Abstract

We have studied the impact of deficiency of the complement system on the progression and control of the erythrocyte stages of the malarial parasite Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi. C1q-deficient mice and factor B- and C2-deficient mice, deficient in the classical complement pathway and in both the alternative and classical complement activation pathways, respectively, exhibited only a slight delay in the resolution of the acute phase of parasitemia. Complement-deficient mice showed a transiently elevated level of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) in the plasma at the time of the acute parasitemia compared with that of wild-type mice. Although there was a trend for increased precursor frequencies in CD4+ T cells from C1q-deficient mice producing IFN-γ in response to malarial antigens in vitro, intracellular cytokine staining of spleen cells ex vivo showed no difference in the numbers of IFN-γ+ splenic CD4+ and CD8+ cells. In contrast, C1q-deficient animals were significantly more susceptible to a second challenge with the same parasite. C1q-deficient animals showed a reduced level of anti-malarial immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) antibody 100 days after primary infection. However, following a significantly higher parasitemia, C1q-deficient mice had increased levels of IgM and IgG2a anti-malarial antibodies. In summary, this study indicates that while complement plays only a minor role in the control of the acute phase of parasitemia of a primary infection, it does contribute to parasite control in reinfection.

The cellular immune response to Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi malaria in mice has been extensively studied in vivo. The early period of infection is associated with a strong TH1-like CD4+-T-cell response characterized by the production of high levels of gamma interferon (IFN-γ). The demonstration of exacerbated P. c. chabaudi infections in mice treated with anti-IFN-γ (24, 35) or mice lacking IFN-γ (41) or an effective IFN-γ receptor (9, 40) supports the view that IFN-γ-mediated pathways play a role in the control of acute parasitemia. Later in the infection, after the initial reduction in parasitemia, there is a switch to a TH2-like response associated with production of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-10 and the provision of help to B cells for antibody responses (19). At this stage, B cells are necessary for the control and clearance of residual parasites (25, 42, 44), suggesting a requirement for antibody in the resolution of infection. More recently, B cells have also been implicated in the regulation of the switch of T cells from the initial TH1-like response to a TH2-like response (17). The mechanism by which antibody mediates its protective effect is not known. Neutralization or agglutination of parasites, inhibition of merozoite invasion (2, 8), Fc receptor phagocytosis or cytoxicity (4), and complement-dependent lysis or uptake are all possible effector mechanisms.

Studies of human malaria suggest that the complement system, particularly the classical pathway, may play a role in host defense against malarial infection (13, 30, 33, 47). The first component of the lectin pathway, mannose binding lectin (MBL), is an acute-phase reactant which increases in serum during malarial attacks (39). However, deficiency of MBL is relatively common (36), and it does not seem to be associated with increased susceptibility to severe malaria and/or cerebral malaria (1).

Several attempts have been made to address the potential role of complement in host defense against malaria infection in vitro with varied results. Complement has been shown to be able to kill both human and rodent malaria parasites in vitro, at different stages in the life cycle, in the presence of specific antibodies (10, 11, 29). However, infected erythrocytes, in spite of their ability to activate complement, seem quite resistant to complement-mediated lysis, a phenomenon attributable in part to the presence of complement-regulatory proteins on the infected cells (14, 48). Moreover, Plasmodium berghei sporozoites have been shown to be resistant to complement from their susceptible rodent hosts but not to human serum (15). Complement has also been assigned a role in the enhancement of Plasmodium falciparum parasite killing by the monocytic cell line THP-1 and human neutrophils (16, 32).

Ward and colleagues studied the role of complement in host defense against P. berghei in vivo in rats by depletion of complement with cobra venom factor (46). They found that complement-depleted rats suffered from more rapid and higher parasitemias and that 60% of the depleted animals succumbed to what in normal rats would had been a nonlethal infection.

As well as the activities of complement in target cell lysis and opsonophagocytosis, complement has a well-established role in the regulation of antibody responses (5), suggesting that the effect of complement deficiency during infection may be more widespread than just the loss of complement-mediated parasite killing.

In the work described here we have investigated the role of complement in host defense against the malaria parasite P. c. chabaudi (AS strain) using mice rendered deficient in complement components by gene targeting. Our data show that the classical pathway of complement plays a minor role in the control of the acute phase of parasitemia. Despite elevated serum IFN-γ levels, C1q-deficient mice suffered a higher peak parasitemia. Of particular note, complement-deficient mice were more susceptible to secondary challenge with the same parasite, indicating impairment in the development of their immunity to reinfection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

C1q-deficient (C1qa−/−) and factor B- and C2-deficient (H2-Bf/C2−/−) mice, lacking the classical complement pathway and both the alternative and classical complement activation pathways, respectively, were generated as previously described (3, 38). All experimental animals were female, of the pure inbred 129/Sv genetic background and between 8 and 10 weeks of age at the start of experiments. Animal care and procedures were conducted according to institutional guidelines.

Parasites and infection.

P. c. chabaudi AS parasites were maintained as described previously (27, 37). C1qa−/− and wild-type mice were infected by intraperitoneal injection of 105 parasitized 129/Sv female-derived erythrocytes. The course of infection was monitored by examination of Giemsa-stained blood film every 1 to 4 days throughout the experimental period. As indicated, some animals were cured of residual parasitemia 8 weeks after primary infection with three intraperitoneal injections of chloroquine (Sigma) (25 mg/kg of body weight; 48 h between injections). The absence of parasites was confirmed on blood smears before secondary infection of the animals with the same dose of P. c. chabaudi parasites 6 weeks later. Naive C1qa−/− and wild-type mice were also infected at the same time and served as controls for the infection.

Infected blood from 129/Sv or C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice was used as a source of antigen in limiting-dilution assays (described below). For this purpose, blood was collected when the parasites were at the late trophozoite stage, passed over a column of CF11 powder to remove leukocytes as described previously (19), washed three times in Hanks balanced salt solution (Gibco, Paisley, United Kingdom) containing 10% fetal calf serum, and resuspended at a 0.1% (vol/vol) suspension in culture medium (described below).

Measurement of cytokines. (i) ELISA for cytokines.

IFN-γ and IL-4, in serum and/or tissue culture supernatants, were measured by ELISA as described previously (19, 43, 44). For analysis of serum IFN-γ levels, at least four mice were studied in each group, with 5 to 12 mice in each group during the peak of infection (7 to 9 days after primary infection).

(ii) Intracellular cytokine staining.

Intracellular staining was used to determine cytokine production by single cells as described previously (28). Cells were suspended at 106/ml and stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (500 ng/ml). Two hours after stimulation, brefeldin A was added at 10 μg/ml, and the cells were incubated for a further 2 h. Cells were harvested, washed, and stained for different surface markers using directly conjugated antibodies. At the end of the procedure, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in PBS with 4% formaldehyde fixative. After incubation for 20 min at room temperature, the cells were stained for cytokines. For the intracellular staining, all reagents were diluted in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.5% saponin; all incubations were carried out at room temperature. The cells were incubated with anti-IL-4 and anti-IFN-γ (Becton Dickinson, Oxford, United Kingdom) or the respective isotype controls. Samples were analyzed on a FACScalibur using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Malaria-specific antibody responses.

Plasma samples were collected from at least five C1qa−/− and wild-type mice before infection, at intervals during the primary infection, and just prior to and 18 days after secondary challenge. The levels of malaria-specific antibodies were measured by ELISA as described previously (18). Briefly, a lysate of P. c. chabaudi parasites was used as a source of antigen. In addition to the test plasma, hyperimmune plasma from mice that had survived more than five challenges of P. c. chabaudi infection was used as a positive control and standard and was given an arbitrary value of 1,000 U/ml for each of the isotypes. Goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin M (IgM), IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b and IgG3 antibodies conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Seralab, Leicestershire, United Kingdom) were used to detect specifically bound mouse Ig of the respective isotypes.

The relative amounts of malaria-specific antibody of the different isotypes are expressed as values of arbitrary ELISA units (AEU) as calculated from the standard hyperimmune serum. Expression of antibody amounts in arbitrary units allows a direct comparison of the amounts of a single isotype produced by C1qa−/− and wild-type mice but does not allow a comparison of the amounts of different isotypes.

Limiting-dilution assay.

Splenic CD4+ T cells were positively selected using a magnetic cell sorting separation system described elsewhere (44). The cells were labeled with biotinylated anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody followed by streptavidin-labeled MACS microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bisley, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Positive cells were labeled with streptavidin peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP) (Becton Dickinson) in order to evaluate cell purity on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). In general, purity was greater than 90%.

Limiting-dilution assays to measure the precursor frequencies of CD4+ T cells responding to antigens of P. c. chabaudi have been described previously (20, 21, 44). The assays allow the simultaneous measurement of T-cell proliferation, help for antibody production, and cytokine production. In the experiments described here, serial twofold dilutions (from 60,000 per culture) of CD4+ T cells were cocultured with immune T-cell-depleted spleen cells (3 × 104 per culture), as a source of antigen-presenting cells and producers of malaria-specific antibody in 200 μl of Iscove's medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, 1 mM l-glutamine, 12 mM HEPES, 5 × 10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.5 mM sodium pyruvate. A 0.1% suspension of P. c. chabaudi-infected erythrocytes was used as a source of antigen. Control cultures were established using uninfected red blood cells as an antigen. Malaria-specific Ig and cytokines were measured by ELISAs as described previously (19, 43, 44). Antibody levels were determined in the culture supernatants after 7 days of culture, and cytokines and proliferative responses were measured after the cultures had been incubated for a further 2 days with irradiated normal C57BL/6 mouse spleen cells and antigen. Precursor frequencies were determined from the zero-order term of the Poisson distribution using regression analysis. Cultures were considered positive when either proliferation or antibody or cytokine production exceeded the background response (without T cells) by more than 3 standard deviations.

Statistics.

Statistics were calculated using GraphPad Prism version 2.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.). Nonparametric tests were applied throughout unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

Resolution of the acute phase of P. c. chabaudi infection in complement-deficient mice.

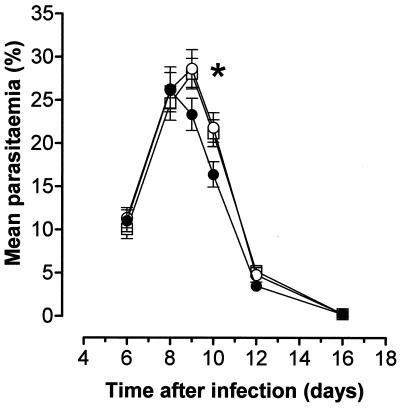

The initial few days of parasitemia were no different in C1qa−/− and wild-type mice. Parasitemia peaked in the wild-type mice at 26.0% ± 2.1% (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) 8 days after infection (Fig. 1). However, parasitemia continued to rise in the C1qa−/− animals for another day before peaking at 28.7% ± 2.2% on day 9. The control of the acute phase of infection was mildly, but significantly, impaired in the C1qa−/− mice (parasitemia of 21.9% ± 1.7% in 7 C1qa−/− animals compared to 16.4% ± 1.5% in 11 control mice 10 days after infection; P < 0.05 [Mann-Whitney test]). After the initial slight delay in clearance, the parasites were cleared normally. H2-Bf/C2−/− mice (n = 14) exhibited parasitemia levels similar to those seen in C1qa−/− animals (peak parasitemia on day 9, 28.1% ± 1.8%) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Acute-phase parasitemia in complement-deficient and wild-type mice. Although parasitemias were essentially similar during the initial days of infection in C1qa−/− (open circles) and wild-type (solid circles) mice, the peak of infection was slightly delayed in the C1qa−/− animals, resulting in a delay in crisis (P < 0.05 [∗] at day 10). H2-Bf/C2−/− mice (open squares) had parasitemias similar to those in C1qa−/− animals. The error bars indicate the SEM.

Increased susceptibility of C1qa−/− mice to secondary infection with P. c. chabaudi.

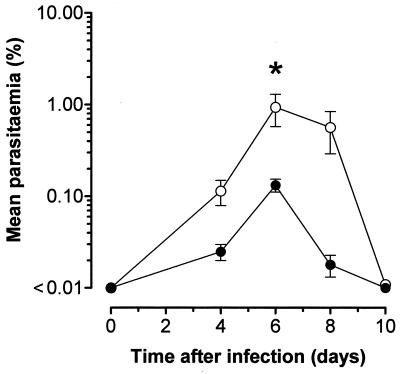

Previously infected C1qa−/− and wild-type mice were challenged a second time with P. c. chabaudi 14 weeks after primary infection as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 2). Six days after secondary infection, all the wild-type and C1qa−/− animals had detectable parasitemias (>0.01%). The mean percentage of blood cells that were parasitized was significantly greater at this point in 9 C1qa−/− mice (0.94% ± 0.36% compared to 0.13% ± 0.02% in 11 control animals) (P < 0.05[Student's t test on log-transformed data]). Parasitemia levels as high as 3.14% were observed among the C1qa−/− mice, but they did not exceed 0.26% in the wild-type controls.

FIG. 2.

C1qa−/− mice suffer from a more severe secondary infection. Six days after secondary infection, all of the wild-type (solid circles; n = 11) and C1qa−/− (open circles; n = 9) animals had detectable parasitemias (>0.01%). The percentage of blood cells that were parasitized was significantly greater at this point in the C1qa−/− mice (P < 0.05 [∗]; Student's t test on log-transformed data). The error bars indicate the SEM.

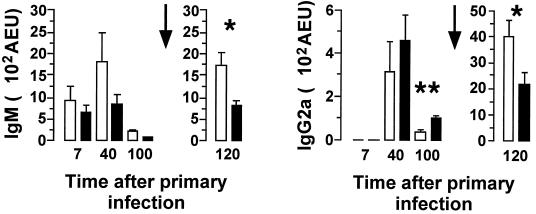

Anti-malaria specific antibody responses in C1q-deficient mice.

During the primary infection, anti-malaria specific antibody responses (days 7 and 40) were no different in C1qa−/− and wild-type mice. One hundred days after the primary infection (immediately prior to reinfection), the C1qa−/− mice had lower levels of IgG2a anti-malarial antibodies (median, 33 AEU; range, 12 to 74 AEU; n = 5) than the wild-type mice (median, 82 AEU; range, 78 to 170 AEU; n = 5; p < 0.01 [Mann-Whitney test]) (Fig. 3). The mice were reinfected on day 102, and antibody levels were again measured on day 120. After the second challenge, the C1qa−/− animals (n = 9) had significantly greater levels than the wild-type mice (n = 11) of IgM (median, 1,457 AEU [range, 790 to 3,380 AEU] and 1,014 AEU [range, 260 to 1,390 AEU], respectively; P < 0.05 [Mann-Whitney test]) and of IgG2a (median, 3,910 AEU [range, 936 to 6,290 AEU] and 1,430 AEU [range, 229 to 4,880 AEU], respectively; P < 0.05 [Mann-Whitney test]) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Anti-malaria specific antibodies in C1qa−/− and wild-type mice. Throughout the primary infection, antibody responses in C1qa−/− mice (open bars) were not significantly different from those in the wild-type controls (solid bars). Prior to secondary infection (day 100), the C1qa−/− mice (n = 5) exhibited a lower level of IgG2a anti-malarial antibodies than the wild-type mice (n = 5) (P < 0.01 [∗∗]; Mann-Whitney test). The mice were reinfected on day 102 (indicated by arrows), and antibody levels were measured on day 120 (the antibody titers for day 120 correspond to the second y axis because of significant increases in serum titers at this time). After the second challenge, the C1qa−/− animals (n = 9) had significantly greater levels of IgM (P < 0.05 [∗]; Mann-Whitney test) and IgG2a (P < 0.05; Mann-Whitney test) than the wild-type mice (n = 11). Anti-malarial IgG1, IgG2b, and IgG3 titers were similar in C1qa−/− and wild-type mice throughout the infection (data not shown). The data shown correspond to means + SEM (n = 5 to 11 at each time point).

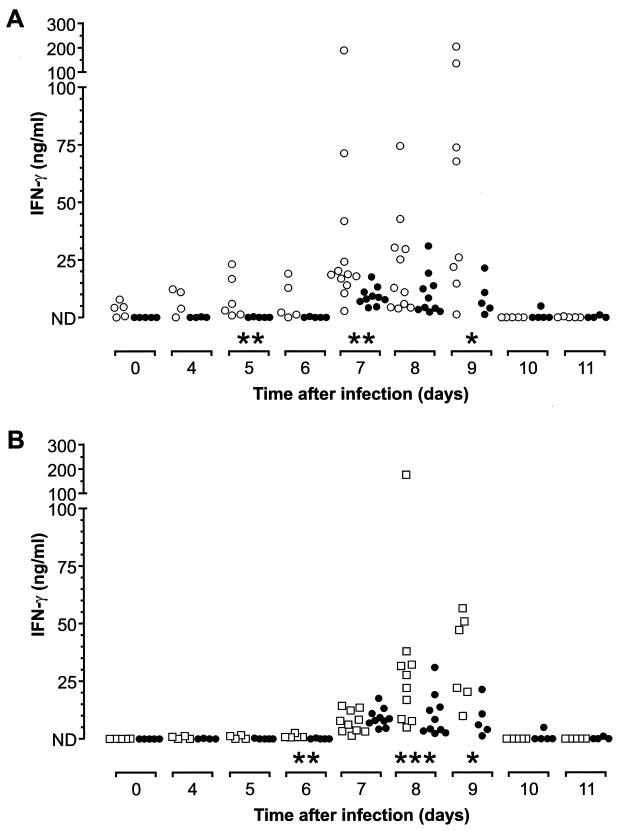

Augmented serum IFN-γ response in C1qa−/− mice during the acute phase of infection.

We have shown previously that C1qa−/− mice immunized with a conventional antigen have lower levels of IFN-γ produced by antigen-specific CD4+ T cells (6). Since IFN-γ has been shown to be important in the control of the acute phase of malarial infection (9, 24, 35, 40, 41), the circulating levels of IFN-γ in C1qa−/− and wild-type mice during a P. c. chabaudi infection were compared. IFN-γ was detectable in the sera of wild-type mice only during the peak of infection (days 7 to 9), as previously reported (Fig. 4). However, circulating IFN-γ was detectable in the C1qa−/− animals at significantly elevated levels throughout the acute phase (Fig. 4A). By day 5, the median concentration of IFN-γ in the sera of C1qa−/− mice (n = 6) was 4.46 ng/ml (range, 0.86 to 23.12 ng/ml) compared to <0.04 ng/ml (range, <0.04 to 0.34 ng/ml) in five wild-type mice (P < 0.01 [Mann-Whitney test]). Seven days after infection, the median concentration in 10 C1qa−/− mice was 18.66 ng/ml (range, 2.83 to 188 ng/ml) compared to 7.34 (range, 4.20 to 17.62 ng/ml) in 12 wild-type mice (P < 0.01 [Mann-Whitney test]). Serum IFN-γ was still significantly higher in the C1qa−/− mice (n = 8) 9 days after infection (median, 46.91 ng/ml; range, 1.32 to 74.50 ng/ml) than in the six wild-type mice (median, 6.14 ng/ml; range, 1.32 to 21.46 ng/ml) (P < 0.05 [Mann-Whitney test]). After day 9, IFN-γ was no longer detectable in the serum, consistent with previous reports. H2-Bf/C2−/− mice also exhibited increased circulating levels of IFN-γ during the acute phase of parasitemia, with significantly greater amounts of protein detectable on days 6, 8, and 9 (Fig. 4B). Six days after infection, five H2-Bf/C2−/− mice had a median concentration of IFN-γ in circulation of 0.81 ng/ml (range, 0.65 to 2.55 ng/ml) compared to 0 ng/ml (range, 0 to 0.38 ng/ml) in five control mice (P = 0.0079 [Mann-Whitney test]). By days 8 and 9, the median circulating IFN-γ concentrations in the H2-Bf/C2−/− animals were 24.96 ng/ml (range, 4.97 to 174 ng/ml; n = 10) and 34.75 ng/ml (range, 9.89 to 56.72 ng/ml; n = 6), respectively, compared to 6.39 ng/ml (range, 2.36 to 31.01 ng/ml; n = 10) and 6.14 ng/ml (range, 1.32 to 21.46 ng/ml; n = 5) in the wild-type 129/Sv mice.

FIG. 4.

(A) Scatter plot showing the circulating quantities of IFN-γ during the acute phase of infection. In the infected wild-type mice (solid circles), IFN-γ was detected only at the peak of parasitemia (days 7 to 9); however, in the C1qa−/− mice (open circles), IFN-γ was detectable much earlier in the infection and the levels were significantly higher on days 5, 7, and 9 (P < 0.01, [∗∗], P < 0.01, and P < 0.05 [∗], respectively; Mann-Whitney tests). ND, undetectable levels of IFN-γ in the serum. (B) H2-Bf/C2−/− animals (open squares) exhibited kinetics in the production of IFN-γ similar to those of wild-type mice (solid circles), but the levels of protein in the serum were significantly greater in the H2-Bf/C2−/− mice on days 6, 8, and 9 (P < 0.01, P < 0.001 [∗∗∗], and P < 0.05, respectively; Mann-Whitney tests).

Cytokine production by T cells during a P. c. chabaudi infection in C1qa−/− mice.

Limiting-dilution assays of CD4+ T cells were performed 7 and 28 days after primary infection of C1qa−/− mice to measure the precursor frequencies of IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells responding to malarial antigens. While there was a trend toward an increase in the frequency of IFN-γ-producing antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in the C1qa−/− mice, the numerical difference in precursor frequencies was small (Table 1). There was no significant difference in the frequency of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells producing IL-4 or providing help for antibody production at these times.

TABLE 1.

Precursor frequencies of IFN-γ-and IL-4-producing cells responding to malarial antigens

| Day of infection | Genotype of mouse | CD4+-T-cell precursor frequencya (per 106 cells)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | IL-4 | Help for Ab production | ||

| 7 | C1qa−/− | 758.2 ± 111.4 | 154.0 ± 77.0 | 102.6 ± 4.05 |

| C1qa+/+ | 545.5 ± 46.0 | 128.7 ± 68.1 | 151.5 ± 12.5 | |

| 28 | C1qa−/− | 326.7 ± 22.7 | 87.7 ± 23.3 | 511.6 ± 123.4 |

| C1qa+/+ | 147.0 ± 16.7 | 150.3 ± 26.3 | 412.7 ± 15.35 | |

The data shown represent the mean ± SEM of two separate assays conducted on cells pooled from three mice in each group at each time point. Ab, antibody.

Assessment by intracellular cytokine staining of the numbers of splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ and IL-4 showed no differences between C1qa−/− and wild-type mice at any time point measured during the infection (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This study of P. c. chabaudi infection in complement-deficient mice demonstrated that only a minor role was played by either the alternative or classical pathway of complement activation in the early stages of malaria infection. The relatively small contribution of complement to this early stage of infection by the blood stage parasite is perhaps a consequence of the inefficiency of complement in mediating the lysis of parasite-infected cells (14, 48). These data, taken together with studies demonstrating that antibody-mediated protection in nonlethal or lethal malaria models does not require Fc receptors (31, 45), suggest that there is not a prominent role for either of the major opsonophagocytic systems in host defense against a primary blood stage malaria infection in mice.

Complement, however, did play a role in immunity to a second challenge, since after reinfection with the same dose of parasites used in the initial infection, the mean peak parasitemia in C1qa−/− mice was sevenfold greater than that in the control mice. The role of complement as an adjuvant to low doses of antigen is well established (7), and complement is known to play a significant role in the acquired immune response to T-cell-dependent antigens, which results in high titers of class-switched antibody and the development of immunological memory (5). In order to determine whether any defect in antibody response in C1qa−/− mice during a P. c. chabaudi infection could have contributed to their subsequent susceptibility to reinfection, the isotype and subclass levels of the malaria-specific antibodies in the sera of the infected animals were measured throughout the primary and secondary infections. In general, there was very little difference between the antibody responses of the C1qa−/− and wild-type mice during primary infection. However, after 3 months of the primary infection, there were significantly smaller amounts of malaria-specific IgG2a antibody remaining in the C1qa−/− mice. After a second challenge infection, the levels of IgG2a and IgM anti-malaria antibodies were both significantly increased in the C1qa−/− animals compared with control mice. We have previously reported that C1qa−/− mice produce significantly less antigen-specific IgG2a and IgG3 in response to low doses of T-cell-dependent antigens (6). The inability to sustain an IgG2a response when the parasite load is low may reflect a similar mechanism. The increase in antibody titer after secondary infection to levels comparable with or higher than in wild-type mice might be related to the larger parasite dose endured by the C1qa−/− animals at this time.

The experiments described here appear to contradict our previous study where, using low doses of T-cell-dependent antigens, C1q-deficient antigen-specific CD4+ T cells produced lower IFN-γ levels than the control cells (6). During P. c. chabaudi infections, IFN-γ production was not reduced in C1qa−/− mice compared with that in wild-type mice. By contrast, the numbers of IFN-γ-positive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells detected by intracellular cytokine labeling and the precursor frequencies of malaria-specific cells producing IFN-γ were comparable, and the amount of IFN-γ transiently present in the plasma early in infection was significantly higher in the complement-deficient mice. Despite the greater amounts of IFN-γ in the plasma, and the role of IFN-γ as a switch factor for IgG2a (34), there was no concomitant rise in IgG2a titers in C1qa−/− mice. The location and cellular source of the IFN-γ observed in the plasma are not known, and this is likely to be important for B-cell switching. Markine-Goriaynoff et al. showed that antigen-specific IgG2a responses during parasitic and viral infections could be relatively normal in the absence of IFN-γ (23), suggesting that alternative mechanisms for the regulation of IgG2a exist in vivo. The relationship between complement and IFN-γ or regulation of IgG2a antibodies is not understood, and therefore the reasons for these discrepancies are not known. Since plasma IFN-γ was increased in C1qa−/− mice without any obvious increase in the number of T cells producing this cytokine, it may be that NK cells and not T cells are the source of larger amounts. P. c. chabaudi schizonts are able to activate dendritic cells to produce IL-12, which is a differentiation factor for both NK cells and Th1 cells (12, 22), the major sources of early IFN-γ in this infection (21, 26). Dependency on complement components, for example, for increased uptake of antigen and activation of dendritic cells to initiate the IL-12–IFN-γ pathway may be circumvented by the large number of replicating parasites. The increased IFN-γ levels in the plasma of the complement-deficient mice may simply reflect the increased number of parasites in these mice.

In summary, complement-deficient mice exhibited a slightly increased acute-phase parasitemia after infection with P. c. chabaudi, which was accompanied by significantly greater IFN-γ production. C1qa−/− mice suffered from a more pronounced secondary infection after rechallenge with the same parasite. The inability of C1qa−/− animals to mount a full response to rechallenge may reflect a basic defect in signaling through complement receptors on B cells or in antigen trapping on follicular dendritic cells, which have been implicated in the maintenance of antibody levels and in B-cell memory.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Arthritis Research Campaign (grant number W0554), the MRC (J.L. and E.S.), and the Wellcome Trust (grant number 0420750 [J.L.]).

We thank the staff of our animal facilities for the care of the mice used in these studies and Pearline Benjamin for her assistance with the ELISAs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bellamy R, Ruwende C, McAdam K P, Thursz M, Sumiya M, Summerfield J, Gilbert S C, Corrah T, Kwiatkowski D, Whittle H C, Hill A V. Mannose binding protein deficiency is not associated with malaria, hepatitis B carriage nor tuberculosis in Africans. Q J Med. 1998;91:13–18. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/91.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackman M J, Heidrich H G, Donachie S, McBride J S, Holder A A. A single fragment of a malaria merozoite surface protein remains on the parasite during red cell invasion and is the target of invasion-inhibiting antibodies. J Exp Med. 1990;172:379–382. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botto M, Dell'Agnola C, Bygrave A E, Thompson E M, Cook H T, Petry F, Loos M, Pandolfi P P, Walport M J. Homozygous C1q deficiency causes glomerulonephritis associated with multiple apoptotic bodies. Nat Genet. 1998;19:56–59. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouharoun-Tayoun H, Oeuvray C, Lunel F, Druilhe P. Mechanisms underlying the monocyte-mediated antibody-dependent killing of Plasmodium falciparum asexual blood stages. J Exp Med. 1995;182:409–418. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll M C. The role of complement in B cell activation and tolerance. Adv Immunol. 2000;74:61–88. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60908-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cutler A J, Botto M, van Essen D, Rivi R, Davies K A, Gray D, Walport M J. T cell-dependent immune response in C1q-deficient mice: defective interferon gamma production by antigen-specific T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1789–1797. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.11.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dempsey P W, Allison M E, Akkaraju S, Goodnow C C, Fearon D T. C3d of complement as a molecular adjuvant: bridging innate and acquired immunity. Science. 1996;271:348–350. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egan A F, Burghaus P, Druilhe P, Holder A A, Riley E M. Human antibodies to the 19kDa C-terminal fragment of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 inhibit parasite growth in vitro. Parasite Immunol. 1999;21:133–139. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1999.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Favre N, Ryffel B, Bordmann G, Rudin W. The course of Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi infections in interferon-gamma receptor deficient mice. Parasite Immunol. 1997;19:375–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1997.d01-227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabriel J, Berzins K. Specific lysis of Plasmodium yoelii infected mouse erythrocytes with antibody and complement. Clin Exp Immunol. 1983;52:129–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Healer J, McGuinness D, Hopcroft P, Haley S, Carter R, Riley E. Complement-mediated lysis of Plasmodium falciparum gametes by malaria-immune human sera is associated with antibodies to the gamete surface antigen Pfs230. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3017–3023. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3017-3023.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heufler C, Koch F, Stanzl U, Topar G, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Enk A, Steinman R M, Romani N, Schuler G. Interleukin-12 is produced by dendritic cells and mediates T helper 1 development as well as interferon-gamma production by T helper 1 cells. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:659–668. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jhaveri K N, Ghosh K, Mohanty D, Parmar B D, Surati R R, Camoens H M, Joshi S H, Iyer Y S, Desai A, Badakere S S. Autoantibodies, immunoglobulins, complement and circulating immune complexes in acute malaria. Natl Med J India. 1997;10:5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawamoto Y, Kojima K, Hitsumoto Y, Okada H, Holers V M, Miyama A. The serum resistance of malaria-infected erythrocytes. Immunology. 1997;91:7–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawamoto Y, Winger L A, Hong K, Matsuoka H, Chinzei Y, Kawamoto F, Kamimura K, Arakawa R, Sinden R E, Miyama A. Plasmodium berghei: sporozoites are sensitive to human serum but not susceptible host serum. Exp Parasitol. 1992;75:361–368. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90249-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumaratilake L M, Ferrante A, Jaeger T, Morris-Jones S D. The role of complement, antibody, and tumor necrosis factor alpha in the killing of Plasmodium falciparum by the monocytic cell line THP-1. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5342–5345. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5342-5345.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langhorne J, Cross C, Seixas E, Li C, von der Weid T. A role for B cells in the development of T cell helper function in a malaria infection in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1730–1734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langhorne J, Evans C B, Asofsky R, Taylor D W. Immunoglobulin isotype distribution of malaria-specific antibodies produced during infection with Plasmodium chabaudi adami and Plasmodium yoelii. Cell Immunol. 1984;87:452–461. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langhorne J, Gillard S, Simon B, Slade S, Eichmann K. Frequencies of CD4+ T cells reactive with Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi: distinct response kinetics for cells with Th1 and Th2 characteristics during infection. Int Immunol. 1989;1:416–424. doi: 10.1093/intimm/1.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langhorne J, Meding S J, Eichmann K, Gillard S S. The response of CD4+ T cells to Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi. Immunol Rev. 1989;112:71–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1989.tb00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langhorne J, Simon B. Limiting dilution analysis of the T cell response to Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi in mice. Parasite Immunol. 1989;11:545–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1989.tb00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macatonia S E, Hosken N A, Litton M, Vieira P, Hsieh C S, Culpepper J A, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Murphy K M, O'Garra A. Dendritic cells produce IL-12 and direct the development of Th1 cells from naive CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1995;154:5071–5079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markine-Goriaynoff D, van der Logt J T, Truyens C, Nguyen T D, Heessen F W, Bigaignon G, Carlier Y, Coutelier J P. IFN-gamma-independent IgG2a production in mice infected with viruses and parasites. Int Immunol. 2000;12:223–230. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meding S J, Cheng S C, Simon-Haarhaus B, Langhorne J. Role of gamma interferon during infection with Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3671–3678. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3671-3678.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meding S J, Langhorne J. CD4+ T cells and B cells are necessary for the transfer of protective immunity to Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:1433–1438. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohan K, Moulin P, Stevenson M M. Natural killer cell cytokine production, not cytotoxicity, contributes to resistance against blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS infection. J Immunol. 1997;159:4990–4998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mons B, Collins W E, Skinner J C, van der Star W, Croon J J, van der Kaay H J. Plasmodium vivax: in vitro growth and reinvasion in red blood cells of Aotus nancymai. Exp Parasitol. 1988;66:183–188. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(88)90089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Openshaw P, Murphy E E, Hosken N A, Maino V, Davis K, Murphy K, O'Garra A. Heterogeneity of intracellular cytokine synthesis at the single-cell level in polarized T helper 1 and T helper 2 populations. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1357–1367. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pang X L, Horii T. Complement-mediated killing of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic schizont with antibodies to the recombinant serine repeat antigen (SERA) Vaccine. 1998;16:1299–1305. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phanuphak P, Hanvanich M, Sakulramrung R, Moollaor P, Sitprija V, Phanthumkosol D. Complement changes in falciparum malaria infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1985;59:571–576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rotman H L, Daly T M, Clynes R, Long C A. Fc receptors are not required for antibody-mediated protection against lethal malaria challenge in a mouse model. J Immunol. 1998;161:1908–1912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salmon D, Vilde J L, Andrieu B, Simonovic R, Lebras J. Role of immune serum and complement in stimulation of the metabolic burst of human neutrophils by Plasmodium falciparum. Infect Immun. 1986;51:801–806. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.3.801-806.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siddique M E, Ahmed S. Serum complement C4 levels during acute malarial infection and post-treatment period. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1995;38:335–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snapper C M, Paul W E. Interferon-gamma and B cell stimulatory factor-1 reciprocally regulate Ig isotype production. Science. 1987;236:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.3107127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stevenson M M, Tam M F, Belosevic M, van der Meide P H, Podoba J E. Role of endogenous gamma interferon in host response to infection with blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3225–3232. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3225-3232.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Super M, Thiel S, Lu J, Levinsky R J, Turner M W. Association of low levels of mannan-binding protein with a common defect of opsonisation. Lancet. 1989;2:1236–1239. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91849-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suss G, Eichmann K, Kury E, Linke A, Langhorne J. Roles of CD4- and CD8-bearing T lymphocytes in the immune response to the erythrocytic stages of Plasmodium chabaudi. Infect Immun. 1988;56:3081–3088. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.12.3081-3088.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor P R, Nash J T, Theodoridis E, Bygrave A E, Walport M J, Botto M. A targeted disruption of the murine complement factor B gene resulting in loss of expression of three genes in close proximity, factor B, C2, and D17H6S45. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1699–1704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thiel S, Holmskov U, Hviid L, Laursen S B, Jensenius J C. The concentration of the C-type lectin, mannan-binding protein, in human plasma increases during an acute phase response. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90:31–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb05827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsuji M, Miyahira Y, Nussenzweig R S, Aguet M, Reichel M, Zavala F. Development of antimalaria immunity in mice lacking IFN-gamma receptor. J Immunol. 1995;154:5338–5344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Heyde H C, Pepper B, Batchelder J, Cigel F, Weidanz W P. The time course of selected malarial infections in cytokine-deficient mice. Exp Parasitol. 1997;85:206–213. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.4132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von der Weid T, Honarvar N, Langhorne J. Gene-targeted mice lacking B cells are unable to eliminate a blood stage malaria infection. J Immunol. 1996;156:2510–2516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von der Weid T, Kopf M, Kohler G, Langhorne J. The immune response to Plasmodium chabaudi malaria in interleukin-4-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2285–2293. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von der Weid T, Langhorne J. Altered response of CD4+ T cell subsets to Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi in B cell-deficient mice. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1343–1348. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.10.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vukovic P, Hogarth P M, Barnes N, Kaslow D C, Good M F. Immunoglobulin G3 antibodies specific for the 19-kilodalton carboxyl-terminal fragment of Plasmodium yoelii merozoite surface protein 1 transfer protection to mice deficient in Fc-γ RI receptors. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3019–3022. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.3019-3022.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward P A, Sterzel R B, Lucia H L, Campbell G H, Jack R M. Complement does not facilitate plasmodial infections. J Immunol. 1981;126:1826–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wenisch C, Spitzauer S, Florris-Linau K, Rumpold H, Vannaphan S, Parschalk B, Graninger W, Looareesuwan S. Complement activation in severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;85:166–171. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiesner J, Jomaa H, Wilhelm M, Tony H P, Kremsner P G, Horrocks P, Lanzer M. Host cell factor CD59 restricts complement lysis of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2708–2713. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]