Abstract

Objective:

Based on the results of previous studies, the effects of N. sativa on some of the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease's (NAFLD) biomarkers were positive; however, there were conflicting results regarding other variables. Therefore, the present systematic review of clinical trials was designed to clarify whether N. sativa effectively prevents the progression of NAFLD.

Materials and Methods:

A search of four databases (Scopus, PubMed, Medline, and Google scholar) was conducted to identify the clinical trials that assessed the effects of N. sativa supplementation on NAFLD. The outcome variables of interest were biomarkers of hepatic steatosis, liver enzymes, insulin resistance, and inflammation.

Results:

Overall, four randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were included. In three studies, hepatic steatosis grade decreased significantly after N. sativa supplementation. Serum levels of liver enzymes reduced significantly in three of four included trials. In the only study that examined the effect of N. sativa on insulin resistance parameters, all variables related to this factor were significantly reduced. In two included studies that measured biomarkers of inflammation, the serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and interleukin 6 (IL-6) decreased significantly after intaking N. sativa supplements.

Conclusion:

Although the efficacy of N. sativa on liver enzymes and the grade of hepatic steatosis was reported in some of the included studies, more well-designed clinical trials are needed to determine the definitive effects of N. sativa on NAFLD. The present study provides suggestions that help to design future studies in this field.

Key Words: Nigella sativa, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Clinical trials, Systematic review

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is excessive fat accumulation in the liver without alcohol use (Mokhtari et al., 2017 ▶). NAFLD prevalence in the Middle East and Africa is 31.8 and 13.5%, respectively (Younossi et al., 2019 ▶). NAFLD includes various stages such as liver steatosis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), liver fibrosis, and cirrhosis. The fundamental risk factors of heart disease, such as hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diabetes mellitus, are related to the pathogenesis of NAFLD (Cicero et al., 2018 ▶). Weight loss, adherence to a healthy diet, and increasing physical activity are the only established strategies to prevent and treat NAFLD (Argo et al., 2009 ▶; Keating et al., 2012 ▶; Lindenmeyer and McCullough, 2018 ▶; Mummadi et al., 2008 ▶; Promrat et al., 2010 ▶). However, research is ongoing to find drugs or supplements that may help in managing NAFLD (Cicero et al., 2012 ▶; Hashempur et al., 2015 ▶; Hosseini et al., 2016 ▶; Samani et al., 2016 ▶; Sharifi and Amani, 2019 ▶; Sharifi et al., 2014 ▶).

Recently, herbal medicines have gained attention as adjuvant therapies in various diseases related to metabolic syndrome, such as diabetes (Yeh et al., 2003 ▶), hypertension (Chen et al., 2015 ▶), obesity (Hasani-Ranjbar et al., 2009 ▶; Sui et al., 2012 ▶), and hyperlipidemia (Hasani-Ranjbar et al., 2010 ▶). This is due to the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of herbal compounds that allow them to prevent and reduce the complications of chronic diseases (Ben El Mostafa and Abdellatif, 2020 ▶). One of the herbs that have a beneficial effect on metabolic syndrome components such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and insulin resistance is Nigella sativa (N. sativa)(Benhaddou-Andaloussi et al., 2011 ▶; Muneera et al., 2015 ▶; Sahebkar et al., 2016 ▶). N. sativa is an annual flowering plant in the family Ranunculaceae and is native to South and West Asia. N. sativa is also known by other names such as black cumin, fennel flower, black seeds, nutmeg flower, black caraway, and kalonji (Hussain et al., 2017 ▶). N. sativa seed oil and powder have been consumed for a long time for treating various diseases (Hussain et al., 2017 ▶). In addition, N. sativa has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and anti-bacterial properties that have advocated researchers to examine its treatment effects on NAFLD (Amizadeh et al., 2020 ▶; Ben El Mostafa and Abdellatif, 2020 ▶; Hadi et al., 2016 ▶). Several randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have been conducted until now to evaluate the effects of N. sativa on fatty liver disease (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Darand et al., 2019b ▶; Hosseini et al., 2018 ▶; Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Khonche et al., 2019 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶).

In these studies (Darand et al., 2019b ▶; Hosseini et al., 2018 ▶; Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Khonche et al., 2019 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶), the effects of N. sativa supplementation on various factors such as the grade of fatty liver and steatosis, liver enzymes, biomarkers of glucose metabolism, inflammatory factors, lipid profile, anthropometric indices, and blood pressure have been evaluated. However, there are conflicting results on the effects of N. sativa regarding some of the NAFLD biomarkers. Therefore, the present systematic review of clinical trials was designed with the following objectives: 1. To discuss whether N. sativa effectively prevents steatosis and fibrosis progression in NAFLD; 2. To compare the findings of the clinical trials in terms of the effectiveness of N. sativa on the secondary outcomes of NAFLD such as fasting blood glucose (FBG), serum insulin, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), lipid profiles, blood pressure, inflammatory biomarkers and anthropometric indices; and 3. To provide suggestions for future well-designed studies in this field.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

A systematic review of the literature was conducted for uncontrolled clinical trials, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and non-randomized interventions, which indicate the results of N. sativa supplementation on hepatic steatosis, liver enzymes, lipid profiles, and blood sugar or insulin sensitivity in patients with NAFLD. It was considered sufficient for studies to report the NAFLD diagnostic methods based on one or more of the following: (1) ultrasound; (2) blood concentrations of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST); (3) histological examination of biopsies; (4) computed tomography (CT); and (5) proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS).

The primary outcomes of interest included changes in serum levels of liver enzymes and hepatic steatosis and fibrosis assessed by liver biopsy, CT, histological indicators of inflammation, ultrasound, and MRS. Fasting blood glucose (FBG), serum insulin, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA‐IR), lipid profiles, blood pressure, inflammatory biomarkers, and anthropometric indices were considered the secondary outcomes.

A systematic literature search was conducted separately by two researchers (AM & AE), from inception to January 21-2021, to assess and select studies of N. sativa supplementation on NAFLD.

Some databases, including Scopus, PubMed (Medline), and Google Scholar, were applied to perform a complete search. Our search terms were: "non-alcoholic fatty liver" or "NAFLD" or "non-alcoholic steatohepatitis" or "non-alcoholic fatty liver" or "non-alcoholic steatosis" or "non-alcoholic liver steatosis" or "non-alcoholic steatohepatitis" or "non-alcoholic steatosis" or "non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis" or "non-alcoholic liver steatosis" or "non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis" AND "black seed" or "Nigella sativa" or "black cumin" or "black seed oil" or "thymoquinone" AND "randomized controlled trial" or "controlled clinical trial" or "randomized" or "trial" or "placebo."

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Researchers separately determined the eligibility of studies to be included in the review. Included studies were trials involving N. sativa seed powder or N. sativa seed oil versus placebo; N. sativa seed powder and lifestyle modification versus placebo and lifestyle modification; N. sativa combination use with another supplement versus placebo. Additional inclusion criteria were: (i) the study population included the patients with NAFLD and/or NASH; (ii) Supplementation of N. sativa seed powder or N. sativa seed oil for intervention; (iii) Hepatic steatosis (assessed by ultrasound or Fibroscan examination), liver enzymes, and histological indicators of inflammation and fibrosis had to be a primary or secondary outcome; (iv) the study was performed in subjects ≥ 18 years of age; and (v) published in English. Studies that included the participants in whom NAFLD was induced by excess alcohol intake, drugs, total parenteral nutrition, viruses, or genetic disorders, were excluded. In addition, study types such as systematic review, meta-analysis, narrative review, and animal studies were excluded. Bibliographic references of searched articles were also examined to find additional studies.

Data items

The data items that were considered in this study included: study design; country; sex; age; randomization and blinding; comparability of groups at baseline; types and doses of N. sativa supplementation; intervention protocol; duration of the study; assessment methods of hepatic steatosis; measures of liver enzymes; glucose metabolism biomarkers (FBG, serum insulin, and HOMA-IR), lipid profiles, blood pressure, inflammatory biomarkers, and anthropometric indices.

Data extraction

Authors independently performed data extraction from RCTs and then, discussed any differences in data extraction and eventually resolved them. Itemized Tables were applied to record relevant data from the reports. Results were converted to the same units to simplify the comparison among studies. In addition, the values of changes from baseline were converted to percentages.

Study quality assessment

Two authors (AM and AE) independently assessed the quality of selected studies using the Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias (RoB2) tool (Sterne et al., 2019 ▶). A third researcher (NS) judged any disagreement. This tool examines possible bias from randomization, deviation from intended intervention, measurement of outcome, missing outcome data, and the selection of reported results. The overall quality of each study was considered low risk of bias, some concerns of bias, or high-risk of bias.

Results

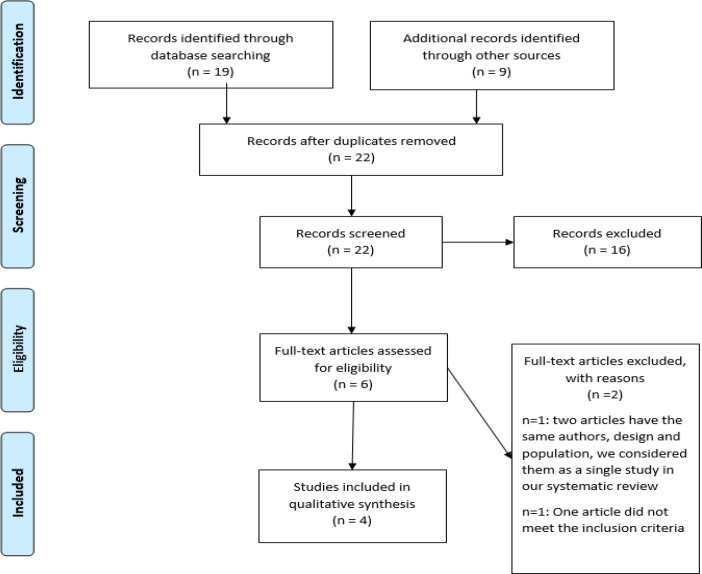

Initially, 28 articles were found by searching different databases. After removing duplicate reports, 22 studies were evaluated. Then, sixteen studies were excluded in the abstract screening stage because some did not meet the criteria for this study or the full texts were not accessible.

Finally, the full texts were read for inclusion criteria and one study was excluded from the eligibility stage of this systematic review (Hosseini et al., 2018) (Figure 1). In the final judgment of RCTs, four studies with 324 patients were included (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Darand et al., 2019b ▶; Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Khonche et al., 2019 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the process for inclusion of studies

Table 1.

Studies that evaluated the effect of N. sativa supplementation on NAFLD outcomes

| Author, year | Country | Design | Total Sample Size (M/F) | Study population | Age (yrs) | BMI (Kg/m 2 ) | Intervention and study groups | Duration(wks) | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darand et al., 2019 ▶ (24,25) | Iran | RCT | 43 (21/22) | Patients with NAFLD |

48.86±12.74 |

G1: 32.05± 4.17 G2: 31.7±3.54 |

G1:

N. sativa seed powder (2 gr/d) +lifestyle modification G2: Placebo (rice starch) +lifestyle modification |

12 | ALT, AST, GGT, BMI, bodyweight, WC,WHR, hs-CRP,TNF-α,NF-κB, Fibrosis and steatosis grade (FibroScan), TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, TC, Serum glucose, Insulin, HOMA-IR, QUICKI |

Steatosis ↓28% Serum glucose↓8%, serum insulin↓31%, HOMA‐IR↓36%, Steatosis % ↓ 28%, QUICKI↑9% TNF-α ↓20% Non-significant changes in lipid profile, liver enzymes, Fibrosis score |

| Khonche et al., 2019 ▶ (23) | Iran | RCT | 120 (62/58) | Patients with NAFLD |

46.64±12.18 | 27±2.1 |

G1:

N. sativa seed oil (2.5 ml every 12 hr) G2: Placebo |

12 | AST, ALT, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, Grade of hepatic steatosis(ultrasound) |

ALT↓33%, AST↓30%, LDL-C↓15%, TG↓13%, HDL-C↑9% ↓ steatosis grade |

| Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶ (26) | Iran | RCT | 44 (29/15) | Patients with NAFLD |

39±5.37 |

G1: 27.59±2.83 G2: 27.67±4.37 |

G1:

N. sativa seed oil (1gr once a day) G2: Placebo (paraffin oil 1gr once a day) |

8 | SBP, DBP, FBS, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, VLDL-C, Insulin, AST, ALT, GGT, hs-CRP,TNF-α,IL-6,WC,WHR,BMI,body weight | AST↓30% , ALT↓19%, FBG↓7%, LDL↓18%, VLDL↓11%, TG↓19%, TC↓14%, HDL-C↑31% hs-CRP↓13%, , TNF-α↓20%, IL-6↓23% Non-significant changes in any of the outcomes' measures |

| Hussain et al., 2017 ▶ (22) | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial | 70 (44/26) | Patients with NAFLD |

38±8.75 |

G1: 29.06±4.6 G2: 28.18±3.8 |

G1:

N. sativa seed powder(1 gr twice/day) G2: Placebo (micro crystalline cellulose) |

12 | Body weight, BMI, ALT, AST, GGT, Fatty liver Grading(ultrasound) | ALT↓32%, AST↓32% ↓ Fatty liver Grading Body weight ↓11%, BMI↓9%, Non-significant Changes in GGT |

Data are mean±standard deviation usually rounded to the nearest full figure; Sample size reflects those included in the final analysis. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase ; BMI, body max index (kg/m2); d, day(s); DBP, diastolic blood pressure; F, female; FBG, fasting blood glucose; G1, group1; G2, group 2; GGT, gamma glutamyltransferase; h, hour; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment; HDL-c, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; HS, hepatic steatosis; hs-CRP, high-sensitive C reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin 6; LDL-c, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; M, male; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NF-κB, Nuclear factor kappa B; QUICKI, quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor -α ; TPM, Traditional Persian Medicine; VLDL, very low density lipoprotein; WC, waist circumference; WHR, waist to hip ratio

Outcomes measurements

Effects of N. sativa on hepatic steatosis and liver enzymes

The majority of reviewed RCTs had assessed the results of N. sativa supplementation on hepatic steatosis in patients with NAFLD. Two RCTs evaluated the change in fatty liver grade via ultrasound imaging (Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Khonche et al., 2019 ▶). In one study, FibroScan was used to assess the amount of hepatic fibrosis and steatosis. This technique is a non-invasive and easy method to evaluate the stiffness of the liver (Darand et al., 2019a ▶). In three included studies, fatty liver and steatosis grades were reduced significantly after N. sativa supplementation (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Khonche et al., 2019 ▶). Also, serum levels of liver aminotransferases (AST and ALT) were measured in all RCTs. Serum concentrations of AST and ALT significantly reduced after N. sativa supplementation in three RCTs (Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Khonche et al., 2019 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) is another liver enzyme assessed in 3 trials, but no significant changes in any of them were observed (Darand et al., 2019b ▶; Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶).

Effects of N. sativa supplementation on blood glucose, insulin resistance, and inflammatory factors

Two RCTs evaluated the biomarkers of glucose metabolism, including serum glucose, serum insulin, HOMA-IR, and quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Serum insulin and glucose were assessed in both studies (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Serum glucose was significantly decreased in both studies, but serum insulin was reduced significantly in Darand et al. study (Darand et al., 2019a). Also, in their trial, HOMA-IR and QUICKI were assessed; HOMA-IR significantly was decreased while QUICKI significantly was increased (Darand et al., 2019a ▶).

Two RCTs evaluated the inflammatory biomarkers as secondary outcomes, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Darand et al., 2019b ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). TNF-α was significantly reduced in both studies; however, hs-CRP was decreased in one of the mentioned trials (Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Also, IL-6 was assessed in Rashidmayvan et al. study and the results showed a significant reduction in this outcome after N. sativa supplementation (Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶).

Effects of N. sativa supplementation on lipids, anthropometric indices, and blood pressure

Three trials assessed serum lipid levels, including triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL). TG, LDL-C, and HDL-C were evaluated in all three studies (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Khonche et al., 2019 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Only in two of these studies, LDL-C and TG were significantly decreased, and HDL-C was increased considerably (Khonche et al., 2019 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Two studies evaluated TC (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶), but only in one of them, TC significantly decreased (Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Also, VLDL was assessed in Rashidmayvan et al. study and the corresponding results showed a significant reduction in this outcome after N. sativa supplementation (Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Some anthropometric indices such as body mass index (BMI), body weight, waist circumference (WC), and waist to hip ratio (WHR) were assessed in 3 trials (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). The body weight and BMI were changed significantly in Hussain et al. study (Hussain et al., 2017 ▶); however, no changes were seen in other studies. Rashidmayvan et al. assessed blood pressure in their research. However, they did not find any significant differences in systolic blood pressure (SBP) or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) after the intervention (Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶).

Confounding Variables

Based on the articles studied in this review, it was identified that age, sex, BMI, WHR, physical activity, and dietary intakes are potential confounders in the effect of N. sativa on NAFLD. Two studies adjusted for age, sex, BMI (Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Khonche et al., 2019 ▶), and one adjusted for BMI, WHR, physical activity, and dietary intakes (Darand et al., 2019b ▶).

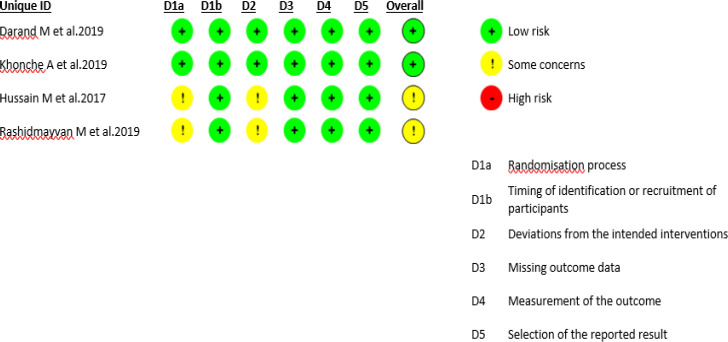

Quality assessment

The risks of bias in each domain are shown in Figure 2. Two trials had an overall score of "low risk" (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Khonche et al., 2019 ▶) and the remaining two had an overall score of "some concern" (Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). The randomization process and the deviation from the intended intervention were two domains that got scored as "some concern" in the trials by Hussain et al. and Rashidmayvan et al. (Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias for each included study

Discussion

For many years, N. sativa has been known as a hepatoprotective herb (Darakhshan et al., 2015 ▶). One of the main active ingredients of N. sativa is thymoquinone (TQ) which has anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fibrotic properties (Abbasnezhad et al., 2015 ▶; Salem, 2005 ▶). The suggested mechanisms of action of N. sativa, relevant to NAFLD, are summarized in Table 2. These rationales of the effects of N. sativa on the liver provided the basis for clinical trial studies. In recent years, several studies have been conducted in this field. Therefore, the primary purpose and innovation of the present study was to critically review the clinical trials on the effects of N. sativa on NAFLD, compare their findings and limitations in a single framework, and provide suggestions for a better design of future studies. In the following paragraphs, we discuss the results of the included studies in terms of the effect of N. sativa on hepatic steatosis, liver enzymes, insulin resistance, lipid profile, inflammatory factors, and BMI.

Table 2.

Mechanisms related to hepatoprotective effects of Nigella sativa

| Mechanism action of N.sativa on liver enzymes |

Increased fatty acid beta-oxidation, mitochondrial function, and production of ATP Decreased oxidative stress in the liver cells, and lipid accumulation in the liver |

| Mechanism action of N.sativa on obesity |

Increased basal metabolism Decreased insulin resistance, oxidative stress, lipid profile, and appetite |

| Mechanism action of N.sativa on lipid profile |

Increased expression of LDL receptor genes Decreased LDL-C oxidation, Intestinal absorption of cholesterol, and HMGCR activity Down-regulated of APO-B100 |

| Mechanism action of N.sativa on serum glucose and insulin resistance |

Increased gene expression of GLUT-4, and AMPK activity Decreased Liver gluconeogenesis, and TNF-alpha |

| Mechanism action of N.sativa on inflammation |

Decreased production of ROS, production of PG-E2, IL-6, AP-1 activity, TNF-alpha, and hs-CRP Inhibiting IRAK1, and NF-kB |

|

Mechanism effect of N.sativa on oxidative stress |

Increased glutathione level, catalase activity, SOD activity, and quinone reductase activity Decreased MDA, ROS, lipid peroxidase activity, and COX-1,2 activity |

| Mechanism action of N.sativa on apoptosis |

Increased sirtuin 1 expression, B-cell lymphoma-2 level Decreased caspase 3 expression |

| Mechanism effect of N.sativa on fibrosis |

Increased AMPK activity Decreased TGF-β, and α-smooth muscle actin expression |

AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; AP-1, Activator protein 1; APO-B100, Apolipoprotein B-100; ATP, Adenosine triphosphate; COX, cyclo-oxygenase; GLUT-4,Glucose transporter type 4; HMGCR, 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Reductase; hs-CRP, high-sensitive C reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin 6; IRAK1, Interleukin 1 Receptor Associated Kinase 1; LDL-c, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; MDA, malondialdehyde; NF-κB, Nuclear factor kappa B ; PG-E2, Prostaglandin E2; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; SOD, Superoxide dismutase; TGF-β,Transforming growth factor beta; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor–α

In three studies that assessed steatosis levels, the grade of fatty liver and steatosis were decreased significantly after N. sativa supplementation (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Khonche et al., 2019 ▶). In Khonche et al. study, 60 individuals with NAFLD consumed 2.5 ml fully standardized N. sativa seed oil every 12 hr, and 60 other patients consumed placebo in 3 months. At the end of the study, N. sativa seed oil significantly improved fatty liver grade as evaluated using ultrasound imaging. It has been suggested that monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) may improve fatty liver disease by increasing fatty acid oxidation and inhibiting triglyceride synthesis in the liver (Silva Figueiredo et al., 2018 ▶). In fact, the essential oil of N. sativa has a higher content of PUFAs in comparison to MUFAs (Salehi et al., 2021 ▶). It seems that the possible roles of PUFAs on NAFLD may be more effective than MUFAs (Sheashea et al., 2021 ▶). Also, Khonche et al. study reported that N. sativa seed oil might protect against hepatic damage in NAFLD (Khonche et al., 2019 ▶). The study by Darand et al. showed a significant reduction in hepatic steatosis grade after the N. sativa supplementation (Darand et al., 2019a ▶). They conducted a 12-week trial in 50 NAFLD patients randomly assigned to receive two g/day of either N. sativa or placebo and lifestyle modification in both groups. Their results demonstrated that daily consumption of 2 g N. sativa supplementation and dietary recommendations are more effective in reducing steatosis in NAFLD patients than dietary recommendations alone. Using transient elastography for evaluating NAFLD in Darand et al. study differentiates their study from others. This method can identify and assess liver steatosis even if the amount of accumulated lipid is ten percent (Dowman et al., 2011 ▶). The amelioration of steatosis in their study may be related to the antioxidant properties of N. sativa and its lipid oxidation suppressive effect (Moschen et al., 2012 ▶). However, because of its potential risk in cardiovascular disease, only one dosage of N. sativa was given, and it was the main limitation of Darand et al. study. Of note, using different methods for monitoring liver steatosis and fibrosis would find conflicting results among the studies. In the present systematic review, three RCTs (Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Khonche et al., 2019 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶) used ultrasound and one RCT (Darand et al., 2019a ▶) used transient elastography to identify and assess the fatty liver grade. It is essential to be noted that these methods cannot detect any histological changes in the liver as precisely as the biopsy method (Saleh and Abu-Rashed, 2007 ▶). Liver biopsy remains the gold-standard method to detect and evaluate fibrosis, steatosis, and inflammation in patients with NAFLD; however, it is restricted by cost, procedure-related morbidity and mortality, intra- and inter-observer variability, sampling error, and ethical issues (Chartampilas, 2018 ▶; Saleh and Abu-Rashed, 2007 ▶).

Serum concentrations of liver enzymes (ALT, AST, and GGT) significantly reduced after N. sativa supplementation in three RCTs (Hussain et al., 2017 ▶; Khonche et al., 2019 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). However, in Darand et al. study, no significant changes were observed in liver enzymes after the intervention (Darand et al., 2019a ▶). Failure to observe significant changes in liver enzyme levels after the intervention in their study may be due to the normal level of these enzymes at the study's baseline. The mitochondrial action enhancement is one of the mechanisms of TQ on lowering the liver enzymes levels (Sayed-Ahmed and Nagi, 2007 ▶).

NAFLD is associated with atherogenic dyslipidemia and HDL dysfunction (Katsiki et al., 2016 ▶). Of note, it has been proposed that N. sativa improves fatty acid beta‐oxidation in the liver (Balbaa et al., 2017 ▶; Hosseinian et al., 2018 ▶; Khaldi et al., 2018 ▶) (Table 2). Out of the three reviewed trials that evaluated lipid profile (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Khonche et al., 2019 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶), two trials reported a significant change in lipid profile after N. sativa supplementation (Khonche et al., 2019 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Tocopherol, TQ, and phytosterol are antioxidant compounds in N. sativa, which suppress intestinal absorption of cholesterol, decrease the creation of hydroxyl–methyl–glutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR), inhibit LDL‐C oxidation, and increase the expression of LDL receptor genes via reduction of intracellular cholesterol ( Al-Naqeeb and Ismail, 2009 ▶; Brufau et al., 2008 ▶; Mariod et al., 2009 ▶). For these reasons, N. sativa may have a beneficial effect on lipid profile. However, at the end of the Darand et al. study, lipid profile, including total cholesterol, LDL‐C, and TG, did not significantly decrease in the group that received N. sativa. The normal serum lipid profile level at the onset of the trial was probably a reason for these unexpected outcomes (Darand et al., 2019a ▶).

One of the most important features of metabolic syndrome is insulin resistance, which is the common risk factor for NAFLD progression (Hamaguchi et al., 2005 ▶; Lomonaco et al., 2012 ▶; Pagano et al., 2002 ▶). Insulin improves glucose absorption for glycogen storage or glucose oxidation in the liver and muscle. The prominent role of insulin is to inhibit gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis in the liver. In addition, insulin increases triglyceride and cholesterol synthesis in the liver (Biddinger et al., 2008 ▶).

In the present study, some included RCTs assessed HOMA-IR and QUICKI (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Because of the good correlation between HOMA-IR and glycemic clamp, HOMA-IR is usually assumed as insulin resistance index in NAFLD patients (Salgado et al., 2010 ▶). HOMA-IR and QUICKI are used to detect insulin resistance in epidemiological and clinical studies (Hrebicek et al., 2002 ▶; Salgado et al., 2010 ▶). In Darand et al. study, HOMA-IR and QUICKI were improved significantly compared to the study's baseline values (Darand et al., 2019a ▶). Serum insulin and glucose were assessed in two included RCTs (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Serum glucose was significantly decreased in both mentioned trials, while serum insulin was significantly reduced only in Darand et al. study (Darand et al., 2019a ▶). The possible reasons for these conflicting results might be the differences in the amount and type of N. sativa used in the supplements and the duration of the intervention periods.

As previously mentioned, hypertension, as a cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor, is associated with NAFLD (Katsiki et al., 2016 ▶). Some studies have shown the association between high blood pressure and NAFLD (Catena et al., 2013 ▶; Fallo et al., 2008 ▶; Lopez-Suarez et al., 2011 ▶). Rashidmayvan et al. performed an 8-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 44 patients diagnosed with NAFLD. Patients were randomly divided into two groups; the intervention group consumed 1000 mg N. sativa oil and the other group consumed paraffin oil as a placebo (Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Blood pressure was measured as a secondary outcome only in this included RCT. However, the corresponding results showed no change in SBP or DBP after N. sativa intake. Of note, based on the reported mean of the blood pressure, most of the participants were normotensive at baseline. The effects of N. sativa on blood pressure may be more pronounced in patients with hypertension. It seems that RCTs with a longer duration of intervention and higher doses of N. sativa on participants with hypertension, are needed to elucidate the effects of this supplement on blood pressure.

Inflammation plays an important role in progressing from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis in NAFLD. In the present study, two included trials assessed the impact of N. sativa supplementation on inflammatory biomarkers (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). TNF-α was significantly reduced in both studies; however, hs-CRP was decreased in one of the mentioned trials (Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). Also, IL-6 was assessed in Rashidmayvan et al. study and the results showed a significant reduction in this outcome after N. sativa supplementation (Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). None of the included trials evaluated the effect of N. sativa on pro-fibrotic biomarkers such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and procollagen III propeptide. Fibrosis is the advanced form of NAFLD that predisposes patients to liver cirrhosis (Sayiner et al., 2018 ▶). Pro-fibrotic factors activate the hepatic stellate cells (HSC) which are responsible for liver fibrosis (Gandhi, 2017 ▶). Interestingly, there is evidence that TQ may have beneficial effects on hepatic fibrosis via reducing mRNA expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), collagen-І and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) (Asgharzadeh et al., 2017 ▶; Bai et al., 2014 ▶). Therefore, designing clinical trial studies to investigate the effect of N. sativa on pro-fibrotic factors in patients with NAFLD is suggested.

Among the included trials, only in Hussain et al. study, body weight and BMI were changed significantly after the N. sativa supplementation (Hussain et al., 2017 ▶). However, the lack of assessment of changes in participants' energy and nutrient intake was one of the most important limitations of their study. In other words, the weight loss observed in that study may be due to a change in energy intake, not necessarily simply due to N. sativa consumption. Of the included studies, only Darand et al. evaluated participants' energy intake during the intervention (Darand et al., 2019a ▶). Their results showed that weight and BMI were decreased significantly only in the N. sativa group, whereas energy intake was reduced significantly in both groups (Darand et al., 2019a ▶). Because the changes in energy intake and physical activity were not different between the two groups at the end of the trial, they concluded that N. sativa might decrease body weight through rising basal metabolism (Darand et al., 2019a ▶). The suggested mechanisms of the effects of N. sativa on body weight are shown in Table 2. The RCTs included in our systematic review had different study durations and amounts of N. sativa supplementation. As a result, some contradictory results exist between them. More RCTs are needed to confirm the proper doses and intervention periods of N. sativa supplementation on NAFLD. In addition, different types of N. sativa were used in the reviewed studies. Darand et al. and Hussain et al. used N. sativa seed powder (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Hussain et al., 2017 ▶), while Khonche et al. and Rashidmayvan et al. used N. sativa seed oil (Khonche et al., 2019 ▶; Rashidmayvan et al., 2019 ▶). It should be noted that TQ, as an active ingredient of N. sativa, has a limited bioavailability. Since it is a hydrophobic agent, it is more available in the essential oil of N. sativa compared to the whole seeds (Goyal et al., 2017 ▶). On the other hand, in the blood, TQ is carried by the human serum albumin (HAS) and α1-acid glycoprotein (AGP) (Lupidi et al., 2012 ▶). Under normal physiological conditions, TQ preferentially binds to HAS. However, because blood levels of AGP are increased considerably in inflammatory diseases, such as NAFLD, the interaction of TQ with AGP may affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of TQ (Lupidi et al., 2012 ▶). Today, efforts are being made to increase the bioavailability of TQ using pharmaceutical nanotechnology (Goyal et al., 2017 ▶). For more information about the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of TQ and N. sativa, please refer to Goyal et al. (Goyal et al., 2017 ▶). Despite all mentioned above, it should be noted that the consumption of N. sativa whole seeds can provide fiber and some vitamins and minerals that may have beneficial effects on the metabolic profiles of patients with NAFLD.

When RCTs were reviewed, two studies were identified from the same authors that presented data from the same subjects (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Darand et al., 2019b ▶). They were considered a single study in our systematic review to reduce possible errors, although we reported all outcomes (Darand et al., 2019a ▶; Darand et al., 2019b ▶). The limitation of the present study was the ineffectiveness of conducting a meta-analysis of the included data. Because of the few studies conducted to evaluate the effects of N. sativa on NAFLD, their heterogeneity would be high and meta-analysis was not possible. In other words, if significant heterogeneity is detected among the studies, including their data in a meta-analysis study will yield inconclusive findings (Higgins et al., 2003 ▶). As a result, we did not conduct a meta-analysis on studies' data. Recently, a systematic review and meta-analysis has been conducted on the effects of N. sativa in patients with NAFLD and has assessed the relationship between N. sativa, lipid profile, glycemic parameters, liver enzymes, inflammatory factors, and grade of fatty liver (Tang et al., 2021 ▶). The study indicated that AST, ALT, FBS, HDL, and hs-CRP were improved after N. sativa supplementation in patients with NAFLD, but there were no significant changes in TC, LDL, TG, insulin, and TNF-α. However, as mentioned and predicted, the heterogeneity index in this meta-analysis was high, limiting the conclusion about the definitive effects of N. sativa on NAFLD outcomes.

The strength of our study was the extensive literature review and adherence to the PRISMA statement. In addition, one of the important aims of the present study was providing suggestions that help designing future studies to better clarify the beneficial roles of N. sativa in NAFLD prevention and treatment. Based on the results of the clinical trials reviewed in the present study, we would suggest the following points:

More accurate and precise measurement methods to monitor liver histopathology (e.g. liver biopsy, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, or transient elastography) should be used.

It would be better to divide the study groups into different subtypes of steatosis, steatohepatitis, and liver fibrosis and then compare the effects of N. sativa supplementation between them.

Studies with the specific objective to evaluate the combination therapy of N. sativa with other herbal or nutritional supplements to investigate their synergistic effects on NAFLD are suggested.

Assessing the effects of N. sativa supplementation on serum biomarkers of inflammation, oxidative stress, and pro-fibrotic factors would be more inclusive.

Investigation about the gene expression of each biomarker of NAFLD after N. sativa supplementation would bring advanced results.

The use of nano-encapsulated forms of TQ in future interventions on NAFLD will reveal valuable evidence.

Although the efficacy of N. sativa on liver enzymes and the grade of hepatic steatosis has been found in some of the included studies, more well-designed clinical trials are needed to determine the definitive effects of N. sativa on NAFLD.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have declared that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Abbasnezhad A, Hayatdavoudi P, Niazmand S, Mahmoudabady M. The effects of hydroalcoholic extract of Nigella sativa seed on oxidative stress in hippocampus of STZ-induced diabetic rats. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2015;5:333–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Naqeeb G, Ismail M. Regulation of apolipoprotein A-1 and apolipoprotein B100 genes by thymoquinone rich fraction and thymoquinone in HEPG2 cells. J Food Lipids. 2009;16:245–258. [Google Scholar]

- Amizadeh S, Rashtchizadeh N, Khabbazi A, Ghorbanihaghjo A, Ebrahimi AA, Vatankhah AM, Malek Mahdavi A, Taghizadeh M. Effect of Nigella sativa oil extracts on inflammatory and oxidative stress markers in Behcet's disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2020;10:181–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argo CK, Northup PG, Al-Osaimi AM, Caldwell SH. Systematic review of risk factors for fibrosis progression in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2009;51:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgharzadeh F, Bargi R, Beheshti F, Hosseini M, Farzadnia M, Khazaei M. Thymoquinone restores liver fibrosis and improves oxidative stress status in a lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation model in rats. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2017;7:502–510. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai T, Yang Y, Wu YL, Jiang S, Lee JJ, Lian LH, Nan JX. Thymoquinone alleviates thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis and inflammation by activating LKB1-AMPK signaling pathway in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;19:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbaa M, Abdulmalek SA, Khalil S. Oxidative stress and expression of insulin signaling proteins in the brain of diabetic rats: Role of Nigella sativa oil and antidiabetic drugs. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben El Mostafa S, Abdellatif M. Herbal Medicine in Chronic Diseases Treatment: Determinants, Benefits and Risks. 2020. pp. 85– 95. [Google Scholar]

- Benhaddou-Andaloussi A, Martineau L, Vuong T, Meddah B, Madiraju P, Settaf A, Haddad PS. The in vivo antidiabetic activity of Nigella sativa is mediated through activation of the AMPK pathway and increased muscle Glut4 Content. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:538671. doi: 10.1155/2011/538671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddinger SB, Hernandez-Ono A, Rask-Madsen C, Haas JT, Aleman JO, Suzuki R, Scapa EF, Agarwal C, Carey MC, Stephanopoulos G, Cohen DE, King GL, Ginsberg HN, Kahn CR. Hepatic insulin resistance is sufficient to produce dyslipidemia and susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2008;7:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brufau G, Canela MA, Rafecas M. Phytosterols: physiologic and metabolic aspects related to cholesterol-lowering properties. Nutr Res. 2008;28:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catena C, Bernardi S, Sabato N, Grillo A, Ermani M, Sechi LA, Fabris B, Carretta R, Fallo F. Ambulatory arterial stiffness indices and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in essential hypertension. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartampilas E. Imaging of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its clinical utility. Hormones (Athens) 2018;17:69–81. doi: 10.1007/s42000-018-0012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Wang L, Yang G, Xu H, Liu J. Chinese herbal medicine combined with conventional therapy for blood pressure variability in hypertension patients: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:582751. doi: 10.1155/2015/582751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero AF, De Sando V, Izzo R, Vasta A, Trimarco A, Borghi C. Effect of a combined nutraceutical containing Orthosiphon stamineus effect on blood pressure and metabolic syndrome components in hypertensive dyslipidaemic patients: a randomized clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2012;18:190–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero AFG, Colletti A, Bellentani S. Nutraceutical approach to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): The available clinical evidence. Nutrients. 2018;10:1153. doi: 10.3390/nu10091153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darakhshan S, Bidmeshki Pour A, Hosseinzadeh Colagar A, Sisakhtnezhad S. Thymoquinone and its therapeutic potentials. Pharmacol Res. 2015;95-96:138–158. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darand M, Darabi Z, Yari Z, Hedayati M, Shahrbaf MA, Khoncheh A, Hosseini-Ahangar B, Alavian SM, Hekmatdoost A. The effects of black seed supplementation on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytother Res. 2019a;33:2369–2377. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darand M, Darabi Z, Yari Z, Saadati S, Hedayati M, Khoncheh A, Hosseini-Ahangar B, Alavian SM, Hekmatdoost A. Nigella sativa and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Complement Ther Med. 2019b;44:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowman JK, Tomlinson JW, Newsome PN. Systematic review: the diagnosis and staging of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:525–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallo F, Dalla Pozza A, Sonino N, Federspil G, Ermani M, Baroselli S, Catena C, Soardo G, Carretta R, Belgrado D, Fabris B, Sechi LA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, adiponectin and insulin resistance in dipper and nondipper essential hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2008;26:2191–2197. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32830dfe4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi CR. Hepatic stellate cell activation and pro-fibrogenic signals. J Hepatol. 2017;67:1104–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal SN, Prajapati CP, Gore PR, Patil CR, Mahajan UB, Sharma C, Talla SP, Ojha S K. Therapeutic potential and pharmaceutical development of thymoquinone: A multitargeted molecule of natural origin. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:656. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadi V, Kheirouri S, Alizadeh M, Khabbazi A, Hosseini H. Effects of Nigella sativa oil extract on inflammatory cytokine response and oxidative stress status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2016;6:34–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Takeda N, Nakagawa T, Taniguchi H, Fujii K, Omatsu T, Nakajima T, Sarui H, Shimazaki M, Kato T, Okuda J, Ida K. The metabolic syndrome as a predictor of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:722–728. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasani-Ranjbar S, Nayebi N, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of herbal medicines used in the treatment of obesity. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2009;15:3073–3085. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasani-Ranjbar S, Nayebi N, Moradi L, Mehri A, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. The efficacy and safety of herbal medicines used in the treatment of hyperlipidemia; a systematic review. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:2935–2947. doi: 10.2174/138161210793176464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashempur MH, Heydari M, Mosavat S H, Heydari ST, Shams M. Complementary and alternative medicine use in Iranian patients with diabetes mellitus. J Integr Med. 2015;13:319–325. doi: 10.1016/S2095-4964(15)60196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini B, Saedisomeolia A, Wood LG, Yaseri M, Tavasoli S. Effects of pomegranate extract supplementation on inflammation in overweight and obese individuals: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;22:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini S, Razmgah G, Nematy M, Esmaily H, Yousefi M, Kamalinejad M, Mosavat SH. Efficacy of black seed (Nigella sativa) and lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2018;20:e59183. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinian S, Hadjzadeh MA, Roshan NM, Khazaei M, Shahraki S, Mohebbati R, Rad AK. Renoprotective effect of Nigella sativa against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and oxidative stress in rat. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2018;29:19–29. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.225208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrebicek J, Janout V, Malincikova J, Horakova D, Cizek L. Detection of insulin resistance by simple quantitative insulin sensitivity check index QUICKI for epidemiological assessment and prevention. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:144–147. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.1.8292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain M, Tunio AG, Akhtar L, Shaikh GS. Effects of nigella sativa on various parameters in Patients of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2017;29:403–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsiki N, Mikhailidis DP, Mantzoros CS. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and dyslipidemia: An update. Metabolism. 2016;65:1109–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating SE, Hackett DA, George J, Johnson N A. Exercise and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2012;57:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaldi T, Chekchaki N, Boumendjel M, Taibi F, Abdellaoui M, Messarah M, Boumendjel A. Ameliorating effects of Nigella sativa oil on aggravation of inflammation, oxidative stress and cytotoxicity induced by smokeless tobacco extract in an allergic asthma model in Wistar rats. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2018;46:472–481. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khonche A, Huseini H F, Gholamian M, Mohtashami R, Nabati F, Kianbakht S. Standardized Nigella sativa seed oil ameliorates hepatic steatosis, aminotransferase and lipid levels in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;234:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmeyer CC, McCullough AJ. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-an evolving view. Clin Liver Dis. 2018;22:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomonaco R, Ortiz-Lopez C, Orsak B, Webb A, Hardies J, Darland C, Finch J, Gastaldelli A, Harrison S, Tio F, Cusi K. Effect of adipose tissue insulin resistance on metabolic parameters and liver histology in obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2012;55:1389–1397. doi: 10.1002/hep.25539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Suarez A, Guerrero JM, Elvira-Gonzalez J, Beltran-Robles M, Canas-Hormigo F, Bascunana-Quirell A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with blood pressure in hypertensive and nonhypertensive individuals from the general population with normal levels of alanine aminotransferase. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:1011–1017. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834b8d52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupidi G, Camaioni E, Khalifé H, Avenali L, Damiani E, Tanfani F, Scirè A. Characterization of thymoquinone binding to human α₁-acid glycoprotein. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101:2564–2573. doi: 10.1002/jps.23138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariod AA, Ibrahim RM, Ismail M, Ismail N. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of phenolic rich fractions obtained from black cumin (Nigella sativa) seedcake. Food Chemistry. 2009;116:306–312. [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtari Z, Gibson DL, Hekmatdoost A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, the gut microbiome, and diet. Adv Nutr. 2017;8:240–252. doi: 10.3945/an.116.013151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschen AR, Wieser V, Tilg H. Adiponectin: Key player in the adipose tissue-liver crosstalk. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:5467–5473. doi: 10.2174/092986712803833254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mummadi RR, Kasturi KS, Chennareddygari S, Sood GK. Effect of bariatric surgery on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1396–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muneera KE, Majeed A, Naveed AK. Comparative evaluation of Nigella sativa (Kalonji) and simvastatin for the treatment of hyperlipidemia and in the induction of hepatotoxicity. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2015;28:493–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano G, Pacini G, Musso G, Gambino R, Mecca F, Depetris N, Cassader M, David E, Cavallo-Perin P, Rizzetto M. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome: further evidence for an etiologic association. Hepatology. 2002;35:367–372. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, Jackvony E, Kearns M, Wands JR, Fava J L, Wing RR. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:121–129. doi: 10.1002/hep.23276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashidmayvan M, Mohammadshahi M, Seyedian SS, Haghighizadeh MH. The effect of Nigella sativa oil on serum levels of inflammatory markers, liver enzymes, lipid profile, insulin and fasting blood sugar in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2019;18:453–459. doi: 10.1007/s40200-019-00439-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahebkar A, Soranna D, Liu X, Thomopoulos C, Simental-Mendia LE, Derosa G, Maffioli P, Parati G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials investigating the effects of supplementation with Nigella sativa (black seed) on blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2016;34:2127–2135. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh HA, Abu-Rashed AH. Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for evaluation of chronic hepatitis and fibrosis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007;16:425–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi B, Quispe C, Imran M, Ul-Haq I, Živković J, Abu-Reidah IM, Sen S, Taheri Y, Acharya K, Azadi H, Del Mar Contreras M, Segura-Carretero A, Mnayer D, Sethi G, Martorell M, Abdull Razis AF, Sunusi U, Kamal RM, Rasul Suleria HA, Sharifi-Rad J. Nigella plants - traditional uses, bioactive phytoconstituents, preclinical and clinical studies. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.625386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem ML. Immunomodulatory and therapeutic properties of the Nigella sativa L seed. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;5:1749–1770. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado AL, Carvalho L, Oliveira AC, Santos VN, Vieira JG, Parise ER. Insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR) in the differentiation of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and healthy individuals. Arq Gastroenterol. 2010;47:165–169. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032010000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani NB, Jokar A, Soveid M, Heydari M, Mosavat SH. Efficacy of the hydroalcoholic extract of Tribulus terrestris on the serum glucose and lipid profile of women with diabetes mellitus: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016;21:Np91–7. doi: 10.1177/2156587216650775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed-Ahmed MM, Nagi MN. Thymoquinone supplementation prevents the development of gentamicin-induced acute renal toxicity in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:399–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayiner M, Lam B, Golabi P, Younossi ZM. Advances and challenges in the management of advanced fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756284818811508. doi: 10.1177/1756284818811508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi N, Amani R. Vitamin D supplementation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A critical and systematic review of clinical trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59:693–703. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2017.1389693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi N, Amani R, Hajiani E, Cheraghian B. Does vitamin D improve liver enzymes, oxidative stress, and inflammatory biomarkers in adults with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? A randomized clinical trial. Endocrine. 2014;47:70–80. doi: 10.1007/s12020-014-0336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheashea M, Xiao J, Farag MA. MUFA in metabolic syndrome and associated risk factors: is MUFA the opposite side of the PUFA coin? Food Funct. 2021;12:12221–12234. doi: 10.1039/d1fo00979f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva Figueiredo P, Inada AC, Ribeiro Fernandes M, Granja Arakaki D, Freitas KC, Avellaneda Guimaraes RC, Aragao do Nascimento V, Aiko Hiane P. An overview of novel dietary supplements and food ingredients in patients with metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Molecules. 2018;23:877. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui Y, Zhao H, Wong V, Brown N, Li X, Kwan A, Hui H, Ziea E, Chan J. A systematic review on use of Chinese medicine and acupuncture for treatment of obesity. Obes Rev. 2012;13:409–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G, Zhang L, Tao J, Wei Z. Effect of Nigella sativa in the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phytother Res. 2021;35:4183–4193. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh GY, Eisenberg DM, Kaptchuk TJ, Phillips RS. Systematic review of herbs and dietary supplements for glycemic control in diabetes. Diabetes care. 2003;26:1277–1294. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younossi ZM, Marchesini G, Pinto-Cortez H, Petta S. Epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Implications for liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2019;103:22–27. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]