Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the impact of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) on cumulative live birth rate (CLBR) in IVF cycles.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of the SART CORS database, comparing CLBR for patients using autologous oocytes, with or without PGT-A. The first reported autologous ovarian stimulation cycle per patient between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2015, and all linked embryo transfer cycles between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2016, were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were donor oocyte cycles, donor embryo cycles, gestational carrier cycles, cycles which included both a fresh embryo transfer (ET) combined with a thawed embryo previously frozen (ET plus FET), or cycles with a fresh ET after PGT-A.

Results

A total of 133,494 autologous IVF cycles were analyzed. Amongst patients who had blastocysts available for either ET or PGT-A, including those without transferrable embryos, decreased CLBR was noted in the PGT-A group at all ages, except ages > 40 (p < 0.01). A subgroup analysis of only those patients who had PGT-A and a subsequent FET, excluding those without transferrable embryos, demonstrated a very high CLBR, ranging from 71.2% at age < 35 to 50.2% at age > 42. Rates of multiple gestations, preterm birth, early pregnancy loss, and low birth weight were all greater in the non-PGT-A group.

Conclusions

PGT-A was associated with decreased CLBR amongst all patients who had blastocysts available for ET or PGT-A, except those aged > 40. The negative association of PGT-A use and CLBR per cycle start was especially pronounced at age < 35.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10815-022-02667-x.

Keywords: Preimplantation genetic testing, PGT, IVF, Genetics

Introduction

Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) is utilized to screen embryos for chromosomal aneuploidy created through IVF. Current PGT-A protocols involve either conventional insemination or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) of retrieved oocytes, and biopsy of trophectoderm cells at the blastocyst stage [1, 2].

Purported benefits of PGT-A include increased live birth rate per embryo transferred [3, 4], decreased risk of twins or higher order multiples [3, 5], decreased risk of early pregnancy loss [6], decreased time to pregnancy [6], and decreased cost [6] compared with transferring untested embryos. However, the impact of PGT-A utilization on cumulative live birth rate (CLBR) per IVF cycle start, instead of per embryo transfer (ET), only recently started to be fully evaluated [7–13]. As such, PGT-A is not currently recommended for routine use in all patients [14].

An improvement in cumulative live birth rate (CLBR) with PGT-A utilization, calculated per cycle start, cannot be assumed because simply testing embryos for aneuploidy does not increase the number of euploid embryos, nor does it decrease the number of aneuploid embryos [6, 15, 16]. Studies which have investigated the utility of PGT-A have often analyzed live birth rates on a per embryo transfer basis [4, 6, 16], therefore excluding from analysis IVF cycles without transferrable embryos. As a result, this type of analysis may artificially inflate the apparent utility of PGT-A in improving CLBR [8]. Studies from single practices have suggested improved CLBR with PGT-A [17], but this has not been consistently demonstrated [6, 18, 19].

In this study, we hypothesized that there would be no difference in CLBR with or without PGT-A on a per-cycle start basis, and we used national SART CORS data to evaluate this relationship.

Materials and methods

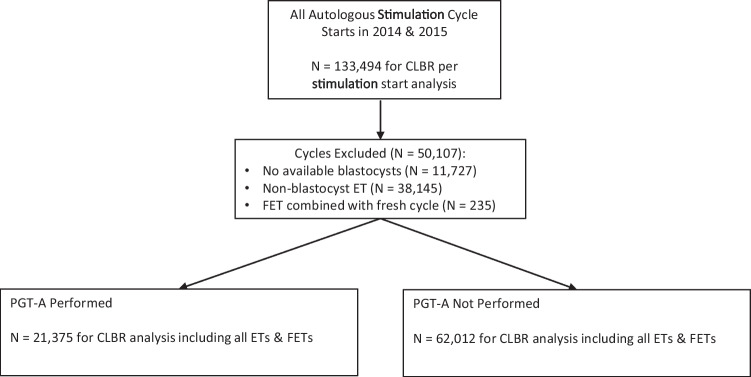

Autologous oocyte IVF cycles from 2014 to 2016 reported to the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinic Outcome Reporting System (SART CORS) were evaluated in this retrospective cohort study. SART CORS is a national registry of over 85% of programs performing IVF cycles in the USA [20, 21]. The first reported autologous oocyte ovarian stimulation cycle per patient between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2015, and all linked embryo transfer cycles between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2016, were included in the study (Fig. 1). These dates were chosen to allow for ample time to proceed with multiple embryo transfers after a completed stimulation cycle. For the analysis of CLBR per autologous stimulation cycle start, exclusion criteria were donor oocyte cycles, donor embryo cycles, gestational carrier cycles, and embryo banking cycles. For the analysis of CLBR in the setting of having blastocysts available for ET, FET, or PGT-A biopsy, exclusion criteria were expanded to also include non-blastocyst embryo transfer cycles (such as cleavage-stage embryo transfers), elective sex selection cycles, cycles which included both a fresh embryo transfer (ET) and frozen embryo transfer (FET), or cycles in which a fresh ET followed PGT-A. Embryo banking cycles were excluded as these patients did not have any intention of transferring an embryo, and thus could not have reasonably been expected to undergo a transfer cycle within the timeframe of the study. Cycles which included both a fresh ET and a frozen ET were excluded to avoid the possibility of transfer of both PGT-A tested and untested embryos simultaneously. Cycles which included both a fresh ET as well as PGT-A were excluded, as they did not fulfill the dichotomous inclusion criteria, namely whether or not to undertake either fresh ET or PGT-A. Additionally, it is possible that those cycles included cleavage-stage embryo biopsy, which has since been demonstrated to result in reduced implantation rates and is not widely utilized today[1, 22]. Stimulation cycles which were listed as “Yes” for “all or some embryos” were classified as PGT-A cycles; those listed as “No” were not. Cycles where the PGT-A status was unknown were excluded. As PGT-A cytogenetic analysis methods were not available in the SART CORS database, no methods were specifically excluded during the study period.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart

In the control group, the first fresh ET or FET, followed by all subsequent FETs linked to the original stimulation cycle, was analyzed for pregnancy outcomes. In the PGT-A group, all FETs linked to the original stimulation cycle were analyzed for pregnancy outcomes. All PGT-A and non-PGT-A cycles without a subsequent linked fresh ET or FET, and not classified as “multiple cycles for embryo banking,” were categorized as negative pregnancy outcomes.

The primary outcome measure was CLBR for autologous IVF cycles on a cycle start basis, both with and without the use of PGT-A, as defined by all ET and FET outcomes prior to and including the first live birth event within the study period. Only the first live birth linked to a stimulation cycle was recorded for each patient. Secondary outcome measures included the rates of multiple gestations (as determined by the number of infants delivered at the first birth event following a stimulation cycle), preterm and very preterm birth, early pregnancy loss at less than 13 weeks gestation (including pregnancies where a positive beta-HCG test was noted), male and female infant secondary sex ratios, and low birth weight infants.

Descriptive statistics such as count (%) and mean (standard deviation) were presented both overall and stratified by group. Associations between birth outcomes and group (PGT-A vs. no PGT-A) within each age group category were assessed via logistic regression (CLBR, preterm birth, miscarriage, any birth weight < 2500 or 1500g, infant sex), Poisson’s regression (number of live births with total number of patients per group as offset), or linear (birthweight) regression models. When comparing live birth events, a model adjusting for patient diagnosis was also utilized. In models for birthweight and male sex, Generalized Estimating Equation–based standard errors were used to adjust standard errors for the assumed correlation between outcomes from the same (non-singleton) birth event. Associations between birth outcomes and age group category were examined within each group via trend tests using similar models as described above. Two-sided p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc. Copyright 2016. Cary, NC USA).

The data used for this study were obtained from the SART Clinic Outcome Reporting System (SART CORS). Data were collected through voluntary submission, verified by SART, and reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in compliance with the Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act of 1992 (Public Law 102-493). SART maintains HIPAA-compliant business associates’ agreements with reporting clinics. In 2004, following a contract change with the CDC, SART gained access to the SART CORS data system for the purposes of conducting research. In 2017, 82% of all assisted reproductive technology (ART) clinics in the USA were SART members [23]. Data validation was conducted by the CDC and applied to all centers reporting to the National Assisted Reproductive Technology Surveillance System (NASS), which includes the centers not reporting to SART.

The data in the SART CORS are validated annually with 7–10% of clinics receiving on-site visits for chart review based on an algorithm for clinic selection. During each visit, data reported by the clinic were compared with information recorded in patients’ charts. In 2019, records for 2014 cycles at 34 clinics were randomly selected for full validation, along with 213 fertility preservation cycles selected for partial validation. The full validation included a review of 1300 cycles for which a pregnancy was reported. Nine out of eleven data fields selected for validation were found to have discrepancy rates of ≤5% [23].

The exceptions were the diagnosis field, which, depending on the diagnosis, had a discrepancy rate between 2.5 and 17.8%, and the start date, which had an 8.4% discrepancy rate [23]. Approval for this study was obtained from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB# 2016-7031).

Results

Patient demographics per stimulation cycle start

Autologous (n=113,494) first reported stimulation cycle starts were analyzed. Amongst women who started an autologous cycle, the plurality of patients was aged < 35 (46.61%), and the majority of patients were nulligravid (50.96%) and nulliparous (74.6%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics—all cycle starts

| N=133,494 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| Age at cycle start |

< 35 35–37 38–40 41–42 > 42 |

62,228 28,768 24,358 11,158 6982 |

46.61 21.55 18.25 8.36 5.23 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 | 5.8 (SD) | |

| Gravidity | Nulligravid | 67,813 | 50.96 |

| Parity | Nulliparous | 99,228 | 74.6 |

| Etiology |

Male infertility Endometriosis PCOS Diminished ovarian Reserve Uterine factor Tubal Other Unexplained |

47,231 11,543 20,276 33,966 7403 18,516 19,704 19,925 |

35.38 8.65 15.19 25.44 5.55 13.87 14.76 14.93 |

| Prior GN cycle | 21,462 | 16.08 | |

| Prior fresh cycle | 27,640 | 20.71 | |

| Prior FET cycle | 7297 | 5.47 | |

| Max FSH (mIU/mL)* | 7.98 | 4.7 (SD) | |

| AMH (ng/mL) * | 3.39 | 3.6 (SD) | |

| Number of embryos available& |

0 1 2 3 4 5+ |

11,727 15,191 30,343 20,211 15,332 40,658 |

8.79 11.38 22.74 15.14 11.49 30.46 |

Data are presented as n (%) unless continuous variable, which is summarized as mean (SD). *Max FSH missing: n=41,396. AMH missing: n=51,391. BMI missing: n=23,659. &Total embryos available for transfer (number fresh embryos transferred + number frozen)

Increased maternal age was associated with decreased CLBR for all stimulation cycle starts (including PGT-A cycles). CLBR for those aged < 35 was 58.7% per stimulation cycle start, compared with 46.9%, 31.2%, 15.7%, and 4.9% for those aged 35–37, 38–40, 41–42, and > 42, respectively (p < 0.001 for all comparisons) (Supplemental Table 1).

Patient demographics per cycle with blastocysts available for ET or PGT-A

A total of 83,387 first reported stimulation cycle starts resulted in blastocysts available either for biopsy for PGT-A or for fresh transfer. Patients who utilized PGT-A were evenly distributed amongst age groups (32.75% < age 35, 24.43% ages 35–37, 25.74% ages 38–40), while 60.98% of patients < age 35 underwent a fresh blastocyst transfer without PGT-A (Supplemental Table 2). The vast majority of patients were nulliparous for cycles that utilized PGT-A (72.47%), and for cycles with a fresh transfer without PGT-A (76.89%). The most common infertility diagnosis was “other” for PGT-A cycles (35.75%) while male factor infertility was the most common diagnosis for those who had a fresh transfer without PGT-A (38.78%). Of patients who underwent PGT-A, 64% underwent subsequent FET at age < 35, 62.6% at age 35–37, 53.9% at age 38–40, 38% at age 41–42, and 18.8% at age > 42 (Supplemental Table 2).

Cumulative live birth rates per cycle with blastocysts available for ET or PGT-A

Next, we compared CLBR per first reported stimulation cycle for patients who utilized PGT-A versus those who did not utilize PGT-A (including all linked fresh ETs and FETs). As previously stated, cycles which utilized PGT-A and did not result in an embryo transfer within the time frame of the study were considered negative pregnancy outcomes. In all age groups except in those aged > 40, CLBR per cycle was lower in the PGT-A group versus those who did not utilize PGT-A (p < 0.01). This difference was most pronounced in those aged < 35 (Table 2), where a 12.7% difference in CLBR was observed in the unadjusted model, and 12.2% when adjusted for patient diagnosis (Table 2). Furthermore, when adjusting the model for patient diagnosis, no further impact was noted on the CLBR of each age group or on the analysis as a whole (Table 2). Patients who had blastocysts and utilized PGT-A had a CLBR per cycle start age < 35 of 57.4% and 11% > age 42 (p (trend) < 0.01) (Supplemental Table 4). In contrast, patients who had blastocysts and did not utilize PGT-A had a CLBR per cycle start of 70.1% aged < 35 and 10.4% aged > 42 (p (trend) < 0.01) (Supplemental Table 5). A subgroup analysis of only those patients who had PGT-A and subsequently underwent FET was also performed. Of note, this analysis included all subsequent FETs after PGT-A and excluded PGT-A cycles without transferrable embryos. These results demonstrated a very high CLBR which varied across age groups, ranging from 71.2% at age < 35 to 50.2% at age > 42 (Supplemental Table 3, p (trend) < 0.01).

Table 2.

Live birth events, by patient age and PGT-A use (% of patients in age group and by PGT-A use)

| PGT-A | No PGT-A | Abs. CLBR difference |

P-value | % adjusted CLBR difference |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 9683 (45.3) | 38,558 (62.3) | 17% (16.1, 17.7) | <0.0001 | 13.0% (12.2, 13.8) | <0.0001 |

| < 35 | 4015 (57.4) | 26,510 (70.1) | 12.7% (11.5, 14.0) | <0.0001 | 12.2% (10.9, 13.4) | <0.0001 |

| 35–37 | 2719 (52.1) | 7901 (60.5) | 8.4% (6.9, 10.0) | <0.0001 | 7.9% (6.2, 9.5) | <0.0001 |

| 38–40 | 2218 (40.3) | 3434 (44.1) | 3.8% (2.1, 5.5) | <0.0001 | 2.7% (1.0,4.5) | <0.01 |

| 41–42 | 607 (24.0) | 611 (25.7) | 1.7% (−0.8, 4.1) | 0.18 | 1.4% (−1.0%, 3.9%) | 0.25 |

| > 42 | 124 (11.0) | 102 (10.4) | −0.6% (−3.2, 2.1) | 0.66 | −1.4% (−4.0%, 1.3) | 0.32 |

*Live birth recorded after first and any subsequent transfer

%Adjusted for diagnosis (tubal, diminished reserve, male infertility, PCOS, uterine, tubal endometrial, other/unexplained diagnosis)

Multiple gestations

When evaluating multiple gestations, rate of preterm birth, early pregnancy loss, secondary sex ratio, and infant birth weight, only cycles which resulted in an embryo transfer were included, as these outcomes are only possible in the setting of an embryo transfer. Amongst patients aged < 42 who had an ET, the singleton rate was 6–10% higher for those with PGT-A versus those who did not utilize PGT-A (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 3) (p < 0.01). Additionally, a significantly lower rate of twin deliveries was noted amongst those who utilized PGT-A in all age groups, except at age > 42, compared to no PGT-A (p (trend) < 0.01). The rate of higher order multiples (≥ 3 infants) was ≤1% in all age groups.

Table 3.

Number of singleton and multiple deliveries, by patient age and PGT use (%)

| Singleton | Twins | Triplets+ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGT-A | No PGT-A | PGT-A | No PGT-A | PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value^ | |

| Overall | 8425 (87.0) | 29,708 (77.1) | 1231 (12.7) | 8630 (22.4) | 27 (0.3) | 220 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

| < 35 | 3416 (85.1) | 20,242 (76.4) | 585 (14.6) | 6114 (23.1) | 14 (0.35) | 154 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

| 35–37 | 2361 (86.8) | 6130 (77.6) | 354 (13.0) | 1733 (21.9) | 4 (0.15) | 38 (.5) | <0.0001 |

| 38–40 | 1975 (89.0) | 2724 (79.3) | 237 (10.7) | 690 (20.1) | 6 (0.27) | 20 (.6) | <0.0001 |

| 41–42 | 553 (91.1) | 521 (85.3) | 51 (8.4) | 83 (13.6) | 3 (0.49) | 7 (1.2) | <0.01 |

| > 42 | 120 (96.8) | 91 (89.2) | 4 (3.2) | 10 (9.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) | 0.07 |

*Live birth recorded after first and any subsequent transfer

^p-value for overall association between groups

Preterm births

Rates of preterm birth < 37 weeks, < 34 weeks, and < 28 weeks were decreased amongst patients who utilized PGT-A and underwent FET, compared with those who had blastocysts available to transfer without PGT-A (24.6% vs 32.6% at < 37 weeks, 7% vs. 10.2% at < 34 weeks, and 1.2% vs 2.2% at < 28 weeks, respectively) (p < 0.0001) (Table 4). These differences achieved statistical significance at ages < 40 but did not at ages > 40. When analyzing the rate of preterm birth based only upon singleton births, this association continued to be noted overall at all gestational ages (p < 0.01 for all comparisons) (Table 5). These differences achieved statistical significance at ages < 37 at all gestational ages, and at ages 38–40 at gestational age < 37 weeks. At all other gestational ages at age > 37, these comparisons were not statistically significant.

Table 4.

Incidence of preterm birth, by gestational age, patient age, and PGT use (%)

| < 37 weeks | < 34 weeks | < 28 weeks | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | |

| Overall | 2382 (24.6) | 12,556 (32.6) | <0.0001 | 678 (7) | 3917 (10.2) | <0.0001 | 119 (1.2) | 831 (2.2) | <0.0001 |

| < 35 | 1024 (25.5) | 8678 (32.7) | <0.0001 | 301 (7.5) | 2754 (10.4) | <0.0001 | 51 (1.3) | 595 (2.2) | <0.0001 |

| 35–37 | 651 (24) | 2546 (32.2) | <0.0001 | 178 (6.6) | 777 (9.8) | <0.0001 | 32 (1.2) | 158 (2) | <0.0001 |

| 38–40 | 528 (23.8) | 1124 (32.7) | <0.0001 | 152 (6.9) | 330 (9.6) | <0.001 | 26 (1.2) | 68 (2) | <0.05 |

| 41–42 | 149 (24.6) | 180 (29.5) | 0.05 | 42 (6.9) | 52 (8.5) | 0.3 | 10 (1.7) | 9 (1.5) | 0.81 |

| > 42 | 30 (24.2) | 28 (27.5) | 0.58 | 5 (4) | 4 (3.9) | 0.97 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.27 |

*Based on the first live births recorded if multiple live births from different transfers

Table 5.

Incidence of preterm birth, by gestational age, patient age, and PGT use (%) (singleton births only)

| < 37 weeks | < 34 weeks | < 28 weeks | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | |

| Overall | 1424 (16.9) | 5733 (19.3) | <0.0001 | 352 (4.2) | 1490 (5) | <0.01 | 71 (0.8) | 397 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| < 35 | 557 (16.3) | 3824 (18.9) | <0.001 | 135 (4) | 978 (4.8) | <0.05 | 24 (0.7) | 263 (1.3) | <0.01 |

| 35–37 | 383 (16.2) | 1201 (19.6) | <0.001 | 93 (3.9) | 328 (5.4) | <0.01 | 19 (0.8) | 84 (1.4) | <0.05 |

| 38–40 | 352 (17.8) | 584 (21.4) | <0.01 | 93 (4.7) | 154 (5.7) | 0.15 | 20 (1) | 40 (1.5) | 0.17 |

| 41–42 | 106 (19.2) | 104 (20) | 0.74 | 27 (4.9) | 27 (5.2) | 0.82 | 8 (1.5) | 9 (1.7) | 0.8 |

| > 42 | 26 (21.7) | 20 (22) | 0.96 | 4 (3.3) | 3 (3.3) | 0.98 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 0.43 |

*Based on the first live births recorded if multiple live births from different transfers

Early pregnancy loss

The overall rate of early pregnancy loss at < 13 weeks gestation was 7% with PGT-A compared with 12.5% without PGT-A (Table 6) (p < 0.0001). At all ages, PGT-A was associated with a decreased rate of early pregnancy loss, compared with no PGT-A (p < 0.0001). This difference was especially pronounced at age > 42 (3.4% for PGT-A vs. 12.6% for no PGT-A).

Table 6.

Early pregnancy loss rate at < 13 weeks gestation, by patient age and PGT use (%)

| PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 1485 (7.0) | 7752 (12.5) | <0.0001 |

| < 35 | 567 (8.1) | 4260 (11.3) | <0.0001 |

| 35–37 | 406 (7.8) | 1772 (13.6) | <0.0001 |

| 38–40 | 351 (6.4) | 1213 (15.6) | <0.0001 |

| 41–42 | 123 (4.9) | 384 (16.1) | <0.0001 |

| > 42 | 38 (3.4) | 123 (12.6) | <0.0001 |

*Recorded after first and any subsequent transfer

Secondary sex incidence

There was a similar incidence of infant male sex between patients who utilized PGT-A (51.6%) versus no PGT-A (51.6%), with no statistically significant differences in any age group (Table 7 and Supplemental Table 3). Amongst those who utilized PGT-A and underwent FET, age > 42 was associated with a reduced incidence of infant male sex (34.9%), although a relatively small number of live births occurred in this age group (n=106) (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 7.

Number of infants delivered/total ETs+FETs performed, and incidence of male sex, by age and PGT use (%)

| Total infants delivered/ETs+FETs performed | Male sex | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value (male sex) | |

| Overall | 8970/11,946 | 47,628/62,012 | 0.05 | 4624 (51.8) | 24,456 (51.6) | 0.77 |

| < 35 | 3639/4482 | 32,932/37,812 | <0.0001 | 1921 (53.0) | 17,008 (51.9) | 0.2 |

| 35–37 | 2543/3270 | 9710/13,057 | 0.05 | 1285 (50.9) | 4983 (51.6) | 0.49 |

| 38–40 | 2105/3023 | 4164/7785 | <0.0001 | 1091 (52.0) | 2083 (50.4) | 0.24 |

| 41–42 | 575/960 | 708/2380 | <0.0001 | 290 (50.9) | 332 (47.2) | 0.2 |

| > 42 | 108/211 | 114/978 | <0.0001 | 37 (34.9) | 50 (44.3) | 0.17 |

*Based on a Poisson regression model for total live birth count

Low birth weight (LBW) and very low birth weight (VLBW) infants

Overall, patients who utilized PGT-A had a decreased incidence of low birth weight (LBW) < 2500g (18.4%) versus those who did not utilize PGT-A (27.5%); this difference was also noted when evaluating the incidence of very low birth weight (VLBW) < 1500g (3% for PGT-A vs. 4.9% for no PGT-A, respectively) (p < 0.0001 for both comparisons) (Table 8). These differences were noted at all ages ≤ 40. However, at age 41–42, there was no significant difference in the incidence of VLBW < 1500g between the PGT-A and no PGT-A groups (p = 0.8). The use of PGT-A was associated with an increased average birthweight compared with the no PGT-A group. This difference was an average of 199g and was statistically significant (p < 0.01) at all ages except at age > 42 (p = 0.09). There was also no significant difference between the incidence of VLBW birthweights in the age > 42 group (p = 0.11), but it should be noted that there were only 3 births in the VLBR < 1500g group for patients age > 42 (all in the no PGT-A group) and none in the PGT-A group.

Table 8.

Average neonatal birthweight, by age and PGT use

| Average birth weight, grams, and SD | Birth weight < 2500g (%) | Birth weight < 1500g (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | |

| Overall | 3113 (783) | 2914 (845) | <0.0001 | 1996 (18.4) | 12,997 (27.5) | <0.0001 | 322 (3.0) | 2330 (4.9) | <0.0001 |

| < 35 | 3076 (740) | 2905 (824) | <0.0001 | 932 (20.3) | 9141 (28.0) | <0.0001 | 157 (4.3) | 1656 (5.1) | <0.0001 |

| 35–37 | 3132 (909) | 2928 (935) | <0.0001 | 551 918.0) | 2623 (27.2) | <0.0001 | 84 (2.7) | 452 (4.7) | <0.0001 |

| 38–40 | 3151 (715) | 2984 (816) | <0.0001 | 405 (16.6) | 1036 (25.2) | <0.0001 | 59 (2.4) | 197 (4.8) | <0.0001 |

| 41–42 | 3129 (695) | 2997 (728) | <0.01 | 96 (14.7) | 173 (24.5) | <0.0001 | 22 (3.4) | 22 (3.1) | 0.8 |

| > 42 | 3243 (587) | 3088 (657) | 0.09 | 12 (9.6) | 24 (21.2) | <0.05 | 0 (0) | 3 (2.7) | 0.11 |

*Based on the first live births recorded if multiple live births from different transfers

When evaluating birth weight only and only comparing singleton births, PGT-A was again associated with a decreased incidence of LBW and VLBW deliveries, compared with the no PGT-A group (7.6% vs 9.5%, p < 0.0001 for LBW, and 1.3% vs 2%, p < 0.01 for VLBW, respectively). This association was statistically significant at ages < 40, but not at ages > 40, although at ages > 40 there was noted to be a substantially smaller sample size than for all deliveries. Amongst singleton deliveries, PGT-A use was associated with a lower overall average birthweight than no PGT-A (Table 9). This difference was an average of 69g, and was statistically significant at all ages < 40, but not at ages > 40.

Table 9.

Average neonatal birth weight, by age and PGT use (singleton births only)

| Average birth weight, grams, and SD | Birth weight < 2500g (%) | Birth weight < 1500g (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | PGT-A | No PGT-A | P-value | |

| Overall | 3263 | 3332 | <0.0001 | 634 (7.6) | 2792 (9.5) | <0.0001 | 110 (1.3) | 575 (2) | <0.01 |

| < 35 | 3268 | 3336 | <0.0001 | 254 (7.5) | 1836 (9.1) | <0.01 | 43 (1.3) | 372 (1.9) | <0.05 |

| 35–37 | 3263 | 3339 | <0.0001 | 172 (7.3) | 622 (10.2) | <0.0001 | 29 (1.2) | 126 (2.1) | <0.05 |

| 38–40 | 3229 | 3332 | <0.0001 | 157 (8) | 267 (9.9) | <0.05 | 26 (1.3) | 65 (2.4) | <0.05 |

| 41–42 | 3240 | 3281 | 0.28 | 43 (7.9) | 56 (10.8) | 0.1 | 12 (2.1) | 12 (2.2) | 0.93 |

| > 42 | 3372 | 3300 | 0.72 | 8 (6.8) | 11 (12.2) | 0.18 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 0.43 |

*Based on the first live births recorded if multiple live births from different transfers

Discussion

Cumulative live birth rate and maternal age

In this study, we used national SART CORS data to demonstrate associations between PGT-A and cumulative live birth rate per first reported stimulation cycle start in patients undergoing autologous IVF cycles. In agreement with the other reports in the literature, we demonstrate that increased maternal age is associated with decreased CLBR in all autologous stimulation cycles. Increasing patient age was associated with decreasing live birth rate, both on a per-cycle basis and on a per-embryo transfer basis; this is most likely due to increased aneuploidy with increasing maternal age [24–26]. Additionally, this association persisted in patients who utilized PGT-A. This is consistent with recently published data suggesting that age itself is an independent predictor of fertility, regardless of embryo ploidy status [27].

Cumulative live birth rates in non-PGT-A cycles

The CLBR from non-PGT-A cycles in our study is similar to CLBR reported in prior studies [16, 28]. For example, Sacchi et al. [16] reported a CLBR of 24.8% for 2718 patients, ages 38–44 with transferrable, blastocyst, non-PGT-A embryos, similar to our finding of 24% for patients aged 40–41 (their data was not subcategorized further by age) (Table 2). Their CLBR for patients who utilized PGT-A and had transferrable embryos was 53.3%, similar to our rate of 54.9% in the age 40–41 age group (Table 2) [16]. Goldman et al. [28] conducted an analysis of 51,959 IVF cycles in the SART CORS database, and reported an autologous, non-PGT-A, blastocyst transfer CLBR of 59.2% for ages 35–37, 42.5% for ages 38–40, 24.4% for ages 41–42, and 9.2% for age > 42, which are very similar to our findings. The majority of embryo transfers which do not result in live birth are likely due to aneuploidy, which dramatically increases after age 37 [29–31]

Cumulative live birth rates per transfer with blastocysts available for ET or PGT-A

PGT-A allows the patient and physician to discern the ploidy status of the embryo with a high degree of certainty [14, 32, 33]. Euploid embryos have a very high live birth rate when reported per embryo transfer. For older patients, PGT-A thus substantially increases the live birth rate per embryo transfer when compared with untested embryos [3, 4], and our analysis supports this conclusion; in the present study, patients in the > 42 age group who utilized PGT-A and underwent an FET had a CLBR per embryo transfer of 50.2%, compared with 10.4% for untested embryos. This improved CLBR per embryo transfer was consistent for all ages, albeit with lesser improvement at younger ages. The rate of patients undergoing FET after PGT-A was expected, based on reported aneuploidy rates after blastocyst biopsy in IVF cycles [51] (Supplemental Table 2). Importantly, the present study demonstrates minimal to no benefit of PGT-A in patients aged < 35 who underwent embryo transfer, with a CLBR of 71.2% for the PGT-A group compared with 70.1% for the non-PGT-A group (Supplemental Table 3). A recent randomized controlled trial (STAR study) did not demonstrate an improvement in ongoing pregnancy rate when PGT-A was utilized in a good prognosis cohort undergoing IVF [10]. Specifically, Munné et al. [10] found that for patients ages 25–40 with normal ovarian reserve testing and who generated at least two blastocysts, PGT-A did not lead to an improvement in ongoing pregnancy rate. This study was controversial in its design, including its decision to exclude patients with zero or one blastocyst generated, but its overall results were confirmed by a published re-analysis of the STAR study, confirming that PGT-A does not favorably affect IVF outcomes by increasing pregnancy chances or reducing miscarriage risks [34].

Cumulative live birth rates per cycle start with blastocysts available for ET or PGT-A

Our study demonstrates that the subset of patients who had transferrable blastocysts, who utilized PGT-A, and had an FET, had the same or improved CLBR compared with untested embryos. However, this improvement was not seen when including cycles where a linked ET was not noted in the database. Indeed, it cannot be concluded that PGT-A improves CLBR per cycle start. Our results demonstrate a lower CLBR per cycle start in all age groups, except those aged ≥ 40, when comparing patients who utilized PGT-A to those who did not, when incorporating all cycles, including cycles which did not result in transferrable embryos. At age < 35, this analysis demonstrates a CLBR per cycle start of 70.1% for untested embryos versus 57.4% for those who utilized PGT-A. This is despite a reduced early pregnancy loss rate in the PGT-A group (11.3% for untested embryos versus 8.1% for the PGT-A group, respectively).

This finding stands in contrast to prior studies that have demonstrated equivalent CLBR for PGT-A and non-PGT-A cycles. For example, Neal et al. [6] analyzed 8998 patients, from 74 IVF centers, who underwent IVF with and without PGT-A. Their analysis demonstrated equivalent CLBR between the two groups per oocyte retrieval [6]. Similarly, a recent randomized controlled trial by Yan et al. [12] randomized 1212 patients between ages 20 and 37, who had successful blastocyst formation, to either conventional IVF or PGT-A and up to 3 subsequent FETs. They determined that there was no significant difference in CLBR between the two groups. PGT-A does not create additional euploid embryos available for transfer; rather, it prevents the transfer of known aneuploid embryos. As such, one would not necessarily expect a greater CLBR when using PGT-A. However, the finding of a lower CLBR per cycle start at most ages is a concerning finding, and calls into question the routine use of PGT-A at younger ages.

The reasons for the discrepancy in CLBR reported in the literature are currently a topic of active investigation. Simopoulou et al. [35] performed a meta-analysis of 11 randomized control trials and concluded that PGT-A did not improve live birth rates in patients under 35 years of age but did improve cumulative live birth rates in patients over 35 years of age. Cornelisse et al. [36] published a recent update of the Cochrane Review of PGT-A and concluded that in 25 years during which PGT-A has been in clinical use, no properly designed study has convincingly shown a clear benefit of PGT-A, including with respect to the cumulative live birth rate [37]. Recent studies have focused on the “embryo loss rate” from PGT-A, the rate at which embryos which may otherwise have resulted in pregnancies are not transferred, and which may be due to embryo injury during biopsy, embryo mosaicism, or incorrect diagnosis, amongst other possibilities [38, 39]. We agree that these reasons are plausible; in this study, differences in CLBR were noted when considering all cycles, not just those who had a transfer. In contrast, very similar CLBR were noted amongst patients who underwent ET in both the PGT-A and no PGT-A groups. This suggests that the insult may be occurring before the embryo transfer stage. Kang et al. [19] addressed embryo injury in their study of 274 PGT-A cycles and 863 non-PGT-A cycles, where they found no increase in CLBR at any age when using PGT-A. They determined that those who utilized PGT-A required 2.1 times more oocyte retrievals in order to achieve a clinical pregnancy and speculated that this may be due to intrinsic injury to the embryo itself during the biopsy process. In their reviews of the STAR study (Munné, et al 2019), Paulsen [40] and Schattman [41] noted reduced implantation rates amongst patients who utilized PGT-A, and suggested that this finding may be due to embryo injury at the time of biopsy or embryo mosaicism leading to embryos being discarded or not transferred. Although the statistical analysis of the STAR study has been questioned [34], the latter point regarding embryo mosaicism was certainly generally true during our study period (2014–2016) [42], and mosaicism may play a role in partially explaining our findings of a reduced CLBR due to non-transfer of mosaic embryos, especially in younger patients.

The management of embryos diagnosed as chromosomally mosaic via PGT-A has become a major focus of research in the past decade, with much debate centered on the interpretation of mosaic PGT-A results [43–45]. Mosaic embryos are noted when embryo biopsy demonstrates a chromosome copy number which is not consistent between biopsied cells. This may be due to true mosaicism but may also be due to inaccuracies in the testing platform [32, 42, 46]. Until recently, mosaic embryos were unlikely to be transferred [42]; however, emerging evidence has demonstrated healthy live births using mosaic embryos, especially amongst younger patients [47–50]. Using mathematical models, it has been suggested that these factors may lead to an embryo loss rate between 17.2 and 39.2% [39, 51–53]; in our analysis, we found a 12.7% reduction in CLBR in patients aged < 35, less than predicted by these models but still an important factor to account for when counseling patients about the use of PGT-A. Recent developments in non-invasive PGT technology may obviate some of these risks associated with embryo injury and mosaicism diagnosis and remain an area of active research [54–56].

Multiple gestations, preterm birth, and fetal birth weights from non-PGT and PGT-A cycles

An elevated incidence of twin gestation and preterm birth was noted amongst patients aged < 35, compared with other groups. This is likely due to the prevalence of multiple embryos being transferred, as elective single embryo transfer (eSET) had not yet become common practice in this age group at the time this data was collected. Indeed, during the data collection period, only 42.7% of patients aged < 35 underwent eSET, and the average number of embryos transferred was 1.5 [57]. Since that time, eSET is now recommended in most circumstances in this age group (5), and the singleton live birth rate has increased by 5.3% per ET, while the overall LBR has only increased from 3.1% per ET, suggesting an increase in eSET use [58]. However, we noted an increased incidence of preterm birth in the no PGT-A group at ages < 38, even when excluding non-singleton deliveries. This is consistent with a recent large study by Ying et al. [59], which evaluated a population undergoing eSET with either PGT-A or no PGT-A. Their study demonstrated an increased incidence of very preterm birth at < 28 weeks in the no PGT-A group, when compared to those who utilized PGT-A. However, a recent database study by Mejia et al. [13] demonstrated no increased risk of preterm birth amongst singleton births utilizing PGT-A vs no PGT-A. Both of these studies, as well as our study, utilized a database with delivery data generally occurring between the years 2014–2017; it is possible that more recent data may be utilized to further elucidate this relationship and further research on this topic is necessary.

Our findings of lower multiple gestation rates in the PGT-A group versus the non-PGT group are consistent with prior studies. For example, Munné et al. [10], in a randomized controlled trial of PGT-A vs no PGT-A with ESET in a favorable prognosis population, demonstrated no difference in rates of biochemical pregnancy or clinical miscarriage between the two groups. Their miscarriage rates were greater in the PGT-A group (9.9%) and lower in the no PGT-A group (9.6%) than in our study. Overall, ASRM considers PGT-A to hold promise as a tool to possibly reduce the rate of multiple gestations in IVF and our data support that assessment [14].

PGT-A has been purported to reduce the risk of early pregnancy loss. In our study, we noted a 7% early pregnancy loss rate in those undergoing PGT-A, compared with 12.5% for those who did not utilize PGT-A. Forman et al. [60] previously demonstrated a 10.5% loss rate when transferring euploid embryos, compared with a 28.5% for untested embryos, a larger differential than we observed in our study that may be associated with their smaller sample size (n = 140), and overall older population utilizing PGT-A (mean age 37.3). A cost-benefit analysis of that study by Neal et al. [6] demonstrated that PGT-A decreases time to pregnancy, in part because of the lower rate of pregnancy loss. Based on studies by us and others, we conclude that pregnancy loss rates are lower in those using PGT-A on a per-embryo-transfer basis.

We found no difference in the secondary sex ratio between the PGT-A and no PGT-A groups, with explicit exclusion of elective sex selection cycles. A recent SART database study examining 88,957 live births indicated that, amongst untested embryos, the ratio of male to female live births was 1.05:1 (similar to the overall rate of live-born persons in the USA) [61]. This ratio increased to 1.15:1 for cycles using PGT-A, suggesting the presence of male sex preference [61]. Our data cannot refute the possibility of male sex preference in PGT-A cycles, as not all cycles (including those for elective sex selection) were included.

Our study demonstrated a lower rate of low birth weight and very low birth weight infants in most age groups when using PGT-A. These results contrast with recent studies. For example, a recent meta-analysis by Zheng et al. [62] evaluating 3682 PGT-A deliveries and 127,719 non-PGT-A IVF/ICSI deliveries demonstrated no difference in LBW between the two groups. However, another recent meta-analysis by Hou et al. [63] of 54,294 PGT-A deliveries and 731,151 non-PGT-A IVF/ICSI deliveries demonstrated no difference in LBW between the two groups, but did demonstrate a reduced rate of VLBW deliveries in the non-PGT-A group. It is possible that the reduced incidence of LBW and VLBW deliveries in our study is due to the elevated rate of multiple gestations in the non-PGT-A group; however, we found that this trend continued to be significant at ages < 40, even when excluding non-singleton deliveries. Further research on this topic is required.

The primary strength of this study includes a large database of patients across the USA that underwent IVF; all ages, cycle types, diagnoses, and clinical settings were included. The large sample size of this study, 133,494 cycles, obviated the ability of small outliers to confound our statistical analysis. This study has several limitations. The primary limitation of this study is its retrospective nature, limiting its ability to be used to demonstrate causal relationships. The dataset relies on self-reporting and input of data at fertility centers and is thus subject to error. Several cycles had missing or outlier data points, and a large number of frozen embryo transfer cycles had incomplete or missing data regarding the number of embryos transferred during those cycles, limiting our analysis. However, given the size and breadth of the dataset, we believe that these issues were unlikely to influence the overall results. Data collected during the study period, 2014–2016, utilized technologies other than next-generation sequencing (NGS), whereas PGT-A chromosome analysis is now generally performed using solely NGS. The technology involved in PGT-A has been rapidly changing over the past 10 years. However, we believe that any changes in the technology will not have an outsized effect on our results. Indeed, with the increase in mosaic reporting with NGS compared with prior technologies, and subsequent failure to transfer mosaic embryos, this may result in an even further decrease in CLBR if this analysis was conducted utilizing today’s methods. Data regarding whether or not an embryo transferred after PGT-A was euploid, mosaic, or aneuploid was not available in this dataset. However, the vast majority of embryos transferred after PGT-A are euploid. Given our sample size, we do not believe a small minority of clinics transferring mosaic or aneuploid embryos would substantially affect the results. Additionally, we were unable to determine which days biopsies for PGT were performed at the cleavage or blastocyst stage. The cleavage-stage biopsy is associated with impaired blastulation and reduced pregnancy rate [64, 65]; however, the vast majority of biopsies were being performed at the blastocyst stage at the time of data collection. We excluded fresh embryo transfers in cycles where PGT-A was also performed; this could induce bias by excluding cycles which could result in pregnancy, which may affect the overall CLBR for PGT-A cycles. For most practices, however, PGT-A of blastocysts is combined with FET; therefore, only frozen-thawed cycles could be included in the study group. We noted a smaller sample size in the older age groups, compared with younger age groups, and thus there was less power to detect a PGT-A effect in the older age groups. Our goal was to present live birth rates for PGT and non-PGT within each age stratum and assess the stratum-specific differences. A statistically significant interaction effect between age and PGT status was observed (p-value < 0.001) as well as a statistically significant difference between the youngest age group and the oldest with respect to the PGT effect (p-value < 0.0001).

Our study does not include the number of embryos transferred in each group, as our dataset only contains complete information regarding the number of embryos transferred during fresh ETs, and a large proportion of FETs (both PGT-A and non-PGT-A) had missing or incomplete data. Additionally, the focus of this analysis is not whether PGT-A reduces time to pregnancy and live birth, but whether PGT-A affects CLBR overall, regardless of how many transfers are performed. We believe that a future analysis using a newer dataset, accounting for the number of embryos transferred, and specifically eSET, would be valuable. SART CORS allows IVF cycles to be categorized as PGT-A “all,” “some,” or “none.” Cycles which were noted to have “some” PGT-A performed were included in the PGT-A group in our analysis in order to capture patients who may have had PGT-A performed on a certain number of embryos up to their plan limit, and then cryopreserved the remainder of their embryos untested. These patients fit into the dichotomous relationship this study is exploring: whether or not to perform PGT-A at all, at a given age. If PGT-A was performed, this group only includes patients who did not desire to transfer an untested embryo, given that those who did a fresh ET in addition to PGT-A were excluded. The number of cancelled cycles due to poor response in each group was not included in the analysis, as the primary purpose of this study is to analyze the inflection point of whether or not to utilize PGT-A in the setting of blastocyst formation, not an intent to treat based on starting an IVF cycle with the intent to utilize PGT-A or not. Thus, only cycles which resulted in blastocyst formation or failed to form blastocyst were included. In a cancelled cycle, PGT-A is not able to be performed; the true intent of the patient, whether or not they intended to perform PGT-A, is not able to be ascertained.

Finally, we made assumptions regarding the outcome of PGT-A cycles which did not result in an embryo transfer. Specifically, we assumed that cycles in which no embryo was transferred were due to the absence of transferrable embryos and were thus characterized as negative cycles. If a cycle had blastocysts biopsied for PGT-A, was explicitly not for embryo banking, and did not have a transfer, then that is, by definition, a lack of a live birth. The goal of our study was to analyze the value of performing PGT-A in the setting of having blastocysts available for either embryo transfer of an untested embryo or for PGT-A, and to evaluate how performing PGT-A may affect CLBR. We explicitly excluded embryo banking cycles, so that everyone included in the study was undergoing IVF in order to achieve pregnancy. However, we cannot exclude other possibilities as reasons for the lack of a documented ET during the study period, including data entry errors, failed thaw at the time of FET, delayed ET or embryo batching, dissolution of the intended parent relationship, transfer of embryos to another facility, or other external factors.

This analysis primarily evaluated patients who had transferrable embryos and either underwent a transfer or underwent PGT-A. If they did PGT-A and did not have a transfer, this was likely due to the lack of a euploid embryo. Including patients who underwent a retrieval, had blastocysts cryopreserved, did not have PGT-A performed, and also did not opt for a transfer would introduce bias regarding their motivations for not having a transfer. For that reason, we have not included this group of patients in our analysis, as we feel that it would introduce bias and speculation regarding this concern. Although we also specifically excluded embryo banking cycles, it is possible that after creating transferrable embryos, patients decided to not undergo an embryo transfer during the study period. The “multiple cycles for embryo banking” option was a relatively new option in the SART CORS database during the timeframe of this study and may not have been appropriately utilized. We attempted to address this by limiting cycle starts to 2014–2015, with outcomes extending into 2016 to allow for ample time for multiple embryo transfers. Nevertheless, it is possible that some cycles were mischaracterized as negative cycles, when in reality patients simply did not have an embryo transfer and outcome during that timeframe. However, we believe this number to be small, and, given the large size of the dataset and statistical power utilized in this study, unlikely to impact the overall results.

In our study, we demonstrated increased cumulative live birth rates per embryo transfer in older patients with PGT-A, and reduced pregnancy loss rates with PGT-A on a per-embryo-transfer basis. These major findings in our study are in concordance with the meta-analysis findings by Simopoulou et al. [35], who reported results from 11 randomized controlled studies in the literature. The conclusion of the meta-analysis was that PGT-A did not improve live birth rates in general per patient but did improve miscarriage rates; an improvement in live birth rates was seen in patients >35 years old. The lack of improvement on live birth rates following PGT-A in the pooled results is in agreement with previous recent systemic reviews and meta-analyses, both per patient and per embryo transfer. Finally, these authors report a high level of heterogeneity in the studies and conclude that the data quality is low or very low.

In contrast, a recent and controversial registry study by Sanders et al. [66] showed improved live birth rates per embryo transfer and per cycle start with PGT-A compared to no PGT-A [67]. It is to be expected that when studies use embryo transfer as the denominator instead of per patient or per cycle, superior outcomes are seen using PGT-A after the first transfer which may falsely construe PGT as producing superior outcomes. Pregnancy per transfer as an outcome measure favors PGT-A and does not reflect the totality of the literature [37]. However, the improved cumulative live birth rates per cycle start seen by Sanders et al. [66] highlights why there are conflicting opinions in the field on the utility of PGT-A. We attempt to draw balanced conclusions from our study as it contributes to the literature.

Conclusion

Here, we have utilized registry data to investigate the relationship between PGT-A and CLBR. Our analysis demonstrates no clear improvement to CLBR per cycle start when utilizing PGT-A. Indeed, amongst the youngest patients (age < 35), not only does there appear to be no benefit to PGT-A, but there appears to be a considerable reduction in CLBR per cycle start, the first time these results have been demonstrated using a large database. For those aged > 42, a slightly higher CLBR is seen in PGT-A cycles, although this was not statistically significant. Importantly, this is the outcome being observed in our study, and we are not making estimates regarding the underlying factors that might result in the outcomes observed. This analysis also cannot quantify the utility of PGT-A on an individual clinic level, as some clinics may have greater or lesser blastocyst development or proficiency in PGT-A. Our results are evaluating the average of all clinics reporting to SART CORS, and individual clinics should be encouraged to look at their own data to determine if PGT-A is beneficial or not to their patients. We speculate that in some cases, poor morphology of available embryos might result in a preference for ET rather than PGT-A. Additionally, the increased CLBR in older patients using PGT-A may be related to patients with greater ovarian reserve electing to have PGT-A testing instead of ET, leading to a greater number of blastocysts available for biopsy and a greater probability of having euploid embryos available for ET. This, and other factors such as auto-immune disorders, certain male factor infertility, and certain lifestyle factors, all of which can contribute to higher rates of aneuploidy, should be considered in addition to maternal age when counseling patients about PGT-A. The high rate of twins in the youngest patients reinforces current recommendations for eSET under most circumstances, and our findings also support prior work which has demonstrated PGT-A is associated with a reduced incidence of multiple gestations, early pregnancy loss, and LBW and VLBW infants, compared with non-PGT-A cycles. Patient counseling regarding the use of PGT-A should be age-dependent and individualized.

There have been calls for re-evaluation or even repeal of widespread PGT-A usage. Mastenbroek et al. [37] point out that PGT-A usage decreased the number of women undergoing embryo transfer, and results that are reported on a per-transfer basis are not informative for infertile couples wondering whether or not to add PGT-A to their cycle. These authors and others advocate for responsible innovation supported by high-quality data, which is not the case for PGT-A [37, 68]. We conclude that PGT-A may show utility in patients of advanced maternal age, and that PGT-A is associated with lower miscarriage rates. We recommend cumulative live birth rate per cycle vs. first transfer live birth rate as the most appropriate patient-centered outcome measure for determining the utility of PGT-A. We recommend that patients be counseled on the utility of PGT-A not only based on maternal age, but also on any likely miscarriage benefit.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

SART wishes to thank all of its members for providing clinical information to the SART CORS database for use by patients and researchers. Without the efforts of our members, this research would not have been possible.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Scott RT, Jr, Upham KM, Forman EJ, Zhao T, Treff NR. Cleavage-stage biopsy significantly impairs human embryonic implantation potential while blastocyst biopsy does not: a randomized and paired clinical trial. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:624–30. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Consortium EP, Group SI-EBW, Kokkali G, Coticchio G, Bronet F, Celebi C et al. ESHRE PGT Consortium and SIG Embryology good practice recommendations for polar body and embryo biopsy for PGT. Hum Reprod Open. 2020;hoaa020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Forman EJ, Hong KH, Ferry KM, Tao X, Taylor D, Levy B, et al. In vitro fertilization with single euploid blastocyst transfer: a randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:100–7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott RT, Jr, Upham KM, Forman EJ, Hong KH, Scott KL, Taylor D, et al. Blastocyst biopsy with comprehensive chromosome screening and fresh embryo transfer significantly increases in vitro fertilization implantation and delivery rates: a randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.. Guidance on the limits to the number of embryos to transfer: a committee opinion. Fertility and sterility 2017;107:901-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Neal SA, Morin SJ, Franasiak JM, Goodman LR, Juneau CR, Forman EJ, et al. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy is cost-effective, shortens treatment time, and reduces the risk of failed embryo transfer and clinical miscarriage. Fertil Steril. 2018;110:896–904. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle N, Gainty M, Eubanks A, Doyle J, Hayes H, Tucker M, et al. Donor oocyte recipients do not benefit from preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy to improve pregnancy outcomes. Hum Reprod. 2020;35:2548–55. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kemper JM, Wang R, Rolnik DL, Mol BW. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy: are we examining the correct outcomes? Hum Reprod. 2020;35:2408–12. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy LA, Seidler EA, Vaughan DA, Resetkova N, Penzias AS, Toth TL, et al. To test or not to test? A framework for counselling patients on preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) Hum Reprod. 2019;34:268–75. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munné S, Kaplan B, Frattarelli JL, Child T, Nakhuda G, Shamma FN, et al. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy versus morphology as selection criteria for single frozen-thawed embryo transfer in good-prognosis patients: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:1071–9.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.07.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitney JB, Schiewe MC, Anderson RE. Single center validation of routine blastocyst biopsy implementation. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:1507–13. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0792-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan J, Qin Y, Zhao H, Sun Y, Gong F, Li R, et al. Live Birth with or without Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Aneuploidy. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2047–58. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mejia RB, Capper EA, Summers KM, Mancuso AC, Sparks AE, Van Voorhis BJ. Cumulative live birth rate in women aged ≤37 years after in vitro fertilization with or without preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy: a Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinic Outcome Reporting System retrospective analysis. F S Rep. 2022;3:184–91. doi: 10.1016/j.xfre.2022.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.. The use of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A): a committee opinion. Fertility and sterility 2018;109:429-36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Twisk M, Mastenbroek S, Hoek A, Heineman MJ, van der Veen F, Bossuyt PM, et al. No beneficial effect of preimplantation genetic screening in women of advanced maternal age with a high risk for embryonic aneuploidy. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2813–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sacchi L, Albani E, Cesana A, Smeraldi A, Parini V, Fabiani M, et al. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy improves clinical, gestational, and neonatal outcomes in advanced maternal age patients without compromising cumulative live-birth rate. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36:2493–504. doi: 10.1007/s10815-019-01609-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haviland MJ, Murphy LA, Modest AM, Fox MP, Wise LA, Nillni YI, et al. Comparison of pregnancy outcomes following preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy using a matched propensity score design. Hum Reprod. 2020;35:2356–64. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verpoest W, Staessen C, Bossuyt PM, Goossens V, Altarescu G, Bonduelle M, et al. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy by microarray analysis of polar bodies in advanced maternal age: a randomized clinical trial. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:1767–76. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang HJ, Melnick AP, Stewart JD, Xu K, Rosenwaks Z. Preimplantation genetic screening: who benefits? Fertil Steril. 2016;106:597–602. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.. What is SART? In: Technology SfAR, ed. Official Website, Society for Assisted Reproducive Technology, 2020.

- 21.Toner JP, Coddington CC, Doody K, Van Voorhis B, Seifer DB, Ball GD, et al. Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology and assisted reproductive technology in the United States: a 2016 update. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:541–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knudtson JF, Robinson RD, Sparks AE, Hill MJ, Chang TA, Van Voorhis BJ. Common practices among consistently high-performing in vitro fertilization programs in the United States: 10-year update. Fertil Steril. 2022;117:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assisted Reproductive Technology Fertility Clinic Success Rates Report [Internet]. 2017;Atlanta, GA: 2019. 2019.

- 24.. Female age-related fertility decline. Committee Opinion No. 589. Fertility and sterility 2014;101:633-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Munné S, Alikani M, Tomkin G, Grifo J, Cohen J. Embryo morphology, developmental rates, and maternal age are correlated with chromosome abnormalities. Fertil Steril. 1995;64:382–91. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)57739-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pal L, Santoro N. Age-related decline in fertility. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32:669–88. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8529(03)00046-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reig A, Franasiak J, Scott RT, Jr, Seli E. The impact of age beyond ploidy: outcome data from 8175 euploid single embryo transfers. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:595–602. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01739-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldman RH, Farland LV, Thomas AM, Zera CA, Ginsburg ES. The combined impact of maternal age and body mass index on cumulative live birth following in vitro fertilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:617. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ginsburg ES, Racowsky C. Chapter 31 - Assisted Reproduction. In: Strauss JF, Barbieri RL, editors. Yen & Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology. 7. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2014. pp. 734–73.e12. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franasiak JM, Forman EJ, Hong KH, Werner MD, Upham KM, Treff NR, et al. The nature of aneuploidy with increasing age of the female partner: a review of 15,169 consecutive trophectoderm biopsies evaluated with comprehensive chromosomal screening. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:656–63.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Devesa M, Tur R, Rodríguez I, Coroleu B, Martínez F, Polyzos NP. Cumulative live birth rates and number of oocytes retrieved in women of advanced age A single centre analysis including 4500 women ≥38 years old. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:2010–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott RT, Jr, Galliano D. The challenge of embryonic mosaicism in preimplantation genetic screening. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:1150–2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.. Clinical management of mosaic results from preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) of blastocysts: a committee opinion. Fertility and sterility 2020;114:246-54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Orvieto R, Gleicher N. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A)-finally revealed. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:669–72. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01705-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simopoulou M, Sfakianoudis K, Maziotis E, Tsioulou P, Grigoriadis S, Rapani A, et al. PGT-A: who and when? Α systematic review and network meta-analysis of RCTs. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:1939–57. doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02227-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cornelisse S, Zagers M, Kostova E, Fleischer K, van Wely M, Mastenbroek S. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies (abnormal number of chromosomes) in in vitro fertilisation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;9:Cd005291. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005291.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mastenbroek S, de Wert G, Adashi EY. The imperative of responsible innovation in reproductive medicine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2096–100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2101718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffin DK, Ogur C. Chromosomal analysis in IVF: just how useful is it? Reproduction. 2018;156:F29–F50. doi: 10.1530/REP-17-0683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pagliardini L, Viganò P, Alteri A, Corti L, Somigliana E, Papaleo E. Shooting STAR: reinterpreting the data from the 'Single Embryo TrAnsfeR of Euploid Embryo' randomized clinical trial. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;40:475–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paulson RJ. Outcome of in vitro fertilization cycles with preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies: let’s be honest with one another. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:1013–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schattman GL. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy: it’s deja vu all over again! Fertil Steril. 2019;112:1046–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.08.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sachdev NM, Maxwell SM, Besser AG, Grifo JA. Diagnosis and clinical management of embryonic mosaicism. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Albertini DF. Mired in mosaicism: the perils of genome trivialization. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:1417–8. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0829-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Esfandiari N, Bunnell ME, Casper RF. Human embryo mosaicism: did we drop the ball on chromosomal testing? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:1439–44. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0797-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scott RT., Jr Introduction: subchromosomal abnormalities in preimplantation embryonic aneuploidy screening. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:4–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Treff NR, Franasiak JM. Detection of segmental aneuploidy and mosaicism in the human preimplantation embryo: technical considerations and limitations. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L, Wei D, Zhu Y, Gao Y, Yan J, Chen ZJ. Rates of live birth after mosaic embryo transfer compared with euploid embryo transfer. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36:165–72. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1322-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kahraman S, Cetinkaya M, Yuksel B, Yesil M, Pirkevi Cetinkaya C. The birth of a baby with mosaicism resulting from a known mosaic embryo transfer: a case report. Hum Reprod. 2020;35:727–33. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greco E, Minasi MG, Fiorentino F. Healthy babies after intrauterine transfer of mosaic aneuploid blastocysts. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2089–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1500421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Victor AR, Tyndall JC, Brake AJ, Lepkowsky LT, Murphy AE, Griffin DK, et al. One hundred mosaic embryos transferred prospectively in a single clinic: exploring when and why they result in healthy pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 2019;111:280–93. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paulson RJ. Preimplantation genetic screening: what is the clinical efficiency? Fertil Steril. 2017;108:228–30. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orvieto R, Gleicher N. Should preimplantation genetic screening (PGS) be implemented to routine IVF practice? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:1445–8. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0801-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tortoriello DV, Dayal M, Beyhan Z, Yakut T, Keskintepe L. Reanalysis of human blastocysts with different molecular genetic screening platforms reveals significant discordance in ploidy status. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:1467–71. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0766-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yeung QSY, Zhang YX, Chung JPW, Lui WT, Kwok YKY, Gui B, et al. A prospective study of non-invasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies (NiPGT-A) using next-generation sequencing (NGS) on spent culture media (SCM) J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36:1609–21. doi: 10.1007/s10815-019-01517-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang L, Bogale B, Tang Y, Lu S, Xie XS, Racowsky C. Noninvasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy in spent medium may be more reliable than trophectoderm biopsy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:14105–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1907472116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rubio C, Rienzi L, Navarro-Sanchez L, Cimadomo D, Garcia-Pascual CM, Albricci L, et al. Embryonic cell-free DNA versus trophectoderm biopsy for aneuploidy testing: concordance rate and clinical implications. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:510–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Center for Disease Control and Prevention, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, and Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Assisted Reproductive Technology Success Rates: National Summary and Fertility Clinic Reports. Washington, DC: US Dept. of Health and Human Services. 2016;2018. 2018.

- 58.Center for Disease Control and Prevention, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, and Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Assisted Reproductive Technology Success Rates: National Summary and Fertility Clinic Reports. Washington, DC: US Dept. of Health and Human Services. 2018;2020. 2020.

- 59.Ying LY, Sanchez MD, Baron J, Ying Y. Preimplantation genetic testing and frozen embryo transfer synergistically decrease very pre-term birth in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization with elective single embryo transfer. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:2333–9. doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02266-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forman EJ, Tao X, Ferry KM, Taylor D, Treff NR, Scott RT., Jr Single embryo transfer with comprehensive chromosome screening results in improved ongoing pregnancy rates and decreased miscarriage rates. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1217–22. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eaton JL. State-mandated in vitro fertilization coverage and utilization of preimplantation genetic testing: skewing the sex ratio. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:498–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng W, Yang C, Yang S, Sun S, Mu M, Rao M, et al. Obstetric and neonatal outcomes of pregnancies resulting from preimplantation genetic testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2021;27:989–1012. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmab027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hou W, Shi G, Ma Y, Liu Y, Lu M, Fan X, et al. Impact of preimplantation genetic testing on obstetric and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2021;116:990–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bar-El L, Kalma Y, Malcov M, Schwartz T, Raviv S, Cohen T, et al. Blastomere biopsy for PGD delays embryo compaction and blastulation: a time-lapse microscopic analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:1449–57. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0813-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Holden EC, Kashani BN, Morelli SS, Alderson D, Jindal SK, Ohman-Strickland PA, et al. Improved outcomes after blastocyst-stage frozen-thawed embryo transfers compared with cleavage stage: a Society for Assisted Reproductive Technologies Clinical Outcomes Reporting System study. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(89–94):e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sanders KD, Silvestri G, Gordon T, Griffin DK. Analysis of IVF live birth outcomes with and without preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A): UK Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority data collection 2016–2018. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:3277–85. doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02349-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Griffin DK. Why PGT-A, most likely, improves IVF success. Reprod Biomed Online. 2022;45:633–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2022.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gleicher N, Barad DH, Patrizio P, Orvieto R. We have reached a dead end for preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy. Hum Reprod 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.