Abstract

Objective:

Enlarged deep medullary veins (EDMVs) in patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) occur during the early disease course and may provide compensatory venous drainage for brain regions affected by the leptomeningeal venous malformation (LVM). We evaluated the prevalence, extent, hemispheric differences, and clinical correlates of EDMVs in SWS.

Methods:

Fifty children (median age: 4.5 years) with unilateral SWS underwent brain MRI prospectively including susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI); children ≥2.5 years of age also had a formal neurocognitive evaluation. The extent of EDMVs in the affected hemisphere was assessed on SWI by using an EDMV hemispheric score, which was compared between patients with right and left SWS and correlated with clinical variables.

Results:

EDMVs were present in 89% (24/27) of right and 78% (18/23) of left SWS brains. Extensive EDMVs (score >6) were more frequent in right (33%) than in left SWS (9%; p=0.046) and commonly occurred in young children with right but not with left SWS. Patients with EDMV scores >4 (n=19) had rare (less than monthly) seizures, while 35% (11/31) of patients with EDMV scores ≤4 had monthly or more frequent seizures (p=0.003). In patients with right SWS and at least two LVM-affected lobes, higher EDMV scores were associated with higher IQ (p<0.05).

Conclusions:

Enlarged deep medullary veins are common in unilateral SWS, but extensive EDMVs appear to develop more commonly and earlier during the disease course in right hemispheric SWS. Deep venous remodeling may be a compensatory mechanism contributing to better clinical outcomes in some patients with SWS.

Keywords: Sturge-Weber syndrome, magnetic resonance imaging, cerebral veins, seizures, cognitive functions, remodeling

Introduction

Sturge–Weber syndrome (SWS) is a congenital neurocutaneous disorder characterized by a facial capillary malformation and leptomeningeal venous malformation (LVM); vascular glaucoma is also present in about half of the cases (Bodensteiner & Roach, 2010). The etiology of SWS involves a somatic activating p.R183Q pathogenic variant in the GNAQ gene in most affected patients (Shirley et al., 2013). The radiological hallmark of SWS brain involvement is leptomeningeal enhancement on post-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) variably accompanied by enlarged deep veins and choroid plexus, focal brain atrophy, and calcifications (Hu et al., 2008; Lo et al., 2012; Pilli et al., 2017a).

SWS brain involvement is confined to one hemisphere in >80% of the cases, and clinical course and neurocognitive outcome are highly variable (Bosnyak et al., 2016; Day et al., 2019a). Initial neurological manifestations include seizures that may be accompanied by focal neurological symptoms (such as hemiparesis, visual field impairment), cognitive impairment, and learning disability. Medical treatment often includes antiseizure drugs; retrospective studies suggested the potential benefit of pre- or post-symptomatic low-dose aspirin treatment in children with SWS (Lance et al., 2013; Day et al., 2019b). Aspirin may prevent the progression of impaired cerebral blood flow and hypoxic-ischemic neuronal injury; however, no prospective studies have been completed to support these observations. Patients with unilateral SWS and intractable seizures can benefit from resective epilepsy surgery, especially when performed during the early disease course (Wang et al., 2021). However, some children with SWS show good neurocognitive outcome despite extensive unilateral brain involvement, presumably due to early, effective functional reorganization in the contralateral (unaffected) hemisphere (Behen et al., 2011; Bosnyak et al., 2016).

LVM in the SWS-affected brain is often associated with ipsilateral enlarged deep medullary and subependymal veins. Supratentorial medullary veins originate below the cortical gray matter, pass through deep white matter and converge on subependymal veins around the lateral ventricles in a wedge-shaped pattern (Lee et al., 1996; Taoka et al., 2017). Enlargement of these deep veins in SWS is analogous to developmental venous anomalies that can provide collateral blood flow following the occlusion or insufficient development of normal venous pathways (Saito et al., 1981; Lee et al., 1996). As a result, these deep veins can provide a compensatory (centripetal) venous drainage of the cortex and subcortical white matter toward the deep venous system in SWS (Bentson et al., 1971; Parsa, 2008). However, the potential clinical correlates of these enlarged deep veins in SWS have not been clarified.

MRI with susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) has superior sensitivity to detect and evaluate both normal and enlarged deep medullary veins (EDMVs) in SWS and other brain disorders (Hu et al., 2008; Ao et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022). SWI is a 3D, fully velocity-compensated gradient recalled–echo sequence that exploits deoxyhemoglobin as an intrinsic contrast agent, thus enabling assessment of small cerebral veins with exquisite details without external contrast administration (Haacke et al., 2009). In recent studies, we reported longitudinal SWI data demonstrating that small medullary veins can expand during the early disease course of SWS (Pilli et al., 2017b; John et al., 2018); in the few documented cases of early deep vein expansion, this occurred in the right hemisphere. In one child, a dramatic early deep vein expansion was associated with reversal of initial metabolic abnormalities and good neurocognitive outcome despite extensive right hemispheric LVM (John et al., 2018). These preliminary data supported the notion that EDMVs may provide an effective compensatory drainage of the venous blood to the deep venous system.

In the present study, we evaluated EDMVs in children with unilateral SWS. Specifically, we estimated and compared the extent of such veins in right and left hemispheric SWS and tested the hypothesis that extensive EDMVs are associated with better seizure control and/or cognitive functions. As a secondary aim, we also tested if aspirin treatment is associated with the extent of EDMVs or other clinical and MRI variables.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects.

All data for this study were collected prospectively from children with SWS who participated in a clinical research study between 2004 and 2021 at the Children’s Hospital of Michigan. The protocol was approved by the Wayne State University Human Investigation Committee, and a written informed consent form was signed by parents or guardians. Children older than 13 years of age signed a written assent form. Inclusion criteria were the following: (a) unilateral SWS detected by clinical MRI, defined as the presence of unilateral LVM on post-contrast MRI, with or without a facial port-wine birthmark; (b) age of 1–17 years; (c) good quality SWI images available for evaluation of SWS brain abnormalities. Exclusion criteria were: (a) bilateral SWS brain involvement on MRI and (b) history of epilepsy surgery. In children who had a history of epilepsy, clinical data collected from medical charts and parent interviews included age at seizure onset, seizure frequency, duration of epilepsy, number of antiseizure drugs. Concurrent aspirin treatment was recorded for all subjects. For assessing clinical seizure frequency in the one year before the study, a scoring system described previously (Bosnyak et al., 2016; Luat et al., 2018) was used as follows: 0 – no seizure in the last 1 year; 1 – one to 11 seizures per year (i.e., at least yearly but less than monthly seizures); 2 – one to 4 seizures per month; and 3 – >4 seizures per month (i.e., at least weekly seizures, in average).

MRI acquisition.

All MRIs were done at least 24 hours after the last clinical seizure to minimize the potential confounding effect of seizure activity on vascular dilatation/engorgement or blood oxygenation/deoxygenation levels potentially affecting the SWI signal in the veins. MRI acquisition parameters have been described in our previous study (Pilli et al., 2017a). In brief, the MRI studies were performed on a Siemens Sonata 1.5 T (n=23 patients; before 2010) or a MAGNETOM Verio 3T scanner (n=27; 2010–2021) (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) located at the Harper University Hospital, Wayne State University. On both scanners, MRI acquisition included a native (non-contrast) axial T1 3-dimensional magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (1mm slice thickness), an axial fluid attenuated inversion recovery, an axial T2-weighted turbo spin-echo acquisition, SWI, followed by post-gadolinium T1 images. Young children underwent moderate sedation to make sure that no significant motion artifacts occur. SWI parameters were: (1) 1.5 T scanner: a 3-dimensional fully balanced gradient-echo sequence with flip angle 20°; echo-planar imaging factor 5; acquisition matrix 512×256×48; field of view 256×256×96 mm3; voxel size 0.5×0.5×2 mm3; TR/TE 89/40ms; bandwidth 160Hz/pixel. (2) 3 T scanner: field of view 224×168×128 mm; base resolution 448; voxel size 0.5×0.5×1 mm3; partition number 96; TR/TE 30/18ms; bandwidth 90~120Hz/pixel, 2× accelerated GRAPPA paralleling imaging with 24 reference lines, and 6/8 partial Fourier along phase encoding.

MRI image analysis.

The extent of LVM was established by reviewing the post-contrast MR images, and the number of lobes (range: 1–4) affected by leptomeningeal contrast enhancement was recorded for each patient. The extent of atrophy was assessed on T2/FLAIR images (comparing each lobe in the SWS-affected hemisphere to the contralateral corresponding unaffected lobe) and the number of atrophic lobes (range: 0–4) was recorded. SWI images were processed offline using SPIN (Signal Processing in NMR), an in-house software (Haacke et al., 2007). SWI minimum intensity projection (MIP) images were generated, and the extent of EDMVs were determined by two investigators (C.J, A.K.) in five major deep venous regions of the affected hemisphere: in the frontal, central, parietal, temporal, and occipital white matter. For this, each SWI MIP image was displayed on a screen, and the investigators reviewed EDMVs in each of the regions by comparing the SWI-visualized medullary veins between homotopic regions in the affected and unaffected hemispheres, and their extent in the affected (left or right) hemisphere was scored based on consensus as follows: score 0: no EDMVs, score 1: few (1–2) EDMVs in the region, score 2: several (3–5) EDMVs in the region; score 3: extensive (≥6) EDMVs in the region (see examples for regional scores on Figure 1); thus, when combining the values from the five regions, the total hemispheric EDMV score ranged between 0 and 15.

Figure 1.

Examples of the extent of enlarged deep medullary veins (EDMVs) in the central (A), frontal (B), parietal (C), and temporal or occipital (D) venous regions. All venous abnormalities are shown in the right hemisphere for an easier comparison, and images from left SWS have been flipped for this purpose. For each image on panels A-C, only one region is framed (red frame in central, orange frame in frontal, yellow frame in parietal regions) even if additional EDMVs are present in other venous regions. On panel D, temporal lobe veins are framed with blue (scores 1–3) and occipital lobe veins with purple (score 1 only).

The scoring was repeated by the same investigators 1 week later on 15 randomly selected deidentified scans to assess test-retest reliability.

Neurocognitive testing.

Of the 50 patients, 39 were at least 2.5 years old at the time of MRI and had their cognitive functioning evaluated by the Wechsler Pre-school and Primary Scale of Intelligence-III (WPPSI-III; children ages 2 years 6 months –7 years 3 months) or the Wechsler Intelligence Scales for Children-III (WISC-III; children older than 7 years 3 months) within one week of their prospective MRIs. Both Wechsler scales provided indices of cognitive functioning as expressed by verbal IQ (VIQ) and performance IQ (PIQ). Since all children had unilateral SWS, often associated with large VIQ-PIQ differences, full-scale IQ was difficult to interpret, therefore, it was not used in the current study.

Statistical analysis.

Normality distribution tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed non-normal distributions for several clinical and MRI variables. Therefore, statistical analysis was performed using non-parametric tests, such as the Mann-Whitney U test for independent group comparisons, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired comparisons, and the Spearman’s rank correlation. Comparisons of categorical variables were performed using the Fisher’s exact test. Test-retest reliability of the EDMV scores was assessed by intraclass correlation. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0. P values below 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Clinical variables.

Fifty children with unilateral SWS (32 girls and 18 boys) fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The median age was 4.5 years, and 27 had right and 23 left SWS brain involvement. None of the clinical variables were different between the right and left hemispheric SWS subgroups (Table 1). In the 39 patients, where WPPSI-III or WISC-III were performed, IQ measures also did not differ between left and right SWS. None of the clinical and MRI variables showed significant gender differences.

Table 1.

Clinical and MRI variables in patients with right and left SWS.

| Variables | Right SWS (n=27) | Left SWS (n=23) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Clinical | |||

| female/male ratio | 17/10 | 15/8 | 0.87 |

| age (years); median | 4.6 [2.8–9.4] | 4.5 [2.4–12.7] | 0.54 |

| history of epilepsy; n | 24 (89%) | 22 (95%) | 0.61 |

| age at epilepsy onset (years); median | 0.8 [0.4–1.5] | 0.6 [0.3–1.6] | 0.54 |

| duration of epilepsy (years); median | 2.9 [1.5–5.5] | 2.5 [1.0–9.3] | 0.76 |

| seizure frequency score; median | 1 [0–1] | 1 [0–2] | 0.33 |

| current anti-seizure drug(s); median | 1 [1–2] | 1 [1–2] | 0.83 |

| current aspirin treatment; yes/no | 7/19 | 9/14 | 0.54 |

| VIQ; median | 96 [76–106] | 92 [76–102] | 0.48 |

| PIQ; median | 83 [66–97] | 80 [66–93] | 0.53 |

|

| |||

| MRI | |||

| Magnet strength: 1.5T/3T; n | 13/14 | 10/13 | 0.78 |

| LVM extent (affected lobes); median | 3 [2–4] | 3 [2–4] | 0.41 |

| LVM affected >1 lobe; n | 21 (78%) | 20 (87%) | 0.79 |

| EDMVs present; n | 24 (89%) | 18 (78%) | 0.31 |

| EDMV scores; median | 4 [2–7] | 3 [1–5] | 0.19 |

| EDMV score >6; n | 9 (33.3%) | 2 (8.6%) | 0.046 |

Numbers in brackets indicate the interquartile range for medians. IQ measures were available in 39 patients (age ≥2.5 years; 22 right and 17 left SWS). P values refer to non-parametric group comparisons (Fisher’s exact test for categorical and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous or ordinal variables). Abbreviations: VIQ: verbal IQ, PIQ: non-verbal IQ (from WPPSI-III or WISC-III); LVM: leptomeningeal venous malformation; EDMV: enlarged deep medullary veins

Effect of MR magnet strength.

Distribution of left and right SWS was similar on 1.5 and 3 T MR magnets (Table 1). Likewise, neither clinical variables nor extent of LVM or EDMV scores differed in patients scanned on 1.5 vs. 3 T magnets (p>0.1 in all comparisons). Therefore, data obtained on the two scanners were combined in all subsequent analyses.

Test-retest reliability of EDMV scores.

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) indicated excellent test-retest reliability for the hemispheric EDMV scores (ICC=0.96, 95%CI: 0.89–0.99, p<0.001).

MRI variables in left and right SWS.

The number of lobes affected by LVM was similar in the left and right SWS subgroups (p=0.39) (Table 1). EDMVs were found in a total of 42 patients (84%), including 24 (89%) in right and 18 (78%) in left SWS (p=0.31). Extensive EDMVs (scores >6, indicating EDMVs present in at least 3 regions, see examples on Figure 2) were more common in right (9/27, 33.3%) than in left SWS (2/23, 8.6%) (p=0.046).

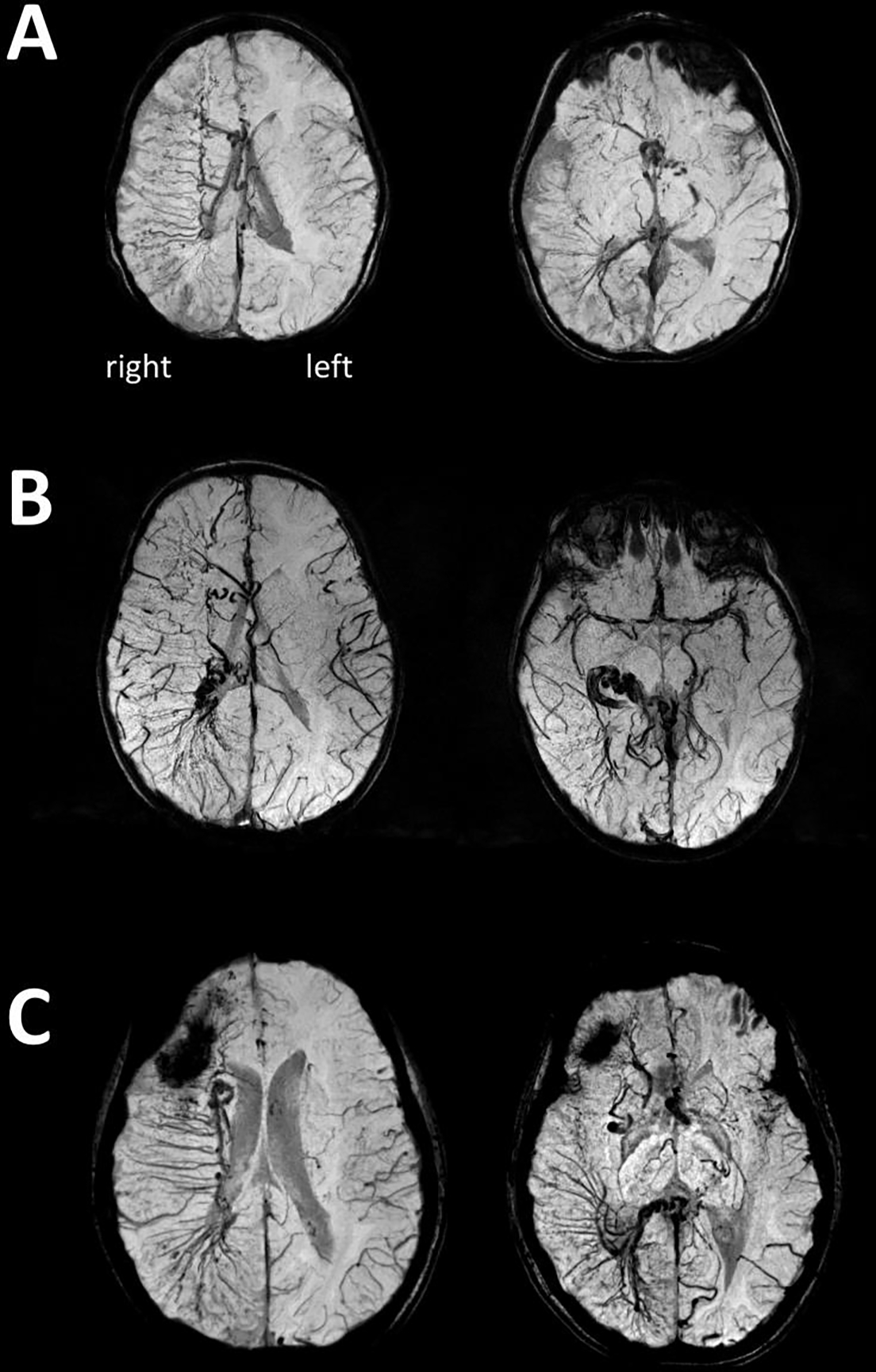

Figure 2.

Three examples of extensive right hemispheric enlarged deep veins (EDMVs) as shown by SWI minimum intensity projection images of a: (A) 2.4-year-old child, (B) 4.4-year-old child, and (C) 7.9-year-old child. All three children developed well cognitively and had only rare seizures (frequency score 0 or 1) despite extensive right hemispheric involvement. The first images show frontal, central, and parietal EDMVs, while the second images are from a lower plane showing temporo-occipital and/or inferior frontal EDMVs. Enlarged subependymal veins are also visualized. On panel C, the dark area in the right frontal region corresponded to a calcified region.

EDMV scores showed a positive correlation with age in the left SWS group (Spearman’s rho [r]=0.48, p=0.02) but no correlation in the right SWS subgroup (Figure 3). As Figure 3 illustrates, extensive EDMVs were present in 6 young children (age ≤8 years) with right SWS, but in none of those with left SWS below 12 years of age.

Figure 3.

(A) Age-related increase in enlarged deep medullary vein (EDMV) scores in left hemispheric SWS (Spearman’s rho=0.48, p=0.02). (B) In patients with right SWS, age was not associated with the EDMV scores (rho=0.03, p=0.89); note that 6 patients with right SWS (but none with left SWS) had high EDMV scores (>6) already before 8 years of age.

Associations between EDMVs, the extent of LVM, and the extent of atrophy.

While the extent of LVM was not different in those with vs. without EDMV (p=0.14), EDMV scores showed a positive correlation with the extent of LVM in both left SWS (r= 0.56, p=0.006) and right SWS (r=0.38, p=0.05). While most EDMVs occurred in LVM-affected lobes, EDMVs were also observed in non-LVM-affected lobes in 9 patients (18%), most commonly seen in the frontal lobe white matter (n=5), where LVM affected the nearby parietal area. Unlike LVM extent, the extent of atrophy did not correlate with EDMV scores (r=0.19, p=0.19 in the whole group). Figure 4 shows representative T2, FLAIR, post-contrast T1 and SWI MIP images are shown in a patient with extensive right hemispheric EDMVs, associated with mild atrophy in the parietal and frontal lobes.

Figure 4.

Representative axial T2 (A), FLAIR (B), post-contrast T1 (C), and SWI MIP (D) images of a child with right hemispheric SWS associated with extensive enlarged deep medullary veins (EDMVs). These veins are best visualized by SWI, which also shows the extent of posterior LVM as well as enlarged subependymal veins on the right side. T2 and FLAIR images show atrophy of the affected parietal and frontal lobes and also visualize portions of enlarged subependymal veins and choroid plexus. The post-contrast T1 image demonstrates right parietal leptomeningeal enhancement and also shows some of the enlarged deep medullary veins along with the enlarged choroid plexus in the right hemisphere.

Associations between EDMV scores and clinical epilepsy variables.

Clinical epilepsy variables showed no significant correlation with the EDMV scores in the whole group or in the left or right subgroups (p>0.05 in all correlations). However, inspection of the scatter plot revealed that all patients with EDMV scores >4 (19/19) had rare seizures (frequency score 0–1, i.e., less than monthly), while 11/31 (35%) of patients with EDMV scores ≤4 had monthly or more frequent seizures (scores 2–3). The difference was significant in both the whole group (p=0.003) and in right SWS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of frequent (monthly or more; scores 2–3) vs. rare (less than monthly; scores 0–1) seizures in patients with low (≤4) vs. high (>4) enlarged deep medullary vein (EDMV) score in the whole group as well as in the right and left SWS groups.

| All patients | Right SWS | Left SWS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| EDMV>4 | EDMV≤4 | EDMV>4 | EDMV≤4 | EDMV>4 | EDMV≤4 | |

|

| ||||||

| Frequent seizures (scores 2–3) | 0 | 11 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 6 |

| Rare seizures (scores 0–1) | 19 | 20 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 10 |

| % with frequent seizures | 0% | 35% | 0% | 33% | 0% | 38% |

|

| ||||||

| Fisher’s exact test | p=0.003 | p=0.047 | p=0.12 | |||

Predictors of IQ in the whole group.

When IQ measures of all patients were analyzed, regardless of LVM extent, the only significant clinical or MRI predictor of lower PIQ was lower age at seizure onset in both left and right SWS (r=0.67, p=0.005 and r=0.46, p=0.049, respectively). Low VIQ was associated with greater extent of LVM involvement in left SWS (r=−0.61, p=0.009) and showed a trend toward lower age at seizure onset (r=0.43, p=0.065), but no clinical or MRI variable predicted VIQ in right SWS. Greater extent of atrophy was associated with lower VIQ (r=−0.40, p=0.013) in the whole group.

Predictors of IQ in patients with extensive LVM.

In patients with extensive LVM (i.e., LVM involving two or more lobes, n=41), neither the extent of LVM nor clinical epilepsy variables were associated with IQ measures. In contrast, higher EDMV scores in the right SWS subgroup with extensive LVM were associated with higher IQ measures (Figure 5). No significant correlations were found between EDMV scores and IQ variables in the left SWS subgroup (with at least two LVM-affected lobes).

Figure 5.

Correlations of enlarged deep medullary vein (EDMV) scores with PIQ (A, B) and VIQ (C, D) in patients with at least two LVM-affected lobes. Higher EDMV scores were associated with higher PIQ (rho=0.56, p=0.02) and VIQ (rho=0.52, p=0.03) in right SWS (n=17). The correlations were not significant in left SWS (PIQ: rho=−0.27, p=0.33; VIQ: rho=−0.31, p=0.25; n=15).

Association between aspirin treatment and MRI and clinical variables.

EDMV scores were not different in those with vs. without aspirin treatment (p=0.73 in right and p=0.77 in left SWS subgroup). Other clinical or MRI variables were also not different between the aspirin vs. no-aspirin treatment subgroups (p>0.1 in all comparisons).

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that EDMVs are common in both right and left hemispheric SWS; however, extensive multilobar presence of these enlarged deep veins was almost four times more common in children with right SWS, including several young children. While EDMVS commonly occurred in LVM-affected lobes, and the extent of these two vascular abnormalities showed a significant correlation, EDMV scores did not correlate with the extent of brain atrophy. Our data also indicate the potential beneficial effects of early, extensive deep medullary venous enlargement on epilepsy severity and, at least in right SWS, on cognitive functions. Altogether, these results support the notion that EDMVs can provide compensatory venous drainage with a beneficial effect on clinical symptoms.

Previous imaging studies in SWS also suggested a high frequency (at least 70–75%) of EDMVs in patients with SWS and epilepsy and less frequent detection of such abnormalities in those with no epilepsy (Juhasz et al., 2007; Kaseka et al., 2016). In the present study, where the vast majority (92%) of the patients had a history of epilepsy, EDMVs were detected in 84%, including in all four with no history of epilepsy. However, patients with extensive EDMVs had relatively rare seizures, while more than a third of the patients with less extensive EDMVs had frequent seizures. This result extends our previous observation reported in a young child with an early expansion of EDMVs who achieved excellent seizure control and reversal of severe right cortical hypometabolism despite extensive right hemispheric SWS involvement (John et al., 2018). Deep vein collaterals can relieve the LVM-affected cortex and subcortical white matter from increased venous pressure by channeling the venous blood centripetally toward the deep venous system. Early development of an effective collateral deep venous flow may diminish the effects of LVM-induced hypoxia in the cortex, thus leading to less glutamate-related brain injury (Juhasz et al., 2016) and less severe epilepsy.

The apparent beneficial cognitive effects of EDMVs were only observed in those with at least two LVM-affected lobes and this effect was only observed in right hemispheric SWS. Small, unilobar LVM is less likely to induce extensive enlargement of deep veins or disruption of distributed cognitive networks; therefore, venous remodeling in these cases may have negligible effects. Consistent with this notion, children with unilobar LVM (including 3 children with no MRI signs of EDMV) had their PIQ and VIQ in the normal range (>85) in all but one child with a frontal lobe LVM. In the whole group, including such mild cases, age at seizure onset and extent of LVM were significant predictors of IQ measures, which was expected from previous studies (Bosnyak et al., 2016; Luat et al., 2018; Day et al., 2019a); however, when patients with small, unilobar LVM were excluded, extensive EDMVs were associated with better cognitive functions, while those with no or limited EDMV had lower IQ measures.

We have previously reported longitudinal SWI data in three young children with right SWS (all of whom were included also in the present study, using their second scan), indicating post-natal evolution and expansion of EDMVs, i.e., active deep venous remodeling during the early disease course. The observed robust right/left differences in the extent of EDMVs and their beneficial effects on IQ in right SWS may be related to early asymmetries in brain development, including asymmetric maturation of the vascular system. Some brain regions undergo an earlier growth and maturation in the right hemisphere prenatally and in the early postnatal period (Simonds & Scheibel, 1989; Sun et al., 2005), and this can create an asymmetric metabolic demand favoring the right side. Consistent with this, hemodynamic and metabolic parameters in newborns showed higher values in the right hemisphere (Lin et al., 2013), and dynamic single photon emission computed tomography studies have demonstrated a right hemispheric predominance of cerebral blood flow between 1 and 3 years of age (Chiron et al., 1997). In SWS, LVM-driven impairment of superficial venous drainage in the more rapidly developing right hemisphere may cause a more robust hypoxic state early, which could stimulate blood vessel development and endothelial proliferation (Plate et al., 1999; Comati et al., 2007). Early elevation of right hemispheric perfusion may also lead to a more robust increase of venous pressure facilitating expansion of existing small medullary veins. In contrast, more protracted course of left hemispheric development may lead to a slower increase of metabolic demand and more gradual enlargement of EDMVs, potentially explaining the lack of extensive EDMVs in young children with left SWS (Figure 3). This likely provides additional time and opportunity for reorganization of various brain functions while making the effects of hemispheric venous remodeling less crucial functionally in left SWS. In addition, right hemispheric functional reorganization in left SWS can lead to a preservation of verbal but impaired non-verbal IQ (due to a right-hemispheric “crowding” effect) (Behen et al., 2011) that may obscure the beneficial effects of venous remodeling in left SWS. These mechanisms remain speculative but could be further explored in longitudinal studies starting at the very early clinical stages of SWS.

It remains unclear if early therapeutic intervention, including aspirin treatment, can play a role in facilitating preservation or early expansion of deep collateral veins and better clinical outcome in SWS. One potential mechanism of a beneficial effect of early aspirin treatment could be the stabilization of enlarged deep veins by preventing their occlusion. Obliteration of deep cerebral veins indeed has been documented by studies in SWS children (Garcia et al., 1981; reviewed by Slasky et al., 2006), but it remains unclear if aspirin or any other treatment could prevent this and lead to a more robust collateral deep venous system during the early disease course. The majority of the patients in the present study did not receive aspirin. While we found no difference in EDMV scores (and any other variables) between those with versus without a history of aspirin treatment, we did not have reliable detailed data as to how early and how long aspirin treatment was employed in these patients. This issue could be further addressed in prospective studies in young children with SWS.

Although this study is the largest to analyze the extent of EDMVs in SWS, it is still limited by its relatively small sample size and its cross-sectional design. Substantially larger SWS imaging data sets can only be collected with multi-center collaborations and advances in image data harmonization. Limitations in our imaging approach included the use of two different scanners and the visual scoring of the MRI abnormalities. Scanner differences did not seem to affect the results: both the LVM (on post-contrast T1-weighted images) and EDMVs (on SWI) are readily visualized on images obtained both 1.5T and 3T scanners (Juhasz et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2008; Pilli et al., 2017b; John et al., 2018). Also, there was no systematic bias on scanner assignment, as the 1.5T scanner was simply replaced by 3T after the 23rd patient. Consistent with this, the MRI and clinical variables did not differ between patients scanned on the two scanners. Therefore, it is unlikely that scanner differences substantially affected the results. Visual scoring of the extent of EDMVs is subjective, but test-retest reliability was high (ICC 0.96). An alternative option would be to count the exact number of enlarged deep medullary veins, but ICCs for intra- and inter-rater agreement were reported to be lower (0.68 and 0.75) for such an approach (Ao et al., 2021). Objective, automated SWI-based deep venous segmentation could be an attractive approach and has been reported in a non-SWS population with no major vascular or parenchymal abnormalities (Bériault et al., 2015). However, such an approach can be substantially more complex in the SWS brain, where the normal brain anatomy and vasculature is often severely altered; in particular, automated differentiation between venous signals and calcification is not a trivial task on SWI. Nevertheless, a multi-modal MRI approach may overcome this challenge in the future. Finally, early, deep venous remodeling in SWS may affect additional SWS-related clinical symptoms, such as headaches and stroke-like episodes. Accurate data on such symptoms were not collected systematically from a large subset of our participants, especially in the early study period, when we focused on seizures and cognitive functions. Since the majority of the participants came from other states, reliable retrospective data collection would not be feasible. Nevertheless, we continue the study, which now includes data collection on both headaches and stroke-like events, and we plan to evaluate the potential impact of deep venous remodeling on these symptoms in the future.

In conclusion, these data demonstrate that EDMVs are often present but are highly variable in the affected hemisphere of patients with unilateral SWS; however, early, extensively enlarged deep veins appear to develop more commonly in right SWS. The data support the concept that extensive deep venous remodeling may contribute to better seizure outcome and, particularly in patients with right SWS involvement, a better cognitive outcome in SWS.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Yang Xuan for performing MRI acquisitions and to the Sturge-Weber Foundation for patient referrals.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers NS041922 and NS065705).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ao DH, Zhang DD, Zhai FF, Zhang JT, Han F, Li ML, Ni J, Yao M, Zhang SY, Cui LY, Jin ZY, Zhou LX, Zhu YC. Brain deep medullary veins on 3-T MRI in a population-based cohort. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41:561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behen ME, Juhász C, Wolfe-Christensen C, Guy W, Halverson S, Rothermel R, Janisse J, Chugani HT. Brain damage and IQ in unilateral Sturge-Weber syndrome: Support for a “fresh start” hypothesis. Epilepsy Behav 2011;22:352–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentson JR, Wilson GH, Newton TH. Cerebral venous drainage pattern of the Sturge-Weber syndrome. Radiology 1971;101:111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bériault S, Xiao Y, Collins DL, Pike GB. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. Automatic SWI venography segmentation using conditional random fields. 2015;34:2478–2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodensteiner JB, Roach ES. Overview of Sturge-Weber syndrome. In: Bodensteiner JB, Roach ES, eds. Sturge-Weber syndrome. Mt Freedom, NJ: The Sturge-Weber Foundation, 2010:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bosnyák E, Behen ME, Guy WC, Asano E, Juhász C. Predictors of cognitive functions in children with Sturge-Weber syndrome: A longitudinal study. Ped Neurol 2016;61:38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiron C, Jambaque I, Nabbout R, Lounes R, Syrota A, Dulac O. The right brain hemisphere is dominant in human infants. Brain. 1997;120 (Pt 6):1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comati A, Beck H, Halliday W, Snipes GJ, Plate KH, Acker T. Upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha and HIF-2alpha in leptomeningeal vascular malformations of Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:86–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day AM, McCulloch CE, Hammill AM, Juhász C, Lo WD, Pinto AL, Miles DK, Fisher BJ, Ball KL, Wilfong AA, Levin AV, Thau AJ, Comi A. Physical and family history variables associated with neurologic and cognitive development in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Pediatr Neurol 2019a;96:30–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day AM, Hammill AM, Juhász C, Pinto AL, Roach ES, McCulloch CE, Comi AM. Hypothesis: Presymptomatic treatment of Sturge-Weber syndrome with aspirin and antiepileptic drugs may delay seizure onset. Ped Neurol 2019b;90:8–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JC, Roach ES, McLean WT. Recurrent thrombotic deterioration in the Sturge-Weber syndrome. Childs Brain. 1981;8:427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke EM, Ayaz M, Khan A, Manova ES, Krishnamurthy B, Gollapalli L, Ciulla C, Lim I, Peterson F, Kirsch W. Establishing a baseline phase behavior in magnetic resonance imaging to determine normal vs. abnormal iron content in the brain. J Magn Reson Imaging 2007;26:256–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke EM, Mittal S, Wu Z, Neelavalli J, Cheng YC. Susceptibility-weighted imaging: technical aspects and clinical applications, part 1. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:19–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Lu Y, Juhász C, Kou Z, Xuan Y, Latif Z, Kudo K, Chugani HT, Haacke EM. MR susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) complements conventional contrast enhanced T1 weighted MRI in characterizing brain abnormalities of Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Magnetic Res Imaging 2008;28:300–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John F, Maqbool M, Jeong JW, Agarwal R, Behen ME, Juhász C. Deep cerebral vein expansion with metabolic and neurocognitive recovery in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5:502–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhász C, Haacke M, Hu J, Xuan Y, Makki M, Behen ME, Maqbool M, Muzik O, Chugani DC, Chugani HT. Multimodality imaging of cortical and white matter abnormalities in Sturge-Weber syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28:900–906. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhász C, Hu J, Xuan Y, Chugani HT. Imaging increased glutamate in children with Sturge-Weber syndrome: Association with epilepsy severity. Epilepsy Res. 2016;122:66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaseka ML, Bitton JY, Décarie JC, Major P. Predictive factors for epilepsy in pediatric patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;64:52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lance EI, Sreenivasan AK, Zabel TA, Kossoff EH, Comi AM. Aspirin use in Sturge-Weber syndrome: side effects and clinical outcomes. J Child Neurol. 2013;28:213–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Pennington MA, Kenney CM 3rd. MR evaluation of developmental venous anomalies: medullary venous anatomy of venous angiomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1996;17:61–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PY, Roche-Labarbe N, Dehaes M, Fenoglio A, Grant PE, Franceschini MA. Regional and hemispheric asymmetries of cerebral hemodynamic and oxygen metabolism in newborns. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:339–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZY, Zhai FF, Ao DH, Han F, Li ML, Zhou L, Ni J, Yao M, Zhang SY, Cui LY, Jin ZY, Zhu YC. Deep medullary veins are associated with widespread brain structural abnormalities. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2022;42:997–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo W, Marchuk DA, Ball K, Juhász C, Jordan LC, Ewen JB, Comi A. Updates and future horizons on the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of Sturge-Weber syndrome brain involvement. Dev Med Child Neurol 2012;54:214–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luat AF, Behen ME, Chugani HT, Juhász C. Cognitive and motor outcomes in children with unilateral Sturge-Weber syndrome: Effect of age of seizure onset and side of brain involvement. Epilepsy & Behavior 2018;80:202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsa CF. Sturge-Weber syndrome: a unified pathophysiologic mechanism. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2008;10:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilli V, Behen ME, Hu J, Xuan Y, Janisse J, Chugani HT, Juhász C. Clinical and metabolic correlates of cerebral calcifications in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol 2017a;59:952–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilli VK, Chugani HT, Juhász C. Enlargement of deep medullary veins during the early clinical course of Sturge-Weber syndrome. Neurology 2017b;88:103–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plate KH. Mechanisms of angiogenesis in the brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1999;58:313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Kobayashi N. Cerebral venous angiomas: clinical evaluation and possible etiology. Radiology 1981;139:87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med 2013;23:1971–1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonds RJ, Scheibel AB. The postnatal development of the motor speech area: a preliminary study. Brain Lang. 1989; 37:42–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slasky SE, Shinnar S, Bello JA. Sturge-Weber syndrome: deep venous occlusion and the radiologic spectrum. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;35:343–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Patoine C, Abu-Khalil A, Visvader J, Sum E, Cherry TJ, Orkin SH, Geschwind DH, Walsh CA. Early asymmetry of gene transcription in embryonic human left and right cerebral cortex. Science 2005; 308:1794–1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taoka T, Fukusumi A, Miyasaka T, Kawai H, Nakane T, Kichikawa K, Naganawa S. Structure of the medullary veins of the cerebral hemisphere and related disorders. Radiographics. 2017;37:281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Pan J, Zhao M, Wang X, Zhang C, Li T, Wang M, Wang J, Zhou J, Liu C, Sun Y, Zhu M, Qi X, Luan G, Guan Y. Characteristics, surgical outcomes, and influential factors of epilepsy in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Brain. 2021. Dec 21:awab470. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]