Abstract

Purpose

The fragile X premutation occurs when there are 55–200 CGG repeats in the 5′ UTR of the FMR1 gene. An estimated 1 in 148 women carry a premutation, with 20–30% of these individuals at risk for fragile X–associated primary ovarian insufficiency (FXPOI). Diagnostic experiences of FXPOI have not previously been included in the literature, limiting insight on experiences surrounding the diagnosis. This study identifies barriers and facilitators to receiving a FXPOI diagnosis and follow-up care, which can inform care and possibly improve quality of life.

Methods

We conducted qualitative interviews with 24 women with FXPOI exploring how FMR1 screening, physician education, and supportive care impacted their experience. Three subgroups were compared: women diagnosed through family history who have biological children, women diagnosed through family history who do not have biological children, and women diagnosed through symptoms of POI.

Results

Themes from interviews included hopes for broader clinician awareness of FXPOI, clear guidelines for clinical treatment, and proper fertility workups to expand reproductive options prior to POI onset. Participants also spoke of difficulty finding centralized sources of care.

Conclusions

Our results indicate a lack of optimal care of women with a premutation particularly with respect to FMR1 screening for molecular diagnosis, short- and long-term centralized treatment, and clinical and emotional support. The creation of a “FXPOI health navigator” could serve as a centralized resource for the premutation patient population, assisting in connection to optimal treatment and appropriate referrals, including genetic counseling, mental health resources, advocacy organizations, and better-informed physicians.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10815-022-02671-1.

Keywords: FXPOI, POF, Infertility, Menopause, Premutation, Fragile X

Introduction

Fragile X syndrome (FXS), the most common form of inherited intellectual disability, is caused by 200 or more CGG repeats in the 5′ untranslated region of the FMR1 gene [1]. The fragile X premutation, characterized by 55–199 CGG repeats, occurs in an estimated 1 in 148 women, impacting over one million women in the United States [2–4]. The majority of women learn they are premutation carriers due to a family history of FXS, but an estimated 15% of women are diagnosed due to symptoms of fragile X–associated primary ovarian insufficiency (FXPOI) [5]. Previous studies have reported that knowledge of premutation carrier status affects reproductive decisions [5, 6], because of the risk of having a child with FXS and the high risk for infertility associated with POI [7]. Women with premutation or POI symptoms should receive reproductive counseling at childbearing age, including a fertility workup, hormone panel, genetic counseling, and education on reproductive options including natural conception, assisted reproductive technologies, and adoption. [8].

Women with FXPOI display loss of ovarian function prior to age 40 with missed or irregular menses, irregular ovulation, and an altered hormone profile [5, 9]. Among women with the premutation, an estimated 20–30% will experience cessation of menses prior to age 40, compared to 1% of the general population [7, 10–12]. The highest risk is for those with 80–100 CGG repeats, and women with the premutation undergo menopause 5 years earlier on average than noncarriers [9, 13, 14]. Guidelines from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG), National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC), and American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) recommend that all women with unexplained ovarian insufficiency or elevated FSH levels before age 40 have FMR1 testing, regardless of their family history [11, 15, 16].

Women who are younger at the time of POI onset are likely to experience a longer diagnostic odyssey [5]. This delay may be due to the healthcare provider’s lack of knowledge surrounding FXPOI along with rarity of the condition, requiring increased self-advocacy from patients [17, 18]. Upon receiving a premutation diagnosis, women have reported needing to provide educational FXPOI materials to their doctors [5]. Increased clinician awareness of FXPOI is essential, as timely diagnosis and follow-up care for FXPOI mitigate the risks of medical comorbidities and greatly improve overall quality of life [19, 20].

Women with the premutation are at risk for other medical comorbidities, including fragile X–associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS), osteoporosis, thyroid disorders, neuropathy, fibromyalgia, and autoimmune diseases [7, 19, 21, 22]. They are also predisposed to fragile X–associated neuropsychiatric disorders (FXAND), which can include anxiety, depression, headaches, and sleep problems [23–26].

The purpose of the present study is to better understand the experiences of women with FXPOI before, during, and after a premutation diagnosis. Participants were divided into subgroups based on how they received their diagnosis (family history versus symptoms of POI) to explore how carrier status and POI influence reproductive decisions, family dynamics, emotional health, and overall care. Understanding women’s experiences with genetic testing, physician education, and other factors during diagnosis will aid healthcare providers in improving care for individuals with FXPOI, thus improving patient quality of life.

Methods

Participants were recruited from the Emory Fragile X Center registry for FXS-related research, which includes over 1000 women who carry a premutation. The Fragile X Center recruits from many national sources, including the Emory Fragile X Clinic, Emory Genetics Clinic, Fragile X Clinic and Research Consortium, Fragile X family conferences, fragile X listservs, parent support groups, and word of mouth. Women were selected based on age of POI onset and a verified premutation. Women were selectively sampled based on three criteria: (1) diagnosis ascertained through POI (“POI symptoms”); (2) ascertained through a family history of FXS with genetically related children (“FHx with children”); and (3) ascertained through a family history without genetically related children (“FHx without children”). The interview guide was developed to explore reproductive health history, experiences leading to genetic testing, participant receipt of premutation result disclosure and follow-up care/support provided, emotional health changes, and advice from the study participants (included in Supplementary information). It was reviewed by a genetic counselor, health psychologist, and primary research investigator. Eligible participants were emailed the link to an online consent form in REDCap along with a flyer including information about the study. Participants were then scheduled for a phone call to complete the consent discussion and an in-depth interview. All interviews were conducted by a genetic counseling Master’s-level graduate student (BP). Individuals who completed the interview were compensated with a $20 Amazon gift card. The interviews ranged from 20 to 80 min, were audio-recorded, and were sent to a HIPPA compliant third-party transcription service. Verbatim transcriptions were independently coded using MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2020, by two coders (BP and EA) using deductive codes from literature review and inductive codes arising from the data. Any discrepancies in coding were resolved through discussion after each interview. Inter-rater reliability (IRR) was calculated using Mezzich’s modified kappa formula (IRR = 0.78, strong agreement). This study was reviewed and approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board (IRB00045808).

Results

Participants

A total of 38 individuals with a diagnosis of FXPOI were emailed, and 24 agreed (63.2%) to participate in a qualitative phone interview (n = 8 POI symptoms, n = 8 FHx with children, and n = 8 FHx without children) (Table 1). Participants received their premutation diagnosis between 0 and 41 years ago, with an average of 17 years prior to the study.

Table 1.

Demographic information of study participants

| Total n = 24 | FHx with children n = 8 |

FHx without children n = 8 |

POI symptoms n = 8 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age (years) = mean ± SD |

49 ± 12.4 | 56.8 ± 10.4 | 50.4 ± 12.9 | 38.8 ± 7.9 | |

|

Age at PM dx (years) = mean ± SD |

32 ± 8.7 | 31.4 ± 5.9 | 34.9 ± 12.7 | 29.9 ± 6.2 | |

|

Age at POI dx (years) = mean ± SD |

29.3 ± 5.4 | 29.9 ± 4.1 | 28.1 ± 6.6 | 29.9 ± 6.2 | |

| # Children (biological) | 0 children | 16 | 0 | 8 | 8 |

| 1 child | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 children | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 children | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 children | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| # Nonbiological children (e.g., egg donor, adoption) | 0 children | 13 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| 1 child | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2 children | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 | |

| 3 children | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Infertility | None | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Pregnancy achieved post POI dx | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| No pregnancy with conception attempts | 12 | 0 | 6 | 6 | |

| No conception attempts due to POI/PM dx | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Successful ART | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Occupation | Employed | 16 | 2 | 7 | 7 |

| Homemaker | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Retired | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | |

| Educational degree | Associates | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Bachelors | 8 | 5 | 3 | 0 | |

| Graduate | 14 | 2 | 4 | 8 | |

| Ethnicity | Southeast Asian | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| White | 23 | 8 | 7 | 8 |

Abbreviations: FHx, family history; POI, primary ovarian insufficiency; SD, standard deviation; PM, premutation; dx, diagnosis; ART, assisted reproductive technology

Six primary themes emerged during data analysis and will be discussed in turn, along with relevant subthemes. These primary themes include experiences during pretesting; experiences during results disclosure and clinical follow-up; educating oneself and others; reproductive decisions; emotional health and relationships; and advice for both medical professionals and other women with FXPOI.

Experiences during pretesting

Motivation for testing

When family history was the motivation for seeking diagnosis, some participants experienced positive family reactions to testing (e.g., family participation in research leading to cascade testing), while other participants reported strained relationships concerning testing.

“My cousin was very…forceful about that it was in the family and that everybody needed to be tested and really alienated herself…”—Interviewee #20, FHx with children

However, for individuals who were eventually diagnosed through family history and were experiencing symptoms of POI, FMR1 testing was often not considered initially, even when relevant indications of POI were present.

“I mean, my periods were very erratic…one doctor told me I was premenopausal…they never did any Fragile X testing at that point. So, we finally got pregnant and, um, my son was born…when we realized he was havin’ developmental delays…the neurologist did some testing, and she actually was the one who put the Fragile X test in there.”—Interviewee #8, FHx with children

“So that’s when I reached out to my doctor, and said, “Listen, like, something’s going on.” I was having hot flashes and night sweats…And my sister had already—she was pregnant at the time. And she had found out she was a fragile X carrier through…pregnancy blood work…So I started, like, researching, and I—that’s when, um, my doctor started doing blood work, and they figured it out.”—Interviewee #14, FHx without children

The third subgroup of women was diagnosed solely due to POI symptoms. These women had a younger average age at premutation diagnosis; were also more recently diagnosed, more frequently presented to reproductive endocrinologists (REI) due to irregular periods or other features of POI, and more commonly had advocate for themselves within the healthcare system; and often required several different clinician visits before their POI symptoms were seriously considered.

“I had stopped getting regular periods…between 28 and 29. And I—every year for my annual exam would say, you know, “I think something’s weird.” Like, I’m advocating for myself. And…she would just basically say, “That’s normal if you’ve been on birth control for 15 years plus…And, um, we could test your AMH, but I highly —don’t recommend it unless you’re looking to save or freeze your eggs immediately.”—Interviewee #24, POI symptoms

“So I was having a lot of hot flashes, and it took probably four gynecologists, and essentially the first three basically said, “You’re too young…we’ve never heard of somebody your age having hot flashes. This makes no sense.” And all three of those doctors prescribed me anxiety medications, and then I went to a fourth gynecologist, ob-gyn, and she, essentially, said…I just read about this thing. I can test you for it. It sounds pretty similar to what you’re describing…and that ended up being the premutation issue, and premature ovarian failure”—Interviewee #11, POI symptoms

Barriers to testing

Almost a third of participants reported difficulty receiving a POI diagnosis, which may have delayed FMR1 testing. Other reported barriers included socioeconomic factors, insurance difficulties, family not disclosing a known history of FXS or premutation, and personal hesitations of either blood draw or the “label” of a premutation diagnosis.

“[Doctor] can work with women who are premenopausal or in…menopause and understands Fragile X but, honestly, I don’t think my health insurance covers it and I don’t have a lot of money to do that. So, that doesn’t feel accessible to go.”—Interviewee #12, FHx without children

Genetic testing timeline

Participants were asked how long it took from when they became aware of a positive family history or began experiencing symptoms of POI, to receive a premutation diagnosis. Quicker times (< 1 year) were discussed with family support, research centers, POI recognition by REIs, or having a child with FXS.

“I look back now, I have friends that’ve had infertility, and I feel somewhat thankful that I didn’t go through the process of infertility treatments and month after month of being given hope and – lost…Instead, I got my news, and it was horrifically shocking, and then that was it, you know?”—Interviewee #13, POI symptoms

Longer diagnostic times (> 1 year) were discussed with multiple visits to different OBGYNs to pursue etiology of POI, personal hesitations, use of birth control pills, and lack of disclosure from family.

“I got a bunch of other random diagnoses that weren’t accurate in the meantime, right? So, just like a bunch of other doctors who didn’t even consider menopause as an option.”—Interviewee #3, POI symptoms

Experiences during result disclosure and clinical follow-up

Medical providers

Study participants encountered a broad range of medical providers prior to and after their diagnosis, including pediatricians, geneticists/genetic counselors, REIs, OBGYNs, family practitioners, nurses, physician assistants, and a naturopathic doctor. Participants commonly reported difficulty finding a point of care in relation to FXPOI.

“I also asked her [genetic counselor],“Okay, well, what is your role in my ongoing care?” And she was like, “Oh, genetics is not involved in your day-to-day care. You should really go back to your OB-GYN…,” who at that point, had said…they weren’t gonna be responsible for my care, but that endocrinology was. And the endocrinology said that genetics was, and then genetics sent me back to OB-GYN…”—Interviewee #23, POI symptoms

Perception of medical professional knowledge level

Genetics providers were most positively perceived when complete information about the premutation and POI were provided: short-term and long-term health impacts, risk analysis for other family members, reproductive risks, and support for sharing the diagnosis with other family members. Individuals who had done extensive research prior to the genetics visit were less likely to find the genetics appointment of value.

“I feel like I also had to do a lotta my own research…I think it was really more focused on the diagnosis, the number of repeats that I had, and, like, fertility issues and…my chances of ever conceiving and the chance that the child would…be affected…”—Interviewee #21, FHx without children

REIs were frequently the providers who coordinated treatment of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or ordered FMR1 gene testing, and they were more frequently seen by women from the POI symptoms or FHx without children groups. REIs were viewed most positively when aiding in search of the POI etiology.

“They just want to get pregnant, but for me, I was like, you know, what-what is causing this? Like, this doesn’t seem normal, right? Um, so the reproductive endocrinologist, they don’t really care. They just want you to get pregnant.”—Interviewee #3, POI symptoms

“I probably came in with more questions than most just given my l-level of research. And she [REI] was not only empathetic but, um, was-was—I mean, she’s a leader in her field. So I was incredibly lucky.”—Interviewee #24, POI symptoms

OBGYNs are often the first providers to offer workup for POI and order hormone panels. Intake forms with in-depth history questions contributed to a more positive perception of the clinic along with receptiveness to educational materials from the patient.

“So I go to this clinic in [city], Dr.[name] is amazing, and from the very first moment I walked into his office and filled out the history form—I think part of it was that online research. His history form was amazing…I’m like, “…this is so comprehensive. This is exactly what every gynecologist should have.”—Interviewee #18, POI symptoms

Factors negatively influencing perception of OBGYN knowledge levels include dismissal of POI symptoms, misdiagnoses, lack of hormone testing, and difficulty receiving recommended care such as DEXA scans or HRT.

“I got the-the fragile X premutation carrier results first before I had any symptoms. Um, and then I had asked my gynecologist, like, based on that information if I should, like, freeze eggs or do anything else. And they kinda were like, no, like, when you go to get pregnant, we’ll-we’ll just figure it out.”—Interviewee #14, FHx without children

“Even now, today, I have found GYNs have no idea what to do as it relates to POI or Fragile X or—like, every time I go to the GYN, even today…at age 50, I’m saying, “Should I have a Dexa scan? Should we talk about HRT?…” And the answer is, “No, you’re only 50.” “…Because I understand that as a carrier, you know, there are some differences. No, is the answer”—Interviewee #19, FHx with children

Empathy

Factors negatively impacting study participant’s perception of provider empathy included lack of knowledge regarding FXPOI, insufficient support, the need to provide their own educational materials to the clinician, and the way they received the diagnosis of POI. Individuals diagnosed due to POI symptoms were more likely to report the medical professional was not empathetic.

“But every year you go in your—for your annual, and you’ll be sitting there with the nurse or the LPN or whoever’s taking the notes, and they would say, “When was your last period?” And I would just wanna scream, “You have EMR. Look it up in your (%&$!) charts.”—Interviewee #18, POI symptoms

“Yeah, I don’t think you’re ever gonna have a biological child. You’re…in menopause”…and I was like, “Well, w-why is this happening? I’m 33.” Um, and he was like, “Well, it just happens, and this—you’re in menopause”…and then he wanted me to give him CD suggestions for his wife, to add to her CD collection, and I just remember thinking, “You have just told me, like, this life-changing diagnosis, and all you care about is your (%&$!) CD collection.”—Interviewee #4, FHx without children

Favorable factors for empathy included an informed clinician, REI, offering support and resources, research groups, and offering to assist with insurance approval for treatments.

“Um, but the genetic counselor called me and first went over like, “Here’s your premutation. This is what the premutation means in terms of the condition. This is what the primary ovarian insufficiency means…this is what Fragile X is. This is what it means to you health-wise in the short term, in the long term. Um, this is what it means in terms of—um, for your family”…and I was like, “Wait a minute. My sister’s pregnant”…I mean, she stayed on the phone for a long time helping talk me through it and, like, giving me advice on how to talk to my sister and what I needed to say and how to prepare them and what to advise them.”—Interviewee #18, POI symptoms

“Back then, and then years later, when we found out the results—the only-the only people who seemed concerned are at [university]. Well, because it showed a caring and concern for those people.”—Interviewee #22, FHx without children

Referrals experienced

Upon diagnosis, participants were often referred to FXS and associated conditions research centers. Research participation was generally viewed more positively than clinical experiences for reasons including in-depth education, personable care, affordability, support, positive focus, and time allotted.

“I think the studies I’ve participated in…everybody that’s been doing it has been fantastic, um, always very open to providing information, explaining things—um, you know, answering questions.”—Interviewee #10, POI symptoms

Other types of referrals included genetic specialists, advocacy organizations, and mental health resources.

[REI] “he was like, “You have this condition.” He sat down and talked to me, and he shared. He’s like, “But I want you to meet with a genetic counselor. The genetic counselor is gonna fill you in on so much more…I’ll give you, like, the general overview. I’m gonna get you through today, and I’m gonna make sure you have the care you need,” like, super thoughtful. He gave me studies. He gave me the contact information for [university]. He gave me the information on the conference that’s coming up. Um, he connected me to the information on the Fragile X, like, website.”—Interviewee #18, POI symptoms

Informing family of diagnosis

While the experience of disclosing genetic testing results may largely depend on family dynamics, we identified shared experiences. Participants were often more concerned about other family members’ risk for conditions such as FXPOI and FXTAS rather than their own health. Consistent with existing literature, women with affected children tended to focus more on their child’s health rather than their premutation needs [18, 27–29]. Other family themes included discovery of undisclosed preexisting FXS-related diagnoses, difficulty explaining genetics or inheritance to other family members, feelings of guilt and strained relationships, family support, and difficulty sharing information with family members who were pregnant. Some families rejected the disclosure, while others pursued family cascade testing.

“I’m thinking in my head, I told them to go get pregnant as soon as possible, and there’s a very high likelihood that she’s pregnant with a child who’s mentally retarded…It would be a valued member of the family, but we knew it was a lifetime of care and a lifetime of, like, being responsible for somebody.”—Interviewee #18, POI symptoms

“I feel like I had done so much research and really understood it, it was frustrating because my-my aunt and uncle in particular didn’t really get it, couldn’t understand it. They were not, like, super versed in science.”—Interviewee #3, POI symptoms

“I do feel like being the one who had symptoms, like, I almost have, like, a level of guilt. I don’t know. That was, like, a big thing I went through for a long time.”—Interviewee #2, POI symptoms

Educating oneself and others

Personal research

Participants reported researching information about their diagnosis via the National Fragile X Foundation (NFXF), PubMed, FRAXA Research Foundation, office pamphlets, conferences, and Facebook. Participants sought information on the experiences of other individuals with FXPOI, expected prognosis of the premutation diagnosis, downloadable or printable information guides, research studies, and supportive communities. Some participants described themselves as information seekers but expressed concerns about the lack of guidance for their appropriate care and information that is difficult to understand, consistent with previous study findings [18]. Women also mentioned providing educational materials to other individuals with the premutation.

“I can still, you know, read a journal article and understand statistics, and, like, how many women out there who can’t do that and have no explanation or just all these questions that aren’t answered?”—Interviewee #4, FHx without children

“Facebook groups did give me false hope at first I would say though because, like, you know, people say, like, “Oh, you could get acupuncture and do this juicing thing, and it’ll lower your FSH.””—Interviewee #14, FHx without children

Providing educational materials to clinicians

Most women with FXPOI reported providing educational materials to physicians, including information from NFXF, verbal education, materials regarding HRT, and the necessity of DEXA scans. Specifically, participants mentioned providing information from “Women’s Health and the Fragile X Premutation” (https://fragilex.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/FX-Premutation-Emory-12.13.15.pdf). Women also reported difficulty knowing what specific information they needed to provide, as they were unsure whether they were receiving proper care, consistent with existing literature [18].

Reproductive decisions

Impact of FXPOI infertility

For many, POI disrupts family planning options with reduced ovarian function; however, some women with FXPOI can still become pregnant. Many women reported POI limited their ability for natural conception. Even if individuals were not immediately planning on having children, infertility associated with POI still brought feelings of anger and devastation that the reproductive choice was taken away or limited, consistent with existing literature reporting higher rates of anxiety and depression in women with reproductive difficulties [30]. Women reported relationship challenges due to their POI. Often, women felt consumed with needing to find a path to have children. Other feelings of frustration stemmed from retrospective regret, as individuals would have frozen their eggs or family planned differently at a younger age if they had been aware of their premutation status and POI risks.

“I don’t know if it goes like this for other-other women that find out they’re carriers, but you can get rather obsessed with the idea of, “I’ve got to…be able to have kids. I’ve got to figure out how I’m going to do this.” And I think we—once we went that route, we just plowed into it, and it sort of consumed life.”—Interviewee #13, POI symptoms

“If I knew that there could be fertility issues…I definitely would have looked into a—um, freezing my eggs.”—Interviewee #14, FHx without children

Hesitations due to risk of FXS in another child

Both POI and having a child with FXS impacted participants’ perceptions of the possibility of a second affected child. Most participants with a family history of FXS and half of those diagnosed via POI symptoms without family history decided not to have future children due to the risk of a(nother) child with FXS.

“I don’t think I would have been a really great mom to a special needs child…I felt like I had, like, dodged a bullet in a way.”—Interviewee #4, FHx without children

Assisted reproductive technology

Almost a third of participants used assisted reproductive technology (ART) such as oocyte donors and in vitro fertilization to expand their family, supporting previous findings that ART is more commonly used in the FXPOI population compared to national occurrence [22]. Some participants reported the process as overwhelming and emotional; however, support from friends or family was deemed helpful.

“I definitely recommend using an egg donor…I say I would’ve frozen my eggs. But now having the children I have…when I look at them, I don’t think, oh, he’s an egg donor.”—Interviewee #14, FHx without children

Adoption

Approximately, a third of participants chose adoption, most common in the subgroup FHx without (biological) children. Barriers to adoption were financial and legal processes.

“I mean, as soon as I ma-made the decision to adopt, I was perfectly fine. I never had any regrets or looked back…you can love a child whether it’s adopted or biological, and there’s really no difference.”—Interviewee #5, FHx without children

No longer family planning

A third of participants explained they reached a point where they did not want more children regardless of POI or FXS. Decisions were impacted by social and relationship factors such as strained or ended relationships, financial hardship, concern for the future of the planet, and non-disclosed personal reasons. This was most common in women with a family history of FXS and genetically related children, especially an affected child. This may be due to the strain on families and relationships from already providing care for an affected child.

Emotional health and relationships

Emotional health

All participants described an impact on their emotional health during their diagnostic odyssey. Many felt overwhelmed initially about infertility, lack of point of care, adoption, and/or caretaking of family members. Isolation was discussed by half of participants regarding navigating intimate relationships, forming friendships, and difficulty finding local support networks. In the subgroups without biological children, some women reported feeling inadequate due to infertility, impacting their self-image and feelings about “womanhood.” Some participants regretted not having children at a younger age, as well as the way they disclosed their diagnosis to family members. Some participants experienced guilt revolving around inheritance of the premutation in family members (either parents, siblings, or children). Anxiety over future health comorbidities such as FXTAS occurred across all subgroups. While only one-fourth of participants in all groups mentioned depression, almost all participants shared experiences of grief or loss.

“From the moment that I found out, it was devastating on the one side, and then, like, ignited a firestorm of anxiety about, like, what if I’ve gotten something super rare, what not super rare things can I get?”—Interviewee #11, POI symptoms

“So even if I would’ve had 100 people who were right there supporting me, you still feel very alone because it’s happening to you, and it’s something that’s shocking.”—Interviewee #13, POI symptoms

However, most women in the study reported an improvement in their emotional health over time since receiving their premutation diagnosis.

“I had to realize that I didn’t even treat myself with human dignity. And so, how do I treat other people with human dignity if I’m not doing it for myself? So, I feel really lucky that…I’ve had opportunities to learn it and that-that has helped me tremendously in my therapy and learning to be healthier and protect myself and grow.”—Interviewee #12, FHx without children

Relationships

Nearly half of participants discussed a broken or strained relationship coinciding with their diagnosis, most commonly in the subgroup FHx with children. Relationships included partners and spouses, family, and friendships. Reasons included infertility, broken trust by family members, efforts to encourage other family members to have genetic testing, guilt from parental inheritance, and difficulty with connection/support while having an affected (FXS) child. Positively, one third of participants discussed new relationships that were formed because of their premutation diagnosis through research studies, support groups, online groups, or within routine social circles.

Advice

Advice for medical professionals

When asked how their diagnostic and care experience could be improved, every interviewee discussed the need for increased premutation education and awareness by clinicians, to enable earlier diagnosis, prevent misdiagnosis, and improve point of care service, as well as the creation of guidelines regarding personalized HRT recommendations or DEXA scans.

“I would’ve wanted a phone call scheduled a week after that was like, “Let’s go through now the questions that you have about this diagnosis, and then let’s talk about who will be your primary care.””—Interviewee #23, POI symptoms

“I would’ve liked to have—not-not only had a person to explain it but then to have someone I could call even beyond that…I feel like I’m kinda floating like I have this diagnosis. Most of my doctors don’t—haven’t heard of it or they don’t believe me.”—Interviewee #12, FHx without children

Other recommendations included having clinicians advise women to bring a support person to their appointments, adequate appointment lengths to process the diagnosis with the patient, the use of trauma informed care, and providing women with a mainstream, accessible resource to help them stay up to date with current information. One suggestion for improving patient access to FXPOI resources was developing a premutation registry and listserv for current premutation-related research. Other suggestions included resources to share with family members when explaining the diagnosis and “how to care for a woman with FXPOI” education sheets to bring to medical providers.

“This needs to be blocked off a good 10–30 min minimum where you allocate time to sit down and make sure that your patient understands what the diagnosis is, that you have a plan in place for when you’re gonna see them again, that you’ve provided them with appropriate tools, information, um, mental health services that are available…”—Interviewee #18, POI symptoms

“I would like there to be some sort of, like, just, like, sign up. Um, so, uh, like, people would be sending me study results rather than me always having to look to see if something new has come out.”—Interviewee #23, POI symptoms

Participants expressed hope that future women with FXPOI would get connected to care earlier in their life by receiving fertility/hormone testing at an earlier age, preconception genetic carrier screening including FXS (as seen in [31]), and all available family planning options outlined so they can make informed decisions.

“I would say at least for OBGYN…considering testing prior to pregnancy if people come in prior to pregnancy is…crucial. I think, um, explaining it to them or referring them to genetic counseling right away.”—Interviewee #3, POI symptoms

Advice for other women with FXPOI

Participants advised other women with FXPOI to stay educated, with education being equated with empowerment. Participants recommended bolstering support systems when working through a diagnosis, whether through personal contacts or online premutation community groups. Lastly, participants expressed the importance of finding personal worth outside of fertility, placing value on themselves as individuals, not their reproductive capabilities.

“I think the biggest piece of advice that I could give is that you’re still you…This has happened. It’s a part of you, but you’re still valuable…there’s a way through, whether that is adoption or egg donor or going child-free. There is a way through. You will make it to the other side of that, and, um, you just have to get educated and get support, and it’ll – it’ll be okay.”—Interviewee #13, POI symptoms

Discussion

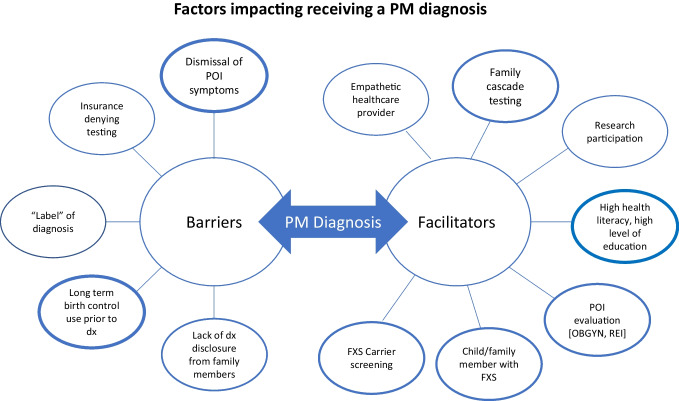

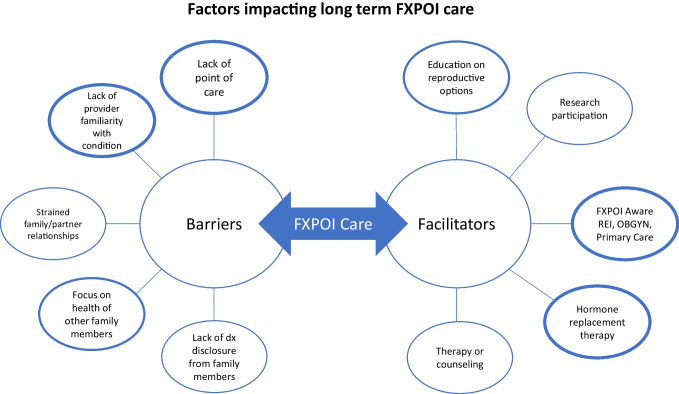

This unique qualitative research provides firsthand perspectives from women with FXPOI regarding their overall experience of diagnosis and follow-up care. Their experiences (outlined in Figs. 1 and 2) reveal a need for necessary surveillance, centralized care, and treatment of women with FXPOI.

Fig. 1.

Barriers and facilitators to receiving a PM diagnosis. Factors which were more commonly discussed by participants are represented by increased line thickness

Fig. 2.

Barriers and facilitators impacting long-term care receival for women with FXPOI. Factors which were more commonly discussed by participants are represented by increased line thickness

The present study suggests women with POI are inadequately served by healthcare providers not offering FMR1 screening pre-diagnosis or comprehensive guidance to appropriately navigate care post-diagnosis. Due to the comprehensive information essential for FXPOI care navigation, it is critical that any healthcare provider ordering genetic testing understands the implications of receiving a premutation diagnosis. While genetic counselors are a valuable component in serving these families from pre-counseling, diagnosis, to post-counseling [31], optimal care for women at risk for FXPOI occurs when genetic counselors and OB/GYNs work together.

The present study also confirms women with POI can experience a lack of sensitivity, knowledge, and helpful suggestions from medical providers. Previous research found 71% of women with POI were unsatisfied with how they received their diagnosis, and 53% felt their physician had limited knowledge of POI [17]. This is especially concerning since health professionals are the main source of information for people with POI [32]. Negative experiences with healthcare providers only delay a premutation or FXPOI diagnosis, for which timely care is essential in reducing comorbidities and improving quality of life [18].

Women with the premutation are predisposed to FXAND [24], and medical invalidation or dismissal of symptoms is likely to exacerbate feelings of stress, anger, anxiety, or depression—emotions discussed by nearly all study participants. Women in this study discussed emotional ramifications in relation to strained or ended relationships, consistent with Seltzer’s (2012) report of a significantly higher rate of divorce among women with FXPOI than controls (26.7% divorced at age 53–54 compared to 10.4% of comparison group) [4]. Family relationships were often strained by hesitations of having an (additional) affected child with FXS. Most women in the FHx groups and half of women with POI voiced concerns about the emotional impact that would result from parenting an affected child, which may be due to prior personal experience with care of a child with FXS or self-perceptions about their ability to do so. Increased emotional response combined with high strain on relationships supports the need for increased emotional support services, including therapy and counseling as part of follow-up care.

Women with FXPOI should also be connected to research centers, which were viewed positively by participants of this study. Creation of a FXPOI newsletter and promoting the newly developed NFXF International Fragile X Premutation Registry (https://fragilex.org/our-research/projects/premutation-registry/) would provide women with FXPOI access to current studies and future research opportunities. A listing of providers with education or background in FXPOI may also decrease the burden of women with FXPOI struggling to identify specialized providers in their area.

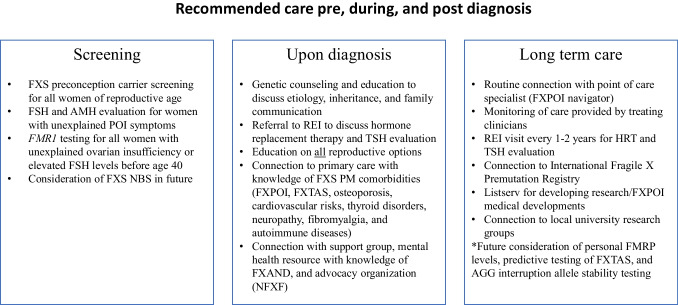

Our recommendations (outlined in Fig. 3) include preconception genetic carrier screening for FXS (FMR1 CGG repeat testing) for all women of childbearing age to identify the premutation in women who are considering family planning. Existing literature also supports FMR1 CGG repeat screening for all women of reproductive age due to relatively high incidence in the general population [6, 19]. Offering a hormone evaluation of FSH and AMH levels for women with POI symptoms may serve as a screening tool outside of genetic testing for women who may be at risk of carrying the premutation. In addition, FXS newborn screening could be considered to identify new mothers who are premutation carriers and may be at risk of FXPOI, as literature has shown there may not be negative psychosocial impacts of FXS inclusion of newborn screening [33]. Women have previously expressed interest in personal FMRP levels, predictive testing of FXTAS, and testing for allele stability (AGG interruptions) which could be considered for future care guidelines [20].

Fig. 3.

Recommended care pre, during, and post FXPOI diagnosis

Limitations

The study was limited in the diversity of the sample, with all but one participant reporting white European ancestry. This study also did not account for current household income; however, this was previously recorded for some participants in the Emory database which indicates most participants obtained a college education or higher with household incomes of greater than $50,000. A significant limitation of this study is that participants were from a FXS academic research center database and therefore had greater access to resources and information. Lastly, this study used individuals who received a FXPOI diagnosis from 0 to 41 years ago. It is possible reported diagnostic experiences may have improved in recent years; however, the study did include recently diagnosed participants.

Future directions

Future directions for this research include the development of FXPOI materials including a clinical care sheet for women with FXPOI and development of an educational guide for OBGYN/REI healthcare providers to increase clinician knowledge. A FXPOI knowledge and care plan assessment may be beneficial to better understand the gaps in care from the perspective of medical providers. Additionally, exploration of the diagnostic and follow-up care experience in minority populations would help identify any care disparities in this patient population. Information from this study may be used and referenced when developing future FXS or premutation screening or care guidelines. Lastly, this research provides evidence for the creation of a FXPOI navigator, an experienced healthcare provider, or patient advocate specializing in support and coordination of FXPOI-related care. This service could potentially be provided online to ensure equitable access for patients.

Conclusion

The overall diagnostic experience and follow-up care of women with FXPOI must be improved. Many women reported having to advocate for their own diagnosis and care, often visiting multiple providers before their concerns or POI symptoms were evaluated. Ideally, a care navigator would connect women with FXPOI to endocrinologists for recommended hormone replacement therapy [34, 35] and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) evaluations, OBGYNs familiar with POI, primary care providers who understand associated health risks such as osteoporosis and other comorbidities, and mental health support. Coordinated care between OBGYNs and genetic counselors is also needed to communicate risks for family members, pathophysiology of the condition, education for possible clinical manifestations, reproductive options, and inheritance risks (including repeat expansion likelihood with AGG interruptions) [19].

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all women who participated and shared their experiences for this research study.

Funding

This study received funding from the National Fragile X Foundation, the Georgia Association of Genetic Counselors, and the NICHD and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) that supports our National Fragile X Center (U54NS091859 and P50HD104463) in which this work was conducted. This study also utilized a REDCap database supported by Emory’s Library and Information Technology Services (UL1TR000424).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Garber KB, Visootsak J, Warren ST. Fragile X syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16(6):666–672. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maenner MJ, et al. FMR1 CGG expansions: prevalence and sex ratios. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2013;162B(5):466–473. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tassone F, et al. FMR1 CGG allele size and prevalence ascertained through newborn screening in the United States. Genome Med. 2012;4(12):100. doi: 10.1186/gm401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seltzer MM, et al. Prevalence of CGG expansions of the FMR1 gene in a US population-based sample. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2012;159B(5):589–597. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hipp HS, et al. Reproductive and gynecologic care of women with fragile X primary ovarian insufficiency (FXPOI) Menopause. 2016;23(9):993–999. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansen Taber K, et al. Fragile X syndrome carrier screening accompanied by genetic consultation has clinical utility in populations beyond those recommended by guidelines. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7(12):e1024. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen EG, et al. Examination of reproductive aging milestones among women who carry the FMR1 premutation. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(8):2142–2152. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoyos LR, Thakur M. Fragile X premutation in women: recognizing the health challenges beyond primary ovarian insufficiency. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34(3):315–323. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0854-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan SD, Welt C, Sherman S. FMR1 and the continuum of primary ovarian insufficiency. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29(4):299–307. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1280915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman SL. Premature ovarian failure in the fragile X syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2000;97(3):189–194. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(200023)97:3<189::AID-AJMG1036>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wittenberger MD, et al. The FMR1 premutation and reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(3):456–465. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen EG, et al. Refining the risk for fragile X-associated primary ovarian insufficiency (FXPOI) by FMR1 CGG repeat size. Genet Med. 2021;23(9):1648–1655. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01177-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray A, et al. Reproductive and menstrual history of females with fragile X expansions. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8(4):247–252. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan AK, et al. Association of FMR1 repeat size with ovarian dysfunction. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(2):402–412. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ACOG Committee opinion no. 691: carrier screening for genetic conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):e41–e55. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finucane B, et al. Genetic counseling and testing for FMR1 gene mutations: practice guidelines of the national society of genetic counselors. J Genet Couns. 2012;21(6):752–760. doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9524-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groff AA, et al. Assessing the emotional needs of women with spontaneous premature ovarian failure. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(6):1734–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espinel W, et al. Improving health education for women who carry an FMR1 premutation. J Genet Couns. 2016;25(2):228–238. doi: 10.1007/s10897-015-9862-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Man L, et al. Fragile X-associated diminished ovarian reserve and primary ovarian insufficiency from molecular mechanisms to clinical manifestations. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:290. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smolich L, Charen K, Sherman SL. Health knowledge of women with a fragile X premutation: improving understanding with targeted educational material. J Genet Couns. 2020;29(6):983–991. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coffey SM, et al. Expanded clinical phenotype of women with the FMR1 premutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A(8):1009–1016. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheeler AC, et al. Health and reproductive experiences of women with an FMR1 premutation with and without fragile X premature ovarian insufficiency. Front Genet. 2014;5:300. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenna HA, et al. High rates of comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders among women with premutation of the FMR1 gene. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2013;162B(8):872–878. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagerman RJ, et al. Fragile X-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (FXAND) Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:564. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen EG, et al. Clustering of comorbid conditions among women who carry an FMR1 premutation. Genet Med. 2020;22(4):758–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Allen EG, et al. Predictors of comorbid conditions in women who carry an FMR1 premutation. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:715922. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.715922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abbeduto L, et al. Psychological well-being and coping in mothers of youths with autism, Down syndrome, or fragile X syndrome. Am J Ment Retard. 2004;109(3):237–254. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<237:PWACIM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anido A, et al. Women’s attitudes toward testing for fragile X carrier status: a qualitative analysis. J Genet Couns. 2005;14(4):295–306. doi: 10.1007/s10897-005-1159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wheeler A, et al. Correlates of maternal behaviours in mothers of children with fragile X syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2007;51(Pt. 6):447–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunter JE, Rohr JK, Sherman SL. Co-occurring diagnoses among FMR1 premutation allele carriers. Clin Genet. 2010;77(4):374–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Archibald AD, et al. “It gives them more options”: preferences for preconception genetic carrier screening for fragile X syndrome in primary healthcare. J Community Genet. 2016;7(2):159–171. doi: 10.1007/s12687-016-0262-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singer D, et al. The silent grief: psychosocial aspects of premature ovarian failure. Climacteric. 2011;14(4):428–437. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2011.571320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bailey DB, Jr, et al. Maternal consequences of the detection of fragile X carriers in newborn screening. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):e433–e440. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armeni E, et al. Hormone therapy regimens for managing the menopause and premature ovarian insufficiency. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;35(6):101561. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2021.101561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.North American Menopause S. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of: the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.