Abstract

The stria vascularis (SV) has been shown to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of many diseases associated with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL), including age-related hearing loss (ARHL), noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL), hereditary hearing loss (HHL), and drug-induced hearing loss (DIHL), among others. There are a number of other disorders of hearing loss that may be relatively neglected due to being underrecognized, poorly understood, lacking robust diagnostic criteria or effective treatments. A few examples of these diseases include autoimmune inner ear disease (AIED) and/or autoinflammatory inner ear disease (AID), Meniere’s disease (MD), sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL), and cytomegalovirus (CMV)-related hearing loss (CRHL). Although these diseases may often differ in etiology, there have been recent studies that support the involvement of the SV in the pathogenesis of many of these disorders. We strive to highlight a few prominent examples of these frequently neglected otologic diseases and illustrate the relevance of understanding SV composition, structure and function with regards to these disease processes. In this study, we review the physiology of the SV, lay out the importance of these neglected otologic diseases, highlight the current literature regarding the role of the SV in these disorders, and discuss the current strategies, both approved and investigational, for management of these disorders.

Keywords: stria vascularis, autoimmune inner ear disease (AIED), autoinflammatory inner ear disease (AID), Meniere’s disease (MD), sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL), cytomegalovirus-related hearing loss (CRHL)

Introduction

The stria vascularis (SV) has been shown to play a critical role in hearing. Dysfunction of the SV has also been well established in the pathogenesis of many common causes of sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL), including age-related hearing loss (ARHL), noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL), hereditary hearing loss (HHL), and drug-induced hearing loss (DIHL), among others. Although directed targeted therapies for these conditions continue to emerge, there has been a growing body of literature on the role of the SV in many other causes of SNHL that may be considered neglected otologic diseases. While not an exhaustive list, we strive to highlight a few prominent examples of these frequently neglected otologic diseases and illustrate the relevance of understanding SV composition, structure, and function with regards to these disease processes.

For the purposes of this review, neglected otologic diseases include disorders where at least one of the following is true: (a) diagnosis is underrecognized due to lack of robust diagnostic criteria, (b) diseases where the ability to implement effective diagnostic measures remains challenging, (c) underlying disease pathophysiology remains largely undefined, or (d) diseases where few effective treatments exist. A few examples of these diseases include autoimmune inner ear disease (AIED) and/or autoinflammatory inner ear disease (AID), Meniere’s disease (MD), sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL), and cytomegalovirus (CMV)-related hearing loss (CRHL). Although these diseases may often differ in etiology, there have been recent studies that support the involvement of the SV in the pathogenesis of many of these disorders. Advances in both our understanding of the cellular physiology of the SV and its role in hearing dysfunction may contribute eventually to an improved recognition and treatment of many of these neglected otologic diseases. In this review, we discuss the physiology of the SV, emphasize the importance of these neglected otologic diseases, highlight the current literature regarding the role of the SV in these disorders, and discuss the current strategies, both approved and investigational, for management of these disorders.

I. Cellular Composition and Function of the Stria Vascularis

2.1. Overview of the Stria Vascularis

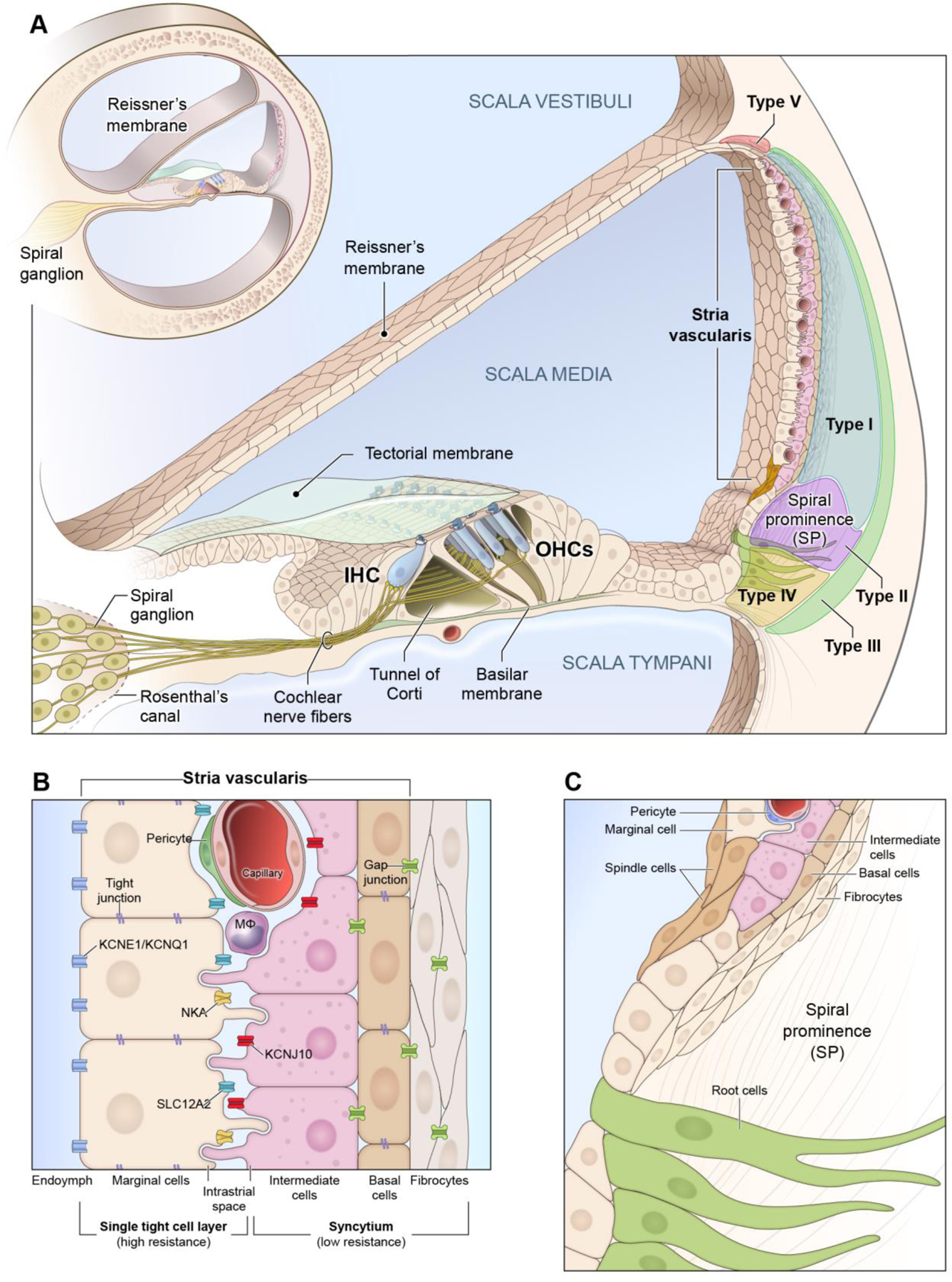

The SV is a highly vascularized tissue that lines the medial aspect of the lateral wall of the cochlea (Figure 1A) and is comprised of three major cell types, including marginal, intermediate, and basal cells, as well as rarer cell types, including spindle cells, pericytes, and endothelial cells (Figure 1B and 1C). Marginal cells are connected by tight junctions and form the most medial layer of the SV, which faces the endolymph of the cochlea and are responsible for the active transport of potassium as well as other substances into the endolymph (Hibino et al., 2010; Kim and Ricci, 2022; Wangemann, 1995; Zdebik et al., 2009). Intermediate cells facilitate potassium concentration and transport of molecules through the SV (Chen, J. and Zhao, H.B., 2014; Steel and Barkway, 1989), and the basal cells are closely associated with the fibrocytes of the spiral ligament that assist in recycling potassium and other molecules from the perilymph. Both cell types are connected by gap junctions. Despite this work, the role that these cell types play in endocochlear potential (EP) generation and cochlear ionic homeostasis remains incompletely understood. Mutations in genes encoding ion channels in these cell types are known to cause deafness and EP dysfunction. Previous studies have extensively delineated the critical functions that specific ionic channels accomplish, including their role in EP generation and in regulating ion homeostasis (Chen, J. and Zhao, H.B., 2014; Patuzzi, 2011; Zdebik et al., 2009).

Figure 1:

Schematic of Stria Vascularis (SV)

A, The mammalian cochlea consists of 3 fluid-filled chambers with two chambers (scala tympani and scala vestibuli) containing perilymph and one chamber (scala media) containing endolymph. The SV is housed in the lateral wall of the cochlea and its 3 main cell layers are composed of marginal cells (MC), intermediate cells (IC), and basal cells (BC), respectively, with the marginal cells facing the endolymph. The SV generates the highly positive endocochlear potential (+80 mV or greater) and is responsible for the high potassium concentration of the endolymph which distinguishes it from the perilymph in the other two fluid-filled chambers. Fibrocyte populations in the spiral ligament (Types I-V) are also depicted. B, Magnified view of the layers of the stria vascularis with major ion channels implicated in its function. Marginal cells excrete potassium into the endolymph and accomplish this process through their expression of a group of ion channels, including KCNE1/KCNQ1, SLC12A2, and NKA. Marginal cells are connected by tight junctions apically. Marginal cells extend processes basally toward the intermediate cells which also extend processes apically toward the marginal cells and basally towards the basal cells. Macrophages, pericytes, and endothelial cells form the basis for the blood-labyrinth barrier (BLB). The space between the marginal and intermediate cells forms the intrastrial space which has a low potassium and the inward-rectifier K+ channel, KCNJ10, concentrates potassium in the intermediate cells and is critical to the ability of the stria vascularis to both generate the endocochlear potential (EP) and regulate cochlear ionic homeostasis in the endolymph. Both basal and intermediate cells expression gap junctions. Basal cells along with intermediate cells and fibrocytes function together as a syncytium and are connected through gap junctions and maintain a barrier through a network of tight junctions. C, Rare spindle and root cells are located at the superior and inferior periphery of the stria vascularis and the region adjacent to the spindle cells, respectively. Inferiorly, the spindle cells overlie the spiral prominence and extend superiorly toward the edge of the stria vascularis, contacting marginal cells. Spindle cells and root cells both are known to express SLC26A4 (otherwise known as pendrin) and KCNJ16 (Korrapati, Taukulis et al., 2019; Gu et al., 2020). Abbreviations: Na+-K+-ATPase (NKA), Na+/K+/Cl− symporter 1 (SLC12A2), potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily E regulatory subunit 1 (KCNE1), potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q regulatory subunit 1 (KCNQ1), ATP-sensitive inward-rectifier potassium channel 10 (KCNJ10), solute carrier family 26 member 4 (SLC26A4) otherwise known as pendrin, potassium inwardly rectifying channel subfamily J member 16 (KCNJ16).

2.2. The Roles of the Stria Vascularis: Generation of the Endocochlear Potential (EP) and Blood-Labyrinth Barrier (BLB) Formation

SV cell types maintain the EP through the active transport of ions and tightly regulate the flow of molecules between the bloodstream and the endolymph, likely contributing to the blood-labyrinthine barrier (BLB). Through the active transport of potassium into SV intermediate cells, a resulting equilibration potential from a normally high potassium cytosolic concentration in intermediate cells and low potassium intrastrial space concentration is generated that is referred to as the endocochlear potential (Wangemann, 2006). Potassium recycling by the SV is thought to be involved in the establishment of the EP and the high potassium concentration in the endolymph (Hibino et al., 2010). The inner hair cells rely on a highly positive EP for appropriate mechanotransduction, which results in the release of neurotransmitter and the propagation of neural signaling to the cochlear afferent neurons via the spiral ganglion cells. Additionally, the EP is crucial for outer hair cell electromotility that allows for modulation of sound perception, acting as a cochlear amplifier (Wang et al., 2019). Work by others (Marcus, D. C. et al., 2002; Wangemann et al., 2004) supports the idea that K+ flux across KCNJ10 is critical to the ability to generate the endocochlear potential. Electrophysiology studies have shown that the intrastrial space, an extracellular space within the stria vascularis, is structurally isolated from the scala media and its associated potential, the intrastrial potential, is higher than the endocochlear potential despite its low K+ concentration (Adachi et al., 2013; Marcus et al., 2002). Low K+ concentration in the intrastrial space is maintained through active transport by transporters such as NKA, KCNJ10, and SLC12A2, of marginal cells (Figure 1B) (Adachi et al., 2013).

A few animal studies have shown the role of the major SV cell types in the generation of the EP and their overall importance in the hearing process. CLDN11 protein is encoded by the CLDN11 gene in human, and it is a known basal cell marker in the SV (Gow et al., 2004; Korrapati, Soumya et al., 2019). Cldn11 null mice exhibited low EP and were found to be deaf (Gow et al., 2004). The voltage-gated potassium channel Kv7.1, encoded by the human KCNQ1 gene located on 11p15.5-p15.4 of the human chromosome, is expressed in the marginal cells and plays an important role of K+ transport to maintain the EP. Results from animal studies have shown that Kcnq1 mutant mice and mutants of other marginal cell channel proteins including Kcne1 and Barttin (Bsnd) experience significant hearing loss with reduced EP, albeit not complete hearing loss, suggesting the contribution of marginal cells to EP generation (Chang et al., 2015; Faridi et al., 2019; Korrapati, Soumya et al., 2019; Riazuddin et al., 2009). Similarly, Kcnj10 mutant mice, whose protein product KCNJ10 is expressed by SV intermediate cells, exhibited loss of EP and deafness (Chen, J. and Zhao, H.-B., 2014; Marcus, Daniel C et al., 2002; Wangemann et al., 2004). Furthermore, early animal studies identified cochlear melanocytic intermediate cells within the SV as playing a role in EP maintenance (Cable et al., 1995). This finding has been supported by human embryonic studies, showing a significant role for SV cochlear melanocytes in the generation of the EP (Locher et al., 2015). Although animal studies have shown the importance of the SV marginal, intermediate and basal cells in EP generation, there is a need to investigate other SV cell types, including the role of spindle cells and pericytes, to fully elucidate the mechanisms of EP generation (Gu et al., 2020; Ito et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2021). Due to the heterogeneous nature of hearing loss, the SV specific proteins should be explored to understand the physiology of the SV.

The SV also contributes to the relatively privileged environment of the inner ear by forming a portion of the BLB. The BLB is formed by a specialized capillary network that tightly regulates the exchange of molecules between the systemic circulation and the vascular system of the inner ear. The strial microvasculature contains endothelial cells, tight and adherens junctions, pericytes, and resident macrophages to form a highly regulated barrier. This allows modulation of vascular permeability to facilitate the optimal molecular composition of the inner ear fluids for hearing function (Neng et al., 2015; Shi, 2016; Yang et al., 2011).

II. The Role of the Stria Vascularis (SV) in Common Causes of Sensorineural Hearing Loss (SNHL)

Numerous studies have implicated the SV in the pathogenesis of many common forms of SNHL, including age-related hearing loss (ARHL), noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL), hereditary hearing loss (HHL), and drug-included hearing loss (DIHL), among many others. While this review will focus on the role of the SV in a few examples of neglected otologic diseases, here we will briefly discuss and point the reader to relevant reviews of SV involvement in these commonly encountered causes of SNHL.

3.1. Age-related Hearing Loss (ARHL)

ARHL represents one of the most common forms of SNHL and likely results from various distinct etiologies. While ARHL has been shown to affect many structures within the inner ear, there have been studies that demonstrate profound changes within the SV that may contribute to this pathology (Keithley, 2020). Schuknecht proposed a distinct form of ARHL known as “strial presbycusis” based on evidence of strial marginal cell degeneration associated with suspected EP reduction (Schuknecht and Gacek, 1993). This pathology was further characterized in animal models by demonstrating variable EP reduction correlating with degree of marginal cell pathology that may be further influenced by various environmental and genetic factors, such as melanin synthesis (Ohlemiller, 2009). There have been many other documented changes to the SV in ARHL including mitochondrial dysmorphia (Xiong et al., 2011), ion transport channel dysregulation (Peixoto Pinheiro et al., 2021), oxidative stress (Spicer and Schulte, 2005), and macrophage-associated inflammation (Noble et al., 2019), among others. These findings support that the SV may play a role in certain types of ARHL.

3.2. Noise-induced Hearing Loss (NIHL)

NIHL represents another common etiology for SNHL, with multiple studies implicating damage to the SV as a possible pathway of hearing loss. Animal studies investigating NIHL have demonstrated pathology along the lateral wall of the cochlea associated with transient EP reductions, however, the persistent hearing loss despite EP recovery confounds the causal relationship between SV dysfunction and NIHL (Ohlemiller et al., 2018). Prior studies have demonstrated noise-associated changes to the SV including abnormal cochlear microcirculation and ischemia due to decrease in vessel size. This may resultant in increased permeability and macromolecular transport in the SV that could decrease the EP of the inner ear (Suzuki et al., 2002). These vascular changes may result in oxidative stress from NO-derived free radicals and inflammation within the SV (Han et al., 2018; Mizushima et al., 2017). Recent work by Milon and colleagues highlights transcriptional responses to noise at the single cell level in the cochlea, including the stria vascularis (Milon et al., 2021).

3.3. Hereditary Hearing Loss (HHL)

HHL represents a heterogeneous group of hearing disorders that may result from either syndromic or non-syndromic etiologies. The SV has been suggested to play a prominent role in the pathogenesis of multiple forms of HHL. Non-syndromic HHL represent the majority of HHL cases. Multiple studies have implicated genetic mutations that result in disruptions of the normal physiology of the SV, including epithelial regulatory protein 1 (ESRP1) (Rohacek et al., 2017) and ATP6V0A4 gene (Lorente-Canovas et al., 2013) may lead to decreased number of marginal cells and decreased EP, respectively. Pathological changes to the SV have been identified in numerous diseases of syndromic hearing loss, including Alport syndrome (Gratton et al., 2005), Norrie disease (Rehm et al., 2002), Lysosomal storage diseases (Wu et al., 2010), Jervell and Lange-Nielson syndrome (Neyroud et al., 1997), Pendred syndrome (Xue et al., 2021), and Waardenburg syndrome (Ni et al., 2013), among others. While these syndromic HHL disorders may result from a variety of genes, studies have highlighted multiple abnormalities of the SV in these processes, including thickening and enlargement of the capillary basement membrane (Gratton et al., 2005; Rehm et al., 2002), loss and vacuolization of marginal cells (Wu et al., 2010), and increased melanin pigmentation of the intermediate cells (Wangemann et al., 2004).

3.4. Drug-induced Hearing Loss (DIHL)

DIHL is another group of heterogeneous disease processes that result from the accumulation of ototoxic molecules within the inner ear. There are over 150 known ototoxic drug compounds, with a common pathway of hearing loss related to the trafficking of these molecules through the BLB of the SV (Kros and Steyger, 2019). While the exact mechanisms of DIHL remain poorly understood there have been a few studies that highlight damage to SV resulting in dysregulation of the EP and inflammation within the SV as a common pathway of hearing loss associated with drugs such as aminoglycosides (Moody et al., 2006), loop diuretics (Salt and Plontke, 2005), and platinum-based chemotherapeutics (Breglio et al., 2017; Taukulis et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020).

III. Evidence of Stria Vascularis (SV) Involvement in Neglected Causes of Sensorineural Hearing Loss (SNHL)

While the SV has been implicated in many common disorders of SNHL, there is growing evidence of its role in less common and often neglected causes of SNHL, including AIED/AID, MD, SSNHL, and CRHL.

4.1. Autoimmune Inner Ear Disease (AIED) and Autoinflammatory Inner Ear Disease (AID)

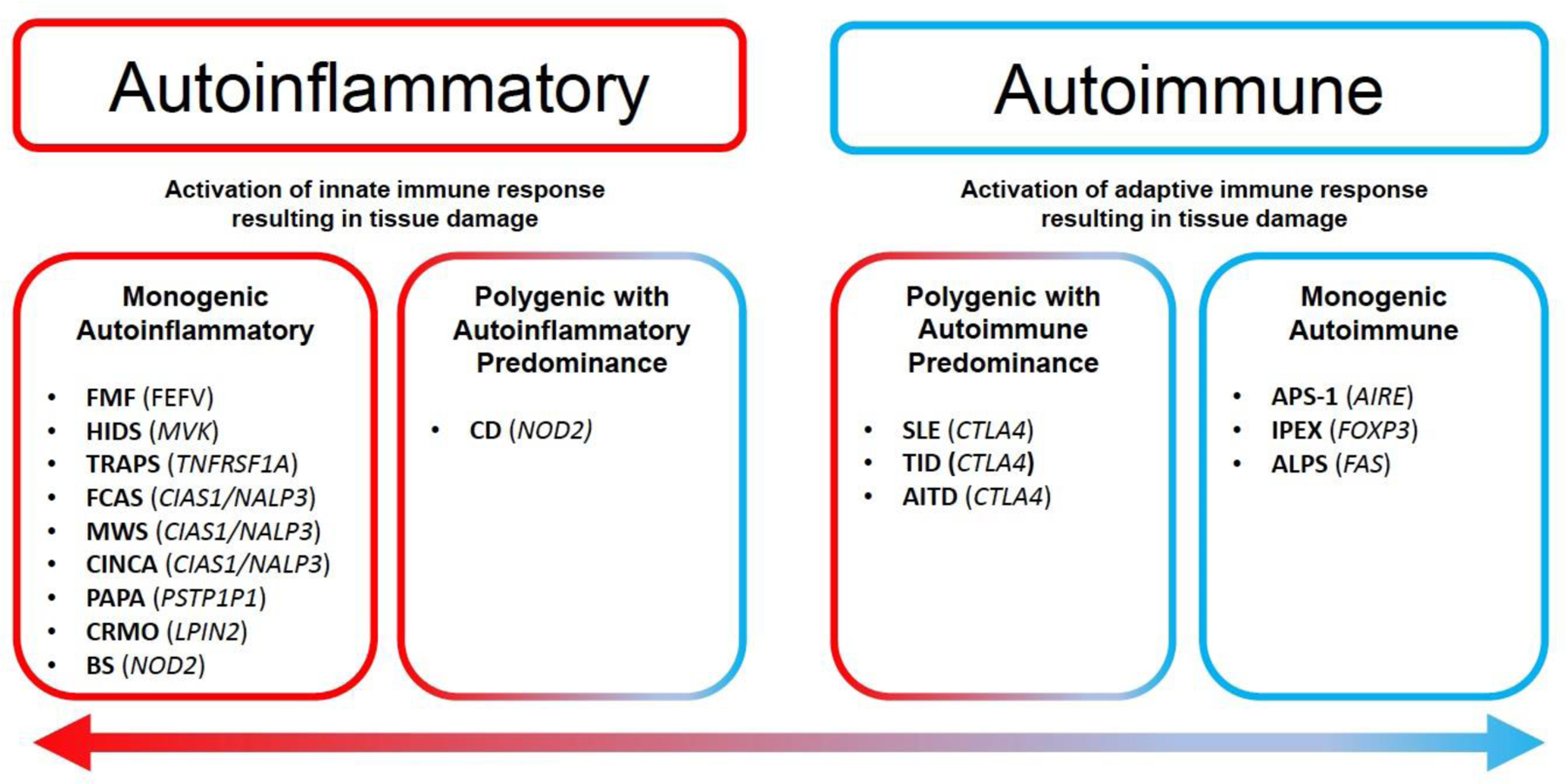

AIED and AID represent a spectrum of relatively rare disorders that result in SNHL that primarily involve the adaptive and innate immune systems, respectively (Figure 2). AIED, first described in the 1940s by Cogan (Norton and Cogan, 1959), has become an increasingly recognized entity. AIED is believed to be a relatively uncommon cause of SNHL, affecting 5–20 annual cases per 100,000 individuals in the United States while accounting for less than 1% of all cases of SNHL within the community (Peneda et al., 2019). These may either be primary in approximately 2/3 of cases or secondary to other systemic autoimmune conditions, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic vasculitis, among others (Mijovic et al., 2013). AID was first characterized in the context of the spectrum of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (Lorber, 1973; Muckle and Wellsm, 1962). Due to the variable disease severity and presentation of these disorders, diagnosis remains challenging but the estimated annual incidence of these disorders is approximately 1–2 cases per million in the United States (Toker and Hashkes, 2010).

Figure 2.

Spectrum of Autoinflammatory and Autoimmune Disorders

The figure depicts a few examples of self-directed inflammation disorders and the genes that have been associated with them. Self-directed inflammation disorders lie on a spectrum between autoinflammatory disorders, which involve proteins that are expressed in innate immune cell pathways, or autoimmune disorders, which involve proteins that are associated with adaptive immune pathways. There are disorders that may involve both innate and adaptive immune responses but present with prominent components of either autoimmune or autoinflammatory pathways as depicted.

(Adapted from McGonagle et al. (2006)(McGonagle and McDermott, 2006); AIRE, autoimmune regulator protein; ALPS, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome; APS-1, autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome-1; CIAS, cold-induced autoinflammatory syndrome 1; TNFRSF, TNF super family receptor; CINCA, chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous and articular syndrome; CMRO, chronic multifocal recurrent osteomyelitis; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4; FCAS, familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome; FMF, familial Mediterranean fever; HIDS, hyper-IgD syndrome; IPEX, immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked; FOXP3, forkhead box P3; FEFV, Mediterranean fever protein; MWS, Muckle-Wells syndrome; NALP, Nacht, LRR, and PYD domains; PSTPIP1, proline serine threonine phosphatase-interacting protein; NOD, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain; PAPA, pyogenic sterile arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; T1D, type 1 diabetes; TLR4, Toll receptor-4; TRAPS, TNF-receptor-associated periodic syndrome.)

There have been numerous animal models to investigate immune-mediated hearing loss (Goodall and Siddiq, 2015). While the exact pathogenesis remains incompletely understood, degeneration of the SV has been demonstrated. Previous animal studies have reported immunoglobulin deposition in the SV associated with destruction of the BLB (Trune, 1997). Other SV findings included degeneration of intermediate and marginal cells. Furthermore, there have been findings that correlate the degree of SNHL with severity of SV immune-related lesions (Kusakari et al., 1992). Ruckenstein and Hu demonstrated hydropic degeneration and immunoglobulin deposition within the SV, proposing the reduction of the EP directly resulted from the cellular degeneration within the SV (Ruckenstein and Hu, 1999). Despite these reports, there have not been adequate animal models to recapitulate human disease to completely understand the role of the SV in these disorders.

A recent review compiled temporal bone studies of autoimmune and autoinflammatory-related hearing disorders, including systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren’s syndrome, Cogan’s syndrome, systemic vasculitis, and cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome, among others (Samaha et al., 2021). These studies highlight histopathologic changes in the cochlea, including fibroosseous reaction (Schuknecht and Nadol, 1994), destruction of hair cells (Kariya et al., 2007), IgG deposition within the stria vascularis (Calzada et al., 2012) with loss or atrophy of the stria vascularis (Sone et al., 1999) and spiral neuron degeneration (Di Stadio and Ralli, 2017) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Highlighted Human Temporal Bone Studies for Neglected Otologic Diseases

| Autoimmune inner ear disease (AIED) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Sample | SV Findings |

| Schuknecht and Nadol (1994) | n=1 (AIED) | Atrophy of SV (1/1) |

| Sone et al. (1999) | n=5 (SLE) | Atrophy of SV (4/5) |

| Calzada et al. (2012) | n=4 (SS) | Atrophy of SV (4/4) |

| Di Stadio and Ralli (2017) | n=113 (SLE: 52, GPA: 22, SS: 20, Cogan: 8, AIED: 7) | Atrophy of SV (37/113) |

| Meniere’s Disease (MD) | ||

| Study | Sample | SV Findings |

| Kariya et al. (2009) | n=14 | Decreased mean number of blood vessels within SV (p<0.05) |

| Kariya et al. (2007) | n=14 | Atrophy of SV along ower middle turn (p<0.001) and apical turn (p=0.012) |

| Masutani et al. (1992) | n=8 | Fewer vessels with smaller crosssectional area of vessels within SV (p<0.05) |

| Ishiyama et al. (2007) | n=4 | Average of 21% decrease in volume of SV compared to control (p=0.01) |

| Merchant et al. (2005) | n=2 | Atrophy of SV (1/2) |

| Vasama et al. (1999) | n=21 | Decreased normal SV in MD compared to control (61% vs. 77%, p<0.05) |

| Fraysse et al. (1980) | n=17 | Atrophy of SV in “most cases” (not specified) |

| Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss (SSNHL) | ||

| Study | Sample | SV Findings |

| Merchant et al. (2005) | n=17 | Atrophy of SV (10/17) |

| Schuknecht and Donovan (1986) | n=12 | Atrophy of SV (6/12) |

| Yoon et al. (1990) | n=11 | Atrophy of SV (7/11) |

| Vasama et al. (2000) | n=12 | Atrophy of SV (12/12) |

| Khetarpal et al. (2015) | n=18 | Atrophy of SV (18/18) |

| Bahmad (2008) | n=1 | Atroiphy of SV (1/1) |

| Cytomegalovirus-related Hearing Loss (CRHL) | ||

| Study | Sample | SV Findings |

| Teissier et al. (2011) | n=6 (CMV infected human fetus) | Viral inclusions predominating in the marginal cell layer of the SV (5/6) |

| Gabrielli et al. (2013) | n=20 (CMV infected human fetus) | CMV infection identified in marginal cell of SV in 45%(9/20) of fetuses |

| Tsuprun et al. (2019) | n=2 (CMV infected human fetus) | Hypervascularization and enlarged blood vessesls in SV at all turns (1/2) |

Autoimmune inner ear disease (AIED), autoinflammatory inner ear disease (AID), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjogren’s syndrome (SS), Meniere’s disease (MD), stria vascularis (SV), sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL), CMV-related hearing loss (CHRL), cytomegalovirus (CMV)

4.2. Meniere’s Disease (MD)

MD represents another relatively rare and often neglected otologic disease characterized by fluctuating SNHL, tinnitus, aural fullness, and vertigo. Due to heterogeneity and fluctuating nature of the symptoms, MD has remained a challenging disease for diagnosis. In 2015, the Classification Committee of the Barany Society proposed an update to the diagnostic criteria for the disorder to include definite and probable MD, based on a combination of subjective symptomatology as well as documentation of audiometric criteria for low to medium-frequency SNHL (Lopez-Escamez et al., 2015). The reported prevalence of MD in the United States varies widely in the literature, ranging from 3.5 to 513 per 100,000 individuals (Alexander and Harris, 2010). While MD has been an increasingly recognized cause of SNHL, it remains an often neglected otologic disease due to its relative complexity in diagnosis with few effective therapeutic treatments.

Although the definitive pathophysiology of hearing loss in MD remains controversial, there have been multiple attempts to describe inner ear derangements that contribute to this disorder. Early temporal bone studies identified the association of endolymphatic hydrops (EH) in patients with MD (Hallpike and Cairns, 1938), proposing that dilatation of the hydropic endolymph compartments within the labyrinth contributed to the fluctuating symptoms of MD. More recent investigations have highlighted numerous hydropic findings in patients without any symptoms of MD (Merchant et al., 2005b). Given these findings, EH may represent a histological marker of MD rather than the etiology. Other human temporal bone studies have detailed abnormalities of the SV in MD-related hearing loss (Table 1). Many of these studies highlight cellular atrophy with decreased vascularity and cross-sectional area of the SV in MD patients compared to age-matched controls (Kakigi et al., 2020; Kariya et al., 2007; Kariya et al., 2009; Masutani et al., 1992). There have been many animal models developed to investigate MD (Seo and Brown, 2020). Examples include early the surgical endolymphatic sac ablation guinea pig model and the long-term administration of vasopressin mouse model of endolymphatic hydrops (Katagiri et al., 2014; Kimura and Schuknecht, 1965). Despite this controversy, the role of the SV continues to be a focus of the research in the pathogenesis of MD due to its contribution to the regulation of endolymph ionic composition.

4.3. Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss (SSNHL)

SSNHL is a disorder that is defined as a SNHL of at least 30 decibels (dB) over three contiguous audiometric frequencies that frequently develops over a 72-hour period (Chandrasekhar et al., 2019). The true incidence of SSNHL may be underreported, but is believed to be between 5 and 27 per 100,000 cases per year in the United States (Alexander and Harris, 2013). While SSNHL may result from various other exposures including ototoxic or vascular etiologies, up to 71% of these cases may be idiopathic in nature (Chau et al., 2010). The incidence of partially or completely reversible SSNHL varies in the literature, cited between 30–65%, with one report of a patient experiencing complete recovery approximately nine months following SSNHL (Ortmann and Neely, 2012).

While the pathogenesis of idiopathic SSNHL remains poorly understood, there are proposed theories that include viral-mediated cochlear inflammation, vascular occlusion, and membrane disruption (Merchant et al., 2005a). Glucocorticoids have remained the primary treatment modality in these patients. Investigations on the effect of steroids in the inner ear have demonstrated reduced activation of cellular stress pathways involving nuclear-factor-κ-B (NF-κB) and potential contributions to ion homeostasis through binding with mineralocorticoid receptors within the SV (Merchant et al., 2005a; Trune and Kempton, 2009). Despite these findings, the definitive mechanisms of SSNHL and recovery following steroid treatment remain poorly understood. Although there currently is a lack of validated animal models to investigate this disease process, there have been human temporal bone studies to investigate the role of the SV in SSNHL. A recent literature review of temporal bone studies of patients with SSNHL, including 71 total specimens across 6 studies, demonstrating histopathological abnormalities within the SV in 75% of patients (Nelson et al., 2021a) (Table 1).

4.4. Cytomegalovirus-related Hearing Loss (CRHL)

Congenital CMV (cCMV) represents a historically underrecognized cause of hearing loss, with SNHL representing the most common permanent sequelae of cCMV infection (Demmler, 1991). cCMV was first observed in 1964 and is believed to be the most common cause of pediatric non-hereditary SNHL. A systematic review in 2014 demonstrated that cCMV accounts for approximately 10–20% of all childhood SNHL (Goderis et al., 2014). The importance of early detection cannot be overstated, as there are data to support that effective treatment must be initiated within the first 4 weeks of life for optimal hearing outcomes (Jenks et al., 2021).

There are numerous animal studies to investigate the mechanisms of hearing loss in cCMV (Haller et al., 2020; Park et al., 2010; Teissier et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013). Studies have localized viral inclusions within marginal cells (Teissier et al., 2011) and described the subsequent damaging effects of vascular degeneration and capillary lesions, predominantly within the apical SV (Carraro et al., 2017). A recent investigation on the relationship between CMV-induced strial dysfunction in a murine model demonstrated reductions in EP amplitude due to dysregulation of ion exchange along the lateral wall (Yu et al., 2022). There have also been reports of the effects of CMV on hearing loss in human temporal bone studies. One group compared multiple case reports of temporal bone histopathology in cCMV patients, noting four cases that demonstrate inclusion bodies within the SV associated with cystic changes (Strauss, 1985). Another recent study reported histopathology findings of two newborns with congenital infection and two adults with acquired infection, contrasting the significantly greater pathological changes within the congenital cases (Tsuprun et al., 2019). The cCMV specimens demonstrated profound changes of the SV including loss of cellularity and hypervascularity, with edema focused of the intermediate cells. In contrast, the adult specimens remained relatively normal with one specimen noting increased melanin-like pigmentation of the SV, although the authors comment that this may be a normal variant (Table 1). These reports highlight the emerging importance of the SV in the pathogenesis of CRHL and support the need for further research directed at improved early detection and targeted interventions.

IV. Review of Recent Evidence for the Role of the Stria Vascularis (SV) in Neglected Otologic Diseases and Implications for Treatment

5.1. Application of sc- and snRNA-seq to Investigate Strial Dysfunction in Hearing Loss

The advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and single nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) techniques have revolutionized our understanding of biological systems, complex cellular events, and function of an individual cell in the context of its microenvironment. The sc- and snRNA-seq techniques employ next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies to generate RNA sequencing data from single cells or single nuclei and provides an opportunity to differentiate between the expression profiles of cells with high resolution (Hedlund and Deng, 2018).

Over the past few years, sc- and snRNA-seq techniques have been used to investigate the transcriptional profile and gene regulatory networks of the SV, contributing to a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms and SV-related hearing disorders (Gu et al., 2020). Results from these studies have identified cell type-specific gene regulatory networks (GRNs), which may play a role in generating the EP and in regulating ion homeostasis in the cochlea (Gu et al., 2020; Korrapati, S. et al., 2019). Furthermore, gene ontology (GO) analyses of these GRNs in major SV cell types have demonstrated enrichment of signaling pathways involved in several previously uncharacterized functions. For example, marginal cells were found to have genes enriched for protein kinase activity (GO:0019901) and calcium channel regulatory activity (GO:0005246). Not unexpectedly, basal cells were noted to be enriched for genes involved in focal adhesion (GO:0005925) and actin cytoskeleton (GO:0015629). Intermediate cells were enriched in genes involved in regulating transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter (GO:0006357) and RNA polymerase II regulatory region sequence-specific DNA binding (GO:0000977), perhaps supporting their central role in concentrating potassium and the need of these cells to produce the machinery necessary for this energy-intense process. Rare SV cell types, including spindle cells, as well as root cells, a cell type adjacent to the SV, were found to be enriched with genes in GO networks which may relate to their function in the inner ear. Specifically, analysis of the major GO networks of root cells suggested that they may be involved in immune cell differentiation (GO:0002313) and homeostasis (GO: 0001782). Among the top 5 GO networks shared by root and spindle cells are sensory perception of mechanical stimulus (GO:0050954) and sensory perception of sound (GO:0007605) which supports the involvement of these cell types in the hearing process.

Single cell (sc-) and single nuclei (sn-) RNA-seq have been shown to be valuable tools in identifying specific SV cell types associated with these otologic diseases (Gu et al., 2021; Korrapati, S. et al., 2019). Transcriptomic profiles of SV cell types have been used to implicate both marginal and intermediate cells in the development of MD. Results from the transcriptomic data localize the RNA of mouse homologues of genes with known variants in MD (Dai et al., 2019; Gallego-Martinez et al., 2019), including Esrrb and Kcne1, to adult mouse marginal cells (Korrapati, S. et al., 2019). Additionally, RNA and protein, respectively, of mouse homologues of MET (Korrapati, S. et al., 2019), GJB2, and GJB6 (Liu et al., 2009; Locher et al., 2015) were reported to be localized to the intermediate and basal cells while Slc26a4 and P2rx2 RNA were localized to the spindle cells (Gu et al., 2021). Met encodes a receptor kinase which regulates cell proliferation, morphogenesis and survival, and variants in MET have been associated with autosomal recessive hearing loss in humans (Mujtaba et al., 2015). Variants in GJB2 and GJB6 have been extensively reported in hearing-impaired patients globally and GJB2 variants alone accounts for about 50% of non-syndromic hearing loss cases (Adadey et al., 2020). Similarly, SLC26A4 (Li et al., 1998) and P2RX2 (Yan et al., 2013) variants are associated with hearing loss in humans. The loss of Slc26a4 in spindle cells has been implicated in the phenomenon of hearing fluctuation (Choi et al., 2011; Ito et al., 2014). The function of these genes, their localization to specific SV spindle cells, which may have a role in hearing fluctuation (Ito et al., 2014), coupled to their association with hearing loss in humans suggest a role in the development of hearing loss or instability.

5.2. Application of sc- and snRNA-seq to identify SV pharmacological targets

Although corticosteroids are widely used to treat some of these disorders, including SSNHL, AIED/AID, and MD, the response to treatment varies widely across patients (Andrianakis et al., 2022; Chandrasekhar et al., 2019; Fisher et al., 2012; Hara et al., 2018; Li and Ding, 2020; Mirian and Ovesen, 2020; Siegel, 1975; Song et al., 2021; Wilson et al., 1980; Witsell et al., 2018; Wycherly et al., 2011). Experimental work in mouse models suggests that steroids interact with multiple signaling pathways and targets in the cochlea, implicating various possible mechanisms of action (MacArthur et al., 2015; Maeda et al., 2018; Nelson et al., 2021b; Trune et al., 2019). Data from sc- and snRNA-seq studies coupled with transcriptome studies examining the effects of steroids on the cochlea suggest that corticosteroids may be acting on the SV, organ of Corti and spiral ganglion neurons (Nelson et al., 2021b). Steroid-responsive genes, Nr3c1, Nr3c2, and Cacna1d were among the genes identified to be highly expressed in the above inner ear tissues. Within the SV, Cacna1d was mostly expressed in the marginal cells. It is worth noting that the route of corticosteroid administration was reported to influence the regulation and expression of certain gene networks in the inner ear (Creber et al., 2018; Nelson et al., 2021b; Wang et al., 2018). Anti-inflammatory, cell stress response, and apoptotic pathways were found to be possible pathways transduced by steroid-responsive genes in the spiral ganglion neurons (Nelson et al., 2021b). The heterogeneity observed in steroid treatment may be due to the variety of the inner ear cell types that express steroid-responsive genes and needs further investigation.

Drug repurposing for rare and common disease has become increasingly important due to the long time and high cost associated with drug discovery and development. Drug repurposing involves the use of existing Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs and has been associated with reduced potential patient risk as well as lower development cost and time (Pushpakom et al., 2019). Researchers have highlighted the potential of using sc- and snRNA-seq data to identify druggable gene and FDA approved drugs that can be repurposed for neglected otologic diseases (Korrapati, S. et al., 2019) using parallel gene regulatory network inference methods (Tremblay et al., 2019) in combination with Pharos (Nguyen et al., 2017). Using these in silico approaches, several druggable genes in Esrrb and Bmyc regulons were identified along with their candidate FDA-approved drugs (Korrapati, S. et al., 2019) (Table 2). These identified drugs represent potential therapeutics for future investigation to treat SV-related disorders of hearing loss.

Table 2:

Druggable gene targets and FDA approved drugs that can be potentially repurposed for neglected otologic diseases

| Regulons | Gene | Pharmacologic drug class | Stria vascularis cell types* | FDA-approved drugs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activator | Inhibitor | Unknown | ||||

| Esrrb regulons | Pde4 | Enzyme | IC, SR, BC | Chlorine theophyllinate Rofumilast Amlexano Flavoxate Bufylline |

||

| Prkcd | Kinase | MC | Inge nol Meb utate |

|||

| Fgfr1 | Kinase | MC, BC | Lenvatinib Ponatinib |

Sora tenib |

||

| Adora1 | GPCR | MC | Adenosine | Theophylline Bufylline Caffeine |

||

| Esrrb | MC | Estra diol |

||||

| P2ry2 | GPCR | MC, BC | Diquofisol | |||

| Kcnma1 | Ion channel | MC | Chlorzoxazone | |||

| Ano1 | Ion channel | MC | Crof Elem er |

|||

| Hdac5 | Enzyme | All SV cell types | Panobinostat Belinostat |

|||

| Ghr | Receptor | All SV cell types | Somatremm Somatotropin |

Pegvisimont | ||

| Igf1r | Kinase | All SV cell types | Mescasermin | Brigatinib | Certi nib |

|

| Bmyc regulons | Ca14 | Enzyme | All SV cell types | Furosemide Zoledronic Acetazolamide Dichlorphenamide Ethoxzolamide |

||

| Cdk4 | Kinase | All SV cell types | Palbociclib Ribociclib |

|||

| Atp1a4 | Transporter | BC, Fc | Deslanoside Digoxin Acetyldigoxin |

|||

| Abca1 | Transporter | IC > MC | Probucol | |||

| Grik5 | Ion channel | All SV cell types | Topiramate | |||

| Ano1 | Ion channel | MC | Crof Elem er |

|||

| Ndufb2 | Enzyme | All SV cell types | Metformin | |||

| Tyr | Enzyme | IC | Mequinol Monobenzone Avobenzone |

|||

| Rarg | Receptor | All SV cell types | Acitretin | |||

| Rara | Receptor | MC | Etretinate Acitretin Tazarotene Aliretinoin Adapalene |

|||

| Rarb | Receptor | IC > BC, SR | Tazarotene Aliretinoin |

Ada pale ne |

||

Stria vascularis (SV) cell types in which the genes are predominantly expressed. Marginal cell (MC), Intermediate cell (IC), Basal cell (BC), Spindle-root cells (SR), Fibrocyte (Fc)

Adapted from Korrapati et al,. 2019

V. Conclusion:

The major functions of the SV include contributions to generation and maintenance of the EP, regulation of cochlear ionic homeostasis, and BLB formation. Advances in our understanding of the transcriptional contributions to these functions at the cellular level through single-cell and single-nucleus transcriptome datasets have enhanced our understanding of how SV cell types contribute to these functions. Despite this knowledge, the mechanisms by which the SV accomplishes these, and other functions remain incompletely defined. Structural effects on the SV as well as genetic mutations associated with genes expressed by SV cell types in clinically neglected otologic diseases (such as AIED/AID, MD, SSNHL, and CRHL) implicate the SV in these diseases. Despite the growing body of literature, there is a need for further investigation into the role of the SV to develop enhanced diagnostic and treatment modalities for these disorders.

VI. Expert comments and future directions

Compared to the three major cell types of the SV (marginal, medial, and basal cells), little is known of other SV cells including, spindle cells, pericytes, melanocytes, and endothelial cells, and how they contribute to the overall function of the SV. There is a need to investigate these subsets of SV cells and their contribution to otologic diseases in humans.

The mechanisms of pathogenesis of neglected otologic diseases remain to be elucidated, and this has contributed to the poor diagnosis and treatment associated with these disorders. Future research should focus on molecular identification of biomarkers towards the development of diagnostics and treatment options.

Human temporal bones have been a useful resource to study the ear and its associated disorders. However, there are major challenges associated with the analysis of human temporal bone. Synchrotron technology (Li et al., 2021) might be more accurate and potentially faster to study the effects of these diseases at the structural, tissue, and potentially cellular level in human temporal bones.

Highlights.

Single-cell and single-nucleus transcriptional datasets of the stria vascularis (SV) have enhanced our understanding of the cellular contributions to major SV functions, which include the generation of the endocochlear potential, regulation of cochlear ionic homeostasis, and formation of the blood-labyrinth barrier.

A growing body of evidence, at both the tissue and cellular level, implicates pathology and dysfunction of the stria vascularis in neglected otologic diseases, including Meniere’s disease (MD), autoimmune and/or autoinflammatory inner ear disease (AIED/AID), sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL), and cytomegalovirus-related hearing loss (CRHL).

Acknowledgements:

Alan Hoofring: Figure 1 creation

Funding:

This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIDCD to M.H. (DC000088).

Abbreviations:

- SV

stria vascularis

- SNHL

sensorineural hearing loss

- AIED

autoimmune inner ear disease

- AID

autoinflammatory inner ear disease

- MD

Meniere’s disease

- SSNHL

sudden sensorineural hearing loss

- CRHL

cytomegalovirus-related hearing loss

- ARHL

age-related hearing loss

- NIHL

noise-induced hearing loss

- HHL

hereditary hearing loss

- DIHL

drug-induced hearing loss

- EP

endocochlear potential

- BLB

blood-labyrinthine barrier

- GO

gene ontology

- GRN

gene regulatory networks

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- Adachi N, Yoshida T, Nin F, Ogata G, Yamaguchi S, Suzuki T, Komune S, Hisa Y, Hibino H, Kurachi Y, 2013. The mechanism underlying maintenance of the endocochlear potential by the K+ transport system in fibrocytes of the inner ear. J Physiol 591(18), 4459–4472. 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.258046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adadey SM, Wonkam-Tingang E, Twumasi Aboagye E, Nayo-Gyan DW, Boatemaa Ansong M, Quaye O, Awandare GA, Wonkam A, 2020. Connexin Genes Variants Associated with Non-Syndromic Hearing Impairment: A Systematic Review of the Global Burden. Life (Basel) 10(11). 10.3390/life10110258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander TH, Harris JP, 2010. Current epidemiology of Meniere’s syndrome. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 43(5), 965–970. 10.1016/j.otc.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander TH, Harris JP, 2013. Incidence of sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otol Neurotol 34(9), 1586–1589. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrianakis A, Moser U, Kiss P, Holzmeister C, Andrianakis D, Tomazic PV, Wolf A, Graupp M, 2022. Comparison of two different intratympanic corticosteroid injection protocols as salvage treatments for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 279(2), 609–618. 10.1007/s00405-021-06676-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breglio AM, Rusheen AE, Shide ED, Fernandez KA, Spielbauer KK, McLachlin KM, Hall MD, Amable L, Cunningham LL, 2017. Cisplatin is retained in the cochlea indefinitely following chemotherapy. Nat Commun 8(1), 1654. 10.1038/s41467-017-01837-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cable J, Jackson IJ, Steel KP, 1995. Mutations at the W locus affect survival of neural crest-derived melanocytes in the mouse. Mech Dev 50(2–3), 139–150. 10.1016/0925-4773(94)00331-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada AP, Balaker AE, Ishiyama G, Lopez IA, Ishiyama A, 2012. Temporal bone histopathology and immunoglobulin deposition in Sjogren’s syndrome. Otol Neurotol 33(2), 258–266. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318241b548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro M, Almishaal A, Hillas E, Firpo M, Park A, Harrison RV, 2017. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Infection Causes Degeneration of Cochlear Vasculature and Hearing Loss in a Mouse Model. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 18(2), 263–273. 10.1007/s10162-016-0606-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar SS, Tsai Do BS, Schwartz SR, Bontempo LJ, Faucett EA, Finestone SA, Hollingsworth DB, Kelley DM, Kmucha ST, Moonis G, Poling GL, Roberts JK, Stachler RJ, Zeitler DM, Corrigan MD, Nnacheta LC, Satterfield L, 2019. Clinical Practice Guideline: Sudden Hearing Loss (Update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 161(1_suppl), S1–S45. 10.1177/0194599819859885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Q, Wang J, Li Q, Kim Y, Zhou B, Wang Y, Li H, Lin X, 2015. Virally mediated Kcnq1 gene replacement therapy in the immature scala media restores hearing in a mouse model of human Jervell and Lange-Nielsen deafness syndrome. EMBO molecular medicine 7(8), 1077–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau JK, Lin JR, Atashband S, Irvine RA, Westerberg BD, 2010. Systematic review of the evidence for the etiology of adult sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope 120(5), 1011–1021. 10.1002/lary.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Zhao H-B, 2014. The role of an inwardly rectifying K+ channel (Kir4. 1) in the inner ear and hearing loss. Neuroscience 265, 137–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Zhao HB, 2014. The role of an inwardly rectifying K(+) channel (Kir4.1) in the inner ear and hearing loss. Neuroscience 265, 137–146. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BY, Kim HM, Ito T, Lee KY, Li X, Monahan K, Wen Y, Wilson E, Kurima K, Saunders TL, Petralia RS, Wangemann P, Friedman TB, Griffith AJ, 2011. Mouse model of enlarged vestibular aqueducts defines temporal requirement of Slc26a4 expression for hearing acquisition. J Clin Invest 121(11), 4516–4525. 10.1172/JCI59353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creber NJ, Eastwood HT, Hampson AJ, Tan J, O’Leary SJ, 2018. A comparison of cochlear distribution and glucocorticoid receptor activation in local and systemic dexamethasone drug delivery regimes. Hear Res 368, 75–85. 10.1016/j.heares.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Q, Wang D, Zheng H, 2019. The Polymorphic Analysis of the Human Potassium Channel KCNE Gene Family in Meniere’s Disease-A Preliminary Study. J Int Adv Otol 15(1), 130–134. 10.5152/iao.2019.5076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmler GJ, 1991. Infectious Diseases Society of America and Centers for Disease Control. Summary of a workshop on surveillance for congenital cytomegalovirus disease. Rev Infect Dis 13(2), 315–329. 10.1093/clinids/13.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stadio A, Ralli M, 2017. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and hearing disorders: Literature review and meta-analysis of clinical and temporal bone findings. J Int Med Res 45(5), 1470–1480. 10.1177/0300060516688600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faridi R, Tona R, Brofferio A, Hoa M, Olszewski R, Schrauwen I, Assir MZ, Bandesha AA, Khan AA, Rehman AU, 2019. Mutational and phenotypic spectra of KCNE1 deficiency in Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome and Romano-Ward syndrome. Human mutation 40(2), 162–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LM, Derebery MJ, Friedman RA, 2012. Oral steroid treatment for hearing improvement in Meniere’s disease and endolymphatic hydrops. Otol Neurotol 33(9), 1685–1691. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31826dba83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Martinez A, Requena T, Roman-Naranjo P, Lopez-Escamez JA, 2019. Excess of Rare Missense Variants in Hearing Loss Genes in Sporadic Meniere Disease. Front Genet 10, 76. 10.3389/fgene.2019.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goderis J, De Leenheer E, Smets K, Van Hoecke H, Keymeulen A, Dhooge I, 2014. Hearing loss and congenital CMV infection: a systematic review. Pediatrics 134(5), 972–982. 10.1542/peds.2014-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall AF, Siddiq MA, 2015. Current understanding of the pathogenesis of autoimmune inner ear disease: a review. Clin Otolaryngol 40(5), 412–419. 10.1111/coa.12432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow A, Davies C, Southwood CM, Frolenkov G, Chrustowski M, Ng L, Yamauchi D, Marcus DC, Kachar B, 2004. Deafness in Claudin 11-null mice reveals the critical contribution of basal cell tight junctions to stria vascularis function. Journal of Neuroscience 24(32), 7051–7062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton MA, Rao VH, Meehan DT, Askew C, Cosgrove D, 2005. Matrix metalloproteinase dysregulation in the stria vascularis of mice with Alport syndrome: implications for capillary basement membrane pathology. Am J Pathol 166(5), 1465–1474. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62363-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S, Olszewski R, Nelson L, Gallego-Martinez A, Lopez-Escamez JA, Hoa M, 2021. Identification of Potential Meniere’s Disease Targets in the Adult Stria Vascularis. Front Neurol 12, 630561. 10.3389/fneur.2021.630561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S, Olszewski R, Taukulis I, Wei Z, Martin D, Morell RJ, Hoa M, 2020. Characterization of rare spindle and root cell transcriptional profiles in the stria vascularis of the adult mouse cochlea. Sci Rep 10(1), 18100. 10.1038/s41598-020-75238-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller TJ, Price MS, Lindsay SR, Hillas E, Seipp M, Firpo MA, Park AH, 2020. Effects of ganciclovir treatment in a murine model of cytomegalovirus-induced hearing loss. Laryngoscope 130(4), 1064–1069. 10.1002/lary.28134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallpike CS, Cairns H, 1938. Observations on the Pathology of Meniere’s Syndrome: (Section of Otology). Proc R Soc Med 31(11), 1317–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han WJ, Shi XR, Nuttall A, 2018. Distribution and change of peroxynitrite in the guinea pig cochlea following noise exposure. Biomed Rep 9(2), 135–141. 10.3892/br.2018.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara JH, Zhang JA, Gandhi KR, Flaherty A, Barber W, Leung MA, Burgess LP, 2018. Oral and intratympanic steroid therapy for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol 3(2), 73–77. 10.1002/lio2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund E, Deng Q, 2018. Single-cell RNA sequencing: Technical advancements and biological applications. Mol Aspects Med 59, 36–46. 10.1016/j.mam.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino H, Nin F, Tsuzuki C, Kurachi Y, 2010. How is the highly positive endocochlear potential formed? The specific architecture of the stria vascularis and the roles of the ion-transport apparatus. Pflugers Arch 459(4), 521–533. 10.1007/s00424-009-0754-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Li X, Kurima K, Choi BY, Wangemann P, Griffith AJ, 2014. Slc26a4-insufficiency causes fluctuating hearing loss and stria vascularis dysfunction. Neurobiol Dis 66, 53–65. 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenks CM, Mithal LB, Hoff SR, 2021. Early Identification and Management of Congenital Cytomegalovirus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 54(6), 1117–1127. 10.1016/j.otc.2021.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakigi A, Egami N, Uehara N, Fujita T, Nibu KI, Yamashita S, Yamasoba T, 2020. Live imaging and functional changes of the inner ear in an animal model of Meniere’s disease. Sci Rep 10(1), 12271. 10.1038/s41598-020-68352-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariya S, Cureoglu S, Fukushima H, Kusunoki T, Schachern PA, Nishizaki K, Paparella MM, 2007. Histopathologic changes of contralateral human temporal bone in unilateral Meniere’s disease. Otol Neurotol 28(8), 1063–1068. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31815a8433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariya S, Cureoglu S, Fukushima H, Nomiya S, Nomiya R, Schachern PA, Nishizaki K, Paparella MM, 2009. Vascular findings in the stria vascularis of patients with unilateral or bilateral Meniere’s disease: a histopathologic temporal bone study. Otol Neurotol 30(7), 1006–1012. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181b4ec89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri Y, Takumida M, Hirakawa K, Anniko M, 2014. Long-term administration of vasopressin can cause Ménière’s disease in mice. Acta Otolaryngol 134(10), 990–1004. 10.3109/00016489.2014.902989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keithley EM, 2020. Pathology and mechanisms of cochlear aging. J Neurosci Res 98(9), 1674–1684. 10.1002/jnr.24439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Ricci AJ, 2022. In vivo real-time imaging reveals megalin as the aminoglycoside gentamicin transporter into cochlea whose inhibition is otoprotective. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119(9). 10.1073/pnas.2117946119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura RS, Schuknecht H, 1965. Membranous hydrops in the inner ear of the guinea pig after obliteration of the endolymphatic sac. Orl 27(6), 343–354. [Google Scholar]

- Korrapati S, Taukulis I, Olszewski R, Pyle M, Gu S, Singh R, Griffiths C, Martin D, Boger E, Morell RJ, Hoa M, 2019. Single Cell and Single Nucleus RNA-Seq Reveal Cellular Heterogeneity and Homeostatic Regulatory Networks in Adult Mouse Stria Vascularis. Front Mol Neurosci 12, 316. 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kros CJ, Steyger PS, 2019. Aminoglycoside- and Cisplatin-Induced Ototoxicity: Mechanisms and Otoprotective Strategies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 9(11). 10.1101/cshperspect.a033548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusakari C, Hozawa K, Koike S, Kyogoku M, Takasaka T, 1992. MRL/MP-lpr/lpr mouse as a model of immune-induced sensorineural hearing loss. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 157, 82–86. 10.1177/0003489492101s1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Helpard L, Ekeroot J, Rohani SA, Zhu N, Rask-Andersen H, Ladak HM, Agrawal S, 2021. Three-dimensional tonotopic mapping of the human cochlea based on synchrotron radiation phase-contrast imaging. Scientific reports 11(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ding L, 2020. Effectiveness of Steroid Treatment for Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann Pharmacother 54(10), 949–957. 10.1177/1060028020908067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XC, Everett LA, Lalwani AK, Desmukh D, Friedman TB, Green ED, Wilcox ER, 1998. A mutation in PDS causes non-syndromic recessive deafness. Nat Genet 18(3), 215–217. 10.1038/ng0398-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Bostrom M, Kinnefors A, Rask-Andersen H, 2009. Unique expression of connexins in the human cochlea. Hear Res 250(1–2), 55–62. 10.1016/j.heares.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locher H, de Groot JC, van Iperen L, Huisman MA, Frijns JH, Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM, 2015. Development of the stria vascularis and potassium regulation in the human fetal cochlea: Insights into hereditary sensorineural hearing loss. Dev Neurobiol 75(11), 1219–1240. 10.1002/dneu.22279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Escamez JA, Carey J, Chung WH, Goebel JA, Magnusson M, Mandala M, Newman-Toker DE, Strupp M, Suzuki M, Trabalzini F, Bisdorff A, Classification Committee of the Barany, S., Japan Society for Equilibrium, R., European Academy of, O., Neurotology, Equilibrium Committee of the American Academy of, O.-H., Neck, S., Korean Balance, S., 2015. Diagnostic criteria for Meniere’s disease. J Vestib Res 25(1), 1–7. 10.3233/VES-150549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber J, 1973. Syndrome for diagnosis: dwarfing, persistently open fontanelle; recurrent meningitis; recurrent subdural effusions with temporary alternate-sided hemiplegia; high-tone deafness; visual defect with pseudopapilloedema; slowing intellectual development; recurrent acute polyarthritis; erythema marginatum, splenomegaly and iron-resistant hypochromic anaemia. Proc R Soc Med 66(11), 1070–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorente-Canovas B, Ingham N, Norgett EE, Golder ZJ, Karet Frankl FE, Steel KP, 2013. Mice deficient in H+-ATPase a4 subunit have severe hearing impairment associated with enlarged endolymphatic compartments within the inner ear. Dis Model Mech 6(2), 434–442. 10.1242/dmm.010645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur C, Hausman F, Kempton B, Trune DR, 2015. Intratympanic Steroid Treatments May Improve Hearing via Ion Homeostasis Alterations and Not Immune Suppression. Otol Neurotol 36(6), 1089–1095. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y, Kariya S, Omichi R, Noda Y, Sugaya A, Fujimoto S, Nishizaki K, 2018. Targeted PCR Array Analysis of Genes in Innate Immunity and Glucocorticoid Signaling Pathways in Mice Cochleae Following Acoustic Trauma. Otol Neurotol 39(7), e593–e600. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus DC, Wu T, Wangemann P, Kofuji P, 2002. KCNJ10 (Kir4.1) potassium channel knockout abolishes endocochlear potential. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 282(2), C403–407. 10.1152/ajpcell.00312.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus DC, Wu T, Wangemann P, Kofuji P, 2002. KCNJ10 (Kir4. 1) potassium channel knockout abolishes endocochlear potential. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 282(2), C403–C407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masutani H, Takahashi H, Sando I, 1992. Stria vascularis in Meniere’s disease: a quantitative histopathological study. Auris Nasus Larynx 19(3), 145–152. 10.1016/s0385-8146(12)80034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonagle D, McDermott MF, 2006. A proposed classification of the immunological diseases. PLoS Med 3(8), e297. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant SN, Adams JC, Nadol JB Jr., 2005a. Pathology and pathophysiology of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otol Neurotol 26(2), 151–160. 10.1097/00129492-200503000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant SN, Adams JC, Nadol JB Jr., 2005b. Pathophysiology of Meniere’s syndrome: are symptoms caused by endolymphatic hydrops? Otol Neurotol 26(1), 74–81. 10.1097/00129492-200501000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mijovic T, Zeitouni A, Colmegna I, 2013. Autoimmune sensorineural hearing loss: the otologyrheumatology interface. Rheumatology (Oxford) 52(5), 780–789. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milon B, Shulman ED, So KS, Cederroth CR, Lipford EL, Sperber M, Sellon JB, Sarlus H, Pregernig G, Shuster B, Song Y, Mitra S, Orvis J, Margulies Z, Ogawa Y, Shults C, Depireux DA, Palermo AT, Canlon B, Burns J, Elkon R, Hertzano R, 2021. A cell-type-specific atlas of the inner ear transcriptional response to acoustic trauma. Cell Rep 36(13), 109758. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirian C, Ovesen T, 2020. Intratympanic vs Systemic Corticosteroids in First-line Treatment of Idiopathic Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 146(5), 421–428. 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima Y, Fujimoto C, Kashio A, Kondo K, Yamasoba T, 2017. Macrophage recruitment, but not interleukin 1 beta activation, enhances noise-induced hearing damage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 493(2), 894–900. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.09.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody MW, Lang H, Spiess AC, Smythe N, Lambert PR, Schmiedt RA, 2006. Topical application of mitomycin C to the middle ear is ototoxic in the gerbil. Otol Neurotol 27(8), 1186–1192. 10.1097/01.mao.0000226306.43951.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muckle TJ, Wellsm, 1962. Urticaria, deafness, and amyloidosis: a new heredo-familial syndrome. Q J Med 31, 235–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujtaba G, Schultz JM, Imtiaz A, Morell RJ, Friedman TB, Naz S, 2015. A mutation of MET, encoding hepatocyte growth factor receptor, is associated with human DFNB97 hearing loss. J Med Genet 52(8), 548–552. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson L, Johns JD, Gu S, Hoa M, 2021a. Utilizing Single Cell RNA-Sequencing to Implicate Cell Types and Therapeutic Targets for SSNHL in the Adult Cochlea. Otol Neurotol 42(10), e1410–e1421. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000003356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson L, Lovett B, Johns JD, Gu S, Choi D, Trune D, Hoa M, 2021b. In silico Single-Cell Analysis of Steroid-Responsive Gene Targets in the Mammalian Cochlea. Front Neurol 12, 818157. 10.3389/fneur.2021.818157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neng L, Zhang J, Yang J, Zhang F, Lopez IA, Dong M, Shi X, 2015. Structural changes in thestrial blood-labyrinth barrier of aged C57BL/6 mice. Cell Tissue Res 361(3), 685–696. 10.1007/s00441-015-2147-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyroud N, Tesson F, Denjoy I, Leibovici M, Donger C, Barhanin J, Faure S, Gary F, Coumel P, Petit C, Schwartz K, Guicheney P, 1997. A novel mutation in the potassium channel gene KVLQT1 causes the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen cardioauditory syndrome. Nat Genet 15(2), 186–189. 10.1038/ng0297-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DT, Mathias S, Bologa C, Brunak S, Fernandez N, Gaulton A, Hersey A, Holmes J, Jensen LJ, Karlsson A, Liu G, Ma’ayan A, Mandava G, Mani S, Mehta S, Overington J, Patel J, Rouillard AD, Schurer S, Sheils T, Simeonov A, Sklar LA, Southall N, Ursu O, Vidovic D, Waller A, Yang J, Jadhav A, Oprea TI, Guha R, 2017. Pharos: Collating protein information to shed light on the druggable genome. Nucleic Acids Res 45(D1), D995–D1002. 10.1093/nar/gkw1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni C, Zhang D, Beyer LA, Halsey KE, Fukui H, Raphael Y, Dolan DF, Hornyak TJ, 2013. Hearing dysfunction in heterozygous Mitf(Mi-wh)/+ mice, a model for Waardenburg syndrome type 2 and Tietz syndrome. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 26(1), 78–87. 10.1111/pcmr.12030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble KV, Liu T, Matthews LJ, Schulte BA, Lang H, 2019. Age-Related Changes in Immune Cells of the Human Cochlea. Front Neurol 10, 895. 10.3389/fneur.2019.00895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton EW, Cogan DG, 1959. Syndrome of nonsyphilitic interstitial keratitis and vestibuloauditory symptoms; a long-term follow-up. AMA Arch Ophthalmol 61(5), 695–697. 10.1001/archopht.1959.00940090697004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlemiller KK, 2009. Mechanisms and genes in human strial presbycusis from animal models. Brain Res 1277, 70–83. 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.02.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlemiller KK, Kaur T, Warchol ME, Withnell RH, 2018. The endocochlear potential as an indicator of reticular lamina integrity after noise exposure in mice. Hear Res 361, 138–151. 10.1016/j.heares.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortmann AJ, Neely JG, 2012. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss and delayed complete sudden spontaneous recovery. J Am Acad Audiol 23(4), 249–255. 10.3766/jaaa.23.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park AH, Gifford T, Schleiss MR, Dahlstrom L, Chase S, McGill L, Li W, Alder SC, 2010. Development of cytomegalovirus-mediated sensorineural hearing loss in a Guinea pig model. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 136(1), 48–53. 10.1001/archoto.2009.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patuzzi R, 2011. Ion flow in stria vascularis and the production and regulation of cochlear endolymph and the endolymphatic potential. Hear Res 277(1–2), 4–19. 10.1016/j.heares.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto Pinheiro B, Vona B, Lowenheim H, Ruttiger L, Knipper M, Adel Y, 2021. Age-related hearing loss pertaining to potassium ion channels in the cochlea and auditory pathway. Pflugers Arch 473(5), 823–840. 10.1007/s00424-020-02496-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peneda JF, Lima NB, Monteiro F, Silva JV, Gama R, Conde A, 2019. Immune-Mediated Inner Ear Disease: Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp (Engl Ed) 70(2), 97–104. 10.1016/j.otorri.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushpakom S, Iorio F, Eyers PA, Escott KJ, Hopper S, Wells A, Doig A, Guilliams T, Latimer J, McNamee C, Norris A, Sanseau P, Cavalla D, Pirmohamed M, 2019. Drug repurposing: progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Drug Discov 18(1), 41–58. 10.1038/nrd.2018.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm HL, Zhang DS, Brown MC, Burgess B, Halpin C, Berger W, Morton CC, Corey DP, Chen ZY, 2002. Vascular defects and sensorineural deafness in a mouse model of Norrie disease. J Neurosci 22(11), 4286–4292. https://doi.org/2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riazuddin S, Anwar S, Fischer M, Ahmed ZM, Khan SY, Janssen AG, Zafar AU, Scholl U, Husnain T, Belyantseva IA, 2009. Molecular basis of DFNB73: mutations of BSND can cause nonsyndromic deafness or Bartter syndrome. The American Journal of Human Genetics 85(2), 273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohacek AM, Bebee TW, Tilton RK, Radens CM, McDermott-Roe C, Peart N, Kaur M, Zaykaner M, Cieply B, Musunuru K, Barash Y, Germiller JA, Krantz ID, Carstens RP, Epstein DJ, 2017. ESRP1 Mutations Cause Hearing Loss due to Defects in Alternative Splicing that Disrupt Cochlear Development. Dev Cell 43(3), 318–331 e315. 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckenstein MJ, Hu L, 1999. Antibody deposition in the stria vascularis of the MRL-Fas(lpr) mouse. Hear Res 127(1–2), 137–142. 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt AN, Plontke SK, 2005. Local inner-ear drug delivery and pharmacokinetics. Drug Discov Today 10(19), 1299–1306. 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03574-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaha NL, Almasri MM, Johns JD, Hoa M, 2021. Hearing restoration and the stria vascularis: evidence for the role of the immune system in hearing restoration. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 29(5), 373–384. 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht HF, Gacek MR, 1993. Cochlear pathology in presbycusis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 102(1 Pt 2), 1–16. 10.1177/00034894931020S101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht HF, Nadol JB Jr., 1994. Temporal bone pathology in a case of Cogan’s syndrome. Laryngoscope 104(9), 1135–1142. 10.1288/00005537-199409000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo YJ, Brown D, 2020. Experimental Animal Models for Meniere’s Disease: A Mini-Review. J Audiol Otol 24(2), 53–60. 10.7874/jao.2020.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, 2016. Pathophysiology of the cochlear intrastrial fluid-blood barrier (review). Hear Res 338, 52–63. 10.1016/j.heares.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel LG, 1975. The treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 8(2), 467–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sone M, Schachern PA, Paparella MM, Morizono N, 1999. Study of systemic lupus erythematosus in temporal bones. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 108(4), 338–344. 10.1177/000348949910800404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MH, Jung SY, Gu JW, Shim DB, 2021. Therapeutic efficacy of super-high-dose steroid therapy in patients with profound sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a comparison with conventional steroid therapy. Acta Otolaryngol 141(2), 152–157. 10.1080/00016489.2020.1842493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer SS, Schulte BA, 2005. Pathologic changes of presbycusis begin in secondary processes and spread to primary processes of strial marginal cells. Hear Res 205(1–2), 225–240. 10.1016/j.heares.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel KP, Barkway C, 1989. Another role for melanocytes: their importance for normal stria vascularis development in the mammalian inner ear. Development 107(3), 453–463. 10.1242/dev.107.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss M, 1985. A clinical pathologic study of hearing loss in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Laryngoscope 95(8), 951–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Yamasoba T, Ishibashi T, Miller JM, Kaga K, 2002. Effect of noise exposure on blood-labyrinth barrier in guinea pigs. Hear Res 164(1–2), 12–18. 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00397-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taukulis IA, Olszewski RT, Korrapati S, Fernandez KA, Boger ET, Fitzgerald TS, Morell RJ, Cunningham LL, Hoa M, 2021. Single-Cell RNA-Seq of Cisplatin-Treated Adult Stria Vascularis Identifies Cell Type-Specific Regulatory Networks and Novel Therapeutic Gene Targets. Front Mol Neurosci 14, 718241. 10.3389/fnmol.2021.718241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teissier N, Delezoide AL, Mas AE, Khung-Savatovsky S, Bessieres B, Nardelli J, Vauloup-Fellous C, Picone O, Houhou N, Oury JF, Van Den Abbeele T, Gressens P, Adle-Biassette H, 2011. Inner ear lesions in congenital cytomegalovirus infection of human fetuses. Acta Neuropathol 122(6), 763–774. 10.1007/s00401-011-0895-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toker O, Hashkes PJ, 2010. Critical appraisal of canakinumab in the treatment of adults and children with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). Biologics 4, 131–138. 10.2147/btt.s7580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay BL, Guenard F, Lamarche B, Perusse L, Vohl MC, 2019. Network Analysis of the Potential Role of DNA Methylation in the Relationship between Plasma Carotenoids and Lipid Profile. Nutrients 11(6). 10.3390/nu11061265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trune DR, 1997. Cochlear immunoglobulin in the C3H/lpr mouse model for autoimmune hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 117(5), 504–508. 10.1016/s0194-5998(97)70022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trune DR, Kempton JB, 2009. Blocking the glucocorticoid receptor with RU-486 does not prevent glucocorticoid control of autoimmune mouse hearing loss. Audiol Neurootol 14(6), 423–431. 10.1159/000241899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trune DR, Shives KD, Hausman F, Kempton JB, MacArthur CJ, Choi D, 2019. Intratympanically Delivered Steroids Impact Thousands More Inner Ear Genes Than Systemic Delivery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 128(6_suppl), 134S–138S. 10.1177/0003489419837562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuprun V, Keskin N, Schleiss MR, Schachern P, Cureoglu S, 2019. Cytomegalovirus-induced pathology in human temporal bones with congenital and acquired infection. Am J Otolaryngol 40(6), 102270. 10.1016/j.amjoto.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Fallah E, Olson ES, 2019. Adaptation of Cochlear Amplification to Low Endocochlear Potential. Biophys J 116(9), 1769–1786. 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Han L, Diao T, Jing Y, Wang L, Zheng H, Ma X, Qi J, Yu L, 2018. A comparison of systemic and local dexamethasone administration: From perilymph/cochlea concentration to cochlear distribution. Hear Res 370, 1–10. 10.1016/j.heares.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Patel R, Ren C, Taggart MG, Firpo MA, Schleiss MR, Park AH, 2013. A comparison of different murine models for cytomegalovirus-induced sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope 123(11), 2801–2806. 10.1002/lary.24090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangemann P, 1995. Comparison of ion transport mechanisms between vestibular dark cells and strial marginal cells. Hear Res 90(1–2), 149–157. 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangemann P, 2006. Supporting sensory transduction: cochlear fluid homeostasis and the endocochlear potential. J Physiol 576(Pt 1), 11–21. 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangemann P, Itza EM, Albrecht B, Wu T, Jabba SV, Maganti RJ, Ho Lee J, Everett LA, Wall SM, Royaux IE, 2004. Loss of KCNJ10 protein expression abolishes endocochlear potential and causes deafness in Pendred syndrome mouse model. BMC medicine 2(1), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WR, Byl FM, Laird N, 1980. The efficacy of steroids in the treatment of idiopathic sudden hearing loss. A double-blind clinical study. Arch Otolaryngol 106(12), 772–776. 10.1001/archotol.1980.00790360050013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witsell DL, Mulder H, Rauch S, Schulz KA, Tucci DL, 2018. Steroid Use for Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A CHEER Network Study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 159(5), 895–899. 10.1177/0194599818785142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Steigelman KA, Bonten E, Hu H, He W, Ren T, Zuo J, d’Azzo A, 2010. Vacuolization and alterations of lysosomal membrane proteins in cochlear marginal cells contribute to hearing loss in neuraminidase 1-deficient mice. Biochim Biophys Acta 1802(2), 259–268. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wycherly BJ, Thompkins JJ, Kim HJ, 2011. Early posttreatment audiometry underestimates hearing recovery after intratympanic steroid treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Int J Otolaryngol 2011, 465831. 10.1155/2011/465831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H, Chu H, Zhou X, Huang X, Cui Y, Zhou L, Chen J, Li J, Wang Y, Chen Q, Li Z, 2011. Simultaneously reduced NKCC1 and Na,K-ATPase expression in murine cochlear lateral wall contribute to conservation of endocochlear potential following a sensorineural hearing loss. Neurosci Lett 488(2), 204–209. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Tian Y, Xiong Y, Liu F, Feng Y, Chen Z, Yu D, Yin S, 2021. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals an Altered Hcy Metabolism in the Stria Vascularis of the Pendred Syndrome Mouse Model. Neural Plast 2021, 5585394. 10.1155/2021/5585394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]