Abstract

Psychiatric genetics has made substantial progress in the last decade, providing new insights into the genetic etiology of psychiatric disorders, and paving the way for precision psychiatry, in which individual genetic profiles may be used to personalize risk assessment and inform clinical decision‐making. Long recognized to be heritable, recent evidence shows that psychiatric disorders are influenced by thousands of genetic variants acting together. Most of these variants are commonly occurring, meaning that every individual has a genetic risk to each psychiatric disorder, from low to high. A series of large‐scale genetic studies have discovered an increasing number of common and rare genetic variants robustly associated with major psychiatric disorders. The most convincing biological interpretation of the genetic findings implicates altered synaptic function in autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia. However, the mechanistic understanding is still incomplete. In line with their extensive clinical and epidemiological overlap, psychiatric disorders appear to exist on genetic continua and share a large degree of genetic risk with one another. This provides further support to the notion that current psychiatric diagnoses do not represent distinct pathogenic entities, which may inform ongoing attempts to reconceptualize psychiatric nosology. Psychiatric disorders also share genetic influences with a range of behavioral and somatic traits and diseases, including brain structures, cognitive function, immunological phenotypes and cardiovascular disease, suggesting shared genetic etiology of potential clinical importance. Current polygenic risk score tools, which predict individual genetic susceptibility to illness, do not yet provide clinically actionable information. However, their precision is likely to improve in the coming years, and they may eventually become part of clinical practice, stressing the need to educate clinicians and patients about their potential use and misuse. This review discusses key recent insights from psychiatric genetics and their possible clinical applications, and suggests future directions.

Keywords: Genetics, genomics, psychiatry, precision medicine, common variants, rare variants, pleiotropy, polygenic risk score, nosology

Psychiatric disorders are among the main causes of morbidity 1 and mortality 2 worldwide, posing a substantial burden on individuals and society. They typically begin in adolescence or young adulthood and often have a chronic course, leading to many years lived with debilitating illness. In addition, individuals with severe mental illness often have poorer socioeconomic status3, 4, frequently experience stigma 5 , and have a higher occurrence of both substance use 6 and somatic disease 7 , all of which negatively affect well‐being and quality of life. The average life expectancy of people with severe mental illness is estimated to be approximately 10 years shorter compared to the general population2, 8, with the excess mortality due to both physical health causes, particularly cardiovascular disease9, 10, and mental health‐related causes, such as suicide 11 .

As emphasized by the World Health Organization 12 , there is an urgent need to improve mental health care. Existing treatment modalities may provide clinically meaningful effects in many psychiatric disorders13, 14. However, treatment is rarely curative – many patients experience relapses and unpleasant adverse effects, and lack of therapeutic response is common15, 16. Inadequate therapeutic options can largely be attributed to the limited understanding of the causes of mental illness, despite decades of intensive research. By the same token, psychiatric nosology still relies on traditional diagnostic distinctions based on clinical observations17, 18. In the two current leading diagnostic classification systems, the International Classification of Diseases 17 and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 18 , psychiatric disorders are still primarily diagnosed according to their signs and symptoms. There is a lack of objective biomarkers, in contrast to most other medical fields, making clinical psychiatry more susceptible to unwanted variability in both diagnostic and therapeutic decision‐making 19 . Although the present diagnostic categories have clinical utility, there is little evidence to suggest that they represent truly discrete entities with natural boundaries20, 21, as indicated by the high comorbidity and shared symptomatology across different mental disorders22, 23, and the high heterogeneity within diagnostic categories 24 .

To improve the care and prevention of mental illness, a better understanding of the underlying biological mechanisms is needed. The intrinsic challenges in studying the living human brain and the uncertain validity of animal models of mental illness 25 have limited progress of biological research in psychiatry. As a consequence, there have been no major therapeutic advances in psychiatry in the past decades 26 , and the potential new treatment options that currently receive most attention represent repurposing of existing drugs such as ketamine 27 or psychedelics 28 . However, the substantial heritability of psychiatric disorders 29 indicates that genetic research could uncover otherwise inaccessible pathobiological insights, and could also aid in disentangling environmental effects and gene‐environment interplay.

Despite great expectations as DNA sequencing technologies became more widely available over the course of the second half of the 20th century, psychiatric genetics got off to something of a false start in the 1990s and early 2000s. A series of findings using a candidate gene approach were subsequently shown to lack reproducibility, reducing confidence that genetic research could lead to the discovery of genes for mental illness30, 31. The major turning points came with the sequencing of the human genome in 2003 32 , and the creation of reference datasets cataloguing human genetic variation across different populations33, 34, which allowed for a systematic exploration of DNA sequence variants linked to human traits and diseases.

Since then, there has been a steady and accelerating progress in human genetics 35 , driven by a combination of technological innovation, more advanced statistical analytical tools, reduced costs for genotyping and sequencing DNA, more precise knowledge about the genome, and international collaboration. Psychiatric genetics has been at the forefront of these efforts, recognizing the need to assemble large‐scale case‐control cohorts of psychiatric disorders to reliably identify genetic variants, most of which have very weak effects, which have gradually led to the discovery of multiple genetic risk variants for mental illness36, 37. However, while the last decade has brought major advances in our understanding of the genetic architecture of mental illness, these discoveries have not yet been translated into improved care for people with mental illness, which remains the key challenge for the field.

Here, we aim to provide a comprehensive review of the genetic risk underlying psychiatric disorders. We summarize what we have learnt from genetic research in psychiatry during the past decade, focusing on attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anorexia nervosa, anxiety disorders, autism spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, obsessive‐compulsive disorder (OCD), post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia, and Tourette's syndrome. We also discuss how the advances in genetics may enable precision medicine approaches, and we discuss future directions, challenges and opportunities.

DISSECTING THE GENETIC RISK OF MENTAL ILLNESS

The nature vs. nurture debate on the causes of mental illness is now understood to be a false dichotomy38, 39. Variation in risk of mental illness is neither solely due to variation in DNA or environmental factors, but both nature and nurture unequivocally contribute in closely intertwined processes.

For millennia, it has been observed that mental illness tends to run in families40, 41. This familial aggregation has since been confirmed by large‐scale family and population‐based studies. For example, first‐degree relatives of a proband with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia have approximately 6‐8 and 10 times higher risk of developing these disorders, respectively, compared to relatives without an affected family member 42 . Relatives of probands with a psychiatric disorder also have increased risk of developing other psychiatric disorders 43 , which indicates that familial risk of mental illness transcends diagnostic categories, suggesting shared etiology.

In the past 50 years, twin, adoption, family and population‐based studies of increasing quality have demonstrated that all major psychiatric disorders have a substantial heritability, meaning that a considerable proportion of the variation in risk of developing mental illness is attributable to differences in genetic factors between individuals29, 44. Environmental exposures, including social determinants, also influence risk of illness along with genetic factors 45 , with the relative contributions varying across disorders 36 . The etiology of psychiatric disorders may also be influenced by non‐inherited somatic DNA variants accumulating in brain tissue throughout development and ageing 46 , as well as by stochastic variation in biological processes 47 .

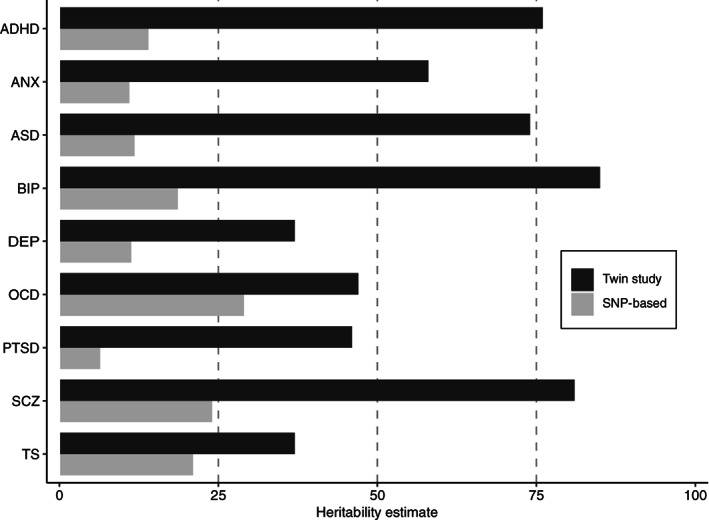

The estimated heritabilities are generally higher in psychotic and neurodevelopmental disorders (74‐85%)42, 48, 49, 50, 51 than in mood and anxiety disorders (37‐58%)52, 53 (see Figure 1), indicating that a larger fraction of the variation in risk of developing mood and anxiety disorders is explained by environmental factors. Note that the estimated heritability of a specific disorder can vary between populations, due to population‐specific variation in genetic and environmental factors, and differences in phenotypic definitions such as diagnostic criteria.

Figure 1.

Estimates of twin‐heritability (black) and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)‐based heritability (grey) for major psychiatric disorders. ADHD – attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder, ANX – anxiety, ASD – autism spectrum disorder, BIP – bipolar disorder, DEP – depression, OCD – obsessive‐compulsive disorder, PTSD – post‐traumatic stress disorder, SCZ – schizophrenia, TS – Tourette's syndrome.

Regardless of the heritability of a trait, identifying genetic risk variants could potentially yield valuable insights into its etiology by pointing to core biological mechanisms. In human DNA, there are millions of genetic variants that differ between individuals and may confer risk or protect against illness 54 . A genetic variant may represent a difference in a single genomic position, such as a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), in which a single nucleotide in DNA differs between people, or larger structural changes such as copy number variants (CNVs), which are deletions or duplications of genomic regions.

According to the frequency in a population of the less frequent allele (termed the minor allele frequency, MAF), genetic variants are typically defined as common (MAF >1%), uncommon (MAF 0.1‐1%), rare (MAF <0.1%), and ultra‐rare (MAF <0.001%), although the exact definitions vary to some extent across studies. In addition to inherited variants, newly occurred de novo mutations in an individual may also influence risk of illness and potentially exert large phenotypic effects.

Importantly, genomic findings in a given population cannot be readily generalized to populations of other ancestries, since the frequency of variants, their specific effect sizes, as well as the non‐random correlation pattern among variants (referred to as linkage disequilibrium, LD) vary across ancestries, in addition to the different environmental contexts55, 56.

COMMON VARIANTS

In the past decade, genome‐wide association studies (GWAS) have become the most successful approach to link genetic variants to human phenotypes 57 . A GWAS systematically screens millions of common genetic variants for association with a given phenotype in a hypothesis‐free manner, by comparing the frequency of variants in cases vs. controls or across a continuous measure. In order to conduct a GWAS, hundreds of thousands of common genetic variants are genotyped in each individual participant, using relatively inexpensive SNP arrays, and additional genetic variants are imputed to generate complete genotypes for each individual.

After the first GWAS reporting significant variant associations with a complex human phenotype was published in 2005 58 , the number and sample sizes of GWAS have grown exponentially 59 . At the time of writing, GWAS have identified associations between more than 400,000 common genetic variants and hundreds of human traits and disorders according to the GWAS catalog 60 , and the number is rapidly increasing. Note that GWAS typically report trait‐associated genomic loci, which are DNA regions that involve multiple genetic variants highly correlated with each other due to LD, wherein one or several variants may independently influence the phenotype.

The ability of a GWAS to identify a trait‐affecting genetic variant depends on the population prevalence of the variant, its strength of association with the trait, and the statistical power of the study, which corresponds to its sample size. Hence, as GWAS samples increase in size, more genetic variants are discovered. Since a GWAS scans a large number of SNPs, it is necessary to control for multiple comparisons to avoid false positive findings, which results in a stringent genome‐wide significance threshold, typically p<5x10−8. Moreover, since common genetic variants have tiny effects (e.g., small differences in the frequency of risk alleles between cases and controls), very large GWAS sample sizes are needed to achieve sufficient statistical power to discover SNPs passing the genome‐wide significance threshold.

The ability of GWAS to discover SNPs also depends on the unique characteristics of the common variant architecture underlying a phenotype 61 . This includes the polygenicity of the phenotype, which refers to the number of common genetic variants influencing the phenotype, and the SNP‐heritability, which refers to the proportion of phenotypic variance explained by common genetic variants. Estimates of SNP‐heritability62, 63 have confirmed that part of the risk of developing psychiatric disorders is captured by common genetic variation, with SNP‐heritabilities ranging between 5 and 25% for ten major psychiatric disorders64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73 (see Figure 1 and Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of largest genome‐wide association studies (GWAS) on major psychiatric disorders

| Disorder | Largest GWAS | Cases | Controls | Ancestry | GWAS loci | SNP‐heritability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD | Demontis et al 68 | 38,691 | 186,843 | European | 27 | 14% |

| AN | Watson et al 67 | 16,992 | 55,525 | European | 8 | 11% |

| ANX | Levey et al 69 | 175,163 (continuous measure) | ‐ | European | 5 | 5.6% |

| ASD | Grove et al 66 | 18,381 | 27,969 | European | 5 | 11.8% |

| BIP | Mullins et al 65 | 41,917 | 371,549 | European | 64 | 18.6% |

| DEP | Levey et al 70 | 340,591 | 813,676 | European | 178 | 11.3% |

| OCD | Strom et al 73 | 14,140 | 562,117 | European | 1 | 16.4% |

| PTSD | Stein et al 71 | 59,513 | 329,554 | European | 4 | 6.4% |

| SCZ | Trubetskoy et al 64 | 76,755 | 243,649 | European (86%), East Asian (10%), African American (3%) and Latino (1%) | 287 | 24% |

| TS | Yu et al 72 | 4,819 | 9,488 | European | 1 | 21% |

Risk loci identified at the genome‐wide significance threshold. SNP‐heritability estimated using LD score regression. ADHD – attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder, AN – anorexia nervosa, ANX – anxiety, ASD – autism spectrum disorder, BIP – bipolar disorder, DEP – depression, OCD – obsessive‐compulsive disorder, PTSD – post‐traumatic stress disorder, SCZ – schizophrenia, TS – Tourette's syndrome.

The estimated SNP‐heritabilities for psychiatric disorders are thus much lower than the estimated twin‐heritabilities42, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53. This issue is often referred to as the “missing heritability” problem 74 , and also applies to other behavioral and somatic phenotypes. This problem is still not fully resolved, but may be explained by rare variants which are not included in the standard GWAS, gene‐gene or gene‐environment interplay, and inflated twin‐heritability estimates, possibilities which are not mutually exclusive74, 75, 76. However, a recent study indicated pervasive downward bias of standard SNP‐heritability estimates, suggesting that the SNP‐heritabilities of psychiatric disorders may in reality be higher than current estimates 77 .

One of the key insights emerging from GWAS is that most complex human phenotypes are highly polygenic, influenced by thousands of common variants with miniscule effects 59 . Hence, there is no single “disease‐gene” for psychiatric disorders, but thousands of genetic variants that act together and collectively influence risk of illness. Given that most of these genetic variants are commonly occurring, every human being has a genetic risk to each psychiatric disorder, from low to high.

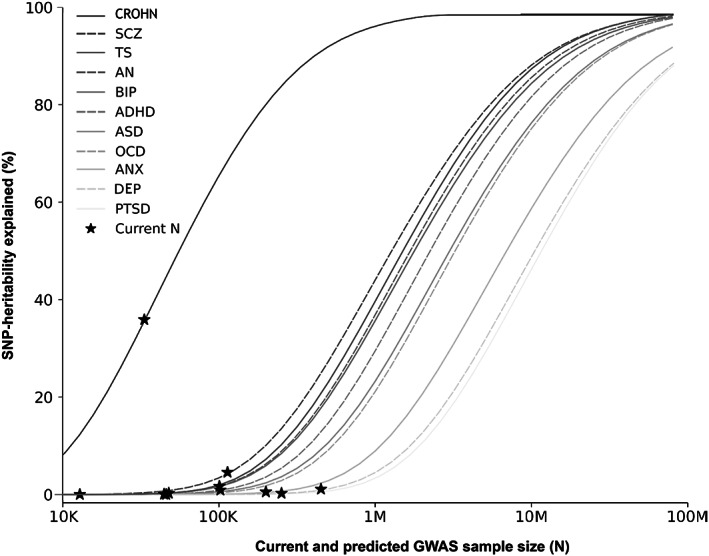

Compared to somatic phenotypes, both psychiatric disorders and behavioral phenotypes generally have larger polygenicities despite similar SNP‐heritabilities61, 78, 79. This means that each common variant tends to have smaller effects in behavioral than somatic phenotypes. As a consequence, larger GWAS sample sizes are needed to identify a comparable fraction of the common variant architectures underlying psychiatric disorders than somatic disorders (see Figure 2). As an example, approximately one third of the heritability of Crohn's disease due to common genetic variants has been identified by GWAS with 12k cases and 34k controls 80 . In comparison, more than 10 times the number of GWAS participants are estimated to be needed to identify a similar proportion of the common genetic variance underlying schizophrenia (see Figure 2). Thus, given the high polygenicities of psychiatric disorders, which likely reflect more complex and/or heterogenous genetic etiologies, their GWAS discovery trajectories are still trailing those of somatic traits and disorders by many years.

Figure 2.

Statistical power calculations for current and future genome‐wide association studies (GWAS) on major psychiatric disorders. The figure shows the proportion of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)‐based heritability explained by variants detected at the genome‐wide significance threshold (vertical axis) as a function of GWAS sample size across psychiatric disorders. Crohn's disease (CROHN) is included as an example of somatic disorder. For each disorder, the current effective sample size (indicated by asterisk) is shown. ADHD – attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder, AN – anorexia nervosa, ANX – anxiety, ASD – autism spectrum disorder, BIP – bipolar disorder, DEP – depression, OCD – obsessive‐compulsive disorder, PTSD – post‐traumatic stress disorder, SCZ – schizophrenia, TS – Tourette's syndrome.

Large‐scale international collaboration, with the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium 81 as the main driving force, has led to the assembly of increasingly productive GWAS involving tens of thousands of participants, discovering reproducible common variant associations for most major psychiatric disorders64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73 (see Table 1). In addition, several GWAS of other clinically relevant phenotypes in psychiatry have been published in recent years, such as treatment resistance in schizophrenia 82 , response to lithium 83 , antidepressant response 84 , suicide attempt 85 , cognitive function 86 , insomnia 87 , risky behavior 88 , mood instability 89 , and antisocial behavior 90 . Well‐powered GWAS on substance use disorders have also been conducted in recent years91, 92. However, there is still a lack of sufficiently powered GWAS on personality disorders 93 and eating disorders, apart from anorexia nervosa 94 . Overall, the common variant data on psychiatric disorders are consistent with a liability threshold model, in which a large number of risk alleles additively contribute to overall risk. Individually, the trait‐associated common variants have minuscule effects on risk of illness, with odds ratios generally below 1.2.

The most well‐powered GWAS in psychiatry to date is on schizophrenia, comprising 76,755 cases and 243,649 controls, in which 287 distinct genomic loci harboring genome‐wide significant common variant associations were discovered 64 . Despite this success, the independent significant genetic variants still explain less than 10% of the SNP‐heritability of schizophrenia, indicating that most of its common variant architecture remains to be identified (see Figure 2). In other psychiatric disorders, GWAS have even lower power, and the proportion of SNP‐heritability explained by genome‐wide significant variants is correspondingly lower (see Figure 2).

Estimates of polygenicity indicate that tens of thousands common genetic variants may influence each psychiatric disorder, although there is a considerable margin of uncertainty in these estimates 61 . In a recent cross‐disorder investigation of GWAS data, depression appeared to be more than twice as polygenic as ADHD, possibly reflecting less biological heterogeneity in ADHD than depression 95 . Note that the genetic investigation of depressive disorders has focused on different phenotypic definitions, owing to different case ascertainment. While major depressive disorder refers to cases found to meet standard diagnostic criteria after structured interviews by trained interviewers, the depression phenotype also includes self‐reported treatment or diagnosis of clinical depression, and is therefore less specific 96 .

RARE VARIANTS

In the past decade, rare and de novo sequence variants and pathogenic CNVs have been implicated in most psychiatric disorders, except for eating disorders and personality disorders. Due to their low frequency, rare variants explain less heritability in the population than common genetic variants. However, rare variants may confer substantially higher risk of illness in the individual, due to more deleterious impact on protein function or expression or, in the case of CNVs, by impacting several genes.

There is robust evidence that the burden of rare large‐effect variants is highest in neurodevelopmental disorders and psychotic disorders, in particular in cases with intellectual disability or developmental delay97, 98, 99, 100. This is in line with the decreased fecundity associated with neurodevelopmental and psychotic disorders 101 , which prevents genetic variants with large effects on risk of illness from becoming common in the population. Correspondingly, de novo variation, which on average has been exposed to less selective pressure, shows more severe predicted functional consequences than inherited variation 102 .

Whole exome sequencing (WES) and whole genome sequencing (WGS) studies are generally underpowered to detect specific rare single nucleotide variants (SNVs), given the rarity of these variants. To circumvent this issue, a common approach is to evaluate the burden of rare sequence variants in individual genes by comparing cases and controls or using family‐based designs. To reduce the number of variants assessed, it is also common to focus on exonic SNVs using WES data, thereby ignoring the vast number of noncoding variants in WGS data.

WES studies in autism spectrum disorder98, 102, 103, ADHD 98 , Tourette's syndrome 104 , OCD 105 , schizophrenia98, 99, 106, 107, bipolar disorder98, 108 and major depressive disorder 109 have revealed an excess burden of ultra‐rare protein‐truncating and damaging missense variants in genes under strong evolutionary constraint, and discovered many specific risk genes, in particular in autism spectrum disorder98, 102, 103 and schizophrenia98, 99, 106, 107.

The identified protein‐truncating variants typically result in partial or complete loss of protein function, while the missense variants have a less deleterious impact. The evolutionary constrained genes have a high probability of being intolerant to loss‐of‐function mutations, and are relatively depleted of equivalent protein‐disrupting variants in the general population 110 . Recently, such genes have also been implicated by common variant findings for schizophrenia 111 .

Rare CNVs at several loci have been robustly associated with autism spectrum disorder 100 , schizophrenia112, 113 and ADHD 114 , while only a few specific CNVs have been implicated in OCD 115 , Tourette's syndrome 116 , major depressive disorder 117 , and bipolar disorder 118 . A CNV study in bipolar disorder found that only cases with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type were enriched for CNVs 119 , further indicating that rare CNVs may play a larger role in psychotic than mood disorders.

Despite potentially having very large effects, the penetrance of rare pathogenic variants is incomplete, meaning that only a fraction of carriers display a certain clinical outcome. Moreover, carriers may present a wide range of health outcomes, depending on the individual's DNA constitution, environmental stimuli, and chance.

By integrating datasets on both rare and common genetic variants in autism spectrum disorder 120 and schizophrenia121, 122, it has been demonstrated that genetic variation at both ends of the allele frequency spectrum jointly influences risk of these disorders in the same individuals. For instance, the clinical outcomes of 22q11.2 deletions are highly heterogenous, including schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, cognitive dysfunction, neurological disorders and somatic abnormalities 123 . Among carriers of 22q11.2 deletions, a higher burden of common risk alleles for schizophrenia was linked to higher risk of that disease 124 . This indicates that common genetic risk may modulate the penetrance of rare variants such as the 22q11.2 deletion, and may eventually help prediction of clinical outcomes such as psychosis in this patient group.

In autism spectrum disorder, a recent study demonstrated an inverse correlation of the burden of rare and common genetic variants among cases, indicating a spectrum of genetic risk among cases, ranging between more monogenic to polygenic risk architectures 125 . Moreover, different aspects of the common and rare genetic risk were differently associated with clinical measures in the disorder 125 . This indicates that different genetic loadings may map to different aspects of the phenotypic spectrum, pointing to potential utility of genetic profiling in the clinic to facilitate more personalized treatment.

EMERGING BIOLOGICAL INSIGHTS

One of the key aims of human genetics is to gain insights into the underlying etiology of illness, which might inform the development of new therapeutic interventions and help identify biomarkers. However, translating genetic findings into biological mechanisms is not straightforward. To obtain a complete mechanistic understanding of a disorder's genetic risk architecture, it is necessary to: a) identify the specific causal variant underlying a genetic signal; b) determine the functional impact of the genetic variant; and c) determine how all of the genetic risk variants act together to collectively influence biological pathways in specific cell types, tissues and organs, across developmental stages, and in concert with environmental factors126, 127. This is a tremendous challenge, warranting comprehensive animal studies, cell‐biology experiments, and advanced computational approaches. The current mechanistic interpretation is also limited by the incomplete understanding of the physiological role of most genes and proteins, including how they interact in signaling networks and pathways 128 .

Fine‐mapping procedures, for example leveraging trans‐ancestry tools 129 , may help prioritize the most likely causal variants in GWAS loci 130 . However, the causal variant does not necessarily affect the closest gene. A genetic variant may exert its phenotypic effect by disrupting a single protein structure and function, or by regulating the expression of one or more genes locally or over long genomic distances. Indeed, most GWAS associations are detected in noncoding regions131, 132, suggesting that most common variants may exert their phenotypic effect through regulatory mechanisms, complicating mechanistic interpretation. To help prioritize the most likely causal genes from GWAS loci, algorithms integrating diverse functional resources have been developed in recent years133, 134.

The biological interpretation of rare variants largely depends on the type of variant in question. Since most rare pathogenic CNVs disrupt large genomic segments, often including many genes, inferring their biological consequences is challenging. By contrast, the identification of specific genes harboring rare coding variants in whole sequencing studies may provide more direct mechanistic hypotheses about disease etiology.

To evaluate the biological implications of genetic findings, it is common to evaluate whether the implicated risk genes are enriched for expression in particular cell‐types or tissues, and to conduct gene‐set analyses testing whether a group of genes are enriched in predefined gene‐sets based on their biological functions 127 . Note that differences in methodology and power of the genetic studies limit comparisons of gene‐set enrichment results across psychiatric disorders.

Expression analyses of GWAS data on schizophrenia64, 135, autism spectrum disorder 125 , bipolar disorder65, 136, major depressive disorder70, 137, ADHD 68 , and anorexia nervosa 67 have all revealed enrichment of expression in human brain tissue, confirming the importance of brain‐expressed genes in the etiology of major psychiatric disorders. In general, the risk genes are globally expressed in the brain, with no major differential association across brain regions, although the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Brodmann area 9) consistently shows the strongest enrichment of expression across psychiatric disorders64, 65, 68, 70, 72.

Furthermore, GWAS associations for schizophrenia 64 , bipolar disorder 65 , depression 70 and ADHD 68 are enriched in genes highly expressed in neurons, with no apparent enrichment in other brain cells such as oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, endothelial cells, microglia or neural stem cells. Using neuronal subtype specific expression data, GWAS analyses on schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and ADHD implicated both excitatory and inhibitory neurons64, 65, 68. For ADHD, GWAS associations were additionally enriched for expression in dopaminergic midbrain neurons. This is consistent with the link between ADHD and deficits in the reward system, motor control and executive functioning, all of which are under dopaminergic control 68 .

The recent GWAS associations for schizophrenia were strongly enriched for genes with high expression in excitatory glutamatergic neurons in the cerebral cortex and the hippocampus (pyramidal CA1 and CA3 cells, and granule cells of dentate gyrus), and in cortical inhibitory interneurons 64 . While GWAS associations for autism spectrum disorder were not significantly enriched in any specific cell type 125 , which likely reflects the low power of relevant GWAS 66 , risk genes for autism spectrum disorder implicated by rare variants are enriched in genes highly expressed in both excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the human cortex 125 .

In schizophrenia, well‐powered datasets on both common and rare variants have allowed for a more comprehensive mechanistic interrogation, with emerging biological convergence across both ends of the allelic frequency spectrum64, 106, 111, 138. Both rare and common variant associations with schizophrenia have strongly implicated genes influencing synaptic organization, differentiation and signaling, at both presynaptic and postsynaptic locations64, 106, 139. One of the gene sets most strongly associated with schizophrenia is the targets of the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP)140, 141, 142, a protein that is highly expressed in neurons, which binds mRNAs from multiple genes implicated in synapse development and plasticity 143 .

The strongest common variant association with schizophrenia is localized to the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)135, 144, 145, a genomic region that contains many genes linked to infection and autoimmunity. A comprehensive analysis demonstrated that part of the MHC association with schizophrenia is driven by structural variation in the gene C4, which encodes complement component 4 (C4) 146 . The complement system is part of the innate immune system and also contributes to normal brain development by eliminating immature synapses147, 148. Schizophrenia risk at C4 was associated with greater expression of the C4 isotype C4A, which is present at human synapses and neuronal components. In mice, C4 was shown to promote synapse elimination during development. These findings indicate that at least part of the MHC association with schizophrenia may implicate inappropriate synaptic maturation 146 . However, note that the MHC risk locus only represents a minor part of the genetic risk architecture underlying schizophrenia.

Risk genes for schizophrenia implicated by both common and rare variant studies are also linked to biological processes related to excitability, in particular voltage‐gated calcium channels, and multiple neurotransmitters64, 106, 138. In a recent WES study 106 , two of the ten implicated genes, GRIA3 and GRIN2A, encode receptor subunits involved in glutamatergic neurotransmission. These findings corroborate previous GWAS discoveries 138 , providing support for the glutamatergic hypothesis of schizophrenia 149 . An analysis of the effects of schizophrenia‐risk variants in neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells revealed a synergistic effect on gene expression and synaptic function 150 , emphasizing the importance of studying the combinatorial effects of risk variants to fully understand their biological consequences.

Genes linked to ion channels, neurotransmitter receptors and synaptic proteins have also been implicated in GWAS on bipolar disorder65, 136 and depression 151 . However, since the GWAS discoveries for these and other psychiatric disorders still trail those for schizophrenia, the biological interpretation of these data is less robust.

Risk genes for autism spectrum disorder, most of which are implicated from rare variant studies, are strongly linked to synaptic function as well as chromatin remodeling, which affect the regulation of the expression of multiple other genes, thereby complicating mechanistic interpretation66, 100, 102, 125, 152, 153, 154. An analysis of expression patterns of risk genes in autism spectrum disorder found that risk genes implicated by rare variants were more strongly expressed during fetal development than those implicated by common variants, which displayed relatively higher expression at later developmental stages 125 .

Among risk genes shared between schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder and developmental disorders harboring de novo coding variants, a recent study demonstrated that the same classes of mutations were generally involved 155 . This finding suggests that these overlapping genetic signals reflect shared biological mechanisms, further supporting a continuum in the etiology of these disorders, and impairment of neurodevelopment as part of the etiology in schizophrenia 156 .

Integrating GWAS and WES data on autism spectrum disorder has revealed insights into the gender differences in risk of this disorder, which is diagnosed three to four times more often in males than in females. Female individuals with the disorder tend to have a higher burden of common and rare genetic variants than their male counterparts, indicating that a higher genetic loading is necessary to result in development of the condition in females, in line with a female protective effect125, 153. Moreover, among parents of cases with autism spectrum disorder, who did not have the disorder themselves, the mothers had significantly higher polygenic risk for the disorder than the fathers. This supports the notion that females can accumulate more risk before being diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder 157 . Despite known gender differences in the risk for other psychiatric disorders 158 , current genetic data have not yet revealed convincing insights that could explain these differences.

Gene‐set analyses can also be applied to targets of existing drugs, which may inform pharmacological research and reveal opportunities for repurposing. Drugs supported by genetic evidence appear to have a higher success rate in clinical development 159 . Among 50 novel drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2021, two‐thirds were subsequently shown to have some genetic support, although this approach is vulnerable to confirmation bias 160 .

In the latest GWAS on bipolar disorder, common variant associations were enriched in targets of several classes of pharmacological agents, including mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, antiepileptics, and calcium channel blockers 65 . These findings suggest that existing drugs in bipolar disorder have some biological support based on genetic data, and have motivated efforts to investigate the potential efficacy of calcium channel antagonists in this disorder 161 , with lamotrigine being an N‐type calcium channel blocker widely used in treatment of bipolar type II disorder. A recent WES study also found enrichment of rare damaging coding variants in calcium channel genes among individuals with bipolar disorder 108 .

An analysis of GWAS data on major depressive disorder revealed enrichment of common variant associations in genes encoding proteins targeted by antidepressant medication 137 . Another pharmacological enrichment analysis implicated ten existing drugs, three of which have been linked to depression (riluzole, cyclothiazide and felbamate), and four modulate estrogen (tamoxifen, raloxifene, diethylstilbestrol, and Implanon – an etonogestril implant) 70 . A recent systematic umbrella review of the relationship between serotonin and depression did not find any genetic support for a role of serotonin in depression 162 . However, this conclusion is premature, given that less than 10% of the genetic risk architecture of depression is uncovered (see Figure 2), and even less is known about its biological consequences, and the biological heterogeneity between patients.

The biological interpretation of genetic data is complicated by the fact that genetic associations likely capture different types of causal relationships, at least for highly polygenic complex phenotypes such as psychiatric disorders. The genotype‐phenotype associations detected in a GWAS can be decomposed into three main sources: direct genetic effects, indirect genetic effects, and confounding effects 163 . The direct genetic effects represent the causal effects of a genetic variant on a phenotype via biological pathways. The indirect effects represent situations where a genetic variant in an individual affects the phenotype in another individual through the influence on the environment, for example via parental behavior. Parental genetic variants do not need to be transmitted to the offspring to have an indirect genetic effect 164 . Confounding effects include assortative mating or population stratification, which affect the distribution of genetic variants within populations. The presence of confounding and indirect genetic effects will impact analysis of genetic data, as they dilute the genetic signal representing direct causative mechanisms.

Compared to standard population‐based GWAS, family‐based GWAS are less likely to be affected by confounding and indirect genetic effects. In a recent analysis of family‐based and population‐based GWAS for 25 phenotypes 165 , the GWAS estimates for behavioral phenotypes, including depressive symptoms, were found to be considerably smaller in family‐based versus population‐based GWAS, while the GWAS estimates were similar for somatic molecular traits such as C‐reactive protein and lipids 165 . These findings indicate that a large part of the genetic associations for behavioral phenotypes may represent indirect or confounding effects, warranting more research using large‐scale family‐based GWAS on psychiatric disorders. It is not yet clear how these different sources of genotype‐phenotype association may affect estimates of the polygenicity of a trait.

Another aspect complicating biological interrogation of psychiatric disorders is that multiple potential causal biological pathways may be involved 166 . The clinical heterogeneity among individuals with a given psychiatric disorder is likely mirrored by biological heterogeneity of a similar extent. A case‐control GWAS, however, only represents the mean differences in genetic associations between cases and controls. This summary measure may therefore conceal biological differences among potential subgroups of patients, who may have different clinical profiles and respond differently to therapeutic interventions.

Furthermore, the extent to which genetic findings and their biological consequences are generalizable across populations remains to be clarified. This is a pressing issue in human genetics, since most GWAS have been predominantly based on individuals of European descent 167 , which is also the case in psychiatric genetics (see Table 1). Genetic studies are often based on one ancestral group to avoid mistaking systematic differences between ancestries for genetic influences underlying a trait. The lack of ancestral diversity also applies to functional genomic datasets, such as tissue‐specific gene expression, DNA methylation and chromatin interactions168, 169, which are necessary to reliably interpret genomic data.

The transferability of genetic risk across populations may be affected by differences in allele frequencies, correlation among genetic variants (referred to as the LD structure), variation in the functional impact of a genetic variant, and the overall differences in genetic and environmental contexts. Moreover, the causes, presentation and diagnosis of psychiatric disorders may differ across populations 170 . A recent trans‐ancestry GWAS analysis of schizophrenia reported a genetic correlation of 0.98 between two cohorts of East Asian and European descent, indicating that the common variant architecture of the disease is fundamentally the same in these two populations, despite differences in known environmental risk factors such as migration, urbanicity and drug abuse 171 . By contrast, a trans‐ancestry GWAS analysis of major depressive disorder reported a genetic correlation of only 0.41 between two cohorts of East Asian and European descent, indicating larger differences in the genetic architecture underlying the disorder in these two populations 172 . These findings suggest that genetic heterogeneity across ancestries may differ across psychiatric diagnoses, further emphasizing the importance of prioritizing greater diversity in psychiatric genetics.

SHARED GENETIC INFLUENCES BETWEEN MENTAL DISORDERS AND WITH OTHER TRAITS AND DISEASES

Clarifying the nature of shared genetic influences between psychiatric disorders and with other traits and diseases has become an important research area in psychiatric genetics. This research could inform ongoing processes aiming to reconceptualize psychiatric nosology173, 174, increase the understanding of the pervasive comorbidity and shared clinical features across mental disorders22, 23, help disentangle heterogeneity within diagnostic categories and identify subgroups with similar clinical features, and possibly reveal shared etiology with other traits and disorders.

Given the high polygenicity of human traits and disorders and the finite number of genetic variants, it follows that many genetic variants are expected to influence more than one phenotype, a phenomenon termed genetic pleiotropy 175 . Yet, the extent of genetic pleiotropy revealed across human traits and disorders in recent years has probably surpassed the expectations of many59, 79, and it is becoming increasingly clear that the genetic relationship between psychiatric disorders, and between psychiatric disorders and other phenotypes, is more extensive and complex than has been widely recognized95, 138, 176.

Genetic influences of psychiatric disorders are shown to overlap with a wide range of brain‐related and somatic human traits and disorders, including cognitive traits86, 177, 178, 179, 180, neurological disorders181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 186, substance use187, 188, 189, and cardiovascular disease and risk factors190, 191, 192, 193. Among the many cross‐trait genetic associations, it is important to emphasize that psychiatric disorders are also genetically linked to positive traits, which we believe is an important message to communicate to patients and the public. For example, risk for autism spectrum disorder is genetically correlated with higher educational attainment 194 and better cognitive performance 86 , while risk for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia is genetically correlated with higher levels of the personality trait openness to experience 195 and creativity 196 .

Both common and rare genetic variants exert genetic pleiotropy, but the phenomenon is more widely documented for common variants, due to the high number of well‐powered GWAS reporting common variant associations 60 . In a comprehensive analysis of genetic pleiotropy across more than four thousand GWAS, 90% of the genomic loci were associated with more than one biological domain (e.g., a locus associated with both a psychiatric and an immunological phenotype), and an even greater proportion of loci had multi‐trait associations within a biological domain (e.g., a locus influencing two or more psychiatric disorders) 79 . Since a locus may contain several genes and even more SNPs, multidomain associations at the gene level (63%) and SNP level (31%) were less abundant 79 . However, the extent of genetic overlap is higher when SNPs not yet identified at the genome‐wide significance level are also included78, 192, 197.

The assembly of well‐powered GWAS on psychiatric disorders (see Table 1) has enabled systematic comparisons of their unique and shared genetic architectures. Even though most common genetic variants for complex human phenotypes remain to be identified 61 , genetic overlap between two phenotypes can be investigated at the genome‐wide level by including the effects of all or a subset of SNPs. The most commonly applied tools for this purpose are polygenic risk scores (PRS)198, 199 and the bivariate extension of LD score regression 200 .

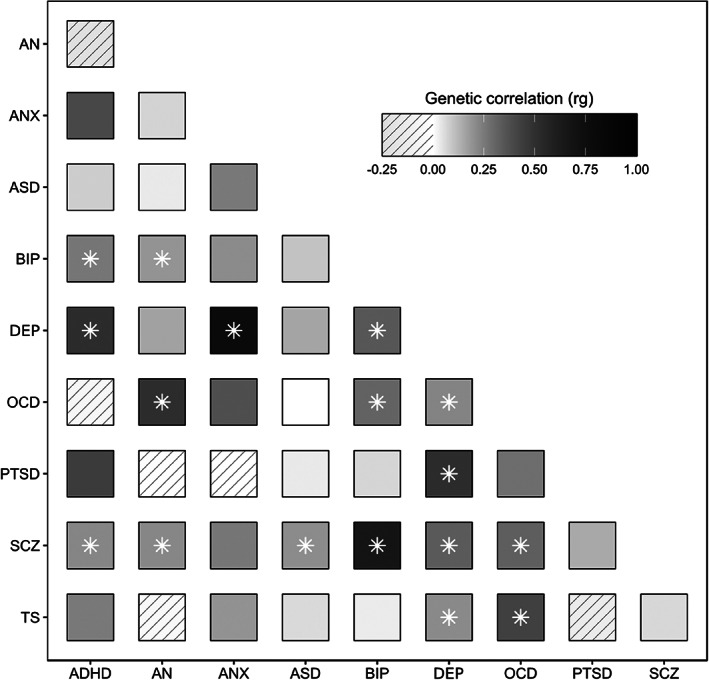

In line with previous findings of shared genetic risk between psychiatric disorders 201 , an analysis of GWAS data from 25 common brain disorders demonstrated substantial pairwise positive genetic correlations across psychiatric disorders, which exceeded that which could be reasonably explained by potential diagnostic misclassification 184 . In Figure 3, we provide an updated overview of pairwise genetic correlations between major psychiatric disorders using the most recent GWAS available.

Figure 3.

Pairwise genetic correlations between major psychiatric disorders estimated using LD score regression. Significant genetic correlations indicated by an asterisk. ADHD – attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder, AN – anorexia nervosa, ANX – anxiety, ASD – autism spectrum disorder, BIP – bipolar disorder, DEP – depression, OCD – obsessive‐compulsive disorder, PTSD – post‐traumatic stress disorder, SCZ – schizophrenia, TS – Tourette's syndrome.

In comparison, there are markedly fewer and smaller pairwise genetic correlations among neurological disorders 184 , and between neurological and psychiatric disorders, although there are a few exceptions184, 185, 202. This dissimilar pattern of pairwise genetic correlations among neurological and psychiatric disorders may indicate that the former represent more distinct genetic entities than the latter 184 . This is in line with the notion that neurological diagnostic categories have a stronger biological foundation. By contrast, genetic risk for psychiatric disorders evidently transcends diagnostic domains, and these disorders are more genetically interconnected. As observed for common genetic variants, rare CNVs and protein‐truncating variants also show a high degree of pleiotropy across the whole group of psychiatric disorders98, 203 and with other brain‐related traits such as epilepsy, developmental disorders and cognitive ability204, 205.

The emerging genetic data may be considered to be at odds with the current diagnostic classification systems17, 18, in which psychiatric disorders are considered categorically distinct from one another 206 . The genetic findings may thus be considered to support efforts to reconceptualize psychiatric nosology in a more dimensional framework206, 207, such as the proposed Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) 173 or Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) 174 .

Genetic risk for psychiatric disorders also overlaps with genetic variation in behavioral traits95, 208, such as the Big Five personality traits195, 209, general intelligence 86 , educational attainment 210 , subjective well‐being 211 , sleep patterns87, 212, and mental health profiles in healthy individuals 213 , indicating that genetic risk for mental illness is not categorically distinct from normality 206 .

A cross‐disorder GWAS analysis of eight psychiatric disorders using factor analysis and genomic structural equation modelling 214 indicated broader genetic domains that may underlie a higher‐order structure of psychopathology 215 . Using the same analytical approach, a recent GWAS analysis of 11 psychiatric disorders found evidence of four highly correlated groups of disorders 216 . The first group was characterized by compulsive behaviors (anorexia nervosa, OCD and Tourette's syndrome), the second group by internalizing symptoms (anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder), the third group by psychotic features (schizophrenia and bipolar disorder), and the fourth group by neurodevelopmental features (ADHD and autism spectrum disorder), surprisingly also including PTSD and problematic alcohol use 216 . Interestingly, the cross‐disorder GWAS analysis did not find clear evidence that an underlying generalized liability to develop psychopathology (the p factor 217 ) could adequately explain shared variance across psychiatric disorders 216 .

Cross‐disorder PRS analyses present a similar picture. In line with a dimensional model of psychopathology, patients with bipolar disorder with a history of psychotic symptoms had a higher schizophrenia PRS compared to those without such a history, which was not driven by the presence of cases with schizoaffective subtype 218 . Similarly, a history of manic symptoms in schizophrenia has been significantly associated with bipolar disorder PRS218, 219, indicating that genetic risk for mental illness influences clinical subphenotypes across diagnostic categories.

There is also increasing evidence of genetic heterogeneity among subtypes of mental disorders. For example, the genetic risk underlying childhood ADHD and ADHD persistent in adults is partially distinct, with a genetic correlation of 0.81 220 . A subsequent genetic dissection of three ADHD subgroups defined by the age at first diagnosis (childhood, adult or persistent ADHD) indicated further genetic differences, with the lowest pairwise genetic correlation (rg=0.65) between childhood and late‐diagnosed ADHD 221 . The ADHD subgroups also displayed different PRS associations with related traits and disorders, with late‐onset ADHD generally having the strongest associations, for example with higher risk of depression and insomnia, while childhood ADHD was most strongly associated with autism spectrum disorder 221 .

Analysis of bipolar disorder has also revealed genetic heterogeneity between subtypes, with a genetic correlation of 0.89 between type I and II136. In line with their clinical profiles, bipolar type II disorder is more genetically correlated with major depression (rg=0.69) than with schizophrenia (rg=0.51), while bipolar type I disorder is more genetically correlated with schizophrenia (rg=0.71) than with major depression (rg=0.30) 136 . These findings clearly indicate that mood and psychotic disorders exist on a continuum, both phenotypically 222 and genetically.

Evaluating patterns of genetic overlap between psychiatric disorders and other traits has also provided significant insights. This is particularly relevant for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, which may in some cases be difficult to differentiate diagnostically. While both disorders are associated with cognitive impairment, the cognitive deficits are generally more pronounced in individuals with schizophrenia 223 . In line with these phenotypic associations, genetic risk of both disorders extensively overlaps with cognitive function, but in a different manner, where most schizophrenia risk variants are associated with poorer cognitive performance, while there is a balanced mix of bipolar disorder risk variants associated with worse or better cognitive performance 178 . Hence, leveraging genetic data on related traits may help distinguish the genetic architectures of highly correlated psychiatric disorders, and point to differences in their etiologies.

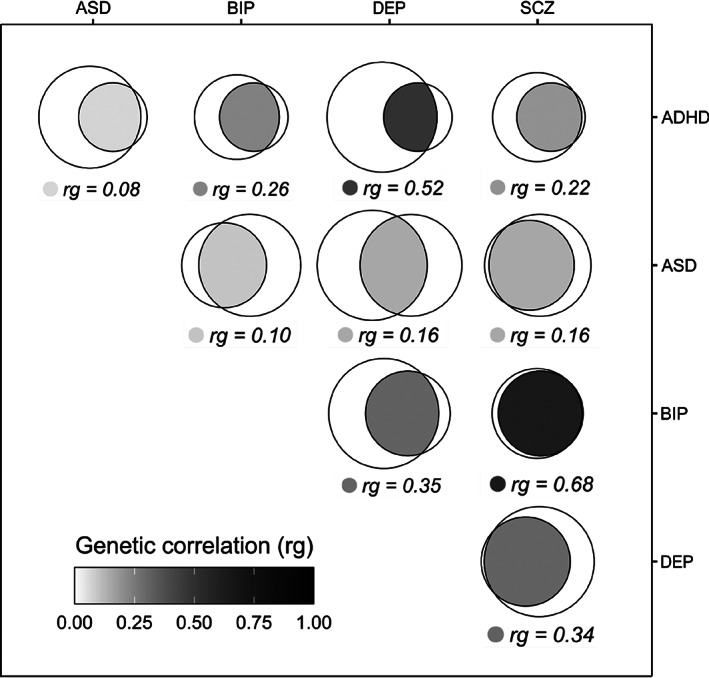

Additional work has indicated that the genetic overlap between psychiatric disorders is even more extensive than expressed by the pairwise genetic correlations78,138,176214,215, as depicted in Figure 4. A comprehensive analysis of the unique and shared common variant architectures between psychiatric disorders and between psychiatric disorders and behavioral phenotypes indicated substantial genetic overlap, with only a minority of trait‐specific variants, despite differences in genetic correlation 95 .

Figure 4.

Extensive overlap in common genetic variants between mental disorders beyond genetic correlation. The fraction of unique and shared genetic architecture between pairs of the five psychiatric disorders is estimated using MiXeR 78 . The genetic correlations are estimated using LD score regression 200 . The disorders represented by the left circles of the Venn diagrams are listed in the horizontal axis, and right circles are represented by disorders listed in the vertical axis. ADHD – attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder, ASD – autism spectrum disorder, BIP – bipolar disorder, DEP – depression, SCZ – schizophrenia.

Widespread genetic overlap despite divergent genetic correlations indicates that psychiatric disorders are predominantly influenced by a set of highly pleiotropic genetic variants which impact the risk of each disorder to a different degree and, in some cases, in different directions 138 . This insight is consistent with an integrated conceptualization of the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders and related traits, in which multiple, overlapping neurobiological mechanisms and systems are implicated in the development of both mental disorders and normative mental traits 95 . However, the extent to which indirect and direct genetic effects differently contribute to pleiotropy across highly polygenic phenotypes such as psychiatric disorders is currently unknown, warranting more data from family‐based studies.

The recent accumulation of large publicly available genotyped neuroimaging samples through international initiatives such as ENIGMA 224 and population studies such as UK Biobank 225 has provided new opportunities to study the shared genetic foundations of human brain structure and psychiatric disorders. Global measures of brain structure, such as cortical thickness and surface area, have been shown to be highly heritable, with SNP‐heritability estimates ranging from 25 to 35% 226 . However, they have been found to be 4‐5 times less polygenic than mental disorders, indicating fundamental differences in their genetic architectures 227 .

In particular, the genetic relationship between schizophrenia and brain structural phenotypes has been extensively studied227, 228, 229, 230, 231, 232, 233, 234, 235, owing to the well‐powered GWAS data on that disorder. Despite well‐established findings of subtle brain structural abnormalities in schizophrenia236, 237, 238, the genetic correlations between neuroimaging measures and schizophrenia have been absent or low228, 229. Yet, despite a lack of genetic correlation, cortical thickness and surface area are predicted to share almost all their common genetic variants with schizophrenia, while a large majority of genetic variants associated with schizophrenia are not associated with cortical structure 227 . The difference in the proportions of overlapping genetic variants is explained by the large difference in polygenicity of the brain imaging phenotypes and schizophrenia 227 . Further, the apparent contradiction of substantial genetic overlap despite minimal genetic correlations is likely due to mixed directions of effect among the shared variants, which cancel out the overall genetic correlation 138 . Indeed, multiple specific genetic variants have been discovered in recent years which are shared between schizophrenia and various brain morphology measures 230 , including cortical thickness and surface area 227 , volume of subcortical regions231, 232, 233, intracranial volume 231 , cerebellar volume 234 , and brainstem structures 235 . Taken together, the emerging genetic data indicate a complex genetic relationship between brain structural measures and schizophrenia, and it remains unclear to what extent imaging phenotypes can serve as endophenotypes that capture underlying mechanisms with greater biological specificity.

An important limitation of most studies of genetic overlap is the ambiguity regarding the direction of causality and whether the detected overlap implies shared biological mechanisms. A given shared genetic association may reflect so‐called “horizontal” or biological pleiotropy, in which a variant influences two phenotypes through independent molecular mechanisms; “vertical” or mediated pleiotropy, in which a variant influences a trait, and this trait causally affects another trait; or “spurious” pleiotropy, in which a variant is falsely assumed to influence two traits, for example due to statistical association between two nearby variants in strong LD with each other 239 .

Mendelian randomization attempts to directly address the question of causality by testing for evidence of a causal relationship between the genetic factors associated with a given “exposure” and a given “outcome” (vertical pleiotropy). For example, Mendelian randomization has provided several intriguing findings regarding the link between inflammation and the etiology of psychiatric disorders. Genetically determined level of C‐reactive protein was shown to have a potentially protective effect on schizophrenia risk 240 . This finding was replicated in a recent analysis 241 using the most recent schizophrenia GWAS 64 , although a significant causal relationship was only present when controlling for body mass index and circulating interleukin 6 (IL‐6) and its receptor 241 .

In another Mendelian randomization study, IL‐6 itself has been shown to exhibit a potentially causal association with grey matter volume across multiple cortical regions, and to interact with a network of co‐expressed genes in the medial temporal gyrus which were found to be differentially expressed in schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder and epilepsy 242 . IL‐6 receptor levels have also been implicated in the risk for depression 243 and suicidality 244 , although less is known about putative causal relationships with bipolar disorder.

Interestingly, in Mendelian randomization studies focusing on immune disorders rather than biomarkers, several psychiatric disorders where found to have a causal effect on immune disorders, rather than the other direction, including a causative effect of major depressive disorder on asthma and of schizophrenia on ulcerative colitis 245 . Nonetheless, while these findings have contributed to the growing evidence base for a possible causal association between inflammatory phenotypes and psychiatric disorders, Mendelian randomization is still based on statistical inference, and it is important to control for the extensive “horizontal” pleiotropy observed between mental traits and disorders. Thus, the validity of Mendelian randomization findings require further investigations via in vitro, in vivo, and interventional studies.

The assembly of large‐scale biobanks harboring rich phenotypic data can be leveraged to discover connections between genetic markers and traits, for example using the phenome‐wide association study (PheWAS) approach to systematically investigate trait‐associations with a given PRS 246 . A PheWAS study investigating the link between schizophrenia PRS and electronic health record data in 106,160 patients across four large US health care systems in the PsycheMERGE Network reported that schizophrenia PRS was not only associated with psychiatric phenotypes such as diagnosis of schizophrenia and substance use, but with several non‐psychiatric phenotypes, including a negative association with obesity 247 . The inverse genetic association between schizophrenia risk and obesity has been confirmed by other genetic studies 193 , indicating that the increased body mass index observed in schizophrenia patients is likely due to non‐genetic factors such as antipsychotic medication.

Another PheWAS study on 325,992 participants in the UK Biobank reported significant associations between schizophrenia PRS and multiple psychiatric and non‐psychiatric conditions and measures, including poorer overall health ratings, more hospital inpatient diagnoses, and more specific disorders (musculoskeletal, respiratory and digestive diseases, varicose veins, pituitary hyperfunction, and peripheral nerve disorders) 248 . Although some of these PRS trait‐associations may be consequences of having schizophrenia or related psychiatric disorders, the studies indicate that the genetic risk for schizophrenia also affects a wide range of somatic conditions.

Finally, a similar PheWAS study of 382,452 patients in the PsycheMERGE Network investigated the relationship between depression PRS and 315 clinical laboratory measurements 249 . A replicable yet modest association was found between higher polygenic burden of depression risk variants and increased levels of white blood cells, even after controlling for a diagnosis of depression and anxiety. In line with a neuroinflammation model 250 , a potential causal link between white blood cells and depression was supported by mediation and Mendelian randomization analyses, indicating that higher genetic risk underlying depression may activate the immune system, possibly contributing to the risk of developing the disorder 249 .

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

Despite significant progress over the last decade in our understanding of the genetic foundations of psychiatric disorders, clinical translation remains conspicuous by its absence. Nevertheless, genetic‐based prediction and stratification offers a promising avenue towards improved patient outcomes in the coming decades 251 . Chip‐based genotyping is relatively affordable, while the price for whole‐genome sequencing continues to fall 252 . What's more, genetic testing only needs to be performed once in a person's lifetime, and genotyping data can be used on multiple occasions for multiple different purposes. However, several major challenges need to be overcome before this translates into a clinically viable tool which benefits patients, including improving predictive accuracy, enabling discrimination between diagnostic categories or clinically actionable decisions, ensuring equal predictive performance across ancestral groups, and guarding against significant ethical concerns.

The main focus of research into genetic‐based prediction has centered around PRS. This uses existing genetic data to construct an individualized risk score for a given trait or disorder, calculated as the sum of pre‐defined risk alleles weighted according to each allele's effect on the phenotype, typically estimated by a GWAS 253 . The accumulation of massive case‐control samples alongside PRS‐method improvement has recently led to the development of PRS‐based tools with clinically meaningful predictive accuracy in several common medical conditions 254 , including cardiovascular disease255, 256, type 1 diabetes mellitus 257 and cancers256, 258. However, even considering the improved predictive performance of the latest PRS tools, current PRSs for major psychiatric disorders are far from achieving equivalent levels of prediction259, 260.

For schizophrenia, which possesses the most well‐powered GWAS to date, the best performing PRS method explained just 8.5% of the variance in liability for the disease, falling to 7.3% when non‐European ancestry cohorts were included 64 . The insufficient predictive accuracy of the schizophrenia PRS is further demonstrated by an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.72 64 , while an AUROC above 0.8 is considered to indicate good discriminative ability 253 . Other psychiatric disorders lag even further behind, with the AUROC for major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder PRS being 0.57 and 0.65, respectively65, 137. At the current levels of explained variance, this means that most individuals in the top PRS centiles for a given mental disorder will not develop that disorder and the majority of people who do develop mental disorders have PRS centiles closer to the median 259 . As a result, current PRSs for psychiatric disorders show poor potential for screening purposes in the general population, and do not yet have a role in genetic counselling. PRS has currently a larger potential for screening of some common medical conditions254,256, as exemplified by the MyGeneRank application 261 .

Since the predictive accuracy of PRS is also dependent on the prevalence of the disorder in the sample tested, the utility of psychiatric PRSs will vary depending on the context in which they are applied 262 . Although psychiatric disorder PRSs are far from being able to accurately predict a given disorder in the general population 259 , they may provide greater clinical utility if used in clinical populations for which the pre‐test probability that an individual will experience a mental disorder is higher. For example, PRS may be useful to predict risk of developing psychosis in individuals who carry large‐effect rare variants, such as carriers of 22q11.2 deletion. Approximately 20‐25% of 22q11.2 deletion carriers develop schizophrenia263, 264. Among carriers of 22q11.2 deletion, schizophrenia prevalence was 9% vs. 33% in the lowest and highest deciles of the schizophrenia PRS, respectively 124 , indicating potential utility for informing clinical decision‐making in the near future for this patient group. Among individuals at clinical high risk of developing psychosis followed over a 2‐year period, addition of schizophrenia PRS to an existing calculator slightly improved prediction of psychosis 265 . Use of disorder‐specific PRS at this stage may be useful for informing decisions relating to the level of follow‐up required or whether or not to initiate psychotropic medication. This may also be relevant for other patient groups, such as those presenting with depressive symptoms, for whom the clinical trajectory is highly variable and is associated with differences in genetic risk for major depressive disorder 266 .

There is currently only limited evidence to support the hypothesis that disorder‐specific PRSs are associated with treatment response for either depression or psychosis267, 268. Alternatively, it may be possible to develop PRSs tailored for specific treatment decisions. High rates of non‐response among patients taking both antidepressant and antipsychotic medications mean that tools which effectively predict treatment response could have a significant impact on patient outcomes269, 270. For example, the early identification of patients with treatment‐resistant schizophrenia requiring clozapine is a prime candidate for a treatment‐focused PRS. Approximately 30‐40% of individuals with schizophrenia do not respond to two first‐line antipsychotics, but half of this group respond to clozapine 271 . A case‐case GWAS of treatment responding vs. resistant patients found that treatment resistance was minimally but detectably heritable (h2 SNP=1‐4%) and that a PRS derived from this GWAS was weakly predictive of clozapine use in an independent sample 82 .

Genetic prediction may also be helpful for identifying individuals who do not respond to pharmacological treatment whatsoever or are likely to develop specific side effects related to psychotropic medication 272 . In the coming years, large‐scale, genotyped prescription registries such as FinnGen 273 , in addition to deeply phenotyped clinical samples, will offer new opportunities to investigate the genetics of non‐response and adverse drug reactions.

As the predictive ability of PRS largely depends on the power of the genetic study it is derived from, the performance of PRS is likely to improve in the coming years due to significant increases in sample sizes, better phenotyping procedures and further methodological refinements96, 254, 260. However, PRS performs poorly when applied to admixed individuals or individuals of other ancestries than the cohort the PRS was initially derived from 55 . Since most GWAS are based on European individuals, the poor cross‐ancestry performance of PRS represents a major challenge to ensure equitable health benefits of its potential clinical implementation.

The high degree of genetic and symptomatic overlap across diagnostic categories and the lack of “gold standard” diagnostic tests also represent a unique challenge within psychiatry as opposed to other medical specialties, for which screening is already a part of routine clinical pathways. Given that the choice of psychotropic medication is often driven by diagnosis, a lack of discriminatory ability across disorder‐specific PRSs may limit their clinical utility. This feeds into a wider question about the validity of the diagnostic categories themselves. Psychiatric disorders are highly heterogenous and overlapping, both clinically and neurobiologically, which may limit the predictive capability of PRSs based on the current diagnostic criteria274, 275. This represents somewhat of a “catch‐22” scenario, since PRS performance is dependent on statistical power and the largest samples to date are based on the prevailing diagnostic system, with limited phenotypic data available for large proportions of the subcohorts comprising these large‐scale GWAS 206 . With increasing recognition of the need to prioritize more deeply phenotyped samples, this is likely to shift in the coming years.

It is also possible that the genetic overlap across diagnostic categories could be leveraged to improve prediction of individuals with psychiatric disorder compared to healthy controls, even if this is at the cost of discriminating between different diagnoses. A recent study combined multiple disorder‐specific PRSs to improve prediction of mood disorders, anxiety, ADHD, autism spectrum disorder and substance use disorders 276 . This raises the possibility that distinct types of PRS may be applied in the future depending on the clinical question, either to maximize prediction of psychiatric disorder as opposed to its absence, or to maximize discrimination across diagnostic categories, alternative subphenotypes, or treatment options.

While psychiatric PRS is still some way from being applied clinically, advances in non‐psychiatric PRS may provide more immediate benefits for individuals with psychiatric disorders. Cardiovascular disease and its metabolic risk factors are significantly more prevalent among psychiatric patients and are the single largest cause of death in these patients 277 . A study in the UK Biobank showed that applying a cardiovascular disease PRS in addition to standard risk prediction for people at intermediate risk could prevent 7% more cardiovascular disease events than the standard screening approach 278 . So, while it is feasible to incorporate PRS for cardiovascular disease into routine clinical practice for the general population, this may provide particular benefit for psychiatric patients 278 .

Despite the fact that PRSs are currently not deemed to be clinically useful, patients can already acquire their own PRS profile themselves at relatively low cost through direct‐to‐consumer genotyping companies. Although these companies do not routinely offer PRS for psychiatric disorders, individuals can download their own raw genotypes and use complementary websites to compute PRS for additional phenotypes of their choice. While this may help to democratize access to health information and increase patients' ability to take ownership for their health, these services are variably regulated across countries 279 , and the information provided to help consumers accurately interpret their results varies greatly 280 . Given the common misconception that genetic testing is deterministic, this could leave consumers at risk of misinterpreting their results, which may lead to harmful outcomes.

Moreover, interpreting PRS results requires an understanding of the difference between relative risk and absolute risk, which may not be intuitive. For example, in the latest schizophrenia GWAS 64 , being in the top PRS centile was only associated with an odds ratio of 5.6 relative to the rest of the sample. Hence, an individual in the top PRS centile for schizophrenia without any other risk factors is more likely to not develop the disease than get the disorder, due to the low lifetime risk of schizophrenia.

A recent news article described a particularly concerning example of consumer use of PRS, in which a couple used a company called Genomic Prediction Inc. to perform PRS‐based screening of embryos derived by in vitro fertilization 281 . The couple then used a third‐party service to compute PRS for schizophrenia and intelligence and selected their embryo based on these scores. Not only does this raise major ethical concerns given the association with eugenics and ableism, but the fact that the PRS for schizophrenia is associated with positive traits such as increased openness to new experiences 195 and creativity 196 emphasizes that selection based on tools with limited predictive ability for traits which are still poorly understood and subject to stigma and discrimination could result in unintended and unwanted consequences282, 283, 284. Researchers affiliated with Genomic Prediction Inc. have since constructed a polygenic health index by combining PRS for 20 impactful disease conditions, including schizophrenia 285 .

Overall, the rapid methodological developments, increasing availability, and public and clinical interest in genetic prediction tools highlight the need for greater oversight and regulation in this emerging new interface between science, commerce, and the rights of the individual. Given the impact on medicine, implementation of PRS at different levels (e.g., embryo selection, risk screening in the population, informing clinical decision‐making) requires a broader debate in society and the general public.

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR PROGRESS AND FUTURE IMPACT

Despite the substantial progress in the discovery of genetic variants influencing risk of mental illness in the last decade, psychiatric genetics is still in its early stages, and the genetic findings have not yet been translated into better mental health care. Most genetic risk variants affecting major psychiatric disorders remain to be uncovered (see Figure 2), and several psychiatric disorders still lack sufficiently powered genetic data. To maintain progress in the field, it is necessary to continue assembling large‐scale samples of people with psychiatric disorders, including measures of the progression and severity of illness and treatment response. To this end, international cooperation is the best way forward224, 286, with support from national cohorts such as UK Biobank 225 , FinnGen 273 , iPSYCH 287 and deCODE 288 .

It is increasingly recognized that integrated analysis of the full range of genetic variation125, 289 is necessary to provide a comprehensive understanding of how genetic variants influence risk of illness and underlie different clinical profiles, warranting greater use of sequencing technologies. Moreover, the present genetic findings have disproportionally been based on individuals of European descent, and are only partially transferrable to other ancestral groups, due to differences in genetic and environmental contexts168, 169, 172, resulting in poorer performance of genomic prediction tools55, 290, 291. To ensure that the expected health benefits from the developments in human genetics are equitable, it is imperative to prioritize ancestral diversity of both genomic and functional genomic data resources in the coming years, which requires a concerted global effort167, 168, 169. New initiatives have been established to improve recruitment of diverse samples167, 292, 293 and to develop better trans‐ancestry prediction methods, with promising results in several complex human disorders294, 295, 296.

Psychiatric disorders are multifactorial. The impact of individual genetic risk depends on the psychosocial setting of the individual, and this must be taken into account to ensure further progress in the field. To obtain a more complete understanding of the underlying causes of psychiatric disorders and account for the substantial individual variation, deeper phenotyping and incorporation of demographic and environmental data is needed. It is, therefore, necessary to go beyond unidimensional case‐control studies based on diagnostic categories and adopt a multi‐modal analytical framework, that incorporates clinical characteristics, genetic information, blood biomarkers, neuroimaging measures, electronic health record data, lifestyle factors, demographic data and environmental factors in a systematic manner. This will be expensive and requires extensive data harmonization, which again calls for coordinated, international collaborations 297 .