Abstract

Objective:

Mild therapeutic hypothermia (MTH) has been demonstrated to prevent residual hearing loss from surgical trauma associated with cochlear implant (CI) insertion. Here, we aimed to characterize the mechanisms of MTH-induced hearing preservation in CI in a well-established preclinical rodent model.

Approach:

Rats were divided into four experimental conditions: MTH-treated and implanted cochleae, cochleae implanted under normothermic conditions, MTH only cochleae and un-operated cochleae (controls). Auditory brainstem responses (ABRs) were recorded at different time points (up to 84 days) to confirm long-term protection and safety of MTH locally applied to the cochlea for 20 minutes before and after implantation. Transcriptome sequencing profiling was performed on cochleae harvested 24 hrs post CI and MTH treatment to investigate the potential beneficial effects and underlying active gene expression pathways targeted by the temperature management.

Results:

MTH treatment preserved residual hearing up to 3 months following CI when compared to the normothermic CI group. In addition, MTH applied locally to the cochleae using our surgical approach was safe and did not affect hearing in the long-term. Results of RNA sequencing analysis highlight positive modulation of signaling pathways and gene expression associated with an activation of cellular inflammatory and immune responses against the mechanical damage caused by electrode insertion.

Significance:

These data suggest that multiple and possibly independent molecular pathways play a role in the protection of residual hearing provided by MTH against the trauma of cochlear implantation.

Keywords: Mild therapeutic hypothermia, cochlear implant, hearing loss, inflammation, immune response, RNA sequencing

1. Introduction

Over the past decades, cochlear implant (CI) technology has advanced tremendously providing beneficial effects to nearly a million patients with severe sensorineural hearing loss (FDA 2015). To further enhance the benefits of CIs, latest hybrid or electric-acoustic stimulation (EAS) cochlear implant (CI) devices were designed to combine electrical and acoustic stimulation in the same ear providing high frequency electrical hearing while utilizing the residual low frequencies. Studies have shown that patients who have useful residual hearing in the low-frequencies benefit from EAS-CI with improvements in speech understanding in quiet and noise environments (Skinner et al. 2002; Dorman et al. 2009; Gifford et al. 2013; Dunn et al. 2010) as well as in melody and instrument recognition (Dorman et al. 2008). Unfortunately, despite advances in CI surgical techniques and devices, complications following electrode implantation remains a challenge. Approximately 30–50% of individuals with EAS-CI experience a delayed acoustic hearing loss (greater than 30 dB) post CI (Gstoettner et al. 2009; Gantz et al. 2009). In general, the trauma associated with implant surgery leads to mechanical and vascular damages, inflammation, and loss of remaining sensory hair cells (HC) and spiral ganglion neurons (Eshraghi and Van de Water 2006; van de Water, Dinh, et al. 2010; Bas et al. 2015; Eshraghi et al. 2013). Unfortunately, CI surgery can also lead to postoperative vestibular dysfunction. Previous literature has shown that approximately 30–40% of CI patients experiences vertigo/balance impairment (Enticott et al. 2006; Nayak et al. 2022), however the data on vestibular dysfunction post-CI remains inconclusive.(Cozma et al. 2018; Dhondt et al. 2022) In addition, different studies have reported that direct electrical stimulation and noise exposure affect the normal neural function and structure causing the loss of residual hearing following EAS-CI activation (Reiss et al. 2015; Li et al. 2020; Liang et al. 2019). Thus, a significant focus in the field has been on preserving low-frequencies hearing, so that CI recipients can benefit with improved speech understanding and auditory abilities in daily life.

Inflammation triggered by the electrode array insertion in the inner ear can cause damages to the cochlea structures leading to sustained residual hearing impairment (Nadol and Eddington 2004; Eshraghi and Van de Water 2006; Ueha, Shand, and Matsushima 2012; Seyyedi and Nadol 2014). Several studies have demonstrated that the sensorineural cell death following CI-induced trauma may occur through a variety of pathways. One of these is the intrinsic apoptosis signaling pathway that involves a diverse array of metabolic processes including perturbation of the mitochondrial permeability and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential that leads to production of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), impairment of calcium homeostasis, release of cytochrome C into the cytoplasm and activation of caspase cascade (Eshraghi, Yang, and Balkany 2003; Eshraghi and Van de Water 2006; Dinh et al. 2008; Haake et al. 2009; Ciorba et al. 2010; Eshraghi et al. 2013). Production of ROS known to persist days after cochlear implant (Eshraghi and Van de Water 2006) can affect adaptive immune response modulating the recruitment of activated immune cells and the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines, critical mediators of the extrinsic apoptosis pathway (Diegelmann and Evans 2004; Bas et al. 2015). Recent findings have also shown tissue remodeling as effect of the inflammation process that follow cochlear implant surgery (Zhang, Stark, and Reiss 2015; Tanaka et al. 2014). Although in the past 10–15 years much attention is being focused to improve cochlear implant outcomes and safety, current clinical procedures still provide limited preservation of the residual hearing. Therefore, there is a need to develop novel strategies to minimize inner ear damage after electrode implantation.

Current therapeutic strategies under investigation aim to reduce the deleterious effects of electrode implantation and have ranged from surgical techniques and modified array technology (Kiefer et al. 2004; Roland 2005; Skarzynski et al. 2007; Gstoettner et al. 2008; Dorman et al. 2009; Gantz et al. 2009; Gifford et al. 2013; Gifford et al. 2017) to pharmacological therapies (Van De Water, Abi Hachem, et al. 2010; Vivero et al. 2008; Eshraghi et al. 2010; Eastwood et al. 2010; James et al. 2008). Hypothermia or targeted temperature management as a therapeutic intervention has been demonstrated to improve the outcomes from a variety of injuries, including brain and spinal cord trauma, cerebral ischemia, cardiac arrest and most recently by our group in cochlear implantation-induced trauma (Kawai et al. 2000; Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study 2002; Dietrich, Atkins, and Bramlett 2009; Cappuccino et al. 2010; Levi et al. 2010; Dietrich and Bramlett 2010; Dietrich et al. 2011; Tamames et al. 2016). Our previous pre-clinical studies have demonstrated optimal cooling conditions, such as duration and temporal therapeutic window and targeted temperature of localized MTH for reducing damage associated with implant surgery and preserving residual hearing (Tamames et al. 2016). However, these results were from a short-term study primarily focused on demonstrating efficacy of this approach.

Additionally, the protective mechanisms regulated by MTH have been investigated against various forms of trauma using in vivo (Bernard et al. 2002; Kawai et al. 2000; Shankaran et al. 2005; Dietrich, Atkins, and Bramlett 2009; Cappuccino et al. 2010; Truettner, Suzuki, and Dietrich 2005; Truettner, Bramlett, and Dietrich 2017; Tamames et al. 2016; Dugan et al. 2020), and in vitro models (Fischer et al. 1999; Riess et al. 2004; Singh et al. 2021). In different studies MTH has been shown to prevent inflammatory damages to the tissues by inhibiting both the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis pathways (Maier et al. 1998; Hasegawa et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2010; Yenari and Han 2012). To these regards, MTH have shown to attenuate inflammation by reducing the production of ROS and proinflammatory factors (Horiguchi et al. 2003; Maier et al. 2002; Gu et al. 2014; Dugan et al. 2020). It appeared that MTH alters calcium and adenosine triphosphate signal pathways delaying the neuronal damage (Colbourne et al. 2003) and protects from traumatic brain injury by suppressing activation of caspases (Phanithi et al. 2000; Zhao et al. 2007). In various reports, MTH seemed to downregulate inflammation-related molecules (Han et al. 2002) and to diminish the release of pro-inflammatory chemokines important for immune cells recruitment to the inflammatory area (Ohta et al. 2007). Furthermore, post traumatic MTH reduced the expression of metalloproteinases preventing blood brain barrier (BBB) dismembering, limited the infiltration of circulating blood myocytes and altered the activation of microglia/macrophages to the affected area (Wang et al. 2002; Hamann et al. 2004). In spite of the enthusiasm for the beneficial effects of MTH on CI-induced hearing loss, relatively little is known about its molecular and cellular effects in the inner ear.

The present study extends our previous work by (i) assessing the long-term efficacy and safety of mild therapeutic hypothermia following CI and (ii) by investigating the mechanisms of MTH-induced cellular protection against electrode insertion trauma. Optimizing the methods employed to deliver MTH to the sensorineural cochlear structures, improving the protection afforded to residual hearing function and neural elements, and probing its multifaceted mechanisms will allow for the translation of this approach to the operating room and can support the development of new combinatorial strategies aimed at enhancing the benefits of MTH.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Experimental groups

Normal-hearing male and female Brown Norway rats were acquired to perform this study (Charles River Laboratories). The use of the Brown Norway rats was approved by the University of Miami Animal Care and Use Committee and was in compliance with USDA and NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The animals were divided in four experimental groups for long-term functional assessments: 1) mild therapeutic hypothermia treatment with cochlear implantation (MTH CI), 2) normothermic cochlear implant (Normothermia CI) performed at 37 °C, 3) mild therapeutic hypothermia without cochlear implant (MTH alone), 4) untreated contralateral ears used as control group (CTRL). MTH was provided at the time of the cochlear implant surgery following the protocol established by Tamames et al. study (Tamames et al. 2016). Residual hearing was assessed pre-electrode implantation and up to 3 months post-surgery in a total of 21 rats. In a supplemental study, cochleae from MTH CI, Normothermia CI and untreated CTRL groups were harvested at 24 hrs following cochlear implantation for RNA sequencing and mechanistic studies.

2.2. Surgical procedures and functional assessment

2.2.1. Cochlear implantation procedure

Animals were unilaterally implanted at 3 months of age in typically normal hearing ears for functional assessments. The left cochlea was implanted with an electrode analog of 0.28 mm inserted through the round window (RW). To perform cochlear implant (CI) surgery, animals were anesthetized with an intra-muscular injection of 44 mg/Kg Ketamine and 5 mg/Kg Xylazine. Rectal temperature was maintained and controlled throughout the entire procedure with an electrical heating pad positioned under the animal and a temperature controller. The effect of the anesthesia was considered complete when upon pinching the paw a reflex was absent. The surgery was performed under sterile conditions. As previously described by Tamames et al., 2016, the bulla was exposed through a post- auricular incision and opened to gain access to the round window (RW). The electrode array was inserted for ~5 mm in the scala tympani through the RW. A small piece of muscle fascia was used to fill the bulla and prevent leaking of perilymph. The skin incision was closed with 4–0 sutures. Buprenorphine slow release (SR) (1mg/Kg) was administered as analgesic post-surgery subcutaneously. We observed vestibular behavior post CI procedure in a few animals where circling and head tilt towards the side of the implant were present for 24–48 hrs post electrode insertion. Animals with severe conditions (less than 5%) were excluded from the study.

2.2.2. Mild Therapeutic Hypothermia (MTH) treatment

Mild Therapeutic Hypothermia (MTH) was locally delivered in the inner ear using a Peltier device customized our laboratory. The detailed description of the hypothermia device has been recently published (Tamames et al.,2016). A hollow copper hypothermia probe is coated with gold and is connected to a multi-lumen tubing circulating cold refrigerant (FC-770 Fluorinert, 3M obtained from https://www.besttechnologyinc.com). The refrigerant is cooled using a custom thermoelectric controller and Peltier system (Restor-Ear Devices LLC). The probe is placed in contact with the cochlear bone at the mid-basal turn along with a thermistor (RDXL4SD, Omega) carefully positioned at the round window. The thermistor allowed us to observe the in vivo temperature during the hypothermia application. Localized hypothermia of the cochlea was typically 4–5°C below normal cochlear temperature (36–37°C) and was delivered for a total of 60 minutes during the CI procedure as follows: 12 mins gradual cooling of the refrigerant (from 33°C to 5°C), 20 minutes before and 20 minutes after electrode insertion with the refrigerant maintained at 5°C, and eventually rewarming the refrigerant for 12 min (from 5°C back to 33°C). MTH was delivered with the same protocols in groups 2 and 3 where we tested its efficacy and safety.

2.2.3. Functional Assessments

Auditory Brain Stem Responses (ABR) were recorded from anesthetized animals at different time points: before cochlear implantation procedure (“Pre-CI”) and 2, 4, 7, 14, 28, 56 and 84 days post-surgery in all groups. ABRs were acquired in a sound proof booth at acoustic tone of 0.5,1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 24, 32 kHz frequencies using 1024 sweeps of tone bursts of a rate of stimulation of 21.1 Hz amplified using the Opti-Amp bioamplifier from Intelligent Hearing Systems (IHS, Miami, FL) connected to the Smart EP system. Sound frequencies were delivered through speakers placed into the rat ear canals. Hearing function were recorded by the negative, positive and ground electrodes of the Smart EP system. The negative electrodes were placed in the superior post auricular area, the positive electrode in the vertex of the head, and the ground electrode in the left limb. Evoked responses were averaged from 1024 stimulus at each decibel intensity of 80 dB and decreasing by 10 dB steps until no auditory responses were detected. The hearing threshold was defined as the lowest intensity stimulus which evoke a repeatable and detectable wave 1 response. The data collected from ABR recordings were also analyzed by a researcher who was blinded to the experimental group and to the animal number.

2.3. Cochlear transcriptome analysis

2.3.1. Tissue preparation and RNA extraction

Twenty-four hrs post- MTH CI and Normothermic CI surgeries, N=10 rats (N=4 MTH CI; N=3 Normothermia CI; N=3 CTRL) were euthanized. Whole cochlea tissues were harvest under DNA/RNA free condition and stored at −80°C in cryotubes for 1 day. RNA was extracted from whole cochlea tissue on DNA/RNA free working area using Direct-zol RNA MicroPrep Kit (Zymo Research, R2060). Cochleae were transferred from −80°C to ice and incubated with 1 ml of cold TRIzol (Invitrogen 15596026). Cochleae were homogenized on ice for 10–15 seconds followed by centrifugation at 4 °C for 12 minutes at 12,000 rpm. Supernatant was collected in DNA/RNA free 2 ml tubes and 800 ul of iced cold 100% EtOH were added. The mixture was transferred into a Zymo-microspin column (up to 700 ul) and centrifuged at room temperature (RT) for 60 sec at 11,000 rpm. The procedure was repeated until no mixture was left in 2 ml tubes. 400 ul of RNA Wash Buffer was added to each column that were than centrifuged at RT for 60 sec at 11,000 rpm. In an RNase-free tube 5ul of DNase I was mixed with 35 ul of DNA digestion buffer for each sample. The cocktail (40 ul) was added to each column followed by an incubation period of 15 min. The samples were then centrifuged at RT for 60 sec at 11,000 rpm. 400 ul of RNA Pre- wash were added to the column and centrifuged at RT for 60 sec at 11,000 rpm. This step was repeated until no mixture was left into the columns. 700 ul of RNA Wash Buffer were added to the columns and centrifuged for 2 min at RT. The columns were transferred in a fresh DNA/RNA free 1.5 ml tube. 20 ul of DNA/RNA free water (Invitrogen 10977–015) were added to the center of each columns. After 3 min of incubation, the samples were centrifuged for 2 minutes at RT for 60 sec at 11,000 rpm. RNA concentration was measure with a NanoVue Plus Nanodrop (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Samples were then stored at −80°.

2.3.2. RNA sequencing

Next-generation sequencing (RNA-seq) was used to analyze the whole cochlear transcriptome between three groups: CTRL, normothermic CI and MTH CI at 24 hrs following CI. The library size was 300bp and the sequencing read length was 150×8×8×150; samples were run on the Illumina Hiseq platform. Raw fastq samples were aligned to the Rattus norvegicus genome (Rnor6.0) and annotated (TopHat v2.1.0 and Bowtie2 v2.2.6). The aligned read data was sorted using samtools and counted using HTSeq-count (v0.5.4) in Python. Read-count matrices were read into R and processed using the ‘edgeR’ package (v3.26.4). A multi-dimensional scaling plot was generated from calculated distances between samples based on the top 500 genes with the greatest variance across samples. For differential expression testing, negative binomial generalized linear models (GLMs) were fitted with estimated gene dispersions and differential expression determined using the GLM likelihood ratio test with a 5% false discovery rate.

2.3.3. Pathway Analysis

Gene ontology analysis was performed using DAVID bioinformatics resources 6.8 (ref) to determine whether biological processes were enriched within a list of genes. Differentially expressed genes with FDR < 0.05 were used as input. GO enriched pathways with a p-value less than 0.05 were considered in the study. Molecular interaction network of transcripts belonging to the top enriched GO categories of MTH CI vs Normothermia CI experimental condition was extracted using STRING 11.0.

2.5. Statistical Analysis for ABR

The statistical analysis related to ABRs data were conducted in Excel and Origin (OriginLab Corp.) using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. *p<0.5, **p< 0.05–0.01, ***p<0.01; ns= not statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Protective effects of MTH are sustained over a long-term period following cochlear implant-induced trauma

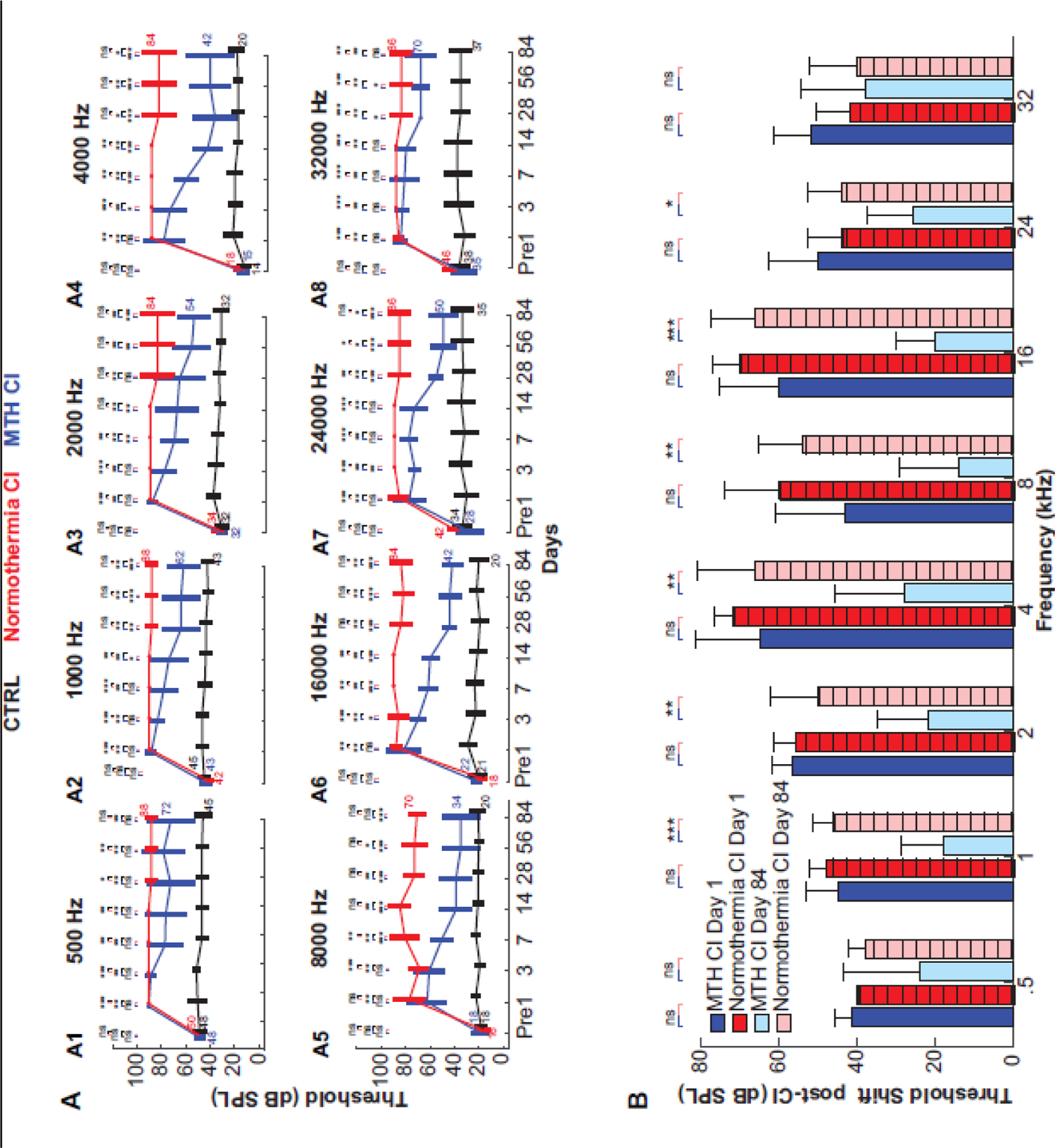

As previously shown, localized MTH prevents hearing impairment in cochlea rats up to 28 days post electrode implantation (Tamames et al. 2016). To test a prolonged protective effect of MTH treatment, we compared hearing thresholds (mean ± SD) prior (Pre) and up to 84 days post-CI surgery between three experimental conditions: MTH CI, Normothermia CI and untreated, contralateral cochlea (CTRL) (Figure 1). The ABRs were carried out at normal body temperatures of 37 °C and at frequencies between 0.5 and 32 kHz and at different time points (2, 4, 7, 14, 28, 56, 84 days). The data presented in Fig. 1A show an increase of 54 ± 12.51 dB over pre-surgical levels in hearing thresholds of Normothermic CI group at day 1 post- surgery for frequencies across the tonotopic map (Fig.1 A1-A8). The results were compared to those before (Pre) Normothermic CI surgery and to the contralateral cochlea (black line). An increase of hearing thresholds was also observed for MTH CI cochlea at day 1 following CI (51.6 ± 8.35 dB) as results of the trauma to the inner ear. In the Normothermic CI condition, hearing impairment persisted until day 84 (an increase of 50.5 ± 10.83 dB over pre surgical levels), whereas MTH CI showed a recovery by day 3 at 16 kHz (70 ± 6.3 dB), day 7 at 2, 4 and 8 kHz (70 ± 10.95 dB, 61.6 ± 9.83 dB and 50 ± 8.9 dB respectively), day 14 at 1 kHz (74 ± 15.1 dB) and day 28 at 24 and 32 kHz (56 ± 5.4 dB and 70 ± 0 dB, respectively). The hearing threshold of the contralateral cochleae (CTRL) did not change significantly (3.02 ± 5.01 dB at day 1 and 0.2 ± 2.8 dB at day 84) across the frequencies. Figure 1B shows the threshold shifts in hearing from pre-surgical baseline at day 1 and 84 for Normothermia CI and MTH CI groups. Next, hearing thresholds shift of Normothermia CI and MTH CI were normalized to those of the contralateral cochleae (CTRL). In less than 5% of normothermic CI animals, the presence of vestibular disfunction manifested as a head tilt. In limited severe cases, circling was observed for the first 48 hrs. These animals we removed from the study for further assessment. None of the MTH-treated and implanted animals showed vestibular dysfunction.

Figure 1.

Efficacy of MTH against trauma caused by electrode implant. A1-A8) Auditory brain stem response (ABR) measurements of Brown Norway rats at different frequencies (0.5, 1, 2, 4 8, 16, 24, 32 KHz) recorded before CI and MTH treatments and at days 3, 7, 14, 28, 56, 84 post trauma and MTH delivery. ABR hearing thresholds were compared between three groups: cochlea implant (CI) normothermic condition (red line), cochlea implant MTH (blue line) and non-treated contralateral ear as control (black line). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. N=5 CI normothermia, N=6 MTH CI, N=12 control cochleae at 0.5, 1 and 2 KHz; N=4 CI normothermia, N=6 MTH CI, N=11 control cochleae at 4 KHz; N=5 CI normothermia, N=5 MTH CI, N=11 control cochleae at 8, 16, 24, 32 KHz. *p<0.5, **p< 0.05–0.01, ***p<0.01 determined by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. B) Hearing threshold shifts from pre-surgical baseline at day 1 and 84 following CI normothermic and CI MTH treatments. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. *p<0.5, **p< 0.05–0.01, ns= non statistically significant.

3.2. MTH is safe

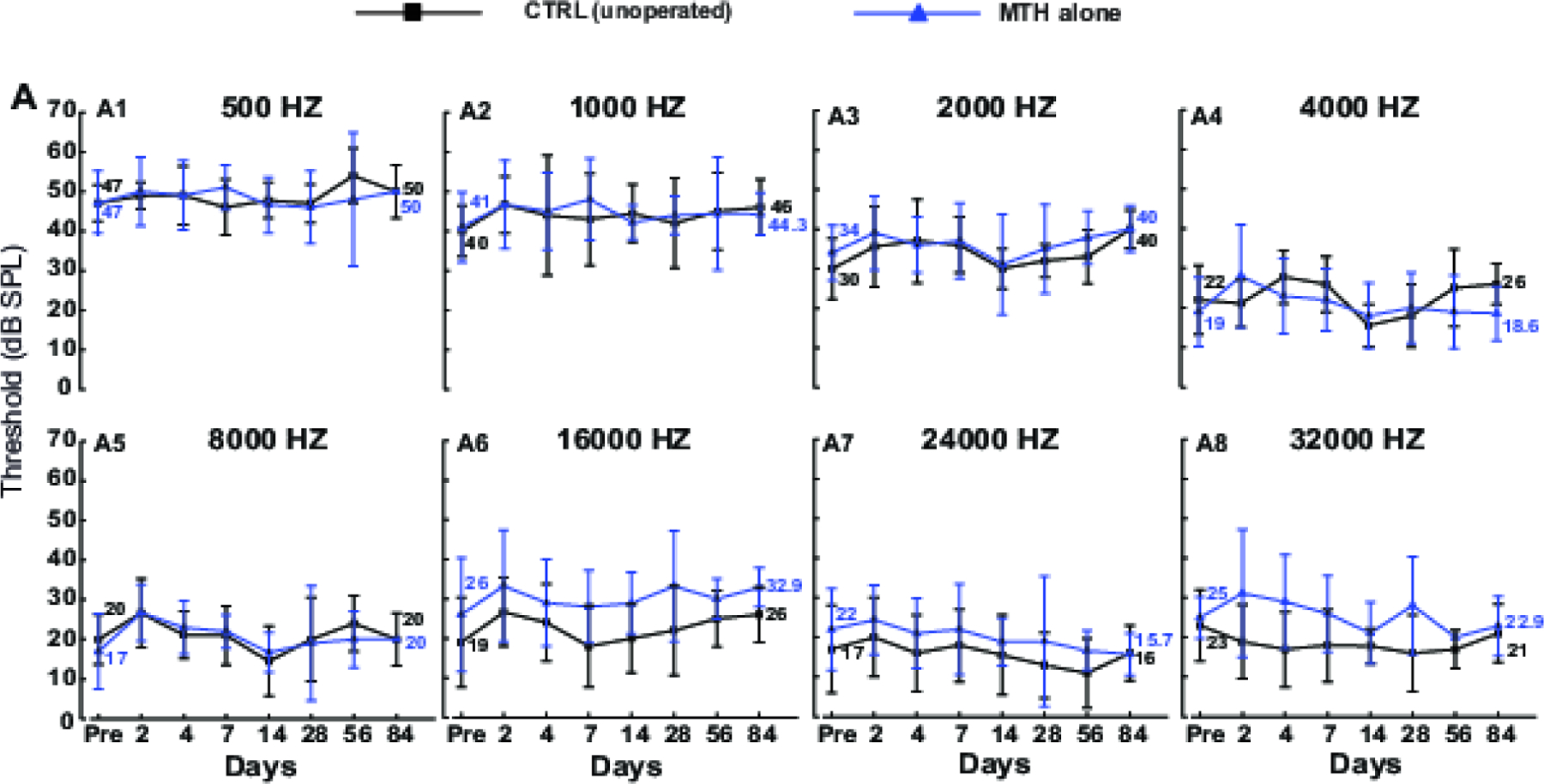

In order to establish the safety of localized MTH, we compared hearing thresholds of inner ear treated with MTH alone (temperature of the cochleae reduced with the hypothermia probe as previous experiments but no CI was performed) with those of unoperated contralateral cochleae. ABR were measured at frequencies between 0.5 and 32 kHz and at different time points (2, 4, 7, 14, 28, 56, 84 days). As shown in Figure 2, MTH by itself did not adversely affect the cochlear function. The hearing thresholds of MTH cochleae were comparable to those of contralateral ear used as control across frequencies. With MTH, the average hearing thresholds at day 2 and 84 were 34.8 ± 9.4 dB and 34.6 ± 12.7 dB respectively. In comparison, the thresholds in unoperated contralateral cochlea were 30.69 ± 11.83 dB day 2 post-surgery and 30.6 ± 12.88 dB at day 84. The differences were not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Safety of localized MTH. A1-A8) Auditory brain stem response (ABR) measurements of Brown Norway rats at different frequencies (0.5, 1, 2, 4 8, 16, 24, 32 KHz) recorded before and post (at days 3, 7, 14, 28, 56, 84 days) MTH delivery. ABR hearing thresholds were compared between two groups: MTH only (blue line) and non-treated contralateral ear as control (black line). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. MTH alone and CTRL, N=10 except for days 2 and 14 (N=9).

3.3. RNA-seq following cochlear implant and MTH treatment

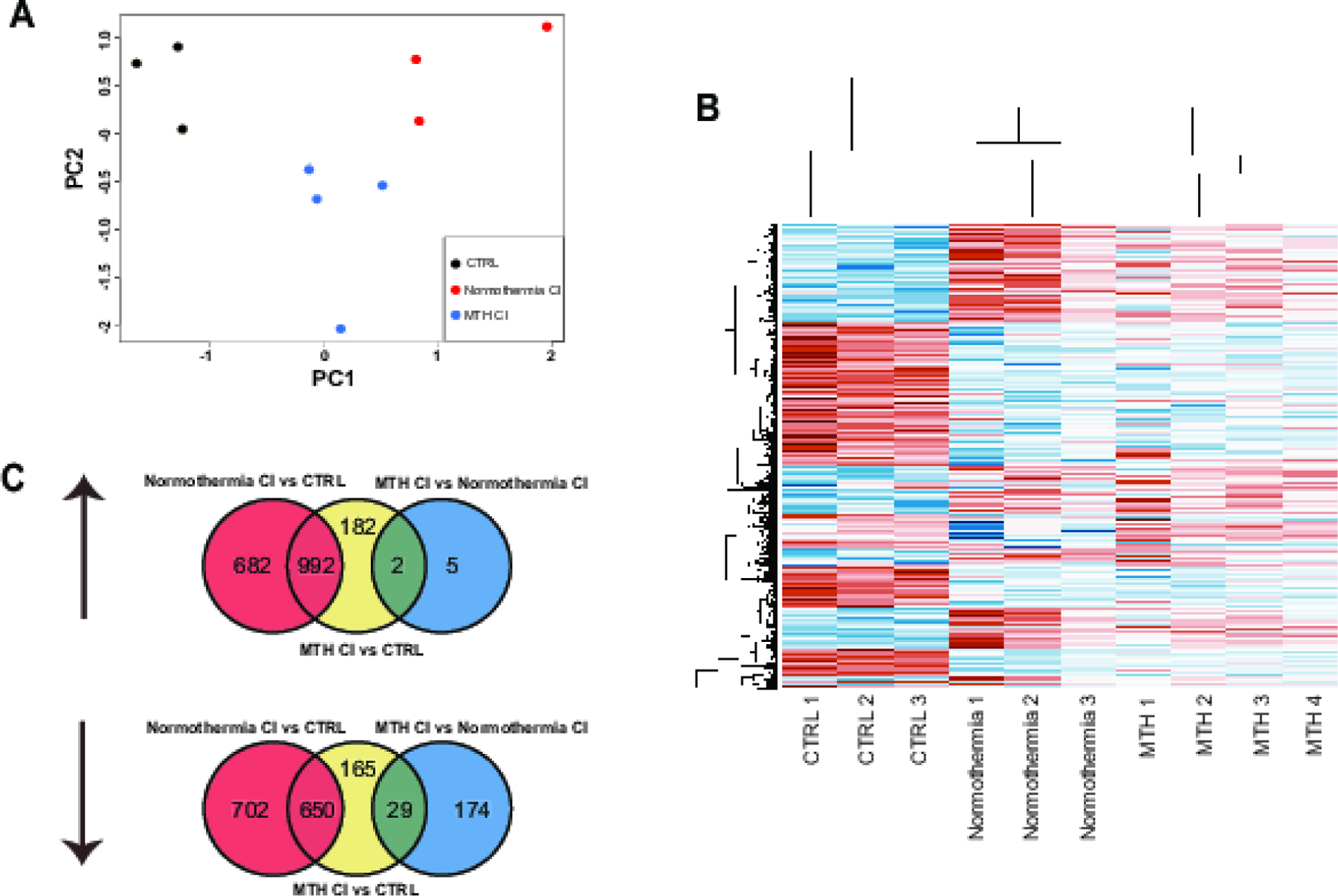

Our next goal was to investigate the differences in gene expression between CI cochleae treated with MTH (MTH CI), cochleae implanted with electrode at normothermic condition (Normothermia CI) and control cochleae (CTRL). We performed RNA-sequencing and analysis from cochlear samples collected at day 1 from a different set of animals and compared the gene expression between the three groups. ~ 40 million paired-end reads were obtained for each cochlear sample, with 50–60% of the read pairs mapping confidently to the rat reference genome. In the principal component analysis, MTH samples were embedded between Normothermia samples and CTRL samples along principal component 1, suggesting MTH attenuated the largest source of gene expression variation i.e. the effect of cochlear implantation. Reduced expression of CI-induced genes by MTH samples in our heatmap support a similar finding. Pair-wise differential expression tests between treatment groups were performed in EdgeR. (Fig.3A and 3B). Out of 3026, 2020 and 210 differentially expressed genes (DEG) in Normothermic CI vs CTRL, MTH CI vs CTRL, MTH CI vs Normothermic CI, 682, 182 and 5 of upregulated genes were unique in Normothermic CI vs CTRL, MTH CI vs CTRL and MTH CI vs Normothermic CI respectively. In comparison, 702, 165 and 174 genes were downregulated in Normothermic CI vs CTRL, MTH CI vs CTRL and MTH CI vs Normothermic CI respectively (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Transcriptome analysis of whole cochlea RNA extracted from MTH CI, Normothermia CI and Control groups. A) Principal component for all the genes replicates of MTH CI, Normothermia CI and Control cochleae. B) Hierarchical clustering analysis of differentially expressed genes for all replicates of MTH CI, Normothermia CI and Control cochleae. Blue colors denote upregulated gene and red colors denote downregulated genes. C) Venn diagram showing upregulated and downregulated genes expressed in MTH CI, Normothermia CI and Control cochleae.

3.4. MTH regulates a significant number of genes in the cochlea

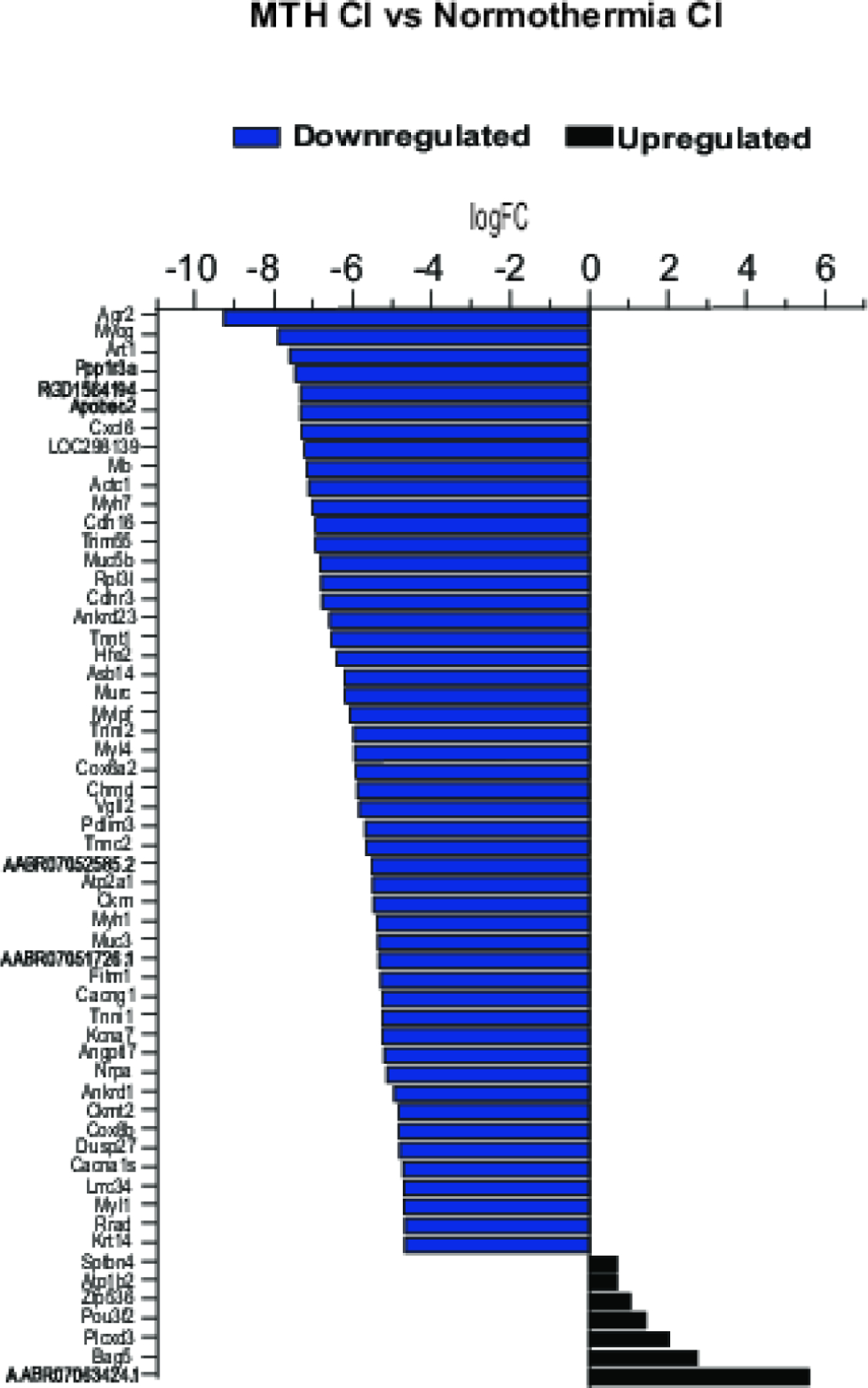

Here we aimed to characterize the gene expression profile in MTH CI vs CTRL, Normothermic CI vs CTRL and MTH CI vs Normothermic CI experimental conditions. For this purpose, we explored the differentially expressed genes in all three groups. Figure 4 shows the expression level of the top 50 upregulated and the 7 downregulated genes expressed between MTH CI and Normothermic CI groups. The results obtained show that the most downregulated expressed genes were Arg2, Myog, Art1, Ppp1r3a, RGD1564194, Apobec2, Cxcl6; whereas the upregulated gene in MTH CI vs Normothermic CI were AABR0706324.1, Bag5, Plcxd3, Pou3f2, Zfp536, Atp1b2, Sptbn4. Supplementary Figure 1 shows the most 25 down- and up-regulated genes in Normothermic CI vs CTRL (Suppl. Figure 1A) and MTH CI vs CTRL (Suppl. Figure 1B). Interestingly, among the most differently expressed genes in MTH CI vs Normothermia CI, Myog, Cdh16, Trim55, Muc3, Ankdr1 and Rrad genes are downregulated in MTH CI vs Normothermia CI (Fig.4) and upregulated in Normothermia CI vs CTRL (Suppl. Fig. 1A). Moreover, as shown in graphs in Suppl. Figure 1 the majority of the genes abundantly expressed in one group are also highly expressed in the other: LOC100360690, Tff2, Lipf, Bpifp2, Bpifp1, Mroh5, Shisa8, Charna5, Csap1, Fhl5, Gp2, Cxcl3, Cxcl2, Csf3, Clca4l, Fosl1, RGD1305184, Has1, Slpi.

Figure 4.

RNA-seq gene expression of top 50 downregulated and the only 7 upregulated genes in MTH CI vs Normothermia CI.

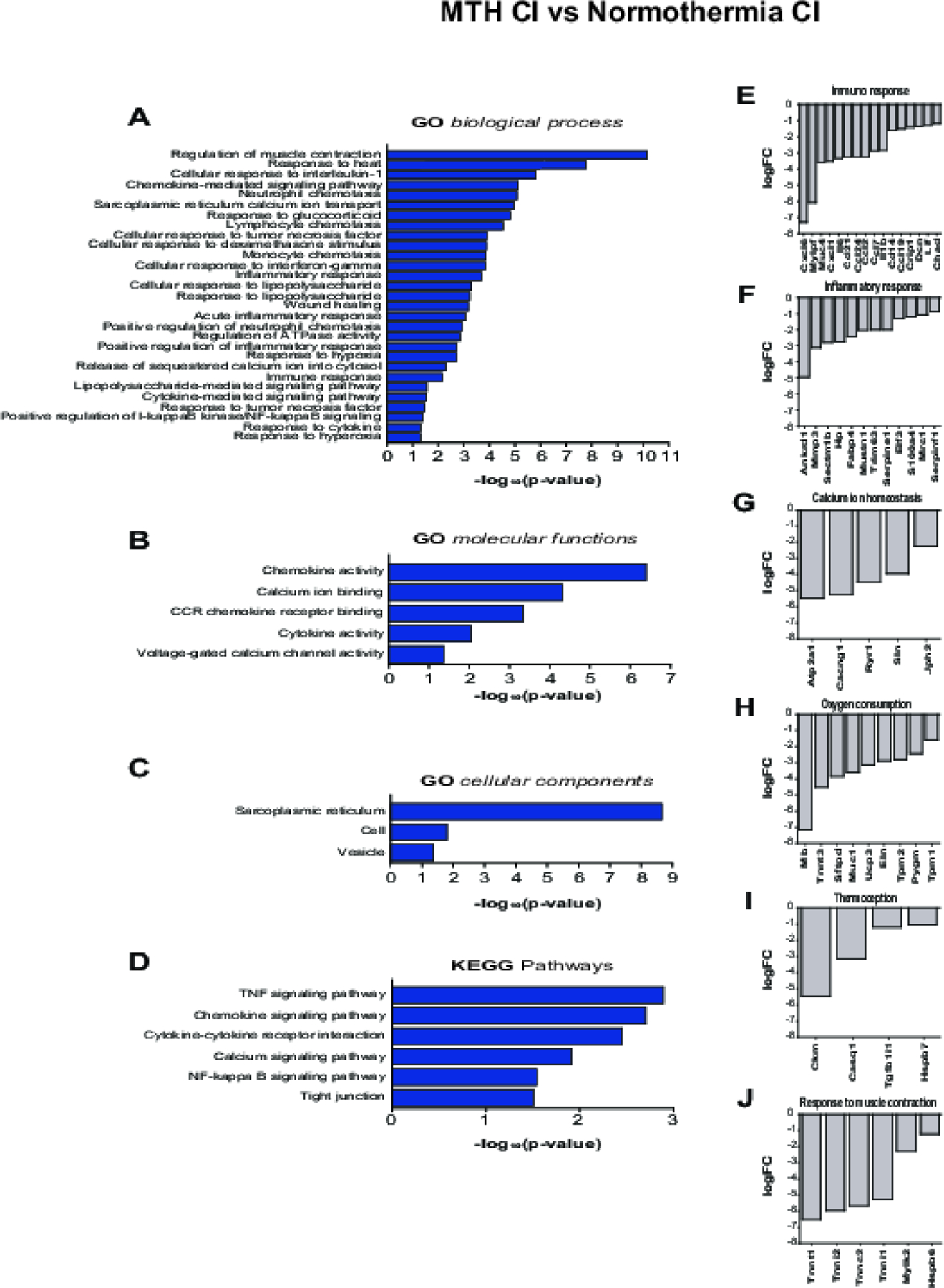

3.5. MTH modulates secondary injury pathways after CI-induced trauma

To investigate the protective mechanisms afforded by MTH following a CI, we performed gene ontology enrichment analysis on the unique downregulated genes of MTH CI vs Normothermia CI (FDR<0.05) using DAVID bioinformatics resource 6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) (Huang da, Sherman, and Lempicki 2009a, 2009b)(Figure 5 A–C). Among the diverse range of GO biological processes there are pathways associated with regulation of muscle contraction, response to heat, cytokine- and chemokine- mediated signaling pathway, inflammatory response, immune response, immune cells chemotaxis, cellular response to interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signaling pathway, NFkβ signaling pathway, response to glucocorticoid, cellular response to dexamethasone stimulus, liposaccharide and interferon-gamma, wound healing, calcium homeostasis, response to hypoxia and hyperoxia and cellular response to ATP (Fig. 5A). Analysis of GO molecular function revealed an enrichment of chemokine and cytokine activity, CCR chemokine receptor binding, calcium ion binding and voltage-gated calcium channel activity (Fig. 5B). Whereas sarcoplasmic reticulum, cell and vesicle are the most enriched cellular components (Fig 5C). Chemokine, TNF, NFkβ and calcium signaling pathways, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction and tight junction are the most enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways (Fig. 5D). Figures 5E–J shows fold changes of the transcripts related to GO biological processes only and categorized into the following groups: immune response (Fig. 5E), inflammatory response (Fig. 5F), calcium ion homeostasis (Fig. 5G) and oxygen consumption (Fig. 5H), thermoception (Fig. 5I) and response to muscle contraction (Fig 5J).

Figure 5.

Gene ontology analysis of downregulated genes from MTH CI vs Normothermia CI. A-D) GO biological processes (A), GO molecular functions (B), cellular components (C), KEEG pathways (D) of MTH CI vs Normothermia CI downregulated genes, represented as log10(p-value). E-J) Top differentially expressed MTH CI vs Normothermia CI genes listed in GO biological processes and related to Immune response (E), Inflammatory response (F), Calcium homeostasis (G), Oxygen consumption (H), Thermoception (I) and Response to muscle contraction (J). Differentially expressed genes (FDR adj_pvalue<0.5) were analyzed using DAVID informatics program considering p<0.05 as statistically cutoffs limit.

The most enriched genes associated with the immune response are Cxcl6, Mylpf, Muc4, Cxcl1, Il6, Ccl21, Ccl24, Ccl2, Ccl7, Il1b, Cd14, Ccl19, Crip1, Dcn, Lif and Chad (Fig. 5E). Among the downregulated genes related to inflammatory response, the most differentially expressed are Ankdr1, Mmp3, Sectmbp1, Hp, Fabp4, Mustn1, Trim63, Serpine1, Elf3, S100A4, Mrc1 and Serpinf1 (Fig. 5F). ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting1 (Atp2a1), calcium voltage-gated channel auxiliary subunit gamma 1 (Cacng1), Ryanodine receptor 1 (Ryr1), sarcolipin (Sln) and Junctophilin 2 (Jph2) are the highly expressed genes related to calcium homeostasis (Fig. 5G), whereas Mb, Tnnt3, Sftpd, Muc1, UCP3, Eln, Tpm2, Pygm and Tpm1 are the most down-regulated genes of oxygen consumption (Fig. 5H). Creatine kinase, M-type (Ckm), calsequestrin 1 (Casq1), transforming growth factor beta 1 induced transcript 1 (Tgfb1i1), heat shock protein family B member 7 (Hspb7) are the genes involved in the response to heat (Fig. 5I) whereas Tnnt1, Tnni2, Tnnc2, Tnni1, Mylk2 and Hspb6 are the genes responsible for the response of muscle contraction (Fig. 5J).

We also performed GO enrichment analysis of the Normothermia CI vs CTRL (Suppl. Figure 2) and MTH CI vs CTRL (Suppl. Figure 3) up- and down-regulated transcripts. As presented in Suppl. Figure 2 and Table 1, genes up-regulated in Normothermia CI vs CTRL experimental condition are mainly enriched in inflammatory, immune and hypoxia response, immune cell chemotaxis, chemokine and cytokine mediated signaling pathway, response to oxidative stress, Hif-1 and Nfkβ signaling pathway, angiogenesis, aging, response to mechanical stimulus, NAPDH oxidase and glutathione peroxidase activity, hydrogen biosynthetic and catabolic process, cell, sarcoplasmic reticulum, vesicle, ATPase binding and regulation of calcium ion transport (Suppl. Fig. 2 A–D and Table 1). Further GO enrichment shows that downregulated genes are involved in functional categories such as myelination, oligodendrocyte and glial cell differentiation, synapse formation, synaptic and chemical transmission, GABAergic, glutamatergic, dopaminergic and cholinergic synapse, regulation of post synaptic membrane potential, vesicle endo- and exocytosis, neurotransmitter secretion, sensory perception of pain, ion homeostasis, calcium signaling pathway and ATPase activity (Suppl. Fig. 2 A–D and Table 2). Moreover, Suppl. Figures 2 E and F indicate that the most abundant up-regulated Normothermia CI vs CTRL genes are Il1a, CxCl6, Ccl20, Ccl12, Has2, Il1β, Ccl24, Ccl19 associated to immune response and Il24, Scgb1a1, Tp73, Mm12 and Selp related to inflammatory response. As shown in Table 1 Mb, Muc1, Ryr1, Ucp3 and Plau are the highest expressed oxygen consumption genes; Cav3, Sln and Adora2a are involved in ion homeostasis while Mmp7, Bcl2a1, Kirt4 and Eno3 are some of the genes associated with aging; Ankrd23 and Acta1 and Inhbb are involved with the response to mechanical stimulus while Lvm, Taca4, Itgb2, Hspb1 and Cyr61 with vasoconstriction. Whereas, the most differentially expressed downregulated Normothermia CI vs CTRL genes (Suppl Fig. 2 G–I and Table 2) are: Pou3f2, Gjc3, Adam22, Mbp and Scn2a (Myelination); Gucy1a, Wnk3, Dlgap2, Rims4 and Ptprn2 (Synaptic transmission), Grin3a, Unc5d, Pak3, Tnr and Rnf165 (Neural circuit formation), Rims4, Chrna7, Grin2c, Slc8a1, Slc5a5 (Ion transport), Oprl1, Dlg2 and Kcnip3 (Sensory perception of pain), , Plp1, Sox6, Dner and Ntk2 (Glia differentiation), Myh9, Rab3c, Pclo,Trim9 and Clip3 (Vesicle endo-and exocytosis).

Table 1. Normothermia CI vs CTRL upregulated genes.

List of upregulated GO biological processes and genes from Normothermia CI vs CTRL. Differentially expressed genes (FDR adj_pvalue<0.5) were analyzed using DAVID informatics program considering p<0.05 as statistically cutoffs limit.

| Biological Processes | Upregulated Genes | pvalue | −log10(pvalue) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Response | CD8A, CCL9, NFKB1, CXCL6, TAC4, CCL6, CCL24, SLC11A1, S1PR3, TNFRSF1B, CCL20, MEFV, CCL21, IL1B, ADAM8, IL1A, CSF1R, IRAK2, SELP, TLR10, OLR1, HCK, AXL, ANXA1, CCL19, IL24, PTGFR, NLRP3, ECM1, TP73, EPHA2, CHST1, CCL12, CYBA, CYBB, CCR5, NFE2L2, PTAFR | 6.41E-12 | 11.193 |

| Cellular response to lipopolysaccharide | MRC1, AXL, NFKB1, CXCL6, IL24, NLRP3, CDK4, PLSCR1, TNFRSF1B, CCR5, CCL20, CD80, PLSCR3, IRF8, PDE4B, IL1B, RARA, ENTPD1, PLAU, ADAM9, FN1 | 8.92E-07 | 6.050 |

| Neutrophil chemotaxis | CCL24, CCL12, CCL20, CCL21, PDE4B, CCL9, IL1B, CCL19, ITGB2, TREM1, FCGR2A, CCL6 | 3.09E-06 | 5.511 |

| Lymphocyte chemotaxis | CCL24, CCL12, CCL20, CCL21, CCL9, CCL19, ADAM8, CCL6 | 5.17E-06 | 5.286 |

| Response to lipopolysaccharide | SELP, NCF2, HP, PAWR, IL6R, CXCL6, PTGFR, SCGB1A1, GCH1, SLC11A1, TNFRSF1B, PLA2G4A, THBD, CCR5, MEFV, RPL13A, KCNJ8, IL1B, ADAM17, ENTPD1, LOXL1, IL1A, MGST1, CHUK, AKIRIN2, PTAFR | 9.47E-06 | 5.024 |

| Cellular response to interleukin-1 | HES1, INHBB, CCL24, CCL12, CCL20, CCL21, CCL9, CCL19, HAS2, NFKB1, PAWR, PPP4C, FN1, CCL6 | 2.42E-05 | 4.615 |

| Wound healing, spreading of epidermal cells | ACVRL1, PLET1, ITGA5, ADAM17, HBEGF, MMP12 | 2.76E-05 | 4.559 |

| Monocyte chemotaxis | CCL24, CCL12, CCL20, CCL21, CCL9, ANXA1, CCL19, CCL6 | 7.62E-05 | 4.118 |

| Leukocyte cell-cell adhesion | SELP, EZR, OLR1, ITGA5, ITGB2, MSN, ITGB1 | 1.45E-04 | 3.839 |

| Cellular response to tumor necrosis factor | CCL9, YBX3, CCL19, NFKB1, CCL6, CCL24, HES1, CCL12, CYBA, CCL20, CCL21, HAS2, NFE2L2, ENTPD1, CHUK | 1.58E-04 | 3.802 |

| Cellular response to interferon-gamma | CCL24, MRC1, CCL12, CCL20, RPL13A, CCL21, CCL9, CCL19, DAPK3, CCL6 | 1.89E-04 | 3.723 |

| Positive regulation of cell migration | COL18A1, PLET1, LYN, DIAPH1, ELP5, MMP14, ITGB1, DAPK3, KDR, CCL24, ITGA5, ETS1, ADAM17, HBEGF, HAS2, PLAU, CSF1R, CYR61, FN1 | 2.03E-04 | 3.692 |

| Positive regulation of inflammatory response | CCL24, CCL12, PLA2G4A, TLR10, CCR5, ETS1, CCL9, CTSS, ADAM8, CCL6 | 2.43E-04 | 3.614 |

| Response to hypoxia | MUC1, TF, ACVRL1, NOL3, CLDN3, CRYAB, HP, PDLIM1, MMP14, KDR, CYBA, ECE1, PYGM, UCP3, ETS1, RYR1, ADAM17, ADSL, IL1B, PLAU, IL1A, MB | 3.35E-04 | 3.475 |

| Positive regulation of angiogenesis | CCL24, CYBB, ACVRL1, ETS1, HSPB1, IL1B, ITGB2, NFE2L2, ECM1, IL1A, ANXA3, CYR61, KDR | 5.79E-04 | 3.237 |

| Chemokine-mediated signaling pathway | CCL24, CCL12, CCR5, CCL20, CCL21, CCL9, CCL19, CXCL6, CCL6 | 6.05E-04 | 3.218 |

| Aging | NCF2, CRYAB, BCL2A1, COL3A1, ELN, MMP7, ITGB2, HP, SLC34A2, RPL29, KDR, GPX1, TNFRSF1B, PLA2G4A, CCR5, UCP3, GPX4, KRT14, HSPB1, ENO3, CTSC, NFE2L2, RNPEP | 0.0010 | 2.981 |

| Wound healing | KLF6, CORO1B, SLC11A1, FGF7, CCL20, TNC, COL3A1, IL1B, IL24, IL1A, PLAU, MMP12, FN1 | 0.0011 | 2.951 |

| Immune system process | OLR1, ETS1, CD300A, MAP3K8, AXL, HP | 0.0013 | 2.890 |

| Response to glucocorticoid | ANXA1, HP, IL6R, TRIM63, SCGB1A1, ANXA3, WNT7B, PLA2G4A, UCP3, SFTPD, IL1B, ADAM9, FN1 | 0.0018 | 2.748 |

| Positive regulation of I-kappaB kinase/NF-kappaB signaling | S100A4, BCL10, NOD1, CCL21, GOLT1B, IL1B, GJA1, CCL19, FKBP1A, SECTM1B, ECM1, IL1A, CHUK | 0.0056 | 2.250 |

| Positive regulation of interleukin-6 production | CYBA, NOD1, CCR5, IL1B, IL6R, IL1A, AKIRIN2 | 0.0064 | 2.194 |

| Response to mechanical stimulus | ACTB, INHBB, ANKRD23, ACTA1, ETS1, TNC, COL3A1, LMNA, MMP14, SMPD2 | 0.0084 | 2.075 |

| Negative regulation of leukocyte apoptotic process | CCL21, HCLS1, CCL19 | 0.0106 | 1.976 |

| Regulation of inflammatory response | LYN, DUOXA2, DUOXA1, GPX4, ANXA1, NLRP3, SCGB1A1 | 0.0152 | 1.818 |

| Response to wounding | PTPN6, GPX1, ETS1, TNC, VCAN, PAWR, FABP5, FN1 | 0.0180 | 1.744 |

| Hydrogen peroxide catabolic process | GPX1, GPX3, DUOX1, PRDX5 | 0.0212 | 1.673 |

| Negative regulation of inflammatory response | TNFRSF1B, MEFV, SMPDL3B, ETS1, ADORA2A, NFKB1, NLRP3, IL22RA2 | 0.0243 | 1.614 |

| Response to oxidative stress | GPX1, RBPMS, ATOX1, GPX4, GPX3, BTG3, DUOX1, PRDX5, MSRB1, NFKB1, MMP14 | 0.0259 | 1.587 |

| Innate immune response | BCL10, TLR10, LYN, HCK, AXL, ANXA1, MSRB1, NFKB1, APOBEC3B, CYBA, CYBB, TMEM173, SFTPD, CLEC5A, AKIRIN2, CSF1R | 0.0312 | 1.505 |

| Positive regulation of BMP signaling pathway | HES1, ACVRL1, PELO, CYR61, KDR | 0.0319 | 1.496 |

| Hydrogen peroxide biosynthetic process | CYBA, CYBB, DUOX1 | 0.0348 | 1.459 |

| Positive regulation of interleukin-6 biosynthetic process | TLR10, IL1B, PTAFR | 0.0348 | 1.459 |

| Regulation of calcium ion transport | CAV3, ORAI1, SLN, ADORA2A, GJA1 | 0.0349 | 1.458 |

| Cytokine-mediated signaling pathway | KLF6, DUOX1, IL1B, FKBP1A, IL2RG, IL6R, CSF2RA, IL1A, CSF1R, IL22RA2 | 0.0437 | 1.360 |

| Response to hydrogen peroxide | GPX1, PLA2G4A, OLR1, CRYAB, HP, MB, ADAM9 | 0.0474 | 1.324 |

| Regulation of blood pressure | CYBA, ACVRL1, ECE1, LVRN, TAC4, GCH1 | 0.0480 | 1.319 |

| Response to hormone | GPX1, PLA2G4A, LYN, HCLS1, ANXA1, MMP14, MUC3, MB | 0.0495 | 1.306 |

Table 2. Normothermia CI vs CTRL downregulated genes.

List of downregulated GO biological processes and genes from Normothermia CI vs CTRL. Differentially expressed genes (FDR adj_pvalue<0.5) were analyzed using DAVID informatics program considering p<0.05 as statistically cutoffs limit.

| Biological Processes | Downregulated Genes | pvalue | −log10(pvalue) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myelination | PLP1, SCD2, MPDZ, SCN2A, NFASC, LGI4, CNTNAP1, PLLP, PMP22, MEGF10, GJC3, GAL3ST1, MBP | 8.13E-08 | 7.090 |

| Axonogenesis | FGFR2, ADCY1, SNAP91, NDN, NTNG1, CNP, BRSK1, SLITRK1, RNF165, ANK3, PAK3, MAPT, MAP2, POU4F2, LRFN5, DST, APC | 7.43E-07 | 6.129 |

| Axon guidance | MATN2, ENAH, KIF5A, NFASC, DPYSL5, L1CAM, ALCAM, ROBO1, ANK3, CRMP1, POU4F2, MAPK8IP3, ETV1, RELN, UNC5D, APBB1 | 4.67E-05 | 4.331 |

| Intracellular signal transduction | PRKCZ, ARHGEF28, PRKAG2, PREX2, DSTYK, KIT, BRSK1, MCF2L, PLCL1, PDPK1, DGKE, PAK3, GUCY1A2, GUCY1A3, PLCB1, DCX, SHC4, SRPK2, MPDZ, SPSB4, NPR2, WNK3, MAST1, ADCY9, CDC42BPA, RGS6, CHN2, UNC13A | 7.21E-05 | 4.142 |

| Neurotransmitter secretion | PPFIA3, SNAP91, SYN1, PTPRN2, BRSK1, RIMS4, UNC13A, NSF | 8.90E-05 | 4.051 |

| Positive regulation of synaptic transmission | PRKCZ, CLSTN2, CLSTN3, GRIK2, CLSTN1, SNCA, DLG4 | 1.55E-04 | 3.810 |

| Long-term synaptic potentiation | PRKCZ, TNR, SYT12, NTRK2, SNCA, NLGN1, NLGN3, RELN, UNC13A | 1.71E-04 | 3.768 |

| Positive regulation of synapse assembly | SLITRK1, FLRT1, CLSTN2, CLSTN3, CLSTN1, NTRK2, NLGN1, NLGN3, ADGRL1, LRRC24 | 2.58E-04 | 3.589 |

| Chemical synaptic transmission | SNAP91, CLSTN2, OPRL1, GRIK2, CLSTN3, SNCA, SLC12A5, CACNB4, HCRTR2, GLS, EXOC4, APBA2, LRP8, CACNA1A, DLG2 | 0.0011 | 2.977 |

| Protein localization to synapse | NLGN1, DLG4, BSN, RELN, PCLO | 0.0013 | 2.892 |

| Sodium ion transmembrane transport | HCN1, SLC8A1, SLC5A5, SLC9A4, SCN2A, SCN4B, KCNK1, SLC4A4, HCN3 | 0.0015 | 2.823 |

| Modulation of synaptic transmission | GRIK2, TNR, NLGN1, NLGN3, RELN, LRP8 | 0.0016 | 2.796 |

| Synaptic transmission, glutamatergic | CLCN3, CLSTN3, GRIK2, CACNB4, UNC13A, CACNA1A | 0.0019 | 2.725 |

| Synapse assembly | CLSTN3, NLGN1, BSN, NLGN3, CDH2, PCLO, CACNA1A | 0.0026 | 2.578 |

| Receptor localization to synapse | NLGN1, DLG4, RELN, DLG2 | 0.0031 | 2.508 |

| Neuron-neuron synaptic transmission | KIF1B, DLGAP2, TMOD2, CACNA1A | 0.0031 | 2.508 |

| Synaptic vesicle transport | FGFR2, SYNJ1, SNCA, NLGN1 | 0.0042 | 2.379 |

| Cellular response to nerve growth factor stimulus | MAGI2, NTRK2, CBL, RAPGEF4, ELAVL4, KIDINS220, APC | 0.0045 | 2.344 |

| Synapse organization | ANK3, TNR, SNCA, NLGN1, NFASC, NLGN3 | 0.0050 | 2.302 |

| Dendrite development | FLRT1, PAK3, MAP2, ABI2, RELN, GRIN3A | 0.0050 | 2.302 |

| Protein targeting to plasma membrane | PACS2, ANK2, ANK3, NFASC, EHD3 | 0.0061 | 2.212 |

| Ionotropic glutamate receptor signaling pathway | GRIN2C, GRIK2, CPEB4, GRIN3A, GRID1 | 0.0082 | 2.085 |

| Positive regulation of synaptic transmission, glutamatergic | TNR, NTRK2, NLGN1, NLGN3, RELN | 0.0082 | 2.085 |

| Synaptic transmission, GABAergic | CLCN3, CLSTN3, CACNB4, CACNA1A | 0.0086 | 2.066 |

| Regulation of membrane potential | HCN1, GRIN2C, GRIK2, CHRNA7, KCNJ10, CACNB4, HCN3, RIMS4, CACNA1A | 0.0099 | 2.006 |

| Positive regulation of excitatory postsynaptic potential | PRKCZ, NLGN1, DLG4, NLGN3, RELN | 0.0107 | 1.970 |

| Regulation of exocytosis | RAB3C, RAPGEF4, RAB27B, PCLO, NSF | 0.0121 | 1.916 |

| Regulation of short-term neuronal synaptic plasticity | PPFIA3, KMT2A, GRIK2, UNC13A | 0.0126 | 1.899 |

| Myelination in peripheral nervous system | NF1, LGI4, POU3F2, ADAM22 | 0.0126 | 1.899 |

| Regulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate selective glutamate receptor activity | NLGN1, DLG4, NLGN3, RELN | 0.0126 | 1.899 |

| Intracellular transport | FMN2, SPIRE1, SPIRE2, RANBP3L | 0.0302 | 1.520 |

| Synaptic vesicle exocytosis | CPLX1, TRIM9, APBA2, ADGRL1 | 0.0302 | 1.520 |

| Glial cell differentiation | PLP1, DNER, RELN, CDH2 | 0.0379 | 1.421 |

| Sensory perception of pain | NDN, OPRL1, CNR1, NIPSNAP1, DLG2, CACNA1A, KCNIP3 | 0.0393 | 1.405 |

| Oligodendrocyte differentiation | NTRK2, EXOC4, CNP, NLGN3, SOX6 | 0.0417 | 1.380 |

| Regulation of postsynaptic membrane potential | HCN1, SCN2A, SCN4B, HCN3 | 0.0421 | 1.376 |

| Vesicle-mediated transport | FMN2, FNBP1, KIF5A, MAPK8IP3, SPIRE1, MAPK8IP1, KIF16B, SPIRE2, NSF | 0.0446 | 1.351 |

| Positive regulation of endocytosis | MIB1, SNCA, CLIP3, MYH9 | 0.0465 | 1.332 |

| Ion transport | CLCN3, PANX2, CHRNA7, PLLP, ADD2 | 0.0482 | 1.317 |

In contrast, upregulated MTH CI vs CTRL genes are assigned to processes such as endoplasmic reticulum calcium ion homeostasis, cytokine-mediated signaling, protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum and protein c-terminus binding pathways. Whereas downregulated MTH CI vs CTRL transcripts are enriched in cellular response to TNF and NGF, regulation of vasoconstriction, ion transmembrane transport, regulation of membrane potential, sensory perception of pain, glutamatergic synaptic transmission, response to estradiol, calcium ion transport, response to drug, regulation of blood pressure, negative regulation of BMB signaling pathway, calcium and potassium channel activity, postsynaptic and plasma membrane, neural cell body, cholinergic synapse, cAMP and cGMP-PKG signaling pathway and inflammatory mediator of regulation of TRP channels (Suppl. Figures 3A–D). As for the previous figures, we grouped the most upregulated and downregulated MTH CI vs CTRL genes obtained from GO biological processes into 5 categories. As shown in Suppl. Figs. 3E–I, the highest expressed upregulated gene are Il22ra1, Csf3r, Il1rap, Ptpm, Il17re and Socs5 involved in immune response (Suppl. Fig. 3E) and Pml, Psen2, Grina and Camk2d associated with ion transport (Suppl. Fig. 3G). Interestingly, the list of the downregulated MTH CI vs CTRL genes include transcripts such as Calca, Trpa1, Ntrk1, Trpv1 related to inflammatory pathways (Suppl. Fig. 3F), Tripm8, Grik1, Chrnb4, Chrna3, Pln involved in ion homeostasis (Suppl. Fig. 3G), Dbh, P2rx1, Slc6a4 and Nrpr1 responsible for the regulation of vasoconstriction (Suppl. Fig. 3H) and Cyp2e1, Sfrp2, Htrb1 and Bche associated with sensory perception of pain (Suppl. Fig. 3I).

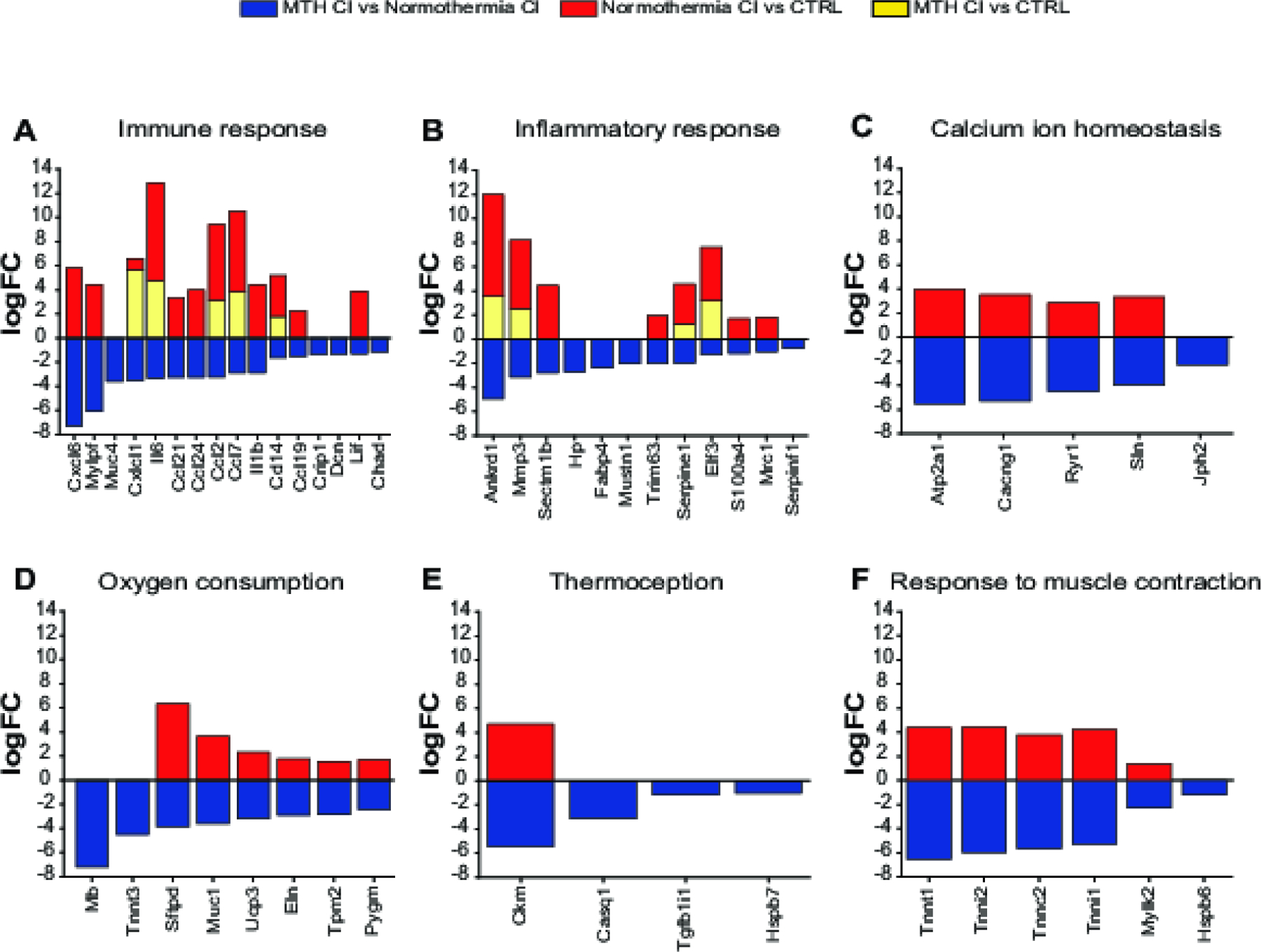

Next, we compared the expression level of down-regulated MTH CI vs Normothermia CI genes enriched in biological processes listed in Fig. 5A between the three experimental conditions. As shown in Figure 6A–F the majority of down-regulated MTH CI vs Normothermia CI genes are up-regulated in Normothermia CI vs CTRL cochleae. In contrast the only genes found up-regulated in MTH vs CTRL are the immune response-associated genes Cxcl1, Il6, Ccl2, Ccl7 and Cd14 and the inflammatory response-related transcripts Ankdr1, Mmp3, Serpine1 and Elf3 (Fig. 6A and 6B). The remaining genes are either not detected by RNA-seq analysis or are not significant differentially expressed in both Normothermia CI vs CTRL and MTH vs CTRL cochleae.

Figure 6.

Gene expression comparison between the three experimental groups: MTH CI vs Normothermia CI, Normothermia CI vs CTRL and MTH CI vs CTRL. A-F) Expression level of MTH CI vs Normothermia CI Immune response (A), Inflammatory response (B), Calcium homeostasis (C), Oxygen consumption (D), Thermoception (E) and Response to muscle contraction (F) genes listed in GO biological processes were compared with those expressed in Normothermia CI vs CTRL and MTH CI vs CTRL experimental conditions. Differentially expressed genes are expressed as logFC (FDR adj_pvalue <0.5).

The protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis of the unique GO enriched MTH CI vs Normothermia CI genes was constructed using STRING 11.0 software (Figure 7). The PPI network using 52 genes as query formed a dense network with 195 interactions and 5 clusters. As shown in Figure 7, the members of cluster 1 (regulation of muscle function), cluster 2 (ATPase activity), cluster 4 (response to muscle contraction) and cluster 5 (oxygen consumption) and are highly interconnected within and between the clusters. Interestingly members of the cluster 3, associated with immune and inflammatory responses, show a higher number of protein-protein interaction within the same cluster than between the others. In particular, we found that cytokines Il-6, Cxcl6, Cxcl1, Il1b, Ccl2, Ccl7, Ccl19, Ccl21, Ccl24, as well as Decorin protein (Dcn) and metalloproteinase 3 (Mmp3) are involved in more interactions than the other proteins of the cluster 3. The variety and the elevated number of functional associations represented in Fig.7 suggest that the hearing protection given by therapeutic hypothermia against damage caused by cochlear implantation might be the result of an interplay between numerous molecular pathways.

Figure 7.

String protein-protein interaction network of the 52 GO enrichment MTH CI vs Normothermia CI downregulated genes. Differentially expressed genes are separated into 5 K-means clusters related to regulation of muscle function (cluster 1), ATPase activity (cluster 2), immune and inflammatory response (cluster 3), muscle contraction (cluster 4) oxygen consumption (cluster 5). The solid and the dashed lines indicate interaction within the same and between clusters respectively. Different color indicates different type of connections. Cyan: from curated database; Pink: experimentally determined; Green: gene neighborhood; Red: gene fusions; Blue: gene co-occurrence; Yellow: textmining; Black: co-expression; Light-Blue: protein homology

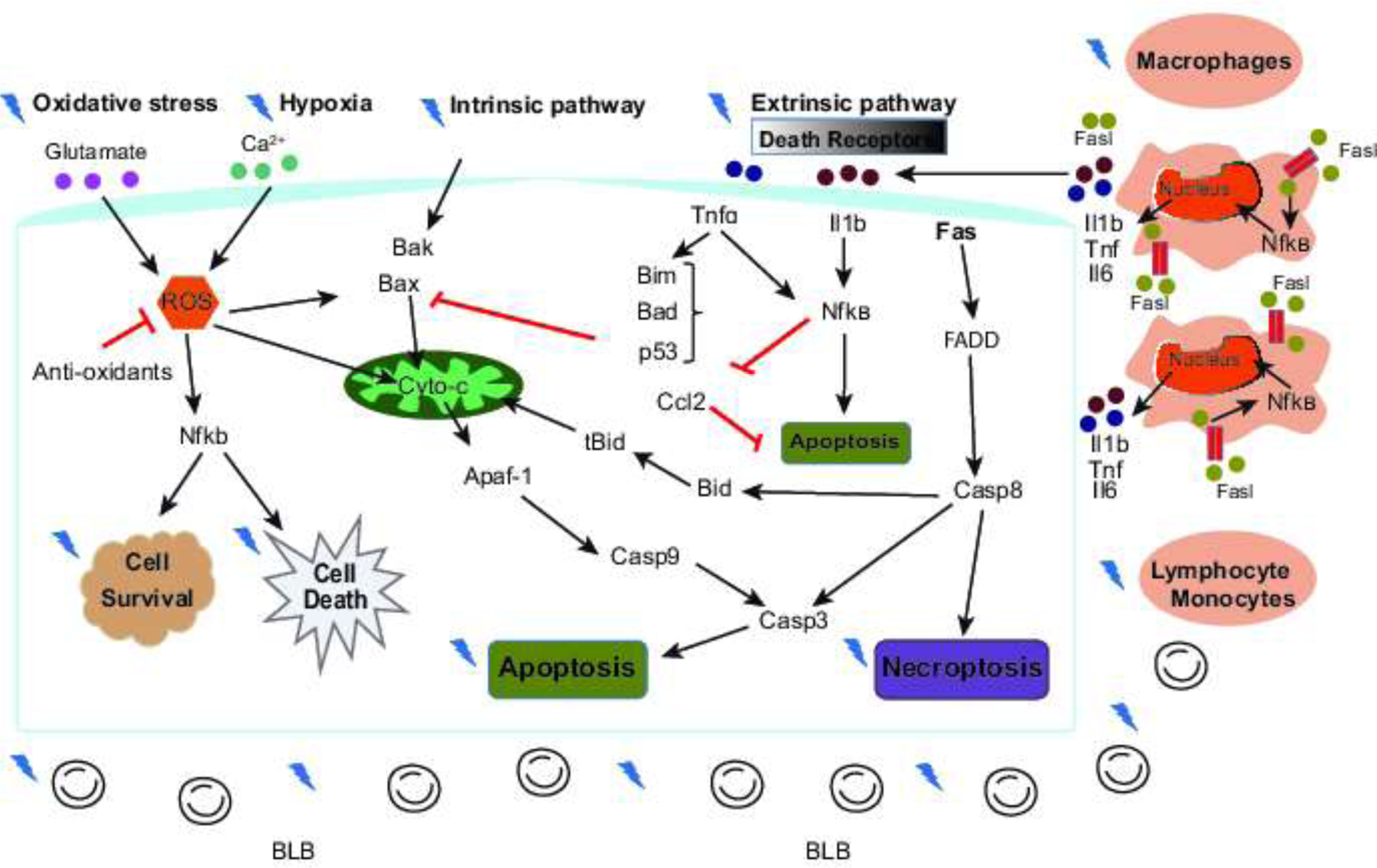

3.9. Mechanisms of MTH-mediated protection against cochlear implant-induced trauma

Figure 8 shows a predicted working model of molecular pathways affected by MTH when applied to prevent cell death and consequently hearing impairment induced by electrode insertion. Hearing protection afforded by the MTH therapy underlies its effects on the immune response, ameliorating of inflammation, reducing of the oxidative stress, prevention of BLB breakdown and inhibition of intrinsic and extrinsic cell death pathways. After a serious insult such as cochlear implantation surgery, the inner ear cells can trigger apoptosis and necrosis due to changes in calcium homeostasis and consequently release reactive oxygen species (ROS) into the cytoplasm (Eshraghi 2006). ROS can lead to modulation of tumor necrosis factor (TNFα) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Bas et al. 2015). Inflammatory cytokines such as Ccl2 and Ccl7 attract macrophages and myocytes to the sites of the trauma (Bas et al. 2015). Our results show that MTH locally applied during electrode implantation decreases the production of inflammatory chemokines which lead to downregulating the migration of immune cells. Moreover, MTH modulates the affinity of the death ligands-receptors inhibiting the recruitment of the initiator caspases like NF-kB or Casp-8 molecules. MTH can also decrease the level of ROS limiting the release of proapoptotic molecules like cytochrome c into the cytosol.

Figure 8.

Mechanisms of protection afforded by mild therapeutic hypothermia (MTH). Mild therapeutic hypothermia appears to modulate a variety of processes thought to be important in mediating inner ear damage after cochlear implantation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Hypothermia preserves residual hearing against cochlear implantation trauma

In the last decades, the surgical approaches, the route of electrode array insertion (round window approach or traditional cochleostomy), the electrode length and the insertion depth (Kiefer et al. 2004; Adunka et al. 2004; Roland 2005; Gantz et al. 2005; Roland, Wright, and Isaacson 2007; Adunka et al. 2007; Gstoettner et al. 2009; Büchner et al. 2009; Arnoldner et al. 2010; Gifford et al. 2013) have been taken in consideration to avoid acoustic, vibration and mechanical damage caused by cochlear implantation to the cochlear and vestibular structures. With more knowledge of the molecular mechanisms of electrode insertion-derived hearing impairment, pharmacological approaches were combined with the improvements in electrode designs and surgical techniques aimed at preserving the integrity of the cochlear structures. In a separate set of studies, it has been shown that locally application of the antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) and the glucocorticosteroid, Dexamethasone, preserve residual hearing decreasing the oxidative stress and modulating inflammatory response in a guinea pig model of electrode implantation trauma (Eastwood et al. 2010; James et al. 2008; Vivero et al. 2008; Van De Water, Abi Hachem, et al. 2010).

Considerable research and clinical studies have provided evidence in support of the efficacy, safety and feasibility of hypothermia in a variety of injuries (Drescher 1976; Marion et al. 1997; Maier et al. 1998; Bernard et al. 2002; Dietrich, Atkins, and Bramlett 2009) including CI-induced hearing loss (Balkany et al. 2005; Eshraghi et al. 2005; Tamames et al. 2016). Cooling helmet, blanket or pad are some of the physical methods adopted to achieve local and general hypothermia and found to be beneficial for head and spinal cord injury (Kammersgaard et al. 2000; Hachimi-Idrissi et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2004). In an animal study of CI-induced hearing loss, we have successfully protected residual hearing up to a month post-EIT using a customized probe device designed to locally cool the cochlea between 4–6 °C (Tamames et al. 2016). Moreover, our research group has also demonstrated the feasibility of locally application of MTH in clinical practice with the use of computational model and adult human cadaver temporal bones (Tamames et al. 2017; Perez et al. 2019). In the present study, we evaluated the beneficial effects and safety of localized MTH delivered to the inner ear during cochlear implant surgery over a period of 3 months. The results presented show that the protective effect of MTH persist for months post-surgery. Although the hearing thresholds of MTH CI animals were elevated immediately following CI surgery, a recovery was observed from week 1. Contrary the ABR of Normothermic-implanted group remained elevated over the next 3 months (Fig. 1). Moreover, we reported here for the first time that MTH is not detrimental for the residual hearing. ABR of the animals treated with MTH alone were comparable to those of unoperated animals for the entire period of the study (Fig. 2).

4.2. Mechanisms of MTH protection in a model of cochlear implantation

Electrode implantation-induced hearing loss can lead to oxidative stress and inflammation (Eshraghi and Van de Water 2006; Eshraghi 2006; Bas, Gupta, and Van De Water 2012). In the present study we investigated the protective mechanisms of MTH against cochlear implant-induced trauma using RNA sequencing gene expression analysis. Our results suggest that MTH decreases interleukin and pro-inflammatory cytokines release, reduces microglia activation and chemotaxis, modulates the blood labyrinth barrier (BLB) integrity, reduces calcium influx, reactive oxygens species and oxygen consumption which all lead to the loss of cochlear sensorineural cells via apoptosis and necrosis cell death.

Proinflammatory cytokines (IL1β, TNFα are IL-6) and chemokines (C-C- and CXC) are the first genes to be upregulated in response to a variety of insults (Eshraghi and Van de Water 2006; Fujioka et al. 2006; Truettner, Suzuki, and Dietrich 2005; Truettner, Bramlett, and Dietrich 2017; Dugan et al. 2020). The signaling downstream from inflammatory cytokines includes activation of resident microglia and infiltration of immune cells that may have reparative or detrimental effects at the site of the inflammation (Satoh et al. 2003; Mahata et al. 2014; Bas et al. 2015; Metcalfe 2019; Fei et al. 2017; Ma et al. 2018). In the present study we show for the first time that MTH modulates inflammatory and immune response processes such as Tnfα, Nfkβ and interleukin-1 signaling pathways and immune cells migration decreasing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines Il1b, Il6, Cxcl1, Cxcl6, Ccl7, Ccl19, Ccl21, Ccl24, genes involved in cytokine/chemokines mediated signaling pathway (Chad), and the genes associated with macrophages recruitment/differentiation (Ccl2, Mrc1, S100a4 and Serpnf1, Cd14, Lif, Crip1) in MTH CI vs Normothermia CI experimental group (Fig.5 and Fig.6). Our findings are consistent with recent works showing that MTH is beneficial in reducing cytotoxic secondary inflammatory mechanisms in brain injury models (Truettner, Bramlett, and Dietrich 2017; Dugan et al. 2020). Although hypothermia regulates inflammation, an increase of Il6 expression level was reported 3 and 6 hrs post-MTH treatment in models of TBI (traumatic brain injury) (Truettner, Suzuki, and Dietrich 2005) and TNFα stimulation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells, respectively (Diestel et al. 2008).

Our RNA-seq analysis are based on the effect of mild cooling delivered for a limited period of 60 minutes during cochlear implantation trauma (see section 2.2.2 of material and methods). This suggests that the protective effect of MTH may be limited by the duration of the treatment application. As previously published by other groups (Eshraghi and Van de Water 2006) in our model of inner ear trauma, electrode implantation indeed increases the expression levels of proinflammatory-related processes and genes (Il1a, Il1b, IL6, Il24, Il2rg, Il22ra2, Cxcl1, Ccl2, Ccl7, Cd14) (Suppl. Fig.2, Table 1 and Fig. 6). Interestingly, some of these genes (Cxcl1, Il6, Ccl2, Ccl7 and Cd14) were found to be upregulated as well in MTH CI vs CTRL group. However, transcriptome analysis of MTH CI vs CTRL also showed a different gene expression pattern compared to the other 2 experimental conditions with MTH downregulating inflammatory- associated Trpa1, Ntkr1, Trpv1 Greem1, Adamts12, Ass1, Cav1 and Tob1 genes (Suppl. Fig.3 and Fig. 6). This may be due to activation of intracellular mechanisms that are independent of cochlear implantation trauma.

Hypothermia protects the structure and the function of the blood brain barrier (BBB) from traumatic brain injury by attenuating the loss of proteins constituting the BBB (Dietrich et al. 1990; Chatzipanteli et al. 2000; Smith and Hall 1996; Baumann et al. 2009) and reducing matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (Truettner, Alonso, and Dietrich 2005; Nagel et al. 2008; Dugan et al. 2020; Lee et al. 2005) involved in inflammation (Winkler and Fowlkes 2002; Noble et al. 2002), wound healing tissue remodeling (Salo et al. 1994), dysregulation of cerebral blood flow (Rosenberg, Estrada, and Dencoff 1998; Gasche et al. 1999; Gasche et al. 2001) and response to drugs (Tziakas et al. 2004; Wu et al. 2007; Yamamoto and Takai 2009). Our results show that MTH modulates biological processes and pathways associated with BLB permeability and wound healing downregulating Ankrd1 and Mustn1 genes, the metalloproteinase inducer gene Decorin (Dcn) and the enzymes responsible for extracellular matrix remodeling (Mmp3 and Serpine 1). Interestingly, the expression level of the genes (Tnnt1, Tnni2, Tnnc2, Tnni1, Mylk2 and Hspb6) associated with response to muscle contraction was decreased as well by MTH. Aside from direct protection of BLB integrity, mild hypothermia affected the expression of Trim63, Serpnf1, Fabp4, Muc4 and HP genes responsible for response to glucocorticosteroids (Fig. 5 and Fig 6). Contrary, Ankrd1, Mmp3, Serpin1 were upregulated in both Normothermia CI vs CTRL and MTH CI vs CTRL, while Tnnt1, Tnni2, Tnnc2, Tnni1, Mylk2 were overexpressed in Normothermia CI vs CTRL group only. DCN, Mustn1, Serpnf1, Fab4 and Hp genes were not expressed in either experimental condition (Fig.6). Moreover, implantation surgery induced overexpression of extracellular matrix remodeling Plau, Mmp12, Col3a1 genes, the transcription factor Plet1, the integrin ITga5, the disintegrin Adam17 and several vasoconstriction-related genes (Suppl. Fig. 2 and Table 1), while markers for glial differentiation, cell growth and myelination that occur after an initial inflammatory phase of wound healing were downregulated (Suppl. Fig. 2 and Table 2). Our results are in line with previous works showing that the disruption of cochlear blood-labyrinth-barrier (BLB- analog to the blood brain barrier BBB), the disturbance on cochlear blood flow and the tissue remodeling occur early during noise and cochlear-implant-induced hearing loss (Hawkins 1971; Bas et al. 2015; Wu et al. 2017). Interestingly in MTH CI vs CTRL group, a different set of genes related to BLB integrity (Calca and Npnt), vascular constriction (Dbn, P2rx1, Slc6a4, Npy1r, Sult1a1, Atp1a2) and response to drugs (Cyp2e1, Stfp2, Hrt1b, Bche, Acacb, Map2k6, Thra) were found to be downregulated (Suppl. Fig. 3). These results suggest that the adaptive stress response in physiological conditions operate at different cellular level.

MTH, in the present study, significantly modulated biological mechanisms and the expression level of genes associated with calcium ion homeostasis and oxidative stress in our model of CI-trauma (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6 and Suppl. Fig. 3). ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 1 (Atp2a1), calcium voltage-gated channel auxiliary subunit gamma 1 (Cacng1), ryanodine receptor 1 (Ryr1), sarcolipin (Sln) and junctophilin 2 (Jph2) transcripts were downregulated by mild cooling as well as the oxidative stress related genes Mb, Tnnt3, Sftpd, Muc1, Ucp3, Eln, Tpm2, Pygm and Tpm1 (Fig. 5). A neuroprotective effect of mild hypothermia on calcium influx and ROS generation following TBI has been previously reported by Dietrich et al., 1996 (Dietrich et al. 1996). Increase of intracellular calcium overload and oxidative stress, as consequences of a secondary injury cascade, compromises the physiological function of mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum, the neural ion homeostasis and circuit formation, the synaptic transmission and the vesicle endo- exocytosis process (Suppl. Fig. 2 and Table 1; (Lifshitz et al. 2003; Smith et al. 1999; Wolf et al. 2001; Staal et al. 2007; Staal et al. 2010; Barkhoudarian, Hovda, and Giza 2011). Implantation induced overexpression of genes associated with free radicals’ production (Mb, Muc1, Ryr1, Ucp2, Plau, Hp, Pygm, Tf, Cryab, Pdl1m1, Nol3, Cyba, Cldn3, Adam17, Adsl) and ion homeostasis (Cav3, Sln and Adora2a) (Suppl. Fig. 2, Table 1 and Fig. 6). Genes involved in the positive regulation of neuronal development and plasticity and neuronal excitability were significantly downregulated in Normothermia CI vs CTRL (Suppl. Fig. 2 and Table 2). MTH does not impact neuroplasticity, however, possibly because this ability depends on the depth and duration of the treatment.

Temperature is an important variable in several insults including brain and spinal cord injuries, noise and cochlear implantation-induced hearing impairment (Drescher 1976; Brown, Smith, and Nuttall 1983; Dietrich et al. 1990; Eshraghi et al. 2005; Ozgünen et al. 2010; Tamames et al. 2016). In various model of TBI, induced mild hyperthermia significantly aggravates the physiological outcomes (Ozgünen et al. 2010; Nybo, Secher, and Nielsen 2002; Kilpatrick et al. 2000). Contrary, heat stress seems to be protective against acoustic injury in mice (Yoshida, Kristiansen, and Liberman 1999). However, little is known regarding the effect of heat stress on cell. In our model of EIT, mild therapeutic hypothermia modulates the response to heat shock by decreasing the expression level of the genes Ckm, Casq1, Tgfb1i1 and Hspb7 in MTH CI vs Normothermia CI group (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6). Our results are consistent with previous studies showing that mild hypothermia reduces the expression level of the heat proteins post trauma (Vishwakarma et al. 2017). Interestingly, in Normothermia CI vs CTRL, Ckm was the only gene resulted to be upregulated (Fig.6 and Suppl. Fig. 2 and Table 1). The outcomes of MTH on heat shock observed in our study may be a response to a systemic effect caused by changes in normal body temperature during and post-surgery rather than to a local mechanical trauma induced by EI.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we report that MTH is effective and safe in our model of cochlear implantation trauma. Whole cochlea transcriptome analysis performed 24 hrs post CI provided novel data on multiple mechanisms targeted by mild cooling. As shown in the string network analysis (Fig.7) and in the hypothermia working model (Fig.8), MTH modulates several secondary injury pathways including cytokine/chemokines inflammatory and immune responses, blood labyrinth barrier breakdown, neurotransmitter release, excitoxicity, intracellular calcium flux and oxidative stress. However, we did not perform qRT-PCR and/or quantification of proteins level to validate the RNA sequencing results. Additional experiments will be necessary to determine the best strategy to induce therapeutic hypothermia, the optimal duration of cooling and to clarify the mechanisms at different time points. Distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAE) and single cell RNAseq will highlight the role of specific cochlear region sensorineural cells in the protective effect afforded by MTH against CI-induced hearing loss. Understanding the molecular pathways underlying MTH cryoprotection can contribute to the development of new combinatorial therapeutic strategies aimed at preserving residual hearing in variety of cochlear insults.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. RNA-seq gene expression of top 50 downregulated and the upregulated genes in Normothermia CI vs CTRL (Suppl. Fig 1A) and in MTH CI vs CTRL (Suppl. Fig 1B).

Supplementary Figure 2. Gene ontology analysis of downregulated and upregulated genes from Normothermia CI vs CTRL. A-D) GO biological processes (A), GO molecular functions (B), GO cellular components (C), KEEG pathways (D) of Normothermia CI vs CTRL downregulated and upregulated genes, represented as log10(p-value). E-I) Top differentially expressed Normothermia CI vs CTRL genes listed in GO biological processes and related to E) Immune response, F) Inflammatory response, G) Myelination, H) Synaptic transmission and I) Neural circuit formation. Differentially expressed genes (FDR adj_pvalue<0.5) were analyzed using DAVID informatics program considering p<0.05 as statistically cutoffs limit.

Supplementary Figure 3. Gene ontology analysis of upregulated and downregulated genes from MTH CI vs CTRL. A-D) GO biological processes (A), GO molecular functions (B), cellular components (C), KEEG pathway (D) of MTH CI vs CTRL downregulated and upregulated genes, represented as log10(p-value). E-I) Fold change of the top differentially expressed Hypothermia CI vs CTRL genes listed in GO biological processes and related to Immune response (E), Inflammatory response (F), Ion homeostasis (G), Vasoconstriction (H), Response to drugs (I). Differentially expressed genes (FDR adj_pvalue<0.5) were analyzed using DAVID informatics program considering p<0.05 as statistically cutoffs limit.

Highlights.

Localized mild therapeutic hypothermia is effective and safe in preserving residual hearing against cochlear implant (CI)-induced damage.

CI electrode insertion causes inflammatory and proapoptotic processes and consequently the loss of sensorineural inner ear structure.

Mild therapeutic hypothermia modulates secondary injury mechanisms in a rat model of CI trauma.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH NIDCD 5R01DC019158, 1R44DC019586, 1R01DC013798, and a pilot award from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002736, Miami Clinical and Translational Science Institute.

The authors thank the Microarray and Genomics Core, Cancer Center, at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus for providing us with the RNA sequencing library and Dr. Antony Griswold, Department of Human Genetics at the University of Miami for all the suggestions to improve the quality of the data reported in this study.

Financial conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial conflict of interest. The research presented here, or efforts of any personnel were not supported by RestorEar Devices LLC or other commercial entities.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

S.M.R. and C.K. are named inventors on intellectual property related to the design of hypothermia system and probe discussed here. They are also co-founders of RestorEar Devices LLC.

References

- Adunka OF, Radeloff A, Gstoettner WK, Pillsbury HC, and Buchman CA. 2007. ‘Scala tympani cochleostomy II: topography and histology’, Laryngoscope, 117: 2195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adunka O, Kiefer J, Unkelbach MH, Radeloff A, Lehnert T, and Gstöttner W. 2004. ‘[Evaluation of an electrode design for the combined electric-acoustic stimulation]’, Laryngorhinootologie, 83: 653–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnoldner C, Helbig S, Wagenblast J, Baumgartner WD, Hamzavi JS, Riss D, and Gstoettner W. 2010. ‘Electric acoustic stimulation in patients with postlingual severe high-frequency hearing loss: clinical experience’, Adv Otorhinolaryngol, 67: 116–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkany TJ, Eshraghi AA, Jiao H, Polak M, Mou C, Dietrich DW, and Van De Water TR. 2005. ‘Mild hypothermia protects auditory function during cochlear implant surgery’, Laryngoscope, 115: 1543–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkhoudarian G, Hovda DA, and Giza CC. 2011. ‘The molecular pathophysiology of concussive brain injury’, Clin Sports Med, 30: 33–48, vii-iii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bas E, Goncalves S, Adams M, Dinh CT, Bas JM, Van De Water TR, and Eshraghi AA. 2015. ‘Spiral ganglion cells and macrophages initiate neuro-inflammation and scarring following cochlear implantation’, Front Cell Neurosci, 9: 303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bas E, Gupta C, and Van De Water TR. 2012. ‘A novel organ of corti explant model for the study of cochlear implantation trauma’, Anat Rec (Hoboken), 295: 1944–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann E, Preston E, Slinn J, and Stanimirovic D. 2009. ‘Post-ischemic hypothermia attenuates loss of the vascular basement membrane proteins, agrin and SPARC, and the blood-brain barrier disruption after global cerebral ischemia’, Brain Res, 1269: 185–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, Jones BM, Silvester W, Gutteridge G, and Smith K. 2002. ‘Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia’, N Engl J Med, 346: 557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MC, Smith DI, and Nuttall AL. 1983. ‘The temperature dependency of neural and hair cell responses evoked by high frequencies’, J Acoust Soc Am, 73: 1662–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büchner A, Schüssler M, Battmer RD, Stöver T, Lesinski-Schiedat A, and Lenarz T. 2009. ‘Impact of low-frequency hearing’, Audiol Neurootol, 14 Suppl 1: 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccino A, Bisson LJ, Carpenter B, Marzo J, Dietrich WD 3rd, and Cappuccino H. 2010. ‘The use of systemic hypothermia for the treatment of an acute cervical spinal cord injury in a professional football player’, Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 35: E57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatzipanteli K, Alonso OF, Kraydieh S, and Dietrich WD. 2000. ‘Importance of posttraumatic hypothermia and hyperthermia on the inflammatory response after fluid percussion brain injury: biochemical and immunocytochemical studies’, J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 20: 531–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciorba A, Gasparini P, Chicca M, Pinamonti S, and Martini A. 2010. ‘Reactive oxygen species in human inner ear perilymph’, Acta Otolaryngol, 130: 240–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbourne F, Grooms SY, Zukin RS, Buchan AM, and Bennett MV. 2003. ‘Hypothermia rescues hippocampal CA1 neurons and attenuates down-regulation of the AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit after forebrain ischemia’, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 100: 2906–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozma RS, Dima-Cozma LC, Rădulescu LM, Hera MC, Mârţu C, Olariu R, Cobzeanu BM, Bitere OR, and Cobzeanu MD. 2018. ‘Vestibular sensory functional status of cochlear implanted ears versus non-implanted ears in bilateral profound deaf adults’, Rom J Morphol Embryol, 59: 105–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhondt C, Maes L, Vanaudenaerde S, Martens S, Rombaut L, Van Hecke R, Valette R, Swinnen F, and Dhooge I. 2022. ‘Changes in Vestibular Function Following Pediatric Cochlear Implantation: a Prospective Study’, Ear Hear, 43: 620–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diegelmann RF, and Evans MC. 2004. ‘Wound healing: an overview of acute, fibrotic and delayed healing’, Front Biosci, 9: 283–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diestel A, Roessler J, Berger F, and Schmitt KR. 2008. ‘Hypothermia downregulates inflammation but enhances IL-6 secretion by stimulated endothelial cells’, Cryobiology, 57: 216–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich WD, Atkins CM, and Bramlett HM. 2009. ‘Protection in animal models of brain and spinal cord injury with mild to moderate hypothermia’, J Neurotrauma, 26: 301–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich WD, and Bramlett HM. 2010. ‘The evidence for hypothermia as a neuroprotectant in traumatic brain injury’, Neurotherapeutics, 7: 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich WD, Busto R, Globus MY, and Ginsberg MD. 1996. ‘Brain damage and temperature: cellular and molecular mechanisms’, Adv Neurol, 71: 177–94; discussion 94–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich WD, Busto R, Halley M, and Valdes I. 1990. ‘The importance of brain temperature in alterations of the blood-brain barrier following cerebral ischemia’, J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 49: 486–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich WD, Levi AD, Wang M, and Green BA. 2011. ‘Hypothermic treatment for acute spinal cord injury’, Neurotherapeutics, 8: 229–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh C, Hoang K, Haake S, Chen S, Angeli S, Nong E, Eshraghi AA, Balkany TJ, and Van De Water TR. 2008. ‘Biopolymer-released dexamethasone prevents tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced loss of auditory hair cells in vitro: implications toward the development of a drug-eluting cochlear implant electrode array’, Otol Neurotol, 29: 1012–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman MF, Gifford RH, Spahr AJ, and McKarns SA. 2008. ‘The benefits of combining acoustic and electric stimulation for the recognition of speech, voice and melodies’, Audiol Neurootol, 13: 105–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman MF, Gifford R, Lewis K, McKarns S, Ratigan J, Spahr A, Shallop JK, Driscoll CL, Luetje C, Thedinger BS, Beatty CW, Syms M, Novak M, Barrs D, Cowdrey L, Black J, and Loiselle L. 2009. ‘Word recognition following implantation of conventional and 10-mm hybrid electrodes’, Audiol Neurootol, 14: 181–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher DG 1976. ‘Effect of temperature on cochlear responses during and after exposure to noise’, J Acoust Soc Am, 59: 401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan EA, Bennett C, Tamames I, Dietrich WD, King CS, Prasad A, and Rajguru SM. 2020. ‘Therapeutic hypothermia reduces cortical inflammation associated with utah array implants’, J Neural Eng, 17: 026035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn CC, Perreau A, Gantz B, and Tyler RS. 2010. ‘Benefits of localization and speech perception with multiple noise sources in listeners with a short-electrode cochlear implant’, J Am Acad Audiol, 21: 44–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood H, Pinder D, James D, Chang A, Galloway S, Richardson R, and O’Leary S. 2010. ‘Permanent and transient effects of locally delivered n-acetyl cysteine in a guinea pig model of cochlear implantation’, Hear Res, 259: 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enticott Joanne C., Tari Sylvia, Koh Su May, Dowell Richard C., and O’Leary Stephen J.. 2006. ‘Cochlear Implant and Vestibular Function’, 27: 824–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshraghi AA 2006. ‘Prevention of cochlear implant electrode damage’, Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 14: 323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshraghi AA, Gupta C, Van De Water TR, Bohorquez JE, Garnham C, Bas E, and Talamo VM. 2013. ‘Molecular mechanisms involved in cochlear implantation trauma and the protection of hearing and auditory sensory cells by inhibition of c-Jun-N-terminal kinase signaling’, Laryngoscope, 123 Suppl 1: S1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshraghi AA, Hoosien G, Ramsay S, Dinh CT, Bas E, Balkany TJ, and Van De Water TR. 2010. ‘Inhibition of the JNK signal cascade conserves hearing against electrode insertion trauma-induced loss’, Cochlear Implants Int, 11 Suppl 1: 104–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshraghi AA, Nehme O, Polak M, He J, Alonso OF, Dietrich WD, Balkany TJ, and Van De Water TR. 2005. ‘Cochlear temperature correlates with both temporalis muscle and rectal temperatures. Application for testing the otoprotective effect of hypothermia’, Acta Otolaryngol, 125: 922–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshraghi AA, and Van de Water TR. 2006. ‘Cochlear implantation trauma and noise-induced hearing loss: Apoptosis and therapeutic strategies’, Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol, 288: 473–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshraghi AA, Yang NW, and Balkany TJ. 2003. ‘Comparative study of cochlear damage with three perimodiolar electrode designs’, Laryngoscope, 113: 415–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA. 2015. “FDA executive summary: premarket to postmarket shifts in clinical data requirements for cochlear implant device approvals in pediatric patients. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/MedicalDevices/MedicalDevicesAdvisoryCommittee/EarNoseandThroatDevicesPanel/UCM443996.pdf. .” In. Ear, Nose, and Throat Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee.

- Fei F, Qu J, Li C, Wang X, Li Y, and Zhang S. 2017. ‘Role of metastasis-induced protein S100A4 in human non-tumor pathophysiologies’, Cell Biosci, 7: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Renz D, Wiesnet M, Schaper W, and Karliczek GF. 1999. ‘Hypothermia abolishes hypoxia-induced hyperpermeability in brain microvessel endothelial cells’, Brain Res Mol Brain Res, 74: 135–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka M, Kanzaki S, Okano HJ, Masuda M, Ogawa K, and Okano H. 2006. ‘Proinflammatory cytokines expression in noise-induced damaged cochlea’, J Neurosci Res, 83: 575–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantz BJ, Hansen MR, Turner CW, Oleson JJ, Reiss LA, and Parkinson AJ. 2009. ‘Hybrid 10 clinical trial: preliminary results’, Audiol Neurootol, 14 Suppl 1: 32–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantz BJ, Turner C, Gfeller KE, and Lowder MW. 2005. ‘Preservation of hearing in cochlear implant surgery: advantages of combined electrical and acoustical speech processing’, Laryngoscope, 115: 796–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasche Y, Copin JC, Sugawara T, Fujimura M, and Chan PH. 2001. ‘Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition prevents oxidative stress-associated blood-brain barrier disruption after transient focal cerebral ischemia’, J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 21: 1393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]