Abstract

Purpose

A Lactobacillus-dominated microbiota in the endometrium was reported to be associated with favorable reproductive outcomes. We investigated in this study whether 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing analysis of the uterine microbiome improves pregnancy outcomes.

Methods

This prospective cohort study recruited a total of 195 women with recurrent implantation failure (RIF) between March 2019 and April 2021 in our fertility center. Analysis of the endometrial microbiota by 16S rRNA gene sequencing was suggested for all patients who had three or more failed embryo transfers (ETs). One hundred and thirty-one patients underwent microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing (study group) before additional transfers, while 64 patients proceeded to ET without that analysis (control group). The primary outcome was to compare the cumulative clinical pregnancy rate of two additional ETs.

Main results

An endometrial microbiota considered abnormal was detected in 30 patients (22.9%). All but one of these 30 patients received antibiotics according to the bacterial genus detected in their sample, followed by treatment with probiotics. As a result, the cumulative clinical pregnancy rate (study group: 64.5% vs. control group: 33.3%, p = 0.005) and the ongoing pregnancy rate (study group: 48.9% vs. control group: 32.8%, p = 0.028) were significantly increased in the study group compared to the control group.

Conclusion

Personalized treatment recommendations based on the microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing of the uterine microbiota can improve IVF outcomes of patients with RIF.

Trial registration

The University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trial Registry: UMIN000036050 (date of registration: March 1, 2019).

Keywords: Endometrial microbiota, Lactobacillus spp., Recurrent implantation failure, 16S ribosomal RNA, Chronic endometritis

Introduction

The human microbiome project has revealed that approximately 9% of the total human microbiome is found in the female reproductive tract [1, 2]. In addition, a recent, independent metagenomic study revealed differences in bacterial communities between the vaginal and the uterine cavities of women of reproductive age [3–5]. These results challenge the conventional dogma that the human uterus is sterile [6], and support the existence of a low-biomass, active uterine microflora. The nature of the microbiota, whether the microorganisms that contribute to uterine homeostasis are transient or endogenous, is still a matter of debate [7]. However, accumulating evidence suggests that the microbiome of the female reproductive tract may play an important role in reproductive function. Observational clinical studies have shown that certain bacteria identified via microbial culture are associated with implantation failure and spontaneous abortion [8–12]. Furthermore, patients with a non-Lactobacillus-dominated microbiota (non-LDM, defined as a microbiota composed of < 90% of Lactobacillus and > 10% of other bacteria) have been reported to have negative reproductive outcomes when compared to those patients who present a Lactobacillus-dominated microbiota (LDM, defined as a microbiota composed of > 90% of Lactobacillus species) [4].

Among the multiple factors that cause infertility, uterine factor infertility affects one in every five hundred women of reproductive age [13]. Indeed, approximately 30% of cases of infertility are caused by uterine dysfunction [14]. This organ is, therefore, essential for reproductive success and for the continuation of the human species.

By using next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology to analyze microbial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequences, the genera of the bacteria present in the endometrial microbiome can be detected, including culturable and unculturable bacteria [15]. The diagnostic tool used in this study, endometrial microbiome metagenomic analysis (EMMA), is based on the analysis of the microbial 16S rRNA gene by NGS. This technology provides information on whether the uterine microbiome is LDM or non-LDM and is free of the commonly reported bias that can arise when different bacterial groups present different abundances in the same sample. However, the clinical efficacy of EMMA is still unknown. In this study, we aimed to investigate whether the analysis of the endometrial microbiota by microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing and adherence to the treatment recommended by EMMA improve the endometrial microbial environment and positively impact the pregnancy and miscarriage rates of patients with recurrent implantation failure (RIF). Patients who requested analysis of their endometrial microbiotas also underwent hysteroscopic evaluation for chronic endometritis (CE) [16, 17] within 3 months of the endometrial biopsy (EB), and had their Nugent score [18] obtained from vaginal samples in the same day of the EB.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is a prospective cohort study carried out in our fertility center (Kamiya Ladies Clinic, Sapporo, Japan) from March 2019 to April 2021. Female patients with RIF, defined as three or more failed embryo transfer (ET) attempts, under the age of 40 and who were in the process of in vitro fertilization (IVF)-ET were enrolled. Patients undergoing IVF treatment with scheduled frozen embryo transfers (FETs) at our facility were also included. Subjects were excluded from the study if they presented with (1) intrauterine lesions (surgically adapted uterine submucosal myomas and endometrial polyps, Asherman’s syndrome, and cesarean section scarring syndrome); (2) hydrosalpinx without medical treatment; (3) allergy to antibiotics, or patients who cannot follow antibiotic treatment; (4) treatment with antibiotics within the 3 months prior to sample collection; (5) ongoing antibiotic treatment prescribed by other centers; and (6) any illness or medical condition that is unstable or could present a risk to patient safety and compromise the compliance of the study. This study was performed following the Declaration of Helsinki medical research involving human subjects and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and was approved by the ethics committee of the Institutional Review Board of Kamiya Ladies Clinic. This trial is registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) clinical trial registry in Japan (UMIN000036050). Participants were asked whether they would like their endometrial microbiotas to be analyzed by microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients.

Procedures

Sample collection

EBs in natural cycles were taken between days 15 and 25 of the menstrual cycle for patients with regular menstrual cycles. Alternatively, in the case of medicated cycles, EBs were taken between days 5 and 7 of the cycle, after the administration of progestin. Vaginal samples were taken before EBs were collected. A sterilized swab was inserted into the vagina, and a specimen of vaginal fluid was obtained by brushing the posterior vaginal fornix with a swab. A vaginal smear was prepared by spreading the sample onto a glass slide, which was then air-dried, heat-fixed, and Gram-stained. Smears were then assessed according to Nugent scoring [18] (BML, Inc., Sapporo, Japan).

To avoid bacterial contamination, the vagina was thoroughly washed with saline solution and the cervical discharge was absorbed with a dry cotton pad. EBs were collected using a Pipelle de Cornier endometrial biopsy cannula (Fuji Medical, Tokyo, Japan). EB samples were decanted into sterile tubes (Cryotube; Biosigma S.p.A., Italy) containing RNAlater solution (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LCC., MI), and each tube was vigorously shaken for approximately 4 seconds. After the tubes were stored at 4 °C for 4–72 h, they were shipped to Igenomix headquarters (Valencia, Spain) at room temperature.

Analysis of the endometrial microbiota by microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing and treatment prior to frozen embryo transfer

This study was conducted using EMMA (https://www.igenomix.com/genetic-solutions/emma-clinics/) as a tool for assessing the uterine microbiota using NGS analysis of the microbial 16S rRNA gene. A detailed EMMA protocol was previously described by Moreno and colleagues [15, 19]. EMMA comprehensively detects a variety of bacterial genera present in the uterus and determines whether the uterine microbial environment is optimal for pregnancy. This molecular method is based on detecting and quantifying the amount of bacterial DNA present in EB samples. Briefly, DNA was extracted using a QIAamp cador Pathogen Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Venlo, The Netherlands) and quantified using NanoDrop. Bacterial genomic DNA was analyzed by high-throughput sequencing using Ion Chef Instrument (model 4247) and Ion Torrent S5 XL Sequencer (model 7728) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Valencia, Spain). After samples were sequenced and analyzed, patients received personalized treatments based on the results of the microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The different results of EMMA include the following: (1) “normal,” indicating a LDM where Lactobacillus accounts for over 90% of all bacteria present in the sample, with no pathogenic bacteria detected; (2) “abnormal,” indicating an endometrium dominated by non-Lactobacillus genera whose abundances account for more than 10% of the total bacterial composition; (3) “mild dysbiosis,” indicating that the endometrium is not Lactobacillus-dominated and pathogenic bacteria are not present in significant amounts; and (4) “ultralow biomass,” indicating insignificant amounts of bacteria, an almost sterile endometrium. Thus, antibiotic and probiotic treatments were determined based on these results.

In the case of a normal result, patients continued their FET cycles without any additional treatment; in the case of an abnormal result, antibiotic followed by probiotic treatment and the analysis of a second sample after treatment were recommended before continuing ET. The recommended antibiotics were selected according to the pathogens detected in the test and the clinical characteristics of each patient. Vaginal suppositories containing Lactobacillus strains available in Asia (InVag® [Biomed, Krakow, Poland] or Lactoflora® [STADA, Portugal]) were recommended as probiotic treatment and administered after antibiotic treatment for 7–10 days. In patients with mild dysbiosis and ultralow biomass results, vaginal probiotic treatment was recommended prior to the FET cycle. These patients started their probiotic treatment after the results were known, and continued with the same treatment for 10–17 days from day 5 of their FET cycle. All patients in the control group received intravaginal probiotic treatment for 7–10 days starting on day 5 of their FET cycle.

Hysteroscopy examination

All hysteroscopies were performed by experienced physicians using a flexible hysteroscope (HVF-V; Olympus Corporation, Japan) in the follicular phase (days 7–12 of the cycle). After applying a saline solution to the vagina and cervix area, the uterine cavity was expanded via 0.9% saline injection. During hysteroscopy, both the anterior and posterior uterine walls were thoroughly examined by passing the hysteroscope in parallel to the endometrial surface to identify any surface irregularities. The following criteria were used for hysteroscopic diagnosis of CE: the presence of stromal edema, focal or diffuse hyperemia, and micropolyps of < 1 mm in size [16, 17].

Endometrial preparation and frozen embryo transfer

Endometrial preparation was performed similarly in both the control and study groups. Endometrial preparation and FET were performed in either natural or hormone replacement therapy (HRT) cycles. Natural cycles were chosen for women with regular menstrual cycles (duration of 25–35 days). The ET time for natural cycles was adjusted according to the luteinizing hormone surge of each patient. For patients with luteal insufficiency or thin endometria during the cycle, hormone treatment was implemented. Patients started oral administration of estradiol valerate (2.00 mg per day; Progynova®; Bayer, NSW, Australia) and oral progestin (Duphaston®; 20 mg of dydrogesterone) after ovulation. The protocol for HRT was done as follows: patients used dermal patches of 1.44 mg estradiol every other day (Estrana®; Hisamitsu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and took estradiol valerate (2.00 mg per day; Progynova®; Bayer, NSW, Australia) orally starting from day 2 or 3 of the cycle. Once endometrial thickness reached > 7 mm, women started with daily administration of progestin capsules (500 mg of progesterone vaginal suppositories) and oral progestin (Duphaston®; 20 mg of dydrogesterone). The transfer of day-3 embryos or blastocysts was scheduled based on embryo and endometrium synchronization. Once pregnancy was achieved, exogenous estrogen and progestin supplementation were continued until week 10 of gestation.

Outcome measurements

The main objective of this study was to determine whether the analysis of endometrial microbiota by microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing and its recommended treatment have positive impacts on the pregnancy outcomes of patients with RIF. The primary outcome was to compare the cumulative clinical pregnancy rate of two additional ETs between the study group and the control group after the suggested intervention. The secondary outcomes were the morbidity rates of endometrial microbiome disturbance in patients with RIF, cumulative ongoing pregnancy rate, live birth rate and early miscarriage rate after the suggested intervention, and adverse events associated with the EMMA tests performed. The definition of clinical pregnancy adopted in this report was the presence of gestational sacs assessed by ultrasound up to 7 weeks of gestation. Ongoing pregnancy was defined as fetal heartbeat detected until 12 weeks of gestation. The early miscarriage rate was defined as the proportion of pregnancies arrested before 12 weeks of gestation.

Sample size and statistical analysis

A previous report has shown that the clinical pregnancy rate differs by 30% between LDM and non-LDM and that approximately half of the infertile patients undergoing IVF have a less than 90% abundance of Lactobacillus species in their endometria [4]. To verify these data, a minimum sample size of 112 patients in total and 56 patients in each study group would be required with an alpha level of 0.05 and a power of 80%. Considering a dropout rate of approximately 10% due to a possible lack of compliance in treatment, follow-up, or monitoring, the total number of patients required per group would be 61.

Data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using StatFlex version 7.0 (Artech Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The results were compared between the two study groups using the chi-squared test, unpaired Student’s t test, or Mann–Whitney nonparametric U test. Groups were compared by using the Kruskal–Wallis test or Fisher’s exact probability test complemented by the Bonferroni correction. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

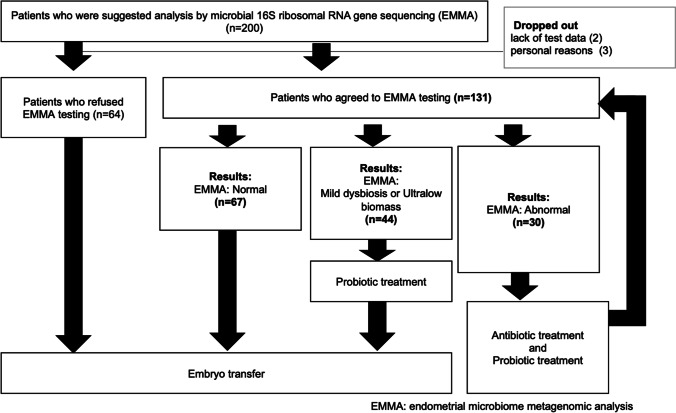

A total of 195 patients were available for analysis, two patients were excluded due to a lack of test data, and three patients dropped out of this study for personal reasons (Fig. 1). One hundred and thirty-one patients underwent analysis of endometrial microbiota by microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing before additional ETs (study group), and 64 patients with a history of RIF were unwilling to undergo that analysis, choosing to proceed to ET (control group). Patients in the control group were negative about the possibility of delaying ET due to testing and result-based treatment interventions. Table 1 shows patient characteristics. There were no differences between the two groups regarding the duration of infertility, number of previous ETs, history of miscarriages, and history of deliveries.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of research participants. A total of 195 women with recurrent implantation failure (RIF) were available for analysis from March 2019 to April 2021. RIF is defined as three or more failed embryo transfer (ET) attempts. One hundred and thirty-one patients requested analysis of endometrial microbiota by microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing before additional ETs, and the results of those tests are shown in the figure. The remaining 64 patients with a history of RIF were unwilling to undergo that analysis, choosing to proceed to ET

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Study group (tested by EMMA) | Control group (not tested by EMMA) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 131 | 64 | N/A |

| Age (years) | 36.17 ± 3.45 | 35.50 ± 3.56 | 0.210 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.92 ± 2.79 | 21.95 ± 2.84 | 0.942 |

| AMH (ng/mL) | 3.55 ± 3.12 | 3.43 ± 3.00 | 0.791 |

| Basal FSH (mIU/mL) | 8.08 ± 3.84 | 8.31 ± 3.35 | 0.692 |

| Duration of infertility (min) | 40.31 ± 30.80 | 40.51 ± 27.60 | 0.948 |

| History of delivery, n (%) | 29 (22.1) | 17 (26.6) | 0.587 |

| History of miscarriage, n (%) | 62 (47.3) | 23 (35.9) | 0.239 |

| Mean number of previous ET cycles | 4.31 ± 2.40 | 3.97 ± 1.94 | 0.438 |

| Number of patients affected by tubal factors, n (%) | 20 (15.3) | 15 (23.4) | 0.163 |

| Number of patients affected by male factor infertility, n (%) | 39 (29.8) | 19 (29.7) | 0.990 |

| Number of patients affected by endometriosis factors, n (%) | 20 (15.3) | 12 (18.8) | 0.538 |

AMH anti-Müllerian hormone, BMI body mass index, EMMA endometrial microbiome metagenomic analysis, ET embryo transfer, FSH follicle-stimulating hormone

Results of the microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing and recommended treatment based on the results

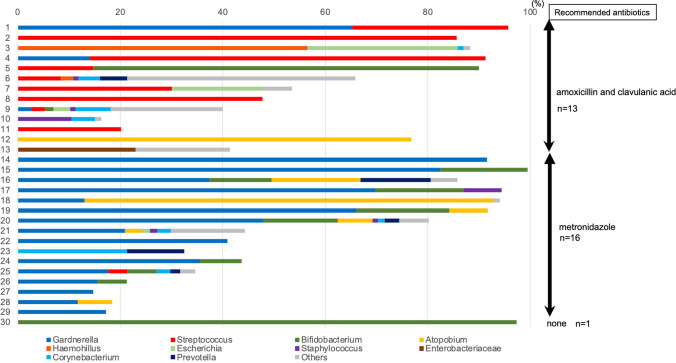

The first EMMA results for the 131 patients in the study group are shown in Table 2. The analysis revealed that 67 patients (51.1%) had a LDM and 64 patients (49.9%) had a non-LDM. Twenty-three patients (17.6%) presented a mild dysbiosis profile, and 11 patients (8.4%) presented ultralow biomass. Probiotic treatment was recommended to the patients who presented mild dysbiosis and ultralow biomass profiles. Abnormal microbiota was detected in 30 patients (22.9%), and among those patients, the abundance of the different bacterial genera was detected, excluding Lactobacillus spp., as shown in Fig. 2. Besides Lactobacillus spp., a wide variety of bacteria was identified, with the most frequently detected pathogens being Streptococcus, Gardnerella, Atopobium, and Bifidobacterium. Chlamydia and Ureaplasma, previously suggested to cause CE [20], were not detected in this cohort of patients.

Table 2.

Detailed data for first EMMA results

| First EMMA results | Abnormal hysteroscopic findings with a suspicion of CE* | Cases of live birth after EMMA and its recommended treatment, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 positive finding, n (%) | 2 or more positive findings, n (%) | ||

| Normal (n = 67, 51.1%$) | 13 cases (19.4#) | 12 cases (17.9#) | 38 cases (56.7#) |

| Abnormal (n = 30, 22.9%$) | 9 cases (30.0#) | 3 cases (10.0#) | 11 cases (36.7#) |

| Mild dysbiosis (n = 23, 17.6%$) | 8 cases (34.8#) | 2 cases (8.7#) | 10 cases (43.5#) |

| Ultralow biomass (n = 11, 8.4%$) | 5 cases (45.5#) | 1 case (9.1#) | 5 cases (45.5#) |

| Total of 131 cases | 23 cases (17.5#) | 18 cases (13.4#) | 64 cases (48.9#) |

CE chronic endometritis, EMMA endometrial microbiome metagenomic analysis

*Hysteroscopy performed within the 3 months prior to the microbial 16S RNA gene sequencing

$Percentage found out of a total of 131 cases

#Prevalence in each microbial 16S RNA gene sequencing group

Fig. 2.

The pathogenic bacteria detected and the recommended antibiotics for patients who presented an abnormal endometrial microbiota. The abundance of the different bacterial genera detected, excluding Lactobacillus spp., was observed in 30 patients with an abnormal microbiota. “Others” includes Flavobacterium, Propionibacterium, Enterococcus, Microbacterium, Rothia, Klebsiella, Micrococcus, Enterobacter, Granulicatella, Actinomyces, Fusobacterium, Gemmata, Aerococcus, Sneathia, Megasphaera, Parvimonas, Finegoldia, Morganella, and Serratia. Based on the results of the analysis of uterine microbiota, amoxicillin and clavulanic acid were recommended to 13 patients and metronidazole was recommended to 16 patients. Remaining patients received probiotic treatment

We further evaluated whether abnormal hysteroscopic findings were related to EMMA results (Table 2). Abnormal hysteroscopic findings that suggested CE [16, 17], such as micropolyps, hyperemia, and edema, were classified as one positive finding or two or more positive findings. There was no statistically significant association between EMMA results and hysteroscopic findings (p = 0.477).

Figure 2 shows the pathogenic bacteria detected and the recommended antibiotics, while Table 3 presents details of the recommended antibiotic treatments for patients who presented an abnormal endometrial microbiota. Metronidazole (500 mg twice a day) was recommended as the first line of antibiotic treatment in cases where Gardnerella was detected as the main cause for the abnormal result. For patients whose microbiota presented more than 10% of Streptococcus, a strain that has been reported to be associated with CE [20], a combination of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (500–125 mg every 8 h) was recommended as the first-line treatment. The single case where, even though the initial result was abnormal, no antibiotic treatment was recommended was case 30 in Fig. 2, where the patient presented a Bifidobacterium abundance of 97.3%. Thus, antibiotic treatment was recommended to 97% of patients who presented an abnormal result in the first test (Table 3). Patients to whom antibiotics were recommended were treated for 7–8 days. Subsequently, those patients followed probiotic treatment starting on day 5 of their menstrual cycles. Finally, patients underwent a 2nd biopsy after the treatment was completed. According to the results of the 2nd biopsy, 23 patients (75.0%) presented less than 10% of pathogens present in their endometria after the initial treatment. The remaining 7 patients (25.0%), who still showed more than 10% of pathogens present in their samples, required additional antibiotic and probiotic treatment before proceeding to the 3rd biopsy. Among these 7 patients, clindamycin was recommended to 4 patients, amoxicillin and clavulanic acid were recommended to 2 patients, and metronidazole was recommended to 1 patient (Table 3). For the patients with abnormal microbiota who received the treatments mentioned above, the median (interquartile range) percentage of Lactobacillus spp. significantly improved from 25.8% (20.2–53.6) to 90.8% (78.0–95.8) after treatment (p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Recommended antibiotic treatments for patients with abnormal results according to microbial 16S RNA gene sequencing

| First-line of antibiotic treatment recommended for patients with abnormal results (n = 30) | |

| Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (500–125 mg every 8 h for 8 days) | 13 (43.3%) |

| Metronidazole (500 mg twice a day for 7 days) | 16 (53.3%) |

| None | 1 (3.3%) |

| Second-line of antibiotic treatment recommended for patients with abnormal results (n = 7) | |

| Clindamycin (300 mg twice a day for 7 days) | 4 (57.1%) |

| Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (500–125 mg every 8 h for 8 days) | 2 (28.6%) |

| Metronidazole (500 mg twice a day for 7 days) | 1 (14.3%) |

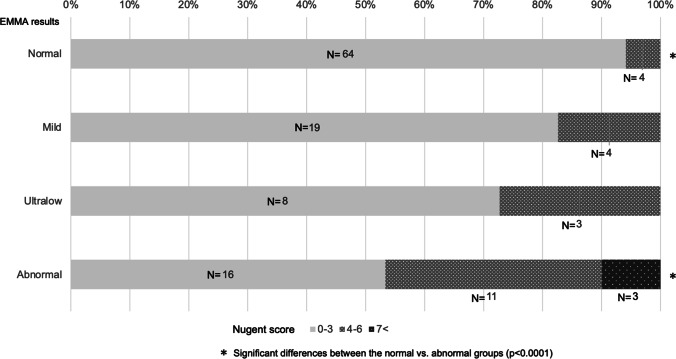

A Nugent score of 0–3 was designated as a normal vaginal flora, 4–6 as intermediate flora, and 7–10 as flora associated with bacterial vaginosis [18]. Intermediate flora may or may not contain Lactobacillus spp. and is a condition that scores between normal and bacterial vaginosis [21, 22]. Figure 3 shows the Nugent score for each EMMA result. Patients with an abnormal microbiota also had a significantly higher Nugent score than patients with a normal uterine microbiota (p < 0.001). However, in the evaluation of vaginal samples by the Nugent score, Gardnerella-like bacteria in the visual field were detected in only 7 of the 30 patients diagnosed with an abnormal microbiota result by EMMA.

Fig. 3.

Nugent score of vaginal samples on the same day of endometrial biopsy. We verified whether there was a correlation between the endometrial microbiota detected by microbial 16S rRNA sequencing analysis and the evaluation of vaginal samples by the Nugent score. A Nugent score of 0–3 was designated as normal vaginal flora, 4–6 as intermediate flora, and 7–10 as flora associated with bacterial vaginosis [18]. Comparing the Nugent score by each endometrial microbiome metagenomic analysis (EMMA) result with Fisher’s exact probability test and correcting p values with the Bonferroni method, there was a significant difference between patients with a normal uterine microbiota and patients with an abnormal microbiota (p < 0.0001)

In terms of adverse events observed in the study, there were no patients who developed serious complications such as uterine perforation. Although 3 patients experienced vagal reflex and hypotension due to pain, the symptoms improved after 5 min of rest. One patient had amoxicillin and clavulanic acid–associated skin rash, which improved with anti-allergic medication (fexofenadine hydrochloride), administered for 7 days. There were no cases of serious complications such as anaphylactic shock resulting from the administration of antibiotic agents.

Pregnancy outcomes

Table 4 shows the pregnancy outcomes of the two patient groups after the suggested analysis of microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing and treatment based on the analysis results. Patients in the study group resumed their FET cycles after completing the treatment suggested in the report of the microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis. When comparing pregnancy outcomes, there was no difference between the two groups regarding the number of transferred embryos and the type of cycle, whether it was natural or HRT. The study group presented significantly more favorable results than the control group in terms of clinical pregnancy rate (42.0% and 12.5%, p < 0.001), ongoing pregnancy rate, and live birth rate (33.6% and 12.5%, p < 0.001) after the first ET. In contrast, there were no significant differences in early miscarriage rates (20.0% and 25.0%, p = 0.665) between the two groups. When comparing the cumulative pregnancy rates after two additional FET cycles, the study group also had significantly higher clinical pregnancy (64.5% and 33.3%, p = 0.005), ongoing pregnancy (48.9% and 32.8%, p = 0.028), and live birth (48.9% and 31.2%, p = 0.020) rates. After treatments that were based on the results of the microbial 16S RNA gene sequencing analysis, live birth outcomes were comparable among the 4 microbiota profile groups (p = 0.280), indicating that, over a short period of time, patients with non-LDMs requiring therapeutic intervention achieved live birth rates that were equivalent to those of patients with LDM (Table 2).

Table 4.

Pregnancy outcomes after frozen embryo transfer

| Study group (tested by EMMA) | Control group (not tested by EMMA) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transferred embryos (n) | 1.36 ± 0.54 | 1.34 ± 0.48 | 0.844 |

| Endometrial preparation for embryo transfer | |||

| Hormone cycle | 127 (96.9%) | 63 (98.4%) | 1.000 |

| Natural cycle | 4 (3.1%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| Results after the first FET following the proposed interventions | |||

| hCG positive rate | 62.6% (82/131) | 14.1% (9/64) | < 0.001* |

| Clinical pregnancy rate | 42.0% (55/131) | 12.5% (8/64) | < 0.001* |

| Ongoing pregnancy rate | 33.6% (44/131) | 9.4% (6/64) | < 0.001* |

| Early miscarriage rate | 20.0% (11/55) | 25.0% (2/8) | 0.665 |

| Live birth rate | 33.6% (44/131) | 9.4% (6/64) | < 0.001* |

| Results after 2 cumulative FET cycles | |||

| Implantation rate | 48.3% (87/180) | 33.7% (29/86) | 0.025* |

| Clinical pregnancy rate | 64.5% (79/131) | 33.3% (25/64) | 0.005* |

| Ongoing pregnant rate | 48.9% (64/131) | 32.8% (21/64) | 0.028* |

| Multiple pregnancy rate | 9.4% (6/64) | 5.0% (1/20) | 0.680 |

| Biochemical pregnancy rate | 21.4% (28/131) | 10.9% (7/64) | 0.111 |

| Early miscarriage rate | 13.0% (15/79) | 11.8% (4/25) | 0.498 |

| Stillbirth rate | 0% (0/64) | 4.8% (1/21) | 0.247 |

| Live birth rate | 48.9% (64/131) | 31.2% (20/64) | 0.020* |

| Weeks of gestation for single births | 38.8 ± 1.71 | 37.6 ± 3.42 | 0.044* |

| Single birth weight (g) | 2995.8 ± 380.7 | 2816.8 ± 688.5 | 0.157 |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD unless otherwise specified

EMMA endometrial microbiome metagenomic analysis, FET frozen embryo transfer, hCG human chorionic gonadotropin

*p < 0.05

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this prospective cohort study is the first report to evaluate whether optimizing the endometrial microbiome through microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing positively contributes to the pregnancy outcomes of patients with RIF. At least 25% of the patients tested presented with dysbiosis of the endometrial microbiota and received antibiotics to eliminate pathogens and optimize uterine environment. Patients who previously suffered from RIF showed significantly improved implantation, ongoing pregnancy, and live birth rates after the first ET following endometrial microbiota analysis through microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing and treatment. Those patients with a uterine environment considered healthy (LDM) proceeded to ET, and only those patients requiring intervention were given appropriate treatment, with post-treatment ETs resulting in significantly increased pregnancy outcomes compared to the control group. This study suggests that the analysis of endometrial microbiota by microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing and appropriate treatment may affect the reproductive outcomes of 25% of RIF patients. Retrospective studies conducted by Cicinelli and collaborators [23] have shown that patients with hysteroscopic CE findings have better pregnancy outcomes after antibiotic treatment and, in several studies, the recommended treatment was 14 days of doxycycline or ciprofloxacin administration [24–26]. In the present study, 90% of the recommended antibiotics were not broad-spectrum, and the percentage of endometrial Lactobacillus spp. improved after 7–8 days of antibiotic treatment followed by application of probiotics. Prolonged administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics is discouraged because of the increased risk of developing multidrug-resistant bacteria and of decreasing the abundance of beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus spp. For this reason, patients should undergo reliable tests with high reproducibility and appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Classic diagnostic techniques for CE are histology, hysteroscopy, and microbial culture [16, 20, 27]. However, histology and hysteroscopy are highly subjective and unspecific and rely on individual observations of pathologists or endoscopic surgeons [27]. Because of contamination risk, low abundances of certain bacteria, and the presence of unculturable bacteria in the endometrium, it has been difficult to diagnose CE using microbial culture. In this regard, as Moreno et al. [4] reported, microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing unravels the bacterial community composition at the genus level, identifying both culturable and unculturable bacteria without bias. EMMA, the diagnostic tool we used in this study, also addresses the risk of contamination [19]. In our study, when hysteroscopic findings were compared among the patients who underwent microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing, the incidence of abnormal findings by hysteroscopy was similar in both patients with LDM and patients with an abnormal microbiota. The percentage of non-LDM in the current study was approximately 50%, but antibiotics were recommended to achieve a LDM in only 23% of patients tested. By examining the uterine microbiota and administering antibiotics only when necessary, based on NGS technology results, we were able to avoid the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

According to previous reports, non-LDMs were associated with poor pregnancy outcomes when compared to LDMs [4]. It has also been suggested that a non-LDM may trigger an inflammatory response in the endometrium which affects the success of embryo implantation, as inflammatory mediators are tightly regulated during the adhesion of the blastocyst to the epithelial endometrial wall [28]. Liu et al. [29] also reported that Lactobacillus was more abundant in the non-CE microbiota, and that Dialister, Bifidobacterium, Prevotella, Gardnerella, and Anaerococcus were more abundant in the endometrial microbiota of women with CE than in those without CE. Although the mechanisms underlying such correlations are unknown, continued non-LDM status may lead to CE. In addition, this study suggests that interventions to promote a LDM in the uterus may be a key to achieving an early pregnancy. Recently, several mechanisms have been proposed as potential causes of reproductive failure in CE pathophysiological models where an altered endometrial microbiota produces endometrial inflammation and a series of secondary effects, including abnormal cytokine and leukocyte expression, abnormal uterine contractility, impaired immune tolerance to the embryo, altered vascular permeability, defective decidualization, and trophoblast invasion [30, 31].

In a healthy human vagina, the bacterial flora is composed mainly of lactic acid bacteria of the Lactobacillus genus [5, 32–34]. In the present study, the vaginal Nugent score was associated with the endometrial microbiota as reported by the microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis. However, the Gardnerella morphotype, which was most frequently detected in patients with a non-LDM, was found in a limited number of cases when the Nugent score was used to evaluate vaginal samples. Previous reports also demonstrated that the bacterial concordance between vaginal and endometrial cultures is low, ranging from 32.6 to 50.2%, and that the bacterial flora of these two sites does not necessarily coincide [4, 5, 35]. In cases when the intrauterine environment cannot be assessed by vaginal microbial culture alone, the detection of abnormal microbiota by NGS is the most effective and reliable tool.

Limitations

Firstly, the lack of randomization is a limitation of this study. Although it has a prospective design, this could not completely control for possible confounding factors. Therefore, a randomized controlled study should be conducted to properly prove the validity of endometrial microbiota analysis by microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Secondly, preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) was not performed in the study because this test is currently restricted by the Society of Obstetrics & Gynecology of Japan. The pregnancy rate is expected to improve if good-quality embryos are selected by PGT-A and transferred once the intrauterine environment is optimized by endometrial microbiota analysis via microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm the pregnancy rates following ETs with embryos selected by PGT-A, and with or without analysis of the endometrial microbiota by microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

Conclusion

This study suggests that an optimal uterine microbiota is a key to improve the pregnancy outcomes in patients with RIF, even if the patients were not diagnosed with CE. Personalized treatment recommendations based on microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing can help achieve an optimal intrauterine environment and improve IVF outcomes in RIF cases. Moreover, by using microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing, broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment can be avoided and the physical and economic burdens on patients can be reduced.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Viviane Casaroli MSc, for her excellent help with English proofreading. We also wish to thank Ms. Yuko Takeda for data collection, and Ms. Nami Hirayama and Ms. Masae Shibasaki for the statistical analysis (both are clinical staff in the Kamiya Ladies Clinic). Finally, we would like to extend our gratitude to Professor Daiki Iwami Ph.D., from Jichi Medical University, for proofreading the manuscript.

Author contribution

NI: protocol development, data analysis, data collection, and manuscript writing. MK, NO, TY, EW, MM, and OM: data collection. HK: data collection, protocol development, and supervision.

Data availability

The results of EMMA and datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Here is the link to the data depository: https://center6.umin.ac.jp/cgi-bin/icdr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000041006.

Declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Kamiya Ladies Clinic and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or similar ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI. The human microbiome project. Nature. 2007;449:804–10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17943116/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Peterson J, Garges S, Giovanni M, McInnes P, Wang L, Schloss JA, et al. The NIH Human Microbiome Project. Genome Res. 2009;19:2317–23. doi: 10.1101/gr.096651.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell CM, Haick A, Nkwopara E, Garcia R, Rendi M, Agnew K, et al. Colonization of the upper genital tract by vaginal bacterial species in nonpregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 212:611.e1–611.e9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25524398/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Moreno I, Codoñer FM, Vilella F, Valbuena D, Martinez-Blanch JF, Jimenez-Almazán J, et al. Evidence that the endometrial microbiota has an effect on implantation success or failure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016; 215:684–703. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27717732. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Chen C, Song X, Wei W, Zhong H, Dai J, Lan Z, et al. The microbiota continuum along the female reproductive tract and its relation to uterine-related diseases. Nat Commun. 2017;8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29042534/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Romero R, Espinoza J, Mazor M. Can endometrial infection/inflammation explain implantation failure, spontaneous abortion, and preterm birth after in vitro fertilization? Fertil Steril. 2004; 82:799–804. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15482749/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Baker JM, Chase DM, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Uterine microbiota: residents, tourists, or invaders? Front Immunol. 2018;9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29552006/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Egbase PE, Al-Sharhan M, Al-Othman S, Al-Mutawa M, Udo EE, Grudzinskas JG. Incidence of microbial growth from the tip of the embryo transfer catheter after embryo transfer in relation to clinical pregnancy rate following in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Hum Reprod. 1996; 11:1687–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8921117/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Egbase P, Udo E, Al-Sharhan M, Grudzinskas J. Prophylactic antibiotics and endocervical microbial inoculation of the endometrium at embryo transfer. Lancet. 1999;354:651–2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10466674/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Salim R, Ben-Shlomo I, Colodner R, Keness Y, Shalev E. Bacterial colonization of the uterine cervix and success rate in assisted reproduction: results of a prospective survey. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:337–40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11821274/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Fanchin R, Harmas A, Benaoudia F, Lundkvist U, Olivennes F, Frydman R. Microbial flora of the cervix assessed at the time of embryo transfer adversely affects in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril Fertil Steril. 1998;70:866–70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9806568/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Selman H, Mariani M, Barnocchi N, Mencacci A, Bistoni F, Arena S, et al. Examination of bacterial contamination at the time of embryo transfer, and its impact on the IVF/pregnancy outcome. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2007; 24:395–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17636439/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Flyckt R, Davis A, Farrell R, Zimberg S, Tzakis A, Falcone T. Uterine transplantation: surgical innovation in the treatment of uterine factor infertility. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018; 40:86–93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28821413/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Simón C, Giudice LC. The endometrial factor: a reproductive precision medicine approach [Internet]. Endometrial Factor A Reprod. Precis. Med. Approach. 2017. https://www.routledge.com/The-Endometrial-Factor-A-Reproductive-Precision-Medicine-Approach/Simon-Giudice/p/book/9781498740395.

- 15.Moreno I, Cicinelli E, Garcia-Grau I, Gonzalez-Monfort M, Bau D, Vilella F, et al. The diagnosis of chronic endometritis in infertile asymptomatic women: a comparative study of histology, microbial cultures, hysteroscopy, and molecular microbiology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:602.e1–602.e16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29477653/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Polisseni F, Bambirra EA, Camargos AF. Detection of chronic endometritis by diagnostic hysteroscopy in asymptomatic infertile patients. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2003; 55:205–10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12904693/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Cicinelli E, Resta L, Nicoletti R, Tartagni M, Marinaccio M, Bulletti C, et al. Detection of chronic endometritis at fluid hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005; 12:514–8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16337579/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:297–301. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1706728/. Accessed 31 Aug 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Moreno I, Garcia-Grau I, Perez-Villaroya D, Gonzalez-Monfort M, Bahçeci M, Barrionuevo MJ, et al. Endometrial microbiota composition is associated with reproductive outcome in infertile patients. Microbiome. 2022;10:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01184-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cicinelli E, De Ziegler D, Nicoletti R, Colafiglio G, Saliani N, Resta L, et al. Chronic endometritis: correlation among hysteroscopic, histologic, and bacteriologic findings in a prospective trial with 2190 consecutive office hysteroscopies. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:677–84. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17531993/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Honda H, Yokoyama T, Akimoto Y, Tanimoto H, Teramoto M, Teramoto H. The frequent shift to intermediate flora in preterm delivery cases after abnormal vaginal flora screening. Sci Rep. 2014; 4: 4799. www.nature.com/scientificreports [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Farr A, Kiss H, Hagmann M, Machal S, Holzer I, Kueronya V, et al. Role of Lactobacillus species in the intermediate vaginal flora in early pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One; 2015;10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26658473/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Cicinelli E, Matteo M, Tinelli T, Lepera A, Alfonso R, Indraccolo U, et al. Prevalence of chronic endometritis in repeated unexplained implantation failure and the IVF success rate after antibiotic therapy. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:323–30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25385744/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Kitaya K, Matsubayashi H, Takaya Y, Nishiyama R, Yamaguchi K, Takeuchi T, et al. Live birth rate following oral antibiotic treatment for chronic endometritis in infertile women with repeated implantation failure. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2017;78. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28608596/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.McQueen DB, Perfetto CO, Hazard FK, Lathi RB. Pregnancy outcomes in women with chronic endometritis and recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:927–31. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26207958/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Johnston-MacAnanny EB, Hartnett J, Engmann LL, Nulsen JC, Sanders MM, Benadiva CA. Chronic endometritis is a frequent finding in women with recurrent implantation failure after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:437–41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19217098/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Kitaya K, Matsubayashi H, Yamaguchi K, Nishiyama R, Takaya Y, Ishikawa T, et al. Chronic endometritis: potential cause of infertility and obstetric and neonatal complications. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2016;75:13–22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26478517/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Dominguez F, Gadea B, Mercader A, Esteban FJ, Pellicer A, Simón C. Embryologic outcome and secretome profile of implanted blastocysts obtained after coculture in human endometrial epithelial cells versus the sequential system. Fertil Steril. 2010;93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19062008/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Liu Y, Ko EYL, Wong KKW, Chen X, Cheung WC, Law TSM, et al. Endometrial microbiota in infertile women with and without chronic endometritis as diagnosed using a quantitative and reference range-based method. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:707–717.e1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31327470/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Buzzaccarini G, Vitagliano A, Andrisani A, Santarsiero CM, Cicinelli R, Nardelli C, et al. Chronic endometritis and altered embryo implantation: a unified pathophysiological theory from a literature systematic review. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:2897–911. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33025403/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Benner M, Ferwerda G, Joosten I, Van Der Molen RG. How uterine microbiota might be responsible for a receptive, fertile endometrium. Hum Reprod Update. 2018;24:393–415. https://academic.oup.com/humupd/article/24/4/393/4971542 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Antonio MAD, Meyn LA, Murray PJ, Busse B, Hillier SL. Vaginal colonization by probiotic Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05 is decreased by sexual activity and endogenous Lactobacilli. J Infect Dis. 2009; 199:1506–13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19331578/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SSK, McCulle SL, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; 108:4680–7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20534435/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Petrova MI, Lievens E, Malik S, Imholz N, Lebeer S. Lactobacillus species as biomarkers and agents that can promote various aspects of vaginal health. Front Physiol. 2015;6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25859220/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Wee BA, Thomas M, Sweeney EL, Frentiu FD, Samios M, Ravel J, et al. A retrospective pilot study to determine whether the reproductive tract microbiota differs between women with a history of infertility and fertile women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018; 58:341–8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29280134/ [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The results of EMMA and datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Here is the link to the data depository: https://center6.umin.ac.jp/cgi-bin/icdr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000041006.