ||

| 249 resp. concerns for woman | 2% | |||||

| 291 resp. concerns for child | 1% | |||||

| Cu 2009 [50] | Caregivers of children presenting to the Emergency Department (≥18 years) | 348 | 125 (unwilling to perform CPR on adult) | 3% | ||

| Hubble 2003 [61] | High school students | 683 | NR | 7% (MMV) | ||

| 10% (AED) | ||||||

| 6% (CC) | ||||||

| Jelinek 2001 [64] | General public (age not reported) | 803 | 84 unwilling to perform MMV | 56% | ||

| Johnston 2003 [65] | Adults (≥18 years) | 4490 | 4490 | 4.50% | ||

| Lester, Donnelly & Weston 1997 [84] | First year high school pupils | 233 | 233 | 11% | ||

| Liaw et al. 2020 [87] | University employees (non-medical) | 184 | NR | Fear and concern identified as significantly reduced by training in 34% | ||

| Mathiesen et al. 2017 [93] | Witnesses of OHCA | 10 | 10 | NR (qualitative barrier identified) | ||

| Sasson et al. 2013 [114] | Lay-people (min age not stated) | 42 | 42 | NR (1 of 10 qualitative barriers) | ||

| Sasson et al. 2015 [115] | Lay-people (≥13) | 64 | 64 | NR (qualitative barrier identified) | ||

| Concerns about risk of infection | ||||||

| Alhussein 2021 [33] | Adults (≥18) | 856 | Those whose source of knowledge was media sources (largest group) (n = 331) | 2% (family/friend) | ||

| 5% (stranger) | ||||||

| Anto-Ocra et al. 2020 [35] | Adults (≥18 years) | 277 | 277 | 18% | ||

| Axelsson et al. 2000 [37] | Adults (≥18 years) who had received training in basic CPR in January 1997. | 1012 | 1012 | 8% | ||

| Babic et al. 2020 [38] | Adults (≥18 years) | 198 | 198 | 15% (MMV) | ||

| 0.5% (compressions) | ||||||

| Chen et al. 2017 [48] | Adult laypersons (≥18 yrs) + 3 < 18 years | 1841 | 1841 | 2% | ||

| Cheskes et al. 2016 [51] | Adult (≥18 yrs) | 428 | NR | 24% | ||

| Cho et al. 2010 [54] | Lay people aged 11 years and over | 890 | 539 (unwilling to perform CPR) | 10% | ||

| Compton et al. 2003 [55] | School teachers | 201 | 180 | 50% of untrained | ||

| 58% of trained | ||||||

| Dami 2010 [51] | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 738 | 73 medically appropriate who refused | 4% | ||

| Dobbie 2018 [53] | Adults (≥16 years) | 1027 | 1027 | 10% | ||

| Donohoe 2006 [54] | Adults (≥16 years) | NR | Focus groups (n NR) | NR (Qualitative theme identified) | ||

| Dwyer 2008 [56] | Adults (≥18) | 1208 | 379 (not confident) | 1% | ||

| Han 2018 [58] | Family members (≥18 years) of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 203 | 88 | 1% | ||

| Huang 2016 [60] | School and University students (13–21 years) | 1407 | 546 (unwilling to perform on stranger) | 24% | ||

| Hubble 2003 [61] | High school students | 683 | NR | 35% (MMV) | ||

| 11% (AED) | ||||||

| 12% (CC) | ||||||

| Hung 2017 [62] | College and University students (≥15 years) | 351 | 351 | 8% | ||

| Iserbyt 2016 [63] | Secondary school pupils | 313 | 313 | 10% (girls) | ||

| 11% (boys) | ||||||

| Jelinek 2001 [64] | General public (age not reported) | 803 | 84 unwilling to perform MMV | 19% (MMV) | ||

| Johnston 2003 [65] | Adults (≥18 years) | 4490 | 4490 | 18% | ||

| Kanstad, Nilsen & Fredriksen 2011 [77] | Secondary school students (16–19 years) | 376 | 376 | 6% | ||

| Karuthan et al. 2019 [78] | College students | 393 | 393 | 3% (HO stranger) | ||

| 1% (HO family-member) | ||||||

| Lee et al. 2013 [82] | College students | 2029 | 242 (unwilling to perform CPR) | < 1% | ||

| Lester, Donnelly & Weston 1997 [84] | First year high school pupils | 233 | 233 | 12% (7% HIV, 5% other) | ||

| Lester, Donnelly & Assar 1997 [85] | General public | 241 | 241 | 8% (5% HIV, 3% other) | ||

| Liaw et al. 2020 [87] | University employees (non-medical) | 184 | NR | Fear and concern identified as significantly reduced by training in 34% | ||

| Lu et al. 2016 [89] | College students | 609 | 609 (non-medical) | 10–45% (dep on subject) | ||

| Nolan et al. 1999 [101] | Adults (≥45) | 786 | 203 (not ready to perform CPR) | 36% | ||

| Omi 2008 [91] | High school students | 3316 | 2203 unwilling to perform CPR | 11% (of 2203 who were unwilling) | ||

| Pei-Chuan Huang et al. 2019 [107] | Adults (≥20) | 1073 | 141 (who provided reasons why not) | 28% | ||

| Platz et al. 2000 [108] | Family members of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 100 | 100 | 9% | ||

| Rankin et al. 2020 [109] | Adults (18–21 years) | 178 | Not CPR trained, for family 6% | |||

| CPR trained, for family 15% | ||||||

| Not CPR trained, for stranger 32% | ||||||

| CPR trained, for stranger 44% | ||||||

| Shams et al. 2016 [119] | University students | 948 | 948 | 33% | ||

| Shibata 2000 [105] | Schoolchildren and teachers | 626 | NR | 5% | ||

| So et al. 2020 [125] | High school students (12–15 years) | 128 | NR | 28% | ||

| Skora & Riegel 2001 [122] | Previously performed CPR | 12 | 12 participants | 8% | ||

| Tang et al. 2020 [127] | High school students (senior, age NR) | 397 | 397 | 23% | ||

| Taniguchi 2007 [111] | High school students and teachers | 3444 | 3444 | 10% | ||

| Taniguchi 2012 [112] | High school students and teachers | 1946 | 1708 students on a stranger | 7% | ||

| Wilks et al. 2015 [133] | Secondary school students (15–16 years) | 383 | NR | 6% | ||

| Winkelman et al. 2009 [134] | Teacher candidates | 582 | 47 | 30% | ||

| Delaying CPR won’t do harm | ||||||

| Magid et al. 2019 [92] | College students | 588 | 300 (who identified barriers) | 3.5% | ||

| Concerns about substance use | ||||||

| Drugs | ||||||

| Dobbie 2018 [53] | Adult (> 16) | 1027 | 1027 | 16% | ||

| Johnston 2003 [65] | Adults (≥18 years) | 4490 | 4490 | 2% | ||

| Alcohol | ||||||

| Dobbie 2018 [53] | Adults (≥16 years) | 1027 | 1027 | |||

| Johnston 2003 [65] | Adults (≥18 years) | 4490 | 4490 | 2% | 10% | |

| 4. Beliefs about capabilities | ||||||

| Concerns about capability (general) | ||||||

| Alhussein 2021 [33] | Adults (≥18) | 856 | Those whose source of knowledge was media sources (largest group) (n = 331) | 84% (family/friend) | ||

| 83% (stranger) | ||||||

| Alshudukhi et al. 2018 [34] | Adults (≥18) | 310 | 168 unwilling to perform CPR | 61% | ||

| Anto-Ocra et al. 2020 [35] | Adults (≥18 years) | 277 | 277 | 61% | ||

| Babic et al. 2020 [38] | Adults (≥18 years) | 198 | 198 | 37% (MMV) | ||

| 32% (compressions) | ||||||

| Becker et al. 2019 [39] | Adults (≥18 years) who attended CPR training event | 677 | 306 resp. concerns elderly patient | 13% | ||

| 249 resp. concerns for woman | 14% | |||||

| 291 resp. concerns for child | 23% | |||||

| Chen et al. 2017 [48] | Adult laypersons (≥18 yrs) + 3 < 18 years | 1841 | 1841 | 44% | ||

| Cheng-Yu et al. 2016 [50] | Adults (≥20) | 401 | 144 (unwilling to perform on stranger) | 6% | ||

| Cho et al. 2010 [54] | Lay people aged 11 years and over | 890 | 539 (unwilling to perform CPR) | 50% | ||

| Cu 2009 [50] | Caregivers of children presenting to the Emergency Department (≥18 years) | 348 | 125 (unwilling to perform CPR on adult) | 77% | ||

| Dobbie 2018 [53] | Adults (≥16 years) | 1027 | 1027 | 19% | ||

| Huang 2016 [60] | School and University students (13–21 years) | 1407 | 546 (unwilling to perform on stranger) | 53% | ||

| Iserbyt 2016 [63] | Secondary school pupils | 313 | 313 | 31% (girls) | ||

| 23% (boys) | ||||||

| Johnston 2003 [65] | Adults (≥18 years) | 4490 | 4490 | 2% | ||

| Karuthan et al. 2019 [78] | College students | 393 | 393 | 36% (HO stranger) | ||

| 27% (HO family-member) | ||||||

| Kanstad, Nilsen & Fredriksen 2011 [77] | Secondary school students (16–19 years) | 376 | 376 | 79% | ||

| Maes et al. 2015 [91]a | Hospital visitors (≥13 years) | 85 | 51 who did not feel able to use AED | 45% (Don’t know how AED works) | ||

| Nielsen et al. 2013 [99] | Adults (≥15 years) | 1639 | n = 114 (unwilling to provide CC, 2008) | 54% | ||

| n = 94 (unwilling to provide MMV, 2008) | 44% | |||||

| n = 89 (unwilling to provide CC, 2009) | 48% | |||||

| n = 90 (unwilling to provide MMV, 2009) | 35% | |||||

| Omi 2008 [91] | High school students | 3316 | 2203 unwilling to perform CPR | 55% (of 2203 who were unwilling) | ||

| Pei-Chuan Huang et al. 2019 [107] | Adults (≥20) | 1073 | 141 (who provided reasons why not) | 12% | ||

| Platz et al. 2000 [108] | Family members of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 100 | 100 | 35% | ||

| Rankin et al. 2020 [109] | Adults (18–21 years) | 178 | Not CPR trained, for family 65% | |||

| CPR trained, for family 68% | ||||||

| Not CPR trained, for stranger 58% | ||||||

| CPR trained, for stranger 57% | ||||||

| Shams et al. 2016 [119] | University students | 948 | 948 | 56% | ||

| Shibata 2000 [105] | Schoolchildren and teachers | 626 | NR | 80% | ||

| Sipsma, Stubbs & Plorde 2011 [121] | Adults (≥18) | 1001 | 333 | 33% | ||

| Taniguchi 2007 [111] | High school students and teachers | 3444 | 3444 | 70% | ||

| Taniguchi 2012 [112] | High school students and teachers | 1946 | 1708 students on a stranger | 67% | ||

| Winkelman et al. 2009 [134] | Teacher candidates | 582 | 47 | 38% | ||

| Concerns about physical capability | ||||||

| Case et al. 2018 [47] | OHCA Calls | 120 | 120 calls where no CPR given | 15% | ||

| Coons & Guy 2009 [56] | Adults (≥18) | 755 | 435 (who endorsed reasons) | 21.5% (stranger) | ||

| 22.5% (family) | ||||||

| Dami 2010 [51] | High school students | 3316 | 2203 unwilling to perform CPR | 55% (of 2203 who were unwilling) | ||

| Hauff 2003 [59] | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 404 | 52 who did not accept CPR instructions | 11% | ||

| Jelinek 2001 [64] | General public (age not reported) | 803 | 26 unwilling to perform CC | 11% | ||

| Lerner et al. 2008 [83] | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 168 | 145 who did not follow CPR instructions | 8% | ||

| Lu et al. 2016 [89] | College students | 609 | 609 (non-medical) | 1–3% (dep on subject) | ||

| Pei-Chuan Huang et al. 2019 [107] | Adults (≥20) | 1073 | 141 (who provided reasons why not) | 1.3% | ||

| Platz et al. 2000 [108] | Family members of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 100 | 100 | 14% | ||

| Riou et al. 2020 [110] | Retrospective analysis of emergency calls for OHCA | 65 | 57 (where caller responded with an account) | 35% | ||

| Schneider et al. 2004 [118]a | Survivors of OHCA and people who know them | 112 | 112 | 4–5% | ||

| Sipsma, Stubbs & Plorde 2011 [121] | Adults (≥18) | 1001 | 333 | 8% | ||

| Swor 2006 [20] | Witnesses of OHCA | 684 | 279 (did not perform CPR) | 4% | ||

| Winkelman et al. 2009 [134] | Teacher candidates | 582 | 47 | 2% | ||

| Lack of confidence | ||||||

| Anto-Ocra et al. 2020 [35] | Adults (≥18 years) | 277 | 277 | 16% | ||

| Case et al. 2018 [47] | OHCA Calls | 120 | 120 calls where no CPR given | “many” | ||

| Cheskes et al. 2016 [51] | Adult (≥18 yrs) | 428 | NR | 6–12% | ||

| Dobbie 2018 [53] | Adults (≥16 years) | 1027 | 1027 | 15% | ||

| Hung 2017 [62] | College and University students (≥15 years) | 351 | 351 | 48% | ||

| Jelinek 2001 [64] | General public (age not reported) | 803 | 26 unwilling to perform CC | 4% | ||

| Lu et al. 2016 [89] | College students | 609 | 609 (non-medical) | 12–40% (dep on subject) | ||

| Magid et al. 2019 [92] | College students | 588 | 300 (who identified barriers) | 61% | ||

| Teachers | 383 | NR | 49% | |||

| Sasson et al. 2013 [114] | Teachers | 383 | NR | 49% | ||

| Nishiyama et al. 2019 [100] | University students who had witnessed OHCA | 5549 | 94 (who did not perform CPR) | 10% | ||

| So et al. 2020 [125] | High school students (12–15 years) | 128 | NR | 91% | ||

| Wilks et al. 2015 [133] | Secondary school students (15–16 years) | 383 | NR | 27% | ||

| Uncertainty whether cardiac arrest | ||||||

| Axelsson et al. 1996 [36] | People who reported making a CPR attempt between 1990 and 1994 | 742 | 51 bystanders described hesitation | NR | ||

| Breckwoldt et al. 2009 [45] | Witnesses of OHCA | 138 | 39 where agonal breathing | 39% | ||

| Case et al. 2018 [47] | OHCA Calls | 120 | 120 calls where no CPR given | 28% | ||

| Dobbie 2018 [53] | Adults (≥16 years) | 1027 | 1027 | 14% | ||

| Hauff 2003 [59] | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 404 | 52 who did not accept CPR instructions | 6% | ||

| Han 2018 [58] | Family members (≥18 years) of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 203 | 88 | 10% | ||

| Lee et al. 2013 [82] | College students | 2029 | 242 (unwilling to perform CPR) | 34% | ||

| Magid et al. 2019 [92] | College students | 588 | 300 (who identified barriers) | 40% | ||

| Mathiesen et al. 2017 [93] | Witnesses of OHCA | 10 | 10 | NR (qualitative barrier identified) | ||

| Mausz, Snobelen & Tavares 2018 [94] | Witnesses of OHCA | 14 | 15 | NR (qualitative barrier identified) | ||

| Nishiyama et al. 2019 [100] | University students who had witnessed OHCA | 5549 | 94 (who did not perform CPR) | 12% | ||

| Nolan et al. 1999 [101] | Adults (≥45) | 786 | 203 (not ready to perform CPR) | 34% | ||

| Platz et al. 2000 [108] | Family members of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 100 | 100 | 34% | ||

| Sasson et al. 2013 [114] | Lay-people (min age not stated) | 42 | 42 | NR (1 of 10 qualitative barriers identified) | ||

| Sasson et al. 2015 [115] | Lay-people (≥13) | 64 | 64 | NR (qualitative barrier identified) | ||

| Swor et al. 2013 [126]a | Witnesses of OHCA | 30 | 30 | 10% (seizures/agonal breathing) | ||

| Feeling unprepared | ||||||

| Mausz, Snobelen & Tavares 2018 [94] | Witnesses of OHCA | 14 | 15 | NR (qualitative barrier identified) | ||

| Moller et al. 2014 [98] | Witnesses of OHCA | 33 | 33 | NR (qualitative barrier identified) | ||

| 13. Emotion | ||||||

| Strong emotions | ||||||

| Aaberg et al. 2014 [32] | High School students | 399 | 399 responding as to their worst fear | NR (1 of 3 qualitative themes identified) | ||

| Bohn et al. 2012 [42] | Grammar school pupils (age 10 and age 13) | 280 | 144 (training group) | 25% | ||

| Case et al. 2018 [47] | OHCA calls | 120 | 120 calls where no CPR given | 20% | ||

| Dami 2010 [51] | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 738 | 73 medically appropriate who refused | 42% | ||

| Hauff 2003 [59] | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 404 | 52 who did not accept CPR instructions | 11% | ||

| Iserbyt 2016 [63] | Secondary school pupils | 313 | 313 | 19% (girls) | ||

| 13% (boys) | ||||||

| Kandakai & King 1999 [76] | College students | 214 | 214 | 61% | ||

| Lerner et al. 2008 [83] | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 168 | 145 who did not follow CPR instructions | 14% | ||

| Maes et al. 2015 [91]a | Hospital visitors (≥13 years) | 85 | 51 who did not feel able to use AED | 4% | ||

| Mausz, Snobelen & Tavares 2018 [94] | Witnesses of OHCA | 14 | 15 | NR (qualitative barrier identified) | ||

| Nishiyama et al. 2019 [100] | University students who had witnessed OHCA | 5549 | 94 (who did not perform CPR) | 14% | ||

| Platz et al. 2000 [108] | Family members of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 100 | 100 | 13% | ||

| Riou et al. 2020 [110] | Retrospective analysis of emergency calls for OHCA | 65 | 2 | NR (being ‘shaken’ and fear expressed in 2 example quotations) | ||

| Skora & Riegel 2001 [122] | Laypersons who had provided out-of-hospital CPR to strangers | 12 | 12 participants | NR (Qualitative theme identified) Fear and anxiety | ||

| Swor 2006 [20] | Witnesses of OHCA | 684 | 279 (did not perform CPR) | 39% | ||

| Thoren 2010 [113] | Partners of people who experienced OHCA | 15 | 15 | NR (Qualitative theme identified) | ||

| Winkelman et al. 2009 [134] | Teacher candidates | 582 | 47 | 13% | ||

| Embarrassed | ||||||

| Lu et al. 2016 [89] | College students | 609 | 609 (non-medical) | 4–32% (dep on subject) | ||

| 12. Social influences | ||||||

| Reluctance to take responsibility / get involved | ||||||

| Lu et al. 2016 [89] | College students | 609 | 609 (non-medical) | 3–64% (dep on subject) | ||

| Nishiyama et al. 2019 [100] | University students who had witnessed OHCA | 5549 | 94 (who did not perform CPR) | 6% | ||

| Sasson et al. 2013 [114] | Lay-people (min age not stated) | 42 | 42 | NR (1 of 10 qualitative barriers identified) | ||

| Wait for someone else to step forward | ||||||

| Johnston 2003 [65] | Adults (≥18 years) | 4490 | 4490 | 2% | ||

| Magid et al. 2019 [92] | College students | 588 | 300 (who identified barriers) | 20% | ||

| Believe should wait for health professional | ||||||

| Huang 2016 [60] | School and University students (13–21 years) | 1407 | 546 (unwilling to perform on stranger) | 7% | ||

| Kua et al. 2018 [79] | School students (11–17 years) | 1196 | 966 | 28% | ||

| Pei-Chuan Huang et al. 2019 [107] | Adults (≥20) | 1073 | 141 (who provided reasons why not) | 3.5% | ||

| Tang et al. 2020 [127] | High school students (senior, age NR) | 397 | 397 | 33% | ||

| Perceptions about what others would do? | ||||||

| Sasson et al. 2013 [114] | Lay-people (min age not stated) | 42 | 42 | NR (1 of 10 qualitative barriers identified) | ||

| Modesty concerns | ||||||

| Becker et al. 2019 [39] | Adults (≥18 years) who attended CPR training event | 677 | 249 resp. concerns for woman | 14% | ||

| Shams et al. 2016 [119] | College students | 948 | 948 | 18% chest exposure | ||

| 10% touching opposite gender | ||||||

| Reluctance to touch a stranger | ||||||

| Babic et al. 2020 [38] | Adults (≥18 years) | 198 | 198 | 10% (MMV) | ||

| 5% (compressions) | ||||||

| Becker et al. 2019 [39] | Adults (≥18 years) who attended CPR training event | 677 | 306 resp. concerns elderly patient | 2% (or blame) | ||

| 249 resp. concerns for woman | 6% (or be accused) | |||||

| 291 resp. concerns for child | 5% (blame) | |||||

| 11. Environmental context | ||||||

| Disagreeable characteristics | ||||||

| General | ||||||

| Axelsson et al. 1996 [36] | People who reported making a CPR attempt between 1990 and 1994 | 742 | 51 bystanders described hesitation | NR | ||

| Dobbie 2018 [53] | Adults (≥16 years) | 1027 | 1027 | 19% | ||

| Hauff 2003 [59] | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 404 | 52 who did not accept CPR instructions | 2% | ||

| Lerner et al. 2008 [83] | Call to Dispatch Centre with OHCA | 168 | 145 who did not follow CPR instructions | 3% | ||

| Shams et al. 2016 [119] | University students | 948 | 948 | 30% | ||

| Blood | ||||||

| Johnston 2003 [65] | Adults (≥18 years) | 4490 | 4490 | 12% | ||

| Lester, Donnelly & Weston 1997 [84] | First year high school pupils | 233 | 233 | 23% | ||

| Lester, Donnelly & Assar 1997 [85] | General public | 241 | 241 | 5% | ||

| Cu 2009 [50] | Caregivers of children presenting to the Emergency Department (≥18 years) | 348 | 125 (unwilling to perform CPR on adult) | 10% | ||

| Kandakai & King 1999 [76] | College students | 214 | 214 | 88% | ||

| Skora & Riegel 2001 [122] | Previously performed CPR | 12 | 12 participants | NR (Qualitative theme identified) | ||

| Dirty | ||||||

| Dobbie 2018 [53] | Adults (≥16 years) | 1027 | 1027 | 5% | ||

| Johnston 2003 [65] | Adults (≥18 years) | 4490 | 4490 | 11% | ||

| Vomit | ||||||

| Johnston 2003 [65] | Adults (≥18 years) | 4490 | 4490 | 3% | ||

| Kandakai & King 1999 [76] | College students | 214 | 214 | 81% | ||

| Nolan et al. 1999 [101] | Adults (≥45) | 786 | 203 (not ready to perform CPR) | 38% | ||

| Skora & Riegel 2001 [122] | Previously performed CPR | 12 | 12 participants | NR (Qualitative theme identified) momentary hesitation | ||

| Saliva | ||||||

| Kandakai & King 1999 [76] | College students | 214 | 214 | 54% | ||

Table 4.

Psychological and behavioural factors associated with GREATER actual/intended CPR initiation (grouped by Theoretical Domains Framework V.2 [29])

| Factors related to initiation of CPR | Participants | Number (total) | Number in analysis for this factor | Unprompted identification of each factor (% of whole sample and % of unwilling subsample) |

Endorsement of each factor when prompted (% of whole sample and % of unwilling subsample) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3. Social role and identity | |||||

| Instinct for saving others | |||||

| Huang 2016 [70] | School and University students (13–21 years) | 1407 | 807 (willing to perform on stranger) | 89% | |

| Sense of personal responsibility/duty | |||||

| Huang 2016 [70] | School and University students (13–21 years) | 1407 | 807 (willing to perform on stranger) | 64% | |

| Kua et al. 2018 [79] | School students (11–17 years) | 1196 | 966 | 34% | |

| Mathiesen 2017 [93] | Witness of OHCA | 10 | 10 | NR (Qualitative theme identified - normative obligation) | |

| Skora 2001 [122] | Previously performed CPR | 12 | 12 | NR (Qualitative themes identified – Duty & Responsibility, Guilt and Social pressure, Altruism) | |

| Wilks 2015 [133] | Secondary school students (15–16 years) | 383 | NR | NR | |

| 6. Beliefs about Consequences | |||||

| Anticipate guilt if don’t act | |||||

| Mathiesen 2017 [93] | Witness of OHCA | 10 | 10 | NR (Qualitative theme identified) | |

| Believe more likely to help than harm | |||||

| Hung 2017 [72] | College and University students (≥15 years) | 351 | 351 | 79% | |

| Kua et al. 2018 [79] | School students (11–17 years) | 1196 | 966 | 12% | |

| Pei-Chuan Huang 2019 [107] | Adults (≥20 years) | 1073 | 1073 | 85% | |

| Person will die if I don’t | |||||

| Johnston 2003 [75] | Adults (≥18 years) | 4490 | 4490 | 6% | |

| Believe CPR increases survival | |||||

| Hung 2017 [72] | College and University students (≥15 years) | 351 | 351 | 79% | |

| Wilks 2015 [133] | Secondary school students (15–16 years) | 383 | NR | NR | |

| Know risk of permanent brain damage if don’t act | |||||

| Pei-Chuan Huang 2019 [107] | Adults (≥20 years) | 1073 | 1073 | 79% | |

| Johnston 2003 [75] | Adults (≥18 years) | 4490 | 4490 | 6% | |

| Kua 2018 [79] | School students (11–17 years) | 1196 | 966 | 37% | |

| Awareness of legal protection (e.g.Good Samaritan Law) | |||||

| Pei-Chuan Huang 2019 [107] | Adults (≥20 years) | 1073 | 1073 | 85% | |

| 12. Social influences | |||||

| Make every effort even if no hope | |||||

| Huang 2016 [70] | School and University students (13–21 years) | 1407 | 807 (willing to perform on stranger) | 13% | |

| Belief that life is precious | |||||

| Hung 2017 [72] | College and University students (≥15 years) | 351 | 351 | 49% | |

| Mathiesen 2017 [93] | Witness of OHCA | 10 | 10 | NR (Qualitative theme identified) | |

Table 5.

Studies which formally assess association of variables with measures of CPR initiation/intention (grouped by Theoretical Domains Framework V.2 [29])

| Factor associated with CPR initiation | Population (Number, Country, Age Group) | Measure of CPR intention | Variable associated with CPR initiation | Odds ratio (95% CI) (unless indicated otherwise) | |

| 1. Knowledge | |||||

| Knowing importance of CPR | |||||

| Kuramoto 2008 [80] | 1132 Japan Adults (≥15 years) | Willingness to attempt CPR | 1.9 (1.3–2.8) | ||

| 11. Environmental context | |||||

| Having friends with heart diseases | |||||

| Kuramoto 2008 [80] | 1132 Japan Adults (≥15 years) | Willingness to attempt CPR | 1.8 (1.1–3.0) | ||

| Self-rated health status | |||||

| Ro et al. 2016 [111] | 62,425 Korea ≥19 years | Provision of bystander CPR (CPR self-efficacy) | Good self-rated health status | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | |

| 2. Skills | |||||

| Previous experience of CPR | |||||

| Chew et al. 2019 [53] | 6248 Malaysian Adults (min age NR) | Willingness to perform CPR | Previous experience of administering CPR | Mean rank =2877.42, U = 1,205,596, p < 0.001 | |

| Hawkes et al. 2019 [68] | 2084 UK Adults (≥18 years) | Likelihood of performing CPR | Having witnessed OHCA previously | 1.53 (1.17–2.10) | |

| Kuramoto 2008 [80] | 1132 Japan Adults (≥15 years) | Willingness to attempt CPR | Actual experience with CPR | 3.8 (1.7–8.) | |

| Sasaki et al. 2015 [113] | 4853 Japan adults (≥15 years) | Confidence in performing CPR | Previous experience performing CPR | CC: 4.8 (1.8–12.9) | |

| MMV: 3.7 (2.1–6.6) | |||||

| AED: 2.7 (1.3–5.7) | |||||

| Schmid et al. 2016 [116] | 371 Costa Rica age unknown | Willingness to perform CPR on a stranger | Prior witness OHCA | 2.5 (1.2–5.3) | |

| 6. Beliefs about Consequences | |||||

| Believe legal consequences if person dies | |||||

| Schmid et al. 2016 [116] | 371 Costa Rica age unknown | Willingness to perform CPR on a stranger | Belief that CPR has legal consequences | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | |

| Hesitancy about mouth to mouth | |||||

| Schmid et al. 2016 [116] | 371 Costa Rica age unknown | Willingness to perform CPR on a stranger | Hesitancy to do MMV | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | |

| Outcome expectancies | |||||

| Meischke et al. 2002 [97] | 159 USA older adults | Intentions to use an AED | Outcome expectancies | 4.65 (2.0–10.6) | |

| Attitudes | |||||

| Vaillancourt et al. 2013 [131] | 192 Canada Adults (≥55 years) | Intention to perform CPR | Attitude | 1.6 (1.3–2.0) | |

| Magid et al. 2019 [92] | 588 USA College students | Intention to perform CPR | Attitude | Beta (95%CI): 0.164 [0.131, 0.197] | |

| 4. Beliefs about capabilities | |||||

| Feeling confident in ability to perform CPR | |||||

| Shams et al. 2016 [119] | 948, Lebanon, university students | Willingness to perform CPR | Feeling confident in abilities | 1.9 (1.3–2.9) | |

| Feel lack expertise | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | ||||

| Meischke et al. 2002 [97] | 159 USA older adults | Intentions to use an AED | Self-perceived ability | 11.5 (3.8–34.4) | |

| Vaillancourt et al. 2013 [131] | 192 Canada Adults (≥55 years) | Intention to perform CPR | Control | 1.4 (1.2–1.5) | |

| Magid et al. 2019 [92] | 588 USA College students | Intention to perform CPR | Perceived Behavioural Control | Beta (95%CI): 0.083 [0.047, 0.119] | |

| 12. Social influences | |||||

| Vaillancourt et al. 2013 [131] | 192 Canada Adults (≥55 years) | Intention to perform CPR | Normative | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | |

| Magid et al. 2019 [92] | 588 USA College students | Intention to perform CPR | Subjective norm | Beta (95%CI): 0.176 [0.133, 0.219] | |

| Studies Reporting differences in beliefs between participants who were willing to perform CPR and those who were unwilling | |||||

| Group | Belief (measure) | Difference between the groups | |||

| willing | unwilling | ||||

| 4. Beliefs about Capabilities | |||||

| Nolan et al. 1999 [101] | 786 Canada Adults (≥45) | 62% | 47% | Self-efficacy (confidence to perform CPR) | P < 0.001 |

| Schmitz et al. 2015 [117] | 110 (experimental group) | 11.1 | 8.6 | Self-efficacy (capacity belief) (self-efficacy score (higher score = greater efficacy) | P = 0.009 |

| 6. Beliefs about Consequences | |||||

| Parnell 2006 [106] | 494 New Zealand High School Students | 70% positive attitude | 47% negative attitude | Attitudes (% positive or negative attitude) | P < 0.001 |

| Schmitz et al. 2015 [117] | 110 (experimental group) | 22.3 | 18.8 | Attitudes (attitude score (higher score = more positive attitude) | P = 0.04 |

| 13. Emotion | |||||

| Nolan et al. 1999 [101] | 786 Canada Adults (≥45) | 2.17 | 2.42 | Anticipate negative emotions with CPR (mean number of negative emotions)) | P < 0.02 |

Table 6.

Summary of studies exploring relationship to victim (Domain 11. Environmental context and resources [29])

| Author | Country | Participants | n | Relatives (%) | Neighbour/Friend (%) | Unknown person (%) | Drug addict (%) | Unkempt (%) | Difference (%) | Other statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alhussein 2021 [33] | Saudi Arabia | Adults (≥18) | 413 (subsample aware of CPR) | 36 | 24 /22 | 16 | 20 | P < .001 | ||

| Anto-Ocra et al. 2020 [35] | Ghana | Adults (≥18) not medical | 277 | 78 | 60 | 46 | 32 | |||

| Axelsson 2000 [37] | Sweden | Adults (≥18 years) who had received training in basic CPR in January 1997. | 1012 | 97 | 91 | 70 | 17 | 7 | 27 | |

| Bin 2013 [40] | Saudi Arabia | High school students | 575 | 67 (male respondents) | 42 (male respondents) | 25 | ||||

| 67 (female respondents) | 24 (female respondents) | 43 | ||||||||

| Birkun 2018 [41] | Crimea | Adult (≥18 yrs) | 384 | 91 | 79 | 12 | ||||

| Bray 2017 [44] | Australia | Adult (≥18 yrs) | 404 | 91 (conventional CPR, low rate area) | 88 (conventional CPR, low rate area) | 3 | ||||

| Brinkrolf 2018 [46] | Germany | Witnesses of an OHCA | 101 | 70.20 | 60 | 59.40 | 11 | |||

| Chen 2017 [48] | China | Adult laypersons (≥18 yrs) + 3 < 18 years | 1841 | 98.7 | 76.3 | 22.4 | ||||

| Cheng 1997 [49] | Taiwan | Families of cardiac patients and general public | 856 | 92.40 | 88 | 75.10 | 17.3 | |||

| Cheng-Yu 2016 [50] | Taiwan | Adults (≥20 years) | 401 | 86.80 | 36.60 | 50 | ||||

| Chew 2009 [52] | Malaysia | School teachers. | 73 | 97.30 | 94.50 | 8.20 | ||||

| Cho 2010 [54] | Korea | Lay people aged 11 years and over | 890 | 55.80 | 19 | 36 | ||||

| Coons 2009 [56] | USA | Adult (≥18 years) | 370 (urban) | 84.5 (urban) | 51.3 (urban) | 33 | ||||

| 385 (rural) | 82.5 (rural) | 55 (rural) | 28 | |||||||

| Cu 2009 [57] | Australia | Caregivers of children presenting to the Emergency Department (≥18 years) | 348 | 81 | 64 | 17 | P < 0.001 | |||

| De Smedt 2018 [59] | Belgium | Schoolchildren aged 10–18, teachers and principals | 390 | 96 | 92 | 67 (woman) | 29 | |||

| Dracup 1994 [62] | USA | Family members of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 172 | 86 | 82 | 4 | ||||

| Fratta et al. 2020 [65] | USA | Attendees at large public gatherings (aged ≥14) | 516 | 69 | 45 | P < 0.001 | ||||

| Han 2018 [66] | Korea | Family members (≥18 years) of patients at risk of cardiac arrest | 203 | 68 (CS group) | 64 (CS) | 4 | ||||

| 76 (CV group) | 65 (CV) | 5 | ||||||||

| 67 (no risk group) | 50 (no risk) | 17 | ||||||||

| Hollenberg et al. 2019 [69] | Sweden | School students (13 years) | 641 | 85 (directly after training native) | 38 (directly after training native) | 47 | NR | |||

| 84 (Directly after training other native) | 52 (Directly after training other native) | 32 | ||||||||

| 78 (at 6 mths native) | 31 (at 6 mths native) | 47 | ||||||||

| 80 (at 6 months other native | 42 (at 6 months other native | 38 | ||||||||

| Iserbyt 2016 [73] | Belgium | Secondary school pupils | 313 | 51 (F) | 49 (F) | 11 (F) | 40 (F) | All scores increased with training | ||

| 49 (M) | 48 (M) | 8 (M) | 41 (M) | |||||||

| Jelinek 2001 [74] | Australia | General public (age not recorded) | 803 | 96 (trained < 12 months) | 54.5 (trained < 12 months) | 42 | ||||

| 94.4 (trained 1–5 y) | 51.8 (trained 1-5y) | 43 | ||||||||

| 90 (trained ≥5y) | 45.2 (trained≥5 y) | 45 | ||||||||

| Karuthan et al. 2019 [78] | Malaysia | College students | 393 | 68 | 55 | 13 | ||||

| Kuramoto 2008 [80] | Japan | Adults (≥15 years) | 1132 | 13 | 7 | 6 | ||||

| Lam 2007 [81] | Hong Kong | Laypersons who attended the CPR course (aged ≥7 years) | 305 | 87 | 61 | 26 | ||||

| Lester 1997b [85] | Wales | General public | 241 | Adult 100 (definitely or probably) | 100 | 99 | 1 | |||

| Locke 1995 [88] | USA | Lay people (minimum age not reported) & health care providers | 975 | 94 | 55 | 39 | ||||

| Mecrow 2015 [96] | Bangladesh | Lay people (≥10 years) | 721 | Data extracted for mother | Data extracted for friend of same sex | |||||

| 88 (M) | 80.8 (M) | 50 (M) | 38 (M) | |||||||

| 96.4 (F) | 75.3 (F) | 47 (F) | 49 (F) | |||||||