Abstract

The continuous, real-time measurement of specific molecules in situ in the body would greatly improve our ability to understand, diagnose, and treat disease. The vast majority of continuous molecular sensing technologies, however, either (1) rely on the chemical or enzymatic reactivity of their targets, sharply limiting their scope, or (2) have never been shown (and likely will never be shown) to operate in the complex environments found in vivo. Against this background, here we review electrochemical aptamer-based (EAB) sensors, an electrochemical approach to real-time molecular monitoring that has now seen 15 years of academic development. The strengths of the EAB platform are significant: to date it is the only molecular measurement technology that (1) functions independently of the chemical reactivity of its targets, and is thus general, and (2) supports in vivo measurements. Specifically, using EAB sensors we, and others, have already reported the real-time, seconds-resolved measurements of multiple, unrelated drugs and metabolites in situ in the veins and solid tissues of live animals. Against these strengths, we detail the platform’s remaining weaknesses, which include still limited measurement duration (hours, rather than the more desirable days) and the difficulty in obtaining sufficiently high-performance aptamers against new targets, before then detailing promising approaches overcoming these hurdles. Finally, we close by exploring the opportunities we believe this potentially revolutionary technology (as well as a few, possibly competing technologies) will create for both researchers and clinicians.

Keywords: In-vivo sensing, electrochemical aptamer sensors, EAB sensors, E-AB sensors, electrochemical biosensing, biosensors

Graphical Abstract

Motivation

Diseases are dynamic processes. Given this, the ability to track the concentrations of specific molecules in the body in real time would significantly improve our ability to study, monitor, and treat them. The ability to monitor blood glucose in real time, for example, has greatly advanced the treatment of diabetes. Likewise, pulse oximeters supporting real-time measurements of blood oxygenation have grown into ubiquitous tools both for surgery and routine health monitoring. Unfortunately, however, at present the continuous glucometer and the pulse oximeter are the sole commercially available sensors supporting high-frequency, in-vivo molecular measurements. Given the promise of time resolved in-vivo molecular sensing, why do we not have sensors for the many other molecules indicative of health, disease, and treatment status?

The answer to this query has been that, historically, the few sensors that support in vivo molecular monitoring are not generalizable, and the few generalizable sensing platforms fail when deployed in vivo. For example, although the continuous glucose monitor is a wildly successful example of in vivo molecular sensing, it relies critically on the enzymatic conversion of glucose into an easily detectable electroactive product1. Thus, it is difficult to generalize this approach to new targets. As it relies on a spectroscopic change produced by the covalent binding of oxygen to hemoglobin2, the pulse oximeter is likewise difficult to adapt to new targets. Many other sensing approaches, in contrast, do not depend on the target’s specific chemical reactivity, rendering them generalizable. Other platforms may detect binding of target to a receptor coated surface via changes in mass3–5 or electrical response6–8. Unfortunately, while these approaches are general, they fail when challenged in bodily fluids due to the non-specific adsorption of interferents. This occurs because fouling generates a signal that is often indistinguishable from that produced by target binding.

A potential solution to the above-described challenges has been achieved with the invention electrochemical aptamer-based (EAB) sensors. First reported some 15 years ago, EAB sensors are the only technology described to date that both (1) functions independently of the reactivity of its targets and (2) is selective enough to work in situ in the living body. Comprised of an aptamer (a nucleic acid selected in vitro to bind to a specific molecular target) modified with a redox reporter and attached to an electrode via a self-assembled monolayer, EAB sensors rely on binding-induced changes in the conformation of this aptamer to generate a signal. Specifically, this binding-induced conformational change alters the rate of electron transfer from the reporter. This, in turn, produces an easily measured change in electrochemical signal when the sensor is interrogated using any of a range of electrochemical techniques, including square wave voltammetry9, chrono-amperometry10, cyclic voltammetry11, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy12.

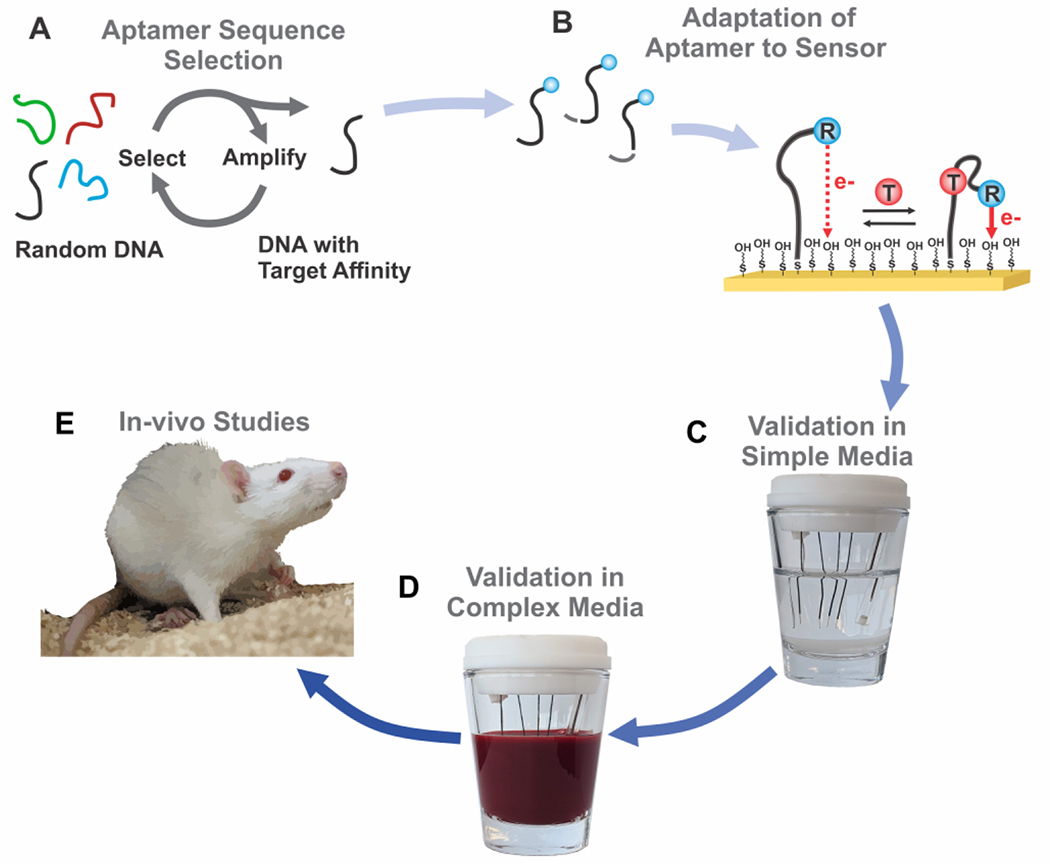

EAB sensors are modular, such that the development of sensors against new targets requires only the discovery of the appropriate aptamer and its adaptation into the platform. Aptamer selection is performed in-vitro via a process termed Systemic Evolution of Ligand Exponential Enrichment, or “SELEX” (Figure 1A)13, 14. To adapt the resulting aptamer sequences into EAB sensors, they are first modified such that they undergo a binding-induced conformational change, typically via the introduction of destabilizing mutations that lead to binding-induced folding15–17. To convert this binding-induced conformational change into a measurable shift in electron transfer rate, the sequence is modified with an alkane thiol and a redox reporter capable of reversibly transferring electrons. Of the redox reporters explored, methylene blue has proven the most popular due to its stability under repeated electrochemical interrogation18. And while the electron transfer kinetics of this reporter depend upon pH19, limiting its application to media with stable pH, new redox reporters are being explored that do not display such dependence20. Finally, the sensor is fabricated by attaching the redox-reporter-modified aptamer to a gold electrode via the formation of a thiol-on-gold bond followed by “backfilling” with an alkane thiol to form a stable, self-assembled monolayer (Figure 1B).

Figure 1:

(A) To develop an in-vivo EAB sensor, first an aptamer is selected for a given target using a procedure called Selective Evolution of Ligand Exponential Enrichment (“SELEX”). (B) Modifications to the selected aptamer, such as surface linkers, redox reporter tags, and truncations of aptamer stem length allow adaptation of a given sequence into an EAB sensor. (C) Titrations in simple media, such as phosphate buffered saline, assess aptamer response to target. (D) Pending success in simple media, aptamer response is measured in a media that more closely reflects the in-vivo environment (commonly, bovine blood for venous measurements, or cerebral spinal fluid for in-brain measurements). (E) If the sensor response aligns with the expected physiological target range, it may be applied for measurements in the living body.

Any new sensors we create are validated in vitro prior to in vivo applications. Titrations in a simple media, such as phosphate buffered saline, provide an indication of whether the sensor produces a sufficiently large change to support in vivo sensing. If response is insufficient to achieve good signal-to-noise, the sensor may require modifications, including changes to the aptamer sequence (e.g., truncations) or the position of the redox reporter17. After achieving sufficient performance in simple media, additional titrations are used to assess performance in the biological fluid relevant to the in vivo application, such as whole blood (Figure 1D). If the sensors demonstrate sufficient signal in body temperature biological fluid, they warrant application in live animal models (to date in rats, Figure 1E).

Previous reviews of EAB sensors have explored the applicability of the platform for in vivo measurements21, and detailed their fabrication, interrogation, and optimization22. In this perspective, in contrast, we explore the strengths and weaknesses of the EAB sensor platform, placing particular focus on their application in performing real-time measurements in the living body. We then discuss what we view as the opportunities and threats to be faced in their translation from an academic technique to commercialized devices suitable for in vivo molecular monitoring.

Strengths

We believe EAB sensors exhibit a number of strengths, positioning them as the first generalizable molecular sensing platform that can be deployed in situ in the living body.

Generalizability

Because aptamers themselves function independently of the electrochemical or enzymatic reactivity of their targets, EAB sensors are generalizable to the measurement of a wide range of molecules. Consistent with this, EAB sensors have been described to date against a wide range of therapeutic drugs and drugs of abuse17, 23, 24, proteins1, 25–28,metabolites29, 30, and toxins31–34, with many more aptamer sequences having been reported but not yet adapted to the platform.

High-frequency, real-time molecular measurements

EAB sensors monitor the concentration of their molecular target in real time1, 36 and with seconds or even sub-second time resolution. This impressive time resolution arises from a number of attributes. First, the EAB sensor signal transduction mechanism avoids the need for reagent additions, washing steps, or other sensor regeneration, all of which would introduce significant time lags37–39. Second, for low molecular weight targets, target binding and the resulting aptamer conformational change are rapidly reversible, often rendering the electrochemical interrogation of the device the time-resolution-limiting step. Using square wave voltammetry, for example, typically yields time resolution of a few seconds to a few tens of seconds23, 29, 40, 41. In contrast, interrogation using chronoamperometry10, intermittent pulse amperometry42, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy12 can achieve sub-second time resolution. Such time resolution is faster than most physiological processes, making EAB sensors well-suited to monitoring patient health and treatment status.

Performance in Undiluted Biological Media, and the Living Body

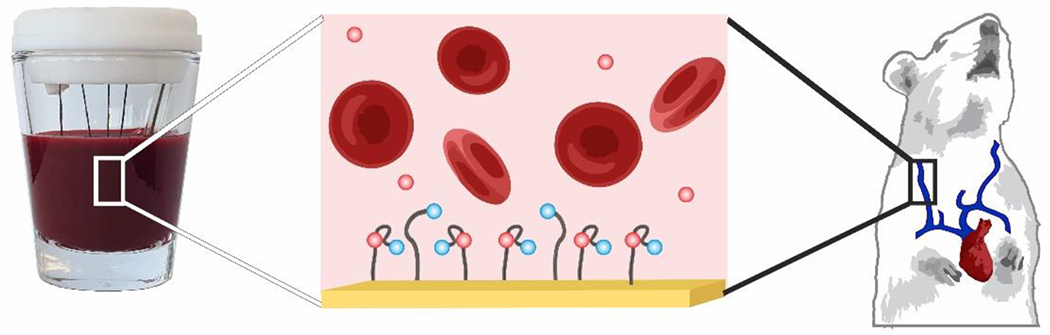

EAB sensors resist fouling sufficiently to support measurements in complex sample matrixes, including undiluted serum1, 24, 43 and whole blood30, 44 (Figure 3). This is not to say that EAB sensors are entirely unaffected by adsorption to the interface. Indeed, when EAB sensors are placed in the complex environments found within the body, fouling and other sensor-degradation phenomena contribute to an often significant decline in signal45. Fortunately, however, this drift can be corrected using a variety of approaches10, 46, 47. The “kinetic differential measurement” (KDM) technique, for example, leverages square wave frequency pairs that, when interrogated sequentially, drift in concert46, 48. Subtracting the normalized peak signals and dividing by their average thus corrects for sensor signal loss over time. Using such techniques has enabled the measurement of a number of targets with clinically-relevant accuracy and precision17, 23, 25, 29, 35, 48, 49.

Figure 3:

EAB sensors maintain signaling even in undiluted whole blood, or the living body. In vivo, this has enabled measurements of pharmaceutical delivery and clearance.

Building on the above attributes, the EAB platform is the only technology demonstrated to achieved hours-long, real-time molecular measurements in the body without relying on the target’s intrinsic reactivity55, spectroscopic properties56, or enzymatic activity57. Specifically, the platform has been used to perform real-time measurements of multiple drugs (including antibiotics17, 48, chemotherapeutics23, 48, 54, and drugs of abuse52) and metabolites (including ATP and phenylalinine29, 30, 53) in situ in the bodies of live rats (Table 2). The resulting measurements achieve unprecedented, seconds-resolved measurement of drug pharmacokinetics and metabolic return to homeostasis. EAB sensors’ real-time measurements have even enabled feedback-controlled drug delivery, achieving exceptional precision and accuracy in the delivery of otherwise difficult-to-safely-administer antibiotics17, 49.

Table 2:

In vivo EAB sensors reported to date.

| Target | Target class | In-vivo application | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin17 | Antibiotic | Measurement of plasma pharmacokinetics, feedback-controlled delivery | 5 h |

| Tobramycin10, 48–51 | Antibiotic | Measurement of plasma and interstitial fluid pharmacokinetics, feedback-controlled delivery | 4 - 12 h |

| Cocaine52 | Drug of Abuse | Measurement of pharmacokinetics in the brain | 4.5 h |

| Kanamycin48, 53 | Antibiotic | Measurement of plasma pharmacokinetics | 3 h |

| Phenylalinine29 | Amino acid | Measurement of plasma kinetics | 1 h |

| Doxorubicin54 | Chemotherapeutic | Measurement of plasma pharmacokinetics | 3 h |

| Adenine Triphosphate53 | Metabolite | Measurement of plasma pharmacokinetics | 3 h |

| Irinotecan23 | Chemotherapeutic | Measurement of plasma pharmacokinetics | 2 h |

| Gentamicin48 | Antibiotic | Measurement of plasma pharmacokinetics | 4 h |

| Doxorubicin48 | Chemotherapeutic | Measurement of plasma pharmacokinetics | 5 h |

Miniaturizable

EAB sensors can be made small enough to implant easily into the body. For example, the in-vein EAB sensors reported to date typically utilize a thin (<300 μm) bundle of wires consisting of a sensor, reference electrode, and counter electrode inserted into a catheter housing17. In the future, performing measurements in other bodily locations, or targeting specific regions of the brain will require even smaller sensors. Sensor size represents a tradeoff between magnitude of electrochemical signal (which influences noise level in measurements) and macro-scale device dimensions. However, EAB sensors may be miniaturized further by increasing the microscopic surface area of the gold working electrode. Increasing the surface area with nanostructured surface morphologies may easily enable further sensor miniaturization. In recent work, for example, we applied nanoporous gold to reduce the dimensions of in-vein sensor size58.

Weaknesses

Our enthusiasm for EAB sensors aside, the technology is, of course, not without limitations.

Adaptation of New Aptamer Sequences to the Platform

The selection and subsequent adaptation of aptamers into the EAB platform can present bottlenecks to producing sensors against new targets. SELEX identifies aptamers that bind to a target – these sequences are typically then characterized free in solution using either optical or calorimetric methods59, 60. When adapting “as-selected” aptamers into EAB sensors, however, their signal gain (the relative change in electrochemical response between the absence of target and saturating target) is often small. Fortunately, this can usually be rectified using a number of rational or semi-rational approaches17, 40 to reengineer the aptamer to undergo a large-scale, binding-induced conformational change. Most often we achieve this via truncation, which destabilizes the aptamer such that it equilibrates between an unfolded conformation and the bound, folded complex17, 40. Alternative approaches include the introduction of long, flexible loops, such that target binding must close the loop61, or complementary strands, such that the aptamer equilibrates between a double-helix and the target-binding conformation62. Recently, spectroscopic approaches have been described to guide the modification of aptamer sensors to generate the needed binding-induced conformational change, further improving the future success of adapting new aptamers into the platform63. The existence of multiple techniques for modifying aptamers to support EAB signaling, however, does not guarantee an aptamer will produce a sensor with sufficient signal response over the desired target concentration range.

Aptamer performance

EAB sensors are often sufficiently selective to monitor their targets in vivo. That is, nothing naturally present in blood or other bodily fluids produces a significant signal response. Nevertheless, EAB sensors cannot be any more specific than the aptamer they employ and, thus, specificity is an inherent concern. Specifically, because aptamers tend to bind a subset of the chemical groups on a target64, and such groups can occur in multiple targets, cross-reactivity is seen in some aptamers65 and in their resulting EAB sensors. For example, cross-reactivity has been observed in the aminoglycoside sensor, which binds to structurally-similar antibiotics, including tobramycin, gentamycin, and kanamycin48. Likewise, an aptamer selected against the drug of abuse, cocaine, also responds to procaine, quinine, and hydroxychloroquine66. Such cross-reactivity poses a challenge to in vivo monitoring if the interfering compound might also exist in the body at concentrations that produce a signal response. Application of EAB sensors to in vivo monitoring, then, requires an understanding of reactivity of the aptamer with any structurally similar compounds that may be present. Fortunately, however, negative aptamer selections provide a potential solution to this challenge. That is, because aptamers are generated via in vitro evolution (unlike, for example, antibodies), negative selective pressure can help remove aptamers with unwanted cross reactivity67.

In vivo measurement Duration

The measurement durations that can be achieved using EAB sensors in vivo remains uncertain. Almost all of the in-vivo EAB measurements reported to date have been collected for less than 6 h. This is primarily due to animal welfare guidelines that dictate that experiments under anesthesia do not exceed this duration. When challenged in vitro in undiluted, body temperature whole blood, however, EAB sensors can achieve durations in excess of 24 h, suggesting that longer duration in vivo measurements are within reach45. That said, it is clear that, eventually, signal loss will pose a challenge to increased measurement duration. A recent review has detailed efforts to address such signal loss in support of longer duration measurements68.

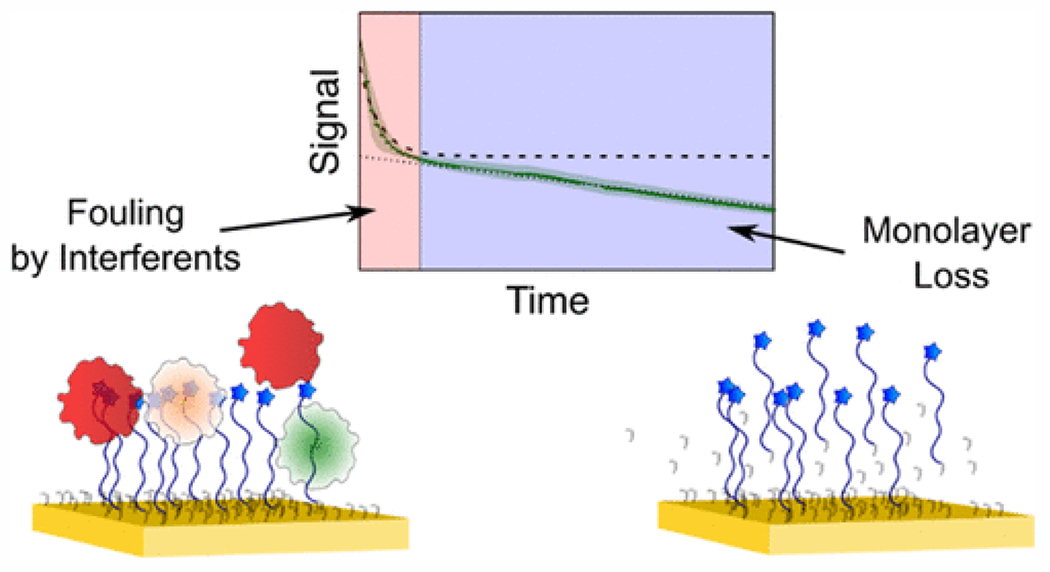

Mechanistic studies of EAB sensor drift suggest approaches by which long duration in vivo measurements can be achieved. When EAB sensors are challenged in body temperature whole blood, their drift manifests as two distinct phases: an exponential signal decrease followed by a linear, sloping decrease45 (Figure 4). Recent work suggests that the more rapid exponential phase arises due to fouling, which decreases the electron transfer rate from the redox reporter to the electrode surface45. Consistent with this, the exponential phase does not occur when sensors are interrogated in simple buffered solutions. Thus, improved monolayer selection may provide an important route to improving in vivo measurement duration. Thicker monolayers (longer alkane chains), for example, are more stable69. Unfortunately, however, electron transfer slows as the monolayer becomes thicker, limited the extent to which we can employ the thickest, most stable monolayers70, 71. The chemistry of monolayer end groups or can also be modulated to improve measurement duration by, for example, reducing monolayer desorption72 and fouling47, 73. Finally, the use of surface treatments and coatings48, 74, or increasing the monolayer packing densities44, could reduce fouling-derived drift by excluding access of proteins of a given size, or by “pre-fouling” the surface such that any further drift is reduced or eliminated.

Figure 4:

When placed in undiluted whole blood at 37°C, EAB sensors fabricated using mercaptohexanol monolayers exhibit an exponential and linear phase of signal loss. The former seems to arise due to fouling, and the latter due to redox-driven loss of the DNA-modified monolayer. (Reproduced from Leung, K. K.; Downs, A. M.; Ortega, G.; Kurnik, M.; Plaxco, K. W., Elucidating the mechanisms underlying the signal drift of electrochemical aptamer-based sensors in whole blood. ACS Sensors 202145. Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.)

In contrast to the biofouling-linked exponential phase of signal loss, the linear drift phase is dominated by the electrochemical effects of sensor interrogation45. When using square wave voltammetry, for example, the rate of the linear drift phase depends strongly on the width of the potential window employed45. When scanning further toward negative potentials, for example, the linear phase accelerates45, presumably due to reductive desorption of the monolayer75. Likewise, applying wider potential windows in the positive direction, which likely increases oxidative desorption of the monolayer, also contributes to the linear loss phase45. Given this, narrowing the potential window used to interrogate EAB sensors reduces this linear drift phase45. In this light, we believe that the use of electrochemical techniques that scan rather narrow potential windows, such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, may prove an important route towards reduced signal drift and greater in vivo measurement duration.

Opportunities

Not surprisingly, we believe the future is promising for in vivo application of EAB sensors, which appear well-suited for application to problems in both biomedical research and clinical care.

Research Applications

As research tools, EAB sensors could significantly advance our understanding of metabolism, endocrinology, pharmacokinetics, and neurochemistry. Specifically, EAB sensors will enable better resolved, more quantitative measurements of such phenomena as drug delivery and clearance and the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis. With their ability to support feedback control, EAB sensors will similarly provide unprecedented opportunities to define the relationship between, for example, plasma drug levels and the resulting clinical or behavioral response. The ability of EAB sensors to perform simultaneous measurements in multiple locations throughout the body will enable a greater understanding of drug and metabolite transport through and between bodily compartments. Finally, in addition to in-body measurements, we believe EAB sensors could also prove useful in the real-time monitoring of cell culture applications ranging from small scale (e.g., “organ on a chip”) to industrial scale (e.g., monitoring industrial bioreactors). In this application space, they have already demonstrated applications in monitoring ATP release in astrocytes76, 77, and detecting serotonin in cell culture using glass nanopipettes77.

Clinical Applications

EAB sensors enable unprecedented opportunities to monitor molecules in the challenging in-vivo environment, and could produce innovations across clinical practice. We envision, for example, the adaptation of the EAB sensing platform into a wearable device which, analogous to the continuous glucose monitor, can measure drugs and biomarkers indicative of health and disease in real-time. (To this end, the application of EAB sensors in the interstitial region of the skin are a development worth watching51.) For patients suspected of having sepsis, for example, monitoring infection biomarkers, such a C-reactive protein, could provide a life-saving indicator of disease prognosis and severity78. Similarly, given that specific biomarkers, such as troponin, accompany heart attack onset79, a convenient, wearable device could aid in early detection of heart attacks for individuals with high cardiac risk factors. Given that EAB sensors are the only technology capable of measuring picomolar concentrations of specific (non-enzyme) proteins in real time in complex sample matrices, the platform appears uniquely well-suited for such monitoring25–27.

In addition to disease detection and monitoring, EAB sensors could also enable high-precision, highly-personalized drug dosing. Today, the bulk of pharmaceutical dosing is performed based on assumptions of how an average person absorbs and responds to a drug. The therapeutic windows of some drugs, however, are too narrow (relative to patient-to-patient or, even intra-patient variability) for this approach to work. For these, dosage is presently guided by (slow inconvenient, infrequent) blood draws and laboratory-based analysis, or by waiting for harmful side effects to appear. This can lead to dire consequences arising from either underdosing or overdosing. By providing a convenient, real-time window into plasma drug levels, applying EAB sensors to the problem of performing therapeutic drug monitoring could thus greatly improve the safety and efficacy of pharmacological treatments.

Threats

Here, we consider competing technologies that might achieve the goal of continuous, long duration molecular monitoring in the living body.

Direct Electrochemical Sensing

Certain molecular targets of interest are electroactive at potentials that can be safely applied within the body. These include the neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, histamine, serotonin, and adenosine55, 80. Other physiologically relevant, electroactive compounds include oxygen, nitric oxide, hydrogen peroxide and ascorbate81, 82. The oxidation or reduction of these species using an in vivo electrode allows for their direct detection, typically via chronoamperometry, differential pulse voltammetry, or fast scan cyclic voltammetry55, 80, 83. In the neurosciences, for example, direct electrochemistry has seen extensive application for the in vivo measurement of dopamine and serotonin84, 85,86. In vivo measurements of these compounds, however, often suffer from poor sensitivity and specificity. For example, overlapping redox potentials cause substances, such as ascorbic acid, to interfere with neurotransmitter detection80. This overlap also renders it difficult to differentiate between related molecules, such as the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin87. Likewise, many electrochemical techniques are not sensitive enough to detect biologically relevant levels of molecules when deployed in vivo87. These challenges, combined with the limited number of molecules of interest that are appropriately electroactive, limits the scope of in vivo measurements using direct electrochemistry88.

Enzymatic Sensors

As we noted above, enzymatic sensors, which instead rely on the enzymatic reactivity of their targets, are among the few commercially available molecular monitoring technologies capable of performing directly in the body. In addition to the glucose oxidase-based continuous glucose monitor89, similar in vivo enzymatic sensors have also been described for lactate90, acetylcholine91, 92, and glutamate81, 82, 93. The further development of such sensors, however, has been limited by (1) a lack of suitable enzymes, (2) instability or toxicity of the mediator species used to enable electron transfer to the electrode88, (3) poor enzyme stability94, and (4) interference arising from endogenous electroactive active species95.

Optical Methods

A number of optical approaches have been reported for monitoring specific molecules in the body. As noted above, the pulse oximeter, which measures blood oxygen by directing infrared light through the skin, is a widespread optical sensor used in routine medical monitoring. In addition to the commercial pulse oximeter, other optical technologies relying on fluorescence96–98 and photoacoustics99 can track biomarkers in the living body. Injectable optical sensors, for example, have been reported that use target binding to an optical reporter to change either fluorescent or photoacoustic signal. These sensors require injection of photo-reactive, target-binding chemicals into the dermis, and have demonstrated in vivo detection of sodium98, lithium99, and histamine100, 101. And in contrast to electrochemical approaches, which often provide measurements at a single targeted location, optical methods can sometimes be used to provide spatially resolved measurements. Like enzymatic sensors, however, these approaches are not generalizable due to their reliance on the specific chemical reactivities of theirs target. Finally, optical probes inserted into the body often diffuse away from the site of injection, which can complicate quantification and impact measurement duration101.

Field Effect Transistors

Researchers have recently adapted field effect transistor based “aptasensors” from in vitro60, 102 to in vivo measurements103. Instead of using a redox reporter modified aptamer probe on an electrode, these sensors utilize an aptamer (with no redox reporter attached) deposited on the gate region of a transistor. Target binding shifts the drain-source current, presumably due to changes in electric field associated with the distance between the negatively-charged DNA and the gate. Such sensors retain the generalizability of EAB sensors, and are reported to achieve significantly improved limits of detection. Uncertainties remain, however, regarding the applicability of this newly reported approach in vivo. For example, the only reported in vivo measurements presented to date (serotonin in the mouse brain before and after electrical stimulation) presented only ~10-20 data points collected over just a few minutes. Due to the comparatively short duration of these measurements, we cannot yet judge this platform’s applicability to long duration measurements in the living body. A second concern is that the response curves (concentration versus signal change) of sensors in this class, which often span many orders of magnitude of target concentration60, 102, 103, are quite shallow103. Large changes in target concentration are thus required to produce statistically significant changes in sensor output, greatly reducing measurement precision. For these reasons it appears that this approach has some significant ground to cover before it reaches the level of validation already achieved by in vivo EAB sensors.

Conclusions

In vivo EAB sensors are still in their infancy, having yet to transition to either market-ready products (like the continuous glucose meter) or to widely applied research tools (like the direct electrochemical detection of neurotransmitters). And yet, EAB sensors are already a “class in their own” platform in terms of their ability to perform quantitative in vivo molecular measurements. This generalizable platform hosts a wealth of benefits, such as excellent time resolution, miniaturizability, and applicability to a range of device formats. And while the platform faces challenges along the path from aptamer discovery to EAB sensor development, this has not notably impeded the introduction of new, useful EAB sensors each year. For this field to mature and yield reliable analytical tools, however, we need to actively seek a greater understanding of interfacial stability, and pursue applications to reduce sensor drift. This is no surprise, however. The existing glucose meters rely on the use of selective membranes to mediate the effects of fouling in blood or the dermal space. Thus, we believe that, with the application of both electrochemical and interfacial methods to alleviate sensor drift, EAB sensors could support long-duration, time resolved measurements of a multitude of scientifically and clinically important molecules in situ in the living body.

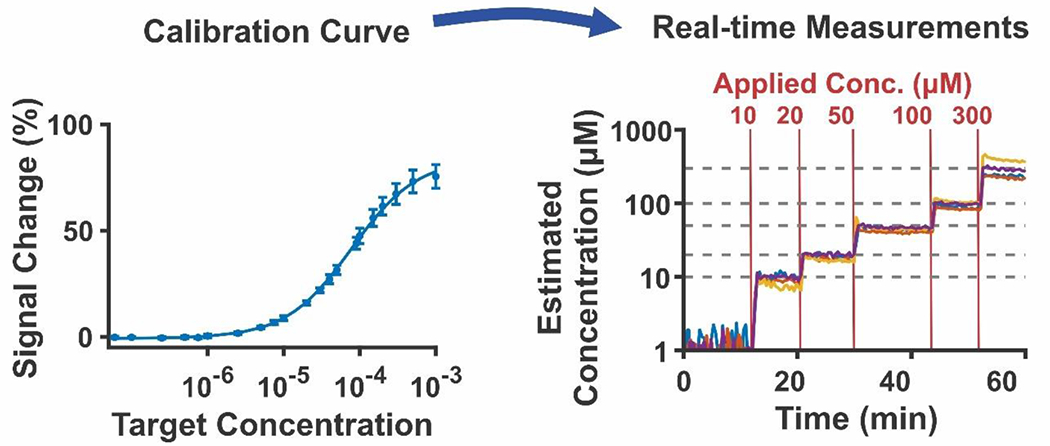

Figure 2:

EAB sensors are quantitative. (A) To achieve this, we first generate a calibration curve, in which we measure the electrochemical signal change in response to the addition of graduated concentrations of target. The resulting data is fit to a Hill-Langmuir isotherm, yielding parameters that enable (B) quantification of data inputted into the Hill-Langmuir equation. (Reproduced with permission from Downs, A.; Gerson, J.; Leung, K.; Honeywell, K.; Kippin, T.; Plaxco, K. Improved calibration of electrochemical aptamer-based sensors. Scientific Reports 202235. )

Table 1:

Summary of respective strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats for the EAB sensing platform in translation to in vivo measurements.

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

|

High-frequency, real-time measurements Generalizable to many targets Selective enough to deploy directly in-vivo Miniaturizable |

The efficiency of adapting new aptamer sequences into EAB sensors Aptamer performance Measurement duration |

Applications in biomedical research Clinical applications |

Other in-vivo molecular sensing strategies: - Enzymatic - Direct Electrochemistry - Optical methods - Field effect transistors |

Acknowledgements

Sandia National Laboratories is a multimission laboratory managed and operated by National Technology and Engineering Solutions of Sandia LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Honeywell International Inc. for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under contract DE-NA0003525. Conclusions and opinions presented here are those of the authors and are not the official policy of the US Government. We acknowledge funding from the Laboratory Directed Research & Development program (project 225930, SAND2022-12335 J to A.M.D.) and the National Institutes of Health (projects R01EB022015, R01DA051100, R01AI145206, to K.W.P).

References

- 1.Xiao Y; Lubin AA; Heeger AJ; Plaxco KW, Label-free electronic detection of thrombin in blood serum by using an aptamer-based sensor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2005, 44 (34), 5456–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendelson Y, Pulse oximetry: Theory and applications for noninvasive monitoring. Clin. Chem 1992, 38 (9), 1601–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker B; Cooper MA, A survey of the 2006–2009 quartz crystal microbalance biosensor literature. J. Mol. Recognit 2011, 24 (5), 754–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziegler C, Cantilever-based biosensors. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2004, 379 (7), 946–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson BN; Mutharasan R, Biosensing using dynamic-mode cantilever sensors: A review. Biosens. Bioelectron 2012, 32 (1), 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniels JS; Pourmand N, Label-free impedance biosensors: Opportunities and challenges. Electroanalysis 2007, 19 (12), 1239–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahadır EB; Sezgintürk MK, A review on impedimetric biosensors. Artif. Cells, Nanomed., Biotechnol 2016, 44 (1), 248–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattiasson B; Hedström M, Capacitive biosensors for ultra-sensitive assays. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem 2016, 79, 233–238. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dauphin-Ducharme P; Plaxco KW, Maximizing the signal gain of electrochemical-DNA sensors. Anal. Chem 2016, 88 (23), 11654–11662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arroyo-Currás N; Dauphin-Ducharme P; Ortega G; Ploense KL; Kippin TE; Plaxco KW, Subsecond-resolved molecular measurements in the living body using chronoamperometrically interrogated aptamer-based sensors. ACS Sens 2018, 3 (2), 360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pellitero MA; Curtis SD; Arroyo-Currás N, Interrogation of electrochemical aptamer-based sensors via peak-to-peak separation in cyclic voltammetry improves the temporal stability and batch-to-batch variability in biological fluids. ACS Sens. 2021, 6 (3), 1199–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downs AM; Gerson J; Ploense KL; Plaxco KW; Dauphin-Ducharme P, Subsecond-resolved molecular measurements using electrochemical phase interrogation of aptamer-based sensors. Anal. Chem 2020, 92 (20), 14063–14068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellington AD; Szostak JW, In vitro selection of rna molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 1990, 346 (6287), 818–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tuerk C; Gold L, Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: Rna ligands to bacteriophage t4 DNA polymerase. Science 1990, 249 (4968), 505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao Y; Uzawa T; White RJ; Demartini D; Plaxco KW, On the signaling of electrochemical aptamer-based sensors: Collision- and folding-based mechanisms. Electroanalysis 2009, 21 (11), 1267–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoukroun-Barnes LR; Wagan S; White RJ, Enhancing the analytical performance of electrochemical rna aptamer-based sensors for sensitive detection of aminoglycoside antibiotics. Anal. Chem 2014, 86 (2), 1131–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dauphin-Ducharme P; Yang K; Arroyo-Currás N; Ploense KL; Zhang Y; Gerson J; Kurnik M; Kippin TE; Stojanovic MN; Plaxco KW, Electrochemical aptamer-based sensors for improved therapeutic drug monitoring and high-precision, feedback-controlled drug delivery. ACS Sens. 2019, 4 (10), 2832–2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang D; Ricci F; White RJ; Plaxco KW, Survey of redox-active moieties for application in multiplexed electrochemical biosensors. Anal. Chem 2016, 88 (21), 10452–10458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koutsoumpeli E; Murray J; Langford D; Bon RS; Johnson S, Probing molecular interactions with methylene blue derivatized self-assembled monolayers. Sensing and Bio-Sensing Research 2015, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S; Ferrer-Ruiz A; Dai J; Ramos-Soriano J; Du X; Zhu M; Zhang W; Wang Y; Herranz MÁ; Jing L; Zhang Z; Li H; Xia F; Martín N, A ph-independent electrochemical aptamer-based biosensor supports quantitative, real-time measurement in vivo. Chem. Sci 2022, 13 (30), 8813–8820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plaxco KW; Soh HT, Switch-based biosensors: A new approach towards real-time, in vivo molecular detection. Trends Biotechnol. 2011, 29 (1), 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoukroun-Barnes LR; Macazo FC; Gutierrez B; Lottermoser J; Liu J; White RJ, Reagentless, structure-switching, electrochemical aptamer-based sensors. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif) 2016, 9 (1), 163–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Idili A; Arroyo-Currás N; Ploense KL; Csordas AT; Kuwahara M; Kippin TE; Plaxco KW, Seconds-resolved pharmacokinetic measurements of the chemotherapeutic irinotecan in situ in the living body. Chem. Sci 2019, 10 (35), 8164–8170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swensen JS; Xiao Y; Ferguson BS; Lubin AA; Lai RY; Heeger AJ; Plaxco KW; Soh HT, Continuous, real-time monitoring of cocaine in undiluted blood serum via a microfluidic, electrochemical aptamer-based sensor. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131 (12), 4262–4266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Idili A; Parolo C; Alvarez-Diduk R; Merkoçi A, Rapid and efficient detection of the sars-cov-2 spike protein using an electrochemical aptamer-based sensor. ACS Sens. 2021, 6 (8), 3093–3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai RY; Plaxco KW; Heeger AJ, Aptamer-based electrochemical detection of picomolar platelet-derived growth factor directly in blood serum. Anal. Chem 2007, 79 (1), 229–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y; Zhou Q; Revzin A, An aptasensor for electrochemical detection of tumor necrosis factor in human blood. Analyst 2013, 138 (15), 4321–4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y; Tuleouva N; Ramanculov E; Revzin A, Aptamer-based electrochemical biosensor for interferon gamma detection. Anal. Chem 2010, 82 (19), 8131–8136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Idili A; Gerson J; Kippin T; Plaxco KW, Seconds-resolved, in situ measurements of plasma phenylalanine disposition kinetics in living rats. Anal. Chem 2021, 93 (8), 4023–4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Idili A; Parolo C; Ortega G; Plaxco KW, Calibration-free measurement of phenylalanine levels in the blood using an electrochemical aptamer-based sensor suitable for point-of-care applications. ACS Sens. 2019, 4 (12), 3227–3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fetter L; Richards J; Daniel J; Roon L; Rowland TJ; Bonham AJ, Electrochemical aptamer scaffold biosensors for detection of botulism and ricin toxins. Chem. Commun 2015, 51 (82), 15137–15140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daniel J; Fetter L; Jett S; Rowland TJ; Bonham AJ, Electrochemical aptamer scaffold biosensors for detection of botulism and ricin proteins. In Microbial toxins: Methods and protocols, Holst O, Ed. Springer; New York: New York, NY, 2017; pp 9–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H; Somerson J; Xia F; Plaxco KW, Electrochemical DNA-based sensors for molecular quality control: Continuous, real-time melamine detection in flowing whole milk. Anal. Chem 2018, 90 (18), 10641–10645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Somerson J; Plaxco KW, Electrochemical aptamer-based sensors for rapid point-of-use monitoring of the mycotoxin ochratoxin a directly in a food stream. Molecules 2018, 23 (4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Downs AM; Gerson J; Leung KK; Honeywell KM; Kippin T; Plaxco KW, Improved calibration of electrochemical aptamer-based sensors. Sci. Rep 2022, 12 (1), 5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker BR; Lai RY; Wood MS; Doctor EH; Heeger AJ; Plaxco KW, An electronic, aptamer-based small-molecule sensor for the rapid, label-free detection of cocaine in adulterated samples and biological fluids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128 (10), 3138–3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White RJ; Plaxco KW, Exploiting binding-induced changes in probe flexibility for the optimization of electrochemical biosensors. Anal. Chem 2010, 82 (1), 73–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiao Y; Lai RY; Plaxco KW, Preparation of electrode-immobilized, redox-modified oligonucleotides for electrochemical DNA and aptamer-based sensing. Nat. Protoc 2007, 2 (11), 2875–2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao Y; Lubin AA; Heeger AJ; Plaxco KW, Label-free electronic detection of thrombin in blood serum by using an aptamer-based sensor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2005, 44 (34), 5456–5459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parolo C; Idili A; Ortega G; Csordas A; Hsu A; Arroyo-Currás N; Yang Q; Ferguson BS; Wang J; Plaxco KW, Real-time monitoring of a protein biomarker. ACS Sens. 2020, 5 (7), 1877–1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santos-Cancel M; Simpson LW; Leach JB; White RJ, Direct, real-time detection of adenosine triphosphate release from astrocytes in three-dimensional culture using an integrated electrochemical aptamer-based sensor. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2019, 10 (4), 2070–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santos-Cancel M; Lazenby RA; White RJ, Rapid two-millisecond interrogation of electrochemical, aptamer-based sensor response using intermittent pulse amperometry. ACS Sens. 2018, 3 (6), 1203–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu J; Wagan S; Dávila Morris M; Taylor J; White RJ, Achieving reproducible performance of electrochemical, folding aptamer-based sensors on microelectrodes: Challenges and prospects. Anal. Chem 2014, 86 (22), 11417–11424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deng M; Li M; Li F; Mao X; Li Q; Shen J; Fan C; Zuo X, Programming accessibility of DNA monolayers for degradation-free whole-blood biosensors. ACS Mater. Lett 2019, 1 (6), 671–676. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leung KK; Downs AM; Ortega G; Kurnik M; Plaxco KW, Elucidating the mechanisms underlying the signal drift of electrochemical aptamer-based sensors in whole blood. ACS Sens. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferguson BS; Hoggarth DA; Maliniak D; Ploense K; White RJ; Woodward N; Hsieh K; Bonham AJ; Eisenstein M; Kippin TE; Plaxco KW; Soh HT, Real-time, aptamer-based tracking of circulating therapeutic agents in living animals. Sci. Transl. Med 2013, 5 (213), 213ra165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li H; Dauphin-Ducharme P; Arroyo-Currás N; Tran CH; Vieira PA; Li S; Shin C; Somerson J; Kippin TE; Plaxco KW, A biomimetic phosphatidylcholine-terminated monolayer greatly improves the in vivo performance of electrochemical aptamer-based sensors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 2017, 56 (26), 7492–7495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arroyo-Currás N; Somerson J; Vieira PA; Ploense KL; Kippin TE; Plaxco KW, Real-time measurement of small molecules directly in awake, ambulatory animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2017, 114 (4), 645–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arroyo-Currás N; Ortega G; Copp DA; Ploense KL; Plaxco ZA; Kippin TE; Hespanha JP; Plaxco KW, High-precision control of plasma drug levels using feedback-controlled dosing. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci 2018, 1 (2), 110–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vieira PA; Shin CB; Arroyo-Currás N; Ortega G; Li W; Keller AA; Plaxco KW; Kippin TE, Ultra-high-precision, in-vivo pharmacokinetic measurements highlight the need for and a route toward more highly personalized medicine. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2019, 6 (69). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu Y; Tehrani F; Teymourian H; Mack J; Shaver A; Reynoso M; Kavner J; Huang N; Furmidge A; Duvvuri A; Nie Y; Laffel LM; Doyle FJ; Patti M-E; Dassau E; Wang J; Arroyo-Currás N, Microneedle aptamer-based sensors for continuous, real-time therapeutic drug monitoring. Anal. Chem 2022, 94 (23), 8335–8345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor IM; Du Z; Bigelow ET; Eles JR; Horner AR; Catt KA; Weber SG; Jamieson BG; Cui XT, Aptamer-functionalized neural recording electrodes for the direct measurement of cocaine in vivo. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5 (13), 2445–2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li H; Li S; Dai J; Li C; Zhu M; Li H; Lou X; Xia F; Plaxco Kevin W., High frequency, calibration-free molecular measurements in situ in the living body. Chem. Sci 2019, 10 (47), 10843–10848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li H; Dauphin-Ducharme P; Arroyo-Currás N; Tran CH; Vieira PA; Li S; Shin C; Somerson J; Kippin TE; Plaxco KW, A biomimetic phosphatidylcholine-terminated monolayer greatly improves the in vivo performance of electrochemical aptamer-based sensors. 2017, 56 (26), 7492–7495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bucher ES; Wightman RM, Electrochemical analysis of neurotransmitters. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem 2015, 8, 239–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sinex JE, Pulse oximetry: Principles and limitations. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 1999, 17 (1), 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee H; Hong YJ; Baik S; Hyeon T; Kim D-H, Enzyme-based glucose sensor: From invasive to wearable device. Adv. Healthcare Mater 2018, 7 (8), 1701150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Downs AM; Gerson J; Hossain MN; Ploense K; Pham M; Kraatz H-B; Kippin T; Plaxco KW, Nanoporous gold for the miniaturization of in vivo electrochemical aptamer-based sensors. ACS Sens. 2021, 6 (6), 2299–2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin PH; Chen RH; Lee CH; Chang Y; Chen CS; Chen WY, Studies of the binding mechanism between aptamers and thrombin by circular dichroism, surface plasmon resonance and isothermal titration calorimetry. Colloids and surfaces. B, Biointerfaces 2011, 88 (2), 552–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nakatsuka N; Yang K-A; Abendroth John M; Cheung Kevin M; Xu X; Yang H; Zhao C; Zhu B; Rim You S; Yang Y; Weiss Paul S; Stojanović Milan N; Andrews Anne M, Aptamer–field-effect transistors overcome debye length limitations for small-molecule sensing. Science 2018, 362 (6412), 319–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.White RJ; Rowe AA; Plaxco KW, Re-engineering aptamers to support reagentless, self-reporting electrochemical sensors. Analyst 2010, 135 (3), 589–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xiao Y; Piorek BD; Plaxco KW; Heeger AJ, A reagentless signal-on architecture for electronic, aptamer-based sensors via target-induced strand displacement. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127 (51), 17990–17991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu Y; Ranallo S; Del Grosso E; Chamoro-Garcia A; Ennis HL; Milosavić N; Yang K; Kippin T; Ricci F; Stojanovic M; Plaxco KW, Using spectroscopy to guide the adaptation of aptamers into electrochemical aptamer-based sensors. Bioconjugate Chem. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stoltenburg R; Reinemann C; Strehlitz B, Selex—a (r)evolutionary method to generate high-affinity nucleic acid ligands. Biomol. Eng 2007, 24 (4), 381–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Skouridou V; Schubert T; Bashammakh AS; El-Shahawi MS; Alyoubi AO; O’Sullivan CK, Aptatope mapping of the binding site of a progesterone aptamer on the steroid ring structure. Anal. Biochem 2017, 531, 8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shaver A; Kundu N; Young BE; Vieira PA; Sczepanski JT; Arroyo-Currás N, Nuclease hydrolysis does not drive the rapid signaling decay of DNA aptamer-based electrochemical sensors in biological fluids. Langmuir 2021, 37 (17), 5213–5221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang K-A; Pei R; Stojanovic MN, In vitro selection and amplification protocols for isolation of aptameric sensors for small molecules. Methods 2016, 106, 58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shaver A; Arroyo-Currás N, The challenge of long-term stability for nucleic acid-based electrochemical sensors. Curr. Opin. Electrochem 2022, 32, 100902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.White RJ; Phares N; Lubin AA; Xiao Y; Plaxco KW, Optimization of electrochemical aptamer-based sensors via optimization of probe packing density and surface chemistry. Langmuir 2008, 24 (18), 10513–10518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lai RY; Seferos DS; Heeger AJ; Bazan GC; Plaxco KW, Comparison of the signaling and stability of electrochemical DNA sensors fabricated from 6- or 11-carbon self-assembled monolayers. Langmuir 2006, 22 (25), 10796–10800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brothers MC; Moore D; Lawrence M; Harris J; Joseph RM; Ratcliff E; Ruiz ON; Glavin N; Kim SS, Impact of self-assembled monolayer design and electrochemical factors on impedance-based biosensing. Sensors (Basel) 2020, 20 (8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shaver A; Curtis SD; Arroyo-Currás N, Alkanethiol monolayer end groups affect the long-term operational stability and signaling of electrochemical, aptamer-based sensors in biological fluids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12 (9), 11214–11223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li S; Wang Y; Zhang Z; Wang Y; Li H; Xia F, Exploring end-group effect of alkanethiol self-assembled monolayers on electrochemical aptamer-based sensors in biological fluids. Anal. Chem 2021, 93 (14), 5849–5855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Santos-Cancel M; White RJ, Collagen membranes with ribonuclease inhibitors for long-term stability of electrochemical aptamer-based sensors employing rna. Anal. Chem 2017, 89 (10), 5598–5604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wackerbarth H; Grubb M; Zhang J; Hansen AG; Ulstrup J, Long-range order of organized oligonucleotide monolayers on au(111) electrodes. Langmuir 2004, 20 (5), 1647–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Santos-Cancel M; Simpson LW; Leach JB; White RJ, Direct, real-time detection of adenosine triphosphate release from astrocytes in three-dimensional culture using an integrated electrochemical aptamer-based sensor. ACS chemical neuroscience 2019, 10 (4), 2070–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakatsuka N; Heard KJ; Faillétaz A; Momotenko D; Vörös J; Gage FH; Vadodaria KC, Sensing serotonin secreted from human serotonergic neurons using aptamer-modified nanopipettes. Molecular psychiatry 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sankar V; Webster NR, Clinical application of sepsis biomarkers. Journal of Anesthesia 2013, 27 (2), 269–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Babuin L; Jaffe AS, Troponin: The biomarker of choice for the detection of cardiac injury. Can. Med. Assoc. J 2005, 173 (10), 1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Robinson DL; Hermans A; Seipel AT; Wightman RM, Monitoring rapid chemical communication in the brain. Chem. Rev 2008, 108 (7), 2554–2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ferreira NR; Ledo A; Laranjinha J; Gerhardt GA; Barbosa RM, Simultaneous measurements of ascorbate and glutamate in vivo in the rat brain using carbon fiber nanocomposite sensors and microbiosensor arrays. Bioelectrochemistry 2018, 121, 142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weltin A; Kieninger J; Enderle B; Gellner A-K; Fritsch B; Urban GA, Polymer-based, flexible glutamate and lactate microsensors for in vivo applications. Biosens. Bioelectron 2014, 61, 192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roberts JG; Sombers LA, Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry: Chemical sensing in the brain and beyond. Anal. Chem 2018, 90 (1), 490–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rodeberg NT; Sandberg SG; Johnson JA; Phillips PEM; Wightman RM, Hitchhiker’s guide to voltammetry: Acute and chronic electrodes for in vivo fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2017, 8 (2), 221–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Clark JJ; Sandberg SG; Wanat MJ; Gan JO; Horne EA; Hart AS; Akers CA; Parker JG; Willuhn I; Martinez V; Evans SB; Stella N; Phillips PEM, Chronic microsensors for longitudinal, subsecond dopamine detection in behaving animals. Nat. Methods 2010, 7 (2), 126–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Swamy BEK; Venton BJ, Carbon nanotube-modified microelectrodes for simultaneous detection of dopamine and serotoninin vivo. Analyst 2007, 132 (9), 876–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.O’Neill RD, Microvoltammetric techniques and sensors for monitoring neurochemical dynamics in vivo. A review. Analyst 1994, 119 (5), 767–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tan C; Robbins EM; Wu B; Cui XT, Recent advances in in vivo neurochemical monitoring. Micromachines (Basel) 2021, 12 (2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Teymourian H; Barfidokht A; Wang J, Electrochemical glucose sensors in diabetes management: An updated review (2010–2020). Chem. Soc. Rev 2020, 49 (21), 7671–7709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wolf A; Renehan K; Ho KKY; Carr BD; Chen CV; Cornell MS; Ye M; Rojas-Peña A; Chen H, Evaluation of continuous lactate monitoring systems within a heparinized in vivo porcine model intravenously and subcutaneously. Biosensors 2018, 8 (4), 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Burmeister JJ; Pomerleau F; Huettl P; Gash CR; Werner CE; Bruno JP; Gerhardt GA, Ceramic-based multisite microelectrode arrays for simultaneous measures of choline and acetylcholine in cns. Biosens. Bioelectron 2008, 23 (9), 1382–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bruno JP; Gash C; Martin B; Zmarowski A; Pomerleau F; Burmeister J; Huettl P; Gerhardt GA, Second-by-second measurement of acetylcholine release in prefrontal cortex. European Journal of Neuroscience 2006, 24 (10), 2749–2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Naylor E; Aillon DV; Gabbert S; Harmon H; Johnson DA; Wilson GS; Petillo PA, Simultaneous real-time measurement of eeg/emg and l-glutamate in mice: A biosensor study of neuronal activity during sleep. J. Electroanal. Chem 2011, 656 (1-2), 106–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rocchitta G; Spanu A; Babudieri S; Latte G; Madeddu G; Galleri G; Nuvoli S; Bagella P; Demartis M; Fiore V; Manetti R; Serra P, Analytical problems in exposing amperometric enzyme biosensors to biological fluids. Sensors (Basel) 2016, 16, 780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Soto RJ; Hall JR; Brown MD; Taylor JB; Schoenfisch MH, In vivo chemical sensors: Role of biocompatibility on performance and utility. Anal. Chem 2017, 89 (1), 276–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhao M; Li B; Zhang H; Zhang F, Activatable fluorescence sensors for in vivo bio-detection in the second near-infrared window. Chem. Sci 2021, 12 (10), 3448–3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Iverson NM; Barone PW; Shandell M; Trudel LJ; Sen S; Sen F; Ivanov V; Atolia E; Farias E; McNicholas TP; Reuel N; Parry NMA; Wogan GN; Strano MS, In vivo biosensing via tissue-localizable near-infrared-fluorescent single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nat. Nanotechnol 2013, 8 (11), 873–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dubach JM; Lim E; Zhang N; Francis KP; Clark H, In vivo sodium concentration continuously monitored with fluorescent sensors. Integr. Biol 2011, 3 (2), 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cash KJ; Li C; Xia J; Wang LV; Clark HA, Optical drug monitoring: Photoacoustic imaging of nanosensors to monitor therapeutic lithium in vivo. ACS Nano 2015, 9 (2), 1692–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cash KJ; Clark HA, In vivo histamine optical nanosensors. Sensors (Basel) 2012, 12 (9), 11922–11932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cash KJ; Clark HA, Phosphorescent nanosensors for in vivo tracking of histamine levels. Anal. Chem 2013, 85 (13), 6312–6318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cheung KM; Yang K-A; Nakatsuka N; Zhao C; Ye M; Jung ME; Yang H; Weiss PS; Stojanović MN; Andrews AM, Phenylalanine monitoring via aptamer-field-effect transistor sensors. ACS Sens. 2019, 4 (12), 3308–3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhao C; Cheung Kevin M; Huang IW; Yang H; Nakatsuka N; Liu W; Cao Y; Man T; Weiss Paul S; Monbouquette Harold G; Andrews Anne M, Implantable aptamer–field-effect transistor neuroprobes for in vivo neurotransmitter monitoring. Sci. Adv 7 (48), eabj7422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]